Abstract

Cyberball, the paradigm developed by Kipling D. Williams and colleagues (Citation2000) to study ostracism, initially counted three experimental conditions: inclusion, exclusion, and overinclusion. The least known of these conditions is overinclusion, a social interaction characterized by excessive social attention (rather than fairness or no attention). This review provides an overview of original empirical studies implementing the overinclusion condition since its development. Following the PRISMA 2020 criteria, studies were drawn from four electronic databases (PubMed, Springer, PsycINFO, Web of Science), and Google Scholar was screened as a web-based academic search engine. In all, 33 studies met the inclusion criteria. Included studies described overinclusion specificities compared with exclusion and inclusion conditions, its effects in paradigms other than Cyberball, brain correlates associated with overinclusion, and its impact on clinical populations. 26 studies compared the inclusion and overinclusion conditions. 20 revealed significant differences between the two conditions, and 13 observed better mood and higher psychological needs satisfaction associated with the overinclusion condition. Studies investigating neural correlates revealed dACC involvement, P3 reduction, and P2 increase during overinclusion, supporting the idea of an ameliorative effect induced by the over-exposition to social stimulation. Findings on clinical populations suggest that overinclusion may help detect the social functioning of patients with psychological impairment. Despite the heterogeneity of the studies, our results showed that overinclusion can be associated with ameliorative psychological functioning. However, implementing standard guidelines for overinclusion will help provide a more thorough investigation of the psychological consequences of receiving excess social attention.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Cyberball is a virtual ball-tossing game used to study, in a controlled setting, the effects of ostracism, a social phenomenon that occurs when someone is excluded or ignored by others (Riva & Eck, Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2000). Ostracism has been defined as ‘being excluded and ignored’ (Williams & Nida, Citation2011), and it represents an instance of social exclusion, which has been defined as the experience of being kept apart from others physically (e.g. social isolation) or emotionally (e.g. being ignored or told one is not wanted). This includes different phenomena, such as social rejection (i.e. being explicitly told one is not wanted) and - as previously mentioned - ostracism (i.e. primarily characterized by being ignored) (Riva & Eck, Citation2016).

Cyberball has been widely used for over two decades, probably because of the simplicity of its use and the reproducibility of its effects. In 2015, Cyberball was administered to more than 11,000 participants worldwide (Hartgerink et al., Citation2015).

The game ostensibly involves a group of people tossing a virtual ball back and forth among them. Participants are told to play with other players (usually 2 or 3), which are actually controlled by a computer program. The course and speed of the game, the frequency of inclusion, players’ information, and iconic representation can be programmed by researchers. The paradigm allows manipulating independent variables such as the number of tosses received by the human player, the total number of tosses in each game, and the number of players (e.g. avatars). As regards observed measures, the most used one has been the Need Threat Scale (NTS) (Williams et al., Citation2000), which assesses the level of satisfaction of four fundamental needs: belongingness (i.e. the feeling of being connected to a group or another individual), self-esteem (i.e. self-attributions that constitute the value that each person has for themselves), control (i.e. the feeling of having control over one’s social environment), and meaningful-existence (i.e. the feeling of being recognized for existing and being worthy for attention; see (Williams, Citation2009).

The original version of the paradigm (Williams et al., Citation2000) included three different experimental conditions: (1) inclusion, in which all three players receive a fair amount of ball tosses (around 33%); (2) complete ostracism, in which the human player (experimental subject) is excluded receiving only two tosses at the beginning of the game and then never again; (3) partial ostracism, in which participants received the 20% of the total tosses, and (4) overinclusion in which the human player gets more than 33% (in a three players game) of the total tosses. For simplification and since partial ostracism is not considered as a peculiar condition in this systematic review, from here on in the manuscript the word ‘ostracism’ will refer to the condition of complete ostracism.

Overinclusion represents the other side of the ostracism coin. In the ostracism condition, the human participant receives no (or almost no) social attention from the fictitious players. In the overinclusion condition, the human participant receives most of the social attention from the fictitious players (Van Beest et al., Citation2011; Van Beest & Williams, Citation2006).

Initially, Williams et al. (Citation2000) decided to include the overinclusion condition to rule out the possibility that the adverse outcomes observed in the ostracism condition were due to feelings of conspicuousness and self-awareness rather than ostracism per se. The original (Williams et al., Citation2000) and the subsequent research (Van Beest et al., Citation2011) indicated this was not the case. Firstly, Williams et al. (Citation2000) showed that participants could detect overinclusion accurately; they perceived more throws during overinclusion than during inclusion and ostracism. Crucially, although both overinclusion and ostracism produced feelings of conspicuousness, overinclusion did not elicit any adverse effect, while ostracism did. Thus, the authors concluded that ostracism’s negative effects were not mere results of feelings of conspicuousness. Moreover, receiving most of the available social attention (e.g. being overincluded) resulted in a similar emotional experience to being included (Williams et al., Citation2000). This finding suggested that the participants’ emotional responses to the three conditions did not have a linear trend: overinclusion did not result in a more favorable outcome than inclusion and was, therefore, considered redundant. Based on these premises, most subsequently published studies using Cyberball relied only on two experimental conditions: inclusion (typically viewed as a baseline or a control condition) and exclusion (Hartgerink et al., Citation2015; Reinhard et al., Citation2019).

However, as a result of this choice, we were left with 25 years of data and research on the negative effects of ostracism and lack of social attention, with little information on the effects of increased social attention. For this reason, we think it might be interesting to investigate the other side of the ostracism coin, which is what the psychological effects of an excess of social attention are. For this reason, we think it might be interesting to investigate the other side of the ostracism coin, which is what the psychological effects of an excess of social attention are. Hence, we argue that good theoretical and methodological reasons exist to regain interest in the original overinclusion condition. Indeed, the overinclusion condition could be informative regarding the psychological and physiological consequences of various social interaction dynamics. In particular, from a social point of view, an excess of social attention can result in both a feeling of being overwhelmed and a positive sense of being important and powerful (Brewer, Citation1991); moreover, from a psychological and clinical perspective, the information about instances in which people receive excessive social attention could help shed light on peculiar psychological patterns, such as maladaptive interpersonal coping strategies, dysfunctional interpersonal emotional reactions, or hypervigilance to social stimuli (Reinhard et al., Citation2019). By further exploring overinclusion reactions, similar hypotheses may be developed and tested.

