ABSTRACT

Influenza is associated with a substantial disease burden, and influenza vaccination is recommended to all healthcare workers. We aimed to assess healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices about influenza and its vaccine in Chongqing, China. A cross-sectional study was conducted at selected hospitals from September to November 2019, in which healthcare workers filled in a self-administered questionnaire. Both sentinel (42.92%) and non-sentinel hospitals (57.08%) were included. The majority were nurses (52.48%) and physicians (32.37%). Half (50.42%) of the respondents had a good command of knowledge, and the proportion of healthcare workers having a positive attitude accounted for 62.68%. The primary information sources were colleagues (58.81%), followed by television, newspapers and media (30.18%). The number of healthcare workers reported having got vaccinated last year was only 237 (16.78%), and the main reason was protecting themselves from influenza (93.25%). While the most common reasons given for not getting vaccinated were having no time (65.70%), believing it is unnecessary to get vaccinated (29.62%), worrying about the quality of influenza vaccine (27.49%) or the adverse reactions (25.70%). Factors associated with self-reported high vaccination were sentinel hospital (aOR: 1.427; 95% CI: 1.057–1.925), high-risk department (aOR: 1.919; 95% CI: 1.423–2.589), positive attitude (aOR: 2.429; 95% CI: 1.697–3.477) and taking the initiative to learn influenza information (aOR: 3.000; 95% CI: 1.983–4.538). We concluded that healthcare workers in Chongqing had some misconceptions although many of them showed a positive attitude toward the influenza vaccine. Various strategies, including educational training and on-site vaccination, are necessary to improve the knowledge and overall vaccination coverage.

Introduction

Influenza is a contagious respiratory disease caused by influenza viruses. It is different from common cold, and symptoms usually come out suddenly, including fever, cough, sore throat, headache, musculoskeletal pain, and malaise. It may also lead to serious and life-threatening complications, including upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia.Citation1 Annual seasonal influenza epidemics have a prominent impact on the morbidity and mortality of global population; there are estimated 1 billion influenza cases annually, of which 3 to 5 million are severe cases, resulting in 290 000 to 650 000 influenza-related respiratory deaths.Citation2 In China, it was estimated that an average of 88 100 influenza-related excess respiratory deaths occurred each year from 2010 to 2015, equivalent to 8.2% of respiratory deaths,Citation3 and 456 718 reported influenza cases in 2017.Citation4–6 Furthermore, it was estimated that there was an average of 10 025 influenza-related deaths in Chongqing each year, accounting for 5.2% of the total deaths.Citation7

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are usually at higher risk of exposure to and possible transmission of the influenza virus than other populations due to the nature of their occupation that involves being in frequent contact with patients or infectious agents from patients. A meta-analysis showed that the incidence rate of influenza among unvaccinated HCWs was 18.7% (95% CI, 15.8–22.1%), which was 3.4 (95% CI, 1.2–5.7) times higher than that of healthy adults in non-healthcare workplaces.Citation8 Infected HCWs can spread influenza to patients, many of whom have serious underlying comorbidities, which can increase the risk of complications.Citation9 Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent influenza. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that HCWs be considered as a priority group for vaccination in 2012.Citation10 Similarly, in the Technical Guidelines for Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in China (2019–2020), issued by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, HCWs were the priority group for influenza vaccine.Citation11 Studies suggest that the influenza vaccination of HCWs can not only shorten the number of working days but also significantly reduce influenza-like illness and all-cause mortality among patients.Citation12,Citation13

The influenza vaccination rate of Chinese HCWs had been generally low before 2018, which was estimated to range from 5–18%.Citation14,Citation15 Numerous factors contribute to the low coverage. First, unlike some developed countries, the seasonal influenza vaccine is not included in the national Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI),Citation16 and influenza vaccination is generally voluntary and needs to be paid for out of pocket. Second, previous studies reported that HCWs’ poor awareness of risk, fear of side effects, misconceptions regarding vaccine safety and efficacy, and poor knowledge of influenza are the major obstacles to increase the influenza vaccination coverage.Citation17,Citation18

In October 2018, China’s National Health Commission issued an official document which set specific requirements for the vaccination of HCWs, requiring all medical institutions to provide free influenza vaccines for HCWs before influenza season.Citation19 A nationwide study aimed to investigate the status of the implementation of this policy and its effect on influenza vaccination coverage found that the seasonal influenza vaccine coverage among HCWs during the 2018/2019 season was only 11.6%.Citation20 However, there was a lack of data from Chongqing. This study aimed to investigate the knowledge and attitudes toward influenza and influenza vaccine among HCWs in Chongqing and to understand the factors influencing the vaccination rate during the 2018/2019 season.

