ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 vaccines have been developed in a wide range of countries. This study aimed to examine factors that related to vaccination rates and willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 among Chinese healthcare workers (HCWs). From 3rd February to 18th February, 2021, an online cross-sectional survey was conducted among HCWs to investigate factors associated with the acceptance and willingness of COVID-19 vaccination. Sociodemographic characteristics and the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese HCWs were evaluated. A total of 2156 HCWs from 21 provinces in China responded to this survey (effective rate: 98.99%)), among whom 1433 (66.5%) were vaccinated with at least one dose. Higher vaccination rates were associated with older age, working as a clinician, having no personal religion, working in a fever clinic or higher hospital grade, and having received vaccine education, family history for influenza vaccination and strong familiarity with the vaccine. Willingness for vaccination was related to working in midwestern China, considerable knowledge of the vaccine, received vaccine education, and strong confidence in the vaccine. Results of this study can provide evidence for the government to improve vaccine coverage by addressing vaccine hesitancy in the COVID-19 pandemic and future public health emergencies.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19, emerged in late 2019 and has caused a global pandemic. The pandemic has led to more than 90 million cases and 1.9 million deaths worldwide, with disastrous consequences for the world economy and public health.Citation1 It has been suggested that 60–70% of the world population needs to be immune, either through natural infection or vaccination, to achieve herd immunity and finally end the pandemic.Citation2

Vaccination is one of the most effective health interventions to prevent and control the spread of infectious diseases.Citation1,Citation3 Safe and effective vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are necessary to protect populations from COVID-19 and to safeguard global economies from continued disruption.Citation3,Citation4 The first human clinical trial of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (mRNA-1273) commenced on March 2020 in the United States,Citation5 and a 94.1% efficacy of this vaccine has been confirmed.Citation6 However, the global uptake of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine remains insufficient for herd immunity.Citation7,Citation8 To date (June 3 2021), over 681.9 million doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine have been administered in China, which is still under the 60% coverage recommended.Citation9 Meanwhile, some high-risk, low-income countries, such as Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and Guinea, have not even released vaccination data.Citation10 One of the reasons for vaccine hesitancy may be doubt about its effectiveness and safety; a survey in the United States showed that 31% of adults were not willing to get the vaccine due to a fear of side effects,Citation11 and another study in France reported that 26% of adults felt resistance toward receiving the vaccine due to doubts regarding its effectiveness.Citation12 Furthermore, a survey in China indicated the gap between people’s willingness to accept the vaccine and their actual vaccination activity; about 47.8% of participants expressed “willingness” to receive the vaccine, but indicated they would postpone vaccination until the safety of the vaccine was confirmed.Citation13

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at high risk during the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation14,Citation15 The infection risk for this group is 9–11 times higher than that of the general population.Citation16 Once HCWs are infected, the infection risk for patients can consequently increase. Hence, understanding the willingness of HCWs to accept the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and exploring the determinants for vaccination action can help policy makers formulate targeted education and vaccine-promotion policies, which are of great importance in enhancing vaccine uptake and avoiding future outbreaks. Much of the existing literature either focuses on evaluating the explicit reasons for vaccine hesitance and resistance,Citation5,Citation17,Citation18 or investigates the relationship between vaccination intention and sociodemographic factors of the general public by using the health belief theory or planning behavior theory.Citation19–22 There are a number of investigations identifying the psychological processes behind people’s decisions to be vaccinated and distinguishing them from those undergone by individuals who have the intention but will not take action.

The multiple health locus of control (MHLC) scale was developed to investigate a person’s beliefs that the source of reinforcements for their health-related behaviors is primarily internal (determined by their own opinion) or external (determined by a matter of chance, or under the control of powerful persons).Citation23 The scale has been used as one of the most efficient measures for health-related behaviors.Citation24–26 The present study aimed to use this measurement to investigate whether HCWs’ decision to accept the COVID-19 vaccine is controlled by internal or external factors. This study also evaluated factors influencing actual vaccination rate and willingness among HCWs in China. The results can be used to make further recommendations for corresponding vaccination strategies and immunization plans, which are of particular importance in increasing vaccine coverage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Recruitment

The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) age ≥18 years old; and (2) hospital HCWs, including any doctors and nurses who worked full time at public hospitals or local clinics. All respondents gave informed consent and voluntarily participated in the survey. The exclusion criteria were: (1) interns, student nurses, and medical students in school; and (2) individuals who were employed by private hospitals.

