?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Despite the clear synergy between food security and politics, economic policy frameworks have not given adequate attention to the political economy of income diversification as a means of improving food security. To determine the drivers of rural income diversification for enhancing food security in Ghana, the study analyzed the income diversification activities of 500 rural households using cross-sectional data. Results from the Count index, Simpson’s diversification index (SDI), Tobit, Poisson and multiple linear regression, revealed that the long-term income diversification measure proxied by the Number of Economic Activities (NEA), undertaken by rural households ranged from 1 to 10. Moreover, using the short-term income diversification measure, the Simpson diversification index, averaged 79.6% with a range of 41% to 89%. The findings suggest that the average NEA required to improve food security in Northern region was 7. Although total expenditure on food increased with increasing SDIs, diversification beyond 89% led to a decline in food security. The relationship between income diversification and the age of respondents also resembled a U-shaped curve implying that age impacts negatively on income diversification opportunities in the initial stages. A possible explanation is that people below a certain age are predominately dependent on relatives for their economic livelihoods. However, once they reached a certain age or turning point, there was increasing income diversification. Technical education was found to be the most important variable affecting the Simpson Index with a standardised parameter value of 1.171, which was three times more influential in diversification than its nearest rival variable, formal education (0.330).

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

This article considers the field of sustainable livelihoods of agricultural households and income diversification as the main subject of its study. One of the major issues to be investigated in this field is the political economy analysis of rural household income diversification for food security. Although the analysis of income diversification of rural households is not a particularly new concept, it is one of the earliest strategies of resource optimization for improved food security among farming households (Gebiso et al., Citation2023). Since the popularization of the concept, it has been variously used by development economists to underscore the relevance of non-farm incomes to rural households seeking to improve food security in stressful seasons (Adem et al., Citation2018). Income diversification is linked to the fact that very few households earn all their income from a single source (Bitana et al., Citation2023). Rural households earn income from multiple sources including farm and non-farm sources (Beriso et al., Citation2023). For many households, diversified incomes from non-farm sources contribute an important share of the total household income essential for buying food in the lean season (Sisay, Citation2024). Income diversification helps to boost farmer resilience against disasters by insuring households against climate variability, natural disasters, and other extreme weather events. Even though income diversification leads to major welfare indicators such as poverty reduction and food security, developing rural people’s resilience against food insecurity has proved a major challenge for transitional economies undergoing various forms of economic crises accentuated by the covid-19 pandemic (Salifu & Salifu, Citation2023).

Today it is reported that over 928 million people, or over 12% of the global population, are food and nutritionally insecure (FAO & UNICEF, 2021). It means that the majority of these populations skipped meals during the day or went to bed without eating. Based on the latest global statistics of the World Food Programme (WFP) on food insecure populations, the number of people suffering from severe food insecurity is increasing daily and projected to go up by 8.9% by 2030, if current food security policies fail to eradicate food insecurity among poor populations. Majority of this population are rural householders engaged in smallholder farming. Within the global framework of eradicating hunger through sustainable development goals (SDG1 ‘No poverty’, SDG2 ‘Zero hunger’), market-oriented income diversification is considered one of the major pathways for upward mobility of rural populations. In the face of growing human challenges in the 21st century, income diversification would become a critical mechanism for survival. As rural households experience food insecurity due to declining farm incomes, the population of people living in poverty would increase exponentially. The population of Africans living in abject poverty has shot up by 35. 84% due to Covid-19 pandemic. According to Adjimoti et al. (Citation2017), the primary causes of rural poverty and food insecurity are a lack of income diversification opportunities, and exclusive reliance on a single source of income from the farm sector. They further argue that a single source of income from the farm sector is insufficient to make a living in many rural communities. Pursuing income diversification activities and earning multiple sources of income from the non-farm sector remains the only credible option for improving food security in the developing world (Jiménez-Moreno et al., Citation2023; Dzanku, 2019).

As we propose income diversification as a credible option out of the woods, let us examine the concept in the economic literature. What is meant by rural household diversification?. A rural household is either sufficiently diversified or absolutely diversified. A household is said to be sufficiently diversified if no single income source from the farm sector is greater than two-thirds of its total household income (Bitana et al., Citation2023; Alex, 2023). Rural households are absolutely diversified if they receive absolute levels of non-farm income from income generation activities (Bernzen et al., Citation2023; Chipenda, 2023). Whether they diversify partially or absolutely, income diversification is implied in both cases due to the pursuit of income generation activities other than crop and livestock production (Vimefall & Levin, Citation2023; Dzanku & Sarpong, 2011). In this context, rural households are said to be food insecure if they exhibit inadequate access to food and quality diets due to low incomes arising from low-income diversification (Salifu, Citation2019b).

Previous studies (Adem et al., Citation2018; Bitana et al., Citation2023; Getahun et al., Citation2023) have shown that sufficient income diversification improves food access due to higher incomes generated from diversification. However, a rural household’s capacity to expand net income from a portfolio of diversified activities is challenged by several factors. Some of the major challenges limiting rural income diversification include bad weather, prevalence of environmental risk and factors such as floods, bushfires and insect attacks, poor access to financial capital, poor rural infrastructure, high cost of transportation, and inadequate access to markets and health institutions due to poor power structure relationships between uneducated rural people, market and state (Salifu & Salifu, Citation2023). For emerging African markets, the greatest threat to rural income diversification is the infrastructural deficit problem related to the political economy of development (Sileshi et al., Citation2023; Edaku et al. Citation2023). As long as access to capital inputs relevant for optimum diversification are constrained by the lack of vital institutions and rural areas, the power dynamics will continue to play a major role in income diversification for food security (Zingwe et al., Citation2023; Hertel et al., Citation2023; Ibrahim, Citation2022).

The political economy of food secure literature asserts that rural households do not operate in a vacuum. Their capacities to diversify income are influenced by the political environment in which they operate. In African economies such as Ghana and Nigeria, the forces which shape market-oriented income diversification are not only influenced by markets, but they are driven by political and economic forces. The dominant political ideologies which determines access to institutions and capital assets required for income diversification are informed by political incumbency. There is evidence to indicate that households with sufficient access to capital inputs and support from the government enjoy a better share of the incentives for income diversification. Due to the lack of understanding of the political economy drivers of food security, the benefits of income diversification as an option for improving food security of marginalized groups have not been fully realized. The political struggle and ethnic-based politics associated with the formulation of income diversification policies have considerable influence on the food security of rural households

Political interventions such as the Ghana poverty reduction strategy (GPRS 1 & II in 2006), Ghana shared growth Agenda (2006–2009), and Planting for Food and Jobs initiative by the current governments, have all failed to substantially address the food insecurity problem of rural households in Ghana (Prah et al., Citation2023). Food insecurity has increased because Ghana’s food output is less than sufficient (MOFA, Citation2017). The country has consistently recorded high deficits in cereal production, resulting in price hikes for rice and maize. Following COVID-19, food inflation in Ghana has exceeded the global average of 50%. Increasing food prices due to international forces suggest that rural households whose earnings fall below the minimum cost of food baskets are less resilient and more food insecure.

