Abstract

Waste management (WM) is fundamental for sustainable development; however, practices and approaches vary between developed and developing countries. Costa Rica belongs to the latter group, and although the country has shown a steady commitment toward sustainability, WM and food waste (FW) interventions are still one major challenge. There is a research gap regarding household FW-related behavior and local governments’ performance in terms of sustainability. Therefore, our study aims to address this gap by analyzing the behavior of household FW generators, linking it to the WM actions of municipalities, and contributing to local policies. The study considered a sample of households in the Greater Metropolitan Area of the country to determine consumer drivers for waste, specifically regarding their intention to avoid FW, and conducted a structural equation model based on behavioral constructs. An expert consultation with the local government’s environmental managers was also performed to address their WM policy approach. The findings indicate household FW management is driven by values, perceived behavioral control, social norms, and socioeconomic characteristics but mainly by external aspects, such as local government enabling (or disabling) actions toward FW reduction. Opportunities and policy interventions could arise when local governments recognize the potential of sound WM alternatives, beginning with options for separate organic waste collection, and following with treatments to generate value and appropriate WM approaches.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Waste management (WM) is relevant to many topics such as environmental protection, public health, or resource efficiency. Municipal solid waste (MSW) is a studied topic in scientific literature and the center of attention for most urban and rural policies due to their impact on municipal budgets and socio-environmental implications that threaten human and ecological health, through water and soil contamination, and the attribution to global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) (Fridahl & Lehtveer, Citation2018). Consequently, both developed and developing countries rely on integrated WM strategies to address the MSW issue (Margallo et al., Citation2019).

Managing waste often starts with assessing and monitoring waste generation, and the results from that monitoring, together with other publications (Gustavsson et al., Citation2011; UNEP, Citation2015), have called attention to the organic fraction, particularly food waste (FW). Due to the significant contribution of the organic materials in MSW and its impact on the sustainability of food systems, FW has become a trending topic at different levels of society, whether it refers to scientific papers, food safety and security fora, or WM structures. In fact, the current Farm to Fork strategy and the Circular Economy Plan of the European Union (as part of the Green Deal) include FW within their scope (Barquero et al., Citation2023), possibly triggering attention to this topic in other regions of the world.

FW represents a heavy societal burden because of its environmental, economic, and social effects (UNEP, Citation2021). Climate change is perhaps one of the most commonly associated effects since MSW and particularly its organic fraction (mostly constituted by FW) entails the emission of methane, a relevant GHG, during uncontrolled waste degradation in dumps and landfills (DCC, Citation2020a; UNEP, Citation2015; Citation2021). In addition, the footprint of food production through its life cycle is enhanced when this food is not utilized as expected to feed and nourish people and ends up being wasted (FAO, Citation2019). Therefore, many actions are currently driven by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), especially under target SDG 12.3, which aims for prevention and reduction of FW. These latter are key elements for food systems and sustainable cities; however, dealing with FW is complicated since it responds to methodological, technical, infrastructural, governance, behavioral, and policy challenges, highlighting household-level FW as crucial for efficient WM systems. Recent studies, such as the one conducted by Vittuari et al. (Citation2023), identified thirteen FW drivers and levers connected to motivations, opportunities, abilities, and demographics. According to UNEP (Citation2021), a person generates 121 kg FW/year, from which 74 kg/capita/year occur in households. Consequently, understanding the quantity, trends, and drivers behind FW can determine more efficient interventions, policies, and strategies for better MSW approaches.

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP, Citation2015) affirms that MSW status and management differ profoundly among regions. Waste generation depends on income level, climatic factors, and socio-cultural features, often varying between high-income countries in contrast to low and middle-income countries (UNEP, Citation2015). In addition, several studies have addressed consumer behavior and its relationship to sustainable practices and FW. However, most research on these topics emerges in the Global North, presenting a research gap regarding household FW-related behavior and local governments’ performance in the Global South.

The Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region has shown relevant breakthroughs in MSW management in the past decade. Costa Rica, a LAC country, has shown a steady commitment toward sustainability, usually making this nation an object of study in the Region. As examples of that commitment, the Integral Waste Management Law no. 8839 (published in 2010), the National Waste Management Plan 2016–2021, and the Circular Economy Strategy have shaped many of the MSW actions in the country (DCC, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Ministerio de Salud, Citation2016; SCIJ, Citation2023a). In recent years, the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and the significant presence of biowaste in the MSW generation rate (over 50%) inspired the National Composting Plan 2020–2050, aiming to achieve zero-organic-waste landfills in the future (MinSalud & MINAE, Citation2021). However, low recovery rates, unsuitable collection and disposal systems, and low technology adoption still burden Costa Rica (and, generally, developing countries from LAC), urgently calling for integrated views to support appropriate WM and FW policies (Margallo et al., Citation2019).

Bearing in mind that socioeconomic variables, values, and social norms vary among different geographical regions, this paper aims to determine the behavior of FW household generators and its connection to the local governments concerning FW management policies based on the Costa Rican case study. To do this, we determined the current state of FW management and drivers in households since it is where most food is wasted (UNEP, Citation2021), by analyzing how a modified Theory of Planned Behavior′s constructs affect FW management in households. In addition, we contrasted this information with policies and actions from local governments (or municipalities) since FW management does not depend solely on consumers’ behavior but rather on joint efforts between local governments and households. Consequently, this research contributes to local policymaking in Costa Rica, as well as in similar developing countries, through a better understanding of the underlying factors in FW reduction and domestic waste management (particularly FW) and associated drivers.

2. Theoretical framework

Explaining human behavior is a complex task and advancements in this discipline have presented many methodological and theoretical approaches. Therefore, this chapter supports the approach we followed in our research by summarizing the main theories and studies behind FW drivers from a general view to the scattered and still limited studies in LAC and, particularly, Costa Rica.

The idea from Ajzen (Citation1985, Citation1991) that behavior depends on intention has been widely proven. In this regard, intention is based on three major constructs: attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, commonly known as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). However, Shove (Citation2010) conducted a critical appraisal and broadened the perspective of what has been considered when addressing FW, by including social, economic, and cultural issues and parameters, allowing the analysis to undergo beyond psychological factors. In consequence, Graham-Rowe et al. (Citation2015) significantly predicted household fruit and vegetable waste using an extended TPB framework in the UK, and although socioeconomic variables were incorporated in the first step, gender was the only significant predictor: women have more positive intentions in reducing FW. In the second step, 54,71% of the variance was explained by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Additionally, self-identity and anticipated regret contributed significantly to the prediction of intention but not the descriptive norm. On the contrary, results from Stefan et al. (Citation2013) in Romania indicate that attitude was the only construct associated with intention and, therefore, behavior.

