ABSTRACT

In places with low overall cycling levels, the uptake by people of older ages tends to be especially marginal. This study observes that current cycling promotion in low-cycling cities does not change this tendency and argues that the ageing of urban populations increasingly requires action to address this gap. In response, it aims to understand the cycling trajectories of older adults who cycle or aim to take up cycling. The analysis focuses on their long-term mobility biographies, reporting from qualitative and mobile research methods applied in the city of Barcelona. This paper makes insightful how later life cycling is conditioned by interactions with the urban and social environment, but also how it carries essential qualities for positive ageing. The findings indicate that cycling currently relies on intrinsic mobile capacities that make it exclusive, less achievable as everyday transport mode, and less likely to endure over the lifecourse. The paper concludes that aspiring cycling cities should pay special attention to populations with less cycling representation and makes the case to advance age-friendliness in research and urban policies that wish to build-in and maintain cycling mobility across a wider demographic.

1. Introduction

1.1. Cycling transitions and urban change

In recent years, many cities have witnessed profound transitions towards sustainable mobilities. New infrastructures and planning tools such as street pacification, cycle lanes, and tactical urbanism interventions are being implemented to re-appropriate urban space. Though initially perceived as progressive measures, these interventions are now often part of governance repertoires around ‘green’ urban reform, new ways of living and moving, and create new distributions of materialities, technologies and socialities within cities (Graziano, Citation2021; Honey-Rosés et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, these transitions have raised ethical and distributive concerns, as they may fail to alleviate structural inequalities and exclusions within urban mobility (Oscilowicz et al., Citation2022; Oviedo et al., Citation2022). In fact, the evidence accumulates that new mobility infrastructures and uses reproduce the neoliberal and regulatory frames that organize and distribute commodities and people unequally, exclusively, and unsustainably within cities (Anaya-Boig et al., Citation2021; Arsenio et al., Citation2016; Spinney, Citation2017; Tironi, Citation2015; Wild et al., Citation2018).

With mobilities are at the centre of today’s urban change, they have become a political and value-charged product that visibly and experientially transforms public spaces according to certain social, cultural and aesthetic norms (Hagen & Rynning, Citation2021; Stefansdottir, Citation2014). Aims to promote cycling are often essential elements of these transformations, which warrants a critical approach towards the possible in- and exclusions and the social and spatial behaviours inserted into the urban landscape. Cycling studies have not only outlined the many barriers to uptake among different social groups in a variety of cycling contexts (Félix et al., Citation2019; Fowler et al., Citation2017; Garrard et al., Citation2008; Parkin et al., Citation2007), but have also started to uncover the structural limitations of current operationalisations of ‘cycling cities’. For instance, cycling has been cited to act as ‘mobility fix’ to improve and intensify travel flows (Spinney, Citation2017), to brush-up political or corporate imageries (Medeiros & Duarte, Citation2013; Tironi, Citation2015) and as vehicle that worsens socio-spatial inequality and gentrification (Golub et al., Citation2016; Stehlin, Citation2015; Wild et al., Citation2018). Various authors have therefore proposed to challenge assumptions around mobility and accessibility, to question the place of mobility in cities itself (Van Der Meulen & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2021), and to appreciate the utility of (cycling) mobility beyond its moving speed, potential travel time reduction or alleviation of traffic congestion (Te Brömmelstroet et al., Citation2021).

1.2. Cycling uptake in older age

This paper responds to these concerns by expanding the empirical work on age-friendly cycling (Den Hoed & Jarvis, Citation2022). The following paragraphs link the integrative focus of the Age-Friendly Cities framework and literature on cycling inclusion to study the urban elements that support or hinder cycling uptake in later life. Indeed, older people are a typically underrepresented group in cycling (Garrard et al., Citation2021), seen as unable to take up cycling (Leger et al., Citation2019), possibly as part of a wider claim of reduced rights to access the city (Menezes et al., Citation2021). It therefore develops the argument that a focus on fast cycling promotion, based on norms and narratives of efficiency, mode shift, and activeness distracts from the diversity of the meanings and practices of cycling. This article learns from ageing studies which conclude that older people’s access to urban space and social participation in the planning and design of the cities of the future is very limited despite their growing demographic, economic and social prominence (Buffel et al., Citation2021; Schwanen et al., Citation2012). In addition, the discourse that activeness itself is inherently good, particularly propelled in many cycling studies, may ignore ‘the reality that many older adults are restricted in their mobility, both indoors and outdoors’ and have to make choices to make their remaining mobility meaningful (Meijering, Citation2021, p. 712).

The current situation of older age cycling in many cities can be described as age-unfriendly. This applies to both ends of the age spectrum, as children and older people are often regarded as vulnerable road users and are less likely to cycle for everyday activities, especially in places with low cycling levels (Goel et al., Citation2022; Hull & O’Holleran, Citation2014). At the same time, both quantitative and qualitative engagements with older age cycling agree that, when perceived safe and convenient, it provides a vital tool for prolonged mobility and for social and health opportunities (Jones et al., Citation2017; Oja et al., Citation2011). In young ages, in turn, cycling may be transformative for independent mobility and convey skills and responsibilities that are essential for most of the lifecourse (Aldred, Citation2015; Kullman, Citation2010).

Limiting the scope of this paper to the case of older adults, it is largely unknown how this demographic group adopts or extends cycling mobility in a low-cycling context. As many low-cycling cities seek to step up to become more cycle-friendly (Félix et al., Citation2019), it is crucial to understand the mobility trajectories in which cycling is to be embedded and what social, spatial, and sensory experiences cycling in older age entails. In addition, cycling may build-in health prevention and opportunities for social and mental wellbeing into everyday mobility behaviours at a life stage in which isolation, loneliness and immobility are increasingly present (Schwanen et al., Citation2012; Shergold et al., Citation2015; Van Den Berg et al., Citation2016). For older people, regular cycling is a powerful source to maintain and improve cognitive functions and enhance preventive health and physical activity benefits (Garrard et al., Citation2021). Given these transformative capacities, outlined in a small set of studies on ‘older age cycling’ (e.g. Leyland et al., Citation2019; Spencer et al., Citation2019; Van Cauwenberg et al., Citation2022; Winters et al., Citation2015), and the combined challenges described above, this paper aims to focus on what makes cycling (un)likely among older people in an upcoming cycling city.

