?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The choice of marketing channels holds significant implications for the economic welfare and stability of smallholder dry chilli farmers in India. This study aims to investigate the impact of participating in modern marketing channels on the economic welfare of smallholder dry chilli farmers. Dry chilli marketing in Andhra Pradesh encompasses both traditional and modern channels. Traditional avenues include Agricultural Produce Market Committees, while modern options involve linking with retail malls and utilizing the Kalgudi e-market online platform. The first stage of multivariate endogenous switching regression model (MESRM) reveals significant determinants influencing farmers’ participation in modern channels. Factors like access to extension services, education, technical support from ANGRAU and the Department of Agriculture, engagement with retail malls and e-markets, access to market information, and membership in Farmers’ Producer Organizations encourage farmers to adopt modern channels. The subsequent MESRM stage reaffirms these factors’ positive impact on household welfare across various marketing channels. The study’s focal point, Average Treatment Effects, highlights substantial income improvements for participants in modern marketing channels. The counterfactual analysis reveals that smallholder farmers engaging in modern marketing channels would have experienced lower gross economic welfare if they had not participated. These findings underscore modern channels’ vital role in enhancing smallholder farmers’ economic well-being. So, Government entities and agricultural institutions should prioritize developing linkages between farmers and retail malls. Ensuring robust digital infrastructure, including reliable internet connectivity and user-friendly online platforms, is essential to empower farmers in navigating modern channels effectively. Furthermore, policymakers should consider hybrid marketing strategies that seamlessly blend traditional and modern channels to cater to the diverse preferences of consumers. By acknowledging these findings and implementing corresponding policies, stakeholders can contribute to the growth and prosperity of smallholder dry chilli farmers, fostering sustainable development in the agricultural sector.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Market channel choice holds paramount importance for smallholder dry chilli farmers in India for boosting their income and overall economic prosperity. The decision-making process regarding selection of appropriate marketing channels is a multifaceted consideration that extends beyond the mere act of selling produce; it encompasses a complex web of factors that shape farmers’ livelihoods and the agricultural sector as a whole. The choice of marketing channels has a direct impact on income generated by smallholder dry chilli farmers. Different channels offer varying price points and profit margins, and opting for the right channel can substantially boost farmers’ earnings (Mmbando et al., Citation2017; Asfaw, Citation2018). Channels that provide direct access to consumers or processors, such as retail malls and electronic markets, often yield higher prices due to reduced intermediary involvement. This translates into enhanced financial well-being for smallholder farmers, enabling them to reinvest in their farms, improve their standard of living, and access better education and healthcare for their families. Furthermore, selection of a suitable marketing channel can significantly influence the stability and predictability of income for them. This stability mitigates risks associated from price fluctuations and thereby, empowers farmers to engage in long-term planning and investments, ultimately fostering agricultural growth. Marketing channel choice also intersects with the broader agricultural landscape, affecting supply chain efficiency and overall food security (Rao et al., Citation2012; Mabuza et al., Citation2014). Optimal channel selection can lead to reduced post-harvest losses and improved access to markets, benefiting both farmers and consumers. Moreover, channels that prioritize quality control and efficient distribution contribute to availability of safe and nutritious food products in a market (Shiimi et al., Citation2012; Pham et al., Citation2019).

Dry chilli marketing in Andhra Pradesh involves several channels for farmers to transact their produce. Three important channels of dry chilli marketing are traditional marketing channel (through Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs)) and two modern marketing channels viz., business linkages with retail malls and e-markets (online marketing platform). Regarding traditional marketing channel, APMCs are regulated marketplaces established by State Government and they facilitate both buying and selling of agricultural produce, including dry chillies, through a transparent auction system. The auction process allows farmers to obtain competitive prices based on demand and supply dynamics. They provide a regulated and fair-trading platform for farmers. However, within the APMC system, both farmers and traders are burdened with various fees and taxes. Moreover, the additional challenge of delayed payment for sales proceeds can significantly compound the difficulties already faced by farmers (Romero Granja & Wollni, Citation2018). The modern marketing approach involving sale of dry chilli through business linkages with retail malls signifies a transformative shift (Rao & Qaim, Citation2013). This contemporary channel offers a range of benefits to both farmers and consumers. Farmers gain access to a broader market through retail malls’ high footfall, ensuring stable demand, higher profits, and adherence to quality standards. Consumers, in turn, benefit from the convenience of sourcing fresh produce alongside their regular shopping, enjoying enhanced variety and quality assurance. However, challenges include maintaining consistent supply, addressing logistics concerns, and aligning with consumer preferences. Successful implementation necessitates effective collaborations between farmers and mall management, as well as a focus on quality control and understanding market demand. This innovative marketing approach holds promise for elevating agricultural practices, enhancing farmers’ income, and meeting the evolving preferences of modern consumers. Further, with the rise of digital technologies, e-markets or online marketing platforms have emerged as a modern channel for dry chilli marketing. These platforms connect farmers directly with buyers, including wholesalers, retailers, and consumers, through online transactions. Farmers can list their produce on these platforms, showcasing product details, quality, and pricing. Buyers can then place orders and make purchases online, facilitating a direct and transparent transaction. Kalgudi e-market is an online marketing platform that gained prominence in Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh, India. This platform aims to revolutionize the traditional agricultural marketing system and provide smallholder dry chilli farmers with direct access to buyers and consumers through digital technology. It offers smallholder dry chilli farmers the convenience of selling their produce from the comfort of their farms or local collection centers. Previously, farmers had to transport their produce to physical marketplaces, such as APMCs or wholesale markets, which could be time-consuming and costly. With Kalgudi e-market, farmers can list their produce online, showcasing details like variety, quality, and quantity, making it easily accessible to potential buyers across the region and beyond. This platform ensures fair and market-driven pricing for farmers, eliminate intermediaries and ensure remunerative prices for produce (Layne, Citation2016; Low et al., Citation2015; Park et al., Citation2014). It facilitates direct engagement between farmers and buyers, fostering a closer and more transparent relationship. It also facilitates for secure digital payments ensuring that farmers receive timely sales proceeds. It offers real-time market information and trends, allowing farmers to stay updated on the latest market conditions and pricing dynamics (Timothy et al., Citation2018).

So, each marketing channel has its benefits and challenges, and farmers may choose one or multiple channels based on their specific circumstances and market preferences (Poole, Citation2017). Some farmers may prefer the competitive prices and transparency of APMCs. Retail malls expand market reach that goes beyond traditional local markets and can potentially lead to increased sales volumes. Kalgudi e-market provide an innovative and technology-driven approach, offering access to a broader customer base beyond geographical limitations. As the agricultural marketing landscape continues to evolve, integrating traditional marketing channels with retail malls and e-markets can create a hybrid marketing approach that maximizes benefits of each channel. This integration provide smallholder dry chilli farmers to make informed decisions to optimize their sales and revenue while ensuring market access and profitability.