Sociodemographic characteristics are variables associated with the generation of FW. The study carried out by Grasso et al. (Citation2019) in Denmark and Spain indicates that gender and household behavior play a role in FW: being a man is associated with a higher amount of FW, whereas living in a household with four or more people is associated with less FW. In addition, Aschemann-Witzel et al. (Citation2019) state that other demographic variables, such as family structure and the number of children, are related to the amount of FW generated in households after one of the very few studies in a LAC context, specifically in Uruguay. Other factors are pointed out by Bilska et al. (Citation2019), such as age, place of residence, and education, as those influencing consumer behavior and, therefore, food management at home. However, this author also coincides with gender as an influencing factor similar to other authors. Schanes et al. (Citation2018) commented on the effect of sociodemographic variables on FW and the relationship of home practices such as planning, shopping, storage, cooking, and eating.

Adding food-related routines to psycho-social factors provides alternative ways to influence FW behavior. Proper planning of purchases is usually highlighted in many studies as a factor in reducing the amount of household FW, together with its relation to the household composition; therefore, many studies (Chen, Citation2022; Wahlen, Citation2011; Evans et al., Citation2012) refer to the routine nature of domestic practices and their relationship with the amount of wasted food.

Consumer motivation are also variables that influence FW (Stancu & Lahteenmäki, 2022; Muruganantham & Bhakat, Citation2013). In addition, young people and university graduates are more likely to buy unplanned products, which translates into more waste; and excessive (unplanned) purchases.The relationship between FW and education is intricate (Ghinea et al., Citation2020). Some studies (Principato et al., Citation2021; Visschers et al., Citation2016) agree that education is positively correlated to higher rates of food waste since households with higher education also have higher income. On the contrary, other results also indicate that more educated households are also more aware of environmental concerns (Meyer, Citation2015). Therefore, more than socioeconomic variables, it is considered that food-related routines have an important impact on FW as well as psychological constructs (Stancu et al., Citation2016), although other studies suggest ‘motivations’ of consumers are used to reduce the amount of food wasted. However, these outcomes are not always consistent with the behavior of the subject and differences could be due to country-specific elements (Sheeran, Citation2011; Stefan et al., Citation2013).

There are contradictions in FW behavior results among studies, which could also be related to other non-researched constructs such as culture and intention. Steg and Vlek (Citation2009) emphasize that cognitive aspects such as attitudes, intentions, and motivations are not always good indicators to measure the reduction or increase in the amount of food wasted. On the contrary, other analyses suggest that sociological aspects contribute more to FW (Cappellini, 2009; Cappellini & Parsons, Citation2012) than other variables. Motivation and social norms have a positive and statistically significant influence that contributes to the reduction of FW for many authors have identified that the variable ‘intention’ to avoid FW was a behavioral factor that influences the reduction of wasted food at the household level (Ananda et al., Citation2023; Chen, Citation2022; Janssens et al., Citation2019; Setti et al., Citation2018; Visschers et al., Citation2016). Concerning intention, some studies have shown that purchasing behavior, the use of shopping lists, and the preference of places contribute considerably to household waste generation (Djekic et al., Citation2019; Dobernig & Schanes, Citation2019; Nabi et al., Citation2021; Stancu et al., Citation2016). Moreover, Aydin and Aydin (Citation2022), expressed that the habit of donating is a non-significant variable to measure the intention to waste food. Variables such as behavior control and attitudes significantly affect the intention to reduce FW, and social norms are considered essential factors in avoiding FW. Similarly, moral norms were the most critical construct for Chan and Bishop (Citation2013) when addressing recycling in the UK. In this research, attitudes and moral norms were positively correlated, and therefore, moral norms can replace attitudes when considering recycling, as part of WM behavior.

WM is relevant to a comprehensive approach toward lower FW. Behavior (understood as intention, motivation, attitude, and practices) in the household is not a stand-alone element of the FW reduction strategies, which can only succeed when local governments holistically enable actions for their inhabitants, whether they begin with systemic approaches to prevent FW, redistribute surplus, or install proper biowaste treatment to their context (Coste et al., Citation2021). The latter raises the need to appropriately address the socioeconomic characteristics of the population as well as their surrounding enabling conditions. Examples of the latter could include waste sorting for potential recovery alternatives and may encourage households to reduce FW at source or allow circular local approaches. Ek and Miliute-Plepiene (Citation2018) mention in their study that there is a positive effect between the adoption of differentiated sorting and waste collection practices of FW set by municipalities in relation to the amount of the FW collected. In addition, the same authors conclude that the insertion of FW separation in the households triggers other recycling behaviors, which is explained by the ‘habit discontinuity hypothesis’, understood as the disruption of initial habitual behavior when a change is introduced.

FW behavior literature is still scarce in the LAC Region. In particular, two studies in Costa Rica have measured FW and consumers’ intention to reduce FW (Montero Vega et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). However, the following points should be noted: (a) these studies have been specific to FW investigations only, (b) they have focused on particular products within different food categories, and (c) WM has not been addressed in these studies. LAC countries, including Costa Rica, face inadequate WM, and recent incorporation into the OECD supports the need to move forward with MSW management standards. Currently, MSW collection does not cover 100% of the territory, and a minimum amount of organic waste is separated from other ordinary and recyclable waste, resulting in a very low rate of composted waste (0,3%) (MinSalud & MINAE, Citation2021). According to the Costa Rican General Health Law, the issue of reducing waste generation is not contemplated as stated in the Integral Waste Management Law no.8839 (SCIJ, Citation2023a, Citation2023b), causing a gap among national WM instruments. Therefore, WM actions, for which municipalities are responsible, end up in a high percentage of wastes deposited in landfills and dumps, which do not have any technique that mitigates environmental impact nor triggers more consistent actions at the household level, similar to the overall situation in the LAC Region (UNEP, Citation2015).

