Abstract

Despite the increasing emphasis on negative symptoms and social cognition impairments in patients with schizophrenia, the nature of the relationship between subdomains of negative symptoms and social cognition remain unclear. Therefore, the aim of the study was to examine the relationship between subdomains of negative symptoms, i.e. diminished expression (DE) and avolition-apathy (AA), and emotion recognition, theory of mind and neurocognition in clinically stable schizophrenia. Sixty-two (62) clinically stable patients with schizophrenia were included in this study. Emotion recognition and theory of mind were assessed with the Faces test and Reading the Mind in the Eyes test (the Eyes test). Neurocognition was measured with the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III. Negative symptoms were assessed with the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Statistically significant correlations were achieved between DE and AA, and emotion recognition (DE—emotion recognition, p < 0.001 and AA—emotion recognition p < 0.001) and neurocognition (DE—neurocognition, p < 0.001 and AA—neurocognition, p = 0.002). However, only DE was associated with theory of mind (p = 0.034). Using structural equation modelling (SEM), a three-factor model showed that the relationship between negative symptoms and social cognition was stronger than negative symptoms and neurocognition (correlation −0.62 vs −0.46). Findings of this study indicate that negative symptoms are more closely correlated to social cognition than neurocognition. The DE subdomain appears to be more strongly related to emotion recognition and theory of mind performance versus AA. The current results provide more insights into the nature of the relationship between negative symptoms, social cognition, and neurocognition in schizophrenia.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Schizophrenia is characterized by relapsing episodes of hallucinations, delusions, disordered thinking and disorganized motor behavior which can be grouped as positive symptoms. However, people with schizophrenia also have other symptoms, i.e., negative symptoms, neurocognition, and social cognition deficits. Despite the increasing importance of negative symptoms and social cognition impairment in patients with schizophrenia, the nature of the relationship between subdomains of negative symptoms and social cognition remain unclear. This manuscript explores the relationship between subdomains of negative symptoms, i.e. diminished expression (DE) and avolition-apathy (AA), and emotion recognition, theory of mind and neurocognition in clinically stable schizophrenia. In our study, we found that negative symptoms were more closely related to social cognition than neurocognition. Moreover, the DE subdomain of negative symptoms appears to be more strongly related to emotion recognition and theory of mind performance versus AA. These results provide greater insights into the nature of the relationship between negative symptoms, social cognition, and neurocognition in schizophrenia.

1. Introduction

1.1. Negative symptoms

Negative symptoms are some of the most important diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. Although positive symptoms typically respond to pharmacological treatments, negative symptoms tend to persist in the long term and are unresponsive to antipsychotics. Previous studies show negative symptoms to have wide multidimensionality, which helps explain the variety in symptoms and outcomes of the disorder. According to the US National Institute of Mental Health and the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (NIMH-MATRIC), the subdomains for negative symptoms include blunted affect, alogia, asociality, anhedonia, and avolition (Kirkpatrick et al., Citation2006). A number of recent factor analyses and network analyses suggest that a unidimensional model of negative symptoms does not adequately capture the complexity of negative symptoms. The 5-dimensional model best represents the negative symptom structure (Strauss, Ahmed et al., Citation2019; Strauss, Esfahlani et al., Citation2019; Strauss et al., Citation2018). Although there are only limited data on the pathophysiology of negative symptoms, the available evidence supports that pathophysiology could be specific to each of the five dimensions of negative symptoms (Guessoum et al., Citation2020; Strauss, Esfahlani et al., Citation2019). Besides a five-factor model, prior exploratory factor analysis studies demonstrate that negative symptoms can be grouped into two constructs termed diminished expression (DE) and avolition-apathy (AA). The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) structured its description of negative symptoms using these two broad DE and AA dimensions. Using this two-factor model, blunted affect and alogia are placed under DE, while asociality, anhedonia, and avolition are in AA (Lyne et al., Citation2013).

