Abstract

Purpose

To describe the development of a new measure of therapeutic relationship for use in physiotherapy – the Physiotherapy Therapeutic RElationship Measure (P-TREM).

Methods

We adopted the methodology of Devellis in Scale Development: Theory and Applications for constructing the P-TREM. We developed a measurement framework based on Miciak’s Physiotherapy Therapeutic Relationship Conceptual Framework. We generated a pool of items by extracting items from existing measures and writing new items. These were reviewed by a panel of experts and then formatted into a draft measurement instrument. The draft instrument was tested for relevancy and comprehensibility in potential respondents from our target populations using cognitive interview techniques. Finally, we pilot tested the full administration of the P-TREM.

Results and conclusions

We systematically constructed the P-TREM with 49 items in 3 subscales. Our rigorous instrument development approach ensures its content validity, which was also demonstrated in the cognitive interviews and pilot testing. The quality of the items and construct validity will be assessed in a subsequent validation study.

Introduction

The relationship between a patient and their physiotherapist can be described as ‘therapeutic’ if a product of the relationship is an improvement in the patient’s well-being. Miciak described ‘therapeutic relationship’ in physiotherapy as encompassing conditions established by the physiotherapist and patient through their intentions towards treatment, ways of connecting during clinical encounters, and the bond that develops between physiotherapist and patient [Citation1].

Research on the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy has mostly been conducted using measurement instruments borrowed or adapted from psychotherapy [Citation2–4]. This allowed researchers to identify associations between therapeutic relationships and intermediate outcomes such as the degree to which the patient engages in physiotherapy treatment, self-efficacy, patient adherence to treatment, as well as biomedical and psychosocial health outcomes such as physical functioning, pain intensity, satisfaction with treatment, depression, and general health status [Citation2,Citation4–7]. Researchers seeking to describe the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy have found that while there are similarities with therapeutic relationship in psychotherapy, there are aspects unique to physiotherapy [Citation8]. Specifically, in physiotherapy, the patient and physiotherapist often connect or relate through the patient’s physical body, including connecting through physical contact (i.e. touch) [Citation9].

A number of validation studies in physiotherapy have identified problems with the measurement properties of these instruments – notably, issues with content validity [Citation4,Citation10–13]. This suggests a need for a discipline-specific measure capturing the elements of therapeutic relationship unique to physiotherapy. Using a measure in physiotherapy research with sound measurement properties, such as content validity, construct validity and reliability, will produce more accurate data. This would also lead to a more precise estimate of therapeutic relationship’s effect on outcomes and improve the validity of research uncovering significant relationships between therapeutic relationship and other variables. Therapeutic relationship is an important aspect of physiotherapy practice. To move research in this area forward, researchers require a high-quality measure of therapeutic relationship, one that is developed based on current knowledge and theory from physiotherapy.

Rigorous instrument development starts with ensuring the content validity of a measure by defining the construct and mapping items to a comprehensive and detailed theoretical measurement framework [Citation14]. Measurement items are constructed carefully so they are comprehensible to potential respondents, interpreted as intended, and relevant to respondent’s experiences of the construct of interest. The COSMIN group describes these concepts as the main criteria of content validity, which is considered the most fundamental consideration in the development of health measures [Citation15,Citation16]. Subsequent phases of instrument development involve administering the instrument to samples of potential respondents to evaluate item quality, construct validity (e.g. structural and convergent validity), reliability and other measurement properties depending on the intended use of the measure [Citation14,Citation16]. This paper describes the initial instrument development process for a new measure of therapeutic relationship: The Physiotherapy Therapeutic RElationship Measure (P-TREM).

Objective

Our objective was to develop a new patient-reported measure of therapeutic relationship for use in populations of patients with musculoskeletal conditions in outpatient physiotherapy settings.