2.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained the following three parts: demographics, vaccination-related intentions and behaviors, and the MHLC scales:

Demographic information (13 items): participants’ gender, age, education background, religion, income, living area, field of work, length of employment, clinical occupation, and level of the hospital.

COVID-19 vaccination-related features: vaccination status, willingness to be vaccinated, and vaccine-related knowledge.

The MHLC scale: The scale consists of three parts: the internal health locus of control (IHLC, beliefs that health outcomes are related to one’s own ability and effort, Cronbach α = 0.61–0.80); the powerful other’s health locus of control (PHLC, beliefs that health outcomes are related to powerful others such as physicians, Cronbach α = 0.56–0.75); and the chance health locus of control (CHLC, beliefs that health outcomes are related to chance and fate, Cronbach α = 0.55–0.83).Citation23,Citation26,Citation27 Each part has six items (score range: 6–36), and a higher score represents a higher locus of control.Citation23

2.3. Distribution and data collection

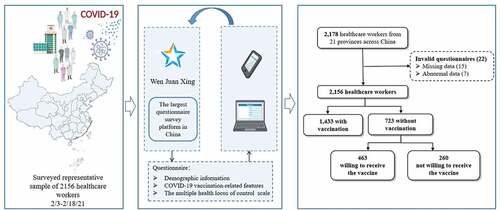

From February 3 to 18, 2021, an anonymous cross-sectional survey was conducted on the largest questionnaire survey platform in China, Wen Juan Xing (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd, China), which can be accessed via a secure webpage from any computer or smartphone with internet access. The survey took approximately 10 mins to complete. We used the snowball sampling method to ensure the effective rate. Information and links to the survey were spread via WeChat and QQ (two of the most popular social media platforms in China), via existing contacts with hospital network members, and via word of mouth. No personal identifiers are collected, so the data generated were anonymous. A pre-survey was conducted by selecting ten health professionals from different hospitals to finalize the questionnaire. Each hospital had one or two research assistants for questionnaire distribution. Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary and their consent to this study was implied by completion of the questionnaire. Details are shown in .

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R Foundation for Statistical Computing (version 4.0.3). Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). Dichotomous data were presented as frequency (%) and compared by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test in two groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine independent risk factors. Multivariate analysis data were represented on a forest plot for all comparative odds ratio (OR) values with a 95% confidence interval (CI). P values equal to or less than .05 were considered statistically significant. The bar plots of some potentially related reasons were presented to analyze differences among groups. Main packages including “forest plot,” “glm,” “ggolot2,” “maps,” “map data,” and “tableone” were applied to visualize and analyze the results and make conclusions.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xiamen Medical College and passed an audit by the China Clinical Trial Registration Center (Registration number: ChiCTR2100042804).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of survey respondents

Between February 3 and February 18, 2021, a total of 2178 HCWs, including 343 doctors and 1814 nurses, were recruited from 21 provinces across China. After 22 invalid questionnaires were removed, 2156 participants were finally enrolled for data analysis (effective rate: 98.99%, valid questionnaires divided by all received questionnaires). A total of 1433 participants were vaccinated (66.5%). Individuals were categorized as vaccinated if they had been vaccinated at least one time at the time of completion of the survey (). The mean age of participants was 32.91 years (SD = 8.29). The sources of vaccine-related information were: work units (84.6%), WeChat (80.1%), network news (79.7%), TV (64.0%), government announcements (62.2%), community/village epidemic prevention pamphlet/bulletin board/campaign (46.4%), SMS (42.3%), other apps (35.5%), informed by others (30.7%), blogs (30.6%), and radio (10.7%).