1.3. Cycling growth in low-cycling cities

Urban cycling growth reflects an international trend where urban mobility is being reoriented in line with sustainability, safety and health agendas, often as part of multi-modal mobility systems. Even so, many cities remain dominated by the private-motorised vehicle, reflected by the social normalisation of its use and the domination of the mobility experience of everyone in the city (Koglin & Rye, Citation2014; Urry, Citation2004). It is thus important to acknowledge that empirical work on cycling operates in places and communities dominated by the automobility system which has mediated all kinds of mobility experiences and everyday urban life under the guise of modernist agendas (Dowling & Simpson, Citation2013; Koglin & Rye, Citation2014). Consequently, it ‘coerces people into an intense flexibility’, which ‘forces people to juggle fragments of time so as to deal with the temporal and spatial constraints that it itself generates’ (Urry, Citation2004, p. 28). By extension, car use leads all people to live their lives in sprawling and time-compressed cities and to adapt their social norms accordingly (Manderscheid et al., Citation2014; Schwanen & Lucas, Citation2011).

As a consequence, cycling research shows how car-dominated societies have created exclusive cycling identities (Aldred, Citation2013) and, in this journal, how (prospective) cycling infrastructures are influenced by car-centric perspectives on what road spaces are for (Loyola et al., Citation2023). Among other effects, this logic conditions emerging cycling cities and thus the potential of the transition towards sustainable mobility, as cautious cycling growth often does not increase inclusion in terms of its users (Aldred et al., Citation2016; Goel et al., Citation2022) and of overall accesibility gains (Rosas-Satizábal et al., Citation2020). In addition, recent tactical reforms are often modifiable, with a consequent risk of reversal or lack of maintenance. The importance of permanence, maintenance and improvement, in fact, is demonstrated in the case of Seville (Spain) where cycling levels stagnated after a rapid surge between 2006 and 2011 (Marqués, Citation2022; Marqués et al., Citation2015).

From an equity point of view, aspiring cycling cites do not often achieve the improvement of mobility opportunities of groups who do not currently cycle (Arsenio et al., Citation2016; Doran et al., Citation2021). In low cycling contexts, men and adults under 50 tend to be overrepresented among those who cycle, while a more balanced gender and age distribution is only established in cities with longstanding higher cycling uptake (Aldred et al., Citation2016; Harms et al., Citation2014). Thus, despite initial cycling growth in some cities, structural limitations of the mobility system seem to persist. While important planning studies have developed tools to assess the quality of cycling infrastructure and its requirements for experienced and ‘new’ cyclists (Hagen & Rynning, Citation2021; Hull & O’Holleran, Citation2014), ‘[a] good quality cycling environment may be a necessary but not sufficient condition’ (Aldred, Citation2015, p. 93). In other words, the conditions for cycling adoption among currently underrepresented groups may also depend on factors beyond the physical environment.

1.4. Age-friendliness

Finally, paper takes inspiration from the Age-Friendly Cities (AFC) framework, which, in response to urbanisation and population ageing trends, has received following in research fields such as social gerontology and inclusive urban design, but less so in urban mobility planning (Murray, Citation2015). The AFC-concept informs this paper through three contributions. First, it divides urban daily life into eight domains (transport; outdoor space and buildings; housing; social participation; civic and labour participation; respect and social inclusion; health and community support; information and communication), all of equal importance and demonstrating the need for cross-sectoral coordination to address urban challenges (Van Hoof et al., Citation2021). Second, it promotes the friendliness of built environment elements to people of all ages, i.e. through interventions designed for older people that also benefit other population groups. Third, the framework centralises the role of the biographical trajectory as part of the different elements that constitute urban life and mobility experiences over time (Grenier, Citation2011). A simultaneous trend is witnessed in the study of mobility biographies, although usually without involving age-friendliness. For example, Berg et al. (Citation2014) argue that mobility behaviour depends on the structures and capacities that vary between life stages, while Rau and Sattlegger (Citation2018) highlight the gradual shift between different life stages and the effects of social relations on mobility practices.

Through these three contributions, the AFC-concept creates a basis to study cycling as part of all-else that constitutes quality of life in the city, to focus on particular environmental elements that support or hinder (cycling) mobility, and to take a biographical approach to the way in which cycling practices root in long-term mobile behaviours. In continuation, this paper outlines the operationalisation of this biographical approach to everyday urban cycling among older adults (Section 2), before presenting (Section 3) and interpreting (Section 4) the analytical findings in the light of the described challenges around cycling interventions in low-cycling cities.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study sample and analysis

This article concentrates on the cycling practices of people aged over 60 in the city of Barcelona. It reports from a study that undertook empirical research using qualitative and mobile methods with a sample of 37 older citizens to capture and understand their embodied experiences of cycling, relate their use to the ageing process and interpret the importance of biographical trajectories on current cycling behaviour. Firstly, interviews were undertaken about the following topics: the adoption of different urban travel modes over the lifecourse; the opportunities and hindrances associated with urban mobility in the past, present and (expected) future; and the extent to which the spatial context of the city affected the practice and experience of cycling. The interviews usually lasted 60 minutes and were generally conducted in Spanish, in a few cases in Catalan and English. The interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed using the software Trint, and corrected by the researcher. After the interviews, participants were invited to be accompanied on one of their usual journeys around the city, and, later on, were asked to participate in a focus group.

Secondly, therefore, the study undertook ride-alongs to observe participants’ bodily movements and experiences when cycling in and interacting with the urban space. The rides took place on routes that participants were accustomed to, in order to capture the more fleeting mobile sensations and to elicit responses to the urban cycling environment (Spinney, Citation2011). The rides were audio and video recorded using a clip-on microphone worn by the participants and an action camera mounted on the handlebars of the cycling researcher. This allowed the researcher to add into the analysis the conversations with the participant and notes about the flow of movement, physical effort, interactions with other actors, and decisions on-the-move. In some cases, after the bike ride, the video clips were discussed with participants, which helped to complete the interpretation of how cycling appealed to bodily capacities (reflexes, physical capacity, etc.), and how micro-decisions were made in different situations (Jones et al., Citation2017). Fourteen of the participants took part in the ride-alongs, which lasted between seven and 85 minutes depending on the chosen route. The audio recordings were transcribed, whereas the researcher watched the videos and annotated each clip with observational notes.

Thirdly, the study ended with focus groups to pool and discuss the shared motivations and barriers. Participants were presented with the initial analytical themes and were asked to write key words about the central question ‘what is it like to cycle in older age?’, before assigning these key words to one of the four parts of a SWOT matrix (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) and indicating whether they seconded the key words of fellow group members (Ibeas et al., Citation2011). Fifteen participants took part in two rounds of focus groups, and the session was audiorecorded and transcribed. Together, the transcriptions and observational notes from interviews, ride-alongs and focus groups were entered into the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti. Using thematic analysis, the data were categorised into codes and organised in relation to the main aims of this article: current uses and experiences; the cycling lifecourse; infrastructures and barriers; and ‘sensing’ older age, i.e. collecting experiences of changes in cycling and its compatibility (or not) with the ageing body.