1.2. Social cognition

Social cognition is a relatively new concept and is described as the mental process that underlies social interactions. Among the many areas of social cognition, emotion recognition and theory of mind are the most extensively studied domains in patients with schizophrenia (Green et al., Citation2008). Emotion perception refers to the individual’s ability to identify other people’s emotions, while theory of mind refers to their ability to attribute mental states and feelings to other people. Studies have typically demonstrated that people with schizophrenia perform worse than healthy controls in social cognition performances (Charernboon & Patumanond, Citation2017; Savla et al., Citation2013). Moreover, it is well established that social cognition deficits are related to poor functional outcomes in schizophrenia patients (Fett et al., Citation2011).

Negative symptoms have consistently been shown to be correlated with social cognition and neurocognition in schizophrenia, but in the past, negative symptoms were usually analysed as a unidimensional concept (Browne et al., Citation2016; Charernboon & Patumanond, Citation2017; Healey et al., Citation2016). Few studies have examined the association between the subdomains of the negative symptoms (DE and AA) and emotion recognition, theory of mind, and neurocognition (Ditlevsen et al., Citation2019).

The aims of this study were to (1) explore the correlation between subdomains of negative symptoms and theory of mind, emotion recognition, and neurocognition; (2) examine which subdomain of negative symptoms (DE or AA) is most closely related to affective theory of mind and emotion recognition; and (3) assess whether these overall negative symptoms are more related to social cognition or neurocognition.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 62 patients with schizophrenia were recruited from a mental health outpatient department at Thammasat University Hospital, Thailand. The participants had been diagnosed with schizophrenia by psychiatrists according to the DSM-5 criteria. All the participants were between 20 and 60 years of age and in clinically stable phases, as defined by no changes in pharmacological treatment or psychotic symptoms for the previous 3 months. Furthermore, they were free of any other major neurological disease or psychiatric disorders (i.e. major depressive disorder, intellectual disabilities, or substance dependence excluding smoking). The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (No. MTU-EC-PS-0-191/60).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Negative symptoms

Negative symptoms were assessed using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen, Citation1984a; Charernboon, Citation2019b) and classified using two methods: (1) five subdomains: blunted affect, alogia, asociality, anhedonia, and avolition and (2) two constructs: diminished expression (DE; blunted affect plus alogia) and avolition-apathy (AA; asociality plus anhedonia plus avolition). The attention subdomain of SANS was excluded since it is currently classified as neurocognition and overlaps with the neurocognition test. An inappropriate affect item was also removed because it is currently regarded as an aspect of disorganisation in positive symptoms (Marder & Galderisi, Citation2017).

2.2.2. Positive symptoms

The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) were administered to the patients to assess the severity of their positive symptoms. The total SAPS scores were between 0 and 150, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity (Andreasen, Citation1984b; Charernboon, Citation2019a).

2.2.3. Theory of mind

The patients were tested with the Reading the Mind in the Eyes (the Eyes test), an affective theory of mind task consisting of a series of photographs of the eye regions (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001; Charernboon & Lerthattasilp, Citation2017). The task involved selecting the word which best describes the feeling or mental state of the individual in the photograph. The scores ranged from 0 to 36 points, with a higher score implying a better theory of mind ability.

2.2.4. Emotion recognition

The Faces test was used to examine emotion recognition. The Faces test consists of 20 pictures of human faces showing a variety of emotions. The scores ranged from 0 to 20, with a higher score indicating better emotion recognition performance (Charernboon, Citation2017).

2.2.5. Neurocognition

Neurocognition was measured using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE)(Charernboon et al., Citation2016; Hsieh et al., Citation2013), a 100-point measurement in five neurocognition domains: attention/orientation; verbal fluency; language; visuospatial ability; and memory. Higher scores indicate better neurocognitive function. It has been previously demonstrated that ACE is sensitive and can detect cognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia (Charernboon & Chompookard, Citation2019).

