ABSTRACT

Development of water infrastructure is conventionally prioritised as a pre-emptive intervention policy to address water challenges. In the Vietnamese Mekong Delta, turning a river into a reservoir is touted as a ‘highly-modernist’ water management approach to secure the year-round supply of freshwater for agricultural production. This paper investigates how contested water-livelihood relations emerged from the building of the Ba Lai sluice scheme in Ben Tre Province, and how these processes demonstrate farmers’ agency in everyday politics in seeking solutions for livelihood sustainability. Drawing on a qualitative case study in Binh Dai District, we argue that, while the scheme successfully fulfils the state’s political intention in securing water supply for freshwater-based crop production in coastal zones, it generates contestation between the local government’s attempts to enforce freshwater policies and farmers’ agency in maintaining productive livelihoods. The findings suggest that power asymmetries are embedded within these water-livelihood relations. We find that seeking just solutions that have co-benefits for water management and livelihood sustainability should go beyond business-as-usual water politics by adequately recognising the agency of farmers in sustainable development. The case study offers lessons for navigating the sustainable future of water development projects in coastal deltas and beyond.

Introduction

Coastal areas in global tropical deltas are at the forefront of climate change and institutional preferences in infrastructural development to deal with climatic impacts and human development (Nicholls et al. Citation2020; Tortajada Citation2014). While saltwater intrusion and sea level rise are seen as major threats in these areas (Eslami et al. Citation2021; Hinkel et al. Citation2018; Rahman et al. Citation2019; Szabo et al. Citation2016), human interventions with infrastructure (e.g. sea dikes or sluice gates) for agriculture-led development can contribute to aggravating these existing problems. Together these put substantial strain on coastal ecosystems and the large number of people whose livelihoods depend on these resources (Hill Citation2015; Hoitink et al. Citation2020). While such anthropogenic appropriations of nature have substantially ruptured human-nature relations (Mahanty et al. Citation2023), there remains a gap in the understanding of how these contribute to contestations between water management and options for productive livelihoods.

Unequal social relations are demonstrated in historical accounts of exploiting the Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD) for development (Tran Citation2020). They play an important role in determining how nature is transformed and who exploits resources (Kemerink et al. Citation2016). The ‘taming’ of the delta’s natural systems entailed significant efforts by state administrations in reclaiming lands for the expansion of cultivated areas, irrigation systems, and human settlements (D. A. Biggs Citation2010; Käkönen Citation2008). These represent ‘technocratisation’, where top-down management policies prioritise technical solutions in water management (Bruun and Rubin Citation2023). Efforts to deal with water challenges in the VMD have seen the move from open floodplains to infrastructure for flood control, and on the coastal plains, levees, and sluices to tackle escalating processes of saltwater intrusion and sea level rise (Tran and Tortajada Citation2022). Currently, the delta possesses a wide range of water infrastructure systems including dikes (low dikes, high dikes) and lateral canals in the floodplains, as well as sea dikes and sluices in the coastal zones.

Water infrastructure continues to be utilised as a dominant tool by governments to respond to demands for development and climate change adaptation (Crow-Miller, Webber, and Molle Citation2017). It is seen as a form of power that aims to translate their political will into policies to be exercised on the ground (Meehan Citation2014; Nygren Citation2021). In the coastal zones of the VMD, the national government’s intervention into the coastal ecosystems has been undertaken by sealing off the riverine estuaries with sluices to prevent saltwater intrusion and concomitantly retain freshwater for agricultural production (Tran and Cook Citation2023). This water infrastructure development, while it attempts to fulfil the state’s mandates in climate change adaptation, has aggravated the livelihoods of some farming communities, who seek to pursue traditional livelihood practices (e.g. shrimp farming) (Tran et al. Citation2022). While these policy-practice contestations come to the fore, little is known about how farmers’ agency is expressed in their everyday politics in response to the consequences of the water infrastructure and the associated power utilised by the local governments.

In this paper, we investigate how farmers’ agency is defined, and how it is linked to their capacity to react to water management policies. Drawing on a qualitative case study in Binh Dai District, we argue that the Ba Lai sluice scheme successfully fulfils the state’s political intention in guaranteeing water supply for ‘homogenising’ freshwater-based crop production in the coastal zone. We further argue that the farmers have keenly exercised their agency and contested the government policies to sustain productive livelihoods. In this light, the paper makes a three-fold contribution. First, it demonstrates the drawbacks of water infrastructure for profitable and sustainable rural livelihoods in the contemporary authoritarian governance system. Second, it assesses the significance of the everyday political strategies deployed by local farmers in contesting the ‘patronage’ water governance system. The Ba Lai case study explores local farmers’ agency in challenging the authoritarian system in efforts to defend their rights, values, and interest. At the delta scale, these insights may inform strategies for enhancing climate-resilient and sustainable development agenda guided by Resolution 120Footnote1 of the Vietnamese Government (GoV Citation2017). Third, the paper engages with discussions on how water infrastructure shapes livelihoods in coastal deltas. In particular, we explore how farmers seek justice to ensure the sustainability of their livelihoods while adapting to the compounding impacts of climate change and infrastructural development.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section conceptualises everyday politics and agency towards livelihood sustainability. In the research methods section, we present the case study description and strategies for data collection and analysis. The results and discussion section focuses on four key themes, including the dark sides of a simplistic water management approach, power asymmetries through water-livelihood contestations, farmers’ agency in their everyday politics of adaptation to environmental change, and efforts to seek just solutions for livelihood sustainability. The paper concludes with policy recommendations for harmonising trade-offs between water management and livelihood sustainability in coastal deltas.

