?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The increasing mediatization of war makes battles over public image evermore prominent. Individual citizens, no longer mediated by traditional gatekeepers, engage in public diplomacy and citizen-journalism, communicating directly to the public. TikTok, a visual social media platform, was used extensively by Palestinians and Israelis to mobilize international support during the 2021 round of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This paper examines appeals that Israeli and Palestinian TikTok users made to international audiences by comparing 318 posts sampled from two rhetorically equivalent hashtags. A content analysis examining the strategies used, found that each side emphasized different themes (e.g., victimization on the Israeli side, personal narratives on the Palestinian side). Although pro-Israeli users were more strategic in their use of the platform’s features, a multi-variate analysis of engagement found that pro-Palestinian activists were more successful in creating engagement. To further understand the complex and subtle meaning structures encoded into the posts, a subsample of 42 highly shared posts was probed qualitatively for its aesthetics and values, using a semiotic analysis. A first study to compare public diplomacy efforts on TikTok across parties, this paper contributes to knowledge about the ways citizens bear witness from warzones, use platform affordance for storytelling, and engage with the international community.

The phrase “image war” denotes a battle over reputation. In modern warfare, battle over public image is waged alongside military confrontation as political actors seek international support. The phrase also reflects the use of images as instruments of war. Modern warfare and images go hand in hand. As Ernst Jünger observed in 1930, war-making and picture-taking (both involving “shooting” a subject) are congruent activities: “It is the same intelligence, whose weapons of annihilation can locate the enemy to the exact second and meter,” wrote Jünger, “that labors to preserve the great historical event in fine detail” (Jünger, 1930, quoted in Sontag Citation2004). Images have been used to glorify war through depictions of dignity and brotherhood, and to denounce it through depictions of atrocity and tragedy (Sontag Citation2004). Finally, images battle one another for survival in public memory. Most consign to oblivion, some make a temporary impression, fewer become iconic and/or mimetic (e.g., Boudana, Frosh, and Cohen Citation2017; Peters and Allan Citation2022).

All these meanings are on display in wartime civic diplomacy waged on social media. Civic diplomacy is a grassroot attempt to influence international public opinion through personal social network platforms (Anton Citation2022; Cull Citation2021; Yi et al. Citation2015). Civic diplomacy is a form of digital activism (Kaun and Uldam Citation2018); it’s utilization in times of war highlights diplomatic characteristics. While the relationship between war and photography is long standing, little is known about the intersection between civic diplomacy and contemporary practices of audio-visual creativity (e.g., curating, explicating, and remixing images). Moreover, while a growing body of research has been examining civic diplomacy social media (e.g., Anton Citation2022; Yarchi, Samuel-Azran, and Bar-David Citation2017; Yi et al. Citation2015), there are no comparisons of civic diplomacy from opposing sides of a conflict.

Drawing on political communication, visual culture, and social media studies, we address these gaps by examining how pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian TikTok posts appealed to an international audience during the 2021 Israeli-Palestinian war. Posts were pulled from #Gazaunderattack and #Israelunderattack, two popular, opposing, yet rhetorically equivalent hashtags used during the war. Using a combination of quantitative content analysis (n = 318) and qualitative semiotic analysis (n = 42), we examined message strategies used by TikTok users, as well as the semiotic resources they employed within and beyond persuasive messages. We found several differences in messaging between pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian posts and a clear gap in their popularity rates. Findings also suggest that TikTok’s image war diverges from previous literature about civic diplomacy on other social media platforms. A minority of posts followed formulaic conflict frames, or attempted persuasion at all. We chart five practices of civic diplomacy on TikTok, marked by different meta-communicative values and genres of expression. By shedding light on the success, values, and aesthetics of TikTok posts circulated during a war with high international visibility, this paper provides a foundation to further analyze and explain contemporary dynamics of wartime communication on visually condensed social media platforms.

The war over Public Image: From State Actors to Civic Diplomacy

The battle over public image is an important front in twenty first century warfare (Esser Citation2009; Hoskins and O’Loughlin Citation2010). Antagonists increasingly fight to promote their narrative, justify their actions, and gain public support (Ayalon, Popovich, and Yarchi Citation2016; van Evera Citation2006). Political actors consider public image when they wage war and perceive it as crucial to achieve their goals (van Evera Citation2006; Yarchi and Ayalon Citation2023).

The image war can reverse material power dynamics (Rabasa Citation2011; Roger Citation2013). In asymmetric conflicts, a weaker power militarily often gains a symbolic advantage in media coverage. Western media tend to empathize with underdogs through a narrative of compassion (Altheide Citation1997; Wolfsfeld and Yarchi Citation2015). Stories of victimization have powerful effects on audience empathy and support for the victimized (Knightley Citation2004), especially when they include visual images, due to their strong affective appeal and sense of realness (Hoskins and O’Loughlin Citation2010; O’Loughlin Citation2011). Such effects translate to international support, from sympathetic public opinion to formal resolutions and sanctions (Wolfsfeld Citation2022; Yarchi and Ayalon Citation2023). Image considerations can dissuade powerful actors from using their military capabilities (Roger Citation2013).

Political actors invest significant resources in mainstream and in social media platforms to inform citizens and to promote their narrative to a global public (Heemsbergen and Lindgren Citation2014; Samuel-Azran and Yarchi Citation2018; Stein Citation2021). Studies examining messages circulated on both traditional and social media in times of conflict (e.g., Yarchi Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2022; Yarchi, Samuel-Azran and Bar-David Citation2017), suggest similarities in the ways that political actors – whether countries (e.g., The United States, the United Kingdom and Israel) or non-state actors (e.g., Al-Qaida, ISIS, Hamas and Hezbollah) – promote their narrative. Political actors seek to increase the legitimacy of their side, while delegitimizing the opponent. They tend to present themselves as the victim, to place the blame on the other side, and to prescribe a course of action – in line with Entman’s (Citation1993) definition of frames as organizing information in terms of a problem, cause, and solution.

