Abstract

African rural transformation aimed to shift from agricultural domination livelihood to diversified economic activities like industries and services. However, factors like political instability, corruption, lack of finance, lack of political commitment, low technology, and others stagnated the transformation. Although most African countries’ rural transformation is ambitious, some tried their best to realize it. This article scrutinizes the African rural livelihood system and rural transformation focusing on Mauritius. We used a qualitative explanatory approach to study the research. We also used secondary data sources to enrich the title. The findings of this paper reveal that Mauritius has invested much to realize the transformation by setting different policies and taking measures to increase the share of services in the national GDP and decrease the agricultural share in the GDP. Mauritius established the Rural Development Unit that operated under the Ministry of Economic Planning to improve the rural people’s quality with the help of the World Bank. Besides, the government incorporated the Arsenal Litchis Project, the Riche Terre Cooperative project, credit loan facilities access, IFAD funds accessibilities, and the small entrepreneurs’ programs formations to accelerate the transformation. It concludes that the country has achieved remarkable rural transformation that can be a model for other African countries. It recommends that other African countries, where agriculture is the leading economic system should create platforms like lasting political stability and design inclusive and research-oriented policies, programs, and strategies to realize rural transformation.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Different scholars conceptualize rural transformation differently. Thus, there is no single universally acceptable definition. Quoting NEPAD, Gardner & Hay (Citation2016) define rural transformation as a holistic societal alteration where rural societies decline to depend on agriculture. They also assert that rural societies diversify the sources of the economy. It is a process where rural societies shift from rural livelihood to urban and city ways of life by exchanging goods, services, and ideas in the market. To realize this, rural societies rely on market information (Berdegué et al., Citation2013; Gardner & Hay, Citation2016). Also, the society becomes culturally more similar to large urban agglomerations (Berdegué et al., Citation2013). Rural transformation enhances the rural peoples’ livelihood security by adding necessary value to natural resources (UNIDO, Citation2013).

In the same manner, rural transformation is inevitable because of economic and social drivers (Gardner & Hay, Citation2016). Being a center of rural transformation, agriculture is determined by population growth, market connectivity, and agroecological endowment and potential (Tittonell, Citation2014). Agricultural transformation is a change from a traditional structure to a modernization by enhancing production and using improved inputs and technologies. It also needs to set appropriate policies that support the transformation (Delgado, Citation1995). Particularly, land is a fundamental element in rural transformation (Muyanga & Jayne, Citation2014; Waeterloos & Cockburn, Citation2017).

However, the inadequacy of infrastructure and institutional structure, corruption, less irrigation practice, and political instability affect African rural transformation (Mellor, Citation2014). Further, colonial history (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Houssou et al., Citation2018), weak technology, and the inability of the society to learn new technology stagnate African rural transformation (Houssou et al., Citation2018). Besides, the inadequacy of financial services and insurance, the low level of research and extension, and the underestimation of the role of agriculture in economic development affect African rural transformation (Wiggins, Citation2014). Furthermore, lack of competition, low saving habits, high unemployment rate, and inadequate skills are the major factors that hinder the African rural transformation. Similarly, African rural areas are known for food insecurity, unemployment and migration, and water scarcity (Boto et al., Citation2012). Generally, the entire livelihoods of rural communities depend on sparse and disorganized agricultural food crops, fishery, pastoralism, and ancillary activities that link to rural townships (UNIDO, Citation2013).

Since colonization, African rural communities have faced different challenges because of external interference in agriculture activities, especially, political interference. So far, development policies have never addressed the fundamental problems of African rural communities (Daka & Tamira, Citation2019). Africa has not diversified its non-farm economy to reduce land pressure yet (Headey & Jayne, Citation2014). The policies highly depend on the Eurocentric assumptions that do not consider the African ability, capacity, knowledge, and skills to perform (Daka & Tamira, Citation2019). Thus, donors manipulate social policies based on their interests (Adesina, Citation2020; Booth & Golooba-Mutebi, Citation2014).

By the same token, the African development policies do not relate to the actual problems on the ground. African rural development scientific research did not produce skilled and experienced scholars in the area. Bureaucrats and politicians who have never conducted scientific research participated in policymaking that hindered African rural transformation (Daka & Tamira, Citation2019). On the other hand, the rural transformation has gotten the attention of scholars because the joint development of agricultural, industrial, and service activities is paramount to diversifying the economy. Also, it creates extensive opportunities in ICT, tourism, bio-technologies, environment protection, and renewable energy generation (Houngbo, Citation2014).

The paper focuses on Mauritius’s rural transformation and livelihood system as a case study because Mauritius has achieved rural development. The Country established the Rural Development Unit, which operated under the Ministry of Economic Planning to improve the rural peoples’ quality with the help of the World Bank (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Also, the government incorporated the Arsenal Litchis Project, the Riche Terre Cooperative project, credit loan facilities access, IFAD funds accessibilities, and the small entrepreneurs’ programs formations to accelerate the transformation (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018). As a result, Mauritius’ rural community is characterized by different social services such as clean water, access to free education, free transport for students, and free health (AfDB, Citation2022; Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Kalumiya, Citation2018). The main objective of this paper is to scrutinize the Mauritius rural livelihoods and transformations i.e., structural transformation, drivers of transformation, and policies that have facilitated the transformation. Furthermore, we concluded the paper by targeting the implications for other African countries. However, the paper is limited to document review. It attempted to explore the rural transformation of Mauritius which could be a model for other African countries in rural transformation by diversifying income sources.