3. Methods

The study integrates a set of methods first to determine the behavior behind household FW generation and then to cross-reference these findings with local governments regarding FW policies. First, the TPB and a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were applied to later connect the findings to the context through an expert consultation. It reflects data from the period 2022–2023, addressing two types of actors:

Households: these are the main subjects of the research and from which the TPB model was built by collecting questionnaires from adult household consumers of the GMA (May 2022 to May 2023). They were addressed to determine (food) waste patterns, as well as their perceptions on food, waste, circular economy, environmental issues, and their inputs concerning the local governments’ waste management policies,

Environmental managers from municipalities in the Greater Metropolitan Area (GMA): they were interviewed as part of an expert consultation from January 2023 to May 2023, and their answers would allow to cross-reference FW management findings from the households and the current municipal FW approaches. The focus was placed on the GMA due to population (and waste) concentration since more than half of Costa Ricans live in this area (PEN, Citation2018).

By adding the insights of both types of actors (consumers at households and municipal representatives), we intend to contribute to the local governments in their MSW (and FW) management policies.

3.1. Description of the case study

MSW official latest reports in Costa Rica estimated a daily generation of 4434 tons of waste in 2021 (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2023), with a per capita daily rate of 1.1 kg, from which almost half correspond to organic wastes (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2016). Unfortunately, the specific FW management is still in the initial phase, and there are no national strategies for reducing FW. The most recent SDGs country report indicates that there are no advancements for target 12.3 (United Nations, Citation2023), and even when the Costa Rican FW Network promotes actions, political and financial initiatives are still needed for a broader consideration of the issue (Bolaños-Palmieri et al., Citation2021). More recent policy development such as the I National Composting Plan 2020–2050 (DCC, Citation2020b), includes FW prevention and reduction as one of its activities, but there is no systematic WM and FW data collection; therefore, data regarding MSW, FW, household waste-sorting practices, and constructs related to the intention of ‘not to waste food’ were surveyed and analyzed in this study.

3.2. Households: consumers’ FW-related behavior

We have considered Ajzen’s (Citation1991) TPB: intention to reduce food waste would eventually lead to reducing this waste. We conducted 684 valid online questionnaires. Our requirements for sample selection were (a) citizens of the GMA, (b) adults (18 years of age and above), and (c) awareness of household consumption and waste patterns. Additionally, we have considered external factors (local government policies) and socioeconomic characteristics.

Variables addressed to determine the consumer behavior regarding FW and FW management consisted of the following:

Socioeconomic variables: a) age, b) income, c) available green space in their house, d) family size, and e) home type.

External aspects: a) waste sorting availability, b) local government sorting system, c) satisfaction of local government’s actions, and d) location of waste depositories.

TPB constructs: a) values, b) social norms, and c) perceived behavioral control, which determine the intention to ‘not to waste food’.

These variables were considered in the proposed modified Ajzen’s model and were measured through a 5-point Likert scale. In this case, our independent variable is the auto-perceived waste reported by consumers, which is an average percentage of all types of wasted food categories considered by Gustavsson et al. (Citation2011) estimates. Finally, we estimated a SEM, a commonly used method when studying behavior, considered to be a ‘combination between factor analysis and path analysis’ (Hmimou et al., Citation2023) to address how the constructs mentioned above determine the intention and behavior, which is the reduction of household food waste.

This questionnaire also included consumers’ reported perception of the practices of their local governments regarding waste management, such as the type and availability of services, i.e. sorting of waste, recycling, organic waste management, and other social services. The authors were aware of the limitations of these types of questionnaires, evidenced in the time it took to collect the responses, as well as known inaccuracies in the estimation of food waste from households (UNEP, Citation2021) or possible misinterpretations of the questions by the respondents. However, the benefits of such a technique concerning cost, coverage, access, and the possibility of extensive areas of questioning without the bias of directly answering to a researcher were a priority in this case, and sample selection criteria, together with the use of databases from municipalities, guaranteed valid responses.

3.3. Expert consultation: local governments and their current policies

This section considered the local governments’ points of view through an in-depth interview. Costa Rican local governments oversee all waste management-related aspects as mandated by WM Law no.8839 (SCIJ, Citation2023a), whether it refers to organic waste, recycling, waste logistics, or disposal. Nonetheless, there is not a homogeneous WM program in GMA, and local governments have different approaches to this issue: some have compost and education programs and recycling techniques, and some do not. In addition, the lack of a National FW strategy has resulted in some municipalities working at different paces in this matter, with a non-specific technique, metrics nor expected milestones (although many are aware and making efforts around FW). Consequently, our interest was centered on current WM policies, local programs, and/or recycling activities within each organization. The local governments were addressed in the first place by a phone call to establish direct contact with their environmental managers. This first approach was used to explain the project and the interview we intended to conduct. In the second step, the environmental managers were asked to fill out an online questionnaire or schedule an in-person interview. This consultation process allowed the collection 29 interviews based on the 32 Municipalities from the GMA of Costa Rica. The interview was guided by a semi-structured questionnaire that included yes/no, prioritization and open questions.

The obtained information from 3.2. would be later cross-referenced with the expert consultation with Environmental Managers from municipalities for further discussion.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Household socioeconomic characteristics

On average, the household size was 3.34 (sd: 1.53) persons, similar to the estimate of 3 persons/household that constitutes the national household average (INEC, Citation2022). An estimated 60% of the sample size is younger than 40 years of age (). However, although respondents are relatively young, income was more evenly distributed among the provided ranges (), indicating that respondents have higher incomes than the country’s average per quintile (INEC, Citation2022).

Table 1. Age of respondents in GMA.

Table 2. Household income of respondents in GMA (2022–2023 values).

Costa Rica, like many other countries, is experiencing population aging due to factors such as declining fertility rates and increased life expectancy. An aging population can influence the labor market and economic productivity; however, the economically active population has remained steady (PEN, Citation2018). Nonetheless, population aging can impact family structures and intergenerational relationships. For example, Grasso et al. (Citation2019) found a negative association between employment status and the amount of food wasted: those not employed tend to waste less food than people working full-time.

