?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study aims to present the economic impact of the production of local Geographical Indication (GI) products on producers based on the example of GI Kelkit sugar (dry) beans. Kelkit sugar beans, which are cultivated using local seeds, are legume products with white seeds and pink spots. Sugar beans grown around the Kelkit district of Gümüşhane were registered as a geographical indication product by the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (TPO) in 2020. This study seeks to answer the question of how the production of Kelkit sugar beans, which are mainly marketed with a geographical indication label, affects producer welfare. The target group of the research consists of farmers living in the Kelkit, Siran, and Kose districts of Gümüşhane who use GI-labelled seeds and do not use GI-labelled seeds in beans production. Propensity Score Matching was employed to determine the economic impact of the production of local geographical indication products on producers. The results indicate that the agricultural enterprises participating in the Kelkit sugar beans production program using geographical indication seeds have lower gross output and gross profit per unit area than those who did not participate in the program.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The production of geographical indication (GI) products is one of the most effective initiatives for rural development. As underlined by Cei et al. (Citation2018), GIs intend to achieve some goals: to provide credible information to buyers, to protect the cultural heritage of the locality, and to increase the value of local food, so growers’ income. Counting farmer welfare, countries look forward to positive outcomes on rural development, a difficulty that is considered to be fairly pressured for underdeveloped regions, where GIs can complete the gap with developed areas (Van Der Ploeg et al., Citation2000). Tregear et al. (Citation2007) highlighted the role of GIs in rural development in their study. They stated that GIs need to be considered as part of an expanded territorial strategy. In recent years, there has been an increasing concern in the agricultural sector to produce local or traditional products with quality assurance to overcome competitiveness; hence, growers can have a chance to differentiate their products, and the EU plans exclusive policy to support farmers in producing products with quality attributes (Requillart, Citation2007). These labels not only deliver the geographical origin of a product, but also systematize product attributes that ensure product quality too (Marion et al., Citation2023). Hence, quality requirements are not only conveyed but also registered too (Parra-López et al., Citation2015). In Europe, this quality attribute generally refers to many local factors such as climate, soil conditions, and human and cultural heritage (Cei et al., Citation2018). Moreover, Belletti et al. (Citation2007) pointed out with a case study of three GI products in their paper that there were some effective benefits of GIs besides economic issues, such as sustaining traditional methods and social mutual effects. Therefore, labelling applications like the GI can be identified as a list of attributes that combine farmer welfare, environment, sustainability, and transparency through all stages of production, processing, and distribution (Parra-López et al., Citation2015). Previous studies on the effects of the GI products on the economy have shown the high price advantage provided to producers through the production of differentiated GI products (Arıkan & Taşçıoğlu, Citation2019) and its contribution to the rural economy (Toklu et al., Citation2016). In this context, GI registration can provide economic gains to the farmer’s profitability target has an impact on the farmland farmers allocate to the production of GI sugar beans in their total cultivated lands, leading to regional development (Doğanlı, Citation2020).

In a progressively agro-industry and competitive agricultural food market, GI-labelled products can guarantee buyers of a more original, local, genuine, and high-quality food with high quality attributes (Broude, Citation2005) while tendering growers a chance to customize their products and may make good prices (Deselnicu et al., Citation2013). Previous studies on the effects of the GI products on the economy have shown the high price advantage provided to producers through the production of differentiated GI products (Arıkan & Taşçıoğlu, Citation2019) and its contribution to the rural economy (Toklu et al., Citation2016). In this context, the GI can provide economic gains to the farmer’s profitability target that has an impact on the farmland farmers allocate to the production of GI sugar beans in their total cultivated lands, leading to regional development (Doğanlı, Citation2020). Thus, one dimension of GI-labelled product effectiveness can be the price between a GI product and a non-GI product in the related market. A price premium can support GIs’ effectiveness, but it might not be an efficient criterion for GIs’ success, while price premiums can express higher production costs. In general, it might not be easy to draw overall results regarding the economic implications of GIs. Most GI-labelled products can earn important differentiation on price premiums; however, due to the related higher input costs and problems in marketing, it might not result in higher incomes for growers. Some contradictory empirical outcomes can be found in how producing GI-labelled products can contribute to farmer welfare. Any enterprise operating in a specific geographical area that produces GI product features is qualified to use GI labels to market its products (Marion et al., Citation2023). Enterprises generally implement certification of products, such as GIs, to provide market advantage and to build an image and fame as a supplier of products with exact specifications (Carriquiry & Babcock, Citation2007). Associations, cooperatives, municipalities, chambers, and exchanges in Turkey often apply for the GI label. The Turkish Patent and Trademark Office regulations offer an institutional atmosphere that encourages cooperation among stakeholders.

