ABSTRACT

The factors that lead to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine hesitancy among health-care workers (HCWs) are unclear. We aimed to identify the factors that influence HCWs’ hesitancy, especially the influence of their social network. Using an online platform, we surveyed HCWs in Chongqing, China, in January 2021 to understand the factors that influence the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs. Proportional allocation stratified sampling method was used to recruit respondents. Multivariable logistic regression and social network analysis (SNA) were used to analyze the influence factors. A total of 5247 HCWs were included and 23.3% of them were vaccine-hesitant. Participants were more hesitant if they had chronic diseases (OR = 1.411, 95% CI: 1.146–1.738), worked in tertiary hospitals (OR = 1.546, 95% CI: 1.231–1.942), and reported a history of vaccine hesitancy (OR = 1.637, 95% CI: 1.395–1.920) and refusal toward other vaccines (OR = 2.433, 95% CI: 2.067–2.863). The participants with a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization were less hesitant (OR = 0.850, 95% CI: 0.728–0.993). Several influential members with social networks were found in SNA. Most of these influential members in the networks were department leaders who were willing to get COVID-19 vaccines (P < .05). Hesitant subgroups among Chinese HCWs were linked to the lack of a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization. Our findings may lead to tailored interventions to enhance COVID-19 vaccine uptake among HCWs by targeting key members in social network.

Background

The number of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases was still increasing in December 2020 in China despite China’s strict pandemic measures.Citation1Vaccine, which provides immunity at individual and population-level,Citation2 promises hope to bring COVID-19 pandemic under control.Citation3 It has become a critical tool in the battle against COVID-19.Citation4 On the last day of December, 2020, an inactivated virus vaccine obtained conditional marketing authorization from the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) of China.Citation5 However, to successfully guard the population against COVID-19 does not only depend on the efficacy and availability of vaccines but also the vaccine acceptance level among the population.Citation6 With more and more vaccines being approved and becoming readily available, the World Health Organization (WHO) expresses concerns on vaccine hesitancy which presents the next biggest challenge in the fight against the pandemic.Citation7 Whether or not to get the COVID-19 vaccine has become a tough decision faced by the public.

As the most trusted source of vaccine-related information for the public, health-care workers (HCWs) have a strong influence on vaccination decisions.Citation8 If HCWs recommend vaccines less frequently to their patients, it would undermine the confidence and lead to vaccine hesitancy among the general population.Citation6,Citation9–11 However, HCWs are losing confidence in vaccination for themselves as well as for their children and patients.Citation9,Citation12–14 Hesitancy against new vaccines is of particular concern.Citation15 The decreasing influenza vaccination rate among HCWs has become an international health issue,Citation16 and the COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs may also be a thorny issue. Mathematical models estimated that if the COVID-19 vaccine is 80% effective, its coverage in the population must be at least 55–82% in order to slow the transmission and decreasing the risk of infection.Citation17,Citation18 Before COVID-19 vaccines were available, several studies showed that the willingness of HCWs to receive COVID-19 vaccines varied from 27.7% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 78.1% in Israel.Citation19,Citation20 In China’s indigenous studies, the willingness rate among HCWs also ranged from 22.2% to 79.1%.Citation6,Citation21–28 Although HCWs are more willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19 compared to the general population, such a vaccine acceptance level is still insufficient to protect HCWs against COVID-19 and ensure the smooth running of the health-care system.Citation6 Vaccine hesitancy is defined as “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services” by the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) Working Group.Citation29 In China, COVID-19 vaccination is strongly encouraged but not mandatory.Citation30 Multiple survey studies showed that the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the general population changed over time in many countries.Citation18 In light of this, examining the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines among HCWs after the vaccine receives conditional marketing authorization has broader policy implications in mass vaccination campaigns.

In the first several months after the issuance of vaccine emergency use authorization (EUAs) by NMPA of China, surveys among HCWs in China showed that the actual acceptance rate ranged from 66.5% to 86.2%, the rates of vaccine hesitancy ranged from 13.8% to 43.5%, and the willingness to vaccinate varied considerably among different regions.Citation31–39 However, those surveys did not study the important role of the social factors that may influence the hesitancy. Considering that the attitude toward vaccine is not only influenced by the characteristics of each individual but also by the people around them, we introduce social network analysis (SNA) to measure the influence of social relations on vaccine hesitancy in addition to the classical multivariate analysis in order to understand the factors that lead to the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines among HCWs. SNA, which offers a way of exposing and mapping the communication and information flow among people from important groups within an organization, has been commonly used to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of decision-making processes in organizations.Citation40 This study could potentially establish a framework to understand vaccine hesitancy among HCWs in China and provide strategies to improve COVID-19 vaccination rate for a better pandemic control.

Methods

Study design

From January 14 to 20, 2021, a cross-sectional self-administered online survey was conducted among HCWs at all hospitals in Yuzhong district, Yubei district and Shapingba district of Chongqing municipal, China. Hospitals in China are designated as primary, secondary and tertiary institutions. Primary hospitals are typically a township hospital that contains fewer than 100 beds. Secondary hospitals contain more than 100 beds, but fewer than 500. Tertiary hospitals round up the list as general hospitals at the city with a bed capacity exceeding 500. These three districts include the majority of tertiary hospitals in Chongqing, hence the social network information of HCWs from hospitals of all three care levels can be collected in the three districts.

