?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of locally enacted bylaws governing Autonomous Resilient Practices (ARP) on the food security of a sample of 700 smallholder farmers in Ghana’s Upper West Region. The research is grounded in the context of the Green Revolution’s inability to address food insecurity for large populations in Africa. The sequential mixed methods design employed in the study first identified eight prevalent coping strategies for food insecurity among farmers. A pairwise matrix ranking method was used for this task. Subsequently, Poisson regression models were employed to assess how often farmers resorted to these coping strategies when bylaws aimed at protecting the local ecology were enforced. The results reveal highly significant and inverse relationships between increased frequency of implementing local bylaws on ARP and farmers’ frequency of resorting to the eight identified coping strategies for food security. The results underscore the significance of grassroots-level solutions to the shortcomings of the current food system, which produces surplus food but fails to adequately nourish a substantial proportion of the global population

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

The Green Revolution largely staved off the doomsday predictions put forth in Thomas Malthus’ seminal work, which warned of dire consequences resulting from population growth outpacing food supply (Hamdan et al., Citation2022). However, due to new challenges arising from an increasingly limited natural resource base, climate change, and a growing human population, humanity finds itself once again teetering on the brink of another potential cataclysmic event. It has been argued that in areas where the wave of Green Revolution touched, attention was more on increasing food quantity, largely to the neglect of its nutritional value. As a result, production was within a limited bandwidth of crops that basically supplied carbohydrates, including rice, wheat and maize (Eliazer Nelson et al., Citation2019). These cereals are implicated in the problem of hidden hunger across the world (Burchi et al., Citation2011); inadequate dietary diversity in the food system, resulting in micronutrient deficiency in the human body. These deficiencies are the precursors to many diseases.

The Green Revolution has also given rise to the problem of seed sovereignty, particularly for smallholder farmers in developing countries (Shiva, Citation2004; Shiva et al., Citation2000). The central question regarding the issue of seed sovereignty revolves around who has control over seeds. The food system is currently being controlled by giant agribusinesses at the expense of farmers. A few corporate entities have dominated the market with their monocrops to the extent that they have severely limited dietary diversity across the globe.

Although Asia and Latin America have benefitted from the advantages of the Green Revolution, substantial portions of the African continent have not experienced a similar trajectory, despite considerable funding and concerted efforts to foster agricultural development (Food and Agriculture Organization, Citation2022, Citation2023; Toenniessen et al., Citation2008). Even the continued production of crops using Green Revolution technology is now in jeopardy due to an unpredictable climate, which affects the resilience of the current food system. This system’s over-reliance on synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, insecticides, herbicides and fungicides to boost production quantities is starting to raise environmental and health concerns among the consuming public (Brainerd & Menon, Citation2014; Guan et al., Citation2023; John & Babu, Citation2021; Kpienbaareh et al., Citation2023; Liu et al., Citation2020). As the Economist Group (Citation2022) suggests, food security can only be enhanced when the food produced is affordable, available, and resilient to shocks. It should also be safe to consume and of high quality. The current food system must, therefore, move beyond quantity and incorporate quality and sustainability. These challenges have raised questions about the Green Revolution’s capacity to ensure a resilient food system, especially for food-insecure smallholder farmers.

Ghana, like many other African countries, is considerably affected by the current broken food system. The most recent State of Food Insecurity Report by the Food and Agriculture Organization et al. (Citation2023, p. 151) estimates that the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in Ghana rose from 38.30% in the period between 2014 and 2016 to 39.40% in the period between 2020 and 2022. A large percentage of those suffering from food insecurity are in the Upper West Region (Fuseini et al., Citation2019). Ironically, smallholder farmers, who contribute over 70% of the food calories to the people living in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Fanzo, Citation2017) often cannot access and use the very food they produce at certain times of the year (Luginaah et al., Citation2009). This is mainly because of the broken food system. Producing more food is important, but so is ensuring that it is healthy and gets to those who need it the most.

These challenges underscore the need to overhaul the current global food system. While it has served humanity well in the past, it is increasingly becoming outdated in the face of the current array of challenges. Given that smallholder farmers have acted as stewards of the land for generations, it would be a mistake for humanity to completely abandon their time-tested resilient local practices. One such resilient farming approach is agroecology, credited with enhancing both production and dietary diversity, particularly among subsistence farmers (Kansanga et al., Citation2021; Kerr et al., Citation2018). To enhance the journey of food from farm to fork, therefore, locally grown solutions to food security are necessary. This is because a forward-looking solution to the current broken food system requires a corresponding exploration of history to draw knowledge from the past.