Table 1. The characteristics of including subjects for vaccines in the survey

3.2. Comparisons in people with different vaccinated status

Compared to HCWs who had not been vaccinated, vaccinated individuals were more likely to report having more years of employment, working in midwestern China, and working in a fever clinic, or a municipal hospital (). Moreover, vaccinated individuals were significantly more familiar with and confident in the COVID-19 vaccines than unvaccinated HCWs. Among unvaccinated HCWs, significant differences were also observed in socio-demographics among those with different levels of willingness to be vaccinated (). For instance, those who expressed a strong willingness to receive the vaccine appeared to have no personal religion, better health status, work in midwestern China, sufficient knowledge about the vaccine, and strong confidence in the vaccine (all tested P < .05).

Table 2. The comparisons in different groups of willingness and receiving of vaccines in population

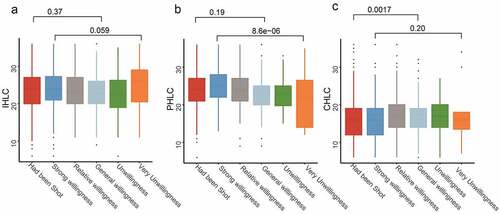

3.3. MHLC psychology results for the participants

To detect whether accepting the vaccine was influenced by internal or external factors, the MHLC scale was adopted. No significant difference was found in IHLC and PHLC between vaccinated and unvaccinated populations. However, the PHLC score positively related to vaccination intention in the study population (), reflecting that subjects’ willingness to accept the vaccine may mainly be influenced by external factors, especially by powerful others, such as endorsements from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in China or recommendations by physicians during the current circumstances.

3.4. Determinants of vaccination action and willingness to receive a vaccination

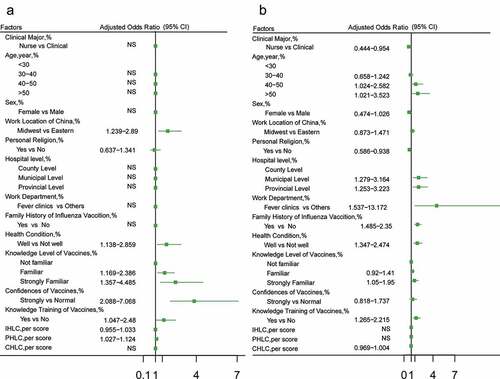

Based on the results of the MHLC, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to explore factors influencing the acceptance of vaccines in HCWs ( and ). The unvaccinated population was divided into two groups: willing (individuals who chose “strong willingness” or “relatively strong willingness” to accept the vaccine) and unwilling groups (individuals who chose “moderate willingness,” “prefer not,” and “not at all” for vaccination).

Figure 3. Factors analysis for willingness to receive the vaccine(a) and the COVID-19 vaccination (b).

As shown in , the vaccination willingness and vaccination rate were both significantly higher if the HCWs had obtained training on vaccines, had strong familiarity with vaccines, and had good health status. In the higher vaccination rate group only (), subjects were older (40–50 years vs. less than 30 years, OR = 1.626, 95%CI = 1.024–2.582) and >50 years vs. 30 years, OR = 1.896, 95%CI = 1.021–3.523) and had histories of influenza vaccination (OR = 1.868, 95%CI = 1.485–2.35), working in fever departments, and working in larger general hospitals rather than county level hospital (municipal vs. county OR = 2.012, 95%CI = 1.279–3.164; provincial vs. county, OR = 2.01, 95%CI = 1.253–3.223). On the contrary, subjects with religious beliefs, and nurse (compared to the physician) had lower vaccination rates. ().