Northern Ghana is sparsely populated with a significant population of Ghanaian rural households unable to afford the minimum cost of food. Northern Ghana is made up of five of the sixteen administrative divisions of Ghana. The Northern region has a significant majority of rural population living under abject poverty (Nchanji et al., Citation2023), The high rates of poverty and food insecurity have been attributed to structural inequities originating from the neglect of colonial and post-colonial policies (Yaro, 2013). The average income per capita in the region has consistently been below the national average (Salifu & Anaman, Citation2019). This means that the interventions might have been inadequate or inappropriate, arising from a poor understanding of the underlying problems and constraints in the creation of sustainable livelihoods.

Previous studies using sustainable livelihood frameworks have failed to articulate the political economy dimension of food security despite several political, economic, and institutional changes in northern Ghana. Few empirical studies focusing on how economic diversity affects food security via the political economy lens of food security have been conducted in Ghana or other developing countries. These studies have mainly focused on the impact of off-farm work on the adoption of technology, credit fungibility, and food security, among other things. Despite these studies, the political economy dynamics of food security has received very little attention. Few empirical studies such as Anang and Apedo (Citation2023), for example, have analysed income diversification using the double-hurdle model and propensity score matching techniques, which do not fully account for selection bias.

This study fills this gap by focusing on the political economy of food security in Ghana which has escaped research attention. The study also makes many unique contributions to the literature on the political economy of food security in many ways. First, we extend previous studies of income diversification by identifying the drivers of income diversification activities as well as the major factors limiting household income diversification within the political economy of food security in rural northern Ghana. Second, we use the Poisson regression approach which captures the political economy variables driving income diversification among marginalized groups to model the income diversification activities of rural households. Finally, we bring new insights to the debate on income diversification activities of rural households by using more recent data from a previously unreported area of Ghana to inform the formulation and implementation of rural policies for reducing food insecurity especially in emerging countries such as Ghana. The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In section two, we present a review of the relevant literature and an overview of political regimes and agricultural policies in Ghana while section three describes the methodology and empirical results of the study. Section 4 discusses the research findings while section six draws the conclusions and policy implications of the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Political regimes and food insecurity in Ghana

The Literature on food economics rarely evaluates the impact of political regimes on income diversification opportunities of rural households (Habib et al., Citation2023; Musyoka & Onjala, 2023). However, political regimes play a significant role in setting up institutions that govern the production, processing, and marketing of agricultural output. Therefore, the failure of political regimes to co-ordinate vital institutions for enhancing farmer wellbeing may often give rise to food insecurity. In a nutshell, political instability goes hand in hand with food insecurity because food is fundamentally politics. During periods of political instability, the capacity of poor households to generate income in the non-farm sector to purchase food is greatly undermined (Taruvinga et al., Citation2023; Yan, Mmbaga & Gras, 2023). If the state and market fail to invest adequately in the creation of alternative industries such as the building of market centres in rural areas, food insecurity will persist. In Ghana, income diversification, denoting the movement of rural labour from the farm to non-farm sector has been fed by two rivers; the post-independence development of the rural non-farm sector, and the promotion of state-owned enterprises in the 1960s and early 1970s (Ayambila, Citation2023).

These forces created new market opportunities and sparked growth in various sectors of the rural economy such as commercial farming, construction, eco-tourism, and business services, Thomsen et al., Citation2023). This spurred a structural transformation of the economy from subsistence-based agricultural economy into market-oriented agricultural sector. The market-oriented economy focused on the development of non-farm sector value chains. As the demand for income diversification commodities increased, it widened the gateway for increased levels of income generation activities (Amevenku & Asravor, Citation2023). Rural households were then better placed to take advantage of income diversification opportunities created by the emerging markets (Kassegn & Abdinasir, Citation2023). Consequently, the movement of labour resulted in the decline of the share of agricultural contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) (Ashiagbor et al., Citation2023). The reduced share of the agricultural sector in the national income has been partly due to the rapid growth of the services sector, whose growth has been fueled by the expansion of activities in the information, communication and technology (ICT) industry (Cismaș & Bălan, Citation2023). In Ghana today, the ownership of mobile phones has exceeded 100% of the population, and mobile money banking has now penetrated every village (Asante Boakye et al., Citation2023). Ghana is one of the biggest mobile money economies in Africa.

This strong foundation for increased income diversification in rural areas has been laid by the launch of the Economic Recovery Program (ERP) program (Owusu-Ansah et al., Citation2023). The ERP was triggered by the economic downturn which arose from the persistence of military coups and attempted military coups, from 1973 to 1982. The situation was worsened by the world oil market price shocks over the period, which increased crude prices tenfold within a decade. The severe El Nino-linked weather shocks of 1976/77 and 1982/83, which produced widespread severe droughts throughout the country, exacerbated food insecurity (Anaman, Citation2006). As far back as 1980, the then elected civilian administration, led by a Northerner, Dr. Hilla Limann, had started negotiations with international development agencies for economic recovery. This approach by the PNP government was considered treasonable by sections of the civilian and military elites and was a major factor in the overthrow of the PNP government in a military coup on 31 December 1981 by a military junta led by Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings which formed a governing council called the People’s National Defence Council (PNDC) (Kwazema, Citation2023).

The PNDC justified the overthrow of the PNP government, accusing the Limann-led government of being stooges to Western governments and imperialists. After initially propagating a vision of an extreme left-wing position, the PNDC faced with recurring economic shocks, abandoned its Marxist orientation, and negotiated an agreement for an ERP. Critics of the PNDC government have argued that the Limann’s PNP government would have negotiated a less stringent and more useful form of an economic recovery programme with Western development partners if the military coup had not occurred, and the democratic transition and governance of the Third Republic had continued unabated from its start on 24 September 1979 (Nyinevi & Fosu, Citation2023).

2.2. Political regimes and agricultural policies in Ghana

The political economy literature suggests that political struggle and ethnic-based politics within national agricultural organizations have considerable influence on agricultural policy formulation (Dzanku & Sarpong, Citation2011). Ghana’s agricultural sector has been shaped over the years by competing political ideologies against existing national agricultural policies (Yeleliere, Antwi-Agyei & Nyamekye, 2023). , presents a description of political regimes and their impact on rural food security. A major contribution of the (ERP)/SAP to the national economy was that it identified the agricultural sector as a key driver of sustainable economic growth (Agyei-Holmes et al., Citation2023). This identification fueled increased investment in the agricultural sector in the late 1980s. However, the agricultural investments mainly targeted the cocoa industry and neglected the food production sector, exacerbating food insecurity in the country (Snider et al., 2023). For example, cocoa marketing depots and sheds were transformed and rebuilt; however, most of the food market centres were left in a very poor and unsanitary state and continued to deteriorate such that in more recent times, most of these market centres have to be completely rebuilt. As a medium-term measure to address growing food insecurity, the Medium-Term Agricultural Development Program (MTAD) was introduced from 1991–2000 to enhance food self-sufficiency in Ghana (CitationDzanku & Sarpong, 2011). MTAD was modestly successful, increasing farm output by 2.4% on average between 1990 and 2015 (Cobbinah et al., Citation2023). However, the share of agricultural contribution to GDP declined alongside the share of total labour force employed in the farm sector. The movement of labour out of farming into non-farm activities contributed to higher average growth rates in productivity.

Table 1. Description of political regimes and effects on food security policy in Ghana from 1951 to 2024.