Methods

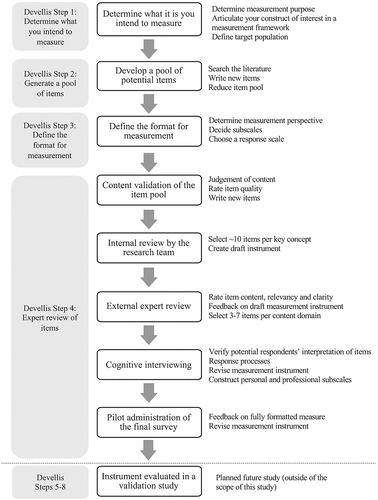

We adopted the methodology of Devellis as described in Scale Development: Theory and Applications for development of the P-TREM: (1) Determine what you intend to measure; (2) Generate a pool of items; (3) Define the format for measurement; (4) Expert review of items; (5) Consider the inclusion of validation items; (6) Administer items to a development sample; (7) Evaluate the items; and (8) Optimise the scale [Citation16]. This 8-step process for measurement scale development was designed for measuring abstract, multifaceted concepts - such as therapeutic relationship [Citation16]. This paper describes the first 4 steps of Devellis’s methods, with showing a flowchart outlining our procedures. Steps 5–8 will be completed in a subsequent study. This study was approved by the University of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Board (Study ID Pro00086206).

Step 1) Determine what you intend to measure

Measurement purpose, intended users, and uses

The P-TREM was developed to capture the strength (i.e. magnitude) and quality (positive or negative) of a therapeutic relationship between a patient and a specific physiotherapist, as developed over multiple encounters in the context of outpatient physiotherapy. The intended users of the P-TREM will be clinical researchers using quantitative methodologies to study therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy for the purposes of discrimination (i.e. to distinguish between different levels of therapeutic relationship quality) and evaluation (i.e. to evaluate change in a therapeutic relationship).

Construct of interest

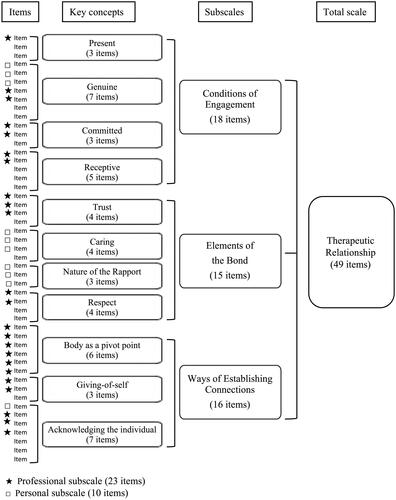

The construct of interest, therapeutic relationship, was articulated as a conceptual measurement framework. The measurement framework guides the systematic development of a measurement instrument [Citation16]. The key concepts in the framework are operationalised through developing items that serve as individual indicators for each concept. We have described the conceptual measurement framework for the P-TREM in detail elsewhere [Citation17]. Briefly, the conceptual foundation of the P-TREM is based on Miciak’s Physiotherapy Therapeutic Relationship Framework [Citation1]. Miciak described the physiotherapy therapeutic relationship as having three main components, each with subcomponents that help to further describe it. The Conditions of engagement - being present, being receptive, being genuine, and being committed - describe the way that the physiotherapist and patient ‘are’ together [Citation18]. Ways of establishing connections are the actions the physiotherapist and patient ‘do’ together that are part of the relationship and include acknowledging the individual, using the body as a pivot point (i.e. physiotherapist and patient connecting through the patient’s body, physiological health condition, or physical symptoms), and giving-of-self [Citation9]. Caring, trust, respect and nature of the rapport make up the Elements of the bond, which are the feelings that exist between the physiotherapist and patient [Citation1]. These components and subcomponents make up the 11 key concepts in the conceptual measurement framework for the P-TREM.

Miciak also identifies personal and professional aspects that underlie all components of the therapeutic relationship [Citation1]. The professional aspects of the therapeutic relationship refer to the main ‘work’ of physiotherapy, in other words, the purpose of the interaction (i.e. rehabilitation) and physiotherapist’s professional role and responsibilities in carrying out rehabilitation [Citation1]. The ‘personal’ aspects of therapeutic relationship refer to the physiotherapist and patient taking an interest in, or caring about, one another in ways that are outside of the specific tasks and goals of rehabilitation [Citation1].

Target population

Adult, English-speaking patients with a condition affecting the musculoskeletal system seen in an outpatient setting (e.g. hospital outpatient, community and private practice clinics).

