Abstract

Background: Much of the literature related to mental health focuses on identifying risk factors and predictors of poor mental health. Less of the research has a health-promoting orientation, focusing on potential sources of resilience and strength.Aims: The current study contributes to the growing field of positive psychology by investigating the potential protective role of sense of coherence (SOC) in the association between COVID-19-related worries and adverse mental health outcomes.Methods: Participants were South African undergraduate students (n = 337) who completed the SOC scale, COVID-19-related worries scale, Beck hopelessness scale, Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale, and the trait scale of the state-trait anxiety inventory. We used the PROCESS macro for SPSS to examine the mediating role of SOC in the relationship between COVID-19-related worries and indices of mental health. The study was undertaking in the first and second waves of the COVID-19 disease outbreak in 2020.Results: T-test analyses found that women reported higher levels of depression and anxiety than men, and correlational analyses found a significant negative association between age and anxiety. After controlling for the confounding effects of age and gender, mediation analysis demonstrated that SOC had a direct and mediating effect on hopelessness, depression, and anxiety, suggesting that it is a potential protective resource. SOC is thus the pathway through which COVID-19-related worries impact mental health.Conclusion: Enhancing this resilience resource among vulnerable population groups can promote effective coping in the context of societal crises.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was a global traumatic stressor and associated with significant psychological distress. The restrictions implemented to curtail the disease outbreak differentially affected university students and significantly enhanced their risk of developing mental health problems. The closure of higher education campuses and the transfer of teaching and learning—as well as academic and other support services—to an online environment contributed to heightened levels of anxiety and stress, particularly for university students with limited access to digital technologies (Chen & Lucock, Citation2022). The loss of part-time employment, increased uncertainties regarding their academic trajectories, financial insecurity, concerns about their future careers, and fears of contagion further aggravated students’ psychological distress (Chu & Li, Citation2022).

Various studies have investigated the impact of the pandemic on university student mental health and the factors associated with increased susceptibility to adverse outcomes. A cross-sectional study on the mental health of students in Canada and the United Kingdom (Appleby et al., Citation2022) found that university students reported significant worries about the long-term impact of the pandemic on their academic and employment prospects. A study of university students in Bangladesh (Patwary et al., Citation2022) reported elevated levels of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic, and perceived stress among university students. Residing in a confined setting with family members and worrying about loved ones contracting the disease were factors associated with heightened distress. Furthermore, the loss of part-time work, related financial difficulties, and an inability to afford tuition fees were identified as sources of stress (Patwary et al., Citation2022). A longitudinal study of college students in the United States (Stamatis et al., Citation2022) found elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and pandemic-related stress symptoms. Perceptions of inadequate government response to the pandemic and mistrust of government were associated with higher levels of depressive symptomology. Furthermore, uncertainty regarding the course of the pandemic and related disruptions to regular routines were found to fuel anxiety.

Systematic reviews and meta-analytic studies have consolidated the evidence on the mental health outcomes associated with the pandemic among university students. For example, a systematic review of longitudinal studies of college student mental health (Buizza et al., Citation2022) reported elevated levels of mood disorders, anxiety and alcohol use. Women as well as sexual minority groups were found to have poor mental health. Y. Li et al. (Citation2021), in a systematic review and meta-analytic study of the mental health of college students concluded that the prevalence of depression and anxiety escalated during the pandemic among this population group. Elharake et al. (Citation2023) in their review of child and college student mental health during the pandemic concluded that both these groups experienced heightened levels of depression, anxiety, fatigue and general distress. Residing in a rural area, having a family with a lower socioeconomic status, and being related to or friends with a healthcare worker were significantly linked to poorer mental health outcomes. Similar results have been obtained from systematic reviews of the research on university student mental health in specific countries including Bangladesh (Al Mamun et al., Citation2021), China (Conteh et al., Citation2022) and Ethiopia (Anteneh et al., Citation2023).

The existing research has highlighted that socio-demographic factors, including gender, age, educational level, marital status, and employment are risk factors for poor mental health (Benatov et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2022). Gender has been widely studied in relation to university student mental health, with studies confirming that women reported higher levels of anxiety and depression during the pandemic (Benatov et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2022). For example, an Italian study of undergraduate students (Amerio et al., Citation2021) found that the mental health impact of the pandemic was worse for women and positively associated with caring for someone at home, worsening work performance, and poor housing quality. Similarly, the Student Experience in the Research University Consortium Survey (Amerio et al., Citation2021) of six public universities in the United States reported that major depressive disorder and GAD were more prevalent among women.

However, despite the adverse impact of the pandemic on many university students’ mental health, not all students experienced significant levels of psychological distress. Instead, many were able to adapt effectively, which underscores the role of protective factors in influencing outcomes. These factors include resilience, social support, self-efficacy, physical exercise, and a problem-solving approach (Elharake et al., Citation2023; Havnen et al., Citation2020).

