ABSTRACT

Cervical cancer (CC) is reported as the second-most common female cancer worldwide, of which 99% is caused by persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. HPV vaccine protects against HPV infection and most cases of CC, which has only been introduced for a short time in mainland China. This study aimed to evaluate the attitude and practice related to HPV infection and vaccination among students at secondary occupational health school (SOHS) in China. We conducted a cross-sectional study in Southern China where data of 2248 participants were collected through questionnaires to estimate attitude and practice of students. Only 4.1% believed they were easily infected by HPV, 38.2% were willing to receive HPV vaccine and 30.8% intended to do regular screening of HPV infection in the future. Students in the second grade (OR = 1.51, 95%CI [1.25, 1.81]) and third grade (OR = 3.99, 95%CI [2.53, 6.27]) were more willing to take HPV vaccine compared to students in the first grade. Among the non-vaccinated participants, the most frequent reason for not receiving HPV vaccine was insufficient knowledge about HPV (91.1%). Characteristics of higher grade, personal education before enrollment and academic performance, medical specialty, history of sex experience and HPV vaccine and family history of other cancers were associated with higher attitude scores (p < .05). Considering the increasing prevalence of HPV infection and the need of improvement in attitude and practice toward HPV, more education about HPV infection and vaccination should be incorporated into school curriculum.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one kind of viruses with double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and transmissible by risky sexual behavior through micro-abrasion in mucosa,Citation1 which is the most common virus in human sexually transmitted infection.Citation2 Therefore, it is assessed that the majority of human being will be infected with HPV at some moment during their lives.Citation2 Owing to the fact that HPV infection is commonly asymptomatic, most infected people will not seek medical treatment.Citation3 The cervical stratified squamous epithelium on host basal cell layer were infected by HPV and then the phagocytosis of these cells induces viral replication.Citation4 Nearly, 200 subtypes of HPV have been found,Citation5 and those which can integrate their genetic material into host genome, then interfere normal cell cycle and convert normal cells into cancer ones are divided into high-risk HPV, while low-risk HPV (HPV 6 and 11) cannot do these and they are associated with 90% of cases of genital warts.Citation1,Citation6,Citation7 Among high-risk HPV subtypes, HPV 16 and 18 protrude and are highly correlated with genital cancers, especially, with cervical cancer (CC).Citation8 Persistent HPV infection is the inevitable cause of invasive CC and cervical precancerous lesions.Citation9

CC is one of the most common cancers among women and it is the leading cause of female death from cancers in developing countries.Citation10 In 2020, the estimated number of deaths in CC was 59060 in China, which made China have the second largest count of deaths in CC worldwide,Citation11 and the prevalence rate (5-year) of CC was 42.1/100000 in China.Citation12 CC can cause wasting of a lot of manpower, material, and financial resources, and bring a devastating blow to a family. Most patients of CC have no symptoms and thus prevention and early diagnosis of this cancer are very essential. Fortunately, the Pap test can help early find of CC and, at best, three types of vaccines against HPV infection are presently available in China including Cervarix, Gardasil, and Gardasil 9, which can protect against high-risk types of HPV. In fact, the HPV vaccines have only been introduced for a short time in mainland China. There have been surveys on the attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination in different countries among various population.Citation13,Citation14 In China, studies were conducted among medical undergraduates and women;Citation15,Citation16 whereas, researches are still absent among students at secondary occupational health school (SOHS) who are the targets of the HPV vaccine, most of whom are majored in medical specialty. Thus, studies focused on attitude and practice of HPV infection and vaccination among students at SOHS are essential to assess the effect of past health education and implement the HPV vaccine.

This cross-sectional study was carried out to estimate attitude and practice of HPV infection and vaccination and explore related demographic characteristics and other related factors among students at SOHS. Besides, spreading correct attitude and practice regarding HPV infection and vaccination is helpful for provision of relevant information to program implementers and further acceptance of all measures for CC prevention in population.