Finally, we used the explanatory qualitative approach to scrutinize African rural livelihood and transformation by taking Mauritius as a case study. The qualitative approach enables the researcher to study a deeper understanding of social and cultural phenomena (Kothari, Citation2004). Further, it is widely used to interpret the natural setting as it is (Creswell, Citation2014). We reviewed secondary sources to enrich the title—definition of rural transformation, drivers of African rural transformation, reasons for African rural transformation, Mauritius rural transformation, and structural change. Accordingly, we reviewed different journal articles, books, research conferences, proceedings, policies, and reports of Mauritius, and dissertations that related to the research title. Further, we reviewed the Mauritius development plans and policies starting from 1968 to 2021/2022 to triangulate with other reports.

2. Theoretical framework

Scholars in development and rural transformation use different theories to stipulate rural transformation. Modernization theory, dependency theory, post-development theory, and post-colonial theory are the major theories that are used in rural transformation.

Modernization theory deals with social growth and societal development (Goorha, Citation2017). It came after the Second World War (Martinez, Citation2015) in the 1950s (Gwynne, Citation2009; Power, Citation2023). It illustrates that developing countries have to follow the Western development path to be transformed—change in social, political, cultural, and political aspects (Power, Citation2023; Romaniuk & Joseph, Citation2017). It aims to launch a policy that supports third-world countries’ economic and social change (Gwynne, Citation2009). Also, it assumes development as similar ways of shifting from an agrarian-based economy and rural livelihoods to industrial patterns and urban agglomeration. As a result, all societies should follow straight paths like Rostow’s stage of development as a modernization sign. To realize this, internal challenges such as education, market, and political cultures that stagnate development should be changed to the Western styles (Ynalvez & Shrum, Citation2015). Consequently, the central argument of the theory is political culture, societal change, and economic development coexistence and coherence (Inglehart, Citation2001). Later on, it has gotten different criticisms from different scholars. Ynalvez and Shrum (Citation2015) argue that the modernization proponents undermine the inconsistency of technology with local knowledge.

On the other hand, developing countries created dependency theory in response to the modernization theory (Romaniuk & Joseph, Citation2017; Martinez, Citation2015). The theory emerged in the early 1960s (Romaniuk & Joseph, Citation2017). It focuses on external challenges of underdevelopment of third world countries. The proponents argue that the least developed countries export raw materials to the developed nations at a low cost, but in return, they import processed goods at a high price. Westerners import technology to developing countries and conduct research for their own interests, not for the benefit of the least developing countries (Shrum, Citation2001). Romaniuk and Joseph (Citation2017) posit that dependency theory has three main features. These are the dominant and dependent states of the world system, accountability of external forces for the economic decline of the third-world countries, and unbalanced relationships between the developed and developing countries (Romaniuk & Joseph, Citation2017).

According to the dependency theory, the world system is divided into two: the dominant core, the north, and the dependent periphery, the south. Further, in a global economy, according to the theory, states perpetrate center of center (USA, UK), the periphery of center (Canada, Japan), the center of the periphery (South Africa, India), and the periphery of the periphery (all the least developed countries like Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe) (Romaniuk & Joseph, Citation2017).

A post-development theory was introduced in 1990 by critics of the development concepts as failed (Matthews, Citation2010). Further, it “Questioned the foundations of development theory and policy” (Ziai, Citation2014, p. 2). Although the concept of post-development came to exist in 1980, it was widely used in the 1990s by Illich, Foucault, and Escobar (Ziai, Citation2014). Also, it is the most influential theory of the 21st century (Sharma, Citation2020). The post-development proponents are looking for alternatives to development (Klein & Morreo, Citation2019; Matthews, Citation2004). They reawaken that it centered on ensuring social justice and freedom from restraints (Mckinnon, Citation2007).

Besides, it tried to expose the areas where development theories failed (Klein & Morreo, Citation2019). It questioned that underdevelopment was because of the hegemonic dominance of the West and unequal exchange of the South with the North. Hence development is socially constructed to maintain the hegemony of Western countries. Unlike modernization and other theories, post-development theory accommodates and respects cultural differences. The proponents argue that the West purposively undermines local knowledge by labeling it backward. That was why development did not come to exist and could not be realized overnight across the globe (Sharma, Citation2020). However, most scholars criticized post-development theory as it could not use inappropriate methods to refute development. The proponents could not recognize that development was a gradual change in lifespan (Matthews, Citation2010).