The participants were contacted through a recruitment call distributed by local active travel-related organisations and through ensuing chain referral. Purposively, different levels of cycling experience were targeted, as well as a diversity of older ages and areas of residence. All research engagements took place between April and September 2022. The final sample has an average age of 67, an age range from 60 to 88 and consists of a near gender balance. Their characteristics, including the period in which they are considered urban cyclists, are presented in . In all instances, they participated under informed consent, while identifiable details were anonymised in the analysis and their names pseudonymised in compliance with GDPR, ethics and data management procedures.

Table 1. Socio-demographic profile of the study sample.

2.2. Study context

The city of Barcelona, the principal case of this study, is one of several cities worldwide that has seen a boom in cycling infrastructure and use in recent years. In its intentions to become a cycling city, the number of cycle lane kilometres has more than doubled between 2016 and 2022, whereas other interventions include street pacification and lowering vehicle speeds so that ‘cyclable streets’ emerge. In terms of modal share, the municipality expects the combined share of cycling and e-scooter use to grow from 2.3% of trips in 2018 to 5% by 2024 (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2020). The annual survey which asks individual residents for their principal urban travel mode shows a higher average use (7.8% for cycling), but also indicates large variations by neighbourhood, with cycling being almost non-existent in more hilly parts of the city. Demographic variations are substantial as well, with lower use among women and only 0.6% of people over 65 reporting cycling as primary mobility option (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2022). The promotion of more a sustainable mobility system and increasing the accessibility of its public spaces have been key elements of its municipal agenda of the years 2015–2023 (Blanco et al., Citation2020).

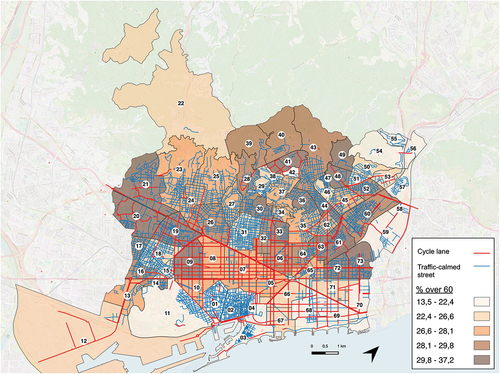

Based on the aforementioned annual survey, presents the trend in cycling uptake by age group over the last ten years, showing a persistently low proportion for the over-64 group and substantial growth in other age groups. In turn, displays the current distribution of the cycling network, consisting of cycle lanes and traffic-calmed streets, as well as the percentage of people over 60 living in each neighbourhood. Lastly, it is worth noting that overall, one in three residents of Barcelona will be over 60 in 2030 (21% in 2018), meaning that by today’s standards, much of the population may have less access to cycling interventions and its network of cycle lanes and shared ‘cyclable’ spaces (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2018, Citation2023). Notably, the role of the city’s orography is such that many of the hillier areas also contain higher shares of older populations. In these north/north-western parts, streets are usually narrow, with little through traffic but almost completely without dedicated cycling spaces (). This coincides with risks of reduced accessibility of parts with a greater slope (Rhoads et al., Citation2023) and lower provision of public bikeshare installations (Bustamante et al., Citation2022).

Figure 1. Cycling uptake by age group in the municipality of Barcelona between 2011 and 2021 (own bike and bicing shared bike). Source (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2022).

Figure 2. Map with % of people aged over 60 per neighbourhood and the cycle network in the municipality of Barcelona (list of neighbourhood names). Source (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2022).

3. Findings

The thematic analysis resulted in three key themes that provide insight into the degree of age-friendliness of cycling in the case study city. This section presents the spatialities and temporalities of cycling among the study participants, the process of normalisation of cycling over the lifecourse, and the qualities cycling may offer in later life.

3.1. Older age cycling in Barcelona

The cycling maps and documents of Barcelona show a relatively integrated network that covers most of central and flatter areas of the city. It contains a triple typology of cycle lanes, 30 km/h zones and traffic calmed, ‘cyclable streets’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona, Citation2023). However, when analysing the behaviour of participants, it can be observed that the spaces used for cycling are much more diverse than this typology. The old town generally consists of one-lane, one-way street sections, which sometimes have signs or road markings indicating cycling priority. The maximum speed here varies between 10, 20 and 30 km/h. It is important to note that, at the time of the study, the two axes connecting the old city, the Eixample area and the coast, Las Ramblas and Via Laietana, did not have specific infrastructure for cyclists. At most transport nodes around the old city, which connect important traffic axis and residential neighbourhoods and include Plaça Espanya, Plaça Catalunya, Plaça Universitat and Plaça Urquinaona, dedicated and connected cycling infrastructure is absent too.

The Eixample district, in turn, surrounds the old town and is characterised by an orthogonal grid of long, straight and wide avenues. It has cycle lanes on most ‘horizontal’ streets, i.e. parallel to the coast, and ‘vertical’ ones, between the coast and the mountains, most of which are one-directional, in line with the direction of car traffic (see also ). The space dedicated to motorised traffic on the Eixample streets varies between one and six one-directional lanes. The absence of cycle lanes on some streets, especially in coast-mountain direction, and their one-way nature prevents people from cycling in any given direction in the Eixample district, forcing them to make detours or use streets without a cycle lane. Lastly, the cycling behaviour of the participants in the study indicates a frequent use of pacified streets, such as ‘Superblocks’Footnote1 or single-platform areas, due to their low traffic density and speed.

Although relatively clear-cut on paper, the observations of where people cycle thus indicate a high diversity. This variation is even greater when also including the other spaces where people cycle, beyond the ones indicated on the cycling map (). Participants additionally use wide pavements, pedestrian crossings, open squares, single platform streets, and shortcuts that allow them to connect between dedicated cycling spaces. They frequently indicate that not all dedicated cycling spaces have adequate sizes, contain inconsistencies in their design or deficits in signage and navigation. Therefore, they often find themselves in spaces that do not meet inclusive design principles of coherent, well-communicated, continuous and safe cycling spaces (Doran et al., Citation2021).

The analysis also shows that the cycling network serves a range of other vehicles, such as personal mobility vehicles (mostly e-scooters), delivery vehicles, and wheelchairs. Especially the variety of vehicles that use the narrower, bidirectional lanes are found problematic. As Carles (72, Interview) sums up: ‘The safety on the bike lanes partly depends on the other vehicles that get on it. Other bikes, e-scooters, skateboards and all sorts. Sometimes they provoke you, or in any case they overtake you at touching distance, at high speed’.