This movement of labour triggered a rapid decline in the distribution of farm land in the mid-2000s as the share of farm holdings with less than five hectares (five hectares) decreased from 92% in 1992 to 84% in 2012 (Amfo et al., Citation2023). The declining farm size is associated with the structural transformation process in sub-saharan Africa where rural income diversification is accelerating. This structural transformation indicates the importance of the role of the non-farm sector for the enhancement of food security and poverty reduction in Ghana. Comprehensive frameworks which underscored the relevance of non-farm income to food security were designed by the state. The strategic focus of these frameworks was to achieve accelerated shared growth and poverty reduction among rural households. Subsequent agricultural policies of the government were linked to these frameworks (MOFA, Citation2017). Rural households participating in both on-farm and off-farm diversification were seen as a key element of the Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP II).

2.3. The status of income diversification and food security in Yendi and Nanumba North municipals

The poverty trend analysis of the northern region, as reported by the previous works, clearly points to the prevalence of high poverty in rural northern Ghana. Poverty rates exceed 80% in some rural communities of the Yendi and Nanumba North districts. It is estimated that two-thirds of rural children under 5 years of age are malnourished, and about half of the population of rural women in the region suffers from nutrition-related problems (Bigool et al., Citation2023). The persistent poverty and food and nutritional insecurity in the two districts remains a daunting challenge for policymakers, and several measures to eradicate food insecurity in rural northern Ghana have not been wholly successful (Adjei & Serbeh, 2020). Growing food and nutritional insecurity have disastrous effects on the national human capital development (Ameyaw et al., Citation2023). Human capital development affects the productivity, economic development, and sustainability of a nation. Farming remains the dominant economic activity of households in rural Northern Ghana. While southern Ghana is naturally endowed with a bimodal rainfall pattern, the Northern region has a uni-modal rainfall pattern (Bessah et al., Citation2022). The very limited irrigation infrastructure in the region makes all-year-round farming an impossible task (Balana & Akudugu, Citation2023). These conditions combined to perpetuate poverty and deepen food and nutritional insecurity in the study area. The government, together with development agencies in the region, has explored many approaches for reducing food insecurity (Ma et al., Citation2022). Each intervention represented a new strategy, with each intervention giving way to the others. Some of the earlier interventions introduced in the 1960s were broad strategies, including an integrated social development framework and ERP/SAP structural adjustment programs. These frameworks have been criticized for top-down interventions. In the 2000s, a mix of bottom-up participatory approaches to reduce poverty, such as the rural accelerated development programme in Savanna, failed to significantly drive down poverty in rural northern Ghana.

The challenges of previous interventions have created disillusionment with prevailing approaches to poverty reduction, which has generally been characterized by market-oriented agricultural specialization with the development of value chains (Sekyi et al., Citation2023). This approach emphasizes increased crop production and diversification. The Green Revolution has promoted the conventional narrative of poverty reduction and food security (Richards, Citation2023). However, the environmental capital of the northern region does not support this approach because of the growing threat of climate change (Batung et al., Citation2023). Farm-level specialization under adverse environmental fluctuations could reduce crop yields, such as maize, and increase vulnerability and food poverty (Tanko et al., Citation2023). Moreover, farm size in the districts average (2 ha); making it difficult to derive the economic value associated with the conventional farming approach which prioritizes commercialization (Boateng et al., Citation2023). An alternative approach to the upward mobility of household heads from poverty is to promote market-based income diversification for rural households through expanded access to capital inputs that can help them earn wage income from non-farm economic enterprises (Duho et al., Citation2023). The farm-level specialization approach entails a high opportunity cost for rural households who could earn a continuous flow of income from undertaking several income generation activities at different periods of the year to buffer price-related shocks (Anang & Apedo, Citation2023). Although this approach promises sustained poverty reduction and food security enhancement, evidence from the survey suggests that due to weather shocks, farm yields are too low to support a minimum livelihood (Kurantin & Osei-Hwedie, Citation2022). Published works have examined the drivers of agricultural diversification in rural Northern Ghana. Previous studies have evaluated the rural employment in this region. Notwithstanding the specific contribution of previous research, there is a dearth of studies regarding the political economy constructs underlying farmers’ capabilities, constraints, and opportunities for income diversification.

2.4. Previous studies of income diversification and food security

The literature notes that income diversification is necessary to enhance farmer livelihood because of the susceptible susceptibility of the agricultural sector to several natural disasters, including but not limited to floods, droughts, pest and disease attacks, insect invasion, bushfires and theft (Ahmad & Afzal, 2020). It is crucial to emphasise that apart from farmers, development researchers and practitioners have strongly recommended income diversification trajectories as alternative pathways to increasing farmer resilience to food poverty (Anang & Apedo, Citation2023). Researchers, for example, Eshetu and Mekonnen (Citation2016), Li et al. (Citation2021) found that income diversification provides alternative sources of income for reducing rural food insecurity.

Kuwornu et al. (Citation2018) assert that rural people’s overall income, food access, and daily calorie intake are all improved by income diversification. In other words, households experience less food poverty when they have alternative income sources to fall on during periods of farming adversity. In Ghana, Issahaku & Abdul-Rahaman (2019) develop a similar set of arguments for improving food security through increased diversification of rural people’s microenterprises. Additionally, it has been shown that income diversification promotes technology adoption essential for increasing farm output. For instance, income diversification supports the adoption of innovative farm management practices in northern Ghana (Issahaku & Abdul-Rahaman, 2019). Anang et al. (Citation2020), and Tenaye (Citation2020) all find that income diversification leads to increased productivity and technical efficiency among smallholder farmers.

Other researchers have reached contradictory conclusions on the effect of income diversification on food security. Lien et al. (Citation2010) suggest that income diversification reduced farm output and productivity among smallholders. It is posited that income diversification reduced time spent on farming and the resultant labour loss contributed to low farm output. However, Ahmadzai (Citation2020) concluded that participation in non-farm work decreased co-variate risk associated with on-farm income generation activities. McNamara and Weiss (Citation2005) and Mishra et al. (Citation2004), argued that income diversification stabilized income and helped rural holders to maintain standards of living during the off-farm seasons. One way to interpret farmers’ desire to diversify their sources of income by working for non-agricultural wages is as a risk-management tactic meant to stabilize their standard of living. Studies by Salifu & Anaman (2019a) and Adem et al. (Citation2018) found that rural income diversification depended on household size. As a survival strategy, high household sizes pushed other members of the household to diversify income sources in order to decrease the dependence on a single flow of income. It is claimed that rural people’s propensity to diversify income sources depended on reliable access to utility services such as power and water. Xing and Gounder (Citation2021), assert that rural people with access to formal education stood a better chance of diversifying income sources because of their human capital edge over poorly educated household members. Researchers evaluating non-farm employment among rural households in Ghana, cite gender as a major determinant of income diversification. They observed that women were more likely to engage in diversification than men.