Another rural transformation theory is the post-colonial theory. The theory showed that though Africa was liberated from the European countries physically, it was not free from their ideological influences. That means neoliberal economic ideas were consolidated and institutionalized by the IMF and World Bank to privatize and liberalize African policies. However, it resulted in an economic crisis in the 1980s and 1990s when Africans attempted to implement the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) (Yilmaz & Enwere, Citation2018). “The transition from colonialism to political independence also marked the transition from the use of colonial terrorism to the use of modernization ideas as the least expensive instrument to control Africa, its resources and peoples” (Yilmaz & Enwere, Citation2018, pp. 52).

Arguably, postcolonial theory is both fiction and pernicious (Hitchcock, Citation1997). Postcolonial theory depended on the ideas of the decolonization movement though it indicated a crisis in knowledge imposed during the classic colonial empire. It was the new brand of new interest in colonial rule (ibid). Theoretically, postcolonial theory relates to the demise of colonialism that aims to emancipation from all dimensions of subjugation. However, it is a legacy of colonialism practically (Arora, Citation2020). The authors use postcolonial theory to examine African rural transformation and livelihood system focusing on Mauritius because it helps us to compare the Country’s entire development during the colony and after its independence.

3. Rural transformation

3.1. Basic concept of rural transformation

Before discussing the Mauritius rural transformation experience, it is visible if we define the concept of rural transformation first. Gardner and Hay (Citation2016) add that it is better to observe prudently the alteration of farmland size and distribution across the globe to understand rural transformation. Scholars define rural transformation differently, and hence there is no single definition that stipulates rural transformation. Rural transformation enhances rural peoples’ livelihood security by adding necessary value to natural resources (UNIDO, Citation2013). Quoting NEPAD, Gardner and Hay (Citation2016) define rural transformation as a holistic societal alteration where rural societies decline to depend on agriculture since they diversify the sources of the economy. Also, it is a process where rural people shift from rural livelihood to urban and city ways of life by exchanging goods, services, and ideas in the market. They rely on market information to realize it (Berdegué et al., Citation2013; Gardner & Hay, Citation2016). Besides, the society becomes culturally more similar to large urban agglomerations (Berdegué et al., Citation2013). The central themes of rural transformation for both Gardner and Hay and Berdegué et al. are the use of other economic activities such as trade, tourism, etc., as a means of job and income instead of agriculture. Similarly, rural societies enjoy a livelihood equal to urban life. Furthermore, they are connected to the market to exchange goods and services.

3.2. Indicators of rural transformation

Rural transformation deals with social, economic, and cultural change (Gardner & Hay, Citation2016; Phiri, Citation2019), and political and spatial settings (Phiri, Citation2019). It relates to diversifying rural livelihood strategies (Tittonell, Citation2014). Particularly, intensification farming is a core input for rural transformation (Houssou et al., Citation2018). Rural transformation needs to realign policies, and finances, and support social movements and innovations (Zougmoré et al., Citation2021). Further, it requires empowering local people at the center of decision-making. To realize rural transformation, we need to incorporate the research based planning, managing, and financing mechanisms (Ngah, Citation2012).

Generally speaking, rural transformation creates a space where rural people can live a similar life to urban people’s living style by disappearing rural society (Berdegué et al., Citation2013). African agriculture has to produce more products both for food and the market. Gradually, development can be achieved if one can invest less in agriculture but more in industries and services since the role of agriculture in the GDP economy will be replaced by non-agricultural sectors (Delgado, Citation1995).

3.3. Reasons for African rural transformation

African leaders should focus on rural investment because two-thirds of the population lives in rural areas. In sub-Saharan Africa, agriculture accounts for 65% of jobs (Boto et al., Citation2012; Houngbo, Citation2014). Thus, enhancing agricultural productivity realizes rural transformation (Houngbo, Citation2014). Further, most African youths presume rural as a backward area where they cannot get a job (Houngbo, Citation2014). Additionally, rural realms are featured by inadequate enterprise creation and financial services and poor provision of social protection and infrastructure (Boto et al., Citation2012). As a result, to bring rural transformation development, we have to readjust the mindset of youths (Ngah, Citation2012). Besides, agriculture shares 75% of export items in the least developed African countries. However, rural people get fewer facilities and benefits compared to urban people (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Thus, there are no options to realize development without rural transformation (Delgado, Citation1995). The main goal of rural transformation is to raise rural inhabitants’ social, economic, and political rights (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). In a nutshell, Africa has to realize rural transformation to be self-reliant, produce surplus products that are used as input for industries, and improve the welfare of its people.

3.4. Drivers of African rural transformation

Different drivers that affect African rural transformation are global context, rapid urbanization, global food production, and land reform policy. The primary driver of rural transformation is the global context (Berdegué et al., Citation2013). They further argue that:

Rural transformation is driven by factors that are active across the globe because, firstly, the diversification of rural economies away from almost complete reliance on agriculture. Secondly, the progressive globalization of agrifood systems transforms the economic base of the rural economy and the livelihood strategies of individuals and households as well as the conditions under which they and rural organizations, communities, and firms engage with the economic processes of their own country and beyond. Finally, the urbanization of rural regions reduces and eventually eliminates the relative isolation in which rural people have lived for centuries (p: 12).