The impact of motorised traffic is strongly noticed on the cycling network when (parked) cars block the view from the cycle lanes and, especially, when they are illegitimately used by car and van drivers. Both the interviews and the ridealong observations show frequent interruptions by parked vehicles which block the path of cyclist or hinder their continuity. Some participants demonstrate how they circumvent this problem, drawing on experience gained over the years, by braking, accelerating, getting off the bike, or looking for another way through. More generally, they also display certain tactics to avoid busy areas or rush hours, take detours and, therefore, cannot choose freely when and where to cycle. In some cases, this led to postponing or cancelling the journey. During ride-alongs, participants also highlight a frequent lack of smooth connections between junctions, the lack of protection from turning vehicles, long waiting time at traffic lights, and a lack of signage, visibility and spaces to stop or wait.

Notably, participants highlight that the situation is worse at the city limits. For instance, Marta’s (63) commute of c.8 kilometres covers the municipalities of Barcelona, Sant Adrià de Besòs and Badalona, in which she highlights the lack of metropolitan connections. Lluís (67, Focus Group), on the other hand, describes the precautions he takes when riding in Barcelona’s centre: ‘Las Ramblas is a 30 [km/h] street, but you are pushed by the cars that want to overtake you. To escape this pressure I went to the central part of Las Ramblas and walked to the intersection on foot’. A last impact of motorised traffic is noted by Mireia and Caleb (both 63, Interview), who adapt their choice of routes, times and areas where they cycle according to the air and noise pollution they experience when cycling in the city.

In a collective prioritisation exercise, carried out during the focus group, participants indicate that the greatest limitation to cycling in older age is imposed by the urban environment. They particularly highlight the danger caused by drivers of vans, cars and electric scooters, as well as their recklessness, improper use of the horn, and occasional insults. The city can be a hostile place to cycle, among others because of the bike theft risk, the pollution, insecurity about the continuity of the cycle lane, and the orography of the city. Also the more experienced cyclists indicate how they are aware of their physical fragility and how, over time, they have lost some agility, strength and the possibility to make themselves present and visible. For less experiences cyclists, it is precisely this fear that can dissuade them from cycling. Nora (60, Interview), who has recently taken up cycling lessons, explains the impossibility of adopting her recently acquired cycling skill in her everyday mobility, beyond the safe space near her house:

I remember once taking Bicing [the public bikeshare system], and it was a route that went along a very wide pavement. But of course, I was really scared when I got to the bollards at the end and stopped. I stopped because I wasn’t sure about everything (…). Maybe that’s why sometimes, I think about doing cycling as a sporting activity. Taking the bicycle as a means of transport scares me, I wouldn’t do it.

Despite the ongoing expressions of a hostile cycling environment and conflicts with other road users, participants’ overall impression is that of substantial improvement to cycling in the city. Not long ago, they were unable to cycle in the city, only on certain segments, or had to cycle between the multi-lane car traffic. Sara (60, Interview), who cycled as a ‘brave student’ in Barcelona, recalls that in the 1980s, ‘a bike was a hindrance [on the road], just like a pigeon’. When later, in the early 2010s, she started to work within the city, she took up a cycling commute using the Bicing shared bicycle system. About the improvements, she comments: ‘I see changes. Today they are more subtle, but there was a time with brutal changes. Because from not having a cycle lane to having a cycle lane is a change. Now they’re subtle, fixing things. People complain about many things in the city, but with bikes they’ve been very good’.

3.2. Normalisation of cycling in everyday mobility

The different levels of incorporating cycling in everyday mobility shows that uptake depends on normalisation – the consideration of behaviours and activities as ‘normal’ to the extent that they are taken for granted without question. For many participants, cycling started at young age and continued with occasional and recreational use, for instance playfully in childhood, when in the summer village, with own children, as a sport, or on holidays. Although they were indispensable first steps, less experienced participants find it difficult to ‘scale up’ this kind of cycling into everyday mobility. As shown for Nora’s case, uptake in the city may be limited to enclosed and quiet areas, or to a single known cycle lane, while avoiding areas with heavy traffic and unpredictable situations. This shows the importance of skill and learning: whereas the capability to cycle is usually acquired at a young age, the acquisition of habitual cycling is what solidifies it as a mobility practice in later life.

Besides relying on cycling experiences at younger age, participants explain how this acquisition happens in other places where they are or were more comfortable to cycle. Usually, these are smaller villages where they have family or spend summer. Nàdia (65, Interviews), who takes cycling lessons to be able to cycle in Barcelona, explains: ‘my daughter lives in the Penedès [rural] area. So there, a village with small roads among the vineyards, where there is no one, I do take the bicycle’. From these experiences, people derive a sense of latent interest to cycle in Barcelona. Nàdia, who now usually walks in the city, thus begins to envisage her cycling possibilities: ‘I often tell myself “you could go this way or that way if you went to this or that place”. On routes that I usually take [by foot], you can see parts that now have a [cycle] lane’.

For cycling to enter mobility routines in the city, however, it is also crucial that the skill is seen as feasible and safe in relation to other transport options. Returning to Nora’s example: ‘Cycling in the Eixample is overwhelming. Even if there are lanes, the whirlwind of people and crowds is a bit much for me, at my age and in my situation’. Besides the need for a safe cycling environment, participants specify different trigger points that have helped them to envision cycling in later life. These triggers may be infrastructural, such as the arrival and expansion of the Bicing shared system between 2007 and 2012 (see Sara’s case in 3.1). Such triggers form an essential basis for the permanent adoption of cycling, which for these participants happened between the ages of 45–60 and in markedly worse cycling conditions than those of today. Another trigger point in later life is retirement, which may spark the pursuit of new plans. In some cases, cycling is a project to achieve or challenge oneself to undertake a new activity. Many plan to cycle more with friends, as social activity or to visit places together, whereas a few participants also expect that they will cycle more instead of using the motorbike out of safety concerns.

For the more experienced cyclists in this study, it is notable that they have actively pursued the inclusion of cycling in their everyday mobility patterns. They have now become accustomed to weighing different features of the trip including distance, the trip reason or the load to be carried, available time, alternatives, and possible companions. They express having created strategies for convenient cycle use, such as reserving a storage space within their flats, studying (outdoor) parking options, establishing a set of preferred routes, choosing the type of bicycle that suits each trip (e.g. Bicing, standard bike, folding bike, or electric assistance), or adapting schedules to avoid peak hours or the hottest times of the day. These strategies have come with experience gained over the years, through trial and error, often requiring extra physical effort and careful preparation.