The affordances and popularity of social media make war more interactive, individualized, immediate, and intimate than ever (Pötzsch Citation2015). Some individual citizens turn to social media to partake in civic diplomacy: the attempt of individuals, rather than organs of state, to influence international public opinion in favor of a cause (Anton Citation2022; Yi et al. Citation2015). Citizens often voluntarily advocate for policies or actions that support state interests (Cull Citation2021; Sharp Citation2001). For example, in a study that explored “Israel Under Fire”, a civic initiative that promoted a pro-Israeli narrative on Facebook during the 2012 and 2014 rounds of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Yarchi, Samuel-Azran and Bar-David (Citation2017), identified four argumentation strategies (1) Israel’s right to defend itself (2) “What would YOU do?” – encouraging international audiences to place themselves in Israeli shoes, (3) “Hamas propaganda” – unpacking the veracity of claims made by Hamas; and (4) “Free Gaza from Hamas” – promoting a solution that removes Hamas from the equation. Similarly, Ukrainian citizens appealing to international audiences on Facebook and Twitter during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine emphasized their victimization and suffering, placed the blame on the Russians, and urged the international community to intervene. These civic diplomacy initiatives resemble the official messages of their governments and follow the formulaic problem, cause, and solution frames (Yarchi Citation2022). The rise of social media platforms emphasizing audio-visual and mimetic communication necessitates a re-examination of this similarity between official and civic actors.

Images at War: Old Conflicts, New Genres of Expression

The use of social media in the context of conflict goes hand in hand with global networking culture and its distinct grammars, aesthetics, structures of feeling, and consumer engagement (Kuntsman and Stein Citation2015). Though social media present a seemingly chaotic mass of material, textual and audience analyses suggest that user generated content is patterned by repeating genres and rituals of expression (Hallinan, Kim, Scharlach, Trillò, Mizoroki, and Shifman Citation2023; Trillò, Hallinan, and Shifman Citation2022).

Genres are types of cultural expression, recognized as such by creator and audience, which share elements of form, content, and interpretative expectations (Hallinan et al. Citation2023). For example, internet memes are a quintessential social media genre. A meme is a group of digital items with common characteristics that are created with awareness of each other, then circulated, imitated, and/or transformed by internet users (Shifman Citation2013). A form of “pop-savvy mediation” of public sphere issues (Milner Citation2013) and a weapon in public debate about politics (Peters and Allan Citation2022), memes are increasingly used in conflict by ordinary citizens to promote national narrative and identities (Asmolov Citation2021; Kuntsman and Stein Citation2015). For example, Wiggins’s (Citation2016) analysis of memes circulated on Twitter throughout the 2014 Russia-Ukraine war, found that both sides drew visual references to American popular culture, typically using macro-images (repeating photo/s with changing witty captions), to satirize local leadership.

Genres are the building blocks of media rituals, namely, typified communicative practices on social media that formalize and express shared values (Trillò et al. 2023). Trillò et al. identified 16 social media rituals, each consisting of various genres. For example, celebrity death tweets (#RIP) and Facebook memorial pages are iconic genres within the broader ritual of commemoration, which marks the passage of time and indicates that something/someone should be remembered. User generated renditions of the iconic “Accidental Napalm” image commemorated and honored Vietnam war victims. However, in its afterlife, this 50-year-old image was also subjected to shocking juxtapositions that trivialized and distorted its anti-war message (Boudana et al. Citation2017).

Social media rituals are demarcated by core values that highlight a worthy action/attribute (e.g., “loyalty” and “respect” in commemoration rituals), and meta-communicative values that convey a perception about what communication ought to serve (e.g., to form affiliation in commemoration rituals). While this typology does not address content generated by users in the context of war, it does include various rituals, like commemoration, promotion (seeking to elevate the status of something), demotion (seeking to lower the status of something) and requesting (asking for aid or support) that are pertinent to documented practices of civic diplomacy on social media (Yarchi, Samuel-Azran and Bar-David Citation2017).

TikTok, a relatively underexplored social media platform in the context of war, is marked by a unique visual culture, prone to ritualization due to its mimetic logic. Imitation and replication are latent in TikTok’s design, thus creating a mimetic infrastructure (Vijay and Gekker Citation2021; Zulli and Zulli Citation2022). TikTok features like stitch, duet, soundtrack, and greenscreen enable easy visual quotation and turn video editing, remix, and mashup – practices which used to require skill and software – into intuitive and commonplace forms of expressions (Literat, Boxman-Shabtai, and Kligler-Vilenchik Citation2022). The platform is known for its “audio memes” (Abidin Citation2020) – trending challenges characterized by cascading imitations with different degrees of personalization and adaptation. TikTok arguably fosters “imitation publics”, whose “digital connectivity is constituted through the shared ritual of content imitation and replication” (Zulli and Zulli Citation2022, 1882). Due to its mimetic logic and audio-visual density, battles over public image waged on TikTok inherently involve battles between images. Images fight for prominence against an abundance of imagery and an AI governed logic of content exposure (Zulli and Zulli Citation2022) and they fight for meaning, against the multiplicity of interpretations that characterize mimetic uptake.

Case Study: TikTok and the 2021 Israeli-Palestinian war

TikTok, available in Israel from 2019, played a central role in the social media landscape during the 2021 Israeli-Palestinian war, a series of confrontations between Israel and Hamas (the militant group that governs the Gaza Strip), between May 10th and May 21st, 2021. During those 12 days, at least 256 Palestinians and 12 Israelis were killed by Israeli airstrikes and Hamas rocket fire, there was extensive damage to civilian infrastructure, and unprecedented clashes occurred within Israel’s borders between Israeli Jews and Israeli Arabs.

Like previous rounds of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a major part of the image war took place on social media (Yarchi Citation2023). Although Facebook, twitter, and YouTube, which dominated social media discourse in past violent clashes (Manor and Crilley Citation2018; Siapera, Hunt, and Lynn Citation2015; Zeitzoff Citation2018) were still widely used in 2021, TikTok particularly drew the attention of journalists and politicians. Videos created by young Palestinians exhibiting violence towards Israeli Jews in the weeks leading to the war were labeled by journalists as “TikTok Intifada” (Ward Citation2021); concerns about TikTok videos aggravating on-the-ground hostility were voiced throughout the war. A report by Orpaz and Siman-Tov (Citation2021) implied that Israel was far from victorious on the social media front. TikTok videos uploaded by Palestinians during the war (under the popular #Savesheikhjarrah and #Gazaunderattack) engaged in “playful activism” (Cervi and Divon Citation2023). Users lip-synced to the sound of popular Palestinian anthems like Atouna El-Toufoule, created duets with Israeli users, and reenacted pivotal scenes, like the arrest of activist Miriam Afifi (De Vries and Goomed Citation2022).