For example, a study of Pakistani university students (Rasheed et al., Citation2022) found that resilience and appraisals of meaning in life were supportive of mental health. South African studies have identified social support (Padmanabhanunni et al., Citation2023) and ego resilience (Padmanabhanunni & Pretorius, Citation2022) as significant predictors of mental health. A study undertaken at a mid-Atlantic university (Haliwa et al., Citation2022) established that mindfulness was a protective resource against psychological distress.

The current study investigated sense of coherence (SOC) as a protective factor in a South African sample of university students. SOC is a concept derived from salutogenic theory and is characterized as a global orientation toward viewing one’s life as meaningful, manageable, and comprehensible (Antonovsky, Citation1993). ‘Meaningfulness’ is a motivational component and reflects appraisals that current stressors represent challenges that are worthy of one’s commitment and emotional investment. ‘Manageability’ refers to the extent to which the individual appraises themselves as having the capacities and resources (e.g., self-esteem, financial resources, family support) to cope effectively with stressors. ‘Comprehensibility’ reflects perceptions of one’s work as predictable, ordered, and consistent, as opposed to chaotic (Antonovsky, Citation1996). SOC has been viewed as an important protective factor in individual mental health (Einav & Margalit, Citation2023).

Evidence from international studies suggests that those with high SOC are able to manage stress more effectively. A cross-sectional study (Dadaczynski et al., Citation2022) of German university students, for example, reported a significant association between the dimensions of SOC and wellbeing, with the comprehensibility and meaningful dimensions of SOC identified as important predictors of wellbeing. In a study of COVID-19-related mental health across seven countries—including Israel, Italy, Spain, and Austria—Mana and colleagues (Mana et al., Citation2021) found SOC to be a central predictor of health and wellbeing. Furthermore, perceived support from family members and trust in leaders and social-political institutions were reported to mediate the relationships between SOC and mental health (Mana et al., Citation2021). An Italian study (Barni et al., Citation2020) found that SOC moderated the relationship between illness experiences (in terms of knowing persons diagnosed with COVID-19 and fear of contracting COVID-19) and psychological well-being. These authors conjectured that individuals with low levels of SOC and at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19 were more likely to experience a loss of control and to feel overwhelmed, resulting in elevated psychological distress. Interestingly, Barni et al. (Citation2020) also found that fear of contracting the disease was negatively associated with psychological well-being for individuals with higher levels of SOC. This was ascribed to the unpredictable nature of the initial disease outbreak which may have impacted on comprehensibility and manageability even for those high in SOC. Schäfer et al. (Citation2020), in a prospective study of German adults, reported that individuals who had low levels of SOC before the COVID-19 disease outbreak experienced increased psychopathological symptoms when their pre-outbreak SOC levels were taken into account. This suggests that those with lower SOC before the disease outbreak were more vulnerable to experiencing psychological distress during the outbreak. Veronese et al. (Citation2022) in a Palestinian study of health workers reported that SOC was one of the factors that mediated the association between the stress associated with COVID-19, trauma and burnout. SOC was also associated with higher levels of subjective wellbeing and post-traumatic growth among this sample, highlighting its potential protective role.

Although considerable research has been undertaken internationally on SOC among university students, comparatively less research on this topic has emerged from sub-Saharan Africa. The student population in South Africa is distinctive for several reasons. Historically, as a consequence of apartheid, the majority of black South Africans were denied quality education and economic opportunities. This legacy has meant that access to education remains a contentious issue and is inextricably linked to broader socio-economic challenges, as many students grapple with concerns such as food and housing insecurity, limited access to study materials, and transportation issues (Jackson et al., Citation2023). A significant portion of first-generation students do not view their pursuit of higher education solely as an individual endeavor. Instead, they appraise it as a pathway to uplift their families and fulfill broader obligations related to promoting their family’s social mobility (Jackson et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, many students from historically marginalized groups continue to reside in community contexts characterized by gang violence, unemployment, substance abuse, and poverty (Padmanabhanunni & Wiid, Citation2022).

According to Antonovsky (Citation1993), SOC is developed and sustained through formative life experiences and the internalization of resources. In contexts characterized by adversity, the constant negotiation of daily stressors can provide a rich, albeit challenging, environment for the development of SOC. While these adversities can, at face value, appear as inhibitors to a strong SOC, they may serve to fortify resilience, enhance adaptability, and imbue experiences with a profound sense of purpose and meaningfulness. For South African students facing these challenges, the very act of persisting in their academic pursuits amidst such adversities may sharpen their sense of comprehensibility and meaningfulness as they actively seek to understand and navigate their complex socio-economic realities.

