Abstract

Background

Interest in health care provider (HCP) wellness and burnout is increasing; however, minimal literature explores HCP wellness in the context of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) care.

Objectives

We sought to determine rates of burnout and resiliency, as well as challenges and rewards in the provision of ALS care.

Methods

A survey link was sent to physicians at all Canadian ALS centers for distribution to ALS HCPs in their network. The survey included demographics questions, and validated measures for resiliency and burnout; the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) and the Single Item Burnout Score (SIBS). Participants were asked to describe challenges and rewards of ALS care, impact of COVID-19 pandemic, and how their workplace could better support them.

Results

There were 85 respondents across multiple disciplines. The rate of burnout was 47%. Burnout for female respondents was significantly higher (p = 0.007), but not for age, role, or years in ALS clinic. Most participants were medium resilient copers n = 48 (56.5%), but resiliency was not related to burnout. Challenges included feeling helpless while patients relentlessly progressed to death, and emotionally charged interactions. Participants found fulfillment in providing care, and through relationships with patients and colleagues. There was a strongly expressed desire for increased resources, team building/debriefing, and formal training in emotional exhaustion and burnout.

Conclusions

The high rate of burnout and challenges of ALS care highlight the need for additional resources, team-building, and formal education around wellness.

Introduction

Health care provider (HCP) wellness has garnered increasing attention recently, with rising levels of burnout amongst Canadian physicians post-COVID-19 pandemic (Citation1). Burnout and occupational stress have been explored in many fields including nursing, physical therapy (Citation2,Citation3), and in palliative care where burnout rates ranging from 30–60% are reported (Citation4–7). However, there is little literature exploring health care provider wellness in the context of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) care.

ALS is a devastating neurologic disease with limb, bulbar, and respiratory dysfunction (Citation8). ALS inevitably results in death, usually within 2–5 years, and clinic visits for patients with advanced disease are often focused on a palliative approach. Many ALS clinics do not have a dedicated palliative care provider, and team members provide palliative support in addition to their other roles (Citation9). It is well recognized that caring for patients and families at end of life is emotionally challenging. The patients’ physical, emotional/psychological, and existential distress, and the grief of family members can lead to emotionally charged interactions resulting in higher rates of burnout amongst palliative care providers (Citation4).

It is generally understood that providing ALS care is emotionally challenging, but there is minimal literature exploring this. A survey of neurologists and nurse managers uncovered widely variable levels of stress as measured from “none” to “very severe” at time points of diagnosis delivery, during patient care, and time of death (Citation10). While this study demonstrated high job satisfaction, a significant number considered leaving their position due to stress and operational issues. Breaking the news of an ALS diagnosis can cause significant distress for both residents and practicing neurologists (Citation11,Citation12). Moral distress can arise when HCPs feel they must address important end of life decisions with patients who are not ready to do so (Citation13). Withdrawing noninvasive ventilation from patients with ALS at end of life was emotionally challenging for palliative care physicians (Citation14). There has been a call for increased recognition of the moral distress inherent in ALS care provision, and increased support for these HCPs (Citation15).

The World Health Organization defines burnout as a syndrome ‘resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed’ characterized by exhaustion, depersonalization or negativism/cynicism, and a sense of ineffectiveness (Citation16). Burnout is important to address since it has been associated with poor mental and physical health, reduced empathy, medical errors, lower quality of patient care, physican absenteeism and attrition (Citation5). Resilience has been defined as the capacity to ‘recover after exposure to stressful circumstances or events (Citation4).’ It is postulated that resiliency can be improved with learning and effort.

We wished to study rates of resiliency and burnout in multidisciplinary ALS HCPs. We hypothesized that a high rate of burnout would be uncovererd. We also wished to explore the challenges and rewards inherent in providing ALS care, and elicit participant views in how HCP wellness could be better supported.

