?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Wheat is one of the cereal crops grown around the world, as well as in Ethiopia. However, female farmers are limited in their ability to achieve their estimated potential as a country in general and in the study area in particular. Even though Emba Alaje district is a potential area for bread wheat production in the Tigray region, so far studies have been scanty on female farmers’ adoption of improved bread wheat production. Thus, this study analyses the determinants of female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat production. This primary data was collected from 169 female farmers in Emba Alaje district using semi-structured interview schedules. A multi-stage sampling procedure was used to select representative samples. The data was analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics and econometric analysis. A binary probit regression model was used to analyze factors influencing the adoption of improved bread wheat varieties by female farmers. According to the model results, educational level, family labour, oxen ownership, training access, membership in cooperatives, and credit access positively influenced, while the age of the female farmers negatively influenced the adoption of bread wheat production by female farmers. Therefore, policymakers and other stakeholders should consider these factors to support female farmers in bread wheat production and to accelerate overall agricultural development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Agriculture is the basic means of livelihood for the majority of Ethiopians and women are the integral part of agricultural production. Yet, the performance of female farmers in agricultural production is constrained by different factors. To alleviate the common problem of rural women farmers, understanding the background reality is very necessary. Therefore, identifying different factors that affect the level of female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat production has a principal role. The female farmers’ adoption was determined by different social, economic and institutional factors. The result of the study will serve as a source of information for policymakers, researchers, extension workers, farmers and students who are directly or indirectly involved in women empowerment in agricultural production.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Agriculture is a basic means of livelihood in many developing countries across the world, including Ethiopia. It is the source of employment for more than 80% of the total population in rural areas of Ethiopia (Daniso et al., Citation2020). Ethiopia has a great endowment of natural resources. However, the nation has not properly benefited from its abundant natural resources, and agricultural development is still slow, which in turn has failed to record the desired economic development in the country (Abraham, Citation2015; Wassie, Citation2020).

The topic of gender and agriculture has gained a lot of attention in recent years among researchers and policymakers, especially in developing countries where gender inequality is persistent. In many developing countries, there is a gender gap in the agricultural sector because many women face gender-specific constraints that reduce their productivity and limit their contributions to agricultural production, economic growth, and the well-being of their families and communities (Mulema & Damtew, Citation2016; Tsige et al., Citation2020).

Wheat is among the leading cereal crops grown throughout the world and, similarly, is the major crop grown in Ethiopia from midland to highland agro-ecological zones. It ranks fourth after teff (Eragrostis teff), maize (Zea mays), and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) in area coverage and third in total production in Ethiopia (Ray et al., Citation2013; Tadesse et al., Citation2022).

Women are an integral part of farming households; they contribute more than 50% of the labour force for agricultural activities in many developing countries and bear most of the responsibilities to ensure household food security. However, except in a few developed countries, women’s efforts have not yet been realized by society (Harun, Citation2014; Shiferaw et al., Citation2014). In this regard, Boserup (Citation2014) strongly advocates that rural development in Africa cannot be imagined without the multidimensional and active participation of women. In the case of Ethiopia, although an effort has been made to address the issue of gender inequalities in agriculture, there is still a wide gender gap in the sector. The imbalanced gender relations create differences between men’s and women’s access to and control over resources, which has implications for the adoption of agricultural intensification technologies. The gender gap in Ethiopia’s agricultural productivity is 23% (Yadeta & Abashula, Citation2019).

While both male and female farmers are involved in wheat production in Ethiopia, the adoption of improved bread wheat variety (Triticum aestivum L.) is affected by factors related to his or her demographic characteristics, socio-economic factors, institutional factors, and technological factors. Deep-rooted gender inequalities due to the unfair distribution of resources and opportunities between men and women persist among rural Ethiopians who depend on agricultural production. For these reasons, men and women farmers cannot adopt the new agricultural technologies equally (Weldegiorges, Citation2015).

