ABSTRACT

ICTs are ubiquitous in today's digitised societies, but Responsible Innovation (RI) approaches are ill-equipped to address the liminal nature of ICT innovation. ICTs remain malleable after their diffusion. As a result, they are often in use and in development at the same time. This liminality has allowed developers to innovate by updating established ICTs and to incorporate information about the use of ICTs into their innovation. This clashes with RI approaches, which focus on emerging technologies and anticipation. We suggest three adaptations to overcome the gap between RI's anticipatory approach and the liminal innovation of ICTs: (1) RI must broaden its scope to include both emerging and established ICTs. (2) RI must focus on how developers monitor their in-use ICTs, as this information greatly influences innovation. And (3) RI must reflect on how to retrospectively care for issues with in-use ICTs, now that it is possible to update in-use ICTs.

Introduction

We live in a digital age. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) are everywhere around us (Sellen et al. Citation2009). They are part of the trains that we travel in, the energy systems that keep our houses warm and the smart devices that we carry with us every day. ICTs have shaped our health-care systems, our information diets, our communication and our entertainment. Simply put, ICTs are ubiquitous and are central to the world that we live in. At the same time, the significance of ICTs is accompanied by many issues, ranging from privacy issues (Baruh, Secinti, and Cemalcilar Citation2017) to problems with discrimination in artificial intelligence (Bozdag Citation2013; Buolamwini and Gebru Citation2018; Nkonde Citation2019), and from misinformation (Pelley Citation2021) to the manipulation of consumer behaviour (Zuboff Citation2019).

The pervasiveness of ICTs, their societal impact and their ethical issues all point towards the importance of aligning ICTs with the values, needs and expectations of societies. And indeed significant RI work has been put into making the innovation of ICTs more responsible (e.g. Aicardi, Reinsborough, and Rose Citation2018; Christie Citation2018; Regan Citation2021; Stahl et al. Citation2014b).Footnote1 In this regard, one of the most notable works is the Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation (FRRIICT) project (e.g. Eden, Jirotka, and Stahl Citation2013; Jirotka et al. Citation2017; Stahl et al. Citation2014a). This project developed the AREA + framework. This framework builds on existing RI frameworks, but it asks additional questions related to four unique aspects of ICT: the open-endedness of ICTs, the embeddedness of ICTs, the high pace of ICT development and the problem of many hands (Eden, Jirotka, and Stahl Citation2013; Jirotka et al. Citation2017).

We argue, though, that dominant RI approaches are not well-suited to the way ICTs are innovated. Dominant RI approaches are designed for situations where technologies are difficult to change after diffusion (e.g. Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020; Kupper et al. Citation2015; Owen et al. Citation2013; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), but with ICTs innovation typically continues after diffusion. Because ICTs can be both in development and in use at the same time, the innovation of ICTs is better understood as liminal innovation (Mertens Citation2018).

This liminality has had two main consequences for how ICTs are innovated: First, ICT developers use the liminality to incorporate information from the use of an ICT into its innovation. So, rather than extensively anticipating what might happen during use, as dominant RI-approaches prescribe (Barben et al. Citation2008; Nordmann Citation2014), ICT developers innovate by responding to what is happening (Fowler and Highsmith Citation2001; Mertens Citation2018; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2021). Second, ICT developers leverage the liminality of their ICTs to innovate by updating in-use ICTs, instead of releasing new products.

In the remainder of this article, we will develop suggestions for how RI scholars can adjust their approaches so that they are better suited for the liminal innovation of ICTs. First, we will elaborate what liminal innovation is and how it challenges dominant RI approaches. Then, we will go into the specifics of how liminal innovation is implemented in the ICT industry, before finally suggesting three adjustments that would make RI approaches better suited for the liminal innovation of ICTs.

Background

Anticipatory RI approaches

One of the defining features of RI is that it aims to govern innovation itself rather than to manage its risks or to retrospectively attribute blame (Felt and Wynne Citation2007; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). RI approaches do this in various ways, yet the one thing they almost all share is that they aim to intervene before an innovation is diffused (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020). This could be upstream (e.g. Jirotka et al. Citation2017; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013) or midstream (e.g. Fisher, Mahajan, and Mitcham Citation2006) or even during the diffusion of an innovation (Rip and Schot Citation2002; van de Poel Citation2017), but at least it is done before the innovation is used at scale. The aim of these interventions is to anticipate what futures the innovation might create and to have stakeholders take collective responsibility for these possible futures (Grinbaum and Groves Citation2013; Owen et al. Citation2013; Owen and Pansera Citation2019).

RI approaches focus on intervening early, because that is when innovations are most malleable (Rip and Schot Citation2002; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). Once innovations are diffused, path dependencies, lock-ins and entrenchments will have set in, which make the innovations hard to change (Collingridge Citation1980). This raises a dilemma of control (Collingridge Citation1980): either you intervene early – when innovations are still controllable but little is known about how they will play out – or you intervene late – when there is more information, but innovations are harder to control. By focusing on early interventions, RI approaches effectively side with the first option (Genus and Stirling Citation2018). The key to RI’s approaches has then been to deal with the lack of information through anticipation (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020; Nordmann Citation2014).

Critiques by liminal innovation scholars

Although RI’s anticipatory approach to governance has proven successful (Owen, von Schomberg, and Macnaghten Citation2021), some RI scholars have also criticised it. Mertens (Citation2018), Orlikowski and Scott (Citation2021) have argued that RI’s anticipatory approach does not work well for what they call liminal innovation. Liminal innovation refers to innovation that takes place while a technology is (sometimes partially) being implemented (Mertens Citation2018). So, with liminal innovation, technologies are in use and in development at the same time. Developers leverage the overlap between use and development to continuously incorporate information about the use of a technology into its innovation (Orlikowski and Scott Citation2021). This way, the implementation of a technology becomes central to its innovation, because the implementation teaches developers things they could only learn from the use of the technology (Mertens Citation2018; van de Poel Citation2017).