Participants and methods

ALS HCPs in Canada completed an anonymous online survey between 3 April – 31 May 2023. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University) was used to allow for anonymous participant responses, support data capture for research studies, secure layer encryption and ensure secure web authentication (Citation17). The University of Saskatchewan granted ethics approval (Beh-REB# 4040). The consent form was located on the first page of the online REDCap survey, and all participants were required to consent before proceeding to the survey questions.

Subjects

The national organization ALS Canada distributed the survey description and REDCap link to all members of the Canadian ALS Physician network (CALS) via email. This encompassed the 23 recognized CALS centers for the provision of ALS Care across Canada (Citation18), and all 44 CALS physicians (neurologists and physiatrists) who provide care at these sites received the email invitation/survey link. These physicians were encouraged to complete the survey, and specifically asked to forward to other physicians from additional subspecialites as applicable, as well as other professionals such as nurses, physical and occupational therapists, respiratory therapists, dieticians, speech language pathologists, social workers, psychologists, research assistants, and clinical coordinators involved in ALS care as part of a snowballing sampling technique.

Survey design

The survey was designed to be sufficiently brief to encourage participation, yet include enough data to ensure meaningful results. We used previously validated, brief, and well utilized outcome measures for both burnout and resiliency, as well as open ended questions about wellness in the context of ALS care. The survey was designed in 3 parts; 1) demographic questions, 2) burnout and resiliency measures, and 3) free text questions. Prior to distribution, the survey was pilot tested by the researchers, using themselves as nonparticipating test subjects, to ensure the online survey was capturing data correctly. The 5 demographic questions included age, gender, province, role in clinic, and number of years in practice.

The survey included nonproprietary and validated measures for both resiliency and burnout and participants were asked to respond in the context of their ALS care provision. The Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) has been utilized in multiple studies of health care professionals (Citation19–22). It is comprised of 4 statements; 1) I look for creative ways to alter difficult situations, 2) Regardless of what happens to me, I believe I can control my reaction to it, 3) I believe I can grow in positive ways by dealing with difficult situations, and 4) I actively look for ways to replace the losses I encounter in life. Each question is scored on a scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 5 (describes me very well). Once the total score is calculated, participants are characterized as low (Citation4–13), medium (Citation14–16), and high (Citation17–20) resilient copers according to the predefined scoring system. The Single Item Burnout Score (SIBS) has been shown to be a reliable substitute for the Maslach Burnout Inventory Emotional Exhaustion (MBI:EE) and has been used in several studies in the healthcare setting (Citation23–27). The SIBS consists of a single question ‘Overall, based on your definition of burnout, how would you rate your level of burnout?’ and participants choose one of 5 answers (1 = I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout, 2 = Occasionally I am under stress, and I don’t always have as much energy as I once did, but I don’t feel burned out, 3 = I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion, 4 = The symptoms of burnout that I’m experiencing won’t go away. I think about frustration at work a lot, 5 = I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help.) The scoring is dichotomized between no burnout (2 or less) and burnout (3 or more).

The participants were also asked open-ended questions regarding provision of services to patients with ALS. The questions were: 1) What makes caring for patients with ALS emotionally challenging? 2) What makes caring for patients with ALS rewarding? 3) How could your work environment/institution improve to better support your ALS team’s wellness? 4) Has caring for patients with ALS during the pandemic impacted your wellness? How? 5) What are your additional ideas about how to promote ALS provider team wellness?

Data analysis

REDCap software managed and collected data. Participant responses were anonymized, reviewed for completeness and analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM Corp). The open-ended survey data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis; a qualitative method of data analysis used to identify and analyze themes or patterns (Citation28). This method involves familiarization with the data through iterative review, generating codes/themes, reviewing themes through revisiting the data, refining and renaming themes, and locating examples of those themes (Citation29). Two researches (KLS, GH) independently reviewed the data and followed this process to uncover recurring patterns. Discrepancies between the researchers were resolved through an iterative process of discussion and reexamination of the themes until consensus was reached. Quantitative data were summarized as proportions, and comparisons between i) BRCS and sex, age, role or years in clinic; ii) SIBS and sex, age, role or years in clinic; and ii) BRCS and SIBS, utilized chi-square statistics. A point-Biserial correlation was also calculated between the BRCS numerical score and SIBS dichotomy.