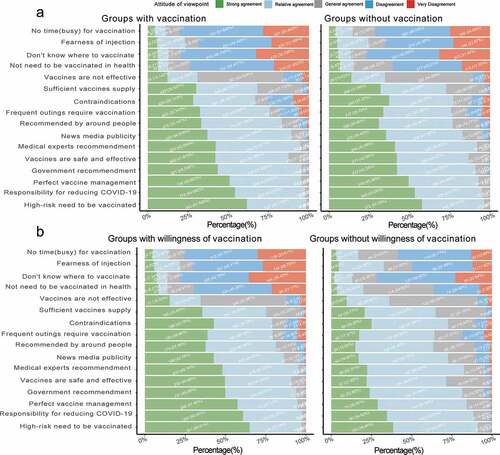

3.5. Subjective opinions on COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs

To better understand the actual concerns of HCWs and to improve their willingness to be vaccinated, subjective reasons related to COVID-19 vaccination were explored in the study population. shows the main reasons why HCWs would accept the vaccine. The top five reasons were: they are part of a high-risk group that needs to be vaccinated; they feel responsibility for reducing COVID-19 cases; they want to support national vaccine management; it is a recommendation by the government; and the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine.

3.6. Adverse effects

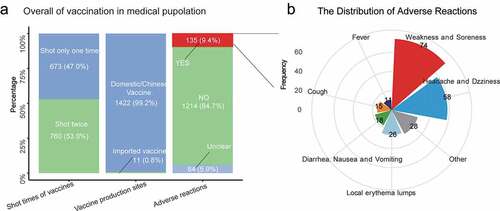

Of the 1433 people that had been vaccinated, 673 (47.0%) had one dose and 760 (53.0%) had two doses; 1422 (99.2%) chose a domestic vaccine and 11 (0.8%) chose an imported vaccine. A total of 135 adverse effects (9.4%) were reported, including weakness (74, 5.2%) and headache/dizziness (58, 4.0%) ().

4. Discussion

This study firstly provides an in-depth analysis of determinants for vaccination acceptance among HCWs from 21 provinces in China. Of the 2156 participants, 66.5% were vaccinated. Findings were consistent with other studies showing that a higher vaccination rate was associated with personal characteristics (male participant, older age, work as a physician, no personal religion, holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, and healthy physical condition);Citation28–30 working environment (more years of clinical work, working in midwestern China, working in a fever clinic);Citation31–33 and more familiarity, vaccine-related training, and belief in the vaccine.Citation34 Of the 723 unvaccinated participants, 10.9% were unwilling or very unwilling to receive the vaccination. Strong willingness to take the vaccine was related to having good health status, considerable knowledge of the vaccine, and strong confidence in the vaccine, which are factors consistent with published literature.Citation22,Citation35–37

Findings show that compared to physicians, nurses were less accepting of the vaccine; this was consistent with the results from US and French surveys among health care workers.Citation38,Citation39 The difference in vaccine acceptance between occupational categories was also reported for seasonal flu vaccines in Israel, where nurses are less often vaccine acceptors than physicians.Citation40 One possible reason for this observed discrepancy can be the preeminence of women in nurses occupational categories, since we also observed that women were less prone to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in the present study and studies in many countries,Citation28–30 presumably due to their caution and desire to wait for the latest vaccine safety report.

Religion has contributed much to health promotion activities by introducing perspectives on the meaning of life and death, which differ from those held by many without religious faith. Our study found that individuals with personal religion were less likely to accept the vaccine than people with no religion. While recent studies among UK and US citizens have not shown the significance of religion as a predictor of vaccine hesitancy,Citation41,Citation42 a national survey in Malaysia reported that Buddhists are twice as likely to hesitate to take the COVID-19 vaccine as Muslims.Citation43 It seems that the impact of religious belief on vaccine acceptance varied among different religions and needed to be interpreted by different socio-demographics. Educational campaigns for the promotion of vaccination may also be needed to reduce the chances of conflict by identifying people with different religious beliefs.

The MHLC results suggest that willingness to receive the vaccine is primarily influenced by powerful others’ actions. Multivariate analyses show that people’s willingness to receive the vaccine was significantly related to their confidence, familiarity, and training on the vaccine, which may be a consequence of the national CDC’s endorsement. A survey in China showed that the public’s willingness to receive vaccination could increase from 62.53% to 85.82% if clinicians recommended it.Citation44 Similarly, an American survey reported a higher probability of accepting the vaccine if it was endorsed by the CDC of America (coefficient 0.09, 95%CI: 0.07–0.11) and by the WHO (coefficient 0.06, 95%CI: 0.04–0.08). These findings highlight the importance of national CDC and healthcare agencies when promoting vaccination and other health activities.

