?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

To study the sociodemographic factors as well as the interaction between age groups and health conditions in relation to the intention of being vaccinated against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Thailand. A cross-sectional survey was conducted during the “third wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand (March to April 2021). The survey was uploaded and administered via the online survey platform of Google™. Thai citizens aged >18 years completed the survey. All factors that predicted the vaccine intention (VI) among participants were measured and analyzed using logistics regression and cross-tabulation. Among 862 participants, 55.6% said they were likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine. From the finding of the logistic regression, men were more likely to be vaccinated than women. Respondents with more than three health conditions were less likely to get vaccinated compared with those without any health conditions. People at a higher risk of health conditions had the lowest VI in any age group. Among the older age group, the number of health conditions affected the VI. The potential harmful side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine was the main reason for vaccine hesitancy. Overall, ~56% of respondents to an online questionnaire intended to become vaccinated against COVID-19. The older age group with a high risk of health conditions had the lowest VI even though this group should get the vaccine first. Therefore, there is an urgent need to design an education strategy to overcome such vaccine hesitancy.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). COVID-19 has wrought havoc on health and economic systems worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic has had several social impacts: business lockdown, tourism lockdown, and social distancing.Citation1 The lifestyle of people has changed drastically. In particular, the pandemic has negatively affected global economic growth, local economies, and government budgets.Citation2 Hence, public-health authorities must seek ways to stop the spread of COVID-19.

One solution is to develop efficacious vaccines to stop the spread of COVID-19, and to vaccinate the population. The primary objective is to create “herd immunity” so that people can return to their social life and business as soon as possible.Citation3 Governments in many countries have spent ~US$2 billion delivering vaccination.Citation4 The primary goal is to deliver two doses per person within 2021,Citation5 especially for those with health problems and older people (who are at risk of developing severe symptoms if exposed to SARS-CoV-2). Overall, a government must ensure vaccination of around 55–82% of its population to achieve herd Immunity.Citation6

The primary factor for successful vaccination is to make people realize the benefit of vaccination. Recent data from public opinion polls in the USA have shown that approximately 20–27% of the population refuses to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation7 Thus, public acceptance and intention to be vaccinated is a very important issue. Studies looking at the vaccine intention (VI) in epidemics have shown different findings. For example, despite the government’s efforts to have widespread vaccination, the intention of the Australian population in 2009 to be vaccinated against H1N1 influenza was ~50%.Citation8 In Hong Kong, 7% reported being “likely/very likely/certain” to be vaccinated against H1N1.Citation9 In Canada, 69% of respondents to one survey intended to receive the H1N1 vaccine.Citation10 In Beijing (China), only 59.9% intended to be vaccinated against influenza H7N9. Overall, the VI for influenza vaccines ranges from 17% to 67% according to studies in Australia, USA, France, and the UK.Citation11

By December 2020, ~49% of the USA population intended to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, with older people being most keen.Citation12 Approximately 64% of a population in the UK intends to have a COVID-19 vaccine,Citation13 whereas ~65% of a Saudi Arabia population intends to receive a COVID-19.Citation14 In China, ~91% of a population accepts vaccinations.Citation11 The vaccine intention (VI) is dependent upon several factors, such as location, time period, and sociodemographic variables.Citation14–17 Findings from one country or a specific group of people cannot be used as information to promote vaccination for individuals in another country. Understanding the VI factors in a specific context is crucial to increase the chances of vaccination, which is an important issue for consideration.

Studies have shown that most individuals are aware of the risk factors associated with COVID-19 (older age, having certain underlying medical conditions). Thus, they are expected to be the first priority to get a vaccine based on these factors.Citation18 Few studies have focused on specific age groups and medical conditions with regard to vaccination.Citation13 We studied the intention of getting a COVID-19 vaccine in Thailand during the “third wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. Until April 2021, only 1.3% of the total population in Thailand had been vaccinated.Citation19 Findings from this study could suggest whether such a low prevalence of vaccination was due to rejection of vaccination or a problem with ineffective vaccination strategies. Public unwillingness to be vaccinated is a significant threat to health.Citation20 Our study findings could be applied to immunization programs by the WHO to accelerate the development of safe and efficacious vaccines against COVID-19.Citation21

