?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Digital technology can empower citizen journalism as well as state media in authoritarian regimes. China’s propaganda apparatus has undertaken a series of transformations to adapt itself to the changing media environment. This study investigates this adaptive process by drawing on over five million Weibo posts created by 103 newspapers between 2012 and 2019. Results show that through the digital transformation, newspapers are deliberately distancing themselves from their Orwellian past of abstract dogmatism to openly embrace infotainment. A soft-news-centered production model has emerged as the new journalistic paradigm on social media. Not only commercialized outlets but also mouthpiece newspapers produce more soft news than hard news. Regression results further substantiate that soft news is a gateway to propaganda, whose popularity can spill over into propaganda news. For every 100% increase in soft news popularity, propaganda popularity will rise by 38.5% in the following month. News outlets that have garnered attention to soft news can transfer that attention to their subsequent propaganda. These results illuminate how propaganda works in the digital realm, how authoritarian propaganda could be enhanced by infotainment, and why a less political platform could be more susceptible to political intervention.

The Internet has presented both opportunities and challenges for the authoritarian regime in China. The legacy news media, which serve as the central channel for propaganda, faced rapidly diminishing readership since 2013 (Newman Citation2019; Yao Citation2013). Pushed by their survival instinct as well as top-down administrative commands, party media facilitated a far-reaching digital transformation reform to adapt itself to the changing media environment (Wang Citation2021; Wang and Sparks Citation2019; Zou Citation2021).

After years of transformation, the once-gloomy party media has been revitalized. A surprising fact about today’s Chinese digital media system is that a large amount of propaganda news has been consumed, liked, and shared by the general public every day. People’s Daily, the flagship mouthpiece newspaper, has marshalled more than 150 million followers on Sina Weibo and CCTV News has 130 million followers. In stark contrast to their audience in the broadcasting era who tended to dislike and dispute propaganda (Huang Citation2015, Citation2018), a large segment of online audience has been actively engaging with propaganda and helping promulgate official ideology to a wider range of public. For instance, on 1 July 2021, People’s Daily launched a large-scale propaganda campaign on Sina Weibo to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party. The campaign turned out to be a huge success, garnering 6.9 billion views and 18 million postings. With the help of social media, propaganda campaigns have gained unprecedented popularity, seeping into the interstices of people’s daily life.

The rise of propaganda, as well as the resurgence of party media, brings us to an intractable conundrum: How can the propaganda content become so popular in a high-choice media environment? What are the main factors that influence netizens’ decisions to engage with party media? More generally, how does the authoritarian regime gain popular support and uphold its legitimacy through digital transformation?

To answer these questions, we draw on more than five million posts produced by 103 general-interest newspapers on Sina Weibo between 2012 and 2019. This sample exhausts almost all general-interest provincial-level and central-level newspapers having profiles on Sina Weibo, which can representatively reflect the big picture of the field. Based on this data, we classify news posts into three categories – soft news, hard news, and propaganda news – and investigate their impact patterns. According to the negative binomial generalized estimating equation models, we find that the popularity of soft news can spill over to hard news, and the popularity of soft news and hard news can spill over to propaganda news. News outlets that have gained attention for non-propaganda content are able to transfer that attention to propaganda content. Entertainment, in this sense, is a gateway to politics and propaganda. By shedding light on the mechanism of popular propaganda, we hope this study will inform and encourage future discussion on authoritarian resilience and media-party-market tripartite relationship in the digital era.

The Puzzle of Propaganda Effectiveness

Propaganda, by definition, refers to political messages that are designed to persuade citizens of the government’s merits, capacity, and accountability (Brady Citation2002; Carter and Carter Citation2022; Lasswell Citation1927).Footnote1 Propaganda effectiveness is critical to authoritarian resilience. In absence of righteous instruments of direct and indirect democracy, authoritarian regimes rely heavily on propaganda to uphold its legitimacy (Adena et al. Citation2015; A. M. Brady Citation2009; Creemers Citation2017; Wedeen Citation2015). While propaganda has enabled many regimes to cement their political power, it is also a double-edged sword that can erode public trust and trigger backfires (Horz Citation2021; Johnson and Parta Citation2010).

Conceptually, propaganda effectiveness encompasses at least two dimensions: reach (or exposure) and potency. Reach concerns who will see the propagandistic message while potency concerns whether those who see the propagandistic message will accept it. According to Geddes and Zaller’s (Citation1989) exposure-acceptance model, a person’s likelihood of being influenced by propaganda would be a product of his/her likelihood of being exposed to propaganda and that of accepting propaganda conditioned on the exposure.

A large body of literature has investigated propaganda potency and many of them find that propaganda is effective in inducing regime support. For example, Kennedy (Citation2009), Li (Citation2004) and Shen and Guo (Citation2013) report that exposure to state-controlled media is associated with higher regime support and institutional trust in China. Zhu, Lu, and Shi (Citation2013) show that state-controlled Chinese newspapers’ coverage can reduce perceived corruption of state authorities and, more generally, Pan, Shao, and Xu (Citation2022) demonstrate that exposure to propaganda can move respondents closer to policy positions espoused by the regime, regardless of their predispositions. In his seminal work on Syrian politics, Wedeen (Citation2015) asserts that propaganda is more effective than coercion, intimidation, and repression in shoring up regime support and inducing public compliance to the authoritarian government. Furthermore, propaganda is also proved effective in demobilizing contentious actions. By studying 30 autocracies over the globe, Carter and Carter (Citation2021) substantiate that one standard deviation increase in propaganda is associated with a 15% reduction in the odds of protest in the authoritarian context.

To the contrary, some scholars believe that propaganda is incapable of swaying mass beliefs, because of its apparent deviation from reality. Based on Asian Barometer Survey, Andrew Nathan (Citation2020) finds propaganda is unrelated to regime support in autocracies in Asian. In China, Zhao et al. (Citation1994) asserted that propaganda was effective in increasing knowledge but ineffective in affecting attitudes. In Russia, Mickiewicz (Citation2008) argue that unadulterated propaganda is ineffective as viewers are aware of underlying bias, which makes them immune to propaganda influence. In Mali, Bleck and Michelitch (Citation2017) unveil that state-run radio broadcasts had no effect on popular support for the newly installed junta. Furthermore, Chang (Citation2021), Chen and Shi (Citation2001), and Huang (Citation2015, Citation2018) point out that propaganda could even backfire, worsening public opinion of the regime among those who perceive propaganda as preposterous.

Despite these inconclusive results, Chinese authorities have made notable efforts to boost propaganda potency. A widely discussed approach is to soften propaganda content. Propagandists have packaged propaganda message in various pop culture forms, such as comics, folk songs, music videos, soup operas, and memes to accommodate mass audience’s taste (Mattingly and Yao Citation2022; Zou Citation2021). Clickbait content is also commonly used to attract public attention (Lu and Pan Citation2021). Some high-profile mouthpiece newspapers, such as People’s Daily, have managed to restore their hegemony by using sensational and populist narratives repeatedly (Y. Li and Long Citation2017). These endeavors have proved largely fruitful. In line with the persuasive power of the softened political ads that use music and images to elicit emotions (Brader Citation2005), softened propaganda that incorporate entertaining formats, populist frames and participatory elements can convince more people than traditionally dogmatic propaganda.

