ABSTRACT

Although women now occupy a record number of governorships and the number of women running for governor has increased significantly in the last four years, women still run for governor at lower rates than men. This study examines why there have been so few women gubernatorial candidates in primary elections using a dataset that includes every primary election or convention used to select major party gubernatorial nominees from 1978 through 2022. We examine four distinct areas to learn why so few women run: the potential candidate pool; candidates, parties, and voters as strategic actors; gubernatorial office structure; and major political, social, and cultural events and their impact on candidate pools. With some important differences between the Democratic and Republican parties, we find that each of these areas has a significant impact on whether women run for governor. Notably, we find that the pipeline is significant for Republican women during the period of study but not for Democratic women. Office structure, incumbent governors, and events such as those surrounding the 2016 election, also impact whether women run for governor. The results indicate that states can adopt changes to the structure of the governor’s office, and parties can adopt rules and facilitate norms that are favorable to women.

Introduction

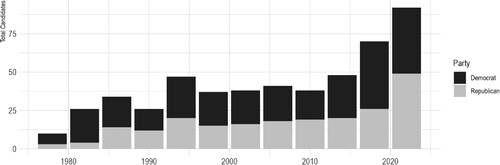

One of the stories of the 2022 election was that after the votes were counted, a record 12 women would be serving as governor in 2023.Footnote1 Less discussed was the record number of women gubernatorial candidates.Footnote2 In the 36 states that held elections in 2022, 64 women candidates appeared on a major party primary ballot. In the four-year cycle from 2019 to 2022, there was a total of 93 women candidates in gubernatorial elections.Footnote3

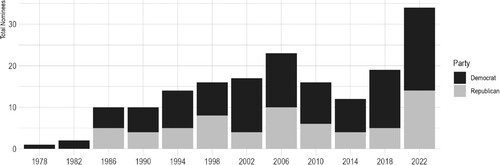

This larger candidate pool led to a record number of women major party gubernatorial nominees. There were 25 nominees in 2022 and 34 in the four-year cycle from 2019 to 2022. In five states, both major party candidates were women in 2022. show these changes.

Figure 1. Women gubernatorial candidates on the ballot by Party: 1978–2022, four-year election groups.

Figure 2. Women gubernatorial nominees by Party, 1978–2022, four-year election groups.

Figure 3. Women governors serving each year, 1975–2023.

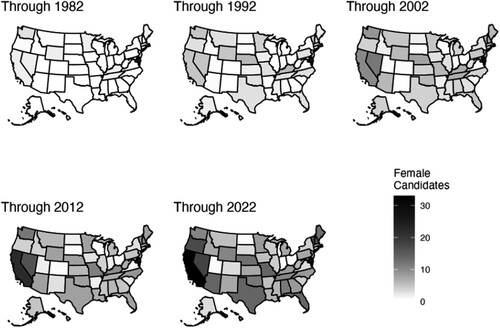

Figure 4. Number of women candidates per state over time, 1978–2022.

In this paper, we seek to explain why there have been so few women gubernatorial candidates in primary elections. We argue that a state’s institutional, structural, and political climate influence when women run for governor and ask if there are differences between political parties.

Factors that influence the number of women gubernatorial candidates

Most of the extant literature on women running for governor has focused on general elections and while, there is more we need to know about this crucial step in elections Further, there is a great deal of focus on when and where women win, but not as much on why they run. There is a need to know more about a critical stage in the process: women’s decision to run in primaries. In this paper we focus on variables that may impact women's decision to run in gubernatorial primary elections. We examine four distinct areas to learn why so few women run: the potential candidate pool; candidates, parties, and voters as strategic actors; gubernatorial office structure; and major political, social, and cultural events and their impact on candidate pools.

The pool of potential gubernatorial candidates

The literature analyzing the source of gubernatorial candidates is thin. As Thomsen and King (Citation2020) note regarding women candidates in gubernatorial elections, “ … there are no studies that place the decision to run for office in the context of the gender makeup of the potential candidate pool” (990). The candidate pool likely drives the number of female gubernatorial candidates. To examine this we use existing women office holders as a pool of potential candidates. Elected officials are a major source of candidates for higher office. As the pool of same-party women in the US Congress and state legislatures grows, so should the gubernatorial candidate pool. There is research which looks at the professional background of women in a state and finds that the supply of qualified women impacts whether women run and whether they win statewide office. Oxley and Fox (Citation2004) find that the supply of women (legal profession and elected office) matters. The larger the supply, the greater the likelihood of women running for and being elected to statewide executive office. On a related note, O’Regan and Stambough (Citation2016) find that women prior statewide officeholders garner more vote totals in gubernatorial races. And overall, they find that statewide elective office experience is beneficial for Democratic women gubernatorial candidates, though not Republicans (which they note may be due to the small number of Republican women candidates when they did the research). While we are not looking at who wins, their research is key to the issue of the pipeline. Women with prior statewide experience may be more likely to run for governor than women who have not held statewide office. It is time to revisit the pipeline to see if women with prior state and statewide office holding experience are more likely to run for governor, if the type of experience matters, and whether or not the rates are similar for Republican and Democratic women candidates.

The structure of the office

The structure of the governor’s position may impact who chooses to run and who is encouraged to run. As Piscopo (Citation2019) argues, “Those looking to boost women’s representation must first account for the profoundly uneven playing fields created by political and electoral institutions, party organizations, and social structures” (818). There is research that looks at structural barriers to women running for office, for example term limits and campaign finance laws (Sanbonmatsu and Rogers Citation2020; Sanbonmatsu, Rogers, and Gothreau Citation2020), but there is a lack of research analyzing the myriad of structural variables which, when combined, may impact women’s decision to run for governor. We examine early party endorsement of candidates, combining governor and lieutenant governor in a single ticket, gubernatorial term limits, gubernatorial term length, the governor’s salary, and the presence of public campaign finance. We create an index that includes these six structural elements, a novel contribution to the study of women running for governor.

Some states allow state political parties to endorse candidates before the primary election. Given the continued old-boy network ethos of political parties in many states and the literature on the gendered nature of recruitment by political parties (Crowder-Meyer Citation2013; Niven Citation1998), we expect that early party endorsement is negatively related to having women candidates in a party’s gubernatorial primary. Further, Bardwell (Citation2002) finds that in gubernatorial primaries, “[w]here formal party endorsement is recognized by state law, it is a strong deterrent to challengers who would enter a primary” (657).