The literature is replete with the benefits (e.g. Hamdan et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2020) and fallouts (e.g. Brainerd & Menon, Citation2014; Eliazer Nelson et al., Citation2019; John & Babu, Citation2021) of the Green Revolution. Substantial work has also been done on the imperative of safeguarding ecosystems for sustained food security (e.g. Ankrah et al., Citation2023; Asare-Nuamah & Mandaza, Citation2020; McMichael et al., Citation2007; Smith & Gregory, Citation2013). Drawing insights from autonomous resilient practices (ARP) in rural Upper West Region of Ghana, this paper takes these discussions further by unravelling how locally promulgated bylaws can affect farmers’ food insecurity. In so doing, it unravels the ripple effects of enforced ecologically friendly bylaws and practices on farmers’ ability to reduce their frequency of coping with food insecurity. This inquiry holds notable importance because though smallholder farmers in rural areas often reside in marginal lands and are disproportionately affected by climate change and the dysfunctional food system, they possess relevant environmentally friendly strategies that can be tapped for improved food security. It is also essential to develop localised solutions to address the unique impacts of climate change seen in various regions of the world.

Theoretical foundation

The ecological resilience theory (Angeler, Citation2021; Holling, Citation1973; Walker & Salt, Citation2012) and the food insecurity coping strategy framework (Maxwell, Citation1996; Maxwell et al., Citation2008) undergird this study. While the ecological resilience theory helps explain farmers’ ability to protect the fragile ecology on which their food security depends, the coping strategy framework serves as a foundation for understanding how farmers have often adjusted to food insecurity in the study area. These two theoretical foundations are discussed in detail next.

The ecological resilience theory

In his landmark paper, Holling (Citation1973), who first propounded the ecological resilience theory, defined resilience as ‘the measure of the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations or state variables’ (Holling, Citation1973, p.14). Ecological resilience thus refers to an ecosystem’s capacity to absorb and respond to perturbations (Angeler, Citation2021). Climate change resilience on the other hand is a broad term encompassing a system’s capacity to absorb and recover from stresses associated with the changing climate (Hashemi et al., Citation2017). In the context of this study, resilience is conceptualised as the ability of smallholder farmers to adapt to their food insecurity situation in the face of increasingly challenging climatic conditions by making the most of local sustainable agronomic practices. Farmers who can successfully adapt under such circumstances are described as having the ability to employ their Autonomous Resilient Practices (ARP) to ensure their food security.

The food insecurity coping strategies framework

The traditional approach to food insecurity measurement is hinged on indirect indicators, including calories consumed, household income, productive assets and food storage. These are however proximate measurements given that they only address the causes and effects of food insecurity (Maxwell et al., Citation2008). The context-specific coping strategies approach uses the actions of the food-poor to determine how they subsist in times of food insecurity (Maxwell, Citation1996; Maxwell et al., Citation2008). The coping strategy approach therefore focuses on contextual behaviour patterns that people within a specific area would fall on when faced with food insecurity. This is important as tailor-made solutions can be fashioned out to address specific food insecurity situations. In addition, the coping strategy approach lends itself to quick data collection for researchers with limited budget. It is therefore useful in humanitarian situations where quick decisions about food insecurity need to be made for immediate intervention (Maxwell et al., Citation1999).

Materials and methods

Study area

The Upper West Region is located in the Guinea Savannah ecological zone of Ghana. It is home to about 901,502 people and has a land area of 18,476 km2 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). The region relies heavily on smallholder farming as its primary source of income. Due to their significant dependence on rain-fed agriculture and their limited ability to adapt, smallholder farmers in the region are among the least resilient to the effects of climate change (Kerr et al., Citation2018; Kusakari et al., Citation2014). Estimates show that economies that are dependent on rain-fed agriculture will experience a major decline in crop productivity, which will have a serious impact on their food security (Mohammed et al., Citation2021). More so, the increasing levels of backlash received by major players in the current global food system regarding the misuse of pesticides and chemical fertiliser point to the fact that smallholder farmers’ simple but sustainable farming approaches should not be dispensed with since it has enhanced the resilience of the ecology on which humanity has depended for many generations (Altieri & Nicholls, Citation2020; Dapilah et al., Citation2020; Kpienbaareh et al., Citation2023; Shiva, Citation2004; Shiva et al., Citation2000).