However, it is worth noting that abovementioned studies on softened propaganda are largely confined to the high-profile news outlets, such as the Big Three (People’s Daily, CCTV, and Xinhua News Agency), which enjoy nationwide influence and ample resources that are not available to most media institutions. Besides, few studies have quantitatively examined the reach of propaganda. The lack of research on propaganda reach was less of an issue before the advancement of the Internet, when broadcast media were predominantly owned by the state. However, the Internet has forcefully overturned such state monopoly. A constellation of alternative media and grassroots opinion leaders emerges, cultivating a high-choice environment where people can easily opt out of state-controlled channels (Ruijgrok Citation2021; Tang and Huhe Citation2014). Propaganda reach is no longer guaranteed. Considering this dramatic shift in the media landscape, a path-aware investigation that examines not only how people support propaganda but also how propaganda comes into their attention is warranted. To complement the existing literature, in this study, we draw on a fuller set of 103 newspapers that have profiles on Sina Weibo, which can better reflect a media sphere constituted by numerous titles of varying capabilities to conduct digital transformation. Based on this dataset, we endeavor to unpack propaganda effectiveness from a more dynamic perspective. We will disentangle how public attention flows into and out of propaganda, examine whether entertainment is a getaway from propaganda or a gateway to propaganda, and verify the power of softened propaganda. In what follows we revisit and expand on discussions pertaining to the relationships between entertainment and politics, which can shed helpful light on the first two points.

Soft News: Getaway or Gateway?

As entertainment content grows exponentially in numbers and popularity, widespread inattention to political content becomes a shared problem confronting media practitioners across the world (Bestvater et al. Citation2022; Dou, Wang, and Zhou Citation2006; Mou, Atkin, and Fu Citation2011; Vergara et al. Citation2021; Zhang and Lin Citation2014). Scholars have hotly debated the causal relationship between the prevalence of soft news and the decline of political content. Some believe that soft news is a getaway for people to escape political content and therefore, the prevalence of entertainment-oriented soft news will undercut the chance that people would engage with hardcore political content (Bestvater et al. Citation2022; Dou, Wang, and Zhou Citation2006; Mitchell, Shearer, and Stocking Citation2021; Mou, Atkin, and Fu Citation2011; Prior Citation2005; Webster Citation1984; Webster and Newton Citation1988). In contrast, others assert that soft news can serve as a gateway that exposes apolitical minds to politics and broadens the reach of political content (Baum Citation2003; Baum and Jamison Citation2006; Bode Citation2017; Bode and Becker Citation2018; A. Chen and Mccabe Citation2022; Xia Citation2022).

Both getaway and gateway hypotheses have found empirical support. As for getaway hypothesis, experimental data suggest that when encountering political content accidentally, people tend to skip them and navigate their attention to entertainment content (Bode, Vraga, and Troller-Renfree Citation2017; Gramlich Citation2021; Vergara et al. Citation2021). The earlier a cue that a post is political, the faster they skip over it and seek “refuge” in entertainment (Bode, Vraga, and Troller-Renfree Citation2017). On the contrary, the gateway hypothesis speaks to studies on media stickiness and viewing inertia. Research has substantiated that many people would read/watch a piece of content only because it appears on the channel that they like (Brosius, Wober, and Weimann Citation1992) or that they just happen to watch (Esteves-Sorenson and Perretti Citation2012; LoSciuto Citation1972; Rust, Kamakura, and Alpert Citation1992). Media stickiness and viewing/tuning inertia increases the chance that people who come for entertainment content will stay for subsequent political content and converts entertainment content into a potent gateway for apolitical audience into the political world. For example, in Russia, Gehlbach (Citation2010) documents that every night a sizeable audience tunes in to “Fabrika Zvyezd,” the Russian version of “American Idol,” and then stays for the political news that follows. Esteves-Sorenson and Perretti (Citation2012) analyze aggregate viewership data of six TV channels in Italy and find that a show’s audience increases by 2-4% with a 10% increase in the viewership of the preceding program. Aware of this pattern, many tv channel managers tend to schedule the “anchor” show at the very beginning of the prime-time period in order to take full advantage of its gateway effect to attract and hold tuning-inertial audience (Rust, Kamakura, and Alpert Citation1992).

To put this into context, if soft news is a getaway from propaganda, the proliferation of soft news will lead to a decline in propaganda’s reach and effectiveness. On the other hand, if soft news is a gateway to propaganda, soft news will extend propaganda reach by captivating amusement-seeking audience to read more of subsequent propaganda, and then boost propaganda effectiveness within the same channel.

Therefore, together with the previous section, we propose to test two potential pathways to popularize propaganda: one by softening propaganda content and the other by softening the gateway to propaganda. These two pathways correspond to propaganda potency and reach, respectively. As for the softening of propaganda content, we will examine whether propaganda with emotion-inducing, multimedia, and participatory elements can gain extra popularity on Sina Weibo, conditional on a set of controls. As for the softening of propaganda gateway, we will examine whether soft news is an effective gateway to propaganda, which can help retain and transfer public attention to propaganda.

Methods

Data

To obtain the newspaper list, we compile all central-level and provincial-level general-interest newspapers from 2014 China Journalism Yearbook (pp. 835–839), which yield 192 newspaper titles. Then, we search for each title in the Weibo search interface and identify 103 accounts existing on there (Supplemental Materials, Table S1). We develop an automatic web crawler using the Selenium package in Python to go through their timelines and collect all posts as well as their engagement metrics between 2012 and 2019, which result in a total of 5,704,852 posts.Footnote2 The data collection was initiated in May and finished in June 2020.

Table 1. Generalized estimating equations predicting monthly popularity of news articles.

Measures

Media Characteristics

Centrali is a dummy variable, equal to one if newspaper i is a central-level title.

Typei denotes the media type of newspaper i with three levels: party daily, evening newspaper, and metro newspaper. Party dailies (mouthpiece newspapers) are directly subordinate to party committees and almost exclusively focus on the party line in their reporting. They are less commercialized in ownership and revenue structure than the other two types of newspapers. Since the marketization reform in the 1980s, most provincial party committees established their second newspapers other than the party dailies, which were typically published in the evening time and collectively referred to as the “evening newspapers.” These evening newspapers produced more human-interest content and were more reactive to market trends than party dailies (G. Chen Citation2018; Gu Citation2004). Later on, pressured by the revenue decline, many party dailies decided to establish their market-oriented subsidiaries (Peng, Li, and Liu Citation2018). To bypass the “one city one evening newspaper” regulation, most of these subsidiaries are strategically named “metro newspapers” (G. Chen Citation2018; Nong, Liu, and Shen Citation2000). Compared with evening newspapers, metro newspapers are subject to less political scrutiny and focus even more on profit-making, which makes them the most commercialized type of newspaper. Among the 103 newspapers studied, 40 are party dailies, 13 are evening newspapers, and 50 are metro newspapers.

