Abstract

Scientific literature suggests more women to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) yet more men to commit suicide. Thus, distinct gender-specific symptoms may exist allowing prototypical male depression to evade social and medical detection until it is too late. This study aimed at characterizing gender differences based on self-rating questionnaires in male and female patients with acute suicidal ideations (n = 28; 12 female patients) committed to a local district hospital in Bavaria, Germany from 2021 to 2023. While these patients reported significantly augmented symptoms in the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS), the Gender-Specific Depression Screening (GSDS), the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI-II), and the Impulsive Behavior Short Scale-8 (I-8) compared to healthy controls (n = 30; 14 female controls), gender-based differences within the group remained surprisingly scarce. Surprisingly, the GSDS failed to differentiate gender-specific symptoms (ie male-specific depressive symptoms). Suicidal women, however, reported a heightened anger trait and outward directed anger expression (STAXI-II), as well as prominent sensation seeking and urgency (I-8) than suicidal men; symptoms that are viewed as typically male. Conversely, suicidal men primarily expressed inwardly directed anger (ie self-hate; STAXI-II). There is no evidence for self-reported, presumably gender-specific symptomatology in the investigated suicidal mixed-gender patient population.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Before the ominous COVID-19 pandemic shook the world, exacerbating poor mental health, mental disorders were already the leading contributor to the global disease burden (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, Citation2021). Among these, MDD has always been and currently remains a significant contributor, with an additional estimated 53.2 million pandemic-related cases worldwide (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, Citation2021). In its most severe consequence, depression may lead to suicide, with a German statistic reporting one completed suicide per hour every single day of the year (Schelhase, Citation2022). Remarkably, however, the fact is that although more women are diagnosed with depression, suicide rates are three times higher among men (Branney & White, Citation2008; Oliffe et al., Citation2016; Oliffe et al., Citation2019), with the COVID-19 pandemic actually not changing overall self-harm and suicide statistics in both genders (John et al., Citation2020; Pirkis et al., Citation2022). Research suggests that social stigma, as well as clinically not assessed externalizing symptoms such as anger, substance abuse, risk-taking, impulsivity, or over-involvement in work, may be contributing factors (Oliffe et al., Citation2016; Zülke et al., Citation2018). Others discuss a variety of cognitive, emotional, temperament, and personality trait correlations (Giner et al., Citation2016). In light of these considerations, gender-specific assessment tools were initially developed. However, a critical review from 2018 revealed that out of 122 assessed studies, only eight used such tools, with just four comparing them between both genders (Zülke et al., Citation2018). Consequently, this study attempted to assess the presence of prototypic male-depressive symptoms with a novel gender-specific screening tool (Möller-Leimkühler & Mühleck, Citation2020), the GSDS, in a mixed-gender population with acute suicidal ideations. Furthermore, we intended to assess impulsivity and anger traits in a gender-comparative manner. In summary, we hypothesized that atypical depressive symptoms, in combination with pronounced anger and impulsiveness, would be predominantly found in the male suicidal population.

Methods and materials

Participants

From 2021 to 2023, a total of 30 patients with acute suicidal ideations aged 18 or older were recruited from the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy II, Ulm University, at the district hospital site of Günzburg, Bavaria, Germany. Recruitment occurred within the first 24 hours of hospital admission by two independent doctoral students. It is important to note, that the term ‘acute suicidal ideations’, which is used throughout the article, refers to patients with present thoughts about and intends to commit suicide. These ideations were perceived serious enough (comparable to an ICD-10 F32.2) by the patients themselves or their relatives to warrant hospitalization. Inclusion criteria for the test group were a diagnosis of any acute depressive disorder (ICD-10 coding: F32, F33, F34, F38, F39) as well as sufficient German language skills. Exclusion criteria consisted of any given diagnosis in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, impairment of intelligence, bipolar disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders (SUDs), cancer, chronic inflammatory diseases, epilepsy, diabetes, coronary heart diseases, adiposity, and pregnancy. Subsequently, 30 age- and gender-matched healthy controls were recruited via public notices, social media advertisements, or personal contacts following the same exclusion criteria. Unfortunately, two female participants from the suicidal group failed to return the questionnaires and hence were excluded from the analysis. For additional sociodemographic details, please see .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics for both groups.