In light of the existing literature and the distinctive socio-cultural and historical challenges faced by South African students, this study aims to explore the role of SOC as a potential buffer against psychological distress among this population group. While international research has elucidated the protective capacities of SOC, there remains a palpable gap in understanding how these dynamics play out in the South African context, particularly given the unique pressures and adversities faced by students in this setting. By investigating SOC, the study seeks to contribute nuanced insights to the broader discourse on resilience and mental health, specifically underscoring the interplay between individual resilience resources and the socio-cultural milieu.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

This study was undertaken during the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. The first case of the disease in the country was confirmed in March 2020, and the numbers escalated rapidly thereafter. The government responded with a strict lockdown, which included stringent travel restrictions, closure of non-essential businesses, and a ban on the sale of alcohol and tobacco. While these measures were taken to curb the spread of the virus, they also had significant economic implications, leading to job losses and increased economic strain on an already fragile economy. The health system faced considerable challenges, from shortages of testing kits to an overwhelmed hospital system, especially in densely populated areas. The country also grappled with the challenge of balancing the dire need for public health measures with the socioeconomic realities of a significant portion of its population living in crowded townships and informal settlements.

Participants were undergraduate students (n = 337) at an urban university in the Western Cape province of South Africa. We used a random sampling approach. The office of the registrar of the university used a random number generator to randomly select 1500 students. We used Google Forms to create an electronic version of the instruments discussed in the measures section. The link was distributed to the selected students, along with an invitation to participate. We received 337 completed forms, representing a response rate of 22.5% and a 5.2% margin of error (95% confidence interval).

The majority of the participants were female (77.2%) and lived in an urban area (75.4%). The mean age of the sample was 22 years (SD = 4.7, range = 18 to 28 years). The study was conducted during the first wave of the pandemic in South Africa (March–June 2020), and while 74.5% of the sample had not been infected during this period, 42.4% knew people who had.

Measures

Participants completed the sense of coherence scale (SOC-S; Antonovsky (Citation1987)), the COVID-19-related worries scale (COVID-19-RWS; (WHO, Citation2020), the Beck hopelessness scale (BHS; (Beck et al., Citation1974), the Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale (CES-D; (Radloff, Citation1977), and the trait scale of the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI-T; (Spielberger, Citation1985). In addition, each participant completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

The SOC-S measures the extent to which people see the world as meaningful, understandable, and manageable. This enables coping with negative experiences. The scale consists of 13 items scored on a seven-point response format. Respondents are asked to indicate how frequently they feel in a certain way, with the scale aiming to assess their enduring way of viewing life and capacity to respond to stressful situations. After taking into account the reverse scored items, the scores for all 13 items are summed to get a total score. The potential range for the SOC-13 total score is 13 to 91, with higher scores indicating a stronger sense of coherence. An example of an item on the SOC-S is ‘How often do you have the feeling that there’s little meaning in the things that you do in your daily life?’. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the SOC-S reported reliability coefficients of between.70 and.92 and concluded that the scale was a reliable and valid measure in a variety of cultural contexts (Eriksson & Lindström, Citation2005). In South Africa, satisfactory reliability coefficients have been reported for the SOC (α and ω =.81 when used with a sample of teachers (Padmanabhanunni et al., Citation2022).

The COVID-19-RWS is a subscale of the WHO COVID-19 behavioral insights tool (WHO, Citation2020) and consists of 14 items that assess worries related to COVID-19, such as concerns about health and personal loss. The COVID-19-RWS encompasses a variety of concerns related to the pandemic. It includes worries such as health concerns for oneself or loved ones, economic implications, academic delays, and implications for future employment prospects among others. The scale was devised to capture a comprehensive spectrum of the most common worries that individuals might face due to the ongoing pandemic situation. An example of an item on the COVID-19-RWS is ‘How much do you worry about your own mental health?’. Responses are given on a five-point scale that ranges from don’t worry at all (1) to worry a great deal (5). No reliability or validity data is available for the COVID-19-RWS. The scale is calculated by summing up the item scores. Higher total scores indicate greater levels of the construct being measured. The reliability of the COVID-19-RWS with the current sample is reported in the results section.

The BHS is a 20-item measure of hopelessness and pessimism about the future. An example of an item on the BHS is ‘I can’t imagine what my life would be like in 10 years.’ The BHS uses a dichotomous true/false response format. The authors reported a satisfactory reliability coefficient (α = .93) for the scale, and the relationship between the BHS and clinical ratings of hopelessness provided evidence for the validity of the scale (Beck et al., Citation1974). In South Africa, reliability coefficients of .89 (α and ω) were reported for the BHS with a sample of schoolteachers (Padmanabhanunni, Pretorius, et al., Citation2022).