Media Influence

Circulationi measures newspaper i’s average circulation (unit: 10 thousand) per issue. Since China Journalism Yearbook only reports the yearly circulation data, we assume the circulation remains constant throughout the year.

Followeri evaluates newspaper i‘s follower number in 2020 (unit: million, Supplemental Materials Table S1).Footnote3

Content Variables

#Countij gauges the total number of posts created by newspaper i in month j, which can vaguely represent the effort newspaper i has put into its online offering on Sina Weibo in that month.

Then, we divide news content into three categories: soft news, hard news, and propaganda news. Despite their widespread use, there is no universally accepted definition of hard news and soft news. As pointed out by Reinemann et al. (Citation2012), this pair of concepts represent a dilemma of collective ambiguity (Giovanni Citation1984): different authors use the same terms, but define them differently. Drawing on 24 comprehensive studies of soft and hard news, Reinemann et al. (Citation2012) figure out five key dimensions implicitly underlying the definitions: topic/theme, focus/framing, style, production, and reception, among which the topic dimension is most commonly used by 83% of the studies. While scholars might dispute over the second dimension, the topic dimension has been a fundamental, viable, and even indispensable dimension for identifying hard and soft news.

Reflecting on the topic dimension, Reinemann et al. (Citation2012) assert the key distinction between hard news and soft news lies in the political relevance. They enumerate three classic hard news topics – foreign politics, domestic politics, and economy/finance – and several soft news topics, such as sports, celebrities, and crime. Relatedly, Patterson (Citation2000) contends that hard news should also include breaking events involving top leaders, policy issues, or significant disruptions. Curran et al. (Citation2010) extend the boundary further to have science also counted as hard news topics. As for soft news, Prior (Citation2003) and Baum (Citation2003) consider talk shows and infotainmentFootnote4 programs as the two major types of soft news while Patterson (Citation2000) argues soft news should include all news that is not hard and cover topics that are entertaining, personal, practical and less time-bound.

In accordance with extant literature, we devise a Support Vector Classifier (SVC) with a linear kernel to classify all posts into eleven topical categories: Politics, Military, Business, Education, Health, Technology, Entertainment, Fashion, Game, Sports, Community (Supplemental Materials, Note S1), based on 65,710 labelled newsflashes. Then, we combine Politics, Business, and Military into a big category of hard news. These three topics are of great political relevance and, in Patterson’s (Citation2000) words, are more institutional and distant to ordinary people, which fit well with the definition of the hard news. The remaining eight categories are bundled under the umbrella label of soft news.

After topic classification, we gauge the numbers of hard news and soft news by newspaper i in month j and store these values as variables #Soft Newsij and #Hard Newsij, respectively.

Propaganda news has been commonly operationalized as positive news about regime-related topics, such as top leaders, guiding ideologies, policies, and government actions (Carter and Carter Citation2021; Huang Citation2018; Lu and Pan Citation2021; Qin, Strömberg, and Wu Citation2018). Among relevant topics, news around the state leader constitutes a particularly promising and parsimonious measurement of propaganda. Chinese journalism has seen a heightened personality cult around Xi Jinping in recent years. Since Xi came into power in 2012, the party’s norm of collective leadership was gradually replaced by a strongman leadership. In February 2016, Xi paid a high-profile visit to the Big Three and gave a hawkish speech, requesting the press to pledge absolute loyalty to the party (Hornby and Clover Citation2016; Wong Citation2016). An enormous media loyalty campaign was launched thereafter, driving media to put extraordinary efforts into building Xi’s charisma to signal their loyalty (Luqiu Citation2016; Repnikova and Fang Citation2018; Shirk Citation2018). The front pages, either of newspapers or of news websites, are dominated by Xi’s every move (Wen Citation2016) and other high-ranking leaders such as Premier Li Keqiang are largely marginalized in media coverage (Jaros and Pan Citation2018). Besides, news articles are repeatedly attributing social achievements to Xi’s leadership and justifying policies by referring to Xi Jinping Thought. A large part of propaganda resource is devoted to this campaign and bureaucratic evaluation hinges heavily upon journalistic performance in propagating Xi news. Therefore, Xi news has become the gravity center of the propaganda sphere, attracting other propaganda news to form connections with it, which makes it particularly promising as a proxy for propaganda. Besides, it is also parsimonious because news coverage about the state leader is hardly negative, exempting us from investigating news valence.

In light of this, we consider Xi news as a prototype of propaganda content. We come up with a variable #Xi Newsij that measures the number of posts mentioning Xi Jinping generated by newspaper i in month j as an indicator of propaganda news.

Xi news accounts for 0.04% of soft news and 4.6% of hard news, respectively. To avoid undesirable confusion between variables, we exclude Xi news from them to form three non-overlap variables, namely soft non-Xi news, hard non-Xi news, and Xi news. Given that Xi news only takes up small portions in both types, its exclusion will not substantially sway the results regarding hard news and soft news. So, for the sake of simplicity, we omit “non-Xi” and refer to them simply as soft news, hard news, and Xi news for short.

#Videoij, #Voteij, #Linkij, #Articleij gauge the numbers of posts with videos, opinion polls, external links, and long articles created by newspaper i in month j, respectively. These four measures are indicative of different forms of content softening. Videos are immersive and emotion-inducing. Votes invite the audience to weigh in on questions, which will make news posts more participatory. Both external links and long articles can give audience more control over whether they want an extended reading of the issue and thereby provide progressive browsing experiences. However, the two are different in that external links are outwards, directing audiences to other websites for more information, while long articles are inwards, allowing audience to read more on the topic without leaving the current website.

Popularityij is the major outcome variable for the analysis of content performance. It measures the numbers of likes, shares, and comments of the posts created by newspaper i in month j.Footnote5 Exploratory factor analysis reveals these three indices are unidimensional, loading onto the same factor (Supplemental Materials, Table S4). Therefore, we sum them up to get the general engagement score of each post and label them as Popularityij.Footnote6

Context Variables

GDP per capitaik represents the year k’s Gross Domestic Product per Capita (unit: thousand) of the province where newspaper i is located. It is a valid proxy for the regional level of affluence. We include this variable in the model to control for financial resourcefulness of newspapers.