This paper seeks to fill two gaps in contemporary research about civic diplomacy on social media. First, extant research tends to focus on the message strategies and/or visual aesthetics of one party in a conflict (e.g., Cervi and Divon Citation2023; De Vries and Goomed Citation2022; Manor and Crilley Citation2018; Siapera, Hunt, and Lynn Citation2015; Yarchi Citation2022; Yarchi, Samuel-Azran and Bar-David Citation2017; Zeitzoff Citation2018). Our research seeks to comparatively examine battles over and with images across conflicting sides. By comparing communication on opposing sides of a conflict, it is possible to identify differences between antagonistic parties, as well as similarities. The comparison is also crucial for an assessment of the effectiveness of civic diplomacy efforts, as evident in the reach and engagement with posts across conflicting sides. Second, TikTok has received so far minimal attention in the context of war. Our research sets out to determine whether the platform’s signature features, such as mimesis and audio-visual density, change how conflict is communicated. By comparing the dynamics observed on TikTok with previous literature about civic diplomacy we seek to understand what distinguishes TikTok from other social media platforms. Focusing on civic diplomacy activism during the 2021 Israeli Palestinian war, we thus ask:

RQ1: How did pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian TikTok users communicate the war to an international audience?

RQ2: What factors contribute to highly engaging posts?

Method

The study utilized a mixed-method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative content analysis of TikTok posts circulated during the war.

Sample

Our analysis compares discourse on two popular and rhetorically equivalent hashtags that represent support toward opposing sides in the conflict: #israelunderattack – promoting pro-Israeli sentiment, and #gazaunderattack – promoting pro-Palestinian sentiment.Footnote1 Using Apify’s TikTok search, we downloaded all posts published under these hashtags during the conflict’s 12 days (May 10–21, 2021). From these purposively selected hashtags (1,462 posts) we randomly sampled 500 posts (250 from each hashtag). In line with our focus on civic diplomacy initiatives, we selected from this sample only posts that: (1) demonstrated civic diplomacy (i.e., published by individuals rather than official/governmental accounts), (2) targeted the international community (i.e., featuring English in text or video, rather than solely Arabic or Hebrew). The final corpus for the quantitative content analysis includes 318 posts: 126 from #gazaunderattack and 192 from #israelunderattack.

Content analysis

A quantitative content analysis was conducted by three trained coders using a codebook that probed for message strategies used by political actors during conflicts. Mostly drawn from previous studies dealing with formal and civic wartime diplomacy (e.g., Yarchi, Samuel-Azran and Bar-David Citation2017; Yarchi and Ayalon Citation2023), these measures include representation of victimization, blame, solution, immorality, national symbols, justifications, identifications, and personal stories. In addition, we recorded various engagement measurements (number of likes, comments, and shares) related to the sampled videos. lists the variables used in the quantitative analysis. A reliability test based on a random sample of 20% of the posts (N = 100) showed high levels of agreement between coders (Krippendorf’s alpha coefficient no lower than .751).

Table 1. The measurements used in the quantitative content analysis.

The quantitative analysis consisted of: (1) examining differences in the message strategies used in pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian TikTok posts, (2) analyzing user engagement metrices and their correlation with national affiliation and message strategies, and (3) analyzing the interaction effect between the video’s national affiliation and the message strategies used, on the video’s share count. We focused on shares because this engagement measure demands the greatest commitment from users, as it makes shared content visible on their feeds (Malhotra, Kubowicz Malhotra, and See Citation2013).

Semiotic analysis

The semiotic analysis was conducted after the quantitative content analysis, and it was informed by it in two ways. First, following the logic of focusing on top-shared videos as proxies of success, we constructed a subsample of the 21 most shared posts within each hashtag, 42 posts in total. Second, since the quantitative analysis revealed that traditional message strategies were not salient, the qualitative analysis focused on other ways with which users expressed themselves.

The first stage of the analysis consisted of identifying genres of civic diplomacy on TikTok. The analysis combined principles of social semiotics (Kress Citation2010) and visual framing (Rodriguez and Dimitrova Citation2011): Each post was analyzed in light of its denotative meaning (what is literally seen/heard), its semiotic and stylistic features (how image, sound, and text are arranged to create meaning), its connotative meanings (e.g., meanings not explicitly signified in the text, emerging from intertextual references and contextual knowledge), and the ideological meanings encoded through the various structures of signification. These meaning sources were compared inductively, leading to an identification of salient genres, namely, styles of address that share features of content, form, and interpretive expectations (Hallinan et al. Citation2023).

We initially interpreted the low frequency of established message strategies in the quantitative findings as an indication that persuasion and argumentation were not the sole form of expression in the posts. To further explore this idea, we examined the posts and the structuring genres we identified, considering the meta-communicative values they conveyed. Meta-communicative values are the perceptions engrained in a text about what communication ought to serve (Trillò, Hallinan, and Shifman Citation2022). We identified five salient meta-communicative values in the subsample – persuasion, demonstration, authenticity, affiliation, and creativity. Each post was coded with one primary meta-communicative value, and when relevant – secondary values. Next, meta-communicative types were matched with their most salient genres.

Findings

Battles over public image: Messaging Strategies and Success Rates

The two most prominent message strategies in the corpus were the use of national symbols (36.6%) and presenting the other side as immoral (27.8%). However, as shown in , many strategies commonly used in conflict were not salient in our analysis: unlike the findings of previous studies (e.g., Yarchi Citation2016, Citation2022), the analyzed TikTok posts did not focus on problem, cause and solution – the basic elements of framing (Entman Citation1993). Nor were message strategies of victimization (M = 1.28), blame (M=.88), and solution (1.3% of all videos), prominent. The appeal to compassion through personal stories appeared only in 11.4% of the corpus. The “what would you do” strategy aimed at creating identification was also not common (9.2%); neither were strategies of justification (7.3%) and presenting one’s own side as moral (7.4%). These low frequencies suggest that TikTok videos do not follow traditional wartime message conventions. While there are signs of users attempting to persuade audiences with established framing strategies, there is much going on that isn’t captured by these framing devices (a point explored in the semiotic analysis below).