Study design

Data collection

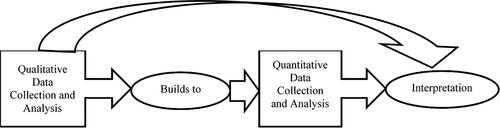

As shown in , a two-phase exploratory sequential mixed method design (Creswell, 2012) was used. The first phase involved the use of a participatory rural appraisal approach called pairwise ranking (Narayanasamy, Citation2009). This was used to identify and rank the various context-specific food insecurity coping strategies adopted by farmers in their local settings. The second phase entailed using the identified coping strategies as dependent variables for determining the Autonomous Resilient Practices (ARP) used by farmers in their bid to protect the ecology on which they depend for food.

Figure 1. The Exploratory sequential mixed method design guiding the study.

Source: Adapted from Creswell (2012).

In phase I, data were collected during a stakeholders’ forum on the relevance of biodiversity in the Upper West Region. Nine gatekeepers in the three sampled districts, including traditional leaders, smallholder farmers, assembly members and civil society organisation representatives were invited to take part in a focus group discussion on how they and their constituents cope with food insecurity. At the district level, one FGD was conducted in a district within each of the sampled districts. The aim was to gather further insight regarding the topic under study. In summary, a total of four focus groups were conducted for the study; three in each district and one held with community level gatekeepers.

The FGD with gatekeepers resulted in a total of eight food insecurity coping strategies. These coping strategies were then ranked based on their frequency of being relied on in their communities using the pairwise ranking method (Narayanasamy, Citation2009). These eight coping strategies were further condensed into a composite score for further analysis. Phase II of the study then built on phase I by using the eight ranked coping strategies as dependent variables. shows the eight dependent variables and their respective a priori expected outcomes in the study.

Table 1. Dependent variables measuring farmers’ food insecurity coping strategies.

Sampling approach

The study purposefully selected the three districts of Nadowli-Kaleo, Jirapa, and Nandom based on insights gained from the focus group discussion with relevant gatekeepers. Communities in these districts were identified as largely relying on the eight food insecurity coping strategies. Furthermore, specific traditional authorities in communities, such as Goziir in the Nandom District and Zambogu in the Nadowli-Kaleo District were recognised for their role in enforcing ARP. To select respondents, a combination of stratified and simple random sampling techniques was employed. Each of the three districts formed a distinct, non-overlapping stratum. From each stratum, 233 individual respondents were chosen using the simple random sampling technique, totaling 699 respondents across the three districts. This number was rounded up to 700.

Data analysis

Using incidence rate ratios (IRR) derived from the Poisson regression model (PRM) (Long & Freese, Citation2014), each of the eight dependent variables was regressed on a set of independent variables. This approach was arrived at given that the eight dependent variables were counts. The explanatory variable of interest was the frequency of enforcing local bylaws that promoted autonomous resilient practices (ARP) in the study districts. This was measured by the frequency with which the environmental protection committee met in a year to adjudicate cases bordering on the flouting of regulations regarding ARP so as to stem ecological destruction. The study’s a priori assumption was that proper enforcement of these bylaws on ARP would have an inverse relationship with farmers’ frequency of resorting to each of the eight coping strategies identified by respondents in . In other words, farmers’ food security would be hinged on the extent to which the local bylaws on ARP were able to rejuvenate the ecology. This is because the local ecosystem forms the basis for the food security of farmers.

Other control variables measuring the various ARP in the study area were the number of surviving trees each farmer personally planted and nurtured into growth since the enforcement of bylaws on ARP, farmers’ frequency of using compost on their field in a year and their frequency of engaging in in-situ incorporation of farm residue on the farm in a year. Negative ecological practices that the ARP laws frowned on were bushfires, (measured as yearly frequency of bushfires recorded by farmer on their farms), unapproved tree felling (measured as frequency of felling live trees in a month without permission from the local taskforce enforcing ecological protection, and slash-and-burn farming (measured as respondents’ frequency of engaging in slash-and-burn farming in a year). The remaining control variables for the study were farmers’ socio-demographic characteristics as shown in . These results were then complemented with quotes derived from FGDs conducted with beneficiary community members.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Model specification

Following Long & Freese (Citation2014) we estimate the effect of ARP on farmers’ food insecurity coping strategies by employing incidence rate ratio (IRR) from the Poisson regression model. Assuming the variable ‘food insecurity coping strategies’ is a function of ARP and other control variables, the relationship could be modelled as;

(1)

(1)

Where represents the expected number of times that respondents had to resort to the various food insecurity coping strategies. By exponentiating X

, in Equationequation 1

(1)

(1) above, we limit µ to a positive number in line with requirements for count variables to be 0 or positive. In Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1) , the interpretation of

employs the factor change approach. Let us assume that

is the expected count for the eight dependent variables measuring food insecurity coping strategies (denoted here as

in Equationequation 2

(2)

(2) ), where

is the expected count after increasing

by 1, then

(2)

(2)

The interpretation of the results in Equationequation 2(2)

(2) then is as follows: when

changes by one unit, the expected count changes by a factor of

, while holding all other variables constant.