Data Analysis

As for content performance, we apply the negative binomial generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a log link. GEEs are chosen because we are using a panel dataset. Variables were repeatedly measured once a month for each newspaper from January 2012 to December 2019. Observations of the same newspaper were correlated, violating the independent and identically distributed assumption of ordinary regression. To adjust for within-subject covariance, we control for random effects of subjects and confine the within-subject covariance structure to be the first-order autoregressive matrix (AR1). By allowing more appropriate covariance structure, GEE can provide more accurate prediction for our longitudinal data than ordinary regression. The mathematical equation of the regression models can be written as follows:

where yj is the popularity of a specific news type (soft news for Model 1, hard news for Model two and xi news for Model 3) in month j. To account for the variation in the total post counts each month, an offset variable, i.e., the log-transformed Countyj, is included. The connotation of Countyj changes in accordance with the dependent variable y. In Model 1, it represents the total number of soft news created by the outlets in mouth j and hard news in Model two and Xi news in Model 3. Softj-1, Hardj-1, and Xij-1 are the cross-lagged terms which represent the popularities of soft, hard, and Xi news in the previous month j-1. Parameters k control the entrance of lagged terms whose value will be 0 if the variable that follows is the lagged dependent variable. That is, k1 is equal to 0 in Model 1 as the dependent variable is soft news popularity, k2 is 0 in Model two and k3 is 0 in Model 3. GEE models are implemented in SPSS.

Results

Content Production

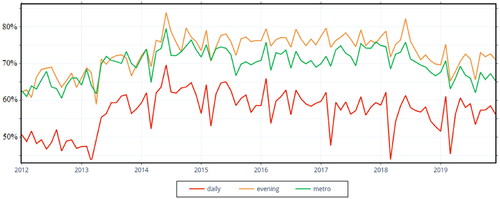

As illustrated by , soft news dominates the newspapers’ online offerings on Sina Weibo. On average, soft news comprises 68% of news content every month. Its domination was enhanced from January 2012 to June 2014 and diminished slowly thereafter. Hard news is also increasing in number; however, in percentage terms, it has sunk from 40% to less than 30% in the first two years and then remained low key in the following years (b).

Figure 1. Time trends of hard news and soft new. Dotted lines represent raw values. Solid lines represent smoothed using a LOWESS approach with a smoother span of 0.1.

further shows that party dailies on average have published lower percentages of soft news (58%) than evening and metro newspapers. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) reveals the between-category percentage differences are significant, F(2, 8210) = 984.51, MSE = .018 (Supplemental Materials, Table S5). As discussed in the Methods section, evening and metro newspapers were designed to be market-oriented and profit-making outlets from the very beginning. Therefore, they are well-positioned and well-motivated to carry on their market-oriented profiles to Weibo.

Moreover, despite their difference in levels, the three trendlines in demonstrate similar temporal patterns over time. They rise and fall at roughly the same pace. Particularly, when they fall, the party dailies tend to fall most heavily. All six lowest points in the trendline of party dailies occur in March, the month of the Two Sessions (People’s Congress and Political Consultative Annual Conference). This suggests that media outlets are subjected to a centralized orchestration, which conforms them to a common rhythm of reporting, and among all newspapers, party dailies are most sensitive to this orchestration.

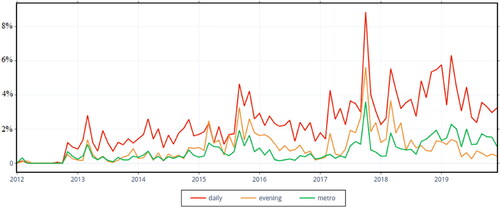

As for propaganda news, party dailies demonstrate a generally rising trend in covering Xi. Xi news reached a peak in October 2017 (), when the nineteenth party congress was held and Xi renewed his term as general secretary of CCP. In Xi’s second term, party dailies expanded their coverage on Xi from 2% in the first term to 4% in the second. Although the number has been doubled, the increment (2%) is not prominent at face value. Between-category differences are also significant. ANOVA test confirms that party dailies and evening newspapers, which are directly subordinate to party committees, produce a substantially higher percentage of Xi news than metro newspapers, F(2, 8209) = 479.95, MSE = .001 (Supplemental Materials, Table S5).

Content Performance

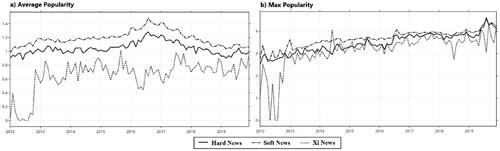

As indicated by , soft news is more popular than hard news while hard news is much more popular than Xi news. On average, soft news attracts 50% and 84% more engagements than hard news and Xi news, respectively, while hard news attracts 23% more engagements than Xi news. However, as can be seen in the right panel of , even though propaganda on average is less popular, it can achieve a similar maximum level of popularity as hard news. The virality potential of propaganda news is on par with that of hard news.

Then we conduct three GEEs to investigate the sources of the popularity of soft, hard, and Xi news in detail. Results are displayed in .Footnote7 Special attention is paid to Model 3, which directly relates to propaganda popularity.

First and foremost, we find that the popularity of non-propaganda news can spill over to propaganda news. According to Models 2 and 3, for every 100% increase in soft news popularity, the popularity of hard news (Model 2, Bsoft = .40, SEsoft = .12, waldsoft = 10.13) and Xi news (Model 3, Bsoft = .47, SEsoft = .05, waldsoft = 92.68) will increase by 7.2% and 38.5% respectively in the following month. Relatedly, a 100% increase in hard news popularity is associated with 32.0% increase in Xi news popularity in the following month (Model 3, Bhard = .10, SEhard = .04, waldhard = 6.04). Therefore, soft news is a gateway to politics and propaganda, which can help retain audience attention and bring out favorable attitudes towards political content in general and propaganda in particular.

Furthermore, there is no discernable “reversed” spillover. An increase in propaganda popularity will not lead to a significant uplift in non-propaganda popularity (Model 1, BXi = −.003, SEXi = .005, waldXi = .33; Model 2, BXi = .01, SEXi = .03, waldXi = .16) and an increase in hard news popularity will not lead to a significant uplift in soft news popularity (Model 1, Bhard = .008, SEhard = .04, waldhard = .03). Popularity can only flow down the ladder of content softness, spilling from the softer to the harder content but not vice versa.

However, in terms of the softened propaganda, we find incorporating emotion-inducing, multimedia and participatory elements will not always make propaganda popular. Hyperlinks and videos can significantly turn people away from propaganda, while votes and long articles do not have statistically significant influence (Model 3, Blink = −.008, SElink = −.001, waldlink = 36.17, Bvideo = −.08, SEvideo = .008, waldvideo = 100.13). In addition to propaganda news, the presence of external links can also undermine the popularity of soft and hard news. Even though adding hyperlinks to news content has become a standard practice in professional digital journalism, it would risk driving traffic away and undermine engagements within the current site.

Besides, adding videos also undercuts propaganda popularity. We investigate videos’ sources and find 73.7% of videos embedded in Xi news are shared from CCTV News, among which a considerable number are clips of Xinwen Lianbo. Xinwen Lianbo is the most well-known television news program in China. It has been broadcasted around the dinner time for more than forty years. Previous studies unveil Xinwen Lianbo to be an emblematic example of coercive propaganda, disliked by the great majority of people (Huang Citation2015, Citation2018). For local outlets that have very few primary sources of state leaders, creating original videos about Xi could be practicably infeasible and politically risky. So, they would prefer reposting videos from high-ranking media, which however might evoke emotional reactance and undermine people’s willingness to engage.

