Abstract

The study examines the potential of Zambia’s cattle industry as a solution to food insecurity, while also addressing obstacles such as climate change, disease outbreaks and limited technology adoption. Employing the desktop review study design and drawing on data from the 2022 Livestock Survey Report and the 2017/2018 fisheries and livestock census, augmented by a systematically conducted literature review encompassing 63 peer-reviewed articles, the study provides insights into the geographical dynamics, challenges and opportunities within Zambia’s cattle subsector. It identifies key factors influencing sustainable livestock production, including cattle management systems, environmental characteristics and socio-economic factors. Government policies, market dynamics and infrastructure development are highlighted as moderating factors shaping the viability of cattle enterprises. The study reveals notable variations in cattle populations across regions and identifies obstacles faced by smallholder farmers, including limited financing and regulatory burdens. Despite challenges, the study suggests that fostering sustainable cattle business models in Zambia is achievable through innovative strategies such as enhancing value propositions and improving market access. By addressing these challenges and seizing opportunities, Zambia can enhance its cattle industry, contributing to sustainable development, food security and economic prosperity.

Reviewing editor:

1. Introduction

Globally, food insecurity and poverty afflict numerous regions, with Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and Zambia in particular, being highly susceptible to these issues (Sibhatu & Qaim, Citation2018). The urgency of addressing poverty and food insecurity cannot be overemphasized and is underscored by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 2, which aim to eradicate all forms of poverty and achieve universal access to food. However, despite these endeavors, global estimates suggest a lack of progress, with around 690 million individuals, constituting 8.9% of the global population, continuing to endure hunger and malnutrition (Ng’ombe et al., Citation2023).

Recognizing the exponential growth of the world’s human population, research has indicated that as a nation’s population grows, its agricultural sector struggles to provide sustainable food (Chapoto & Subakanya, Citation2019; Mulenga et al., Citation2020). In the face of Zambia’s rapidly expanding population, exceeding 20 million individuals, the country grapples with the intricate challenge of sustaining its people, yet it is endowed with natural resources such as extensive pastures and waters that support agricultural growth and development (Zambia Statistics Agency, Citation2022). Despite the exposure to these resources, Zambia has, in extension, failed to exploit this opportunity to provide food for historically belligerent neighboring countries, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (African Financials, Citation2023; Mumba et al., Citation2018; Simuunza, Citation2022). What is more perplexing is that the provinces adjacent to these prospective markets have the lowest levels of food production.

Among various solutions that have the highest potential to contribute to the country’s food security, and ultimately poverty reduction, is livestock production (World in Data, Citation2022). Livestock, and specifically cattle, play a crucial role in the attainment of sustainable development goals as outlined in Zambia’s Vision 2030 and the eighth national development plan (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022). The World Bank (Citation2011) and Mumba et al. (Citation2018) also posited a harmonized stance that smallholder cattle business systems in Zambia represent a crucial component of the country’s agricultural sector, contributing significantly to food security, rural livelihoods and economic development.

FAO (Citation2019) and Mumba et al. (Citation2017) claimed that Zambia faces a deteriorating state of livestock and cattle farming, a predicament which is further exacerbated by a myriad of complex challenges, among them being climate change, animal disease outbreaks, production costs, human pandemics, geographical dynamics, heavy reliance on traditional practices and lack of technology. These challenges have been detrimental, for instance, Zambia’s lag in adopting advanced technologies misses out on the benefits of automation, animal traceability and sustainable farming methods (Daum et al., Citation2022; Wolfert et al., Citation2017). This further exacerbates Zambia’s inability to sustainably expand the cattle sector to her carrying capacity of between 12 to 15 million head of cattle (Chilala, Citation2015; World Bank, Citation2011).

While a considerable portion of the research on cattle business in Zambia has focused on the adverse consequences of climate change and the traditional practices of smallholder cattle farmers (Hamududu & Ngoma, Citation2020; Siankwilimba, Citation2019), the positive aspects that are crucial for the country, provinces, districts, camps and households, have received considerably less attention, even though these characteristics can present both opportunities and challenges for stakeholders involved in cattle production and marketing.

The geographical diversity of Zambia, characterized by distinct agro-ecological zones and landscapes, influences the production, marketing and profitability of smallholder cattle businesses. While some regions offer favorable conditions for cattle rearing and market access, others face constraints such as limited infrastructure, land degradation and climate variability. Although the Zambian government and other former and current cooperating partners have tried to encourage and assist the expansion of the cattle industry, the results have been cascading over a long period of time (Ministry of Finance & National Planning, Citation2022). Numerous studies attribute the lack of economic acumen of farmers to them, while others blame the unfavorable conditions that hinder the sector’s expansion—a setting characterized by frequent disease outbreaks and inadequate funding for the ministry of fisheries and livestock (Subakanya & Chapoto, Citation2020; Van Eenennaam et al., Citation2019).

An examination of the cattle industry’s comparative and competitive advantages, as well as its positive and negative aspects, on a broader scale, would encourage and motivate smallholder farmers and other stakeholders to enter the sector and mitigate the systemic risks that have impeded its growth for decades (González-Quintero et al., Citation2021). Additionally, the existing literature evaluations fail to examine the potential impact of the anticipated restructuring of the business climate on the sustainability of the cattle industry (Kalungu, Citation2023; Muma et al., Citation2009). This data is exceptionally beneficial in determining which interventions should be implemented in cattle enterprises to ensure that all stakeholders’ livelihoods are sustained.

Against this backdrop, this research aims to offer a comprehensive expert analysis of the business potential of the cattle industry in Zambia. A thorough professional examination of the business potential of the Zambian dairy and beef industries and their implications for the sector’s long-term viability and vitality is also presented in this study. The authors’ aim is to produce meaningful insights that can act as a compass for stakeholders and policymakers in their pursuit of improved livelihoods, sustainable food security and national economic prosperity by employing rigorous methodologies and drawing from extensive data sources.

2. Methodology

This study was conducted in Zambia, drawing upon two primary sources: the 2017–2018 Fisheries and Livestock Census and the 2022 Livestock and Fisheries Annual Report. These reports were produced through collaborative efforts between two wings of the Government of the Republic of Zambia, the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock and the Central Statistics Office (CSO). The Fisheries and Livestock Census for 2017/2018 and the annual Livestock and Fisheries survey for 2022 are recognised for their high-quality data, particularly regarding livestock and cattle production. They were executed with technical support and collaboration from various stakeholders, including the Zambia National Farmers Union, University of Zambia, the Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute and government entities.

The robust methodology employed in these surveys, along with the inclusion of nationally representative data, made them suitable for inclusion in this study. Both surveys utilised a stratified cluster sampling method, which ensured the enumeration of every household within the selected clusters. This approach contributed to the validity and reliability of the collected and analysed information. The selection of clusters was based on data obtained from livestock-raising households during the preceding 2010 Population and Housing Census.

Earlier reports by Odubote (Citation2022) and Simuunza (Citation2022) provided an overview of the census design, including details on the provincial administrative structure and agro-ecological regions (AER) of the country. More specific information on the methodological procedures can be found in the two summary reports published by the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock and Zambia Statistical Agency on their government website’s 2022 Livestock Survey Report (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022) and 2017/18 Livestock and Aquaculture Census Report (Zambia Statistics Agency, Citation2022).

The two reports provided data to fulfil the specific objectives around exploring and analysing the geographical opportunities of cattle farming in Zambia, based on the distribution and composition of livestock (cattle) across different regions, provinces and districts in Zambia. A special focus was on the Southern Province due to its esteemed status as the highest cattle producing province.

The procedures for gathering data from the public reports in the public domain was not sought as suggested and outlined in a previous publication by Odubote (Citation2020). However, for this study, only information relevant to cattle production was extracted. This included demographic details of households involved in cattle rearing, such as herd size, structure and dynamics, as well as aspects related to production systems, management practices (housing, feeding, water access), disease control and veterinary care, breed types, milk production and record-keeping. Excel was utilised to collect the data, verification, cleaning, organisation and safekeeping, and there after posted into the IBM SPSS statistics software for analysis (IBM Corp, Citation2015).

2.1. Data analysis

The collected data was analysed using basic descriptive statistics, following the procedures outlined in the IBM SPSS statistics software guide (IBM Corp, Citation2015). Both qualitative and quantitative methods were employed in the statistical analysis. Significance tests were conducted using one-way analysis of variance, with significance considered at a threshold of P < 0.01. The results were presented in tabular format, followed by producing graphs and charts for this report.