When looking ahead to the role of cycling in their future mobility, most participants expect an adaptation of cycling to physical capabilities and emphasise the importance of social relations. Simón (64, Interview), for instance has clear role models for when he’s older: ‘I admire a couple who are very old, in their eighties, and still cycle. In some cases they are still going and I want to be like them’. In turn, the focus group participants see themselves as possible role models for younger generations under the heading ‘if we can do it, they can do it’. The adaptation of cycling to physical capabilities may already happen in the present, for instance when people develop knee or hip issues or return from illness. Flor (60, Interview) thus started to use an e-assisted cycle, that she now also expects to ensure her mobility in the years to come:

I developed knee arthrosis and I struggled [to cycle], especially on climbs and when starting at traffic lights. That first pedal stroke. But my husband gave me an electric model and it’s been fantastic because I can put just the right amount of assistance I need to pedal.

Similarly, Kyle (76, Interview), who lives in a hilly part of the city, talks about how he manages the expectations about his cycling pace: ‘When I feel out of breath, I just stop. I don’t owe anyone anything, I’m not racing. I’d have a one-minute rest and continue. I can get up very steep hills by that process. And slowly, even five, six kilometres an hour. (…) So that is my strategy for the future’. Besides past and current cycling experiences, skill building, and future aspirations, it thus appears that the possibility to adapt cycling practices, paces and rhythms to new capabilities is necessary for future uptake in everyday mobility.

3.3. Cycling qualities in older age

As we already saw in Flor’s example (3.2), there is an important relationship between cycling and health. Some participants have experienced periods of setbacks in which cycling was a way to distract themselves or a vehicle to regain strength or confidence. For Jordi (88, Interview), cycling offers support when he cares for his partner who lives in a nursing home. Although he still cycles as many journeys as possible, it is notable that what inhibits his cycling today is not the urban environment or his physical strength, but the fact that his cycling companions are no longer able to:

Well, friends disappear. Some because of illness, others because they have moved away. Others because they have died. So what happens then is that the friends who remain are the ones who are younger than you. The friends that survive are all between 10 and 15 years younger than me. And now even the one who is 15 years younger than me can’t go anymore either.

Direct (social) wellbeing benefits, however, are not often the primary motivation to cycle: for most participants, cycling is simply a tool to maintain mobility options. Many therefore welcome the ability to adapt cycling to their own pace, measuring efforts, and taking routes of their own preference. In particular, many participants not only look to ride on cycle lanes, but also in traffic-calmed streets or areas shared with pedestrians. Lluís (67, Ridealong) explains how he prefers these lower speeds, even along the busy pedestrian area of Passeig de Gràcia: ‘Cars can also drive here, but what they can’t do is rush, because they know there are a lot of pedestrians. For me, this solution to put the pavement at the same level as the [car] lane and have a wide promenade seems a good idea to me’.

As we have seen in other instances, the acquisition of an electric or folding bike allow participants to regulate their cycling effort speed, not worry about parking, or to be more open to their surroundings, for instance in the hillier parts: ‘Now with the electric one I go all over Barcelona. There are beautiful lanes in every neighbourhood. In Tres Torres, Sarrià, Poblenou, Horta’ (Gerard, 71, Interview). Participants adhere explicit importance to the security and self-confidence cycling offers, now or in the future, especially when normally feeling frail or vulnerable in public spaces. Similarly, they note the ability for enjoyment, to ‘keep an open mind’ (Focus Group theme), to move oneself without polluting or using transport that is ‘aggressive’ to others (Daniela, 60, Interview), and the sense of achievement gained from moving under one’s own steam.

In this sense, it is clear that cycling can be a tool for longevity, compatible with the needs and abilities of older age. Besides the promotion of physical activity, it also allows people to stay mentally fit, offering a sense of community, a role in society, and opportunities for exploration and reliving memories. This societal role – making a contribution with one’s actions – leads to a feeling of social responsibility and influence, especially when witnessing the effects of car-based alternatives (pollution, sedentary lifestyles) from nearby. Some participants also suggest that later life cycling makes them feel young again, especially when cycling more after retirement. In Eva’s case (67, Interview), this feeling is met with (too) much enthusiasm:

I even feel young, sometimes I have to tell myself ‘hey, I’m 67 years old, I can’t do crazy things’, as if I were the young girl who was always cycling in summer (…) Last time I had an accident, luckily I haven’t had many, because I forgot how old I am. I did a race with my grandson. And I started to race, really to win. And of course, right then my granddaughter called me, so I braked and fell off. (…) I forgot that I don’t have the age to race with a ten-year-old.

The current will to cycle also acts as an important motivator to be able to continue cycling and, importantly, also reaches beyond the municipal boundaries of the city. Especially more experienced cyclists frequently combine urban trips with recreational or social rides to the outskirts, countryside or nearby coastal areas. Noemi (N, 75) and Vera (V, 78), in a joint ridealong, tell how they use their conventional folding bikes to visit the coastal towns around Barcelona, up to Calella, around 60 kilometres away:

‘When we go out, we go along the Besòs [river park], going as far as Moncada and even to Cerdanyola. We go to El Prat, Gavà, Castelldefels and vice versa. And last year in summer, I convinced them to go to Calella, where we went to the beach’.

‘And we went for a swim!’

The physical and mental wellbeing benefits, social relations, and adaptability that characterise older age cycling were brought together during the focus group sessions. Importantly, cycling embeds a series of positive ageing feelings within everyday mobility patterns (the wind in your face, the sun on your skin, getting around healthily, interactions with other generations, greeting people during spontaneous encounters). The participants also express several functional later life qualities such as the larger action radius and the door-to-door nature of cycling, which is especially important when walking or carrying goods requires much energy. At the same time, several participants comment how they feel different to others of their age or different from who they were a few years ago. They consider themselves more active, and for instance participate in hobbies such as handicrafts, hiking, arts and crafts, and choir singing or partake in social campaigns, activism or volunteering. In other cases, they simply feel more optimistic: ‘Well, I can be in a bad mood, but I try to see the glass as half full (…). If I compare myself with my surroundings, I see it’s very difficult for people to be tolerant. And I see people who don’t sport and don’t have energy. They watch TV on the sofa. All the friends I have take sleeping pills. I don’t take them and I sleep like a queen’ (Noemi, 75, Interview).

4. Discussion and conclusion

This article has combined research on cycling inclusion and age-friendliness to examine the lived experience of cycling mobility by older adults in an emergent cycling city. It has focused on the urban elements that support or hinder cycling in later life and has explored how current cycling practices root in long-term mobility trajectories. Foremostly, though, it has advanced the Age-friendly City (AFC) framework to study cycling as part of all aspects that constitute mobility and quality of life in the city. Its holistic and cross-sectoral approach has been useful to study urban cycling as part of different life domains (e.g. transport, outdoor activity, as tool for social, civic, and intergenerational participation, and in support of health and community-building) (Van Hoof et al., Citation2021). By tracing longstanding and short-lived cycling trajectories, this article has taken the case of Barcelona to nuance the transformative capacities of transitions towards sustainable mobilities, at least when current convictions about the place of mobility in the city and surrounding power structures are not challenged (e.g. Golub et al., Citation2016; Stehlin, Citation2015; Van Der Meulen & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2021). New infrastructures and planning tools such as street pacification and cycle lanes are benefitting people who currently cycle, but, especially in the older demographic, continue to contain structural barriers to attracting new or inexperienced cyclists.