In conclusion, OECD (nd) identifies ten fundamental elements as rural transformation drivers: decentralized and shared production, using drones as a delivery method and mitigation tool, rural-urban linkages, the flow of information, decentralized and save energy system, using synthetic food, meat, that can reduce environmental hazards, technologically supported education, providing online health service for the rural community, connecting urban-rural online, and changing the mindset of rural people toward the change (OECD, n.d.).

4. Mauritius’ rural and structural transformation

4.1. Rural transformation policies of Mauritius

Since 1968, when Mauritius gained independence, she has achieved miraculous rural development (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Houbert, Citation1981). However, it was the poorest country during its independence (English, Citation2002). The main reasons behind the success of the transformation are a shift from mono-crops to multi varieties of crops, information, and technology-supported societies, and good feedback from the people (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Also, the government diversified the economy by shifting from agriculture to export-based industries (NEPAD-CAADP, Citation2005).

Accordingly, Mauritius set the first Four Years Plan (1971-1975) in consultation with World Bank for technical and financial support (Bank of Mauritius, Citation1976; Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Initially, there was an unequal income distribution due to improper development in rural areas. With the help of the World Bank, the Mauritius government established the Rural Development Unit (RDU) in 1971 which operated under the Ministry of Economic Planning to improve the rural peoples’ quality. Albeit nine villages accessed different social provisions such as access to good roads, village councils, village markets, electricity, water, health centers, and provision of social amenities at initial points, it has increased to 29 villages gradually (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012).

Furthermore, irrigation played a vital role in increasing productivity. "The extension of irrigation will play a major jects over the Plan Period 1971–1975 aiming at raising crop output since lack of adequate, and reliable rainfall is one of the prime constraints in keeping crop yield down below technically feasible levels" (Mauritius Ministry of Plan and Economic Development, Citation1971, pp. 69). Equally important, livestock production, fishery, and forestry have gotten attention to improve, extend, and support agricultural transformation (Ibid).

To raise the small farmers’ income, the government set a second plan. To that end, the government incorporated the Arsenal Litchis Project, the Riche Terre Cooperative project, credit loan facilities access, IFAD funds accessibilities, and the small entrepreneurs’ programs formations. Besides, to raise milk and meat production, improved cows (received from New Zealand and Anglo-Nubian) were allocated to selective farmers. The government reframed the Rural and Development Unit (RDU) as National Development Unit (NDU) in 1988 that was directed by Private Parliamentary Secretaries under the Prime Minister Office (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018).

In the same vein, Tandrayen-Ragoobur & Kasseeah (Citation2019), quoting Makoond (2011), explain the five phases of economic development in Mauritius:

The first phase was in the early 1970s when Mauritius was mainly a mono-crop economy with sugar and basic manufacturing. The second phase was in the 1980s when Mauritius diversified to other sectors like textile and tourism with local manufacturing. The third phase of the 1990s saw greater diversification via the services sector with the financial services and the freeport. The fourth development phase was based on the small island economy being perceived as a business platform for Information and Communication Technology (ICT)/Business Process Outsourcing (BPO), real estate, and seafood alongside the existing sectors like sugar, textile, and tourism. The fifth phase saw further diversification, with Mauritius being an integrated business platform for financial services, ICT/BPO, real estate, medical services, knowledge industry, seafood hub, hospitality, cane industry, renewable energy, and textile and fashion (p: 4).

Mauritius’ private sector remains among the most vibrant in Africa and features large companies as well as a robust small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) sector. Large private sector entities operate mainly in financial intermediation services, retail and wholesale, tourism and hospitality, real estate, and sugar production. The SME sector contributes 40% to the GDP and employs 55% of the workforce. The majority of SMEs are engaged in the wholesale and retail trade, transport logistics, manufacturing, and ICT (p: 6).

4.2. Drivers of rural transformation in Mauritius

Many elements contributed to the drivers of Mauritius’ structural and rural transformation. Relatively speaking, in Mauritius, among African countries, the rural transformation has been successfully achieved (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). The country has solved issues that curb the transformation like population growth, ethnic diversity, and remoteness (Vandemoortele & Bird, Citation2011). Furthermore, the government has widened land accessibility (NEPAD-CAADP, Citation2005). The land is the backbone of Mauritius’ social, economic, and political aspects. After being discovered by the Portuguese in 1505, the Mauritius land tenure passed different challenges. The country was colonized by several European countries one after another until it gained independence in 1968. The Dutch, French, and British colonized Mauritius respectively. Although the Dutch colonized the country, they did not establish land tenure. During French rule, the Mauritius lands were distributed to the French settlers which influenced the country’s agricultural system by creating an agricultural society and plantation economy (Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018). Social and economic statuses were considered in the number of lands and slaves owed. Lands were mainly possessed by French soldiers and governors (Truth & Justice Commission, Citation2011).