2.3. Procedure

Demographic and clinical data were retrieved from medical records. One psychiatrist interviewed the patients and rated the SANS. After that, the ACE, Faces, and Eyes tests were administered by an independent research assistant.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlation was used to analyse the statistical relationship between negative symptoms and their subdomains as well as theory of mind, emotion recognition, and neurocognition. Additionally, the researchers performed a test of equality of two correlation coefficients to test whether the correlation coefficient results of the two-factor model of negative symptoms and social cognition compared to the five-factor model.

Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to investigate whether the DE or AA subdomains are more related to emotion recognition, theory of mind, and neurocognition. In these analyses, the model used the Faces test, the Eyes test, and the total ACE score as dependent variables, while DE and AA scores were used as independent variables.

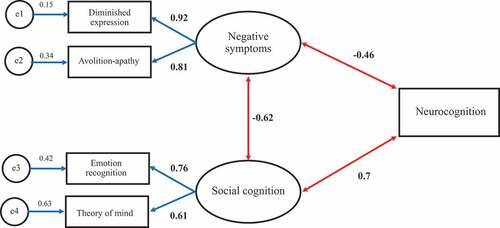

For the final objective, the researchers aimed to examine the overall relationship between negative symptoms, neurocognition, and social cognition while seeking to determine whether negative symptoms are more closely related to social cognition or neurocognition. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was employed. A three-factor model was used which represented social cognition, neurocognition, and negative symptoms in order to compare the path coefficient between these three factors. Negative symptoms and social cognition were created as latent variables. DE and AA represented measured variables of negative symptoms, whereas the theory of mind and emotion recognition represented measured variables of social cognition. Neurocognition was constructed as a single-measured variable to reduce the complexity of the models and minimise the number of parameters.

Regarding the sample size estimation, at least 10 participants per predictor are generally required for a multivariable linear regression model (Babyak, Citation2004). The present study included two independent variables (DE and AA), so a minimum sample size of 20 participants was required for the study. All data were analyzed with STATA v14.0: p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

Table summarises the demographic and clinical data. The patients had a mean age of 36.6 ± 12.3 years. The average level of education was 13.1 ± 3.3 years. The patients had a mean duration of illness of 7.9 ± 9.0 years. The total SAPS scores were very low (4.2 points), indicating that most of the patients had no or mild positive symptoms.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical data of schizophrenia patients

The correlations between the subdomains of negative symptoms and emotion recognition and theory of mind performance, as well as the patients’ neurocognition are presented in Table . Statistically significant correlations were achieved between DE and AA, and between emotion recognition and neurocognition. Only DE was associated with the theory of mind performance while AA was not associated with it. Likewise, all five subdomains of negative symptoms (blunted affect, alogia, avolition, anhedonia, and asociality) were correlated with emotion recognition and neurocognition. Only alogia was associated with the theory of mind.

Table 2. Correlation between subdomains of negative symptoms and social cognition

Comparing the correlation coefficients between the 2-dimensional model of negative symptoms and social cognition vs 5-dimensional model, there were no statistically significant differences in all comparisons: blunted affect-emotion recognition vs DE-emotion recognition (p = 0.57), blunted affect-theory of mind vs DE-theory of mind (p = 0.394), alogia-emotion recognition vs DE-emotion recognition (p = 0.905), Alogia-theory of mind vs DE-theory of mind (p = 0.919), avolition-emotion recognition vs AA-emotion recognition (p = 0.743), avolition-theory of mind vs AA-theory of mind (p = 0.872), anhedonia-emotion recognition vs AA-emotion recognition (p = 0.875), anhedonia-theory of mind vs AA-theory of mind (p = 0.883), asociality-theory of mind vs AA-theory of mind (p = 0.579), and asociality-theory of mind vs AA-theory of mind (p = 0.786).

Multivariable linear regressions were performed with emotion recognition, the theory of mind, and neurocognition as dependent variables, and DE and AA subdomains as independent variables (Table ). DE had a significant effect on the performance of emotion recognition (p = 0.045), but not for theory of mind and neurocognition. Patients with high DE symptoms generally demonstrate lower performance in social cognition. Meanwhile, AA showed no statistical significance in the emotion recognition, theory of mind, and neurocognition tasks. Looking at the adjusted R-squared of the three regression models, DE and AA could explain 22.7% of the variance in emotion recognition performance and 15.9% in neurocognition. It should be noted that DE and AA appear to only account for a small proportion of the variance in theory of mind performance (4.6%).