In this paper, we focus on GI-labelled food products in a province in the northeast of Turkey. Most of the products registered thus far in the province where this study was conducted were gastronomic products, for example Gümüşhane-dried fruit pulp (pestil), Gümüşhane bread, Gümüşhane sugar (dry) beans, Kürtün Araköy Bread (Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (TPO), Citation2022). After the application of Kelkit Sugar (Dry) Beans Producers Association in 2018, Kelkit sugar (dry) beans was registered as a GI product in January 2020. Before its application, extensive research has been conducted on the characterization of dry beans genotypes. Kelkit sugar beans is registered for its distinctive features compared to other sugar beans. It is cultivated in the Kelkit, Siran, and Kose districts of Gümüşhane province and is characterized by white seeds with pink spots on them. In recent years, the farmers in the region have been cultivating sugar (dry) beans using seeds that are procured from the neighboring provinces and have a higher yield, instead of the local Kelkit sugar beans seeds, which are popularly known as ‘pink eye’. Non-GI labelled sugar beans (traditional one) has different characteristics than sugar beans grown from local seeds, which have a pinkish color and elliptical grains (TPO, Citation2022).

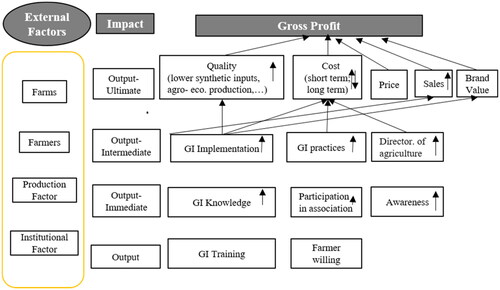

Most local farmers comply unsustainable cultivation practices in the study area, for instance excessive using synthetic inputs (e.g. pesticides and fertilizers) which have negative impacts for the environment and farming costs as well as for consumers. In order to prevent this kind of bottlenecks and promote sustainable agriculture practices, relevant stakeholders consider of GI production. In this point, the benefit of the GI production to the all the stakeholders especially to the local farmers can be explained by theory of change that explains understanding the theory underlying a programme approach is essential to understanding whether and how it works (Coryn et al., Citation2011). The success of GI-production is based on meeting the expectations of all the stakeholders like farmers, local authorities and the association at the same time. If one is not pleased especially the farmers, the market will not operate efficiently (Reddy, Citation2018). In this respect, a successful Kelkit Sugar Beans Association should encourage the member farmers through advantageous market price, timely payments, reducing transport costs and providing post-harvest services such as selection and packaging of the sugar beans. From the face to face interview it was clear that the association has a responsibility to do this. So, both the district directorate of agriculture that follow and keep the record of the GI-production and the association should be included the GI-labelled sugar beans production processes to support the local farmers. In this way, it should be easier to the Kelkit Sugar Beans Association convey the farmers’ needs to the district directorate or to the all market participants. The information is gathered on the product (e.g. GI-labelled production practices adoption) and eventual outcomes (e.g. farming costs) and on impact indicators (e.g. gross profit), designed in terms of theory of change. shows the theory of change behind the GI-labelled sugar beans production. It summaries farmers’ profitability, productivity and thus sales improve with the GI-labelled production, registration to the association and monitoring of the entire process by the district directorate of agriculture. According to the figure, there is also a possibility that GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans production may increase the costs. Because, being a member of the Kelkit Sugar Beans Association (dues payment and seed cost) may lead to increasing costs and also the whole production process is supervised by the district directorate of agriculture that means the farmers must use the certain inputs with the certain amount. On the other hand, production of GI-labelled sugar beans may decrease input costs. Because farmers sometimes use higher amount of the synthetic inputs to acquire higher productivity. Despite everything, this production method will increase the profitability and the efficiency of the farms in the long term.

Figure 1. Theory of Change: Showing a logic of GI-labelled sugar beans production to assess the profit effect (Source: Adopted from Pamuk et al., Citation2022).

There is a voluminous literature on GI-labelled products. However, the present literature mostly focuses on the size of the market for GI-labelled products and how GIs operate, so they also give a general perspective of the available sources in terms of framework and method. Only some studies used the primary goal of evaluating primary data. Török et al. (Citation2020) stated in their paper that the available GI literature paid attention to a specific viewpoint, such as buyers’ attitudes, geographical origin, or income implications. Although the amount of empirical research on the GI has increased, it seems that there is a gap in economic data to support GIs policies, especially in Turkey, where the GI system is still developing. In addition, the impact of the GI-labelled production practices on farmers as compared to non-GI is a topic that has not been extensively studied in Turkey.

The research question of this study is how to produce GI-labelled products as a tool for agricultural production in terms of economic issues. Regarding the economic impact of GI products, the following hypothesis is developed:

H1

The total farm land size of enterprises that grow dry beans is more effective in the cultivation of GI Kelkit sugar beans.

