Abstract

In recent years, some localities in Tunisia that are among the most amenable to agritourism have focused on the development of agritourism houses with a focus on rural women through agritourism entrepreneurial training. In this regard, the current study examines the influential determinants of entrepreneurial behavior using an agritourism method with rural Tunisian women. 167 of the study’s 235 rural Tunisian women participants were chosen using the Cochran algorithm. The findings suggest that rural women will have a strong desire to establish agritourism residence through a gradual process of changing norms towards the acceptance of rural women entrepreneurs as well as the acceptance of agritourism culture through the establishment of local and regional institutions and organizations in a context of family support with strong bonds of commitment, solidarity, environmental, and infrastructural foundations.

1. Introduction

For statesmen, scholars, and environmental defenders, food security, population growth, and environmental protection—particularly in developing nations with a conventional agricultural system—have become major concerns (Nosratabadi et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, many rural economic activities and income levels have drastically declined in recent decades, and the rise in the unemployment rate and the consequent exodus of the younger generation and highly educated individuals from villages have put the growth of rural areas at risk. In addition to facing natural challenges like global warming, a general trend toward drought, a decline in groundwater levels, and climate change, rural families are also facing unnatural challenges like a lack of knowledge about farm management, the exodus of young people from villages, and an aging village population (Khazami & Lackner, Citation2021).

As a result of endangering the livelihood of rural families, environmental sustainability has emerged as one of the major issues of the twenty-first century. The tourism sector has grown remarkably as an entrepreneurial sector in recent years. The numbers that are now available indicate that it accounts for 12% of the Gross National Product and about 9% of global exports. The combined 420 industries that make up the tourism sector bring in 1.7 trillion US dollars a year, making it the only industry in the world to have experienced proportionate growth in recent years (Bonye et al., Citation2020).

Regrettably, tourism has contributed to climate change and the depletion of resources (Khazami & Lackner, Citation2021). Agritourism is an alternative that supports local and national development (Bonye et al., Citation2020). Locals lead it and offer benefits for all (Lee, Citation2021). It also empowers women, especially in developing nations where they’re underrepresented in the tourism industry due to cultural norms (Alavion & Taghdisi, Citation2021).

Agritourism offers a great opportunity for rural women to showcase and sell their products, such as handicrafts, and become financially independent (Alavion & Taghdisi, Citation2021). The tourism industry has a higher proportion of female entrepreneurs compared to other sectors, particularly in South America (Surangi, Citation2022). It is important to support women’s issues to promote their development, growth, and economic potential, especially in poorer nations and rural areas where women often lack financial independence (Alemu et al., Citation2022; Paul et al., Citation2019).

Tourism is vital to Tunisia’s economy, contributing 14% to the GDP and providing jobs to around 400,000 people. It’s crucial to prioritize sustainable tourism and the needs of the local community. Women’s entrepreneurship drives economic growth in many countries, including Tunisia. The region has over 1,267 historically significant monuments, 230 natural attractions, and a hospitable ambiance, making it ideal for tourists (Paramashivaiah & Puttswamy, Citation2019). The settlements have a strong culture of hospitality that attracts hikers and visitors.

235 rural Tunisian women have completed agritourism training and are creating new businesses, such as handicraft production and agritourism. The study aims to identify factors that influence entrepreneurial behavior in agritourism, taking into account the significance of sustainable tourism and its role as a hidden economic force.

2. Literature review

2.1. Agritourism as a business opportunity for entrepreneurs

Agritourism is one of the rising industries in the village, and in addition to diversifying the economy, it attempts to stop the pressure that the tourism industry has had on natural resources and has significantly depleted the resources of nations (Saidmamatov et al., Citation2020). According to Swan and Morgan’s (Swan & Morgan, Citation2016) views, the concept of agritourism is defined as: nature-based, preservation/conservation, environmental education, sustainability, equitable distribution of benefits to the community, and ethically responsible action.

In many nations, the growth of agritourism has led to the creation of small and medium-sized businesses that have helped locals find work and enabled those with limited financial resources to engage in economic activity and earn a living (Khazami & Lackner, Citation2021); on the other hand, it has made significant contributions to protecting and conserving the environment (Swan & Morgan, Citation2016).

Since agritourism requires a culture of hospitality and friendliness in Tunisia because, from the perspective of locals, tourism in a rural setting is seen as a guest, agritourism lodges offer a relatively high level of employment for women in the fields of management and providing services to tourists, tour guides, cooking, catering, selling food products and local handicrafts, etc., which results in earning income and the increase in female labor force participation. The production of handicrafts, the processing of agricultural products, and animal husbandry provide the prerequisites for businesses such as agritourism to increase income and create stable markets in handicrafts. In the realm of agritourism businesses, women’s entrepreneurship has made remarkable strides in several countries. Recent data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reveals that in nations like India, Brazil, and Kenya, women comprise a substantial proportion of agritourism entrepreneurs, ranging from 25% to 35% of the total (World Bank - Women, Business, and the Law Citation2021, Citation2021). However, the World Bank’s Women, Business, and the Law 2021 report highlights persistent legal obstacles that impede women’s ability to fully participate in agritourism enterprises in these countries (World Bank - Women, Business, and the Law Citation2021, Citation2021). Despite these challenges, the tenacity of women entrepreneurs in agritourism is apparent, contributing not only to economic growth but also to sustainable development in rural areas (Abebe et al., Citation2023). Targeted support and efforts to overcome legal hurdles can further amplify the impact of women in agritourism across various geographical contexts (Abebe et al., Citation2023).