Table 3. Multivariable regression analysis of social cognition and neurocognition using diminished expression (DE) and avolition-apathy (AA) as predictors

Three-factor SEM was used to explore the overall associations between negative symptoms, social cognition, and neurocognition (Figure ). All the indicators had p-values of <0.05. The model provided an acceptable fit with a X2 = 5.87 and p = 0.12. This model demonstrated that the correlation between negative symptoms and social cognition was higher than negative symptoms and neurocognition (−0.62 vs −0.46). The strongest relationship was between social cognition and neurocognition, with a standardised coefficient of 0.7. The factor loadings of DE and AA on negative symptoms and emotion recognition, and theory of mind on social cognition were all at least 0.6.

4. Discussion

Many previous studies have shown that social cognition deficits are related to negative symptoms (Fett et al., Citation2011; Savla et al., Citation2013), but the present study attempted to explore this in detail. The present study finds that the DE subdomain of negative symptoms was far more correlated to emotion recognition and theory of mind than the AA subdomain, in which more DE symptoms predicted lower performance on both social cognition tests.

The results conform with prior studies that report DE symptoms to be better predictors of emotion recognition and theory of mind performance versus AA (Ditlevsen et al., Citation2019; Gur et al., Citation2006). Meanwhile, AA appears to have no significant association with the theory of mind ability (Andrzejewska et al., Citation2017). The findings of the present study appear to support previous ideas suggesting that DE and AA as independent constructs should be assessed separately in negative symptom research (Lyne et al., Citation2013; Marder & Galderisi, Citation2017). Likewise, this study finds that emotion recognition and theory of mind are also independent constructs showing different correlations with DE and AA.

One hypothesis regarding the association between emotion recognition and DE symptoms is that there is abnormal amygdala activation as well as functional abnormalities within the limbic system in people with schizophrenia. This may result in errors of identification and discrimination of emotions, since blunted affect is an adaptive response and consequence of these abnormalities (Azorin et al., Citation2014; Gur et al., Citation2007).

The results of using the 5-dimensional model to consider negative symptoms demonstrate that all five domains had correlations with emotion recognition, but only alogia was correlated with the theory of mind task. Andrzejewska et al. (Citation2017) assessed the relationship between all negative symptoms and deficits in emotion recognition and theory of mind using the Facial Emotion Identification Test and the Eyes test. In the study, Andrzejewsk et al. also found a similar pattern in which all the domains of negative symptoms were associated with emotion recognition deficits, but only a few domains were correlated with the theory of mind task. These results suggest that there are specific social cognition impairments linked to one or more negative symptoms. Hence, it may be possible that distinct social cognitive deficits lead to specific negative symptoms (Pelletier-Baldelli & Holt, Citation2020).

The relationship between asociality and social cognition has been addressed more recently. As social cognition refers to the mental process underlying social interaction, it is believed to be somehow associated with asociality. The results of the present study indicate that there is an association between asociality and emotion recognition, but not with theory of mind. However, previous studies have been mixed, with some noting a significant association and others reporting no association (Marder & Galderisi, Citation2017). The nature of the relationship between asociality and emotion recognition is likely to be complicated and may be reciprocal, that is, low motivation to participate in social interaction potentially results in poor emotion recognition ability. Meanwhile, poor emotion recognition performance may result in social problems and a failure to experience reward from social activities.

When negative symptoms, social cognition, and neurocognition were included in the same model using SEM, the correlation between negative symptoms and social cognition was stronger than the association between negative symptoms and neurocognition. Hence, negative symptoms appear to be more closely related to social cognition than neurocognition. The results are congruent with previous studies suggesting that the correlation between negative symptoms and neurocognition is usually moderate with a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.3 (Harvey et al., Citation2006).

