?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examined purchasing outlets, consumer satisfaction, preferences for enhanced chicken egg attributes in Ghana, and the determining factors. Notwithstanding the several studies on the pattern, preferences and consumption of eggs, studies on preferences of chicken eggs in Ghana are very limited. Thus, this study extends the theory of reasoned action by integrating the attribute construct of means-end theory to analyze consumers’ preferences for enhanced attributes of chicken eggs (by focusing on demographics, attitudes, subjective norms and attributes). Using the closed-ended contingent valuation method, primary data was compiled from 200 chicken egg consumers. Likert scale, truncated and ordered probit regressions were applied. Retailers, farmers and food vendors are major purchase outlets for chicken eggs. Consumers were unsatisfied with chicken egg price, neatness, hygiene of vending surroundings, size and customer care. Nonetheless, they were satisfied with eggshell hardness, absence of cracks, packaging, consistency in supply, and certification by authorities. Most consumers were willing to pay higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Willingness to pay (WTP) ranged from 10–80% increase in market price, with an average of 33%. Demographic, attitudinal and subjective-norm characteristics, and satisfaction with chicken egg attributes influence WTP. Low satisfaction with specific chicken egg attributes and high WTP suggest a good market potential for enhanced chicken egg attributes.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The egg is widely regarded as one of the most important and widely consumed staple foods in the world, and it is high in protein (Lesnierowski & Stangierski, Citation2018). Eggs have antioxidant properties, including carotenoids, vitamin E, vitamin A, selenium, and iodine (Nimalaratne & Wu, Citation2015). Although egg provide numerous nutritional and health benefits, its consumption is limited (Ayim-Akonor & Akonor, Citation2014). Given the situation, several institutions and health-related organizations have devised strategies to increase egg intake. For instance, world egg day (globally), Lulun project (Ecuador), Gallegos-Riofrío et al. (Citation2018), UNICEF (Indonesia), de Pee et al. (Citation1998), and nutrition links (Ghana) programmes (Marquis et al., Citation2017) were initiated to promote the consumption of eggs. Thus, the intake of eggs has increased globally and is expected to rise further (Żakowska-Biemans & Tekień, Citation2017).

Consumers nowadays are well-informed about the various varieties of eggs and their nutritional differences. For this reason, consumers are concerned with the production systems, which have become essential factors in their purchasing decision (de Graaf et al., Citation2016; Mesías et al., Citation2011). According to Żakowska-Biemans and Tekień (Citation2017), consumers prefer organic and free-range eggs on account that organic eggs are safe, healthy, natural, tasty, animal-friendly, and of high quality (Mesías et al., Citation2011). For example, 65% of Polish consumers report purchasing organic eggs. Similar findings are seen in Africa, Central and Eastern European countries like Romania and the Czech Republic (Ayim-Akonor & Akonor, Citation2014; Lee & Yun, Citation2015; Lordelo et al., Citation2017; Żakowska-Biemans & Tekień, Citation2017). Consumers prefer organic to conventional eggs due to their higher nutritional content than conventional eggs (Xia et al., Citation2022). This preference is due to growing awareness of the health risks associated with food consumption (Changhee & Chanjin, Citation2011). Today’s consumers want an ever-widening variety of food products with various nutrition, convenience, food safety and environmental characteristics.

As consumer preferences shift, food markets segment into specific niche micro-markets, and single-product markets are gradually being replaced by highly differentiated product markets (Karipidis et al., Citation2005). For example, the egg market in Canada has evolved from an undifferentiated market to a differentiated market. Due to assurance of safety, some customers could purchase food products including eggs from supermarkets. According to Slack and Singh (Citation2020), service quality of supermarkets significantly affects customer satisfaction and loyalty and customer satisfaction partially mediates the relationship between service quality and customer loyalty. Also, Slack et al. (Citation2020) reported that customer satisfaction significantly affects customer loyalty, and customer repurchase intention.

The population of egg consumers is of different segments exhibiting different purchase attributes, demographics and demand for egg types (Bejaei et al., Citation2011). Thus, it is critical for producers of the egg market to better understand consumer preferences. Based on such knowledge, producers of eggs can develop effective marketing plans (Żakowska-Biemans & Tekień, Citation2017), better align their products with consumer preferences (Karipidis et al., Citation2005) gain a competitive advantage (Morales & Higuchi, Citation2018; Żakowska-Biemans & Tekień, Citation2017) and ultimately increase their income. Consequently, to assist producers of eggs to tailor to the needs of consumers and increase the farmers’ income, some studies have examined consumers’ preference for eggs. For example, Ayim-Akonor and Akonor (Citation2014); Mesías et al. (Citation2011); Żakowska-Biemans and Tekień (Citation2017) studied consumer preferences for eggs. Whiles Rondoni et al. (Citation2020) examined the consumer behaviour and perception of eggs. Furthermore, Lee and Yun (Citation2015); Fabbrizzi et al. (Citation2017); Min et al. (Citation2012) assessed the determinants of purchase intentions toward food.

Notwithstanding the several studies conducted to understand the pattern, preferences and consumption of eggs, it is evident that studies on the preferences of eggs in Ghana are very limited (Ayim-Akonor & Akonor, Citation2014; Rondoni et al., Citation2020). Also, different from earlier studies on consumer preferences for eggs, in this study, the authors extend the theory of reasoned action (TRA) by integrating the attribute construct of means-end theory (MET) to analyze the relationship between these constructs and purchase intention or willingness to pay (WTP) for higher prices for enhanced attributes of chicken eggs between its construct (demographics, attitudes, subjective norms and attributes) and/or WTP. The attitudinal characteristics considered in exploring consumers’ preferences for enhanced attributes of chicken eggs are income, food expenditure, and quantity of eggs consumed. Also, the subjective norm characteristics considered are egg purchase outlet, trust in authorities, residence status, type of employment, hygiene of surrounding, and customer care. Furthermore, consumers’ satisfaction with the neatness of egg shell, size of an egg, shell quality/hardness, and packaging were integrated in assessing consumers’ preferences for enhanced attributes of chicken eggs. Thus, whiles TRA has been used in a plethora of research on consumer studies (Islam & Hussain, Citation2022; Jang & Cho, Citation2022; Saleem et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2022), no study has adopted the extended TRA to assess consumer WTP for enhanced chicken egg attributes in Ghana. Therefore, this study adds to the scarce literature on consumer satisfaction and WTP for enhanced chicken egg attributes in Ghana. Knowledge of these can help poultry farmers and chicken egg retailers to gain and retain consumers, satisfy them and increase their income.

This study investigates the choice of purchase outlets, consumer satisfaction and WTP for enhanced chicken egg attributes in Ghana. The specific objectives are as follows. (1) To investigate the choice of purchase outlets by consumers of chicken eggs in Ghana. (2) To determine consumers’ satisfaction with the qualities/attributes of chicken eggs. (3) To assess consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes, and the determining factors.