Methods

Design and participants

This cross-sectional study was carried out among students at SOHS. A single population proportion formula was used to calculate the sample size at a 0.03 margin of error, 95% confidence level and a 16.8% rate of HPV awareness with a 30% nonresponse rate. The minimum sample size was 776 for this study on the basis of assumption above. A two-stage sampling technique was used, and data collection was through questionnaires on the WeChat Platform Application. First, stratified sampling was employed for medical and non-medical classes. Second, cluster sampling was used to the selected classes. The final collected sample was consisted of 2248 participants, 86.8% of whom were majored in medical specialty.

Measurement

The questionnaires consisting of three parts were developed to obtain respondents’ demographic information, attitude, and practice about HPV infection and vaccination in this study. Respondents’ demographic characteristics were in the first part of the questionnaires, followed by the second part about attitude status with 14 items and the third part with 8 items displaying practice about HPV infection. The responses of 22 questions were scored as “Yes” (3 points), “Not sure” (2 points), and “No” (1 point). The alpha value of Cronbach for the second part relating attitude toward HPV infection and vaccination, and the third part showing practice about HPV infection of the questionnaires were 0.818 and 0.728, respectively. The survey was performed anonymously from September to December 2019 within the classrooms on a batch basis in the school.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval to perform the survey was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, China (SUMC-2019-62). In addition, a consent form was obtained to further guarantee their voluntary participation and all the respondents were assured that all data would be confidential at all the time in our present study.

Data collection and statistical analyses

All the collected data were then entered in a spreadsheet and all statistical analyses were progressed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics including mean and standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were used to report respondents’ characteristics and HPV-related questions in terms of attitude and practice. One-way ANOVA was used to compare mean scores of attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination. The chi-square test was used to analyze the differences in the responses to the questionnaire. Moreover, multiple linear regression analysis was used to estimate the predictors among demographic characteristics of the attitude and practice scores. Responses of “Not Sure” were recoded as “No” in the multivariate logistic analysis, which was conducted to evaluate the associated characteristics of four questions regarding attitude and practice with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated. Throughout the survey, p < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic profile

Responses of 2248 students were collected and analyzed making this study a 100% response rate. Most of the respondents were female (81.0%), younger than 16 years old (60.5%) and majored in medical specialty (86.8%). More than half of students were in their first year (52.8%), followed by second year (42.9%), and third year (4.3%). The majority of students had no family history of CC (98.7%), family history of other cancer (87.2%), and sexual experience (95.1%). Among these respondents, more than 60% had never received HPV vaccination ().

Table 1. Participants’ attitude and practice scores about HPV infection and vaccination stratified by their characteristics (n = 2248)

Test items of attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination

In this study, we explored the respondents’ willingness to know more about HPV, more than half of them wished to attend activities for HPV prevention (53.7%). About 63% of respondents believed that regular screening was helpful for early detection of CC. Approximately three-fifths of participants considered that CC is preventable; however, only 30.6% of them believed that HPV vaccine can prevent CC. In terms of the efficacy of HPV vaccine against HPV infection, percentage of positive attitude (44.2%) was roughly equal to that of neutral attitude. As for the willingness to take HPV vaccine, not only the rough percentage of favorable attitude (40%) but also that neutral attitude (50%) were similar whether it was for free.

Among items of practice toward HPV infection, almost 60% of the participants initiated to know how to prevent CC (55.3%) and HPV infection (58.4%). Almost 50% of the respondents would encourage their family or friends to do screening of HPV infection (47.8%), but only 30.8% of them would do regular screening themselves. The majority of the respondents would have avoided early sexual experience if there had been a choice (80.8%) and would take protective measures when having sex in the future ().