Conceptualisation of everyday politics

Everyday politics is a well-established focus in the literature of environmental politics. It is salient in contested state-society relations, especially under the administrations of authoritarian countries (Ortmann Citation2017), where high-level government bodies have the authority to control power, decision-making, and resources (Le, Tran, and Rola-Rubzen Citation2023). Everyday politics is defined as the efforts of subordinate groups in engaging in subtle, non-confrontational resistance to secure de facto gains (Kerkvliet Citation2005; Scott Citation1998). Small-scale activities can constitute a form of collective actions, which are commonly employed by lower classes to demonstrate their political interests. In other words, everyday politics can be a form of collective action and political expression (Lindegaard and Sen Citation2022).

When people are vulnerable or become powerless, they may sublimate their discontent into everyday politics (Dang Citation2010). Everyday politics has occurred in the contemporary contexts of climate change adaptation, environmental governance, and development in authoritarian countries. In the case of Vietnam, everyday politics has been exhibited in the interplay between formal adaptation interventions (led by external actors) and everyday adaptation strategies (led by local actors). Kerkvliet (Citation2005) showed how everyday politics was engaged with the processes of building and dismantling of collective farming in northern Vietnam. Meanwhile, everyday politics as seen through the post-1975 agrarian reform in southern Vietnam illuminates how collective actions led by farmers resulted in modifications to national agrarian policies (Dang Citation2018). There is limited knowledge, however, of how everyday politics takes place in the interface between water management and livelihoods, which has evolved as a key issue in the quest for sustainable development in the VMD.

The concept of everyday politics is applied in this research to investigate how the local government and coastal farming communities have contested water management and livelihood policies. Drawing on the case study of the Ba Lai sluice system, we explore how the local government’s water management policies (freshening the coastal zones) are at odds with the local environments on which farmers have traditionally depended to produce profitable livelihoods, such as shrimp farming. Using the concept of everyday politics, we also highlight how farming communities in the case study areas exercise their agency in defending their rights for shrimp farming while seeking legitimacy for sustainable livelihood solutions in the broader context of the delta’s coastal zones.

Local agency towards livelihood sustainability

Agency is defined as the capacity of individuals or groups to make choices based on their values and to exercise those choices to realise their goals (Brown and Westaway Citation2011; Manlosa, Albrecht, and Riechers Citation2023). According to Kabeer (Citation1999), agency can be operationalised as ‘decision-making’ or takes the forms of bargaining, negotiation, subversion, and resistance, which can be exercised by individuals or collectives. From the perspective of agency, humans have ‘the capacity, both cognitively and through the use of instrumentation, to perceive changes at a larger scale’ (Davidson Citation2010, 1144). While engaging collectively in resource management, they can re-negotiate norms, challenge inequalities, claim rights and extend access (Cleaver Citation2007).

Agency plays an instrumental role in sustainable livelihoods, involving power and politics in relation to people, their capabilities, and their means of living (Mishra et al. Citation2023; Scoones Citation2009). From the bottom-up perspective, as Manlosa (Citation2022) puts it, sustainable livelihoods imply not only the material outcomes that meet people’s demands, but also the capacity that enables the agency of those who undertake it. In pursuit of sustainable livelihoods, humans are not passive victims to socio-political trends and environmental changes (Brown and Westaway Citation2011).

This study examines how local farmers’ agency is exercised in the everyday politics of pursuing livelihood sustainability. From the view of agency, this is concerned with ways in which farmers challenge the status quo of modernised water management (large-scale infrastructure-based water management), while gaining legitimate access to water resources (brackish/saline water) for shrimp farming. In practical terms, it entails how farmers undertook various strategies to deal with water management rules that conflict with their livelihood priorities.

Research methods

Description of the case study

A qualitative case study was employed to investigate everyday politics of adaptation exercised by agrarian communities in Binh Dai District, Ben Tre Province, Vietnam. The province is severely affected by saltwater intrusion (Tran et al. Citation2022; Veettil, Quang, and Trang Citation2019), which is seen as a ‘wicked’ problem that needs to be tackled (Ben Tre People’s Committee Citation2016). Through the Ba Lai case study, we examine how the governments at district and communal levels exercise the ‘freshening the coastal zones’ policy, and how it conflicts with farmers’ aspirations for livelihood security. In the broader context, these contested relations show how the authoritarian governance approach in Vietnam (Bruun Citation2020; Le, Tran, and Rola-Rubzen Citation2023), where a command-and-control regulatory framework is predominantly adopted in water management, comes at odds with local livelihood dynamics in times of climate change.

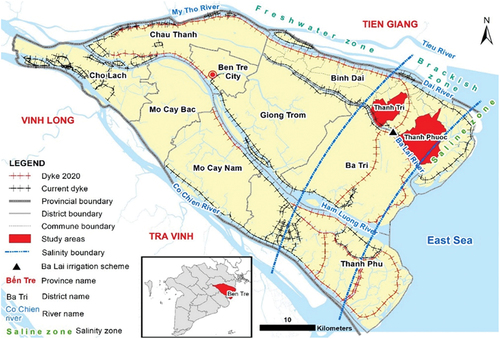

The Ba Lai sluice scheme is part of the North Ben Tre water control project, which aims to secure the year-round freshwater supply for Ben Tre City and four surrounding districts, including Chau Thanh, Binh Dai, Giong Trom, and Ba Tri, as well as prevent saltwater intrusion in coastal zones (Ben Tre People’s Committee Citation2016; Hoang et al. Citation2009). This involved the conversion of the Ba Lai River into a freshwater reservoir to meet these dual needs (). Geographically, the scheme demarcates two distinct agro-ecological zones: the freshwater zone in the upper river, and the brackish/saline zone at the river estuary.