H2

The profit maximization target has an impact on the farmland that producers allocate to the cultivation of GI Kelkit sugar beans in their total cultivated land.

H3

The gross production value per decare in dry beans cultivation is higher in GI cultivation.

H4

The gross profit per decare in dry beans cultivation is higher in GI cultivation.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data

Primary data were obtained from face-to-face surveys with the farmers producing sugar (dry) beans. The target group of the research consists of farmers living in the Kelkit, Siran, and Kose counties of Gümüşhane province, and in their villages, who produce GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans and do not produce GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans in their production. Information on the farmers producing dry beans was obtained from the Kelkit, Kose, and Siran District Directorates of Agriculture and Forestry. The survey questions were prepared in a way that would fulfil the purpose of the research and in accordance with the method that would be used in data analysis.

The Kelkit Sugar Beans Association’s contact number, GI registration certificate, name list of the farmers who produce GI-labelled sugar beans, their mobile numbers, and addresses were obtained after a meeting with Gümüşhane Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry. After that, the district agricultural directorates included in the scope of this research were visited. District agricultural managers were informed about the purpose and target group of the research. As a first step, each farmer was called from the list through the district agricultural manager, and the aim of the study was briefly stated on the phone. According to the farmer’s positive statement, a face-to-face interview was arranged on the appropriate day and the time that was suitable for them. If the farmer stated that he would not participate in the face-to-face interview, the next farmer on the list was contacted. In order to reach as many farmers as possible, telephone calls also included information about the farmers who grow traditional sugar beans (Non-GI). Aforementioned procedure was also applied to non-GI farmers. After verbal approval between the agricultural manager and the farmer on the phone, the day and hour that were suitable for the participant were determined. Face-to-face interviews were conducted according to the determined day and the hour in a permitted room in district directorates. However, some were conducted in village tea houses for the farmers who could not come to the district directorate. Informed Consent was obtained from all the participants for this study.

Snowball Sampling, a nonprobability sampling method, was used in this study. Non-Probability Sampling techniques are frequently used, particularly in qualitative and field studies (Taherdoost, Citation2016). Research that includes qualitative and field-based data tends to work on small samples and thereby examines real facts rather than making inferences based on a large population (Yin, Citation2003). In the study conducted by Breweton and Millward (Citation2001) was reported that the Snowball Sampling Method is a very suitable method, especially for the target group that is difficult to reach, located in dispersed locations, and does not tolerate face-to-face survey interviews. In this regard, no random sampling technique was used in the population representing the target group of this study.

The sample size of this study was the number of non-GI farmers (50) as well as the number of farmers cultivating GI- labelled Kelkit Sugar Beans (50). Face-to-face interviews with 100 farmers were held in January, February, and March 2021.

There were some restrictions for this research at the time the surveys have been done. The data has been obtained from the participants for only 2020-2021 production seasons. In the survey time (Jan-Feb-March, 2021) the GI registration of the sugar beans, which was registered in January 2020, was very new and the numbers of the members in the association was very low. In addition, the farmers’ post-harvest process in two production season encountered the Covid-19 pandemic.

2.2 Analysing method

Statistical analyses were conducted to the test whether there was a difference between the enterprises, and Normal Distribution was tested for continuous variables using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Based on the results of this test, a t-test was conducted for variables with a normal distribution, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for the remaining variables. The data obtained by counting were compared using the chi-squared test. The research method involved a comparison of farmers who used geographical indication seeds and those who did not to calculate the economic impact of geographical indication. Propensity score matching was used as the analysis method. This method was intended to measure the extent to which geographical indication improves farmers’ income. As a function of observable features, the propensity score is estimated using Logit or Probit regression (Kirui & Njiraini, Citation2013). In the second step, two balanced groups with similar propensity scores were formed based on the predicted propensity scores (Jena et al., Citation2012). In other words, farmers who produce GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans (intervention group) are matched with farmers who produce beans using other seeds (comparison or control group) and have a similar propensity score. After the matching was completed, the impact of the intervention (average impact of the program) was estimated by taking the difference in the average output values of the matched groups. The average effect of a program on those who participated in the program, also known as the average effect of treatment on the treated (ATT) was calculated using the following equation:

where D denotes the status of individuals who participated and did not participate in the program, that is, those producing beans using GI seeds and those producing beans using other seeds (D = 1 if individuals participated in the program, and D = 0 if they did not). Y1 denotes the output obtained in the case of participation in the program and Y0 denotes the output obtained by those who did not participate in the program. The output is based on the gross output value and gross profit generated from sugar beans production. The variables used to compare the enterprises that produce and do not produce GI Kelkit sugar beans are listed in .