This study aims to explore impact of smallholder dry chilli farmers’ participation in modern marketing channels on their economic welfare through employing Multinomial Endogenous Switching Regression Model (MESRM). It offers a more complete understanding of the factors influencing marketing channel choice, accounting for both observable and unobservable elements that can impact the decision-making process (Asfaw et al., Citation2012; Burke et al., Citation2015; Olwande et al., Citation2015; Khanal et al., Citation2020). By using this model, the study aims to provide a nuanced and accurate analysis of factors driving modern marketing channels’ choice. Further, it provides a more robust and accurate estimation of the relationship between marketing decisions and their effects on continuous outcome variable (Deb and Trivedi (Citation2006a, Citation2006b); Morescalchi (Citation2016)). In the specific context of Andhra Pradesh, the dry chilli marketing landscape offers a variety of channels for farmers to transact their produce, including traditional avenues like APMCs and modern alternatives such as retail malls and e-markets. Each channel presents distinct opportunities and challenges for smallholder farmers, influencing their economic outcomes and overall well-being. In this context, this study aims to explore the impact of marketing channel choice on the economic welfare of smallholder dry chilli farmers in Andhra Pradesh, India, with a focus on traditional avenues like APMCs and modern alternatives such as retail malls and e-markets. By assessing factors influencing farmers’ channel choice, including access to information, market dynamics, and institutional support, the research seeks to identify the benefits and challenges associated with each option. Additionally, the study aims to evaluate the optimization potential of integrating traditional and modern channels, employing the MESRM to provide a nuanced analysis. Ultimately, the findings aim to inform policymakers and practitioners, facilitating evidence-based interventions to enhance farmers’ economic prosperity and agricultural development in the region.

Despite ample literature on agricultural marketing channels, significant gaps persist. Firstly, existing studies often overlook the multifaceted nature of farmers’ decision-making processes, failing to consider factors like access to information, market dynamics, and institutional support. Secondly, there is a dearth of research examining the determinants and implications of smallholder farmers’ engagement with modern marketing channels, especially digital platforms like e-markets. To address these gaps, rigorous empirical inquiry employing advanced econometric techniques is essential. Such research can provide nuanced insights into the factors driving farmers’ channel choices and their impacts on economic welfare. By filling these knowledge gaps, researchers can inform policymakers, development practitioners, and farmers themselves, facilitating informed decision-making and interventions aimed at enhancing farmers’ economic prosperity and agricultural development.

2. Review of literature

Adinan et al. (Citation2022) examined tomato seed variety adoption and its impacts on farmers’ wellbeing in selected agroecological zones of Ghana. Improved varieties were positively influenced by factors like sex, household income, size, primary occupation, FBO membership, access to credit, and market perception. However, tertiary education, extension contact, and yield perception negatively affected adoption. Household welfare was positively influenced by income, size, credit access, residency, and negatively affected by tertiary education, extension contact, and yield perception. Adoption of specific varieties increased household expenditure and assets, and adopting ITSV had the most significant positive impact on improving household welfare, resulting in increased income for farmers.

Alhassane et al. (Citation2021) examined the joint impact of market participation decisions on farm profit per hectare in Senegal, using a MESRM. The findings showed that transaction costs significantly influenced market participation choices both for food crops and cash crops. Regarding food crops, the joint market participation (both input and output markets) emerges as a strategy to optimize profit per hectare. However, for cash crop (groundnuts) involvement in input market is not essential to maximizing farm profit.

Utilizing the home-scan dataset, Wang et al. (Citation2018)’s study delves into the shopping behaviour of urban Chinese consumers across online and offline channels, using yogurt as a case study. The findings affirm the inherent advantages of e-commerce in cultivating consumer loyalty when compared to traditional offline retail channels. Moreover, our analysis reveals distinct business models between online and offline markets, even for the same brand, underscoring the independent nature of these channels. Evidence emerges suggesting brand loyalty among online shoppers, a phenomenon not as prominent in the offline sphere.

Varma (Citation2018) analyzed the determinants for SRI adoption in major rice-producing states in India and its effects on rice yield and household income. The findings from MESRM indicate that factors such as household assets, access to irrigation, and information positively influence SRI adoption. Conversely, factors like landholding size, years in rice cultivation, and concerns about poor yield decrease likelihood of adopting SRI. Regarding welfare outcomes, all combinations of SRI adoption, including plant management, water management, and soil management showed positive influence on rice yield. However, the effects on household income are more varied. Policymakers can utilize this information to design targeted interventions that encourage SRI adoption among rice farmers, ultimately leading to improved agricultural productivity and livelihoods in India.

Timothy et al. (2018) analyzed the impact of direct marketing on farm sales through employing MESRM. The findings indicate that direct marketing, while associated with higher sales overall, has differential impacts on female farmers compared to male farmers. The research reveals a distributional effect on farmers, specifically highlighting sales declines for female farmers when they engage in direct marketing channels. The study further reveals that the sales gap between male and female farmers widens when female farmers opt for direct marketing to consumers only, increasing by 5.3 per cent. This implies that female farmers may experience a more significant disadvantage compared to male farmers when selling directly to consumers. Additionally, the sales gap between male and female farmers widens even more when direct marketing is targeted to both consumers and retailers, with an increase of 11.6 per cent in the gap. These findings call for a careful consideration of gender-specific outcomes when designing agricultural marketing policies and interventions. By adopting treatment-outcome models that explicitly account for selectivity, researchers and policymakers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the implications of different marketing outlet choices, contributing to more equitable and sustainable agricultural development.

These studies collectively emphasize the significance of marketing channel choice and its determinants in influencing farmers’ economic welfare and agricultural outcomes. The findings underscore the need for targeted interventions and policies that consider the diverse needs and constraints faced by farmers, particularly regarding access to markets, resources, and information. Moreover, the utilization of advanced econometric techniques, such as the MESRM, reflects a methodological advancement aimed at providing a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics underlying farmers’ marketing decisions and their welfare implications. Overall, these studies contribute valuable insights to the field of agricultural economics, informing policymakers and practitioners in designing effective strategies to enhance farmers’ livelihoods and promote sustainable agricultural development.

While not all of these reviews directly focus on modern marketing channels, they collectively underscore the importance of various factors that can influence marketing choices and their impacts on farmers’ livelihoods. Modern marketing channels, including e-commerce and online platforms, are becoming increasingly relevant in the context of agriculture, offering opportunities for improved market access and profitability, but also posing unique challenges, especially in terms of gender disparities and education. Many studies focus on specific crops or regions, limiting the generalizability of their findings. The current study seeks to contribute to a broader understanding of marketing channel choices and their impacts across different agricultural contexts, with a specific focus on the dry chilli sector in India. Additionally, while some studies explore the determinants of adoption or market participation, there is a lack of research that comprehensively examines the joint impacts of these decisions on farmers’ economic welfare. By employing advanced econometric techniques, such as the MESRM, the current study intends to fill this gap by providing a more holistic analysis of the factors influencing marketing channel choices and their subsequent effects on farmers’ well-being. Overall, by addressing these limitations and gaps, the current study aims to provide valuable insights that can inform policymakers and practitioners in designing more effective and inclusive agricultural marketing strategies.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Selection of sample farmers and data collection