As for the newspaper type, we find that central-level outlets are more capable to garner attention to propaganda news (Model 3, Bcentral = 1.04, SEcentral = .17, waldcentral = 39.3) whilst evening and metro newspapers are more capable to garner attention to soft news (Model 1, Bevening = .55, SEevening = .27, waldevening = 4.1, Bmetro = .45, SEmetro = .22, waldmetro = 4.2). This finding is not surprising. Central-level outlets are closer to the power center and have a unique vantage point to cover top leaders, whilst the commercialized outlets are closer to the market and are more acquainted with the audience’s appetite.

As for pre-existing influence of newspapers, we find the follower count has significantly positive impacts in all three models. In other words, attracting attention is a relatively easier task for news outlets with a broad audience base, no matter what kind of news they work on. Media outlets in more affluent regions are found to have a special edge in popularizing soft news and hard news. However, there is no evidence that they will outperform their less resourceful counterparts in propagating propaganda.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article draws on social media data collected from 103 general-interest Chinese newspapers’ Weibo profiles to examine how they manage to popularize propaganda content and what kinds of impacts would the digital transformation leave on authoritarian resilience.

We find the party media have rejuvenated themselves by boldly embracing the infotainment. On average, 68% of news on Weibo is constituted by soft news. A soft-news-centered production model has emerged as the new journalistic paradigm on social media. With that being said, political intervention is still present. The descriptive time series analysis shows a consistent pattern of news outlets of all kinds publishing less soft news in the month of the Two Sessions.

The regression results further illuminate the depoliticization trend can contribute to the resurgence of party media in two ways. First, soft news is significantly more popular than hard news and hard news is significantly more popular than propaganda news. Content popularity increases as the news is softened. Embracing infotainment is a straightforward way to popularize media profiles.

Second, the popularity of soft news can spill over to hard news while the popularity of soft news and hard news can spill over to propaganda news. For every 100% increase in the popularity of soft news, the propaganda popularity will rise by 38.5% while the hard news popularity will rise by 7.2% in the following month. This suggests that public attention can flow down the ladder of softness, with the human-interest soft news at the top of the ladder, functioning as a gateway to both politics and propaganda. Following the rationale of the byproduct model of information consumption, we can argue that soft news is functioning like a “free lunch” which can whet the audience’s “appetite” and channel the audience’s attention to propaganda (Baum Citation2011; Caraway Citation2011; Fuchs Citation2012; Smythe Citation1981). To popularize propaganda content, newspapers can take the other way around to generate appealing soft news, which can bring out a supportive background for subsequent propaganda to take effect. Embracing infotainment is a low-cost, low-risk and effective approach to popularizing propaganda, which is particularly useful for small titles that lack the acumen to produce appealing propaganda content. Such spillover effect, however, has been regretfully overlooked in previous studies that investigate propaganda and soft news in isolation whilst ignoring the synergy between them.

Besides, contrary to the popular belief about the power of soft propaganda, we find the softened propaganda is not always effective in escalating propaganda effectiveness. While the inclusion of votes and long articles does not have discernable impacts, including hyperlinks and videos to a propagandistic post can even undermine its popularity. In other words, implementing emotion-inducing, participatory, and multimedia features will not guarantee a higher level of popularity for propaganda. The ineffectiveness of softened propaganda can be partly attributed to the fact that most outlets do not have the sources and clearances to innovate the propaganda around the top leader. The softening of propaganda content has been minimized among these small titles. Those widely studied, successful soft propaganda stories are mostly generated by a few high-profile outlets, such as the Big There (Cadell Citation2019; Creemers Citation2017; Y. Li and Long Citation2017; Mattingly and Yao Citation2022; Repnikova and Fang Citation2018, Citation2019; Zou Citation2021). This small number of outliers have overshadowed the majority of less competent outlets in previous studies, impeding us from seeing the less cheerful side of the softened propaganda.

In summary, this article demonstrates a story about “less is more” – a less political platform is more susceptible to political intervention and diluting propaganda with soft news in turn can improve propaganda effectiveness. Through the digital transformation, newspapers are deliberately distancing themselves from their Orwellian past of abstract dogmatism to embrace what Huxley envisioned in Brave New world – a sugar-coated consumerist seduction, which controls public minds by “inflicting pleasure” and satisfying people’s need for recreation. For example, People’s Daily has been publishing one emotionally enlightening article every day under the big title “Bedtime Reading” on Weibo. These batches of human-interest content are devoid of propaganda in text yet are instrumental to propaganda in effect, as our research shows. Party media can leverage infotainment to amass politically apathetic audience. With a larger audience in camp and with popular non-propaganda served as the “free lunch,” they could deliver ideological messages more effectively.

Some limitations are worth noting when reading this article. First, it is important to note that our approach to identifying hard and soft news is admittedly simplistic. It solely concentrates on the topic dimension, while leaving out the news focus/frame and style dimensions. Actually, a news story about fashion industry can be hard if it adopts thematic frames and a news story about domestic politics can also be soft if it is written in a highly sensational style. As pointed out by Baum (Citation2002), the difference between soft and hard news is one of degree rather than kind. Dichotomizing news into soft and hard can undermine granularity in analysis. In this study, we trade in granularity for generalizability. As discussed earlier, the topic-based classification is the most efficient way to distinguish hard news from soft news in a large sample. Automatic topic detection is our optimal but not perfect solution. There is a growing body of literature introducing new tools to automatically identify news frames (Guo et al. Citation2022; Lind et al. Citation2019; Walter and Ophir Citation2019). We strongly encourage future research to apply these emerging techniques to integrate focus/frame and style dimensions into analysis.

Second, we also admit Xi news as an indicator of propaganda is also simplistic. It does not cover other propagandistic topics such as government actions, achievements, and policies. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that according to our operationalization criterion, Xi news includes not only news that features Xi but also news where Xi himself is absent, yet his name is cited, and his ideology is reiterated. For instance, news that attributes an achievement to Xi Jinping Thought or that characterizes a cheerful event as Xi Jinping’s New Era is also counted as Xi news, even though Xi is not the major subject of the news. As elaborated in the Methods section, the personality cult around Xi is forcefully connecting, if not converting, other propaganda news to Xi news and rendering the popularity of Xi news a critical determinant of propagandists’ career and government subsidy (Repnikova and Fang Citation2019; Wang and Sparks Citation2019). Therefore, Xi news, despite being limited in scope, can provide valuable insights into the core of propaganda campaign.

Third, we did not rule out the confounding influence of platform algorithms or automatic bots, which might falsely boost engagements of some posts or accounts (Han Citation2015; King, Pan, and Roberts Citation2017). Last but not least, although the current newspaper sample has exhausted all influential titles across the country, we did not include television news channels into our investigation. Therefore, we regretfully missed CCTV in our study, which is a well-known case of party media resurgence. Further research should endeavor to investigate a broader list of news outlets.