Thus, achieving gender equality has a key role in raising female farmers’ productivity via adoption of the latest farm technologies to the same level as that of male farmers’ and expanding their opportunities, which will in turn lead to reducing the incidence of food insecurity by ensuring fast economic growth in Ethiopia (Bekana, Citation2020).

However, in Ethiopia in general and the study area in particular, there is a wider gender gap in terms of access to and control over assets (i.e. land, livestock, credit, and inputs), access to extension and credit services, and overall farm technology adoption. Furthermore, policies, programmes, and projects pay slight attention to female farmers in their agricultural activities and often increase the existing inequalities between males and females (Azanaw & Tassew, Citation2017; Quisumbing et al., Citation2014).

Several studies were conducted on the issues of gender and agriculture in Ethiopia, such as Abenakyo and Elias (Citation2016), Achandi et al. (Citation2018), Assefa et al. (Citation2022), Buehren et al. (Citation2019), Firafis, Maja et al. (Citation2023) and Sherka (Citation2023), Seymour et al. (Citation2016). These studies analyze the gender-based constraints and opportunities for agricultural technologies adoption and overall intensification in Ethiopia.

More specifically, the study by Tsegamariam (Citation2017) on female-headed households (FHH) participation in teff production identified that education level; cultural barriers, religious taboos, economic status, and work load have significant influences on the level of FHH participation in teff production. The other study by Gebre et al. (Citation2019) indicates that the intensity of adoption of improved maize varieties is slower due to the effect of socio-economic factors on female headed households compared to male-headed households.

Furthermore, it is factual that the adoption decision of improved wheat varieties by smallholder farmers is influenced by different demographic, socio-economic, institutional, and psychological factors in different areas (Abda, Citation2022). Although the literature on the adoption of improved wheat varieties is vast, the majority of studies have looked at the factors that affect the joint decision made by male and female farmers, and little is known about the factors affecting adoption by female farmers. Particularly, the study area of Emba Alaje district is a potential area for bread wheat production in the southern Tigray region. However, the study has been scanty on female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat varieties. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to analyze the factors determining the adoption of improved bread wheat variety by female farmers in Emba Alaje district.

2. Research methodology

2.1. Description of the study area

This study was conducted in Emba Alaje district, located in the southern zone of Tigray regional state, Ethiopia. It is about 85 kilometers away from the capital city of Tigray Regional State, Mekelle. It has 20 rural and 1 urban Kebeles. The administrative center of this district is Adi- Shehu. The district contains a total population of 107,972, of whom 52,844 (48.9%) are men, 55,128 (51.1%) are women, and 7,568 are urban residents. The district contains a total of 24,784 households and a total of 22,457 hectares of cultivable land. For the land under cultivation in this district, 65.39% was planted in cereals, 24.94% in pulses, and 51 hectares in oilseeds; the area planted in vegetables is missing. The area planted with fruit trees was 57 hectares, while 32 were planted in Gesho. Approximately, 65.36% of the farmers used a mixed farming system (both crops and livestock), while 33.63% only grew crops and 1.0% only raised livestock (Gebrewahd et al., Citation2017).

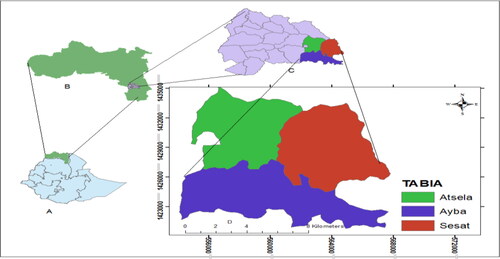

The study area has three agro-climatic zones, namely, Highland (dega), Mid Highland (woinadega), and Low Land (kolla), dominated by Highland (dega). The annual temperature ranges between 30 °C and 45 °C, with an average of 37.5 °C. The main rainy season extends from late June to early September. The distribution of the rainfall is, however, highly variable, untimely, and irregular in nature (Asqual, Citation2010) ().