Notwithstanding the specific contribution of previous research, there is a dearth of studies regarding the political economy constructs underlying farmers’ capabilities, constraints, and opportunities for income diversification. Few empirical researches have been conducted in Ghana or other developing countries to examine the impact of structural inequalities originating from differential access to capital inputs of production on income diversification. Political economy analysis examines the impact of these social differences on the capacity to diversify income sources. Given the fact that rural households operate a nation state where power relations between people and governments determine access to opportunities, political economy analysis becomes ever crucial in the overall attempt to fulfil SDG goals 1 and 2 (zero hunger) among marginalized groups. The vulnerability context of householders in Northern Ghana, their diminishing lack of access to capital inputs, and increased exposure to climate shock factors cannot be trivialized in the discussion to fulfil the SDG mandates of ‘On poverty’ and ‘Zero hunger’ for all.

Research on income diversification and food poverty in Ghana has mostly concentrated how income diversification relates to the adoption of technology, credit, fungibility, health care, and food security, among other things. In a country of different religions and tribes, the impact of political economy factors on the diversification potential of rural households cannot be ignored. However, this has received little attention inspite of its clear linkage to institutional assets and infrastructure for income diversification. If there is an area that requires renewed attention in income diversification and food security analysis of rural people, then it ought to be a political economy analysis of food security among disadvantaged populations. Although a substantial amount of research attention has been devoted to improving our understanding of the hardcore factors of income diversification and food security, there is still a dearth of knowledge regarding the adaptive political economy aspects of food security which need to be filled. This study is an attempt to fill this gap.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Conceptual framework

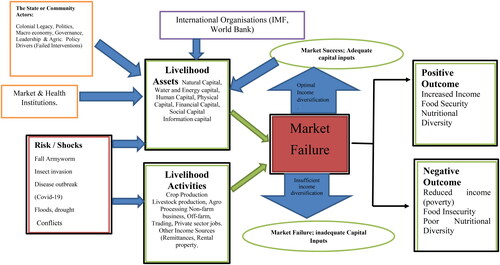

This study is one of a political economy analysis of income diversification. Like all political economic analyses, the study utilizes a variety of theories (lenses) in combination to analyse and understand an underlying system through human inquiry (Salifu & Anaman, Citation2019a). Salifu (2019b), indicated that the income diversification activities of rural households are determined by three factors: the first is the level of endowment of capital stock of the rural household, the second is the portfolio of income generation activities undertaken, and the third is the nature of the political economy of the environment in which diversification into non-farm sector occurs.

The study is driven by a core theory (the captain pilot of the flight), while the other two theories (portfolio theory and risk management, and structuralism theory) are co-pilots. This core theory is the sustainable livelihood (SL) framework. As indicated earlier, the SL framework suggests that the sustainable livelihood of a household is underpinned by the acquisition of adequate levels of capital inputs. The household combines labour and management inputs with capital inputs to produce goods and services desired by that household (subsistence production and consumption), and demanded by markets within the nation state (Ghana) and beyond (overseas countries). It is primarily the inadequacy of the capital inputs that could limit the sustainability of the livelihood of the rural household as labour inputs are assumed to be in plentiful supply to meet sustainable levels of production and consumption (Adeoye et al., Citation2019).

As noted by Duho et al. (Citation2023), risk management aspects of income diversification are critical in the decision by household managers on the types of income generation activities that are undertaken which make them comfortable bearing in mind the risks and variability inherent in the income-generation activities. The SL and risk management frameworks sum up the position of the household as an individual-producing entity in isolation as a mutually exclusive silo. However, the individual lives within a nation state, and is governed by the rules and laws of the nation state. Structuralism theories provide the third framework in the development of the conceptual framework of this study. These theories do not replace the SL framework but enhance the latter framework, similar to the role played by those played by the portfolio and risk management theory outlined above. Some of the goods and services produced by households are sold at market centres. Householders also source inputs from input and markets to use for production. The quality of physical infrastructure in a locality shapes the nature of production and the goods and services that are produced. The endowment of physical infrastructure in a locality depends on the power relationships between the locality and the power structure of the Nation-State. Often, localities with less endowed physical infrastructure, such as clinics, hospitals, roads, and schools are populated by citizens who are marginalized, with less political clout, whose citizens are underrepresented in national bodies which develop programmes for the advancement of the nation state.

The enhanced SL framework for income diversification analysis provides three key components that are relevant to understanding the issue of rural household diversification for food security. Firstly, the framework considers the risks and shocks, adverse trends, and seasonality that lead to income instability and food insecurity. The assessment of risks and vulnerability of rural households makes it more contextual in the analysis of household diversification. Secondly, the concept of sustainability is a core principle in the SL framework as it highlights the income generation strategies that rural households in the study area can undertake to enhance their capital inputs or capabilities for the present and future. Thirdly, the framework identifies coping strategies representing activities that are or can be undertaken in response to risks or shocks that lead to chronic food insecurity and malnutrition in the study area.

illustrates the conceptual framework based on the SL framework. Capital inputs are managed by the rural households to produce a set of income generation activities which include on- farm activities and non-farm activities. These income activities are influenced by various risks and shocks. Successful adaptive coping allows for higher earnings from the quantum of income generation activities pursued and increased food and nutritional security, allowing rural households in the study area to participate more fully in consumption markets. Poor adaptive responses lead to pronounced food insecurity and malnutrition.

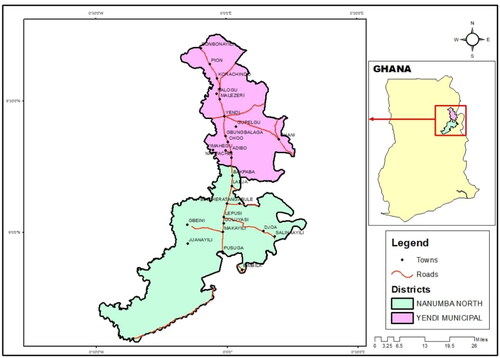

3.2. Study area description

The study area is located in Northern region of Ghana. The country is geographically and administratively made up of sixteen regions with a population of roughly 30 million. Ghana’s capital, Accra, is located in Southern Ghana. The entire mass of land area of Ghana is around 238,535 km2. Northern Ghana is in the Guinea and Sudan savannah ecological zones. Rainfall-dependent agricultural production is only possible once a year in the Guinea and Sudan Savannah natural zones due to unimodal precipitation patterns. Our study uses Yendi and Nanumba North (Bimbilla) municipals of the northern region as a case study. represents the map of Yendi and Nanumba North.

3.3. The cross-sectional survey method

This study adopted a quantitative approach that provided ‘a quantitative or numeric description of trends, attitudes, or opinions of a population by studying a sample of that population’ (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). Focus group discussion involving confidential interviews with local experts and key informants was adopted as the qualitative design for the study. The study adopted multistage cluster techniques to sample the key respondents. It entailed the listing of primary units in the two districts. This was to give every household an equal chance of selection. The population was clustered based on the most recent housing and population census data. The random selection method for drawing the optimal sample size for the study was computed based on the prevailing size of the adult population in the district. An optimal sample size of 500 rural households was required for this study. A ‘simplified formula to calculate sample sizes’ was used to establish the minimal sample size considered statistically acceptable (Yamane, 1967:886). It is assumed that P = 0.05 at a 95% confidence level. It states that;

(1)

(1)

where α = confidence interval; n = sample size; N = sample frame or total number of rural households in the study area; and 1 = constant. As a result, the sample size was calculated using a sampling frame of 58,236 rural household populations. By substitution into the mathematical formula with a 0.05 percent error margin and a 95% confidence interval, as shown, sample sizes of 500 respondents were yielded. i.e.

