Abstract

This article builds on an earlier study of more than two decades of Australian work health and safety prosecutions and enforceable undertakings involving services for people with disabilities that identified lessons for disability service providers. Through a cross case thematic analysis of the 27 cases in the earlier study, we identify systemic work health and safety issues that are beyond the control of individual organisations. We identify seven issues for policymakers and regulators to consider in stewarding the evolution of work health and safety law and practice and which might be pursued by advocacy organisations in seeking change. First, regulators should not ignore work health and safety crimes against people with disabilities. Second, work health and safety interventions should emphasise the prevention of challenging behaviours not just their control. Third, a quadripartite approach - including the voices of people supported - should be adopted in work health and safety policy and legislation. Fourth, there needs to be greater awareness of the scope for third-party advocacy and third-party enforcement. Fifth, funders should at times bear the work health and safety consequences of their decisions. Sixth, legislation should allow beneficial arrangements for supporting people with very complex needs. Seventh, governments should have full legal liability for their criminal acts; the degree of liability of not-for-profits should continue to be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Australia’s work health and safety laws hold employers to account for work safety and empower workers to ensure their safety is protected. They have their origins in a catastrophic mine collapse in Wales (Committee on Safety and Health at Work, Citation1972). This model of “duties-based” regulation, based on the common law concept of a “duty of care,” was introduced 50 years ago when workplaces were predominantly male, unionised, and characterised by physical and chemical risks. However, the disability support sector to which it applies today faces very different challenges from those of heavy industry, and is characterised by a largely female, un-unionised workforce and a mix of physical, sexual and psychosocial risks, arising not only from the physical environments but also the challenge of supporting of individuals with complex needs, and externally-controlled funding (Hough et al., Citation2023).

An analysis of more than two decades of Australian work health and safety case law and enforceable undertakings relevant to disability support providers elicited nine lessons for the disability sector (Hough et al., Citation2023). That analysis gave insights and strategies for improving work health and safety performance by disability service providers. It also identified external or systemic factors impacting on disability service provision beyond the control of individual organisations. These included, issues of funding, incomplete information on incoming clients, inappropriate physical environments and staff shortages reflecting the general labour market shortages and the “Uberisation” of the disability support workforce (Macdonald & Charlesworth, Citation2021).

We take the sector-wide issues identified by Hough et al. (Citation2023) and identify systemic matters, external to organisations that must be considered in developing work health and safety laws, rules or programs better suited to the complexity of issues facing disability support providers and the predominantly community settings in which they deliver services. While such matters are largely the responsibility of policymakers and regulators, they are also relevant to advocates and activists seeking to influence systems change in the disability sector. For policymakers, the target audience is all parts of government, at both Commonwealth and State/Territory levels, with policy-setting responsibility over the lives of people with disabilities, particularly intellectual disabilities. For regulators, the target audience is agencies tasked with compliance and enforcement of laws that affect people with disabilities, including the development of enforcement strategies and expected standards of compliance conduct, particularly State and Territory based work health and safety regulators and nationally the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission.

Rather than repeat the detailed description of the work health and safety regimes available in Hough et al. (Citation2023), we summarise briefly the main points. All states and territories use the term “work health and safety” with the exception of Victoria, which uses “occupational health and safety.” Work health and safety regimes apply not just to workers but to anyone affected by activities in the workplace. Each state and territory has its own legislation, which is largely consistent with national model legislation (Model Law) (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). All the legislation is based around broad duties, placing the primary duty on the person conducting the business or undertaking (hereafter “the business”) to “ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety of workers” and “that the health and safety of other persons is not put at risk from work carried out” (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a, p. 17). The duty is breached when the risk of harm exists and is not addressed, not only after harm manifests, though prosecutions typically follow from an incident of actual harm.

Finally, we note, but will not seek to resolve here, a possible conflict of laws arising between the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 and state and territory work health and safety laws. Specifically, could compliance with one scheme (e.g., physically restraining a person with challenging behaviours to ensure worker safety) result in a breach of the other (e.g., use of a restrictive practice that was not authorised)? If so, could Section 109 of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act override the state-based safety law in favour of the Commonwealth Act? We will leave this for others to address.