These liminal innovation practices go directly against Collingridge’s dilemma of control. With liminal innovation, developers can have control over an innovation and know about the effects of its implementation. Since RI’s anticipatory approach was designed with the dilemma of control in mind, Mertens (Citation2018) argues that it must be reevaluated in the context of liminal innovation. She suggests that for liminal innovation RI approaches must move ‘away from anticipation of the unknown and uncertain, and [return] to observation of the known and predictable’ (Mertens Citation2018, 1).

Liminal innovation of ICTs

The innovation of ICTs is a quintessential example of liminal innovation. Like other instances of liminal innovation, ICTs typically continue to be innovated after they have been diffused. Take Google Search for example, which was released in 1998 (Google Inc. Citation2015). Since its initial release, Google Search has gone through many major changes. Google added advertisements (Google Inc. Citation2000), they changed the search algorithm (Nayak Citation2019; Search Engine Land Citationn.d.) and they personalised search results (Kamvar Citation2005). Google made these updates while hundreds of millions of people were using Google Search.

The continued innovation of ICTs is not unique to Google Search. In fact, it is very common for ICTs to continue to be developed after they have been diffused. In a recent survey, 83% of 2657 ICT developers said that they continued to work on their products after they had been diffused (Puppet Citation2021). Almost all of these developers, 96%, even said that they updated their diffused ICTs at least once a week. These participants came from companies of all sizes – ranging from those with fewer than 99 employees to those with more than 50,000 employees – that were active in a broad range of industry segments, which illustrates just how commonplace the continued development of ICTs is.

Despite its widespread occurrence in the ICT industry, liminal innovation has received little attention in RI research on ICT innovation (e.g. Aicardi, Reinsborough, and Rose Citation2018; Christie Citation2018; Jirotka et al. Citation2017). This is problematic because, as Mertens (Citation2018) has argued, liminal innovation requires adaptations from RI frameworks. To address this gap, the next two sections of this article will elaborate how liminal innovation is implemented in the ICT industry, what challenges this poses for RI frameworks and how RI might adapt to solve these challenges.

Liminal innovation in the ICT industry

The malleability of ICTs

Liminal innovation allows technologies to remain malleable after implementation. With ICTs this malleability arises from servers. Servers are remote computers that are under direct control of the developers of an ICT. ‘Remote’ refers to the fact that these computers are in data centres, away from the user using the ICT (in contrast to the local computer that users use to run an ICT). Most ICTs run partly on servers and partly on the computers of users. For instance, when you type a search query in Google Search, the typing of the query is handled on your own computer, but the search results are calculated on a Google server.

The advantage of servers is that they remain under the control of developers. First, this means that developers can continue to change the software that runs on a server even if the ICT itself is diffused. Since the server partly determines how the ICT functions, any changes made to the server will immediately change the ICT for all users. Second, developers can use servers to send updates that will change the local components of a user’s ICT, for example when we are asked to reboot our phone or computer to update our operating systems.

The ICT industry has translated this malleability into two key liminal innovation practices: (1) innovation by updating ICTs rather than releasing new ones, and (2) the incorporation of information about the use of an ICT into its innovation. Both these practices present challenges and opportunities for RI research.

Innovation through updates

A significant part of the innovation of ICTs is done by updating established ICTs, rather than releasing new ones. Take Microsoft Office as an example. You used to have to buy a new version of Microsoft Office every few years to get updates. Now you can subscribe to Microsoft 365 and the applications that you use will be automatically updated. Effectively, ICTs are delivered as fluid services, rather than static products (Turner, Budgen, and Brereton Citation2003), hence why this practice is often referred to in industry as ‘Software as a Service’ (Kim, Jang, and Yang Citation2017).

For developers the advantage of updating established ICTs is that it allows them to release an update as soon as it is ready, because they do not have to wait for there to be enough updates to warrant a new product. Moreover, updating an established ICT guarantees that the updates will be adopted by everyone who uses the ICT, since the adoption does not rely on the users purchasing a new product. Together, the quick diffusion and guaranteed adoption of updates make it easier for developers to respond to changing environments (Digital.AI Citation2020). If a new algorithm becomes available, then developers do not have to wait to implement it. If stakeholders are dissatisfied with a feature, then developers can quickly remove it. And if there is a mistake with an ICT, then developers can swiftly fix it.

This innovation through updates matters for RI, because a lot of the novelty, disruption and issues within the ICT industry stem from changes that were made to in-use ICTs. Google Search is again a prime example of this. At the time of writing, most of the societal issues with Google Search are raised by changes that were made after Google Search was implemented. Google’s collection of data has raised privacy issues (Cyphers and Gullo Citation2020), Google’s use of targeted advertising has raised issues regarding the manipulation of users (Zuboff Citation2019), and the personalisation of search results has raised issues regarding filter bubbles (Pariser Citation2011). Established RI approaches though mostly focus on emerging technologies and would therefore miss these post-diffusion changes and the issues they raise (Joly Citation2015; Owen and Pansera Citation2019).

Monitoring and experimentation

The second key liminal innovation practice in the ICT industry is the incorporation of information from the use of an ICT into its development. As, Mertens (Citation2018) as well as Orlikowski and Scott (Citation2021) have shown, this is not unique to the liminal innovation of ICTs, but the ICT industry does place a particularly high value on learning from use (Alnafessah et al. Citation2021; Feitelson, Frachtenberg, and Beck Citation2013; Forsgren Citation2018; Forsgren and Humble Citation2016). Already in the early 2000s, the ICT industry shifted away from waterfall methods of innovation, which relied on extensive planning and anticipating what might happen, to agile methods, which instead emphasise experimentation and reacting to what is happening (Fowler and Highsmith Citation2001). There are common development philosophies like ‘release early, release often’, which encourage developers to release new products or features as soon as possible, even if they might contain errors, just to get feedback from customers (Raymond Citation1999). Often though feedback is already gathered before a new feature is even released. Developers for example perform A/B tests, where they deploy a potential feature to a subset of their users to compare its performance with the current live version of the software (Xu et al. Citation2015). If the update turns out to be undesirable, then the developers can simply revert it.