Based on the results from our pilot study and to ensure a maximum sample size, the rate of hesitancy (p) was estimated at 20%, and the required sample size of this cross-sectional survey in each of the three districts was calculated as 1600. This experiment design allowed us to investigate the actual vaccine hesitancy (the main outcome of interest) with an allowable error of 0.1p and a cutoff corresponding to 0.05 significance level. Assuming no more than 10% loss to follow-up in each district, the required total sample size was calculated as 5280.

Proportional allocation stratified sampling method was used, and the sample size required from each hospital was determined by the number of HCWs registered at the Department of Health Administration in these districts. Quick Response (QR) code of the questionnaire was distributed in their work groups. The participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained on the survey platform before the participant was allowed to proceed to survey items. If the HCWs agreed to participate, he/she would scan the QR code to complete an Internet-based questionnaire on a platform called Wenjuanxing with functions equivalent to Amazon Mechanical Turk. If the respondents refused, the manager would find another HCW in their work group.

The data of 5247 HCWs who completed the questionnaire were recorded in our study, while the other uncompleted questionnaires cannot be recorded by the platform. All the records were anonymous and without any personal identifiers.

Survey

The questionnaire was presented in Chinese. According to the literature on the vaccine acceptance and social networks in China and United States,Citation13–16 the contents of our questionnaire included items on demographic information (gender, age, levels of hospital care, the last 6 digits of phone numbers to construct the vaccination consulting network, occupation, health related characteristics, and medical behaviors) (), the attitude, experiences and behaviors toward vaccination, the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines, self-perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and the experience of treating COVID-19 patients (). Medical behaviors included the number of patients directly contacted per day by the HCW and whether the survey takers had recommended influenza or COVID-19 vaccines to their patients. If the survey takers mentioned they had at least one friend to discuss COVID-19 vaccination, they were grouped into the class with a vaccination consulting network. Attitude toward vaccination was measured by self-perceived importance of vaccination, the confidence in general vaccine safety and effectiveness, the trust in vaccination information provided by the government and vaccination doctors, and the history of vaccine hesitancy and refusal toward other vaccines not due to valid medical reasons such as preexisting conditions or allergies. Except for the questions on vaccination hesitancy and refusal, which were answered in yes or no, the answers to all other questions were selected from one out of four categories with 1 being the most and 4 being the least. During analysis, the first two categories (1 and 2) were grouped into one class, and the rest two were grouped into another. Behaviors toward vaccination were assessed based on the immunization record of the influenza vaccine and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV 23) in prior years. Each variable was explained in detail, and the jump and logic controls were set up in the questionnaire to reduce the measurement bias. The questionnaire consisted of 16 items regarding attitude toward vaccination. The reliability of this questionnaire was assessed with Cronbach’ α coefficient, and the total Cronbach’ α coefficient was 0.723. In addition to the good content-related validity recognized by the experts, the validity of the questionnaire was also evaluated by factor analysis. The KMO coefficient was 0.855, and the significance of Bartley spherical test was <0.01. The exploratory factor analysis extracted 16 common factors to explain the cumulative variance contribution rate of 52.2%. Based on these analyses, it is concluded that the questionnaire has good reliability and validity.

Table 1. Demographic and health-related characteristics of participants (n = 5247). Demographic and health-related characteristics of participants are shown. Many variables are significantly different in hospitals of different care levels, especially the proportion of participants with a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization

Table 2. Chi-square tests of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for categorical variables (n = 5247). Chi-square tests of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for categorical variables are shown. Several variables are correlated with the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines in chi-square tests (P < .05). All variables with P < .20 in chi-square tests are input into an initial logistic multivariable regression model

In order to conduct the SNA on vaccine hesitancy, the questionnaire also collected the last six digits of the mobile phone numbers of the participants’ friends with whom they were willing to discuss COVID-19 vaccination. According to the 11-digit coding rule of China’s mobile phone number, the first three digits represent the operator, the middle four represent the region, and the last four represent a personal code. Therefore, individuals with the same last six digits in the mobile phone number were considered the same person. With the help of these individuals, a social network to communicate COVID-19 vaccination was established among the respondents, and this social network was named vaccination consulting network.

Data analysis

In this study, the percentage of HCWs who had vaccine hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines was first estimated. The influencing factors, particularly social relations factors that could predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, were identified. A comparative analysis was conducted to examine how the social network could minimize the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines.

Descriptive statistics (e.g. frequencies) were calculated for all variables first. Then, chi-square tests were used to examine the difference between participants from hospitals of different care levels and investigate the association between these variables and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. All variables with P < .20 in chi-square tests were input into an initial logistic multivariable regression model followed by a backward selection procedure that retained variables with P < .05 to create a final multivariable model. The regression model produced odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Lastly, the factors that would influence participants’ decision on receiving COVID-19 vaccines were determined. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), and all statistical tests were two-tailed. A further analysis by stratification was used to examine the relationship between the lack of social network and vaccine hesitancy among HCWs from hospitals of different care levels.