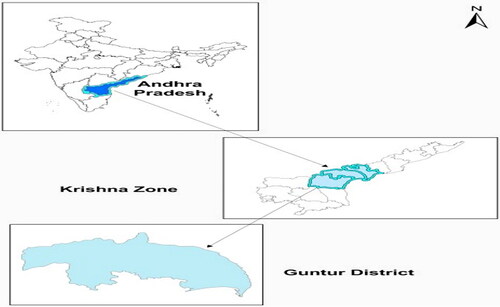

Dry chillies hold a significant position in Indian agriculture, occupying 0.73 million hectares of cultivation in the 2020–2021 period (Agricultural Statistics at a Glance). Among all States, Andhra Pradesh stands out as the leading producer of dry chillies (0.80 million tonnes), with Guntur serving as Asia’s largest market for this crop (Season & Crop Report, Citation2021). APMC, Guntur acts as a hub, receiving dry chillies from multiple production areas from various States, which notably influences Guntur’s chilli prices. This district enjoys a competitive edge due to factors like labour availability, specialization, mechanization, and effective irrigation systems. The initial stage of the study involved purposefully selecting Andhra Pradesh state and Guntur district within the Krishna zone due to their recognized potential in dry chilli production (). Subsequently, individual farmers actively involved in both cultivating and trading dry chillies across various marketing channels were identified. These channels included the traditional channel (APMC), as well as two modern marketing avenues: retail malls and the Kalgudi e-market platform. The selection process for these respondents utilized a probability proportion to size approach, ensuring a representative sample (n = 760) that encompassed diverse participants from different marketing channels (). However, it’s noteworthy that the analysis didn’t encompass the channel involving local processors, primarily due to the limited number of farmers engaged in this specific channel. With fewer than 30 farmers involved in transacting their produce to local processors, the statistical analysis refrained from including this channel. Data collection was conducted using a structured schedule to gather cross-sectional data from the sample farmers on various covariates and outcome variables specifically related to the Kharif season of 2022-23 (). Before the actual survey, the schedule underwent a pre-testing phase in non-sampled villages to ensure its effectiveness in collecting the required data. Our analysis utilized both quantitative and qualitative techniques. The Stata software version 17 was used to provide descriptive statistics, such as the mean, standard deviation and variance of the respondents, and to also estimate the maximum likelihood estimates.

Table 1. Specification of market channel choice combinations and sample farmers.

Table 2. Variable types and definitions.

Each element is a binary variable of their combination between Retail Malls (R) and Kalgudi e-Market (K). Subscript 1 = preferred channel and 0 = otherwise.

3.2. Analytical framework

When studying the participation in modern technology as a binary choice (whether to participate or not), researchers have employed various econometric techniques to address challenges posed by selection bias. They aim to accommodate the reality that the choice to adopt a technology might not be arbitrary and could be influenced by both observable and unobservable variables. If technology selection involves more than two choices (say, R1K0 or R0K1 or R1K1) as in this study, researchers have to turn to more specialized methodologies to handle selection bias.

Several methods have been utilized in previous studies to address selection bias in binary technology adoption cases. These include the Endogenous Switching Regression Model (ESRM) (Takam et al., Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2021), treatment effects models (Zhu, Citation2021), inverse probability weighted regression adjustment (Khonje et al., Citation2018; Zhang & Ma, Citation2021), and the conditional mixed process model (Zhu et al., Citation2021). However, in situations where technology choices are not just binary but involve multiple options, both the multivariate treatment effects model (Zhou & Ma, Citation2022; Essilfie, Citation2018, Ma et al., Citation2022) and MESRM (Pan et al., Citation2021; Setsoafia et al., Citation2022) have gained popularity in addressing the selection bias challenge. Between these two approaches, the multivariate treatment effects model is considered non-parametric and lacks the capacity to capture how the selected control variables impact the dependent variables. Additionally, this method only addresses the selection bias that emerges from observable factors. In contrast, MESRM overcomes the limitations of multivariate treatment effects model (Wencong et al., Citation2021). It handles selection bias issues of both observed and unobserved factors, offering a comprehensive parametric estimation of the relationship. Further, it addresses potential issues related to endogeneity and heteroscedasticity (Oduniyi et al., Citation2022). As a result, it provides a more robust framework for understanding the complex interplay between technology selection and its determinants. Given these considerations, this study has chosen to employ the MESRM for its empirical analyses, as it offers a more complete understanding of the factors influencing market channel choice, accounting for both observable and unobservable elements that can impact the decision-making process.

The MESRM is a two-stage estimation process that involves both selection equation and substantive equations. First stage of MESRM involves estimation of Multinomial Logit (MNL) model that examines farmers’ choices of modern market channel choices (respondents are categorised into mutually exclusive groups), while second stage entails estimation of ESRM to study determinants of farmers’ GEW based on chosen category of marketing channel (Kassie et al., Citation2015; Khonje et al., Citation2018; and Manda et al., Citation2021).

Stage 1: Multinomial selection (logit) model

In the initial stage, farmers were postulated to optimize their GEW status, denoted as Yi, by evaluating the above four available alternative marketing channels. The criterion for a farmer to opt for a particular channel ‘j’ was that it should yield a greater expected GEW compared to any other strategy (Kumar et al., Citation2019; Danso Abbeam & Baiyegunhi, Citation2018). The latent variable encapsulates the anticipated GEW, shaped by a combination of observed factors (). Additionally, unobservable factors also play a role in influencing this GEW outcome. The formulation is as follows:

(1)

(1)

where, the term

encompasses the observed exogenous variables. The error term,

encapsulates unobservable characteristics that might influence the decision-making process. It is presumed that the covariate vector

is not correlated with the unique stochastic element,

thus, fulfilling the condition E(

|

) = 0 implying that error terms are adhering to the principle of Independent Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) hypothesis. The structure of selection model (1) consequently leads to multinomial logit framework, wherein probability of choosing marketing channel ‘j’ ie., (pij) is expressed as follows (McFadden, Citation1973):

(2)

(2)

Stage 2: MESRM:

In the subsequent stage, the analysis employs the ESRM approach to explore the impact of each response package (ie., marketing channel) on the well-being of farmers. This is achieved through application of a selection bias correction model. A farmer encounters four distinct regimes, denoted as ‘j’, with regime j = 1 serving as the reference category (representing ‘APMC’ channel). The equation that defines the well-being status for each of these potential regimes is expressed as follows:

(3)

(3)

where

represents outcome variable of the ith farmer associated with selected regime ‘k’,

represents a vector of explanatory variables or exogenous covariates, β is the vector of parameters, and

and

are random disturbance terms.

is observed if, and only if, modern marketing channel ‘k’ is participated, which occurs when

> maxm≠k (

). However, if the εk and ε1 are not independent, OLS estimates obtained from EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) will be biased. Thus, consistent estimation of Xi requires inclusion of selection bias correction terms of modern marketing channels ‘m’ in EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) . In MESRM, a linearity assumption is made: (δik/εi1 …… εik) =

(εim - E(εim)) (Dubin & McFadden, Citation1984). By design, there is no correlation between error terms in Equationequations (2)

(2)

(2) and Equation(3)

(3)

(3) . Using this assumption, EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) is represented as:

(4)

(4)

where

is covariance between error terms δ and ε;

’s are error terms with an expected value of zero, and

is Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR) computed from MESRM estimate of EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) (Bourguignon et al., Citation2007) as:

(5)

(5)

where

defines correlation coefficient of three error terms, ε, δ and

. However, to address the potential heteroscedasticity issue stemming from generated regressor

, we mitigated this concern by employing bootstrap errors.

While IVs are suggested in the literature for robust estimates, selecting suitable instruments can be complex. Chamberlain and Griliches (Citation1975) argued that IVs are not always imperative for identifying equation systems. Nonetheless, authors such as Bourguignon et al. (Citation2007); Danso-Abbeam & Baiyegunhi, Citation2018; Teklewold et al. (Citation2013) underscore the relevance of IVs in the alternative selection model presented in EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) . In line with this, we employed the variable, ‘FPO membership’ as instrument for model identification.

3.3. Estimation of Average treatment effects

The MESRM framework facilitates computation of both average treatment effect on treated (ATT) and average treatment effect on untreated (ATU) individuals. This was accomplished through a meticulous comparison of anticipated outcome between those who underwent the treatment (i.e., participants in modern marketing channels) and those who do not (i.e., non-participants), both within the actual and counterfactual scenarios. By focusing on the expected outcomes under these contrasting situations, we gained valuable insights into the transformational effects brought about by the treatment (participation in modern marketing channels). This entails conducting counterfactual analysis (Di Falco & Veronesi, Citation2013) to ascertain impact of participation in modern marketing channels (ie., retail mall or e-market channel or joint participation). This involves comparing the anticipated outcomes of participants who have chosen to participate in modern marketing channel with those non-participants.