Results and discussion

As shows, farmers’ frequency of resorting to all eight coping strategies identified in the study ranged from 0 to 14, suggesting that while some farmers did not resort to these coping strategies, others relied on them as many as fourteen times in a week. Thus, some farmers resorted to coping strategies like consuming limited portion sizes of food and scavenging around public grinding mills for leftover and discarded flour almost on a daily basis. Farmers’ average frequency of employing these eight coping strategies for food insecurity fluctuated between 0.583 (close to once a week) and 1.907 (close to twice a week). Their average frequency of subsisting on limited food portion sizes in a week was their most prevalent coping strategy to food insecurity since they employed this strategy about twice in a week (i.e. a mean of 1.907).

In terms of the variable of interest for this study (i.e. frequency of enforcing local bylaws that punish perpetrators of autonomous resilient practices (ARP) to stem ecological destruction), shows that the maximum number of sittings to adjudicate on issues pertaining to ARP was four times in a year. Punishments meted out to offenders of ecological destruction included the payment of fines and being ordered to replant trees if they felled live trees without the permission of the environmental protection taskforce. Offenders who could not afford the payment of fines were engaged in communal labour as a form of deterrence. Evidence of these practices was borne out during FGDs with community members at the Goziir and Zambogu.

If you are caught flouting our regulations on environmental protection, you are sanctioned but if you are a student, you are asked to collect stones amounting to about a trip so that the taskforce will sell it and the proceeds lodged into the community development fund account. For those who are employed, the least fine is fifty Ghana cedis but it can increase depending on how serious the fire has destroyed properties. Even if you refuse to join in quenching any wildfire, you are also fined fifty cedis for not supporting the community.

(Voice of a female focus group discussant at Goziir, Nandom District).

You can only cut dead branches for firewood… and other community members must bear witness to this. If someone cuts down a tree without permission, he or she is fined two live fowls, 50 Ghana cedis (approximately USD4.50) and a bottle of ‘akpeteshi’ [a locally brewed alcoholic drink]. The offender will also be required to plant a new tree to replace the one s/he has cut.

(Voice of a female focus group discussant at Zambogu, Nadowli-Kaleo District).

The fear of being accused of obstructing the community’s collective effort to safeguard their ecology had the subtle influence of prompting people to conform to the bylaws that sought to promote autonomous resilient practices.

In terms of the various ARP in the study area, the average number of surviving trees each farmer personally planted and nurtured into growth since the enforcement of bylaws on ARP was about three (mean of 3.010) and the maximum number of trees planted was 100 (see ). As the literature has shown (e.g. Mina et al., Citation2023; Ramachandran Nair et al., Citation2009), trees form an integral part of ecological protection given that they capture and sequester carbon to reduce the deleterious effects of climate change. Trees also help create a stable microclimate for farming.

Farmers’ frequency of using compost on their farms and engaging in in-situ incorporation of farm residue on the farm were both about once a year on average (i.e. mean of 0.741 and 0.873 respectively). Their maximum number of compost applied and in-situ soil rejuvenation in a year however varied (i.e. 5 times and 14 times respectively). The relevance of sustainable farming practices such as composting and in-situ re-injection of farm residue on farms has been emphasised in the literature (Ankrah Twumasi et al., Citation2023) because produce from such organic farming practices fetch more income and are healthier for the consuming public. Other control variables, as seen in were farmers’ socio-demographic characteristics such as age (ranging from 21-80 years), their districts of domicile, marital status, their sex categories, their educational status and whether or not they were breadwinners in their various households.

Pairwise matrix ranking of farmers’ coping strategies for food insecurity

The pairwise matrix was instrumental in ranking the most prevalent food insecurity coping strategies employed by farmers. By breaking down the various coping strategies into pairs for comparison, one could rank the frequency with which farmers resorted to the identified coping strategies. As shown in , the most prevalent coping strategy in the three districts involved farmers subsisting on limited portion sizes of food in an attempt to stretch their food supply over an extended period, a practice employed daily (seven times a week). Following this was borrowing food, practised six times a week. The third most common option for the food-insecure was to consume immature produce from their farms, done five times a week. Subsequently, maternal buffering, foraging from the wild for fauna and flora, as well as the sale of productive assets were observed. The least frequent coping strategy involved gleaning from their neighbors’ farms after their neighbors had harvested.