Over the years, sporadically, some studies have nevertheless used overinclusion for various reasons, both directly related to the phenomenon of overinclusion in Cyberball (i.e.Cheng et al., Citation2019; De Waal-Andrews & Van Beest, Citation2021; Anderson, Citation2011) and indirectly related to it (i.e. Bonow, Citation2013; Kwok et al., Citation2018; van Bommel et al., Citation2016) using the paradigm for other main purposes (see for the aims of the included studies). Some of these studies have considered using Cyberball to test the effect of excessive social attention on clinical populations. For instance, in the case of individuals suffering with borderline personality disorder (BPD), investigating these patients’ emotional reactions to overinclusion, as opposed to fair inclusion, aimed to explore the hypothesis that BPD patients would rely on atypical social norms when compared to healthy controls. Since patients with BPD react as if they were excluded regardless of objectively including or excluding social exchanges, considering the framework of expectancy violation might help understanding this response pattern. Among healthy controls, neural reactions to social exclusion also involve an expectancy violation mechanism. When approaching social exchanges, people expect others to follow the ‘unwritten rule’: to include them in a social interaction. The violation of this expectation activates brain areas signaling alarm, conflict, and threats to acceptance (Bolling et al., Citation2011; Somerville et al., Citation2006). Consequently, while healthy individuals are affected by social exclusion because this condition violates their implicit expectation of being included by others, people with BPD might react as if they were ostracized even in inclusion scenarios because fair inclusion violates their implicit expectations for extreme social inclusion. Therefore, evaluating whether BPD patients respond with lower negative emotions to the Cyberball overinclusion as compared to the inclusion and ostracism conditions can allow investigating whether this patient population relies on a higher threshold of social attention from others, which can result in rejection feelings even in fairly including scenarios (De Panfilis et al., Citation2015).

Table 1. Description of articles implementing overinclusion condition in the Cyberball paradigm (34).

Therefore, this systematic review focused on the empirical studies that adopted the overinclusion condition in Cyberball. We believe that a systematic review of studies using overinclusion can provide a more comprehensive and objective understanding of the methods and effects of its use, so that future studies can leverage this awareness to improve its application in experimental and clinical contexts. We decided to compare especially overinclusion to inclusion, reasoning that directly comparing overinclusion and ostracism would be more trivial as they represent the extremes of a continuum. First, we provided an overview of overinclusion implementation in literature, describing its methodological peculiarities across studies. Then, we presented the results of neuroscientific studies inquiring about brain activity during the detection of overinclusion. Finally, we reported the effects of overinclusion in clinical populations (e.g. borderline personality disorder, social anxiety, and eating disorders). We conclude by discussing the limits of this condition and further steps to improve its applicability, particularly in clinical settings.

Methods

Literature search

A literature search was conducted to select peer-reviewed original papers published online in English before the end of October 2021, following the PRISMA 2020 criteria (Supplementary material 1) (Page et al., Citation2021). We searched all studies that included the overinclusion condition in the Cyberball paradigm using ‘Cyberball overinclusion’ and ‘Cyberball over-inclusion’ as keywords to search in the title and abstract. We screened scientific databases (PubMed, Springer, PsycINFO, Web of Science) and the academic search engine Google Scholar. 2020. The algorithms used are shown in Supplementary Table S1. All experimental conditions with a percentage of ball-tosses higher than 33% were considered as overinclusion. This percentage is not arbitrary: indeed, being a game with 3 players, 33% is considered the fair number of ball passes among the three players. Hence, every higher percentage is an approximation of overinclusion.

We adopted the following exclusion criteria: papers written in languages other than English; papers published in other than journal articles or Ph.D./M.D. thesis; articles using paradigms different from Cyberball (or its main variations Cyberbomb, Claimball, and €yberball); articles without the overinclusion condition.

Records screening and quality assessment

For the duplicates removal and the title-abstract blinded screening process, two researchers (A.T. and F.P.) used Rayyan (rayyan.qcri.org/), a web and mobile systematic reviews manager (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016), to independently categorize results as ‘included’, ‘excluded’ or ‘maybe’. Then, the same two researchers analyzed the full texts of the remaining records and independently selected eligible studies. In both the title–abstract and full-text screening phases, ‘maybe’ and conflicting decisions were solved by consensus or discussed by consulting a third researcher (P.R.). One researcher (A.T.) extracted data using a structured form, collecting: (1) article characteristics (e.g. year of publication, author), (2) sample characteristics (e.g. patients vs. healthy control group, age, and sex), (3) operationalization of experimentally induced ostracism (paradigm characteristics), and (4) outcome measures. The other authors checked the data for consistency and accuracy (P.R. and M.C.). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

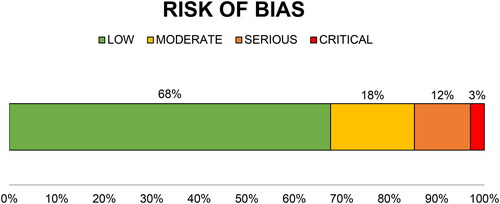

The quality of the included studies was assessed considering the following criteria, in order of importance: (1) blinding of participants; (2) randomization of participants; (3) sample size calculation; (4) blinding of the experimenter. We considered four levels of risk of bias: low level, when the criteria (1) and (2) were fully respected; moderate level, when (1) was fully respected but (2) was uncertain; serious level, when (1) was not respected; critical level, when more than three criteria including (1) were not respected. Two researchers independently checked the presence of each criterion in all papers included, scoring ‘yes’ when the criterion was respected, ‘no’ when it was not respected, and ‘unclear’ when the information was missing or not clearly reported.

Results

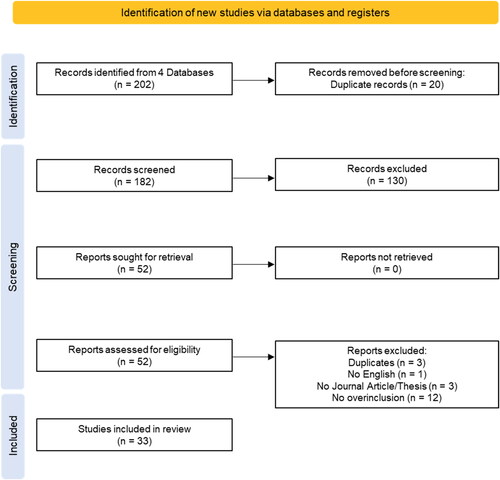

We identified a total of 202 publications. At the title-abstract review, we removed 20 duplicates and 126 records that did not meet our inclusion criteria. Then, we examined the full text of the remaining 56 records. We excluded 22 records at this stage: three were duplicates, one was excluded because it was not in English, three were excluded because they were not on journal articles or published thesis, three were excluded because they were not based on Cyberball, and 12 were excluded because they did not use overinclusion condition in their experiments. Thus, thirty-four studies met the criteria to be included in our review ( and ).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flowchart showing the selection process of papers.