Aims

We build on the Hough et al. (Citation2023) analysis to identify ways of strengthening work health and safety policy, legislation, and regulation applicable to disability support services. The use of prosecution and other tools for work health and safety enforcement in Australia have been guided by philosophical frameworks such as “responsive regulation” (Ayres & Braithwaite, Citation1992), which frame compliance and enforcement as graduated processes, applying regulatory responses appropriate to the circumstances. Most Australian regulators adopt “Ayres’ and Braithwaites” compliance and enforcement pyramid (Safe Work Australia, Citation2017). Responsive regulation suggests prosecution represents failure of the “lower order” regulatory tools (e.g., guidance, remedial notices), and possibly of the regulatory system itself, to achieve its objective of ensuring a safe and healthy workplace. By reviewing two decades of case law about prosecutions and enforceable undertakings we aim to identify from instances of what might be seen as regulatory failure, lessons for policymakers and regulators and thus the need for regulatory change. Using the body of work health and safety prosecutions and regulatory agreements from the disability service provision detailed by Hough et al. (Citation2023), the research objectives of this study are: (i) to identify and discuss systemic issues about policy and regulations arising from the history of enforcement; and (ii) suggest how the practice of work health and safety law enforcement may evolve in the area of disability support services.

Method

We build on Hough et al. (Citation2023), who undertook database searches to identify cases where work health and safety legislation had been enforced in disability service provision and used qualitative methods to analyse 27 cases from across Australia. We use the informal case names from Hough et al. (Citation2023), and, where cited, list these together with the formal names and citations in Appendix 1. We thematically analysed the 27 cases to identify issues raised expressly or otherwise repeated across multiple cases that indicated systemic deficiencies in the application of work health and safety law in the disability support sector. Each case was reviewed by the first and second authors, with consensus achieved on the common issues. We then evaluated the themed issues as starting points for policymakers and regulators to consider ways to improve outcomes for the health and safety of both workers and the people with disabilities they support.

Findings and discussion

We identified seven key issues for policymakers and regulators to consider.

Issue 1: Regulators should not ignore work health and safety crimes against people with disabilities

Since the 1972 Robens Report (Committee on Safety and Health at Work, Citation1972), the intention has been that work health and safety applies to anyone in a workplace. However, as Hough et al. (Citation2023) demonstrated, the focus in many prosecutions and the subsequent judgements was exclusively on harm to workers from the behaviour of one or more clients. Examples include the West Port High School, Burwood Road group home, Kurrambee School, Newcastle Special School, Mercy Centre Lavington and On Track Community Programs cases. Other clients, who were also victims of such behaviour, were largely invisible in the cases. For example, in the Kurrambee School case, the charges did not mention assaults by a student with a disability on other students with severe physical disabilities, who were unable to protect or defend themselves. Moreover, in many other cases clients were at potential risk of assault even if the risk was not realised. These work health and safety crimes against people with disabilities were routinely ignored in the charges and thus in the hearings, suggesting at the institutional-level a disregard of the harm experienced by people with a disability. Everyone in a workplace has a right to health and safety, not just workers. Arguably, the focus of regulators on harm to workers alone normalises violence experienced by people with disabilities, suggesting that violence and abuse are something that should be expected rather than be seen as criminal offences.

Issue 2: Work health and safety interventions should emphasise the prevention of challenging behaviours not just their control

The cases suggest that the rights of people with intellectual disabilities, including of those who demonstrate challenging behaviours, have been of secondary concern to regulators and courts. The decision in the Burwood Road group home case identified a “tension” between disability service legislation and safety duties, but concluded there was “authority for the proposition that the obligation to provide employees with a safe place of work takes precedence” (Keniry v Crown in Right of the State of NSW (Department of Community Services) [2002] NSWIRComm 349 at paragraph 37). The judgement cited a case from the mental health sector, Work Cover Authority NSW v Central Sydney Area Health Service ([2002] NSWIRComm 44). At paragraphs 89–90 the Court in this case described the “tension” starkly, concluding that “empathy, care and even pity for such patients are, however, not a proper basis upon which employees may be permitted to place themselves into danger.” These cases pre-date Australia's ratification in 2008 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) (United Nations, Citation2006), but the attitudes they convey likely remain. Concern is regularly raised about the overuse of restrictive practices as a means of minimising worker exposure to harm from clients’ challenging behaviours (Cameron, Citation2008; Chan, Citation2016) and the recent Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disabilities heard claims that restrictive practices were being too strongly weighted towards the management of safety risks (Spivakovsky et al., Citation2023).