In SNA, the vaccination consulting network of all participants was drawn first. The vaccination consulting network was plotted by connecting individuals who communicated information on COVID-19 vaccination. Each respondent and his/her friends with whom they discuss COVID-19 vaccination formed a sub-network. With the help of the unique individuals identified by their cell phone numbers, several sub-networks were linked together, which established the vaccination consulting network. In the network, individuals with more connecting ties had greater opportunities to influence others, and the extent of influence was measured by the degree. After calculating the degree of members in the network, influential individuals, ranked by their degree in the network, were identified. By further analyzing the vaccination willingness and social characteristics within the network, we attempted to propose a way of decreasing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The SNA was analyzed by UCINET version 6 (Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G. and Freeman, L.C. 2002. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies).

Results

Participants’ characteristics and attitudes toward vaccines

5247 HCWs were included in our study. The mean time of survey completion was about 14.6 min, the 25% quartile of the completion time was 8.6 min, the 75% quartile was 15.3 min, and the median was 11 min. Most respondents were female (85.1%), from tertiary hospitals (55.5%), had a bachelor’s degree (61.1%), and worked as a nurse (54.7%) and as the ordinary staff (89.3%) at the adult departments (52.2%). The age distribution of the participants included 13.1% aged between 18–25, 29.2% aged between 26–30, 59.3% aged between 31–40, 11.2% aged between 41–50, 4.8% aged between 51–59, and 0.2% aged 60 and above. 31.9% of the participants did not live with any child or the elderly.

About 13.8% of the participants indicated chronic diseases, and only 23.7% of the participants bought commercial insurance. 95.9% of participants wore masks all the time and 73.7% washed hands on regular basis in compliance with government’s COVID-19 guidelines. 46.5% of the participants had a history of vaccine hesitancy and 27.3% refused to receive vaccines in the past. 41.3% of the participants took influenza vaccine before, and 31.6% had a vaccination consulting network. Only 16.0% treated adverse events following immunizations (AEFI) before. While 49.4% of the participants directly interacted with 30–99 patients per day, 33.2% had never recommended influenza nor COVID-19 vaccines to their patients. Many variables were significantly different in hospitals of different care levels (P < .05), including the proportion of participants with a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization ().

Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

The vaccination rate was estimated at 43.8% (2300/5247) among HCWs within one month after the vaccine approval. 76.7% (4025/5247) of the participants were classified as willing to receive COVID-19 vaccines, which included the ones who had already been vaccinated and the ones who had been scheduled or were preparing for vaccination soon (32.9%). 23.3% (1222/5247) were classified as vaccine-hesitant (18.3% were uncertain, and 5.0% were certainly unwilling). If children were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination in the future, 65.8% (3451/5247) were willing to get their current children or future children vaccinated, 30.2% (1584/5247) were uncertain, and 4.0% (212/5247) were certainly unwilling.

Several variables were correlated with the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines in chi-square tests (). In multivariable analyses (), participants were more hesitant toward COVID-19 vaccines if they were pharmacist (OR = 2.005, 95% CI: 1.299–3.097), aged 26–30 (OR = 1.355, 95% CI: 1.059–1.735) or 31–40 (OR = 1.517, 95% CI: 1.157–1.990), had a chronic disease (OR = 1.411, 95% CI: 1.146–1.738), and worked in secondary hospitals (OR = 1.467, 95% CI: 1.159–1.858) or tertiary hospitals (OR = 1.546, 95% CI: 1.231–1.942), especially at adult departments of these hospitals (OR = 1.276, 95% CI: 1.085–1.501). Participants were also more hesitant toward COVID-19 vaccines if they reported a personal history of vaccine hesitancy (OR = 1.637, 95% CI: 1.395–1.920) or refusal (OR = 2.433, 95% CI: 2.067–2.863), and did not receive the influenza vaccine in prior years (OR = 1.957, 95% CI: 1.673–2.290). Participants were less hesitant toward COVID-19 vaccines if they lived with children only (OR = 0.624, 95% CI: 0.514–0.757) or with both children and the elderly (OR = 0.574, 95% CI: 0.466–0.706), recognized the importance of vaccines to health (OR = 0.328, 95% CI: 0.113–0.948), had treated patients with COVID-19 before (OR = 0.409, 95% CI: 0.267–0.625), paid attention to the relevant information of COVID-19 actively (OR = 0.665, 95% CI: 0.560–0.791), perceived a higher risk of COVID-19 (OR = 0.646, 95% CI: 0.553–0.755), and had access to the vaccination consulting network (OR = 0.850, 95% CI: 0.728–0.993). A further analysis by stratification revealed that the lack of the vaccination consulting network had an important influence on the vaccine hesitancy among HCWs from secondary hospitals ().