To obtain all this information about the use of ICTs, the ICT industry has developed a sophisticated monitoring infrastructure to obtain this information. By monitoring we mean any process that provides information about how an ICT performs as it is being used. This can be an ICT’s technical performance, its security, but also its societal desirability.

Typically, companies combine all kinds of monitoring methods, from collecting operational data, to conducting user surveys and interviews (Govind Citation2017; Schendel Citation2018). One of the most common monitoring techniques though is to look at the behaviour of users. Companies use this behavioural data to infer, for instance, whether users are running into problems while using their ICTs or whether the behaviour of users matches the intentions of the company. There are significant differences in the type of behavioural data that companies collect, depending on their (ethical) considerations and the type of ICT that they are developing. In general, though, companies tend to collect dozens of data points about their users, which range from data about the time that users spend using their ICTs to data about the things that users click on and the interactions that users have with other users (Vigderman and Turner Citation2022).

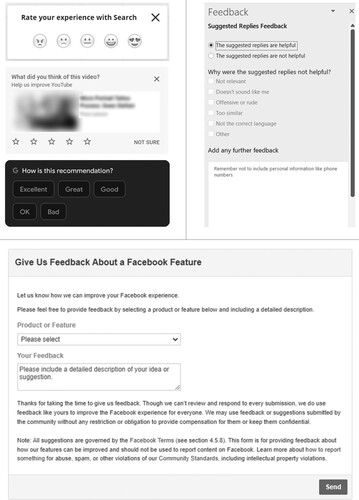

Besides user behaviour, ICT companies also monitor user opinions. This typically involves active participation from users. Some ICTs have, for example, built in ways for users to give feedback. This could be a small pop-up with emojis that asks users whether they liked their video recommendations, a survey, or a dedicated forum where users can post their complaints (see ). Some companies also invite users to participate in interviews, focus groups or ethnographic studies so that they can ask them about their experiences and opinions (Brogan Citation2015; Product Peas Citationn.d.).

Since information about the use of ICTs plays such a critical role in the innovation ICTs, how companies monitor their ICTs can greatly affect how their ICTs are innovated. Therefore, responsible monitoring practices are key to the responsible innovation ICTs. This however challenges current anticipatory RI approaches, which focus emphasise responsible anticipation rather than responsible monitoring (Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020; Mertens Citation2018).

At the same time, the liminality of ICTs also presents new opportunities for RI. In the same way that ICT developers incorporate information about the use of an ICT into its innovation, RI scholars could also incorporate information about the use of ICTs into their interventions. In other words, the liminal innovation of ICTs gives RI scholars the opportunity to perform retrospective RI. This would involve RI scholars looking at ongoing issues with in-use ICTs and aiming to retrospectively take care of these issues.

Adapting RI to the liminal innovation of ICTs

We have shown that the innovation of ICTs can be best understood as liminal innovation and that the liminality of this innovation challenges dominant RI approaches. In line with earlier work on liminal innovation (Mertens Citation2018), we argue that RI approaches must be adjusted to address these challenges and to become better equipped for liminal innovation. In what follows, we illustrate how to recognise these challenges in ICT innovation and offer suggestions for how RI scholars can address them.

The responsible innovation of established ICTs

As demonstrated in Section ‘Innovation through updates’, innovation in the ICT industry does not have to come from the release of new products. Some of the most impactful innovation in the ICT industry was done by updating established ICTs. This challenges traditional RI approaches, which have primarily focused on emerging technologies (Joly Citation2015; Owen and Pansera Citation2019). To capture the full breath of innovation in the ICT industry, RI must broaden its scope to include emerging as well as established ICTs. This means that RI scholars must inquire into established ICTs, identify emerging features and engage with the development of those features. Such interventions can be anticipatory, as RI scholars have done for emerging technologies, or retrospectively, as we will discuss in the next subsection.

Retrospective RI

We showed in Section ‘Monitoring and experimentation’ that ICT developers leverage the liminality of ICTs to incorporate information about the use of an ICT into its innovation, but that this also presents a chance for RI scholars to perform retrospective RI. This form of retrospective RI would not rely on managing the risks of ICTs or on regulating their use, like previous forms of retrospective innovation governance have (Owen et al. Citation2013). Instead, it would involve addressing issues with in-use ICTs by changing the very ICTs that are being used. The advantage of retrospective RI is that it would allow scholars to learn how an ICT is embedded in society, what impacts it has had and what problems it has caused, before intervening in the ICT. This information is simply not available during the upstream interventions that RI scholars currently use (van de Poel Citation2017). Yet with this information, RI scholars would be better able to determine what ICTs require most attention and which aspects of those ICTs might need changing.

Retrospective RI breaks with the Collingridge dilemma. As we covered in Section ‘Background’, the Collingridge dilemma is the reason why RI scholars predominantly rely on anticipatory interventions that take place before an innovation is diffused. With retrospective RI however, scholars are no longer limited to anticipating what might happen as they can now also react to what has happened or is happening.

As such, retrospective RI offers a new starting point for interventions. RI scholars can now actively respond to societal problems with in-use ICTs and specifically select those ICTs that have negatively affected societies. There are many such ICTs today. This includes chatbots that spread disinformation, like ChatGPT (Bell Citation2023), social media that harm the body image of teens, like Instagram (The Wall Street Journal Citation2021), and search engines that create filter bubbles, like Google Search (Pariser Citation2011). These established ICTs and their respective issues currently receive very little attention from RI scholars, despite the fact that these ICTs are still being innovated and are still malleable.