Party_Media_in_the_Social_Media_Era_Supplemental_Materials.docx

Download MS Word (105.1 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Although propaganda exists in almost all societies and has surged back into popular consciousness in western countries since the 2016 US Presidential Election, its mechanism and social implications vary across countries. In the western context, propaganda is widely perceived as negative and malicious. However, in China, as David (Shambaugh Citation2007) put it, propaganda is accepted as a legitimate tool for building the kind of ideal society sought by the party. It does not necessarily carry the negative connotation as it does in the western countries. In this study, we opt to use the term “propaganda,” but we urge caution and neutrality in interpreting this term. We argue propaganda could be thought of as a legitimation device or as a state-run political advertising initiative. While commercial advertisements try to persuade people into buying products, propaganda tries to persuade people into supporting the regime and its political agenda. As illustrated by previous studies (A.-M. Brady Citation2002; Carter and Carter Citation2021), propaganda shares many commonalities with political advertisements, in terms of effect size, half-life, and principles. Chinese propagandists were also said to be influenced by American public relations work to modernize its propaganda system (A.-M. Brady Citation2002). Based on this conception, we aim to investigate how propaganda is conducted and how it can gain popular support in the digital realm in contemporary China. The results obtained here can also have implications for understanding political advertisements in democratic context.

2 Since the data is collected in a post-hoc manner, a key concern here is how complete the data is and whether posts of interest have been deleted by censorship apparatus. To address this concern, we consult Weiboscope, a data archive which has recorded a part of the censored posts on Weibo. We find 86 out of the 103 newspapers that we study in this research have been tracked by Weiboscope and only 0.06% of their posts are censored. In line with our finding, Zhu and Fu (Citation2021) have also found that media accounts are more vocal in covering issues about 2019 Hong Kong protests yet subjected to less censorship than non-media accounts. That is to say, as we focus solely on established mainstream media, the influence of censorship should be minimal.

3 In doing this, we impute outlets’ follower numbers in 2020 to all observations. To examine whether this imputation will bias our results, we consult the Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org), a large-scale database that archives digital copies of 588 billion webpages and their historical versions. We manually check each outlet’s profile page in Wayback Machine and take down their follower numbers between 2013 and 2018 (Follower numbers were not displayed on homepages in 2012. So, the year of 2012 is not included in this test). We extract only one follower number per year. It is worth noting that the Wayback Machine does not have a fixed schedule for updating the database. Based on our observation, the most frequent update date is 24 October. So, to control for within-year variation, we chose to pick the dates closest to 24 October. A total of 347 data points were recorded (Supplemental Materials Table S2). Then we calculated the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between Follower2020 and the follower numbers in other years and found they are highly correlated (r2018 = 0.98, r2017 = 0.94, r2016 = 0.94, r2015 = 0.95, r2014 = 0.95, r2013 = 0.88). So, we argue the Follower2020 could serve as valid imputation values as it can capture news outlets’ relative sizes of audience to a large degree.

4 As the news production has been increasingly driven by the consideration of popular taste, news and entertainment have grown deeply inseparable, giving rise to the admixture of infotainment – a blend of “information” and “entertainment” (Delli Carpini and Williams Citation2001; Moy, Xenos, and Hess Citation2005). Some scholars consider infotainment a subtype of soft news that focuses on the entertainment industry (Baum Citation2003; Prior Citation2003) while the others consider infotainment a synonym for soft news or any news that contains considerable entertainment value (Reinemann et al. Citation2012). In this study, we avoid using infotainment as a content type. Instead, we stick to the classification of soft, hard, and propaganda news, which is clearer with less overlap between the categories, and regard infotainment as an aesthetic way to describe the permeability of form and the obscuring of traditional boundaries between entertainment and political content.

5 According to a recent study by Wang and Zhu, Citation2021, most information dies out very soon on Weibo, especially for the daily news stories. The average length of the diffusion lifetime of posts is 8.78 days, and the median lifetime is only 2 days. Since we collected the data in May and June 2020, at least five months after the publication of posts, the engagement metrics should be mostly stable and saturated. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for the extremely useful comment on this point.

6 We argue the engagement metric is a valid measure of popularity. Due to the length limit, we save the detailed justification in Supplemental Materials Note S2.

7 To assure the results are robust to different model specifications, we take an extra step to run a linear GEE where the dependent variables are changed to the log-transformed average popularity of news content. Because the values of the monthly total engagement metrics are very large and zeros are very rare in our data set, the negative binomial distribution with a large mean count can be approximated by a gaussian distribution. The robustness check affirms the results demonstrated in Table 2 are robust and the findings we derive here are not driven by particular modeling assumptions about the data distribution (Supplemental Materials Table S6).

References

- Adena, Maja, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. 2015. “Radio and the Rise of Nazis in Prewar Germany.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130 (4): 1885–1939.

- Baum, Matthew A. 2002. “Sex, Lies, and War: How Soft News Brings Foreign Policy to the Inattentive Public.” American Political Science Review 96 (1): 91–109.

- Baum, Matthew A. 2003. “Soft News and Political Knowledge: Evidence of Absence or Absence of Evidence?” Political Communication 20 (2): 173–190.

- Baum, Matthew A. 2011. Soft News Goes to War: Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy in the New Media Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Baum, Matthew A., and Angela S. Jamison. 2006. “The Oprah Effect: How Soft News Helps Inattentive Citizens Vote Consistently.” Journal of Democracy 68 (4): 946–959.

- Bestvater, Sam, Sono Shah, Gonzalo River, and Aaron Smith. 2022. Politics on Twitter: One-Third of Tweets From U.S. Adults Are Political. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/06/16/politics-on-twitter-one-third-of-tweets-from-u-s-adults-are-political/?utm_source=Pew+Research+Center&utm_campaign=8f16fa8e0e-METHODS_2022_07_19&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_3e953b9b70-8f16fa8e0e-400416669.

- Bleck, Jaimie, and Kristin Michelitch. 2017. “Capturing the Airwaves, Capturing the Nation? A Field Experiment on State-Run Media Effects in the Wake of a Coup.” The Journal of Politics 79 (3): 873–889.

- Bode, Leticia. 2017. “Gateway Political Behaviors: The Frequency and Consequences of Low-Cost Political Engagement on Social Media.” Social Media + Society 3 (4): 205630511774334.

- Bode, Leticia, and Amy B. Becker. 2018. “Go Fix It: Comedy as an Agent of Political Activation.” Social Science Quarterly 99 (5): 1572–1584.

- Bode, Leticia, Emily K. Vraga, and Sonya Troller-Renfree. 2017. “Skipping Politics: Measuring Avoidance of Political Content in Social Media.” Research & Politics 4 (2): 205316801770299.

- Brader, Ted. 2005. “Striking a Responsive Chord: How Political Ads Motivate and Persuade Voters by Appealing to Emotions.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (2): 388–405.

- Brady, Anne-Marie. 2002. “Regimenting the Public Mind: The Modernization of Propaganda in the PRC.” International Journal 57 (4): 563–578.

- Brady, Anne Marie. 2009. “Mass Persuasion as a Means of Legitimation and China’s Popular Authoritarianism.” American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 434–457.