2. Literature review

Shah et al. (Citation2012) define purchase intention as a situation where a customer purchases a specific product under certain conditions. Slack et al. (Citation2023) reported that tested customer perceived value dimensions, animal welfare and source credibility are positive stimuli of consumer attitude towards purchasing free-range eggs, which subsequently promotes consumer WTP for free-range eggs. Purchase intent is generally related to the customers’ behaviour, perceptions and attitudes. Identifying the factors that influence purchase intention will allow managers to develop corporate strategies to improve the purchasing intentions, ultimately improving the company’s profits. On this basis, we examined several studies on the factors that influence consumers’ purchase intentions.

2.1. Demographics

According to Imelia and Ruswanti (Citation2017), demographic factors such as age and sex influence consumer purchase intentions. Likewise, Situmorang et al. (Citation2022), revealed that sex and gender (female consumers) have a significant relationship with purchase intention. However, Bannor et al. (Citation2020) indicated that household characteristics, family size does not have a significant relationship with purchase intention.

2.2. Attribute

The reviewed literature itemized several product attributes influencing the purchase intention of consumers. Kim et al. (Citation2013), in their study of analyzing factors influencing purchasing behaviour towards eggs, found that product attributes – neatness of the egg, packaging and size of the egg influence the purchasing decision of consumers. Kralik et al. (Citation2020) also reported similar findings that the size of the egg, the neatness of the egg and the eggshell quality had a significant impact on the consumer purchase decision. In addition, Ampuero and Vila (Citation2006) ascribed that packaging is an essential factor in decision-making, and consumers typically examine products by looking at the package. Bannor et al. (Citation2020) concluded a significant relationship between product attributes and consumers’ purchase intention.

2.3. Attitude

Consumers’ attitude is an important factor in influencing consumers’ purchase intention (Chaniotakis et al., Citation2010). According to Hyun et al. (Citation2010), income positively influences consumers’ purchase intention and willingness to pay higher prices for free-range eggs Another study by Bett et al. (Citation2013) frequency of consumption positively influences consumers’ willingness to pay. More so, the environment’s hygiene significantly influences purchase intention (Shim et al., Citation2021). Similarly, Liu and Niyongira (Citation2017) found that a hygienic environment is critical in determining purchase intention.

2.4. Subjective norm

Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation2005) explains subjective norm as “the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behaviour.” Subjective norm is usually defined as an individual’s perception or opinion about what essential others believe the individual should do. Imelia and Ruswanti (Citation2017) investigated the relationship between subjective norms toward purchase intention and discovered that subjective norms impact purchase intention. According to Situmorang et al. (Citation2022), purchase outlet influences the intention to purchase.

3. Extended theory of reasoned action (TRA) and means-end theory (MET)

Jang and Cho (Citation2022) used the TRA to assess the association between ugly food value and consumers’ behavioural intentions while Zhu et al. (Citation2022) applied the TRA to examine consumers’ intention to participate in food safety risk communication. According to Singh et al. (Citation2023), attitude, subjective norms, scarcity, time pressure and perceived competition directly affect customers’ panic buying intention.

Several theories, like social identity theory, TRA, motivation need theory, MET, behavioural reasoning theory, and theory of planned behaviour, among others, have been proposed and used to understand and predict consumer behaviour in several studies (Aitken et al., Citation2020; Bannor, Oppong-Kyeremeh, & Kuwornu, Citation2021; Bannor & Abele, Citation2021; Procter et al., Citation2019; Ryan & Casidy, Citation2018). For instance, the MET suggests that consumers yearn for service or product attributes because of the benefits or otherwise those attributes offer (Min et al., Citation2012; Olson & Reynolds, Citation2001), which meets consumer value (Borgardt, Citation2020; Gutman, Citation1982). Accordingly, the purchase intention for enhanced chicken egg attributes in Ghana is influenced by the interviewed consumers’ desire for specific attributes, given that they achieve the desired consequence (the benefits or liabilities the consumer will derive from the product) and value (traits or characteristics the consumer wants to be known for) of the consumer (Fabbrizzi et al., Citation2017; Min et al., Citation2012; Woodruff & Gardial, Citation1996).

TRA, like MET, suggests that consumer purchase intention is the precursor of the consumer’s actual purchase (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). Thus, TRA is made up of the attitudes/beliefs about the consequences of an act and subjective norm, which is influenced by social networks, cultural norms, group beliefs and others’ thinking (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Kumar & Smith, Citation2018). The challenge with the TRA is that it does not consider actions done by coercion or force other than voluntary (Ajzen, Citation1991; Conner & Armitage, Citation2006). Notwithstanding, the TRA has been used in several consumer studies (Ackermann & Palmer, Citation2014; Jang & Cho, Citation2022; Petrovici et al., Citation2004).

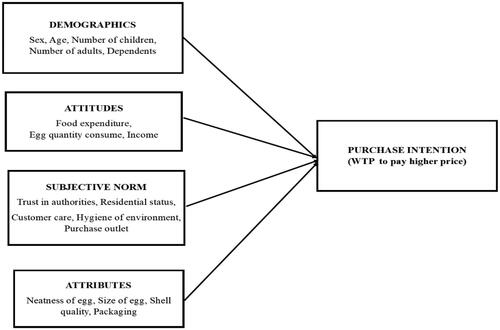

In this study, drawing from MET, the authors picked the attribute construct of the same and added it to the constructs of TRA to model consumers’ intention to purchase enhanced chicken egg attributes (neatness and size of the egg) and non-product (packaging) related attributes. Thus, we extend the TRA by integrating the attribute construct of MET. Accordingly, the authors propose an extended theory (extended theory of reasoned action [ETRA]) where attributes of the eggs (neatness, size, shell quality and packaging), the attitude of the consumer (food expenditure, income and egg quantity consumed) plus the subjective norm (trust in authorities, residential status, customer care, hygiene of environment and purchasing outlet) to model consumer WTP. Essentially, the ETRA was used to model the WTP for enhanced chicken eggs at a higher price (intention) and the actual purchasing subsequently. Conceptually, presents the operationalization of the theory used in this study.

4. Methodology

4.1. Study setting and data

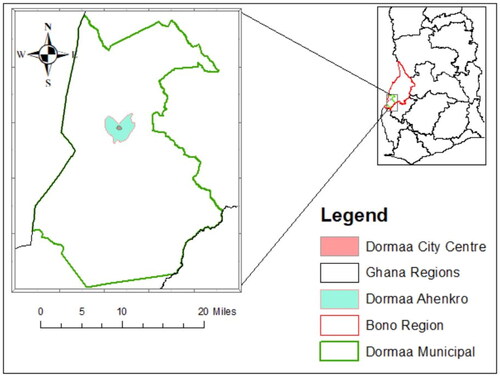

The study was conducted in Dormaa Central Municipal in the Bono Region of Ghana (). This is because chicken production is a dominant economic activity in the municipal. Simple random sampling was employed to compile primary data from 200 chicken egg consumers. The names of towns under the municipal were obtained from the Municipal Assembly. From the list, four towns were randomly sampled for the study. The random number chart was used in order to ensure the randomness of the selection. From each town, 25 consumers were randomly selected. This is because almost every household in the municipal is a consumer of chicken egg. Thus, all consumers had equal chances of being selected for the interview. The sample size is limited because the study did not receive any external funding. A semi-structured questionnaire was administered to collect primary data through a personal (face-to-face interaction with the respondents) interview. Research assistants and extension officers who understood the local dialect of the study area were trained on the questionnaire to assist in the data collection. Data was collected in October, 2021. give geographical details of where the data was collected.