The possibility to retrospectively intervene in ICTs does not make anticipatory interventions obsolete. First, non-diffused ICTs will have less path dependencies and will thus be more malleable. Therefore, anticipatory interventions can more effectively challenge the goals and motivations behind an ICT. Second, since anticipatory interventions hit before a technology is diffused, they can prevent negative impacts from ever happening. This is particularly important when there are potential impacts that could cause great harm. And lastly, retrospective RI-interventions are not just retrospective. They have an anticipatory component to them as well. Retrospectively intervening will for instance also require anticipating what the consequences of the intervention will be.

It does however raise a tough question for RI scholars who work on ICTs: how do you choose between anticipatory interventions and retrospective interventions? Do you focus on established ICTs with the most significant negative impacts, knowing that they might be harder to change? Or do you focus on emerging ICTs, because although you are not sure whether they will be adopted, you do know that you can have a significant impact on their innovation? We do not think that there are universal answers to these questions or that RI scholars must pick just one of these options. Anticipatory and retrospective interventions should coexist and complement each other. However, given that almost all RI interventions are anticipatory at the time of writing, we would encourage RI scholars to focus more on retrospectively intervening in the innovation of problematic in-use ICTs.

Responsible monitoring

In Section ‘Monitoring and experimentation’, we established that monitoring the use of ICTs plays a critical role in innovation of ICTs. As a result, RI scholars who seek to make the innovation of ICTs more responsible, must pay close attention to the monitoring that is done during an ICT’s innovation, and they must develop visions for how this monitoring can be done more responsibly.

This differs from previous pleas for monitoring in RI literature, which have stressed the need for RI scholars to monitor the emerging effects of innovations (e.g. Boenink, Van Lente, and Moors Citation2016; Guston and Sarewitz Citation2002; Nordmann Citation2014). While continuous monitoring is indeed important for liminal innovation (Mertens Citation2018), ICT companies already monitor the effects of their ICTs a lot. The goal for RI should therefore be to investigate the monitoring that is done by ICT companies and try to make their monitoring practices more responsible.

Although ICT companies often monitor their ICTs extensively, significant concerns have been raised about how they monitor their ICTs. Scholars from critical data studies for instance have criticised corporate monitoring for its narrow focus on financial gains (Dalton, Taylor, and Thatcher Citation2016). They see the monitoring by ICT companies as a core component of surveillance capitalism, where the companies monitor the behaviour of users just to learn how they can get users to click on more ads, buy more products and spend more time on their ICT (Zuboff Citation2019). Others have criticised monitoring for infringing the privacy of users (Acquisti, Brandimarte, and Loewenstein Citation2015), for its role in the discrimination of minorities (Cagle Citation2016), and for exacerbating power imbalances between data subjects and those who collect the data (Andrejevic Citation2014). The important task of RI scholars is to ensure that monitoring serves societal needs and values, and not just the needs of the companies developing the ICTs.

Although it is therefore important to ensure that monitoring is done responsibly, current RI approaches pay little attention to this monitoring. To better accommodate monitoring in the innovation of ICTs, RI scholars must conduct more empirical studies into the monitoring practices of ICT companies so that they can develop a more comprehensive image of the monitoring techniques that are used in the ICT industry and the issues they raise.

Additionally, RI scholars should develop a vision of what would make the monitoring practices of the ICT industry more responsible. When it comes to anticipation, inclusion, reflexivity and responsiveness, there are vast bodies of RI literature that discuss best practices. However, this is somewhat missing with regards to monitoring. Especially, when it comes to the particularities of monitoring in the ICT industry.

The goal of this section is to kickstart this discussion. To do so, we highlight three aspects that are important to consider when developing a framework for responsible monitoring in the ICT industry: the types of issues that are monitored, the representation of these issues and the protection of the data used for the monitoring. These are by no means the only monitoring aspects to consider, but we think that they are particularly important as they have all been sources of societal concerns. The three aspects are developed further below.

Variety of impacts

First, RI scholars must consider the impacts that are monitored for. Responsible monitoring should ideally keep track of all types of impacts, not just bugs and usability issues, but also the societal, ethical, legal and environmental issues raised by ICTs. This mirrors RI’s criterion for anticipation, which is that anticipation should anticipate many different aspects of the future (Barben et al. Citation2008; Kupper et al. Citation2015).

Since it is impossible to monitor an ICT for all possible issues, monitoring should focus on those impacts that are either likely to happen or problematic when missed. Because it is likely that some unexpected issues will show up, an appropriate infrastructure should be available for stakeholders to retrospectively put issues on the agenda that were not anticipated and thus not actively monitored for. Such open-ended monitoring can be done through, for instance, forums, feedback forms or regular meetings with stakeholders.

Representation of issues

When it comes to monitoring-related issues, it is not just important what issues are monitored but also how those issues are represented. Following the work of Latour (Citation2005), we use representation here to refer to both the representation of stakeholders, i.e. those whose interests are included in the monitoring, and the representation of the stakeholders’ interests, i.e. how the monitoring impacts the interests of the stakeholders.

In terms of the representation of stakeholders, it is important that the monitoring covers the interests of a diverse and inclusive set of stakeholders. Inclusion and diversity are longstanding pillars of RI (e.g. Fraaije and Flipse Citation2020; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), and many of the existing arguments for inclusion also apply to monitoring. From a democratic perspective, inclusive monitoring is the right thing to do, as it allows those who are affect by the ICT to also have a say in how the ICT is designed (Owen et al. Citation2013). Moreover, including diverse stakeholders can also increase the quality of decision-making by opening it up to a broader range of perspectives, values and knowledge (Kupper et al. Citation2015).

To realise this inclusion, RI scholars typically rely on deliberative methods (Brand and Blok Citation2019). Through these deliberative methods, stakeholders can become responsive to one another and find common ground (Blok Citation2014). These methods create the capacity for stakeholders to articulate differences and collectively work through them, which will be important for responsible monitoring as there will probably be diverging perspectives on what issues an ICT has and how to solve them.