Materials and methods

Development and administration of the survey

After a structured review of the literature, a cross-sectional online survey was designed by a group of researchers. This survey was uploaded and administered via the online survey platform of Google™ (Mountain View, CA, USA). Thai citizens aged >18 years completed the survey during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand (March–April 2021), causing 45,000 cases with more than 300 deaths. The electronic survey was distributed through various methods, including invitations via secure social-media platforms. The study was approved by the Ethical committee and conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration. A consent statement was listed on the first page of the questionnaire and all responses were anonymous. Participants’ responses remained confidential in accordance with the privacy policy of Google.

Survey sample

Assuming the adult Thai population (age >18 years) to be 55,000,000 with a prevalence of vaccine acceptance of 50% and margin of error of 4% (95% confidence interval (CI): 46%–54%),Citation22 we estimated a sample size of 600. Accounting for non-responses, missing values, and dropouts, the final sample size was calculated to be 800. A total of 862 participants returned the survey.

Measurements and data analyses

Information on sociodemographic factors (sex, age, household income, education, marital status, number of family members, and health conditions) was provided by respondents. Following the method of Ruiz and Bell,Citation23 the relationship between preexisting conditions including chronic lung disease, heart condition, diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, kidney disease, liver disease, weak immune system, tobacco smoking and the perceived threat of COVID-19 severity was studies. The primary outcome of our study was the VI against COVID-19 using one question: “How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine?.” The answer was measured on a five-point Likert scale as “1 = extremely unlikely,” “2 = somewhat unlikely,” “3 = unsure,” “4 = somewhat likely,” and “5 = extremely likely” to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Other questions, including “the reason for not getting a vaccine,” and the “type of COVID-19 vaccine,” were also asked. We undertook a literature review before developing a draft questionnaire. All items were translated into Thai by two bilingual Thai researchers. A back-translation process was applied to ensure conceptual equivalence.

Basic descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages) were calculated to provide preliminary analyses of sample characteristics. The relationships between sociodemographic factors and the VI were assessed by the chi-square test and logistic regression analysis to determine significant factors. In addition, we computed the VI variable into dichotomous variables for logistic regression analysis. Following the previous research,Citation23–25 the outcome variable to measure vaccine intention (VI) was divided into two groups. Those likely to get vaccine were defined as respondents who reported “Extremely Likely,” and “Somewhat Likely” to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Respondents who reported “Extremely Unlikely,” “Somewhat Unlikely,” and “Not Sure,” were considered not likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine. In the interpretation of the results, p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

We wished to study the effect of the interaction between an age group and health conditions upon VI. We classified ages into three groups: 18–48 years (“young”), 49–63 years (“middle-aged”), and >64 years (older).Citation26 We classified health conditions into three groups: “no health condition,” “1–2 conditions,” and “≥3 conditions.” Cross-tabulation was carried out to evaluate the interactions in categorical variables.

Results

Preliminary analyses

After the collection of completed questionnaires and statistical analyses, a summary of demographic results was undertaken (). Most of the respondents were women, accounting for 551 (63.9%) out of a total of 862. Most of the 532 respondents were aged 18–44 years (61.7%), 281 were aged 45–64 years (32.6%), and 49 people were aged >65 years (5.7%).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study cohort

Most respondents had a household income of 20,001–50,000 baht (US$650-US$1,650), accounting for 293 respondents out of 862 (34.0%), with 130 earning <20,000 baht (US$650) (15.1%) and 101 earning more >200,000 baht (US$6,500) (11.7%). Most of the respondents had a bachelor’s degree (390, 45.3%). The number of people with a secondary education or lower was 83 (9.6%) and the number of respondents with more than a master’s degree was 70 (8.1%). Most of the 862 respondents, more than half of the sample population likely to be vaccinated to 479 or 55.6% of the total sample population.