On the face of it, women running for and serving as lieutenant governors could gain name recognition and political experience. Further, if the governor leaves office, the lieutenant governor ascends to the governorship. Hennings and Urbatsch (Citation2016) found that Republican women were particularly likely to ascend unelected from lieutenant governor to governor. As of the 2022 elections, this is still the case (9 of 19 women Republican governors rose to the job this way). This is less likely for Democratic women (only 4 of 30 as of 2022 elections). Hennings and Urbatsch (Citation2015) find that only one woman can be on the ticket and the more likely spot for the woman is lieutenant governor.Footnote4 Despite these ascensions, a combined ticket relegates women to being lieutenant governors, defined by Fox and Oxley as a neutral-gendered office, and does not provide them with significant political experience or public support that assists them in a future run for governor. Combined tickets result in an “always the bridesmaid, never the bride” culture where parties can claim gender diversity due to a combined ticket that has a woman in the lieutenant governor spot but do little work to make sure a woman is in the top spot. These women lieutenant governors will rarely have the credibility and resources needed to run for governor. Thus, we expect more women candidates in states where the governor and lieutenant governor elections are separate.

While the research on legislative term limits has not shown clear benefits for increasing women in state legislatures (Caress Citation1999; Carroll and Jenkins Citation2001), we suspect that gubernatorial term limits may positively influence women candidates’ decisions to announce. Running in an open seat for governor is a vastly different experience than challenging an incumbent governor. Strategic women might wait for open-seat races, which will come around with some frequency in states with gubernatorial term limits. Most gubernatorial term limits are for two terms (usually eight years). We expect that states with gubernatorial term limits will see more women candidates for governor.

States with shorter gubernatorial terms make for less attractive offices for those with progressive political ambitions. Rohde (Citation1979) found that members of the U.S. House of Representatives are less likely to run for governor when it is a two-year term. Thus, they may not opt to run for governor and instead choose another office. Two states, New Hampshire and Vermont, currently have two-year terms for governor. Rhode Island had two-year terms through the 1992 election. If men pass up these opportunities for other offices with longer terms, states with shorter terms may attract more women candidates.

We expect that states that pay their governors well will be more likely to attract “qualified” men to run and thus create a more competitive seat, discouraging women candidates. Research has shown that states that pay higher salaries to their governors attract more highly paid professionals to run (Besley Citation2004) and research on state legislators has found that white collar professionals who run for legislative office report less anxiety about losing their income when running for office in states that offer higher salaries (Carnes and Hansen Citation2016, 707). As the percentage of “highly paid professionals” has historically been men, and even in 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics Citation2023), is still largely men, we expect a negative relationship between salary and the presence of women candidates in a primary. Thus, lower salaries make it more likely that women will run for governor.

The literature on campaign fundraising suggests that women gubernatorial candidates are at a disadvantage compared to their male counterparts. Recent research by Sanbonmatsu and Rogers (Citation2020) on women gubernatorial candidates shows the difficulty of raising the funds needed to run for governor, finding that, “In general election contests featuring a woman versus a man, men incumbents are more monetarily competitive on average than women challengers compared with women incumbents and men challengers (4).” Further, Bardwell suggests that the presence of public financing in gubernatorial elections may help challengers by equalizing competition between the challenger and the incumbent (Bardwell Citation2002, 663). Thus, we expect that public financing should increase the pool of candidates, and in particular women candidates who recognize their fundraising disadvantage. We expect that public financing will be positively related to women running in party primaries for governor.

Strategic actors: candidates, voters, and parties

Scholars have also focused on women candidates themselves, looking to see if they are strategic in choosing if, when, and where to run. Bernhard, Shames, and Teele (Citation2021) examine women who have been recruited to run and have participated in a candidate training program and find that women are significantly less likely to run when they are “breadwinners.” Recruitment and training mainly help women who are not a primary breadwinner (380).

Other research has found that women candidates look to see if there is an incumbent or an open seat or an incumbent. Windett (Citation2011); examines gendered political culture, gendered social culture, and general cultural variables and finds a positive and significant relationship between open seats and women running (thus women are strategic). King (Citation2019) finds that the presence of an incumbent woman governor discourages women challengers. Most incumbent governors win reelection and reelection rates for incumbent governors have gone up steadily in recent decades (Eagleton Center on the American Governor Citation2023). But earlier research by Fox and Oxley (Citation2003) found no significant relationship between the presence of women running for office and open seats. One might expect that an incumbent woman governor would send a message to other women candidates that being elected governor is possible. On the other hand, women may be less willing to challenge a woman incumbent of their party in the primary as King (Citation2019) found. We seek to add clarity to these differential findings on the role of incumbency and open seats.

Related to strategy is the question of whether women lack the ambition to run. Research on this question has found that the lack of women candidates for governor, and thus lack of women governors, is not due to a lack of ambition on their part. Windett (Citation2014) finds

that women tend to be self-starters, begin their careers much later in life, and receive little party recruitment. Women, however, are more likely to take electoral risks when moving up the political career ladder, challenging incumbents at higher rates than their male counterparts, and entering races with greater levels of electoral uncertainty. (287)

While lack of ambition is not a problem, lack self-efficacy is. Women lack self-efficacy as candidates for elected executive office. Women are less likely than similarly situated men to see themselves as qualified to run for statewide executive office (Fox and Lawless Citation2011; Lawless and Fox Citation2018), and thus less likely to self-select to run. And when women do run, Fox and Oxley find that women self-select to run for “stereotypically consistent offices.” Women are less likely to be candidates for masculine-defined elected state executive offices (Fox and Oxley Citation2003), and local elected offices (Holman Citation2017), and more likely to hold feminine-defined statewide executive offices (44%) than masculine-defined statewide executive offices (19%) (Rhinehart, Geras, and Hayden, Citation2022, 160).

That said, there may be benefits to be had from running for any office, even if a feminine office. Holman (Citation2017) notes that, “running for offices traditionally considered ‘masculine’ – which are most local offices – disadvantage women, but they may obtain some benefits when running for stereotypically ‘feminine’ offices like the city clerk and school board.” We expand this research by extending the time frame to examine if the type of statewide executive office women have held impacts their presence on gubernatorial primary ballots. Further, we expand the research by looking to see if there are differences among women by party.

Other research has asked whether the lack of women gubernatorial candidates in primaries and general elections is due to voters or political parties or both. The research frames parties and voters as strategic actors that are barriers to women choosing to run for governor (and being elected to office). O’Regan and Stambough (Citation2011) find that a state with no previous gubernatorial candidates is a major limitation to the success of women gubernatorial candidates in the general election. Campaigns that are driven by the notion of “the first” are harmed by it. A primary reason is voters stereotype offices, and they see the governor as a male office. They further find that being the novelty woman gubernatorial candidate also hurts fundraising. Other research that focuses on the hesitance of voters to elect women has found that states that elect the governor and lieutenant governor together will have fewer women governors because voters don’t like tickets with two women (Hennings and Urbatsch Citation2016). We build on and expand this research by looking to see if women candidates choose not to run in states that have never had a women gubernatorial candidate.