Table 1. Variables compare enterprises.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Gross profit in sugar beans cultivation

Gross profit analysis, one of the methods used to measure the success of business activities, was carried out for sugar (dry) beans production, which is the main field of activity of the surveyed enterprises. To measure gross profit, enterprises’ variable costs per decare incurred were calculated. The variable costs per decare of enterprises producing GI-labelled sugar beans and those not producing GI-labelled sugar beans are shown in . As for the distribution of variable cost items in total variable costs, hired labor costs have the highest share at 58.01%. These are followed by fertilizer (16.76%), miscellaneous variable costs including packaging (9.95%), water and electricity (5.75%), fuel (5.47%), and pesticide (3.96%) costs. Berk and Güngör, (Citation2016) found that the inputs that were used extensively in dried beans production with a huge impact on production value were labor, seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. The study conducted by Efeoğlu et al. (Citation2016) reported that the major input cost in the production of GI Ispir sugar beans was labour cost, and that the producers incurred excessive labor costs, as the majority of them worked in production together with their spouses and children. However, the study conducted by Ayçiçek and Karakaya (Citation2022) found that harvesting and hoeing costs had the highest share among the variable costs in dry beans production.

Table 2. Variable costs per decare and their distribution.

Variable costs per decare incurred by GI-enterprises and non-GI enterprises were found to be 1,530.53 TRY ($180.06) and 2,200.95 TRY ($258.94) respectively, with an average value of 1,857.76 TRY ($218.56). Accordingly, it is seen that those who did not produce GI Kelkit sugar beans incurred higher variable costs per decare than those who did. In their study involving the economic analysis of dried beans producers, Ayçiçek and Karakaya (Citation2022) found an average variable cost of 1,447.43 TRY ($102,65), which is similar to the findings of this study. The Mann-Whitney U-test also confirmed that this difference was statistically significant.

In particular, there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of hired labor, fertilizer, and water/electricity costs. Farmers who want to cultivate GI Kelkit sugar beans first become members of the Kelkit Sugar Beans Association and are registered by the District Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry and supervised regularly during the cultivation periods. In this regard, inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and water used by the GI farmers are used in a controlled manner. However, farmers who are not members of the association and cultivate traditional dry beans use uncontrolled inputs, such as pesticides and fertilizers, to increase productivity and yield. Therefore, this situation increases variable costs. Therefore, the variable costs of farmers cultivating non-GI dry beans were found to be higher in this study.

Gross output per decare by enterprises for GI and non- GI producers was found to be 3,242.23 TRY ($381.44) and 4,586.18 TRY ($539.55), respectively, with an average value of 3,920.99 TRY ($461.29) (). Accordingly, it is seen that those who did not produce GI-labelled sugar beans had higher gross output per decare than those who did. This difference is statistically significant according to the Mann-Whitney U test. Gross profit per decare by enterprises that produce and did not produce GI-labelled sugar beans was found to be 1,712.70 TRY ($201.49) and 2,385.23 TRY ($280.62), respectively, with an average value of 2,063.23 TRY ($242.73). Accordingly, those who did not produce GI sugar beans had higher gross profit per decare than those who did.

Table 3. Gross output, variable costs and gross profit.

The results of the Mann-Whitney U test indicated that this difference was statistically significant. The studies conducted by Ayçiçek and Karakaya (Citation2022) and Üçpınar (Citation2016) found that the gross profit per decare from dry beans production was 1,339.33 TRY (94.71$), 1,347.42 TRY (389.35$) respectively. These values were lower than the gross profit values obtained in this study.

3.2. Economic impact of GI dry beans cultivation on enterprises

This section focuses on the economic impact of geographical indication by comparing the farmers that produce sugar beans with geographical indication labelled and those who do not produce GI-labelled beans. Propensity Score Matching was used as the analysis method. This method measures the extent to which the use of GI seeds improves gross output and profit. The descriptive statistics of the variables used to compare GI and non-GI enterprises are given in .

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of variables for comparing enterprises.

A statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of the share of dry beans in total cultivated land, gross output per decare, and gross profit per decare. As mentioned in the previous section, those who did not produce GI sugar beans had higher gross output per decare and gross profit per decare than those who produced GI dry beans ( and