Step 2) Generate a pool of items

We generated a pool of potential items by searching the current evidence base for existing measurement instruments with potentially relevant items for measuring content domains in our measurement framework. We combined the search results with measurement tools that members of the research team had in their personal collections. The research team’s personal collections included instruments developed for use clinically (e.g. for program evaluation), and some instruments used in research but not published in peer-reviewed literature or which were not located in our search of the literature. Using existing items allowed us to capitalise on work done by previous health measurement researchers in developing and testing high-quality items [Citation19,Citation20]. As recommended by various authors [Citation16,Citation20,Citation21], we also wrote new items to maximise the content coverage of our initial pool of potential items, knowing that the majority of these items would be eliminated in later stages of instrument development.

Literature search and item extraction

The search strategy was developed with the assistance of an experienced health research librarian at the University of Alberta. The search combined two concepts: 1) patient-provider relationship; and 2) measurement. For each concept, we included multiple synonyms and did not apply any search limits. We adapted the search strategy to each database as required, also adding limits or additional concepts to maximise the specificity of the search. Our full search strategy is included as supplemental online material (Supplemental File 1).

One member of the research team (EM) reviewed the citations retrieved in the search and appraised them for relevance. This was done by first screening by title and abstract, then reviewing full texts. A second reviewer was available for consultation when relevance was unclear (MM). An article was considered relevant if it contained a measurement instrument for our construct of interest or a related term (e.g. therapeutic alliance, trust, empathy, communication, working alliance), if it was a self-report measure developed or tested for use in an adult, English speaking patient population, with any type of healthcare provider (e.g. psychotherapy, allied health, nursing), in clinical practice, research or health service evaluation. Although there are differences across disciplines, there is also significant overlap, so measures from all disciplines and measures of related constructs were included. We thought these measures may contain individual items that are relevant to the physiotherapy therapeutic relationship. Articles were excluded if they described a measure for a paediatric population, or if the instrument was a behaviour coding system, an observer rating scale, or an interview system.

The full versions of each measurement instrument identified in the relevant articles were retrieved. One researcher (EM) extracted the items from the search and researcher’s collections into an item database. We then added the newly written items to the database of potential items.

Reducing the item database

The item database was reviewed by one researcher (EM). The number of items in the item database was reduced by removing items that were: (1) not relevant to the construct of interest, (2) semantically redundant with other items, and/or (3) poorly written (i.e. not comprehensible, contained more than one concept, ambiguous interpretability). Items were also rewritten during this process so that they were standardised in terms of perspective (patient-reported, first person), response format (6-point agreement scale), verb tense (present), and linguistic style. Then, the content of the remaining items was coded in NVivo 12 software [Citation22] using 43 pre-determined codes based on the indicators from the measurement framework. The codes were used to group items by content area, allowing us to more closely examine each content grouping for relevancy of the item to the content area, and to identify redundancies between items. We also identified gaps in content coverage during this process and wrote new items to help fill those gaps.

Step 3) Define the format for measurement

The P-TREM was developed with the intent of having 3 subscales, each reflecting a component in Miciak’s Framework (i.e. conditions, connections, bond). Additionally, through the item review process, a set of items was determined to be ‘personal’ and another set of items was intended to measure the ‘professional’. We thought it was important to capture the personal versus professional aspects of therapeutic relationship because these concepts have not been explicitly studied in physiotherapy research. The items have a 6-point ordinal response scale (Likert-type) ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. In order for each key concept to be fully represented in the measure, each key concept has 3–7 items.

Step 4) Expert review of items

The item review process was iterative – that is, as the review process unfolded, we cycled between collecting and analysing data from reviewers, revising the items, and modifying the format and organisation of the P-TREM. This has been shown to increase the efficiency of collecting new data from subsequent reviewers [Citation15]. For example, we made changes to the items based on responses from 2 reviewers prior to sending the items to subsequent reviewers. There were 5 cycles of expert review which are outlined in : (1) content validation of the item pool; (2) internal review by the research team; (3) external expert review; (4) cognitive interviewing; and (5) pilot administration of the final survey. Throughout analysis, we took care to preserve the content coverage of the items.