Research also finds that parties are strategic. The parties differ in why they nominate and support women to run for governor. State Republican parties tend to support a woman gubernatorial candidate in races where there is no chance of winning, whereas Democrats are more likely to create a pipeline for women to gain experience and be ready to win when they run Stambough and O’Regan (Citation2007). Thus, parties are strategic regarding when and why they support women candidates. We examine whether Democratic and Republican women are similarly impacted by such party dynamics.

Events

Previous research and news reports have documented that major political events can increase the number of women candidates. We focus on three political events here: The Year of the Woman that began in 1992, the nomination of Sarah Palin as the Republican vice presidential candidate in 2008, and the combined impacts of the Democratic nomination of Hilary Clinton for President, the #metoo movement, and the election of Donald Trump in 2016. The impact of the Year of the Woman on the US Congress and on state legislative races has been well documented, an impact which lasted beyond 1992 (Carpini and Fuchs Citation1993; Nelson Citation1992). Less examined is the impact on women running for statewide office, and in particular, governor. We test whether the year of the woman impacts the number of women gubernatorial candidates from 1992 through 1995. We expect it to have a positive impact on both Republican and Democratic women’s decision to run for governor.

In a similar vein, and in light of journalistic coverage on the impact of the nomination of Sarah Palin as Vice President in 2008, we expect that her nomination may have influenced women’s decision to run for governor, in particular Republican women (Spillius Citation2010). The Palin-effect is measured as taking place during 2009 and 2010 only. Finally, news reports speculated that Trump’s election would prompt women to run, largely Democrats (Hernández Citation2017; Kurtzleben Citation2018), but possibly Republican women as well (Hopkins Citation2022).

There is some evidence that the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016 led to a surge in women candidates (Lawless and Fox Citation2018; Thomsen and King Citation2020). Further, the #metoo movement and the candidacy of Hilary Clinton for President in 2016 may also have influenced more women to run. Given this, we expect gubernatorial primary elections held after 2016 are more likely to include women candidates than those held in 2016 and before. We include the same party percentage of the vote in the last gubernatorial election as a measure of the partisan balance in each state. This variable can be used to examine whether women candidates are more likely to run as “sacrificial lambs.” Fox and Oxley (Citation2003) found no evidence for this phenomenon.

Data and variable specification

In this paper, we ask: What explains the likelihood of women running for governor? Why do some states see more women candidates than other states? We have gathered data on all 1,224 primary elections or conventions used to select major party gubernatorial nominees from 1978 through 2022.Footnote5 The analysis includes 1210 total observations divided into two models, one for Democrats and one for Republicans with 605 elections each.Footnote6

The number of state elections for the period ranges from 11 for the nine states with four-year terms holding their elections during presidential election years to 23 for New Hampshire and Vermont, who have a two-year gubernatorial term with elections held in even number years. Thirty-four states have four-year terms and hold gubernatorial elections in midterm years. Most of these states held 12 elections during the period.Footnote7 The remaining five states hold gubernatorial elections on odd years, with two – New Jersey and Virginia – holding elections the year after presidential elections and three – Louisiana, Kentucky, and Mississippi – electing their governor the year after the midterms.

The dependent variable

In the following party-based analysis, the dependent variable is a count of the number of women candidates appearing on the primary ballot or equivalent.Footnote8 We have adjusted the raw count by subtracting one from the total if an incumbent is running for election as we are interested in the impact of a woman incumbent on other women running.

As seen in , there were no women candidates in 71.7% of the gubernatorial primaries conducted between 1978 and 2022. A single woman candidate has been most common in races with a woman candidate. The 2018 election was the first even year gubernatorial election year, where a majority of primary races included at least one woman gubernatorial candidate. While multiple woman candidates have been an occasional feature since the beginning of our data gathering, they have become increasingly common in the last decade. Seven of the 11 races with three or more women candidates occurred after 2016.

Table 1. Adjusted women candidates.

The dependent variable was gathered with the help of past research by Jensen and Beyle (Citation2003) and Windett (Citation2011).Footnote9 We reviewed and cleaned this data and gathered data for recent election years independently using Ballotpedia and other sources.

Independent variables

We look at several variables related to whether the pool of candidates impacts the number of women gubernatorial candidates. The first five center on current women elected officials: the number of same-party women serving in the state legislature, the number of same-party women serving in masculine-defined statewide executive offices, excluding governors (whose presence is examined separately), the number of same-party women serving in non-masculine-defined statewide executive offices, the number of incumbent same-party women U.S. Senators for each state, and the number of incumbent same-party women members of the U.S. House of Representatives. One might expect that the more women serving in state legislatures and Congress, and specifically, the more women of one’s party, the greater the likelihood of women announcing a run. We chose to use counts, instead of percentages for these variables because we are focused on the pipeline of potential gubernatorial candidates. Second, seeing women in politics sends a message to women that they belong in elected office. As Ladam, Harden, and Windett (Citation2018) find that the presence of a woman governor has an impact on the proportion of women serving in the state legislature (at least in the short term), we suspect that this relationship may move in the other direction as well. We expect that having more same-party women in these offices is positively correlated to having women gubernatorial candidates in a party primary.

We count the number of women in elected same-party masculine-defined and other elected statewide executives using the categories established by Fox and Oxley (Citation2003, 838). Statewide executive offices defined by Fox and Oxley as masculine are counted as masculine-defined executive offices here. Offices defined as neutral or as feminine are counted as other executive offices. Examples of state level masculine elected offices include governor, attorney general, treasurer, tax commissioner, and agricultural commissioner. Lieutenant governor and secretary of state are considered neutral offices while secretary of education is an example of a feminine statewide elective office (Fox and Oxley Citation2003, 838). Offices defined as neutral or as feminine are counted as other executive offices. We argue that this division is still relevant today. Fox and Oxley’s (Citation2003) work in this area is still heavily cited and recently scholars like Mirya Holman (Citation2017), Rhinehart, Geras, and Hayden (Citation2022), and Sanbonmatsu and Rogers (Citation2020) have highlighted this division as relevant to understanding women’s underrepresentation in certain elected offices. As noted above, having women serve in these offices conveys to others that women belong and can be successful candidates. These elected officials also create a pool of candidates for gubernatorial elections. Research has argued that increasing women in the pipeline matters, no matter the office (Thomsen and King Citation2020). As we use counts of women legislators, we use a count of same-party women elected officials serving in masculine-defined statewide executive offices and a count of same-party women elected officials serving in non-masculine defined statewide executive offices. We expect that women currently serving in masculine-defined offices as well as in non-masculine-defined offices will be positively related to having women gubernatorial candidates in each party’s primary.