Deliberative methods can be difficult to implement at scale, though. That is a problem, because some of the largest and most problematic ICTs, like Facebook, TikTok and Google, have hundreds of millions of users across the world. Representing such a huge population in a deliberative setting while doing justice to their diversity is anything but easy. The relevant processes would also have to deal with the fact that these users are not only in different global locations but also live in different time zones and speak different languages.

Partly for these reasons, ICT companies themselves do not rely on extensive deliberation. Instead, they tend to make decisions based on large quantities of data that they collect about the behaviour of their users (Zuboff Citation2019). The advantage of using behavioural data is that it can represent the needs of all users, because companies can easily collect data about all its users. This method therefore largely avoids the challenge of monitoring at scale. Moreover, behavioural data comes in quickly and continuously and is relatively easy to interpret using statistical methods.

While the use of behavioural data for monitoring is popular and has clear advantages, it is also accompanied by significant problems. First of all, collecting all this personal data raises major privacy-related issues, and using it could even be considered exploitative given that it is ultimately data that is produced by users (Couldry and Mejias Citation2019). There are also problems with how behavioural data represents the interests of stakeholders. Behavioural data measures behaviour and thus represents the interests of users in the form of their behaviour. There are, however, many cases in which a person’s behaviour might not reflect their interests. Someone might, for instance, buy a product because an advertisement persuaded them to, but then regret the purchase afterwards. Behavioural data is used to make such persuasion more persuasive. If you know how people behave, it is easier to know how to manipulate that behaviour (Zuboff Citation2019). Behavioural data can therefore be used to make users act in ways that go against their own interests rather than representing those interests. This highlights the tension between the two forms of representation: while behavioural data ensures that everyone who uses an ICT is represented, it is not good at representing their norms, values and intentions.

From an RI perspective, though, we do want these ICTs to reflect the values, norms and expectations of stakeholders (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). That does not necessarily mean that we should aim to get rid of all monitoring that is based on behavioural data, since behavioural data can be a very valuable way of dealing with scale and representation. However, as RI scholars we should strive to make the collection and use of such data as responsible as possible. To do so, we recommend that RI scholars draw from the important work that is done in critical data studies (e.g. Boyd and Crawford Citation2012; Dalton, Taylor, and Thatcher Citation2016). Moreover, RI scholars should look to supplement quantitative, behavioural monitoring with more qualitative, deliberative forms of input, like the methods that RI scholars use to deliberate anticipated issues (Robinson Citation2009).

Privacy

Finally, monitoring implies the collection of a lot of data, from behavioural data to the responses of users to surveys and data from focus groups and ethnographic user studies (Fabijan et al. Citation2018; Govind Citation2017; Liou, Zheng, and Anand Citation2022). RI attempts to make monitoring more responsible must consider how to protect this data and respect the privacy of users.

Privacy issues concerning ICTs have received a lot of attention from scholars (Stahl, Timmermans, and Mittelstadt Citation2016), including RI scholars (Stahl Citation2013; Stahl and Wright Citation2018; Stahl and Yaghmaei Citation2016). However, these articles mostly discuss how ICTs use personal data. What we want to stress here is that it is also important to consider how personal data is used in the innovation of these ICTs. This would not require radically new approaches or privacy principles, just the application of those approaches and principles to monitoring practices as well.

Given the attention that privacy has received, there are many valuable works that could serve as inspiration for RI’s privacy criteria for monitoring. We do not have the space here to do justice to the full breadth of ongoing privacy-related discussions, but we will highlight two influential approaches to privacy that align well with the ambitions of RI.

One of the most influential approaches to privacy in academia is contextual integrity (Nissenbaum Citation2009). In contextual integrity, privacy is not about achieving secrecy or anonymity (McGuigan and Nissenbaum Citation2021). Instead, contextual integrity aims to develop data flows that align with the expectations, norms and goals of data subjects and society at large. Which data flows are appropriate depends on the context, since each context will have its own norms. For instance, we consider it to be appropriate for marriage councillors to know about our romantic engagements, but we would not want that data to be used by insurance companies to adjust our premiums. Contextual integrity means that RI scholars would have to first identify people’s privacy norms regarding the ICT that they are working on and then ensure that the monitoring practices for that ICT align with these norms or strengthen them.

A common way to implement such privacy norms is through privacy by design. The idea of privacy by design is to make privacy an integral part of organisational priorities, project objectives, design processes and planning operations (Cavoukian Citation2010). This includes considering privacy during the initial design phase of ICTs (Wong and Mulligan Citation2019). The focus on organisations and prospection makes privacy by design a good fit for RI, as it aligns well with RI’s focus on anticipatory governance. Furthermore, privacy by design has been adopted in several privacy guidelines and regulations, including the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (Rubinstein and Good Citation2013; Stahl and Yaghmaei Citation2016) and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s policy recommendations (Wong and Mulligan Citation2019). Most ICT developers will therefore already be familiar with the concept. RI scholars must watch out for common tendencies to narrow the scope of privacy by design, though, which occurs when engineers and governments treat privacy by design as a checklist approach that is focused on anonymity and control over data (Gürses, Troncoso, and Diaz Citation2011). Instead, privacy norms should be context dependent, and privacy by design should be the ‘productive space’ where differences in norms and interests are negotiated (Gürses, Troncoso, and Diaz Citation2011).

Conclusion

In this article, we showed that ICTs typically remain malleable after diffusion and that the ICT industry uses this to continue to innovate ICTs as they are being used. In the ICT industry this has led to two key liminal innovation practices: the practice of innovating by updating established ICTs and the practice of incorporating information about the use of an ICT into its innovation.

In line with earlier work on liminal innovation (Mertens Citation2018), we have argued that such liminal innovation challenges dominant RI approaches, but that these challenges have not been reflected in existing RI approaches for ICTs. To make these RI approaches better suited for the liminal innovation of ICTs, we have proposed three major adjustments. First, RI scholars should broaden their scope beyond emerging technologies and start intervening in the innovation of established ICTs as well. Second, RI scholars must develop a retrospective RI approach, where the goal is to retrospectively care for existing issues with ICTs. And finally, RI scholars must pay attention to the monitoring practices of ICT companies to ensure that the monitoring measures a variety of impacts, offers a fair representation of the issues and stakeholders involved, and respects the privacy of users.