The CES-D is a 20-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. An example of an item on the CES-D is ‘I felt that I could not shake of the blues even with the help of my family/friends.’ Responses to the items of the CES-D are given on a four-point scale ranging from rarely or none of the time (0) to most or all of the time (3). A review of the CES-D in 2004 found that it had been used in more than 800 studies and its reliability with samples from the general population typically ranged between .80 and.90 (Eaton et al., Citation2004). In South Africa, reliability coefficients of .90 and .92 were reported for a student (Pretorius, Citation1991) and a teacher sample (Pretorius & Padmanabhanunni, Citation2022b), respectively.

The STAI-T is a 20-item measure of trait anxiety or the tendency to feel stressed and anxious in a wide variety of situations. An example of an item on the STAI-T is ‘I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter.’ Responses are given on a four-point rating scale ranging from almost never (1) to almost always (4). A reliability generalization study found that the alpha coefficients ranged between .87 and .93 across 25 studies (Guillén-Riquelme & Buela-Casal, Citation2014). In South Africa, reliability coefficients of .91 (α and ω) were reported for the STAI-T in a teacher sample (Pretorius & Padmanabhanunni, Citation2022a).

Data analysis

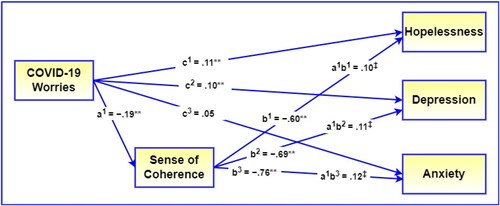

IBM SPSS for Windows, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was used for the analysis. We obtained descriptive statistics (indices of kurtosis and skewness, as well as means and standard deviations), reliability of all scales with the current sample (alpha and omega), and the intercorrelations between variables (Pearson r). To examine the mediating role of sense of coherence in the relationship between COVID-19-related worries and indices of mental health, we used the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2017) for SPSS. COVID-19-related worries were the independent variable, the indices of mental health (depression, anxiety, and hopelessness) the dependent variables, and sense of coherence the mediating variable (see ). The significance of the indirect effects was evaluated using bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1. Illustration of the mediating role of Sense of Coherence.

Note. c1–c3 = direct effects of predictor on dependent variables, a1 = direct effect of predictor on mediator, b1–b3 = direct effects of mediator on dependent variables, a1b1, a1b2, a1b3 mediating effects. All regression coefficients are standardized.

**p < .01, ***p < .001, ‡95% CI.

Results

The descriptive statistics, indices of kurtosis and skewness, reliability coefficients, and intercorrelations between study variables are presented in .

Table 1. Intercorrelations, descriptive statistics and reliability of study variables.

The indices of kurtosis (−.95 to .95) and skewness (−.35 to 1.24) fall within the acceptable range of −7 to +7 for kurtosis and −2 to +2 for skewness (Hair et al., Citation2010), indicating no marked departure from normality. The internal consistency estimates for all the scales (α =.81 to .92; ω = .82 to .92) were satisfactory and exceed the conventional cut-off of >.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994).

also indicates that sense of coherence was significantly negatively correlated with COVID-19-related worries (r = −.17, p = .002, low association), hopelessness (r = −.57, p <.001, substantial association), depression (r = −.71, p <.001, very strong association), and anxiety (r = −.77, p <.001, very strong association). COVID-19-related worries were significantly positively associated with depression (r = .22, p <.001, low association) and anxiety (r = .17, p = .002, low association). Thus, high levels of COVID-19-related worries were associated with high levels of anxiety and depression, while high levels of sense of coherence were associated with low levels of COVID-19-related worries, hopelessness, depression, and anxiety.

There were significant gender differences between some of the outcome variables. Women reported higher levels of depression (M = 28.5, SD = 13.2) and anxiety (M = 48.90, SD = 10.3) than men (depression: M = 23.3, SD = 12.9, t = 3.00, p = .001; anxiety: M = 44.5, SD = 10.3, t = 3.28, p <.001). There was also a significant negative association between age and anxiety (r = −.11, p = .049). Gender and age were consequently added as covariates in the mediation analysis. Rural respondents reported higher levels of depression (M = 29.40, SD = 12.66), hopelessness (M = 4.77, SD = 3.54), and anxiety (M = 49.27, SD = 9.30) than urban respondents (depression: M = 26.83, SD = 13.57; hopelessness (M = 4.63, SD = 4.60); anxiety: M = 47.59, SD = 10.77) but these differences were not statistically significant (depression: t = 1.50, p = .134; hopelessness: t = 0.24, p = .808; anxiety: t = 1.26, p = .208).

The direct and mediating effects of sense of coherence, obtained with the mediation analysis, are presented in .