To examine the impact of the structure of the governor’s office on women’s decision to enter a primary, we create an index that includes six structural elements.

Early party endorsement. If a state has early endorsement, it is coded as 0, and it is coded as 1 if it does not.

Combined governor/lieutenant governor ticket. We expect more women candidates in states where the governor and lieutenant governor elections are separate. This variable is coded 0 for states with combined tickets or who have no lieutenant governor and 1 for states holding separate elections.

Gubernatorial term limits. We expect that gubernatorial term limits will positively impact a woman’s decision to run. This variable is coded 0 for states with no term limits and 1 for states with term limits.

Gubernatorial term length. We posit that states with shorter terms will attract more women candidates. This variable is coded 0 for four-year terms and is coded 1 for two-year terms.

Salary. We expect that lower salaries make it more likely that women will run for governor. This variable was coded 0 if a governor’s salary was in the upper half of salaries in a given year and 1 if a governor’s salary was in the lower half of salaries.

Public financing of elections. We expect that public financing will be positively related to women running in party primaries for governor. This variable is coded 0 if there is no public financing for the governor’s race and 1 if there is public financing.

The index was created by adding up the values of these six variables. The score varies from 0 to 6, with higher scores associated with a more favorable office structure for women candidates. We expect there will be a positive relationship between a higher score on the index and the presence of more women running in a primary election.

We also examine the role of incumbency in whether women run for governor. Incumbency is run as a series of three dichotomous variables: same-party male incumbent, same-party woman incumbent, and open seat. Omitted are other party incumbents. We expect a negative relationship between incumbency and women candidates in the primary race for same party incumbents whether the incumbent is a man or a woman. We expect a positive relationship between open seats and women candidates in the primary race.

The novelty effect is whether a state has had a woman governor serve in the past (O’Regan and Stambough Citation2011). Ladam, Harden, and Windett (Citation2018) find positive, symbolic effects of women holding high-profile elected offices in neighboring states, no matter the party, on the presence of women running for state legislative seats in nearby states. We expect a similar relationship to exist between high profile women governors in neighboring states and the presence of women on the primary ballot. As above, we have limited this to same-party officials. We have conceptualized whether a state has had a woman governor in the past to include all women who have served as governor before the current office holder. If a woman is an incumbent, she is omitted. For neighboring states, we have conceptualized this as a count of the same-party woman governors at the time of the election. We hypothesize that the presence of a woman governor in the recent past will positively correlate to having women gubernatorial candidates in both parties’ primaries as it is a symbolic message that women belong in the office as well as a strategic message that women can win. And we hypothesize that the presence of same-party women governors in neighboring states will positively influence women to run in both parties’ primaries as they also serve as an easy to see indication that women belong.

The three political event variables – the impact of the Year of the Woman, the impact of Sarah Palin’s nomination as Vice President in 2008, whether an election has occurred since Donald Trump was elected president are coded 0 for years where they are not present and 1 for years that they are present.

Finally, we examine a series of control variables: the same party percentage of the two-party vote in the last gubernatorial election, population, political culture, and region. State population is sometimes used as a proxy for diversity. Given the demographic profile of the Democratic Party is more diverse than that of the Republican Party, we expect that more diverse states will be positively associated with more Democratic women candidates (Pew Research Center Citation2023). We include regions to account for broader regional political culture. We also include one other measure of political culture that has been used in past studies: Elazar’s (Citation1994) political culture categories.

Results and analysis

displays the results of our model, estimating the impact of our independent variables of interest on the number of candidates running in each major party gubernatorial primary. Because our data includes counts, we use a negative binomial regression for each of the two party models.Footnote10 Beginning with the pipeline variables, we find that all but US senators are significant for Republicans, none of the five variables are significant for Democrats. The number of same-party women state legislators is positive and significant for Republican women, it is positive but not significant for Democratic women. We find that the number of same-party women senators does not impact a woman’s decision to run for governor for either party. Senators rarely move “backwards” to run for governor (Ostermeier Citation2021). The number of same-party women members of the U.S. House of Representatives is positively correlated and significant for Republican women but negatively correlated and not significant for Democratic women.

Table 2. Negative binomial models of adjusted number of women gubernatorial candidates.

Our findings here regarding Republican women House members and Republican women state legislators exerting a positive impact on Republican women running for governor are similar to that of Ladam, Harden, and Windett’s (Citation2018) finding that high profile elected women have a symbolic causal impact on women running for state legislature. We suspect this relationship is largely a pipeline relationship, but there could also be a symbolic mechanism as well, though the lack of any influence of same-party women Senators indicates it is more likely a pipeline relationship.

The number of same-party women in masculine statewide offices is positively correlated with both Republican and Democratic gubernatorial candidates but is only statistically significant for Republican women. The relationship between the number of women same party non-masculine statewide office holders and women gubernatorial candidates is not significant for either party. The relationship is negative for Republican women and positive for Democratic women.

Republican women are impacted by the pipeline in a way that Democratic women do not appear to be. The presence of Republican women House members, Republican women state legislators, and Republican women holding masculine defined offices are all positively and significantly correlated with the presence of Republican women on a gubernatorial primary ballot. These pipeline variables are not significant for Democratic women.

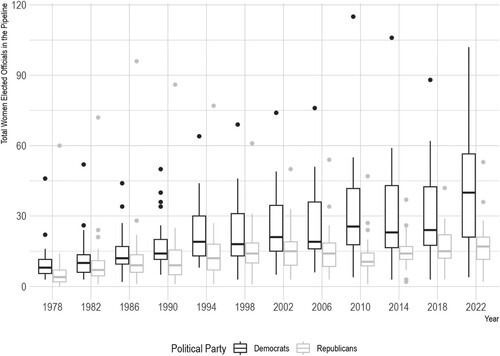

Creating a sufficient pipeline is important to producing more Republican women gubernatorial candidates. This does not necessarily mean that pipeline variables do not matter for Democratic women despite these variables not being statistically significant. A look at the total number of pipeline officeholders in major election years shows that the median number of officeholders has always been much higher for Democrats (see ). It may be that they met the requirements for an adequate pipeline earlier during the period of our research data. In contrast, only recently have most states had an adequate number of Republican office holders to create a regular flow of Republican women gubernatorial candidates. The positive and significant impact of holding elected masculine-defined offices on Republican women running for governor indicate that while increasing the number of women with political experience matters, the type of political experience may be key. Simply encouraging women to run for statewide executive office as a stepping-stone to the governor’s mansion may not be enough. The office of governor is still seen as masculine office, thus previous experience in elected masculine offices may be leading Republican women to feel qualified to run for another masculine office. Further, given Fox and Oxley’s (Citation2003) finding that women are, “not equally likely to run for all types of state executive offices,” (846) and our finding that women holding elected non-masculine defined offices does not impact the number of women running for governor, continued efforts to recruit women to run for specific executive offices is needed.