Moreover, the results show that the willingness to be vaccinated was stronger in HCWs from midwestern regions than those from eastern regions. Considering that the vaccines are equally and sufficiently distributed in each province across the country,Citation45 this difference might reflect the comparatively weaker healthcare system in the midwestern regions of China.Citation46 Specifically, people working in the midwest may be more worried about the result if they are infected, and, consequently, are more willing to be vaccinated. While acceptance of the vaccine was associated with worksite location, the imbalanced acceptance rate across the country might be due to the imbalance of medical resources in different regions of China,Citation47 suggesting that efficient delivery of high-quality healthcare to each province is vital for China’s future medical development.

Interestingly, it was found that self-reported willingness to receive the vaccine may not correlate with taking the vaccine. Whilst vaccination willingness did not differ among different age groups, the actual vaccination rate was significantly higher in people aged ≥40 years, which is consistent with the findings in other countries.Citation22,Citation31,Citation48–50 This presumably because the immune function decreases with ageCitation12 and the incidence and mortality of COVID-19 are relatively higher in older adults.Citation12,Citation51,Citation52 Furthermore, evidence showed that young people were less likely to have a strong demand for COVID-19 vaccines compared to the older people.Citation29,Citation53 Hence, the vaccination behavior of younger individuals was observed to be different than that of the elderly. A survey conducted among young people and medical students also found a lack of preventive attitudes when facing the COVID-19 epidemic.Citation32,Citation54 Lazarus et al. reported that people ≥50 were significantly more favorably disposed to vaccination than younger participants in Canada, Poland, France, Germany, Sweden, and the UK, but not in China,Citation55 which contrasts with the results of the present study. This may be because at the time of Lazarus’ analysis, elderly people were not recommended to be vaccinated in China, since the safety of the Chinese vaccine for people >60 years old had not been confirmed at that time. However, the CDC of China currently recommends vaccination for elderly people in light of increasing evidence about its safety and effectiveness.Citation56,Citation57 The safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in elderly people may need further confirmation in larger clinical trials.

We observed that HCWs from fever clinics were more likely to be vaccinated, whilst most HCWs believed that high-risk groups should have priority. Moreover, Nguyen et al. found that the acceptance of the seasonal influenza vaccine was related to the fear of getting infected (66%).Citation58 Given these factors, the mortality rate and infectivity of the virus might be influencing vaccine acceptance. The participants in this study were HCWs who have better knowledge of the SARS-CoV-2 virus than the general public, and, consequently, their vaccination rates and intentions were higher. This shows the importance of raising the public’s awareness of the SARS-CoV-2 virus when promoting vaccination throughout the country. The authorities may also need to start educational campaigns much earlier in future public health emergencies.

As reported by the previous research, the most common reason for vaccination resistance was concern about its side effects.Citation22,Citation35,Citation59 One study showed that the adverse reactions of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine are similar to those of the inactivated non-adjuvanted influenza vaccineCitation60 and the normal and systemic reaction rates for the influenza vaccine are 2.7% and 3.0%, respectively.Citation61 This may help to explain why subjects in this study who reported a self or family history of influenza vaccination were more likely to be vaccinated, since they are more familiar with the potential side effects of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Furthermore, Nguyen et al. showed that non-physicians may be more concerned about the vaccine’s safety than physicians,Citation58 suggesting that the public may be more worried about the vaccine due to their lack of knowledge. Therefore, healthcare agencies need to increase vaccine-related education to the public, particularly in relation to: (1) the development and manufacturing processes for vaccines; (2) the similarities between the seasonal influenza vaccine and the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine; and (3) the efficiency and safety of vaccines based on the latest clinical trials. Moreover, authorities should strive to publish a comprehensive explanation of side effects, which could help to distinguish legitimate safety concerns from events that are temporally associated with but not caused by vaccination. The inappropriate assessment of vaccine safety data can severely undermine acceptance of the vaccine, and, consequently, influence the success of a mass vaccination campaign.Citation33,Citation62