Methods and materials

Study subjects

Based on the National Influenza Prevention and Control Scheme (pilot version) from China’s National Health Commission,Citation19 we classified respondents who worked in respiratory disease, infectious disease, pediatrics, and emergency departments as working in a “high-risk department,” those who worked in general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, laboratory and radiology as working in a “low-risk department.” In addition, hospitals that participate in the National Influenza Surveillance System were categorized as “sentinel hospital,” while the others were categorized as “non-sentinel hospital.” Our eligibility criteria for healthcare workers required those who had worked in the hospitals for at least one year, reported occupation as physician, nurse, laboratory and radiology technician, administrative support staff, and gave their written, informed consent to participate. Two-stage cluster random sampling was adopted for participant selection. In stage one, four out of 8 sentinel hospitals in Chongqing were randomly selected, and four non-sentinel hospitals from where the selected sentinel hospitals were located were randomly chosen as research sites. In stage two, HCWs worked in the high-risk departments and low-risk departments were randomly selected in each selected hospital as the study subjects.

Study design and data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional questionnaire survey from September to November 2019. Before the formal investigation, a pilot test was performed with a group of 50 HCWs to assess accessibility and comprehension, and the questionnaire was revised based on received feedback. Both online and offline approaches were used in distributing questionnaires; respondents had the option to complete paper questionnaires on-site or submit electronic questionnaires via the Wenjuanxing website. (a popular Chinese online survey platform:http://www.wjx.cn). Before each face-to-face survey began, an investigator went to the office to explain the study to the attending HCWs and collect their consent to participate in the study. Participants were also required to sign an informed consent before filling out the electronic questionnaire.

The final version of the questionnaire collected the following two aspects of information: respondents’ demographics and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) about influenza and influenza vaccine. Demographic variables included type of hospital, sex, age, educational attainment, marital status, working department, profession, years in profession, and job title. There were 18 statements included in the knowledge section, five of which were related to influenza on its transmission and prevention, and the others were associated with the influenza vaccine, including the effectiveness and side effects of influenza vaccine, the time, frequency, and the most recommended groups for vaccination. Participants would get 1 point for each statement they agreed to and no score for the “disagree” or “do not know” response. The total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 18.

There were a total of 7 statements set in the attitude section to understand the attitude of HCWs toward influenza vaccine about its’ safety, necessity, effectiveness, side effects, and the guidance of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on recommending annual influenza vaccination for healthcare workers. A five-point Likert scale was used to record the response of the participants, including “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree” in each question. Responses included “strongly agree” and “agree” were considered to agree with the statement, while the other responses were considered to disagree. To determine the attitude score, we assigned 1–5 points from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” respectively to each item, and the total attitude score ranged from 7 to 35.

There were 5 questions in the practice section which were designed to assess participants’ behaviors on the influenza vaccination. Three questions were used to evaluate participants’ influenza vaccination history, including “Have you received the influenza vaccine in the past year,” “What are the reasons for your influenza vaccination,” and “What are the reasons that you haven’t been vaccinated against influenza.” Two questions were related to participants’ behaviors on seeking influenza information, including the question “Did you take the initiative to learn influenza information” and a question aimed to investigate participants’ information sources of influenza vaccine.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (No.K2016038). After being explained the purpose of the research and agreeing to participant, written informed consent was signed by HCWs.