Table 2. Participants’ attitude and practice on test items about HPV infection and vaccination (n = 2248)

Descriptive analysis of reasons for not being vaccinated

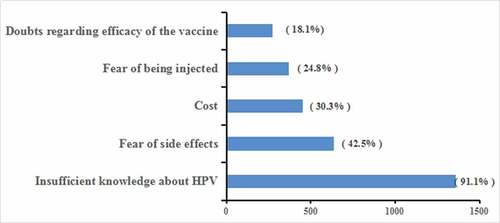

As for the reasons for not being vaccinated among those participants who had never taken HPV vaccination, the results most frequently indicated insufficient knowledge about HPV (91.1%), followed by fear of side effects (42.5%), cost (30.3%), fear of being injected (24.8%), and doubts regarding efficacy of the vaccine (18.1%) ().

Partial attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination stratified for characteristics

In the univariate analysis, it was found that male students more believed regular screening of HPV infection helped early diagnosis of CC (p < .05). The participants who were younger than 16 years old were more likely to believe Q6, 9, 12, 13 and do Q19, 22. Students in higher grades were more possible to believe Q5, 6, 9, 12, 13 and do Q19, 22 (p < .05). Students living in urban were associated with the increased willingness to take HPV vaccine and would do regular screening of HPV infection in the future (p < .01). Academic performance reached significance, which indicated students with better academic performance more believed Q6. HPV-vaccinated respondents displayed that they were more likely to propagate knowledge of HPV infection to their family or friends and encourage them to do screening of HPV infection and take protective measures when having sex in the future (p < .05) ().

Table 3. Participants’ positive answers to attitude and practice of HPV infection and vaccination stratified by characteristics

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for attitude and practice on HPV infection and vaccination

Further multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated students’ characteristics associated with responses to Q12, 13, 18, and 19. As for Q12, female students were less likely to believe in safety and effectiveness of HPV vaccine (OR = 0.68, 95%CI [0.54, 0.86]) than males; increased belief was statistically associated with older age (p < .05); participants in the second or third grade were more likely with higher belief (p < .05) compared to students in the first grade; the respondents majored in medical specialty were more likely to believe in Q12 (OR = 1.62, 95%CI [1.21, 2.17]). For Q13, participants in the second (OR = 1.51, 95%CI [1.25, 1.81]) or third (OR = 3.99, 95%CI [2.53, 6.27]) grade would more likely take HPV vaccine compared to those participants in the first grade; medical students were 1.89 times more likely to take the vaccine compared to their counterparts. Regarding Q18, participants who were more likely to do regular screening of HPV infection were majored in medical specialty, living in urban, having higher paternal education and having received HPV vaccine (p < .05). For Q19, major, residential area, academic performance and having received HPV vaccine (p < .05) were found to be significant factors associated with participants’ encouragement of HPV infection screening to their family and friends ().

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression analysis for items of attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination

Factors and predictors of attitude and practice scores regarding HPV infection and vaccination

Statistically, the mean attitude score was 32.76 ± 4.73 (possible scores: 14–42), which indicates a relatively positive attitude to HPV infection and vaccination. Generally, respondents who were male, younger than 16 years old, majored in non-medical specialty, having lower grade, personal education level before enrollment, family income, academic performance and sex experience, having no family history of CC and other cancers and having never received HPV vaccine showed a more negative attitude compared with their counterparts (p < .05) (). In the multiple linear analysis model, characteristics of higher grade, personal education before enrollment and academic performance, medical major and having sex experience, family history of other cancers and history of HPV vaccine were significant predictors for higher attitude scores (p < .05) ().

Table 5. Multiple linear regression analysis for factors influencing attitude and practice scores

The mean practice score was 19.67 ± 3.25 (possible scores: 8–24), displaying positive practice of the participants to HPV infection. Statistical significance was found among characteristics of gender, grade, major, academic performance, family history of other cancers, and history of HPV vaccine in practice scores (). The multiple linear regression indicated that the participants who were female, majored in medical specialty, with higher academic performance and having history of other cancers and history of HPV vaccine were more likely to have higher practice scores (p < .05) ().

