ABSTRACT

The introduction of the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY) scheme in India was a significant step toward universal health coverage. The PM-JAY scheme has made notable progress since its inception, including increasing the number of people covered and expanding the range of services provided under the health benefit package (HBP). The creation of the Health Financing and Technology Assessment (HeFTA) unit within the National Health Authority (NHA) further enhanced evidence-based decision-making processes. We outline the journey of HeFTA and highlight significant cost savings to the PM-JAY as a result of health technology assessment (HTA). Our paper also discusses the application of HTA evidence for decisions related to inclusions or exclusions in HBP, framing standard treatment guidelines as well as other policies. We recommend that future financing reforms for strategic purchasing should strengthen strategic purchasing arrangements and adopt value-based pricing (VBP). Integrating HTA and VBP is a progressive approach toward health care financing reforms for large government-funded schemes like the PM-JAY.

Introduction

The Indian government has demonstrated strong political commitment toward achieving the ambitious goal of universal health coverage (UHC).Citation1–3 One of its major achievements has been the launch of the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) scheme, the implementation of which resides with the National Health Authority (NHA).Citation4 Launched in 2018, the PM-JAY provides insurance coverage to approximately 500 million poor and vulnerable beneficiaries, of up to ₹500,000 INR (6,064 USD) per family, per year, to avail secondary and tertiary care hospitalization at public and empanelled private hospitals.Citation4 When compared to other government-funded health insurance schemes in India, and the erstwhile Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, the PM-JAY offers several times greater financial coverage.Citation5

The budget for the PM-JAY has risen by 12% in 2023–24, compared to the previous year.Citation6 The increase in public financing for health care has led to a notable decrease in out-of-pocket expenditure, from 64.2% in 2013–14 to 47.1% in 2019–2020. However, achieving UHC necessitates a significantly higher allocation of resources.Citation7 While the Indian government has committed substantial resources to the PM-JAY, there will still be trade-offs between the extent of population coverage, the range of available services, and the proportion of total cost to be borne.Citation5,Citation8 Moreover, there are increasing demands to expand service coverage. Therefore, evidence-based prioritization should be employed to maximize the value of each rupee spent.

Health technology assessment (HTA) is one evidence-based decision-making tool recently adopted by India. In 2017, the Department of Health Research (DHR) established the Health Technology Assessment in India (HTAIn)—a government-mandated body responsible for conducting and commissioning HTAs.Citation9 The HTAIn’s primary role is to evaluate a wide range of health technologies and health care interventions, providing evidence on their safety, clinical effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness.Citation10 This information aims to inform health policy decisions, including the selection of services covered under the PM-JAY’s health benefit package (HBP). However, the success of this evidence to policy translation depends on the capacity to use HTA evidence within the NHA.

This paper aims to describe the organization and institutional arrangements associated with use of HTA evidence in decision-making processes within the PM-JAY. As part of the process for developing this manuscript, we have combined the personal insights of the authors (including in former official capacities) with a review of the existing literature. Our primary focus has been to leverage personal experiences and knowledge to provide practical, real-world perspectives. We also conducted a review of existing policy documents from the NHA website to complement and validate these insights.

Setting Up of the HeFTA Unit in NHA

The NHA is an autonomous body under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, which is responsible for the implementation of the PM-JAY. The NHA has several other key responsibilities, including formulating and revising the HBP, developing policy and operational guidelines, and setting standards for treatment and quality protocols. More importantly, the NHA is responsible for developing mechanisms for the purchasing of health care services through the PM-JAY scheme, providing direction on what to purchase, from whom, at what price, and for which population group. In other words, the NHA establishes efficient payment mechanisms to ensure optimal returns on the government’s investment.Citation11,Citation12

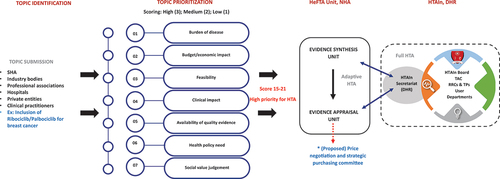

To optimize value for money in the allocation of financial resources in the PM-JAY, enhance accessibility, provide greater financial protection, and reduce health inequalities, the NHA established the Health Financing and Technology Assessment (HeFTA) unit in 2022 ().Citation12,Citation13 The HeFTA unit promotes the application of HTA evidence so that the PM-JAY resources are allocated efficiently. The creation of both the HeFTA unit and the HTAIn grew from two key considerations. Firstly, while the HTAIn accepts HTA nominations from public entities and payers, the PM-JAY ecosystem comprises approximately 28,000 empaneled hospitals, about half of which belong to the private sector—a vital stakeholder for the PM-JAY. Consequently, the HeFTA unit, operating under the purview of the NHA, offers a platform for private industry entities, including hospitals and pharmaceuticals, as well as the medical device industry, to submit nominations for HBP inclusion.