rejection). In terms of the share of the sugar beans in the total cultivated land, the GI farmers were found to have a higher share (35.46%) than the non-GI farmers (30.14%). This study is based on data obtained for the production periods of 2020 and 2021 for both producer groups (GI and non-GI). According to the data obtained from face-to-face interviews, the expected yield from beans production could not be obtained in the harvest period of 2020 because of the drought in the region and the inability of some farmers to irrigate their land adequately. Therefore, 15 out of the 50 GI farmers did not cultivate beans during the production period of 2021. Among the non-GI beans producers, only five did not cultivate beans during the production period of 2021. Moreover, the beans market in Turkey was significantly affected by lockdowns during the production period of 2020. Due to falling prices, most Kelkit sugar beans producers did not sell their beans and stored them, so they did not plant beans in the production period of 2021. As mentioned by Direk et al. (Citation2002), irrigation is crucial for beans quality and yield. During beans growth, irrigation should be performed at least four to five times, and the amount of water to be delivered to the field should be controlled until the flowering phase. This finding partially can explain the low yield of beans producers that participated in the study in both production periods due to drought in the region. As stated in Tugay’s (Citation2012) study, low crop yield is a major agricultural production issue in Turkey. This has become a major concern for the small-scale farmers in the region. However, improved beans seeds have a high yield, which is one of the reasons why the small-scale farmers use them. As noted in the study by Çiftçi et al. (Citation2013), the physical and genetic impurities in the beans population result in various problems in its cultivation and marketing. Therefore, there is a need for high-yield and high-quality varieties that are adapted to this region. Local populations that need to be improved for this purpose are of great importance (Önder et al., Citation2012).

For the small-scale producers that obtain low yields, planting during the next production period becomes a problem (Birachi et al., Citation2011). According to the findings obtained by Özüdoğru et al. (Citation2016) from their study on sustainability of agricultural products, the major factor that the farmers consider when cultivating agricultural products is the price. This finding is consistent with that of the present study. Owing to the outbreak in the production period of 2020, the farmers participating in the study could not find the buyers for their beans and had to sell them at prices lower than the expected prices. The findings indicate that this may affect both the beans cultivation areas and the output in the production period of 2021. In some studies measuring the impact of GI products on farm income using the Propensity Score Matching method (Poetschki et al., Citation2021; Sitorus et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021), ATT values were found to be positive or negative, meaning that if all enterprises had participated in the program involving GI farmers, their gross income or net income would have been positive or negative.

Requillart (Citation2007) undertook research on the economics of GIs in Europe and found that, in some cases, one of the prominent purposes of GIs in the EU is to boost farmers’ welfare economically and to maintain small-scale farmers in undeveloped areas. A research was done by Chatellier and Delattre (Citation2003) pointed out that the GI-milk production is more fruitful in the mountainous area of Alpes than the non-GI milk in France, and GI milk price premium was found higher at 15-30%. The income of GI milk producers was compatible with the income of non-GI milk producers. From this result, it is understood that the higher the price of GI-milk, the higher the cost of production. According to this study, GIs can be a tool to provide a higher price for producers, and the higher GI-milk price can cover additional costs because of the less favoured area (mountainous area). In contrast, a study by ETEPS (Citation2006) in the GI-labelled product case (Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, Italy) indicates that milk producers earn zero or negative profits when they sell their milk to private firms, and this study recommends that if the producers deliver the milk to producer associations, cooperatives may benefit more profits. Regarding this result, it could be said that in this study, farmers who engage in the GI production are faced with negative financial outcomes. It should be noted that in the long run term, the higher price premium for GI sugar beans can cover the variable costs, which will reflect the income of GI farmers.

The ATE and ATET values calculated for gross output per decare in the STATA 14 package program using the Propensity Score Matching method are shown in . The ATE and ATET values were statistically significant at the 1% level. The ATE value indicates how the gross output would have changed if all enterprises included in the research had participated in the GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans production program. Accordingly, if all of the enterprises had participated in the GI-labelled Kelkit Sugar Beans production program, they would have achieved 1,417.69 TRY ($166.78) less gross output value per decare on average. The ATET value, on the other hand, indicates how the gross output (gross income) per decare of the enterprises participating in the GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans production program would have changed if they had not participated in the program. According to the results given in , the enterprises that participated in the GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans have a gross output per decare (gross income) that is 1,289.54 TRY ($151.45) lower than the amount they would have otherwise achieved if they had not participated in the program. A study conducted by Wang et al. (Citation2021) on the economic impact of GI rice production on small-scale farmers compared farmers who were members of a producer association and used GI seeds with farmers who were not members of any association, based on 2015 data. The results indicated that the gross revenue of the enterprises that were members of the association (6.17 million VND, $308) was lower than that of the non-member enterprises (9.27 million VND, $463). The authors reported that this result might be related to the marketing strategies of the producers during the relating period. A different result was obtained in a study on GI white pepper farming by Sitorus et al. (Citation2020). The gross revenue of the GI white pepper producers that participated in the study (47.9 million/ha) was higher than that of those who did not (32.9 million/ha).

Table 5. ATE and ATET values by gross output.