Discussion

This was a cross-sectional study involved 2248 students at SOHS to investigate their attitude and practice toward HPV infection and vaccination in Southern China. At 100%, the response rate of our study was fairly high. As the deficiency of surveys with similar demographic and environment, direct comparisons could not be displayed.

The majority of the participants in this study were female, with no sex experience and between the ages of 13 and 20 years old, which is the optimum age, sexually active or pre-active stage, to take HPV vaccine in mainland China.Citation17 As a matter of fact, half of females get HPV infection within 2 years once they start sex,Citation18 and there is a trend toward earlier and more dangerous sexual behaviors in China.Citation19 Studies have shown the recommendations of health-care providers played a highly important role in the positive attitude and acceptability toward HPV vaccine and screening of HPV infection.Citation20–22 Most of the participants were majored in medical specialty and would be the future health-care providers who perform key roles in implementing vaccination programs and screening for CC prevention. Therefore, understanding the attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination among students at SHOS is helpful to prevent CC in this and even the general population.

In this study, one-third of the participants already received at least one dose of HPV vaccine prior to the study, which was higher than the studies conducted in Lebanon and India where only 16.7% and 6% of the students were vaccinated,Citation23,Citation24 but lower than that of Germany (67%) and Hong Kong (47.2%).Citation25,Citation26 The reported reasons for non-vaccinated respondents were insufficient knowledge, fear of side effects, cost, fear of being injected and doubts regarding efficacy of the vaccine. The most main barrier to vaccination was the lack of HPV-related knowledge, which was in agreement with some overseas studies.Citation27,Citation28 There were a couple of studies suggesting concerns for not being vaccinated also lied to the safety and efficiency of the vaccine similar to our findings.Citation16,Citation22,Citation29,Citation30 Our research was in line with a published study conducted among secondary-school students for fear of being injected due to the pain in its delivery profile.Citation31 No matter whether the HPV vaccine was free or not, the willingness of the respondents in our study to be vaccinated was similar, indicating that the price of the vaccine had little impact on the attitude of the students toward vaccination, which was in agreement with a published literature.Citation16 However, another published literature indicated the percentage of willingness to be vaccinated for free (62.0%) was more than that by their payment (35.6%) among Cambodian women.Citation32 Our study found that the factors associated with positive attitude toward HPV vaccine included higher grades, medical specialty, higher personal education before enrollment, family income, sex experience, and family history of other cancers. Interestingly, the willingness to receive HPV vaccine did not depend on age and family history of CC but depended on educational status, which was contrary with a published study among Chinese women.Citation33

More than half (63.6%) of the participants believed that HPV infection was a serious disease, which was less than the 87.4% in South India.Citation23 The results reflected that 1331 (59.2%) respondents believed that CC was preventable, which was lower than 78% in a previous cross-sectional survey conducted in Ethiopia.Citation34 Fewer (30.6%) of them believed that CC was preventable by HPV vaccine, which could be due to the lack of awareness and knowledge about HPV vaccine and the relation between HPV and CC. Of the participants, 79.3% believed that early diagnose and treatment was good, which was higher than a study in Qatar in which 64.8% were with the same belief.Citation35 The study also indicated that only 4.1% of the students believed that they were at risk of HPV infection, which was consistent with an investigation among Spanish adolescents,Citation36 but lower than the 36% among nursing students in another survey.Citation37 Our studies suggested that more than half of the students would likely know more about HPV (66.4%) and attend activities for HPV prevention (53.7%). This reflected that the attitude about HPV infection and vaccination among our participants still needed improvement.