The qualitative and mobile research methods applied in this study provide an initial picture of the reasons for the underrepresentation of older adults in emergent cycling cities (Félix et al., Citation2019). Despite substantial improvements of the cycle network, people ultimately have to rely on ingrained skills and capacities and an active pursuit to include cycling in everyday mobility patterns. In that sense, the lack of full network connectivity, coherent and legible design, and metropolitan links are directly reducing the initial uptake of cycling, its expansion for different uses and purposes, or its durability over the lifecourse. These barriers are reinforced by the ‘overwhelming’ transport environment which also intrudes the dedicated cycling space used by the participants (Dowling & Simpson, Citation2013; Manderscheid et al., Citation2014). The widespread presence of motor vehicles, thus, hinders cycling directly through their manoeuvres (turning, parking) and indirectly through their space claim and noise and air pollution. Consequently, while cities may improve cycling facilities, their interference in (non-motorised) urban spaces that could make cycling a safe, physically moderate and convenient mobility option is a testimony of an unfinished cycling city.

In extension, as long as the cycling practices, negotiations, and conflicts found in this study persist, it is likely that socially and ecologically progressive mobility transitions may drive the exclusion of the less-likely agents in urban change (Menezes et al., Citation2021). Among the widespread insertion of cycling in urban sustainability discourses, it would be timely to consider their implications on age equity; in part because the growing demographic, economic and social relevance of older age groups and in part because of the transforming capacities of independent, meaningful and active mobility in later life (Garrard et al., Citation2021; Leger et al., Citation2019). For instance, beside the importance of continuously maintaining and improving cycling facilities (Marqués et al., Citation2015), cities wishing to improve their mobility and quality of life opportunities should also focus on the maintenance of cycling as attainable travel option in individual mobile biographies.

In terms of cycling planning and design, future research should therefore focus on the appropriate dimensions for different social groups, whether currently cycling or not, perhaps broadening the conception of the cycle lane to reflect the diversity of its users. Even though Barcelona’s cycling network is relatively recent, its users, vehicles and speeds are already manifold. The preoccupation of most participants with their safety indicates that these profiles are already too diverse for their dimensions. In this sense, it is striking that they face a significant incongruity between the political reality of an integrated cycling network (incl. typologies of cycle lanes, 30 km/h zones, and cyclable streets) and the lived reality of disruption and discontinuity. On the other hand, the role of mobility biography indicates that a possible shift to cycling is not limited to physical infrastructure. The presence of cycling in everyday mobility routines originates in key triggers that originate in the urban environment (e.g. the arrival or extension of cycle lanes or public rental systems), but also in the individual biography (e.g. a relocation, disruption, encouragement from a significant other, environmental concern) in various stages of life. At the same time, its normalisation process as part of everyday urban mobility often spans many years, relying on childhood memories and experiences, shorter-lived periods of cycle use, materialities of the bicycle (folding, electric bikes), and the adaptability of cycling uses as people get older, showing that increased urban cycling is not a one-on-one reflection of new or expanding cycling infrastructures (as in Den Hoed and Jarvis (Citation2022) for the case of a high-cycling city).

Based on the case of older age cycling in an emergent cycling city, this study distinguishes three essential requirements for an age-friendly cycling future. First, it is key to reduce the emphasis of cycling mobility on physical and cognitive effort. The ‘pacification’ of the cycling experience and lowering the need for high awareness and physical strength is what allowed older adults in this study to cycle, to cycle more, or for longer. Second, the planning focus should move from the assumed need for speed and efficiency towards the durability of active and sustainable mobilities and the rehabilitation of public spaces for meaningful, satisfactory and intergenerational uses (Arsenio et al., Citation2016; Murray, Citation2015; Te Brömmelstroet et al., Citation2021). Third, the definition of cycling infrastructure would benefit from an expansion. The material and socio-biographical requirements for cycling uptake extends from the time and place where one considers taking the bike to the ride itself, and up to the possibility to keep cycling compatible with changing bodily needs and capacities. For those cycling in later life, the bicycle may act as a prosthesis, malleable in its material form and adaptable following bodily capabilities and social and mobile functions. These functions should complement the physical infrastructure visions that underlie emergent cycling cities’ aspirations.

This paper’s findings reinforce the assumption that cycling transitions are more than a ‘mobility fix’ (Spinney, Citation2017). For the case of cycling in older age, it has shown an empowering role in any part of life, ranging from work-based to care-related uses to social and recreational activities. Cycling and its qualities are derived from a diverse set of journeys that include functions of mobility, health, wellbeing and positive ageing. For a cycling transition that is inclusive and equitable, it is imperative to make these opportunities easily attainable for groups that are now less likely to cycle. In an ageing society, the plurality of ages and abilities must be recognised, as well as the multimodal realities in which the analysed mobility biographies took place (Berg et al., Citation2014; Rau & Sattlegger, Citation2018). A true cycling city would move away from the logic of having a single main mode, with a range of ‘alternative’ travel forms, to make space for mobilities that are in tune with the human capacity to move around by their own means or using limited assistance. Contrary to car-centric planning or its derivatives, cycling transitions should always be part of wider urban change objectives that are not limited to one travel mode (cycling) or are not even premised on promoting mobility itself.

A more systematic operationalisation of the AFC-framework and an all-age-based right-to-the-city concept in research and policy would offer the integrated and cross-sectoral approach needed to mainstream cycling beyond the mobility sphere, notably in public health, urban ageing, social welfare, and economic activity. In mobility planning, an age-friendly approach could be the onset to assess places as ‘cyclable’ for all ages and abilities and, perhaps more importantly, to reduce the politicisation that surrounds current urban mobility transitions. First, an age-inclusive and cross-sectoral approach to the social, cultural and aesthetic norms surrounding green transitions could create a broader understanding of their corresponding physical transformations. Second, it could widen the focus from the implementation of infrastructural technology towards all-else that matters to improve the quality of urban spaces for all citizens, regardless of political colour and mobile capacity.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 19o Congreso Ibérico La Bicicleta y La Ciudad. The author is grateful to the research participants who shared their valuable time and experiences and to the Bicicleta Club de Catalunya and Ms. Valentina González Alzola for respectively supporting its methodological development and the qualitative analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A set of multiple city blocks in which the road space has been redistributed to reduce the circulation and parking of private vehicles. This regeneration gives spaces to multiple public uses such as playgrounds, green spaces, neighbourhood services, comfort and resting spaces, and social and commercial activities.