Table 3. Farmers’ pairwise matrix ranking of their coping strategies for food insecurity.

Effects of ARP on the eight food insecurity coping strategies

All eight variables measuring the food security of farmers in the three study districts converge on the fact that the promulgation and enforcement of environmentally friendly local level bylaws improved beneficiary communities’ autonomous resilien Practices (ARP). These ARP bolstered local farmers’ resilience to the challenges associated with the broken food system. The results further show highly significant reductions in farmers’ weekly frequency of borrowing food from neighbours, consuming immature crops from their farms, sale of farm animals to buy food as well as foraging for wild fruits and undomesticated animals. The coping strategy approach to measuring food insecurity mentions that when farmers start to fall on immature crops for subsistence, it marks a sign of severe food insecurity (Maxwell, Citation1996). Farmers also experienced highly significant reductions in their weekly frequency of cutting back on their food portion sizes, maternal bufferingFootnote1, and gleaning from neighbours’ farms as well as visiting public grinding mills to gather leftover flour to feed themselves. A unit increase in the frequency of enforcing ARP was associated with a reduction in farmers’ weekly frequency of subsisting on borrowed food by a factor of 0.765 while holding all other variables in the model constant. Similarly, farmers’ frequency of foraging wild fruits (e.g. ebony, shea) and undomesticated animals (e.g. rabbits, bats, mice and rats) witnessed a reduction upon enforcing bylaws on ARP. A unit increase in the frequency of enforcing ARP was associated with a reduction in farmers’ frequency of depending on these wild fruits and game for subsistence by a factor of 0.721 (see model 2 in ). The search for meat from the wild, colloquially known as ‘bush meat hunting’, has been implicated in the onset of wildfires in Ghana because hunters burn the bush to drive their game out of the bushes with smoke and heat (Ampadu-Agyei, Citation1988). As a result of rampant fires during the dry season, Krah & Njume (Citation2020) study of rural communities show collaborative efforts between the Ghana National Fire Service and rural communities. The Ghana National Fire Service has set up a Rural Fire Division which trains community fire volunteers on how to prevent wildfires.

Table 4. Incidence rate ratios from Poisson regressions showing the influence of ARP on farmers’ coping strategies for food insecurity.

The results in further show that a unit increase in the frequency of enforcing ARP is associated with a reduction in farmers’ frequency of depending on immature crop by a factor of 0.632 on a weekly basis, suggesting that farmers did not have to subsist on immature crops (e.g. cowpea and maize) they had planted on their farms. They rather waited till they matured before harvesting. Beyond a significant reduction in their frequency of harvesting and consuming immature crops, the results further show that farmers frequency of consuming limited food portion sizes for fear of running out of food in a year reduced by a factor of 0.787 for every unit increase in ARP enforcement. Farmers frequency of maternal buffering as well as their weekly frequency of going to public grinding mills to beg for discarded flour reduced with increased ARP enforcement. A unit increase in ARP enforcement is associated with a reduction in frequency of maternal buffering by a factor of 0.641 and frequency of going to public grinding mills to beg for discarded flour by a factor of 0.688 respectively. This flour, according to respondents, became their lifeline in times of food insecurity. Another measure of subsistence farmers’ wealth is the number of farm animals they possessed. The sale of livestock, including cattle, sheep, goats and pigs marked a period of severe food insecurity among smallholder farmers. The results therefore suggest that farmers witnessed a reduction in their frequency of selling their productive assets (e.g. bullocks) and livestock to buy food by a factor of 0.624 for every unit increase in ARP enforcement. This suggests that the ARP adopted by local leaders was paying off. Farmers also reduced, by a highly significant margin, their frequency of going to neighbours’ farms to glean from the farms of their more well-off neighbours after harvest.