Regarding common waste disposal methods, it is customary for people who live mostly in rural areas and have green spaces to bury their organic waste in their backyard (SCIJ, Citation2023b); therefore, we asked about peoplés habitational status (). In this case, since the study is located in the GMA, it was expected that houses with large green areas (22.5%) were lower than conventional urban houses without green areas or very small green spaces (39.2%), followed by condos (18.6%) and apartment buildings (12.3%). Although the country has shifted in the past few years to smaller living spaces (PEN, Citation2018), urbanization is not as widespread in Costa Rica as in industrialized countries (where population density is higher, and individuals often live in vertical apartment buildings instead of horizontal housing arrangements). In this regard, the evidence shows that most of the studied population still lives in conventional urban houses and do not have large green areas. Consequently, own-waste treatment does not seem to be the common factor, coincident with official reports that account for less than 1% of organic waste being composted in the country (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2016). These cultural and infrastructure differences rise to distinct waste management possibilities and behaviors, not often mentioned in other Global North studies, such as domestic composting campaigns.

Table 3. Habitational status of respondents in GMA.

4.2. FW management and habits: its relation to external aspects

WM includes a series of steps that start with MSW generation mapping (in quantity and composition), followed by sorting of the waste (at the origin point or intermediate points, usually among organic waste, paper, glass, tin, plastic, etc.), collection (sorted or unsorted), storing, transport, treatment, and final disposal (Rodriguez Frade et al., Citation2021).

The external conditions offered by the local MSW management system and the perception from end-users (households) are relevant and linked to the habits and behaviors they express. emphasizes in sorting practices as part of WM, and presents the practice detected in households within the respondents through values from 1 (uncommon) to 5 (most common), whether it was at their homes or the municipal service. It also reflects their perception of the local WM ‘overall’ service (values from 1-low satisfaction to 5-high satisfaction).

Table 4. External conditions of waste management.

In general, people consider the sorting of waste, as part of WM, at the source only requires a little time or effort according to the household responses (PBC1 ), and although self and local government waste-sorting practices were uncommon, average satisfaction with the general WM service was mid-high (). The latter indicates that consumers have yet to place a higher value on recovery, recycling, and waste treatment as part of the waste management policies when addressing the local governments’ action plans. In other words, they consider local governments not to do the best job (a value of 5 was not observed in any of the answers); however, they feel relatively satisfied with current WM policies.

Table 5. Construct Items considered in the model.

In consequence, results from raise one question: what do consumers actually understand as waste management? Do they rely solely on their waste being removed (collected) from their houses or do they consider how and where the waste is treated and finally disposed of? MSW management is more spread in urban areas (UNEP, Citation2015) like the one from the study; therefore, the collection service is relatively steady. In addition, 49,8% of our respondents ignored where the Municipal collection or recycling center was located in their communities. Thus, consumers’ satisfaction can be understood under this scope.

When considering recycling practices (note: for this study purposes we rely on the fact that in the Costa Rican context, most people refer to ‘own waste sorting’ as a recycling practice, although recycling occurs somewhere else), around 50% of our respondents mention cleaning, washing, and sorting some of their waste, especially plastic, paper, glass, cans, and tetra packs. However, organic residues are mostly discarded as traditional garbage or ordinary waste, becoming part of the MSW problem. This situation occurs because of two main reasons: 1) there is no other alternative for sole segregation of organic waste in most municipalities; 2) most consumers do not know how else to treat their organic waste. Even when domestic composting seems to be increasing (Campos-Matarrita, Citation2022) and consumers find food waste as a relevant issue (PBC3, ), consumers somehow believe that, since food/organic waste decomposes quickly (N3 in ), there is no need for an added effort. Therefore, the latter indicates that this is a two-sided problem of perception and the importance placed upon organic (food) waste as an environmental problem.

4.3. Constructs and consumer behavior model regarding food household waste

Values, social norms, and perceived behavioral control (associated with Ajzen’s TPB) were studied as they also can determine consumer behavior (). The mean and standard deviation (Sd) are presented after the variables were measured on a 5-Likert scale (values fluctuate between 1 and 5).

Results indicate that, on average, people are aware of environmental aspects such as environmental damage, the importance of a healthy environment, and their concern for climate change, which can be expected since it has become a popularized term and concern in current news. In addition, food waste is recognized as a relevant issue that must be addressed, along with the need to improve measures to achieve a better environment to live in. However, even when these values are of high importance (mean was always above 4), not all purchase-related practices are as consistent; for instance, consumers recognize their purchasing habits do not always reflect their environmental concerns, nor are they always responsible consumers. Social norms present that consumers expect ‘everyone’ to sort their waste and plan their food purchases and consumption since these are also at the top of consumers’ behavior and standards and are not perceived as difficult for them. Nonetheless, when contrasting these responses to household sorting systems, we were able to observe that although most people claim this is important and not difficult to do, 46,41% of our sample responded to not sorting their waste or only doing it partially, giving vary low value to own waste-sorting (see ).

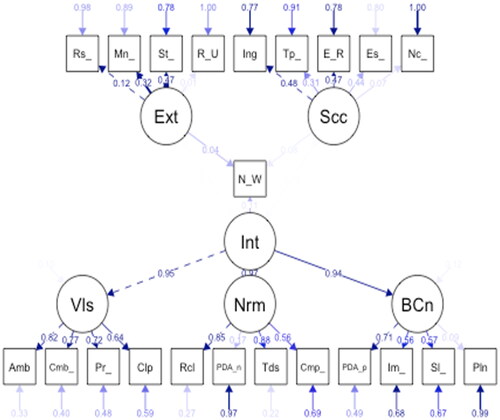

After gathering socioeconomic variables and external aspects related to the households’ WM and FW management, as well as the studied constructs, we next proposed our model, through a two-step SEM (). The first step indicates that ‘not wasting’ (N-W) depends on external factors (Ext, such as recycling policies and local governments’ actions), socioeconomic variables (Scc), and intention (Int). In the second step, Intention is understood as the regression of Values (Vls), Social Norms (Nrm), and Perceived Behavioral Control (BCn).

In addition, and present both the specifications and components of the model, and the regression statistics respectively.

Table 6. Model components and specifications.

Table 7. Regressions statistic.

Table 8. Final disposal of waste collected by municipalities in Costa Rica.