Statistical analysis

We reported frequency distributions of demographic variables, participants’ knowledge and attitudes of influenza and influenza vaccination; sources of information about influenza; and reasons for vaccination and non-vaccination. Knowledge and attitude score of each study participant was used to evaluate HCW’s knowledge and attitude level. A cutoff point was set based on respondent scores. For the knowledge section, the median score was 15, hence those below 15 scores were categorized as having poor knowledge and those with 15 and above scores as having good knowledge. Further, attitudes were classified as being negative if the score was below the median score of 26 and positive if the score was 26 and above.

We used logistic regression to analyze associations between demographics, whether to take the initiative to learn influenza information, HCWs’ knowledge and attitude, and self-reported influenza vaccination status in the previous year. Significance was evaluated through the Wald Chi-square test. Variables found to be significant at p < .05 from unadjusted analyses were included in forward step-wise multi-variable logistic regression models to evaluate associations with influenza vaccination status. Variables with the smallest p-value from unadjusted analyses were added one at a time to the forward stepwise regression models and removed at a p < .10 significance level. Findings were presented with crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% CI and p-value. The level of significance was set at p < .05 in a two-tailed fashion. All analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows software version 25.

Results

This survey collected 1412 valid questionnaires, covering 4 sentinel hospitals (N = 606,42.92%) and 4 non-sentinel hospitals (N = 806,57.08%). The number of HCWs working in high-risk and low-risk departments was 628 and 784, accounting for 44.48% and 55.52% respectively. Among the participants, there are more females (N = 1102,78.05%) than males (N = 310,21.95%), the mean age is 32.36 ± 7.78 years, and most of the participants were 30 years old or below (N = 737,52.20%). The respondents were mainly nurses (N = 741,52.48%) and physicians (N = 457,32.37%). The details of the demographic characteristics of each occupation were shown in .

Table 1. The demographic information of all HCWs, physicians, nurses, and others in Chongqing during the 2018/2019 influenza season

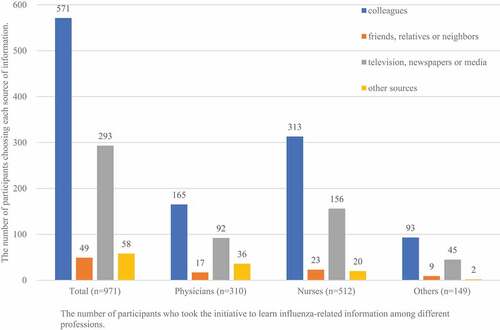

Regarding knowledge of influenza, almost all participants (1395,98.65%) believed that influenza is transmitted primarily by coughing and sneezing. But only 714 (50.57%) HCWs responded believed that mask wearing can limit the spread of influenza. Regarding knowledge of influenza vaccine, most of the participants (1316,93.20%) agreed that HCWs are the priority group for influenza vaccination. But only 77.12% (1089) reported to know that influenza vaccination should be given once a year. See for details. The median and inter-quartile range of knowledge scores were 15 (IQR:13–16). Out of 1412 respondents, 50.42% (n = 712) had 15 and higher knowledge scores and had been categorized as with good knowledge of influenza and influenza vaccine. Furthermore, there were 971 (68.77%) HCWs who took the initiative to focus on influenza-related information, and the most common source reported was colleagues (571,58.81%). The proportion of other information sources for each occupation were shown in .

Table 2. Healthcare workers’ knowledge about influenza and influenza vaccine, Chongqing, 2018–2019 influenza season (n = 1412)

Figure 1. Sources of influenza-related information for all HCWs, physicians, nurses, and others in Chongqing, 2018–2019 influenza season.

The attitude statements and possible responses are shown in . More than half (52.55%) agreed with the statement that it’s important to get the influenza vaccine every year. And 64.59% of HCWs responded worrying about the side effects of the influenza vaccine. The median and inter-quartile range of attitude scores were 26 (IQR:24–28). And a total of 62.68% (n = 885) have been considered to have a positive attitude toward influenza vaccine according to the definition of positive attitude in Methods.