In formulating regulatory responses to incidents of challenging behaviour that put the person and others in the workplace at risk of harm and condoning use of restrictive practices, work health and safety regulators need an understanding of, or access to, the specialist knowledge, interventions, and practice skills associated with supporting people with complex needs: including the underlying reasons for behaviour (which may be health, genetic, or environmental related), preventative strategies such as Active Support, and specialist interventions such as functional assessment and multi-element support plans (Bigby, Citation2024; Hogan & Bigby, Citation2024). Current levels of work health and safety regulators’ understanding of this complex area of human behaviour and professional practice is not at all clear, but the cases reviewed suggest it is at best only rudimentary, despite widespread acknowledgment of the potential harm from restrictive practices themselves (Spivakovsky et al., Citation2023). For example, in the Alfred Health case (WorkSafe Victoria, Citation2023), the Magistrate characterised the behaviour management plan of a person with severe autism and intellectual disability as part of the risk controls available to minimise risk to employees, including “the use of mechanical restraints, when necessary.” In our view, the benefit of supporting a safe system of work for the staff is only an ancillary purpose of such plans, with the primary purpose being to maximise the person’s quality of life by taking a person-centred approach to ensuring their support needs are fully understood and met through a blend of everyday and specialist support that is least restrictive of their rights. Mechanical restraints do not embody either a rights or person-centred approach, and may expose staff to greater harm overall by tending to escalate challenging behaviours. We are not suggesting worker safety should be compromised, but regulators do need to better understand how the combination of multi-faceted interventions such as Positive Behaviour Support, everyday practice such as Active Support and strong frontline management that incorporates Frontline Practice Leadership, should, by meeting the needs of a person with challenging behaviours, be the preferred means of reducing risks to workers. Diminishing behaviour support plans to mere risk control measures misses the opportunity of risk avoidance, which is higher on the risk control hierarchy underpinning work health and safety law objectives (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023b, ss. 35 & 36).

We note the issues we raise are yet to be properly argued before a court. For example, we are not aware of any case where the NDIS Commissioner for Quality and Safeguards or academics with relevant expertise have appeared to testify why a greater emphasis on quality of life and on preventative approaches are likely to produce superior health and safety outcomes than an emphasis on restrictive and hard controls. Further, we argue that, in the absence of human rights being recognised in law in all Australia jurisdictions, that work health and safety legislation should be amended to incorporate specific provisions that in relation to person-to-person risks in the human services, solutions should have regard to human rights principles. The legislation should direct all stakeholders, including work health and safety inspectors, to consider human rights when suggesting solutions and not jump to restrictive solutions such as restraint. Even for the two states and one territory that do have human rights legislation, it is not clear that those laws have effected change in work health and safety regulatory practice.

Issue 3: A quadripartite approach - including the voices of people supported - should be adopted

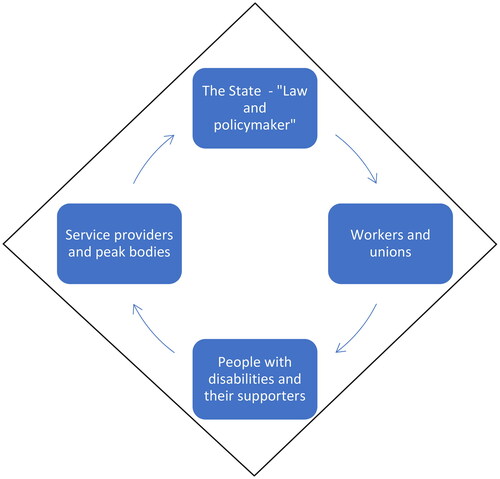

Power differences embodied in legal structures may be one explanation for enforcement of work health and safety law in favour of workers over others in the workplace. A key difference between the NDIS scheme and work health and safety legislation is that the latter embodies the tripartite (i.e., three party) arrangement between workers, employers, and government (Marsh, Citation2021). Workers enjoy real power in the relationship: for example, they must be consulted and have a right to be represented (ss. 47 and 50 of the Model Law) (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a). Failure to recognise these rights is a criminal offence. However, “other persons” in the workplace have no standing. The foundational text of Ayres and Braithwaite (Citation1992) promotes tripartism, namely involvement of the regulator, regulated and public interest groups, to avoid regulatory capture and to promote regulatory effectiveness. They express a preference (at p. 58) for a simple model of tripartism, where a single group represents the public interest, explicitly noting that trade unions are an appropriate group for work health and safety. However, they also acknowledge that the appropriate form of tripartism is contingent on a range of factors. Later work recognises that in applying this approach in human services, service users and family members should be included (), forming a quadripartite (i.e., four parties) approach of a regulatory diamond (Burford et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1. A quadripartite approach to promote regulatory effectiveness by including service users and family members to form a “regulatory diamond” (after Burford et al., Citation2019).