3.4. Data sources and collection methods

Data on various variables was solicited from 500 household heads in the Yendi and Nanumba North Municipalities and extracted for the study. Following a brief pretesting survey in June 2019, data collection was done from August to November 2019. In addition to the primary data, the survey used an interview guide to identify new variables that affected income diversification. Secondary data on income diversification was secured from local government institutions such as the Rural Enterprise Programme in the study area being implemented under the auspices of the Ministry of Trade and Industry. The variables extracted from the data and used for the study are presented in .

Table 2. Variables and their definitions.

Data was solicited from 500 household heads in the Yendi and Nanumba North Districts. Following a brief pretesting survey in June 2019, data collection began from August to November 2019. In addition to the primary data, the survey used an interview guide to identify new variables that affected income diversification. Secondary data on income diversification was secured from local government institutions as such the Rural Enterprise Foundation in the study area.

3.5. Empirical analysis of data

Several factors influencing rural income diversification may be estimated using a variety of econometric models. The models are used to determine factors influencing household decisions to undertake a particular type of income generation activity. Econometric models such as the Multinomial logit (MNL) or Multivariate Probit (MPP) regression techniques are used to determine the effect of explanatory variables on the dependent variable (Greene, 2000). They are ideal when the household head is presented with two income generation choices. The only drawback to this technique is that it is unable to explain the reasons that influence a household’s decision to undertake multiple income generation activities. Hence, the study used the Simpson diversification index or the Herfindahl Concentration Matrix (HHCI) (see, for example, Minot, Citation2006) to account for all income-generating activities undertaken by households. It is estimated as 1-HCI. This diversification measure was originally developed by Simpson (1949). It indicates the general spread of various income-based activities engaged in by houlseholders. A high SDI value connotes a maximum degree of income diversification by the household as compared with a lower SDI score.

The SID is mathematically illustrated in EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) as follows:

(2)

(2)

Where SID = Simpsons Index of Diversity which is the proxy for the degree of income diversification, n = number of income sources, Pi = income source, as a proportion of gross total income generated by households (THI), the value of SID ranges from Zero (0) to One (1). For households with only one source of income, Pi =1, implies that SID = 0. NEA and SID are the diversification measures used in the study. This study is underpinned by the sustainable livelihood and structuralism political economy framework.

The SID model is specified in this study as follows:

(3)

(3)

Where HHR = Household Head Remittances Income, HHRI = Household Head Rental Income, HHWI = Household Head Wage Income, HHNFBI = Household Head Non-Farm Business Income, HHAOSI = Household Head All Other Sources of Income, HICP = Household Income from Crop Production, HILP = Household Income from Livestock Production, SWI = Spousal Wage Income, SNFBI = Spousal Non-farm Business Incomes, SR = Spousal Remittances and THI = Total Household Income.

3.5.1. Poisson regression

This method of evaluating income diversification is based on the count index (NEA). Given a set of parameters β and an input vector x, the mean of the predicted Poisson distribution is mathematically expressed as follows:

(4)

(4)

The Poisson distribution’s probability is also given by:

(5)

(5)

The empirical estimation of Poisson regression model for the determinants of long-term income diversification based on EquationEquations (3(3)

(3) and Equation4)

(4)

(4) is given in EquationEquation (5)

(5)

(5) as follows:

(6)

(6)

Where is the income diversification measure based on the count index (NEA), α0 is the intercept;

are the parameters to be estimated,

are the exogenous regressors consisting of household characteristics (household size, age of household head, gender/sex of household head, formal education of household head, religious affiliation of household head, years of technical education of household head, ethnic group of household head, marital status of household head); risks or shocks (fall army worm invasion, floods, and insect invasion); livelihood assets (rental property, rooms, mobile phone, radio); non-farm income sources of household head (remittance, spouses share of income), community infrastructure variables (distance to inputs markets, distance to produce markets, time to clinic), other (extension visits) and Ɛ is the error term.

3.5.2. Tobit regression

It was estimated based on the share of gross income received by household heads (Tobin, Citation1958). It is mathematically expressed as follows;

(7)

(7)

Where Y* is Tobit latent value for the relevant income diversification variable. Xi is the vector of independent variables, although not all the independent variables described above are included in every income diversification model. βis are the coefficients of the vector parameters to be estimated. is the error term. The empirical models were derived by means of maximum likelihood methods available on the Time Series Processor software (Hall et al., Citation1996).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Socioeconomic characteristics of the sampled rural households

provides information about socio-economic characteristics of the 500 randomly selected households. The results showed that slightly over two-thirds (67.6%) of the household heads were men and 32.4% were female, suggesting a male-dominated society. About seven in ten of the households (69.6%) were between 30 and 49 years of age. The vast majority (86.2%) of the household heads were currently married at the time of the survey. Three percent of the married household heads had multiple spouses with the remaining 83.2% having one spouse each. Furthermore, about 2.2% of the household heads were engaged at the time of the study and 0.4% (two) of these heads were in flexible consensual relationships without formal marriage agreements.

Table 3. Characteristics of the sampled respondents.

The vast majority of the household heads (85.2%) never attended school. Nine percent of the household heads completed six years of primary school with a further 11% of these heads having at least some year of primary school education with a further 2.6% of these heads completing the equivalent of junior high school education. Six of the household heads (1.2%) attended technical or vocational institutes. The dominant religion in the survey areas was Islam with slightly over three-quarters of the household heads indicating it as their religion. The second dominant religious group was the adherents of Traditional African religions, with 21.2% practising these religions, either as sole religion (9.6%) or through mixed religious preferences (11.6%). Only 3.2% (16 people) of the household heads were practising Christians. Whereas Christianity is the dominant religion in Ghana, the Yendi and Nanumba North districts could be considered a haven of Islam and Traditional African religions.

About one-quarter of the household heads (25.2% or 126 people) belonged to the Nanumba social/ethnic group. The Nanumba social/ethnic group or subethnic group is part of the broad ethnic group called the Mole-Dagbani. The dominant group in the Mole-Dagbani broad ethnic group is the Dagombas. Dagombas were the third largest group accounting for 17.8% of the household heads. The second largest group was the Kokomba. Kokombas are part of the Gruma broad ethnic group. Ghana has nine broad ethnic groups as follows: (1) Akan, (2) Dangme/Ga, (3) Ewe, (4) Guan, (5) Gurma, (6) Mole-Dagbani, (7) Grusi, (8) Mande, and (9) All Other Groups. Gonjas were the fourth largest subethnic group among the 500 respondents, representing about one in seven of the respondents (14.2%).

As shown in , the predominant profession of the household heads was agriculture with almost nine of ten heads (89.6%) involved in this occupation. Household heads working for state institutions were 6.8% of the sampled respondents. Twelve of the 500 respondents (2.4% of the sample) were employed by private agencies and companies. Six of the household heads (1.2%) were sellers of food and food products.

4.1.1. Summary of characteristics sampled respondents

provides a summary of the socio-economic characteristics of the 500 sampled households using average and range figures. The average age of the household heads was 44.76 years with the range of 19–90 years. The number of years of formal schooling acquisition was only one year with a range of zero to 14 years. The vast majority of the household heads (never attended school. Few household heads completed six years of primary school with even fewer household heads attending a technical or vocational institute. The average household size was 10.71 with the range of 5 to 19. This average household size was much larger than the national average household size of 4.2 as revealed by the 2010 National Population and Housing Census (Anaman & Adjei, Citation2021) Ghana Statistical Service (2013). The ownership of both mobile phones and radio sets was very high.