Table 3. HCWs’ attitude toward influenza vaccine, Chongqing, 2018–2019 influenza season (n = 1412)

237 (16.78%) HCWs self-reported vaccination for seasonal influenza in 2018. Among different professions, the vaccination rate of nurses was the highest (18.35%), followed by physicians (17.29%), and the other HCWs were the lowest (10.28%). The details of other groups can be seen in . Subgroup analysis of different occupations revealed that participants who worked in sentinel hospitals were more likely to be vaccinated than in non-sentinel hospitals among physicians (22.99 vs 13.91) and nurses (21.47 vs 15.71). Regarding the department, the vaccination rate of physicians and nurses working in the high-risk department (22.57%,22.92%) was higher than that of those working in other departments (12.12%,13.08%). Among physicians and nurses, participants who had a positive attitude had a higher vaccination rate than those who had a negative attitude (physicians:22.22 vs 8.13; nurses:23.84 vs 9.72). In addition, HCWs who took the initiative to learn influenza information had a higher vaccination rate among all professions. For different knowledge levels, only among nurses, the vaccination rate of those with good knowledge was higher than that of those with poor knowledge (22.78% vs 15.06%)(Table S1).

Table 4. Influenza vaccination coverage of 1412 HCWs in Chongqing during the 2018/2019 influenza season

After adjusting for those variables at a significance level of p < .05 in univariate analysis (including the type of hospital, working department, profession, years in profession, knowledge level, attitude, taking the initiative to learn influenza information), the final multivariable logistic regression model for self-reported influenza vaccination status showed that the odds of self-reported influenza vaccination coverage were 1.427 times higher for sentinel hospital than non-sentinel hospital (95%CI:1.056–1.925), were 1.919 times higher for those who worked in high-risk department with low-risk department for reference (95%CI:1.423–2.589), and were 2.429 times higher for those having a positive attitude toward influenza vaccine than those having negative attitude (95%CI:1.697–3.477). Compared with those who didn’t take the initiative to learn influenza information, those who got information from various sources initiatively had higher vaccination coverage, the odds was 3.000 (95%CI:1.983–4.538). The details were shown in .

Among the 237 vaccinated HCWs, the most common reasons for vaccination were protecting themselves from influenza (221,93.25%), followed by the recommendation from government and health authorities (104,43.88%), and we also found this pattern among physicians and nurses. Of the respondents who did not get vaccinated, the most common reasons were having no time (65.70%), believing it is unnecessary to get vaccinated (29.62%), worrying about the quality of influenza vaccine (27.49%), or worrying about the adverse reactions after vaccination (25.70%). These four reasons were also common reasons for not getting vaccinated in all three professions ().

Table 5. Reasons for influenza vaccination and non-vaccination among all HCWs, physicians, nurses, and others in Chongqing, 2018–2019 influenza season

Discussion

Although healthcare workers were recommended to be given priority to influenza vaccination, previous studies among Chinese HCWs reported that their influenza vaccination coverage was extremely low.Citation14,Citation15 In our study, the influenza vaccination coverage of healthcare workers in Chongqing during the 2018/2019 influenza season was 16.78%, which was slightly higher than the national average level of HCWs in the 2018/2019 season (11.6%).Citation20 However, it was still far below the 80% vaccination rate threshold, which was proposed to achieve herd immunity within healthcare facilities for seasonal influenza,Citation21 and also much lower compared to other countries, such as the United States (78.4%).Citation22 This difference was probably due to the different vaccination policies of China and other countries. In China, influenza vaccine is generally paid for out-of-pocket and there is no national immunization program for influenza. While in the US, the mandatory influenza vaccination of HCWs has been introduced a decade ago.Citation23 The official document requiring all medical institutions to provide free influenza vaccination for HCWs was issued by China’s National Health Commission in 2018 for the first time.Citation19 However, there was no clear guidance on its implementation or enforcement for this free vaccination policy at the healthcare facility level. It seems that the policy has not been well implemented in most hospitals in Chongqing, China. And further evaluation will be needed to monitor the effects of the policy in the future.