With this article, we shined a light on the use of liminal innovation in the ICT industry and aimed to start a discussion on what these practices should mean for RI. The recommendations in this article provide a first step towards making RI approaches more suited for the liminal innovation of ICTs. However, we strongly encourage RI scholars to take our contributions and develop them further. Further development requires (1) more empirical studies into the liminal innovation of ICTs to learn about common practices and problems; (2) further reflection on what constitutes responsible monitoring in the ICT industry; and (3) careful consideration of how to balance anticipatory responsibilities with retrospective responsibilities now that there are more opportunities for RI scholars to react to the consequences of in-use ICTs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the constructive feedback from the anonymous reviewers. This has significantly helped to improve our manuscript and enhance the quality of our work. We would also like to thank Dr. Eelco Herder and prof. Dr. Arjen de Vries for their insightful comments during the writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For the sake of scope, we limit ourselves to RI in this article, although RI is by no means the only framework that is used to make ICTs more responsible. One of the other main frameworks used in relation to ICTs is value-sensitive design. See van den Hoven (Citation2013) for an overview of value-sensitive design and how it compares to RI (for ICTs).

References

- Acquisti, Alessandro, Laura Brandimarte, and George Loewenstein. 2015. “Privacy and Human Behavior in the Age of Information.” Science 347 (6221): 509. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1465.

- Aicardi, Christine, Michael Reinsborough, and Nikolas Rose. 2018. “The Integrated Ethics and Society Programme of the Human Brain Project: Reflecting on an Ongoing Experience.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (1): 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2017.1331101.

- Alnafessah, Ahmad, Alim Ul Gias, Runan Wang, Lulai Zhu, Giuliano Casale, and Antonio Filieri. 2021. “Quality-Aware DevOps Research: Where Do We Stand?” IEEE Access 9:44476–44489. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3064867.

- Andrejevic, Mark. 2014. “The Big Data Divide.” International Journal of Communication 8:1673–1689.

- Barben, Daniel, Erik Fisher, Cynthia Selin, and David H. Guston. 2008. “Anticipatory Governance of Nanotechnology: Foresight, Engagement, and Integration.” In The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies, edited by Edward J. Hackett, Olga Amsterdamska, Michael Lynch, and Judy Wajcman, 987–1000. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Baruh, Lemi, Ekin Secinti, and Zeynep Cemalcilar. 2017. “Online Privacy Concerns and Privacy Management: A Meta-Analytical Review: Privacy Concerns Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Communication 67 (1): 26–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12276.

- Bell, Emily. 2023. “A Fake News Frenzy: Why ChatGPT Could Be Disastrous for Truth in Journalism.” The Guardian, March 3, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/mar/03/fake-news-chatgpt-truth-journalism-disinformation.

- Blok, Vincent. 2014. “Look Who’s Talking: Responsible Innovation, the Paradox of Dialogue and the Voice of the Other in Communication and Negotiation Processes.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (2): 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2014.924239.

- Boenink, Marianne, Harro Van Lente, and Ellen Moors. 2016. “Emerging Technologies for Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease: Innovating with Care.” In Emerging Technologies for Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease, edited by Marianne Boenink, Harro Van Lente, and Ellen Moors, 1–17. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54097-3_1.

- Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. 2012. “Critical Questions for Big Data: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

- Bozdag, Engin. 2013. “Bias in Algorithmic Filtering and Personalization.” Ethics and Information Technology 15 (3): 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-013-9321-6.

- Brand, Teunis, and Vincent Blok. 2019. “Responsible Innovation in Business: A Critical Reflection on Deliberative Engagement as a Central Governance Mechanism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (1): 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2019.1575681.

- Brogan, Jacob. 2015. “The Case of the Ornamental Anthropologist: How Netflix Puts a Human Face on Big Data.” Slate. https://slate.com/technology/2015/05/netflix-tries-to-put-a-human-face-on-big-data-with-its-own-anthropologist.html.

- Buolamwini, Joy, and Timnit Gebru. 2018. “Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification.” Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 81:1–15. ACM.

- Cagle, Matt. 2016. “Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter Provided Data Access for a Surveillance Product Marketed to Target Activists of Color.” ACLU NorCal (blog), October 11, 2016. https://www.aclunc.org/blog/facebook-instagram-and-twitter-provided-data-access-surveillance-product-marketed-target.

- Cavoukian, Ann. 2010. Privacy by Design: The 7 Foundational Principles: Implementation and Mapping of Fair Information Practices. Toronto, ON, Canada: Information & Privacy Commissioner of Ontario.

- Christie, Gillian. 2018. “Progressing the Health Agenda: Responsibly Innovating in Health Technology.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (1): 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2017.1290493.

- Collingridge, David. 1980. The Social Control of Technology. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

- Couldry, Nick, and Ulises A. Mejias. 2019. “Data Colonialism: Rethinking Big Data’s Relation to the Contemporary Subject.” Television & New Media 20 (4): 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632.

- Cyphers, Bennett, and Karen Gullo. 2020. “Inside the Invasive, Secretive “Bossware” Tracking Workers”. Electronic Frontier Foundation 20. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/06/inside-invasive-secretive-bossware-tracking-workers?ref=nodesk.

- Dalton, Craig M., Linnet Taylor, and Jim Thatcher. 2016. “Critical Data Studies: A Dialog on Data and Space.” Big Data & Society 3 (1): 205395171664834. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716648346.

- Digital.AI. 2020. The 14th Annual State of Agile Report, 14. Annual State of Agile.

- Eden, Grace, Marina Jirotka, and Bernd Carsten Stahl. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation: Critical Reflection Into the Potential Social Consequences of ICT.” In IEEE 7th International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (RCIS), 1–12. Paris, France: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/RCIS.2013.6577706.