Table 4. Characteristics of sampled respondents.

4.2. Measures of income diversity and income sources of sampled respondents

shows that respondents (household heads and spouses) pursued between one and ten economic activities (NEAs), with an average of 7.07 and a standard deviation of 2.21. These economic activities were as follows: (1) remittance income receivers, (2) rental income receivers, (3) wage-based income receivers, (4) non-farm business income receivers, (5) all other sources of non-agricultural income receivers, (6) crop income receivers, (7) Livestock income receivers. (8) wage-based income receivers (Spouses), (9) non-farm enterprise income receivers (spouses), for example, from sewing and food preparation businesses, and (10) remittance income receivers (spouse(s). Crop and livestock incomes were jointly owned incomes by the household head and spouses. The Simpson index, which measures total diversity, averaged 0.7958 (79.58%) with a 7.4% standard deviation. The Simpson index range of 0.41 to 0.89 (41% to 89%) showed a high degree of income diversification among rural families.

Table 5. Measures of income diversity and income sources of household heads.

From a political economy analytical perspective, income diversification of rural households in the study area can be envisioned as a game played by the household against poverty and food insecurity. The ten broad sources of income could be classified like a football team, as a 4-3-3 formation. The four sources of income are those solely generated by the household head (defenders), the next three sources of income are crop and livestock production, and all other non-agricultural income sources, which are jointly produced by the household head and the spouse (s), (mid-fielders), and the last three sources of income are those solely earned by the spouse(s) (the strikers).

4.3. Results of share of distribution of income sources

provides the computed shares of each source of income as a percentage of the total family income. The total of all 10 income sources was used to calculate the family income. also lists the percentages of all respondents who received income from each of the 10 sources.

Table 6. Share of income sources as a distribution of farm family income.

4.4. Results of shares of agricultural income sources as a distribution of farm family income

Crop production accounted on average GHS 947.10 per household during the 2018/2019 production; this constituted only 4.48% of the total household income (). The dominant crop production activity was related to maize; maize production accounted for about two-thirds of the total income derived from crops. Of the ten sources of broad income-generating activities, crop and livestock production are generally considered jointly managed activities, with the household, head and spouse(s) playing some considerable part of the activities involved in the production of crops and livestock.

Table 7. The sources and size of agricultural-based incomes for the sampled rural households in the Yendi and Nanumba North Districts.

4.5. Results of shares of the total household incomes generated from ten economic activities (NEA)

presents the shares of income generated from 10 economic activities pursued by rural households in the study area. Of the ten sources of broad income-generating activities, crop and livestock production are generally considered jointly managed activities, with the household, head and spouse(s) playing some considerable part of the activities involved in the production of crops and livestock. The four sources of broad income-generating activities which were managed or controlled by the household head were (1) remittances going to the household head, (2) rental income going to the household head, (3) wage-based income earned by the household head, and (4) non-farm business income earned by the household head or controlled by the household head. The average total of these four sources of income indicated for the 2018/2019 production year was GHS 8,370.04 and accounted for about 39.56% of the total household income ().

Table 8. Shares of the total household income attributable to ten economic activities (NEA).

The three sources of total household income directly controlled and managed by spouse(s) derived from the study were (1) wage-based income earned by the spouse(s), (2) non-farm business income earned by the spouse (s), and (3) remittances received by the spouse(s). These three sources totalled on average GHS 6,177.48 and constituted about 29.20% of the average total household income. This proportion was this was slightly lower than the proportion of the average total household income attributed to jointly managed income (31.24%; ). Jointly-managed income came from crop production, livestock production, and all other incomes generated by the household which were considered jointly managed businesses. The total jointly managed income was GHS 8,370.04 during the 2018/2019 production year.

4.6. Determinants of long-term income diversification (NEA/count index)

The determinants of NEA undertaken by the sampled households are presented in . Given that NEA varied from one to ten activities, this variable was considered a count variable requiring estimation by the Poisson regression method to analyse its determinants. The empirical analysis showed that exactly half (11) of the 22 independent variables had statistically significant parameters. The 11 independent variables significantly influencing NEA were (1) AGEHH, (2) AGEHHSQ, (3) EVERMARRIED, (4) FORMALEDUCATION, (5) REMITTANCEHH, (6) RENTALPROPERTY, (7) EXTENSIONVISITS, (8) TIMETOCLINIC, (9) FLOODS, (10) DISTANCETOINPUTSMARKET and (11) MOBILEPHONE.

Table 9. The Poisson regression model of the count index (number of economic activities NEA).

The effect of age on NEA was curvilinear (U-shaped curve) in nature with the quantum of economic activity increasing after a certain age point. This finding contradicts Anang and Apedo (Citation2023) who found that the age of the household head had no influence on the number of income generation activities undertaken by the household head. The nature of the influence of age points to a life-cycle pattern behaviour of rural householders with relatively younger household heads engaging in less income-generating activities while relatively older heads acquire more businesses and enterprises to earn income over time. Of the remaining nine statistically significant variables, the amount of remittances to the household head, the distance to inputs, markets, ownership of mobile phones, floods, and extension visits were positive influencers of income diversification endeavours of household heads. Remittances were an essential driver of income diversification practices of household heads related to the quantum of economic activities undertaken given the start-up capital that it afforded rural householders to start new enterprises. This result concurs with that of Ankrah Twumasi et al. (2023) and Zingwe et al. (Citation2023) who found that remittances received by household head were critical in enhancing household income generation activities. According to Salifu and Salifu (Citation2023), one of the most important challenges of rural income diversification is the lack of start-up capital. Remittances are vital in generating start-up capital needed for setting up microenterprises such as retailing of farm inputs, among others. In addition, increased remittances also facilitate financial inclusion for rural households through savings mobilization. Moreover, remittances can contribute to the inclusive growth of rural households by reducing income inequalities due to the additional household income generated from setting up rural microenterprises, mitigating the risk of agricultural production by strengthening the resilience of rural households against risks such as pest infestation, floods, drought and other extreme weather events emanating from climate change and thus help to reduce food insecurity. Efficient payment services for remittances can also lower the transaction costs and increase the speed and security of payments, resulting in poverty alleviation.

The result on mobile phones is anticipated. Mobile phones are currently an important information communication tool required to gather data on market and production activities and hence can be a tool to encourage the setting up of new income-generating activities. The ownership and usage of a mobile phones also enables information sharing, facilitates access to information about improved farming practices, and enhances financial inclusion by increasing access to a range of financial services and products. Through these roles, mobile phone ownership and usage increases productivity, facilitates income generating opportunities of households as well as enhance their consumption expenditure, and thus spur economic activities in rural areas. The positive relationship between the distance to input markets and NEA could be due to the longer distances required to obtain certain inputs being disincentive to householders for purchase of these inputs from long-distance market centres. Hence, householders would be forced or incentivized to produce and/or sell these inputs in their localities, encouraging the setting up of selling and buying activities related to the acquisition of inputs necessary for the production of various activities. The occurrence of floods in the area gives mixed blessings. While floods could hamper some production activities temporarily, it also allows for the retaining of vital amounts of water in storage, which facilitates the production of various crops in the dry season. Another possible explanation for the significant relationship between the occurrence of floods and the NEA is the contribution of insurance payouts to the incomes of rural households. Most rural households are economically active in the informal or in the agriculture sector, both of which are highly vulnerable to climate-related stocks such as floods. To cushion themselves on the adverse impact of these weather-related shocks or events, these households tend to purchase basic insurance services or products such as crop insurance. Therefore, the occurrence of these events triggers insurance payouts or claims which contribute to increasing the incomes of these households.