In the last decade, schizophrenia research has generally conceptualized social cognition as a separate construct from neurocognition. The present study supports the value of separating social cognition domains from neurocognition. Although they are closely related, social cognition displays different levels of relationships to negative symptoms versus neurocognition. Moreover, each social cognition task appears to also demonstrate independent constructs.

For clinical implication, the study underscores the importance to assess negative symptoms and social cognition in patients with schizophrenia in clinical practice. Moreover, the results suggest that both negative symptoms and social cognition should be considered as multi-dimensional models instead of a single unitary construct.

4.1. Limitations

Since this study only included two social cognitive domains, other domains such as social knowledge, social perception, and attributional biases have yet to be further examined. The present study was cross-sectional and so may not represent the longitudinal relationships between the three symptom groups. Moreover, the study included stable schizophrenia patients who all received antipsychotic drugs. Therefore, some negative symptoms may be the result of medications (secondary negative symptoms). In the SEM model, it was not possible to include negative symptoms using the 5-dimensional model since the sample size was too small. Bentler and Chou suggest that a ratio of 5 cases per indicator variable is sufficient for SEM analysis (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987). Subsequently, a 5-dimensional model (plus two social cognition and one neurocognition variables) would require a minimum sample size of 80 participants. It should be noted that this study is an exploratory analysis that examined both the 2- and 5-dimensional models of negative symptoms with two social cognition tasks. This led to multiple outcomes, meaning that an increase in statistically significant by chance could have occurred. Additionally, our participants were clinically stable schizophrenia patients recruited from a mental health outpatient department, it might not be generalizable to patients with more severe psychotic symptoms. Lastly, some factors, such as age, level of education and medication use, might influence on the cognitive test performance. However, we did not adjust these variables into the models since it will make the models too complex with too many parameters.

More studies are required to further understanding of the interrelations between the subdomains of negative symptoms and social cognition. Since the DE subdomain and emotional recognition are closely related, from a therapeutic perspective it would be beneficial to explore whether providing patients with emotion recognition training would improve their DE symptoms.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thammanard Charernboon

Dr Thammanard Charernboon is a board-certified psychiatrist in Psychiatry and Geriatric Psychiatry and obtained an MSc in Advanced Care in Dementia from King’s College, London, and a PhD in Clinical Epidemiology from Thammasat University. Currently, he is an associate professor at the Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University. His research areas include schizophrenia, dementia, neurocognition, and social cognition.

References

- Andreasen, N. C. (1984a). Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS). University of Iowa.

- Andreasen, N. C. (1984b). Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). University of Iowa.

- Andrzejewska, M., Wójciak, P., Domowicz, K., & Rybakowski, J. (2017). Emotion recognition and theory of mind in chronic schizophrenia: Association with negative symptoms. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 4(4), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/79878

- Azorin, J. M., Belzeaux, R., & Adida, M. (2014). Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Where we have been and where we are heading. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 20(9), 801–808. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12292

- Babyak, M. A. (2004). What you see may not be what you get: A brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(3), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “reading the mind in the eyes” test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00715

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Browne, J., Penn, D. L., Raykov, T., Pinkham, A. E., Kelsven, S., Buck, B., & Harvey, P. D. (2016). Social cognition in schizophrenia: Factor structure of emotion processing and theory of mind. Psychiatry Research, 242, 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.05.034

- Charernboon, T. (2017). Validity and reliability of the Thai version of the faces test. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, 100(6), 42–45. http://www.jmatonline.com/index.php/jmat/article/view/8396#

- Charernboon, T. (2019a). Preliminary study of the Thai-version of the scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS-Thai): Content validity, known-group validity, and internal consistency reliability. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 46(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-60830000000183

- Charernboon, T. (2019b). Preliminary study of the Thai version of the scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS-Thai). Global Journal of Health Science, 11(6), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v11n6p19

- Charernboon, T., & Chompookard, P. (2019). Detecting cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia with the Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.01.006

