The twenty-first century is witnessing many environmental challenges, including climate change, loss of biodiversity, deforestation, pollution (air, water, soil), resource depletion, waste management, land degradation, and so on. Academic work has pointed to the causes and effects of these challenges—often recognizing the ways they intersect. Amid all this, the concept of carbon colonialism has been explored by the prominent human geographer Laurie Parsons, who is working as a Senior Lecturer at Royal Holloway, University of London. He dedicated himself for more than a decade to studying climate change, the global economy and production, and their environmental impacts through empirical observations and interactions with affected people.

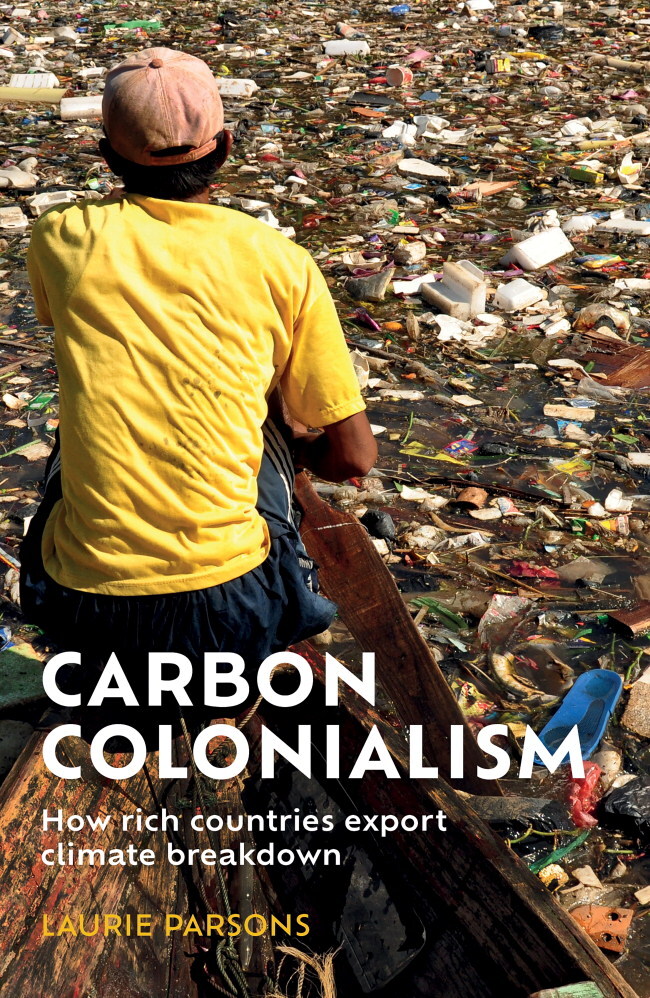

Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Export Climate Breakdown addresses the adverse impact of the global supply chain on carbon emission and the hidden politics behind climate actions. It also traces the imprints of economic imperialism of Global North nations on environmental sustainability and the socioeconomic well-being of impoverished nations that find themselves at the forefront of the challenges of climate change. Carbon Colonialism is a reliable source for individuals interested in the intersection of climate change and the global economy, particularly in terms of production and supply chains. The book has two parts, which comprise eight chapters, exploring diverse case studies from various individuals, communities, and geographical locations.

Parsons’s book primarily explores the political economy of transferring carbon emissions from wealthy nations of the Global North to the Global South. To substantiate his arguments, he provides examples from various sectors, focusing notably on the brick industry, garment manufacturing, international brands, food production, and global supply chains. He then extends this to consider the ways these industries have been functioning and affecting the global supply chain, which contributes to the vast carbon emission, forced and child labor, and exploitations of natural resources of countries of the Global South by countries of the Global North. Parsons called this whole process “carbon colonialism” because it follows the historical inheritance of the colonial framework. He discusses pathways to decolonize carbon emissions and urges the regulation and monitoring of consumption rather than production.

Extending the argument by talking about the dichotomy between sustainability and economic development, Parson states that economic resource availability is the pivotal factor behind mitigating the climate impacts. Therefore, adverse impacts of climate change are less likely in wealthy nations than in poor countries. For instance, Jakarta and London will be affected differently by rising sea levels, because Jakarta does not own resources as London does in terms of technological expertise and development, infrastructural setup, financial resources, social capital, workforce productivity, and political commitment. Hence, national wealth and resources are prominent factors in mitigating the risk of climate change. Parsons said, “You can either stop contributing to environmental degradation, or you can accumulate the resources to mitigate its impacts, but the evidence suggests that you can’t do both” (p. 18). Interestingly, the environmental aesthetics of many rich countries are consistently improving, whereas poor nations report the opposite trend. The prevalence of this improvement is hidden in the complex global supply chain, driven by industries that transfer commodities from the Global South to the North. This vast transfer of commodities resulted in huge carbon emissions, which degrade the environment and increase resource exploitation. Thus, the globalization of commodities and production has become a tool for exploiting the natural resources and labor of Global South nations by the North (Smith Citation2016). Now it has become crucial to trace this outsourcing of carbon emission and extraction of natural resources to create sustainability and decolonize the global economy.