We can see no obvious reason why people with disabilities in a workplace, or indeed any client in any setting where there is likely to be a significant or ongoing relationship, should not have an equivalent voice to a worker. This is consistent with the mantra “nothing about us without us” and calls for partnering with consumers (i.e., clients) (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Citation2021). For service providers and other types of organisations, realising this goal and including the voices of people with disabilities is more challenging if their clients are people with intellectual disabilities than if their clients do not have cognitive impairments. Gaining insights from clients about risks in service provision involves abstract thinking and generalising from experience, for which many people with intellectual disabilities will require skilled individualised support and may be beyond the capacity of those with more severe impairment. Representative or consultative structures for clients with intellectual disabilities at the organisational level are still largely at the experimental stage; longitudinal research is needed about their efficacy and the elements that contribute or hinder their efficacy. It may not be realistic, at least in the current climate of limited resources, to expect disabled persons organisations to play the role that unions play for workers. However, the views of clients with intellectual disabilities might be supplemented by the experience and insights of family members and other allies (Burford et al., Citation2019). Policymakers and regulators must build the means of giving agency to supported people in a manner that is equal to that rightly conferred on workers. Better still, the tripartite concept that has underpinned work health and safety law governance for decades should be expanded to become quadripartite for sectors where human and worker rights are enmeshed.

Issue 4: Greater awareness of scope for third-party advocacy with scope for third-party enforcement

Australian work health and safety legislation (Safe Work Australia Citation2023a, s. 231; Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic.), s. 131) allows any person to request the regulator to prosecute serious offences if such action is not initiated within six months of an alleged breach. For example, Hough et al. (Citation2023) identified two cases where the regulator originally decided not to prosecute but subsequently changed its mind. The third-party request provisions allow persons, including “legal persons” such as disability advocacy groups and unions, to request a prosecution. This provision should be better publicised.

A classic issue in regulation is how to regulate corporations, given that, to quote an 18th Century Lord Chancellor, they have “no soul to damn and body to kick” (Coffee, Citation1981). One suggestion is to allow third-party enforcement as a way of multiplying “society’s enforcement resources and thereby increase the probability of detection” (Coffee, Citation1981, p. 435). Third-party enforcement of work health and safety has had a controversial history in some jurisdictions (Johnstone & Tooma, Citation2022), but introduction, or reintroduction in some instances might be considered in a way that enables advocacy of both workers and persons affected by workplace safety. It may also be a means of further empowering the disability advocacy sector to draw attention to the need for system change. We note that when Aotearoa New Zealand adopted Australia’s Model Law, the parliament included “private prosecutions” in its version of the legislation in addition to a right to third-party enforcement requests (Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (NZ), s 144).

Issue 5: Funders should bear some work health and safety consequences of their decisions

Work health and safety legislation does not merely apply at the point of production but has so-called “upstream” provisions in relation to various entities such as direct funders, whose decisions affect work health and safety even though they are not engaged in delivering a service (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a, ss. 19 - 26 of the Model Law). Direct funders of disability services have been held to have legal liability for their decisions that impact on work health and safety. For example, such liability was established in the Family and Community Services case and the Victorian Department of Families, Fairness and Housing case. Related to this is the requirement to ensure adequate resources within organisations: direct funders and service providers have due diligence requirements, including to ensure that the business “has available for use, and uses, appropriate resources … to eliminate or minimise risks to health and safety” (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a, s. 27(c)).