Results

Demographic data

All surveys were fully completed (no partially completed surveys). The participant characteristics are summarized in . There were 85 respondents from 9 Canadian provinces. All Canadian provinces were represented except for Prince Edward Island, which is the smallest province. The majority of respondents were female (n = 59, 69%) compared to male (n = 25, 29%). All ages from 20–29 category to the 60+ category were represented, with most participants in the age 40–49 category. Physicians comprised 40% of the responses (n = 34), with additional representation from nine other health professions (n = 51, 60%) including nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, respiratory therapy, speech language pathology, dietician, social work, research assistant, and other. The majority of respondents had been practicing in an ALS clinic 10 years or less, but those who provided care in clinics for longer periods, even greater than 25 years, also participated.

Table 1. Participant Demographics.

Resiliency and burnout

Data from the BRCS indicated that the majority of participants were medium resilient copers n = 48 (56.5%), followed by high resilient copers n = 21 (24.7%) and low resilient copers n = 16 (18.8%). There were no significant differences in resiliency scores in regards to sex (χ2 = 1.67; p = 0.44), age (χ2 = 1.44; p = 0.49), role (χ2 = 0.01; p = 0.99), or years in clinic (χ2 = 0.43; p = 0.81).

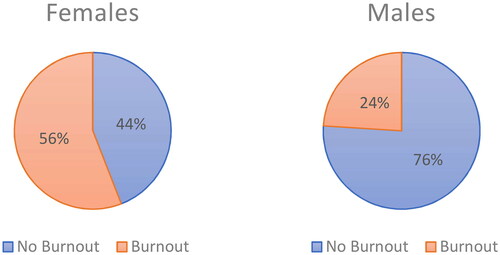

According to the SIBS, the rate of burnout (score of 3 or more) was 47% (n = 40) amongst ALS care providers. Burnout was more common in females (n = 33, 56%) as compared to males (n = 6, 24%) (χ2 = 7.20; p = 0.007) (). Burnout was not significantly different with age (χ2 = 9.23; p = 0.06), role (χ2 = 1.33; p = 0.25) or years in clinic (χ2 = 2.92; p = 0.71).

Data of resiliency versus burnout is summarized in . There was a significant difference between burnout and BRCS using chi-squared statistics (χ2 = 10.12; p = 0.006). As well, the two variables demonstrated a low point-biserial correlation (r = −0.188).

Table 2. Brief Resilient Coping Scale versus Single Item Burnout Score (n = 85).

Challenges in ALS care provision

When asked to describe the factors that make caring for patients with ALS emotionally challenging, four major themes emerged; patients’ rapid deterioration until death, emotionally challenging interactions, feeling helpless, and institutional pressures/lack of resources.

1) Rapid deterioration/inevitable death

Many participants found it difficult to watch the relentless progression of disease, and described distress in knowing that even best treatments would be unable to alter the course of disease in a significant way. Providers found it challenging to deal with the frequent deaths of patients for whom they had provided care for some time.

‘They all die. Every time we meet someone new, we know they only have a limited time left to live. They carry a heavy burden and we feel/share that burden.’

‘It’s difficult when every conversation may turn into an end of life conversation and patients deteriorate rapidly from one clinic to another.’

‘You get very invested in the intimate details of their lives by programming speech devices with their entire life’s worth of details. You meet with the patient and families frequently as needs change. They pass away quickly and it can be an emotional gut punch.’

2) Emotionally challenging interactions

Multiple participants discussed the secondary trauma of witnessing families deal with continual loss. The HCPs described their investment into the lives of their patients, and felt the losses alongside them. End of life discussions were emotionally challenging, particularly when patients/families did not accept the diagnosis and its implications.

‘It’s a heavy emotional toll. The focus is on holistic well being and as we cannot physically cure their illness we invest more in their mental and emotional well being while trying to help them enjoy the value in their lives that they have. Dealing with a fatal illness that takes parts of the person slowly requires so much of the provider.’