The ATT is computed for both actual scenario (with adoption) and counterfactual scenario (without adoption) using the following approach:

Participants (actual expectations observed in the sample):

Participants, had they decided not to participate (counterfactual expected outcomes):

EquationEquations (6a)(6a)

(6a) and Equation(6b)

(6b)

(6b) denote the actual observed expectations within the sample, while EquationEquations (7a)

(7a)

(7a) and Equation(7b)

(7b)

(7b) depict the counterfactual anticipated outcome (Khonje et al., Citation2015). To compute ATT, the disparity between EquationEquations (6a)

(6a)

(6a) and Equation(7a)

(7a)

(7a) was computed. This calculation can be expressed as follows:

(8)

(8)

Similarly, ATU is determined by the difference between EquationEquations (6b)(6b)

(6b) and Equation(7b)

(7b)

(7b) , which can be expressed as follows:

(9)

(9)

The MESRM offers a sophisticated approach to analyzing the interplay between farmers’ decisions regarding market channel selection and their subsequent economic welfare. However, like any analytical framework, it is not without its limitations. One notable constraint is the assumption of exogeneity, which implies that the explanatory variables are independent of the error term. Violations of this assumption can lead to biased estimates and erroneous conclusions. Moreover, endogeneity issues may arise when certain variables are simultaneously determined with the outcome of interest, potentially confounding the results. Additionally, MESRM requires comprehensive and high-quality data to accurately capture the complexities of farmers’ decision-making processes and economic outcomes. Model specification is another critical consideration, as slight variations in the specification can yield different results. To mitigate these challenges, researchers often conduct robustness checks and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of their findings. Despite these limitations, MESRM remains a valuable tool for shedding light on the intricate relationships between market channel choices and farmers’ welfare, providing insights that can inform policy interventions aimed at enhancing agricultural development and livelihoods.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Summary statistics

offers a comprehensive overview of descriptive statistics pertaining to various variables, categorized by different marketing channel choices and the pooled sample (Khonje et al., Citation2018; Lu et al., Citation2021; Ng’ombe et al., Citation2017). This dataset sheds light on potential factors influencing the decisions made by farmers regarding their preferred marketing channels. When examining indicators related to economic outcomes, such as household expenditure, assets creation, and savings, distinct differences emerge across various marketing channels. Notably, farmers engaging with e-market and retail mall + e-market options display significantly higher mean values. This is due to broader consumer reach and efficient price realization opportunities these modern marketing avenues provide.

Table 3. Summary statistics of variables, by marketing channel choice and pooled sample.

The enhanced returns could be encouraging farmers to shift toward these options in search of improved economic prospects. Accordingly, GEW, a comprehensive measure of well-being, exhibits variation among marketing channel choices. Specifically, those participating in e-market and retail mall + e-market channels seem to experience elevated GEW outcomes. This could be due to multiple factors viz., better income streams, reduced post-harvest losses, and a potential decrease in intermediaries, leading to more equitable returns for farmers. Access to crucial services and information emerges as another pivotal factor. The higher mean values for access to extension services, the internet, technical support, and market-related information among e-market and retail mall + e-market participants underscore role of technology and knowledge dissemination. These channels may offer convenient access to expert guidance, real-time market trends, farming best practices and empowering farmers that translate into increased profitability. When considering EDU, FPO, and FE, the variable patterns appear intricate. However, higher mean values observed within e-market and retail mall + e-market selections indicate these channels are availed by educated farmers, those involved in FPOs, and individuals with diverse farming experiences (Kabunga et al., Citation2012). Interestingly, mean values concerning ‘distance to market’ display significant disparities, particularly disfavouring APMC option. The accessibility to modern marketing channels could be mitigating transportation challenges and facilitating a quicker flow of produce, which in turn might lead to reduced spoilage, wider consumer outreach and enhanced returns for farmers. Moreover, the inclination towards technology and support is evident through higher mean values for access to internet and technical support in e-market and retail mall + e-market selections (Jari, Citation2009; Matson et al., Citation2013). This underscores the potential role of technology and expert guidance in facilitating farmers’ effective engagement with these channels. Notably, the land holding size (LHS) variable demonstrates relatively consistent mean values across various marketing channels. This observation implies that land size might not be the pivotal driving factor in farmers’ choices among these channels. These findings point toward a complex interplay of multiple factors that steer farmers’ decisions when selecting their preferred marketing channels. The potential for amplified income, heightened market accessibility, technological adoption, and improved services emerges as the prominent motivators. This nuanced understanding of driving forces behind marketing channel choices can guide policy-makers and stakeholders in formulating strategies to enhance smallholder farmers’ access to profitable marketing options and, in turn, elevate the overall well-being of agricultural practices (Georges et al., Citation2016; Camara, Citation2017).

4.2. Determinants for market channel choice

presents the outcomes of a MNL model analysis, shedding light on marginal effects of diverse determinants on sales within different marketing channels. To better comprehend the implications of these results, it is essential to compare them against the baseline category, which consists of farmers engaging in the traditional marketing channel through APMC.

Table 4. Marginal effects for the determinants of modern marketing channels# –Multinomial logit model (First stage of MESRM).

The application of Wald test to assess joint equality of regression coefficients [χ2(27) = 268.81; p = 0.000], reveals that MNL model possesses substantial explanatory power and effectively captures the data’s essence (Di Falco et al., Citation2011). To further validate the chosen IV, namely FPO membership, an admissibility test was performed and its significant value (Joint IV Wald χ2 = 9.55, p = 0.023) reinforces the credibility of selected instrument (Di Falco et al., Citation2011). This validation aligns seamlessly with the observations of Nguyen-Van et al., Citation2017, emphasizing the holistic depiction of impact magnitudes through marginal effects within individual probability models.

Notably, the results indicate that magnitudes of marginal effects exhibit variability across the spectrum of modern marketing channels. ‘Access to extension services’ is a significant factor across all channels, with positive impacts on sales. Compared to APMC baseline, farmers enjoying extension services are likely to participate in both retail malls and e-markets, as it equips them with valuable insights and knowledge and allow them to optimize their marketing strategies. Regarding ‘education’, this variable exhibit noteworthy effects on sales across all channels (Mwaura et al., Citation2014). Farmers with higher levels of education demonstrate enhanced participation in both retail malls and e-markets compared to the APMC baseline, as they possess a deeper understanding of market dynamics and are better positioned to adapt to shifting consumer preferences (Marenya and Barret, Citation2007). Further, the receipt of technical support from ANGRAU, Department of Agriculture, Retail malls and Kalgudi e-market showed positively influences on sales in retail malls and e-market, aligning with the APMC baseline. This will also facilitate to attract consumers within both physical retail mall and virtual realm of e-market environments. Similarly, ‘access to market information’ emerges as a consistent influencer for participation across all channels, albeit with a slightly weaker effect on retail malls. Compared to the APMC baseline, farmers enjoying market information are better poised to make informed decisions regarding pricing, demand, and supply. This will provide them a competitive edge in navigating modern marketing channels. Similarly, ‘FPO membership’ emerges as a significant and positive factor influencing sales across a range of marketing channels, including e-markets, retail malls, and the combined channel of retail mall + e-market. This finding suggests that FPOs play a valuable role in enhancing farmers’ performance and sales outcomes in these diverse marketplaces. This is because, both in retail malls and e-markets, FPO membership enhance access to a broader customer base and help to negotiate better terms due to their collective bargaining power. Additionally, the joint marketing efforts of an FPO might enhance brand recognition and credibility, further bolstering sales. The influence of FPO membership is also notable in the combined channel of retail mall + e-market. Here, the synergy between physical retail spaces and online platforms will provide unique opportunities for FPO members. The FPO’s presence in both realms allows farmers to cater to different consumer preferences – those seeking in-person interactions and those opting for online convenience. The FPO’s collective strength can ensure a consistent and reliable supply of products across both channels, strengthening its market position and contributing to increased sales.