The results of the quality assessment are reported in . We evaluated reporting bias based on the available details in each article. We calculated the number of studies that met the four criteria mentioned above: all but one study respected the blinding of participants (1); 23 of 33 studies (69%) respected the randomization of participants, and 6 of 33 (18%) did not mention the randomization method (2); 9 of 33 studies (27%) respected the sample size calculation (3); finally, only 3 of 33 studies (9%) declared that experimenters were also blinded (4). Overall, only one study did not respect any criteria (Burgdorf et al., Citation2016), and only one study respected them all (Grossman, Citation2019). The blinding of participants was the most respected compared to the others. Based on these considerations, 69% of the cited studies meet the indicative criteria for good study quality, while the results of the studies out of the 68% reporting a moderate, serious, and critical risk of bias may include major biases that could affect the validity of the results, which should be consequently interpreted with caution.

Figure 2. Risk of bias evaluation of the papers extracted from the systematic review procedure. The bar represents the percentage of studies with different degrees of risks of bias: low (green) = randomization and blinding of participants criteria were respected; moderate (yellow) = blinding of participants criterion was respected but randomization data were incomplete; serious (orange) = not respecting the randomization criterion; critical (red) = not respecting any criteria.

Characteristics of included studies

The studies that were included in the systematic review are published articles in peer-review scientific journals () and six published Ph.D. or master’s degree theses (Bonow, Citation2013; Ghosh, Citation2021; Grossman, Citation2019; Okanga, Citation2021; Peake, Citation2016; Shade, Citation2010). The overall number of participants is 7.344, with an average age of 34.5 ± 0.5. The mean percentage of tosses used to obtain overinclusion is 49%, but the total number of tosses changed over a wide range from 15 to 200. Six studies implemented only exclusion and overinclusion (Bonow, Citation2013; Cheng et al., Citation2019; De Waal-Andrews & Van Beest, Citation2021; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020; Citation2022; Okanga, Citation2021), and five implemented only inclusion and overinclusion (Grossman, Citation2019; Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021; Niedeggen et al., Citation2014; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018; Citation2021). Eight studies used a between-group design, fourteen were within-group studies, and twelve had a mixed study design (between-within-subject study). Six studies tested Cyberball effects on clinical populations (De Panfilis et al., Citation2015; Ghosh, Citation2021; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020; Citation2022; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018, Citation2021), and six studies investigated the neural correlates elicited by the Cyberball paradigm (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021; Kawamoto et al., Citation2012; Niedeggen et al., Citation2014; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). Four studies structured the Cyberball manipulation as a seamless succession of all the experimental conditions resulting in rounds of inclusion mixed with overinclusion, rounds of inclusion mixed with exclusion, or a gradual increase or decrease of tosses to obtain social inclusion or exclusion (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Ho et al., Citation2014; Okanga, Citation2021; Peake, Citation2016). Regarding the outcomes’ evaluation of Cyberball, all the selected studies assessed the number of tosses perceived by participants (this measure is usually considered a manipulation check). Nineteen studies used the Need Threat Scale (NTS) to measure the psychological effects of the paradigm, and two used overinclusion as a debriefing phase with children (White et al., Citation2016; Citation2021). See for further details. Guided by the contents of the articles included in the systematic review, we decided to describe the included articles by dividing them into three groups to facilitate reading. Specifically, in addition to the general category of articles comparing the effects of inclusion and overinclusion, we categorized articles concerning clinical populations and those adopting specific neuroscience techniques to investigate the effects of overinclusion on the human brain.

Among our thirty-three selected studies, six (Bonow, Citation2013; Cheng et al., Citation2019; De Waal-Andrews & Van Beest, Citation2021; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020; Citation2022; Okanga, Citation2021) directly compared the effects of social exclusion to those of overinclusion, omitting the inclusion condition, acknowledged as the baseline to evaluate the paradigm effects on the emotional and psychological well-being of the participants (Riva et al., Citation2014).

In these six studies, participants assigned to the overinclusion condition reported receiving more ball tosses than those in the exclusion condition. Furthermore, all but one (Cheng et al., Citation2019) study reported that overinclusion is associated with improved mood and higher satisfaction with basic psychological needs (Bonow, Citation2013; De Waal-Andrews & Van Beest, Citation2021; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020; Citation2022; Okanga, Citation2021). Further details on these studies are available in Supplemental materials, Table S3.

However, the direct comparison of exclusion and overinclusion could mask the specificity of the condition of overinclusion as it compares two extremes of social attention (ostracism, not receiving attention; overinclusion, receiving more attention than other players receive). Indeed, both exclusion and overinclusion represent conditions that ‘alter’ the baseline state, but when the baseline state isn’t measured, it becomes challenging to deduce the actual impact that either condition has on the outcome variable. Therefore, the emerging results could be less reliable. In conclusion, we believe that the direct comparison between exclusion and overinclusion, while confirming the outcome of improvement in mood and fundamental needs, does not add more valuable information to the results; instead, it represents a methodological limitation. More interesting is to know if overinclusion is different from fair inclusion in Cyberball, namely, if excessive social attention represents a psychologically different condition from a fair share of social attention. To date, this issue is unsolved.

To address this, we decided to focus mainly on selecting twenty-six studies that have dealt with the difference between the effects induced by a condition of equal social attention between players (inclusion) and those generated by a condition of greater attention towards the human participant (overinclusion).