Figure 1. Operational framework of the Health Financing and Technology Assessment (HeFTA) unit within National Health Authority (NHA).

Secondly, recognizing the urgency of decision-making from an implementer’s perspective and the time-consuming nature of full HTA assessments, there was a pressing need for expedited evidence synthesis to inform timely decision-making. In response, the HeFTA unit established an evidence synthesis team, responsible for evaluating existing evidence and prioritizing it according to the needs of the population being catered for. The dynamic context in which the HeFTA unit was established is illustrated in .

Box 1: Establishment of the Health Financing and Technology Assessment (HeFTA) 1 Unit in the National Health Authority (NHA).

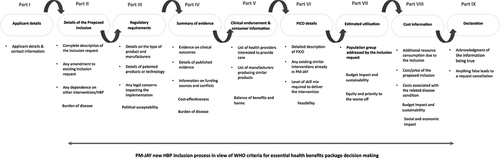

One of the key objectives of the HeFTA unit is to establish a structured and transparent framework for the selection of technologies. To fulfill this objective, the NHA launched a portal on its website to accept nominations for new technologies for inclusion in the HBP ().Citation12 This portal allows pharmaceutical companies, the medical device industry, health care professionals, patients’ rights groups, payer agencies, regulatory bodies, and other stakeholders to submit their products for consideration to be included in the PM-JAY HBP. Topics can be submitted throughout the year through the NHA website, and assessment and prioritization are carried out concurrently. The topic prioritization process is central to identifying the most relevant areas for assessment. The key criteria for prioritization include the burden of the health problem under consideration, its economic and clinical impact, feasibility of its implementation, availability of evidence on clinical effectiveness, its potential ethical and equity implications, and policy relevance.Citation12 This ensures that assessments are conducted on topics of greater relevance and prevents unnecessary effort and resources on assessments that may have limited value.

Figure 2. The Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY) inclusion criteria for new health benefit package inclusion requests.Citation14

Furthermore, the HeFTA unit is responsible for collecting and analyzing health economic evidence. To do so, it undertakes horizon scanning, which involves actively identifying and monitoring emerging HTA evidence for health technologies, interventions, and treatments. Although horizon scanning is traditionally focused on identifying new technologies for inclusion in the HBP, the HeFTA unit employs horizon scanning to identify emerging HTA evidence, evaluate its quality, and assess its generalizability. This evidence is used to assess if it is fit-for-purpose to use in the PM-JAY framework, including decisions on inclusion in the HBP, formulating standard treatment guidelines (STGs), pricing, or developing quality guidelines.

The HeFTA unit conducts its activities in coordination with the HTAIn, which is entrusted with producing high-quality HTA evidence. Through this collaboration, the HTAIn fulfills the evidence requirements of the HeFTA unit by conducting HTA studies on prioritized topics that require evaluation for inclusion in the HBP. Initially, every topic forwarded to the HeFTA unit undergoes a preliminary evaluation, and those deemed suitable for full economic assessment are referred to HTAIn for further detailed evaluation. The technical appraisal committee (TAC) of HTAIn plays a pivotal role in this collaboration. Although it does not directly conduct the HTA studies, the TAC shapes recommendations stemming from these assessments. These recommendations are instrumental in guiding the NHA in its decision-making process. Ultimately, this collaborative approach between the HeFTA unit and the HTAIn ensures a comprehensive and robust evaluation of health care topics.

This effective coordination optimizes the available expertise within both entities, ensuring reliable evidence utilization in the decision-making process by the NHA. As of March 2022, the HTAIn has successfully completed 42 HTA studies, with 32 ongoing. An assessment to quantify the return on investment (ROI) achieved by the HTAIn’s three specific HTAs reported an impressive overall return of 9:1. The individual returns on these HTAs varied from 5:1 to as high as 40:1.Citation15

Impact of HTA-Informed Decision-Making Under the PM-JAY

Since the establishment of the HeFTA unit, numerous requests for inclusion have been submitted for review. To evaluate these requests in a methodical and effective way, a prioritization procedure has been implemented to select the interventions that will undergo comprehensive HTA. Certain requests for inclusion have also been rejected based on cost-effectiveness considerations where comprehensive evidence is identified through horizon scanning, ensuring that resources are only directed toward interventions that offer value for money.