The current study seeks to identify the factors influencing the entrepreneurial behavior of agritourism among rural women in Tunisia.

2.2. Rural women’s entrepreneurial behavior factors

2.2.1. Entrepreneurial motivation

The notion of entrepreneurial intention refers to an individual’s firm resolve and determination to undertake a new business venture. It plays a crucial role in predicting and comprehending the complexities of entrepreneurship (Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023). Starting a new venture is not a simple impulsive decision, but rather a multifarious process that involves a plethora of factors that come into play. Among these factors, the driving force behind the entrepreneurial intention plays a paramount role in shaping and refining it. It encompasses a range of aspects, including the individual’s personal goals, motivation, knowledge, skills, and experience, as well as external factors such as market demand, competition, and availability of resources (Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023). Therefore, understanding the nuances of entrepreneurial intention is vital for aspiring entrepreneurs, policymakers, and researchers alike to facilitate the growth and success of new businesses.

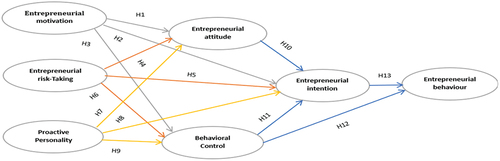

According to Carsrud and Brannback (Abebe et al., Citation2023), motivation is the factor that connects an entrepreneur’s objectives and deeds. These findings are supported by additional research that shows a connection between entrepreneur motivation and business performance, such as that done by Kuratko et al (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011). What the entrepreneurial impulses try to accomplish are the “entrepreneurial aims”. Kuratko et al. (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011) identified three categories of motivators: monetary rewards, independence and autonomy, and family safety. Lastly, there are four different incentives for starting a business: money, fame, freedom, and family tradition (such as the desire to carry on the family business) and to imitate family members. Entrepreneurship success may be influenced by motivating factors such as support from friends and family, abilities, and financial circumstances. As a result, the following theories were developed (Figure ):

Hypothesis 1.

Entrepreneurial motivation has a favorable and significant impact on the intention to start a business.

Hypothesis 2.

Entrepreneurial motivation has a favorable and significant impact on the perception of behavioral control.

Hypothesis 3.

Social motivation has a favorable and significant impact on behavioral attitude.

2.2.2. Entrepreneurial risk-taking

Entrepreneurial risk-taking is typically regarded in research as one of the traits of entrepreneurial behavior and, as a result, as one of the key influences on TPB structures. The risk that something unwanted could happen is defined broadly as a possibility. In this instance, various academics emphasized that since uncertainty plays a significant role in the entrepreneurial process, it is very crucial to be able to manage a perilous circumstance while selecting entrepreneurship. According to Roy et al (Kuratko & Hornsby, Citation1997), taking risks has an impact on entrepreneurial intention even though it does not directly change it.

Instead, the notion and knowledge that an entrepreneur is competent to manage difficult situations are referred to as taking risks. In other words, taking personal and financial risks is necessary for entrepreneurship, and those who tend to take more risks are more at ease in challenging circumstances (Kuratko & Hornsby, Citation1997). Another crucial personality feature that shows a person’s propensity to participate in a risky activity is a perception of risk. One of the dangerous events is considered to be entrepreneurship. According to research, those with a high-risk tolerance are more motivated to start their own businesses (Roy et al., Citation2017). As a result, the following theories were developed:

Hypothesis 4.

Propensity for taking risks has a favorable and significant impact on the intention to start a business.

Hypothesis 5.

Propensity for taking risks has a favorable and significant impact on the perception of behavioral control.

Hypothesis 6.

Propensity for taking risks has a favorable and significant impact on behavioral attitude.

2.2.3. Proactive personality

A proactive personality is regarded as one of the personality traits of successful entrepreneurs in the field of entrepreneurship, according to studies (Farrukh et al., Citation2018). Most occupational studies are connected to proactive conduct. The Proactive Personality (PP) index was developed by Crant in 1995 and is based on a person’s propensity to affect their surroundings and take various actions. The degree to which people are prepared to “take activities and impact their environment” is referred to by Crant (McClelland, Citation1987). According to the proactive personality trait, people are more eager to be independent and look for new chances and have greater autonomy in their profession.

Entrepreneurial awareness and the development of new entrepreneurial prospects are examples of proactive personality traits. Proactive personality traits are associated with a stronger ambition to start their own business (Crant, Citation1995). These led to the following hypotheses being developed:

Hypothesis 7.

Entrepreneurial intention is positively and significantly influenced by a proactive personality.

Hypothesis 8.

Entrepreneurial behavior is positively and significantly influenced by a proactive personality.

Hypothesis 9.