A review conducted by Schumacher et al found that mandatory vaccination policies are effective measures to achieve high overall vaccination coverage.Citation24 Mandatory vaccination policies for specific vaccinations have been currently implemented in 13 European countries and are likely to be increasingly adopted given the expected increase in vaccination hesitancy.Citation25 A mixed designed study among HCWs in England showed that acceptance of the mandatory vaccination policy is limited, as some HCWs believe it unethical to force a healthcare worker to be vaccinated and HCWs should have the right to refuse vaccination, even though it would have a positive impact on coverage, thereby reducing the risk of influenza transmission and minimizing the disease burden.Citation26 Mandatory influenza vaccination is still in debate. It is necessary for China, a country with the largest health workforce in the world (12.3 million HCWs by the end of 2018),Citation27 to further examine whether to implement the policy of compulsory influenza vaccination.

The results showed that only half of HCWs in Chongqing had a good knowledge of influenza and its vaccine. The proportion of participants who knew that HCWs were the priority group for influenza vaccination was 93.20%, which was higher than that of Austria (66.4%).Citation28 However, critical gaps in knowledge were also identified, such as only 50.57% of participants believed that wearing masks can limit the spread of influenza, and only 58.00% agreed that the immunity afforded by the influenza vaccine is better than the natural immunity. There is a lack of knowledge about influenza and its vaccine. So it is important to ensure that opportunities are provided for HCWs to regularly update their knowledge of current guidelines and other relevant information related to influenza and its vaccine.

In this study, 62.68% of HCWs showed a positive attitude toward influenza vaccination, which contrasted with the findings from other studies that showed general positive attitudes toward influenza vaccination in HCWs.Citation29,Citation30 In the systematic review by Schmid et al.Citation31 the most common reasons why HCWs did not want to get the influenza vaccine were reported as the lack of confidence due to misconceptions about the vaccine and low awareness of the seriousness of the disease. The low seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among HCWs in our study may be attributed to misconceptions as well. The main misconceptions found in our study were disbelief that it’s important to get the influenza vaccine every year (52.55%) and worrying about the side effects of the influenza vaccine (64.59%). The result was supported by the finding of participants who had a negative attitude toward the influenza vaccine were more unlikely to get vaccinated.

HCWs who took the initiative to learn about the influenza vaccine accounted for 68.77%, and the most common source was from their colleagues (58.81%), in contrasts to the study in Honduras, which cited scientific literature on the Internet or medical textbooks as primary sources of information.Citation32 Another main source in our study was television, newspapers and media (30.18%), which was in accord with previous studies.Citation33,Citation34 Our study found that the most common reason for the influenza vaccination of HCWs was protecting themselves from influenza, which was consistent with another study performed in Austria.Citation28 About 83% of participants did not receive the influenza vaccine, and the majority part of them considered having no time as the reason for not being vaccinated (65.70%). This outcome has already been highlighted in a previous study,Citation32 showing the time constraints were the most common access limitations for non-vaccination. This reminds us that easy access to and availability of the influenza vaccine is crucial to improve vaccine coverage. A study in Singapore found on-site vaccination arrangements improved the proportion of vaccinated hospital employees from 56.8% to 66.4%.Citation35 Furthermore, offering vaccination during work hours can also improve acceptance. Another main reason in our study for non-vaccination was considering it unnecessary to vaccinate. This is consistent with other studies.Citation36,Citation37 However, a Pakistani study conducted by Ali et al. showed that the unfamiliarity with the influenza vaccine availability, shortage of proper storage area and cost were the main reasons.Citation38 We also found some HCWs were not vaccinated due to worries about the quality or adverse reactions of the influenza vaccine. This is in line with a study conducted in Switzerland.Citation39

This study revealed that working in sentinel hospital or high-risk department were associated with a high vaccination rate. Sentinel hospital‐based influenza‐like illness (ILI) surveillance network has been established in mainland China to monitor influenza activity.Citation40,Citation41 HCWs working in the sentinel hospital are responsible for the daily task of registering and reporting influenza cases. Both HCWs in sentinel hospital and high-risk department have more opportunities to have contact with influenza patients and are more likely to be vaccinated against influenza to protect themselves. Also, the sentinel hospital and high-risk department usually carry out more training on influenza prevention and treatment knowledge, and correspondingly, these HCWs have a stronger awareness of influenza vaccination, which may be the reason for their higher vaccination rate. We found that positive attitude was an important factor affecting the influenza vaccination rate of HCWs. As reported in a previous study, higher attitude scores were concomitantly associated with greater vaccination.Citation32 HCWs who took the initiative to learn influenza information were more likely to be vaccinated, perhaps because they were more likely to have a positive attitude toward the influenza vaccine.