Arguably no such duties fall on indirect funders who are not conducting the relevant business or undertaking (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a, s. 19). Typically, the NDIA is an indirect funder. Providers that support NDIS participants with complex needs and have inadequate funding appear to do so at their peril and without recourse to the NDIA. Yet the NDIA plays a role in making decisions critical to work health and safety, as exemplified by the death of support worker Nischal Ghimire (Campbell & Dempster, Citation2019). In that case, Mr Ghimire drowned while supporting a child with a disability for a walk along a beach: it appears that the child went into the sea and Mr Ghimire met his fate while trying to pursue the child (who was subsequently found safe.) The NDIA had reportedly been requested to provide two workers to support the child in such activities (a 2:1 ratio of support), but declined to do so. Another example is supported independent living settings where having an appropriate roster of support can be critical to the safety of workers and clients. The NDIA (Citation2023) stated that as a matter of policy it refuses to deal directly with providers of these services about rosters.

Considering the duty of officers of disability support providers to ensure adequate resourcing of matters bearing on safety (s. 27, Model Law), there is a strong case for extending the “upstream” provisions of work health and safety legislation to indirect funders such as the NDIA and its officers. It may already be open for the Federal work health and safety regulator, Comcare, to contemplate liability of the NDIA. Work health and safety duties are not transferable (s. 14, Model Law), a person may have more than one duty and more than one person can concurrently have the same duty (s. 16). Importantly, Section 16(3)(b) makes clear that each person, in relation to a shared duty, must “discharge the person’s duty to the extent to which the person has the capacity to influence and control the matter or would have had that capacity but for an agreement or arrangement purporting to limit or remove that capacity” (emphasis added) (Safe Work Australia, Citation2023a, s. 16). Taking into account the ordinary meaning of words used in the Model Law, it may be open to a court to be satisfied that the NDIA conducts an undertaking in facilitating support for people with disabilities (s. 5), is bound by the laws as part of the Crown (s. 10), may share its duties with others, including providers (s. 16(1)). While it is clear that the NDIA would be subject to the Law for the purposes of its direct workers and contractors, whether or not it owes a duty to its participants may turn on whether a court considers the approval of funding for services represents “work carried out as part of the conduct of the … undertaking” (s 19(2)). Even if legislation does not currently extend to indirect government funders, as a matter of policy it is beyond question that supports funded through the NDIS should be sufficient to enable providers to undertake that task in a safe manner. It is a travesty that a participant or worker might be harmed as a result of inadequate funding and a worker or provider held liable under work health and safety legislation for unsafe supports, but for the NDIA to escape scrutiny.

We also note the analysis of Morris et al. (Citation2015) that government agencies are effectively monopsony purchasers, while the NDIA is not a direct purchaser, with the power to transfer the risk of the transactions from the government to providers (or the power to transfer risks to participants and workers.) As Morris et al. (Citation2015) argued “a calculated and appropriate response would be to allocate risk to the party best able to finance and/or manage it” (p. 390). We note that this party might vary. In some cases, it will be the participant, for example in the case of highly capable individuals with less complex needs (Yates et al., Citation2023). In other cases, it might be the provider, for example where the provider knows a client and their needs well and the funding is adequate. In some cases, it might be government, for example where the NDIA makes a judgment call on the nature and level of supports that is contrary to professional advice. As the provisions stand at the moment, it appears that if funding decisions of the NDIA result in serious harm or death to a worker or a person with a disability it is not the NDIA’s concern.

Issue 6: Legislation should allow beneficial arrangements for supporting people with very complex needs

A subset of people with disabilities have highly complex supports needs (Australasian Society for Intellectual Disability, n.d.; Dowse et al., n.d.) often compounded by long histories of fragmented and inadequate support (Office of the Public Advocate, Citation2018). A small subset of this group may have histories of physical or sexual violence towards other clients or workers, fire lighting, for example, or of forensic services. This group rarely receive the intensity, consistency, and continuity of support they need to reduce severely challenging behaviours and, prior to the NDIS, state governments were often the “provider of last resort” for them. In most jurisdictions, governments have relinquished their role in service provision and as providers of last resort.

The danger of a market approach is the tendency of providers with a strong profit-orientation to “cream” the participant pool, accepting only clients who are easy to support. Even providers committed to supporting people with complex needs may not accept new clients or if they do may fail to sustain them in community living because: they assess the risks as too high or the funding inadequate; coordination across multiple other providers associated with the client too challenging (e.g., one or other of a health provider, a support coordinator, or a supported independent living provider might not be discharging their responsibilities); or because decision-makers such as the client, plan nominees or guardians decline to use available funds to purchase essential equipment for the safety of the client or worker.