Perceived behavioral control is positively and significantly influenced by a proactive personality.

2.2.4. Behavioral attitude

According to Ajzen (Munir et al., Citation2019), who developed the theory of planned behavior, people’s attitudes toward entrepreneurial actions and anticipated successes should be able to predict whether or not they intend to start a business. The degree to which a person assesses the desirability of the goal behavior is referred to as their attitude toward entrepreneurship (Ajzen, Citation1991). While this attitude is a reflection of how people feel about possible entrepreneurial experiences, if people’s attitudes toward establishing a business change, so will their entrepreneurial purpose (Ajzen, Citation1991). In general, attitudes can be either positive or negative. According to prior research, the attitude has the biggest role in making someone desirable and beginning their entrepreneurial journey.

According to Ajzen’s theory, there is a correlation between entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial mindset that is favorable (Crant, Citation1995). There are several fields where the theory of rational behavior has been used. According to this idea, favorable attitudes act as predictors of behavioral intentions that influence people’s conduct. This theory and the literature on tourism both make clear how strongly attitudes, behavioral intentions, and ultimately behavior are correlated. Also, defining the mechanism for participation intention has increased locals’ participation in ecotourism management (Nowiåski et al., Citation2020). Locals appear to be more in favor of agritourism when they view its impacts favorably. Also, considering how the locals feel about agritourism is meant to be a need for their participation. In order to avoid the tension between the preservation of local resources and the economic development of the regions, which results in the fact that agritourism flows smoothly, planners can benefit from understanding the attitudes of the locals toward the principles of agritourism management (Nowiåski et al., Citation2020). The second hypothesis was created based on the justifications offered.

Hypothesis 10.

Entrepreneurial attitude has positively and significantly impacted entrepreneurial intention.

2.2.5. Perceived behavioral control

The apparent ease and challenge of carrying out a task are referred to as perceived behavioral control. In other words, the formation of behavior is influenced by prior experiences as well as by foreseeing difficulties and other factors. In other words, those who feel they have a high level of behavioral control have a stronger desire and intention to engage in behavior (Zhang & Lei, Citation2012). According to the idea of planned behavior, perceived behavioral control is the conviction that one will engage in planned conduct and the attitude that one has control over that behavior.

According to some academics, perceived behavioral control is a person’s perception of how easy or challenging it is to engage in entrepreneurial behavior (Crant, Citation1995). Also, the perceived behavioral control element has an impact on a person’s conduct as well as their entrepreneurial desire (Zhang & Lei, Citation2012). The following hypotheses were formed considering the justifications offered.

Hypothesis 11.

Entrepreneurial intention is positively and significantly influenced by perceived behavioral control toward entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 12.

Entrepreneurial behavior is positively and significantly impacted by perceived behavioral control toward entrepreneurship.

2.2.6. Behavioral intention

The level of an individual’s intention to engage in the desired behavior is indicated by their entrepreneurial intention, which serves as the starting point of their entrepreneurial journey (Lortie & Castogovianni, Citation2015). People frequently carry out the behaviors they want to carry out, as shown by the correlation between behavioral intention and conduct. In other words, the key predictor of entrepreneurial activity is entrepreneurial intention. Behavior is always followed by and related to behavioral intention (Ajzen, Citation1991). According to Ajzen (Munir et al., Citation2019), the intention is “a person’s desire to engage in conduct” (Ajzen, Citation1991). Entrepreneurs should be inspired because they are thought of as engaging in planned conduct. As a result, learning about entrepreneurship involves several stages, with the intention serving as the first level (Lortie & Castogovianni, Citation2015). The theory of planned behavior of intention (TPB conceptualization) includes three predictors: 1. Understanding the social pressure to perform or not execute a behavior (attitude), 2. Understanding the ease or difficulty of performing the task (perceived norm), and 3. Favorable or unfavorable judgment of the activity (perceived behavioral control).

More support for performing the behavior and, consequently, a stronger intention to engage in entrepreneurial behavior is produced by a more favorable assessment of the person’s willingness to engage in entrepreneurial behavior, how important the behavior is from others’ perspectives, and a person’s understanding of their capacity to carry out entrepreneurial activities (Lortie & Castogovianni, Citation2015).

The first theory was created considering this.

Hypothesis 13.

Rural women’s entrepreneurial intention is positively and significantly influenced by their entrepreneurial behavior.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Study area

Since 2011, Tunisia has been facing a turning point in its history. Indeed, the country has been engaged in a process of fundamental transformations in the political, economic, and social environment. Faced with this crisis, the tourism and agriculture sector merged to save the country and rebuild the Tunisian destination image. From this observation, a new notion appeared and encouraged the emergence of new businesses. Nowadays, in Tunisia, the concept of agritourism is a new sector that resorts to the development of rural areas and offers a variety of agritourism products and services. From a national perspective, dehydration and the factors that are destroying the pastures and lands, particularly because of human activities and constrained support policies of the government, have significantly impacted the productivity of agricultural and natural ecosystems, including agricultural lands, pastures, and forests. This destruction has made rural and nomadic households more vulnerable, which in turn has raised the demand for natural resources.