References

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2018). Strategy for Demographic Change and ageing: A city for All Times of Life (2018-2030). Area of Social Rights.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2020). Pla de Mobilitat Urbana 2024 (Document per a la Aprovació Inicial). Direcció de Serveis de Mobilitat.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2022). Enquesta de Serveis Municipals (Survey on Municipal Services). https://dades.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/enquesta-serveis-municipals/

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2023). Plànol BCN: Xarxa de carrils bici. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/bicicleta/ca/serveis/vies-de-circulacio/xarxa-de-carrils-bici

- Aldred, R. (2013). Incompetent or too competent? Negotiating everyday cycling identities in a motor dominated society. Mobilities, 8(2), 252–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2012.696342

- Aldred, R. (2015). Adults’ attitudes towards child cycling: A study of the impact of infrastructure. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 15(2), 92–115. https://doi.org/10.18757/EJTIR.2015.15.2.3064

- Aldred, R., Woodcock, J., & Goodman, A. (2016). Does more cycling mean more diversity in cycling? Transport Reviews, 36(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1014451

- Anaya-Boig, E., Douch, J., & Castro, A. (2021). The death and life of bike-sharing schemes in Spain: 2003–2018. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 149, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.03.028

- Arsenio, E., Martens, K., & DiCiommo, F. (2016). Sustainable urban mobility plans: Bridging climate change and equity targets? Research in Transportation Economics, 55, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2016.04.008

- Berg, J., Levin, L., Abramsson, M., & Hagberg, J.-E. (2014). Mobility in the transition to retirement – The intertwining of transportation and everyday projects. Journal of Transport Geography, 38, 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.05.014

- Blanco, I., Salazar, Y., & Bianchi, I. (2020). Urban governance and political change under a radical left government: The case of Barcelona. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1559648

- Buffel, T., Yarker, S., Phillipson, C., Lang, L., Lewis, C., Doran, P., & Goff, M. (2021). Locked down by inequality: Older people and the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban Studies, 60(8), 1465–1482. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211041018

- Bustamante, X., Federo, R., & Fernández-I-Marin, X. (2022). Riding the wave: Predicting the use of the bike-sharing system in Barcelona before and during COVID-19. Sustainable Cities and Society, 83, 103929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.103929

- Den Hoed, W., & Jarvis, H. (2022). Normalising cycling mobilities: An age-friendly approach to cycling in the Netherlands. Applied Mobilities, 7(3), 298–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2021.1872206

- Doran, A., El-Geneidy, A., & Manaugh, K. (2021). The pursuit of cycling equity: A review of Canadian transport plans. Journal of Transport Geography, 90, 102927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102927

- Dowling, R., & Simpson, C. (2013). ‘Shift – the way you move’: Reconstituting automobility. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, 27(3), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2013.772111

- Félix, R., Moura, F., & Clifton, K. J. (2019). Maturing urban cycling: Comparing barriers and motivators to bicycle of cyclists and non-cyclists in Lisbon, Portugal. Journal of Transport & Health, 15, 100628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.100628

- Fowler, S. L., Berrigan, D., & Pollack, K. M. (2017). Perceived barriers to bicycling in an urban U.S. environment. Journal of Transport & Health, 6, 474–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2017.04.003

- Garrard, J., Conroy, J., Winters, M., Pucher, J., & Rissel, C. (2021). Older adults and cycling. In R. Buehler & J. Pucher (Eds.), Cycling for sustainable cities (pp. 237–255). MIT Press.

- Garrard, J., Rose, G., & Lo, S. K. (2008). Promoting transportation cycling for women: The role of bicycle infrastructure. Preventive Medicine, 46(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.010

- Goel, R., Goodman, A., Aldred, R., Nakamura, R., Tatah, L., Garcia, L. M. T., Zapata-Diomedi, B., de Sa, T. H., Tiwari, G., de Nazelle, A., Tainio, M., Buehler, R., Götschi, T., & Woodcock, J. (2022). Cycling behaviour in 17 countries across 6 continents: Levels of cycling, who cycles, for what purpose, and how far? Transport Reviews, 42(1), 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1915898

- Golub, A., Hoffmann, M., Lugo, A., & Sandoval, G. (Eds.). (2016). Bicycle justice and urban transformation: Biking for all? Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Graziano, T. (2021). Smart technologies, back-to-the-village rhetoric, and tactical urbanism: Post-COVID planning scenarios in Italy. International Journal of E-Planning Research, 10(2), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEPR.20210401.oa7

- Grenier, A. (2011). Transitions and the lifecourse: Challenging the constructions of ‘growing old’. Policy Press.

- Hagen, O. H., & Rynning, M. K. (2021). Promoting cycling through urban planning and development: A qualitative assessment of bikeability. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 9(1), 276–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2021.1938195

- Harms, L., Bertolini, L., & Te Brömmelstroet, M. (2014). Spatial and social variations in cycling patterns in a mature cycling country exploring differences and trends. Journal of Transport & Health, 1(4), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.09.012

- Honey-Rosés, J., Anguelovski, I., Chireh, V. K., Daher, C., Konijnendijk Van Den Bosch, C., Litt, J. S., Mawani, V., McCall, M. K., Orellana, A., Oscilowicz, E., Sánchez, U., Senbel, M., Tan, X., Villagomez, E., Zapata, O., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions – design, perceptions and inequities. Cities & Health, 5(sup1), S263–S279. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1780074

- Hull, A., & O’Holleran, C. (2014). Bicycle infrastructure: Can good design encourage cycling? Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 2(1), 369–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2014.955210

- Ibeas, A., Dell’olio, L., & Montequín, R. B. (2011). Citizen involvement in promoting sustainable mobility. Journal of Transport Geography, 19(4), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.01.005

- Jones, T., Chatterjee, K., Spencer, B., & Jones, H. (2017). Cycling beyond your sixties: The role of cycling in later life and how it can be supported and promoted. In C. Musselwhite (Ed.), Transport, travel and later life (pp. 139–160). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Koglin, T., & Rye, T. (2014). The marginalisation of bicycling in modernist urban transport planning. Journal of Transport & Health, 1(4), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.09.006

- Kullman, K. (2010). Transitional geographies: Making mobile children. Social & Cultural Geography, 11(8), 829–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2010.523839

- Leger, S. J., Dean, J. L., Edge, S., & Casello, J. M. (2019). “If I had a regular bicycle, I wouldn’t be out riding anymore”: Perspectives on the potential of e-bikes to support active living and independent mobility among older adults in Waterloo, Canada. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 123, 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.10.009