2.2. Secondary data collection techniques

To enhance the review, focusing attention on the objectives of challenges faced by the livestock subsector and sustainability business implications, the authors systematically conducted a literature review encompassing peer-reviewed articles sourced from reputable databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, PubMed, ResearchGate, Nature Springer and further articles sourced from grey databases. Of the 103 articles initially identified, 64 were selected for inclusion in this study. The review focused on peer reviewed available literature pertaining to aspects of ‘cattle business’, ‘livestock market development’, ‘smallholder farmers’, ‘sustainability and management systems’, among others. These specific terms were utilised to guide the literature search.

The inclusion criteria for articles were texts written in English, the official language of the nation’s researchers, while texts in languages such as French, Spanish and Portuguese were excluded. In addition to the main articles that met the search parameters, more articles were found by looking through the pertinent cross-references. Supplementary research on topics such as canines, honey, aquaculture, poultry, sheep, goats or fisheries was intentionally excluded to maintain a focused approach on the cattle business within the country of Zambia.

Overall, in order to give a thorough and nuanced picture of Zambia’s livestock production systems and its dynamics, the approach used in this study stresses the use of solid and diversified datasets, rigorous statistical analysis and graphical depiction. The careful use of this technique guarantees that the study’s conclusions are both practically and scientifically meaningful, supporting the overall objective of Zambia’s socioeconomic development and sustainable farming methods.

The integrated findings were further interpreted within the context of the thematic framework, elucidating the relationships between different factors that influence sustainability of the cattle business.

3. Results and discussions

In the subsequent findings, we delve into the geographic opportunities, challenges confronting cattle producers and the sustainability implications arising from these factors. Our analysis explores a spectrum of issues, paralleling the multifaceted approach adopted earlier. We investigate the diverse geographical landscapes and their potential for cattle farming, while concurrently scrutinizing the myriad challenges encountered by producers within these regions. Moreover, our examination extends towards deciphering the sustainability implications inherent in these geographical dynamics, addressing key issues such as resource utilization, environmental impact and resilience of the cattle production systems.

3.1. Geographical opportunities

As livestock, encompassing cattle, goats, pigs, sheep and village chickens, stand as a cornerstone in Zambia’s agricultural landscape, it permeates various levels, from provinces, districts and chiefdoms to camps, villages, commercial operations and households. Globally, data sets on the geographic distribution of livestock are essential for diverse applications in agricultural socioeconomics, food security, environmental impact assessment and epidemiology (Adesogan et al., Citation2020). Further, an evaluation of livestock distribution offers valuable insights into factors of influence such as climate suitability, natural resource availability, disease risk management, market access, agro-ecological zoning and policy development (Adesogan et al., 2020).

In 2022, Zambian smallholder farmers owned 94% (4,411,650) of the cattle, while commercial farmers hosted 6% (287,323) of the total national herd of 4,698,973 (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022).

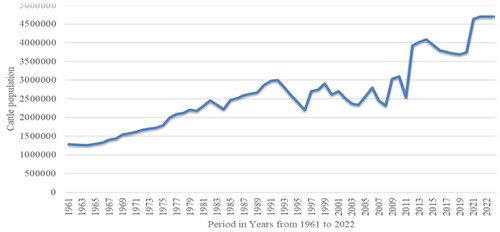

Before a deep dive into the regional dynamics, it is imperative to recognize the growth of the livestock sector over the years. Zambia has a significant cattle population, constituting 27.10% of the total cattle in Southern Africa (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022). Over the years, the cattle population in Zambia has experienced cumulative increases and decreases at various levels, from household to national levels (FAO, Citation2023a). The introduction of commercial ranching during the colonial era contributed to the growth of cattle production in Zambia, particularly in provinces like Southern, Lusaka and Central (Mulenga et al., Citation2020). While the cattle sector in Zambia has shown varying population trends, it has generally seen a steady increase over time ().

Figure 1. The cascading cattle growth and development in Zambia from 1961 to 2022 (FAO, Citation2023a; Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022).

The 2022 livestock census report underscores a marginal growth of 1.4% between 2021 and 2022, amounting to 65,551 cattle. Muchinga leads with a growth rate of 21.1%, followed by the Northern Province with 9.5%, Western Province with 9.58% and Luapula Province with 4.9%. In contrast, Lusaka Province records the most substantial reduction at 3.4%, while other provinces display negative growth. These changes underscore the dynamic nature of livestock management, shaped by various factors influencing growth rates. Nonetheless, the industry is focused on meeting the demands of domestic and international markets for meat and milk (FAO, Citation2022a).

3.1.1. The distribution of livestock (cattle) across different regions in Zambia

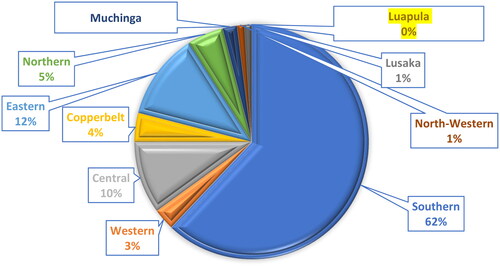

As revealed by the 2022 annual livestock survey report, the distribution of cattle exhibits noteworthy variations across Zambia’s provinces, meticulously presented in . The Southern Province takes the lead with 47.2% of the national total, followed by the Central Province at 16.7%, the Eastern Province at 15.3% and the Western Province at 10.3%. These figures underscore the substantial presence of cattle in drier and moderate rainfall regions, emphasizing the crucial role of provinces like Southern, Central, Lusaka, Eastern and Western in sustaining the livestock industry.

Table 1. Flows of cattle stocks per province (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022).

In stark contrast, the Northern Circuit, encompassing Luapula, Muchinga, the Northern Province and the North-western Province, accounts for a mere 6% of the national cattle population. The Northern Province, recording the highest within this circuit, has 104,760 cattle, while Luapula lags with the lowest count at 14,072 ().

3.1.2. Smallholder cattle distribution and composition across provinces

Analysing the composition of the smallholder cattle herd across regions, Wezi et al. (Citation2023) and African Financials (Citation2023) reveal a nuanced landscape driven by the unique needs and practices of farmers. For instance, the Northern Province, specifically the Mbala district, exhibits a higher proportion of oxen compared to cows and heifers, driven by the prevalent use of oxen for ploughing purposes.

The composition of the cattle herd also holds implications for the business models adopted by farmers, emphasizing the significance of cows, trained oxen, heifers, calves and bulls (). Effective breeding programs and considerations for the well-being and health of breeding females (cows and heifers) emerge as crucial elements for promoting the growth and sustainability of cattle herds according to Mwaanga and Pares-Casanova (Citation2017).

Table 2. Smallholder cattle herd configuration by province as of April 30, 2022 (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022).

further breaks down the smallholder household cattle herd configuration by province, delineating the percentage distribution of various cattle categories. Males, including trained and untrained oxen and bulls, constitute 48.5% of the total smallholder cattle population, while females, comprising cows and heifers, make up 51.5% calves, forming 50% of the national herd population, present a pivotal aspect of the cattle industry’s growth and development. A deeper dive into the analysis indicates that the Northern Province leads with the highest calving rate at 60%, while Lusaka Province records the lowest at 23.1%. These figures present a nuanced view of the potential for herd growth and expansion in different provinces of Zambia.

3.1.3. Attributable factors to the cattle population distribution

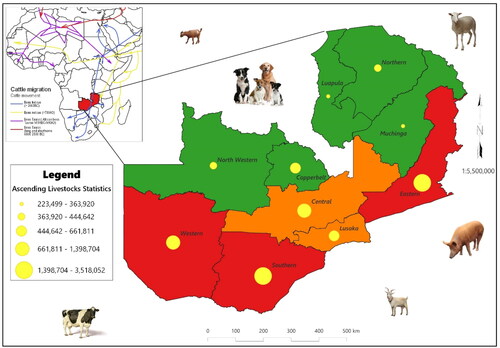

The distribution of cattle is intricately tied to Zambia’s agro-ecological zones—Zone I covering the southern and western regions, Zone II central regions and Zone III the far north (Khanal & Thapa, Citation2023). Zone I, characterized by low and irregular rainfall, emerges as the hub of livestock production, while Zone II provides conducive conditions for both livestock and crop agriculture. Zone III, experiencing heavy precipitation, grapples with challenges like soil erosion. These agroecological dynamics significantly shape the cattle industry and affiliated businesses by influencing pasture availability, water resources and agricultural potential in different regions (Wezi et al., Citation2023). This intricate relationship has led to the population dynamics maintaining a similar pattern overtime. , adapted from the 2019 Zambian livestock census illustrates Zambia’s map, meticulously divided into ten provinces, portraying the widespread distribution of close to 4 million herds of cattle across the nation. This visual representation serves as a foundation for understanding the dynamic interplay between the national livestock population and agroecological dynamics (Daum et al., Citation2022; Wolfert et al., Citation2017).