On the other hand, the British focused on sugar production during its rule. Consequently, agriculture got attention (Truth & Justice Commission, Citation2011). Due to the sugar market crisis from 1870 to 1920, producers sold the less productive portions of their landholdings under the grand morcellement process. The main target was to increase British operation profit (Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018).

However, the government took measures to improve the small rural incomes by designing first and second rural development plans that helped to realize rural transformation (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018). Activities such as agriculture and tourism that depend on the land are central themes to rural livelihoods (Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018). Hence, there are full employment opportunities in profitable sectors (NEPAD-CAADP, Citation2005).

Regarding land distribution, the country has not redistributed any lands in the country’s history (Bunware, Citation2014) because of the absence of indigenous settlers. Lands have been owned by private (dominantly), corporations, churches, and the royal family (Truth & Justice Commission, Citation2011). Farmers buy land to plow (Bunware, Citation2014). Correspondingly, the government has taken serious measures to raise rural livelihood and economic growth (Tandrayen-Ragoobur & Kasseeah, Citation2019). Chittoo & Suntoo (Citation2012) present that Mauritius rural transformation has been realized because of:

A strong link between people and government, the foundation of the district council and central officials, the establishment of the committee (district council) that collects garbage from rural areas regularly, and accessibility of opportunities for rural people to organize themselves and run those activities under the district council are transformation engines. The establishment of the Equal Opportunity Act helps to select people based on their performance, skills, and qualities so the level of corruption is low. Also, the formation of recreational and sports places in rural areas has accelerated the transformation. Similarly, the provision of quality education for all citizens and the provision of free rural transportation for all rural students played a significant role in the achievement of the transformation.

In the same vein, relying the government on local labor, especially, the labor reserved pool is another driver that supported the transformation. Additionally, women are employed in many agricultural sectors (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Also, government officials made good decisions and implementation in the rural transformation (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012; Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018). Furthermore, the participation of the private sector in rural hotels and other services created job opportunities for many rural youths (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Besides, a favorable business climate and solid infrastructure contribute much to the transformation (Powell, Citation2015).

Equivalently, participation in the different multilateral trading systems and various regional agreements helped the countries to get different marketplaces and financial support. The country is membership of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), the Regional Integration Facilitation Forum (RIFF), and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) (NEPAD-CAADP, Citation2005).

Finally, Vandemoortele and Bird (Citation2011) identify four fundamental drivers of the Mauritius transformation. Those are first, concerted nation-building strategies that cemented major ethnic groups together to balance power in social, economic, and political aspects. The second is a strong and inclusive institution that supports social consensus. The third is high levels and equitable public investments in human development. The last one is a pragmatic development strategy—heterodox liberalization and diversification.

4.3. Mauritius structural transformation

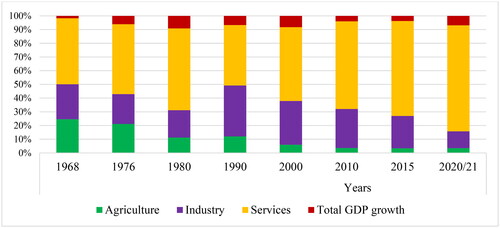

African social and economic structural transformation did not pull the society from poverty because of neoliberal policy pressure—the impact of policy merchandizing politics and neo-matrimonial instruments. Alleviating poverty is a fundamental element of structural transformation (Adesina, Citation2020). Like other African countries, Mauritius was under colony of different European countries that influenced the structural transformation directly or indirectly (Mutombo & Bimha, Citation2018; Truth & Justice Commission, Citation2011; Vandemoortele & Bird, Citation2011). shows the structural rural transformation summary of Mauritius focusing on the total GDP, agricultural sector, industry sector, and service sector shares in the GDP from its independence to recent years.

During independence, the total GDP growth was only 1.8%. At that time, the service sector contributed 49% to the total GDP. However, the agricultural and industrial shares were almost similar. Gradually, the share of industry in GDP increased until 1990. Between1980-1986, the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) influenced the country to undertake measures to boost the economy. On the other hand, the service share of GDP has increased dramatically from 49%, during the independence, to 83.2% in the 2020/21 period (Tandrayen-Ragoobur & Kasseeah, Citation2019).

During the 2002/03 period, agriculture shared less than 7% of the national GDP. Howbeit, financial services, and industry accounted for 90% of the country’s GDP. The majority of the country’s farmlands, about 90%, contributed to sugar production. In addition, vegetables and fruits were produced for domestic consumption and exports. Also, about 681 hectares of tea gardens produced 1,436 tonnes of black tea. In conclusion, Mauritius is the second largest exporter of anthurium flowers worldwide after the Netherlands—it exports an average annual 15 million stems (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012).