In addition to the selection and evaluation of nominations, the HeFTA unit actively evaluates the outcomes of its actions concerning the inclusion or exclusion of requests, the rationalization of HBPs, and the development or revision of standard treatment guidelines. These assessments are conducted as integral components of the ongoing monitoring and evaluation efforts. Overall, the establishment of the HeFTA unit has had a positive impact on the decision-making process under the PM-JAY. In this section, we describe three case studies where HTA evidence has resulted in cost-effective and evidence-based policy formulation, revision of STGs, and decisions regarding inclusion requests for the HBP.

Using HTA Evidence for Policy Formulation: Rationalizing the Packages for Renal Replacement Therapy

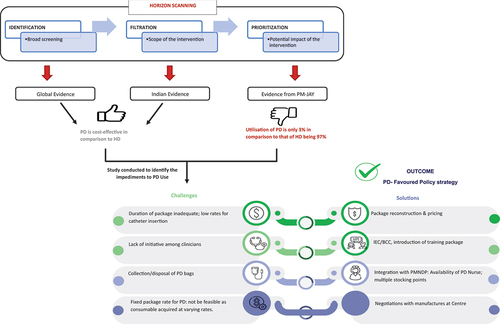

Dialysis is one of the most commonly used packages under the PM-JAY scheme.Citation16 While hemodialysis (HD) necessitates specialized infrastructure and trained health care professionals, peritoneal dialysis (PD) can be conducted by patients or caregivers at home without specialized infrastructure. Despite this, the use of PD under the PM-JAY remained notably low, at approximately 3%. Through horizon scanning, the HeFTA unit identified economic evidence indicating that PD is a cost-saving therapy compared to HD in various countries, including India.Citation17,Citation18 The evidence on cost-effectiveness from India demonstrated that patients on PD yielded higher quality-adjusted life years (3.3 QALYs per person) compared to those treated with HD (1.6 QALYs per person).Citation19 Additionally, given the current cost and utilization patterns, implementing PD as the preferred treatment option could result in significant lifetime cost savings from a societal perspective, ranging from ₹100,000 INR (1,213 USD) per person to ₹700,000 INR (8,491 USD) per person for use in the public sector. When factoring for the increase in the number of new end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients in India, of which around 40% are expected to be PM-JAY beneficiaries, adopting a PD-first policy for at least 50% of the annual incident cohort ESRD patients could lead to substantial lifetime savings ranging from ₹4,400 to ₹30,660 million INR (53–371 million USD).

In light of this, a feasibility assessment was undertaken by the HeFTA unit in consultation with state health authorities, provider hospitals, nephrologists, and manufacturers of HD and PD kits.Citation20 The assessment uncovered key challenges: unclear guidance among providers regarding the number of PD sessions required, absence of a PD catheter insertion package and its prices, logistical issues with the availability of PD consumables, and the need for patient education without current funding or operational plans. Moreover, a lack of clinician motivation for a PD-first policy was also identified as a barrier.Citation20

Based on assessment findings, HeFTA recommended a PD-focused policy for newly diagnosed ESRD PM-JAY beneficiaries, unless medically contraindicated (). Proposed strategies included an enhanced package with extended duration, revised rates covering consumables, incentives for providers, follow-up investigations, and support for supply management. Secondly, provider-level interventions recommended education sessions to promote PD acceptance among nephrologists, clinicians, and health care workers, as well as training for nurses and physicians in catheter insertion and complication management.

Figure 3. Application of horizon scanning for formulating evidence informed policy strategies: use of peritoneal dialysis for renal replacement therapy.

Thirdly, to enhance care delivery at the consumer and beneficiary levels, integrating the PMNDP and PM-JAY was recommended. This involved deploying PD nurses at Community Health Centres, establishing storage points for PD consumables, facilitating their distribution to registered beneficiaries, and ensuring proper disposal of used PD bags. Finally, central negotiations for consumables’ prices were advised to streamline procurement across states and providers.