Table 3. Multivariable correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Multivariable correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy are shown. Participants are more hesitant if they have chronic diseases, work in tertiary hospitals, and report a history of vaccine hesitancy and refusal toward other vaccines. The participants with a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization are less hesitant

Table 4. Multivariable correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs in different hospital levels. Multivariable correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs in different hospital levels are shown, and the lack of the vaccination consulting network have an important influence on the vaccine hesitancy among HCWs from secondary hospitals

Factors that influence vaccination decisions

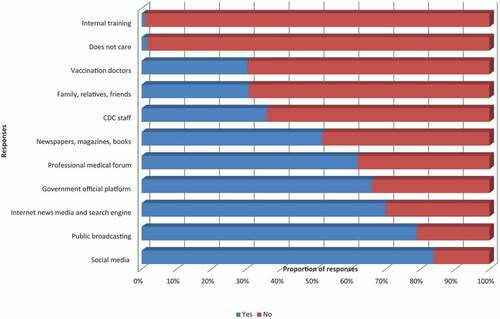

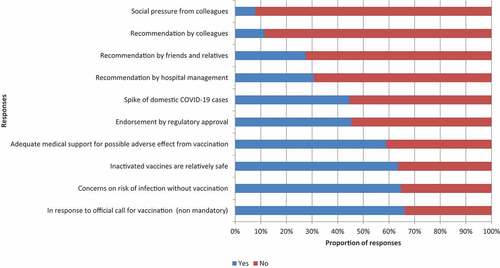

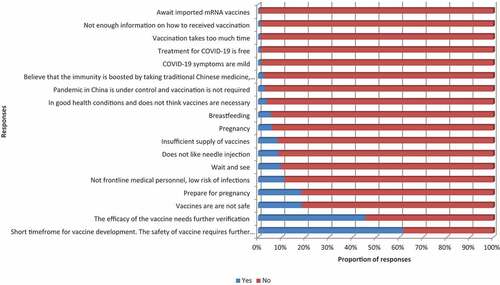

All the participants answered the question regarding their source of relevant COVID-19 information. As shown in , social media was the most common channel of acquiring information on COVID-19 (83.8%), and other channels, such as Center for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) staffs (35.9%) or family/relatives/friends (30.8%), also accounted for a significant proportion. 32.9% of the participants who were willing to get COVID-19 vaccines indicated that several factors shown in would influence their vaccination decisions. The most important factor was the official call for vaccination (non-mandatory) (66.1%). The recommendations by hospital management (30.7%), by friends and relatives (27.5%), or by colleagues (11.4%) also accounted for a significant proportion. 7.8% chose to vaccinate under the pressure from colleagues. 23.3% of the participants who were hesitant about COVID-19 vaccines indicated that several factors shown in would influence their vaccination decisions. Their biggest concerns were the safety (61.5%) and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines (45.5%).

Figure 1. Ways of acquiring relevant knowledge of COVID-19 vaccines ranked from the least to the most popular. 11 ways ranked by the proportion of responses are shown, and the social media is the most popular one.

Figure 2. Factors that would promote participants’ willingness to take COVID-19 vaccination ranked by the proportion of responses. 10 factors ranked by the proportion of responses are shown, and the most important factor is in response to the official call for vaccination (non-mandatory). The missing words are shown in the answers to Question 44 in the questionnaire in the Supplementary S1.

Figure 3. Factors that would matter in participants’ vaccine hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination ranked by the proportion of responses. 18 factors are shown, and participants’ biggest concern is the safety of vaccine. The missing words are shown in the answer to Question 45 in the questionnaire in the Supplementary S1.

SNA

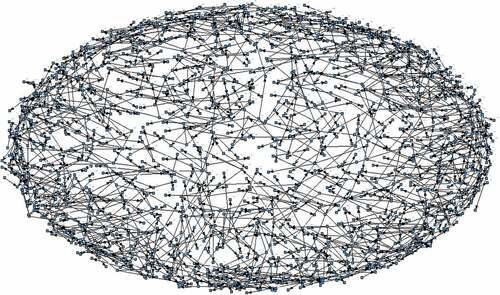

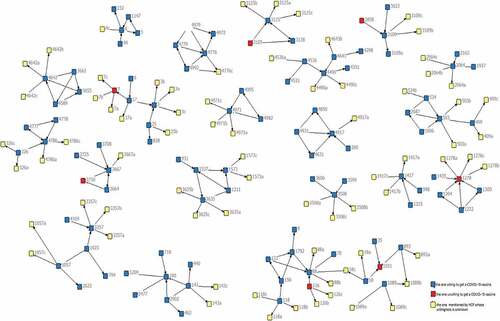

1657 HCWs mentioned they have a vaccination consulting network, with a total of 4213 friends with whom they were willing to discuss COVID-19 vaccination. After screening out duplicated individuals through phone numbers and deleting isolated individuals with no social connections with others, a vaccination consulting network with 1817 members is constructed (). Although this network is loose with a centrality of 0.3%, many sub-networks are linked together, and the vaccination information is transmitted between these sub-networks through influential members in the network.

Figure 4. The vaccination consulting network of the respondents. 1657 HCWs mention they have the vaccination consulting network, with a total of 4213 friends with whom they are willing to discuss COVID-19 vaccination. After screening for duplicated individuals through the phone numbers and deleting isolated individuals with no social connections with others, the vaccination consulting network with 1817 members is constructed.