Statistical tests were undertaken to ascertain the health determinants related to the VI (). Men were more likely to be vaccinated than women (61.1% vs. 52.5%) with a 5% level of significance. People aged 18–44 years were more likely to get the vaccine than the other age groups. Individuals at no risk of health conditions were most likely to be vaccinated than those in the other two groups. Respondents with a household income >200,000 baht were the most likely to be vaccinated. Preliminary analyses show that besides the difference in sex, other demographic data and health conditions were not significantly related to the VI at 95% CI.

Table 2. Sociodemographic and health determinants of the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19

Sociodemographic profile, health conditions, and the VI

presents the results from the logistic regression analysis for the association between sociodemographic factors (sex, age), health conditions and VI. In general, sex is the only factor that was significantly associated with VI. Women were 0.67-times less likely to accept vaccination than men (OR = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.50–0.90, p < .05). Age and health condition were not significantly associated with VI variables.

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis for sex, age, and health conditions for prediction of intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19

Interaction between age group and health conditions

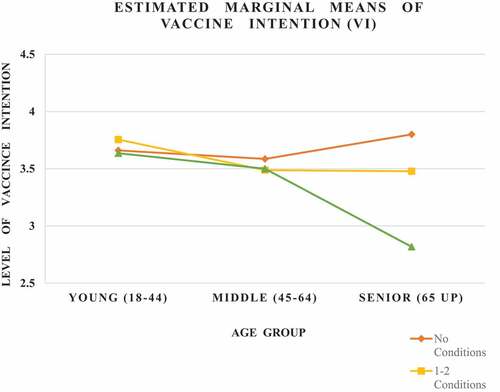

and show the VI (interaction between age and health conditions) in the three age groups together with the three groups of health conditions. With regard to people with no health conditions, the middle-age group (age 45–64) had the lowest VI. The VI tended to decrease for the older age group (age ≥65), especially for those who did have at least one health conditions. That is, people with couple or more than three health conditions in the older-aged group had the lowest VI. When considering only people aged ≥65 years, the group with no health conditions had the highest VI. Conversely, older people with ≥3 health conditions have the lowest VI.

Table 4. Estimated marginal means of vaccine acceptance across health conditions and age groups

Figure 1. Marginal means of COVID-19 vaccine intention (VI) against age groups and health conditions.

Overall, people at any risk of health problems had nearly the same level of VI within their age groups, except the seniors. Among the older age group, the number of health conditions affected the VI. The older age group with a high risk of health problems had the lowest VI.

We ranked the type of vaccine and its manufacturer among the vaccinated group () and the reasons for not being vaccinated in the non-vaccinated group (). shows, from the highest to lowest rankings, the type of vaccine respondents was most likely to be administered (n = 479). We found that 61.8% of the group did not know the vaccine type or manufacturer due to a lack of knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine. We discovered that 15.0% of respondents wished to be given a vaccine based on messenger (m)RNA (e.g., Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna). Also, 10.2% of respondents wished to be administered a vaccine that used the viral protein (Oxford University/AstraZeneca), the dead virus such as Sinovac (8.6%), and the viral proteins such as Novavax at 4.38%, respectively.

Table 5. Rankings of preferences of COVID-19 vaccine type among vaccinated respondents, ranked by frequency of preference given

Table 6. Rankings of reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among non-vaccinated respondents, sorted by age groups

Table 7. Rankings of reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among non-vaccinated respondents, sorted by health condition groups

We ranked the reasons for vaccine hesitancy by age group and health risk (). The top-three reasons for the different age groups and health conditions were “The vaccine can have dangerous side effects”; “I may be allergic to the vaccine”; “The vaccine may not work.” This ranking was in accordance with the top-three reasons given for vaccine hesitancy in the non-vaccinated groups. Among the older age group, other specific reasons included an “Absence of an infection risk” and “The infection by SARS-CoV-2 was not severe.”

Discussion

Use of vaccines to establish herd immunity is a key factor in stopping infections running rampant through populations. Sociodemographic factors, age, and health conditions have been cited as factors involved in the VI.Citation27 Educating people about the benefits and risks of COVID-19 vaccines is very important during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

We undertook a study of the intention of respondents to take the COVID-19 vaccine during the third wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in Thailand, which was more severe than the previous two “waves.” We also studied the interactions between age groups and health conditions to aid further understanding of the factors related to the VI.