We next investigated differences in message strategies between pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian videos.Footnote2 Although some of those strategies were more salient (such as the use of national symbols), and some were less salient (such as identification), a comparative analysis revealed differences in their employment across conflicting sides. Correlations between national affiliation and message strategies – both dichotomous measures – were examined using chi square and phi tests (see ). Correlations between national affiliation and victimization and blame (measured as continuous variables) were examined with T tests (see ). The analysis found that pro-Palestinian posts were significantly more likely to present personal stories, emphasize the immorality of the Israeli side and use national symbols. Pro-Israeli posts were more likely to employ the “what would you do” strategy, justify Israel’s actions, emphasize Israel’s victimization, and place blame on Palestinians. Pro-Israeli posts were also more likely to use duets and hashtags of the Palestinian side (a practice known as “hashtag hijacking”).Footnote3

Table 2. Correlations between the different sides of the conflict and various message strategies.

Table 3. Differences between the different sides of the conflict in various message strategies.

Comparatively examining the success of TikTok posts, we found a clear disparity in engagement levels across national affiliations. As presented in , pro-Palestinian videos generated more engagement from users on all possible measures – likes, comments and shares. Pro-Palestinian TikTok users tend to have more followers than pro-Israeli users. We used a series of regression models to measure engagement while controlling for number of followers, and message strategies used. Findings (presented in ) indicate that pro-Palestinian posts generated more user engagement, above and beyond the number of followers they had and the message strategies they used. Some message strategies influenced engagement: the presentation of victimization in TikTok videos (a strategy more frequent in pro-Israeli videos) reduced the number of Likes and shares; The blame strategy increased likes and reduced comments; Presenting the other side as immoral (a strategy more frequent in pro-Palestinian videos) increased comments and shares; and a higher number of followers unsurprisingly increased likes.

Table 4. Differences in users’ engagement to pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian videos.

Table 5. Regression models predicting users’ engagement.

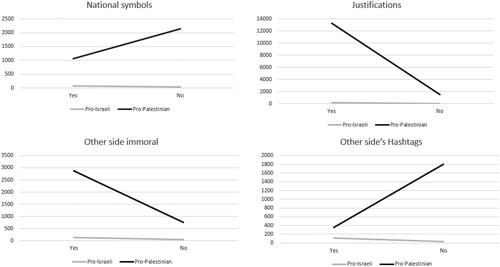

In the last stage of the quantitative analysis, we examined the shared (interaction) effect of national affiliation and message strategies on video share count. A two-way ANOVA analyses was used for nominal variables; regression models were used for victimization and blame. As can be seen in and in , four message strategies presented an interaction effect with national affiliation in creating a shared impact on share count. For pro-Palestinian videos, the use of justifications and the representation of the other side as immoral was associated with an increase in the share count, while the use of national symbols and Israeli hashtags was associated with a decrease in share count. For pro-Israeli videos, all four message strategies contributed to share count, though the baseline for shares on the Israeli side was significantly lower. A regression analysis of the victimization and blame variables (see ) indicated that blame contributed overall to share count, but especially for the pro-Palestinian videos. Victimization did not present an effect on share count.

Figure 1. Interactions effects of both the side of the conflict that had published the content and different message strategies on the number of shares the video generate.

Table 6. The effect of both the side of the conflict that had published the content and different message strategies on the number of shares the video generated (using two ways ANOVA).

Table 7. The effect of both the side of the conflict that had published the content and the message strategies of victimization and blame on the number of shares the video generated (using regression models).

Genres of Public Diplomacy on TikTok and Their Meta-Communicative Values

To better understand of what was not captured by the message strategies analyzed in the content analysis of TikTok posts, we conducted a qualitative semiotic analysis of a subsample of 42 highly shared posts. The analysis considered the visual aesthetics of the videos and their meaning structures to offer a typology of five meta-communicative values and corresponding expressive genres underlining civic diplomacy on TikTok. The meta communicative values (presented below in order of their salience) are ideal types; They were sometimes evident in pure form – that is, one text conveying a single meta-communitive value – but they were also often entangled and co-apparent in texts.

Persuasion: Making an Argument about the Conflict

The association between public diplomacy and persuasion is intuitive, and the indeed the focus of public diplomacy studies. About a quarter (12 out of 42) of posts were marked by persuasion as a main communicative value. Those posts were typically verbal (textually or orally), and they crafted arguments (or fragments of them), often containing elements of problem, cause, and solution framing. Posts marked by persuasion sought to influence the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of viewers by convincing them that a position is legitimate.

The critical monologue was an especially common genre of posts attempting persuasion. The genre presents an individual speaker expressing a critical stance towards the opposing group. It includes public forms of address (e.g., speeches delivered in United Nations assemblies, segments from media interviews) as well as homemade recordings (e.g., the quintessential selfie/webcam video). In both formats, posts typically layered additional critical meanings on top of the spoken words by adding captions and/or using the greenscreen, stitch, and duet effects as part of their argumentation. For example, in one post uploaded by a Canadian-Egyptian influencer (see ), the speaker summarized the death toll in Gaza (197) and in Israel (10) at the time, arguing that the two sides are not equal, and accusing Israel of genocide. Using TikTok’s reply feature she next presented on-screen a comment expressing support of Israel, exclaiming with teary eyes and an enraged voice “It kills me to see people supporting what Israel is doing right now and saying save Israel, pray for Israel. Save them from what? Please tell me, save Israel from what? what are we saving them from?!”Footnote4 As this example illustrates, though persuasion entailed an appeal to rationality (logos), the platform’s affective and performative logic also involved an appeal to emotion (ethos) and to the status of the speaker (pathos).

Most (9 out of 12) posts using primarily persuasive appeals were pro-Palestinian, accusing Israel of excessive use of force and war crimes. These posts often encouraged political action, asking viewers to spread the message, motivating them to do research (e.g., “Google the meaning of ‘from Gaza to the sea Palestine will be free’”) and explaining how get involved (e.g., joining the BDS movement).