Figure 1. Map of study area (Amba Alaje district).

Source: DLAO. (Citation2019).

2.2. Sampling techniques and sample size determination

The study used a multi-stage sampling procedure to select a representative sample. In the first stage, Emba-Alaje district and three kebeles (namely Atsella, Sesat, and Ayba) were selected purposefully by considering their great potential for wheat production. In the second stage, from the total list of female farmers, improved bread wheat adopter and non-adopter female farmers were stratified; in the third stage, from the stratified adopter and non-adopter female farmers, a total of 169 respondents were selected by simple random sampling techniques. This study determined an appropriate sample size by using Yamane’s (1967) formula as follows:

(1)

(1)

where

n = total sample size of the study

N= total female-headed households of the three kebele (Population size)

e = Confidence level (0.07)

According to the formula: the total sample size of this study was = 169 ().

Table 1. Proportional sample distribution for each Kebele.

After determining the total sample size, the researcher selects samples from three selected Kebeles by making them proportional to the sample population in each Kebele. Therefore, the following formula was used to make the sample size proportional to each kebele and between bread wheat adopter and non-adopter respondents:

(2)

(2)

where

ni - the sample to be selected from each selected ith Kebeles

Ni - the total population living in selected ith Kebele

ΣNi – The sum of total population in the selected three Kebeles

n – Total sample size

2.3. Data type and sources

For the purpose of attaining the research objectives, both quantitative and qualitative data were collected through primary and secondary data sources. Thus, the primary data was collected through a semi-structured interview schedule from 169 female farmers. The secondary data was collected from office reports, books, journal articles, unpublished documents, and other related papers.

2.4. Method of data analysis

2.4.1. Descriptive and inferential statistics

In this case, the researcher used descriptive statistics such as percentage, mean, and standard deviation to analyses the socio-economic characteristics of the sample household in the study area. Furthermore, inferential statistics such as the t-test and chi-square test were used to measure the associations between dependent and explanatory variables.

2.4.2. Econometric model specification

To analyze the determinants of female farmers’ adoption of improved bread wheat varieties, the researcher used econometric models. To select the model for analysis, understanding the nature of dependent and independent variables is the first step. In this study, the dependent variable was the female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). The nature of this dependent variable is dichotomous, and the independent variables are either continuous or categorical. Therefore, according to Gujarati (Citation2004), when the nature of the dependent variable is dichotomous, the researcher can use either a binary logit or probit regression analysis model. These two models (binary logit or probit) are appropriate to analyses the determinants of female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat varieties. In this study, binary probit regression was used to estimate the relationship between dependent and explanatory variables.

The probit model is represented as Prob where Φ indicates the cumulative standard normal probability distribution function. The probit model assumes that the function F (.) follows a normal (cumulative) distribution,

where φ (z) is the normal density function,

Marginal effects; in economics, the marginal effect or change is commonly used. The marginal change in binary regression model is computed as:

The probit model can be derived from a latent variable model, so Let y∗ be unobserved or latent variable determined by:

y = 1 if y∗>0 for adopter of bread wheat; y = 1, if y∗≤ 0 for non-adopter of bread wheat, where Yi is the latent dependent variable, which is not observed .Xi are vectors of variables that are expected to affect the probability of adoption of bread wheat. is a vector of an unknown parameters in the adoption equation. U1 is residuals that are independently and normally distributed with zero mean and constant variance.

2.5. Definition of variables and hypothesized relationship

2.5.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variables of this study were female farmers’ adoption decision on bread wheat varieties. The nature of the dependent variables (probability of female farmers’ adoption) is dummy so it takes one (1) if the farmer adopted bread wheat variety and otherwise it takes zero (0) if a farmer is did not adopted bread wheat variety.