Comparing overinclusion and inclusion conditions

Twenty-five studies compared the inclusion and overinclusion conditions. One mentioned overinclusion in methods, but its related outcomes have not been described (Lansu et al., Citation2017). Among the remaining twenty-four studies, nineteen (79%) reported statistically significant differences between the effects of the two inclusion conditions. Compared to inclusion, all the nineteen studies reported that overinclusion is associated with the perception of getting more ball tosses. Twelve of them (50%) reported also improved psychological needs and mood of the participants (Anderson, Citation2011; Burgdorf et al., Citation2016; De Panfilis et al., Citation2015; Erel et al., Citation2021; Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021; Kwok et al., Citation2018; Niedeggen et al., Citation2014; Schrantz et al., Citation2021; Van Beest et al., Citation2011; van Bommel et al., Citation2016; Venturini et al., Citation2016; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018). One study associated these positive emotional effects with social pain reduction (Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021), and another with a physiological state typical of relaxation (Burgdorf et al., Citation2016). The positive effects of overinclusion on the participants’ psychological well-being were also tested by modifying the meaning assumed by the condition of overinclusion. Finally, only one study reported a possible effect of overinclusion on behavior. Specifically, investigating the impact of various levels of social inclusion on participants’ willingness to make false confessions in court, the authors found a lower frequency of false confessions in included and overincluded participants compared to excluded participants (Schrantz et al., Citation2021).

Six studies compared inclusion and overinclusion without finding statistically significant differences (Ghosh, Citation2021; Goodwin et al., Citation2010; Hawkley et al., Citation2010; Lansu et al., Citation2017; Leitner et al., Citation2014; Peake, Citation2016). Of these, two used a few game tosses (i.e. fifteen; Goodwin et al., Citation2010; Hawkley et al., Citation2010), with a percentage of tosses received by the participant equal to 50% in overinclusion and 33% in inclusion. Not finding any differences between the two conditions, the authors collapsed the overinclusion data with those of the inclusion. Six studies found no difference between inclusion and overinclusion. The lack of significance could not be accounted for by the type of study (between or within), the total number of tosses, the order of conditions, the outcome measures, and the number of game rounds. None of these variables were differently addressed in studies finding statistical differences between inclusion and overinclusion.

Brain activity involved in overinclusion detection

Among our selected studies, six investigated the neural correlates associated with the experience of Cyberball overinclusion. Two studies used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Kawamoto et al., Citation2012), and four used event-related potentials (ERPs) (Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021; Niedeggen et al., Citation2014; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018, Citation2021).

Both fMRI studies inquired about the involvement of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), which has been previously associated with detecting social exclusion and non-social expectancy violation. Kawamoto et al. (Citation2012) found a selective increase of dACC activation during the ostracism condition, which did not occur in any other Cyberball conditions, even overinclusion. Furthermore, no significant cortical activations were associated with overinclusion, and no differences in the neural correlates between inclusion and overinclusion were detected (Kawamoto et al., Citation2012). Cheng et al. (Citation2019) documented an increase in the activation of the dACC passing from an overinclusion to an exclusion condition and a decrease in the activation of the dACC passing from the exclusion to the overinclusion condition. Thus, according to the authors, dACC was not sensitive to the specific condition of ostracism but to the transition from one condition to another (Cheng et al., Citation2019). However, this issue remains open to further investigation.

Four studies recorded ERPs, a neurophysiological technique able to detect electrical activity generated in the brain structures in response to specific events or stimuli, in this case, Cyberball games. They found peculiar neural activity during the overinclusion session: a reduction in the amplitude of P3 and an increase in the amplitude of P2, especially when experiencing overinclusion after inclusion (Niedeggen et al., Citation2014; Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2021). In the literature, P3 is associated with decision-making processes and subjects’ reactions to unexpected or infrequent stimuli, while P2 is related to social reward processes. Overall, the neurophysiological results suggest that overinclusion might be experienced as less unexpected but more socially rewarding than fair inclusion. These results also align with participants’ behavioral responses in the psychological needs satisfaction questionnaires (Niedeggen et al., Citation2014; Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021). In this regard, it can be noted that the unexpectedness may be accounted for by the greater uncertainty for the human participant in the inclusion condition than in the overinclusion one. As opposed to the inclusion condition, indeed, in the overinclusion condition, the behavior of the other two players becomes easily predictable since the early stage of the game.

Two studies cited in this section analyzed physiological responses in clinical populations (Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2021). Considering the neurophysiological data of these two studies, patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD) showed a greater amplitude of P3 than healthy controls both during the inclusion and the overinclusion conditions, signaling that both conditions violated patients’ expectations. However, when overincluded, BPD and SAD patients showed a reduction of P3 like healthy controls did, indicating that overinclusion violates their expectations to a lesser extent than inclusion (Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018). Differently, the population of SAD patients differed from the non-clinical and BPD populations due to the absence of the P2 increase in correspondence with the overinclusion condition, suggesting that overinclusion is not processed at the neural level as a socially rewarding stimulus by SAD patients. The authors concluded that SAD and BPD patients differ in processing social participation. Compared to healthy controls and BPDs, SAD patients show greater difficulty in appreciating, at the neural level, the increased social involvement induced by overinclusion in Cyberball (Weinbrecht et al., Citation2021).

Overinclusion effects on clinical populations

Despite the small effects of overinclusion on healthy subjects, Cyberball overinclusion has been increasingly adopted and revealed to be particularly effective as an emotional trigger in the clinical population (Reinhard et al., Citation2019). However, to date, only five studies investigated the specific role of the overinclusion condition involving BPD, SAD (De Panfilis et al., Citation2015; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018, Citation2021), Anorexia Nervosa, and patients who underwent Obesity Surgery (Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020, Citation2022).

Considering the BDP and SAD groups, three studies reported that patients experienced fewer positive emotions than healthy controls (De Panfilis et al., Citation2015; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2021).

Regarding BPD, two studies reported that patients experienced greater rejection-related emotions and negative mood than healthy controls during the inclusion condition but comparable levels during the overinclusion condition. These findings suggest that BPD patients may need a greater share of social attention than healthy controls to feel included. However, BPD patients reported fewer feelings of social connection and less need satisfaction than healthy controls during both the inclusion and overinclusion conditions (De Panfilis et al., Citation2015; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018).

Concerning SAD populations, two of the studies mentioned above compared their subjective and EEG responses to inclusion and overinclusion with those of healthy controls and BPD patients (Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). Similarly to BPD patients, individuals with SAD reported higher levels of ostracism intensity and negative mood than healthy controls in the inclusion but not in the overinclusion condition. However, differently from BPD patients, overinclusion in the SAD group also led to decreased perceived need threats to levels comparable to those of healthy controls, suggesting a BPD-specific bias to feel threatened in one’s need to belong even in a condition of extreme inclusion.