In supporting clients with the most complex needs, the prosecutions suggest that regulators are wise after the event but provide very limited proactive guidance for providers. For people with the most complex needs, it would be beneficial for regulators (both work health and safety regulators and the NDIS Commission) and the NDIA to work collaboratively with providers on designing solutions for keeping workers and clients safe. To recognise the challenge of providing support to people with the most complex needs, it would be possible for all parties to agree on an implementation plan, subject to regular review as circumstances evolve. If the provider adheres to the implementation plan and harm still results, there is a strong argument that, in the public interest of ensuring such clients have access to quality support, the provider (and others) should be free of the risk of prosecution. The concept we have in mind is akin to an enforceable undertaking, but with a preventative rather than reactive focus. Returning to our argument at the beginning of this article, resort to enforcement after the event is an example of regulatory failure; it would be much better to build the mechanisms for prevention and collaborative problem-solving.

Issue 7: Governments should have full legal liability for their criminal acts; the degree of liability of charities should continue to be decided on a case-by-case basis

Our final issue is one that is currently considered by courts on a case-by-case basis, but could also be addressed more systematically by policymakers: should not-for-profit organisations and governments be subject to lesser fines than for-profit organisations for similar offences?

The disability sector is, or at least was, characterised by a significant portion of non-government, not-for-profit service providers (Productivity Commission, Citation2011). This raises the question of whether or not a provider’s not-for-profit status should be taken into account in sentencing as any fine imposed is arguably at the expense of other potential beneficiaries of the organisation’s work. Government departments too have run this argument, most starkly in the Family and Community Services case. The Court summarised the Department’s submissions as follows:

In the event of the imposition of a fine in this matter, it will be paid from the expenses budget within the operating Division from which the liability arose. This will in turn have an impact on the activities that can be undertaken by the Department within that Division … There is presently funding for about 30% of children reported to be at risk to be responded to by way of a face-to-face assessment. (SafeWork NSW v Department of Communities and Justice (2021) NSWDC 259, paragraphs 96 and 99)

In relation to not-for-profit, non-government organisations, courts appear to have taken differing approaches about having regard to the status of an offender or its sensitive funding position, or both. In the On Track case, the Court stated at paragraph 195:

The defendant is a non-government, not-for-profit organisation doing outstanding and difficult work in the community. When combined with [other factors], the subjective considerations in the present matter must be considered to be high end and shall be given weight accordingly by the Court in sentencing. (On Track Community Programs Limited (2013) NSWIRComm 87)

The general purposes of sentencing are well settled: in exercising judicial discretion the court must have regard to the needs: to punish the offender; to provide specific deterrence (i.e., of the accused); to provide general deterrence (i.e., deterring others); to an offender’s prospects for rehabilitation; and to protect the community. We raise for consideration whether the circumstances of not-for-profit organisations and government should be considered as part of the mix of considerations.

On balance, the current approach may be appropriate, with discretion left to the courts. Not-for-profit organisations range in size and in their available resources: there will be some for whom imposing a significant fine will instantly force the organisation to cease trading and end support to all clients; in others, even a significant fine will have limited effect on overall financial performance. However, in the case of government departments we believe that there should never be a discounting of penalties in the way argued in the Family and Community Services case, nor do we consider it appropriate for government departments found guilty to make sentencing submissions seeking leniency on the basis of budget implications. To do so elevates the administrative decisions of public servants in Treasury above the views of legislators and judges about the appropriate range of penalties to be applied.

Limitations and further research

The limitations Hough et al. (Citation2023) acknowledged in their findings apply equally to this article. These include the possibility of missed decisions (although unlikely), the use of cases only to 2022, and limitations of using prosecutions and enforceable undertakings and not sources such as regulators’ improvement notices. Without access to these “micro” regulator decisions only the most extreme instances of health and safety failures are available for analysis. That said, we consider this an important cohort of real events from which lessons for improvement can and should be elicited.

Further research into the mental models adopted by regulatory decision-makers is needed to understand better their state of knowledge on the needs and opportunities in supporting disability support workers and the people they support. For example, do regulators understand and recognise the value of effective Frontline Practice Leadership as a part of a safe system of work that aims to benefit both the supported person and their supporters alike? The categorisation of challenging behaviours into the broader concept of workplace violence suggests there is much for safety regulators to learn about the opportunities of such safe systems. We are concerned that without a full understanding of the logic behind Positive Behaviour Support and Active Support, it is likely that safety regulators will see such systems as mere administrative controls sitting at the bottom of the hierarchy of risk controls, rather than the opportunity they present in eliminating the source of risk by delivering quality of life for the supported person.