As shwon in , To identify the factors determining the adoption of improved bread wheat varieties by female farmers the following independent variables were identified through intensive literature review and these variables was expected to affect the dependent variable.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Socio-economic characteristics of female household head farmers

Descriptive analysis: The association of socio-economic and institutional characteristics of female farmers with the adoption of improved bread wheat was tested by using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean) and inferential statistics, t-test and chi-square test. The data set contain 169 female farmers, from these 73 (43.2%) were bread wheat adopter whereas 96 (56.8%) were non-adopter of improved bread wheat varieties.

Age of female farmers: As shown in , the average age of adopters (43.8) was slightly lower than the average age of non-adopter (45) female farmers. Likewise the t-test value indicates that there was no significant mean difference between bread wheat adopter and non-adopter female farmers in the study area.

Family size: Adult family members are important source of labor force for agricultural production in the study area. The mean for family size of adopters (4.8) was greater than the mean (3.5) of non-adopter farmers. The t-test result also confirmed the existence of significant mean difference on the family size of bread wheat adopter and non-adopter female farmers at 1% significant level ().

Number of oxen ownership: In the study area in particular, as a country in general, oxen is considered as a main source of draught power for plowing the farm lands. The average mean for the number of oxen ownership was 3 for adopters’ female farmers whereas the mean score of Oxen was 2 for non-adopter female farmers. The t-test value also assured the mean difference between adopter and non-adopter was significant at 1% level of significance ().

Farm land size: Availability and accessibility of farm land is one of the basic determinants of farm technologies adoption. As shown in , the mean of land holding size of adopter female farmers was 0.59 hectare, while the mean of non-adopter female farmers was 0.32 hectare land size. The t-test result showed that there was significant difference in mean of cultivable land size between bread wheat adopter and non-adopter female farmers at 5% significance in the study area.

Table 2. The summary of the variables and their expected relationship.

Annual income of female household: As shown in , the average annual income of adopters was 42,497 (Birr), whereas the average annual income of non-adopter female farmers was 31,155 (Birr). This implies the household income has contribution on the adoption of bread wheat variety. The t-test value verifies the existence of average income difference between adopter and non-adopters at 1% significance level.

Table 3. Summary of t-test statistics for continuous explanatory variables.

Farming experience: Female farmers experience on wheat farming is considered as a determining factor on improved bread wheat adoption. The result of descriptive statistics also confirmed the existence of mean difference on the year of farming experience between adopter and non-adopter female farmer. The t-value also verifies the mean difference between the two groups was significant at 5% significant level ().

Distance to input market: As shown in the , the distance of input market from farmers’ residence was measured using the man walking hours. The result of t-value indicates that there was no significant mean difference between bread wheat adopter and non-adopter female farmers in the study area.

Educational level: It is expected that the educational level of farming household have positive effect on farmers’ technology adoption. From the total bread wheat adopter 15% illiterate, 13.7% able to read and write, 28.7% primary school, 32.8% secondary school, whereas from total non-adopter 45.8%, illiterate, 22.9% read and write, 18.7% primary school, and 12.5% secondary school. The result of chi-square test shows that there was a significant association between educational level of female farmers and bread wheat adoption at 1% level of significance in the study area ().

Table 4. Statistical summary of chi-square test for categorical explanatory variables.

Contact with development agents (DAs): Based on the survey result shown in , from total bread wheat adopter respondents, 65.7% had access to contact with development agents, on the other hand from total non-adopter respondents only 22.9% had access to contact with development agent. Hence, this indicates that female farmers who had frequent contact with development agents have better opportunity to adopt improved bread wheat. The Chi-square test result confirmed that there was significant association on frequency of DA contact and female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat verity at 5% significance level.

Training access: Providing training is expected to influence farmers’ adoption of various agricultural technologies. Similarly, in the study area training help female farmers by creating awareness on how to implement the full packages of bread wheat technologies. The descriptive result indicated that 94.2% of adopter female farmers had access to training services, whereas only 13.5% of non-adopter respondents accessed training services. The Chi-square test result revealed that there was significant association between household access to training and their bread wheat adoption status at 1% of significance level ().