4.2. WTP elicitation and analytical framework

The contingent valuation method (CVM) was employed in eliciting the maximum amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Likert scale was used to determine consumers’ satisfaction with qualities/attributes of chicken eggs. Ordered probit and truncated regressions were estimated to investigate the factors influencing consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes.

4.2.1. CVM For WTP elicitation

CVM is widely used for valuing a non-market product (Hanemann et al., Citation1991). CVM enables consumers to indicate their WTP without actually purchasing a hypothetical product. This study elicited consumers’ WTP by asking the prices they are prepared to accept for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes by creating a hypothetical market. Before the data collection, the price of one crate of chicken egg in the study area was obtained from vendors and producers. It was discovered that the average market price of one crate of chicken egg during the data collection (October, 2021) in the study area was US$2.40. This was used as a start-up price for eliciting consumers’ WTP for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Due to the additional cost involved in producing and supplying chicken eggs with enhanced attributes to consumers, a 10% increase in the market price of chicken eggs was the minimum WTP amount. During the data collection, WTP was elicited by increasing the 10% premium price at intervals of 10 up to 100% (). shows the current market price for one crate of chicken egg (US$), the percentage (%) increase in the market price for WTP elicitation, and actual WTP amounts for one crate of egg (US$).

Table 1. Bids for WTP elicitation.

The enumerators carefully explained the nature, positive health implications and other qualities associated with the consumption of the hypothetical product (chicken eggs with enhanced attributes) to respondents relative to existing chicken eggs. Based on this, the respondents indicated the amount they would be willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes such as neat and sizeable chicken eggs, eggs sold under hygienic conditions and good customer care, eggs with upgraded packaging and harder shells, absence of cracks on shells, and eggs from credible poultry farms/sources certified by appropriate authorities.

Closed-ended CVM was used. This is because it offers respondents ample information on a new product, allowing them to make realistic estimates (Hanemann et al., Citation1991). In this case, consumers were first asked to indicate whether they were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Secondly, those willing to pay were further asked to indicate the maximum amount they were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes based on the WTP bids in .

4.2.2. Ordered probit regression model

The CVM used for the elicitation consumers’ WTP for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes led to a response variable measured on an ordinal scale. Thus, ordered probit, which is an ordered choice model, was suitable. Percentage (%) increase in the market price of one crate of chicken eggs and the corresponding amounts (US$) consumers were willing to pay were grouped into four ordered responses (). The classes used to create the categorical variable were formed based on the level of WTP: no WTP, low WTP, moderate WTP, and premium/high WTP.

Table 2. Categories of responses from the CVM for WTP elicitation.

The categories/groups in were used as the response/dependent variable in the ordered probit regression to investigate the factors influencing WTP amounts for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Marginal effects were computed for these WTP bids (). The independent variables and their measurements used for the estimation of the ordered probit model are presented in . According to StataCorp (Citation2015), there is a continuous latent utility ():

(1)

(1)

where

is unobserved. What is really observed is a discrete variable, y acquired via a censoring procedure, each of which relates to one of the four responses in .

(2)

(2)

where

represents WTP (maximum amount respondent

is willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes); the c’s represent threshold parameters for the censoring (Maddala, Citation1983). The latent variable relates to an unobserved utility consumers obtain from choosing a particular WTP bid. The model of interest relates to the one which corresponds to the probability of WTP conditional on consumers’ characteristics:

(3)

(3)

There are threshold values which enable consumers to make the transition from one WTP bid to the other (StataCorp, Citation2015). Given the threshold value (c), the ordered probability function is given below (StataCorp, Citation2015):

(4)

(4)

where

= probability,

= decision of the

consumer to pay a bid

,

= outcomes of alternative bids,

= cut-points,

= characteristics of consumers i, b is the coefficient to be estimated, and

= error term.

4.2.3. Truncated regression model

After the data collection, it was observed that 17% of the consumers were unwilling to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. This led to zero observations in the WTP elicitation. Therefore, truncated regression was appropriate (Greene, Citation2012; StataCorp, Citation2015). It was further estimated to investigate the factors influencing the maximum amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The estimates from the truncated and ordered probit regression models were compared. According to StataCorp (Citation2015); Greene (Citation2012), the truncated regression model is expressed as follows:

(5)

(5)

where

is a continuous response variable; that is, the maximum amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes.

Following StataCorp (Citation2015); Greene (Citation2012), let

be the lower limit and

be the upper limit. The log-likelihood is expressed as:

(6)

(6)

where

is the distribution function of the standard normal distribution (Greene, Citation2012).

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Characteristics of consumers

presents the background information of consumers sampled for the study. The test-statistics shows statistically significant differences in characteristics between consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes and those unwilling to pay. More male consumers were willing to pay than females. The average age of consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes was higher than those who were unwilling to pay. A greater proportion of consumers who were willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes were non-natives. On average, a household constitutes four members. Also, on average, a household in the study area was made up of one person below 12 years (children), three people aged between 18–60 (adults), and one person above 60 years (aged). This implies that households in the study area constituted more adults than children and aged. The average number of dependents was higher for consumers unwilling to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes than those willing to pay.

Table 3. Characteristics of consumers.

further shows that, on average, a consumer had attained ten years of formal education. However, the minimum shows that some had no formal education, while the maximum shows that others have 18 years of formal education. Consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes had higher years of formal education than their counterparts who were unwilling to pay. The average monthly household food expenditure was US$190. This was higher for consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes (US$193) than those unwilling to pay (US$182). Most consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes had formal employment. Furthermore, the average monthly household income was US$365. Consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes recorded higher monthly income (US$379) than those unwilling to pay (US$295).

5.2. Choice of purchase outlets by consumers of chicken eggs

presents the choice of purchase outlets by consumers of chicken eggs. The table shows frequency of egg consumption, number of eggs consumed by a household in a week, trust in authorities that certify egg production, and egg purchase outlets. The test-statistics show statistically significant differences in these variables between consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes and those unwilling to pay. The majority of the respondents consume eggs daily (25%), twice a week (25%), or thrice a week (33%). This suggests fairly frequent consumption of chicken egg in the study area. This is good considering the health benefits of chicken egg consumption. Chicken production and marketing a predominant economic activities in the Bono Region of Ghana, which formed the study area. This makes chicken egg available and cheaper compared with other districts/regions of Ghana. The table shows that consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes consumed eggs more frequently than those unwilling to pay.

Table 4. Choice of purchase outlets by consumers of chicken eggs.

further reveals that, on average, a household in the study area consumes 15 eggs a week. Consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes consumed more eggs per week (18) than those unwilling to pay (15). More than half of the consumers interviewed for the study trust authorities in charge of certification and production of quality/healthy chicken eggs in Ghana. These authorities include the Food and Drugs Authority (FDA), veterinary officers and District/Municipal Assemblies. These agencies/authorities register poultry producers and certify that their products (such as chicken and eggs) are safe and healthy for human consumption. Consumers willing to pay more for enhanced chicken egg attributes exhibited higher trust in certification authorities than those unwilling to pay.