Consequently, in 2010, the Mauritius economic structures were dominated by services. To illustrate more, service shares 78.3% total GDP followed by industrialization which shares 18.1% total GDP, and agriculture shares only 3.5% of the total GDP (AfDB, OECD, UNDP & UNECA, 2012). Consequently, the Mauritius economic structures are dominated by tertiary economic activities, and services that share 83.1% of GDP in 2021/22 years. Nevertheless, industry contributes the second rank for GDP—13.2%. Lastly, agriculture shares only 3.7% of the GDP (Chikhuri, Citation2022). In the final analysis, the main stanchion of Mauritius’ economy is sugar, textile, tourism, and financial services (AfDB, OECD, UNDP, UNECA, 2012). To sum up, Mauritius has shown its potential for structural transformation. A shift from agriculture to manufacturing and services can be a role model for other African countries (Tandrayen-Ragoobur & Kasseeah, Citation2019).

Criticism against Mauritius’ structural transformation

Different scholars challenged the statistical presentation of Mauritius’ development. Chikhuri (Citation2022) argued that the country has never achieved successive rural transformation since it faced an economic crisis in the early 1980s. According to Chikhuri, the sugar export share decreased from 30% to 9% due to cyclones that caused the balance of payment deficit. Further, excessive public expenditure caused a budget deficit between 1978 and 1983 (Nath & Madhoo, Citation2004). They also added that the Country’s export has been dominated by sugar. However, that did not guarantee the country since sugar prices could decline globally, as it happened in the 1980s (Sobhee, Sanjeev K., 2014). Similarly, Mauritius faced a labor shortage in industries and services between the 1990s and 2000s, which decreased the country’s development from 7.8% to 5.5%. Besides, there is an imbalance between the tourists’ number and lodges since most of them are informal lodges (English, Citation2002).

In the same manner, “Diversity in Mauritius also implies that the linguistic composition of Mauritius exacerbates the complexity of communal relations in the country” which may affect sustainable development (Eriksen, Citation2020, p. 176). Furthermore, COVID-19 affected the Mauritius economy since it highly depended on the services. Following the outbreak of the pandemic in 2019, many countries followed lockdown. Tourists were restricted to travel to the Mauritius. Unemployment increased from 40,200 to 89,200. As a result, the Country’s economy declined by 33% in 2020 (UNDP Mauritius, Citation2021).

5. Conclusion

Rural transformation intends to diversify the economic base, and sources of income. African rural transformation has lagged because of a lack of well-organized policies and the absence of government commitment to generate and allocate sufficient funds. The unrelated development policies to the real problem on the ground exacerbate African rural transformation that leaves the community in vicious poverty (Daka & Tamira, Citation2019). Mauritius has achieved better rural transformation relatively. The country has invested much to realize the transformation by setting different policies and taking different measures to increase the share of services in the national GDP and decrease the agricultural share in the GDP. To sustain rural transformation, Mauritius in collaboration with FAO, identified three priority areas: assist agribusiness development, promote sustainable agriculture for food security, and promote sustainable fisheries (FAO, Citation2017). Furthermore, Mauritius established the Rural Development Unit that operated under the Ministry of Economic Planning to improve the rural people’s quality with the help of the World Bank. Besides, the government incorporated the Arsenal Litchis Project, the Riche Terre Cooperative project, credit loan facilities access, IFAD funds accessibilities, and the small entrepreneurs’ programs formations to accelerate the transformation. Generally, Mauritius’s economic activities are dominated by sugar, textile, tourism, and financial services (AfDB, OECD, UNDP, UNECA, 2012). Also, income diversification patterns consist of agricultural wage labor, non-agricultural wage labor, self-employment, and transfers to help the Country (Losch et al., Citation2012).

This paper has a significant policy implication for other African countries such as Ethiopia where about 80% of the population depends on agriculture. African countries need to learn many things from the Mauritius rural transformation. UNIDO (Citation2013) recommends that the rural economy needs to be diversified due to different factors like the prevalence of good governance. Consequently, African countries have to design and implement a policy that helps the continent to achieve rural transformation. Rural transformation is all about transparency and good governance that can be applied to all levels (Chittoo & Suntoo, Citation2012). Good governance is a tool that we use to combat maladministration and corruption. It also facilitates rural transformation since it incorporates the community into the center of decision-making.

This paper is limited to secondary sources of data. Consequently, it did not present the entire information regarding the Mauritius rural transformation based on the primary data. Further, it attempted to investigate how rural transformation in Mauritius can be a role model for other African countries if we address the limitation.

Acknowledgment

The researchers thank the unanimous reviewers of this manuscript for their constructive and genuine comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Figure 1. Structural economic transformation growth of Mauritius from 1968-2020/21.

Sources. Authors summary based on Tandrayen-Ragoobur and Kasseeah (Citation2019) and AfDB (Citation2022).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdisa Olkeba

Abdisa Olkeba is an assistant professor at the Bule Hora University and a PhD student at Addis Ababa University, Center of Rural Development. His research areas include foreign direct investment, mining, human trafficking, indigenous knowledge, politics, governance, rural transformation, women’s empowerment, and food security. He has served as department head of Civics and Ethical Studies and department head of Governance and Development Studies. Furthermore, he served as director of the internationalization office and director of the postgraduate school at Bule Hora University.