Credit access: As shown in , from the total respondents 69.8% and 46.8% of bread wheat adopter and non-adopter female farmers, respectively, got access to credit services. The results of chi-square test show that there was a significant association on female farmers’ access to credit and adoption of improved wheat at 1% level of significance.

Membership to cooperatives: Female farmers’ membership with cooperative was expected as one of determinants of farmers’ technology adoption. The result of descriptive statistics reveled 86% of bread wheat adopter was member of cooperatives whereas only 11.4% of non-adopters where member to cooperatives. The Chi-square test indicates there is a significant association between cooperative membership and bread wheat adoption female farmers at 1% of significance level ().

Adoption status of neighbors household: in the rural area there is strong social relationship between neighbors’ household and these expected to influence the adoption of farmers on agricultural technologies. In the study area from the total respondents 43.8% had the neighbors with various farm technology adoptions, whereas 56.2% had neighbors with less or no farm technology adoption. Adoption status of neighbors had association on female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat variety at 10% significant level ().

Participation on off-farm activities: it is expected that female farmers may participate in off-farm activities as alternative source of income. In the study area 68.4% of bread wheat adopter were participate in another off-farm income generating activities, whereas 57.3% of non-adopters where also involved in other off-farm activities. The chi-square test result shows that there was no significant association between off-farm participation and bread wheat adoption by female farmers ().

3.2. Econometrics model result and discussion

3.2.1. Factors influencing female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat varieties

This section presents the result of econometric analysis by using binary probit regression model. Out of fourteen explanatory variables seven of them were identified as significant determinants of female farmers adoption of bread wheat production. These variables were age, educational level, family size, oxen ownership, credit access, training access, and membership to cooperative.

Age of FHH: the age of female farmers was considered one of the determining factors in the adoption of improved bread wheat varieties. As shown in , the age of female farmers negatively and significantly influenced the adoption of improved bread wheat varieties at 1% significant level. The estimated marginal effect also indicated that as the age of female farmers’ increases by one year, their probability of adopting a bread wheat variety decreases by 1.9%. This implies that as female farmers get older; their preference for adopting new farm technology will decline. This result contradicts with the finding that points out that the age of female farmers had a positive and significant influence on the adoption of improved bread meat variety (Haile, Citation2016).

Table 5. Result of binary probit for adoption of bread wheat varieties by female farmers.

Household size: Family size positively influenced the adoption of bread wheat varieties at a 5% level of significance. The marginal effect also indicates that, as the family size of female farmers’ increases by one, the probability of adoption of improved bread wheat variety increases by 11.9%, keeping other variables constant. Similarly, it has been found that the existence of active family members has a significant and positive effect on female farmers decisions to participate in teff production (Tsegamariam, Citation2017). This suggests that the female farmers that had a larger labour force had more capacity to participate than the female farmers that had no or a smaller family size. However, this result is contradicted by Almaz and Begashaw (Citation2019), who reported that the likelihood of adopting improved variety declines with increasing family size in the household.

Education level: The education level of female farmers has positive and significant influence in their probability of adopting improved bread wheat varieties at 5% level of significance. Specifically, as the educational level of female farmers increases by one grade, their adoption of bread wheat increases by 14.5%, keeping other variables constant (). This suggested that educated female farmers were more eager to participate than illiterate female farmers. This is due to the fact that women with higher educational levels have the opportunity to actively participate in any agricultural programme, which in turn raises their level of adoption of agricultural technologies. Female farmers’ educational level has constructive role on raising awareness of them about several farming technologies, so, their level of education is positively and significantly related to their adoption agricultural technology adoption (Gebre et al., Citation2019).