Furthermore, half of the consumers purchase chicken eggs from retailers (). Retailers of chicken eggs are rifer in towns/cities than other purchase outlets such as farmers and wholesalers. About 40% of the consumers purchase chicken eggs from poultry farmers. Due to the prevalence of poultry farms in the study area, many consumers are likely to reside closer to production centres. This proximity increases the probability of purchasing chicken eggs directly from producers. Such consumers purchase chicken eggs at relatively low/reduced prices compared with those who purchase from other outlets such as wholesalers, retailers and food vendors. However, few consumers purchase chicken eggs from food vendors (8%) and wholesalers (3%). Consumers who purchase chicken eggs from food vendors purchase cooked foods. Also, consumers who buy from wholesalers could be those who buy chicken eggs in bulk. Such consumers purchase chicken eggs at reduced prices than those who purchase from other outlets such as retailers and food vendors.

5.3. Consumers’ satisfaction with qualities/attributes of chicken eggs

presents consumers’ satisfaction with the qualities/attributes of chicken eggs. Qualities/attributes considered for the study are price, neatness, hygiene of vending surrounding, size, shell quality/hardness, absence of cracks on shells, packaging, consistency in supply, customer care, and certification by authorities. Most consumers (77%) had lower satisfaction with the price of chicken eggs. Such consumers deemed the market price of chicken eggs to be too high. The high prices could be attributed to rising input prices which raises the cost of production. However, few (6%) showed high satisfaction with the price of chicken eggs. Half of the consumers were unsatisfied with the neatness of the chicken eggs sold. Eggs are sometimes soiled with chicken droppings, litter and other debris in the poultry house. Some traders do not do enough cleaning of eggs before sale. However, one-fifth showed high satisfaction with the neatness of chicken eggs. More than half (56%) of the consumers had low satisfaction with the hygiene of the surrounding where chicken eggs are being traded. This indicates that in addition to the neatness of chicken eggs, consumers also consider the vending environment.

Table 5. Consumers’ satisfaction with qualities/attributes of chicken eggs.

Furthermore, 56% showed low satisfaction with the size of chicken eggs, while 35% showed high satisfaction (). This indicates that most consumers consider chicken eggs sold in the study area to be smaller in size. Also, 45% of the consumers were satisfied with the quality/hardness of chicken egg shells, while 30% were unsatisfied. Those unsatisfied expected the shells to be harder to reduce easy cracking. However, 90% revealed the absence of cracks on the chicken shells they purchased. More than half of the consumers were satisfied with the packaging of chicken eggs for sale, while about one-fifth were unsatisfied. In Ghana, chicken eggs are sold in paper crates. Such paper crates are less attractive and cannot prevent chicken eggs from cracking.

Almost all the respondents (90%) showed high satisfaction with consistency in the supply of chicken eggs in the study area (). This suggests that consumers in the study area have constant/regular access to chicken eggs. The study area (Bono Region) is highly known for chicken production in Ghana. This makes chicken eggs highly available in the study area. Close to 70% of the respondents were unsatisfied with customer care. Despite good attributes such as hygiene of vending environment, packaging, price and consistency in supply, products could be low sales due to bad customer care (Amfo & Ali, Citation2021). This makes good customer care pertinent in marketing. Also, 87% were highly satisfied with the level of certification by authorities. Some authorities (such as FDA, veterinary officers and district/municipal assemblies) to ensure the production of quality/healthy chicken eggs in Ghana. These authorities are supposed to certify poultry farms and farmers.

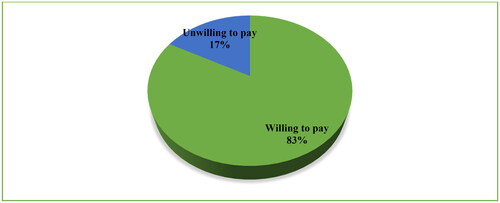

5.4. Consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes

displays consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The majority of the consumers interviewed for the study were willing to pay higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. This suggests that most of the consumers were unsatisfied with the attributes of chicken eggs being sold in the study area and would, therefore, appreciate enhancements in attributes. Such consumers were willing to pay premium prices for neat and sizeable chicken eggs, eggs sold under hygienic conditions and good customer care, eggs with upgraded packaging and harder shells, absence of cracks on shells, and eggs from credible poultry farms/sources certified by appropriate authorities. Nonetheless, less than one-fifth of the consumers were unwilling to pay for enhanced-quality chicken eggs. Such consumers were satisfied with attributes of chicken eggs being sold in the study area or were financially constrained and thus, could not afford to pay higher prices.

further encapsulates the amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The market price for one crate of chicken egg during the data collection (October, 2021) in the study area was US$2.40. This was used as a start-up price for the WTP elicitation. Less than one-fifth of the consumers were unwilling to pay for enhanced-quality chicken eggs. None of the consumers was willing to pay less than 10% or more than 80% increase in the market price of chicken eggs when the attributes are enhanced. Thus, WTP for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes ranged from 10 to 80% increase in market price (that is US$2.64–US$4.32 per crate). This implies that the lowest percentage increase in market price consumers were willing to pay was 10% (that is US$2.64 per crate) and the highest was 80% (US$4.32 per crate). A substantial proportion of consumers were willing to pay a 20–40% increase in the market price of chicken eggs (that is, US$2.88–US$3.36 per crate).

Table 6. Amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes.

Moreover, shows WTP categories for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The WTP of slightly more than half of the consumers ranged from 30 to 40% increase in the market price of chicken eggs (that is US$3.12–US$3.36 per crate). Thus, they had moderate WTP for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Also, a little above one-fifth of the consumers were willing to pay a 10–20% increase in the market price of chicken eggs if attributes are enhanced (US$2.64–US$2.88 per crate). Thus, they had low WTP for chicken eggs with superior attributes. Also, about one-tenth of the consumers were willing to pay over 50% of the market price of chicken eggs if attributes are improved (above US$3.60 per crate). Hence, their WTP for chicken eggs with superior attributes was categorized as high/premium. However, 17% of the consumers had no WTP for chicken eggs with superior attributes. These highlights a high diversity in the amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes.

In summary, reveals that, on average, consumers were willing to pay a 33% increase in the market price of chicken eggs with enhanced attributes (US$3.18 per crate). The minimum-maximum continuum is 10–80% (US$2.64–US$4.32). Generally, Amfo and Ali (Citation2021); Hung and Verbeke (Citation2018); Wang et al. (Citation2018); Cobbinah et al. (Citation2018); Gangnat et al. (Citation2018); Alimi and Workneh (Citation2016); Carpenter (Citation2016) found that WTP for food safety was high. For instance, Amfo and Ali (Citation2021) reported that on average, consumers would pay a 59% increase in the market price of meat if it improved.

5.5. Factors influencing consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes

This subsection discusses estimates from truncated regression () and ordered probit () for the factors influencing consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The Wald chi-squared in the truncated regression and the log-likelihood ratio chi-squared in the ordered probit regression are both significant (at 1%). This suggests that the explanatory variables jointly influence the amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Moreover, the pseudo-R-squared in the ordered probit regression suggests that the explanatory variables contribute to 19% of changes in the amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The explanatory variables in the truncated and ordered probit regressions were categorized based on the constructs in the theoretical and conceptual frameworks for easy understanding and link with the theory. These constructs are demographic, attitudinal and subjective norm characteristics, as well as consumers’ level of satisfaction with attributes of chicken eggs.