‘Patients and families’ extreme frustration with the disease is deflected toward us.’

‘[There is an] emotional impact of creating a space for patients and their families to grieve the illness, their current loses and future loses, walking with patients through their journey with ALS when it is very difficult for patients to find moments of hope/joy in the face of this illness.’

3) Feeling helpless

Participants stated that they felt helpless in the face of a relentlessly progressive disease with devastating effects. They cited a lack of resources, equipment, time, and the absence of a medication to significantly alter the outcome as contributors.

‘[There’s a] feeling of inability to truly help these patients. We know the outcome of the disease and even though we try to help, it feels sort of inconsequential.’

‘[It’s] hard to find solutions that last very long as they change so quickly. Trying to provide them with hope but knowing at some point there isn’t a good solution anymore.’

‘They all die. They are looking for hope which you cannot necessarily accommodate.’

4) Institutional pressures/lack of resources

A consistent theme was the lack of resources dedicated to ALS clinics in order to provide necessary care. The time pressures of having to address continual urgent situations, and the lack of resources to do so were cited as considerable sources of distress.

‘Insufficient funding and staffing ratios – being asked to ‘do the impossible’ with respect to caseload numbers for years on end.’

‘Not having the human resources to be able to provide the care our patients need. Moral distress knowing that if you just had more time, you could be proactive in their care rather than reactive which does not always result in a positive outcome.’

‘Lack of community resources to support clients and caregivers. High caseload. Unpredictable schedule.’

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Thirty-nine percent of participants felt that working in the ALS over the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their wellness. When asked to describe the effect, both positive and negative impacts were discussed. Some participants stated that working with colleagues in a multidisciplinary clinic, and working with this patient population actually improved their mood. Others cited clinic shutdowns, limited access to resources, and resultant delays in diagnosis as having negative impact on their wellness. However, the majority of respondents (61%) felt that providing ALS care during the pandemic had no impact on their wellness.

‘It was always hard. The pandemic didn’t change that.’

Rewards in ALS care provision

While providing care in ALS is challenging, it was clear that participants found caring for this population extremely rewarding. The benefits included relationships with patients/families, relationships with the team, finding fulfillment in helping, and appreciation from patients/families.

1) Relationships with patients/families

Many providers found their patients’ responses to adversity inspiring, and found deep satisfaction in building these relationships. Connections with these patients and families were described as an honor, a privilege, a reward. HCPs felt that walking through the ALS experience with patients ‘puts your own problems in perspective’ and that this allowed them to see the ‘beauty in life magnified.’

‘The patients and families are seemingly endlessly resilient. Their positivity and ability to cope with frequent setback is humbling.’

‘The work we do is so immensely valuable. It is such an honor to sit with a patient in their grief and see the person they were and are outside of their illness.’

‘Sharing deeply private and emotional conversations with patients and families, knowing that someone trusts you enough to open their hearts [is rewarding]. I'm privileged to have the chance to share these most initmate moments with patients and families.’

2) Relationships with the team

The support and camaraderie of the multidisciplinary team was a frequently cited benefit of caring for this population. The relationship between team members sustained the HCPs when dealing with emotionally challenging situations, death and dying.

‘My amazing co-workers truly care for these patients. We support each other.’

‘They are all such wonderful people. The team is great to work with.’

[It’s rewarding] knowing you’re a small cog in the wheel of their care, and like everyone else involved you only want the best for that person and their loved ones.’

3) Fulfillment in helping

Participants consistently discussed the personal satisfaction they derived from doing their best for patients, and being able to offer resources, answer questions, and provide hope. Being able to provide tangible solutions was extremely meaningful, particularly for those patients who ‘have no other avenue for hope.’

‘The patients I work with are the most positive, strong willed individuals in the face of an awful diagnosis. It is rewarding to see them try new things and adapt to their changing function as best they can. It is also rewarding when you can find a solution to a problem they are having that makes their lives easier.’