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, at the completion of this survey, China had not recommended the vaccination for people over 60 years old; this introduced participation bias such that vaccination status and associated factors among HCWs over 60 years old could not be analyzed. However, as most HCWs in China retire when they reach 60, the population in this study is likely to represent HCWs who were working at hospitals during the time of data collection. Secondly, we only conducted a cross-sectional multivariate analysis of the survey data, which can only show the correlation between each factor and vaccination willingness and vaccination behavior, but cannot prove its causality; therefore, further longitudinal studies are necessary. Finally, as this study was based on self-reported data, participants’ subjective opinion during the filling out of the questionnaire might introduce self-report bias in data interpretation. Despite these limitations, the large sample size of this study and the representative demographics of Chinese HCWs provide relevant information on the vaccination status of HCWs and a point of reference for the subsequent formulation of vaccination policies.

5. Conclusions

Protecting HCWs against COVID-19 is crucial for maintaining the efficacy of the healthcare system during the pandemic. This study suggests that the characteristics of HCWs, their working environments, and their familiarity with and confidence in the vaccine were related to their self-reported willingness to receive it. The results of this study can not only help to formulate pertinent policies and increase vaccination coverage, but may also be instructive in dealing with future public health emergencies.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, X.Y. and P.S.; methodology, X.Y., W.Y., J.Y. and Z.R.; software, X.Y. and Y.G.; formal analysis, X.Y. and Y.G.; investigation, L.C., A.D., Q.Y., C.Z., Y.L., Y.W., and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y., W.Y. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Y., W.Y., J.Y., Y.G., Z.R., L.C., A.D., Q.Y., C.Z., Y.L., Y.W., S.H. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Medical College and passed the audit of China Clinical Trial Registration Center (Registration number: ChiCTR2100042804).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Koff WC, Schenkelberg T, Williams T, Baric RS, McDermott A, Cameron CM, Cameron MJ, Friemann MB, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, et al. Development and deployment of COVID-19 vaccines for those most vulnerable. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabd1525. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abd1525.

- Bloom BR, Nowak GJ, Orenstein W. “When will we have a vaccine?” - understanding questions and answers about COVID-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2202–04. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2025331.

- Sadoff J, Le Gars M, Shukarev G, Heerwegh D, Truyers C, de Groot AM, Stoop J, Tete S, Van Damme W, Leroux-Roels I, et al. Interim results of a phase 1-2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1824–35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034201.

- Corbett KS, Flynn B, Foulds KE, Francica JR, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Werner AP, Flach B, O’Connell S, Bock KW, Minai M, et al. Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in Nonhuman primates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1544–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024671.

- Murphy J, Vallieres F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, McKay R, Bennett K, Mason L, Gibson-Miller J, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021;12:29. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–16. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27:225–28. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet (London, England). 2021;397:1023–34. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8.

- China has steadily promoted the safety and effectiveness of domestic vaccines for COVID-19 vaccination. 2021.

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. The race to vaccinate the world. Johns Hopkins University; 2021. [Internet]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines/international .

- Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38:6500–07. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043.

- Peretti-Watel P, Seror V, Cortaredona S, Launay O, Raude J, Verger P, Fressard L, Beck F, Legleye S, L’Haridon O. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:769–70. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30426-6.

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8:482. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030482.

- Sim MR. The COVID-19 pandemic: major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77:281–82. doi:10.1136/oemed-2020-106567.

- TheXinhua News Agency. China to inoculate key groups with COVID-19 vaccines. Beijing, China. The State Council Information Office; 2020.

- He Z, Ren L, Yang J, Guo L, Feng L, Ma C, Wang X, Leng Z, Tong X, Zhou W, et al. Seroprevalence and humoral immune durability of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Wuhan, China: a longitudinal, population-level, cross-sectional study. Lancet (London, England). 2021;397:1075–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00238-5.