Table 2. The mediating role of sense of coherence in the relationship between COVID-19-related worries and indices of mental health.

indicates significant direct effects of sense of coherence on hopelessness (β = −.598, p <.001), depression (β = −.69, p <.001), and anxiety (β = −.76, p <.001). , furthermore, indicates that the mediating effects of sense of coherence on hopelessness (β = .096, 95% CI [.013, .067]), depression (β = .111, 95% CI [.047, .231]), and anxiety (β = .121, 95% CI [.042, .199]) were also significant. The mediation model is visually presented in .

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on mental health and wellbeing globally. The stressors associated with the disease outbreak and its mitigation measures have caused a range of worries (e.g. about the health and safety of loved ones). For university students, these worries may relate to the possibility of contracting and spreading the disease and unknowingly infecting others, as well as one’s academic trajectory, financial concerns, and career. There is significant variability in responses to the pandemic, suggesting that protective factors are involved in mental health outcomes. The current study investigated the potential protective role of SOC in the association between COVID-19-related worries and mental health outcomes. There were several important findings.

First, high levels of COVID-19-related worries were associated with high levels of anxiety and depression. This finding corresponds to those of previous studies. For example, Wilson and colleagues (Wilson et al., Citation2021) report that COVID-19-related worries about contracting the disease were associated with high anxiety among young adults but not among those who were older. This was attributed to young adults not having developed sufficient emotional regulation skills and a range of coping strategies to draw on to manage stressors. Similarly, Barzilay and colleagues (Barzilay et al., Citation2020) report that COVID-19-related worries were significantly associated with heightened generalized anxiety disorder and depression among a diverse sample of academics, students, and healthcare workers. A study of Swiss university students (Elmer et al., Citation2020) found that worries about family and friends, career path, as well as social isolation, and lack of interaction were associated with greater anxiety and depression.

Second, high levels of SOC were associated with low levels of COVID-19-related worries, hopelessness, depression, and anxiety. This finding lends further support to empirical studies reporting positive relationships between SOC and indices of mental health and wellbeing. For example, Li and colleagues (Li et al., Citation2021) report that SOC had a protective role in college student mental health in China following the re-opening of tertiary education institutions. SOC predicted lower levels of student depression, anxiety, and stress. It is probable that individuals with higher SOC are more likely to view COVID-19 mitigation measures as reasonable and to appraise stressors as challenges that they can overcome. They are also better able to draw on internal resources and external support for coping, and this can positively affect their mental health and wellbeing (Li et al., Citation2021).

Third, there were significant gender differences in mental health outcomes, with women reporting higher levels of depression and anxiety than men. Studies undertaken during the pandemic have suggested that women and those who identify as non-binary experienced greater levels of depression and anxiety than men (Amerio et al., Citation2021; Herrera-Añazco et al., Citation2022). These differences have been attributed to women perceiving the COVID-19 pandemic as having a greater threat to their personal health and the wellbeing of significant others. However, certain studies (Cénat et al., Citation2021; Verma & Mishra, Citation2020) report that men experienced more anxiety symptoms than women. Some researchers (Metin et al., Citation2022) have underscored the need for caution in interpretations of gender differences in mental health, as these variations can arise from an overrepresentation of women in particular samples and from moderating factors such as age and culture.

Within the South African context, cultural perspectives on health, illness, and coping can influence how individuals perceive threats like the COVID-19 pandemic and the strategies they employ to manage their emotions. For example, Schmit and colleagues (Schmidt et al., Citation2020) in a South African study, reported that cultural misconceptions including beliefs that people of higher socio-economic status were more vulnerable to contracting the virus owing to their greater physical mobility (e.g. overseas travel) and potentially contributed to certain groups not adhering to preventative measures. When cultural beliefs suggest that certain segments of the population are less at risk, this might influence appraisals or comprehensibility regarding the threat. If COVID-19 is perceived as a disease primarily affecting those of higher socio-economic status, individuals outside of that bracket might feel the threat is less applicable to them, potentially undermining the manageability aspect of SOC. The motivation to cope (i.e. meaningfulness component of SOC), may also be affected if individuals feel detached or distant from the perceived threat. While cultural factors undoubtedly play a role in shaping responses to global health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, our study did not explicitly focus on these aspects. As a result, it is not possible to make firm conclusions about the role of culture in SOC amongst this sample.

Finally, SOC had a direct and mediating effect on hopelessness, depression, and anxiety, suggesting that it is a protective resource. This finding lends further support to research demonstrating that SOC is a factor underlying resilience and effective coping (Mc Gee et al., Citation2018; Veronese et al., Citation2021). Those with higher levels of SOC are likely to appraise and experience COVID-19-related stressors as explicable, to have a sense of confidence in their ability to cope effectively, and be motivated to address stressful events. In contrast, those low in SOC are more likely to experience stressors as overwhelming and inexplicable and to doubt their capacity to cope (Padmanabhanunni et al., Citation2022). These types of appraisals can then evoke a sense of dejection and hopelessness and produce psychological distress (Padmanabhanunni et al., Citation2022).