Of the 862 respondents, 55.6% intended to get a COVID-19 vaccine and 17.5% refused to have it. About 26.9% remains vaccine hesitant, indicating “Not Sure” to get a COVID-19 vaccinated. These results are consistent with data from other studies. For instance, 46% of South Africans responded positively (‘somewhat agree’ or ‘completely agree’), slightly lower than the global average of 48%,Citation28 whereas 62% of a population in the USA intended to get vaccinated against COVID-19.Citation29 About 65% of a population in Saudi Arabia intended to get a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation14 Hence, acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination ranges from ~50% to ~70% depending on the period of the outbreak and disease severity. However, one study found that only 37% in Middle East countries were prepared to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation30 One reason that may explain the wide range of VI prevalence may be the severity and period of the COVID-19 outbreak, which can affect people differently regarding the perceived risk of COVID-19 and benefit of a vaccine against it. We found that men were more likely to receive a COVID-19 vaccine than women. Women are more likely to be worried about the benefits and side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine than men, which reduces the VI for women. Our study underlines the importance of the context related to the VI. A survey in 2020 evaluating the likelihood of acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine among 13,426 individuals in 19 countries found significant differences.Citation31 Thus, the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19 is dependent upon a specific context and factors such as time, vaccine quality, social norms, and sociodemographic factors. If the study was conducted during the pandemic in a severely affected areas, the proportion of people who intended to get vaccinated was more as risk of infection increased.

We discovered that an older age group with a low risk of health conditions had the highest VI. This finding is in accordance with the medical advice given to older adults, who may be more severely infected with SARS-CoV-2.Citation32–34 However, younger people should be vaccinated before other age groups.Citation35 In accordance with that study, the young age group was more likely to be vaccinated compared with that in other groups ().

The older age group without any health conditions had the highest VI (): the graph shows in a J-shape, rising gradually from the middle age to older age. One explanation is that health conditions are important factors to consider for the interaction effect with age for the VI. Conversely, the older age group with ≥3 health conditions chose not to receive a COVID-19 vaccine because they feared that the vaccine would interact with their existing health conditions. Our results contradict the medical recommendation stating that older people with a high risk of health problems should receive the COVID-19 vaccine before other age groups.Citation13 Hence, governments must educate people of all ages (especially older people with health conditions) regarding the benefits and risks of a COVID-19 vaccine. Those who do not have sufficient knowledge about vaccines focus mostly on the side effects instead of the benefits of a COVID-19 vaccine, especially if the underlying disease is more severe than COVID-19.Citation36

The three main reasons given by respondents for not being vaccinated according to the age group and risk of health conditions were side effects, allergy to vaccines, and that the vaccine would not prevent COVID-19. Our results showed that people who refused steadfastly to be vaccinated were those considered to be aware of the side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine. This observation is consistent with research reporting on the risk perception of vaccination.Citation37 The theory used to explain this phenomenon is the “Theory of reasoned action (TRA).” In this case, the attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination and perceptions of social support for COVID-19 vaccination were determinants of the intention to be vaccinated.Citation38 That is, the VI is increased if data on vaccine safety are available. Issues regarding vaccine safety are essential to interruption of the widespread distribution of vaccines to the public. Especially among older individuals at risk, there is considerable concern about the side effects and safety of COVID-19 vaccines.

A vaccine that contains the partial genetic code (i.e., mRNA) of SARS-CoV-2 may have more side effects compared with vaccines that use inactivated viruses. This type of vaccine seemed to be the first preference of our study cohort. Hence, people who perceive the benefits of a COVID-19 vaccine over the potential side effects may be more likely to get vaccinated. This hypothesis is consistent with research in South Korea and Turkey showing the perceived benefits of an influenza vaccine.Citation39,Citation40

We also categorized respondents into different age groups and health conditions. People of different age groups and with different health conditions showed a different level of VI. Few studies have focused on specific age groups or health conditions in terms of the VI. Hence, our data: (i) complement previous research by studying the factors associated with age and the risk of health conditions in Thailand; (ii) provide an overview of the COVID-19 VI compared with that in other regions worldwide; (iii) are important for government policymakers in Thailand and worldwide.