The degree of these members in the network, which indicates their power of influence, ranged from 0 to 7 with a mean degree of 1.68. Twenty-two most influential members of the network with degrees greater than 5 were identified, and their sub-networks are shown in . The blue nodes in represent the individuals who were willing to get COVID-19 vaccines, the red nodes represent the individuals who were hesitant, and the yellow nodes represent the individuals who were mentioned by the participants but did not participate in this study. In general, most of the individuals in were willing to get COVID-19 vaccines. The social characteristics of these 22 individuals were further analyzed by Fisher’s definite probability methods. Most of them were department leaders (40.9%), with a bachelor’s degree (54.6%), and more likely to get COVID-19 vaccines for themselves (95.5%). These individuals showed social characteristics that were statistically different from the entire group of participants (P < .05) ().

Table 5. Correlation between the 22 influential members ranked by degree in the vaccination consulting network and the entire participants. The social characteristics of the influential members found in SNA which are statistically different from the entire participants are shown, and most of them are department leaders, with a bachelor’s degree, and more likely to get COVID-19 vaccines for themselves

Figure 5. The vaccination consulting network of 22 participants ranks by degree. Twenty-two most influential members in the network with degrees greater than 5 are identified, and their sub-networks are shown. The blue nodes represent the individuals who are willing to get COVID-19 vaccines, the red nodes represent the individuals who are hesitant, and the yellow nodes represent the individuals who are mentioned by the participants but do not participate in this study.

Discussion

Based on our findings, the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rate among HCWs in China is estimated. Different from many other studies among HCWs, our investigation explores the influence of social network on vaccine hesitancy.Citation6,Citation21–28,Citation31–39 Compared to people in western countries who are independent selves and self-centered in their self-structure, oriental selves rely on interdependent social relations. Their self-structure consists of a series of intimate people, and their attitudes and views are more prone to the influence by the relationship.Citation41 Therefore, it is sensible and meaningful to investigate the influence of social network on vaccine hesitancy in China. Although the vaccine hesitancy will change with time, the positive role of social network in the initial stage when a new vaccine first becomes available can be used to guide future mass vaccine campaigns in China.

Vaccine hesitancy is undermining the protection of vaccine-preventable diseases in many specific subgroups across the globe. Targeting specific groups, such as HCWs, has resulted in the largest observed increase (>25%) in vaccine uptake,Citation42,Citation43 and is believed to be an effective way of promoting vaccination. In this study, we surveyed the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs within the first month after the inactivated COVID-19 vaccine was approved, and found that 23.3% of HCWs in Chongqing, China, showed hesitancy toward vaccination for themselves and 34.2% showed hesitancy toward vaccination for their children if the kids would be eligible for COVID-19 vaccines in the future. As studies suggest, an immunity rate of 55–82% among the entire population is required for COVID-19 vaccine to guard the population against the virus.Citation17 Given that a substantial proportion of the population are ineligible for COVID-19 vaccination due to age, immunological status or other preexisting medical conditions, a higher immunity rate is entailed among the eligible population.Citation44 In consideration of the exemplary role of HCWs, actions should be taken immediately to reduce the vaccine hesitancy among HCWs.

It is believed that the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic is a determining factor of vaccine uptake.Citation45 But contrary to the expectation, this study finds that the fear of the disease alone is not enough to promote the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines. Similar to previous studies in Malta,Citation10 our results also show that the likelihood of refusing the COVID-19 vaccine is associated with the likelihood of refusing the influenza vaccine, which indicates the hesitancy toward both vaccines. As such, addressing vaccine hesitancy is not a simple task as a multitude of factors can potentially influence people’s decision on whether to accept vaccination for themselves or their children.Citation20,Citation46

The hesitant subgroups may be linked by geography, culture, socioeconomic and/or other factors.Citation47 For example, hesitant subgroups are defined by their behavioral factors and determinants categorized by complacency, confidence and/or convenience in the European Region,Citation20,Citation31 whereas the decrease in public confidence in vaccines and the vaccine delivery system leads to increased vaccine hesitancy and refusal in the USA.Citation48 In this study, hesitant subgroups among HCWs in China are linked to the age, health status, care level of hospitals, working area, living arrangement, history of vaccine hesitancy and vaccination refusal, perceived risk of infection, and the lack of a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization. The two biggest concerns of the hesitant participants are the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines.

It is encouraging to find a high degree of trust in the government in spite of the vaccine scandals in China in recent years. It is also gratifying to see a lower hesitancy rate among those participants who live with children only or with both children and the elderly, as the two age groups have a high burden of COVID-19.Citation10 However, younger HCWs are less likely to receive COVID-19 vaccines, possibly because they consider their symptoms could be mild or they are preparing for pregnancy or breastfeeding. In addition, the younger group is more likely to be influenced by the hesitant information,Citation49 which agrees with the prior studies on the acceptance of influenza vaccines.Citation10,Citation49 The vaccine hesitancy among HCWs with chronic diseases is of greater concern because of the higher mortality rate of COVID-19 in this group.Citation50,Citation51 What is more worrying is the lower influenza vaccination rate and the lower number of vaccination recommendations made by HCWs with longer experience and more direct contact with patients, especially those HCWs in tertiary hospitals. The recommendation made by HCWs is a key determinant of vaccination behaviors,Citation51 and HCWs in tertiary hospitals are exemplars in terms of healthcare behaviors as they are the most approached and trusted sources of information in many countries.Citation51,Citation52 This finding confirms the previous research results which showed that only a limited number of healthcare providers would recommend and administer vaccines to patients.Citation53 In general, it is imperative to address the vaccine hesitancy among HCWs, especially the youths and the ones with chronic diseases in tertiary hospitals.