Figure 5. Total women elected officials in the pipeline by Party, 1978–2022.

In addition, previous research has indicated that being the first woman candidate is a detriment to a candidacy (O’Regan and Stambough Citation2011). Thus, we expected that if a state previously had a woman governor, that this would be positively associated with women running in future elections, especially if this previous governor was from the same party. This is in line with Ladam, Harden, and Windett’s (Citation2018) research on the symbolic causal impact that high profile women play on the decision of women to run for state legislature. However, the presence of a prior same-party woman governor does not influence women from either party to run for governor. The variable is negative and not significant. It is possible that, as Ladam, Harden, and Windett (Citation2018) find, women serve as role models in the short term for potential women candidates, but not in the long term. That said, they may be serving as role models for voters and helping remove the mental barriers that voters have toward electing women as the top executive. In addition, same-party women governors in neighboring states are not significant for either party. It moves in the negative direction for Democratic women and in the positive direction for Republican women. Thus, women governors in neighboring states are not serving as symbolic, easy to see, role models that women belong in the governor’s office.

The structure of the governor’s office influences women’s decision whether to run for governor. The index measuring the institutional structure of the governor’s office is positively and significantly correlated with a woman’s decision to run for governor for both Republicans and Democrats. The combined and cumulative effect of the presence of no pre-primary endorsement, not combining the governor and lieutenant governor on the same ticket, having gubernatorial term limits, having shorter terms, lower salary, and having public financing leads to more women on the primary ballot. This finding is of particular import as it indicates concrete structural changes that can be made that should lead to more women running for governor, something that Piscopo (Citation2019) argues is crucial to increasing women’s representation in elected offices.Footnote11

Our findings support previous research that shows the deterrent created by the presence of an incumbent. Incumbents often come to primaries with a war chest, name recognition, and a record of service to the state. This incumbency advantage is a barrier for all candidates, and we can see here that it impacts a woman’s decision to run or not. Democratic and Republican women are both less likely to run for governor when there is an incumbent, and this is true whether the incumbent is male or female. Examining statistical significance, the results are nuanced. For women in both parties the negative relationship between same party male incumbents is significant. In contrast, the relationship between same party women governors is only significant for Democratic women not Republican women. So, while women are less likely to run for governor when an incumbent from their party is present, Republican women are not deterred from running by the presence of a Republican woman governor at a statistically significant level. This finding is similar to King’s (Citation2019) finding that women are less likely to challenge an incumbent woman in a gubernatorial race, but our findings diverge in that we find this differs by party. This divergence could be due to the increase in gubernatorial candidates over the past few years.

Further, our results show open seats are not significantly related to the number of women Democratic or Republican candidates. Fox and Oxley (Citation2003) also found no significant relationship between an open seat and the presence of women running for office. Other variables, like the combined effect of the structure of the governor’s office, appear to matter more to the presence of women on a primary ballot than simply having an open seat.

The Year of the Woman is positive and significant for both parties, women in both parties were more likely to appear on a primary ballot for governor during this period. This finding is in line with data and news stories from this period which document the impact of events like redistricting and the Clarence Thomas nomination hearings, on women’s decision to run in state and national politics, as well as the importance of groups on both sides of the aisle raising money for women to run (Delli Carpini and Fuchs Citation1993). In 1992, 71 women won statewide executive office, bringing their overall share up to a bit over 20%, and that overall Republican woman fared better in these races than Democratic women (Nelson Citation1992). The growth of statewide candidates paralleled U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Gingrich’s well documented efforts to recruit more Republican women to run for Congress. (For example, see Feldmann Citation1995; Byrne Citation1994; Woodward Citation1994).

The nomination of Alaska’s Republican governor, Sarah Palin for Vice President in 2008 had a positive and significant impact on the presence of Republican women on gubernatorial primary ballots in 2009–2010. The impact was negative, but not significant for Democratic women. This finding is in line with journalistic accounts of the 2010 election which showed the impact Palin had on conservative women deciding to run for elective office (Spillius Citation2010).

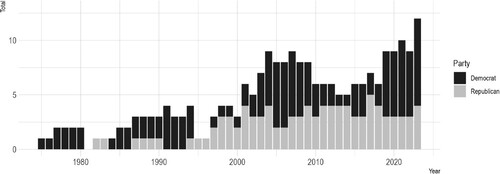

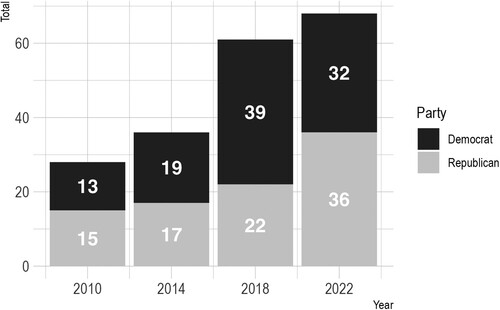

Gubernatorial elections held after Donald Trump’s 2016 election as president are positively associated with the presence of women on the ballot for both parties. This relationship is significant. This too is in line with journalistic coverage of the Trump effect, which argued he positively impacted the decision of both Republican and Democratic women to run (Hernández Citation2017; Kurtzleben Citation2018). Since Trump became president in 2017, the likelihood of a woman gubernatorial candidate has increased for both the Democrats and Republicans, though the incidence rate ratio is slightly higher than for Democrats. While women candidates for both parties have grown, the pattern differs as seen in . There was significant growth for Democratic women candidates in 2018 and more modest growth for Republican women candidates. The 2022 gubernatorial election showed a Republican women counter-surge and fewer Democratic women candidates compared to 2018.

Figure 6. Women gubernatorial candidates on the ballot by Party: 2010–2022, Major Election Years.