Questionnaires

The Beck Suizidgedanken Skala (BSS; (Beck & Steer, Citation1993; Kliem & Brähler, Citation2016) consists of 19 items assessing various aspects of suicidal ideation (ie suicidal thoughts, previous suicide attempts, etc.) as well as the severity of suicidality within the last two weeks. The instrument comprises 19 groups of statements, each of which is rated on a 3-point scale from 0 to 2. The first five groups of statements are considered screening questions. Two of these five groups of statements are indicators of passive or active suicidal thoughts and are considered filter questions. If both groups of statements are rated as ‘0’ (no passive or active suicidal thoughts), the following 14 groups of statements are skipped and only the last two groups of statements are processed (previous suicide attempts; wish to die during the last suicide attempt). If one of the two filter questions is answered with at least the value 1, the following 14 statement groups are also answered. The maximum total score of the BSS is 38 points. The BSS has proven an excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency r = 0.89) and validity (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2); r = 0.36; (Löwe et al., Citation2005).

The Gender-Sensitive Depression Screening (GSDS) assesses self-reported, typical as well as atypical depressive symptoms, especially those thought to occur in men over a period of two weeks before hospital admission (Möller-Leimkühler & Mühleck, Citation2020). Its 26 items are divided into six subscales: depressive symptoms, stress perception, emotional control, aggressiveness, alcohol abuse, and risky behavior. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from never or rarely (= 0) to mostly or always (= 3). To evaluate the scores, we calculated the mean values of the subscales and the entire scale. The GSDS has proven good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of total scale, r = 0.88; Cronbach’s alpha of subscales, from r = 0.86 to r = 0.70) and satisfactory convergent validity with the short version of the General Depression Scale (ADS-K, Spearman’s Rho = 0.79; (Hautzinger & Bailer, Citation1993)).

The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI-II; German adaptation (Rohrmann et al., Citation2013)) consists of 51 Items and assesses situational as well as dispositional anger dimensions. The items are answered on a 4-point rating scale (1 = almost never, 4 = almost always). For each scale, the scale raw score is calculated from the sum of the associated item scores. Its retest reliability lies between 0.14 and 0.29 for situational anger dimensions and between 0.63 and 0.81 for trait-related scales. Furthermore, the STAXI-II is a questionnaire with good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.79 and 0.91). For its dispositional scales exist T-values from a representative German sample (972 women and 917 men; age 16–90). Of notice is, that in this study items were limited to the subscales Trait-anger, Anger expression outward, Anger expression inward, and Anger control.

The Kurzskala zur Messung von Impulsivität (I-8; Kovaleva et al., Citation2014) is a short, eight items long questionnaire assessing impulsivity in accordance with the impulsivity model from Whiteside and Lynam (Citation2001). Rating is based on a 5-point Likert scale (1= Doesn’t apply at all, 5 = Applies completely). The scores were averaged to determine the subscale and total scale value. Reference values exist based on gender, educational status, and age. Its internal reliability (Donalds Omega) is considered sufficient and ranges from 0.65 and 0.92. Retest-reliability is in a good range (r = 0.46–0.57).