Number of oxen owned by FHH: The number of oxen had a positive and significant influence on the adoption of bread wheat varieties by female farmers at 5% significance level. This means those female farmers who had large numbers of oxen had more capacity to participate in bread wheat production compared to those who had no or fewer oxen. Moreover, the marginal effect implied that, as the number of oxen increased by one, the probability of female farmers adoption of improved bread wheat production increased by 23.4%, keeping other variables constant (). This is due to the fact that oxen power plays a vital role in crop production activities such as ploughing and threshing. This study is parallel with the study by Muez (Citation2014), which showed livestock holding had a positive effect on agricultural crop production. That means, the probability of adopting new variety is increased when they have oxen to plough the land.

Membership in cooperatives: Membership in local cooperatives positively influenced the adoption of female farmers in improved bread wheat production at 1% significance level. The survey also noted that as female farmers increased their membership in cooperatives, their level of participation in bread wheat production increased by 59.7% (). This study was in agreement with the finding by Neway and Zegeye (Citation2022), who point out that membership in cooperatives positively affected the adoption status of both male and female farmers. Thus, when the women farmers are participate in cooperative, they increase their probability of getting information related to adoption of wheat bread varieties.

Access to credit: Female farmers’ access to credit positively and significantly influenced the adoption of female farmers in the adoption of improved bread wheat varieties at 5% significance level. The estimated marginal effect noted that, as credit access increases by one, the probability of female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat production increases by 35.5%, keeping other variables constant (). This implies that female farmers who had taken credit were more likely to invest their credit in purchasing various agricultural inputs (improved crop varieties, fertilizer, herbicides, and pesticides). The result of this finding is in agreement with the study that reports the importance of credit access to facilitate the adoption of improved agricultural practices, especially for low income farmers who have limited financial capacity before harvest (Dessalegn et al., Citation2022).

Training access: The result of the probit model also shows that access to training positively and significantly influences the probability of adoption by female farmers at the 1% significance level. This means female farmers who had frequent access to training were more likely to adopt improved bread wheat varieties compared to female farmers with less or no access to training. The marginal effect estimation also confirms that as training access increases, the probability of female farmers adopting bread wheat varieties increases by 53% (). This result is in parallel with Gebre et al. (Citation2019), who reported the vital role of training access in improving maize adoption in southern Ethiopia.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

The main aim of this research was to analyze the factors determining the adoption of improved bread wheat varieties by female farmers in the Emba-Alaje district of Southern Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia. According to the result of the binary probit regression model, female farmers’ educational level, family labour, number of oxen owned, training access, membership in cooperatives, and credit access was positively and significantly influencing female farmers’ adoption of improved bread wheat varieties. While the model result also showed that the age of female farmers was negatively influencing their adoption of improved bread wheat varieties.

Based on the findings of this study, the following implications or recommendations can be drawn for further consideration and for improving female farmers’ participation in bread wheat production in the district in particular and in the country in general. The provision of training for female farmers had a significant influence on female farmers’ adoption of bread wheat production. Hence, extension agents and other stakeholders should give special attention to women during the planning and implementation of agricultural training and intervention programmes. Credit access had a positive effect on female farmers’ adoption of new agricultural technologies. However, most female farmers were afraid to take credit for agricultural production because of their agricultural failure and inability to repay the debt, so concerned stakeholders such as credit and saving institutions and agricultural officers should create clear awareness for women on how to use the credit to purchase agricultural inputs. Education level had a positive and significant effect on women’s adoption of agricultural technologies. Hence, to enhance the educational level of female farmers the district women’s affairs office and the educational sector should plan together to provide education by considering the living conditions of women farmers in the study area. Women farmers were impacted by an overload of domestic and farming work, and because of this, they are unable to access new agricultural information. Therefore, kebele extension workers and other stakeholders should design distinct plans to deliver information to female farmers. As a country in general and in the study area in particular, women’s adoption of agricultural technology was slow; therefore, policymakers and technology designers should consider gender-responsive policies and agricultural technologies in collaboration.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledged the support of the research assistants who helped in the data collection and the respondents in Emba-Alaje district for their collaboration and willingness for the interview.