The vaccination of HCWs against influenza is associated with a social responsibility to protect others, especially the seriously sick and people in hospitals.Citation42 Given the low vaccination rate among HCWs in Chongqing, a combination of education about the responsibility for oneself and others, and awareness of the need for annual influenza vaccinations can have a positive effect. An awareness-raising campaign in Brazil encouraging HCWs to vaccinate against influenza successfully increased the percentage of vaccinated medical staff to 34%, however, the lack of its continuation caused a decrease to 20% in the next year and 12% after two years; the author concluded that more appealing and convincing continuous education programs are needed to ensure motivation for influenza vaccination over a longer period.Citation43 HCWs should believe that all vaccines are safe and useful, and they should regard vaccination both as a right and as a duty to protect themselves and their patients.Citation44 The epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) broke out during the peak season of influenza in China. As both of them were viral respiratory diseases with similar clinical symptoms, such as fever, cough, myalgia, and fatigue,Citation45,Citation46 which has attracted indirect public attention to influenza. And more academic studies should be conducted to raise influenza vaccination coverage in the future.

Study limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first to measure the HCWs’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward influenza and its vaccine in Chongqing. This study has several limitations. First, the fact that vaccination status was self-reported and not being verified through records constitutes a limitation. HCWs may have falsely claimed that they had been vaccinated against influenza due to social pressure. Second, our research samples are only from secondary and tertiary hospitals, lacking research data from primary healthcare institutions, and may not well represent all HCWs. Thirdly, this research design adopted the KAP model, which exists an uncertain logical relationship among individuals’ knowledge, attitude and practice. More updated conceptual frameworks will be needed to study the behavior of influenza vaccination of HCWs. Fourthly, as a cross-sectional study, this study can not evaluate the free vaccination policy outcome well, and future studies should continue to pay attention to policy implementation. Lastly, since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread enormous information about viruses in general, and HCWs, in particular, would have had more opportunities to learn about infectious diseases than before and they will have better knowledge and a more positive attitude to influenza and its’ vaccines. Besides, our study took place before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results may be quite different from the current situation.

Conclusion

This survey confirms some misconceptions toward influenza and influenza vaccine and low vaccination coverage of healthcare workers in Chongqing. The outbreak of COVID-19 once again warned all nations to be vigilant against the influenza pandemic and the attention of health policymakers is needed. We concluded that various strategies, including educational training regarding awareness about vaccinations and on-site vaccination, are required to improve the knowledge and influenza vaccination coverage.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all the healthcare workers who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.2007013.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key facts about influenza (flu). [ accessed 2020 Dec 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/keyfacts.htm

- World Health Organization. New global influenza strategy. [ accessed 2021 Jan 10]. https://www.who.int/news/item/11-03-2019-who-launches-new-global-influenza-strategy

- Li L, Liu Y, Wu P, Peng Z, Wang X, Chen T, Wong JYT, Yang J, Bond HS, Wang L, et al. Influenza-associated excess respiratory mortality in China, 2010-15: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(9):E473–E81. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(19)30163-x.

- Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1285–300. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33293-2.

- World Health Organization. Fact sheet on seasonal influenza. [ accessed 2021 Jan 10] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal)

- National Health Commission of the PRC. National notifiable disease fact sheet in 2017–2018. [ accessed 2020 Dec 25]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3578/201802/de926bdb046749abb7b0a8e23d929104.shtml

- Qi L, Li Q, Ding X-B, Gao Y, Ling H, Liu T, Xiong Y, Su K, Tang W-G, Feng L-Z, et al. Mortality burden from seasonal influenza in Chongqing, China, 2012-2018. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(7):1668–74. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1693721.

- Kuster SP, Shah PS, Coleman BL, Lam -P-P, Tong A, Wormsbecker A, McGeer A. Incidence of influenza in healthy adults and healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026239.

- Bridges CB, Kuehnert MJ, Hall CB. Transmission of influenza: implications for control in health care settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(8):1094–101. doi:10.1086/378292.