Statistical analysis

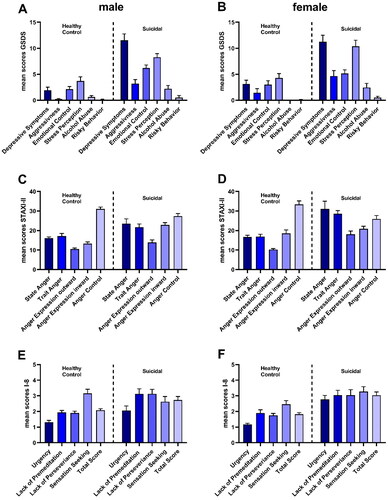

The analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, absolute and relative frequency, were initially generated. Group comparisons for continuous variables employed t-tests (for variables with a normal distribution) or a Mann-Whitney U-Test. For nominal variables, Chi-squared tests or a Fisher Freeman Halton test were utilized. The analyses of gender and group differences were tested using generalized linear models (GZLM) with a normal distribution and the identity linkage function. The Huber-White sandwich estimator was selected to approximate the covariance matrix. Scale scores from various questionnaires (BSS total scale sum score, GSDS subscales sum scores, STAXI-II subscales sum scores, I-8 subscales mean scores) were predicted based on the factors: group [healthy controls (0) versus suicidal patients (1)], gender [male (0) and female (1)], and the interaction group*gender. was generated using GraphPad Prism 9 (© GraphPad Software). In addition, the measurement invariance of the model was checked (see Supplementum 1)

Figure 1. Graphical demonstration of the questionnaire outcomes. (A) GSDS – male healthy controls vs. suicidal patients; (B) GSDS – female healthy controls vs. suicidal patients; (C) STAXI-II – male healthy controls vs. suicidal patients; (D) STAXI-II – female healthy controls vs. suicidal patients; (E) I-8 – male healthy controls vs. suicidal patients; (F) I-8 – female healthy controls vs. suicidal patients. Data is displayed by mean ± SEM.

Results

Regarding the sociodemographic characteristics (), no differences were found for age (t(56) = 0.230, p = 0.819, Cohen’s d = 0.13), body weight (t(56) = −1.927, p = 0.059, Cohen’s d = 0.13), and body height (t(56) = 1.563, p = .124, Cohen’s d = 0.24). However, cigarette consumption occurred significantly more frequently in the test group than in the control group (Chi2-Test = 7.472, p < .006, Cramer-V = 0.365). Furthermore, the control group reported higher levels of education (Exakter Test nach Fisher-Freeman-Halton = 25.104, p < .001, Cramer-V = 0.645).

Unsurprisingly, the BSS revealed significantly augmented suicidal ideation for both genders compared to the control group (men: b = 17.167, SE(b) = 3.8767, p < .001 and women: b = 17.136, SE(b) = 5.0654, p < .001).

Regarding the GSDS, generalized linear models were calculated based on the factors group and gender*group. On the group level, all subscales except risky behavior as well as he GSGDS total score (b = 23.773, SE(b) = 4.321, p < .001) were significantly increased (depressive symptoms (b = 9.596, SE(b) = 1.324, p < .001), aggressiveness (b = 2.950, SE(b) = 0.775, p < .001), emotional control (b = 4.075, SE(b) = 0.772, p < .001), stress perception (b = 4.579, SE(b) = 1.059, p < .001), and alcohol abuse (b = 1.589, SE(b) = 0.667, p = .019). Interestingly, gender*group interactions revealed no gender-specific behavioral patterns. For graphical demonstration, please see .

The STAXI-II questionnaire, however, exposed differences on both group and gender*group levels. The suicidal group exhibited a pronounced anger state (state anger: b = 7.408, SE(b) = 2.487, p = .003) but also showed distinct anger personality characteristics (trait anger: b = 4.608, SE(b) = 2.115, p = .029), as well as exaggerated outwardly expressed anger (b = 3.371, SE(b) = 1.336, p = .012) and inwards (b = 9.554, SE(b) = 1.434, p < .001). On the other hand, their ability to control anger was significantly attenuated (b = −3.663, SE(b) = 1.613, p = 0.023). Remarkably, the personality trait anger was significantly more pronounced in women than in men (b = 7.069, SE(b) = 2.854, p = .013). Furthermore, women reported increased anger expression towards their surroundings (b = 4.427, SE(b) = 2.125, p = 0.04), while men directed their anger more towards themselves (anger expression in (b=, SE(b) = 2.628, p = .006)). For graphical demonstration, please see .