Using HTA Evidence for Revising STGs: Addressing Oncology Packages

The inclusion of horizon scanning as part of the HeFTA unit’s activities has proven to be highly valuable in rationalizing the HBPs. Another notable example of this is the revision of oncology packages. The addition of targeted monoclonal antibody trastuzumab to chemotherapy as part of adjuvant treatment for HER2/neu positive breast cancer women has demonstrated significant improvements in disease-free and overall survival. Initially, the oncology package for breast cancer treatment with trastuzumab under the PM-JAY was capped at four cycles. From 2019 to 2022, multiple representations were received from diverse stakeholders, such as private hospitals, individuals, patient group representatives, state health authorities, and elected state representatives. These representations collectively advocated for an increase in the approved cycles under the PM-JAY scheme from four to 18 cycles annually. This prompted the need for an examination of economic evidence pertaining to cost-effectiveness.

In a recent evaluation, the cost-effectiveness of adjuvant trastuzumab therapy in HER2/neu-positive Indian women was assessed, comparing a one-year duration of treatment to six months.Citation21 The analysis demonstrated that using trastuzumab for six months was cost-effective compared to one year. As part of the review of HTA evidence through horizon scanning, the HeFTA unit identified this evidence for application to revise the STG for trastuzumab package. As a result, the STGs were revised to increase the cap on cycles from four to eight. This revision meant two things. First, the increase in the number of cycles approved for trastuzumab therapy from four to eight meant higher access to treatment, improved clinical effectiveness leading to better health outcomes, and a reduction in OOP expenditure since patients are not forced to pay for the last four cycles of the adjuvant therapy. Second, using the HTA evidence and not increasing the number of approved cycles up to 18 implied an annual cost saving of ₹4160 million INR (50 million USD) for the payer.

A second case study that illustrates the use of HTA for framing STGs is packages for radiation therapy (RT) for breast cancer. Radiation therapy packages for breast cancer are among the most frequently used packages.Citation22 However, there is a high degree of variation in clinical practice in administering RT in terms of the number of nodes involved, the amount of units of radiation (gray [Gy]) used, and the optimum number of days or fractions to be delivered for desired outcomes.Citation23

The HeFTA unit, through its horizon scanning processes, identified evidence pertaining to cost-effectiveness of post-mastectomy RT (PMRT) in India based on type of radiotherapy, laterality, pathologic nodal burden, and dose fractionation.Citation24 The evidence concluded that PMRT was cost-effective for all node-positive women (cost saving for N1–3 lymph node group & cost-effective for N4+ lymph node subgroup), but not cost-effective for the node-negative breast cancer treatment. Furthermore, the adoption of hypo-fractionated therapy, which has been found to significantly reduce treatment costs, should be implemented as the standard of care. Based on the findings of the study, the STGs for the breast cancer radiation package were revised to include the use of a hypo-fractionated regimen instead of the conventional approach. This revision was estimated to result in substantial cost savings, as approximately 67% of patients were booking 10.65 fractions more than required, which amounted to a cost of ₹418 million (5 million USD) per year. Additionally, based on the revision in STGs, the indication for PMRT was withdrawn for lymph node-negative patients who were previously receiving radiotherapy. These revisions in the STGs have the potential to save the PM-JAY ₹528–1056 million (6–12 million USD) per year, making the treatment more cost-effective while maintaining quality care for breast cancer patients.

Rejecting Inclusion Requests Based on HTA Evidence

One of the requests for inclusion in HBPs was to include cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i), ribociclib, and palbociclib for metastatic breast cancer patients which have shown improved survival outcomes.Citation25,Citation26 The topic was referred to the HTAIn for a full HTA.Citation27 This assessment compared the cost-effectiveness of combination ribociclib and palbociclib with fulvestrant compared to fulvestrant monotherapy (which is currently part of the PM-JAY HBP) and other current treatment options. Results indicated that the use of ribociclib and palbociclib, in combination with fulvestrant, is not cost-effective in the Indian context.Citation28 Even with a 95% reduction in the price of these CDK4/6i agents, the combination therapy of palbociclib and fulvestrant remained cost-ineffective. The inclusion request for these agents was declined on the grounds of cost-effectiveness, implying that the cost of these treatments outweighs their potential benefits within the Indian health care system.