- Fabijan, Aleksander, Pavel Dmitriev, Helena Holmstrom Olsson, and Jan Bosch. 2018. “Online Controlled Experimentation at Scale: An Empirical Survey on the Current State of A/B Testing.” In 2018 44th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA), 68–72. Prague: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SEAA.2018.00021.

- Feitelson, Dror G., Eitan Frachtenberg, and Kent L. Beck. 2013. “Development and Deployment at Facebook.” IEEE Internet Computing 17 (4): 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2013.25.

- Felt, Ulrike, and Brian Wynne. 2007. Taking European Knowledge Society Seriously. EUR 22700. Community Research, European Commission.

- Fisher, Erik, Roop L. Mahajan, and Carl Mitcham. 2006. “Midstream Modulation of Technology: Governance from Within.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 26 (6): 485–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467606295402.

- Forsgren, Nicole. 2018. “DevOps Delivers.” Communications of the ACM 61 (4): 32–33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3174799.

- Forsgren, Nicole, and Jez Humble. 2016. “The Role of Continuous Delivery in IT and Organizational Performance.” In The Proceedings of the Western Decision Sciences Institute (WDSI), 1–15. Las Vegas, NV. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2681909.

- Fowler, Martin, and Jim Highsmith. 2001. “The Agile Manifesto.” Software Development 9 (8): 28–35.

- Fraaije, Aafke, and Steven M. Flipse. 2020. “Synthesizing an Implementation Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2019.1676685.

- Genus, Audley, and Andy Stirling. 2018. “Collingridge and the Dilemma of Control: Towards Responsible and Accountable Innovation.” Research Policy 47 (1): 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.09.012.

- Google Inc. 2000. “Google Launches Self-Service Advertising Program.” News from Google (blog), October 23, 2000. https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2009/12/personalized-search-for-everyone.html.

- Google Inc. 2015. “Our Story in Detail.” Google About (blog). https://web.archive.org/web/20150623193037/https://www.google.com/about/company/history/.

- Govind, Nirmal. 2017. “A/B Testing and Beyond: Improving the Netflix Streaming Experience with Experimentation and Data Science.” The Netflix Tech Blog (blog), June 13, 2017. https://netflixtechblog.com/a-b-testing-and-beyond-improving-the-netflix-streaming-experience-with-experimentation-and-data-5b0ae9295bdf.

- Grinbaum, Alexei, and Christopher Groves. 2013. “What Is “Responsible” About Responsible Innovation? Understanding the Ethical Issues.” In Responsible Innovation, edited by Richard Owen, John Bessant, and Maggy Heintz, 119–142. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118551424.ch7.

- Gürses, Seda, Carmela Troncoso, and Claudia Diaz. 2011. Engineering Privacy by Design. Computers, Privacy & Data Protection.

- Guston, David H., and Daniel Sarewitz. 2002. “Real-Time Technology Assessment.” Technology in Society 24 (1-2): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-791X(01)00047-1.

- Jirotka, Marina, Barbara Grimpe, Bernd Carsten Stahl, Grace Eden, and Mark Hartswood. 2017. “Responsible Research and Innovation in the Digital Age.” Communications of the ACM 60 (5): 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1145/3064940.

- Joly, Pierre-Benoit. 2015. “Governing Emerging Technologies – The Need to Think out of the (Black) Box.” In Making Knowledge and Making Power in the Biosciences and Beyond, edited by S. Hilgartner, S. Miller, and R. P. Hagendijk, 1–25. London: Routledge.

- Kamvar, Sep. 2005. “Search Gets Personal.” Google Official Blog (blog), June 28, 2005. https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2005/06/search-gets-personal.html.

- Kim, Sung Hyun, Si Young Jang, and Kyung Hoon Yang. 2017. “Analysis of the Determinants of Software-as-a-Service Adoption in Small Businesses: Risks, Benefits, and Organizational and Environmental Factors.” Journal of Small Business Management 55 (2): 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12304.

- Kupper, Frank, Pim Klaassen, Michelle Rijnen, Sara Vermeulen, and Jacqueline Broerse. 2015. “Report on the Quality Criteria of Good Practices Standards in RRI.” D1.3. RRI Tools Fostering Responsible Research and Innovation. Athena Institute, VU University Amsterdam.

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public.” In Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by Bruno Latour, and Peter Weibel, 14–43. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Liou, Kevin, Wenjing Zheng, and Sathya Anand. 2022. “Privacy-Preserving Methods for Repeated Measures Designs.” In Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2022, edited by Frédérique Laforest, Raphaël Troncy, Lionel Médini, and Ivan Herman, 105–109. Lyon, France: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487553.3524216.

- McGuigan, Lee, and Helen Nissenbaum. 2021. “On Google’s Sandbox/FLoC Proposal: Comments Submitted to UK-CMA.” DLI @ Cornell Tech (blog), September 12, 2021. https://www.dli.tech.cornell.edu/post/comments-on-proposed-privacy-sandbox-commitments-regarding-user-welfare-case-reference-50972.

- Mertens, Mayli. 2018. “Liminal Innovation Practices: Questioning Three Common Assumptions in Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (3): 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2018.1495031.

- Nayak, Pandu. 2019. “Understanding Searches Better Than Ever Before.” The Keyword (blog), October 25, 2019. https://blog.google/products/search/search-language-understanding-bert/.

- Nissenbaum, Helen. 2009. Privacy in Context: Technology, Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804772891.

- Nkonde, Mutale. 2019. “Automated Anti-blackness: Facial Recognition in Brooklyn, New York.” Harvard Kennedy School Journal of African American Policy 20:30–36.

- Nordmann, Alfred. 2014. “Responsible Innovation, the Art and Craft of Anticipation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2014.882064.

- Orlikowski, Wanda J., and Susan V. Scott. 2021. “Liminal Innovation in Practice: Understanding the Reconfiguration of Digital Work in Crisis.” Information and Organization 31 (1): 100336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2021.100336.