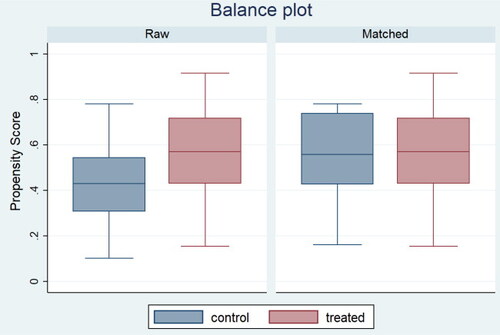

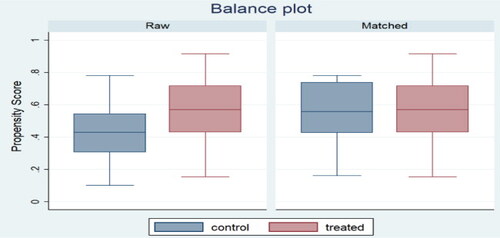

The balance plot, which is used to show the similarity of the propensity scores used in the comparison of the enterprises in terms of gross output per decare, indicates that the matched samples are similar (). Çobanoğlu and Yılmaz, (Citation2020) note that if the matched sample box plots are the same according to the intervention levels, the covariate is balanced in the matched sample.

The ATE and ATET values calculated for gross profit per decare in the STATA 14 package program using the Propensity Score Matching method are shown in . The ATE and ATET values were statistically significant at a significance level of 1% and 5%. As mentioned above, the ATE value indicates how the gross profit would have changed if all enterprises included in the research had participated in the GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans production program. Accordingly, if all enterprises had participated in the GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans production program, they would have generated 1,068.83 TRY ($125.74) less gross profit per decare on average. In a similar study, however, Sitorus et al. (Citation2020) found that if all of the farmers that participated in the study had produced GI white pepper powder, they would have achieved 1175 kg/ha more output on average. They further noted that this productivity would contribute to their gross profit. Another study conducted by Poetschki et al. (Citation2021) on the impact of geographical indication products on farmer income found that if all farmers had produced geographical indication products, they would have earned (ATE) €157,955 more net income on average. This finding suggests that geographical indication products have a huge impact on net operating income. The ATET value, on the other hand, indicates how the gross profit per decare of the enterprises participating in the Kelkit sugar beans production program using geographical indication seeds would have changed if they had not participated in the program. According to the results given in , the enterprises that participated in the Kelkit sugar beans production program using geographical indication seeds have a gross profit per decare that is 1,031.49 TRY ($121.35), lower than the amount they would have otherwise generated if they had not participated in the program.

Table 6. ATE and ATET values by the gross profit per decare.

The balance plot, which is used to show the similarity of the propensity scores used in the comparison of the enterprises in terms of gross profit per decare, indicates that the matched samples are similar (). Box plots show that the propensity scores were generally balanced.

4. Conclusion

The goal of this study was to identify the economic factors relevant to the adaptation of GI-labelled Kelkit sugar beans by the farmers in the research area. The economic factors identified in this study are gross production value per decare, gross profit per decare, and gross income. There are several reasons why enterprises participating in the program achieved lower yields than those that did not participate. The enterprises participating in the program carry out production according to the requirements of geographical indication specifications. These requirements include the use of the local Kelkit sugar beans seeds, other applications (soil preparation, planting, vegetation, harvest, and packaging), fertilization and diseases and pest management under the coordination of the Kelkit Sugar Beans Producers Association and under the supervision of the Kelkit District Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry. Enterprises that did not participate in the program adopted different production practices, including the use of beans seeds other than local beans seeds, intensive use of inputs in production, and no supervision of production. Thus, it is not surprising that enterprises that did not participate in the program achieved higher yields than those that did, particularly because of the intensive use of inputs. However, it is possible to say that the yield difference between the enterprises that participated in the program (142.98 kg/da) and those that did not (181.12 kg/da) is not very high.

As stated before, Kelkit sugar (dry) beans was registered as a GI product in January 2020. Given this information and the year of the data collected (2020-2021), it is likely that the benefits cannot be estimated in terms of price, income, and return on GI-labelled production in a short period. We cannot disregard this issue in the research, and it can be included as a research limitation of this study. However, further research on this matter can be conducted to determine the benefits of the production of GIs products, especially in rural areas. Turkey has thousands of local products owing to its geographical conditions. In recent years, non-governmental organizations, municipalities, and associations have obtained the geographical indication of local and traditional values, increasing the added value of these local products and gaining commercial value. In Turkey, 40% of the 734 geographical indications, whose application process is still in progress, are owned by NGOs. Only 13 geographical indications for Turkey are registered in the European Union (TPO, 2023). Therefore, to determine its effectiveness, especially in the research area, new studies must be conducted.