Demonstration: Displaying Evidence from the Ground

Demonstration was marked as primary in 11 of the 42 sampled video. Posts coded under this meta-communicative value presented visual evidence to demonstrate a point about the war, and/or to illustrate its embodied, lived experience. If persuasion videos consist of “telling” (a speaker conveys an argument or a position), demonstration is motivated by “showing” – a speaker is usually not present in the image, and the argument – if one exists – is implied. Instead, the meta-communicative value of demonstration implores the audience to see for themselves.

The most common genre of demonstration was raw-footage documentation. This genre consists of unprofessional and lightly (if at all) edited video or photographic images from the ground. While users may add layers of meaning – like captions or soundtracks – the imagery is typically basic and short. The rawness of this imagery, marked, for instance by grainy or shaky footage, was a prominent component of its aesthetic, conveying the genre’s immediacy. For example, is a snapshot from a short video depicting Israeli police forces violently handling protestors in Sheik Jarrah. The caption “Israeli occupation soldiers assault Palestinian women in Sheick Jarrah Today. This is the human rights(sic)!!” presents fragments of an argument (i.e., that the IDF is an occupation army, that it violates human rights), but the real drama in the post emerges in the 15 chaotic seconds of an unstable camera panning soldiers pushing and women screaming.

Civic diplomacy marked by demonstrativeness was used equally in pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian posts, and it harnessed the power of the image to convey various points: from evidence of destruction and harm (e.g., visuals from Gaza after bombing), to an illustration of an emotion or experience (e.g., footage of Israelis running for shelter), to awe from the pyrotechnics of war (e.g., footage of missiles lighting up the sky being intercepted midair by the Iron Dome system).

Authenticity: Being True to the Facts and to Oneself

The Authenticity value (marked as primary in 9 of the 42 posts) conveys a dual expectation: that people should be truthful or accurate about the external reality, and that they should be in sync with their internal essence, that is – be true to themselves (Trillò et al. Citation2022). Both meanings were evident in the corpus. The most common genre of expression about truth was the montage, which is a composite text that includes fragments of different videos, photos, sound, and text (in contrast to raw-footage documentation that centers on one image source). The montage is the most heavily edited genre of expression, as it involves the selection and sequencing of multiple images. Thus, the meta-communicative value most concerned with truth was expressed with the most constructed form of expression. This might seem ironic, yet it also befits a long history of staged war imagery and a perpetual debate about the “realness” of photography (Sontag Citation2004).

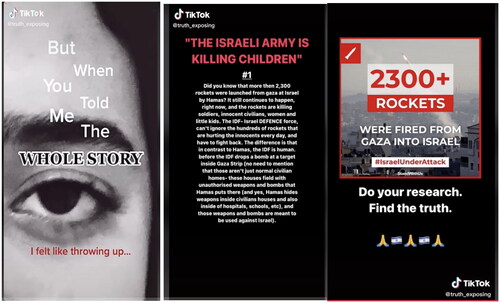

The external aspect of truth was particularly common in the subsample. Many posts questioned the accuracy of images and the trustworthiness of the opposite side in the dissemination of war imagery. For example, a pro-Israeli post (see ) created a montage that combined a persuasive appeal with self-evident and intertextual imagery highlighting authenticity. Set against a soundtrack titled “daddy issue remix”, the video begins with an extreme close-up on a female eye, next to which the song’s lyrics "but when you told me the whole story, I felt like throwing up" are displayed. These two semiotic elements connote an ethos of victimhood and speaking truth to power, assuming they are recognized by the viewer. The soundtrack is used in many TikTok challenges related to trauma (e.g., users displaying what they were wearing when raped). The extreme eye close-up is a familiar aesthetic on TikTok used to signify the gaze of the victim (used, for example, in the context of Black Lives Matter activism on the platform). Next, a slide with the title "THE ISRAELI ARMY IS KILLING CHILDREN", presents a counter argument, describing how Hamas stockpiles weapons and shoots it at Israel from civilian infrastructure and population. The text proceeds to describe measures taken by the Israeli army to minimize civilian harm. The video concludes with an image of a rocket, captioned: “2300+ Rockets were fired from Gaza to Israel. #Israelunderattack. StandWithUs. Do your research. Find the truth”. Thus, while this video presented a persuasive appeal, it was framed (in long and semiotically dense opening and closing sequences) through the desire to expose truth.

Inward authenticity, being true to oneself, was apparent in two pro-Palestinian posts. One post captioned “what it really means to be a Muslim”, presented a segment from a speech delivered by King Abdullah II of Jordan at the European Union Parliament in 2018 (three years before the war). The quoted segment highlights love and peace as true values of Islam. The captions in the video (a red X on the Israeli flag, and “save Palestine” by the Palestinian flag), contextualize this speech in relation to the ongoing war, making the implicit argument that Palestinians (a majority Muslim population) are peace seeking. Another post, which incorporated all four meta-communicative values, presented a sequence of photos of Palestinian life before 1948, demonstrating a lively commercial, cultural, and agricultural life. This montage both highlights an authentic identity of Palestinian nation and a counterargument to the idea of Mandatory Palestine as a “land without people to people without land”.

Affiliation: Signaling Joint Membership in a like-Minded Community

Trillò et al. (Citation2022) define affiliation as a signal of belonging to culturally defined units achieved by participating in activities that express (sub)cultural taste, allegiance to collective memory and/or goals, and individual commitment. Affiliation was marked as a primary meta-communicative value in 6 of the 42 sampled videos.

The archetypal genre of affiliation in the corpus was, again, the montage. Here two specific variations of the form surfaced. One variant, the celebrity montage, presented imagery (photo or video) of celebrities supporting a party within the conflict, thus cueing affiliation by counting the number of famous people “on our side”. Another variant, the rally montage, amalgamated footage from public demonstrations of support in favor of Israel/Palestine. These clips typically oscillated between two modes of visual representation: Long-shot videos depicting massive crowds in movement (signifying solidarity and legitimacy) and close-up still images of individual protestors holding up signs (signifying a particular argument or sentiment). The movements between these modes and the strategic selection of soundtracks created powerful visual narratives. Here too, the use of Intertextuality – in soundtrack and in signs – solidified and expanded the value of affiliation for those who recognized the reference.