The United Kingdom claimed to have successfully reduced its carbon emissions by nearly 44 percent since 1990, an impressive accomplishment that has brought carbon levels back to those seen in 1890. This positive trend extends to the European Union and the United States, and both have also experienced significant declines in carbon emissions. Despite these achievements and five decades of efforts to establish environmental agreements (from the world’s first climate change conference in 1972 to COP-26 in Glasgow in 2021), the data indicate a discernable rise in atmospheric carbon concentration, highlighting persistent challenges in addressing environmental issues. The explanation is straightforward: Major carbon-emitting firms have outsourced their production to countries in the Global South. One of the major examples Parsons gave in his book is the brick industry. The United Kingdom imports 400 million bricks, 30 to 40 million from outside the European Union, notably from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India, which raises a substantial carbon problem. Each container covering 18,000 kilometers emits 600 tons of carbon, equivalent to the weight of five blue whales. These products are imported by the Global North as a cost-effective strategy for them compared to domestic production. Unfortunately, this global supply chain results in higher carbon emissions than if the production and consumption occurred domestically.

Industries in countries like Cambodia, Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, which are involved in brickfields, cotton production, tea plantations, and clothing manufacturing, experience environmental issues, economic inequality, and exploitative practices such as bondage and child labor. These issues are deeply connected with the outsourcing of production practices and a complex global supply chain. These adverse effects, paired with the repercussions of climate change, contribute to huge environmental degradation, and increase the vulnerability of the socioeconomic well-being of nations in the Global South. In the words of Parsons, “People are not vulnerable to the changing climate by accident. They are vulnerable because society makes them vulnerable. Forests, fields, and oceans do not happen to be vulnerable to pollution and degradation. They are vulnerable because the global factory makes them vulnerable” (p. 205). These factories and industries in countries of the Global South, however, shared a long history of natural resource extraction and exploitation, drawing parallels with colonial-era practices.

Now, goods are produced in dispersed factories beyond our borders, making it challenging to trace their origins and measure environmental impact because the complexity of the global supply chain decreases the direct oversight in our globalized economy. Due to the lack of direct oversight on production and supply, the Global North companies freely entitle themselves as environmentally conscious and sustainable through deceptive claims and misleading information. Adhering to this, Parson gave the example of Cambodian garment factories (a major source country of the United Kingdom’s garment imports and exports) that are fueled by illegally deforested wood to iron shirts, contradicting brands’ claims of zero-deforestation and waste policies. This is how the “greenwashing” concept has been used by Global North nations to maximize their profits. These businesses claim their practices are eco-friendly without substantial evidence. Therefore, the author argues that one should not completely trust and get trapped by companies’ false claims. Instead, we need to recognize these deceptive tactics, voice their objections, and collectively push for systemic change toward sustainability.

Another point raised by Parsons is about the prominent extinction rebellion entities like Gazprom, Saudi Aramco, Bill Gates, and Mark Carney. These entities claim to contribute trillions of dollars to foster green growth, sustainability, and equality. A crucial doubt arises, though: Where do these trillions of dollars originate? These funds come from businesses, fossil fuels, and vested interests. This money is then directed toward shaping sustainability according to the interests of funders. This is not just an abstract concern; it has concrete implications. At COP-26, more than seventy countries promised to limit greenhouse gas emissions to the level that nature can naturally absorb (Net Zero) between 2050 and 2100. In COP-26, countries pledged to set emission reduction targets every five years and provide climate finance to help other nations adapt to climate change and transition to renewable energy. Although these steps were portrayed as positive, what COP-26 did not address was the issue of wealthy countries shifting emissions outside their national borders to evade responsibility. Policies determined at forums like COP-26 are increasingly influenced by corporate interests. The politics of climate change are inseparable from economic influences, particularly in the realm of actual carbon emissions. This process is known as the “Shifting the Overton Window” concept, where more financial resources can influence public opinion in a desired direction. Therefore, human actions and commitment are far away from reaching the goals of sustainability and mitigation of climate change impacts.

In conclusion, the author reveals the myths about climate change by highlighting the fact that climate never acts alone but with economic inequality. We are the outcomes of a system of environmental dominance that has evolved over centuries, yet we often fail to recognize ourselves as subjects within this global economic framework. The narratives that the economy can solve the issues are the integral components of carbon colonialism. To free ourselves from carbon colonialism, this book proposes a change in outlook. First, we should focus on measuring global carbon emissions based on consumption rather than production and to search narratives promoting individual actions and the formation of legal frameworks governing global supply chains. Second, we must develop an awareness of deceptive tactics employed by businesses partaking in greenwashing and assertively voice objections against misleading information and false eco-friendly claims. Finally, we should actively advocate for transparency in global supply chains to accurately trace the genuine environmental impact. Thus, this book is a good fit for a diverse range of readers, including environmentalists, climate activists, climatologists, geographers, economists, and policymakers, because it offers valuable insights into the hidden political economy surrounding climate change discourse. Carbon Colonialism has garnered attention because of its comprehensive list of ground-level case studies of people and communities who faced the real-time impacts of climate change on their means of sustenance, agriculture, and livelihood, and the exploitation of laborers in a globalized economy of production and supply chain that leads economic inequality. Whether you are deeply involved in environmental conservation or simply interested in preserving our planet, this book provides a thought-provoking exploration of the vulnerabilities emerging from the current climate crisis and global economy.

Reference

- Smith, J. 2016. Imperialism in the twenty-first century: Globalization, super-exploitation, and capitalism’s final crisis. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.