Figure 1. The map of Ben Tre Province and the study areas: Thanh Tri and Thanh phuoc communes (in red shades) in Binh Dai District. Source: adapted from Tran et al. (Citation2022).

Two communes, namely Thanh Tri and Thanh Phuoc, in Binh Dai District were selected for the study. The communes share a border with the Ba Lai River. Thanh Tri is located in the upstream freshwater zone, whereas Thanh Phuoc is in the downstream estuary zone (see ). Endowed with abundant freshwater resources provided by the Ba Lai scheme, Thanh Tri Commune has a larger agricultural land area (1,112 ha). This allows local farmers to ‘homogenise’ their crop systems by cultivating rice, sugarcane, bananas, and fruits on a wider scale. Compared with its counterpart, Thanh Phuoc Commune has a larger aquacultural land area (of nearly 3,000 ha) endowed with a year-round saline environment. In this commune, farmers engage in a variety of livelihood activities, including seasonal cash crop farming (e.g. peanuts and pumpkins), wild fish capture, as well as coastal aquacultural production (e.g. shrimp farming) ().

Table 1. Description of the study areas.

Data collection and analysis

Informed by the narrative inquiry strategy (Paschen and Ison Citation2014), focus group discussions (FGDs) and interviews were applied as the primary methods for data collection (). The recruitment of participants in FGDs targeted three groups of farmers (poor, medium, and better-off) in Thanh Tri and Thanh Phuoc communes. Demographic information from the local government based on existing wealth ranking criteria was used to inform participant selection (Ha et al. Citation2013). For instance, poor households were landless or held little land (<0.5 ha), mainly dependent on seasonal wage labour or wild fisheries capture. The medium group often owned 0.5–3 ha of land with main sources of income derived from on-farm and off-farm labour; and the better-off group had more than 3 ha of land with income-generating activities in farming or commercial businesses.

Table 2. Summary of qualitative data collection.

FGD participants was recruited based upon pre-determined attributes, namely that they: (1) had long-term residency in the commune (i.e. before construction of the Ba Lai irrigation scheme), (2) had extensive experience/interactions with saltwater intrusion, and (3) engaged in occupations associated with agriculture or aquaculture. A total of 33 local residents participated in the FGDs; these included: 14 from Thanh Tri Commune and 19 from Thanh Phuoc Commune participated in the FGDs. Both male and female participants were involved in the FGDs, which were facilitated by the first author. The average age of participants was 52 in Thanh Tri and 57 in Thanh Phuoc. During the FGDs, the facilitator maintained fair contributions from male and female participants in discussing the research topics.

A total of 12 interviews were undertaken with key informants (). The informants included individuals and research and government institutions across multiple levels of administration. Semi-structured questions aimed to gather the respondent’s perspectives of various dimensions of the issues under study, including implications of the Ba Lai sluice systems for local livelihoods (both upstream and downstream zones), impacts of saltwater intrusion, and farmer-led responses/decisions to address environmental change.

A literature review of books, journal articles, government policy documents, as well as local and international newspaper articles was conducted to help interpret the primary data (FGDs and interviews). The literature contributed to gaining the contextual understanding of the case study, guiding strategies for qualitative data collection and analysis, as well as assisting the discussion of the study findings.

Qualitative data were collected from April to June of 2019. All FGDs and most interviews were conducted face-to-face with local respondents, with one expert interview undertaken over Zoom in July 2021. Overall, the interviews lasted between one and two hours. They were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Storytelling is an approach to portray respondents’ stories associated with their lived experiences in dealing with challenges (Ettinger, Otto, and Schipper Citation2021), and to provide useful ways to communicate with audiences and sources of data (Klenk Citation2018). Analysis was assisted by Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2007) coding strategies, which include three phases of coding: open, axial, and selective coding. These coding processes were also adopted by Miani et al. (Citation2023) and described in detail in a study on rural livelihoods in Afghanistan. In addition, the integrated deductive (top-down) and inductive (bottom-up) coding approaches, which were guided by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, were applied (Citation2006). These two approaches allowed a more in-depth analysis of the data. NVivo software (version 12) was used for coding and data analysis.

Results and discussion

Side effects of simplistic management

Coastal plains of the VMD are at the forefront of climate change impacts, triggering demands for the state to invest in water infrastructure to tackle the problem. In support of the agriculture-led growth policies, freshwater is seen as the most vital resource that contributes to the improved well-being and livelihoods of agrarian coastal communities. This was marked by the launch of the ‘rice everywhere’ campaign spearheaded by the national government in attempts to convert the coastal plains of the VMD into permanent freshwater zones for rice production (D. Biggs et al. Citation2009). These were known as the ‘freshening coastal zones’ policies (Tran et al. Citation2022).

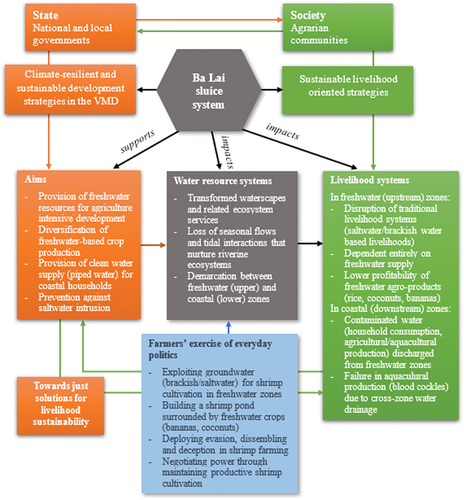

The agriculture-led development policies in the coastal zones enabled the implementation of two ‘experiments’ of ‘freshening coastal zones’ through large-scale infrastructure. The first one was undertaken in the Ca Mau Peninsula during the 1990s. It attempted to convert large swampy wetland areas into freshwater zones (Benedikter Citation2014). For this first attempt, the newly created freshwater zones allowed the cultivation of two or three rice crops per year (Gowing et al. Citation2006). The second (extended) experiment involved high-tech modifications of the delta’s coastalscapes, where rivers (such as the Ba Lai River) were converted into reservoirs to store freshwater against the effects of saltwater intrusion (Tran et al. Citation2022). This experiment demonstrates the Vietnamese Government’s extensive use of water infrastructure as a key instrument to meet their political needs, namely enhancing national food security and rice exports (D. Biggs et al. Citation2009) ().