Following the same strategy as with the other questionnaires, generalized linear models revealed a heightened total impulsivity score (b = 0.656, SE(b) = 0.234, p = .005), but also augmented subscales ‘urgency’ (b = 0.750, SE(b) = 0.302, p = .013), ‘lack of premeditation’ (b = 1.187, SE(b) = 0.341, p < .001), and ‘lack of perseverance’ (b = 1.219, SE(b) = 0.302, p < .001) on a group comparison level. Intriguingly, an analysis on a gender*group level revealed greater urgency (b = 0.844, SE(b) = 0.393, p = .032) as well as increased sensation seeking (b = 1.340, SE(b) = 0.554, p = .015) among women. For graphical demonstration, please see .

Discussion

In summary, this study highlights the absence of gender differences concerning male-specific, atypical depressive symptomatology as assessed by the GSDS questionnaire. Consequently, questions about its usability arise. Unfortunately, the same uncertainty may extend to presumed male-specific symptoms overall (Oliffe et al., Citation2019). Particularly noteworthy is the finding that suicidal women reported greater sensation-seeking/risk-taking, short-sighted decision-making, and more pronounced anger directed towards objects and people. Interestingly, these features were accompanied by an angry personality trait, which could be linked to suicidal ideation (Hawkins et al., Citation2014). Strikingly, the only aspect significantly increased in men remained self-centered hatred; a finding that warrants exploration in future research.

The major limitations of this study include the limited number of participants and its reliance on self-reporting. Consequently, these results should be considered preliminary. However, over the course of two years, it proved challenging to recruit patients, especially those matching our stringent exclusion criteria. These criteria, however, constitute one of the major strengths of the current work, aiming to ensure an isolated examination of suicidality without several confounding variables that contribute to increased suicidal ideations or attempts (eg schizophrenia (Sher & Kahn, Citation2019)), bipolar disorder (Miller & Black, Citation2020), SUDs (Poorolajal et al., Citation2016), eating disorders (Smith et al., Citation2018) as well as chronic somatic illnesses (Rogers et al., Citation2021).

Further limitations concern the lack of scalar model invariance for the STAXI-II and I-8 scales when comparing suicidal and non-suicidal individuals (see Supplementum 1) as well as the significant difference in the educational levels between control and test group. While instructions for the questionnaires were provided with great care, it cannot be ruled out that differences in educational levels between the control group and patients may have led to misinterpretations and misunderstandings, potentially influencing the questionnaire scores.

It is also noteworthy that the present results are closely tied to the instruments used, the methodology for creating variables, and the statistical procedures employed. Therefore, the outcomes may not necessarily be replicated if alternative measures designed for assessing the same constructs were utilized. Similarly, employing different methodologies for calculating variable scores could yield divergent results. Additionally, alternative approaches, such as structural equation models, might produce different findings altogether.

Another strength, however, is the gender-based characterization of patients with acute suicidal ideations. As mentioned in the work by Zülke et al. (Citation2018), studies using a gender-based approach are scarce and often focus on validation populations and individuals with MDD, rather than acute suicidal patients (Martin et al., Citation2013; Rice et al., Citation2013; Rice et al., Citation2015). Surprisingly, the present results contrast with those reported in these articles. Not only did the study fail to provide evidence for male-specific depressive symptoms, but it also indicates that anger traits and outward aggression may be more prevalent in women. One possible explanation is that acute suicidality blurs any gender-specific symptomatology. Another explanation could be that gender differences in depression are hypothetical, as suggested by a study from Möller-Leimkühler and Yücel (Citation2010) which found a higher prevalence of male-specific depression, including male-specific symptoms, among female German university students. Nonetheless, further research among patients with acute suicidal ideations is urgently needed to identify and validate any true, if existing, gender-specific symptoms to develop better diagnostic tools and save lives.