The Way Forward

Evidence published elsewhere has shown the role of cost and cost-effectiveness evidence in decisions on pricing or reimbursement rate setting.Citation29,Citation30 This emphasizes the pivotal role of cost and cost-effectiveness evidence in influencing health care decisions. Policy responses, however, should be prompt, to ensure the effective utilization of available evidence. Generating HTA evidence also requires resources and a need to balance the priorities of emergent policy issues. A potential strategy to enhance the responsiveness of HTA structures is through adaptive HTA (aHTA) methods.Citation31 aHTA involves adapting or leveraging existing evidence from international contexts to inform policy decisions, taking into account resource, data, time, and capacity limitations.

An assessment was undertaken to inform the application of aHTA methods for the PM-JAY.Citation32 This assessment showed that while health outcomes exhibit greater consistency across various settings, adapting healthcare costs proves challenging and their generalizability remains limited. However, aHTA helps prioritize topics, excluding interventions that significantly exceed cost-effectiveness thresholds. As a result, the HeFTA unit may first assess prioritized topics for their suitability by generating cost-effectiveness evidence using aHTA methods.

Determining the appropriateness of a specific topic for aHTA involves considering guiding principles in conjunction with the topic prioritization process. These guiding principles should take into account factors, such as the nature of the available evidence, the requirement for local data in the evaluation, the urgency or level of importance in making a decision about a particular technology, and the priority level assigned to the topic. Topics that are not deemed suitable for aHTA can be referred to the HTAIn for a comprehensive evaluation. This strategic approach conserves valuable time and resources that might otherwise be expended on conducting a full HTA for these interventions.

For future reforms, the NHA should focus its efforts on creating a conducive environment for strengthening institutional arrangements for strategic purchasing and price negotiations. Several countries have successfully attributed their achievements in UHC to the implementation of strategic purchasing.Citation33 Among the lower- and middle-income countries, the Thai health care system is one such example where the National Health Security Office acts as single purchaser to negotiate with suppliers of medicines and supplies over price given an assured quality.Citation34

The Indian health system has also witnessed successful examples of strategic purchasing and price negotiation that have led to improved health care outcomes and cost savings. One such example is the implementation of safety engineered syringes (SES) to address the problem of unsafe injection practices in various Indian states. Evidence on the cost-effectiveness of SES recommended a price reduction of approximately 54% to make it cost-saving, which led to the government engaging in price negotiations during bulk procurement, eventually leading to a significant reduction in the prices.Citation35

One of the strategies in using HTA evidence for negotiating prices under strategic purchasing contracts is to use value-based pricing (VBP), which considers the threshold price at which a new intervention becomes cost-effective or cost-saving.Citation36,Citation37 Given the context of health care financing in India and the large section of the Indian population that is not entitled to the PM-JAY coverage, there would be a significant impact if the HTA and VBP framework are also adopted for pricing decisions by the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority.Citation38 This will eventually help in nudging the overall health care market toward greater efficiency.

Finally, in light of the diverse needs across Indian states, it is essential to bolster capacity both within states and the HeFTA unit at the center. States in India possess the flexibility to adapt changes made by the NHA to HBPs to suit their specific requirements. However, due to limitations in local capacity for complex economic evidence appraisal, most states tend to accept the NHA’s recommendations.

Some states, such as Andhra Pradesh, proactively invest in local capacity building for HTA through the HeFTA unit. They recognize the importance of building expertise in HTA to support health insurance scheme implementation and the expansion of health care service packages. These proactive states collaborate with the NHA to enhance the capacity of their personnel. They aim to adopt HTA procedures to broaden service coverage and actively seek guidance from the NHA in this endeavor.

Conclusion

The establishment of the HeFTA unit signifies a critical advancement in creating transparent and robust decision-making mechanisms for the PM-JAY in India. However, as the health care landscape evolves, HeFTA must also evolve. Firstly, it is paramount to prioritize the augmentation of capacity within the HeFTA unit. This entails equipping the unit to proficiently conduct horizon scanning, generate, and comprehend HTA evidence, thereby aligning with the dynamic needs of stakeholders. Secondly, strengthening linkages between the HeFTA unit and the HTAIn is crucial to harness the expertise within both entities, ensuring robust evidence utilization in decision-making processes. Finally, the operationalization of the strategic purchasing and price negotiation framework within the NHA remains vital for optimal leveraging of HTA evidence. Within that, the integration of HTA and VBP can play a pivotal role in advancing health care financing reforms under the PM-JAY. By utilizing HTA evidence, decision-makers can assess the value, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of health technologies. This would enable better informed decision-making on inclusion or exclusion to HBPs, setting clinical guidelines, and revision of prices. On the other hand, VBP ensures that the prices of health care interventions align with the value they provide, promoting efficient resource allocation and patient-centered care. By embracing these approaches, health care systems can achieve rational resource allocation, enhance access to high-value interventions, and improve the overall sustainability and effectiveness of health care financing.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was sought by the Institute Ethics Committee, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India, vide letter no. IEC-09/2020-1174.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Shankar Prinja formerly served as the Executive Director of the National Health Authority, and Dr. Vipul Aggarwal formerly served as the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the National Health Authority, Government of India.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sharma A, Prinja S. Universal health coverage: current status and future roadmap for India. Int J Non-Commun Dis. 2018;3(3):78. doi:10.4103/jncd.jncd_24_18.