Figure 2. The Ba lai sluice scheme amidst water-livelihood contestations. Source: illustration by the first author.

However, this simplistic water development approach has had perverse impacts, in particular, resulting in the transformation of coastal ecosystems from brackish/saline to freshwater environments. This disrupted the diversity of coastal brackish and saline ecosystems which help sustain the traditional livelihoods of coastal communities (Hoanh et al. Citation2003). The impoundment of the riverine estuaries by the Ba Lai scheme hampers the natural tidal flows which are essentially vital for the health of the river and the coastal ecosystems (e.g. coastal wild fisheries), including the habitats of brackish aquatic species (Tran et al. Citation2022). The loss of the estuarine ecosystems disrupts the conventional aquacultural production, such as blood cockles in this study, as well as wild fisheries capture which provide important sources of incomes for coastal fishing communities (Fabinyi et al. Citation2022). These accounts are consistent with Molle et al.’s (Citation2009, 328) view that ‘infrastructural development has often become an end in itself, rather than a means to an end, fuelling rent-seeking and symbolising state power.’

The Ba Lai sluice scheme has trans-zone water impacts. This was evidenced by the discharge of water resources across the ecological zones (from freshwater (upstream) to and salinity (downstream) zones), creating a new form of vulnerability to agrarian communities living in the latter. Our data provide the evidence of how water drainage from the upstream (freshwater) zones through the sluice gate put the livelihoods of farmers in Thanh Phuoc Commune at risk. Abrupt freshwater drainage changed water conditions in the estuary zones, resulting in the failure of blood cockle cultivation. While the freshwater drainage schedule was fixed (twice a month), it was contingent on water dynamics in the upstream zones. Recalling an abnormal freshwater drainage event in 2018, a farmer attributed the loss of his blood cockle crop to the extended drainage of freshwater (about 10 days) onto his farming areas. Other farmers were victims of this incident. He reported that: ‘There is not enough time for farmers to harvest blood cockles given the notification of the scheme’s freshwater drainage calendar. This contributes to the loss of the blood cockle crop’ (interview, June 2019). Blood cockles are naturally unable to survive in freshwater environments, let alone endure such prolonged submergence.

FGD participants in Thanh Phuoc Commune commented that, while the sluice scheme prevents saltwater intrusion during the dry season, it also prevents freshwater inflows, resulting in the increased intensity of salinity in the downstream zones. This negatively impacts estuarine fisheries. These findings are consistent withEriksen et al.’s (Citation2021) claim that interventions do not necessarily reduce vulnerability, but they inadvertently reinforce, redistribute, or create new sources of vulnerability. Here, the sluice scheme, while it fosters agricultural development policies in the freshwater/upstream zones, overlooks the complexity of trans-zone water dynamics, as well as the detriments it causes to livelihoods in the downstream/estuary zones.

Power asymmetry through competing water-livelihood relations

FGD participants indicated that they were not formally consulted by the local government in designing and constructing the sluice system. The Ba Lai infrastructure demonstrates the authoritarian power of the local government in undertaking modernistic development policies in the agricultural sector using water infrastructure. It is an example of ‘infrastructural power’ being strategically deployed by state actors in water management (Truelove Citation2021). In this case, the state has overridden the aspirations of the majority of agrarian communities who rely heavily on the exploitation of local resources (brackish/saline water) for their livelihoods. The exclusion of shrimp farmers from the local government’s development policies illustrates the institutional failures of Vietnam’s authoritarian governance institutions (Ortmann Citation2017).

The paper illustrates that the power resides not in the water infrastructure (scheme) itself, but rather in the power possessed by those who deploy the perspective of that infrastructure system. The scheme demonstrates the hegemonic power held by the local government through the construction/operation of the sluice system opposed to the subordinate position of shrimp farmers who do not have equal power in their livelihood decisions. This is analogous to Scott’s (Citation1998, 87) perspective of power regarding state simplifications in map-making. He claimed that:

All state simplifications that we have examined have the character of maps. That is, they are designed to summarise precisely those aspects of a complex world that are of immediate interest to the map-makers and to ignore the rest.

While shrimp farmers are in a subordinate position of influence in local development policies, there remains room for them to exercise agency to meet their needs and achieve goals. Kabeer (Citation1999) used this term to indicate the ‘power within’ of the farmers, which they utilised to empower themselves by negotiating with or resisting the government’s power. The following section assesses how shrimp farmers exercised their everyday politics to maintain shrimp farming practices.