- Bedford H, Attwell K, Danchin M, Marshall H, Corben P, Leask J. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers: the need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine. 2018;36:6556–58. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.004.

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008961. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961.

- Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:964–73. doi:10.7326/M20-3569.

- Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, Miller CA, Perrin PB, Burton CW, Ryan M, Fuemmeler BF, Carlyle KE. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:137–42. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018.

- Pogue K, Jensen JL, Stancil CK, Ferguson DG, Hughes SJ, Mello EJ, Burgess R, Berges BK, Quaye A, Poole BD, et al. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines. 2020;8:582. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040582.

- Sherman SM, Smith LE, Sim J, Amlôt R, Cutts M, Dasch H, Rubin GJ, Sevdalis N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;17:1–10.

- Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6:160–70. doi:10.1177/109019817800600107.

- Nexoe J, Kragstrup J, Sogaard J. Decision on influenza vaccination among the elderly. A questionnaire study based on the health belief model and the multidimensional locus of control theory. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1999;17:105–10. doi:10.1080/028134399750002737.

- Paek HJ, Shin KA, Park K. Determinants of caregivers’ vaccination intention with respect to child age group: a cross-sectional survey in South Korea. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008342. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008342.

- Wallston KA. The validity of the multidimensional health locus of control scales. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:623–31. doi:10.1177/1359105305055304.

- Levenson H. Multidimensional locus of control in psychiatric patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;41:397–404. doi:10.1037/h0035357.

- Roldan de Jong T Rapid review: perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines in South Africa. 2021.

- Runciman C, Roberts B, Alexander K, Bohler-Muller N, Bekker M. UJ-HSRC COVID-19 democracy survey: willingness to take a COVID-19 vaccine: a research briefing. University of Johannesburg; 2021.[Internet]. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.uj.ac.za/newandevents/PublishingImages/Pages/UJ-HSRC-survey-shows-that-two-thirds-of-adults-are-willing-to-take-the-COVID-19-vaccine/2021-01-25%20Vaccine%20briefing%20(final).pdf

- Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, McKay R, Bennett K, Mason L, Gibson-Miller J, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–15.

- Ruiz JB, Bell RA. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021;39:1080–86. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010.

- Montagni I, Roussel N, Thiébaut R, Tzourio C. Health care students’ knowledge of and attitudes, beliefs, and practices toward the French COVID-19 app: cross-sectional questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e26399. doi:10.2196/26399.

- Seale H, Kaur R, Wang Q, Yang P, Zhang Y, Wang X, Li X, Zhang H, Zhang Z, MacIntyre CR, et al. Acceptance of a vaccine against pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus amongst healthcare workers in Beijing, China. Vaccine. 2011;29:1605–10. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.077.

- Cooper S, Van Rooyen H, Wiysonge CJ. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: a complex social phenomenon. SAMJ. 2021;111:702–3.

- Alqudeimat Y, Alenezi D, AlHajri B, Alfouzan H, Almokhaizeem Z, Altamimi S, Almansouri W, Alzalzalah S, Ziyab AH. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30:262–71. doi:10.1159/000514636.

- Kwok KO, Li KK, Wei WI, Tang A, Wong SYS, Lee SS. Editor’s choice: influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;114:103854. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854.

- Wang K, Wong ELY, Ho KF, Cheung AWL, Chan EYY, Yeoh EK, Wong SYS. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020;38:7049–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.021.

- Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, Tardy B, Rozaire O, Frappe P, Botelho-Nevers E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross-sectional survey. J Hosp Infect. 2021;108:168–73.

- Shekhar R, Sheikh AB, Upadhyay S, Singh M, Kottewar S, Mir H, Barrett E, Pal S. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines. 2021;9:119.

- Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:775–9.

- Robertson E, Reeve KS, Niedzwiedz CL, Moore J, Blake M, Green M, Katikireddi SV, Benzeval MJ. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;94:41–50.

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46:270–77.