In conclusion, the GSDS, a questionnaire designed to assess gender-specific suicidality, failed to achieve its intended purpose – at least in this initial set of participants. Furthermore, and yet surprising, women with acute suicidal ideations reported several augmented symptoms typically associated with men when compared to men with acute suicidal ideation.

Authors contribution

M.F. designed the study with input from J.S. and M.D. S.-M.S. and A.-K.G. recruited all participants and collected the data. J.S. was responsible for the statistical analysis. M.F. wrote the manuscript with the help of J.S. and M.D. All authors read and consented to the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the ethical review board of the Bavarian State Medical Association (Nr. 21007).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Becker and the team of the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy II, Ulm University for the excellent cooperation and the possibility to recruit patients there.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.F., upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah-Maria Soravia

Sarah-Maria Soravia and Ann-Kathrin Gosemärker are both nearing the completion of their medical studies, poised to embark on their journeys as healthcare professionals. Sarah-Maria Soravia has set her sights on a career in psychiatry, while Ann-Kathrin Gosemärker is preparing to serve as a general practitioner.

Ann-Kathrin Gosemärker

Sarah-Maria Soravia and Ann-Kathrin Gosemärker are both nearing the completion of their medical studies, poised to embark on their journeys as healthcare professionals. Sarah-Maria Soravia has set her sights on a career in psychiatry, while Ann-Kathrin Gosemärker is preparing to serve as a general practitioner.

Judith Streb

Dr. Judith-Streb is a seasoned psychologist with a wealth of experience in clinical research and statistical analysis. Her early career was dedicated to cognitive neuroscience, with a focus on EEG correlates and learning processes. However, since 2014, she has shifted her focus to different aspects of forensic psychiatric research.

Manuela Dudeck

Renowned in her field, Prof. Dr. Manuela Dudeck is an accomplished forensic psychiatrist, neurologist, and psychotherapist. She has authored and edited numerous books, scientific papers, and review articles in forensic psychiatry. Currently, she holds the position of chief clinician at the Clinic for Forensic Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the District Hospital Günzburg, as well as a full professorship in forensic psychiatry at Ulm University.

Michael Fritz

Prof. Dr. Michael Fritz brings over a decade of experience in preclinical neuroscience to his role as a psychologist. His previous work centered on animal models of addiction, depression, and psychoneuroimmunology. Since joining the Clinic for Forensic Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the District Hospital Günzburg, his research has shifted towards identifying predictive biomarkers of aggression and depression in both forensic psychiatric and general psychiatric patients.

References

- Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck scale for suscide ideation: Manual. Psychological Corporation.

- Branney, P., & White, A. (2008). Big boys don’t cry: depression and men. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 14(4), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.106.003467

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

- Giner, L., Blasco-Fontecilla, H., La Vega, D., & Courtet, P. (2016). Cognitive, Emotional, Temperament, and Personality Trait Correlates of Suicidal Behavior. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(11), 102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0742-x

- Hautzinger, M., & Bailer, M. (1993). Allgemeine depressions Skala (ADS). Beltz.

- Hawkins, K. A., Hames, J. L., Ribeiro, J. D., Silva, C., Joiner, T. E., & Cougle, J. R. (2014). An examination of the relationship between anger and suicide risk through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 50, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.005

- John, A., Eyles, E., Webb, R. T., Okolie, C., Schmidt, L., Arensman, E., Hawton, K., O’Connor, R. C., Kapur, N. Nav, Moran, P. O’Neill, S., McGuiness, L. A., Olorisade, B. K., Dekel, D., Macleod-Hall, C., Cheng, H., Higgins, Y., ‑Gunnell, J. P. T., & Moran, D.. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: Update of living systematic review. F1000Research, 9, 1097. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.25522.2

- Kliem, S., & Brähler, E. (2016). Beck-Suizidgedanken-Skala (BSS). Pearson.