The Democratic percentage of the two-party vote in a state’s last gubernatorial election is positive but partisan balance doesn’t have a significant impact on women’s decision to run for governor. We do not find evidence that women are being run as sacrificial lambs. Elazar’s measure of cultural diversity (individualistic and moralistic, with traditionalistic as the excluded category) was not significant for either party. As expected, population is positively and significantly correlated with the more Democratic women on a gubernatorial primary ballot and negatively, though not significantly, correlated with the presence of Republican women on a gubernatorial ballot. The more populous a state, the more likely that a Democratic woman will run for governor. Looking at region, the Northeast, South and West are all positive in relation to the excluded region, the Midwest for both parties. However, only the West is significant and only significant for Republican women. The significance of the West is interesting as these states gave women the right to vote prior to the Nineteenth Amendment, partly to gain sufficient population for statehood. Manento and Schenk (Citation2021) found the same regional pattern in looking at the growth of women serving in state legislatures from 1975 to 2019.

Conclusions

Our research provides valuable, novel insights into when and where women run in gubernatorial primaries as well as showing that Democratic and Republican women approach the decision to run differently.

Today, Republican women are impacted by the pipeline in a way that Democratic women no longer appear to be. Republican women House members and Republican women state legislators exert a positive impact on Republican women running for governor. As the Republican pipeline began to fill in the 2000s and beyond, with more Republican women in masculine-defined executive offices, state legislatures, and the U.S. House, more Republican women consistently ran for governor. This does not mean that the pipeline does not matter for Democrats. Rather, Democrats had a sufficient number of women elected officials at the state and federal level beginning early on in the period of study. As Rhinehart, Geras, and Hayden (Citation2022, 160) note, “As a whole, the Democratic Party has placed a higher priority on identity policies. Democrats are more likely to believe there is a benefit to electing more women, and party elites have invested more heavily in organizations and resources to aid more women candidates than the GOP.” The number of Democrats in these offices has continued to grow and remain higher than Republicans, but in many states, the pipeline was sufficiently full to generate candidates more consistently, even though women did not become consistently successful in winning the governor’s office until recently.

Women gubernatorial candidates are not concerned about whether they are the first woman to run for governor in a state. The presence of a prior same-party woman governor does not influence women from either party to run for governor. Nor do women gubernatorial candidates look for role models when deciding whether or not to run. Women governors in neighboring states are not serving as symbolic, easy to see, role models that women belong in the governor’s office. Our findings here are in contrast to findings on the impact of role models encouraging more women state legislative candidates (Ladam, Harden, and Windett Citation2018). So, why don’t role models matter here? The answer may lie in the number of women who have served as governors thus far. Thus, it will be worthwhile to revisit this question in the near future as this current group of women governors terms out of office.

The institutional structure of the governor’s office impacts whether there will be women on a gubernatorial ballot. The index measuring the institutional structure of the governor’s office is positively and significantly correlated with a woman’s decision to run for governor for both Republicans and Democrats.

Open seats on their own do not lead to more women running for governor. And Republican women are not deterred from running by the presence of a Republican woman governor. Democratic women are significantly less likely to run against both men and women incumbents, while Republican women are only significantly less likely to run against men incumbents. Is this due to differences in party culture? Are Republican women more individualistic and thus more comfortable challenging a Republican woman governor whereas Democratic women are not? Does the Republican party discourage women running against a same-party male incumbent but is not concerned if they run against a same-party woman incumbent? There is research in this area (Elder Citation2021) and more will help answer this question.

Finally, political events impact whether women run for governor. The Year of the Woman led to more women from both parties running for governor. The nomination of Alaska’s Republican governor, Sarah Palin for Vice President in 2008 had a positive and significant impact on the presence of Republican women on gubernatorial primary ballots in 2009-2010. And gubernatorial elections held after Donald Trump’s 2016 election as president are positively and significantly associated with the presence of women on the ballot for both parties. The number of both Democratic and Republican women candidates have notably increased since 2016. We see this first with Democrats in 2018 and more recently with Republicans. We cannot know whether this increase of women candidates is a blip or a permanent change. Thus, revisiting the impact of Trump and the growth of women candidates will be needed.

In sum, there has been a significant increase in Democratic and Republican women running for governor and being elected governor. Both the growth in women candidates and women governors matter. We know that diversity in government worldwide is impactful. Gender diversity influences what legislation is introduced, which bills become law, how legislators interact with each other, how laws are implemented, and more.Footnote12 Thus, it is important that women serve at as close to parity with men as possible. However, recent research on political socialization indicates that even today, due to the combined effects of gender socialization and political socialization, girls do not see politics in their future (Bos et al. Citation2022). This is troubling.

It is clear that simply having more women run does not, on its own, translate to electing a woman governor. And why have some states repeatedly elected women governors and some have elected none? For example, Arizona has had four, more than any other state, Arizona three, and California none. Arizona has no lieutenant governor, and the secretary of state is next in line to be governor. Two of the four Arizona women governors have ascended from the position of secretary of state, a position that is masculine defined. Is their lack of a lieutenant governor impactful on women becoming governor in Arizona? California has had the largest number of women run for governor but has never elected a woman governor. The most populous states are among the least likely to elect women governors. Six of the ten most populous states – California, Florida, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, and Georgia – have yet to elect a governor. Of this group, only Michigan has elected two women governors. Why? Is it the media market and its inherent costs? California has some of the most active groups recruiting and training women to run. Rather, the problem may lie in the nuances of multiple, expensive media markets (Rosenhall Citation2020), state culture (Windett Citation2011), the importance of fundraising, and possibly in state party culture. Thus, recruitment is not enough. As Bernhard and de Benedictis-Kessner (Citation2021) and Piscopo (Citation2019) argue, recruitment is not the holy grail for increasing the number of women running. Thus, while recruitment is needed, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for women running and winning.

The role of money and fundraising in gubernatorial races is understudied and is an important avenue for further inquiry. Political science knows quite a bit about women, fundraising, and legislative races but much less about women, fundraising, and gubernatorial elections. The findings on women and fundraising and legislative races may not play out the same in gubernatorial races, and research by Sanbonmatsu, Rogers, and Gothreau (Citation2020) indicates it does not. They find that, “[r]egardless of whether mean or median contribution totals are analyzed, we see that women’s receipts are lower than men’s on average. This gender effect can be observed within both parties (355).” Further, they find that women do not self-finance at the same rate as men, which they point out is not surprising given gender gaps in wealth and income between men and women. And the fundraising picture is even more bleak for women of color,

we find that mean receipts were lower for the women of color, adjusted for state population: 0.26 USD for women of color compared with 0.42 USD for white women. The lower receipts for women of color is concerning and suggests the need for more analysis. (356)

So, what can states do to facilitate women running for governor? Women candidates are strategic and continue to be sensitive to the environment around them in the way that the literature indicates that men are not. Piscopo’s (Citation2019) argues that “Women, and particularly women of color, accurately gauge how electoral institutions, party organizations, and entrenched ideas about men’s and women’s appropriate roles raise their costs of running relative to men, creating a profoundly uneven playing field (819).” States and parties can alter structural elements that our research shows deter women from running. Gubernatorial tickets can be decoupled, pre-primary endorsements can be eliminated, and public campaign financing can be bolstered, for example. Parties can adopt rules and facilitate norms that are favorable to women, working to end the old-boy network that still characterizes much of party culture in the U.S.