Table 7. Truncated regression for factors influencing consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes.

Table 8. Ordered probit regression for factors influencing consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes.

The truncated and ordered probit regressions reveal that demographic characteristics, sex, education, number of children and aged in a household, and number of dependents significantly influence consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Sex has statistically significant (at 5%) and positive coefficients in the truncated and ordered probit regressions. This indicates that being a male raises the amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The marginal effects in the ordered probit estimation indicate that sex is significant and negative for no and low WTP bids but positive for moderate and premium WTP bids (). Being a male lessens the probability of unwillingness to pay by 7.9% and paying low WTP bids by 7.3%.

Nonetheless, being a male increases the probability of paying moderate and premium WTP amounts by 12.3% and 2.9%, respectively. Hence, female consumers are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or agree to pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Contrary, male consumers are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. In Africa, females are customarily/traditionally responsible for household food provision, purchase, cooking and choice (Amfo et al., Citation2019; Ben, Citation2015; Demont & Ndour, Citation2016; Kassali et al., Citation2010). Thus, females in low-income households commonly deploy a number of economizing strategies in food purchasing than males (Amfo et al., Citation2019). One of such economizing approaches could be purchasing and consuming food products with less value addition such as chicken eggs with unimproved attributes since they are less expensive than those with improved attributes.

The truncated and ordered probit regressions reveal that education has statistically significant (at 5%) and positive coefficients. This means that years of formal education increase the amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The marginal effects in the ordered probit regression show that education is significant and negative for no and low WTP bids but positive for moderate and premium WTP bids. As a consumer’s years of formal education increase by one year, the probability of unwillingness to pay and paying low WTP bids reduce by 0.9% each. However, as years of formal education increase by one year, the probability of paying moderate and premium WTP amounts increases by 1.5% and 0.4%, respectively. Thus, uneducated consumers are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or agree to pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. In contrast, educated consumers are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. Education enhances people’s cognitive ability and their capability to process information (Amfo & Ali, Citation2021). Education boosts consumers’ knowledge which is essential in understanding and appreciating the health benefits of consuming safe food products (Ansah & Tetteh, Citation2016). Therefore, education generally enhances the value people ascribe to a healthy life (Amfo et al., Citation2019). Consequently, it improves consumers’ knowledge of the health benefits of consuming quality chicken eggs, boosting the likelihood of paying higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes to safeguard their health. In line with this finding, Amfo and Ali (Citation2021); Amfo et al. (Citation2019); Hung et al. (Citation2016) observed that education influences consumers’ WTP for safe/quality food products.

Household size has the potential to determine food choices. Also, the composition of a household influences food safety concerns (Amfo & Ali, Citation2021; Kasteridis & Yen, Citation2012). Hence, in this study, the household composition was used in the model estimation in lieu of household size and the number of children, adults and aged in a household were used as a proxy. The truncated regression reveals that the number of children in a household is statistically significant (at 5%) and positively signed coefficient (). This indicates that the number of children in a household boosts the amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Thus, households with children are more likely to pay higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes than their counterparts without. Households with many children (members below 12 years) are likely to be more concerned with food safety and health issues (Roitner-Schobesberger et al., Citation2008; Zhang & Wang, Citation2009). This is due to the belief that children are more susceptible to health risks resulting from consuming unhealthy/unsafe food products (Roitner-Schobesberger et al., Citation2008; Zhang & Wang, Citation2009).

Moreover, the ordered probit regression indicates that the number of aged in a household has a statistically significant (at 1%) and negative coefficient (). This means that the number of aged in a household (members above 60 years) boosts the amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The marginal effects show that number of aged in a household is significant and positive for no and low WTP bids, but negative for moderate and premium WTP bids. As the number of aged in a consumer’s household increases by one member, the likelihood of unwillingness to pay and paying low WTP bids increase by 19.9% and 19.3% respectively. However, as the number of aged in a household increases by one member, the likelihood of paying moderate and premium WTP amounts reduces by 31.6% and 7.6% respectively. Hence, consumers with more aged in their households are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. In contrast, consumers with fewer aged in their households are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. The reason could be attributed to the lower level of egg consumption among the aged relative to younger people. The foregoing indicates that household composition in terms of number of children, adults and aged influence food choices and WTP for chicken eggs with enhanced qualities/attributes. Similarly, Kasteridis and Yen (Citation2012); Acquah (Citation2011); Quagrainie (Citation2006) observed that number of children, adults and aged in a household influence consumers’ food preferences, expenditure and choice of food safety.

The number of dependents has statistically significant (at 1%) and negative coefficients in the truncated and ordered probit regressions. This suggests that the amounts consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes reduces with a number of dependents. The marginal effects in the ordered probit regression reveal that the number of dependents is significant and positive for no and low WTP bids, but negative for moderate and premium WTP bids. As a consumer’s number of dependents increases by one, the probability of unwillingness to pay and paying low WTP bids increase by 6.8% and 6.6% respectively. However, as the number of dependents increases by one, the probability of paying moderate and premium WTP amounts decrease by 10.8% and 2.6% respectively. Hence, consumers with many dependents are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Conversely, consumers with fewer dependents are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. Consumers with more dependents have a higher financial burden (including food expenditure). Since chicken eggs with enhanced attributes are relatively more expensive, such consumers are likely to cut down expenditure on food by paying less.

The truncated and ordered probit regressions showed attitudinal characteristics of the Extended Theory of Reasoned Action (ETRA) like income, food expenditure and quantity of eggs consumed determine consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Income has a statistically significant (at 5%) and positive coefficient in the ordered probit estimation (). This means that income increases consumers’ WTP for chicken eggs with improved qualities. The marginal effects show that income is significant and negative for no and low WTP bids, but positive for moderate and premium WTP bids. As a consumer’s income increases by US$1, the likelihood of unwillingness to pay and paying low WTP bids reduce by 6% and 5%, respectively. Nonetheless, as income increases by US$1, the likelihood of paying moderate and premium WTP amounts rises by 9% and 2%, respectively. Thus, low-income consumers are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Conversely, high-income consumers are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. High-income consumers are better able to afford reasonably expensive food products than low-income consumers. Since enhancement in chicken egg attributes results in a higher price, it is rational that high-income consumers had higher WTP for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes than low-income consumers.

The ordered probit estimation also indicates that food expenditure has a statistically significant (at 5%) and negative coefficient. This implies that consumers who spend more on food are less likely to pay more for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes and vice versa. The marginal effects indicate that consumers with high food expenditure are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or to pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Conversely, consumers with low food expenditure are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. Chicken eggs with enhanced attributes are more expensive. Thus, it is reasonable that households that are already incurring higher food expenditure are unprepared to pay higher WTP bids.

From the truncated regression, the quantity of eggs consumed is another attitudinal characteristic that significantly and negatively influences consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. This implies that as the quantity of chicken eggs consumed increases, the possibility that a consumer would be prepared to pay more for improved attributes declines. Consumption of higher quantities of eggs is likely to raise household food expenditure. Therefore, to reduce food expenditure, households that consume higher quantities of eggs might be unprepared to pay higher WTP bids.