‘Having the ability to inject some meaning, hope, and dignity into what is otherwise an inevitable tragedy.’

‘So much is rewarding. Listening to their story, helping them with financial applications or assisting them with anything they may need.’

4) Appreciation from patients/families

It was rewarding for providers to hear words of appreciation and thanks from patients and families. Despite the many challenges, knowing that their work was appreciated was extremely fulfilling.

‘Most of patients appreciate what we do for them. I feel like I really make a difference in their lives.’

‘[It is rewarding] when you see a patient and you are able to put a smile on their face, even for a brief moment. When you suggest something to help with a symptom and it works and the patient is grateful.’

Institutional support for wellness

Participants were asked how their work environment/institution could improve to better support wellness. The major themes were need for additional resources, team debriefs/grief support, and acknowledgement from the institution.

1) Additional resources

Both human resources (more time allotment to clinic, vacation coverage, administrative support) as well as patient equipment needs (including supplies for noninvasive ventilation) were discussed. Participants described needing to constantly fight to obtain or keep basic resources. A consistent theme was the lack of adequate allied health support (nursing, social work, occupational therapy) to address the complex needs of patients.

‘We are dealing with an impossible task of managing more patients than we can handle. WE NEED HELP.’

‘Ensure that adequate resources exist to support patients properly. There is nothing worse than feeling like needs of patients are not met, and there is nothing we can do about it.’

‘Ensure enough resources - particularly in regard to time and compensation. These patients are complex, and often a lot of follow-up care is required. Most of us are happy to provide this care - however, if we do not have the time to complete it, then burnout is likely.’

2) Team debriefs/grief support

Given the challenging interactions and emotionally charged conversations inherent in ALS care, the majority participants felt they would benefit from more consistent team building exercises and debriefing. They also felt that formal training to deal with grief and burnout would be valuable. Provision of counseling and participation in wellness exercises were encouraged. More information for team leaders on how to support their teams was requested.

‘More education, formal support sessions regarding burnout, trauma-informed care, and compassion fatigue.’

‘Occasional but regular team building activities that foster inter-colleague relationships and non-work related conversations.’

‘More team building. Suggestions on how to actually deal with burn out or how to not reflect it back on your own life.’

3) Acknowledgement

Participants stated that the institutions should take an active role in providing the additional human resources to sustain high quality care, to facilitate the team debriefing, and to provide training in wellness. It was felt that the institution did not appreciate or fully understand the complexity of care offered by the clinic, and what each job entailed. Practitioners felt that they were operating “in an island.” There was not felt to be adequate remuneration or time allotment for the heavy paperwork burden and complex follow up.

‘We need a clear understanding from management that multidisciplinary care is complex, time consuming, detailed, specific, and exhausting.’

‘More managerial support to ensure that we are able to sustain the high level of care we provide considering we are a multi-disciplinary and multi-functioning clinic.’

‘I think each institution needs to be more aware of how the health care team that works with ALS patients and families is emotionally impacted.’

Discussion

Unsurprisingly, a high rate of burnout was found in nearly half of the respondents (47%). According to a systematic review, it is challenging to compare rates of burnout across studies, or to accurately define rates of burnout given the different outcome measures and methodologies utilized; a very wide range of burnout rates in physicians has been reported from 0–80% (Citation30). Physician burnout was 53% in the Canadian National Physician Health Survey, and also 53% in the 2023 Medscape National Physician Burnout and Suicide Report (Citation31,Citation32). Palliative Care practitioners are felt to be at high risk of burnout given the emotional toll of caring for those with terminal illnesses, but even here, rates of burnout are variable, ranging from 30–60% (Citation4–7). According to the 2018 Medscape National Physician Burnout study, neurologists tied for highest levels of burnout amongst 29 specialties surveyed (48%) (Citation33). A survey of over 4000 American neurologists demonstrated that approximately 60% had at least one symptom of burnout (Citation34). It was postulated that contributing factors included the personality traits of those who choose neurology, the detailed and lengthy assessments, and the devastating nature of many neurologic illnesses. Rates of burnout were 45% in a systemic review of nurses (Citation2), 38% in a survey of American primary care providers/nurses (Citation23), and 31% in a Spanish survey of physical therapists (Citation3). The high burnout in our study was comparable to those rates in the literature for neurology and palliative care providers. This underscores the importance of our qualitative data; we truly learn about the specific needs and challenges of ALS HCPs when we explore their thoughts.