Conclusion

As noted in the previous article, one striking feature of our analysis is just how few prosecutions have occurred and enforceable undertakings entered across time. In some states and territories, there have been none whatsoever about service provision to people with disabilities; indeed, in some jurisdictions rates of prosecution across all industries have been low. Many work health and safety crimes against workers and against people supported are likely to have been ignored. The issues identified and discussed in this article should be used to support improved approaches by policymakers and regulators to ensure people living with disabilities who are impacted by workplace harm or characterised as a cause of workplace harm are seen and properly understood. We note also that there are opportunities for disability advocacy organisations to engage with policymakers and regulators about many of these issues; in particular, in promoting possibilities of requesting prosecution where such action is not initiated by regulators (see Issue 4).

Regulators need to work actively to understand the complexities of workplaces that support people with intellectual disabilities. They need to recognise the protective intent of work health and safety laws for persons other than workers and consider breaches on equal standing with those that put workers at unacceptable risk. Regulators must make take the time to understand how meeting the needs of a person with an intellectual disability will often also achieve the prevention of harm that work health and safety laws seek to achieve. Advocacy organisations have a role to play in drawing the attention of regulators to these issues and holding them to account for the utilisation of knowledge about the complexity of the support needs of clients of disability support providers.

Both policymakers and regulators need to genuinely make space for the voices of people with intellectual disabilities and their supporters in developing and administering workplace safety law, ideally by expanding the existing tripartite club. Both should also look to encourage, expand, and improve third-party accountability on work health and safety risks that impact persons other than workers, including people with an intellectual disability, and also consider appropriate sentencing in the disability context. Policymakers need to recognise and accept that risk of harm can arise from insufficient funding and those making funding decisions need to be accountable for the consequences. Finally, adjustments to the broad-based duties that place primary responsibility on employers to minimise risks may need to be made for the disability context in order to give due regard to the human rights of people living with a disability and the expectations placed on support providers to deliver on such rights as well as protecting workers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australasian Society for Intellectual Disability. (n.d.). Position statement intellectual disability and complex support need.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2021). National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (2nd ed.). https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/national-safety-and-quality-health-service-standards-second-edition#:∼:text=The%20eight%20NSQHS%20Standards%20are%3A%201%20Clinical%20governance,management%208%20Recognising%20and%20responding%20to%20acute%20deterioration

- Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press.

- Bigby, C. (2024). Supporting engagement in everyday life at home and in the community: Active Support. In C. Bigby & A. Hough (Eds.), Disability practice: Safeguarding quality service delivery. Springer Nature.

- Burford, G., Braithwaite, J., & Braithwaite, V. (2019). Restorative and responsive human services. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429398704

- Cameron, G. (2008). No-man’s-land" between occupational health and safety legislation and the disability service sector. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 14(2), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY08019

- Campbell, C., & Dempster, A. (2019). NDIS criticised for “failing to provide second carer” in Nischal Ghimire drowning case. ABC News, January 11. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-11/ndis-criticised-for-failing-to-provide-second-carer/10707490#:∼:text=The%20drowning%20of%20a%20carer%20could%20have%20been,a%20carer%20drowned%20while%20on%20shift%20in%20Adelaide

- Chan, J. (2016). Challenges to realizing the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in Australia for people with intellectual disability and behaviours of concern. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(2), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2015.1039952

- Coffee, J. C. (1981). No Soul to Damn: No Body to Kick": An Unscandalized Inquiry into the Problem of Corporate Punishment. Michigan Law Review, 79(3), 386–459. https://doi.org/10.2307/1288201

- Committee on Safety and Health at Work. (1972). Safety and health at work: Report of the Committee 1970-72. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. http://www.mineaccidents.com.au/uploads/robens-report-original.pdf

- Dowse, L., Dew, A., & Sewell, A. (n.d.). Background paper for ASID position statement on intellectual disability and complex support needs.

- Hogan, L., & Bigby, C. (2024). Support for people with complex and challenging behaviour. In C. Bigby & A. Hough (Eds.), Disability practice: Safeguarding quality service delivery. Springer Nature.

- Hough, A., Bigby, C., & Marsh, D. (2023). Australian work health and safety enforcement regarding service provision to people with disabilities: lessons for service providers. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 10(2), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2023.2210580

- Johnstone, R., & Tooma, M. (2022). Work health and safety regulation in Australia. The Federation Press.