1. Content validation of the item pool: The main purpose of this step was to verify the content that the items represent. A secondary aim was to refine the item pool by identifying and then either eliminating or rewriting poorly worded or irrelevant items. Four clinical researchers (herein, ‘judges’) – all licenced physiotherapists – who were familiar with Miciak’s Framework performed the content validation. Judges received items that were grouped by content area (i.e. by concept from the measurement framework). They rated the relevancy of the items to that concept using a 4-point rating scale (with anchors: 1 = ‘Not at all relevant’, to 4 = ‘Very relevant’), rated the clarity of each item (clear/unclear), identified the items they considered redundant within the grouping, and to write new items to cover concepts they felt were missing. Judges also judged each item as either assessing a ‘personal’ or ‘professional’ aspect of therapeutic relationship, which contributed to the creation of the professional and personal subscales in the P-TREM.

One researcher (EM) collated data from the content validation forms by item and refined the item pool. Items were eliminated if they were considered redundant by 2 or more judges. Items with a low relevancy rating (1–2 on the 4-point scale) or with a recommendation to eliminate by 2 or more judges were either re-categorized to a more appropriate content area or eliminated. If there was a lack of consensus among judges, the item was retained for review by the full research team.

2. Internal review by the research team: Four members of the research team reviewed the item pool after the content validation with the aim of selecting the most appropriate items and drafting the P-TREM questionnaire. Two researchers (EM, MM) independently ranked the items in each content area by considering relevancy and comprehensibility of each item. Next, they collaboratively used their item rankings and comments from the content judges to select the best 5–10 items per concept for the first draft of the measure. In selecting items, the first priority was to preserve the content coverage of the concept. The third researcher (MRR) reviewed their work. Similar to content judges, the three members of the research team judged an item as either ‘personal’ or ‘professional’. The selected items were formatted into the first draft of the P-TREM, which was reviewed by the fourth researcher (HS).

3. External expert review: The purpose of the expert review process was to have subject matter experts external to the research team (clinicians, patients, clinical researchers) review the items in the draft P-TREM. Expert reviewers were recruited through the professional networks of the research team and through a patient advocacy group. In a process similar to the internal review, external reviewers were asked to rate and/or comment on each P-TREM item with respect to: 1) relevancy to their experience of the physiotherapy therapeutic relationship, 2) clarity, 3) redundancy with other items. They were also asked 3 questions designed to assess the comprehensiveness of the content overall (i.e. were there any items missing), the clarity of the instructions for completing the questionnaire, and the structure and flow of the questionnaire.

The median and mean item relevancy rating and the proportion of ‘not easy to understand’ were calculated for each item. This information, in addition to the review comments on items, was considered when revising the P-TREM draft. Items with a low relevancy score (below 3.6 out of 4) were eliminated (or modified if the item was necessary to maintain content coverage), and items rated by one or more reviewers as ‘not easy to understand’ but with a high relevancy score (3.6+) were modified to improve clarity. If items were identified as redundant by 2 or more reviewers, we eliminated the item with the lowest relevancy score, or if relevancy score was the same, the items with the simpler wording was retained.

4. Cognitive interviewing: We used cognitive interviewing to verify that the items in the P-TREM were relevant, easily understood and answerable, and that the questionnaire instructions were easy to interpret and follow [Citation23].

We recruited participants through the research team and expert reviewers’ networks, from three patient populations: inherited bleeding disorders (e.g. haemophilia), inflammatory arthritis (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis), and individuals seeking physiotherapy care in private practice for any musculoskeletal condition. These populations were chosen based on the intended use of the instrument in future research. Individuals were eligible for participation if they were 16 years of age or older and had at least 3 encounters with the same physiotherapist in the past 3 years in an ambulatory setting.

We aimed for representation in our sample by recruiting a cross-section of our target population, in order to identify a wide range of problems in the items [Citation23]. We focussed on representing variability in age, gender, education level, diagnosis, and individuals whose first language was not English.

Interview procedures

As recommended by Willis (2011), the interviewer used a ‘mixed approach’ including ‘Think-Aloud’ (i.e. participant vocalises their thoughts while reading and responding to the item) and verbal probing (i.e. interviewer asks follow-up questions based on observations of specific behaviours or to further examine respondent’s thinking processes) [Citation23]. A debriefing question was used to elicit opinions about the measure [Citation23].

The lead researcher (EM) conducted the cognitive interviews in-person or using teleconferencing technology. Interviews lasted 35–55 min. The interviewer took notes throughout the interview, wrote field notes after the interview, and all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Recruitment continued until no new information was forthcoming.