Considering eating disorders, the studies on the Anorexia Nervosa population (Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020) did not find differences between patients and controls in perceived mood and needs satisfaction during the overinclusion condition. The authors only found that during the overinclusion condition, both patients and controls correctly recognized receiving more ball tosses than during the exclusion condition (Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020). The other study involving the Obesity Surgery clinical population (Meneguzzo et al., Citation2022), instead showed that, compared to healthy controls, patients underestimated the percentage of ball tosses received during both ostracism and overinclusion. No other differences between groups related to the overinclusion condition were found. Interestingly, Obesity Surgery patients, but not healthy controls, did not perceive differences between the exclusion and the overinclusion conditions in feelings of Self-Esteem and Meaningful existence (Meneguzzo et al., Citation2022). This result revealed that patients were less aware of their exclusionary status; thus, they seemed less vulnerable to ostracism than controls. Both latter studies used exclusion and overinclusion conditions, omitting the inclusion baseline (Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2022). This choice was motivated by the first study on patients with anorexia nervosa, stating that exclusion and overinclusion required skills to manage socially exclusive experiences, which were the most salient for the clinical population under examination. Consequently, we cannot fully understand the role of overinclusion with such patients.

General discussion

Among the Cyberball experimental conditions, the one that has been ‘ostracized’ by researchers since its introduction is the overinclusion condition. The main reason for this neglect might be how overinclusion was initially presented. Kipling D. Williams et al. (Citation2000) were mainly interested in studying the effects of ostracism and implemented overinclusion only to control possible effects on the participants’ sense of conspicuousness. Finding no significant differences between the overinclusion and the inclusion conditions, the authors concluded that participants did not perceive overinclusion as different from the inclusion condition. Thus, in subsequent studies, leaving out the overinclusion condition was probably a good way to economize experimental resources (e.g. number of participants in between-subject designs and experiment duration in within-subjects designs).

Despite this, it was later noticed that overinclusion could have peculiar psychological and physiological effects, and that it can impact differently on people, according to their individual differences. In support of this hypothesis, a study in 2018 pointed out the importance of exploring social inclusion effects, showing that when participants are the target of specific social attention, their mood and fundamental needs are fortified (Simard & Dandeneau, Citation2018). Moreover, a meta-analytic study, published after our systematic review was conducted and aimed at understanding the impact of overinclusion in Cyberball and the role of social anxiety in this process (Hay et al., Citation2023), revealed that the impact of overinclusion on participants’ psychological well-being, namely positive affect, feelings of belongingness, self-esteem, meaningful existence and control, may change according to their individual differences.

Psychological and cognitive effects of overinclusion on clinical populations

In line with the hypothesis of psychological effects related to the overinclusion condition, our systematic review highlighted that overinclusion was perceived as different from fair social inclusion in twenty out of twenty-six studies (equal to 77%) that compared these two critical conditions. More specifically, in thirteen (50%) of these studies, overincluded participants showed improved psychological needs or mood compared to fairly included ones. This is further supported by reduced social pain (Ikeda & Takeda, Citation2021) and a physiological state typical of relaxation (Burgdorf et al., Citation2016). Our finding aligns with Hay et al. (Citation2023) detecting a small effect of overinclusion on positive affect and a moderate effect on fundamental needs, mainly belonging and control.

Concerning the feeling of conspicuousness determined by overinclusion, the results of our review suggest that being overincluded may be a form of standing out (Van Beest 2011; De Waal-Andrews & Van Beest, Citation2021). Indeed, if ostracism represents a deprivation of attention, in the case of overinclusion, it involves an excess of attention. In some non-clinical social groups, such as famous and popular people, both standing out and being at the center of someone’s attention are quite common. Moreover, ‘fame’ seems to be related to higher feelings of belongingness (Greenwood et al., Citation2013) and self-esteem (Utz et al., Citation2012), both included in the fundamental needs (Williams et al., Citation2000). Hence, we could consider that popularity and standing out phenomena are conceptually similar to the overinclusion effects. However, Cyberball overinclusion represents a specific condition within an experimental paradigm, where the phenomenon is directly elicited during the investigation itself. On the contrary, popularity is a more complex and identity-related construct. Indeed, it is typically investigated through peer hierarchical evaluations or status assessments: those ranked highest in these evaluations are typically identified as ‘popular’ (Cillessen & Marks, Citation2011). In this sense, one (overinclusion) represents a state variable while the other (popularity) a trait variable, but beyond this key difference future research should consider exploring the links between these two constructs.

However, the standing out phenomenon may be particularly relevant when overinclusion is applied to clinical populations. We identified a few clinical populations on which overinclusion was tested. The results supported the idea that the overinclusion condition can modulate the participants’ emotionality and that their baseline psychic status can affect their reaction to Cyberball conditions differently.

In line with Hay et al.’ meta-analysis (2023), we found that overinclusion has a particular subjective effect on social anxiety disorder (SAD) patients due to their baseline low levels of mood and feelings of belongingness in the inclusion condition. Specifically, both of them increase to levels comparable to those of healthy controls during overinclusion (Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018), and this result is in line with those of Hay et al. (Citation2023). However, neuroscientific studies have also revealed that these individuals are not as socially rewarded as healthy people by being overincluded (Weinbrecht et al., Citation2021). This aligns with the impaired positivity hypothesis in SAD, according to which this patient population would process and experience positive social information more negatively (Gilboa-Schechtman et al., 2014). Therefore, people with SAD may need stronger signals to feel included while still disliking being in the spotlight.

Also individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) show a biased processing of social inclusion. Indeed, fair inclusion is considered unexpected and associated with greater negative emotions and lower feelings of belongingness compared to healthy controls. Conversely, overinclusion is perceived as socially rewarding and reduces negative emotions to levels similar to healthy controls. However, even when overincluded, BPD patients still report lower feelings of belongingness and process overinclusion as more unexpected than controls (although less unexpected than fair inclusion; De Panfilis et al., Citation2015; Weinbrecht et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). These findings suggest that individuals with BPD could rely on atypical social norms: their profound, inner need to be ‘extremely’ included by others would make them experience fair inclusion as distressing and unexpected. This response pattern is only partially mitigated by the overinclusion condition, effectively improving their negative emotions but not feelings of belongingness. Nonetheless, violating patients’ expectations less and being evaluated as more socially rewarding than fair inclusion, overinclusion seems closer to meeting their unrealistic need of being extremely included by others.