In the present study, the factors of male, higher grades, medical specialty, higher maternal education level, family history of other cancer and having received vaccination were associated with more positive attitude toward the safety and efficiency of HPV vaccine. Students with characteristics above might be more knowledgeable about HPV as a previous study identified that positive attitude toward the safety of the vaccine was correlated with good knowledge about HPV infection and vaccination.Citation38 Less than 60% of the students initiated to know how to prevent CC and HPV infection and propagate knowledge of HPV infection to others. Only 30.8% of the participants would do regular screening of HPV infection, which was lower than (56.6%) a study carried out among secondary school students in Nigeria,Citation39 while 47.8% of them would recommend the screening to their family and friends. According to the analysis of multivariable logistic regression, students with characteristics of medical specialty, living in urban, having better academic performance, sexual experience, family history of other cancers, and history of HPV vaccination were more likely to encourage their family and friends to do screening. A clear majority of the respondents claimed that they would have avoided early sexual behavior and would take protective measures in sex, which presented a good phenomenon as sexual risk behavior was one of the most important risk factors of HPV infection.Citation38

In the multiple linear regression analysis, the factors of grade, major, academic performance, family history of other cancers, and history of HPV vaccine were statistically independent predictors for both attitude and practice scores. A published literature together with ours indicated vaccinated students displayed more positive attitude than their counterparts.Citation37 A previous research in Lebanon suggested that awareness of HPV itself was a significant predictor of more positive attitude scores and their survey itself was a case of spreading awareness that statistically increased the mean intention score after the respondents went through it.Citation24 The total status of attitude and practice about HPV infection and vaccination was at medium. However, as the participants were at the right age of HPV vaccine and especially most of our participants would be health-care providers who played an important role in recommending HPV vaccine, their attitude and practice toward HPV infection and vaccination should be systematically improved. According to Health Belief Model and multiple studies,Citation25,Citation33,Citation40,Citation41 better knowledge of HPV infection was associated with more positive attitude toward HPV vaccine, then increased the acceptability of the vaccine and improved the intention to recommend the vaccine. A prior study confirmed that the most effective method to improve the knowledge status was education,Citation42 which suggested that there was potential for improvement in medical education curriculum.

This study has several limitations. This was a cross-sectional study which limited us to infer causal relationship on the basis of the observed associations. Secondly, the participants possibly tended to give socially desirable responses to some sensitive questions. Finally, the respondents should have been investigated about the history of sexually transmitted diseases in case that those with a positive history have more positive attitude to take HPV vaccine and do screening of HPV infection.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study found that the attitude and practice level concerning HPV infection and vaccination among students at secondary health occupational school in mainland China was at medium. As China had ranked the second in death count of CC and most of the participants would be the future health-care providers, it was essential to incorporate systematical education-related HPV infection and vaccination into school curriculum for eventual acceptability of HPV vaccine among the students and the general population.x

Abbreviations

| HPV | = | Human Papillomavirus |

| CC | = | Cervical Cancer |

| SOHS | = | Secondary Occupational Health School |

| OR | = | Odd Ratio |

| 95% CI | = | 95% Confidence Interval |

| RMB | = | Renminbi (Chinese currency) |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to perform the survey was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of Shantou University Medical College (SUMC-2019-62). In addition, a consent form was obtained to further guarantee their voluntary participation in our present study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the students for taking part in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Functional TV. Roles of E6 and E7 oncoproteins in HPV-induced malignancies at diverse anatomical sites. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(10). doi:10.3390/cancers8100095.

- Boda D, Docea AO, Calina D, Ilie MA, Caruntu C, Zurac S, Neagu M, Constantin C, Branisteanu DE, Voiculescu V, et al. Human papilloma virus: apprehending the link with carcinogenesis and unveiling new research avenues (Review). Int J Oncol. 2018;52(3):637–55. doi:10.3892/ijo.2018.4256.

- Moscicki AB. Impact of HPV infection in adolescent populations. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(6 Suppl):S3–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.011.

- Widjaja VN. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes of human papillomavirus (HPV) among private university students- Malaysia perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(7):2045–50. doi:10.31557/apjcp.2019.20.7.2045.