Analysis of interview data

After each interview, the transcripts and notes were reviewed, and participants’ comments were collated by item. New findings were compared to the data from previous participants. When it became clear that an item was not functioning well (i.e. being misinterpreted, difficult to answer, or redundant), the item was eliminated or rewritten/replaced with another item assessing the same content. When items were identified as redundant, the decision on which item to eliminate was based on discussion between two members of the research team.

Constructing personal and professional subscales in the P-TREM

At the content validation and internal review stages, 7 reviewers were asked to judge the content of each item as ‘personal’ or ‘professional’. Data from the reviewers were analysed for the 49 items in the final version of the P-TREM. An item was included in the personal or professional item subset if 85% or more of reviewers judged it as personal/professional. These items do not represent unique content, rather they overlap with the items representing the key concepts in the physiotherapy therapeutic relationship framework.

5. Pilot administration of the final survey: The purpose of this step was to test a fully operational survey (online and paper-pencil versions) that would be used in a subsequent validation study. Participants for the pilot administration were recruited in the same way as those participating in the cognitive interviews. Participants completed the survey as if they were participants in a research study. We solicited written feedback on each set of questions, and on the survey as a whole (focusing on clarity of the instructions, layout of the questions, length of the survey, and usability of the online system or paper form). Iterative changes were made to the item wording, layout, format, and organisation of the items as feedback was received. The survey was pilot tested until no new revisions were suggested.

Results

Generate a pool of items

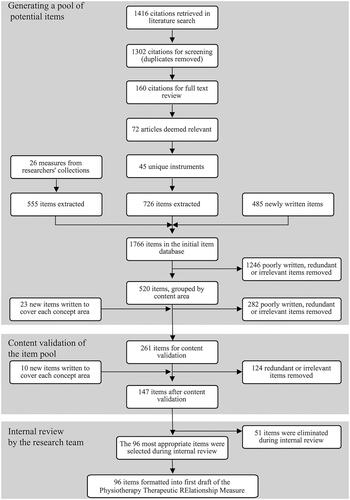

In the database search, we retrieved 1,416 citations, with 160 articles remaining after screening titles and abstracts, and 72 deemed relevant in the full text review. From those articles, we extracted 45 relevant measurement instruments, which were combined with 26 measures from the researchers’ personal collections. We extracted 1,281 items from those measures, which were added to the 485 new items written by members of the research team. The initial item database was reduced to 261 items after examining items within each content grouping. is a flow diagram illustrating the results of the generation of an item pool, content validation of the item pool, and the internal review by the research team steps.

Content validation of the item pool

Through the content validation process, 124 items were eliminated, 10 new items were written, 68 items were rewritten, and 63 items were retained without modification. The final item pool contained 147 items.

Internal review

The two researchers (EM, MM) eliminated 50 items (13 conditions items, 26 connections items, and 11 bond items), another 1 item was eliminated based on the recommendations of the third researcher (MRR) with 96 items retained.

External expert review

Five experts (2 physiotherapists, 3 patients) reviewed the first draft of the P-TREM. External expert reviewers are described in .

Table 1. External expert reviewer summary of demographics (n = 5).

During external expert review, changes were made to 3 areas: the instructions, the terminology, and the items’ wording. The instructions for completing the P-TREM were modified to clarify that the questionnaire focuses on the relationship with one specific physiotherapist (e.g. think about one particular physiotherapist that you have worked with as you answer the questions). We identified a need to change some of the terminology used in the items to make the questions more generalisable across patient experiences. For example, it was pointed out that ‘recovery’ in the item, My physiotherapist helps me feel hopeful about my recovery, may not be relevant for people with chronic conditions, so ‘recovery’ was replaced by ‘future health’. Similarly, not all patients would identify with seeing a physiotherapist for an ‘injury’, and ‘problem’ was seen by reviewers as potentially too vague. To address this, we decided that the term ‘injury or condition’ would be used in items like, ‘I am comfortable asking my physiotherapist questions about my injury or condition.’ In terms of changes to the items in the P-TREM, 38 were eliminated, 16 were modified, and 42 items were retained without changes. One new item was added to reflect a concept that 2 reviewers felt was important: availability of the physiotherapist outside of their appointment times. After expert review, there were 59 items in the subsequent draft of the P-TREM.