The results highlight that the level of adaption of GI-labelled sugar beans is not high in general when considering the low number of GI farmers and the economic results of this study. The negative economic outputs of GI-non Kelkit Sugar Beans seem to result from unfavorable experiences specific to that production period, such as pandemic lockdowns, drought, low selling prices, storing excess beans, and decreasing in sowing areas in 2020-2021. Moreover, the adoption of GIs is not only related to the implementation of better cultivation practices but also to marketing practices, since in general, the former are already prevalent in the research area. The results provide multiple policy and management implications for enhancing economic viability by increasing the spread of GIs and improving the practices implemented by GIs enterprises. Key inferences are: 1) the high importance of developing training programs for producers based on demonstrations of successful GI enterprises, with NGOs and local authorities playing a key role; 2) the need for further research to prove that the costs associated with GI can be recovered in the medium to long-term; 3) the importance of enhanced efforts to promote awareness of GIs among producers; 4) the importance of GI sugar beans for creating, in addition to just geographical origin, new added values that are increasingly demanded in the EU and international markets, such as sustainability and environmental dimensions; and 5) the need to develop new marketing strategies based on producer-customer combinations, and establishing more robust methods of collective organization and collaboration in the initial stages of the adoption of GI products.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge that this research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Gümüşhane University Ethics Committee Number was 2021/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [ND]. The data are not publicly available due to [restrictions e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arıkan, M., & Taşçıoğlu, Y. (2019). Coğrafi işaretli ürünlerin kırsal alana olan etkilerinin üreticiler açısından belirlenmesi: Finike portakalı örneği. Mediterranean Agricultural Sciences, 32, 1–12.

- Ayçiçek, M., & Karakaya, E. (2022). Bingöl ili kuru fasulye üreten işletmelerin mevcut durumu ve ekonomik analizi. Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 17(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.54975/isubuzfd.1172761

- Belletti, G., Burgassi, T., Marescotti, A., & Scaramuzzi, S. (2007). The effects of certification costs on the success of a PDO/PGI. Quality Management in Food Chains (pp. 107–121). Wageningen Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-605-2.

- Berk, A., & Ve Güngör, C. (2016 Türkiye’de baklagiller üretiminde teknik etkinlik: Kuru fasulye örneği [Paper presentation]. XII. Ulusal Tarım Ekonomisi Congress, 25-27 May, 2016, Isparta-Turkey. 97–104.

- Birachi, E. A., Ochieng, J., Wozemba, D., Ruraduma, C., Niyuhire, M. C., & Ve Ochieng, D. (2011). Factors influencing smallholder farmers’ beans production and supply to market in Burundi. African Crop Science Journal, 19, 335–342.

- Breweton, P., & Millward, L. (2001). Organizational research methods: A guide for students and researchers. (p. 196). SAGE.

- Broude, T. (2005). Taking “trade and culture” seriously: Geographical indications and cultural protection in WTO Law. Journal of International Economic Law, 26, 624–692.

- BÜMKO. (2021). Average exchange rates. ministry of treasury and finance of The Republic of Turkey. Retrieved June 10, 2021, from http://www.bumko.gov.tr/TR,147/ekonomik-gostergeler.html

- Carriquiry, M., & Babcock, B. A. (2007). Reputations, market structure, and the choice of quality assurance systems in the food industry. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 89(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2007.00959.x

- Cei, L., Defrancesco, E., & Stefani, G. (2018). From Geographical indications to rural development: A review of the economic effects of European Union policy. Sustainability, 10(10), 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103745

- Chatellier, V., & Delattre, F. (2003). Dairy production in the French mountains: a particular dynamic for the Northern Alps. INRAE Productions Animales, 16(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2003.16.1.3645

- Çiftçi, V., Kulaz, H., Çirka, M., & Ve Yıldız, E. (2013). Doğu Anadolu’nun güneyinde yetiştirilen kuru fasulye genotiplerinin toplanması ve değerlendirilmesi [Paper presentation]. Türkiye 10. Tarla Bitkileri Kongresi, 10–13 Eylül, 2013, Konya-Türkiye (pp. 870–876).

- Çobanoğlu, F., & Ve Yılmaz, H. İ. (2020). Stata Uygulamalı Etki Değerleme Analizleri. Sonçağ Akademi, 1. Baskı, ISBN: 978-625-7918-79-4, Yayın no: 798, Ankara.

- Coryn, C. L., Noakes, L. A., Westine, C. D., & Schröter, D. C. (2011). A systematic review of theory-driven evaluation practice from 1990 to 2009. American Journal of Evaluation, 32(2), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010389321

- Deselnicu, O. C., Costanigro, M., Souza-Monteiro, D. M., & McFadden, D. T. (2013). A meta-analysis of geographical indication food valuation studies: What drives the premium for origin-based labels? Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 38(2), 204–219.

- Direk, M., Bayramoğlu, Z., & Ve Paksaoy, M. (2002). Konya ilinde fasulye üretiminde karşılaşılan sorunlar ve çözüm önerileri. S.Ü Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 16, 21–27.

- Doğanlı, B. (2020). Geographical indication, branding and rural tourism relations. İnsan Ve Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 3(2), 525–541.

- Efeoğlu, R., Aydemir, A. F., & Ve Emsen, Ö. S. (2016). İspir fasulyesinin üretim-piyasaya arz süreçlerinde karşılaşılan sorunlar ve çözüm önerileri. Atatürk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 20, 985–1002.