Farmers’ agency in exercising everyday politics

Farmers converted from low-yield rice farming into commercial shrimp farming across coastal areas of the VMD to benefit from high market values and incomes. In unfavourable conditions of changing environments and diseases, the farmers are willing to take risks or apply strategies to mitigate risks (Ngo Citation2020). This is reflected in Thanh Tri Commune, where most shrimp farmers held the view that they would rather deal with risks to maintain high economic returns from shrimp farming rather than conform to the local government’s prescriptive freshwater management policies. A female participant in a FGD noted that:

Everyone in the commune sees huge profits generated by shrimp farming. Although it would result in loss, farmers are keen to go with it. (FGD, June 2019)

Qualitative evidence suggests the everyday politics exercised by shrimp farmers in dealing with the local water management policies. Through the case of agrarian reform in Vietnam, the everyday politics was characterised in the form of foot-dragging or disobedient practices (Dang Citation2018). In this study, the everyday politics was exhibited by the perseverance and determination of shrimp farmers in Thanh Tri to maintain shrimp cultivation. Specifically, it is evident in semi-open confrontational resistance, whereby the shrimp farmers defended their rights and decisions to negotiate for better livelihood outcomes. Everyday politics was demonstrated by multiple strategies deployed by shrimp farmers. For example, they built shrimp ponds, while strategically cultivating various freshwater crops (e.g. bananas and coconuts) surrounding the ponds (). Farmers used this ‘double’ tactic to argue that they have conformed to the local water management rules. Other forms of everyday politics were also practised by shrimp farmers as evidenced through their acts of evasion, dissembling, and deception in their farming practices (Gorman Citation2023). In this case, farmers built fake groundwater wells to attract attention from the local government, while building real ones in a hidden place for shrimp farming. From the agency perspective, these everyday political actions demonstrated not only shrimp farmers’ capacity to make livelihood choices (Brown and Westaway Citation2011) but also their manoeuvres to evade, dissemble, or deceive to meet their needs (Gorman Citation2023). Overall, deploying these tactics enables farmers to challenge the water governance systems while simultaneously empowering themselves to achieve their livelihood expectations.

Figure 3. The main Ba lai sluice gate (a) and shrimp farming hidden in the freshwater zone of Thanh Tri Commune (b). Source: the first author.

Several rationales underlie farmers’ decisions to invest in shrimp farming, in particular, pursuing high-income livelihood opportunities. According to Mutsvangwa-Sammie and Manzungu (Citation2021, 183), farmers are ‘rational beings whose decision-making process is based on an understanding of their needs.’ In relation to shrimp farmers in this study, farmers sought to maintain their original livelihoods to which they were bonded. Farmers argued that shrimp farming enables them to maintain better incomes as compared with freshwater-based commodities, which often have lower returns due to the persistent volatility of global and regional markets. A male participant in a FGD in Thanh Tri Commune complained that:

We often experience the market instability of agro-commodities. Crop investment is too costly. Cultivated in the saltwater and acid sulphate soil conditions, coconut trees, for example, cannot grow well – unlike other areas, here it takes about six or seven years for a coconut tree to produce fruits.

Seeking just solutions for livelihood sustainability

Addressing the complex interplays between water management and demands for livelihood sustainability is essential to bring about just solutions. This endeavour needs to place farmers at the heart of rural and agricultural development policies. Farmers serve as gatekeepers for development and dissemination of rural livelihood innovations, thus making important contributions to rural development policies (Dolinska and d’Aquino Citation2016; Tran, Nguyen, and Vo Citation2019). In this case, farmers have resisted poor government policies and ingeniously adapted to change in water systems under the ‘double’ implications of saltwater intrusion and the Ba Lai scheme.

Enhancing farmer’s livelihoods and capacity to deal with saltwater intrusion rests on the capacity of the local government to undertake co-operative governance of the scheme. In other words, the operational efficacy of the scheme management is based on engaging with farmers’ needs for: (1) the livelihoods they aim to practise, (2) the happiness they expect to gain, and (3) the income they seek to earn. It is evident that the scheme-based water development policies favour freshwater crop production farmers and undermine shrimp farmers. The local government therefore should provide fair livelihood opportunities for all beneficiaries, especially shrimp farmers, whose livelihoods are not recognised as legitimate, and who are seen as ‘culprits’, in the local development programs.

Understanding how farmers’ livelihood decisions are facilitated or constrained by local development institutions is important to seek justice towards resolving the water-livelihood contestations. In this study, harmonising short- versus long-term co-benefits between these relations needs to investigate the intermingled socio-economic and ecological contexts that influence farmers’ decisions to pursue their shrimp farming and engage in everyday politics. We suggest the establishment of a consultation platform that brings together the local government and shrimp farmers into dialogues is critically important. This would allow them to co-design rural development policies, assess possible impacts on local livelihood conditions, and provide corresponding solutions. Further, it would provide room for farmers to articulate their needs and express their aspirations for productive livelihoods. Collectively, the consultation platform offers opportunities for the actors to share their respective views, values, and interests, whereby they can listen, learn, and understand to each other. If effectively facilitated, this would help yield desirable outcomes.

Study limitations

The present case study reflects upon the state-society relations based on the limited qualitative data gathered from respondents involved in the Ba Lai sluice scheme. Further research needs to examine how farmer-led everyday politics engages with decision-making processes at a broader scale, and how this engagement helps advance the knowledge of how the contemporary water management and livelihood contestations could be solved.

Conclusion

The Ba Lai case study presents how the ‘high modernism’ ideology pursued by the Vietnamese government prompts their intervention into the coastalscapes of the VMD. The analysis suggests that the Ba Lai scheme fails to bring justice to the livelihoods of local communities, especially shrimp farmers. The water-livelihood contestations embody the salient power asymmetry, where the government holds hegemonic power in infrastructural development, undermining the aspirations of the majority of farmers whose livelihoods are traditionally dependent on brackish/saline water resources. Shrimp farmers were largely marginalised or even excluded from local development policies. They lacked opportunities to participate in the planning and the management of the scheme, as well as articulate their voices to its adverse impacts.