- Leyland, L.-A., Spencer, B., Beale, N., Jones, T., van Reekum, C. M., & Piacentini, M. F. (2019). The effect of cycling on cognitive function and well-being in older adults. PLoS One, 14(2), e0211779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211779

- Loyola, M., Nelson, J. D., Clifton, G., & Levinson, D. (2023). The influence of cycle lanes on road users’ perception of road space. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 11(1), 2195894. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2023.2195894

- Manderscheid, K., Schwanen, T., & Tyfield, D. (2014). Introduction to special issue on ‘mobilities and Foucault’. Mobilities, 9(4), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2014.961256

- Marqués, R. (2022). Cycling policies: Lessons from Seville. Mobile Lives Forum. https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/opinions/15715/cycling-policies-lessons-seville

- Marqués, R., Hernández-Herrador, V., Calvo-Salazar, M., & García-Cebrián, J. A. (2015). How infrastructure can promote cycling in cities: Lessons from Seville. Research in Transportation Economics, 53, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2015.10.017

- Medeiros, R. M., & Duarte, F. (2013). Policy to promote bicycle use or bicycle to promote politicians? Bicycles in the imagery of urban mobility in Brazil. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 1(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2013.866875

- Meijering, L. (2021). Towards meaningful mobility: A research agenda for movement within and between places in later life. Ageing and Society, 41(4), 711–723. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19001296

- Menezes, D., Woolrych, R., Sixsmith, J., Makita, M., Smith, H., Fisher, J., Garcia-Ferrari, S., Lawthom, R., Henderson, J., & Murray, M. (2021). ‘You really do become invisible’: Examining older adults’ right to the city in the United Kingdom. Ageing and Society, 43(11), 2477–2496. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001793

- Murray, L. (2015). Age-friendly mobilities: A transdisciplinary and intergenerational perspective. Journal of Transport & Health, 2(2), 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2015.02.004

- Oja, P., Titze, S., Bauman, A., de Geus, B., Krenn, P., Reger-Nash, B., & Kohlberger, T. (2011). Health benefits of cycling: A systematic review: Cycling and health. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 21(4), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01299.x

- Oscilowicz, E., Anguelovski, I., Triguero-Mas, M., García-Lamarca, M., Baró, F., & Cole, H. V. S. (2022). Green justice through policy and practice: A call for further research into tools that foster healthy green cities for all. Cities & Health, 6(5), 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2022.2072057

- Oviedo, D., Sabogal, O., Villamizar Duarte, N., & Chong, A. Z. W. (2022). Perceived liveability, transport, and mental health: A story of overlying inequalities. Journal of Transport & Health, 27, 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2022.101513

- Parkin, J., Ryley, T., & Jones, T. (2007). Barriers to cycling: An exploration of quantitative analyses. In D. Horton, P. Rosen, & P. Cox (Eds.), Cycling and Society (pp. 67–82). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Rau, H., & Sattlegger, L. (2018). Shared journeys, linked lives: A relational-biographical approach to mobility practices. Mobilities, 13(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1300453

- Rhoads, D., Solé-Ribalta, A., & Borge-Holthoefer, J. (2023). The inclusive 15-minute city: Walkability analysis with sidewalk networks. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 100, 101936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2022.101936

- Rosas-Satizábal, D., Guzman, L. A., & Oviedo, D. (2020). Cycling diversity, accessibility, and equality: An analysis of cycling commuting in Bogotá. Transportation Research Part D, 88, 102562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102562

- Schwanen, T., Banister, D., & Bowling, A. (2012). Independence and mobility in later life. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 43(6), 1313–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.04.001

- Schwanen, T., & Lucas, K. (2011). Understanding auto motives. In K. Lucas, E. Blumenberg, & R. Weinberger (Eds.), Auto motives: Understanding car use behaviours (pp. 3–38). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Shergold, I., Lyons, G., & Hubers, C. (2015). Future mobility in an ageing society – where are we heading? Journal of Transport & Health, 2(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.10.005

- Spencer, B., Jones, T., Leyland, L.-A., van Reekum, C. M., & Beale, N. (2019). ‘Instead of “closing down” at our ages … we’re thinking of exciting and challenging things to do’: Older people’s microadventures outdoors on (e-)bikes. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 19(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1558080

- Spinney, J. (2011). A chance to catch a breath: Using mobile video ethnography in cycling research. Mobilities, 6(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2011.552771

- Spinney, J. (2017). Fixing mobility in the neoliberal city: Cycling policy and practice in London as a mode of political-economic and biopolitical governance. Annals of the American Association of Geographer, 106(2), 450–458.

- Stefansdottir, H. (2014). A theoretical perspective on how bicycle commuters might experience aesthetic features of urban space. Journal of Urban Design, 19(4), 496–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2014.923746

- Stehlin, J. (2015). Cycles of investment: Bicycle infrastructure, gentrification, and the restructuring of the San Francisco Bay Area. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(1), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130098p

- Te Brömmelstroet, M., Nikolaeva, A., Cadima, C., Verlinghieri, E., Ferreira, A., Mladenović, M., Milakis, D., de Abreu, E., Silva, J., & Papa, E. (2021). Have a good trip! expanding our concepts of the quality of everyday travelling with flow theory. Applied Mobilities, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2021.1912947

- Tironi, M. (2015). (De)politicising and Ecologising bicycles: The history of the Parisian Vélib’ system and its controversies. Journal of Cultural Economy, 8(2), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2013.838600

- Urry, J. (2004). The ‘system’ of automobility. Theory, Culture & Society, 21(4–5), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046059

- Van Cauwenberg, J., Schepers, P., Deforche, B., & de Geus, B. (2022). Effects of e-biking on older adults’ biking and walking frequencies, health, functionality and life space area: A prospective observational study. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 156, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.12.006

- Van Den Berg, P., Kemperman, A., De Kleijn, B., & Borgers, A. (2016). Ageing and loneliness: The role of mobility and the built environment. Travel Behaviour and Society, 5, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2015.03.001

- Van Der Meulen, J., & Mukhtar-Landgren, D. (2021). Deconstructing accessibility – discursive barriers for increased cycling in Sweden. Mobilities, 16(4), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1902240

- Van Hoof, J., Marston, H. R., Kazak, J. K., & Buffel, T. (2021). Ten Questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Building and Environment, 199, 107922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107922

- Wild, K., Woodward, A., Field, A., & Macmillan, A. (2018). Beyond ‘bikelash’: Engaging with community opposition to cycle lanes. Mobilities, 13(4), 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1408950

- Winters, M., Sims-Gould, J., Franke, T., & McKay, H. (2015). “I grew up on a bike”: Cycling and older adults. Journal of Transport & Health, 2(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.06.001