Given the complexity of vaccine hesitancy and the limited evidence available on how to address this issue,Citation48 it is exciting to see the importance of the participants’ social network on vaccine hesitancy in our survey. Individuals with a social network to communicate immunization are less hesitant to get the COVID-19 vaccine. A significant portion of HCWs obtain the information of COVID-19 vaccines from the staffs at CDC, and the opinions of colleagues and friends would also influence their vaccination decisions. The threshold degree of the influential members was set at 5 in SNA in order to maximize the sphere of influence and communication efficiency for future intervention while minimizing the number of targeted members due to limited resource. Twenty-two most influential members of the network with degrees greater than 5 are identified. It is further understood that most of the individuals in the vaccination consulting network are willing to get COVID-19 vaccines, and the most influential individuals in the network are department leaders with a bachelor’s degree. Combined with the findings that HCWs who live with children are less hesitant and those who report a history of vaccine hesitancy and refusal are more hesitant, the department leaders who live with children and get influenza vaccination before could be facilitated by CDC staffs to build and grow their consultation social networks actively. Through this strategy, COVID-19 vaccination rate can be improved.

A further analysis by stratification reveals that the lack of the vaccination consulting network has a strong influence on the vaccine hesitancy only among HCWs in secondary hospitals. This finding may be attributed to the fact that HCWs in primary hospitals are deeply engaged in the vaccination campaign and members in their social network are more willing to be vaccinated. HCWs in tertiary hospitals are unfamiliar with immunization work, and members in their social network are more hesitant toward vaccines. This result does not disapprove the influence of social network on vaccine hesitancy. Instead, it points out the importance of including HCWs from secondary hospitals in the social network, particular in a network with influential members from primary hospitals, as a way of reducing vaccine hesitancy.

The advantages of our study include a large sample size with participants from hospitals at all three care levels in China, as well as that a wide range of possible correlates are examined. This study also focuses on the communication among HCWs from hospitals of different care levels in a particular geographical area, which can be used to analyze the influence of socialization on vaccination willingness. The way of distributing QR codes by hospital management ensures that the participants have an equal opportunity to participate in this study.

A key limitation of this study is the self-administered survey design. In order to ensure the quality of the survey, we set up jump and logic controls for the questionnaire. An additional limitation is the lack of available data on non-respondents. Given that the data collection occurred during the early stages after the approval of the COVID-19 vaccine, the actual acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines may be under estimated as the vaccine acceptance rate would continue to improve (e.g. with more evidence on vaccine safety and efficacy becomes available. Next, we need to further study the influence of social network on vaccine hesitancy by the snowballing method. This survey method takes the influenced individuals in the consulting network as the starting point, and continuously collects new individuals mentioned by existing individuals in the network until no more new person is mentioned. Then a network with a directed and/or ranked relation can be mapped and a more detailed evaluation to understand the influence of social network can be done.

Conclusions

COVID-19 vaccination is a key public health strategy to fight the pandemic. Our study provides an early insight into the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines among HCWs. While the results indicate that many HCWs in China are willing to get vaccinated, the acceptance level needs to be further increased as HCWs is a special group facing a high risk of COVID-19 infection, and their participation in COVID-19 vaccination program would set a good example for the general population. Our results highlight that hesitant subgroups among HCWs in China are linked to the age, health status, care level of hospitals, working area, living arrangement, history of vaccine hesitancy and refusal, perceived risk of infection, and especially the lack of a social network to communicate COVID-19 immunization. It is therefore crucial to commence an information campaign based on our findings to increase the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among HCWs as soon as possible. Department leaders with a bachelor’s degree who are willing to receive vaccines should be regarded as key figures to enhance the vaccine uptake among HCWs. Particular focus should be put on the young HCWs and the HCWs with chronic diseases who are working in tertiary hospitals, because the former will set an example for other youths and the latter have a higher risk when infected.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Qing Wang; study design, Binyue Xu and Qing Wang; data analysis, Binyue Xu, Yi Zhang; investigation, Lei Chen, Linling Yu, Lanxin Li; resources, Yi Zhang; data curation, Binyue Xu; writing—original draft preparation, Binyue Xu; writing—review and editing, Yi Zhang, and Qing Wang; visualization, Binyue Xu; supervision, Binyue Xu; project administration, Binyue Xu; funding acquisition, Binyue Xu. All authors involved in the discussion of results and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research is an interview survey in nature and hence is exempted from the IRB review. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Supplemental Material

Download ()Supplemental Material

Download ()Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express great appreciation to all the participants in the hospitals for their assistance in the data collection of the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participant’s privacy concerns.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.2004837

Additional information

Funding

References

- China Daily Global. Countries gear up to secure virus vaccines. 2020 Dec 8 [accessed 2020 Dec 8]. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202012/08/WS5fced522a31024ad0ba9a77e.html.