Cognitive interviewing

We completed cognitive interviews with 9 participants. Three were conducted in-person, and six using teleconferencing technology. The cognitive interview participants are described in .

Table 2. Cognitive interview participant demographics (n = 9).

After the first six cognitive interviews, 21 items were modified (primarily to improve interpretability) and 12 items were eliminated (primarily because of redundant content). Two items were added because they covered topics that were suggested as missing by 2 interview participants. Minor changes were made to the P-TREM instructions. It was found that more complex items were easier for participants to understand when they followed simpler items that tap into similar concepts; therefore items were reordered to reduce cognitive load for respondents.

Following the first 6 interviews, the content of the P-TREM items was re-assessed to verify there were 3–7 items per key concept from the measurement framework. We found four concepts that required an additional item to be written: respect, being present, giving of self, and caring. Two more interviews were conducted, where 4 items were eliminated because of redundant content. There were 49 items in the P-TREM when the final interview was conducted, and no changes to the items was deemed necessary.

Pilot administration

Participants (n = 5) in the pilot administration are described in . After pilot administration, two items in the P-TREM were returned to a previous iteration of that item because of difficulties with interpretation of the newer item. It became clear that some participants had a strong preference for items assessing either the personal or the professional aspects of therapeutic relationship, which could have an impact on drop-out and non-response to certain items. Therefore, we added a statement to the P-TREM instructions, ‘not all items will be relevant to your relationship, but please answer them as best you can’, and also added a single demographics question to assess respondent’s preference for ‘friendliness’ in their relationship with their physiotherapist.

Table 3. Pilot administration participant demographics (n = 5).

Constructing personal and professional subscales in the P-TREM

In the final questionnaire, 10 items were designated as part of a ‘personal’ subscale, and 23 items were designated as ‘professional’. For the other 16 items, there was no consensus as to whether it assessed a personal or professional aspect.

The final version of the P-TREM has 49 items. shows the measurement framework for the P-TREM, as well as the final distribution of items per key concept in the measurement framework. The final item list for the P-TREM is available as supplemental online material (Supplemental File 2).

Discussion

We described the first phase of a rigorous instrument development process for a new measure of therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy. The conceptual basis for the P-TREM is a comprehensive, detailed, theoretical model of therapeutic relationship, developed through qualitative research involving patients with musculoskeletal conditions and physiotherapists. The careful construction of our instrument ensures the content validity of the P-TREM, which is essential to establish before other measurement properties can be evaluated [Citation14,Citation15]. To our knowledge, the P-TREM is the first English-language measure based on a discipline-specific model of therapeutic relationship. There has been one other measure developed based on a discipline-specific model of person-centred therapeutic relationships (PCTR-PT) using similar methodologies [Citation24,Citation25]. It was constructed to have four dimensions ‘Relational Bond’, ‘Individualized Partnership’, ‘Professional Empowerment’, and ‘Therapeutic Communication’, and all have good internal consistency (co-efficient alpha values between .86 and .91) [Citation25]. While the ceiling effects for the total scale were not reported, the individual items all showed ceiling effects, a common issue in measures of relational constructs (e.g. working alliance, patient satisfaction) [Citation25]. The content of the PCTR-PT scale shares many similarities with the P-TREM [Citation24]. The main difference is inclusion of elements in the PCTR-PT such as the environment and individual qualities of the physiotherapist, which we would conceptualise as factors influencing the therapeutic relationship. Also, the contribution of the patient to the therapeutic relationship is not recognised in the PCTR-PT, nor is the physiotherapist’s use of touch, or the focus on the patient’s body. Additionally, the PCTR-PT scale was developed and evaluated in Spanish, and the cross-cultural validity of an English translation has not been examined.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are that we have developed a measurement instrument based on a sound conceptual understanding of our construct of interest and used rigorous methods to ensure that the P-TREM items represent the concepts in therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy. A limitation of the study is the variability represented in our sample of participants in the item review stages. We desired greater variability than we achieved in participant’s education levels (most participants had a post-secondary diploma or degree) to more closely represent our target population. However, we were reassured by our strategy of collecting data until no new information was forthcoming and by the representation of individuals in other characteristics (English as an additional language, age, gender, diagnosis).