The positive relationship between extension visits and income diversification indicates the importance of information provided by extension officers to rural people on various income-generating activities, beyond agricultural enterprises and on-farm activities. This could also be explained by the increased non-farm wages resulting from the commercialization of the knowledge gained by rural household heads who are trained by the extension officers to serve as trainer of trainers for other farmers. Moreover, household heads who are certified trainers also deliver customized training as well as connecting other farmers with input dealers, financial institutions, and buyers of produce for fees or commission. The resulting income or wages from providing such services ensures increased income for these household heads.

This result synchronizes with the findings of Adem and Tesafa (Citation2020), Anang et al., (2020), and Atuoye et al. (Citation2019) who found that extension services increased income diversification of household heads at 1% significant level. Extension officers often play a much bigger role in information dissemination, beyond the narrow scope and mandate of government-appointed agricultural extension officers, to include the provision of information on other activities pursued by householders in non-agricultural areas.

The remaining four statistically significant variables negatively affected NEA. Ever-married status was a dummy variable; the statistical significance of its parameters implied a higher proportion of older people who were divorced or widowed; the negative relationship reflected the reduced levels of NEA as such people approached retirement age. Having a rental property assured the household head some form of stable income, reduces the need to undertake many income-generating activities. The amount of time spent to reach a clinic or hospital would clearly affect the quantum of economic activities pursued by households who would be affected by various ailments and illnesses during the production year, which could force some of them to suspend or reduce the number of these activities. This is consistent with Kassegn and Abdinasir (Citation2023) and Dedehouanou and McPeak (Citation2020) who found that access to markets and health institutions increased the income diversification potential of rural households.

4.7. Determinants of short-term income diversification Simpson index (overall diversification)

presents the results of the drivers of income diversification estimated although the Simpson index analysis. Here, the standard multiple regression procedure was used for the analysis instead of the Tobit regression procedure. This was because none of the 500 households had a zero diversification index. As indicated in , the Simpson index averaged 79.6% with a range of 41% to 89%. The model reported in , was correctly specified based on the Ramsey Reset test, with the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis of adequately specified model being 0.446, much higher than the maximum statistical significance level used in this study of 0.10. Furthermore, there was no significant heteroscedasticity as measured by the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test of heteroscedasticity, with the computed p value of the LM test being 0.195 above the 0.10 critical level. The power of the model was very high with the R2 and adjusted R2 being 0.922 and 0.918, respectively. The diagnostic tests clearly confirmed a very good model useful for interpretative analysis and conclusions.

Table 10. Multiple regression analysis of the Simpson income diversification index (overall diversification).

The results from confirm that 12 out of the 22 independent variables significantly influenced the overall income diversification measure indicated by the Simpson Index. It is important to indicate that the Simpson Index measures the diversification of activities as revealed by the ten broad groups of income-generating activities during the 2018/2019 production year. Essentially, the Simpson Index reflects diversification in the short-term. The six independent variables that positively influenced the Simpson Index were (1) CURRENTLYMARRIED, (2) TECHNICALEDUCATION, (3) REMITTANCEHH, (4) FLOODS, (5) RADIO, and (6) NANUMBA. The six independent variables that negatively influenced the Simpson Index were (1) SPOUSESHAREHHINCOME, (2) FORMALEDUCATION, (3) FALLARMYWORM, (4) INSECTINVASION, (5) DISTANCETOINPUTSMARKET, and (6) DISTANCETOPRODUCEMARKET.

Starting with a discussion of positive influencers, currently married householders diversified more due to a combination of enhanced specialization of tasks and shared managerial experience in handling jointly managed enterprises compared to those not currently married. The very strong positive influence of post-secondary technical education on overall income diversification would come from the specialist skills obtained. Based on the results provided in , this variable (EDTECH) was the most important variable affecting the Simpson Index with a standardised parameter value of 1.171, which was over three times the value of its nearest rival variable, FORMALEDUCATION (0.330). This is explained by the fact that the improvement in technical knowledge and skills of rural household heads provides an enabling condition for increased farm productivity and expansion of non-farm economic activities such as tailoring, masonry, carpentry etc. that require some technical skills. Higher technical education also improves total factor productivity by reducing the proportion of labour capital used for agricultural production over time, which enables household heads to pursue and or engage in other non-farm economic activities. Moreover this result agrees with Anang et al., 2020, Adem and Tesafa (Citation2020), who asserted that skill capital acquired by the household head was a major driving factor of income diversification. However, Beyene (Citation2008) observed that skills acquired by technical education had no influence on income diversification in Ethiopia.

Note that results for the two diversification measures, NEA and SDI showed that remittances received by the household head were a positive driving force for income diversification. Moreover, floods correlated positively with income diversification through the availability of stored water for various activities during the dry season. Radio as a positive influencer of income diversification was due to its use as an important information tool to gather data and information on production and marketing activities. This result is consistent with previous studies on the determinants of income diversification among rural farmers (Danso-Abbeam et al., Citation2018, Edaku et al., Citation2023, Dzanku & Sarpong, Citation2011; Kim, & Fellizar Jr, 2017). There was some evidence that Nanumba-headed households had a higher level of income diversification than non-Nanumba headed households; although this result did not show up in the previous discussion of NEA. The Kokomba ethnicity variable and the religious variable (ISLAM) did not have any significant influence on the Simpson Index or NEA measures of income diversification.

With regard to the negative influence on income diversification, the most compelling results come from the negative effects of the presence of fall army worms and insect invasion on disastrous impacts on economic activities, notably crop and livestock production. These factors tend to force farm households to seek additional income generating activities within and/or outside farming activities. To survive, reduce their vulnerability, or avoid plunging deeper into abject poverty, poorer rural farm households engage in low-return nonfarm activities or survival-led types of income diversification. The inadequacy of infrastructural facilities, as measured by the distance from the residence of the household to either input markets or produce markets, negatively influences the income diversification propensity of household heads. Poor infrastructure such as distance to both input and produce markets inhibit access to market opportunities for rural households as well as increase transaction costs which are disincentives to engaging in certain economic activities. Similar to the arguments presented in the earlier section dealing with NEA, formal education conferred a higher chance of householders for positions in government service and private sector and could limit economic activities pursued by the household head due to time scarcity. The increasing share of the total household income attributed to activities solely managed by the spouse(s) reduced overall income diversification as measured by the Simpson Index, possibly due to the greater reliance on such spousal-derived incomes.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendations

The study investigated the political economy of rural household income diversification activities in rural Northern Ghana. The study used the Count index (NEA), Simpson’s diversification index, tobit regression, and multiple linear regression to analyse agricultural household income diversification in rural Ghana via the lens of the political economy of food security in Africa. The findings showed that income diversification improved food security. Food access and nutritional diversity increased for households which generated higher incomes from increased income diversification. A minimum number of seven (7) income generation activities by household, head, and spouse (s) improved food security. Households which diversified below this number, due to poor endowment of capital inputs consistently reported being food insecure and undernourished. Income diversification was found to be influenced by many drivers. The positive drivers of income diversification were age of household head, remittance, income received by households, marital status, and number of extension visits, years of post-secondary technical education, rental property, and mobile phones. The negative influencers of income diversification were; occurrence of floods, insect attacks, distance to market centres for inputs and produce, and distance to clinics/hospitals. The exposure to environmental hazards and distance from institutions were the main political economy drivers of diversification. Ethnicity and religious affiliation of households had no significant impact on income diversification. The relationship between the count index and age of respondents resembled a U-shaped curve, with income diversification increasing diversification after a certain age was reached. For short-term diversification measures, the Simpson diversity index (SDI) averaged 79.6% with a range of 41% to 89%. Increasing SDI implied a higher degree of diversification compared to lower SDI. SDI of 41% to 89% implied moderate to high levels of income diversification. Amount of remittances received increased financial capital of households enabling them to set up retail enterprises such as sale of fertilizers, seeds, insecticides, and farm inputs in rural areas and reduced income inequalities due to the additional income generated from the additional economic activities. The longer distance from market centres and poor road infrastructure helped retailers of inputs and produce to realize decent profits from diversification in rural communities. Access to and usage of mobile phones provides business development and information that encourages the setting up of businesses as well as increased rural household access to inclusive financial services and products such as savings, credit, insurance, and payments which are increasingly being delivered through mobile phones. Post-secondary technical education was the most important variable driving short-term income diversification in northern Ghana.

In the light of the findings, the authors suggest that rural households can be supported to undertake income diversification activities through improved access to credit and other financial services. Given the occurrence of natural disasters, insect invasions, and severe weather shocks, income diversification will help reduce the risk associated with farming. Efforts to improve financial inclusion and facilitate access to inclusive financial services such as crop insurance by use of rural households should be intensified in order to mitigate such risks. Incomes realized from diversification would help small-scale farmers to minimize their vulnerability to climate-related events, enable them to survive thrive, and adapt to the effects of climate change such as famine and other associated disruptions in food supply chains. In spite of these benefits to rural households, Ghana’s agricultural policy frameworks have not given adequate attention to rural diversification as a means to improve food security in Ghana.

The results and conclusions from this study provide several useful policy recommendations that could be implemented to improve income diversification and food security in the Yendi and Nanumba North Municipalities of northern Ghana and possibly the rest of Ghana. The possible areas of policy interventions emanating from the findings of this study are schematically presented as follows;

The study established that post-secondary technical training had a significant positive impact on income diversification. This is a human capital gap which can be closed by giving considerable attention to post-secondary technical education in rural areas. Apprenticeship and vocational programmes must be prioritised over theoretical education. The old paradigm of formal education for all, without adequate attention to practical skills training of rural youth must be given a second look. Educational reform with considerable input in the technical development of youth for entrepreneurship is imminent in northern Ghana. The free Senior High school (SHS) programme were implemented in Ghana which offers free tuition and boarding facilities to all Ghanaian students including those based in rural areas, must redirect the focus to technical education. This is crucial because not all 500,000 graduates produced annually from the free SHS programme are able to make it into the universities. Those who fail to meet the cut-off point must be absorbed by the technical universities. Otherwise, we face a potential threat of increased cybercrime due to high rates of graduate unemployment in Ghana. It is recommended that the government improves the enrollment of SHS graduates in technical universities to acquire the technical skills needed to make a living. Given the budgetary constraints of the government, efforts must be made to catalyse multidonor support for the development and implementation of tailored technical education to Ghanaian youth in rural areas to transition them into the world of work or equip them to pursue entrepreneurship opportunities

A major driver of income diversification uncovered in this study was the amount of remittances received by the household head and spouse(s). Improved income from remittances can enable households to accumulate financial services or mobilize the initial capital to start their microenterprises or pursue other income generating activities. Access to credit is critical to enable rural households to acquire farm inputs and other productive assets, as well as provide working capital to set up and grow their farm enterprises and diversify into other non-farm activities. Limited access to capital or credit can be solved through improved financial inclusion of rural households. Facilitating access to other inclusive financial services such as savings, insurance, and payments can enable poor households to smooth their consumption, strengthen their resilience against climate-related shocks such as loss of income during extreme weather events as well as lower transaction costs and increase the speed and security of payments resulting in poverty alleviation. The policy advice that arises from this finding are three-fold. Firstly, there is a need to engender policies to overcome both demand-side and supply-side barriers that limit the availability, accessibility, usage, and affordability of inclusive financial services including credit, insurance, pensions, savings, investments, and payments faced by rural households who are often outside the fringes of formal financial providers. Secondly, the government should consider providing incentives to formal financial service providers that prioritise the delivery of inclusive financial services to rural households. Thirdly, philanthropic capital providers, multilateral development partners, or banks can provide catalytic or concessional financing to formal financial services providers to buy down the risks of delivering financial services to rural households as well as unlock additional private capital to increase the volume and number of financial products and services provided to rural households.

Access to mobile phones significant in rural household diversification. One of the ways mobile phones could be used to further advance income diversification in rural areas is to enhance mobile phone banking that can be conveniently accessed by rural people. In terms of the policy implication of this finding, the government should invest more in telecommunication and power infrastructure to improve mobile penetration and usage in rural areas. In addition, incentives such as tax breaks, loss carry forwards or import waivers or lower tariffs on telecommunication equipment imported into the country should be provided to private mobile network operators that extend their network services to rural areas. The Bank of Ghana and other regulatory bodies should also formulate policies and/or implement initiatives to increase the development of digital financial services such as mobile banking, micro credit, micro insurance, and mobile payment services, especially to rural households.

The study established that the relatively high degree of income diversification could increase diversified levels of incomes, which would allow householders to adapt better to income risks. In particular, income diversification was shown to also improve income for gaining food access. These findings are relevant and somewhat address issues in the government’s ongoing initiatives to improve the living standards of rural households, including the Planting for Food and Jobs program, the One-Village-One-Dam, and the One-District-One-Factory programs. High household income diversification could be advanced with the extensive promotion of rural cottage industries and other services such as rural tourism and agribusinesses.

From a political economy perspective of food security, the findings show that natural hazards and distance to market centres and hospitals significantly affected income diversification, overall income levels of households, and resilience to food poverty. Specifically, fall army worms and insect attacks were shown to be important in the survey area (Yendi and Nanumba North districts). An important role of the government is to provide rural households with mitigation assistance to reduce the impact of environmental stressors such as natural hazards, floods, bush fires, and conflicts. The government body responsible for disaster management such as the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO) should be resourced to become more proactive and responsive to the needs of rural people in the event of climate risk. There is the need for coordination and collaboration among other government agencies in information sharing and education of rural households to help them to better anticipate and cope with natural hazards. As a priority, the government must provide incentives to insurance companies which can lower the cost of insurance premiums for rural households who want to buy insurance to mitigate their exposure to these risks.