The model fit consists of a Comparative Fit Index (CFI): 0.842, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI): 0.818 and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA): 0.068 and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) of 0.062

Social aspects (Scc) are the least influential set of variables for our study (); however relevant findings shall be observed. Scc are mainly influenced by age (1,013) and income (1) as seen in . The socioeconomic characteristics from the studied sample describe these consumers as relatively young and of higher income than the average population. However, although most studies suggest that significant food waste tends to occur in higher-income economies, individuals, or populations (UNEP, Citation2015, Citation2021), as well as in younger consumers rather than elders (Vittuari et al., Citation2023), in our case, both variables are positively correlated to waste reduction. In addition, even if family size has been a significant indicator of food waste in other studies (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2019), our results do not support this relationship.

Intention sits at the intermediate level of influence (). Values (Vls) are most influenced by the importance people place on consuming environmental products, on climate change and less, on guilt. Social norms (Nrm) rely on the importance of social collective behavior and on the importance of their own sorting of waste, which is relevant since consumers distribute responsibilities among others but also among themselves (Stancu and Lahteenmäki, 2022). Regarding Perceived Behavioral Control (BCn), the awareness that FW is a problem for all and that the decision-making process of buying can contribute to the environment, are the leading variables explaining this construct. In contrast to Schanes et al. (Citation2018) and Stancu and Lähteenmäki (Citation2022), planning food purchases (PBC5 in ) has a lower impact on food household waste than other variables such as external aspects. Our results indicate a higher impact of environmental (PBC4) and health concerns (PBC6) of consumers and the impact of these decisions on waste.

Finally, External aspects (Ext) hold the highest influence in our model (); therefore (food) waste reduction in this case, is better explained by external aspects), which indicate consumers may feel constrained when it comes to WM. Even though waste-sorting systems in the country have evolved in the past few years (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2023), if better external conditions (local government facilities and management; ) were available, we could expect a waste reduction, or at least a better sorting system that consists of a lower volume of food waste being disposed of and potentially a higher possibility for it to be treated. For instance, van der Werf et al. (Citation2018) detected that households with access to a waste segregation method (i.e. green bin program) had significantly less FW final disposal than those without access to a similar system. Specifically in the studied population, most importance and explanatory power () are placed on satisfaction with the local government’s performance, followed by the local government WM (according to the respondent’s interpretation of WM). In this regard, the local government’s approach is extremely relevant to create any incidence in the context of the studied population toward FW management, as proven by Coste et al. (Citation2021) and Ek and Miliute-Plepiene (Citation2018) and the encouragement that municipal WM alternatives can create in households and their habits.

4.4. Municipal approach and policy-making aspects

According to the experts, 34.48% of waste currently collected by municipal governments is not directed to a sanitary landfill since part of it is managed by a private party (20,7%), which provides different disposal or treatment services, and only 13.8% of these are deposited in dumps, consistent with current reports in national and regional policies for waste management (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2016; UNEP, Citation2015) ().

Most (79.31%: 23 local governments) have a declared WM plan for their local communities. The remaining 17.24% do not report a WM plan, and 3.45% of interviewed municipalities did not answer this question. Nonetheless, ordinary waste is not treated at the municipal level, only disposed of.

As part of the municipal initiatives to improve WM, actions such as increasing and strengthening the environmental education of the Costa Rican population are of interest to create a better culture related to responsible consumption, waste generation, control, disposal, and recovery. Municipal issues such as optimizing routes for collection and hauling are also considered, as well as the possibility of applying monetary sanctions to people.

Results from the consultation indicate that the environmental departments of local governments establish the following as their primary concerns in regard to WM: waste classification, considering this as the definition of types of waste, i.e. solid, semi-solid, liquid, industrial, domestic, etc. (55.17% responded it was important while the remaining 44,83% considered it was not relevant), solid waste sorting (44.83% of the respondents considered it as important), recycling (44.83% of respondents identified this as important) and specifically organic waste separation (31.03% responded it was important while the remaining 68,97% answered it was not important at the moment). In view of the answers, 70% of the municipalities do not carry any organic waste separation from ordinary waste at all, and only 10% do so partially, supporting the national situation where only a small amount of organic waste is being treated (SCIJ, Citation2023b). In addition, it is worth mentioning that of the total number of municipalities, only 31.03% of these carry out different initiatives related to organic waste management (i.e. donation of domestic composting boxes).

Regarding municipal priorities, they establish these as first priority: 1) promotion and information for the citizenry (34.48%), 2) financial planning (27.59%), 3) the development of associations/organizations (27.59%), 4) the improvement of waste management facilities (17.24%) and 5) the development of capacities (24.14%). The issues of machinery and equipment (20.69%) and the improvement of technology (17.24%) are among the last priorities. However, for some local governments, capacity development and financial planning are classified as high-priority, with decision percentages corresponding to 20.69% and 17.24% respectively.

These results evidence major constraints for MSW management improvement, particularly in FW reduction, once they are linked to the household behavior findings. Existing guidelines and literature support that the ‘food waste hierarchy’ approach, as well as the transition to more sustainable and low-waste food systems, are key for reducing FW at the local level (Coste et al., Citation2021). In addition, raising awareness and appropriate sorting, collection, and treatment of biowaste is essential for FW reduction and the creation of circular economy opportunities. However, erratic or disregarded investment in equipment, technology, containerization, and biowaste treatment are commonly observed in LAC countries and supported by the priorities observed in our findings (Margallo et al., Citation2019).

The obtained response in the consultation regarding no specific FW management plans and WM plans that are not common for all the local governments expresses that the comprehensive management of waste and FW behavior studies are still emerging in the country. This is a multifaceted issue, involving not only the requirements of local governments but also public-private-academic alliances and the need to add efforts of consumers. Despite their existence, isolated and small-scale solutions (i.e. domestic composters donation programs) lack market power since any pursued solution will need a substantial volume of waste to capitalize on economies of scale. Recycling has been advocated as a solution, yet it only encompasses a portion of the problem, which is the management of regular and organic waste. While some households sort their recyclable waste (plastics, glass, cans, paper), mixed ordinary and organic waste is mostly discarded in sanitary landfills, remaining an environmental problem. Moreover, the energetic potential of organic material still needs to be exploited, disregarding the food material hierarchy expressed in many documents to prevent and reduce FW comprehesively (Teigiserova et al., Citation2020).