However, distance to market plays a role predominantly in retail malls, where a shorter distance to the market corresponds to higher sales. This signifies that physical proximity to retail malls significantly enhances sales opportunities (Muricho et al., Citation2015). In contrast, the variable’s effect on e-markets and the combined channel remains statistically insignificant. This is because, e-markets are digital platforms that allow farmers to enjoy direct market linkages with buyers online, regardless of their geographical location. Since e-markets transcend physical distances, the impact of proximity to the market might be diluted. Factors such as product quality, online visibility, and competitive pricing could hold greater sway in e-markets, overshadowing the effect of physical distance. Regarding joint market participation (retail mall + e-market), it is possible that these two channels offset each other’s effects. Retail malls benefit from physical proximity, which facilitates in-person transactions, while e-markets rely on virtual accessibility. When both channels are combined, farmers might experience a balance between the effects of physical distance and online presence, resulting in the non-significant influence of this variable. This scenario highlights the complex interplay of factors in hybrid marketing strategies. In contrast, the traditional APMC channel and retail mall channel places a premium on immediate physical access. So, a shorter distance to these markets becomes a crucial advantage in enhancing market transactions. Thus, both APMC and retail mall channels retains its emphasis on physical proximity, contributing to the significant influence of the ‘distance to market’ variable on market participation.

‘Farming experience’ presents an intriguing finding, indicating that more experienced farmers might encounter challenges in adapting to the digital landscape of e-markets, however non-significant. In comparison with APMC baseline, the experienced farmers might need additional support to effectively leverage e-marketing platforms. This observation diverges from the conclusions drawn by Jagwe et al. (Citation2010) and Sigei et al. (Citation2013), underlining the complex and context-specific nature of the relationship between farming experience and e-market adoption. It is interesting that ‘landholding size’ did not emerge as a significant determinant of market participation across any of channels explored. This finding implies that landholding size does not substantially influence sales outcomes in modern marketing channels compared to the APMC baseline. This departure from previous findings, such as those of Olwande et al. (Citation2015) and Owusu and İşcan, (Citation2021), underscores the unique dynamics at play in modern marketing landscapes.

These findings underscore the importance of factors like access to extension services, education, technical support, and market information in shaping farmers’ success within modern marketing channels (Enete & Igbokwe, Citation2009; Omiti et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, it highlights the relevance of channel-specific impacts, particularly in case of technical support and farming experience. Additionally, the positive influence of FPO membership provides insight into the potential benefits of collaborative efforts in navigating modern marketing landscapes.

The findings presented in the study contribute significantly to the existing literature on agricultural marketing channels, drawing upon and expanding upon insights from previously reviewed articles. The current study builds upon Adinan et al. (2022) this by highlighting the role of similar factors, such as access to extension services, technical support, and FPO membership, in shaping farmers’ success within modern marketing channels. Moreover, Alhassane et al. (Citation2021) explored the impact of market participation decisions on farm profit per hectare, emphasizing the significance of transaction costs and market dynamics. The present study extends this discussion by examining how factors such as distance to market and joint market participation influence sales outcomes across different marketing channels, providing nuanced insights into the complex interplay of factors affecting farmers’ economic welfare. In line with Wang et al. (Citation2018), this study underscores the growing importance of e-markets and online platforms in facilitating direct transactions between farmers and buyers, highlighting the potential of digital technologies to transform agricultural marketing landscapes and enhance farmers’ economic prosperity. Overall, the findings of the current study contribute valuable insights to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the determinants of farmers’ sales outcomes in modern marketing channels. By emphasizing the importance of access to information, institutional support, and collective action, while also acknowledging the unique challenges and opportunities associated with different marketing channels, the study informs policymakers and practitioners in designing effective strategies to enhance farmers’ market participation and economic welfare in an evolving agricultural landscape.

4.3. Effect of modern marketing channels on GEW

encapsulates the outcomes of a second-stage MESRM, investigating the intricate determinants of GEW in relation to diverse marketing channel preferences. This analytical framework delves into factors that influence households’ choices between marketing avenues, such as Retail Mall, e-Market, and Retail Mall + e-Market, while simultaneously examining the repercussions of these choices on household well-being.

Table 5. Determinants of GEW based on marketing channel choice – second stage of MESRM.

One striking and noteworthy observation is the presence of consistently positive and statistically significant coefficients across all marketing channels in relation to the variable ‘access to extension services.’ This consistent pattern emphasizes the crucial role that extension services play in improving a farmer’s GEW. These services encompass crucial insights, training, and technical knowledge that substantially enhance both agricultural production and marketing practices. This effect is particularly pronounced in digital marketing (e-Market) and hybrid platform (Retail Mall + e-Market), as extension services equip farmers with necessary skills to navigate these novel avenues effectively. This empowerment enables them to harness digital tools, access larger markets, and thereby contribute to enhanced farmer’s GEW. Furthermore, positive and statistically significant coefficients for ‘education’ across all marketing channels underscore its crucial role in shaping farmer’s GEW. Educated households possess heightened decision-making capabilities, a deeper understanding of market dynamics, and a greater adaptability to changing economic conditions (Teklewold, Citation2016). In the realm of digital marketing platforms, the value of education becomes even more evident. Educated individuals are equipped to leverage the potential of digital tools and strategies, allowing them to navigate the complexities of the digital landscape effectively. Consequently, educated households negotiate favorable terms, tap into a wider array of market opportunities, and ultimately contribute to the overall enhancement of their GEW. Although the impact of ‘internet access’ is not statistically significant for the traditional Retail Mall setting, its positive and significant effects on e-Market and Retail Mall + e-Market choices underscore its pivotal role in enhancing GEW within the digital realm. Internet access provides households with real-time access to market information, trends, and consumer preferences (Enete & Igbokwe, Citation2009; Omiti et al., Citation2009). This empowers them to tailor their products to align with market demands, engage directly with buyers, and transcend geographical limitations. The convenience and efficiency of digital transactions facilitated by internet access contribute to increased income generation and, consequently, improved farmer’s GEW (Park et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2018). The nuanced impact of ‘technical support’ emerges when closely examining the coefficients. The positive coefficients for e-Market and Retail Mall + e-Market underscore the instrumental role of expert guidance in effectively navigating these platforms. Technical support in the context of digital marketing could encompass advice on online marketing strategies, platform utilization, and troubleshooting. Similarly, the positive coefficient observed for technical support within the Retail Mall channel underscores the profound significance of receiving expert guidance and assistance, particularly concerning the transacting of quality outputs (Habwe et al., Citation2008). This finding highlights the importance of technical support in ensuring transactional excellence, buy-back agreements and realization of higher prices that align with product quality. The ‘access to market information’ is crucial, as reflected by the positive coefficients for e-Market and Retail Mall + e-Market. This underscores the pivotal role of market information in digital and hybrid marketing contexts. Real-time access to market data empowers households to make well-informed decisions, tailor product offerings, and capitalize on emerging trends. In the dynamic landscape of e-market, where information dissemination is rapid, staying updated ensures timely decision-making. Similarly, in the scenario of Retail Mall + e-Market, the information regarding product quality and pricing can significantly impact profitability and, consequently, overall GEW (Momanyi et al., Citation2016).