Moreover, the subjective norm characteristics of the ETRA that significantly influence consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes are the level of satisfaction with the hygiene of vending surrounding/environment and customer care. Furthermore, attributes of chicken eggs that significantly influence consumers’ WTP higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes are the level of satisfaction with the size of eggs, shell quality/hardness, and neatness of eggshell. These subjective norm characteristics and attributes of chicken eggs have statistically significant negative coefficients in the truncated and ordered probit regressions. This infers that being satisfied with these attributes lowers the amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. The marginal effects in the ordered probit estimation indicate that satisfaction with these attributes is significant and positive for no and low WTP bids, but negative for moderate and premium WTP bids (). Therefore, consumers who were satisfied with these attributes are more likely to be unwilling to pay higher prices or would pay low WTP bids for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. In contrast, consumers with low satisfaction levels are more likely to pay moderate or premium WTP bids. As a result, consumers who were unsatisfied with chicken egg qualities had higher WTP for an upgrade than those who were satisfied. This could be because consumers satisfied with the current chicken egg attributes in the market would not be prepared to pay more for further improvements. In agreement with this finding, Amfo and Ali (Citation2021) reported that satisfaction with attributes of animal products reduces WTP for an upgrade.

6. Conclusions, policy implications, limitations and future directions

This study investigates the choice of purchase outlets, consumers’ satisfaction with qualities/attributes of chicken eggs, WTP for enhanced chicken egg attributes in Ghana, and the determining factors. To achieve this, the study applied applying the extended theory of reasoned action (ETRA) and means-end theory (MET) as well as truncated and ordered probit regressions. The major purchase outlets of chicken eggs in Ghana are retailers, poultry farmers and food vendors. Qualities/attributes considered for the study are price, neatness, hygiene of vending surroundings, size, shell quality/hardness, absence of cracks on shells, packaging, consistency in supply, and customer care certification by authorities. Generally, consumers had a lower level of satisfaction with chicken egg price, neatness, hygiene of vending surroundings, size, and customer care. However, they were generally satisfied with chicken egg shell quality/hardness, absence of cracks on shells, packaging, consistency in supply, and certification by authorities. Majority (83%) of the consumers were willing to pay higher prices for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes. Amount consumers were willing to pay for chicken eggs with enhanced attributes ranged from 10–80% increase in market price (that is US$2.64–US$4.32 per crate). On average, consumers were willing to pay a 33% increase in the market price of chicken eggs with enhanced attributes (that is US$3.18 per crate).

Demographic, attitudinal and subjective norm characteristics, as well as the level of satisfaction with attributes of chicken eggs influence consumers’ WTP higher prices for enhanced attributes. The demographic characteristics are sex, education, number of children and aged in a household, and number of dependents. Income, food expenditure and quantity of eggs consumed are the attitudinal characteristics. Moreover, the subjective norm characteristics are the level of satisfaction with the hygiene of vending surrounding/environment and customer care while the attributes of chicken eggs are the level of satisfaction with the size of eggs, shell quality/hardness, and neatness of eggshell. Specifically, male and educated consumers, households with many children, consumers with fewer dependents, high income households, households with low food expenditure, and consumers who are unsatisfied with chicken egg attributes had higher WTP. It is generally concluded that there is low satisfaction with certain chicken egg attributes and high WTP for enhanced chicken egg attributes.

Generally, the results revealed that consumers’ WTP for enhanced chicken attributes is influenced by the chicken attributes, subjective norms and attitudinal characteristics of consumers. It suggests that the ETRA could be used to understand consumer behaviour relative to purchasing of enhanced agricultural produce attributes, particularly chicken eggs.

The low level of consumers’ satisfaction with certain attributes of chicken eggs and the high level of WTP calls for an enhancement in attributes by producers and traders. Therefore, there is a good market potential for enhanced chicken egg attributes, especially improving the neatness, hygiene of vending surrounding/environment, size, and customer care. Such chicken eggs with enhanced attributes could be sold at moderate prices (about a 33% increase in market price). The market for such enhanced products should target educated consumers, consumers with fewer dependents, high-income households. Regarding policy, district assemblies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) interested in food safety should train poultry farmers and other agricultural commodity value chain actors, particularly chicken eggs, on the desired attributes in meeting consumer satisfaction and gaining from this marketing opportunity. This training will enable poultry producers and other actors to improve chicken egg attributes for consumer satisfaction.

In terms of theory, the study revealed that the ETRA could be used to explain consumer behaviour relative to enhanced chicken eggs in Ghana. Additionally, it is suggested that future consumer studies on agribusiness products should consider the ETRA to confirm or otherwise this theory usage in consumer surveys. Further studies on ETRA could consider consumer segmentation based on ETRA characteristics for effective market strategy by agricultural produce value chain actors.

In relation to the limitation of the study, the study was limited to a predominant poultry-producing zone in Ghana. Therefore, the results might not reflect the whole of Ghana and the dynamics relative to other primary chicken-consuming cities. This limitation highlights the generalizability issues of the findings. Therefore, future studies should consider the major chicken-consuming areas or a combination of both major producing and consumption cities to reveal consumer dynamics for necessary recommendations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bismark Amfo

Bismark Amfo is a lecturer at Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics in University of Energy and Natural Resources, Ghana. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, an MPhil in Agricultural Economics, and a BSc in Agribusiness from University for Development Studies. His research interest borders on agricultural finance (agricultural financial economics), migration and labour economics, and consumer studies. He has conducted various studies in the agricultural sector, published a number of papers in Scopus indexed journals, and consulted for organizations like GIZ, John A. Kufuor Foundation, and Northern Rural Growth Programme.

Richard Kwasi Bannor

Richard Kwasi Bannor is an Associate Professor of Agribusiness Management at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies at the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Ghana. He is also the current Ghana Society of Agribusiness Scientists (GSAS) President and the Faculty Advisor for Kosmos Innovation Centre’s AgriTech Challenge at the University. For over eight years, he has researched the development and sustaining of Agribusiness MSMEs in Africa, Asia and Europe, mainly in Agricultural and Rural Marketing and Agribusiness Value and Supply Chains. Consequently, Bannor has over 70 research publications in peer-reviewed international journals and four drone patents in Australia, the UK, and Germany. His current research focuses on celebrity and digital marketing, food standards, agribusiness consumers’ behaviour, labelling and packaging, agricultural intellectual property regimes and TQM practices in agribusiness marketing and supply chains.

Abigail Oparebea Boateng

Abigail Oparebea Boateng is a Lecturer in the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies at the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Ghana. She is a member of the Ghana Society of Agribusiness Scientists (GSAS). Her current research focuses on supply chains, human resources management, organizational behaviour and consumer studies in agribusiness.

Helena Oppong-Kyeremeh

Helena Oppong-Kyeremeh is a Senior Lecturer in Agribusiness Management at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies at the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Ghana. She is a member of the Ghana Society of Agribusiness Scientists (GSAS) and focuses on advancing agribusiness research. She has about 40 research publications in peer-reviewed, internationally recognized journals. Currently, her research areas include branding agricultural products, agri-commodity value and supply chains as well as consumer studies in agribusiness.