Disclosure statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sinkie Alemu Kebede

Sinkie Alemu is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension at Mekdela Amba University, Ethiopia. She has an MSc in Rural Development from Mekelle University, Ethiopia. Sinkie Alemu research interests are mainly concentrating on the issues related to rural development studies, gender, food security, climate change, natural resource management, agricultural economics and agricultural extension.

Getasew Daru Tariku

Getasew Daru is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension at Mekdela Amba University, Ethiopia. He has an MSc in Rural livelihood and food security from University of Gondar, Ethiopia. His research areas of interest are food security, climate change, rural livelihood, gender, rural development, agricultural technologies, and extension.

References

- Abda, N. (2022). Adoption of improved wheat varieties by wheat producers in the bale zone of Ethiopia. International Journal of Agriculture Extension and Rural Development Studies, 9(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.37745/ijaerds.15

- Abenakyo, M., & Elias, D. (2016). Gender-based constraints and opportunities to agricultural intensification in Ethiopia: Systematic review. International Livestock Research Institute, Addis Ababa.

- Abraham, R. (2015). Achieving food security in Ethiopia by promoting productivity of future world food Teff: A review. Adv Plants Agric Res, 2(2) https://doi.org/10.15406/apar.2015.02.00045

- Achandi, E. L., Mujawamariya, G., Agboh-Noameshie, A. R., Gebremariam, S., Rahalivavololona, N., & Rodenburg, J. (2018). Women’s access to agricultural technologies in rice production and processing hubs: A comparative analysis of Ethiopia, Madagascar and Tanzania. Journal of Rural Studies, 60, 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.011

- Almaz, G., & Begashaw, M. (2019). Determinants of the role of gender on adoption of row planting of tef [Eragrostistef (Zucc.) Trotter] in central Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Science and Technology, 12(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejst.v12i1.2

- Asqual, B. T. (2010). Credit utilization and Repayment performance of members of cooperatives in Emba Alaje Woreda, Tigray, Ethiopia (Doctoral dissertation, Mekelle University), Mekelle, Ethiopia. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/4535

- Assefa, W., Kewessa, G., & Datiko, D. (2022). Agrobiodiversity and gender: the role of women in farm diversification among smallholder farmers in Sinana district, Southeastern Ethiopia. Biodiversity and Conservation, 31(10), 2329–2348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02343-z

- Azanaw, A., & Tassew, A. (2017). Gender equality in rural development and agricultural extension in Fogera District, Ethiopia: Implementation, access to and control over resources. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 17(04), 12509–12533. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.80.16665

- Bekana, D. M. (2020). Policies of gender equality in Ethiopia: The transformative perspective. International Journal of Public Administration, 43(4), 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1628060

- Boserup, E. (2014). The conditions of agricultural growth: The economics of agrarian change under population pressure. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315070360

- Buehren, N., Goldstein, M., Molina, E., & Vaillant, J. (2019). The impact of strengthening agricultural extension services on women farmers: Evidence from Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 50(4), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12499

- Daniso, B., Muche, M., Fikadu, B., Melaku, E., & Lemma, T. (2020). Assessment of rural households’ mobile phone usage status for rural innovation services in Gomma Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1728083. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1728083

- Dessalegn, B., Asnake, W., Tigabie, A., & Le, Q. B. (2022). Challenges to adoption of improved legume varieties: A gendered perspective. Sustainability, 14(4), 2150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042150

- DLAO. (2019). District lad administration office, GIS map service of Emba-Alaji District, Tigray, Ethiopia.