The positive ‘farming experience’ coefficient in establishing linkages with retail malls for transacting dry chili reveals the favourable standing of experienced farmers in traditional marketing. This expertise extends to benefit from buy-back arrangements and maintaining quality standards. By aligning with local preferences for fresh produce, experienced farmers augment retail mall success. This multifaceted advantage emphasizes their pivotal role in elevating the quality and appeal of retail mall offerings and furthering farmer’s GEW.

The significant positive coefficient for ‘landholding size’ in the traditional Retail Mall setting underscores the benefits of economies of scale and increased bargaining power for larger landholders. Conversely, the absence of significance in e-Market and Retail Mall + e-Market contexts signify that digital technology operates in a scale-neutral manner, granting GEW based on factors beyond land size. This nuanced interplay between landholding size and marketing channels sheds light on the changing dynamics of agricultural marketing in the digital age.

It is interesting that ‘FPO membership’ emerges significant for retail mall, e-Market and Retail Mall + e-Market choices. This underscores the collective strength offered by FPOs, which empower households with improved negotiation power, better access to resources, and enhanced market linkages (Gyau et al., Citation2016; Ma & Abdulai., Citation2017; Hoken & Su, Citation2018).

The consistent negative coefficients for ‘distance to market’ across all marketing channels affirm the positive impact of reduced proximity to markets on farmer’s GEW. Reduced distance brings about lower transportation costs, minimized post-harvest losses, and improved market access. In the digital and hybrid marketing landscape, shorter distances could lead to quicker delivery times, lower transportation expenses, and enhanced customer satisfaction, collectively contributing to improved GEW (Muriithi and Matz., 2014; Danso et al., Citation2017).

Furthermore, the observed positive and statistically significant values of the IMR (λ) are notable for the categories of retail malls when compared to base category, as well as for e-market and joint market participation (retail mall + e-market) in comparison to other categories. These outcomes suggest about selectivity bias in the data. This phenomenon could be attributed to the phenomenon of farmers actively choosing retail malls over APMC, and similarly, opting for e-market or retail mall + e-market instead of APMC and retail malls, respectively. This kind of selective behaviour might be driven by specific attributes of certain farmers. The noteworthy positive and significant values of IMRs associated with modern marketing channels, such as retail malls, e-market, and retail mall + e-market, indicate that those farmers who participated in these channels exhibited a tendency to achieve heightened levels of GEW. These results indicate self-selection bias at play, wherein farmers who engage with these modern marketing channels possess advantageous characteristics that lead to enhanced economic outcomes.

Within the context of the multinomial framework, the coefficients (m1, m2 & m3) that pertain to the comparison of retail malls with the APMC category, e-market with other categories, and retail malls + e-market with APMC and retail malls, have been observed to display positive and statistically significant values. This pattern of coefficient behaviour signifies a clear inclination among farmers towards the adoption of modern marketing channels. For instance, positive and significant coefficients observed for e-market highlight farmers’ preference for embracing digital and online platforms in marketing of dry chillies. The non-significance of ‘sigma’ reinforces the notion that the estimates generated from the model are robust (non-heteroscedastic) and efficient. It suggests that any potential variance in the error terms is not systematically related to the predictors under investigation. This assurance is bolstered by the fact that heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors were utilized in the analysis, ensuring that potential heteroscedasticity effects were appropriately accounted for.

These findings underscore the pivotal role of modern marketing channels, particularly e-Market and Retail Mall + e-Market, in enhancing farmers’ GEW in the context of marketing dry chillies. Access to extension services, education, internet connectivity, technical support, and market information emerges as critical determinants shaping farmers’ channel preferences. These factors empower farmers with the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to effectively navigate digital platforms, access larger markets, and optimize pricing strategies. Furthermore, FPOs play a significant role in enhancing farmers’ collective bargaining power and access to resources. Proximity to markets and the adoption of modern channels contribute to efficiency gains, reduced transportation costs, and minimized post-harvest losses, ultimately enhancing economic viability and sustainability. By adapting to changing market dynamics and embracing innovation, farmers can position themselves for long-term success, contributing to the overall development and resilience of the agricultural sector.

4.4. Impact of participation in modern marketing channels on GEW

presents estimations of both ATT and ATU concerning participation of farmers in modern marketing channels. Remarkably, across all three choices of modern marketing channels, the findings reveal consistently positive effects for both ATT and ATU. This intriguing pattern suggests that, irrespective of the specific modern marketing channel chosen by the farmers, participants tend to experience higher levels of GEW in comparison to their base-line counterparts. To illustrate this effect, let’s consider the case of R0K1 participants. The ATT for these participants signifies a notable increase of 46.77 per cent (Rs. 124239.70) in their GEW compared to those who did not participate. Similarly, for farmers who opted for R1K0 and R1K1, the outcomes were similarly positive. R1K0 participants witnessed a substantial 39.08 per cent rise (Rs. 91248.21), while R1K1 participants experienced a considerable 41.09 per cent increase (Rs. 100733.41) in their respective GEW, as compared to non-participating peers. This encouraging result aligns with findings of earlier research conducted by Yang et al. (Citation2018) and Varma (Citation2018).

Table 6. Average expected GEW from modern marketing channels of dry chillies (Rs.).

Furthermore, the counterfactual effect delves into what the participants’ outcomes would have been if they hadn’t engaged with modern marketing channels. Across all counterfactual (ATU) scenarios, smallholder farmers who chose to participate in these channels would have experienced lower GEW had they not engaged with modern marketing options. This emphasizes the substantial positive impact of modern marketing participation. For instance, considering those who abstained from all modern marketing channels (R0K0), their income would have risen by Rs. 40,552.69 if they had opted for R0K1 participation. Similarly, non-participating farmers adopting R1K0 and R1K1 would have experienced income increments of Rs. 36,648.70 and Rs. 39,720.10, respectively. This underscores that adopting R1K0, R0K1, or R1K1 led to significantly higher income levels when compared to non-participating alternatives.

This compelling evidence stemming from both ATT and ATU scenarios underlines that adoption of modern marketing channels—be it R1K0, R0K1, or R1K1—results in significantly higher GEW for participating farmers when compared to their non-participating counterparts. This substantial positive impact of modern marketing channels on farmers’ GEW is attributed to various interconnected factors. Enhanced market access, reduced intermediation, improved price realization, and increased bargaining power contribute to higher income. Participation facilitates the exchange of critical market information, technology adoption, and quality-focused production. Efficient supply chains in these channels minimize wastage and maintain product freshness, further enhancing economic gains. The collective effect of these factors drives better market opportunities and equitable compensation. Farmers’ engagement in modern marketing channels unlocks their potential, aligns with consumer preferences, and optimizes operational efficiency, resulting in elevated income and improved overall economic well-being.

These findings provide valuable insights for both research and policy. Beyond highlighting the significance of access to extension services, education, internet access, technical support, and market information, this study underscores the multifaceted nature of factors shaping farmers’ success in contemporary agricultural markets. Future research endeavours could explore the nuanced interactions between these determinants and identify additional variables influencing farmers’ decisions and outcomes within modern marketing landscapes. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could offer insights into the sustainability and long-term impacts of farmers’ participation in digital platforms and hybrid marketing models. On the policy front, the findings advocate for targeted interventions aimed at bolstering extension services, expanding digital infrastructure, fostering collaboration among FPOs, and enhancing agricultural market infrastructure. By addressing these areas, policymakers can create an enabling environment that supports smallholder farmers in transitioning to modern marketing channels, thereby promoting inclusive economic growth and improving livelihoods in rural communities.