Implications of the study

The findings of this study underscore the significance of SOC as a central factor in shaping the mental well-being of university students during unprecedented global challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic. The protective role of SOC goes beyond merely serving as a buffer; it emerges as a foundational element in constructing resilient mental frameworks that can withstand stressors. Given that high SOC levels are associated with lower levels of COVID-19-related worries and better mental health outcomes, there is a clear imperative for educational institutions to devise strategies that nurture and bolster this resource among students. Universities could consider integrating resilience-building modules within their curriculums or offering workshops that emphasize the development of a strong SOC. Strengthening generalized resistance resources, such as self-efficacy beliefs and problem orientation, can be achieved through evidence-based therapeutic interventions (Super et al., Citation2016). Mindfulness-based approaches, for instance, can help students become more aware of their responses to stressors, allowing them to manage their reactions more effectively. Meanwhile, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy can aid in challenging and reframing negative thought patterns that might undermine their SOC. Furthermore, interventions such as ‘goal mapping’, which centers on proactive planning and visualization, emerge as promising tools to further bolster SOC among students (Davidson et al., Citation2012).

This study had several limitations. First, although it used established, validated instruments, the self-report format of these questionnaires could result in responses being influenced by social-desirability and selection bias. The cross-sectional nature of the study and the sample being students enrolled at the same institution also limit the generalizability of the results. Thus, the research design does not permit firm inferences on the temporal relationship between variables. Furthermore, limited information is available on the mental health status of the participants before the COVID-19 outbreak. The majority of the sample were women, and future research using a more even gender distribution is recommended to confirm the results. It is also probable that factors apart from COVID-19 had affected student mental health during the period, and additional research would be needed to disentangle these effects.

Conclusion

The current study investigated whether SOC serves as a protective factor in the relationship between COVID-19-related worries and indices of psychological distress. The findings suggest that higher SOC is associated with reduced psychological distress and lower levels of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness. In addition, SOC serves as a buffer in the association between COVID-19-related worries and adverse mental health outcomes. These findings suggest that SOC is a potential resilience resource and that interventions aimed at enhancing meaningfulness, comprehension, and manageability could promote wellbeing. The study underscores the importance of nurturing SOC in university students, as it offers a tangible pathway for reducing pandemic-induced distress and fostering psychological resilience in the face of global health crises.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Humanities and Social Sciences Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape (ethics reference number: HS21/3/8). Participants provided informed consent, and participation was voluntary. Participants were also provided with the contact details of the South African Anxiety and Depression Group and the Centre for Student Support Services. All participants were encouraged to make use of these services if they experienced any distress while completing the questionnaires.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anita Padmanabhanunni

Anita Padmanabhanunni (PhD) is a Professor of Psychology and her research focus includes mental health, trauma, P T SD and resilience.

Serena Ann Isaacs

Serena Ann Isaacs (PhD) is an Associate Professor and her research interests include family and community resilience and student well-being.

Tyrone B. Pretorius

Tyrone B. Pretorius (PhD) is a Professor of Psychology and his research focus includes protective factors in mental health and instrument validation.

References

- Al Mamun, F., Hosen, I., Misti, J. M., Kaggwa, M. M., & Mamun, M. A. (2021). mental disorders of bangladeshi students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S315961

- Amerio, A., Bertuccio, P., Santi, F., Bianchi, D., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Odone, A., Costanza, A., Signorelli, C., Aguglia, A., Serafini, G., Capolongo, S., & Amore, M. (2021). Gender differences in COVID-19 lockdown impact on mental health of undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 813130–813130. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.813130

- Anteneh, R. M., Dessie, A. M., Azanaw, M. M., Anley, D. T., Melese, B. D., Feleke, S. F., Abebe, T. G., & Muche, A. A. (2023). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors among college and university students in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2022. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1136031–1136031. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1136031

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass.