While the rate of burnout in our study was more than double for females (56%) than for males (24%), there were no statistically significant relationships found for any other demographic variables studied. This gender discrepency has been seen in other surveys of physician burnout including the Canadian National Physician Health Survey (23% increase in odds) (Citation31), the 2023 Medscape National Physician Burnout and Suicide Report (63% female vs 46% male) (Citation32) and an American survey of neurologists (65% female vs 58% male) (Citation35). It has been postulated that there are multiple factors contributing to this observation, including competing family interests, workplace inequities, (Citation35) and the finding that on average, female physicians spend more time with each patient, and might demonstrate a more compassionate manner, thus putting them at risk for emotional exhaustion (Citation36).

In our study, resiliency scores were not related to burnout, suggesting that regardless of level of resiliency, all are at risk for burnout. This is a similar conclusion to a large study of resiliency and burnout in over 5000 American physicians. While higher burnout scores were related to lower scores of resilience, even amongst those with the highest possible resilience scores, burnout was seen in 29% (Citation37). Resilience and burnout were also found to have a complex relationship without definitive correlation in nurses (Citation38). Our study did not uncover a relationship between demographic data (age, sex, role, years in clinic) and resiliency. While a study of Canadian palliative care physicians demonstrated a correlation between older age and increased resiliency which was interpreted as a ‘survivor effect’ (Citation5), a systematic review of physicians and resiliency demonstrates that the vast majority of studies do not uncover a relationship between resiliency and demographic data (Citation39). This emphasizes the importance for all providers to acknowledge the risk of burnout for themselves and for their teams, regardless of their perceived level of resiliency.

The National Physician Health Survey demonstrated that burnout amongst Canadian physicians rose significantly after the COVID-19 pandemic (53%) compared to rates of burnout pre-pandemic (31%) in 2017 (Citation31,Citation40). This increase in burnout was also seen in the Medscape National Physician Burnout reports (42% in 2018, 53% in 2023) (Citation32,Citation33). In our study, 61% of respondents did not feel that caring for patients during the pandemic impacted their wellness, and cited both negative and positive effects of caring for ALS patients during the pandemic. It must be recognized that most ALS HCPs have roles in addition to the ALS clinic, and their wellness may have been impacted by these other working environments as well as the effect of the pandemic on life in general.

The responses to the open-ended questions are a rich account of HCPs interactions with patients and their families, and tell a story of challenges, rewards, and needs that cannot be captured on quantitative measures alone. Unlike most areas of medicine, with the exception of palliative care, all patients with ALS die. Observing the relentlessly progressive neurologic symptoms to death, and engaging in emotionally charged interations have left providers feeling helpless and unsupported by their workplace. A consistent theme was a call for additional resources, particularly human resources. Despite the heavy emotional toll, HCPs described caring for patients with ALS as an honor and a privilege. This is consistent with a previous study showing that while ALS care provision was stressful, there was high job satisfaction (Citation10). In our study, rewards of ALS care provision included relationships with patients/families, fulfillment in helping, appreciation from patients, and relationships with other team members. This is congruent with previous finding that HCP resilience is associated with support from peers (Citation41), emphasizing the need for intentional team building activities.

The majority of HCPs in the study asked for additional team building/debriefing, and formal training in grief, compassion fatigue, burnout, and wellness. No HCP volunteered that they had received any formal training in these areas, nor are the authors aware of any training for HCPs specifically in the context of Canadian ALS clinics. While there may be institutional supports for wellness in general, this may not be known to ALS HCPs, and there might be value in specific training in context of ALS. Studies assessing strategies to improve HCP wellness in other fields have resulted in generally favorable responses (Citation42–44). Improvement in physician resiliency was found with cognitive behavioral and solutions based counseling, but there was a less clear response for mindfulness strategies (Citation39). This study demonstrates a voiced request for ALS provider wellness strategies and education.