- Charernboon, T., Jaisin, K., & Lerthattasilp, T. (2016). The Thai version of the Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination III. Psychiatry Investigation, 13(5), 571–573. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2016.13.5.571

- Charernboon, T., & Lerthattasilp, T. (2017). The reading the mind in the eyes test: Validity and reliability of the Thai version. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 30(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0000000000000130

- Charernboon, T., & Patumanond, J. (2017). Social cognition in schizophrenia. Mental Illness, 9(1), 7054. https://doi.org/10.1108/mi.2017.7054

- Ditlevsen, J. V., Simonsen, A., & Bliksted, V. F. (2019). Predicting mentalizing deficits in first-episode schizophrenia from different subdomains of negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Research, 215, 439–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.036

- Fett, A. K., Viechtbauer, W., Dominguez, M. D., Penn, D. L., van Os, J., & Krabbendam, L. (2011). The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001

- Green, M. F., Penn, D. L., Bentall, R., Carpenter, W. T., Gaebel, W., Gur, R. C., Kring, A. M., Park, S., Silverstein, S. M., & Heinssen, R. (2008). Social cognition in schizophrenia: An NIMH workshop on definitions, assessment, and research opportunities. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(6), 1211–1220. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm145

- Guessoum, S. B., Le Strat, Y., Dubertret, C., & Mallet, J. (2020). A transnosographic approach of negative symptoms pathophysiology in schizophrenia and depressive disorders. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 99, 109862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109862

- Gur, R. E., Kohler, C. G., Ragland, J. D., Siegel, S. J., Lesko, K., Bilker, W. B., & Gur, R. C. (2006). Flat affect in schizophrenia: Relation to emotion processing and neurocognitive measures. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(2), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj041

- Gur, R. E., Loughead, J., Kohler, C. G., Elliott, M. A., Lesko, K., Ruparel, K., Wolf, D. H., Bilker, W. B., & Gur, R. C. (2007). Limbic activation associated with misidentification of fearful faces and flat affect in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(12), 1356–1366. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1356

- Harvey, P. D., Koren, D., Reichenberg, A., & Bowie, C. R. (2006). Negative symptoms and cognitive deficits: What is the nature of their relationship? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(2), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj011

- Healey, K. M., Bartholomeusz, C. F., & Penn, D. L. (2016). Deficits in social cognition in first episode psychosis: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 50, 108–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.001

- Hsieh, S., Schubert, S., Hoon, C., Mioshi, E., & Hodges, J. R. (2013). Validation of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 36(3–4), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351671

- Kirkpatrick, B., Fenton, W. S., Carpenter, W. T., Jr., & Marder, S. R. (2006). The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(2), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj053

- Lyne, J., Renwick, L., Grant, T., Kinsella, A., McCarthy, P., Malone, K., Turner, N., O’Callaghan, E., & Clarke, M. (2013). Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms structure in first episode psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1191–1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.09.008

- Marder, S. R., & Galderisi, S. (2017). The current conceptualization of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20385

- Pelletier-Baldelli, A., & Holt, D. J. (2020). Are negative symptoms merely the “real world” consequences of deficits in social cognition?. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(2), 236–241 doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz095

- Savla, G. N., Vella, L., Armstrong, C. C., Penn, D. L., & Twamley, E. W. (2013). Deficits in domains of social cognition in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(5), 979–992. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs080

- Strauss, G. P., Ahmed, A. O., Young, J. W., & Kirkpatrick, B. (2019). Reconsidering the latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A review of evidence supporting the 5 consensus domains. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 45(4), 725–729. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby169

- Strauss, G. P., Esfahlani, F. Z., Galderisi, S., Mucci, A., Rossi, A., Bucci, P., Rocca, P., Maj, M., Kirkpatrick, B., Ruiz, I., & Sayama, H. (2019). Network analysis reveals the latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 45(5), 1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby133

- Strauss, G. P., Nunez, A., Ahmed, A. O., Barchard, K. A., Granholm, E., Kirkpatrick, B., Gold, J. M., & Allen, D. N. (2018). The latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(12), 1271–1279. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2475