However, the number of investigated psychopathologies is still limited. Yet, implementing overinclusion could be an opportunity to examine the social and relational abilities of patients suffering from clinical conditions. More broadly, many psychological disorders are characterized by relational and social cognition difficulties (Andreou et al., Citation2015; Ridenour et al., Citation2019). Given the dual nature of an emotional enhancer and social attention centralizer, future studies should take advantage of overinclusion to test the social abilities and social cognition patterns of patients with difficulties in these domains. Regarding cognitive skills in general, we could identify only one study that used the overinclusion of Cyberball testing decision-making skills. The results of this study suggested a promising use of Cyberball’s overinclusion in cognitive assessment contexts (Schrantz et al., Citation2021).

The role of overinclusion as a maximizer of social attention

A question that may arise about overinclusion is whether the need to feel included follows a maximizing principle (i.e. the more the social attention the better) or an optimizing principle (i.e. there is an optimal level of belongingness and higher levels of social attention can be experienced as overwhelming). This concept is also intertwined with Brewer’s ‘Optimal Distinctiveness Theory’ (1991), suggesting that humans are driven by two main needs: the need of inclusion, corresponding to the need for cooperation to survival and adaptation, and the need for differentiation, that concerns the need to differentiate from others when the need for inclusion is adequately met. Baumeister and Leary (Citation1995) in their foundational work about the need to belong propose that it is subjected to the satiation principle, implying that after an optimal satisfaction level, human beings no longer seek for social connections. Our systematic review revealed that overinclusion can be beneficial especially in those cases where people feel less connected at baseline, like patients with SAD and BPD, thus suggesting that there may be an optimal level of inclusion. Nevertheless, future studies are needed to examine in greater depth this aspect.

Methodological heterogeneity in implementing the overinclusion condition

Despite the promising obtained results, some characteristics of the paradigm implementation must be considered to determine the strength of overinclusion effects effectively. The heterogeneity in Cyberball implementation, particularly in overinclusion conditions, is the first critical point revealed by our systematic analysis. We argue that methodological differences (e.g. different numbers of tosses, different percentages of overinclusion, different game time, and implementation settings) in applying the overinclusion condition have strongly limited the results’ reliability and generalizability. For example, too short games with few ball passages may not give enough information to participants to detect differences between inclusion and overinclusion. We also noted that four studies used the paradigm by implementing conditions in rounds, creating a continuum between one condition and another in a single play session, thus mixing the conditions (Ho et al., Citation2014; Peake, Citation2016; Cheng et al., Citation2019; Okanga, Citation2021). This implementing mode could have reduced the effectiveness of each paradigm condition in eliciting specific psychological reactions. Furthermore, Cyberball was initially developed as a paradigm with a between-subjects design (Williams et al., Citation2000), and adopting a within-subjects design could interfere with its psychological effects. In some cases, authors have good reasons to modify the original Cyberball parameters (e.g. Okanga, Citation2021; White et al., Citation2016; Hawkley et al., Citation2010); however, in our opinion, when possible, it is critical to keep the implementation parameters stable and in line with those of the paradigm developers.

Based on this review, there is a need to develop guidelines on the overinclusion condition. In this regard, the percentage of tosses used to induce overinclusion is of primary importance. According to the data emerged from our review, the human player should receive at least 40% of total tosses to be considered overinclusion. Indeed, 40% is the minimum percentage of tosses set to induce the overinclusion condition in the studies included in this review (), and their results significantly indicated that the overinclusion condition produced some different effects compared to the inclusion condition. Only Shade (Citation2010) adopted a lower percentage because the game did not have the typical 3-player setting but rather a 4-player setting, and in that case the related percentage for a fair game was 25.5%. Therefore, for overinclusion, it was a lower value than 40%, namely 35%. Consequently, we conclude that 40% is the least amount of ball tosses needed to induce the overinclusion condition.

Moreover, it is crucial always to have the inclusion condition as a control, as the studies that did not implement it (Bonow, Citation2013; Cheng et al., Citation2019; De Waal-Andrews & Van Beest, Citation2021; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2020; Meneguzzo et al., Citation2022) do not allow inferences to be drawn on the specificity of overinclusion effects. Finally, further studies are needed to point out the best settings to elicit overinclusion effects, and gold standards on programming parameters (e.g. number of total passes) should be proposed and adopted to apply the overinclusion condition profitably.

Conclusions

We reviewed the studies that used the overinclusion condition in Cyberball paradigms following a standard and replicable process, as outlined in the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews. In this review, we focused on the overinclusion condition starting from its original development within the Cyberball paradigm, which has been the primary context for exploring this condition. However, a few other paradigms have been introduced over the decades to study the phenomenon of social exclusion. Some of these paradigms could also elicit an overinclusion condition, such as the Ostracism Online paradigm (Wolf et al., Citation2015) and the O-Cam (Goodacre & Zadro, Citation2010; see Riva & Eck, Citation2016). Therefore, further reviews may consider broadening the perspective to include these paradigms. Despite the heterogeneity of its usage and results, we documented specific positive effects of overinclusion in eighteen of twenty-six included studies that compared inclusion and overinclusion conditions.

Future research should consider that overinclusion can be perceived as a qualitatively independent condition from inclusion in Cyberball. We, therefore, suggest using the overinclusion condition in studies aimed at investigating emotional and behavioral reactions to excessive social attention, with particular interest in clinical populations. To our account, both the lack of social attention (i.e. the ostracism condition) and an excess of it (as induced in the overinclusion condition) can provide valuable knowledge on psychological functioning during social interactions.

Cogent_Alt_Text_figures.docx

Download MS Word (13.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Francesca Pellegrini for her help with papers selection and quality assessment of the included studies in this systematic review.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://osf.io/fd8jx/?view_only=db244ee956bb4eb085dd8e346924206b.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alessandra Telesca

Alessandra Telesca is clinical researcher at the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the IRCCS “Carlo Besta” Neurological Institute of Milan, Italy. She obtained her Ph.D. in Clinical Neuroscience at the University of Milano-Bicocca. Her main research interest is approaching the pain domain from different perspectives, with particular attention to the social aspects of pain. She explores the cognitive and psychological functioning of patients suffering from chronic pain, integrating the neuropsychological evaluation with the application of non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. Moreover, she is interested in investigating the neurophysiological aspects of some pain related phenomena such as nociception and the cognitive processing of pain stimuli, both patients and healthy subjects. In Social Connections & Technology Lab, she contributes to evaluating social pain in chronic pain populations, proving the efficacy of experimental social cognition paradigms.