For example, a montage of pro-Palestinian demonstrations around the globe () created affiliation on several levels of signification. The montage is set against Aurora’s song Runaway, and in particular the song’s chorus – “take me home where I belong”. “Home” is a polysemic code that could signify homeland (versus diaspora, literal homes under dispute (the war was triggered by the eviction of Palestinians from their homes in east Jerusalem), and the experience of Palestinian refugees. It starts with a compilation of video footage from pro-Palestine demonstrations around the world. Alongside the melodic soundtrack, diegetic sound from the protests (chanting and singing) adds concreteness to the imagery. Next, the montage presents a sequence of still images of protesters holding signs like: "We cannot breathe since 1948" (a reference to George Floyd’s final words), "How can a child be a terrorist?" (a reference to teenager Ahmad Manasra imprisoned in Israel), "another Jew against ethnic cleansing", and "if we lose Palestine, we lose humanity". The montage concludes with a text stating: "If you’ve chosen silence in times of injustice, you’ve chosen the side of the oppressor", followed by: "speak up, scream, share, expose #saveSheikhJarrah". The intertextual references in this montage signify several levels of affiliation: within the Palestinian community, the intersectionality between Palestinians and African Americans, between Palestinians and pro-Palestinian Jews, and between the Palestinian cause and humanity writ large.

Creativity: Conveying Messy Reality with Aesthetically Pleasing Imagery

Finally, 4 of the 42 texts were marked by the meta-communicative value of creativity. Such posts highlighted creative production, mainly visual/plastic art and various types of performance to convey a position (be it experience, sentiment, argument, etc.) about the war. In these posts, images were typically aesthetically pleasing and constructed.

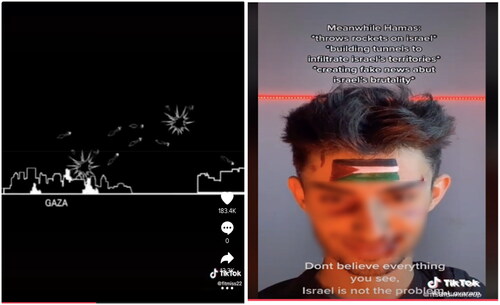

Two genres of creativity were evident in the subsample. One prominent genre was line-art and cartoons. For example, (left) shows a pro-Palestinian video illustrating lack of proportion in the conflict (thus incorporating persuasion as a communicative value) through a graphic storyline that draws heavily, visually and in soundtrack on computer game aesthetics. Another genre of creativity is performance, including the use of drama, comedy, and makeup art transformation to convey a sentiment/argument about the conflict. For example, in a pro-Israeli video (, right), a young man used makeup to illustrate an argument about Palestinian duplicity. The video commences with him displaying an injured Palestinian identity (signified with a bruised face and Palestinian flag), and dramatizing anguish through his facial expressions. Against a sharp change in musical soundtrack and lighting, the man switches to a satanic expression, with captions accusing Hamas of attacking Israel and spreading fake news.

The semiotic analysis helps explain the relative rarity of framing devices and other documented message strategies in the quantitative content analysis. It suggests that those were uncommon because (1) TikTok posts rely heavily on an audio-visual and intertextual style prone to carry implicit and connotative meanings which are hard to pin down in content analysis, and (2) TikTok posts do not necessarily seek to persuade their audience (in the traditional sense of crafting an argument), they also seek to demonstrate with raw imagery, negotiate the boundaries of truth and authenticity, form affiliation and community, and display creativity. While many of the posts in the subsample incorporated several mete-communicative values (e.g., authenticity and persuasion, demonstration and affiliation, etc.) Pro-Palestinian posts clearly dominated (6 to 2) a distinct group of posts that were coded as containing three or more meta-communicative values. Such texts are especially powerful as they unify distinct modes and values of communication. A text is more moving when it simultaneously persuades, demonstrates, and forms affiliation, to name one common combination. The incorporation of multiple meta-communicative values could have contributed to the success of Pro-Palestinian posts.

Conclusions

TikTok’s prominent role during the 2021 Israeli-Palestinian war allowed us to compare pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian uses of a relatively understudied platform for civic diplomacy. On one hand, the findings of this study continue previous scholarship on the intersection between media and conflict. Pro-Palestinian posts elicited more engagement than pro-Israeli posts, controlling for message strategies used, and for the number of followers. These findings illustrate the reverse-symmetry effect of modern conflicts (Yarchi and Ayalon Citation2023). They also resonate with theories that emphasize the influence of the political environment on the media (e.g., Wolfsfeld, Sheafer, and Althaus Citation2022). Thus, the increased empathy and support towards Palestinians were likely not derived from the message strategies used by either side but from their position in the conflict and the conflict’s politics (Ayalon et al. Citation2016).

On the other hand, the findings of this study shed light on new forms of expression in civic diplomacy. Message strategies discussed in the literature, such as the problem-cause-solution formula (e.g., Yarchi Citation2022) were not common in our corpus. Posts were rife with meta-communicative values that seek immediacy, realness, solidarity, and creativity, on top of good old persuasion. TikTok posts are regularly dismissed as shallow, superficial, and inaccurate – many in our sample were indeed that. However, their common reliance on mimetics and intertextuality turned them into deep multilayered heaps of meanings, that are unequally available, and depend on the viewer’s prior knowledge. The combination of our quantitative and qualitative analysis suggests that highly engaging civic diplomacy on TikTok is not necessarily characterized by persuasive arguments but by the combination of multiple meta-communicative values and effective intertextual references.