In sum, structural and institutional still exist which deter women from running for governor. While filling the pipeline is an important part of creating parity between men and women candidates for governor, our research shows that the pipeline is easier to fill in some states than others, and ultimately, the pipeline alone is not enough.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Only 49 women have ever held the position of governor. Eighteen states have never had a woman governor (California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin).

2 We have chosen to use the more inclusive terms of “woman” and “women” in this article, instead of “female” and “females”. Current grammatical trends are moving in the direction of using the nouns “woman” and “women” as adjectives, in place of “female” and “females”.

3 There were 53 gubernatorial elections during the four-year period. New Hampshire and Vermont have two year gubernatorial terms, and held two elections during the period. California held a recall election in 2021 in addition to their regularly scheduled election in 2022.

4 Massachusetts elected the first two-woman ticket in 2022. Maura Healy was elected governor and Kimberly Driscoll was elected lieutenant governor.

5 Only Utah and Virginia Republicans used conventions during this period. All states have separate party candidate selection except Louisiana which has a blanket primary with a runoff election if no candidate received a majority of the vote.

6 We exclude Nebraska, who holds non-partisan legislative elections and the two 2003 and 2021 California recall elections, which have no primary, and have loose ballot qualification rules.

7 Exceptions are California, which held recall elections in 2003 and 2021, Oregon which held a special election in 2016 to fill an unexpired term, and Rhode Island who elected governors to two years prior to 1994.

8 One question a reader might have is why we have not looked at race and ethnicity. No data on the race and ethnicity of gubernatorial candidates exists to our knowledge. We have gathered this data for candidates in elections going back to 2018. We hope to expand this back over time as available and use it in future analyses. One current governor, Michelle Lujan Grisham (D-NM) is Hispanic. There were a record black women nominees in governor’s races in 2022. According to the Center for American Women and Politics, there were at least five Asian American/Pacific Islander women running in major parties in 2022. At least 12 Black women and six Hispanic women ran for governor in 2022. Each of these was a record (CAWP Citation2022).

9 We used Jensen and Beyle’s Gubernatorial Campaign Expenditure Database (https://jmj313.web.lehigh.edu/node/9) and Windett’s data which was generously shared by the author.

10 The analysis was run in R using the glm.nb command in the MASS package (Venables and Ripley Citation2002). Testing found our data were not within the bounds of the Poisson distribution, so the more general negative binomial regression model was used. Random effects for both years and states were examined. Testing found the years only model was most efficient and eliminating states had no substantive impact on the model.

11 Important to note is that while lower gubernatorial salaries, in part, makes it more likely that women will run for governor, we are not arguing for a lowering of gubernatorial salaries. Further, as Bernhard and de Benedictis-Kessner (Citation2021) find in their research, women with primary breadwinning responsibility are less likely to choose to run, thus elected offices with lower salaries may ultimately lead to only certain types of women choosing to run, a decidedly negative outcome.

12 For an overview of the research on the impact of women in politics worldwide see Henderson and Jeydel (Citation2013).

References

- Bardwell, Kedron. 2002. “Money and Challenger Emergence in Gubernatorial Primaries.” Political Research Quarterly 55 (3): 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290205500308.

- Bernhard, Rachel, and Justin de Benedictis-Kessner. 2021. “Men and Women Candidates Are Similarly Persistent After Losing Elections.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (26): e2026726118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2026726118.

- Bernhard, Rachel, Shauna Shames, and Dawn Langan Teele. 2021. “To Emerge? Breadwinning, Motherhood, and Women’s Decisions to Run for Office.” American Political Science Review 115 (2): 379–394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000970.

- Besley, Timothy. 2004. “Paying Politicians: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of the European Economic Association 2 (2/3): 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1162/154247604323067925.

- Bos, Angela L., Jill S. Greenlee, Mirya R. Holman, Zoe M. Oxley, and J. Celeste Lay. 2022. “This One’s for the Boys: How Gendered Political Socialization Limits Girls’ Political Ambition and Interest.” American Political Science Review 116 (2): 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001027.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.” Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.

- Byrne, Carol. 1994. “Finally, a Full Place in Politics; Women's Fund-raising - and Odds of Winning - are Up.” Star Tribune, October 4, 1994.

- Caress, Stanley M. 1999. “The Influence of Term Limits on the Electoral Success of Women.” Women & Politics 20 (3): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1300/J014v20n03_03.

- Carnes, Nicholas, and Eric R. Hansen. 2016. “Does Paying Politicians More Promote Economic Diversity in Legislatures?” American Political Science Review 110 (4): 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305541600054X.

- Carpini, Michael, and Ester Fuchs. 1993. “The Year of the Woman? Candidates, Voters, and the 1992 Elections.” Political Science Quarterly 108 (1): 29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2152484.

- Carroll, Susan J., and Krista Jenkins. 2001. “Unrealized Opportunity? Term Limits and the Representation of Women in State Legislatures.” Women & Politics 23 (4): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J014v23n04_01.

- Center for American Woman and Politics. 2022. Data on 2022 Women Candidates by Race and Ethnicity. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for American Woman and Politics. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/blog/data-2022-women-candidates-race-and-ethnicity.

- Crowder-Meyer, Melody. 2013. “Gendered Recruitment Without Trying: How Local Party Recruiters Affect Women’s Representation.” Politics & Gender 9 (4): 390–413. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X13000391.

- Eagleton Center on the American Governor. 2023. “When Governors Seek Re-Election.” Eagleton Center on the American Governor (blog), Accessed March 20, 2023. https://governors.rutgers.edu/when-governors-seek-re-election/.

- Elazar, Daniel J. 1994. The American Mosaic: The Impact of Space, Time, and Culture on American Politics. 1st edition. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Elder, Laurel. 2021. The Partisan Gap: Why Democratic Women Get Elected but Republican Women Don’t. New York: NYU Press.