- Chalkidou K, Glassman A, Marten R, Vega J, Teerawattananon Y, Tritasavit N, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Seiter A, Kieny MP, Hofman K, et al. Priority setting for achieving universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Jun 1;94(6):462–9. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.155721.

- Prinja S, Kanavos P, Kumar R. Health care inequities in north India: role of public sector in universalizing health care. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:145–55.

- National Health Authority. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY). [accessed 2021 Aug 4]. https://pmjay.gov.in/about/pmjay.

- Lahariya C. ‘Ayushman Bharat’ program and universal health coverage in India. Indian Pediatr. 2018 Jun;55(6):495–506. doi:10.1007/s13312-018-1341-1.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Demand for grants 2023–24 analysis: health and family welfare [Internet]. New Delhi (India): PRS Legislative Research; 2023 [accessed 2023 Jun 1]. https://prsindia.org/budgets/parliament/demand-for-grants-2023-24-analysis-health-and-family-welfare.

- National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC). Ministry of health and family welfare, government of India. National health accounts: estimated form India 2019–20. [accessed 2023 Jun 1]. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/5NHA_19-20_dt%2019%20April%202023_web_version_1.pdf.

- Angell BJ, Prinja S, Gupt A, Jha V, Jan S. The Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana and the path to universal health coverage in India: overcoming the challenges of stewardship and governance. PLoS Med. 2019 Mar 7;16(3):e1002759. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002759.

- Downey LE, Mehndiratta A, Grover A, Gauba V, Sheikh K, Prinja S, Singh R, Cluzeau FA, Dabak S, Teerawattananon Y, et al. Institutionalising health technology assessment: establishing the medical technology assessment board in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2017 Jun 1;2(2):e000259. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000259.

- Health technology assessment in India: Department of health research. Ministry of health and family welfare, government of India. [accessed 2023 Sept 21]. https://dhr.gov.in/health-technology-assessment-india-htain.

- National Health Authority (NHA). About the National Health Authotity. [accessed 2023 May 27]. https://pmjay.gov.in/about/nha.

- National Health Authority. Provider payments and price setting under Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana Scheme (PM-JAY) in India: improving efficiency, acceptability, quality & sustainability. New Delhi (India): National Health Authority; 2022. p. 1–51.

- National Health Authority, Government of India, New Delhi. Volume-based to value-based care: ensuring better health outcomes and quality healthcare under AB PM-JAY. 2022. p. 1–38.

- World Health Organization. 2021. Principles of health benefit packages.

- Grieve E, Bahuguna P, Gulliver S, Mehndiratta A, Baker P, Guzman J. Estimating the return on investment of Health Technology Assessment India (HTAIn).

- World Health Organization. An assessment of the trust and insurance models of AB PM-JAY implementation in six states. India: World Health Organisation; 2022.

- Howell M, Walker RC, Howard K. Cost effectiveness of dialysis modalities: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019 Jun 1;17(3):315–30. doi:10.1007/s40258-018-00455-2.

- Afiatin KL, Kristin E, Masytoh LS, Herlinawaty E, Werayingyong P, Nadjib M, Sastroasmoro S, Teerawattananon Y. Economic evaluation of policy options for dialysis in end-stage renal disease patients under the universal health coverage in Indonesia. PLoS One. 2017 May 18;12(5):e0177436. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177436.

- Gupta D, Jyani G, Ramachandran R, Bahuguna P, Ameel M, Dahiya BB, Kohli HS, Prinja S, Jha V. Peritoneal dialysis–first initiative in India: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2022 Jan;15(1):128–35. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfab126.

- National Health Authority and National Health Authority. Policy document: peritoneal dialysis under AB PM-JAY. New Delhi: National Health Authority; 2022.