Beyond the primary explanatory variable of interest (bylaws enforcing ARP), other control variables give further insight into the nature of farmers’ coping strategies for food insecurity. The bylaws ensured that positive ARP that were dying down over the years were resurrected and enforced to ensure the resilience of the environment. These positive ARP were tree planting, in-situ farm residue reuse and composting. With the exception of maternal buffering, the remaining seven estimates on the effects of tree planting on farmers’ frequency of resorting to food insecurity coping strategies showed significant and inverse relationships upon the enforcement of the local bylaws. For instance, an additional tree planted by farmers in the community after the enforcement of the bylaws on ARP was associated with a reduction in farmers’ frequency of borrowing food from neighbours by a factor of 0.973. Furthermore, an additional tree planted was associated with a reduction in farmers’ frequency of gleaning food crops from their neighbours’ farms by a factor of 0.998. These results are quite intuitive given that trees have been described as ‘lungs of the earth’, purifying the air, aiding in rainfall and generally helping farmers to develop resilience to the vicissitudes of the changing climate. With a predictable climate, farmers could plan, cultivate and harvest food for themselves without borrowing or gleaning on their neighbours’ farms. Another factor that significantly reduced farmers’ coping strategies for food insecurity was their frequency of composting. This is evidenced in the highly significant and inverse relationships between farmers’ frequency of engaging in composting and their frequency of resorting to all eight food insecurity coping strategies (). A unit increase in a farmer’s frequency of applying compost on their farm was associated with a reduction in farmers’ frequency of borrowing food from neighbours, cutting back on their food portion sizes, consuming immature crops, depending on discarded and leftover flour in public grinding mills, the sale of their productive assets such as bullocks and other farm animals and gleaning from neighbours’ farms. The results further show that a unit increase in the use of in-situ farm residue after harvest resulted in highly significant reductions in farmers’ frequency of subsisting on two of the eight coping strategies, namely limited portion sizes of food and maternal buffering. Surprisingly, however, farmers’ frequency of scavenging from public grinding mills increased by a factor of 1.178, holding all other variables in the model constant. These results largely buttress arguments in the literature on the importance of organic fertiliser for food security (Patel et al., Citation2020).

Aside encouraging the positive ARP, the bylaws also frowned on negative agronomic practices of farmers that were impinging on the resilience of their ecology, and as a result, reduced their resilience to food insecurity. These negative practices were setting the bush ablaze in search of game, thereby causing bushfires, indiscriminate felling of trees for fuel-wood and for sale, and engaging in slash-and-burn farming. All three negative practices largely had a direct relationship with farmers’ increased frequency of coping with food insecurity. The results show significant and direct associations between farmers’ frequency of bush burning and their frequency of food borrowing, foraging for wild fruits (e.g. ebony and shea) and animals (e.g. rats and rabbits), immature crop consumption, consumption of limited food portion sizes, maternal buffering, begging from grinding mills, sale of their productive assets such as bullocks, and gleaning from neighbours. In a similar fashion, a direct relationship exists between farmers’ frequency of felling trees and the accentuation in their coping strategies for food insecurity.

Robustness checks

For robustness, a Breusch-Pagan test of independence of error terms is run to determine if the error terms in models estimated earlier are independent or cross-correlated. With a significant Breusch Pagan statistic (chi2 = 1937.925), the null hypothesis of independent error terms is rejected. The errors in the various models are cross-correlated to enable the estimation of a multivariate regression model. presents the results of a Seemingly Unrelated Regression model. The results of the SUR model indicate that ARP enforcement is associated with a reduction in all eight (8) coping strategies. The results are consistent with earlier findings in .

Table 5. Results of the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) models.

Conclusions and recommendations

This article has shed light on the influence of a resilient ecology on enhanced food security in the Upper West Region of Ghana. By employing the ecological resilience framework and the coping strategy framework, the findings revealed that when local communities mobilise themselves and enforce local regulations to protect their natural surroundings, it leads to an improvement in food security among community members. All eight identified coping strategies for food insecurity, together with their composite score, showed significant reductions when local leaders enforced bylaws aimed at increasing autonomous resilient practices (ARP). Furthermore, ecologically sound practices such as tree planting, composting, and in-situ re-injection of plant residues significantly decreased farmers’ frequency of relying on various coping strategies for food insecurity. Conversely, increases in harmful ecological practices such as bush burning, unrestricted tree cutting, and slash-and-burn farming had significant and direct association with how frequently farmers resorted to the various coping strategies for food insecurity.

To effect these local bylaws, local taskforces were created to monitor the environment. Among other things, these taskforces were trained by Ghana National Fire Service on how to identify and dowse bushfires. Volunteers of the local taskforce also received whistles. These were blown in order to sound an alarm to community members when they saw wildfires. Any community member who heard the sound of the whistle was obliged to proceed to the point of inferno and help quench it. If bushfires got out of hand, the locals called on the expertise of the Ghana National Fire Service. The taskforce also protected trees from indiscriminate felling. These findings underscore the capacity of local communities to formulate and enforce local regulations that enhance their resilience and food self-sufficiency, especially in anticipation of potentially catastrophic events that smallholder farmers may face due to climate change. It also emphasises the importance of grassroots solutions to the flaws in the current food system, which produces excess food but fails to adequately feed significant segments of the global population. Beyond pointing to the need for collaborative work between change agents such as NGOs and central governments on the one hand and local actors on the other, the study further highlights the indispensable role of local authorities and community members in humanity’s collective effort to reduce hunger and promote sustainable agriculture as espoused in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, Citation2022).