- Brosius, Hans-bernd, Mallory Wober, and Gabriel Weimann. 1992. “The Loyalty of Television Viewing: How Consistent is TV Viewing Behavior?” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 36 (3): 321–335.

- Cadell, Cate. 2019. “Propaganda 2.0 - Chinese Communist Party’s Message Gets Tech Upgrade.” Reuters.

- Caraway, Brett. 2011. “Audience Labor in the New Media Environment: A Marxian Revisiting of the Audience Commodity.” Media, Culture and Society 33 (5): 693–708.

- Carter, Erin Baggott, and Brett L. Carter. 2021. “Propaganda and Protest in Autocracies.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65 (5): 919–949.

- Carter, Erin Baggott, and Brett L. Carter. 2022. “When Autocrats Threaten Citizens with Violence : Evidence from China.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (2): 671–696.

- Chang, Charles. 2021. “Information Credibility under Authoritarian Rule: Evidence from China.” Political Communication 38 (6): 793–813.

- Chen, Amanda, and Katherine T. Mccabe. 2022. “Roses and Thorns: Political Talk in Reality TV Subreddits.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/14614448221099180.

- Chen, Guoquan. 2018. “40 Years of Metro Newspapers: Transformation and Future.” Youth Journalist 25: 9–12.

- Chen, Xueyi, and Tianjian Shi. 2001. “Media Effects on Political Confidence and Trust in the People’s Republic Of China in the Post-Tiananmen Period.” East Asia 19 (3): 84–118.

- Creemers, Rogier. 2017. “Cyber China: Upgrading Propaganda, Public Opinion Work and Social Management for the Twenty-First Century.” Journal of Contemporary China 26 (103): 85–100.

- Curran, James, Inka Salovaara-Moring, Sharon Coen, and Shanto Iyengar. 2010. “Crime, Foreigners and Hard News: A Cross-National Comparison of Reporting and Public Perception.” Journalism 11 (1): 3–19.

- Delli Carpini, X. Michael, and Bruce A. Williams. 2001. “Let Us Infotain You: Politics in the New Media Age.” In Mediated Politics: Communication in the Future of Democracy, edited by W. Lance Bennett and Robert M. Entman, 160–181. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Dou, Wenyu, Guangping Wang, and Nan Zhou. 2006. “Generational and Regional Differences in Media Consumption Patterns of Chinese Generation X Consumers.” Journal of Advertising 35 (2): 101–110.

- Esteves-Sorenson, Constanca, and Fabrizio Perretti. 2012. “Micro-Costs: Inertia in Television Viewing.” The Economic Journal 122 (563): 867–902.

- Fuchs, Christian. 2012. “Dallas Smythe Today - The Audience Commodity, the Digital Labour Debate, Marxist Political Economy and Critical Theory. Prolegomena to a Digital Labour Theory of Value.” tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 10 (2): 692–740.

- Geddes, Barbara, and John Zaller. 1989. “Sources of Popular Support for Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 33 (2): 319–347. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2111150.

- Gehlbach, Scott. 2010. “Reflections on Putin and the Media.” Post-Soviet Affairs 26 (1): 77–87.

- Giovanni, Sartori. 1984. “Guidelines for Concept Analysis.” In Social Science Concepts: A Systematic Analysis, edited by Sartori Giovanni, 15–85. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

- Gramlich, John. 2021. 10 Facts about Americans and Facebook. pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/01/facts-about-americans-and-facebook/.

- Gu, Long. 2004. “Ten Points about the Development of Chinese Evening Newspapers.” News Reporters 10: 5–8.

- Guo, Lei, Chao Su, Sejin Paik, Vibhu Bhatia, Vidya Prasad Akavoor, Ge Gao, Margrit Betke, et al. 2022. “Proposing an Open-Sourced Tool for Computational Framing Analysis of Multilingual Data.” Digital Journalism. doi:10.1080/21670811.2022.2031241.

- Han, Rongbin. 2015. “Manufacturing Consent in Cyberspace: China’s ‘Fifty-Cent Army’.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 44 (2): 105–134.

- Hornby, Lucy, and Charles Clover. 2016. “China Media: Pressed into Service.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/cbaa9db6-f7ec-11e5-96db-fc683b5e52db.

- Horz, Carlo M. 2021. “Propaganda and Skepticism.” American Journal of Political Science 65 (3): 717–732.

- Huang, Haifeng. 2015. “Propaganda as Signaling.” Comparative Politics 47 (4): 419–437.

- Huang, Haifeng. 2018. “The Pathology of Hard Propaganda.” The Journal of Politics 80 (3): 1034–1038.

- Jaros, Kyle, and Jennifer Pan. 2018. “China’s Newsmakers: Official Media Coverage and Political Shifts in the Xi Jinping Era.” The China Quarterly 233 (December 2017): 111–136.

- Johnson, A. Ross, and R. Eugene Parta. 2010. Cold War Broadcasting: Impact on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press.

- Kennedy, John James. 2009. “Maintaining Popular Support for the Chinese Communist Party: The Influence of Education and the State-Controlled Media.” Political Studies 57 (3): 517–536.

- King, Gary, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts. 2017. “How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument.” American Political Science Review 111 (3): 484–501. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0003055417000144/type/journal_article.

- Lasswell, Harold D. 1927. “The Theory of Political Propaganda.” American Political Science Review 21 (3): 627–631.

- Li, Lianjiang. 2004. “Political Trust in Rural China.” Modern China 30 (2): 228–258.

- Li, Yanhong, and Qiang Long. 2017. “Reconstructing Hegemony in the Context of New Media: The Weibo account of People’s Daily and Its Communicational Adaptation (2012–2014).” Communication & Society 39: 157–187.

- Lind, Fabienne, Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Tobias Heidenreich, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2019. “Computational Communication Science| When the Journey is as Important as the Goal: A Roadmap to Multilingual Dictionary Construction.” International Journal of Communication 13: 21.

- LoSciuto, Leonard A. 1972. “A National Inventory of Television Viewing Behavior.” In Television and Social Behavior. Television in Day-to-Day Life: Patterns of Use, edited by Eli A. Rubinstein, George A. Comstock, and John P. Murray, 33–86. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Lu, Yingdan, and Jennifer Pan. 2021. “Capturing Clicks: How the Chinese Government Uses Clickbait to Compete for Visibility.” Political Communication 38 (1–2): 23–54.

- Luqiu, Luwei Rose. 2016. “The Reappearance of the Cult of Personality in China.” East Asia 33 (4): 289–307.

- Mattingly, Daniel C., and Elaine Yao. 2022. “How Soft Propaganda Persuades.” Comparative Political Studies 55 (9): 1569–1594.

- Mickiewicz, Ellen Propper. 2008. 3 Television, Power, and the Public in Russia. Cambridge: University Press Cambridge.

- Mitchell, Amy, Elisa Shearer, and Galen Stocking. 2021. News on Twitter: Consumed by Most Users and Trusted by Many. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/11/15/news-on-twitter-consumed-by-most-users-and-trusted-by-many/.