Local governments state that one of the solutions to the problem of organic waste management is related to the education of families, which is evident given the limited knowledge of consumers about the disposal of this type of waste by the local governments of GMA, evidencing that the education plan must be created and led by local governments to minimize the environmental, social and economic impact. Still, efforts are observed. Aware of the work that municipal governments have been doing to improve the social and environmental situation related to waste generation, the consulted environmental managers indicate their offices have proposed different medium to long-term projects, among which the following stand out: (1) expanding the scope of recovery and treatment of organic waste generated in each of their cantons, (2) providing their communities with recycling stations, (3) developing domestic composting marketing systems, (4) generating learning programs on circular economy issues for the implementation in households, and (5) expansion and improvement of the number of public-private partnerships that allow for better WM.

The study evidences a gap between what households require (external factors in the behavior model were the most influential) and what local governments provide (low rating of sorting techniques an intermediate satisfaction with the service), regardless of the degree of local governments’ political ability to handle waste or even the socioeconomic conditions of the household (one of the least influential variables of the model). In view of a non-homogeneous approach and the lack of a FW strategy in the country, it is derived from our study that a policy process that takes into account these findings and validates them, at least for the GMA population, can set the base for an effective FW reduction approach. In fact, the most recent Global WM Outlook 2024 suggests that behavioral-science-based interventions are supposed to be successful as they rely on the aspects that the end-users could adopt and engage into (UNEP, Citation2024). Such policy could part from an overall alignment of the main policy goal to SDG 12.3 target to reduce half the FW (UNEP, Citation2021) as starting point, achieved in time and following already existing methodologies to monitor (i.e. the Food Waste Index provided by UNEP). Nonetheless, strategic planning shall be at the core of the process, to begin with macro-targets like the one mentioned, also aligned with National goals of circular economy, bioeconomy, and decarbonization, and then mid-targets related to subthemes to be considered and timeframe development. For instance, a FW policy would probably require interlinked pillars or areas of attention: (a) awareness, communication, and education; (b) research, technology, and investment in FW collection and valorization alternatives; (c) measuring and monitoring, among others. For each of these areas, specific middle-level quantitative and qualitative targets, together with milestones that are evident to the administration but also to the population are required. From an integrated viewpoint, all the stages of (food) WM shall be addressed in this instrument, i.e. prevention, collection, treatment (Jain et al., Citation2018). Since the model and consulted literature evidence that the external factors provided in this case by the WM services of municipalities result in the most influential factor to reduce FW, alternatives to address the problem can be built from the already prioritized and mentioned projects from environmental managers of the local governments. Therefore, their independent priorities in WM facilities and technologies, together with composting or anaerobic digestion proposed projects shall be revised and placed at the top of a homogenized GMA policy as part of a further Action Plan to follow the policy and its strategy. Of course, every policy can face implementation limitations, such as budget, technical capacities, and public awareness. However, most of these constraints can be surpassed when alliances, communication, participatory processes, and FW and land-fill waste divert-alterative business cases are accurately presented, leaving a fertile substrate for politicians and decision-makers to act (Jain et al., Citation2018).

5. Conclusions

Considering the results of the study, it is necessary to address the lack of awareness and knowledge that exists in Costa Rican families of the GMA about the social, economic, and environmental consequences that are caused by FW, to improve the quality of life of people. Working in this aspect as part of local WM policies can include awareness both in households and at different levels of the Municipal governance of the impacts caused by inadequate habits, such as the lack of planning of the purchases, incorrect storage of the products and prioritization of WM elements at the municipal level. In addition, it is necessary to address the need for knowledge of FW-associated behaviors and MSW decisions from end-users, to tackle the problem from the public policymakers and implementers effectively.

Local governments are aware of the functions and need of policies aimed at reducing FW. However, most municipalities face challenges in investment, work strategies, and WM planning to penetrate the consumer’s mind and habits with the idea of reducing FW, especially in homes, to also match them with enabling municipal practices. Consumers comply with the mandates of local governments, and local governments are driven by the exportation of recyclable materials, which generate market potential and income for local governments. Nonetheless, cultural aspects influence consumer behavior and perceptions of the local governments.

Parting from the most relevant overall conclusion of the study, rooted at the significant influence of external factors in consumers FW behavior, it is important to consider that although different institutions oversee the role of local governments in Costa Rica, the work related to the recycling and management of organic waste (and particularly FW) that they give in the GMA is not equal. In consequence, there are numerous incipient, individual, and heterogeneous actions, which can be nurtured and scaled-up by a FW policy process aligned with the SDG target 12.3 and national as well as subnational goals. In this way, the mismatch of consumers’ behavior and its influencing factor regarding the service and alternatives provided by local governments can be considered.

Aspects that could be considered in future research is the time or availability of people due to their work role and how this can influence FW since this problem can also be related to the changing patterns of each person during the day or another period. In addition, it is recommended in forthcoming studies to consider the role of other stakeholders along the food supply chain, such as retailers and their practices (technology, campaigns, communication strategies, location, variety, among others), as part of an integrated food system. These alliances, together with some of the policy elements that we recommend, can trigger more efficient, contextualized, and behavioral science-based approaches to effectively tackle FW in the GMA of Costa Rica, and similar scenarios.

Author contribution

Mercedes Montero-Vega: 1. Conceptualization, 2. Data curation, 3. Formal analysis, 4. Funding acquisition, 5. Investigation, 6. Methodology, 7. Project administration, 8. Resourses, 9. Software, 10. Supervision, 11. Validation, 12. Visualization, 13. Writing-original draft and 14. Writing- review and editing. Laura Brenes-Peralta: 1. Conceptualization, 3. Formal analysis, 5. Investigation, 10. Supervision, 11. Validation, 12. Visualization, 13. Writing-original draft and 14. Writing- review and editing. Diayner Baltodano-Zúniga: 1. Conceptualization, 2. Data curation, 3. Formal analysis, 5. Investigation, 9. Software, 11. Validation, 12. Visualization, 13. Writing-original draft and 14. Writing- review and editing. Manuel Enrique García-Barquero: 5. Investigation, 6. Methodology, 8. Resourses, 11. Validation.