Getnet Alemu

Getnet Alemu is an associate professor of development economics at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development. His research areas are health, land policy, rural development and transformation, financial inclusion, livelihood, poverty, and aid architecture. Sara Belay, Molla Jember, and Haymanot Meseret are PhD students at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development.

Sara Belay

Getnet Alemu is an associate professor of development economics at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development. His research areas are health, land policy, rural development and transformation, financial inclusion, livelihood, poverty, and aid architecture. Sara Belay, Molla Jember, and Haymanot Meseret are PhD students at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development.

Molla Jember

Getnet Alemu is an associate professor of development economics at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development. His research areas are health, land policy, rural development and transformation, financial inclusion, livelihood, poverty, and aid architecture. Sara Belay, Molla Jember, and Haymanot Meseret are PhD students at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development.

Haymanot Meseret

Getnet Alemu is an associate professor of development economics at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development. His research areas are health, land policy, rural development and transformation, financial inclusion, livelihood, poverty, and aid architecture. Sara Belay, Molla Jember, and Haymanot Meseret are PhD students at Addis Ababa University, College of Development Studies, Center of Rural Development.

References

- Adesina, J. O. (2020). Policy merchandising and social assistance in Africa: Don’t call dog monkey for me. Development and Change, 51(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12569

- AfDB, OECD, UNDP, UNECA. (2012). Mauritius - African Economic Outlook. www.africaneconomicoutlook.org

- AfDB. (2022). Mauritius Economic Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/mauritius/mauritius-economic-outlook

- Arora, S. K. (2020). Postcolonialism: Theories, issues and applications. In J. Sarangi (Ed.), Presentation of postcolonialism in English. (Issue January 2007, pp. 29–44). New Delhi: Authorspress.

- Bank of Mauritius. (1976). Annual report for the year ended June 1975.

- Berdegué, J. A., Rosada, T., & Bebbington, A. J. (2013). The rural transformation. In Evolving concepts of development through the experience of developing countries (pp. 1–44). Oxford University Press.

- Booth, D., & Golooba-Mutebi, F. (2014). Policy for agriculture and horticulture in Rwanda: A different political economy? Development Policy Review, 32(s2), s173–s196. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12081

- Boto, I., Forabong, E., Lopes, I., & Kebe, H. (2012). Brussels rural development briefings – A series of meetings on ACP-EU Major for rural Transformation in Africa. Retrieved from http://brusselsbriefings.net

- Bunware, S. (2014). The fading developmental state – Growing inequality in Mauritius. Mauritius University. Retrieved from http://africainequalities.org/

- Chikhuri, K. (2022). Economic diversification the Mauritian experience. 13th session of the UNCTAD multi-year expert meeting on commodities and development. 1–13.

- Chittoo, H., & Suntoo, R. (2012). Rural development in a fast developing African society: The case of Mauritius. Global Journal of Human Social Science, 12(4), 18–23.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. V. Knight (ed.) (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. Retrieved from https://fe.unj.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Research-Design_Qualitative-Quantitative-and-Mixed-Methods-Approaches.pdf

- Daka, A., & Tamira, S. (2019). Rural communities, development policies, and social sciences practice: Advocacy for a citizenship of research in sub-Saharan Africa. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 07(09), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.79005

- Delgado, C. L. (1995). Rural transformation: The key to broad-based growth and poverty alleviation in Sub-Saharan Africa (7).

- English, P. (2002). Mauritius reigniting the engines of growth: a teaching case study. Processing, 23, 1–50. World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/615671468774609693/Case-study.

- Eriksen, T. H. (2020). The Mauritian dilemma. In Common denominators. African Books Collective. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003136088-8

- FAO. (2017). Country programming framework for Mauritius April 2014 food and agriculture organization of the United Nations (FAO). April 2014.

- Gardner, M., & Hay, C. (2016). Rural transfromation. Rural 21, the International Journal of Rural Development, 50(2), 1–44.

- Goorha, P. (2017). Modernization theory. In Oxford research encyclopedia of international studies. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.266

- Gwynne, R. N. (2009). Modernization theory. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (2nd ed., pp. 163–167). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10107-6

- Headey, D. D., & Jayne, T. S. (2014). Adaptation to land constraints: Is Africa different? Food Policy. 48, 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.05.005

- Hitchcock, P. (1997). Postcolonial Africa? Problems of theory. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 25(3), 233–244. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40003387

- Houbert, J. (1981). Mauritius: Independence and dependence. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 19(1), 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00054136

- Houngbo, G. (2014). The need to invest in Africa’s rural transformation. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_235398/lang–en/index.htm

- Houssou, N., Johnson, M., Kolavalli, S., & Asante-Addo, C. (2018). Changes in Ghanaian farming systems: Stagnation or a quiet transformation? Agriculture and Human Values, 35(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9788-6

- Inglehart, R. (2001). Modernization and sociological theories. In Neil J. Smelser, & Paul B. Baltes (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 9965–9971.Pergamon. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01921-5

- Kalumiya, N. (2018). Mauritius. African Economic Outlook.