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 36(6), 725–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z (Social Science & Medicine)

- Antonovsky, A. (1996). The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 11(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/11.1.11

- Appleby, J. A., King, N., Saunders, K. E., Bast, A., Rivera, D., Byun, J., Cunningham, S., Khera, C., & Duffy, A. C. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the experience and mental health of university students studying in Canada and the UK: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 12(1), e050187-e050187. (Original research) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050187

- Barni, D., Danioni, F., Canzi, E., Ferrari, L., Ranieri, S., Lanz, M., Iafrate, R., Regalia, C., & Rosnati, R. (2020). Facing the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of sense of coherence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 578440–578440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.578440

- Barzilay, R., Moore, T. M., Greenberg, D. M., DiDomenico, G. E., Brown, L. A., White, L. K., Gur, R. C., & Gur, R. E. (2020). Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), 291–291. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4

- Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037562

- Benatov, J., Ochnik, D., Rogowska, A. M., Arzenšek, A., & Mars Bitenc, U. (2022). Prevalence and sociodemographic predictors of mental health in a representative sample of young adults from Germany, Israel, Poland, and Slovenia: A longitudinal study during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031334

- Buizza, C., Bazzoli, L., & Ghilardi, A. (2022). Changes in college students mental health and lifestyle during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Adolescent Research Review, 7(4), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00192-7

- Cénat, J. M., Blais-Rochette, C., Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Noorishad, P.-G., Mukunzi, J. N., McIntee, S.-E., Dalexis, R. D., Goulet, M.-A., & Labelle, P. R. (2021). Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113599–113599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599

- Chen, T., & Lucock, M. (2022). The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey in the UK. PLOS One, 17(1), e0262562-e0262562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262562

- Chu, Y.-H., & Li, Y.-C. (2022). The impact of online learning on physical and mental health in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052966

- Conteh, I., Yan, J., Dovi, K. S., Bajinka, O., Massey, I. Y., & Turay, B. (2022). Prevalence and associated influential factors of mental health problems among Chinese college students during different stages of COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research Communications, 2(4), 100082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psycom.2022.100082

- Dadaczynski, K., Okan, O., Messer, M., & Rathmann, K. (2022). University students’ sense of coherence, future worries and mental health: Findings from the German COVID-HL-survey. Health Promotion International, 37(1), daab070. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab070

- Davidson, O. B., Feldman, D. B., & Margalit, M. (2012). A focused intervention for 1st-year college students: Promoting hope, sense of coherence, and self-efficacy. The Journal of Psychology, 146(3), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.634862

- Eaton, W. W., Muntaner, C., Smith, C., Tien, A., & Ybarra, M. (2004). Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: Review and revision. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. (pp. 363–377). Routledge.

- Einav, M., & Margalit, M. (2023). Loneliness before and after COVID-19: Sense of coherence and hope as coping mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105840

- Elharake, J. A., Akbar, F., Malik, A. A., Gilliam, W., & Omer, S. B. (2023). Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 54(3), 913–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1

- Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLOS One, 15(7), e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

- Eriksson, M., & Lindström, B. (2005). Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(6), 460–466. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.018085

- Guillén-Riquelme, A., & Buela-Casal, G. (2014). Meta-analysis of group comparison and meta-analysis of reliability generalization of the state-trait anxiety inventory questionnaire (STAI). Revista Espanola de Salud Publica, 88(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1135-57272014000100007

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Haliwa, I., Spalding, R., Smith, K., Chappell, A., & Strough, J. (2022). Risk and protective factors for college students’ psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 70(8), 2257–2261. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1863413

- Havnen, A., Anyan, F., Hjemdal, O., Solem, S., Gurigard Riksfjord, M., & Hagen, K. (2020). Resilience moderates negative outcome from stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated-mediation approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186461

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Herrera-Añazco, P., Urrunaga-Pastor, D., Benites-Zapata, V. A., Bendezu-Quispe, G., Toro-Huamanchumo, C. J., & Hernandez, A. V. (2022). Gender differences in depressive and anxiety symptoms during the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Latin America and the Caribbean. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 727034–727034. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.727034

- Jackson, K., Faroa, B. D., Augustyn, N. A., & Padmanabhanunni, A. (2023). What motivates South African students to attend university? A cross-sectional study on motivational orientation. South African Journal of Psychology, 53(4), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463231196297

- Li, M., Xu, Z., He, X., Zhang, J., Song, R., Duan, W., Liu, T., & Yang, H. (2021). Sense of coherence and mental health in college students after returning to school during COVID-19: The moderating role of media exposure. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 687928–687928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.687928

- Li, Y., Wang, A., Wu, Y., Han, N., & Huang, H. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669119–669119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669119

- Liu, Y., Frazier, P. A., Porta, C. M., & Lust, K. (2022). Mental health of US undergraduate and graduate students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences across sociodemographic groups. Psychiatry Research, 309, 114428–114428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114428

- Mana, A., Bauer, G. F., Meier Magistretti, C., Sardu, C., Juvinyà-Canal, D., Hardy, L. J., Catz, O., Tušl, M., & Sagy, S. (2021). Order out of chaos: Sense of coherence and the mediating role of coping resources in explaining mental health during COVID-19 in 7 countries. SSM. Mental Health, 1, 100001–100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100001

- Mc Gee, S. L., Höltge, J., Maercker, A., & Thoma, M. V. (2018). Sense of coherence and stress-related resilience: Investigating the mediating and moderating mechanisms in the development of resilience following stress or adversity. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 378–378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00378

- Metin, A., Erbiçer, E. S., Şen, S., & Çetinkaya, A. (2022). Gender and COVID-19 related fear and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 310, 384–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.036

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory. McGraw Hill.