3.2. Methods

For more accurate evaluations of the hypotheses, a mixed method was employed. The major influencing aspects were identified using a qualitative approach, the results were improved, and the model’s specifics were checked using a quantitative approach. Grounded theory-based qualitative research has adopted a structured approach to methodology. Specifying the target category, doing comparative data analysis, sampling up to the theoretical saturation point, and finalizing and developing the model or paradigm are the primary steps of this methodology. As a supplement to the quantitative phase’s research instruments, the qualitative phase’s findings have been developed. The study’s conclusions can be used to design new programs for the Ministry of Agriculture’s rural women’s activities as well as to better the agri-business scenario for rural women in Tunisia.

3.2.1. Qualitative phase

In the first phase, the required data were collected using the grounded theory that includes a series of systematic procedures, sampling up to the stage of theoretical saturation, comparative analysis of data, defining the focal category, and completing and formulating the theory, to develop a theory about a phenomenon inductively. To analyze the data, the systematic grounded theory approach and the Strauss and Corbin paradigm model were used. According to the Strauss and Corbin (Mahfud & Gumantan, Citation2020) paradigm model, coding was performed in three stages with open, selective, and axial coding methods. Based on the principle of theoretical saturation, the statistical population of the qualitative phase was 15 experts of rural women entrepreneurs. Experts are people who have more than five years of experience in the field of rural women and have educational background and expertise as well as an expert opinion.

As a qualitative sample population: four different groups of experts were selected by purposive sampling to collect data. The first group was managers and experts of rural women’s agricultural development office, the second group was managers and experts of some rural regions, the third group was experts of other related organizations, and the fourth one was rural women entrepreneurs who had agritourism in Tunisia rural regions.

The data collection tool was semi-structured interviews and telephone conversations with the interviewees. The duration of each interview was about 30 min. In total, it took 18 days to conduct all the interviews. Incorporating a systematic approach into the grounded theory, we analyzed data in three steps with open, axial, and selective coding. The first step of the triple coding data analysis was open coding. It is an analytical process through which primarily concepts are identified, and their properties and aspects are explored. The next step was axial coding which is usually done according to the paradigm pattern. This pattern includes the main categories (phenomenon), conditions (causal, contextual, and intervening), and consequences. The third step was selective coding based on the results of the two previous steps. This step permits researchers to connect the core categories in the framework of a narrative.

Considering that rural women’s agritourism entrepreneurship is a new topic in Tunisia’s tourism industry, it has received much more attention in recent years. The data processing was performed with NVivo 8. Finally, the effective components of rural women’s entrepreneurial agritourism behavior in Tunisia were determined.

3.2.2. Quantitative phase

The total population size in the quantitative phase was 235 rural women from 6 villages in Tunisia who participated in the agritourism training program. The samples were selected by stratified random sampling. Using Cochran’s formula, the sample size was calculated as 167 individuals. Since the result is approximate, the researcher selected 167 people for the statistical sample. The main tool of data collection was a researcher-made questionnaire prepared based on the model developed in the qualitative phase and based on behavioral theories such as Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by experts’ opinions, and its reliability was confirmed by the range of the reliability coefficients (0.79–0.91).

According to this model, the dependent variable was entrepreneurial behavior with the agritourism approach of Tunisian rural women. The independent variables include attitude towards entrepreneurship in two dimensions; instrumental and affective, and perceived behavioral control in three dimensions: perceived difficulty, perceived trust, and perceived control. Entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial behavior, and personality characteristics of entrepreneurs include: risk-taking, proactive personality, and social motivation each factor consists of several items (Appendix A).

The items of the questionnaire were designed based on a five-point Likert scale (very low = 1, very high = 5). The structural Equation Modelling (SEM) technique was used to test the developed model and examine the relationships between its variables in order to finalize the model. Data processing and all statistical analyses in this phase were performed using SPSSV26 and SmartPLS3.0 software.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative phase

The first stage began following the initial interview and was completed using NVivo8. The researcher coded in two different approaches, using the interviewee’s words and concepts directly or basing them on the concepts found in the data (implicit codes).

Afterward, the researcher analyzed the framework of the paradigm model and drew the final theory using axial coding. With the creation of the primary categories, a multi-layer communication network was built between each category. The open coding’s categories, traits, and dimensions were collated and organized in order to create connections between them.

Selective coding is used by the researcher to connect the categories with one another and attempts to build a theory based on these relationships, which is actually the most important stage in theorizing. Strauss and Corbin’s paradigm (Mahfud & Gumantan, Citation2020) was applied as an analytical tool to determine the link between categories. In this sense, one category was chosen as the primary category, while the others were interrelated. Theoretical sampling was carried out to achieve theoretical saturation. In other words, the data from the new samples ensured that the theory was saturated in the 13th-person interview by repeating the prior codes. The interview went on until the 15th individual, but the results remained the same in order to retain the diversity of viewpoints. Triangulation was employed to assess reliability. The variables derived from the interviews and the findings were also given and improved upon by a number of specialists in the field of rural women’s agritourism entrepreneurship in order to confirm the interpretations.