This case study shows how water infrastructure is employed as a mechanism by the Vietnamese government to exercise and control power. However, there remains room for farmers to exercise their agency to achieve their goals. Various forms of everyday politics were deployed by shrimp farmers to defend their rights and articulate their needs to secure their livelihoods (shrimp farming) in the freshwater zones. The study implies that these contestations would never end as shrimp farmers remain to use brackish/saline water for shrimp farming, which violates the scheme’s rules. While farmer-led everyday politics with micro-actions was undertaken to resist government institutions, they are not sufficient to bring about change in state-led infrastructure-based water management policies.

We recommend that addressing these contested relations should go beyond the understandings of place-based politics. There needs space for multiple stakeholders, including agrarian communities, to negotiate with the local government to reconcile water and livelihood contestations. Specifically, the agency of rural farmers should be further recognised to secure their rights and livelihood legitimacy vis-à-vis the local government’s water development policies. In the VMD, it is essential that co-governance institutions should be put in place to ensure equitable decision-making on future water infrastructure development. The study offers important policy implications for navigating pathways for sustainable water development in coastal deltas and beyond.

Institutional review board (IRB) statement

IRB was not obtained for this study as it was funded by the Southeast Asian Regional Centre for Graduate Study and Research Agriculture (SEARCA) (Reference: GCS18–3091). However, the first author complied with ethical standards while undertaking the field study. Permission to conduct focus group discussions and interviews was obtained by all respondents, who were fully informed about the purposes of this study, and how their responses would be used. All respondents have been anonymised.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by SEARCA’s (Southeast Asian Regional Centre for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture) Seed Fund for Research and Training Program, the Philippines. The authors would like to thank the respondents in the study areas, and research and government institutions for providing information for the study. Finally, the authors gratefully acknowledged Hieu Van Tran for his kind assistance in data collection and Pham Dang Hong Luan for the production of the map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thong Anh Tran

Thong Anh Tran (✉) is a human ecologist with extensive work experiences in mainland Southeast Asia. His research looks into climate and development dynamics in the Mekong region, with a particular focus on (transboundary) environmental governance, agrarian transitions, livelihood resilience, climate change adaptation, social learning, rural innovations, and institutional change.

Jamie Pittock

Jamie Pittock is a Professor in the Fenner School of Environment and Society at The Australian National University. Dr. Pittock worked for non-government environmental organisations in Australia and internationally from 1989 to 2007, including as Director of WWF’s Global Freshwater Program from 2001–2007. Since 2007 his research has focused on better governance of the interlinked issues of water management, energy and food supply, responding to climate change and conserving biological diversity. Conservation of freshwater ecosystems in the Murray-Darling Basin is a focus of his research. Dr. Pittock directs research programs on irrigation and water management in Africa, and on hydropower, food and water in the Mekong region. He is a member of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists. Dr. Pittock teaches courses on environment and society as well as on climate change adaptation.

Notes

1. Resolution 120 is the Vietnamese Government’s policy that guides climate-resilient and sustainable development pathways in the VMD. The document includes an overarching development agenda concerning the government’s planning strategies, objectives, visions, solutions, as well as tasks to improve the socio-economic development of the VMD while highlighting priorities for climate change adaptation (GoV Citation2017).

2. Blood cockles (Anadara granosa) are the bivalve mollusc species commonly cultivated at open water estuarine ecosystems with intertidal alluvial mudflats. The blood cockle farming concentrates largely in nutrient-rich mudflat areas in Ben Tre and other coastal provinces of the VMD (Tu et al. Citation2022).

References

- Benedikter, S. 2014. “Extending the Hydraulic Paradigm: Reunification, State Consolidation, and Water Control in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta After 1975.” Southeast Asian Studies 3 (3): 547–587.

- Ben Tre People’s Committee. 2016. Ben Tre Water Management Project – Environmental Impact Assessment Report. Ben Tre City: Ben Tre People’s Committee.

- Biggs, D. A. 2010. Quagmire: Nation-Building and Nature in the Mekong Delta. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Biggs, D., F. Miller, C. T. Hoanh, and F. Molle. 2009. “The Delta Machine: Water Management in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta in Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.” In Contested Waterscapes in the Mekong Region – Hydropower, Livelihoods and Governance, edited by F. Molle, T. Foran, and M. Käkönen, 203–225. London: Earthscan.

- Binh Dai Statistical Agency. 2018. Binh Dai Statistical Yearbook in 2017. Binh Dai District: Binh Dai Statistical Agency.

- Brown, K., and E. Westaway. 2011. “Agency, Capacity, and Resilience to Environmental Change: Lessons from Human Development, Well-Being, and Disasters.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 36 (1): 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-052610-092905.

- Bruun, O. 2020. “Environmental Protection in the Hands of the State: Authoritarian Environmentalism and Popular Perceptions in Vietnam.” The Journal of Environment and Development 29 (2): 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496520905625.

- Bruun, O., and O. Rubin. 2023. “Authoritarian Environmentalism – Captured Collaboration in Vietnamese Water Management.” Environmental Management 71 (3): 538–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-022-01650-7.

- Cleaver, F. 2007. “Understanding Agency in Collective Action.” Journal of Human Development 8 (2): 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880701371067.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2007. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. California: Sage Publications.

- Crow-Miller, B., M. Webber, and F. Molle. 2017. “The (Re)turn to Infrastructure for Water Management.” Water Alternatives 10 (2): 195–207.

- Dang, T. D. 2010. “Post-1975 Land Reform in Southern Vietnam: How Local Actions and Responses Affected National Land Policy.” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 5 (3): 72–105. https://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2010.5.3.72.