Limitations of this study include the inability to clearly identify the survey response rate due to the snowballing recruitment strategy employed, whereby participants forwarded the link to colleagues. However, this allowed for greater representation across geographical regions and provider roles, and for a country with relatively few ALS HCPs, we consider 85 responses to be robust. It cannot be known if the survey was truly representative of all HCPs in Canada. The survey was not translated into French, which may have limited participation from Quebec. There were fewer responses for some provinces and more for others than expected based on population alone. It is possible that HCPs in different institutions within the same province may have answered disparately, but our sample size was too small to capture this. Those who felt particularly strongly about the topic might be more likely to complete a survey. Physicians were likely over-represented (40%), possibly because physicians were the first to receive the survey invitation prior to forwarding it to other HCPs. As such, the data cited from existing literature in our discussion is also more heavily weighted toward the physician experience, however, this does limit the applicability to our results which were truly multidisciplinary.

This survey of ALS HCPs in Canada demonstrates a high rate of burnout regardless of level of resiliency, and discusses the challenges, rewards, and needs in providing care for patients with ALS. These results highlight the need for additional resources, team-building, and formal education around wellness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank ALS Canada for facilitating the survey distribution, and the ethics research board at the University of Saskatchewan for an expedited review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Canadian Medical Association [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 28]. A profession under pressure: results from the CMA’s 2021 National Physician Health Survey. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/news/profession-under-pressure-results-cmas-2021-national-physician-health-survey

- Hosseini M, Soltanian M, Torabizadeh C, Shirazi ZH. Prevalence of burnout and related factors in nursing faculty members: a systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2022;19:16.

- Carmona-Barrientos I, Gala-León FJ, Lupiani-Giménez M, Cruz-Barrientos A, Lucena-Anton D, Moral-Munoz JA. Occupational stress and burnout among physiotherapists: a cross-sectional survey in Cadiz (Spain). Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:91.

- Horn DJ, Johnston CB. Burnout and self care for palliative care practitioners. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:561–72.

- Wang C, Grassau P, Lawlor PG, Webber C, Bush SH, Gagnon B, et al. Burnout and resilience among Canadian palliative care physicians. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:169.

- Boland JW, Kabir M, Spilg EG, Webber C, Bush SH, Murtagh F, et al. Over a third of palliative medicine physicians meet burnout criteria: results from a survey study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med. 2023;37:343–54.

- Kavalieratos D, Siconolfi DE, Steinhauser KE, Bull J, Arnold RM, Swetz KM, et al. “It’s like heart failure. It’s chronic…and it will kill you”: A qualitative analysis of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:901–10.e1.

- Hardiman O, Van Den Berg LH, Kiernan MC. Clinical diagnosis and management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:639–49.

- Shoesmith C. Palliative care principles in ALS. Handb Clin Neurol. 2023;191:139–55.

- Bromberg MB, Schenkenberg T, Brownell AA. A survey of stress among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis care providers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12:162–7.

- Schellenberg KL, Schofield SJ, Fang S, Johnston WSW. Breaking bad news in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the need for medical education. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15:47–54.

- Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Edis R, Henderson RD, Oliver D, Harris R, et al. Breaking the news of a diagnosis of motor neurone disease: a national survey of neurologists’ perspectives. J Neurol Sci. 2016;367:368–74.

- Hogden A, Greenfield D, Nugus P, Kiernan MC. Engaging in patient decision-making in multidisciplinary care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the views of health professionals. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:691–701.

- Faull C, Haynes CR, Oliver D. Issues for palliative medicine doctors surrounding the withdrawal of non-invasive ventilation at the request of a patient with motor neurone disease: a scoping study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4:43–9.