5. Summary and conclusions

In summary, the choice of marketing channels is of paramount importance for smallholder dry chilli farmers in India, impacting their income, stability, and overall well-being. Different channels offer varying price points and profit margins, with direct access channels like retail malls and e-markets often yielding higher prices due to reduced intermediary involvement. In Andhra Pradesh, dry chilli marketing encompasses traditional channels such as APMCs and modern avenues like business linkages with retail malls and e-markets. Each channel has its benefits and challenges, and farmers may opt them based on their specific circumstances and market preferences. The study’s objective is to explore impact of participation in modern marketing channels on GEW for smallholder dry chilli farmers.

The study delves into the intricate dynamics of agricultural marketing channels, specifically focusing on traditional avenues, APMC markets, and modern options like retail malls and the Kalgudi e-market platform. The sample farmers were selected based on probability proportion to size approach to ensure a diverse and representative sample across various marketing channels. This approach aimed to capture the nuanced differences and variations within these channels, providing a comprehensive understanding of their impact. The MNL model highlighted key determinants viz., access to extension services, education, technical support from entities like ANGRAU, Department of Agriculture, retail malls, and e-market; access to market information, membership in FPOs etc., and they exerted positive influence on market participation in modern channels (retail malls and e-markets). The second stage of MESRM these variables consistently showed positive impacts on farmer’s GEW across different marketing channels. The ATT results showed that adoption of modern channels led to substantial income gains: R0K1 participants experienced a 46.77 per cent increase, R1K0 participants saw a 39.08 per cent increase, and R1K1 participants enjoyed a 41.09 per cent increase in GEW compared to non-participants. Additionally, ATU analyses reveal that even if participants in modern marketing channels hadn’t adopted these avenues, they would realize lower income levels than they do currently. This study’s compelling evidence underscores the pivotal role of modern marketing channels in elevating smallholder farmers’ GEW. This positive impact can be attributed to several interconnected factors. Enhanced market access allows farmers to tap into larger consumer bases, while reduced intermediation ensures they retain a larger share of their profits. Improved price realization and increased bargaining power in these channels contribute to higher income levels for participants.

The findings of this study hold several practical implications for smallholder farmers, government entities, and agricultural institutions. For smallholder farmers, understanding the determinants of success in modern marketing channels can guide their strategic decisions and investments. By prioritizing access to extension services, education, and technical support, farmers can enhance their capacity to navigate digital platforms and hybrid marketing models effectively. Moreover, leveraging market information and internet access can help them tailor their products to meet consumer demands, thereby maximizing their profitability. For government entities, the study underscores the importance of investing in rural infrastructure, particularly digital connectivity and market facilities. By improving access to internet services and enhancing market infrastructure, governments can create an enabling environment for smallholder farmers to participate in modern marketing channels. Additionally, policymakers can support the formation and strengthening of FPOs to empower farmers through collective bargaining and market linkages. Agricultural institutions can play a pivotal role in facilitating capacity-building initiatives and knowledge-sharing platforms to equip farmers with the skills and resources needed to thrive in modern agricultural markets. Furthermore, the broader implications for the agricultural sector and sustainable development are significant. By promoting the adoption of modern marketing channels, stakeholders can enhance market efficiency, reduce post-harvest losses, and improve income distribution along the agricultural value chain. This, in turn, contributes to poverty reduction, food security, and rural development, aligning with broader sustainable development goals. Additionally, by promoting inclusive and sustainable agricultural practices, such as digitalization and collective action through FPOs, stakeholders can advance environmentally friendly and socially responsible agricultural development, fostering long-term sustainability and resilience in the sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

K. Nirmal Ravi Kumar

Dr. K. Nirmal Ravi Kumar holding Master’s and Ph.D. degrees in Agricultural Economics, has studied at Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University (ANGRAU). He has a brilliant academic career with specialization in ‘Agricultural Marketing’ both in his post-graduate and doctoral programmes. Dr. Kumar is currently Professor & Head (Agril. Economics) in Agricultural College, Bapatla. He is actively involved both in agricultural research and teaching activities during the past twenty-two years in the ANGRAU. He also worked as Director (Agricultural Marketing) in National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE), Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India. He was the recipient of ‘Sri Mocherla Dattatreyulu Gold Medal’ (2013) and ‘State Best Teacher Award’ (2016). Dr. Kumar has written extensively and has to his credit 10 books, and six (6) published articles in reputable journal of higher impact.

Adinan Bahahudeen Shafiwu

Adinan Bahahudeen Shafiwu, is currently a J-Pal African Scholar who has just finished his project on Digitalization of Cocoa Value Chain in Ghana under the DigiFi initiatives. He has worked and participated in J-pal initiatives that involves Randomized Control Trial. As part of his training under J-Pal he participated in both DIWA and Development Methodologies workshops here in Ghana and Morocco-Rabat respectively. He holds a PhD and MPhil in (Agricultural Economics) and also a chartered Health Economics certificates and currently works with the University for Development Studies in the capacity as a lecturer. He is an expert in Adoption Studies, efficiency, welfare and consumption studies. He is into modeling and has deep seated knowledge in econometrics and its models. A good data manager. He has also consulted for Plan International Ghana and Oxfarm on both midline and Baseline survey. He has published over twenty (20) research articles in reputable journals with higher impact. He is Highly regarded for his good leadership, communication, proposal writing, research, and analytical skills. Able to establish, implement and monitor systems for effectiveness and efficiency at organizations.

Y. Prabhavathi

Y. Prabhavathi, currently working as Assistant Professor at Institute of Agribusiness Management (IABM), Acharya N G Ranga Agricultural University (ANGRAU). Her areas of specializations include including agribusiness management, agricultural marketing, analysis of agri value chains, models for rural collectivization among farmers, business modeling in agriculture, entrepreneurship and innovation in the agricultural sector, as well as incubation and assessing business performance. She is a recipient of university level gold medals for her academic performance and has received numerous awards, including the prestigious NABARD Citation for Outstanding Doctoral Thesis. Till date she had authored more than 30 research articles in various national international peer reviewed journals, guided around 20 post graduate students specializing in agribusiness management, developed two training manuals aimed at fostering entrepreneurship skills within the agribusiness and food sectors as well as by authoring two book chapters. She is also serving as a resource person in mentoring agricultural startups in incubation centres and national level entrepreneurship training programmes.

References

- Adinan, B. S., Samuel, A. D., & Abdul-Malik A. (2022). The welfare impact of improved seed variety adoption in Ghana. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 10, 100347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100347

- Alhassane, C., Anatole, G., Christian, H., Luc, S., & Assane B. (2021). Joint market participation choices of smallholder farmers and households’ welfare: Evidence from Senegal. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 13(4), 537–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-08-2021-0201

- Asfaw, S. (2018). Market Participation, Weather Shocks and Welfare: Evidence from Malawi. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/iaae18/277029.html

- Asfaw, S., Lipper, L., Dalton, T. J., & Audi, P. (2012). Market participation, on-farm crop diversity and household welfare: micro-evidence from Kenya. Environment and Development Economics, 17(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X12000277

- Bourguignon, F., Fournier, M., & Gurgand, M. (2007). Selection bias corrections based on the multinomial logit model: Monte Carlo comparisons. Journal of Economic Surveys, 21(1), 174–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00503.x

- Burke, W. J., Myers, R. J., & Jayne, T. S. (2015). A triple-Hurdle model of production and market participation in Kenya’s dairy market. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 97(4), 1227–1246. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aav009