- Macdonald, F., & Charlesworth, S. (2021). Regulating for gender-equitable decent work in social and community services: Bringing the state back in. Journal of Industrial Relations, 63(4), 477–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185621996782

- Marsh, D. (2021). Disability versus work health and safety: a safe workplace and the right to an “ordinary life”: commentary on “Regulating disability services: the case of Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme quality and safeguarding system” (Hough, 2021). Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 8(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2021.1957706

- Morris, D., McGregor-Lowndes, M., & Tarr, J.-A. (2015). Government grants - an abrogation or management of risks?. In Z. Hoque & L. Parker (Eds.), Performance management in nonprofit organizations: Global perspectives (pp. 369–393). Routledge.

- National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) (2023). Supported independent living provider guidance. https://www.ndis.gov.au/providers/housing-and-living-supports-and-services/supported-independent-living-provider-guidance

- Office of the Public Advocate. (2018). The illusion of “Choice and Control”: The difficulties for people with complex and challenging support needs to obtain adequate support under the NDIS. https://www.publicadvocate.vic.gov.au/opa-s-work/research/211-the-illusion-of-choice-and-control

- Productivity Commission. (2011). Disability Care and Support, 2 report no. 54.

- Safe Work Australia. (2017). National compliance and enforcement policy. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/law-and-regulation/model-whs-laws/national-compliance-and-enforcement-policy

- Safe Work Australia. (2023a). Model Work Health and Safety Bill as at 1 August 2023. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-08/model-whs-bill-1_august_2023_0.pdf

- Safe Work Australia. (2023b). Model Work Health and Safety Regulations as at 1 August 2023. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/model-whs-regulations

- Spivakovsky, C., Steele, L., & Wadiwel, D. (2023). Restrictive practices: A pathway to elimination (Research Report), Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. The University of Melbourne, University of Technology Sydney, and University of Sydney. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2023-07/Research%20Report%20-%20Restrictive%20practices%20-%20A%20pathway%20to%20elimination.pdf

- United Nations. (2006). United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities

- WorkSafe Victoria (2023). Alfred Health. https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/prosecution-result-summaries-enforceable-undertakings

- Yates, S., Dickinson, H., & West, R. (2023). “I've probably risk assessed this myself”: Choice, control and participant co-regulation in a disability individualised funding scheme. Social Policy & Administration, 58(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12940

Appendix 1

Cases cited

The cases cited are in standard legal format, known as the medium-neutral format. The citation begins with the name of the case in italics, the year, the abbreviation of the court or tribunal’s name, and the court’s decision number for that year. To locate a case, go to a legal database and insert, for example, “[2006] NSWIRComm 10.” The informal case name is also given, as used in the article.

Campbell v SA Support Services Incorporated [2022] SAET 169: the SA Support Services case

Director of Public Prosecutions v The Crown in Right of the State of Victoria (Department of Families, Fairness and Housing and Victorian Person Centred Services Limited [2022] VCC 1221: the Victorian Person Centred Services cases

Hillman v Barossa Enterprises Inc. [2011] SAIRC 26: the Barossa Enterprises case

Inspector Davidson, WorkCover Authority v Northwest Disability Services Inc [2002] NSWCIMC 30: the Northwest Disability Services case

Inspector Keniry v The Crown in Right of the State of NSW (Department of Community Services) [2002] NSWIRComm 349; the Burwood Road Group Home case

Inspector Kilpatrick v The Crown in the Right of the State of New South Wales (Department of Education and Training) [2006] NSWIRComm 167: the Newcastle Special School case

Mercy Centre Lavington v Kristyn Thompson [2006] NSWIRComm 252; the Mercy Centre Lavington case

On Track Community Programs Limited [2013] NSWIRComm 87: the On Track case

SafeWork NSW v Snap Programs Ltd; SafeWork NSW v Department of Communities and Justice [2021] NSWDC 259: the Snap/FACS cases

The Crown in the Right of the State of New South Wales (Department of Education and Training) v Maurice O’Sullivan [2005] NSWIRComm 198; the Kurrambee School case

WorkCover Authority of NSW (Inspector Batty) v Crown in Right of the State of NSW (Department of Education and Training) [2000] NSWIRComm 181: the West Port High School case