4.2. Quantitative results

4.2.1. Personal and professional characteristics

The participants in the research sample ranged in age from 23 to 57, with an average age of 33. Of those included in the study, 73.3% were married and 26.7% were single. In terms of education, 43.2% held a diploma, 38.9% had a post-diploma, and 17.9% held a bachelor’s degree, indicating a majority had pursued higher education. Additionally, the statistical sample revealed that 57.3% of the participants were facilitators while 42.7% were not. It was also noted that 90.5% of the participants were members of rural women’s microcredit funds, highlighting their connection to rural areas and involvement in microcredit programs. The participants had completed an average of 7 training courses, with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 14 entrepreneurial courses. Furthermore, the sample completed an average of 4 courses of training in agritourism entrepreneurship, with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 6 courses. These findings suggest that the participants possessed specialized knowledge and skills that would be valuable in their entrepreneurial endeavors.

4.2.2. Structural equation

Various factors influence the behavior and intentions of agritourism entrepreneurs. As per research findings, entrepreneurial intention and behavioral control hold the most significant impact on agritourism entrepreneurial behavior. The path coefficients for these variables are 0.221 and 0.322, respectively, indicating that entrepreneurs are more likely to participate in agritourism activities when they intend to do so and have control over their behavior (Table ).

Table 1. Model paths result

Moreover, behavioral attitude and control also have a substantial influence on agritourism entrepreneurial intention. The path coefficients for these variables are 0.576 and 0.353, respectively, suggesting that having positive attitudes towards agritourism and feeling in control of their behavior in this area leads entrepreneurs to have an intention to engage in agritourism. The variable of social motivation is another crucial factor impacting entrepreneurial intention, with a path coefficient of 0.735, indicating that entrepreneurs are more likely to have an intention to engage in agritourism when they feel strong social motivation to do so. Finally, it is worth noting that agritourism entrepreneurial intention significantly affects entrepreneurial behavior in the field, with a path coefficient of 0.221, indicating that entrepreneurs who intend to engage in agritourism are more likely to do so.

Overall, the findings highlight the critical role that both internal and external factors play in determining agritourism entrepreneurial behavior. The structural equations below depict the relationship between the final dependent variable (agritourism entrepreneurial behavior) and the intermediate dependent variable (agritourism entrepreneurial intention).

5. Discussion

Entrepreneurship is a complex process that involves a conscious decision-making process and a focus on entrepreneurial behavior that precedes any action taken. This process is referred to as “entrepreneurial intention.” It serves as a foundation for identifying and seizing opportunities to launch a business. The theory of planned behavior suggests that the relationship between conduct and three predictors is determined by purpose (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998).

This means that the intention to start a business, the attitude toward starting a business, and the perceived behavioral control all play a role in the actual behavior of starting a business. In the context of rural women who are interested in starting an agritourism business, the findings of a recent study suggest that those who express an interest in launching such a venture are more likely to follow through with it. Therefore, it is important to identify and address the factors that affect the intention of rural women to create agritourism accommodations. Gender policies that recognize the potential of rural women in the administration of agritourism lodges provide a strong foundation for the development of the agritourism industry. These findings are consistent with previous research by Kreft et al (Hauslbauer et al., Citation2022), which highlights the need for ongoing agritourism business education and training programs aimed at fostering female entrepreneurs.

Such programs can help to increase the local level of entrepreneurial intent among rural women and provide them with the skills and knowledge necessary to launch and sustain successful agritourism businesses. It is worth noting that the findings of the study also suggest that residents perceive agritourism as a necessary component of their participation within the community. Therefore, the development of agritourism businesses can have a positive impact on the local community, creating jobs and generating income, while also preserving the local culture and environment.

Planning professionals can develop effective management strategies to lessen the conflict between the preservation of local resources and the economic development of the regions, which promotes the circulation of agritourism, by understanding residents’ attitudes toward the principles of agritourism management. So, if rural women entrepreneurs have a positive attitude toward the development of agritourism accommodations, they will enter the sector of agritourism.

The role of rural women in the development of agritourism lodgings cannot be overstated. Given the province’s immense tourism potential, high traffic of domestic and foreign tourists, favorable climate, and the rich culture and important traditions of rural and nomadic groups, it is no surprise that the growth of agritourism is largely attributed to the hard work and dedication of rural women entrepreneurs. To foster a positive attitude towards agritourism entrepreneurship, it is recommended that training sessions, educational workshops, and promotional visits to successful agritourism properties be arranged for interested rural women. Such activities would provide valuable opportunities for rural women to interact with other successful entrepreneurs and learn from their experiences, thereby enhancing their skills and knowledge in the field. These recommendations are based on the findings of a study conducted by Karimi and Saghaleini (Kreft et al., Citation2023), which showed that societal norms have a significant impact on rural women’s desire and intention to start their own agritourism businesses. Therefore, it is important to create an environment that encourages and supports rural women who aspire to become successful agritourism entrepreneurs. By doing so, we can ensure that rural women continue to play a vital role in the growth and development of agritourism in the province.