- Gupta N, Verma RK, Gupta S, Prinja S. Cost effectiveness of trastuzumab for management of breast cancer in India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 Feb;6(6):205–16. doi:10.1200/JGO.19.00293.

- Dong D, Naib P, Smith O, Chhabra S. Raising the bar: analysis of PM-JAY high-value claims.

- Huang EH, Tucker SL, Strom EA, McNeese MD, Kuerer HM, Buzdar AU, Valero V, Perkins GH, Schechter NR, Hunt KK, et al. Postmastectomy radiation improves locoregional control and survival for selected patients with locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and mastectomy. L Clin Oncol. 2004;22(23):4691–99. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.11.129.

- Gupta N, Chugh Y, Chauhan AS, Pramesh CS, Prinja S. Cost-effectiveness of post-mastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT) for breast cancer in India: an economic modelling study. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022 Sep 1;4:100043. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100043.

- Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, Fasching PA, Laurentiis MD, Im S-A, Petrakova K, Bianchi GV, Esteva FJ, Martín M, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):514–24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911149.

- Turner NC, Slamon DJ, Ro J, Bondarenko I, Im S-A, Masuda N, Colleoni M, DeMichele A, Loi S, Verma S, et al. Overall survival with palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(20):1926–36. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1810527.

- Prinja S, Dixit J, Gupta N, Mehra N, Singh A, Krishnamurthy MN, Gupta D, Rajsekar K, Kalaiyarasi JP, Roy PS, et al. Development of national cancer database for cost and quality of life (CaDcqoL) in India: a protocol. BMJ Open. 2021 Jul 1;11(7):e048513. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048513.

- Gupta N, Gupta D, Dixit J, Mehra N, Singh A, Krishnamurthy MN, Jyani G, Rajsekhar K, Kalaiyarasi JP, Roy PS, et al. Cost effectiveness of ribociclib and palbociclib in the second-line treatment of Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in post-menopausal Indian women. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2022 Jul;20(4):609–21. doi:10.1007/s40258-022-00731-2.

- Chauhan AS, Guinness L, Bahuguna P, Singh MP, Aggarwal V, Rajsekhar K, Tripathi S, Prinja S. Cost of hospital services in India: a multi-site study to inform provider payment rates and health technology assessment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Dec;22(1):1–2. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08707-7.

- Prinja S, Singh MP, Rajsekar K, Sachin O, Gedam P, Nagar A, Bhargava B, Naik J, Singh M, Tomar H. Translating research to policy: setting provider payment rates for strategic purchasing under India’s national publicly financed health insurance scheme. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021 May;19(3):353–70. doi:10.1007/s40258-020-00631-3.

- AHTA Process Guide. Tata Memorial Centre [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Jun 1]. https://tmc.gov.in/ncg/docs/pdf/AHTA%20process%20guide%20v2.0_final.pdf.

- Chauhan AS, Sharma D, Mehndiratta A, Gupta N, Garg B, Kumar AP, Prinja S. Validating the rigour of adaptive methods of economic evaluation. BMJ Glob Health. 2023 Sep 1;8(9):e012277. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012277.

- Vogler S, Haasis MA, Dedet G. Payers’ experiences with activities supporting value-based pricing: a systematic review. Value Health. 2021;24(3):436–46. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2020.11.006.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Thammatacharee J, Jongudomsuk P, Sirilak S. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan. 2015 Nov 1;30(9):1152–61. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu120.

- Bahuguna P, Prinja S, Lahariya C, Dhiman RK, Kumar MP, Sharma V, Aggarwal AK, Bhaskar R, De Graeve H, Bekedam H. Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic use of safety-engineered syringes in healthcare facilities in India. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020 Jun;18(3):393–411. doi:10.1007/s40258-019-00536-w.

- Claxton K, Briggs A, Buxton MJ, Culyer AJ, McCabe C, Walker S, Sculpher MJ. Value based pricing for NHS drugs: an opportunity not to be missed? BMJ. 2008 Jan 31;336(7638):251–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.39434.500185.25.

- Dang A, Mendon S, Desireddy P. Improving access to new treatments with value based pricing: an Indian perspective. PTB Rep. 2016;2(1). doi:10.5530/PTB.2016.1.1.

- Prinja S, Dixit J. Aushadh Sandesh: health technology assessment in India: implications for value-based pricing for drugs and devices. National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority. 2023 Apr. p. 2–6.