- Li Y, Xu C. Human papillomavirus-related cancers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1018:23–34. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5765-6_3.

- Mcgraw SL, Ferrante JM. Update on prevention and screening of cervical cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(4):744–52. doi:10.5306/wjco.v5.i4.744.

- Muñoz N, Bosch FX, De Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):518–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641.

- Serrano B, Alemany L, Tous S, Bruni L, Clifford GM, Weiss T, Bosch FX, De Sanjosé S. Potential impact of a nine-valent vaccine in human papillomavirus related cervical disease. Infect Agent Cancer. 2012;7(1):38. doi:10.1186/1750-9378-7-38.

- Schiffman M, Wentzensen N. Human papillomavirus infection and the multistage carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):553–60. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-12-1406.

- Cheikh A, El Majjaoui S, Ismaili N, Cheikh Z, Bouajaj J, Nejjari C, El Hassani A, Cherrah Y, Benjaafar N. Evaluation of the cost of cervical cancer at the National Institute of Oncology, Rabat. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23:209. doi:10.11604/pamj.2016.23.209.7750.

- World Health Organization. Estimated number of deaths in 2020, cervix uteri, females, all ages. Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2021 [accessed 2021 April 30]. https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

- World Health Organization. Esitimated number of prevalent cases (5-year) as a proportion in 2020, cervix uteri,females, all ages. Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2021 [accessed 2021 April 30]. https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

- Olubodun T, Odukoya OO, Balogun MR. Knowledge, attitude and practice of cervical cancer prevention, among women residing in an urban slum in Lagos, South West, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;32:130. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.32.130.14432.

- Mapanga W, Girdler-Brown B, Singh E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of young people in Zimbabwe on cervical cancer and HPV, current screening methods and vaccination. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):845. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-6060-z.

- Abudukadeer A, Azam S, Mutailipu AZ, Qun L, Guilin G, Mijiti S. Knowledge and attitude of Uyghur women in Xinjiang province of China related to the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:110. doi:10.1186/s12957-015-0531-8.

- Fu CJ, Pan XF, Zhao ZM, Saheb-Kashaf M, Chen F, Wen Y, Yang CX, Zhong XN. Knowledge, perceptions and acceptability of HPV vaccination among medical students in Chongqing, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(15):6187–93. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.15.6187.

- Zhang SK, Pan XF, Wang SM, Yang CX, Gao XH, Wang ZZ, Li M, Ren ZF, Zhao FH, Qiao YL. Perceptions and acceptability of HPV vaccination among parents of young adolescents: a multicenter national survey in China. Vaccine. 2013;31(32):3244–49. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.046.

- Lenselink CH, Gerrits MM, Melchers WJ, Massuger LF, Van Hamont D, Bekkers RL. Parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;137(1):103–07. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.02.012.

- Zhao FH, Tiggelaar SM, Hu SY, Xu LN, Hong Y, Niyazi M, Gao XH, Ju LR, Zhang LQ, Feng XX, et al. A multi-center survey of age of sexual debut and sexual behavior in Chinese women: suggestions for optimal age of human papillomavirus vaccination in China. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(4):384–90. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2012.01.009.

- Barnard M, George P, Perryman ML, Wolff LA. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and uptake in college students: implications from the precaution adoption process model. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182266. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182266.

- Ganry O, Bernin-Mereau AS, Gignon M, Merlin-Brochard J, Schmit JL. Human papillomavirus vaccines in Picardy, France: coverage and correlation with socioeconomic factors. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2013;61(5):447–54. doi:10.1016/j.respe.2013.04.005.

- Tung IL, Machalek DA, Garland SM. Attitudes, knowledge and factors associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake in adolescent girls and young women in Victoria, Australia. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161846. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161846.

- Shetty S, Prabhu S, Shetty V, Shetty AK. Knowledge, attitudes and factors associated with acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among undergraduate medical, dental and nursing students in South India. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1656–65. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1565260.