Authors’ contributions

Alexis Beyuo conceived the idea and collected data. Francis Dompae and Paul Domanban Bata conducted the statistical analysis. Alexis Beyuo wrote the manuscript in consultation with Francis Dompae and Paul DomanbanBata.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study the University of Ghana’s Ethics Committee for the Humanities (Approval number: ECH 031/16-17).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained for respondents to publish their details in this article.

Author bios.docx

Download MS Word (12.2 KB)Supplementary materials.docx

Download MS Word (27.9 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alexis Beyuo

Alexis Beyuo has a PhD in Development Studies from the University of Ghana. He is a lecturer at the Simon Diedong University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa. His research interests centre on sustainable agriculture, grassroots participation in development and food security.

Francis Dompae

Francis Dompae holds a PhD in Development Studies and is currently a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research of the University of Ghana. He researches on issues of agricultural technology and development.

Paul Bata Domanban

Paul Bata Domanban PhD is a Senior Lecturer at the Simon Diedong University of Business and Integrated Development Studies.

Notes

1 Instances in which older household members, particularly breastfeeding mothers, sacrifice their own food intake due to food shortages, ensuring that their children have enough to eat (Maxwell, Citation1996).

2 Situations in which, because to food shortage, older household members, and especially breastfeeding mothers, forego food in order that their children may have enough to eat (Maxwell, Citation1996).

References

- Altieri, M. A., & Nicholls, C. I. (2020). Agroecology and the reconstruction of a post-COVID-19 agriculture. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1782891

- Ampadu-Agyei, O. (1988). Bushfires and management policies in Ghana. The Environmentalist, 8(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02240254

- Angeler, D. G. (2021). Conceptualizing resilience in temporary wetlands. Inland Waters, 11(4), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/20442041.2021.1893099

- Ankrah Twumasi, M., Zheng, H., Asante, I. O., Ntiamoah, E. B., & Amo-Ntim, G. (2023). The off-farm income and organic food expenditure nexus: Empirical evidence from rural Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2258845. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2258845

- Ankrah, D., Okyere, C., Mensah, J., & Okata, E. (2023). Effect of climate variability adaptation strategies on maize yield in the Cape Coast Municipality, Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2247166. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2247166

- Asare-Nuamah, P., & Mandaza, M. S. (2020). Climate change adaptation strategies and food security of smallholder farmers in the rural Adansi north district of Ghana. In W. Leal Filho, J. Luetz, & D. Ayal (Eds.), Handbook of climate change management: Research, leadership, transformation (pp. 1–20). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22759-3_142-1

- Brainerd, E., & Menon, N. (2014). Seasonal effects of water quality: The hidden costs of the Green Revolution to infant and child health in India. Journal of Development Economics, 107, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.11.004

- Burchi, F., Fanzo, J., & Frison, E. (2011). The role of food and nutrition system approaches in tackling hidden hunger. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(2), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020358

- Dapilah, F., Nielsen, J. Ø., & Friis, C. (2020). The role of social networks in building adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change: a case study from northern Ghana. Climate and Development, 12(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1596063

- Economist Group. (2022). The global food security index (GFSI). https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/reports/Economist_Impact_GFSI_2022_Global_Report_Sep_2022.pdf

- Eliazer Nelson, A. R. L., Ravichandran, K., & Antony, U. (2019). The impact of the Green Revolution on indigenous crops of India. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0011-9

- Fanzo, J. (2017). From big to small: the significance of smallholder farms in the global food system. The Lancet Planetary Health, 1(1), e15–e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30011-6

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2022). World food and agriculture statistical yearbook 2022. Food and Agriculture Organization. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc2211en

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2023). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en.

- Fuseini, M. N., Enu-Kwesi, F., & Sulemana, M. (2019). Poverty reduction in Upper West Region, Ghana: Role of the livelihood empowerment against poverty programme. Development in Practice, 29(6), 760–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1586833

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census general report volume 3A: Population of regions districts. https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/2021

- Guan, N., Liu, L., Dong, K., Xie, M., & Du, Y. (2023). Agricultural mechanization, large-scale operation and agricultural carbon emissions. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2238430. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2238430

- Hamdan, M. F., Mohd Noor, S. N., Abd-Aziz, N., Pua, T.-L., & Tan, B. C. (2022). Green revolution to gene revolution: Technological advances in agriculture to feed the world. Plants, 11(10), 1297. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11101297