- Connolly S, Galvin M, Hardiman O. End-of-life management in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Apr 1;14:435–42.

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

- CALS Centres [Internet]. ALS society of Canada. [cited 2023 Jun 23]. Available from: https://als.ca/research/canadian-als-research-network/cals-centres/

- Sinclair VG, Wallston KA. The development and psychometric evaluation of the brief resilient coping scale. Assessment, 2004;11:94–101.

- Croghan IT, Chesak SS, Adusumalli J, Fischer KM, Beck EW, Patel SR, et al. Stress, resilience, and coping of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211008448.

- Collantoni E, Saieva AM, Meregalli V, Girotto C, Carretta G, Boemo DG, et al. Psychological distress, fear of COVID-19, and resilient coping abilities among healthcare workers in a tertiary first-line hospital during the Coronavirus Pandemic. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1465.

- Mache S, Vitzthum K, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA. Evaluation of a multicomponent psychosocial skill training program for Junior physicians in their first year at work: a pilot study. Fam Med. 2015;47:693–8.

- Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, Joos S, Fihn SD, Nelson KM, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:582–7.

- Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20:75–9.

- Kealy D, Halli P, Ogrodniczuk JS, Hadjipavlou G. Burnout among Canadian psychiatry residents: a national survey. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:732–6.

- Yoon JD, Hunt NB, Ravella KC, Jun CS, Curlin FA. Physician burnout and the calling to care for the dying: a national survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34:931–7.

- Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:2.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Mihas P. Qualitative research methods: approaches to qualitative data analysis. In: Tierney RJ, Rizvi F, Ercikan K, edit. International Encyclopedia of Education (Fourth Edition) [Internet]. Oxford: Elsevier; 2023:302–13 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128186305110292

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2018;320:1131–50.

- Smith A. CMA 2021 National Physician Health Survey. 2021.

- Medscape [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 16]. “I Cry but No One Cares”: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058

- Medscape [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 16]. Medscape National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235

- Busis NA, Shanafelt TD, Keran CM, Levin KH, Schwarz HB, Molano JR, et al. Burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology. 2017;88:797–808.

- LaFaver K, Miyasaki JM, Keran CM, Rheaume C, Gulya L, Levin KH, et al. Age and sex differences in burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being in US neurologists. Neurology 2018;91:e1928–41.

- Gleichgerrcht E, Decety J. Empathy in clinical practice: how individual dispositions, gender, and experience moderate empathic concern, burnout, and emotional distress in physicians. PLOS One. 2013;8:e61526.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Nedelec L, et al. Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e209385.

- Hetzel-Riggin MD, Swords BA, Tuang HL, Deck JM, Spurgeon NS. Work engagement and resiliency impact the relationship between nursing stress and burnout. Psychol Rep. 2020;123:1835–53.

- McKinley N, Karayiannis PN, Convie L, Clarke M, Kirk SJ, Campbell WJ. Resilience in medical doctors: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J. 2019;95:140–7.

- Canadian Medical Association [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 23]. CMA National Physician Health Survey: A National Snapshot. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/cma-national-physician-health-survey-national-snapshot

- Waddimba AC, Scribani M, Hasbrouck MA, Krupa N, Jenkins P, May JJ. Resilience among employed physicians and mid-level Practitioners in Upstate New York. Health Serv Res. 2016;51:1706–34.

- Green J, Berdahl CT, Ye X, Wertheimer JC. The impact of positive reinforcement on teamwork climate, resiliency, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: The TEAM-ICU (transforming employee attitudes via messaging strengthens interconnection, communication, and unity) pilot study. J Health Psychol. 2023;28:267–78.

- Olcoń K, Allan J, Fox M, Everingham R, Pai P, Keevers L, et al. A narrative inquiry into the practices of Healthcare Workers’ Wellness Program: The SEED Experience in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:13204.

- McCool N, Reidy J, Steadman S, Nagpal V. The buddy system: an intervention to reduce distress and compassion fatigue and promote resilience on a palliative care team during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2022;18:302–24.