References

- Ackermann, C. L., & Palmer, A. (2014). The contribution of implicit cognition to the theory of reasoned action model: a study of food preferences. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(5–6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.877956

- Acquah, H. (2011). Farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change: a willingness to pay analysis. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13(5), 150–161.

- Aitken, R., Watkins, L., Williams, J., & Kean, A. (2020). The positive role of labelling on consumers’ perceived behavioural control and intention to purchase organic food. Journal of Cleaner Production, 255, 120334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120334

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs. Prentice-Hall.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracín, B.T. Johnson and M.P. Zanna (Eds.), the handbook of attitudes (pp. 173–221). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

- Alimi, B. A., & Workneh, T. S. (2016). Consumer awareness and willingness to pay for safety of street foods in developing countries: a review. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(2), 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12248

- Amfo, B., & Ali, E. B. (2021). Consumer satisfaction and willingness to pay for upgraded meat standards in Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 33(4), 423–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2020.1812464

- Amfo, B., Ansah, I. G. K., & Donkoh, S. A. (2019). The effects of income and food safety perception on vegetable expenditure in the Tamale Metropolis, Ghana. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 9(3), 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2018-0088

- Ampuero, O., & Vila, N. (2006). Consumer perceptions of product packaging. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(2), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760610655032

- Ansah, I. G. K., & Tetteh, B. K. D. (2016). Determinants of yam postharvest management in the Zabzugu District of northern Ghana. Advances in Agriculture. 2016(2016), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9274017

- Ayim-Akonor, M., & Akonor, P. T. (2014). Egg consumption: patterns, preferences and perceptions among consumers in Accra metropolitan area. International Food Research Journal, 21(4), 1457–1463.

- Bannor, R. K., & Abele, S. (2021). Consumer characteristics and incentives to buy labelled regional agricultural products. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 17(4), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-12-2020-0173

- Bannor, R. K., Abele, S., Kuwornu, J. K. M., Oppong-Kyeremeh, H., & Yeboah, E. D. (2020). Consumer segmentation and preference for indigenous chicken products. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 12(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-08-2020-0162

- Bannor, R. K., Oppong-Kyeremeh, H., & Kuwornu, J. K. M. (2021). Examining the link between the theory of planned behavior and bushmeat consumption in Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 41(8), 745–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2021.1944881

- Bejaei, M., Wiseman, K., & Cheng, K. M. (2011). Influences of demographic characteristics, attitudes, and preferences of consumers on table egg consumption in British Columbia, Canada. Poultry Science, 90(5), 1088–1095. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2010-01129

- Ben, C. B. (2015). The role of rural women farmers in household food security in Cross River State, Nigeria. Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 4(3), 137–144.

- Bett, H. K., Peters, K. J., Nwankwo, U. M., & Bokelmann, W. (2013). Estimating consumer preferences and willingness to pay for the under utilised indigenous chicken products. Food Policy. 41, 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.05.012

- Borgardt, E. (2020). Means-end chain theory: a critical review of literature. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 64(3), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.15611/pn.2020.3.12

- Carpenter, G. E. (2016). Analyzing consumers’ willingness to pay for eco-labelled seafood products in Coastal and Inland Maine Counties. Journal of Environmental and Resource Economics at Colby, 3(1), 10–23.

- Changhee, K., & Chanjin, C. (2011). Hedonic analysis of retail egg prices using store scanner data: an application to the Korean egg market. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 42(3), 1–4.

- Chaniotakis, I., Lymperopoulos, C., & Soureli, M. (2010). Consumers’ intentions of buying own-label premium food products. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 19(5), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421011068568

- Cobbinah, M. T., Donkoh, S. A., & Ansah, I. G. K. (2018). Consumers’ willingness to pay for safer vegetables in Tamale, Ghana. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 10(7), 823–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2018.1519062

- Conner, M., & Armitage, C. (2006). Social psychological models of food choice. The Psychology of Food Choice, 3(2006), 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851990323.0041

- de Graaf, S., Vanhonacker, F., van Loo, E. J., Bijttebier, J., Lauwers, L., Tuyttens, F. A. M., & Verbeke, W. (2016). Market opportunities for animal-friendly milk in different consumer segments. Sustainability, 8(12), 1302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121302

- de Pee, S, Bloem, M W, Yip, R, Sukaton, A, Tjiong, R, Shrimpton, R, Kodyat, B, Satoto, Muhilal,. (1998). Impact of a social marketing campaign promoting dark-green leafy vegetables and eggs in central Java, Indonesia. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 68(6), 389–398.

- Demont, M., & Ndour, M. (2016). Upgrading rice value chains: experimental evidence from 11 African markets. Global Food Security, 5(2015), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.10.001

- Fabbrizzi, S., Marinelli, N., Menghini, S., & Casini, L. (2017). Why do you drink? A means-end approach to the motivations of young alcohol consumers. British Food Journal, 119(8), 1854–1869. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2016-0599

- Gallegos-Riofrío, C. A., Waters, W. F., Salvador, J. M., Carrasco, A. M., Lutter, C. K., Stewart, C. P., & Iannotti, L. L. (2018). The Lulun Project’s social marketing strategy in a trial to introduce eggs during complementary feeding in Ecuador. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(Suppl 3), e12700. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12700

- Gangnat, I. D., Mueller, S., Kreuzer, M., Messikommer, R. E., Siegrist, M., & Visschers, V. H. (2018). Swiss consumers’ willingness to pay and attitudes regarding dual-purpose poultry and eggs. Poultry Science, 97(3), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pex397

- Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Gutman, J. (1982). A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. Journal of Marketing, 46(2), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600207

- Hanemann, M., Loomis, J., & Kanninen, B. (1991). Statistical efficiency of double‐bounded dichotomous choice contingent valuation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 73(4), 1255–1263. https://doi.org/10.2307/1242453

- Hung, Y., & Verbeke, W. (2018). Sensory attributes shaping consumers’ willingness-to-pay for newly developed processed meat products with natural compounds and a reduced level of nitrite. Food Quality and Preference, 70(2018), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.02.017

- Hung, Y., de Kok, T. M., & Verbeke, W. (2016). Consumer attitude and purchase intention towards processed meat products with natural compounds and a reduced level of nitrite. Meat Science, 121(2016), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.06.002

- Hyun, J., Cho, H., Xu, W., & Fairhurst, A. (2010). The influence of consumer traits and demographic on intention tp use self- service checkouts. Journal of Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501011014606

- Imelia, R., & Ruswanti, E. (2017). Factors affecting purchase intention of electronic house wares in Indonesia. International Journal of Business and Management Invention ISSN, 6(2), 37–44. www.ijbmi.org

- Islam, T., & Hussain, M. (2022). How consumer uncertainty intervene country of origin image and consumer purchase intention? The moderating role of brand image. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(11), 5049–5067. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-08-2021-1194

- Jang, H. W., & Cho, M. (2022). The relationship between ugly food value and consumers’ behavioral intentions: application of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 50, 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.02.009

- Karipidis, P., Tsakiridou, E., Tabakis, N., & Mattas, K. (2005). Hedonic analysis of retail egg prices. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 33(3), 68–73.