- Klein, E., & Morreo, C. E. (2019). Postdevelopment in practice. In Postdevelopment in Practice: Alternatives, Economies, Ontologies. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429492136

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. (2nd ed.). New Age International Publisher.

- Losch, B., Fréguin-Gresh, S., & White, E. T. (2012). Structural transformation and rural change revisited: Challenges for late developing countries in a globalizing world. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication.

- Martinez, M. A. (2015). Modernization theory. In Encyclopedia of consumption and consumer studies. Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118989463.wbeccs173

- Matthews, S. (2004). Post-development theory and the question of alternatives: A view from Africa. Third World Quarterly, 25(2), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659042000174860

- Matthews, S. J. (2010). Post-development Theory. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.39

- Mauritius Ministry of Plan and Economic Development. (1971). Mauritius four year plan 1971-1975: Vol. II.

- Mckinnon, K. (2007). Postdevelopment, professionalism, and the politics of participation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(4), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00582.x

- Mellor, J. W. (2014). The high rural population density in Africa - What are the growth requirements and who participates? Food Policy. 48, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.03.002

- Mutombo, I., & Bimha, P. (2018). Mauritius land reform and rural transformation overview. In Political Economy of Southern Africa. Retrieved from https://politicaleconomy.org.za/download/mauritius-land-reform-and-rural-transformation-overview/?wpdmdl=4503&refresh=63b40a405c0a01672743488

- Muyanga, M., & Jayne, T. S. (2014). Effects of rising rural population density on smallholder agriculture in Kenya. Food Policy. 48, 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.03.001

- Nath, S., & Madhoo, Y. N. (2004). Explaining African economic growth performance: The case of Mauritius. (1).

- NEPAD-CAADP. (2005). Government of the Republic of Mauritius: National medium-term investment program: Vol. I.

- Ngah, I. (2012). Rural transformations development. International Conference on Social Sciences & Humanities UKM 2012 (ICOSH-UKM 2012), (December 2012), 1—11.

- OECD. (n.d). The 10 key drivers of rural change. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/rural/rural-development-conference/10-Key-Drivers-Rural-Change.pdf

- Phiri, D. T. (2019). Studying intergenerational processes in 21st-century rural African societies. Barn – Forskning om Barn og Barndom i Norden, 37(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.5324/barn.v37i2.3088

- Powell, J. B. (2015). Factors contributing to the rapid growth of Mauritius’ services economy.

- Power, M. (2023). Modernization theories of development. In International Encyclopedia of Anthropology (pp. 1–8). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea1888

- Romaniuk, S. N., & Joseph, P. (2017). Dependency theory. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of war: Social science perspectives (pp. 482–483). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483359878.n191

- Sharma, K. (2020). Bhutan’s new paradigm of development a revival of post development? A comparative assessment. International Journal of Management, 11(11), 1648–1657. https://doi.org/10.34218/IJM.11.11.2020.157

- Shrum, W. (2001). Science and Development. In Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 13607–13610. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03165-X

- Singh, A. K., Aggarwal, M., & Jain, P. (2019). Education and unemployment in rural and urban Kerala. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3464399

- Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V., & Kasseeah, H. (2019). Mauritius’ economic success uncovered (pp. 1–25).

- Tittonell, P. (2014). Livelihood strategies, resilience and transformability in African agroecosystems. Agricultural Systems, 126, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2013.10.010

- Truth & Justice Commission. (2011). Land reform: Legal and administrative aspects (Vol. 2). Retrieved from https://researchgate.net/

- UNDP Mauritius. (2021). The socio-economic impact assessment of COVID-19 in Mauritius. Retrieved from https://www.mu.undp.org/content/dam/mauritius_and_seychelles/docs/seia/the-socio-economomic-impact-assessment-of-covid-19-in-mauritius-final.pdf

- UNIDO. (2013). Rural transformation promoting livelihood security by adding value to local resources.

- Vandemoortele, M., & Bird, K. (2011). Progress in economic conditions: Sustained success against the odds in Mauritius.

- Waeterloos, E., & Cockburn, P. (2017). Rural transformation in South Africa and International development assistance.Retrieved from https://www.enabel.be/sites/default/files/utd_belgium_report_final_web.pdf

- Wiggins, S. (2014). African agricultural development: Lessons and challenges. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 65(3), 529–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12075

- Yilmaz, M., & Enwere, C. (2018). Postcolonial Africa’s development trajectories. In T. Falola & K. Kalu (Eds.), Africa and globalization, African histories and modernities (pp. 49–69). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74905-1

- Ynalvez, M. A., & Shrum, W. M. (2015). Science and development. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition (pp. 150–155). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.85020-5

- Ziai, A. (2014). Post-development concepts? Buen Vivir, Ubuntu, and degrowth. Degrowth Conference Leipzig, 2014, 1–9.

- Zougmoré, R. B., Läderach, P., & Campbell, B. M. (2021). Transforming food systems in Africa under climate change pressure: Role of climate-smart agriculture. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(8), 4305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084305