- Owen, Richard, and Mario Pansera. 2019. “Responsible Innovation and Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Handbook on Science and Public Policy, edited by Dagmar Simon, Stefan Kuhlmann, Julia Stamm, and Weert Canzler, 26–48. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715946.00010.

- Owen, Richard, Jack Stilgoe, Phil Macnaghten, Mike Gorman, Erik Fisher, and Dave Guston. 2013. “A Framework for Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation, edited by Richard Owen, John Bessant, and Maggy Heintz, 27–50. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118551424.ch2.

- Owen, Richard, René von Schomberg, and Phil Macnaghten. 2021. “An Unfinished Journey? Reflections on a Decade of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (2): 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.1948789.

- Pariser, Eli. 2011. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. New York: Penguin Press.

- Pelley, Scott. 2021. “Whistleblower: Facebook Is Misleading the Public on Progress Against Hate Speech, Violence, Misinformation.” CBS News, October 4, 2021. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebook-whistleblower-frances-haugen-misinformation-public-60-minutes-2021-10-03/.

- Product Peas. n.d. “Case Study 3 - Zach Schendel, Director of UX Research at Netflix.” Medium (blog). https://productpeas.medium.com/case-study-3-zach-schendel-director-of-ux-research-at-netflix-a2d169128e6c.

- Puppet. 2021. State of DevOps Report 2021.

- Raymond, Eric. 1999. “The Cathedral and the Bazaar.” Knowledge, Technology & Policy 12 (3): 23–49.

- Regan, Áine. 2021. “Exploring the Readiness of Publicly Funded Researchers to Practice Responsible Research and Innovation in Digital Agriculture.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (1): 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.1904755.

- Rip, Arie, and Johan Schot. 2002. “Identifying Loci for Influencing the Dynamics of Technological Development.” In Shaping Technology. Guiding Policy; Concepts, Spaces and Tools, edited by K. Sørensen, and R. Williams, 49–70. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/5585145/K_372___.PDF.

- Robinson, Douglas K.R. 2009. “Co-Evolutionary Scenarios: An Application to Prospecting Futures of the Responsible Development of Nanotechnology.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 76 (9): 1222–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2009.07.015.

- Rubinstein, Ira S., and Nathanial Good. 2013. “Privacy by Design: A Counterfactual Analysis of Google and Facebook Privacy Incidents.” Berkeley Technology Law Journal 28 (2): 1333–1414.

- Schendel, Zach. 2018. InVision Design Talks - Insight into Innovation on the Netflix TV Platform. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ld7RfeZNtXs.

- Search Engine Land. n.d. Google Algorithm Updates. https://searchengineland.com/library/google/google-algorithm-updates.

- Sellen, Abigail, Yvonne Rogers, Richard Harper, and Tom Rodden. 2009. “Reflecting Human Values in the Digital Age.” Communications of the ACM 52 (3): 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1145/1467247.1467265.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation: The Role of Privacy in an Emerging Framework.” Science and Public Policy 40 (6): 708–716. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/sct067.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten, Grace Eden, Marina Jirotka, and Mark Coeckelbergh. 2014a. ‘From Computer Ethics to Responsible Research and Innovation in ICT’. Information & Management 51 (6): 810–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.01.001.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten, Neil McBride, Kutoma Wakunuma, and Catherine Flick. 2014b. “The Empathic Care Robot: A Prototype of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 84 (May): 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.08.001.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten, Job Timmermans, and Brent Daniel Mittelstadt. 2016. “The Ethics of Computing: A Survey of the Computing-Oriented Literature.” ACM Computing Surveys 48 (4): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1145/2871196.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten, and David Wright. 2018. “Ethics and Privacy in AI and Big Data: Implementing Responsible Research and Innovation.” IEEE Security & Privacy 16 (3): 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2018.2701164.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten, and Emad Yaghmaei. 2016. “The Role of Privacy in the Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation in ICT for Health, Demographic Change and Ageing.” In Privacy and Identity Management. Facing up to Next Steps, edited by Anja Lehmann, Diane Whitehouse, Simone Fischer-Hübner, Lothar Fritsch, and Charles Raab, 92–104. Vol. 498. Cham: Springer International Publishing. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55783-0_8.

- Stilgoe, Jack, Richard Owen, and Phil Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Turner, M., D. Budgen, and P. Brereton. 2003. “Turning Software Into a Service.” Computer 36 (10): 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2003.1236470.

- van de Poel, Ibo. 2017. “Society as a Laboratory to Experiment with New Technologies.” In Embedding New Technologies Into Society, edited by Diana M. Bowman, Elen Stokes, and Arie Rip, 61–87. 1st ed. Singapore: Jenny Stanford Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315379593-4.

- van den Hoven, Jeroen. 2013. “Value Sensitive Design and Responsible Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation, edited by Richard Owen, John Bessant, and Maggy Heintz, 75–83. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118551424.ch4.

- Vigderman, Aliza, and Gabe Turner. 2022. “The Data Big Tech Companies Have On You.” Security.Org (blog), July 22, 2022. https://www.security.org/resources/data-tech-companies-have/.

- The Wall Street Journal. 2021. Teen Girls Body Image and Social Comparison on Instagram - An Exploratory Study in the U.S. https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/documents/teen-girls-body-image-and-social-comparison-on-instagram.pdf.

- Wong, Richmond Y., and Deirdre K. Mulligan. 2019. “Bringing Design to the Privacy Table: Broadening “Design” in “Privacy by Design” Through the Lens of HCI.” In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–17. Glasgow, Scotland,UK: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300492.

- Xu, Y., Nanju Chen, Addrian Fernandez, Omar Sinno, and Anmol Bhasin. 2015. “From Infrastructure to Culture: A/B Testing Challenges in Large Scale Social Networks.” In: Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2227–2236. https://doi.org/10.1145/2783258.2788602.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: PublicAffairs.