Future directions

Since this is the first phase of instrument development (steps 1–4 of Devellis’s methodology for developing measurement instruments) [Citation12], a subsequent validation study is needed and is underway. We will examine the quality of the items using techniques from classical test theory and item response theory. Construct validity will be studied by looking at concurrent and convergent validity, as well as internal scaling structure. We will also examine the patterns of responses to the items to see if they differ by subgroups of the patients’ sample (e.g. gender, condition, clinical setting). Although we have included the P-TREM measure as a supplemental material in this article (Supplemental File 2), the validity of the P-TREM has not yet been established. Therefore, at this stage, it should not be considered ready to use to capture the quality and magnitude of therapeutic relationship in clinical research.

Conclusions

We describe the development of a new measure of the physiotherapy therapeutic relationship and steps taken to ensure its content validity. A valid measure will help physiotherapy researchers understand therapeutic relationship and how it impacts treatment outcomes. In turn, this could improve effectiveness of physiotherapy encounters and interventions.

Supplemental_File_2_P-TREM.pdf

Download PDF (196 KB)Supplemental_File_1_Full_search_strategy.pdf

Download PDF (86.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients and clinicians who dedicated their time to this project as expert reviewers.

Disclosure statement

The authors of this manuscript report no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Miciak M. Bedside matters: a conceptual framework of the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy [Internet] [doctor of philosophy]. Edmonton (Canada): University of Alberta; 2015. Available from: https://era.library.ualberta.ca/files/9z903246q#.WEWHhmQrIfE.

- Babatunde F, MacDermid J, MacIntyre N. Characteristics of therapeutic alliance in musculoskeletal physiotherapy and occupational therapy practice: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):23.

- Besley J, Kayes MN, McPherson MK. Assessing therapeutic relationships in physiotherapy: literature review. N Z J Physiother. 2011;39(2):81–91.

- Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Human technologies in rehabilitation: 'who' and 'how' we are with our clients. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(22):1907–1911.

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(8):1099–1110.

- Kinney M, Seider J, Beaty AF, et al. The impact of therapeutic alliance in physical therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36(8):886–898.

- Taccolini Manzoni AC, Bastos de Oliveira NT, Nunes Cabral CM, et al. The role of the therapeutic alliance on pain relief in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;34(12):901–915.

- McCabe E, Miciak M, Dennett L, et al. Measuring therapeutic relationship in the care of patients with haemophilia: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1208–1223.

- Miciak M, Mayan M, Brown C, et al. A framework for establishing connections in physiotherapy practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(1):40–56.

- Araujo AC, Filho RN, Oliveira CB, et al. Measurement properties of the Brazilian version of the Working Alliance Inventory (patient and therapist short-forms) and Session Rating Scale for low back pain. BMR. 2017;30(4):879–887.

- Besley J, Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Assessing the measurement properties of two commonly used measures of therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy. N Z J Physiother. 2011;39(1):75–80.

- Hall AM, Ferreira ML, Clemson L, et al. Assessment of the therapeutic alliance in physical rehabilitation: a RASCH analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(3):257–266.

- Paap D, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory Dutch version for use in rehabilitation setting. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(12):1292–1303.

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. 4th ed. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications Inc.; 2017. p. 262.

- Prinsen C, Mokkink L, Bouter L, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1147–1129.

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018; 27(5):1159–1170.

- McCabe E, Miciak M, Roduta Roberts M, et al. Measuring therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: conceptual foundations. (Manuscript submitted for publication). University of Alberta, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine; 2020.

- Miciak M, Mayan M, Brown C, et al. The necessary conditions of engagement for the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: an interpretive description study. Arch Physiother. 2018;8(1):3.

- Dewalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, et al. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S12–S21.

- Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 5th ed. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 399.

- Johnson GB, Morgan RL. Survey scales: a guide to development, analysis, and reporting. 1st ed. New York (NY): The Guilford Press; 2016. p. 269.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo [Internet]. QRS International; 2018. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2011.

- Rodriguez Nogueira O, Botella-Rico J, Martinez Gonzalez MC, et al. Construction and content validation of a measurement tool to evaluate person-centered therapeutic relationships in physiotherapy services. Tu W-J, editor. PLOS One. 2020;15(3):e0228916.

- Rodriguez-Nogueira Ó, Morera Balaguer J, Nogueira López A, et al. The psychometric properties of the person-centered therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy scale. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241010.