- Kovaleva, A., Beierlein, C., Kemper, C. J., & Rammstedt, B. (2014). Die Skala Impulsives-Verhalten-8 (I-8). Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis183

- Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., & Gräfe, K. (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006

- Martin, L. A., Neighbors, H. W., & Griffith, D. M. (2013). The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs women: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(10), 1100–1106. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1985

- Miller, J. N., & Black, D. W. (2020). Bipolar disorder and suicide: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(2), 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-1130-0

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M., & Mühleck, J. (2020). Konstruktion und vorläufige Validierung eines gendersensitiven Depressionsscreenings (GSDS) [Development and Preliminary Validation of a Gender-Sensitive Depression Screening (GSDS)]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 47(2), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1067-0241

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M., & Yücel, M. (2010). Male depression in females? Journal of Affective Disorders, 121(1-2), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.007

- Oliffe, J. L., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Gordon, S. J., Creighton, G., Kelly, M. T., Black, N., & Mackenzie, C. (2016). Stigma in male depression and suicide: A Canadian sex comparison study. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9986-x

- Oliffe, J. L., Rossnagel, E., Seidler, Z. E., Kealy, D., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Rice, S. M. (2019). Men’s depression and suicide. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(10), 103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1088-y

- Pirkis, J., Gunnell, D., Shin, S., Del Pozo-Banos, M., Arya, V., Aguilar, P. A., Appleby, L., Arafat, S. M. Y., Arensman, E., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Balhara, Y. P. S., Bantjes, J., Baran, A., Behera, C., Bertolote, J., Borges, G., Bray, M., Brečić, P., Caine, E., … Spittal, M. J. (2022). Suicide numbers during the first 9-15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-existing trends: An interrupted time series analysis in 33 countries. EClinicalMedicine, 51, 101573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101573

- Poorolajal, J., Haghtalab, T., Farhadi, M., & Darvishi, N. (2016). Substance use disorder and risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide death: A meta-analysis. Journal of Public Health, 38(3), e282–e291. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv148

- Rice, S. M., Fallon, B. J., Aucote, H. M., & Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2013). Development and preliminary validation of the male depression risk scale: Furthering the assessment of depression in men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(3), 950–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.013

- Rice, S. M., Fallon, B. J., Aucote, H. M., Möller-Leimkühler, A., Treeby, M. S., & Amminger, G. P. (2015). Longitudinal sex differences of externalising and internalising depression symptom trajectories: Implications for assessment of depression in men from an online study. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(3), 236–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014540149

- Rogers, M. L., Joiner, T. E., & Shahar, G. (2021). Suicidality in chronic illness: An overview of cognitive-affective and interpersonal factors. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 28(1), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09749-x

- Rohrmann, S., Hodapp, V., Schnell, K., Tibubos, A. N., Schwenkmezger, P., & Spielberger, C. (2013). Das State-Trait-Ärgerausdrucks-Inventar - 2 Deutschsprachige Adaptation des State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2) von Charles D. Spielberger. Verlag Hans Huber.

- Schelhase, T. (2022). Suizide in Deutschland: Ergebnisse der amtlichen Todesursachenstatistik [Suicides in Germany: results from the official cause of death statistics]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 65(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-021-03470-2

- Sher, L., & Kahn, R. S. (2019). Suicide in schizophrenia: An educational overview. Medicina, 55(7), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070361

- Smith, A. R., Zuromski, K. L., & Dodd, D. R. (2018). Eating disorders and suicidality: What we know, what we don’t know, and suggestions for future research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.023

- Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(4), 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7

- Zülke, A. E., Kersting, A., Dietrich, S., Luck, T., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Stengler, K. (2018). Screeninginstrumente zur Erfassung von männerspezifischen Symptomen der unipolaren Depression – Ein kritischer Überblick [Screening instruments for the detection of male-specific symptoms of unipolar depression – A critical overview]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 45(4), 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-120289