- Mou, Yi, David Atkin, and Hanlong Fu. 2011. “Predicting Political Discussion in a Censored Virtual Environment.” Political Communication 28 (3): 341–356. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10584609.2011.572466.

- Moy, Patricia, Michael A. Xenos, and Verena K. Hess. 2005. “Communication and Citizenship: Mapping the Political Effects of Infotainment.” Mass Communication and Society 8 (2): 111–131.

- Nathan, Andrew J. 2020. “The Puzzle of Authoritarian Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy 31 (1): 158–168.

- Newman, Nic. 2019. 2019 Digital News Report. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2019/overview-key-findings-2019/.

- Nong, Qiubei, Tingting Liu, and Yibin Shen. 2000. “Investigation Report on Metro Newspapers.” In China Journalism Yearbook, 262–264. Beijing, China: China Journalism Yearbook Publishing House.

- Pan, Jennifer, Zijie Shao, and Yiqing Xu. 2022. “How Government-Controlled Media Shifts Policy Attitudes through Framing.” Political Science Research and Methods 10 (2): 317–332.

- Patterson, Thomas E. 2000. SSRN Doing Well and Doing Good.

- Peng, Jian, Hui Li, and Wenshuai Liu. 2018. “Revolution and Transformation of Metro Newspapers.” In 40 Years of Chinese News Industry, 48. Beijing, China: People’s Publishing House.

- Prior, Markus. 2003. “Any Good News in Soft News? The Impact of Soft News Preference on Political Knowledge.” Political Communication 20 (2): 149–171.

- Prior, Markus. 2005. “News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political Knowledge and Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 577–592.

- Qin, Bei, David Strömberg, and Yanhui Wu. 2018. “Media Bias in China.” American Economic Review 108 (9): 2442–2476. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/aer.20170947.

- Reinemann, Carsten, James Stanyer, Sebastian Scherr, and Guido Legnante. 2012. “Hard and Soft News: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Findings.” Journalism 13 (2): 221–239.

- Repnikova, Maria, and Kecheng Fang. 2018. “Authoritarian Participatory Persuasion 2.0: Netizens as Thought Work Collaborators in China.” Journal of Contemporary China 27 (113): 763–779.

- Repnikova, Maria, and Kecheng Fang. 2019. “Digital Media Experiments in China: Revolutionizing Persuasion under Xi Jinping.” The China Quarterly 239 (May): 679–701.

- Ruijgrok, Kris. 2021. “Illusion of Control: How Internet Use Generates anti-Regime Sentiment in Authoritarian Regimes Sentiment in Authoritarian Regimes.” Contemporary Politics 27 (3): 247–270.

- Rust, Roland T., Wagner A. Kamakura, and Mark I. Alpert. 1992. “Viewer Preference Segmentation and Viewing Choice Models for Network Television.” Journal of Advertising 21 (1): 1–18.

- Shambaugh, David. 2007. “China's Propaganda System: Institutions, Processes and Efficacy.” The China Journal 57 (January): 25–58.

- Shen, Fei, and Zhongshi Steve Guo. 2013. “The Last Refuge of Media Persuasion: News Use, National Pride and Political Trust in China.” Asian Journal of Communication 23 (2): 135–151.

- Shirk, Susan L. 2018. “China in Xi’s ‘New Era’: The Return to Personalistic Rule.” Journal of Democracy 29 (2): 22–36.

- Smythe, Dallas W. 1981. “On the Audience Commodity and Its Work.” In Dependence Road: Communications, Capitalism, Conciousness, and Canada, 22–51. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

- Tang, Min, and Narisong Huhe. 2014. “Alternative Framing: The Effect of the Internet on Political Support in Authoritarian China.” International Political Science Review 35 (5): 559–576.

- Vergara, Adrián, Ignacio Siles, Ana Claudia Castro, and Alonso Chaves. 2021. “The Mechanisms of ‘Incidental News Consumption’: An Eye Tracking Study of News Interaction on Facebook.” Digital Journalism 9 (2): 215–234.

- Walter, Dror, and Yotam Ophir. 2019. “News Frame Analysis: An Inductive Mixed-Method Computational Approach.” Communication Methods and Measures 13 (4): 248–266.

- Wang, Cheng-Jun, and Jonathan J. H. Zhu. 2021. “Jumping over the Network Threshold of Information Diffusion: testing the Threshold Hypothesis of Social Influence.” Internet Research 31 (5): 1677–1694. doi:10.1108/INTR-08-2019-0313.

- Wang, Haiyan. 2021. “Generational Change in Chinese Journalism: Developing Mannheim’s Theory of Generations for Contemporary Social Conditions.” Journal of Communication 71 (1): 104–128.

- Wang, Haiyan, and Colin Sparks. 2019. “Chinese Newspaper Groups in the Digital Era: The Resurgence of the Party Press.” Journal of Communication 69 (1): 94–119.

- Webster, James G. 1984. “Cable Television’s Impact on Audience for Local News.” Journalism Quarterly 61 (2): 419–422.

- Webster, James G., and Gregory D. Newton. 1988. “Structural Determinants of the Television News Audience.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 32 (4): 381–389.

- Wedeen, Lisa. 2015. Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wen, Philip. 2016. “China’s Great Leap Backwards: Xi Jinping and the Cult of Mao.” Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/world/chinas-great-leap-backwards-xi-jinping-and-the-cult-of-mao-20160512-gotfiz.html.

- Wong, Edward. 2016. “Xi Jinping’s News Alert: Chinese Media Must Serve the Party.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/23/world/asia/china-media-policy-xi-jinping.html.

- Xia, Shouzhi. 2022. “Amusing Ourselves to Loyalty? Entertainment, Propaganda, and Regime Resilience in China.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (4): 1096–1112.

- Yao, L. 2013. “An Analysis of 2012 China Newspaper Advertising Market.” In Blue Book of China’s Media, edited by B. G. Cui, 82–91. Beijing, China: Social Sciences Publishing.

- Zhang, Xinzhi, and Wan-ying Lin. 2014. “Political Participation in an Unlikely Place: How Individuals Engage in Politics through Social Networking Sites in China.” International Journal of Communication 8: 21–42.

- Zhao, Xinshu, Jian-hua Zhu, Hairong Li, and Glen L. Bleske. 1994. “Media Effects under a Monopoly: The Case of Beijing in Economic Reform.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 6 (2): 95–117.

- Zhu, Yuner, and King-wa Fu. 2021. “Speaking up or Staying Silent? Examining the Influences of Censorship and Behavioral Contagion on Opinion (non-) Expression in China.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3634–3655. doi:10.1177/1461444820959016.

- Zhu, Jiangnan, Jie Lu, and Tianjian Shi. 2013. “When Grapevine News Meets Mass Media: Different Information Sources and Popular Perceptions of Government Corruption in Mainland China.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (8): 920–946.

- Zou, Sheng. 2021. “Restyling Propaganda: Popularized Party Press and the Making of Soft Propaganda in China.” Information Communication and Society. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2021.1942954.