Entrepreneurial motivation among rural women is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by a variety of societal and cultural factors. The study found that the level of motivation plays a crucial role in shaping how individuals who start agritourism businesses are perceived by society. This is similar to how attitudes and perceptions are shaped by a person’s behavior and actions (Crant, Citation1995). The study also found that the entrepreneurial drive of women has a significant impact on their success in the agritourism industry, especially in Tunisia, which is renowned for its stunning natural landscapes and rich history. Tunisia is a popular destination for both domestic and foreign tourists, and the moral values of both urban and rural societies have created a welcoming environment for visitors.

The findings suggest that promoting and supporting successful agritourism businesses can help to showcase the personal and family values of the owners. This is particularly important in Tunisia, where family and community values are highly regarded. The study recommends that policymakers and stakeholders should consider providing more support to women who want to start agritourism businesses, as this can have a positive impact on both the local economy and the broader community.

In summary, the study highlights the importance of entrepreneurial motivation among rural women in the agritourism industry (Karimi & Saghaleini, Citation2021). It underscores the need for policymakers and stakeholders to provide more support for women who want to start businesses in this sector and showcases the potential benefits of a thriving agritourism industry to both the local community and the broader tourism sector.

The results of the study indicate that perceived behavioral control plays a critical role in shaping people’s behavior, their desire, and intention to start their own agritourism business. The concept of perceived behavioral control is defined as the perception of the ease and difficulty of conducting a particular behavior. Individuals’ attitudes towards behaviors are influenced by several factors, including their past experiences and their predictions of the challenges that may arise during the implementation of the behavior. Rural women play diverse roles in providing for their families, and they have always viewed empowerment and self-efficacy as essential components of their identities. They are also equipped with the basic skills of this culture, such as the ability to communicate in the local dialect, dress in traditional attire, and live in their own homes, as well as a welcoming culture.

The study recommends the provision of specialized agritourism entrepreneurship training, as well as workshops centered on personal development and psychological aspects of entrepreneurship. This approach is necessary because rural women’s various roles have resulted in a duty-oriented mentality that has led to their isolation from the rest of society. The research suggests that agritourism entrepreneurship training can help rural women gain the knowledge they need to set up a successful agritourism unit. By realizing the difficulties involved in setting up agritourism residences, rural women can identify opportunities to create side jobs and succeed in starting their own business. This conclusion is consistent with studies conducted by Ali and Youssef in (Bartha et al., Citation2019) and Hauslbaue et al. in (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). In summary, the study highlights the importance of perceived behavioral control in shaping people’s behavior towards entrepreneurship and the need for specialized training and workshops aimed at enhancing rural women’s entrepreneurial skills. Such an approach can help rural women break out of their isolation and contribute to the overall growth and development of their communities.

The study conducted revealed that the variable of risk-taking had a significant impact on the intentions of rural women when it comes to entrepreneurship in agritourism. In other words, rural women who have a greater willingness to take risks are more likely to pursue entrepreneurship opportunities in agritourism. It was also found that rural women perceive agritourism entrepreneurship as a form of social and group entrepreneurship, indicating that it is not just an individual endeavor but also involves the collaboration of others.

Furthermore, the study showed that building an accommodation for agritourism is a collaborative activity that requires the financial and spiritual support of the family. As such, it is recommended that rural families be targeted for both general and specialized agritourism entrepreneurship training. By grouping family members based on their roles and field of activity in an agritourism dwelling, family entrepreneurship can be formed, allowing for a more cohesive and effective business venture. These findings support the conclusions of previous studies, such as Farrukh et al (Roy et al., Citation2017), which demonstrated that taking risks has a favorable and significant impact on how rural women perceive their level of behavioral control concerning agritourism business ventures. While starting a business is often considered risky, those who have a high-risk tolerance exhibit greater behavioral restraint than those who do not.

In conclusion, the study emphasizes that agritourism is not just a commercial activity but also a sociocultural field that requires collaboration and support from family members. The results suggest that rural families should be treated as a target group for agritourism entrepreneurship training and that by grouping family members, their role and field of activity in an agritourism dwelling can be specified to form family entrepreneurship. The study provides valuable insights into the factors that influence the entrepreneurial intentions of rural women in the context of agritourism.

The study findings suggest that despite the challenges associated with agritourism, rural women who are willing to take calculated risks are better equipped to handle the difficulties and obstacles that come with setting up an agritourism lodging.

Therefore, it is essential to provide rigorous and comprehensive training on risk management while constructing an agritourism hostel to mitigate the potential risks associated with such ventures. The research conducted by Farrukh et al. (Roy et al., Citation2017) supports this study’s findings, which highlight the positive impact of risk-taking on people’s attitudes toward starting an agritourism business. In other words, rural women who possess the drive and ability to manage risks adequately are more likely to succeed in starting their own agritourism business. Furthermore, the study concludes that the desire to pursue agritourism is closely linked to one’s attitude towards the industry. Individuals who take calculated risks and possess adequate risk management skills are more likely to succeed in starting their own agritourism business.