Taking an agroecological approach, as advocated by Khanal and Thapa (Citation2023), proves pivotal for promoting agricultural sustainability, food sovereignty and a circular economy. The distribution of cattle, while pivotal for economic sustenance, prompts consideration of environmental impacts. Grazing, a fundamental aspect of livestock management, exerts discernible effects on soil microbial communities, soil carbon content and enzyme activity. A meta-analysis by Xu et al. (Citation2023) discerned that grazing initially decreased soil organic carbon content and enzyme activities in the topsoil but exhibited a positive correlation with increased microbial biomass, enzyme activity and soil organic carbon over time. Managing grazing intensity and duration emerges as a critical factor for maintaining a delicate equilibrium between livestock grazing and soil health.

On a global scale, the distribution of livestock hinges on multifaceted factors, ranging from market proximity and animal feed availability to animal health services and processing facilities. Bai et al. (Citation2022) emphasize the efficiency gains, cost reductions and minimized transportation distances achieved by concentrating livestock production near markets. Notably, local demand, gauged by human population and gross domestic product, emerges as a pivotal factor influencing livestock production (Kalungu, Citation2023; Muma et al., Citation2009). River intensity, too, exhibits a positive correlation with cattle density, suggesting the contributory role of proximity to rivers in shaping livestock distribution (Sibhatu & Qaim, Citation2018). Additionally, also illustrates how, on the African map, cattle migration routes and domestication centres (Mwai et al., Citation2015) have historically and presently affected the opportunities and constraints associated with cattle (breed and type) growth and density in many nations, including Zambia’s ecological zones and ethnicity. Mwai et al. (Citation2015) submitted that the history of cattle is extremely complicated, and although there is ongoing discussion over some of its events, it is undeniable that the population of cattle has changed significantly over time, globally, and in Zambia. From the purest Bos Taurus to the almost pure Bos Indicus, the cattle population is currently a patchwork of genetic and ecological diversity (Mwai et al., Citation2015).

Understanding the myriad of factors influencing livestock distribution assumes importance for informed decision-making and strategic optimization of livestock production and distribution systems (Bai et al., Citation2022). By embracing an agroecological approach and factoring in environmental considerations, market proximity and local demand, the promotion of sustainable livestock production becomes a realizable goal (Ng’ombe et al., Citation2023).

3.1.4. District cattle distribution dynamics and business opportunities in Zambia

While it remains insightful to review cattle statistics at provincial level in Zambia, districts wield substantial influence over the livestock and cattle industry, with the government designating livestock and fisheries coordinators to oversee district management. A meticulous analysis of the 2017/2018 livestock and fisheries census report sheds light on the districts hosting the highest cattle populations within each province.

The top 40 districts (four from each province) constituting nearly 70% of the national cattle population (3,474,095), collectively amount to 2,438,974 cattle, as illustrated in . Notably, the Southern Province retained the largest share at 27%, with standout districts such as Monze and Itezhi-Tezhi leading the tally. This was only followed by districts in the Central and Eastern provinces with each province retaining 12%. Although it is vital to acknowledge that there are additional districts not represented in the table that also contribute to the overall cattle numbers within their respective provinces, when interpreting provincial cattle statistics, it is imperative to recognize that the mentioned districts significantly contribute to the overall cattle population within their respective provinces. For instance, the four districts of Luapula Province represent 99% of the total provincial cattle statistics, the four from Northern Province contribute 96% and the Western Province contribute 53% of their respective Province.

Table 3. The top 40 cattle-producing districts in Zambia’s ten (10) Provinces.

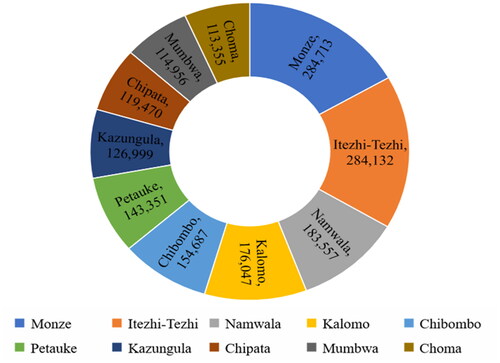

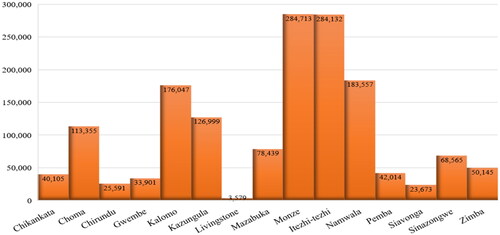

The distribution of cattle herds in Zambia’s top 10 districts, based on the 2017–2018 livestock census, is visually represented in . These districts collectively accounted for 1,701,267 cattle heads, constituting 49% of the total national cattle population. Monze led with 284,713 livestock, followed closely by Itezhi-Tezhi with 284,132, Namwala with 183,557, Kalomo with 176,047 and Choma with the lowest count. Notably, six of these districts are situated in the Southern Province, contributing a significant 69% to the combined provincial cattle population.

Areas with a higher concentration of cattle are more likely to witness increased business transactions. On the other hand, farmers may migrate to less densely populated regions with sufficient rainfall. As Zambia aspires to grow the cattle herd to 5.7 million by 2026, much of the growth is expected to come from the northern circuit, owing to the availability of necessary natural resource. Positive as the development will be, it is likely to present challenges related with impacting traditional crops grown in the region such as cassava as it is not protected from cattle destruction resulting in a negative impact on the economies of the residents. A further concern relates to drying of water reservoirs. Cattle cause siltation and increase mud in water reservoirs (dams) which are prominently fish farming systems on which the residents depend.

Comprehensive studies by Mumba et al. (Citation2017) and Chilala (Citation2015) on the Monze district delve into livestock system dynamics and disease prevalence, revealing the resilience of Monze farmers despite economic challenges and disease risks. Moreover, other research notes the presence of input providers at the district level in these key districts (MOFL & ZAMSTAT, Citation2020).

Investing in these top ten districts holds paramount importance for input and service suppliers, including offtake markets in Zambia, given their pivotal role in the national cattle distribution dynamics.

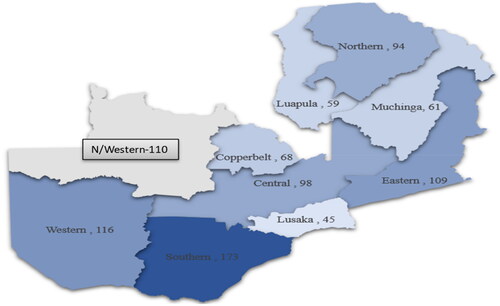

Studies also demonstrate the importance of veterinary camps, the smallest management units in the livestock industry, despite the fact that districts offer a wealth of opportunities (Mumba et al., Citation2018). The Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock in Zambia, specifically the Department of Veterinary Services, has the authority to control and manage the diseases of national economic importance from provincial, districts upto a camp level and vice versa (Kalungu, Citation2023; MOFL & ZAMSTAT, Citation2020). This authority not only permeates the broader national landscape but also trickles down to the grassroots level where farmers are situated, notably within veterinary camps. The establishment of veterinary camps in the region has emerged as a highly effective strategy to actively involve smallholder farmers in livestock production (Mumba et al., Citation2018). These camps, overseen by resident veterinary assistants while in some cases the livestock assistant and operating under the guidance of the District Veterinary Office (DVO) and district livestock officers, serve as the grassroots administrative offices in each district (African Financials, Citation2023; Mumba et al., Citation2018). As reported by the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, the country boasts a total of 933 veterinary camps spread across Zambia (). These veterinary camps play an indispensable role in the broader livestock industry, significantly contributing to food security, nutritional well-being and income generation within the communities.

3.1.5. Southern Province and cattle business opportunity dynamics

The Southern Province of Zambia emerges as a pivotal region in agriculture and diverse economic activities, hosting six of the top ten cattle-producing districts in the country, as depicted in . Cattle constitute 48% of the livestock population in the province, closely followed by goats (44%), pigs (6%) and sheep (2%). Despite a slight decrease from 2,223,397 in 2021 to 2,216,076 in 2022, the province boasts various cattle breeds and a higher concentration of crossbreeds compared to other provinces.

Within the Southern Province, there are 301 commercial farmers raising 119,992 cattle, averaging 339 cattle per farmer and 146,450 smallholder farmers contributing to the 2,096,086 cattle population, with an average of 14 cattle per family. Furthermore, among other provinces, the Southern Province takes the lead with the number of veterinary camps (173), constituting 19% of the total, followed by the Western Province with 116 (12%), the North-Western Province with 110 (12%), the Eastern Province with 109 (12%) and Lusaka with 45 (5%) camps.

Vulnerable to climate change impacts, the Southern Province is identified as a climate change hotspot. A corridor along the rail line and main road, houses most commercial farmers, while smallholder farmers are scattered in the hinterlands. This corridor serves as a commercial hub supplying the national food basket and supporting smallholder farmers with improved genetics and technologies.

Monze and Itezhi-Tezhi, followed by Namwala and Kalomo, dominate the cattle population distribution, with Livingstone recording the lowest at 3,570 animals (). Investors and input suppliers stand to gain from the substantial livestock population in districts within the Southern Province, underscoring the region’s potential for robust economic opportunities in the cattle business.

Figure 5. Cattle population distribution for Southern Province (Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022).

3.2. Challenges in smallholder cattle business systems

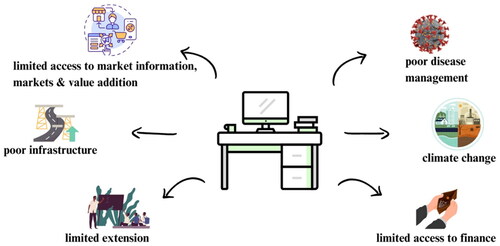

Despite Zambia having suitable agro-ecological zones for livestock production, the cattle density is relatively lower than neighboring countries like Zimbabwe and Kenya (Ministry of Finance & National Planning, Citation2022; World Bank, Citation2012). The growth of the livestock sector in Zambia is influenced by various complex challenges that require a multifaceted approach (Ng’ombe et al., Citation2023). The sector operates within complex systems involving production systems, input supply markets, aggregation systems, transport business systems, processor market systems and consumption market systems (Odubote, Citation2022; Simuunza, Citation2022). The dynamics of the livestock and cattle sectors are further influenced by factors at various levels, from provinces to households and the interrelationships between commercial and smallholder farmers, crucial for the growth of the smallholder sector (Mumba et al., Citation2018; Odubote, Citation2022).

Some of the major challenges faced by the livestock industry in Zambia at various levels, include limited sector financing, regulatory burdens, external shocks and market structure issues (Anderson et al., Citation2023; MCTI, Citation2022). These challenges contribute to risks of food insecurity, hunger, malnutrition, livelihood disruptions, increased poverty and limited opportunities for marginalized populations (Siankwilimba et al., Citation2023a).

3.2.1. Inadequate funding of cattle sector

The Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries has faced challenges with low budget funding and delays in releasing funds. This has led to insufficient resources for planned activities. One notable impact is the potential disconnection between research institutes and extension officers. This disconnect leads to limited accessibility to information, a consequence of inadequate funding. contrasts the 2022 budget allocations with the actual releases by September of that year. It reveals the percentage of funds released for each MFL program, shedding light on the financial execution.

Table 4. Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock (MFL) - 2022 allocations contrasted with releases.

Despite the outlined allocations and releases, it’s notable that Zambia’s national budget for the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries has consistently fallen below the recommended 10% set by the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) (Ministry of Finance & National Planning, Citation2022). This program, aligned with the goals of the African Union, seeks a 10% allocation to agriculture to achieve a 6% annual agricultural growth rate. Unfortunately, Zambia’s budget reports from 2012 to 2020 indicate a consistent deviation from this framework, as reported by the Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute (IAPRI) (Mulenga et al., Citation2020).

3.2.2. Market failures

Market failures in the livestock industry may also result from inefficiencies and imbalances between demand and supply (Todaro & Smith, Citation2015). According to Todaro and Smith (Citation2015), market structure significantly influences market dynamics and performance. Understanding market structure is essential for identifying market failures and developing appropriate interventions as shown in . Promoting and branding livestock and livestock products has also been effective in accessing structured markets (Deku et al., Citation2022). However, Padela et al. (Citation2023) discovered that smallholder farmers often lack branding for their livestock and products, hindering consumer consumption, growth, competition and survival.

3.2.3. Climate change and livestock business

Challenges brought about by climate change, an active force of influence on the viability of the livestock subsector, cannot be overlooked. With only seven years remaining until the nation’s eighth national development plan and Zambia Vision 2030 are realized, climate change complexity is a formidable obstacle to the realization of the livestock production potential as well as the development goals (Siankwilimba, Citation2019). Each year, in addition to the threat of animal diseases, the cattle industry faces anticipated droughts and floods, making it unattractive to potential rural investors (Ngoma et al., Citation2021).

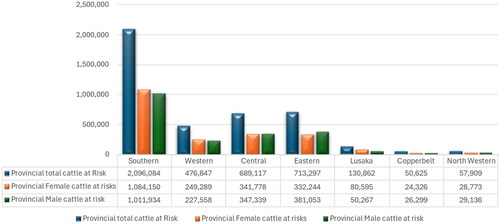

Zambia is currently faced with a crisis and many risk factors remain. In Zambia, it has recently been acknowledged that climate change may be a source of systemic risk and the livestock production system is likely to experience shocks from it in 2024 and beyond (Ngoma et al., Citation2023). Following the prolonged absence of rain in most parts of the country during the rainy season, leading to drastic losses of crop and reduced water levels in natural bodies and likely reduced livestock prices, the Central Government was prompted to declare a state of national disaster and emergency. This situation will directly impact livestock production negatively, especially on pasture and water points. Results show that of the total smallholder cattle population of 4,411,650, about 93% (4,106,207) of it is located in the drought-affected provinces (Southern, Central, Western, Lusaka and Eastern Provinces), likely to be negatively and significantly affected in 2024. depicts the number of animals from the affected areas prone to numerous risks.

Figure 7. Selected provinces that were declared drought-risk and an emergency by the president of Zambia and the cattle population by sex orientation.

It is expected that most farmers will likely sell their animals to mitigate the food crisis, of which the higher likelihood is for the sale of male animals (steers, oxen and some bulls). However, due to limited pasture, most female animals that will remain, especially the calves and lactating ones are likely to experience heavy stress and to some extent die of starvation. Those that survive the effects of drought will still be malnourished by the close of the season and their calves stunted (Ng’ombe et al., Citation2023).

Curcio et al. (Citation2023) argue that physical and transition risks are known to be closely related and to be a significant source of systemic risk when they result in losses for financial intermediaries, a breakdown in the operation of the financial markets and abrupt spikes in the volatility of major asset classes, all of which have an impact on the real economy affecting farmers. Curcio et al. (2023) advanced that the financial markets and institutions are intertwined, second round/indirect equity losses and self-reinforcing feedback loops might readily magnify the effects of climate-related risks. Therefore, evidence of a significant relationship between some extreme weather events and financial systemic risk supports the need for appropriate policies to be adopted in order to counteract the increase in the likelihood and severity of such disasters (Ngoma et al.,Citation2023). It also emphasizes the need to successfully integrate the risk resulting from these events into the risk management procedures of financial intermediaries and financial supervisors.

3.2.4. Livestock production systems

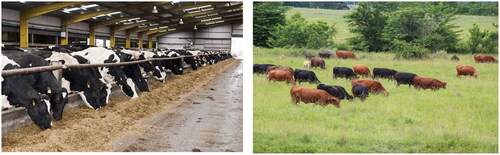

As earlier stated, the production of livestock in Zambia is predominantly based on extensive grazing systems, mostly associated with smallholder producers and intensive livestock farming associated with commercial producers, with a moderate level of mixed crop-livestock systems (Bai & Cotrufo, Citation2022; Nkonki-Mandleni et al., Citation2019) (). While this kind of production system suits beef cattle, it is also found in the smallholder dairy sector, making it one of the systemic challenges to the growth of the dairy sector in Zambia (Odubote et al., Citation2023; Siankwilimba et al., Citation2023b).

Figure 8. Contrast between intensive livestock feeding system and smallholder farmers associated extensive grazing depending on natural veld.

Further challenges are depicted in .

Generally, addressing these challenges requires concerted efforts from various stakeholders, including the government, farmer organizations and supporting institutions. Improving the regulatory environment, enhancing access to inputs and markets, promoting value addition and providing targeted support to smallholder farmers can help unlock the full potential of the livestock industry in Zambia and create opportunities for inclusive and sustainable growth. Further, in light of the urgent global challenges, such as the Russia-Ukraine crisis, climate change, food system transformation becomes crucial. This transformation is vital not only for Africa’s overall development but also for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to sustainability, resilience and zero hunger by 2030 (Siankwilimba et al., Citation2023a).

3.3. Sustainable cattle business implications

Fostering a sustainable cattle business in Zambia entails being conscious of several factors of influence in the livestock subsector. Some of the key factors arising from the study are as follows:

3.3.1. Customer segmentation and value add in smallholder cattle farming business

In the realm of business, as highlighted by Muehlhausen (Citation2013), the concept of business offering stands out as a distinguishing factor among various business players. This encapsulates the dual aspects of business attractiveness and a unique value proposition, both of which are pivotal for achieving effective business differentiation. When we delve into the specific landscape of the livestock and cattle market in Zambia, the definition of market attractiveness takes shape for smallholder farmers (Odubote et al., Citation2023). For these farmers, market attractiveness revolves around the specific niches, industries, markets or customer segments they target to propel their businesses to success.

In their primary focus on the local market, these smallholder farmers aim to deliver affordable beef and dairy products that cater to the basic needs of the population (Odubote et al., Citation2023). However, there seems to be a notable gap in their emphasis on targeting niche or high-value customer segments, such as the organic or premium markets. By tapping into these segments, there lies the potential for higher profits and the creation of additional growth opportunities.

Despite the global demand for beef and dairy, penetrating this broader market remains a challenge for smallholder farmers in Zambia, compounded by various complex factors, including a lack of innovation and entrepreneurship skills, unfavorable international and domestic policies, and notably, the occurrence of disease outbreaks (Odubote et al., Citation2023).

As elucidated by Mbithi et al. (Citation2016) the accessible market for a good or service is quantified as the total addressable market share (TAM). Smallholder farmers in recent times have grappled with challenges stemming from the absence of a unique value proposition. This proposition refers to the distinctive benefits they offer to customers that extend beyond the cattle and products they sell. In response to this landscape, input suppliers have stepped in by providing enhanced extension services alongside the sale of drugs and medicines to farmers.

This innovative approach represents a shift towards offering added value, where the benefits of vaccinating animals outweigh merely selling vaccines to farmers. This holistic approach not only contributes to the health and well-being of the animals but also aligns with the broader welfare of the farmers themselves. In navigating the intricate dynamics of the livestock and cattle market, smallholder farmers stand to gain by embracing innovative strategies that enhance their unique value propositions and open doors to untapped markets.

3.3.2. Customer relationships

Smallholder cattle farmers in Zambia typically have limited customer relationships beyond transactional interactions. Research by Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee (Citation2018) suggests that smallholder farmers often sell unpackaged products and services, which can make their business less attractive in the value chain. However, there is an opportunity for these farmers to strengthen their connections with customers by understanding their preferences, providing consistent quality and engaging in customer education and feedback initiatives (Hou et al., Citation2021; Orhan, Citation2018). By developing brand loyalty and customer trust, smallholder farmers can enhance their long-term success and ensure sustainability (Siankwilimba et al., Citation2022).

3.3.3. Markets

Distribution channels used by smallholder cattle farmers in Zambia often involve direct sales at local markets or through middlemen (Lubungu, Citation2016). However, it is difficult to access formal markets, such as supermarkets or export channels, due to limitations in infrastructure, transportation and meeting quality and safety standards. Improving market access and exploring alternative distribution channels could enhance their reach and profitability (Sibhatu & Qaim, Citation2018). Yet due to limited reach by processors and input suppliers, the systems has allowed and developed an aggregator business models (Siankwilimba et al., Citation2023a).

3.3.4. Key activities driving the smallholder farming business

Mumba et al. (Citation2018) shed light on the multifaceted engagement of smallholder cattle farmers in Zambia, encompassing activities ranging from animal husbandry and breeding to feeding, disease control and marketing. Despite this involvement, there exists a palpable need for advancements in adopting modern farming techniques, enhancing breeding programs, improving animal health management and implementing effective marketing strategies. Recognizing the identified challenges of a shortage of extension staff and inadequate infrastructure, as pinpointed by the Ministry of Finance and National Planning (Citation2022), addressing these issues requires comprehensive measures, with a primary focus on providing training and capacity-building initiatives.

In emphasizing the importance of understanding the activities and practices of traditional cattle farmers, Mumba et al. (Citation2018) stress the need to scrutinize practices that deviate from traditional management approaches. This comprehensive understanding becomes pivotal in developing long-term solutions to the intricate challenges faced by the cattle industry in Zambia and on a global scale. The study proposes that policymakers and stakeholders within the beef value chain should formulate well-informed policies and interventions that take these differences into account, thereby enhancing the productivity of the traditional cattle sub-sector.

3.3.5. Key resources

Smallholder cattle farmers in Zambia confront a myriad of challenges stemming from restricted access to pivotal resources such as land, capital, infrastructure and technical knowledge. Fostering productivity and bolstering competitiveness necessitate targeted interventions to enhance access to financing, veterinary services, extension support and infrastructure development (Vandome, Citation2023).

In light of these complex challenges, a concerted effort aimed at improving access to crucial resources, encompassing finance, veterinary services, extension support and secure land tenure, is imperative. Such initiatives are indispensable for fostering the development and sustainability of smallholder cattle farming in Zambia.

3.3.6 Cost structure

The revenue streams for smallholder cattle farmers in Zambia heavily rely on direct sales of live animals, slaughter and selling meat and milk in local markets. However, there exists a significant lack of diversification in revenue streams, such as value-added processing, branded products or export opportunities. This limitation hampers their ability to capture additional value from their cattle and maximize their income potential, making monetization a complex factor in sales performance against profit modelling.

The cost structure of smallholder cattle farming in Zambia is influenced by factors such as animal feed, veterinary services, transportation and market access. Limited economies of scale, coupled with challenges in resource availability and management, contribute to relatively higher production costs. Exploring cost-effective solutions, such as shared facilities, cooperative models and access to affordable inputs, could help improve cost efficiency.

According to , the Southern Province recorded the highest number of live cattle sales at the national level, with 118,965 live cattle sales among households and 14,108 sales for commercial establishments. In contrast, other provinces in Zambia had 123,693 live cattle sales for households and 18,889 sales for establishments, contributing to a nationwide total of 242,658 live cattle sales for households and 32,997 sales for establishments.

Table 5. Sales of Live Cattle in Households and Establishments (1st May 2022 - 30th April 2022).

3.3.7. Factors interplay (environmental, demographic, socio-economic and regulatory)

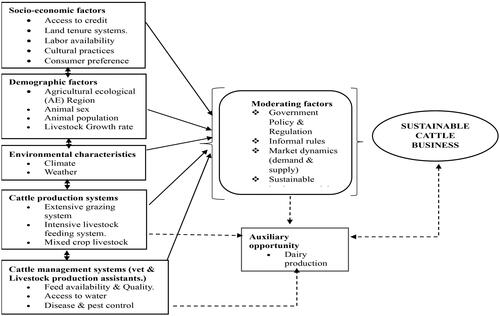

The conceptual framework in further depicts five key factors, namely, cattle management systems, environmental characteristics, demographic factors, cattle production systems and socio-economic factors, which are believed to influence a sustainable livestock production system and have implications for business sustainability. The conceptual framework suggests that moderating factors such as informal rules, market dynamics, sustainable business models, infrastructure and technology are the key to stimulating sustainable cattle business systems.

According to research by Ngoma et al. (Citation2021), Khanal and Thapa (Citation2023) and Xu et al. (Citation2023), agroecological zones, climate and weather all affect the availability of resources like pasture and water, and they can also have a positive or negative impact on the spread of illnesses and pandemics. While Mwaanga and Pares-Casanova (Citation2017) contend that environmental factors impact demographic factors, genetics, animal population, animal sex and growth rate are all influenced by demographic factors. Therefore, breeding programs that target desirable qualities like growth rate, feed efficiency and disease resistance contribute to the sustainability and profitability of the cattle industry, as stated by Odubote et al. (Citation2023) and Mwaanga and Pares-Casanova (Citation2017).

According to a study by Todaro and Smith (Citation2015), social and economic variables are necessary for sustainable cattle rearing. Todaro and Smith therefore noted that socioeconomic issues can also affect the cattle sub-sector’s viability. These elements include labor availability, land tenure systems, cultural norms and access to credit for capital injection (Vandome, Citation2023). According to Wen and Chen (Citation2023), changes in input costs, market demand and competition all have an impact on supply and demand dynamics, which are important social economic elements that affect production decisions, pricing strategies and market positioning.

According to Mutyasira (Citation2023), the availability of transportation networks, processing facilities, veterinary services and marketing channels all have an impact on infrastructure development, which in turn affects the efficacy, competitiveness and profitability of cattle operations. Varied business models, such as contract farming agreements, cooperative organizations and vertically integrated businesses, are believed to offer different benefits and challenges and infrastructure development is seen to stimulate and support these models for various actors (Szromek et al., Citation2021).

Numerous other characteristics, like milk production, are also impacted by these circumstances according to Odubote et al. (Citation2023). For example, having access to high-quality feed and water sources, a suitable climate, appropriate veterinary care and efficient milking equipment are all necessary for optimal milk output and profitability in dairy enterprises. The market’s demand for dairy products, government policies and support initiatives pertaining to the dairy industry and the infrastructure for their processing and transportation all have a significant influence on the configuration of the dairy production landscape.

All things considered, as the conceptual framework of this study indicates, the viability of a country’s cattle production is influenced by a complex interplay of biological, environmental, economic, social and regulatory elements. Sustainable livestock production requires a careful evaluation of these factors as well as the application of integrated management techniques that promote productivity, resilience and profitability (Adesogan et al., 2020). According to the conceptual framework, development that satisfies current needs without jeopardizing the capacity of future generations of consumers and cattle farmers to satisfy their own needs is the basis for sustainable development. Therefore, the framework is a supplemental guide to the study based on sustainable cattle implications.

4. Auxiliary opportunities (the dairy industry)

The livestock subsector in Zambia plays a crucial role in the country’s dairy industry, contributing significantly to food security and nutrition. Milk production is produced by both smallholder and commercial livestock farmers, with smallholder households producing a total of 37,906,803 litres of milk, while commercial farmers generated 51,981,804 litres. However, smallholder dairy productivity is deficient compared to emergent and commercial producers, highlighting potential for improvement.

The Southern Province contributes the highest milk production at an average of 62.4%, followed by the Eastern Province. The province of Luapula reported the lowest milk production, where there are hardly any dairy animals ().

Figure 11. Milk production and distribution according to each province in Zambia (MOFL and ZAMSTAT, Citation2020; Zambia Statistics Agency & Ministry of Fisheries & Livestock, Citation2022).

The Dairy Produce Board of Zambia, responsible for overseeing the dairy industry, ceased operations in the late 1980s and its assets were sold during the liberalization and privatization period (Vandome, Citation2023). Parmalat, the new owner, currently manages milk production from both large-scale and small-scale farmers through cooperative business models.

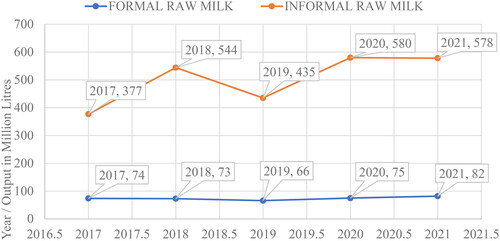

Despite the significant increase in dairy production by both smallholder and commercial producers, the product is mostly sold on the informal market (). A study by Mumba et al. (Citation2013) revealed that in selected traditional cattle-keeping regions of Zambia, there were 1,162,645 traditional cattle owned by 116,265 households, generating approximately 57.5 million litres of milk annually. While 3.7 million litres were sold to the formal market, an estimated $12 million was generated through sales in the informal market. Bringing all the milk into the formal sector was suggested to enhance the sustainability of the dairy business, with a projected monetary value of $27.6 million annually among rural households in the research locations.

Per capita milk consumption in Zambia remains low, with Zambians consuming only 18 to 22 litres per person per year, significantly below the recommended level of 200 litres per person per year by WHO and FAO (FAO, Citation2022a, FAO, Citation2023b). Under the Eighth National Development Plan (8NDP), the Zambian government aims to increase milk production and per capita consumption.

Challenges in the dairy industry include limited access to commercial markets and inadequate information, leading to high disease rates among the flock, mortality, poor quality and standards and Zambia ranking lowest in raw milk pricing despite its expansive grazing lands. To fully tap into the potential for dairy industry expansion in Zambia, harnessing the expansive grazing lands, additional considerations are vital, including disease prevention and control, access to high-quality inputs, improved market accessibility, affordable credit options, a comprehensive rural road network and electric power infrastructure.

5. Acknowledgment of limitations

In this article, our main goal was to thoroughly analyze the business opportunities available to smallholder farmers in the Zambian cattle sector. However, it is important to acknowledge the potential limitation of publication bias. The analysis heavily relied on reliable sources and peer-reviewed literature, which may have overlooked valuable insights from industry reports, unpublished data and non-peer-reviewed sources. Additionally, the focus was limited to English-language publications, possibly missing out on important studies in other languages that could have contributed more to the analysis. To enhance future research, expanding the inclusion criteria could be beneficial, reducing the impact of publication bias and improving the overall depth of the analysis.

6. Policy implications

Based on the findings of this article, policymakers might consider encouraging collaboration between corporate institutions, commercial farmers and cattle farmers, leveraging the effective approaches of commercial farmers to support smallholder farmers. For instance, implementing tax incentives for commercial farmers collaborating with smallholders to provide tailored business services could significantly enhance the accessibility and sustainability of agricultural markets for these businesses. Furthermore, policymakers can explore the establishment of a dedicated fund aimed at supporting the adoption of environmentally friendly technologies in the cattle industry, especially among smallholder farmers. This fund could offer grants or low-interest loans to financial institutions committed to providing sustainable financial services to smallholders, fostering innovation and inclusivity in banking practices.

7. Conclusion

The exploration of smallholder cattle business systems in Zambia has provided valuable insights into the geographical opportunities, challenges and business sustainability implications within the sector. Drawing on data from the 2017/2018 and 2022 livestock and fisheries census reports, as well as comprehensive peer reviewed papers, this study has shed light on the complex dynamics shaping smallholder cattle farming across diverse regions of Zambia.

The findings underscore the importance of recognizing and harnessing geographical opportunities for smallholder cattle farmers. Abundant grazing resources, favorable agro-ecological conditions and proximity to markets present significant opportunities for enhancing the productivity, profitability and resilience of smallholder cattle business systems in Zambia. Leveraging these opportunities through targeted interventions and supportive policies can unlock the full potential of the smallholder cattle sector, contributing to rural livelihoods, food security and economic development.

However, the study also highlights the formidable challenges facing smallholder cattle farmers in Zambia, particularly in the realm of geographical constraints. Land degradation, climate variability and limited infrastructure pose significant obstacles to sustainable cattle farming practices and market participation. Addressing these challenges requires concerted efforts from policymakers, development practitioners and stakeholders to implement sustainable land management practices, climate-smart agriculture interventions and infrastructure development initiatives.

Furthermore, the implications for business sustainability underscore the need for holistic approaches that prioritize the integration of smallholder farmers into formal markets, mitigate food and income loss and enhance environmental resilience. Sustainable market access, value chain development and capacity-building initiatives are essential for strengthening the resilience and livelihoods of smallholder cattle farmers, ensuring their long-term sustainability and contributing to poverty alleviation and rural development in Zambia.

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide a foundation for informed decision-making and action to support the growth and development of smallholder cattle business systems in Zambia. By addressing geographical challenges, leveraging opportunities and promoting sustainable practices, stakeholders can foster a more resilient, inclusive and sustainable smallholder cattle sector, contributing to the overall well-being and prosperity of rural communities in Zambia.

Authors’ contribution

Enock Siankwilimba: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Data curation, Validation, Resources, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Chisoni Mumba and Bernard Mudenda Hang’ombe: Writing—review and editing, Validation, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis

Ethical approval

Ethical Clearance was sought from the University of Zambia-Directorate of Research and Graduate Studies—Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSSREC). Ethical clearance issue number REF. HSSREC-20-SEP-005.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Jephthah Chanda who contributed to the review, edits and restructuring of the journal paper, diligently examining its content, ensuring accuracy and coherence. Revised sections to improve overall quality and readability, resolving any inconsistencies and synthesizing disparate ideas to create a cohesive narrative. Jacqueline Hiddlestone-Mumford, Choolwe Lucky Namoobe and Jephthah Chanda collaborated closely with the authors to strengthen arguments, streamline content and ensured that every aspect of the paper contributed effectively to its overarching message.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Data availability statement

Upon reasonable request, the corresponding authors will provide all supplemental files, data generated and analyses.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Enock Siankwilimba

Enock Siankwilimba, a seasoned agricultural market system development specialist with over two decades of experience, has contributed to numerous donor-funded agricultural market systems development programs and projects in Zambia. He is a founding member of Musika Development Initiative Zambia Limited, where he currently serves as a independent business consultant and technical advisor. Additionally, Enock is a PhD student at the University of Zambia’s Graduate School of Business Studies, focusing on developing a sustainable cattle farming business model for smallholder cattle farmers in Namwala District, Zambia, utilizing a systems-dynamic approach. His research interests encompass agricultural market system development, livestock and crop business models, climate change, circular economy business model, value chain development and rural agricultural extension development systems. Enock holds memberships with the Economic Association of Zambia (EAZ) and Zambia Network for Environmental Educators and Practitioners (ZANEEP).

Chisoni Mumba

Bernard Mudenda Hang’ombe, Professor, a bacteriologist with a BVM, MSc and Ph.D. from Osaka Prefecture University, has a special bias in bacteriology. He completed his post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Zambia and is an infectious disease expert. Hang’ombe has collaborated with the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock on controlling anthrax, epizootic ulcerative syndrome and plague. He has worked with the Food and Agricultural Organization, the World Organization for Animal Health and the Japanese International Cooperation Agency. At the university, Hang’ombe lectures on microbiology, public health and infectious diseases. His research focus is on emerging and re-emerging pathogens, with special emphasis on the diagnosis of rare bacteria (Anthrax and plague) and novel virus discoveries. Hang’ombe has co-authored over 90 publications and taught MSc and Ph.D. students about zoonotic bacterial diseases.

Bernard Mudenda Hang’ombe

Chisoni Mumba, Professor, holds a Bachelor of Veterinary Medicine from the University of Zambia, a Master of Science in livestock economics, and a PhD in veterinary science-animal health economics from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Chisoni is a senior lecturer and researcher at the University of Zambia, School of Veterinary Medicine, Disease Control Studies Department. His research interests are in animal health economics, systems thinking and participatory epidemiology. I am currently working on the application of systems thinking to address dynamic and complex animal health problems to achieve long-term solutions and avoid unintended consequences.

Notes

1 Zambian Kwacha (ZMW) at a rate of ZMW24 for every US dollar.

References

- African Financials. Financials. (2023). Zambeef advances Smallholder cattle project in Mbala—African Financials. https://africanfinancials.com/zambeef-advances-smallholder-cattle-project-in-mbala/

- Adesogan, A. T., & Dahl, G. E. (2020). MILK symposium introduction: Dairy production in developing countries. Journal of Dairy Science, 103(11), 9677–9680. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-18313

- Anderson, H., Müllern, T., & Danilovic, M. (2023). Exploring barriers to collaborative innovation in supply chains—A study of a supplier and two of its industrial customers. Business Process Management Journal, 29(8), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-12-2021-0796

- Bai, Y., & Cotrufo, M. F. (2022). Grassland soil carbon sequestration: Current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science (New York, N.Y.), 377(6606), 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.ABO2380

- Bai, Z., Fan, X., Jin, X., Zhao, Z., Wu, Y., Oenema, O., Velthof, G., Hu, C., & Ma, L. (2022). Relocate 10 billion livestock to reduce harmful nitrogen pollution exposure for 90% of China’s population. Nature Food, 3(2), 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00453-z

- Chapoto, A., & Subakanya, M. (2019). Rural agricultural livelihoods survey 2019 report. IAPRI. (Vol. 1). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Chilala, B. (2015). Risk Management and Market Participation among Traditional Cattle Farmers in Monze District of Southern Province Zambia. A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in AgriCommerce at Massey University, Manawatu, New Zealand. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/9872

- Creswell, J. W. (2019). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, (3rd Ed), 53(9) SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Curcio, D., Gianfrancesco, I., & Vioto, D. (2023). Climate change and financial systemic risk: Evidence from US banks and insurers. Journal of Financial Stability, 66, 101132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2023.101132

- Daum, T., Ravichandran, T., Kariuki, J., Chagunda, M., & Birner, R. (2022). Connected cows and cyber chickens? Stocktaking and case studies of digital livestock tools in Kenya and India. Agricultural Systems, 196, 103353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103353

- Deku, W. A., Wang, J., & Das, N. (2022). Innovations in entrepreneurial marketing dimensions: Evidence of Halal food SMES in Ghana. Journal of Islamic Marketing. 14(3), 680–713. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-03-2021-0098/FULL/XML

- FAO. (2019). Sustainability Pathways: Livestock and landscape. https://www.fao.org/3/ar591e/ar591e.pdf

- FAO. (2022a). Meat Market Review: Emerging trends and outlook 2022. https://www.fao.org/markets-and-trade/publications/detail/en/c/1620239/#:∼:text=The%20international%20meat%20prices%20reached,costs%20and%20extreme%20weather%20events.

- FAO. (2023a). FAOSTAT. Crops and livestock products—Food and Agriculture Data. Crops and livestock products https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL

- FAO. (2023b). World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2023. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc8166en

- FAO. (2022). Valuing, restoring and managing “presumed drylands”: Cerrado, Miombo–Mopane woodlands and the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0110en

- Fisheries, ZAMSTAT, and Livestock with MOFL. (2020). National aquaculture trade development strategy and action plan 2020 – 2024. Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry and Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock. Zambia www.mcti.gov.zm.

- González-Quintero, R., Bolívar-Vergara, D. M., Chirinda, N., Arango, J., Pantevez, H., Barahona-Rosales, R., & Sánchez-Pinzón, M. S. (2021). Environmental impact of primary beef production chain in Colombia: Carbon footprint, non-renewable energy and land use using Life Cycle Assessment. The Science of the Total Environment, 773, 145573. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2021.145573

- Gonzalez-Uribe, J., & Leatherbee, M. (2018). The effects of business accelerators on venture performance: Evidence from start-up Chile. The Review of Financial Studies, 31(4), 1566–1603. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhx103

- Hamududu, B. H., & Ngoma, H. (2020). Impacts of climate change on water resources availability in Zambia: implications for irrigation development. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(4), 2817–2838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-019-00320-9

- Hou, S., Xu, J., & Yao, L. (2021). Integrated environmental policy instruments driven river water pollution management decision system. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 75, 100977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100977

- IBM Corp. (2015). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0.