Alessia Telari

Alessia Telari is a Ph.D. student in Social, Cognitive and Clinical Psychology at the University of Milano-Bicocca, where she is part of the Social Connections & Technology Lab. Her main research interest concerns social exclusion and social connectedness. Currently, she is investigating the impact of digital technologies (i.e. social media, artificial intelligence systems, smartphones) on social connections, both as social interference and facilitator, and people’s response to different degrees of social exclusion (and inclusion) in healthy and clinical populations.

Monica Consonni

Monica Consonni is a researcher of the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the IRCCS “Carlo Besta” Neurological Institute of Milan, Italy. She obtained degree in Experimental Psychology in 2005 and PhD in Neuroscience in 2010 at the V-S San Raffaele University of Milan. Since 2011 she works as neuropsychologist at the IRCCS “Carlo Besta” Neurological Institute of Milan. Her research interests and clinical activities focus on the identification of cognitive and behavioural impairment of patients with neurodegenerative diseases and chronic pain. Since 2020 she serves as Review Editor of Frontiers Neuroscience.

Chiara De Panfilis

Chiara De Panfilis is an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Medicine and Surgery of Parma University. Her research focuses on personality disorders and, specifically, on the social-cognitive styles that underlie the difficulties in interpersonal functioning exhibited by this patient population. She investigates how individuals affected by personality disorders perceive and react to various social cues, such as social exclusion and inclusion, facial expressions, emotional body language, cooperative behavior, with the goal to elucidate potential social-cognitive biases that could be addressed in treatment.

Paolo Riva

Paolo Riva is an Associate Professor at the University of Milano-Bicocca Psychology Department. He is the Director of the Social Connections & Technology Lab (https://connectlab.psicologia.unimib.it/). His research interests lie broadly in social influence processes with a specific focus on the need to belong and its threats, including social exclusion, ostracism, and rejection, examining the consequences of exclusion and the possible strategies to buffer against and reduce its effects. He currently explores the impact of digital technologies on social connections and isolation processes, social exclusion in real groups, and brain mechanisms involved in emotion regulation following exclusion.

References

- Anderson, J. (2011). The cost of exclusion and the benefit of overinclusion: Individual differences moderate sensitivity to inclusionary status. Human Development (HD). Thesis.

- Andreou, C., Kelm, L., Bierbrodt, J., Braun, V., Lipp, M., Yassari, A. H., & Moritz, S. (2015). Factors contributing to social cognition impairment in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 229(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.057

- Baumeister, R. F., Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

- Bolling, D. Z., Pitskel, N. B., Deen, B., Crowley, M. J., McPartland, J. C., Mayes, L. C., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2011). Dissociable brain mechanisms for processing social exclusion and rule violation. NeuroImage, 54(3), 2462–2471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.049

- Bonow, J. T. (2013). Contextual behavioral influences of perceptions of relationship partners: An analogue study. University of Nevada.

- Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001

- Burgdorf, C., Rinn, C., & Stemmler, G. (2016). Effects of personality on the opioidergic modulation of the emotion warmth-liking. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 524(8), 1712–1726. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.23847

- Carter-Sowell, A. R., Wesselmann, E. D., Wirth, J. H., Law, A., Chen, Z., Kosasih, M. W., … & Williams, K. D. (2010). Strides for belonging trump strides for superiority: Effects of being ostracized for being superior or inferior to the others. Journal of Individual Psychology, 66(1).

- Cheng, T., Vijayakumar, N., Flournoy, J. C., de Macks, Z. O., Peake, S. J., Flannery, J. E., … Pfeifer, J. H. (2019). Feeling left out or just surprised? Neural correlates of social exclusion and expectancy violations in adolescence. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 20(2), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-020-00772-x.

- Cillessen, A. H., & Marks, P. E. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring popularity. In A. H. N. Cillessen, D. Schwartz, & L. Mayeux (Eds.), Popularity in the Peer System, 25–56. The Guilford Press.

- De Panfilis, C., Riva, P., Preti, E., Cabrino, C., & Marchesi, C. (2015). When social inclusion is not enough: Implicit expectations of extreme inclusion in borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders, 6(4), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000132

- De Waal-Andrews, W., & Van Beest, I. (2021). Reactions to claimed and granted overinclusion: Extending research on the effects of claimball versus cyberball. The Journal of Social Psychology, 160(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2019.1610348

- Erel, H., Cohen, Y., Shafrir, K., Levy, S. D., Vidra, I. D., Tov, T. S., & Zuckerman, O. (2021 Excluded by robots: Can robot-robot-human interaction lead to ostracism? [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Boulder, CO, USA.

- Ghosh, A. (2021). Influence of social rejection and borderline personality features on emotion perception. Honors Thesis, 159.

- Gilboa-Schechtman, E., Shachar, I., & Sahar, Y. (18 March 2014). Positivity impairment as a broad-based feature of social anxiety. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Sec. Cognitive Neuroscience, Volume 8–2014.

- Goodacre, R., & Zadro, L. (2010). O-Cam: A new paradigm for investigating the effects of ostracism. Behavior Research Methods, 42(3), 768–774. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3.768

- Goodwin, S. A., Williams, K. D., & Carter-Sowell, A. R. (2010). The psychological sting of stigma: The costs of attributing ostracism to racism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(4), 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.02.002

- Greenwood, D., Long, C. R., & Dal Cin, S. (2013). Fame and the social self: The need to belong, narcissism, and relatedness predict the appeal of fame. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.020

- Grossman, J. T. (2019). Fear of positive evaluation and negative affect from inclusion in Cyberball arts and dissertations, 1984.

- Hartgerink, C. H. J., van Beest, I., Wicherts, J. M., & Williams, K. D. (2015). The ordinal effects of ostracism: A meta-analysis of 120 Cyberball studies. PLoS One, 10(5), e0127002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127002

- Hawkley, L. C., Williams, K. D., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Responses to ostracism across adulthood. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 6(2), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq045

- Hay, D. E., Bleicher, S., Azoulay, R., Kivity, Y., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2023). Affective and cognitive impact of social overinclusion: A meta-analytic review of cyberball studies. Cognition & Emotion, 37(3), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2022.2163619

- Ho, E. J., Surenkok, G., & Zayas, V. (2014). Explicit but not implicit mood is affected by progressive social exclusion. Journal of Interpersonal Relations, Intergroup Relations and Identity, 7, 22–37.