- World Health Organization. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper - November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012 Nov 23;87(47):461–76. English, French. PMID: 23210147.

- National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) Technical Working Group (TWG), Influenza Vaccination TWG. Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China, 2019-2020. Chin J Epidemiol. 2019;40(11):1333–49. (in Chinese). doi:10.3760/cma.j.0254-6450.2019.11.002.

- Kliner M, Keenan A, Sinclair D, Ghebrehewet S, Garner P. Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers in the UK: appraisal of systematic reviews and policy options. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012149. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012149.

- Ahmed F, Lindley MC, Allred N, Weinbaum CM, Grohskopf L. Effect of influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel on morbidity and mortality among patients: systematic review and grading of evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(1):50–57. doi:10.1093/cid/cit580.

- Song Y, Zhang T, Chen L, Yi B, Hao X, Zhou S, Zhang R, Greene C. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination among high risk groups in China: do community healthcare workers have a role to play? Vaccine. 2017;35(33):4060–63. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.054.

- Lee PH, Cowling BJ, Yang L. Seasonal influenza vaccination among Chinese health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(5):575–78. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.038.

- General Office of the State Council of People’s Republic of China. National regulation for vaccine distribution and administration (2016 version). [ accessed 2021 Jan 10]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-04/25/content_5067597.htm

- Khan TM, Khan AU, Ali I, Wu DB. Knowledge, attitude and awareness among healthcare professionals about influenza vaccination in Peshawar, Pakistan. Vaccine. 2016;34(11):1393–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.045.

- James PB, Rehman IU, Bah AJ, Lahai M, Cole CP, Khan TM. An assessment of healthcare professionals’ knowledge about and attitude towards influenza vaccination in Freetown Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):692. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4700-2.

- China’s National Health Commission. National influenza prevention and control scheme (pilot version). [ accessed 2021 Jan 25]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s7923/201810/b30b71408e5641c7a166d4e389318103.shtml

- Liu H, Tan Y, Zhang M, Peng Z, Zheng J, Qin Y, Guo Z, Yao J, Pang F, Ma T, et al. An internet-based survey of influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers in China, 2018/2019 season. Vaccines (Basel). 2019;8(1):6. doi:10.3390/vaccines8010006.

- Maltezou HC. Nosocomial influenza: new concepts and practice. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21(4):337–43. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283013945.

- Black CL, Yue X, Ball SW, Fink RV, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Williams WW, Graitcer SB, Fiebelkorn AP, Lu P-J, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel - United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR. 2018;67(38):1050–54. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a2.

- Maltezou HC, Theodoridou K, Ledda C, Rapisarda V, Theodoridou M. Vaccination of healthcare workers: is mandatory vaccination needed? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(1):5–13. doi:10.1080/14760584.2019.1552141.

- Schumacher S, Salmanton-Garcia J, Cornely OA, Mellinghoff SC. Increasing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a review on campaign strategies and their effect. Infection. 2020;49(3):387–99. doi:10.1007/s15010-020-01555-9.

- Maltezou HC, Botelho-Nevers E, Brantsaeter AB, Carlsson R-M, Heininger U, Hubschen JM, Josefsdottir KS, Kassianos G, Kyncl J, Ledda C, et al. Vaccination of healthcare personnel in Europe: update to current policies. Vaccine. 2019;37(52):7576–84. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.061.

- Stead M, Critchlow N, Eadie D, Sullivan F, Gravenhorst K, Dobbie F. Mandatory policies for influenza vaccination: views of managers and healthcare workers in England. Vaccine. 2019;37(1):69–75. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.033.

- China National Health Commission. Statistical bulletin on the development of health career in China in 2018. [ accessed 2021 Jan 25]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10748/201905/9b8d52727cf346049de8acce25ffcbd0.shtml

- Harrison N, Brand A, Forstner C, Tobudic S, Burgmann K, Burgmann H. Knowledge, risk perception and attitudes toward vaccination among Austrian health care workers: a cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(9):2459–63. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1168959.