- Hashemi, S. M., Bagheri, A., & Marshall, N. (2017). Toward sustainable adaptation to future climate change: Insights from vulnerability and resilience approaches analyzing agrarian system of Iran. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 19(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9721-3

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- John, D. A., & Babu, G. R. (2021). Lessons from the aftermaths of green revolution on food system and health. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 644559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.644559

- Kansanga, M. M., Kangmennaang, J., Kerr, R. B., Lupafya, E., Dakishoni, L., & Luginaah, I. (2021). Agroecology and household production diversity and dietary diversity: Evidence from a five-year agroecological intervention in rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 288, 113550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113550

- Kerr, R. B., Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H., Dakishoni, L., Lupafya, E., Shumba, L., Luginaah, I., & Snapp, S. S. (2018). Knowledge politics in participatory climate change adaptation research on agroecology in Malawi. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 33(3), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170518000017

- Kpienbaareh, D., Kansanga, M. M., Yiridoe, E., & Luginaah, I. (2023). Exploring the drivers of herbicide use and risk perception among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Gender, Technology and Development, 27(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2022.2092939

- Krah, C. Y., and Njume, A. C. (2020). Refocusing on community-based fire management (a review). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 504(1),012015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/504/1/012015

- Kusakari, Y., Asubonteng, K. O., Jasaw, G. S., Dayour, F., Dzivenu, T., Lolig, V., Donkoh, S. A., Obeng, F. K., Gandaa, B., & Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. (2014). Farmer-perceived effects of climate change on livelihoods in Wa West District, Upper West region of Ghana. Journal of Disaster Research, 9(4), 516–528. https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2014.p0516

- Liu, S., Zhang, M., Feng, F., & Tian, Z. (2020). Toward a “green revolution” for soybean. Molecular Plant, 13(5), 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.03.002

- Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata (3rd ed., Vol. 3). Stata Press.

- Luginaah, I., Weis, T., Galaa, S., Nkrumah, M. K., Benzer-Kerr, R., & Bagah, D. (2009). Environment, migration and food security in the Upper West Region of Ghana. In Environment and health in Sub-Saharan Africa: Managing an emerging crisis (pp. 25–38). Springer.

- Maxwell, D. (1996). Measuring food insecurity: The frequency and severity of coping strategies. Food Policy. 21(3), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(96)00005-X

- Maxwell, D., Ahiadeke, C., Levin, C., Armar-Klemesu, M., Zakariah, S., & Lamptey, G. M. (1999). Alternative food-security indicators: Revisiting the frequency and severity ofcoping strategies. Food Policy. 24(4), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(99)00051-2

- Maxwell, D., Caldwell, R., & Langworthy, M. (2008). Measuring food insecurity: Can an indicator based on localized coping behaviors be used to compare across contexts? Food Policy. 33(6), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.02.004

- McMichael, A. J., Powles, J. W., Butler, C. D., & Uauy, R. (2007). Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet (London, England), 370(9594), 1253–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61256-2

- Mina, U., Geetha, G., Sharma, R., & Singh, D. (2023). Comparative assessment of tree carbon sequestration potential and soil carbon dynamics of major plantation crops and homestead agroforestry of Kerala, India. Anthropocene Science, 2(1), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44177-023-00052-6

- Mohammed, K., Batung, E., Kansanga, M., Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H., & Luginaah, I. (2021). Livelihood diversification strategies and resilience to climate change in semi-arid northern Ghana. Climatic Change, 164(3-4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03034-y

- Narayanasamy, N. (2009). Participatory rural appraisal: Principles, methods and application. SAGE Publications India.

- Patel, S. K., Sharma, A., & Singh, G. S. (2020). Traditional agricultural practices in India: An approach for environmental sustainability and food security. Energy, Ecology and Environment, 5(4), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-020-00158-2

- Ramachandran Nair, P. K., Mohan Kumar, B., & Nair, V. D. (2009). Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 172(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200800030

- Shiva, V. (2004). The future of food: countering globalisation and recolonisation of Indian agriculture. Futures, 36(6-7), 715–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2003.12.014

- Shiva, V., Jafri, A. H., Emani, A., & Pande, M. (2000). Seeds of suicide. RFSTE.

- Smith, P., & Gregory, P. J. (2013). Climate change and sustainable food production. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665112002832

- Toenniessen, G., Adesina, A., & DeVries, J. (2008). Building an alliance for a green revolution in Africa. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.028

- United Nations. (2022). SDG Indicators—SDG Indicators. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=17&Target=17.15

- Walker, B., & Salt, D. (2012). Resilience thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world. Island Press.