- ETEPS. (2006). Economic Assessment of the food quality assurance schemes – Synthesis report.

- Jena, P. R., Beyene, B., Stellmacher, T., & Grote, U. (2012). The impact of coffee certification on smallscale producers’ livelihoods: A case study from the Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 43(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2012.00594.x

- Kirui, O. K., & Njiraini, G. W. (2013). Impact of collective action on the smallholder agricultural commercialization and incomes: Experiences from Kenya [Paper presentation]. 4th Conference of AAAE, 22-25 September, 2013, Hammamet, Tunisia (pp. 1–12).

- Marion, H., Luisa, M., & Sebastian, R. (2023). Adoption of Geographical indications and origin-related food labels by smes – A systematic literature review. Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy, 4, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcb.2023.100041

- Önder, M., Ateş, M. K., Kahraman, A., & Ve Ceyhan, E. (2012). Konya ilinde fasulye tarımında karşılaşılan problemler ve çözüm önerileri. Tarım Bilimleri Araştırma Dergisi, 5, 143–148.

- Özüdoğru, T., Miran, B., Yavuz, G. G., & Ve Hasdemir, M. (2016 Türkiye’de seçilmiş ürünlerin üretiminde sürdürülebilirlik [Paper presentation]. XII. Ulusal Tarım Ekonomisi Dergisi, 25–27 May, 2016, Isparta-Turkey. 105–114.

- Pamuk, H., Motovska, N. M., & van Rijn, F. C. (2022). Towards sustainable cotton farming: Validating the impact of Better Cotton on cotton farmers in India, Endline report. Wageningen University & Research.

- Parra-López, C., Hinojosa-Rodríguez, A., Sayadi, S., & Carmona-Torres, C. (2015). Protected designation of origin as a certified quality system in the Andalusian olive oil industry: Adaption factors and management practices. Food Control. 51, 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.11.044

- Poetschki, K., Peerlings, J., & Dries, L. (2021). The impact of geographical indications on farm incomes in the EU olives and wine sector. British Food Journal, 123(13), 579–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2020-1119

- Reddy, A. A. (2018). Electronic national agricultural markets. Current Science, 115(5), 826–837.

- Requillart, V. (2007). On the economics of geographical indications in the EU. In Geographical Indications, Country of Origin and Collective Brands: Firm Strategies and Public Policies workshop, Toulouse School of Economics (GREMAQ-INRA & IDEI), Toulouse, June (pp. 14–15).

- Sitorus, R., Harianto, S., & Syaukat, Y. (2020). Propensity score matching to analyse the impact of implementing good agricultural practices on white pepper farming in Bangka Belitung Islands province. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, 19, 207–213.

- Taherdoost, H. (2016). Sampling methods in research methodology; How to choose a sampling technique for research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management (IJARM), 5(2), 18–27.

- Toklu, T. T., Ustaahmetoğlu, E., & Öztürk-Küçük, H. (2016). Tüketicilerin coğrafi işaretli ürün algısı ve daha fazla fiyat ödeme isteği: Yapısal eşitlik modellemesi yaklaşımı. Yönetim Ve Ekonomi, 23, 147–155.

- Török, Á., Jantyik, L., Maró, Z. M., & Moir, H. V. J. (2020). Understanding the real-world impact of GIs: A critical review of the empirical economic literature. Sustainability, 12(22), 9434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229434

- Tregear, A., Arfini, F., Belletti, G., & Marescotti, A. (2007). Regional foods and rural development: the role of product qualification. Journal of Rural Studies, 23(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.09.010

- Tugay, M. E. (2012). Türk tarımında bitkisel üretimi artırma yolları. Tarım Bilimleri Araştırma Dergisi, 5, 01–08.

- Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (TPO). (2022). Geographical indication. Retrieved May 29, 2022, from https://ci.turkpatent.gov.tr/sayfa/co%C4%9Frafi-i%C5%9Faret-nedir

- Üçpınar, F. (2016). Konya ili Derbent ilçesi taze fasulye üretimi yapılan tarım işletmelerinin ekonomik analizi [Master’s thesis]. Selcuk University Institute of Science.

- Van Der Ploeg, J. D., Renting, H., Brunori, G., Knickel, K., Mannion, J., Marsden, T., De Roest, K., Sevilla‐Guzmán, E., & Ventura, F. (2000). Rural development: From practices and policies towards theory. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(4), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00156

- Wang, H., Anh, D. T., & Moustier, P. (2021). The benefits of geographical indication certification through farmer organizations on low-income farmers: The case of Hoa Vang sticky rice in Vietnam. Cahiers Agricultures, 30, 46. https://doi.org/10.1051/cagri/2021032

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research, design and methods. SAGE.