- Alwi SS, Rafidah E, Zurraini A, Juslina O, Brohi I, Lukas SJ. A survey on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and concern among Malaysians. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–12.

- Jiang M, Feng L, Wang W, Gong Y, Ming WK, Hayat K, Li P, Gillani AH, Yao X, Fang Y., et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards influenza among Chinese adults during the epidemic of COVID-19: a cross-sectional online survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;17:1–8.

- Wang L, Su XG, Cui Y, Yin WD, He B. Survey on influenza vaccination and cognition of the whole population in 6 provinces in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2020;41:349–353.

- Li X, Lu J, Hu S, Cheng KK, De Maeseneer J, Meng Q, Mossialos E, Xu DR, Yip W, Zhang H, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390:2584–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4.

- Liu H, Liu YX. Construction of a medical resource sharing mechanism based on blockchain technology: evidence from the medical resource imbalance of China. Healthcare-Basel. 2021;9:52.

- Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Health. 2020;13:1657–63. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S276771.

- Gerussi V, Peghin M, Palese A, Bressan V, Visintini E, Bontempo G, Graziano E, De Martino M, Isola M, Tascini C, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among Italian patients recovered from COVID-19 infection towards influenza and Sars-Cov-2 vaccination. Vaccines. 2021;9:172. doi:10.3390/vaccines9020172.

- Seale H, Heywood AE, Leask J, Sheel M, Durrheim DN, Bolsewicz K, Kaur R. Examining Australian public perceptions and behaviors towards a future COVID-19 vaccine. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:120. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-05833-1.

- Dhama K, Patel SK, Natesan S, Vora KS, Iqbal Yatoo M, Tiwari R, Saxena SK, Singh KP, Singh R, Malik YS, et al. COVID-19 in the elderly people and advances in vaccination approaches. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:2938–43. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1842683.

- Levin AT, Hanage WP, Owusu-Boaitey N, Cochran KB, Walsh SP, Meyerowitz-Katz G. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:1123–38. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00698-1.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2020;27:225–28.

- Van Nhu H, Tuyet-Hanh TT, Van NTA, Linh TNQ, Tien TQ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Vietnamese as key factors in controlling COVID-19. J Community Health. 2020;45:1263–69. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00919-4.

- Lazarus JV, Wyka K, Rauh L, Rabin K, Ratzan S, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, El-Mohandes A. Hesitant or not? The association of age, gender, and education with potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: a country-level analysis. J Health Commun. 2020;25:799–807. doi:10.1080/10810730.2020.1868630.

- Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, Flaxman AL, Folegatti PM, Owens DR, Voysey M, Aley PK, Angus B, Babbage G, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2021;396:1979–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32466-1.

- Xia S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Yang Y, Gao GF, Tan W, Wu G, Xu M, Lou Z, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:39–51. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30831-8.

- Nguyen TTM, Lafond KE, Nguyen TX, Tran PD, Nguyen HM, Ha VTC, Do TT, Ha NT, Seward JF, McFarland JW, et al. Acceptability of seasonal influenza vaccines among health care workers in Vietnam in 2017. Vaccine. 2020;38:2045–50. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.047.

- Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Garibaldi BT, Zhang B, Kriner DL. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination (vol 3, e2025594, 2020). Jama Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025594. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594.

- Zheng Y, Chen L, Zou J, Zhu ZG, Zhu L, Wan J, Hu Q. The safety of influenza vaccine in clinically cured leprosy patients in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:671–77. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1390638.

- Huang LR, Li RC, Li YP, Su RP, Huang XC, Huang YN, Deng ML, Li CG, Ju CJ. Study on the safety and immunogenicity of domestic influenza virus split vaccine. The Fifth National Symposium on Immunodiagnosis and Vaccines; 2011; Yinchuan (Ningxia). p. 4.

- Black S, Eskola J, Siegrist CA. Importance of background rates of disease in assessment of vaccine safety during mass immunisation with pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccines (vol 374, pg 2115, 2009). Lancet (London, England). 2010;375:376.