2.pdf

Download PDF (86 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the student assistants and municipality personnel who participated in this project. We deeply appreciate the support from the Research Department of Universidad de Costa Rica through the funding of project code C2354 (UN ENFOQUE BIOECONÓMICO PARA EL APROVECHAMIENTO DE LA PÉRDIDAS Y DESPERDICIOS DE ALIMENTOS), as well as for the support from the Consolidated Research Program of the Research Department of Tecnológico de Costa Rica.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [LBP], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mercedes Montero-Vega

Mercedes Montero-Vega, PhD in Environmental Economics and Rural Business Development, Professor of the Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness School of Universidad de Costa Rica. Research topics in food loss and waste, behavioral economics and bioeconomy.

Laura Patricia Brenes-Peralta

Laura Patricia Brenes-Peralta, PhD in Agricultural, Environmental and Food Science and Technology. Associate Professor and Researcher of the Agribusiness School of Tecnológico de Costa Rica. Research topics in food loss and waste, life cycle thinking and sustainable food systems.

Diayner Baltodano-Zúñiga

Diayner Baltodano-Zúñiga graduate in Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, instructor of the Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness School of Universidad de Costa Rica. Research topics in food loss and waste, and agricultural costing.

Manuel Enrique García-Barquero

Manuel Enrique García-Barquero posgraduate in Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, professor of the Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness School of Universidad de Costa Rica. Research topics in marketing and food loss and waste.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl, & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 1–16 SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer. (October 2, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ananda, J., Karunasena, G. G., Kansal, M., Mitsis, A., & Pearson, D. (2023). Quantifying the effects of food management routines on household food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 391, 136230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136230

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., Giménez, A., & Ares, G. (2019). Household food waste in an emerging country and the reasons why: Consumer’s own accounts and how it differs for target groups. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 145, 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.001

- Aydin, H., & Aydin, C. (2022). Investigating consumers’ food waste behaviors: An extended theory of planned behavior of Turkey sample. Cleaner Waste Systems, 3, 100036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clwas.2022.100036

- Barquero, M., Cifrian, E., Viguri, J. R., & Andrés, A. (2023). Influence of the methodological approaches adopted on the food waste generation ratios. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 190, 106872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.106872

- Bilska, B., Tomaszewska, M., & Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. (2019). Analysis of the Behaviors of Polish Consumers in Relation to Food Waste. Sustainability, 12(1), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010304

- Bolaños-Palmieri, C., Jiménez-Morales, M., Rojas-Vargas, J., Arguedas-Camacho, M., & Brenes-Peralta, L. (2021). Food loss and waste actions: Experiences of the Costa Rican food loss and waste reduction network. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 10(10), 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102358

- Campos-Matarrita, E. (2022). Modelo de gestión para el compost doméstico en el cantón de Belén de Heredia. Tecnológico de Costa Rica. Proyecto Final de Graduación para optar por el grado de Licenciatura en Ingeniería Ambiental. Cartago. https://repositoriotec.tec.ac.cr/handle/2238/14265.

- Cappellini, B. (2009). The sacrifice of re-use: The travels of leftovers and family relations. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 8(6), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.299

- Cappellini, B., & Parsons, E. (2012). Practising thrift at dinnertime: Mealtime leftovers, sacrifice and family membership. The Sociological Review, 60(2_suppl), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12041

- Chan, L., & Bishop, B. (2013). A moral basis for recycling: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 96–102." https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.010

- Chen, M.-F. (2022). Integrating the extended theory of planned behavior model and the food-related routines to explain food waste behavior. British Food Journal, 125(2), 645–661. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2021-0788

- Coste, M., Feiteira, F., & Condamine, P. (2021). Reducing food waste at the local level, Guidance for municipalities to reduce food waste within local food systems. Brussels. Zero Waste Europe & Slow Food. https://zerowastecities.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Guidance-on-food-waste-reduction-in-cities-EN.pdf. (December 10, 2023)

- DCC. (2020a). Contribución Nacionalmente Determinada de Costa Rica. Dirección de Cambio Climático. https://cambioclimatico.go.cr/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Contribucion-Nacionalmente-Determinada-de-Costa-Rica-2020-Version-Completa.pdf.

- DCC. (2020b). I Plan Nacional de Compostaje 2020-2050. Obtenido de Dirección Nacional de Cambio Climático. https://cambioclimatico.go.cr/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Plan-Nacional-de-Compostaje-2020-2050.pdf.

- Djekic, I., Miloradovic, Z., Djekic, S., & Tomasevic, I. (2019). Household food waste in Serbia – Attitudes, quantities and global warming potential. Journal of Cleaner Production, 229, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.400

- Dobernig, K., & Schanes, K. (2019). Domestic spaces and beyond: Consumer food waste in the context of shopping and storing routines. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(5), 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12527

- Ek, C., & Miliute-Plepiene, J. (2018). Behavioral spillovers from food-waste collection in Swedish municipalities. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 89, 168–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2018.01.004

- Evans, D., McMeekin, A., & Southerton, D. (2012). Sustainable consumption, behaviour change policies and theories of practice. The Habits of Consumption: COLLeGIUM: Studies across Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences, 12, 113–129. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/34226

- FAO. (2019). The state of food and agriculture: Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. https://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf.

- Fridahl, M., & Lehtveer, M. (2018). Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS): Global potential, investment preferences, and deployment barriers. Energy Research & Social Science, 42, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.03.019

- Ghinea, V. M., Cantaragiu, R. E., & Ghinea, M. (2020 FEED-Modeling the relationship between education and food waste [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, 14(1), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.2478/picbe-2020-0072

- Graham-Rowe, E., Jessop, D., & Sparks, P. (2015). Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 101, 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.05.020

- Grasso, A. C., Olthof, M. R., Boevé, A. J., Dooren, C. v., Lähteenmäki, L., & Brouwer, I. A. (2019). Socio-demographic predictors of food waste behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability, 11(12), 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123244

- Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., van Otterdijk, R., & Meybeck, R. (2011). Global food losses and food waste: extent, causes and prevention, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). https://www.fao.org/3/i2697e/i2697e.pdf.

- Hmimou, A., Kaicer, M., & El Kettani, Y. (2023). The effects of human capital and social capital on well-being using SEM: evidence from the Moroccan case. Quality & Quantity, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01794-6

- INEC. (2022). Encuesta Nacional de Hogares ENAHO 2022. https://inec.cr/estadisticas-fuentes/encuestas/encuesta-nacional-hogares (July 10, 2023).