- Goldstein A, Clement S. 7 in 10 Americans would be likely to get a coronavirus vaccine, post-ABC poll finds. The Washington Post. 2020 May 25–28 [accessed 2020 Jun 18]. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/7-in-10-americans-would-be-likely-to-get-acoronavirus-vaccine-a-post-abc-poll-finds/2020/06/01/4d1f8f68-a429-11eabb20-ebf0921f3bbd_story.html.

- Scott EB, Gregory AH, Alan SG, Erin KJ, Saad BO. Timing of COVID-19 vaccine approval and endorsement by public figures. Vaccine. 2021;39(5):825–29. PMID: 33390295. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.048.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccines. 2021 Feb 18 [accessed 2021 Feb 18]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines.

- Wang XD. China grants conditional approval for first COVID vaccine. China Daily. 2020 Dec 31 [accessed 2020 Dec 31]. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202012/31/WS5fed3411a31024ad0ba9fc58.html.

- Kwok KO, Li KK, Wei WI, Tang A, Wong SYS, Lee SS. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;114(12):103854. PMID: 33326864. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854.

- World Health Organization. Vaccine acceptance is the next hurdle. 2020 Dec 4 [accessed 2020 Dec 4]. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/vaccine-acceptance-is-the-next-hurdle.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, . Communication on immunization - building trust. Stockholm, Sweden; 2012. p. 4–6.

- Verger P, Fressard L, Collange F, Gautier A, Jestin C, Launay O, Raude J, Pulcini C, Peretti-Watel P. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners and its determinants during controversies: a national cross-sectional survey in France. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(8):891–97. PMID: 26425696. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.018.

- Grech V, Bonnici J, Zammit D. WITHDRAWN: vaccine hesitancy in Maltese family physicians and their trainees vis-à-vis influenza and novel COVID-19 vaccination. Early Hum Dev. 2020;11(12):105259. PMID: 33213968. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105259.

- Zhang L, Rong F, Ma L, Guo CH, Li XH, Yin PC, Gao F, Yang J. Research on the status of doctor-patient trust in different levels of hospitals in Beijing. Med Soc (Berkeley). 2020;1(33):85–88. doi:10.13723/j.yxysh.2020.01.020.

- Maconachie M, Lewendon G. Immunising children in primary care in the UK - what are the concerns of principal immunisers? (Special issue: health promotion and public health across the UK). Health Educ J. 2004;63(1):40–49. doi:10.1177/001789690406300108.

- Rubin GJ, Potts HWW, Michie S. Likely uptake of swine and seasonal flu vaccines among healthcare workers. A cross-sectional analysis of UK telephone survey data. Vaccine. 2011;29(13):2421–28. PMID: 21277402. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.035.

- Raftopoulos V. Attitudes of nurses in Greece towards influenza vaccination. Nurs Stand. 2008;23(4):35–42. PMID: 19051532. doi:10.7748/ns2008.10.23.4.35.c6675.

- Karafillakis E, Dinca I, Apfel F, Cecconi S, Wűrz A, Takacs J, Suk J, Celentano LP, Kramarz P, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):5013–20. PMID: 27576074. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029.

- Thompson MG, Gaglani MJ, Naleway A, Ball S, Henkle EM, Sokolow LZ, Brennan B, Zhou H, Foster L, Black C, et al. The expected emotional benefits of influenza vaccination strongly affect pre-season intentions and subsequent vaccination among healthcare personnel. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3557–65. PMID: 22475860. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.062.

- Sanchel S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus2. Emerging Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–77. PMID: 32255761. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200282.

- Bartsch SM, O’Shea KJ, Ferguson MC, Bottazzi ME, Wedlock PT, Strych U, McKinnell JA, Siegmund SS, Cox SN, Hotez PJ, et al. Vaccine efficacy needed for a COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine to prevent or stop an epidemic as the sole intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:493–503. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.011.

- Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, Tardy B, Rozaire O, Frappe P, Botelho-Nevers E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross-sectional survey. J Hosp Infect. 2021;108:168–73. PMID: 33259883. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. PMID: 33669441. doi:10.3390/vaccines9020160.

- Wang K, Wong ELY, Ho KF, Cheung AWL, Chan EYY, Yeoh EK, Wong SYS. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020;38(45):7049–56. PMID: 32980199. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.021.

- Wang J, Feng Y, Hou Z, Lu Y, Chen H, Ouyang L, Wang N, Fu H, Wang S, Kan X, et al. Willingness to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine among healthcare workers in public institutions of Zhejiang province, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;2,17(9):2926–33. PMID: 33848217. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1909328.

- Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Huang J, Cheung AWL, Law K, Chong MKC, Ng RWY, Lai CKC, Boon SS, Lau JTF, et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2021;39(7):1148–56. PMID: 33461834. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083.

- Wang Q, Xiu S, Zhao S, Wang J, Han Y, Dong S, Huang J, Cui T, Yang L, Shi N, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China-a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(4):342. PMID: 33916277. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040342.

- Yu Y, Lau JTF, She R, Chen X, Li LP, Li LJ, Chen X. Prevalence and associated factors of intention of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers in China: application of the health belief model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(9):2894–902. PMID: 33877955. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1909327.