- Kassali, R., Kareem, R. O., Oluwasola, O., & Ohaegbulam, O. M. (2010). Analysis of demand for rice in Ile Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12(2), 63–78.

- Kasteridis, P., & Yen, S. T. (2012). U.S. demand for organic and conventional vegetables: A Bayesian censored system approach. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 56(3), 405–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8489.2012.00589.x

- Kim, J., Shim, K., Kim, M.-S., & Youn, M.-K. (2013). Analyzing factors influencing purchasing behavior of PB eggs: Focusing on eggs from large distribution companies. Journal of Distribution Science, 11(10), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.15722/jds.11.10.201310.107

- Kralik, I., Zelić, A., Kristić, J., Milković, S. J., & Crnčan, A. (2020). Factors affecting egg consumption in young consumers. Acta Fytotechnica et Zootechnica, 23, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.15414/afz.2020.23.mi-fpap.1-6

- Kumar, A., & Smith, S. (2018). Understanding local food consumers: theory of planned behavior and segmentation approach. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 24(2), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2017.1266553

- Lee, H. J., & Yun, Z. S. (2015). Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food Quality and Preference, 39, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.06.002

- Lesnierowski, G., & Stangierski, J. (2018). What’s new in chicken egg research and technology for human health promotion? A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 71, 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.10.022

- Liu, A., & Niyongira, R. (2017). Chinese consumers food purchasing behaviors and awareness of food safety. Food Control. 79(79), 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.03.038

- Lordelo, M., Fernandes, E., Bessa, B. R. J., & Alves, S. P. (2017). Quality of eggs from different laying hen production systems, indigenous breeds and specialty eggs. Poultry Science, 96(5), 1485–1491. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pew409

- Maddala, G. S. (1983). Limited dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics (pp. 401). Cambridge University Press.

- Marquis, G. S., Colecraft, E. K., Kanlisi, R., Pinto, C., Aryeetey, R., Aidam, B., & Bannerman, B. (2017). Improving children’s diet and nutritional status through an agriculture intervention with nutrition education in upper Manya Krobo District of Ghana. The FASEB, 31, 455–458.

- Mesías, F. J., Martínez-Carrasco, F., Martínez, J. M., & Gaspar, P. (2011). Functional and organic eggs as an alternative to conventional production: A conjoint analysis of consumers’ preferences. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 91(3), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4217

- Min, S., Overby, J. W., & Im, K. S. (2012). Relationships between desired attributes, consequences and purchase frequency. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(6), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211259232

- Morales, L. E., & Higuchi, A. (2018). Is fish worth more than meat? How consumers’ beliefs about health and nutrition affect their willingness to pay more for fish than meat. Food Quality and Preference, 65, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.11.004

- Nimalaratne, C., & Wu, J. (2015). Hen egg as an antioxidant food commodity: A review. Nutrients, 7(10), 8274–8293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7105394

- Olson, J. C., and Reynolds, T. J. (Eds.) (2001). Understanding consumer decision making: the means-end approach to marketing and advertising strategy. Routledge.

- Petrovici, D. A., Ritson, C., & Ness, M. (2004). The theory of reasoned action and food choice: insights from a transitional economy. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 16(1), 59–87. https://doi.org/10.1300/J047v16n01_05

- Procter, L., Angus, D. J., Blaszczynski, A., & Gainsbury, S. M. (2019). Understanding use of consumer protection tools among Internet gambling customers: utility of the theory of planned behavior and theory of reasoned action. Addictive Behaviors, 99, 106050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106050

- Quagrainie, K. (2006). IQF catfish retail pack: a study of consumers’ willingness to pay. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 9(2), 75–87.

- Roitner-Schobesberger, B., Darnhofer, I., Somsook, S., & Vogl, C. R. (2008). Consumer perceptions of organic foods in Bangkok, Thailand. Food Policy. 33(2), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.09.004

- Rondoni, A., Asioli, D., & Millan, E. (2020). Consumer behaviour, perceptions, and preferences towards eggs: A review of the literature and discussion of industry implications. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 106, 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.10.038

- Ryan, J., & Casidy, R. (2018). The role of brand reputation in organic food consumption: A behavioral reasoning perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 41, 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.01.002

- Saleem, A., Aslam, J., Kim, Y. B., Nauman, S., & Khan, N. T. (2022). Motives towards e-shopping adoption among Pakistani consumers: An application of the technology acceptance model and theory of reasoned action. Sustainability, 14(7), 4180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074180

- Shah, S. S. H., Aziz, J., Jaffari, A. R., Waris, S., Ejaz, W., Fatima, M., & Sherazi, S. K. (2012). The impact of brands on consumer purchase intentions. Asian Journal of Business Management, 4(2), 105–110.

- Shim, J., Moon, J., Song, M., & Lee, W. S. (2021). Antecedents of purchase intention at starbucks in the context of covid-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(4), 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041758

- Singh, G., Aiyub, A. S., Greig, T., Naidu, S., Sewak, A., & Sharma, S. (2023). Exploring panic buying behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A developing country perspective. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(7), 1587–1613. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-03-2021-0308

- Situmorang, R. O. P., Tang, M. C., & Chang, S. C. (2022). Purchase intention on sustainable products: A case study on free-range eggs in Taiwan. Applied Economics, 54(32), 3751–3761. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.2001423

- Slack, N. J., & Singh, G. (2020). The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction and loyalty and the mediating role of customer satisfaction: supermarkets in Fiji. The TQM Journal, 32(3), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-07-2019-0187

- Slack, N. J., Sharma, S., Cúg, J., & Singh, G. (2023). Factors forming consumer willingness to pay a premium for free-range eggs. British Food Journal, 125(7), 2439–2459. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2022-0663

- Slack, N., Singh, G., & Sharma, S. (2020). The effect of supermarket service quality dimensions and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty and disloyalty dimensions. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 12(3), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-10-2019-0114

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata: Release 14. Statistical software. StataCorp LP, Texas, USA.

- Wang, J., Ge, J., & Ma, Y. (2018). Urban Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for pork with certified labels: A discrete choice experiment. Sustainability, 10(3), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030603

- Wang, J., Xu, C., & Liu, W. (2022). Understanding the adoption of mobile social payment: From the cognitive behavioural perspective. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 20(4), 483–506. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2022.123794

- Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. F. (1996). Know your customer: New approaches to understanding customer value and satisfaction. Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

- Xia, F., Zhao, Y., Xing, M., Sun, Z., Huang, Y., Feng, J., & Shen, G. (2022). Discriminant analysis of the nutritional components between organic eggs and conventional eggs: A 1H NMR-based metabolomics study. Molecules, 27(9), 3008. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27093008

- Żakowska-Biemans, S., & Tekień, A. (2017). Free range, organic? Polish consumers preferences regarding information on farming system and nutritional enhancement of eggs: a discrete choice based experiment. Sustainability, 9(11), 1999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111999

- Zhang, H., & Wang, H. (2009). Consumers’ willingness to pay for green agricultural products in Guangzhou City. Journal of Agro-Technical Economics, 6(6), 62–69.

- Zhu, Y., Wen, X., Chu, M., & Sun, S. (2022). Consumers’ intention to participate in food safety risk communication: a model integrating protection motivation theory and the theory of reasoned action. Food Control. 138(2022), 108993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108993