Our study had three main limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional data, so only the “big picture” at a particular time can be seen. Our finding could be partially attributed to the fact that the study was conducted at the beginning of the third wave in Thailand, before the highest demand on healthcare that far exceeded the fatality that were recorded. Future studies should investigate the intention to have a COVID-19 vaccine over a long-term period and under different conditions. Second, collecting data using an online format instead of face-to-face interviews could result in a bias. Obtaining information through interviews may yield more direct insights and a clearer understanding of the respondents’ intentions. Third, we did not study other factors that could affect the VI, such as the perception of risk and benefit. Risk and benefit perception is important for vaccine decision-making, and could significantly vary from different periods of time, age group or health conditions.

Conclusions

We provided preliminary insights into the intention of being vaccinated against COVID-19 in Thailand. Overall, ~56% of respondents to an online questionnaire intended to become vaccinated against COVID-19. The finding showed that most individuals are aware of the risk factors associated with COVID-19 including age and underlying medical conditions. Specifically, the older age group with health conditions had the lowest VI. Therefore, there is an urgent need to design a strategy to promote vaccination program and overcome such vaccine hesitancy. People at risk of contracting COVID-19 must be educated to alleviate any fears associated with COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and safety.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the conception of the work and gave final approval of the version to which the article has been submitted. S.B. and N.R. designed the study, performed the data analysis, and interpretation of data. S.J. and Y.K. aided in discussing the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the editor and two anonymous reviewers’ comments for their helpful comments and suggestions, which helped us to revise the manuscripts. We also like to thank data collectors and respondent for their support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzueta E, Perrin P, Baker FC, Caffarra S, Ramos‐Usuga D, Yuksel D, Arango‐Lasprilla JC. How the COVID‐19 pandemic has changed our lives: a study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol. 2021 Mar;77(3):556–70. doi:10.1002/jclp.23082.

- Ceylan RF, Ozkan B, Mulazimogullari E. Historical evidence for economic effects of COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:817–23. doi:10.1007/s10198-020-01206-8.

- Velavan TP, Pollard AJ, Kremsner PG. Herd immunity and vaccination of children for COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:14–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.065.

- World Health Organization. Costs of delivering COVID-19 vaccine in 92 AMC countries. 2021. [accessed 2021 May 10]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/costs-of-delivering-covid-19-vaccine-in-92-amc-countries.

- World Health Organization. COVAX global supply forecast. 2021. [accessed 2021 May 10]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covax-global-supply-forecast.

- Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–77. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200282.

- Neergaard L, Fingerhut H. AP-NORC poll: half of Americans would get a COVID- 19 vaccine. AP; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 10]. https://apnews.com/dacdc8bc428dd4df6511bfa259cfec44.

- Seale H, Heywood A, McLaws M, Ward KF, Lowbridge CP, Van D, MacIntyre CR. Why do I need it? I am not at risk! Public perceptions towards the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccine. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10(99):1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-99.

- Liao Q, Cowling BJ, Lam WWT, Fielding R. Factors affecting intention to receive and self-reported receipt of 2009 pandemic (H1N1) vaccine in Hong Kong: a longitudinal study. PloS One. 2011;6(3):e17713. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017713.

- Kaboli F, Astrakianakis G, Li G, Guzman J, Naus M, Donovan T. Influenza vaccination and intention to receive the pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine among healthcare workers of British Columbia, Canada: a cross-sectional study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(10):1017–24. doi:10.1086/655465.

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008961. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961.

- Nguyen KH, Srivastav A, Razzaghi H, Williams W, Lindley MC, Jorgensen C, Abad N, Singleton JA. COVID‐19 vaccination intent, perceptions, and reasons for not vaccinating among groups prioritized for early vaccination—United States, September and December 2021:1650–56. MMWR. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7006e3.

- Sherman SM, Smith LE, Sim J, Amlôt R, Cutts M, Dasch H, Rubin GJ, Sevdalis N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;17:1–10.

- Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1657. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S276771.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- Wilson K, Nguyen HH, Brehaut H. Acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine: a systematic review of surveys of the general public. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:197. doi:10.2147/IDR.S23174.

- Xiao X, Wong RM. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(33):5131–38. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.076.

- Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;1:100012. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.

- Reuters COVID-19 Tracker. Department of disease control, Thailand. 2021. [accessed 2021 May]. https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/countries-and-territories/thailand/.

- World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. 2019. [accessed 2020 Nov]. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Bloom DE, Cadarette D, Ferranna M, Hyer RN, Tortorice DL. How new models of vaccine development for COVID-19 have helped address an epic public health crisis: article describes and analyzes how resources, cooperation, and innovation have contributed to the accelerated development of COVID-19 vaccines. Health Aff. 2021;40(3):410–18. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02012.

- Phulkerd S, Thapsuwan S, Chamratrithirong A, Gray RS. Influence of healthy lifestyle behaviors on life satisfaction in the aging population of Thailand: a national population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10032-9.

- Ruiz JB, Bell RA. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021;39(7):1080–86. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010.

- Walker AN, Zhang T, Peng XQ, Ge -J-J, Gu H, You H. Vaccine acceptance and its influencing factors: an online cross-sectional study among international college students studying in China. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):585. doi:10.3390/vaccines9060585.

- Wheldon CW, Daley EM, Buhi ER, Nyitray AG, Giuliano AR. Health beliefs and attitudes associated with HPV vaccine intention among young gay and bisexual men in the southeastern United States. Vaccines. 2011;29(45):8060–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.045.

- Lin Z, Yang R, Li K, Yi G, Li Z, Guo J, Zhang Z, Junxiang P, Liu Y, Qi S, et al. Establishment of age group classification for risk stratification in glioma patients. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-01888-w.

- Abedin M, Islam MA, Rahman FN, Reza HM, Hossain MZ, Hossain MA, Arefin A, Hossain A. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. Plos One. 2021;16(4):e0250495. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250495.

- Cooper S, van Rooyen H, Wiysonge CS. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: how can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021 Jul;12:1–3.

- Thunstrom L, Ashworth M, Finnoff D, Hesitancy NS. Towards a COVID-19 Vaccine and Prospects for Herd Immunity. SSRN. 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3593098.

- Al-Qerem WA, Jarab AS. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and its associated factors among a Middle Eastern population. Front Public Health. 2021;9:34. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.632914.

- Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(1):99–117. doi:10.1586/14760584.2015.964212.

- Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–28. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Wagner AL, Montgomery JP, Xu W, Boulton ML. Influenza vaccination of adults with and without high-risk health conditions in China. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2017;39:358–65.

- Persad G, Emanuel EJ, Sangenito S, Glickman A, Phillips S, Largent EA. Public perspectives on COVID-19 vaccine prioritization. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e217943–e217943. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.7943.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Joint Committee on vaccination and immunisation: interim advice on priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination. Priority groups for coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination: advice from the JCVI. [accessed 2020 Sep 16]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi/interim-advice-on-priority-groups-for-covid-19-vaccination.

- Wang Y, Ristea A, Amiri M, Dooley D, Gibbons S, Grabowski H, Hargraves L, Kovacevic N, Roman A, Schutt R, et al.Vaccination intentions generate racial disparities in the societal persistence of COVID-19. SSRN. 2021. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3827269.

- Sherman SM, Smith LE, Sim J, Amlôt R, Cutts M, Dasch H, Rubin GJ, Sevdalis N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;17(6):1–10.

- Kwon Y, Cho HY, Lee YK, Bae GR, Lee SG. Relationship between intention of novel influenza A (H1N1) vaccination and vaccination coverage rate. Vaccine. 2010;29(2):161–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.063.

- Gaygısız Ü, Gaygısız E, Özkan T, Lajunen T. Why were Turks unwilling to accept the A/H1N1 influenza-pandemic vaccination? People’s beliefs and perceptions about the swine flu outbreak and vaccine in the later stage of the epidemic. Vaccine. 2010;29(2):329–33. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.030.