- Dang, T. D. 2018. Vietnam’s Post-1975 Agrarian Reforms – How Local Politics Derailed Socialist Agriculture in Southern Vietnam. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Davidson, D. J. 2010. “The Applicability of the Concept of Resilience to Social Systems: Some Sources of Optimism and Nagging Doubts.” Society and Natural Resources 23 (12): 1135–1149. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941921003652940.

- Dolinska, A., and P. d’Aquino. 2016. “Farmers as Agents in Innovation Systems. Empowering Farmers for Innovation Through Communities of Practice.” Agricultural Systems 142:122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2015.11.009.

- Eriksen, S., E. L. F. Schipper, M. Scoville-Simonds, K. Vincent, H. N. Adam, N. Brooks, B. Harding, et al. 2021. “Adaptation Interventions and Their Effect on Vulnerability in Developing Countries: Help, Hindrance or Irrelevance?” World Development 141:105383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105383.

- Eslami, S., P. Hoekstra, P. S. J. Minderhoud, N. N. Trung, J. M. Hoch, E. H. Sutanudjaja, D. D. Dung, et al. 2021. “Projections of Salt Intrusion in a Mega-Delta Under Climatic and Anthropogenic Stressors.” Communications Earth & Environment 2 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00208-5.

- Ettinger, J., F. E. L. Otto, and E. L. F. Schipper. 2021. “Storytelling Can Be a Powerful Tool for Science.” Nature 589 (7842): 352–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00108-w.

- Fabinyi, M., B. Belton, W. H. Dressler, M. Knudsen, D. S. Adhuri, A. A. Aziz, M. A. Akber, et al. 2022. “Coastal Transitions: Small-Scale Fisheries, Livelihoods, and Maritime Zone Developments in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Rural Studies 91:184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.02.006.

- Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (1): 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

- Gorman, T. 2023. “The Art of Not Being Freshened: The Everyday Politics of Infrastructure in the Mekong Delta.” Sustainability 15 (6): 5494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065494.

- GoV (Government of Vietnam). 2017 November 17. Resolution No. 120/NQ-CP on Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Development of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Hanoi: Government of Vietnam.

- Gowing, J. W., T. P. Tuong, C. T. Hoanh, and N. T. Khiem. 2006. “Social and Environmental Impacts of Rapid Change in the Coastal Zone of Vietnam: An Assessment of Sustainability Issues.” In Environment and Livelihoods in Tropical Coastal Zones – Managing Agriculture-Fisheries-Aquaculture Conflicts, edited by C. T. Hoanh, T. P. Tuong, J. W. Gowing, and B. Hardy, 48–60. Oxon: CAB International.

- Ha, T. T. P., H. V. Dijk, R. Bosma, and L. X. Sinh. 2013. “Livelihood Capabilities and Pathways of Shrimp Farmers in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam.” Aquaculture Economics & Management 17 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13657305.2013.747224.

- Hill, K. 2015. “Coastal Infrastructure: A Typology for the Next Century of Adaptation to Sea Level Rise.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 13 (9): 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1890/150088.

- Hinkel, J., J. C. J. H. Aerts, S. Brown, J. A. Jiménez, D. Lincke, R. J. Nicholls, P. Scussolini, A. Sanchez-Arcilla, A. Vafeidis, and K. A. Addo. 2018. “The Ability of Societies to Adapt to Twenty-First-Century Sea-Level Rise.” Nature Climate Change 8 (7): 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0176-z.

- Hoang, Q. H., N. Kubo, N. G. Hoang, and H. Tanji. 2009. “Operation of the Ba Lai Irrigation System in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam.” Paddy and Water Environment 7 (2): 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10333-009-0155-0.

- Hoanh, C. T., T. P. Tuong, K. M. Gallop, J. W. Gowing, S. P. Kam, N. T. Khiem, and N. D. Phong. 2003. “Livelihood Impacts of Water Policy Changes: Evidence from a Coastal Area of the Mekong River Delta.” Water Policy 5 (5–6): 475–488. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2003.0030.

- Hoitink, A. J. F., J. A. Nittrouer, P. Passalacqua, J. B. Shaw, E. J. Langendoen, Y. Huismans, and D. S. van Maren. 2020. “Resilience of River Deltas in the Anthropocene.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 125 (3): e2019JF005201. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JF005201.

- Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125.

- Käkönen, M. 2008. “Mekong Delta at the Crossroads: More Control or Adaptation?” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 37 (3): 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[205:MDATCM]2.0.CO;2.

- Kemerink, J. S., S. N. Munyao, K. Schwartz, R. Ahlers, and P. van der Zaag. 2016. “Why Infrastructure Still Matters: Unravelling Water Reform Processes in an Uneven Waterscape in Rural Kenya.” International Journal of the Commons 10 (2): 1055–1081. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.646.

- Kerkvliet, B. J. 2005. The Power of Everyday Politics: How Vietnamese Peasants Transformed National Policy. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Klenk, N. 2018. “Adaptation Lived as a Story: Why We Should Be Careful About the Stories We Use to Tell Other Stories.” Nature and Culture 13 (3): 322–355. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2018.130302.

- Le, V. T. H., T. A. Tran, and M. F. Rola-Rubzen. 2023. “How Subjectivities and Subject-Making Influence Community Participation in Climate Change Adaptation: The Case of Vietnam.” Climatic Change 176 (156): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03625-x.

- Lindegaard, L. S., and L. T. H. Sen. 2022. “Everyday Adaptation, Interrupted Agency and Beyond: Examining the Interplay Between Formal and Everyday Climate Change Adaptations.” Ecology and Society 27 (4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13610-270442.