- Feldmann, Linda. 1995. “When Republican Women In House Talk, Gingrich Is Among the First to Listen.” Christian Science Monitor, March 30, 1995.

- Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2011. “Gendered Perceptions and Political Candidacies: A Central Barrier to Women’s Equality in Electoral Politics.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (1): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00484.x.

- Fox, Richard L., and Zoe M. Oxley. 2003. “Gender Stereotyping in State Executive Elections: Candidate Selection and Success.” The Journal of Politics 65 (3): 833–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00214.

- Henderson, Sarah L., and Alana S. Jeydel. 2013. Women and Politics in a Global World. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hennings, Valerie M., and R. Urbatsch. 2015. “There Can Be Only One (Woman on the Ticket): Gender in Candidate Nominations.” Political Behavior 37 (3): 749–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9290-4.

- Hennings, Valerie M., and R. Urbatsch. 2016. “Gender, Partisanship, and Candidate-Selection Mechanisms.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 16 (3): 290–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440015604921

- Hernández, Kristian. 2017. Surge of Women Run for Office in First Major Races Since Trump’s Win. Washington, DC: Center for Public Integrity. Accessed November 6, 2017. http://publicintegrity.org/politics/state-politics/surge-of-women-run-for-office-in-first-major-races-since-trumps-win/.

- Holman, Mirya R. 2017. “Women in Local Government: What We Know and Where We Go from Here.” State and Local Government Review 49 (4): 285–296.

- Hopkins, David A. 2022. “Analysis | Trump’s Surprising Legacy: More Female Candidates – in Both Parties.” Bloomberg News, September 26, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-09-26/campaign-2022-more-democrats-and-republicans-are-candidates?embedded-checkout=true.

- Jensen, Jennifer M., and Thad Beyle. 2003. “Of Footnotes, Missing Data, and Lessons for 50-State Data Collection: The Gubernatorial Campaign Finance Data Project, 1977-2001.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 3 (2): 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/153244000300300204.

- King, Helen. 2019. “Women in the Governor’s Mansion: Breaking the Barrier to Competition.” Theses and Dissertations, July. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5478.

- Kurtzleben, Danielle. 2018. “Resisting Trump, Surge In Democratic Women Ask: How Do I Run For Office?” NPR, January 7, 2018, sec. Politics. https://www.npr.org/2018/01/07/575369861/resisting-trump-surge-in-democratic-women-ask-how-do-i-run-for-office.

- Ladam, Christina, Jeffrey J. Harden, and Jason H. Windett. 2018. “Prominent Role Models: High-Profile Female Politicians and the Emergence of Women as Candidates for Public Office.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (2): 369–381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajps.2018.62.issue-2.

- Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard L. Fox. 2018. “A Trump Effect? Women and the 2018 Midterm Elections.” The Forum 16 (4): 665–686. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2018-0038.

- Manento, Cory, and Marie Schenk. 2021. “Role Models or Partisan Models? The Effect of Prominent Women Officeholders.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 21 (3): 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2020.3.

- Nelson, W. Dale. 1992. “Women Gained in Wide Range of State Office Races.” Associated Press, November 5, 1992, AM cycle edition, sec. Political News.

- Niven, David. 1998. “Party Elites and Women Candidates: The Shape of Bias.” Women and Politics 19 (2): 57–80.

- O’Regan, Valerie, and Stephen J. Stambough. 2011. “The Novelty Impact: The Politics of Trailblazing Women in Gubernatorial Elections.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 32 (2): 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2011.562137.

- O’Regan, Valerie, and Stephen Stambough. 2016. “Political Experience and the Success of Female Gubernatorial Candidates.” Social Sciences 5 (2): 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5020016.

- Ostermeier, Eric. 2021. “Returning Home: How Often Do US Senators Become Governor.” Smart Politics (blog).

- Oxley, Zoe M., and Richard L. Fox. 2004. “Women in Executive Office: Variation Across American States.” Political Research Quarterly 57 (1): 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290405700109.

- Pew Research Center. 2023. “Republican Gains in 2022 Midterms Driven Mostly by Turnout Advantage.” Pew Research Center, July 12, 2023.

- Piscopo, Jennifer M. 2019. “The Limits of Leaning in: Ambition, Recruitment, and Candidate Training in Comparative Perspective.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7 (4): 817–828. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1532917.

- Rhinehart, Sarina, Matthew J. Geras, and Jessica M. Hayden. 2022. “Appointees versus Elected Officials: The Implications of Institutional Design on Gender Representation in Political Leadership.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 43 (2): 152–168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2022.1984143.

- Rohde, David W. 1979. “Risk-Bearing and Progressive Ambition: The Case of Members of the United States House of Representatives.” American Journal of Political Science 23 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110769.

- Rosenhall, Laurel. 2020. “California Women Smash Ceilings in National, Not State, Politics | CalMatters.” CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/politics/california-election-2020/2020/11/california-women-smash-ceilings-national-politics-not-state/.

- Sanbonmatsu, Kira, and Kathleen Rogers. 2020. “Advancing Research on Gender and Gubernatorial Campaign Finance.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 41 (3): 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2020.1804793.

- Sanbonmatsu, Kira, Kathleen Rogers, and Claire Gothreau. 2020. The Money Hurdle in the Race for Governor. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics.

- Spillius, Alex. 2010. “Sarah Palin Effect Sees Record Number of Women Stand as Republican Candidates.” Newspaper. The Telegraph. August 29, 2010. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/sarah-palin/7970684/Sarah-Palin-effect-sees-record-number-of-women-stand-as-Republican-candidates.html

- Stambough, Stephen J., and Valerie R. O’Regan. 2007. “Republican Lambs and the Democratic Pipeline: Partisan Differences in the Nomination of Female Gubernatorial Candidates.” Politics and Gender 3 (3): 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X0700030X.

- Thomsen, Danielle M, and Aaron S King. 2020. “Women’s Representation and the Gendered Pipeline to Power.” American Political Science Review 114 (4): 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000404.

- Venables, William N., and Brian D. Ripley. 2002. Modern Applied Statistics with S. Fourth edition. New York: Springer. https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/.

- Windett, Jason Harold. 2011. “State Effects and the Emergence and Success of Female Gubernatorial Candidates.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 11 (4): 460–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440011408930.

- Windett, Jason. 2014. “Differing Paths to the Top: Gender, Ambition, and Running for Governor.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 35 (4): 287–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2014.955403.

- Woodward, Calvin. 1994. “GOP Women Made Big Splash at State Level, Narrowing Gap with Democrats.” Washington Dateline, Associated Press, December 2, 1994, sec.