Furthermore, the study concludes that the desire to pursue agritourism is closely linked to one’s attitude towards the industry. Individuals who take calculated risks and possess adequate risk management skills are more likely to venture into the agritourism sector and create their agritourism lodging. Thus, it is essential to create more opportunities for rural women to learn risk management skills and develop the necessary mindset to pursue entrepreneurship in the agritourism sector.

To support rural women who have established agritourism residences, it is recommended that they hold regular weekly or monthly meetings to discuss and analyze the potential risks involved in their business. These meetings will provide a platform for rural women to express their thoughts and concerns about the risks they face, and to share their experiences and insights. By doing so, they can positively influence the mindset of other rural women entrepreneurs and help them make informed decisions about risk management. This suggestion aligns with the research findings of Gurel et al. (Ali & Yousef, Citation2019) and Aghdasi et al (Ağbulut et al., Citation2021), who also emphasized the importance of regular meetings in promoting risk acceptance and effective risk management among rural women entrepreneurs.

The study conducted by McClelland (Farrukh et al., Citation2018) highlights the crucial role of proactive personality traits in successful entrepreneurship. However, when it comes to rural women in Tunisia and their entrepreneurial ambitions in the agritourism sector, the findings suggest that this trait may not have a significant impact. The research focused specifically on the impact of proactive personality on rural Tunisian women’s entrepreneurial aspirations in agritourism. Despite the general belief that proactive personality traits are vital for entrepreneurial success, the study’s results indicate that this trait did not noticeably influence the participants’ goals. Overall, while proactive personality is widely acknowledged as an essential factor in entrepreneurial success, this study’s findings suggest that it may not be as critical in certain contexts, such as rural Tunisia and the agritourism industry.

Based on the cultural and environmental factors prevalent in certain regions, particularly in rural areas, it has been observed that the proactive personality trait may not significantly impact individuals’ desire to establish an agritourism residence. This is due to the patriarchal societal norms and the preference of rural women to adhere to traditional roles, such as being a wife, mother, and agricultural worker. Despite their proactive personality trait, these factors may prevent individuals from pursuing agritourism as a viable business option. These observations contradict the Munir et al. study (Crant, Citation1995) and suggest that there is a need to address the cultural and environmental factors hindering entrepreneurship in rural areas.

The study examined the effect of the proactive personality trait on the entrepreneurial attitudes of rural women toward building an agritourism dwelling. The results showed that having a proactive personality among rural women does not have a significant and favorable influence on their desire to start their own agritourism business. This implies that the proactive personality trait is not a reliable predictor of entrepreneurial attitudes among rural women. To develop entrepreneurial skills among rural women, the study recommends providing basic entrepreneurship training that focuses on the mentality and skills of an entrepreneur. This educational program should be implemented for teenage girls to instill entrepreneurship characteristics in them at a young age. The findings suggest that such training could help to build entrepreneurial skills and attitudes among rural women, which could lead to more successful agritourism businesses. It is worth noting that these findings conflict with the conclusions of Wiklund et al.‘s study (Aghdasi et al., Citation2023). This indicates that further research is needed to determine the factors that influence the entrepreneurial attitudes of rural women toward building an agritourism dwelling.

The results of the study showed that the proactive personality trait did not have a significant influence on the behavior of rural women toward the agritourism business. The proactive personality trait is characterized by a tendency to be more autonomous and self-directed in one’s professional life, including being aware of entrepreneurial opportunities and exploring new prospects. However, this finding is in contrast to the results of Neneh’s research (Wiklund et al., Citation2019). The lack of a significant impact of proactive personality traits on rural women’s behavior towards the agritourism business suggests that other factors may play a more crucial role in shaping their behavior. It is possible that cultural and social factors, such as traditional gender roles and community norms, may have a more significant influence on rural women’s engagement in entrepreneurial activities (Neneh, Citation2019). Further research is needed to explore these factors and their impact on rural women’s entrepreneurial behavior in agritourism.

5.1. Implications of the study

Rural businesses have the potential to play an essential role in eliminating poverty and empowering women in developing economies. However, despite the increasing number of organizations dedicated to supporting rural development, women entrepreneurs still face significant challenges in accessing the financing necessary for their businesses to grow. Studies have shown that investing in women entrepreneurs is the most effective way to improve family health, hygiene, nutrition, education, and society. Rural women entrepreneurs are known for their risk-taking, hard work, and dedication to making a positive impact in their communities. Unfortunately, they often face multiple obstacles, including a lack of access to credit, training, and resources.

To address these challenges, formal government policies are necessary to create a supportive environment that provides women entrepreneurs with access to resources such as business feasibility assessments, legal advice, and training on financial literacy, business management, marketing, and product development. Access to information and support can help women entrepreneurs overcome these challenges and develop the skills they need to run their businesses more effectively. Additionally, partnerships with private sector and non-governmental organizations can provide women entrepreneurs with access to markets, technology, and networks, enabling them to expand their businesses and reach new customers.

In conclusion, by investing in women entrepreneurs, we can contribute to the economic growth and development of rural areas. Formal government policies and partnerships with private sector and non-governmental organizations can create a supportive environment that empowers women entrepreneurs to make a positive impact in their communities and beyond.