- Mahanty, S., S. Milne, K. Barney, W. Dressler, P. Hirsch, and P. X. To. 2023. “Rupture: Towards a Critical, Emplaced, and Experiential View of Nature-Society Crisis.” Dialogues in Human Geography 13 (2): 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221138057.

- Manlosa, A. O. 2022. “Operationalising Agency in Livelihoods Research: Smallholder Farming Livelihoods in Southwest Ethiopia.” Ecology and Society 27 (1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12887-270111.

- Manlosa, A. O., J. Albrecht, and M. Riechers. 2023. “Social Capital Strengthens Agency Among Fish Farmers: Small Scale Aquaculture in Bulacan, Philippines.” Frontiers in Aquaculture 2:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/faquc.2023.1106416.

- Meehan, K. M. 2014. “Tool-Power: Water Infrastructure as Wellsprings of State Power.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 57:215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.08.005.

- Miani, A. M., M. M. Dehkordi, N. Siamian, L. Lassois, R. Tan, and H. Azadi. 2023. “Toward Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Approach: Application of Grounded Theory in Ghazni Province, Afghanistan.” Applied Geography 154:102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.102915.

- Mishra, H., B. W. Pandey, G. Mukwada, P. de Los Rios, N. Nigam, and N. Sahu. 2023. “Trapped within Nature: Climatic Variability and Its Impact on Traditional Livelihood of Gaddi Trans-Humance of Indian Himalayas.” Local Environment 28 (5): 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2162025.

- Molle, F., P. P. Mollinga, and P. Wester. 2009. “Hydraulic Bureaucracies and the Hydraulic Mission: Flows of Water, Flows of Power.” Water Alternatives 2 (3): 328–349.

- Mutsvangwa-Sammie, E. P., and E. Manzungu. 2021. “Unpacking the Narrative of Agricultural Innovations as the Sine Qua Non of Sustainable Rural Livelihoods in Southern Africa.” Journal of Rural Studies 86:181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.06.005.

- Ngo, T. P. L. 2020. “Risk Mitigation of Vietnamese Farmers in the Mekong Delta in the Shift from Rice Cultivation to Shrimp Farming.” In The Mekong, History, Geology and Environmental Issues, edited by S. Marseau, 77–104. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Nicholls, R. J., W. N. Adger, C. W. Hutton, and S. E. Hanson. 2020. Deltas in the Anthropocene. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nygren, A. 2021. “Water and Power, Water’s Power: State-Making and Socio-Nature Shaping Volatile Rivers and Riverine People in Mexico.” World Development 146:105615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105615.

- Ortmann, S. 2017. Environmental Governance in Vietnam: Institutional Reforms and Failures. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Paschen, J. A., and R. Ison. 2014. “Narrative Research in Climate Change Adaptation – Exploring a Complementary Paradigm for Research and Governance.” Research Policy 43 (6): 1083–1092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.12.006.

- Rahman, M. M., G. Penny, M. S. Mondal, M. H. Zaman, A. Kryston, M. Salehin, Q. Nahar, et al. 2019. “Salinisation in Large River Deltas: Drivers, Impacts and Socio-Hydrological Feedbacks.” Water Security 6:100024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasec.2019.100024.

- Scoones, I. 2009. “Livelihoods Perspectives and Rural Development.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820503.

- Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Szabo, S., E. Brondizio, F. G. Renaud, S. Hetrick, R. J. Nicholls, Z. Matthews, Z. Tessler, et al. 2016. “Population Dynamics, Delta Vulnerability and Environmental Change: Comparison of the Mekong, Ganges-Brahmaputra and Amazon Delta Regions.” Sustainability Science 11 (4): 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0372-6.

- Tortajada, C. 2014. “Water Infrastructure as an Essential Element for Human Development.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 30 (1): 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2014.888636.

- Tran, T. A. 2020. “From Free to Forced Adaptation: A Political Ecology of the ‘State-Society-Flood’ Nexus in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 61 (1): 162–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12241.

- Tran, T. A., and B. R. Cook. 2023. “Water Retention for Agricultural Resilience in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: Towards Integrated ‘Grey-Green’ Solutions.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2023.2207674.

- Tran, T. A., T. H. Nguyen, and T. T. Vo. 2019. “Adaptation to Flood and Salinity Environments in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: Empirical Analysis of Farmer-Led Innovations.” Agricultural Water Management 216:89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2019.01.020.

- Tran, T. A., and C. Tortajada. 2022. “Responding to Transboundary Water Challenges in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: In Search of Institutional Fit.” Environmental Policy and Governance 32 (4): 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1980.

- Tran, T. A., H. V. Tran, J. Pittock, and B. Cook. 2022. “Political Ecology of Freshening the Mekong’s Coastal Delta: Narratives of Place-Based Land-Use Dynamics.” Journal of Land Use Science 17 (1): 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2022.2126907.

- Truelove, Y. 2021. “Who is the State? Infrastructural Power and Everyday Water Governance in Delhi.” Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 39 (2): 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419897922.

- Tu, N. P. C., N. N. Ha, N. V. Dong, D. T. Nhan, and N. N. Tri. 2022. “Heavy Metal Levels in Blood Cockle from South Vietnam Coastal Waters.” New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 58 (1): 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2022.2154813.

- Veettil, B. K., N. X. Quang, and N. T. T. Trang. 2019. “Changes in Mangrove Vegetation, Aquaculture and Paddy Cultivation in the Mekong Delta: A Study from Ben Tre Province, Southern Vietnam.” Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 226:106273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2019.106273.