- Padmanabhanunni, A., Isaacs, S., Pretorius, T., & Faroa, B,. (2022). Generalized resistance resources in the time of COVID-19: The role of sense of coherence and resilience in the relationship between COVID-19 fear and loneliness among schoolteachers. OBM Neurobiology, 6(3), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2203130

- Padmanabhanunni, A., & Pretorius, T. B. (2022). Promoting well-being in the face of a pandemic: the role of sense of coherence and ego-resilience in the relationship between psychological distress and life satisfaction. South African Journal of Psychology = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif jVir Sielkunde, 53(1), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463221113671

- Padmanabhanunni, A., Pretorius, T. B., & Isaacs, S. A. (2023). We are not islands: The role of social support in the relationship between perceived stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and psychological distress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043179

- Padmanabhanunni, A., Pretorius, T. B., Stiegler, N., & Bouchard, J.-P. (2022). A serial model of the interrelationship between perceived vulnerability to disease, fear of COVID-19, and psychological distress among teachers in South Africa. Annales Medico-Psychologiques, 180(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2021.11.007

- Padmanabhanunni, A., & Wiid, C. (2022). From fear to fortitude: Differential vulnerability to PTSD among South African university students. Traumatology, 28(1), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000312

- Patwary, M. M., Bardhan, M., Disha, A. S., Kabir, M. P., Hossain, M. R., Alam, M. A., Haque, M. Z., Billah, S. M., Browning, M. H. E. M., Kabir, R., Swed, S., & Shoib, S. (2022). Mental health status of university students and working professionals during the early stage of COVID-19 in Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116834

- Pretorius, T. B. (1991). Cross-cultural application of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale: A study of black South African students. Psychological Reports, 69(3 Pt 2), 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3f.1179

- Pretorius, T. B., & Padmanabhanunni, A. (2022a). The beneficial effects of professional identity: The mediating role of teaching identification in the relationship between role stress and psychological distress during the Covid-19 pandemic. In. MDPI.

- Pretorius, T. B., & Padmanabhanunni, A. (2022b). Validation of the connor-davidson resilience scale-10 in South Africa: Item response theory and classical test theory. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1235–1245. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S365112

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Rasheed, N., Fatima, I., & Tariq, O. (2022). University students’ mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of resilience between meaning in life and mental well-being. Acta Psychologica, 227, 103618–103618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103618

- Schäfer, S. K., Sopp, M. R., Schanz, C. G., Staginnus, M., Göritz, A. S., & Michael, T. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on public mental health and the buffering effect of a sense of coherence. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89(6), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510752

- Schmidt, T., Cloete, A., Davids, A., Makola, L., Zondi, N., & Jantjies, M. (2020). Myths, misconceptions, othering and stigmatizing responses to Covid-19 in South Africa: A rapid qualitative assessment. PLOS One, 15(12), e0244420-e0244420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244420

- Spielberger, C. D. (1985). Assessment of state and trait anxiety: Conceptual and methodological issues. Southern Psychologist, 2(4), 6–16. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-55057-001

- Stamatis, C. A., Broos, H. C., Hudiburgh, S. E., Dale, S. K., & Timpano, K. R. (2022). A longitudinal investigation of COVID-19 pandemic experiences and mental health among university students. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12351

- Super, S., Wagemakers, M. A. E., Picavet, H. S. J., Verkooijen, K. T., & Koelen, M. A. (2016). Strengthening sense of coherence: Opportunities for theory building in health promotion. Health Promotion International, 31(4), 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav071

- Verma, S., & Mishra, A. (2020). Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(8), 756–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020934508

- Veronese, G., Dhaouadi, Y., & Afana, A. (2021). Rethinking sense of coherence: Perceptions of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness in a group of Palestinian health care providers operating in the West Bank and Israel. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520941386

- Veronese, G., Mahamid, F. A., & Bdier, D. (2022). Subjective well-being, sense of coherence, and posttraumatic growth mediate the association between COVID-19 stress, trauma, and burnout among Palestinian health-care providers. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 92(3), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000606

- WHO. (2020). Survey Tool and Guidance: Behavioural Insights on COVID-19, 17 April 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Wilson, J. M., Lee, J., & Shook, N. J. (2021). COVID-19 worries and mental health: the moderating effect of age. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1856778