This study is limited by its reliance on two popular hashtags as anchors for corpus building. This approach, while justified by the goal of comparison, undermines the ability to evaluate the interwovenness of public discourse across various hashtags. Future work should experiment with more creative sampling procedures, to position civic diplomacy within a broader hashtag ecosystem (see Rathnayake and Suthers Citation2023). The reliance on hashtags, and the focus on user generated content is also limited as it sidelines user profiles and motivations. From our analysis it was clear that civic diplomacy on TikTok involved different actors and voices – such as users addressing their audience directly, repurposed clips of public personas, and ordinary people caught on tape, to name just a few. A future line of studies could examine how different actors within and across antagonistic parties practice civic diplomacy.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this study provides a useful tool for future work on civic diplomacy, digital activism, and wartime communication on social media. The typology could be utilized as a means to analyze and organize findings from other visual social media employed in other conflicts. It could also be further developed analytically in productive ways. Meta-communicative values capture the essence of communication (what is an utterance trying to convey), whereas other constructs such as frames (e.g., problem/solution) and rhetorical strategies (e.g., logos/pathos/ethos) capture the mechanisms of communication (how to craft a message). Disentangling the two constructs – by examining how different rhetorical strategies tie-in with meta-communicative values (e.g., How is authenticity conveyed through logos? Creativity through ethos? Etc.) could provide a holistic analysis of civic diplomacy, as well as other communicative practices and topics. Future development and application of this typology could also examine the impact of different genres and meta-communicative values. Coming full circle with the polysemy of “image war”, future studies employing the suggested typology could examine how its various types relate to different measures of success (and how they in turn relate to one another): reach and engagement measures may cue a country’s effectiveness in propagating a certain image (image war as reputation); memes, iconic status, and image recall may cue the image’s ability to stick in public memory (image war as “survival of the fittest images”). Such an analysis may find, for example, that a meta-communicative value like persuasion has better reach, but a meta-communicative value like affiliation has better endurance over time.

Images in general, and war imagery in particular, have always been contested in terms of their authenticity and meaning (Sontag Citation2004). Nevertheless, the battle over and with images is an inseparable part of conflict. Given the cultural dominance and profound cognitive effects of images on individuals, it is essential to understand how different actors construct a public image vis-à-vis multimodal social platforms, and the extent to which such strategies yield support and engagement, which are crucial in shaping public opinion and policy. The horrific images that came out of Israel and Gaza on October 7th, 2023, resurfaced some of the themes we discussed (and many more which deserve their own account). Social media, including TikTok, were central in the circulation of highly disturbing imagery, which was used on both sides to sway global public opinion. Various meta-communicative functions that extend beyond classic persuasion were evident (e.g., the use of imagery to terrorize). As social media are becoming increasingly intertwined with modern warfare, this paper provides a foundation to further explore the meaning and engagement created through civic diplomacy on densely visual and mimetic social media.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 These hashtags do not capture the full picture of TikTok communication during the war, but their popularity (both top ranked in aggregate views) and their prominence in journalistic and academic discourse enhance our confidence that they represent important hubs of civic diplomacy.

2 The statistical analyses controlled for differences in sample size between the pro-Israeli (192) and pro-Palestinian (126) videos.

3 Other message strategies examined (such as: us versus them, solutions, mockery/humiliation, religious symbols, call for action, number of hashtags used etc.) showed no significant differences across national affiliations.

4 Oral and written speech (e.g., captions) is quoted directly throughout.

5 While the representation of the other side as immoral is related to the general blame category, it focuses on evaluations of moral conduct as source of blame.

References

- Abidin, C. 2020. “Mapping Internet Celebrity on TikTok: Exploring Attention Economies and Visibility Labours.” Cultural Science Journal 12 (1): 77–103. https://doi.org/10.5334/csci.140

- Altheide, D. 1997. “The News Media, the Problem Frame, and the Production of Fear.” The Sociological Quarterly 38 (4): 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1997.tb00758.x

- Anton, A. 2022. “Conceptual Pathways to Civil Society Diplomacy.” Diplomacy, Organisations and Citizens, 2022, 81–98.

- Asmolov, G. 2021. “From Sofa to Frontline: The Digital Mediation and Domestication of Warfare.” Media, War & Conflict 14 (3): 342–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635221989568

- Ayalon, A., E. Popovich, and M. Yarchi. 2016. “From Warfare to Imagefare: How States Should Manage Asymmetric Conflicts with Extensive Media Coverage.” Terrorism and Political Violence 28 (2): 254–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.897622

- Boudana, S., P. Frosh, and A. A. Cohen. 2017. “Reviving Icons to Death: When Historic Photographs Become Digital Memes.” Media, Culture & Society 39 (8): 1210–1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717690818

- Cervi, L., and T. Divon. 2023. “Playful Activism: Memetic Performances of Palestinian Resistance in TikTok #Challenges.” Social Media + Society 9 (1): 205630512311576. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231157607

- Cull, N. J. 2021. “Canada and Public Diplomacy: The Road to Reputational Security.” In Canada’s Public Diplomacy, edited by N. J. Cull and M. K. Hawes, 1–12. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62015-2_1

- De Vries, M., and N. Goomed. 2022. “#save_ Sheikh_Jarrah: Strategies of Activism and Resistance to Violence on TikTok.” Misgarot Media 22: 91–122. https://doi.org/10.57583/MF.2022.22.10014

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Towards Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Esser, F. 2009. “Meta Coverage of Mediated Wars: How the Press Framed the Role of the News Media and of Military News Management in the Iraq Wars of 1991 and 2003.” American Behavioral Scientist 52 (5): 709–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764208326519

- Hallinan, B., B. Kim, R. Scharlach, T. Trillò, S. Mizoroki, and L. Shifman. 2023. “Mapping the Transnational Imaginary of Social Media Genres.” New Media & Society 25 (3): 559–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211012372

- Heemsbergen, L. J., and S. Lindgren. 2014. “The Power of Precision Air Strikes and Social Media Feeds in the 2012 Israel–Hamas Conflict: ‘Targeting Transparency.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 68 (5): 569–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2014.922526

- Hoskins, A., and B. O’Loughlin. 2010. War and Media (1st ed.). Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Kaun, A., and J. Uldam. 2018. “Digital Activism: After the Hype.” New Media & Society, 20 (6): 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731924

- Knightley, P. 2004. The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Iraq. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press.

- Kress, G. R. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. New York: Routledge.