- Ikeda, T., & Takeda, Y. (2021). Effects of holding soft objects during Cyberball tasks under frequent positive feedback. Experimental Brain Research, 239(2), 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-020-06000-9

- Kawamoto, T., Onoda, K., Nakashima, K., i., Nittono, H., Yamaguchi, S., & Ura, M. (2012). Is dorsal anterior cingulate cortex activation in response to social exclusion due to expectancy violation? An fMRI study. Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience, 4, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnevo.2012.00011

- Kwok, C., Grisham, J. R., & Norberg, M. M. (2018). Object attachment: Humanness increases sentimental and instrumental values. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1132–1142. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.98

- Lansu, T. A., van Noorden, T. H., & Deutz, M. H. (2017). How children’s victimization relates to distorted versus sensitive social cognition: Perception, mood, and need fulfillment in response to Cyberball inclusion and exclusion. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 154, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2016.10.012

- Leitner, J. B., Hehman, E., Deegan, M. P., & Jones, J. M. (2014). Adaptive disengagement buffers self-esteem from negative social feedback. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(11), 1435–1450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214549319

- Meneguzzo, P., Collantoni, E., Bonello, E., Busetto, P., Tenconi, E., & Favaro, A. (2020). The predictive value of the early maladaptive schemas in social situations in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 28(3), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2724

- Meneguzzo, P., Tenconi, E., Collantoni, E., Longobardi, G., Zappalà, A., Vindigni, V., Favaro, A., & Pavan, C. (2022). The Cyberball task in people after obesity surgery: Preliminary evaluation of cognitive effects of social inclusion and exclusion with a laboratory task. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 27(4), 1523–1533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01297-z

- Niedeggen, M., Sarauli, N., Cacciola, S., & Weschke, S. (2014). Are there benefits of social overinclusion? Behavioral and ERP effects in the Cyberball paradigm. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 935. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00935

- Okanga, E. A. (2021). Subjective well-being buffers the effects of social exclusion and expression of in-group favouritism in real groups. University of Otago.

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Peake, S. (2016). Susceptibility to peer influence, social exclusion, and adolescent risky decisions.

- Reinhard, M. A., Dewald-Kaufmann, J., Wüstenberg, T., Musil, R., Barton, B. B., Jobst, A., & Padberg, F. (2019). The vicious circle of social exclusion and psychopathology: A systematic review of experimental ostracism research in psychiatric disorders. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 270(5), 521–532. 00401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-01074-1

- Ridenour, J. M., Lewis, K. C., Poston, J. M., & Ciecalone, D. N. (2019). Performance-based assessment of social cognition in borderline versus psychotic psychopathology. Rorschachiana, 40(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1027/1192-5604/a000114

- Riva, P., & Eck, J. (2016). Social exclusion: Psychological approaches to understanding and reducing its impact. Springer.

- Riva, P., Williams, K. D., Torstrick, A. M., & Montali, L. (2014). Orders to shoot (a camera): Effects of ostracism on obedience. The Journal of Social Psychology, 154(3), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2014.883354

- Schrantz, K. N., Nesmith, B. L., Limke-McLean, A., & Vanhoy, M. (2021). I’ll confess to be included: Social exclusion predicts likelihood of false confession. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 38(2), 293–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-020-09414-x

- Shade, C. K. (2010). The effect of rejection sensitivity on perceptions of inclusion in Cyberball. The Ohio State University.

- Simard, V., & Dandeneau, S. (2018). Revisiting the Cyberball inclusion condition: Fortifying fundamental needs by making participants the target of specific inclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.08.002

- Somerville, L. H., Heatherton, T. F., & Kelley, W. M. (2006). Anterior cingulate cortex responds differentially to expectancy violation and social rejection. Nature Neuroscience, 9(8), 1007–1008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1728

- Utz, S., Tanis, M., & Vermeulen, I. (2012). It is all about being popular: The effects of need for popularity on social network site use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0651

- Van Beest, I., & Williams, K. D. (2006). When inclusion costs and ostracism pays, ostracism still hurts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 918–928. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.918

- Van Beest, I., Williams, K. D., & Van Dijk, E. (2011). Cyberbomb: Effects of being ostracized from a death game. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(4), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210389084

- van Bommel, M., van Prooijen, J.-W., Elffers, H., & Van Lange, P. A. (2016). The lonely bystander: Ostracism leads to less helping in virtual bystander situations. Social Influence, 11(3), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2016.1171796

- Venturini, E., Riva, P., Serpetti, F., Romero Lauro, L., Pallavicini, F., Mantovani, F., … Parsons, T. D. (2016). A 3D virtual environment for empirical research on social pain: Enhancing fidelity and anthropomorphism in the study of feelings of ostracism inclusion and over-inclusion. Annual Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 14, 89–94.

- Weinbrecht, A., Niedeggen, M., Roepke, S., & Renneberg, B. (2018). Feeling excluded no matter what? Bias in the processing of social participation in borderline personality disorder. NeuroImage. Clinical, 19, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.04.031

- Weinbrecht, A., Niedeggen, M., Roepke, S., & Renneberg, B. (2021). Processing of increased frequency of social interaction in social anxiety disorder and borderline personality disorder. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 5489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85027-6

- White, L. O., Bornemann, B., Crowley, M. J., Sticca, F., Vrtička, P., Stadelmann, S., Otto, Y., Klein, A. M., & von Klitzing, K. (2021). Exclusion expected? Cardiac slowing upon peer exclusion links preschool parent representations to school-age peer relationships. Child Development, 92(4), 1274–1290. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13494

- White, L. O., Klein, A. M., von Klitzing, K., Graneist, A., Otto, Y., Hill, J., Over, H., Fonagy, P., & Crowley, M. J. (2016). Putting ostracism into perspective: Young children tell more mentalistic stories after exclusion, but not when anxious. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1926. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01926

- Williams, K. D. (2009). Chapter 6 ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 41, pp. 275–314). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)00406-1

- Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 748–762. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.748

- Williams, K. D., & Nida, S. A. (2011). Ostracism: Consequences and coping. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(2), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411402480

- Wolf, W., Levordashka, A., Ruff, J. R., Kraaijeveld, S., Lueckmann, J. M., & Williams, K. D. (2015). Ostracism Online: A social media ostracism paradigm. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 361–373.