- Gebre, G. G., Isoda, H., Rahut, D. B., Amekawa, Y., & Nomura, H. (2019). Gender differences in the adoption of agricultural technology: The case of improved maize varieties in southern Ethiopia. Women’s Studies International Forum, 76, 102264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102264

- Gebrewahd, T. T., Meresa, A., & Kumar, N. (2017). Management practices and production constraints of central highland goats in Emba Alaje District, Southern Zone, Tigray, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 21(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4314/evj.v21i2.1

- Gujarati, D. (2004). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). Topics in Econometrics 15.Qualitative.

- Haile, F. (2016). Factors affecting women farmers’ participation in agricultural extension services for improving the production in rural district of Dendi West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Culture, Society and Development, 21, 30–41. www.iiste.org. ISSN 2422-8400

- Harun, M. E. (2014). Womens’ workload and their role in agricultural production in Ambo district, Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(8), 356–362. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2013.0546

- Maja, M. M., Idiris, A. A., Terefe, A. T., & Fashe, M. M. (2023). Gendered vulnerability, perception and adaptation options of smallholder farmers to climate change in Eastern Ethiopia. Earth Systems and Environment, 7(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-022-00324-y

- Muez, H. A. (2014). The Impact of Small-Scale Irrigation on Rural household Food Security: The case of Emba Alaje woreda [Doctoral dissertation]. Mekelle University: Mekelle, Ethiopia.

- Mulema, A., & Damtew, E. (2016). Gender-based constraints and opportunities to agricultural intensification in Ethiopia: A systematic review. ILRI project report.

- Neway, M. M., & Zegeye, M. B. (2022). Gender differences in the adoption of agricultural technology in North Shewa Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2069209

- Quisumbing, A. R., Meinzen-Dick, R., Raney, T. L., Croppenstedt, A., Behrman, J. A., & Peterman, A. (2014). Closing the knowledge gap on gender in agriculture. Gender in Agriculture, 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8616-4_1

- Ray, D. K., Mueller, N. D., West, P. C., & Foley, J. A. (2013). Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e66428. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066428

- Seymour, G., Doss, C., Marenya, P. P., Meinzen-Dick, R. S., & Passarelli, S. (2016). Women’s empowerment and the adoption of improved maize varieties: evidence from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, July 31 - August 2, 2016 http://purl.umn.edu/236164

- Sherka, T. D. (2023). Factors affecting women’s participation in soil & water conservation in Abeshege district Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2192455

- Shiferaw, B., Kassie, M., Jaleta, M., & Yirga, C. (2014). Adoption of improved wheat varieties and impacts on household food security in Ethiopia. Food Policy. 44, 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.09.012

- Tadesse, W., Zegeye, H., Debele, T., Kassa, D., Shiferaw, W., Solomon, T., & Assefa, S. (2022). Wheat production and breeding in Ethiopia: retrospect and prospects. Crop Breeding, Genetics and Genomics, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.20900/cbgg20220003

- Tsegamariam, D. (2017). Factors Affecting Teff Production by Female Headed Households in Abeshege Woreda of Gurage Zone, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region, Ethiopia [Doctoral dissertation]. Hawassa, Ethiopia.

- Tsegamariam. (2017). Factors Affecting Teff Production by Female Headed Households in Abeshege Woreda of Gurage Zone, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region.

- Tsige, M., Synnevåg, G., & Aune, J. B. (2020). Is gender mainstreaming viable? Empirical analysis of the practicality of policies for agriculture-based gendered development in Ethiopia. Gender Issues, 37(2), 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-019-09238-y

- Wassie, S. B. (2020). Natural resource degradation tendencies in Ethiopia: A review. Environmental Systems Research, 9(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-020-00194-1

- Weldegiorges, Z. K. (2015). Benefits, constraints and adoption of technologies introduced through the eco-farm project in Ethiopia [Master’s thesis]. Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Yadeta, M. G., & Abashula, S. G. (2019). Gender difference: decision making in agricultural production in Yayo district, south-western Ethiopia. ILIRIA International Review, 9(1).