- Kuntsman, A., and R. L. Stein. 2015. Digital Militarism: Israel’s Occupation in the Social Media Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Literat, I., L. Boxman-Shabtai, and N. Kligler-Vilenchik. 2022. “Protesting the Protest Paradigm: TikTok as a Space for Media Criticism.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 28 (2): 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221117481

- Malhotra, A., C. Kubowicz Malhotra, and A. See. 2013. “How to Create Brand Engagement on Facebook.” MIT Sloan Management Review 54: 1–4. http://sloanreview.mit.edu/ article/how-to-create-brand-engagement-on-facebook/.

- Manor, I., and R. Crilley. 2018. “Visually Framing the Gaza War of 2014: The Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Twitter.” Media, War & Conflict 11 (4): 369–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635218780564

- Milner, R. M. 2013. “Pop Polyvocality: Internet Memes, Public Participation, and the Occupy Wall Street Movement.” International Journal of Communication 7: 2357–2390.

- O’Loughlin, B. 2011. “Images as Weapons of War: Representation, Mediation and Interpretation.” Review of International Studies 37: 71–79.

- Orpaz, I., and D. Siman-Tov. 2021. The Unfinished Campaign: Social Media in Operation Guardian of the Walls. INSS. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/guardian-of-the-walls-social-media/.

- Peters, C., and S. Allan. 2022. “Weaponizing Memes: The Journalistic Mediation of Visual Politicization.” Digital Journalism 10 (2): 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1903958

- Pötzsch, H. 2015. “The Emergence of iWar: Changing Practices and Perceptions of Military Engagement in a Digital Era.” New Media & Society 17 (1): 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813516834

- Rabasa, A. 2011. “Where Are We in the ‘War of Ideas’?.” In The Long Shadow of 9/11: America’s Response to Terrorism, edited by B. M. Jenkins and J. P. Godges, 61–70. California: RAND Corporation.

- Rathnayake, C., and D. Suthers. 2023. “Towards a ‘Pluralist’ Approach for Examining Structures of Interwoven Multimodal Discourse on Social Media.” New Media & Society 2023 (89):800. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231189800

- Rodriguez, L., and D. V. Dimitrova. 2011. “The Levels of Visual Framing.” Journal of Visual Literacy 30 (1): 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2011.11674684

- Roger, N. 2013. Image warfare in the war on terror. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Samuel-Azran, T., and M. Yarchi. 2018. “Military public diplomacy 2.0: The Arabic Facebook Page of the Israeli Defense Forces’ Spokesperson.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13 (3): 323–344. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11303005

- Sharp, P. 2001. “Making sense of citizen diplomats: The people of Duluth, Minnesota, as International Actors.” International Studies Perspectives 2 (2): 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1528-3577.00045

- Shifman, L. 2013. “Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 18 (3): 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013

- Siapera, E., G. Hunt, and T. Lynn. 2015. “#GazaUnderAttack: Twitter, palestine and diffused war.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (11): 1297–1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1070188

- Sontag, S. 2004. Regarding the pain of others. New York, NY: Picador.

- Stein, R. L. 2021. Screen shots: State Violence on Camera in Israel and Palestine. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- Trillò, T., B. Hallinan, and L. Shifman. 2022. “A Typology of Social Media Rituals.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 27 (4):11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac011

- Van Evera, S. V. 2006. “Assessing US Strategy in the War on Terror.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 607 (1): 10–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206291492

- Vijay, D., and A. Gekker. 2021. “Playing Politics: How Sabarimala Played out on TikTok.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (5): 712–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221989769

- Media, Wallaroo. 2022, August 13. TikTok Statistics—Everything You Need to Know [Aug 2022 Update]. https://wallaroomedia.com/blog/social-media/tiktok-statistics/.

- Ward, A. 2021, May 20. The “TikTok intifada.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/22436208/palestinians-gaza-israel-tiktok-social-media.

- Wiggins, B. E. 2016. “Crimea River: Directionality in Memes from the Russia-Ukraine Conflict.” International Journal of Communication 10 (0): 451–485.

- Wolfsfeld, G. 2022. Making Sense of Media and Politics: Five Principles in Political Communication, Second ed. New York: Routledge.

- Wolfsfeld, G., T. Sheafer, and S. Althaus. 2022. Building Theory in Political Communication: The Politics-Media-Politics Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wolfsfeld, G., and M. Yarchi. 2015. “Conflict/War.” In The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, edited by G. Mazzoleni, K. G. Barnhurst, K. Ikeda, R. C. M. Maia and H. Wessler 199–201. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Yarchi, M. 2014. “Badtime’ Stories: The Frames of Terror Promoted by Political Actors.” Democracy and Security 10 (1): 22–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17419166.2013.842168

- Yarchi, M. 2016. “Does Using ‘Imagefare’ as a State’s Strategy in Asymmetric Conflicts Improve Its Foreign Media Coverage? The Case of Israel.” Media, War & Conflict, 9 (3): 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635215620826

- Yarchi, M. 2022. “The Image War as a Significant Fighting Arena – Evidence from the Ukrainian Battle over Perceptions during the 2022 Russian Invasion.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 2022: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2022.2066525

- Yarchi, M. 2023. “Digital Public Diplomacy during Wars and Conflicts.” In Bjola, C. and Manor, I., (Eds.). The Digital Diplomacy Handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yarchi, M., and A. Ayalon. 2023. “Fighting over the Image: The Israeli − Palestinian Conflict in the Gaza Strip 2018 − 19.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 46 (2): 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1751461

- Yarchi, M., T. Samuel-Azran, and L. Bar-David. 2017. “Facebook Users’ Engagement with Israel’s Public Diplomacy Messages during the 2012 and 2014 Military Operations in Gaza.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 13 (4): 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-017-0058-6

- Yi, K., P. Hayes, J. Diamond, S. Denney, C. Green, and J. Seo. 2015. “The Implications of Civic Diplomacy for ROK Foreign Policy.” Complexity, Security and Civil Society in East Asia, 319–392. Cambridge: Foreign Policies and the Korean Peninsula.

- Zeitzoff, T. 2018. “Does Social Media Influence Conflict? Evidence from the 2012 Gaza Conflict.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62 (1): 29–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002716650925

- Zulli, D., and D. J. Zulli. 2022. “Extending the Internet Meme: Conceptualizing Technological Mimesis and Imitation Publics on the TikTok Platform.” New Media & Society 24 (8): 1872–1890. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820983603