- Gan L, Chen Y, Hu P, Wu D, Zhu Y, Tan J, Li Y, Zhang D. Willingness to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and associated factors among Chinese adults: a cross sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb;18(4):1993. PMID: 33670821. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041993.

- Chew NWS, Cheong C, Kong G, Phua K, Ngiam JN, Tan BYQ, Wang B, Hao F, Tan W, Xiaofan Han X, et al. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers’ perceptions of, and willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;106:52–60. PMID: 33781902. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.069.

- Suo L, Ma R, Wang Z, Tang T, Wang H, Liu F, Tang J, Peng X, Guo X, Lu L, et al. Perception of the COVID-19 epidemic and acceptance of vaccination among healthcare workers prior to vaccine licensure - Beijing municipality, China, May-July 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3(27):569–75. PMID: 34594938. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.130.

- MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. PMID: 25896383. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Wang XD. Vaccine gets conditional approval for general use. China Daily. 2021 Jan 1 [accessed 2021 Jan 1]. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202101/01/WS5fedfae4a31024ad0ba9febf.html.

- Wang C, Han B, Zhao T, Liu H, Liu B, Chen L, Xie M, Liu J, Zheng H, Zhang S, et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2021;39(21):2833–42. PMID: 33896661. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.020.

- Ye X, Ye W, Yu J, Gao Y, Ren Z, Chen L, Dong A, Yi Q, Zhang C, Lin Y, et al. Factors associated with the acceptance and willingness of COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese healthcare workers. medRxiv. 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.05.15.21257094.

- Xu B, Gao X, Zhang X, Hu Y, Yang H, Zhou YH. Real-world acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines among healthcare workers in perinatal medicine in China. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):704. PMID: 34199143. doi:10.3390/vaccines9070704.

- Wang Y, Dong L, Liang Y, Guo Z, Cheng J, Liu Y, Li Y. Willingness for COVID-19 vaccination and influencing factors in nurses from Tangshan city, China: a cross-sectional study. Res Square. 2021. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-275435/v1.

- Sun Y, Chen X, Cao M, Xiang T, Zhang J, Wang P, Dai H. Will healthcare workers accept a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available? A cross-sectional study in China. Front Public Health. 2021;9:664905. PMID: 34095068. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.664905.

- Zhou Y, Wang Y, Li Z. Intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 among nursing students: a cross-sectional survey. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;107:105152. PMID: 34600184. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105152.

- Wang MW, Wen W, Wang N, Zhou MY, Wang CY, Ni J, Jiang JJ, Zhang XW, Feng ZH, Cheng YR. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers in China: a survey. Front Public Health. 2021;9:709056. PMID: 34409011. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.709056.

- Li XH, Chen L, Pan QN, Liu J, Zhang X, Yi JJ, Chen CM, Luo QH, Tao PY, Pan X, et al. Vaccination status, acceptance, and knowledge toward a COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional survey in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;3:1–9. PMID: 34344260. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1957415.

- Jiang N, Wei B, Lin H, Wang Y, Chai S, Liu W. Nursing students’ attitudes, knowledge and willingness of to receive the coronavirus disease vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55:103148. PMID: 34311170. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103148.

- Chambers D, Wilson P, Thompson C, Harden M. Social network analysis in healthcare settings: a systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e41911. PMID: 22870261. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041911.

- Zhu Y. A preface to culture and self. J Ningbo Univ (Educ Sci Ed). 2007;29(3):1–2. doi:10.3969/j.1008-0627.2007.03.001.

- Butlera R, MacDonald NE; The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Diagnosing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in specific subgroups: the guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4176–79. PMID: 25896376. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.038.

- Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–90. PMID: 25896377. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040.

- Konala VM, Adapa S, Naramala S, Chenna A, Lamichhane S, Garlapati PR, Balla M, Gayam V. A case series of patients co-infected with influenza and COVID-19. J Invest Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620934674. PMID: 32522037. doi:10.1177/2324709620934674.

- Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. PMID: 32838242. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. PMID: 24598724. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- Leask J. Target the fence-sitters. Nature. 2011;473(7348):443–45. PMID: 21614055. doi:10.1038/473443a.

- Goldstein S, MacDonald NE, Guirguis S; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Health communication and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4212–14. PMID: 25896382. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.042.

- McAteer J, Yildirim I, Chahroudi A. The VACCINES act: deciphering vaccine hesitancy in the time of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):703–05. PMID: 32282038. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa433.

- Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang SY, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population level COVID-19 mortality. MedRxiv. 2020;35(10):3097–99. PMID: 32754782. doi:10.1101/2020.05.07.20094250.

- Rodriguez SA, Mullen PD, Lopez DM, Savas LS, Fernández ME. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the U.S.: a systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev Med. 2019;131:105968. PMID: 31881235. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105968.

- Stefanoff P, Sobierajski T, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Augustynowicz E. Exploring factors improving support for vaccinations among Polish primary care physicians. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232722. PMID: 32357190. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232722.

- Aris E, Montourcy M, Esterberg E, Kurosky SK, Poston S, Hogea C. The adult vaccination landscape in the United States during the affordable care act era: results from a large retrospective database analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(14):2984–94. PMID: 32115298. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.057.