- Jain, S., Newman, D., Cepeda-Máquez, R., & Zeller, K. (2018). Global Food Waste Management: an implementation guide for cities. World Biogass Association and Food, Waste, Waer and Waste Programme. https://www.worldbiogasassociation.org/food-waste-management-report/

- Janssens, K., Lambrechts, W., van Osch, A., & Semeijn, J. (2019). How consumer behavior in daily food provisioning affects food waste at household level in The Netherlands. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 8(10), 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8100428

- Margallo, M., Ziegler-Rodriguez, K., Vázquez-Rowe, I., Aldaco, R., Irabien, Á., & Kahhat, R. (2019). Enhancing waste management strategies in Latin America under a holistic environmental assessment perspective: A review for policy support. The Science of the Total Environment, 689, 1255–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.393

- Meyer, A. (2015). Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecological Economics, 116, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.018

- Ministerio de Salud. (2016). Plan Nacional para la Gestión Integral de Residuos. San José, Costa Rica ISBN 978-9977-62-166-1. https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/biblioteca-de-archivos-left/documentos-ministerio-de-salud/ministerio-de-salud/planes-y-politicas-institucionales/planes-institucionales/planes-planes-institucionales/714-plan-nacional-para-la-gestion-integral-de-residuos-2016-2021/file.

- Ministerio de Salud. (2023). Costa Rica se encamina hacia la circularidad de los residuos. Obtenido de Ministerio de Salud Noticias. https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/prensa/60-noticias-2023/1593-costa-rica-se-encamina-hacia-la-circularidad-de-los-residuos.

- MinSalud & MINAE. (2021). Plan de Acción para la Gestión Integral de Residuos Sólidos 2019-2025. San José. https://d1qqtien6gys07.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/plan_accion_gestion_integral_residuos_08042021.pdf.

- Montero Vega, M., García Barquero, M., & Sánchez Gómez, I. (2022). Conductas de pérdidas y desperdicios de alimentos de tres sectores en Costa Rica*. RIVAR (Santiago), 9(26), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.35588/rivar.v9i26.5589

- Montero Vega, M., García Barquero, M., Sánchez Gómez, J., & Mejia Valverde, K. (2023). ¿ de alimentos lácteos? Estudio de caso de la industria láctea de Costa Rica. Anales Científicos, 83(2), 149–159. Qué determina el desperdicio https://doi.org/10.21704/ac.v83i2.1848

- Muruganantham, G., & Bhakat, R. S. (2013). A review of impulse buying behavior. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 5(3), 12. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v5n3p149

- Nabi, N., Karunasena, G. G., & Pearson, D. (2021). Food waste in Australian households: Role of shopping habits and personal motivations. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1523–1533. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1963

- PEN. (2018). Tendencias y patrones del crecimiento urbano en la GMA, implicaciones sociales, económicas y ambientales y desafíos desde el Ordenamiento territorial. Informe del Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible 2018. Programa Estado de la Nación. CONARE. https://repositorio.conare.ac.cr/bitstream/handle/20.500.12337/2982/Tendencias_patrones_crecimiento_urbano_GMA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y%20.

- Rodriguez Frade, N., Brito De la Torre, J., & Bérriz Valle, R. (2021). Guía para la Gstión Integral de Residuos Sólidos Municipales. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-09/PADIT_Gu%C3%ADa%20para%20la%20gesti%C3%B3n%20integral%20de%20residuos%20s%C3%B3lidos%20municipales.pdf.

- Principato, L., Mattia, G., Di Leo, A., & Pratesi, C. A. (2021). The household wasteful behaviour framework: A systematic review of consumer food waste. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 641–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.07.010

- Schanes, K., Dobernig, K., & Gözet, B. (2018). Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.030

- SCIJ. (2023a). Ley para la Gestión Integral de Residuos no. 8839. Obtenido de Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica: https://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?param1=NRTC&nValor1=1&nValor2=68300&nValor3=83024&strTipM=TC.

- SCIJ. (2023b). Ley General de Salud N° 5395. Obtenido de Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica: http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?param1=NRTC&nValor1=1&nValor2=6581&nValor3=96425&strTipM=TC.

- Setti, M., Banchelli, F., Falasconi, L., Segrè, A., & Vittuari, M. (2018). Consumers’ food cycle and household waste. When behaviors matter. Journal of Cleaner Production, 185, 694–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.024

- Sheeran, P. (2011). Intention—behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792772143000003

- Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(6), 1273–1285. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282

- Stancu, V., Haugaard, P., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2016). Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite, 96, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.025

- Stancu, V., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2022). Consumer-related antecedents of food provisioning behaviors that promote food waste. Food Policy. 108, 102236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102236

- Stefan, V., van Herpen, E., Tudoran, A., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2013). Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Quality and Preference, 28(1), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.11.001

- Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

- Teigiserova, D. A., Hamelin, L., & Thomsen, M. (2020). Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. The Science of the Total Environment, 706, 136033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136033

- UNEP. (2015). Global Waste Management Outlook. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-waste-management-outlook.

- UNEP. (2021). Food Waste Index Report 2021. Obtenido de https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021.

- UNEP. (2024). Global Waste Management Outlook 2024: Beyond an age of waste: Turning Rubbish into a Resource. Nairobi. https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/44939

- United Nations. (2023). Análisis de avance en los indicadores de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible respecto a las metas globales de la Agenda 2030 en Costa Rica. https://ods.cr/sites/default/files/documentos/avance_ods_2023_-actualizacion.pdf.

- van der Werf, P., Seabrook, J., & Gil, J. (2018). The quantity of food waste in the garbage stream of southern Ontario, Canada households. PloS One, 13(6), e0198470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198470

- Visschers, V. H. M., Wickli, N., & Siegrist, M. (2016). Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.007

- Vittuari, M., Garcia Herrero, L., Masotti, M., Iori, E., Caldeira, C., Qian, Z., Bruns, H., van Herpen, E., Obersteiner, G., Kaptan, G., Liu, G., Mikkelsen, B. E., Swannell, R., Kasza, G., Nohlen, H., & Sala, S. (2023). How to reduce consumer food waste at household level: A literature review on drivers and levers for behavioural change. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 38, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.03.023

- Wahlen, S. (2011). The routinely forgotten routine character of domestic practices. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35(5), 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01022.x