- Alharbi N, Almutiri A, Alotaibi F, Ismail A. Knowledge and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of influenza vaccination in the Qassim region, Saudi Arabia (2019-2020). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(5):1426–31. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1820809.

- Alshammari TM, Yusuff KB, Aziz MM, Subaie GM. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude and acceptance of influenza vaccination in Saudi Arabia: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4054-9.

- Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker M-L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior - a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005-2016. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170550. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170550.

- Madewell ZJ, Chacon-Fuentes R, Jara J, Mejia-Santos H, Molina IB, Alvis-Estrada JP, Ortiz MR, Coello-Licona R, Montejo B. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of seasonal influenza vaccination in healthcare workers, Honduras. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246379. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246379.

- Rachiotis G, Mouchtouri VA, Kremastinou J, Gourgoulianis K, Hadjichristodoulou C. Low acceptance of vaccination against the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) among healthcare workers in Greece. Euro Surveillance. 2010;15(6):19486. PMID: 20158980.

- Chor JSY, Pada SK, Stephenson I, Goggins WB, Tambyah PA, Clarke TW, Medina M, Lee N, Leung TF, Ngai KLK, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination predicts pandemic H1N1 vaccination uptake among healthcare workers in three countries. Vaccine. 2011;29(43):7364–69. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.079.

- Lee HY, Fong YT. On-site influenza vaccination arrangements improved influenza vaccination rate of employees of a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(7):481–83. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2006.10.007.

- Korkmaz N, Nazik S, Gumustakim RS, Uzar H, Kul G, Tosun S, Torun A, Demirbakan H, Seremet Keskin A, Kacmaz AB, et al. Influenza vaccination rates, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of healthcare workers in Turkey: a multicentre study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(1):e13659. doi:10.1111/ijcp.13659.

- Xu L, Zhao J, Peng Z, Ding X, Li Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Zheng J, Cao H, Ma B, et al. An exploratory study of influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers in a western Chinese city, 2018–2019: improving target population coverage based on policy interventions. Vaccines. 2020;8(1):92. doi:10.3390/vaccines8010092.

- Ali I, Ijaz M, Rehman IU, Rahim A, Ata H. Knowledge, attitude, awareness, and barriers toward influenza vaccination among medical doctors at tertiary care health settings in Peshawar, Pakistan-a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2018;6:173. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00173.

- Durovic A, Widmer AF, Dangel M, Ulrich A, Battegay M, Tschudin-Sutter S. Low rates of influenza vaccination uptake among healthcare workers: distinguishing barriers between occupational groups. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48(10):1139–43. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.02.004.

- Yu H, Alonso WJ, Feng L, Tan Y, Shu Y, Yang W, Viboud C. Characterization of regional influenza seasonality patterns in China and implications for vaccination strategies: spatio-temporal modeling of surveillance data. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001552. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001552.

- Xu C, Cowling BJ, Chen T, Wang L, Zhang Y, Huang D, Yang L, Yang J, Huang W, Wang D, et al. The heterogeneity of influenza seasonality by subtype and lineage in China. J Infect. 2020;80(4):469–96. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2019.11.017.

- Maltezou HC, Poland GA. Immunization of healthcare providers: a critical step toward patient safety. Vaccine. 2014;32(38):4813–13. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.046.

- Takayanagi IJ, Alves Cardoso MR, Costa SF, Araya MES, Machado CM. Attitudes of health care workers to influenza vaccination: why are they not vaccinated? Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(1):56–61. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2006.06.002.

- Orr P. Influenza vaccination for health care workers: a duty of care. Can J Infect Dis. 2000;11(5):225–26. doi:10.1155/2000/461308.

- Hu D, Lou X, Xu Z, Meng N, Xie Q, Zhang M, Zou Y, Liu J, Sun G, Wang F. More effective strategies are required to strengthen public awareness of COVID-19: evidence from google trends. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):011003. doi:10.7189/jogh.10.011003.

- Prati C, Pelliccioni GA, Sambri V, Chersoni S, Gandolfi MG. COVID-19: its impact on dental schools in Italy, clinical problems in endodontic therapy and general considerations. Int Endod J. 2020;53(5):723–25. doi:10.1111/iej.13291.