- Camara, A. (2017). Market participation of smallholders and the role of the upstream segment: evidence from Guinea. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, available at: https://mpra.ub.unimuenchen.de/id/eprint/78903

- Chamberlain, G., & Griliches, Z. (1975). Unobservables with a variance-components structure: Ability, schooling and the economic success of brothers. International Economic Review, 16(2), 422–449. https://doi.org/10.2307/2525824

- Danso Abbeam, G., & Baiyegunhi, L. J. S. (2018). Welfare impact of pesticides management practices among smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana. Technology in Society, 54, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.01.011

- Danso Abbeam, G., Bosiako, J. A., Ehiakpor, D. S., & Mabe, F. N. (2017). Adoption of improved maize variety among farm households in the northern region of Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 5(1), 1416896. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2017.1416896

- Deb, P., & Trivedi, P. K. (2006a). Specification and simulated likelihood estimation of a non-normal treatment-outcome with selection: application to health care utilization. The Econometrics Journal, 9(2), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423X.2006.00187.x

- Deb, P., & Trivedi, P. K. (2006b). Maximum simulated likelihood estimation of a negative binomial regression model with multinomial endogenous treatment. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 6(2), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0600600206

- Di Falco, S., & Veronesi, M. (2013). How can African agriculture adapt to climate change? A counterfactual analysis from Ethiopia. Land Economics, 89(4), 743–766. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24243700. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.89.4.743

- Di Falco, S., Veronesi, M., & Yesuf, M. (2011). Does adaptation to climate change provide food security? A micro-perspective from Ethiopia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93(3), 829–846. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aar006

- Dubin, J. A., & McFadden, D. L. (1984). An econometric analysis of residential electric appliance holdings and consumption. Econometrica, 52(2), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.2307/1911493

- Enete, A. A., & Igbokwe, E. M. (2009). Cassava market participation decision of producing households in Africa. Tropicultura, 27(3), 129–136.

- Essilfie, F. L. (2018). Varietal seed technology and household income of maize farmers: an application of the doubly robust model. Technology in Society, 55, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.07.002

- Georges, N., Fang, S., Beckline, M., & Wu, Y. (2016). Potentials of the groundnut sector towards achieving food security in Senegal. OALib, 03(09), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1102991

- Gyau, A., Mbugua, M., & Oduol, J. (2016). Determinants of participation and intensity of participation in collective action: evidence from smallholder avocado farmers in Kenya. Journal on Chain and Network Science, 16(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.3920/JCNS2015.0011

- Habwe, F. O., Walingo, K. M., & Onyango, M. A. (2008). Food processing and preparation technologies for sustainable utilization of African indigenous vegetables for nutrition security and wealth creation in Kenya. Chapter 13 from Using Food Science and Technology to Improve Nutrition and Promote National Development, Robertson, G.L. & Lupien, J.R. (Eds), © International Union of Food Science & Technology.

- Hoken, H., & Su, Q. (2018). Measuring the effect of agricultural cooperatives on household income: case study of a rice-producing cooperative in China. Agribusiness, 34(4), 831–846. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21554

- Jagwe, J., Ouma, E., & Machethe, C. (2010). Impact of transaction cost on the participation of smallholder farmers and intermediaries in the Banana Market in Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. African Journal on Agricultural and Resource Economics, 6(1), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.156668

- Jari, B. (2009). Institutional and technical factors influencing agricultural marketing channel choices amongst smallholder and emerging farmers in the Kat River Valley. Unpublished Master of Science in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics), Faculty of Science and Agriculture University of Fort Hare, South Africa.

- Kabunga, N. S., Dubois, T., & Qaim, M. (2012). Heterogeneous information exposure and technology adoption: the case of tissue culture bananas in Kenya. Agricultural Economics, 43(5), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2012.00597.x

- Kassie, M., Teklewold, H., Marenya, P., Jaleta, M., & Erenstein, O. (2015). Production risks and food security under alternative technology choices in Malawi: application of a multinomial endogenous switching regression. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 66(3), 640–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12099

- Khanal, A., Ashok Mishra, K. J. M., & Hirsch, S. (2020). Choice of contract farming strategies, productivity, and profits: evidence from high-value crop production. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 45(3), 589–604. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.303604

- Khonje, M. G., Manda, J., Mkandawire, P., Tufa, A. H., & Alene, A. D. (2018). Adoption and welfare impacts of multiple agricultural technologies: Evidence from eastern Zambia. Agricultural Economics, 49(5), 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12445

- Khonje, M., Manda, J., Alene, A. D., & Kassie, M. (2015). Analysis of adoption and impacts of improved maize varieties in eastern Zambia. World Development, 66, 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.008

- Kumar, A., Mishra, A., Saroj, S., & Joshi, P. K. (2019). Impact of traditional versus modern dairy value chains on food security: evidence from India’s dairy sector. Food Policy. 83, 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.01.010

- Layne, N. (2016). Sam’s club hires regional buyers, see ‘local’ food as key in upscale shift. Reuters Business. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-walmart-buying-idUSKCN0W34EE

- Li, J., Ma, W., Renwick, A., & Zheng, H. (2020). The impact of access to irrigation on rural incomes and diversification: evidence from China. China Agricultural Economic Review, 12(4), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-09-2019-0172

- Liu, M., Min, S., Ma, W., & Liu, T. (2021). The adoption and impact of E-commerce in rural China: application of an endogenous switching regression model. Journal of Rural Studies, 83, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.02.021

- Low, S. A., Adalja, A., Beaulieu, E., Key, N., Martinez, S., Melton, A., Perez, A., Ralston, K., Stewart, H., Suttles, S., Vogel, S., & Jablonski, B. B. R. (2015). Trends in U.S. local and regional food systems: A report to Congress. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/42805/51173_ap068.pdf

- Lu, W., Addai, K. N., & Ng’ombe, J. N. (2021). Impact of improved rice varieties on household food security in Northern Ghana: A doubly robust analysis. Journal of International Development, 33(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3525

- Ma, W., & Abdulai, A. (2017). The economic impacts of agricultural cooperatives on smallholder farmers in rural China. Agribusiness, 33(4), 537–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21522

- Ma, W., Zhu, Z., & Zhou, X. (2022). Agricultural mechanization and cropland abandonment in rural China. Applied Economics Letters, 29(6), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2021.1875113

- Mabuza, M. L., Ortmann, G., & Wale, E. (2014). Effects of transaction costs on mushroom producers’ choice of marketing channels: implications for access to agricultural markets in Swaziland. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 17(2), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v17i2.494

- Manda, J., Carlo, A., Shiferaw, F., Bekele, K., Lieven, C., & Mateete, B. (2021). Welfare impacts of smallholder farmers’ participation in multiple output markets: empirical evidence from Tanzania. PloS One, 16(5), e0250848. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250848

- Marenya, P. P., & Barrett, C. B. (2007). Household level determinants of adoption of improved natural resources management practices among smallholder farmers in Western Kenya. Food Policy. 32(4), 515–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.10.002

- Mathenge, M. K., Smale, M., & Olwande, J. (2014). The impacts of hybrid maize seed on the welfare of farming households in Kenya. Food Policy. 44, 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.09.013

- Matson, J., Sullins, M., & Cook, C. (2013). The role of food hubs in local food marketing. Journal of Agriculture Food Systems and Community Development, 3(4), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2013.034.004

- McFadden, D. (1973). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice be. In Zarembka P (ed.). Frontiers in Econometrics. Academic Press. 105–142.

- Michelson, H. C. (2013). Small farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart world: Welfare effects of supermarkets operating in Nicaragua. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 95(3), 628–649. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1093/ https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas139