?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Corporate innovation plays a crucial role in maintaining competitiveness and enhancing firm value. However, despite being the world’s leading manufacturing nation, the role of managerial ownership in fostering innovation within the Chinese manufacturing industry has not received adequate attention. Therefore, this research investigates the influence of managerial ownership on corporate innovation using data on patent activities from Chinese listed manufacturing firms covering the period from 2008 to 2021. Drawing on agency theory, empirical evidence confirms a positive relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation. This result remains robust across various tests, including the use of alternative dependent variables, the application of two-stage Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to control for managerial ability, correction of selection bias using Heckman two-stage estimation, and the utilization of Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimators. Additionally, the study clarifies the input channel and efficiency channel through whic-h managerial ownership positively influences corporate innovation. This paper contributes to the literature on corporate innovation by offering evidence for the role of managerial ownership on the innovation output. It also offers valuable governance insights for policymakers in emerging economies who are exploring corporate governance mechanisms for innovation systems, aiming to facilitate a systemic shift toward an innovative manufacturing economy.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Unlike most prior studies on corporate innovation, this research focuses on the manufacturing sector in China, investigating the impact of managerial ownership on innovation from the perspective of patent activities. It is noteworthy that this study employs the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) controlling for managerial ability, Heckman two-stage estimation correcting for selection bias, and the use of a dynamic panel GMM estimator to control for omitted variables and endogeneity of reverse relationships—factors rarely considered in previous research. Additionally, this paper elucidates three aspects through which managerial ownership fosters innovation (innovation input, innovation output, and innovation efficiency). Overall, this study holds crucial implications for both firms and policymakers, offering insights into enhancing the competitiveness and innovation value of the manufacturing industry through equity incentives.

1. Introduction

It is widely recognized that corporate innovation is vital for sustaining competitiveness and enhancing firm value (Baer, Citation2012; Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018). Given its pivotal role in driving competitiveness, numerous studies have explored the equity characteristics that incentivize such innovative behavior. From the perspective of innovation output, these attributes encompass factors such as state ownership (Zhang et al., Citation2022), institutional ownership (Rong et al., Citation2017), foreign ownership (Joe et al., Citation2019), and ownership concentration (Nguyen et al., Citation2021). However, there is a limited body of research that systematically investigates the potential of managerial ownership in promoting corporate innovation.

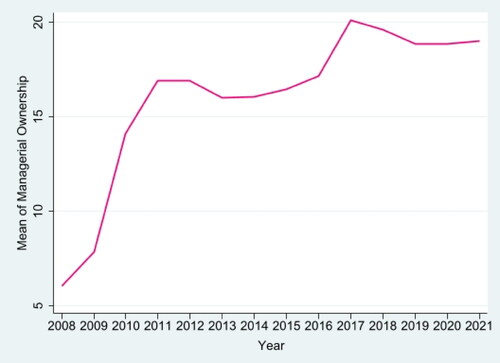

This study aims to bridge this gap by exploring the impact of managerial ownership on corporate innovation within the Chinese manufacturing sector. Over the past few decades, China’s economic landscape has undergone a profound transformation, with its manufacturing sector output consistently securing its position as the world leader for 13 consecutive years, as of 2022 (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China, Citation2023). Even when confronted with an innovation crisis in international competition, managerial ownership remains a pivotal driving force in strategic decision-making, resource allocation, and the innovation process within Chinese manufacturing firms (Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Shan, Citation2019; Wen et al., Citation2022; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2022). In fact, the overall sample yearly managerial shareholding rates of Chinese listed manufacturing sector were analysed (), and surprisingly, they are observed to greatly fluctuate and range between 5% and 20%. Thus, it increases the interest of this study in trying to unveil the intricate mechanisms through which managerial ownership influences innovation output. Although our empirical evidence is based on data from the Chinese listed manufacturing firms, we believe that the results of our study are also relevant to other emerging economies that share similar characteristics with China.

Figure 1. The trend of managerial shareholding rates in the Chinese listed manufacturing sector (2008–2021). Note: The study has used the industry mean value for managerial ownership in this figure.

Existing research has indicated that innovation projects face long-term risks of failure, which may have adverse implications for managers’ short-term personal interests and career prospects (Holmstrom, Citation1989; Iqbal et al., Citation2020; Joe et al., Citation2019). From the perspective of agency theory, innovation activities entail an agency conflict between the long-term interests of shareholders and the short-term personal interests of managers (Holmstrom, Citation1989; Salehi et al., Citation2018). To mitigate this conflict of interest, the amplification of managerial ownership aligns the interests of managers and shareholders, thereby reducing agency costs (Hirshleifer & Thakor, Citation1992; Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2021). While theoretically, managerial ownership may be beneficial for corporate innovation, the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain unclear, particularly within the context of China.

In addition, with the presence of similar legal frameworks and standards in patent systems globally, patent data serve as a universally applicable indicator of innovation output (Higham et al., Citation2021). This study relies on patent data to gauge corporate innovation, facilitating international comparisons and competitive analyses among manufacturing firms worldwide. Specifically, this study verifies whether managerial ownership promotes corporate innovation and further investigates two channels through which managerial ownership influences corporate innovation. On the one hand, it examines whether managerial ownership enhances corporate innovation by increasing the firm’s research and development investment (referred to as the ‘input channel’). On the other hand, it scrutinizes innovation efficiency in comparing the level of patent output after controlling for research and development investment, providing further insights into the ‘efficiency channel’.

This paper has some potential contributions. First, it enriches the growing body of literature concerning the economic implications of managerial ownership. Despite its significance as a corporate governance mechanism, empirical evidence regarding the relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation remains sparse. The closest study in alignment with our topic is Choi et al. (Citation2011), which examined the impact of insider ownership (including the founders of firms and their families, affiliates, managers, executive directors, and employees) on innovation in 548 Chinese firms using data from 2001 to 2004. Informed by Choi et al. (Citation2011), our research seeks to elucidate pathways that translate managerial ownership into exceptional performance in corporate innovation. Meanwhile, the study finds that increasing managerial ownership positively correlates with innovation input, innovation efficiency and innovation output. These findings further substantiate the influence of managerial ownership on firms’ innovation activities.

Second, the positive impact of managerial ownership on corporate innovation provides nuanced evidence to the policymakers of emerging countries, which complements the literature on emerging countries’ innovative activities. In previous research little mention has been made of the roles of managerial ownership in innovating emerging countries, and this study has explored new insights into this area. It is also an important inspiration for emerging economies that are seeking to search for corporate governance mechanisms of innovation systems to make a regime shift to an innovative economy of the manufacturing sector.

The paper is organized into the following parts: Section 2 presents the background. Section 3 briefly summarises the relevant theoretical literature. Section 4 provides a literature review and develops the hypotheses. Section 5 describes the data sources and methodology. Section 6 empirically tests the impact of managerial ownership on corporate innovation, sets out robustness checks and further analyses the influence mechanism. Finally, Section 7 concludes this study.

2. Research background

2.1 The crisis of innovation in the Chinese manufacturing industry

Over the years, benefiting from the substantial advantage of the ‘demographic dividend,’ unique Chinese economic phenomena such as ‘Made in China’, ‘Smart Manufacturing in China’, and the label ‘World Factory’ have been enduring topics in discussions among economists and policymakers (e.g. Cai & Wen, Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2021). What puzzled them was that within a mere nine years after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization on December 11, 2001, the output value of China’s manufacturing industry consistently ranked first globally from 2010 onwards. Some scholars contend that China’s success stems from its low labor costs and the vast domestic market, attracting global capital to invest in manufacturing facilities, thereby establishing itself as an indispensable force in the global manufacturing landscape (e.g. Ceglowski & Golub, Citation2012; Klafke et al., Citation2018).

However, despite the colossal scale of its output, China’s manufacturing industry has historically operated at the lower end of the value chain (Liu et al., Citation2022). The rapidly aging population and the swift rise in labor costs within China have intensified the innovation competitiveness crisis in its manufacturing industry (Zheng et al., Citation2023). An undeniable phenomenon is the escalating severity of labor cost increases, particularly among top management (Buck et al., Citation2008; Cheng et al., Citation2019). Given the crucial role that top management plays in shaping the innovation environment, formulating innovative strategies, and driving innovative projects, the manufacturing sector in China has adopted long-term incentives, including equity, to alleviate potential agency conflicts (Jiang & Kim, Citation2020). These distinctive governance practices, along with their underlying impact mechanisms, may differ from those in other developed economies. This unique governance environment provides a noteworthy dimension worthy of exploration for emerging economies.

2.2 Background of recent developments in innovation measurement

Historically, the developments in innovation measurement have been a long-debated topic in the fields of technology and innovation management (Chiesa, Citation1999; Criscuolo et al., Citation2017). Some scholars advocate proactive exploration in measuring corporate innovation (e.g. Markham & Lee, Citation2013). Scholars in this domain argue that developing multidimensional measures of innovation can assist managers in promoting structural causal relationships, ensuring comprehensive support, and effective execution of innovation. In contrast, others argue that the criteria for measuring corporate innovation may impede managers from pursuing breakthrough innovation outcomes, as it forces attention onto a singular metric (Abernethy & Brownell, Citation1997; Criscuolo et al., Citation2017).

Corporate innovation, is a vital framework for significant improvements in products (goods or services), processes, and production methods within business practices, workplace organizations, or external relationships (Azeem et al., Citation2021; Tushman & Nadler, Citation1986). Most views emphasize that its measurement should encompass diverse information and processes (e.g. Abernethy & Brownell, Citation1997; Bessonova & Gonchar, Citation2017; Jia et al., Citation2019; Lantz & Sahut, Citation2005). Typically, innovation activities involve inputs into innovation, the efficiency of transforming innovative elements, and the quality of innovative outcomes. Therefore, early measures of corporate innovation often focused on R&D inputs and innovation efficiency (Chen et al., Citation2017). A contentious issue lies in factors such as firm size, industry competitiveness, and innovation capabilities, which often determine the magnitude of R&D inputs and efficiency (Campbell et al., Citation2006; Machokoto et al., Citation2021; Sher & Yang, Citation2005; Tsai, Citation2005). Additionally, manipulation of R&D inputs can mislead the rationale for metrics based on R&D inputs and efficiency (Hsu & Hsueh, Citation2009).

From the perspectives of invention and technology, there is a close connection between patent activities and innovation. Recent literature recognizes that the output of innovation itself is a specific stage in the innovation process, categorized into technological innovation and institutional innovation based on objects and incremental innovation and radical innovation based on degree (Chen & Kim, Citation2023; Coccia, Citation2016). The fundamental process of innovation includes: (1) input into innovation, i.e. the conduct of R&D activities; (2) intermediate innovation output, i.e. the formation of inventions, including the invention of patented applications; and (3) final innovation output, such as new products. The process of patent output is often the R&D results of scientific and technological research, indicating a close link between patents and R&D activities and expenditures, as extensively verified in empirical research (e.g. Hsu & Hsueh, Citation2009; Miguélez & Moreno, Citation2015).

In addition, patent applications are usually pursued for commercialization purposes, involving high time and capital costs for application and maintenance, reflecting the applicant’s belief that applying for patents for specific technologies can yield anticipated returns (Cappelli et al., Citation2023; Mochly‐Rosen et al., Citation2023). In other words, applicants believe that patents have at least a potential role in economic development, leading them to invest in R&D and other innovation elements. When this potential role transforms into reality, patents become powerful evidence of innovation. At the same time, utilizing evidence from patent activities as a proxy for corporate innovation challenges previous conclusions about the determinants of corporate innovation.

3. Theoretical literature review

As firm growth accompanies changes in corporate governance mechanisms, the separation of ownership and control emerges as a consequence of this phenomenon (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; O’Connor & Rafferty, Citation2012). According to agency theory, the governance process of a firm is not principal-driven but agent-driven, culminating in the manifestation of agency problems (Eriqat et al., Citation2023; Holmstrom, Citation1989; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1986). Due to the incomplete monitoring of managers (agents) by shareholders (principals), a decline in shareholder power and a gradual enhancement of managerial authority ensue (Cohen et al., Citation2013; Hirshleifer & Thakor, Citation1992; Holmstrom, Citation1989).

Corporate governance represents one of the mechanisms to alleviate agency problems between shareholders and managers in capital markets (Hirshleifer & Thakor, Citation1992; Pepper, Citation2018; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1986). According to the perspective of Palia and Lichtenberg (Citation1999), information asymmetry motivates self-interested managers to shirk responsibilities or exploit firm resources for personal gain, such as pursuing salary allowances and in-job consumption. In such cases, with the amplification of managerial ownership, an incentive-compatibility effect emerges, as it frequently aligns managerial and shareholder interests more closely, diminishing managerial risk and consequently reducing agency costs (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; O’Connor & Rafferty, Citation2012; Zhang et al., Citation2018). Simultaneously, changes in firm equity structure enable managers to acquire a greater share of firm income from risky activities. Thus, when the alignment of managers’ interests with those of shareholders becomes more robust, they are more inclined to invest in projects that maximize firm value (Laux & Ray, Citation2020; Morck et al., Citation1988).

4. Empirical literature review and hypothesis development

The primary objective for shareholders when considering investment in innovation activities is to maximize the firm’s profits and achieve outstanding long-term performance (Bessonova & Gonchar, Citation2017; Iqbal et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, managers have prerequisites such as job stability, a good personal reputation, and short-term income before achieving the aforementioned goal (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Laux & Ray, Citation2020). Meanwhile, there exists an information asymmetry between shareholders and managers, which leads to insufficient monitoring of managerial behaviour, resulting in conflicts of interest and agency problems (Cohen et al., Citation2013; Palia & Lichtenberg, Citation1999; Salehi et al., Citation2018).

On the one hand, one limitation to innovation caused by agency problems is the different investment motivations of managers. Compared to shareholders, managers have more advantages in terms of internal information within the firm, and they have the authority to decide whether to invest in conventional projects or riskier innovation activities (Jun & Wang, Citation2018). Prior research demonstrates that managers tend to make short-term investments to expand the size of the firm, thereby increasing their own compensation and privileges (Cohen et al., Citation2013; Palia & Lichtenberg, Citation1999). This behaviour often serves the personal interests of managers, but sacrifices long-term profit opportunities for shareholders.

On the other hand, one further limitation to innovation caused by agency problems is the different risk appetites of managers and shareholders. Due to risk aversion, managers often demonstrate management conservatism and intentionally steer clear of risky ventures, ultimately leading to a decrease in innovative output (Chen et al., Citation2020; Hirshleifer & Thakor, Citation1992; Laux & Ray, Citation2020). Generally, the personal profit of managers is largely dependent on the performance of the firm they manage, especially when short-term performance affects their income and the risk of unemployment. High-risk innovation activities often encourage managers to avoid potential failures, thereby reducing their commitment (Chen et al., Citation2020; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Laux & Ray, Citation2020).

In contrast, shareholders may have different risk appetites. According to Baer (Citation2012), innovation contributes to the sustained achievement of outstanding firm performance and stimulates firm growth. This is why shareholders often favor firms that have research and development projects and are committed to long-term profitability (Cohen et al., Citation2013; Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2018). Due to the share’s option-like characteristics, shareholders often favour risky projects, as the value of their shares may increase with the disclosure of innovation projects and attract market attention (Bai et al., Citation2023; He et al., Citation2022; Jun & Wang, Citation2018). Additionally, successful innovation projects may generate significant returns that shareholders can also share (Chen et al., Citation2020; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2018). However, these risks conflict with the personal interests of managers (Chiesa & Frattini, Citation2011; Jun & Wang, Citation2018).

Conflicts of interest between managers and shareholders arise in innovation activities due to their varying investment motivations and risk appetites. Equity incentives are well known as a tool for the improvement of corporate governance that functions as an incentive to motivate managers to take risks and increase their efforts to align the interests of shareholders and managers (Chiesa & Frattini, Citation2011; Cohen et al., Citation2013; Cosci et al., Citation2015; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Zhou et al., Citation2021). Therefore, managerial ownership can offer a benefit in innovation operation efficiency by encouraging managers to shoulder excessive risk and invest in long-term, innovative projects. This ultimately results in the alignment of shareholders’ and managers’ interests (Pepper, Citation2018; Salehi et al., Citation2018).

Overall, the above discussion has led to the following hypothesis:

H1: Ceteris paribus, managerial ownership has a positive impact on corporate innovation.

5. Research design

5.1. Data sources and sample

This study obtained the ownership structure and financial information of all A-share Chinese listed manufacturing firms on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets from the CSMAR database for 2008–2021, and patent information was sourced from the CNRDS database. Following the approaches of Yuan and Wen (Citation2018) and Zhang et al. (Citation2022), this study cross-verified with annual reports and official websites by the firm’s own information. Meanwhile, the data underwent the following preprocessing steps: first, ‘special treatment’ firms (referring to firms with continuous losses for two consecutive years and facing delisting risk) were excluded to avoid interference from abnormal financial conditions; second, observations with missing information were deleted to mitigate the impact of missing values on the results; third, to minimize the influence of extreme values, all continuous variables were winsorised at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

5.2. Variable measurement and model specification

The dependent variable of this study was corporate innovation. Its measurement uses four patent volume pieces of information from the CNRDS database as the source of innovation level. It is a professional patent system covering a number of measurement sources and patent information data analysis. Following past studies (e.g. Ding et al., Citation2022; Iqbal et al., Citation2020; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018), the first measure, Patent_ total, represents the natural logarithm of a firm’s total patents applied for plus one, including invention patents, design patents, and utility patents. The second, Patent_invention, represents the natural logarithm of a firm’s invention patents applied for plus one. The third measure is Patent_ Gtotal, which is the natural logarithm of a firm’s total patents granted plus one. The fourth measure is Patent_ Ginvention, which is the natural logarithm of a firm’s invention patents granted plus one. It should be emphasized that the third and fourth indicators serve as measures of corporate innovation for robustness checks.

The independent variable of our focus is managerial ownership (MO). Following the approach of Himmelberg et al. (Citation1999), this study uses ratio variables to measure MO, the total equity holdings of top management, as a fraction of a firm’s total equity.

In terms of control variables, following past studies (e.g. Ding et al., Citation2022; Jia et al., Citation2019; Liu & Lv, Citation2022; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018), this research controlled a series of variables that may be biased to corporate innovation, such as firm age (FA), firm size (FS), return on assets (ROA), financial leverage (LEV), cash ratio (CR), asset turnover (AT), sales growth (SG), and ownership concentration (OC). Moreover, this study also controls for the impact of firm and annual factors to capture the firm fixed effect and dynamics of changes in the macroeconomic conditions common to all firms over the sample period, respectively. Appendix A presents the definitions of all variables in this study.

The following equation is used to investigate the relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation.

(1)

(1)

where

denotes the intercept, and

are the coefficients to be estimated. This study added dummy variables that control for year and firm fixed effects (Year and Firm), ε is the error term, i denotes the cross-sectional dimension for firms, and t denotes the time series dimension.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

reports the distribution of dummy variables in the firm with managerial ownership over the sample period. In this table, it can be seen that more than half of the total sample of firms had managerial shareholdings within the period from 2008 to 2021. Across all observed years, firms with managerial ownership had the lowest proportion in the initial sample year of 2008, approximately 71.9%. The highest proportion occurred in the final year of our sample, 2021, reaching its peak at around 88.68%. The overarching trend indicates a gradual increase in the prevalence of firms with managerial ownership.

Table 1. Sample distribution.

illustrates the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this research. For the patent application indicators, the mean and standard deviation for Patent_total (Patent_invention) are 2.979 and 1.571 (2.094 and 1.458), respectively. For the patent grant indicators, the mean and standard deviation for Patent_Gtotal (Patent_Ginvention) are 2.795 and 1.515 (1.386 and 1.250), respectively. These figures underline the considerable variation in innovation output among the sampled firms. On average over the 14 years of firm-level observations, managerial ownership (MO) is 17.352%. However, for some firms, managerial ownership could be as high as 73.266%.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Regarding the control variables, the sample means include an average firm age (FA) of 2.816, firm size (FS) of 21.955, return on assets (ROA) of 0.051, financial leverage ratio (LEV) of 3.952, cash ratio (CR) of 0.053, asset turnover (AT) of 0.693, sales growth (SG) of 0.173, ownership concentration (OC) of 34.291, and research and development (R&D) of 0.023.

shows the Pearson coefficients of the main variables used in the study. Overall, the correlation coefficients between a dependent variable and other variables are less than 0.50, and the multicollinearity diagnostic test shows a low variance inflation factor (VIF). The highest value observed is 1.58, which is well below the rule of thumb cut-off of 10.00 for multiple regression models (Kennedy, Citation1979), which suggests that multicollinearity is not a main problem in our model.

Table 3. Pearson correlation analysis and variance inflation factor.

6.2. Baseline results

presents the regression results of the two-way fixed effects model. These models are based on two corporate innovation indicators: Patent_total and Patent_invention. In addition, as using panel data, heteroskedasticity is difficult to avoid, following the relevant literature (e.g. Joe et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2022), the research has used robust standard error estimators to eliminate this problem.

Table 4. Benchmark regression results.

Columns (1) to (4) test the relationship between managerial ownership (MO) and corporate innovation (Patent_ total and Patent_invention), and the four regression models incorporate both firm and year dummy indicators. The coefficient on MO is significantly positive at the 5% significance level (0.002, t = 2.38) in column (1), which indicates that powerful managerial ownership exhibits higher innovation output. In column (2), the coefficient on MO is also significantly positive at the 5% significance level (0.002, t = 2.19), which indicates that this conclusion still holds with the addition of four control variables. Meanwhile, the coefficient on MO is significantly positive at the 1% significance level (0.003, t = 3.03) in column (3), which indicates that the conclusion still holds when the indicator of corporate innovation is changed to Patent_invention. In addition, column (4) also shows the regression results that examine the impact of MO on Patent_invention that added additional control variables. Additionally, the positive coefficient on MO in column (4) is 0.002, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating that managerial ownership can enhance corporate innovation output, both in statistical and economic terms.

The aforementioned findings support hypothesis H1 of this study, indicating that managerial ownership does indeed enhance innovation output within patent activities. Consequently, the provision of long-term incentives in the form of equity to managers proves beneficial in mitigating the adverse effects between managers and shareholders in innovation activities (Jun & Wang, Citation2018; Salehi et al., Citation2018; Shan, Citation2019). This outcome reinforces the perspective that agency costs between principals and agents constrain efforts by firms to achieve high levels of innovative performance (Iqbal et al., Citation2020; Tushman & Nadler, Citation1986). Moreover, managerial ownership also emerges as an effective governance mechanism to balance the interests between managers and shareholders (Chiesa & Frattini, Citation2011; Cohen et al., Citation2013; Cosci et al., Citation2015; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Zhou et al., Citation2021). Hence, endorsing managerial ownership of shares contributes significantly to maximizing the innovation output of the firm.

With regard to the control variables, the results for coefficients and significance are generally the same as the conclusions of Yuan and Wen (Citation2018) and Wen et al. (Citation2022). The estimated coefficients for FS, ROA, and LEV are positive and significant, while the coefficients of FA, AT, CR, SG, and OC are not significant.

6.3. Robustness check

The findings of the above analysis suggest a positive relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation. However, these results may be subject to endogeneity concerns. For example, unobservable heterogeneity of equity incentives on managerial ability formation; and managerial ownership may not be purely random across sub-industries of manufacturing, potentially introducing self-selection bias; it is also possible that omitted variables influence both the level of managerial ownership and corporate innovation, thereby confounding our results. Moreover, there may be a concern about reverse causality, whereby firms with high innovation potential may give managers greater ownership stakes.

In addition to the two-way fixed effect model incorporating the use of two patent grant indicators, this section addresses potential endogeneity concerns through various approaches. These include controlling managerial ability by application of the two-stage data envelopment analysis (DEA) model, correcting selection bias by the use of Heckman two-stage estimation, and using the dynamic generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation. Together, these methods enhance the robustness and validity of our results by addressing potential endogeneity issues.

6.3.1. Alternative dependent variables

Panel A of shows the results of replacing the two indicators with the number of patents granted, namely Patent_Gtotal and Patent_Ginvention. The first alternative dependent variable is the natural logarithm of one plus the total number of patents (invention, design and utility) granted (Ding et al., Citation2022). The second alternative dependent variable is the natural logarithm of one plus the number of invention patents granted (Ding et al., Citation2022). The rationale for using these two measures of patent grants lies in the consideration that not all patent applications result in patent grants, potentially introducing measurement bias into the assessment of innovation.

Table 5. Robustness check (1).

Columns (1) and (2) indicate that MO has a statistically significant positive effect on Patnet_total (Patnet_invention) at the 1% level. This suggests that the potential measurement error associated with the indicators of corporate innovation may not be the primary endogeneity concern underlying the previous conclusions. The results thus underline the robustness of the observed relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation across different measures of innovation.

6.3.2. Controlling managerial ability by application of the two-stage DEA model

As this study mentioned above, managerial ownership provides managers with equity incentives to innovate. One possibility is that it increases managers’ motivation to innovate, making them more inclined to use their abilities to drive corporate innovation. Another possibility is that in connection with the receipt of equity incentives, managers’ individual risk-averse motives may also increase as a reflection of their greater power and ability (Lo & Shiah-Hou, Citation2022), leading to a reduction in their ability to manage innovation activities. After all, corporate innovation is characterized by high risks and a long-term nature. Thus, equity incentives might serve as a proxy for managerial ability, potentially driving outcomes and leading to unobservable heterogeneity.

Measuring managerial ability was a challenging issue before the development of the two-step procedure by Demerjian et al. (Citation2012), but since then this approach has been widely applied in accounting, finance, and management research (e.g. Krishnan & Wann, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2021; Yuan & Wen, Citation2018). This study employs this model to assess managerial ability (MA). In the first step, DEA is used to assess the overall efficiency of the sample firms. In the second step, the manager’s contribution is separated from the firm’s efficiency, as total firm efficiency includes both the firm’s efficiency and the manager’s efficiency. Through these two steps, the derived managerial ability indicator is used as a control variable in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) , and the regression is run again.

The findings in Panel B of confirm these concerns about unobservable heterogeneity, as MA is significantly negative at the 1% level in columns (3) to (4), confirming the second concern of this section. Furthermore, these results consistently suggest that managerial ability is unlikely to alter the positive relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation.

6.3.3. Correcting selection bias by using Heckman two-step estimation

As members of the firm’s top management team, managers’ equity incentives may be influenced by non-random factors, including the equity incentive levels of peers within the different sub-industries, which may affect the level of equity incentives granted to executives within a firm. This study employs the Heckman two-stage sample selection model to ensure robustness as selection bias is a possible concern in this particular situation.

Drawing on the approach of Yuan and Wen (Citation2018), in the first step, a probit model is estimated with a binary dependent variable (Dummy_MO) that takes the value of 1 if a firm has managerial ownership and 0 otherwise. The dependent variable of the probit model is determined by managerial ownership and explained by the following factors: ownership concentration (OC), board size (BS), board independence (BI), firm age (FA), firm size (FS), return on assets (ROA), financial leverage (Lev), CEO duality (Dual) and average percentage of managerial ownership within the same sub-industries, excluding related firms (Mean_MO).

The first stage of the Heckman estimator requires the use of partially exogenous variables that are related to the propensity of firms to grant equity incentives to managers but are unrelated to corporate innovation. In particular, the average percentage of managerial ownership within the same sub-industries is expected to be an influential factor in firms’ decision to offer managerial equity incentives but is likely to be less closely associated with corporate innovation. The definitions of these variables are given in Appendix A. The model specification is presented below.

(2)

(2)

The inverse mills ratio (IMR) is constructed from the first-step model and incorporated into the second-step model to control for potential sample selection bias. The second step model specification is the same model as described in Section 5.2 (EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ). In Panel C of , the regression results of the two-stage Heckman sample selection model show that after controlling for unobserved factors that induce firms to provide equity incentives to managers, the coefficients of MO remain significantly positive at the 5% and 1% levels in columns (5) and (6), respectively, suggesting a positive and robust relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation.

6.3.4. Instrumental variables estimator via the dynamic GMM approach

Regarding the relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation, a concern with the benchmark regression results is that the estimated impact of managerial ownership on firms’ patenting could be driven by omitted variables and reverse causality mechanisms arising from the possibility that high-innovation firms might lead to greater equity incentives for managers. The GMM approach is well-suited to mitigate reverse causality and omitted variable bias (Arellano & Bover, Citation1995; Blundell & Bond, Citation1998; Boadi et al., Citation2023; Roodman, Citation2009). Therefore, this section employs the difference GMM (one-step and two-step) and system GMM (one-step and two-step) estimation approaches to alleviate distortions caused by endogeneity issues arising from reverse causality and omitted variables that might affect the relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation.

displays GMM regression findings that tested the study’s hypothesis; columns (1) to (8) give the results of regressing MO on Patent_total (Patent_invention). After passing the Arellano-Bond test and the Hansen test of overid, the coefficient of MO is significantly positive at the 5% or 1% level, which suggests that the regression findings are still robust.

Table 6. Robustness check (2).

6.4. Further analyses

As discussed in the hypothesis development section, providing managers with equity incentives to reduce agency conflicts could align their long-term interests with those of shareholders, thereby encouraging increased research and development (R&D) investment in innovation activities. Meanwhile, the studies by Hou et al. (Citation2017) and Zhang et al. (Citation2022) suggest that R&D input and innovation efficiency are critical determinants of corporate innovation, and insufficient R&D investment and inefficient innovation operations can impede sustained innovation activity. Therefore, following the approach of Yuan and Wen (Citation2018), this section uses R&D investment as a dependent variable. The results reported in column (1) of suggest that managerial ownership (MO) increases R&D investment.

Table 7. Further analysis.

In addition, the amount of R&D investment (input channel) is related to the number of patents, and it is possible that managers are likely to receive more equity incentives from firms with high R&D investments. Hence, including R&D as a control factor and comparing patent output may help to understand innovation efficiency. Following Yuan and Wen (Citation2018), the study rerun the regressions of EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) controlling for R&D and tabulate the results for compared innovation efficiency in columns (2) to (3). Consistent with the overall result in , the results show that controlling for the level of R&D as an input, MO helps to produce more patents, which suggests an efficiency channel that increases innovation output (Patent_total and Patent_invention).

In summary, our findings explain the input channel and the efficiency channel (both R&D investment and patents) through which managerial ownership may affect corporate innovation.

7. Summary and conclusion

This study investigates the relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation using a sample of Chinese listed manufacturing firms over the period 2008–2021. In line with investment motives and risk appetite predicted by agency theory, the finding suggests that managerial ownership is a significant determinant of enhencing corporate innovation, and the result was robust in a series of checks such as adopting alternative dependent variables, controlling managerial ability by application of the two-stage DEA model, Heckman two-step estimation, and GMM dynamic estimators. Further results show that the input channel and efficiency channel are two key aspects in the positive relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation in our sample.

The results of this study provide a significant contribution to theoretical development. To establish the hypothesis regarding the impact of managerial ownership on corporate innovation, this research draws upon two aspects of the agency theory literature: investment motives and risk appetite within agency issues. In contrast to Choi et al. (Citation2011) examination of insider ownership (including the founders of firms and their families, affiliates, managers, executive directors, and employees) on corporate innovation, this study independently investigates the relationship between managerial ownership and innovation output metrics, including patent applications and grants, and these hypotheses find empirical support. Thus, our findings contribute to enriching the knowledge base surrounding the relationship between managerial ownership and corporate innovation.

The findings of this study also hold significant practical implications. For firms aspiring to achieve long-term excellence in performance and competitiveness, the identified corporate governance mechanisms (managerial ownership) of the study offer essential insights for designing appropriate equity incentives to enhance corporate innovation. Furthermore, some scholars have noted that managers in emerging economies may have more control over innovation activities than those in developed countries, which could lead to higher agency costs (Bessonova & Gonchar, Citation2017; Claessens et al., Citation2000). Consequently, the policy implications of this study may be particularly valuable for emerging economies.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, it measures corporate innovation solely using patent data, which serve as legal protection for the holder’s intellectual property. However, not all firms protect their technological assets and innovation through patents. Some may prefer to treat their expertise as a trade secret or implement organizational mechanisms to protect innovation. Second, the generalizability of the findings is limited by our use of one country as the research context. To tackle these limitations, future work should aim to address these limitations by considering more types of corporate innovation measures and adding other emerging economies. These extensions will further deepen our understanding of the impact of corporate innovation in emerging economies from a managerial ownership perspective.

Authors’ contributions

Tingqian Pu: study conception, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and writing original draft. Abdul Hadi Zulkafli: theory, validation, methodology, revising it critically for intellectual content, supervision and project administration.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Collins G. Ntim (editor), and two anonymous reviewers for useful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tingqian Pu

Tingqian Pu is a Ph.D. candidate in Finance at the School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia. His research interests relate to international finance, corporate finance and innovation.

Abdul Hadi Zulkafli

Abdul Hadi Zulkafli is an Associate Professor of Finance at the Finance and Islamic Finance Section, School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia. He has a Master of Business Administration from the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and a Doctoral degree from Universiti Malaya, Malaysia. His research interests focus on corporate finance and corporate governance.

References

- Abernethy, M. A., & Brownell, P. (1997). Management control systems in research and development organizations: The role of accounting, behavior and personnel controls. Accounting Organizations and Society, 22(3–4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0361-3682(96)00038-4

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-d

- Azeem, M., Ahmed, M., Haider, S., & Sajjad, M. (2021). Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technology in Society, 66, 101635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101635

- Baer, M. (2012). Putting creativity to work: the implementation of creative ideas in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1102–1119. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0470

- Bai, G., Li, T., & Xu, P. (2023). Can analyst coverage enhance corporate innovation legitimacy?—Heterogeneity analysis based on different situational mechanisms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 405, 137048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137048

- Bessonova, E., & Gonchar, K. (2017). Incentives to innovate in response to competition: The role of agency costs. Economic Systems, 41(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2016.09.002

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Boadi, L. A., Isshaq, Z., & Idun, A. A. (2023). Board expertise and the relationship between bank risk governance and performance. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2283233

- Brick, I. E., Palmon, O., & Wald, J. K. (2006). CEO compensation, director compensation, and firm performance: Evidence of cronyism? Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2005.08.005

- Buck, T., Liu, X., & Skovoroda, R. (2008). Top executive pay and firm performance in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 833–850. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400386

- Cai, F., & Wen, Z. (2012). When demographic dividend disappears: Growth sustainability of China. In Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks, (, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137034298_5

- Campbell, E. M., Sittig, D. F., Ash, J. S., Guappone, K. P., & Dykstra, R. H. (2006). Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA, 13(5), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.m2042

- Cappelli, R., Corsino, M., Laursen, K., & Torrisi, S. (2023). Technological competition and patent strategy: Protecting innovation, preempting rivals and defending the freedom to operate. Research Policy, 52(6), 104785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104785

- Ceglowski, J., & Golub, S. S. (2012). Does China still have a labor cost advantage? Global Economy Journal, 12(3), 1850270. https://doi.org/10.1515/1524-5861.1874

- Cheng, H., Jia, R., Li, D., & Li, H. (2019). The rise of robots in China. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.2.71

- Chen, P., & Kim, S. (2023). The impact of digital transformation on innovation performance: The mediating role of innovation factors. Heliyon, 9(3), e13916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13916

- Chen, X., Liu, Z., & Zhu, Q. (2020). Reprint of “Performance evaluation of China’s high-tech innovation process :Analysis based on the innovation value chain. Technovation, 94-95, 102094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102094

- Chen, Y., Podolski, E. J., & Veeraraghavan, M. (2017). National culture and corporate innovation. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 43, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2017.04.006

- Chiesa, V. (1999). Technology development control styles in multinational corporations: a case study. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 16(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0923-4748(99)00005-3

- Chiesa, V., & Frattini, F. (2011). Commercializing technological innovation: Learning from failures in high-tech markets*. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(4), 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00818.x

- Choi, S. B., Lee, S. H., & Williams, C. (2011). Ownership and firm innovation in a transition economy: Evidence from China. Research Policy, 40(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.004

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian Corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1-2), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-405x(00)00067-2

- Coccia, M. (2016). Sources of technological innovation: Radical and incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firms. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 29(9), 1048–1061. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

- Cohen, L., Diether, K. B., & Malloy, C. J. (2013). Misvaluing innovation. Review of Financial Studies, 26(3), 635–666. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhs183

- Cosci, S., Meliciani, V., & Sabato, V. (2015). Relationship lending and innovation: empirical evidence on a sample of European firms. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 25(4), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2015.1062098

- Criscuolo, P., Dahlander, L., Grohsjean, T., & Salter, A. (2017). Evaluating novelty: The role of panels in the selection of R&D Projects. Academy of Management Journal, 60(2), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0861

- Demerjian, P.,Lev, B., &McVay, S. (2012). Quantifying managerial ability: A new measure and validity tests. Management Science, 58(7), 1229–1248. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1487

- Ding, N., Gu, L., & Peng, Y. (2022). Fintech, financial constraints and innovation: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 73, 102194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2022.102194

- Eriqat, I. O., Tahir, M., & Zulkafli, A. H. (2023). Do corporate governance mechanisms matter to the reputation of financial firms? Evidence of emerging markets. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2181187

- He, F., Yan, Y., Hao, J., & Wu, J. (2022). Retail investor attention and corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Energy Economics, 115, 106308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106308

- Higham, K., De Rassenfosse, G., & Jaffe, A. B. (2021). Patent quality: Towards a systematic framework for analysis and measurement. Research Policy, 50(4), 104215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104215

- Himmelberg, C. P., Hubbard, R. G., & Palia, D. (1999). Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 53(3), 353–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-405x(99)00025-2

- Hirshleifer, D., & Thakor, A. V. (1992). Managerial conservatism, project choice, and debt. Review of Financial Studies, 5(3), 437–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/5.3.437

- Holmstrom, B. (1989). Agency costs and innovation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 12(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(89)90025-5

- Hou, Q., Hu, M., & Yuan, Y. (2017). Corporate innovation and political connections in Chinese listed firms. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 46, 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2017.09.004

- Hsu, F., & Hsueh, C. (2009). Measuring relative efficiency of government-sponsored R&D projects: A three-stage approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 32(2), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.10.005

- Iqbal, N., Xu, J. F., Fareed, Z., Guang-Cai, W., & Ma, L. (2020). Financial leverage and corporate innovation in Chinese public-listed firms. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(1), 299–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2020-0161

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405x(76)90026-x

- Jia, N., Mao, X., & Yuan, R. (2019). Political connections and directors’ and officers’ liability insurance: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 58, 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.06.001

- Jiang, F., & Kim, K. (2020). Corporate governance in China: A survey*. Review of Finance, 24(4), 733–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfaa012

- Joe, D. Y., Oh, F. D., & Yoo, H. (2019). Foreign ownership and firm innovation: Evidence from Korea. Global Economic Review, 48(3), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2019.1632729

- Jun, L., & Wang, W. (2018). Managerial conservatism, board independence and corporate innovation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 48, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.10.016

- Kennedy, P. (1979). A guide to Econometrics. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA41729905

- Klafke, R., Picinin, C. T., Lages, A. R., & Pilatti, L. A. (2018). The development growth of China from its industrialization intensity. Cogent Business & Management, 5(1), 1438747. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1438747

- Krishnan, G. V., &Wang, C. (2015). The relation between managerial ability and audit fees and going concern opinions. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(3), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50985

- Lantz, J., & Sahut, J. (2005). R&D investment and the financial performance of technological firms. International Journal of Business, 10(3), 251. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-1060698231/r-d-investment-and-the-financial-performance-of-technological

- Laux, V., & Ray, K. (2020). Effects of accounting conservatism on investment efficiency and innovation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 70(1), 101319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2020.101319

- Liu, W., Liu, X., & Choi, T. (2022). Effects of supply chain quality event announcements on stock market reaction: an empirical study from China. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 43(2), 197–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-10-2021-0638

- Liu, G., & Lv, L. (2022). Government regulation on corporate compensation and innovation: Evidence from China’s minimum wage policy. Finance Research Letters, 50, 103272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103272

- Lo, H., & Shiah-Hou, S. (2022). The effect of CEO power on overinvestment. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 59(1), 23–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-022-01060-0

- Machokoto, M., Gyimah, D., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). Do peer firms influence innovation? The British Accounting Review, 53(5), 100988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2021.100988

- Markham, S. K., & Lee, H. (2013). Product development and management association’s 2012 comparative performance assessment study. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(3), 408–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12025

- McGuinness, P. B., Vieito, J. P., & Wang, M. (2017). The role of board gender and foreign ownership in the CSR performance of Chinese listed firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 42, 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.11.001

- Miguélez, E., & Moreno, R. (2015). Knowledge flows and the absorptive capacity of regions. Research Policy, 44(4), 833–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.01.016

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China. (2023). China’s manufacturing sector tops world for 13 years. The State Council Information Office of China. Retrieved September 18, 2023, from http://english.scio.gov.cn/pressroom/2023-03/02/content_85138877.htm

- Mochly‐Rosen, D., Grimes, K., Mohr, J. W., Immerglück, K., Egeler, E., Brown, J. S., Gaich, N., De Hostos, E. L., Hancock, G. R., Wang, M. K. H., Booth, R. F., Grant, J., Chen, L., Kjellson, N., Zaltzman, H., Kim, J., Walker, J. P., Mendelson, A., Boyd, P., & Reilly, C. M. (2023). Technology transfer and commercialization. In Springer eBooks, 185–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34724-5_5

- Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1988). Management ownership and market valuation. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405x(88)90048-7

- Nguyen, D. N., Tran, Q., & Truong, Q. (2021). The ownership concentration: Innovation Nexus: Evidence From SMEs around the world. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2020.1870954

- O’Connor, M. L., & Rafferty, M. (2012). Corporate governance and innovation. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 47(2), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002210901200004X

- Palia, D., & Lichtenberg, F. R. (1999). Managerial ownership and firm performance: A re-examination using productivity measurement. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5(4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0929-1199(99)00009-7

- Pepper, A. (2018). Agency theory and executive pay: The Remuneration Committee’s Dilemma. Springer.

- Rong, Z., Wu, X., & Boeing, P. (2017). The effect of institutional ownership on firm innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Research Policy, 46(9), 1533–1551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.013

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Salehi, M., Mahmoudabadi, M., & Adibian, M. S. (2018). The relationship between managerial entrenchment, earnings management and firm innovation. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67(9), 2089–2107. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2018-0097

- Shan, Y. G. (2019). Managerial ownership, board independence and firm performance. Accounting Research Journal, 32(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-09-2017-0149

- Sher, P. J., & Yang, P. (2005). The effects of innovative capabilities and R&D clustering on firm performance: the evidence of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. Technovation, 25(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-4972(03)00068-3

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1986). Large shareholders and corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 94(3, Part 1), 461–488. https://doi.org/10.1086/261385

- Tsai, K. (2005). R&D productivity and firm size: A nonlinear examination. Technovation, 25(7), 795–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2003.12.004

- Tushman, M. L., & Nadler, D. A. (1986). Organizing for innovation. California Management Review, 28(3), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165203

- Wang, Zhi.,Chen, M.-H.,Chin, C. L., &Zheng, Qi. (2017). Managerial ability, political connections, and fraudulent financial reporting in China. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 36(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2017.02.004

- Wang, B., Tao, F., Fang, X., Liu, C., Liu, Y., & Freiheit, T. (2021). Smart manufacturing and intelligent manufacturing: A comparative review. Engineering, 7(6), 738–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.07.017

- Wen, H., Zhong, Q., & Lee, C. (2022). Digitalization, competition strategy and corporate innovation: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing listed companies. International Review of Financial Analysis, 82, 102166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102166

- Yuan, R., & Wen, W. (2018). Managerial foreign experience and corporate innovation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 48, 752–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.12.015

- Zhang, R., Xiong, Z., Li, H., & Deng, B. (2022). Political connection heterogeneity and corporate innovation. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(3), 100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100224

- Zhang, M., Yu, F., & Zhong, C. (2022). How state ownership affects firm innovation performance: Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 59(5), 1390–1407. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2022.2137374

- Zhang, D., Zheng, W., & Ning, L. (2018). Does innovation facilitate firm survival? Evidence from Chinese high-tech firms. Economic Modelling, 75, 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.07.030

- Zheng, Q., Wang, X., & Bao, C. (2023). Enterprise R&D, manufacturing innovation and macroeconomic impact: An evaluation of China’s Policy. Journal of Policy Modeling, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2023.09.002

- Zhou, B., Li, Y., Sun, F., & Zhou, Z. (2021). Executive compensation incentives, risk level and corporate innovation. Emerging Markets Review, 47, 100798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2021.100798