- Dany M, Chidiac A, Nassar AH. Human papillomavirus vaccination: assessing knowledge, attitudes, and intentions of college female students in Lebanon, a developing country. Vaccine. 2015;33(8):1001–07. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.009.

- Leung JTC, Law CK. Revisiting knowledge, attitudes and practice (KAP) on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among female university students in Hong Kong. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(4):924–30. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1415685.

- Blödt S, Holmberg C, Müller-Nordhorn J, Rieckmann N. Human Papillomavirus awareness, knowledge and vaccine acceptance: a survey among 18-25 year old male and female vocational school students in Berlin, Germany. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(6):808–13. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckr188.

- Fernandes R, Potter BK, Little J. Attitudes of undergraduate university women towards HPV vaccination: a cross-sectional study in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):134. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0622-0.

- Agius PA, Pitts MK, Smith AM, Mitchell A. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: gardasil vaccination status and knowledge amongst a nationally representative sample of Australian secondary school students. Vaccine. 2010;28(27):4416–22. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.038.

- Anfinan NM. Physician’s knowledge and opinions on human papillomavirus vaccination: a cross-sectional study, Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):963. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4756-z.

- Swarnapriya K, Kavitha D, Reddy GM. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding HPV vaccination among medical and para medical in students, India a cross sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(18):8473–77. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.18.8473.

- Wong LP, Raja M, Yusoff RN, Edib Z, Sam IC, Zimet GD. Nationwide survey of knowledge and health beliefs regarding human papillomavirus among HPV-vaccinated female students in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163156. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163156.

- Touch S, Oh JK. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward cervical cancer prevention among women in Kampong Speu Province, Cambodia. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):294. doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4198-8.

- He J, He L. Knowledge of HPV and acceptability of HPV vaccine among women in western China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):130. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0619-8.

- Mengesha A, Messele A, Beletew B. Knowledge and attitude towards cervical cancer among reproductive age group women in Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):209. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8229-4.

- Al-Meer FM, Aseel MT, Al-Khalaf J, Al-Kuwari MG, Ismail MF. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding cervical cancer and screening among women visiting primary health care in Qatar. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(11):855–61. doi:10.26719/2011.17.11.856.

- Navarro-Illana P, Diez-Domingo J, Navarro-Illana E, Tuells J, Alemán S, Puig-Barberá J. Knowledge and attitudes of Spanish adolescent girls towards human papillomavirus infection: where to intervene to improve vaccination coverage. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:490. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-490.

- Villanueva S, Mosteiro-Miguéns DG, Domínguez-Martís EM, López-Ares D, Novío S. Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions towards human papillomavirus vaccination among nursing students in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22). doi:10.3390/ijerph16224507.

- Pelullo CP, Esposito MR, Di Giuseppe G. Human papillomavirus infection and vaccination: knowledge and attitudes among nursing students in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10). doi:10.3390/ijerph16101770.

- Ifediora CO, Azuike EC. Knowledge and attitudes about cervical cancer and its prevention among female secondary school students in Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2018;23(7):714–23. doi:10.1111/tmi.13070.

- Liu A, Ho FK, Chan LK, Ng JY, Li SL, Chan GC, Leung TF, Ip P. Chinese medical students’ knowledge, attitude and practice towards human papillomavirus vaccination and their intention to recommend the vaccine. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(3):302–10. doi:10.1111/jpc.13693.

- Wu CS, Kwong EW, Wong HT, Lo SH, Wong AS. Beliefs and knowledge about vaccination against AH1N1pdm09 infection and uptake factors among Chinese parents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1989–2002. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201989.

- Bowyer HL, Marlow LA, Hibbitts S, Pollock KG, Waller J. Knowledge and awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine among young women in the first routinely vaccinated cohort in England. Vaccine. 2013;31(7):1051–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.038.