- Kalungu, R. (2023). Govt. engages stakeholders on CBPP outbreak in Chisamba, Chibombo—Zambia. News Diggers. https://diggers.news/business/2022/09/15/govt-engages-stakeholders-on-cbpp-outbreak-in-chisamba-chibombo/

- Khanal, N., & Thapa, S. (2023). Agroecological approach to agricultural sustainability, food sovereignty and endogenous circular economy. Nepal Public Policy Review, 3(1), 49–78. http://www.nppr.org.np/index.php/journal/article/view/57 https://doi.org/10.59552/nppr.v3i1.57

- Lubungu, M. (2016). Factors influencing livestock marketing dynamics in Zambia. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 28, 58. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd28/4/lubu28058.htm

- Maireva, C., & Rejoyce Magomana, N. (2021). The influence of endogenous factors on entrepreneurial success among youths in Masvingo Urban, Zimbabwe. East African Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 2(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.46606/eajess2021v02i02.0088

- Mbithi, B., Muturi, W., & Rambo, C. (2016). Effect of market development strategy on performance in Sugar Industry in Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 5(12), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v5-i12/1960

- MCTI. (2022). Annual Report. Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry (Issue December). https://www.mcti.gov.zm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2021-Annual-Report-for-sending.pdf

- Ministry of Finance and National Planning. (2022). Eighth Nationa development Plan (8NDP) 2022-2026. Ministry of Finance and National Planning.Lusaka.

- Muehlhausen, J. (2013). Business models for dummies (Vol. 1). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://books.google.co.zm/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tDA4uimT-mwC&oi=fnd&pg=PT21&ots=qBLzKWpYY1&sig=JRNvQvOEUGL44z2xWdE6xRcSmuY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Mulenga, B. P., Kabisa, M., Chapoto, A., & Muyobela, T. (2020). Zambia agriculture status report 2020. Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute (Issue January). http://www.iapri.org.zm/images/WorkingPapers/AgStatus_2017.pdf

- Muma, J. B., Munyeme, M., Samui, K. L., Siamudaala, V., Oloya, J., Mwacalimba, K., & Skjerve, E. (2009). Mortality and commercial off-take rates in adult traditional cattle of Zambia. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 41(5), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-008-9252-0

- Mumba, C., Häsler, B., Muma, J. B., Munyeme, M., Sitali, D. C., Skjerve, E., & Rich, K. M. (2018). Practices of traditional beef farmers in their production and marketing of cattle in Zambia. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 50(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-1399-0

- Mumba, C., Pandey, G. S., & der, J. C. v (2013). Milk production potential, marketing and income opportunities in key traditional cattle keeping areas of Zambia. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 25, 73. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd25/4/mumb25073.htm

- Mumba, C., Skjerve, E., Rich, M., & Rich, K. M. (2017). Application of system dynamics and participatory spatial group model building in animal health: A case study of East Coast Fever interventions in Lundazi and Monze districts of Zambia. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0189878. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189878

- Mutyasira, V. (2023). Transforming Africa’s food systems: a smallholder farmers’ perspective. Global Social Challenges Journal, 2(2), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1332/LPZJ2396

- Mwaanga, S. E., & Pares-Casanova, M. P. (2017). The Zambian Indigenous Cattle: A review of their origins and phenotype (1st ed., Vol. 1). https://www.amazon.com/Zambian-Indigenous-Cattle-origins-phenotype-ebook/dp/B0767LCND2

- Mwai, O., Hanotte, O., Kwon, Y. J., & Cho, S. (2015). African indigenous cattle: Unique genetic resources in a rapidly changing world. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 28(7), 911–921. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26104394/ https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.15.0002R

- Mzyece, A., Shanoyan, A., Amanor-Boadu, V., Zereyesus, Y. A., Ross, K., & Ng’Ombe, J. N. (2023). How does who-you-sell-to affect your extent of market participation? Evidence from smallholder maize farmers in Northern Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2184062, P1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2184062

- Ng’ombe, J. N., Addai, K. N., Mzyece, A., Han, J., & Temoso, O. (2023). Uncovering the factors that affect earthquake insurance uptake using supervised machine learning. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48568-6

- Ngoma, H., Finn, A., & Kabisa, M. (2021). Climate shocks, vulnerability, resilience and livelihoods in Rural Zambia. http://www.worldbank.org/prwp.

- Ngoma, H., Lupiya, P., Kabisa, M., & Hartley, F. (2021). Impacts of climate change on agriculture and household welfare in Zambia: An economy-wide analysis. Climatic Change, 167(3–4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03168-z

- Ngoma, H., Marenya, P., Tufa, A., Alene, A., Chipindu, L., Matin, M. A., Thierfelder, C., & Chikoye, D. (2023). Smallholder farmers’ willingness to pay for two-wheel tractor-based mechanisation services in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Journal of International Development, 35(7), 2107–2128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3767

- Nkonki-Mandleni, B., Ogunkoya, F. T., & Omotayo, A. O. (2019). Socioeconomic factors influencing livestock production among smallholder farmers in the free state Province of South Africa. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 23(1), 1–17.

- Odubote, I. K. (2020). The role of livestock production in addressing poverty and hunger in a changing environment: Case study of Zambia. Bulletin of Animal Health and Production, 67(4), 341–353.

- Odubote, I. K. (2022). Characterization of production systems and management practices of the cattle population in Zambia. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 54(4), 216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-022-03213-8

- Odubote, I. K., Musimuko, E., Rensing, S., Schmitt, F., & Kapotwe, B. (2023). Genetic survey in smallholder dairy production system of Southern province of Zambia. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 140(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbg.12749

- Orhan, Z. H. (2018). Business model of Islamic banks in Turkey. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 9(3), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-10-2014-0037

- Padela, S. M. F., Wooliscroft, B., & Ganglmair-Wooliscroft, A. (2023). Brand Externalities And Brand Systems: A Macromarketing Systems Perspective. Auckland University of Technology. https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/e927e3c6-9a78-4b1c-af37-c3254d22ab16/content

- Siankwilimba, E. (2019). Effects of climate change induced electricity load shedding on small holder agricultural enterprises in Zambia: The case of Five Southern Province Districts. IJRDO - Journal of Agriculture and Research (ISSN: 2455-7668), 5(8), 01–151. 1. https://doi.org/10.53555/ijrdo/3184

- Siankwilimba, E., Hiddlestone-Mumford, J., Hoque, M. E., Hang’ombe, B. M., Mumba, C., Hasimuna, O. J., Maulu, S., Mphande, J., Chibesa, M., Moono, M. B., Muhala, V., Cavaliere, L. P. L., Faccia, A., & Prayitno, G. (2023b). Sustainability of agriculture extension service in the face of COVID-19 : A study on gender market systems. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2284231

- Siankwilimba, E., Hiddlestone-Mumford, J., Mudenda, H., Mumba, C., & Hoque, E. (2022). COVID-19 and the sustainability of agricultural extension models. International Journal of Applied Chemical and Biological Sciences, 3, 1–20. https://identifier.visnav.in/1.0001/ijacbs-21l-05003/

- Siankwilimba, E., Mumba, C., Hang’ombe, B. M., Munkombwe, J., Hiddlestone-Mumford, J., Dzvimbo, M. A., & Hoque, M. E. (2023a). Bioecosystems towards sustainable agricultural extension delivery: effects of various factors (pp. 1–43). In Environment, Development and Sustainability. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03555-9

- Sibhatu, K. T., & Qaim, M. (2018). Review: The association between production diversity, diets, and nutrition in smallholder farm households. Food Policy, 77, 1–18. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.04.013

- Simuunza, M. (2022). Livestock sector review report—Zambia. FAO, 1(2), 1–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300006160

- Subakanya, M., & Chapoto, A. (2020). RALS 2019 Survey Report (Issue June). Zambia.

- Szromek, A. R., Herman, K., & Naramski, M. (2021). Sustainable development of industrial heritage tourism—A case study of the Industrial Monuments Route in Poland. Tourism Management, 83, 104252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104252

- Todaro, M. P., & Smith, S. C. (2015). Economic development: The Addison-Wesley series in economics (12th ed.). Pearson.

- Van Eenennaam, A. L., De Figueiredo Silva, F., Trott, J. F., Zilberman, D., Chand, P., Sirohi, S. K., Sirohi, S. K., Jayne, T. S., Muyanga, M., Wineman, A., Ghebru, H., Stevens, C., Stickler, M., Chapoto, A., Anseeuw, W., van der Westhuizen, D., & Nyange, D. (2019). District level sustainable livestock production index: Tool for livestock development planning in Rajasthan. Agricultural Economics (United Kingdom), 50(2), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12535

- Vandome, C. (2023). Zambia’s developing international relations: ‘Positive neutrality’ and global partnerships (Issue March). https://doi.org/10.55317/9781784135553

- Wen, M., & Chen, L. (2023). Global food crop redistribution reduces water footprint without compromising species diversity. Journal of Cleaner Production, 383, 135437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135437