5.2. Limitations and suggestions for future research

The research study offered insightful information on the initial research question. However, there are a few limitations that need to be taken into account. The following are some of the limitations and recommendations for future research. Furthermore, several future research topics have been proposed to build on this study.

Firstly, the study utilized a cross-sectional design, which only captures a snapshot in time. As a result, future research should implement a longitudinal survey design to track changes over time. A larger sample size is necessary to represent a more diverse group of women entrepreneurs in rural areas and a broader geographic range. This would result in more robust and comprehensive findings.

Secondly, the study focused solely on certain variables, such as entrepreneurial motivation, risk-taking, and proactive personality, that influence the behavioral attitude of women’s entrepreneurship. However, other factors contribute to the development of women’s entrepreneurial intent. Researchers must identify these factors to have a more comprehensive approach to supporting female-led businesses. Additionally, self-reported data can be biased due to social pressure, leading to inaccurate results. Researchers can minimize this bias by incorporating other data collection methods.

Although the study achieved an adequate sample size, it’s worth noting that larger sample sizes yield more dependable results. A larger sample size can also help identify subgroups of women entrepreneurs who may have different needs and challenges. Researchers should consider this when designing future studies.

6. Conclusions

The primary objective of this research is to explore how certain entrepreneurial factors impact the agritourism entrepreneurial behavior of rural women in Tunisia. The study aims to provide a conceptual model that connects various concepts that have not been previously addressed together. In particular, this research will examine the unique environment of agritourism and explore how various factors interact to influence entrepreneurial behavior in this context.

By combining these theoretical notions, this study aims to better predict the behavior of entrepreneurs who are facing difficulties in establishing a firm and positioning it favorably against competitors. The goal is to identify which factors play a significant and positive role in promoting agritourism entrepreneurial behavior among rural women in Tunisia. Some of the factors that will be examined include access to resources, including financial, social, and human capital, as well as the role of personal characteristics, such as motivation, creativity, and risk-taking propensity. The study will also explore the effects of institutional and environmental factors, such as government policies, social norms, and cultural values.

The research problem that this study seeks to address is, “What factors have a significant and positive impact on the agritourism entrepreneurial behavior of rural women in Tunisia?” By exploring this question in detail, this study aims to provide valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities faced by rural women entrepreneurs in the agritourism sector in Tunisia.

Agritourism is a form of tourism that allows visitors to experience rural areas through activities related to agriculture. It is a unique way to connect with nature and learn about the local culture while participating in farming activities. The concept of agritourism is built on the participation of the host family members, who play an important role in the activities. In many historical rural areas, agritourism residences are managed by women entrepreneurs. These residences provide tourists with a chance to explore the village’s natural resources while promoting sustainable exploitation of the village attractions. Meanwhile, they also provide income and employment for women and other members of the local community, which helps prevent migration to cities. Agritourism can be defined as a collaborative effort between statesmen, the tourism industry, and local people. It is an opportunity for tourists to travel to untouched areas and enjoy nature and the native culture without damaging existing resources.

Agritourism provides a way to study and learn about the local culture while preserving the natural environment. In Tunisia, agritourism and rural tourism have been identified as solutions to the challenges of rural development and improving living conditions for villagers. Entrepreneurship is used in agritourism, and it even replaces traditional agricultural activities in certain villages targeted for tourism. This approach has helped promote rural development by providing local communities with favorable living conditions and opportunities for income and employment.

Our research was conducted to gain a comprehensive understanding of the entrepreneurial behavior of rural women in Tunisia, with a particular focus on the factors that influence this behavior. To achieve this, we utilized both qualitative and quantitative data, which allowed us to explore the topic from multiple perspectives.

Through our study, we discovered that the entrepreneurial behavior of rural women is influenced by a complex interplay of external and internal factors. Family support was found to be a crucial factor, with many rural women relying on their families for emotional and financial support when starting and running agritourism businesses. Additionally, personal capabilities, such as knowledge, skills, and experience, were identified as important factors that enable rural women to successfully engage in entrepreneurship.

We also found that institutional support plays a vital role in the entrepreneurial behavior of rural women. Access to financing, training, and other resources were all found to be important factors that can help rural women overcome the challenges associated with starting and growing agritourism businesses. In terms of the enabling environment for agritourism, our study revealed that a range of climatic, cultural, social, and economic conditions can significantly influence entrepreneurial behavior among rural women. For example, the availability of natural resources, cultural traditions that support agritourism, and a supportive local community can all facilitate the success of agritourism businesses run by rural women.

Finally, we identified a variety of interventions that can be utilized to promote entrepreneurial activities among rural women engaged in agritourism. These include training programs that focus on business development and marketing, networking opportunities that allow rural women to connect with other entrepreneurs, and access to financing and other resources that are crucial for the growth and sustainability of agritourism businesses.

In the quantitative phase of our study, we found that several variables were important predictors of entrepreneurial behavior among rural women. Attitude, intention, behavioral control, risk-taking, social motivation, and proactive personality were all found to be significant factors that influence entrepreneurial behavior. Our findings suggest that interventions that target these variables may be particularly effective in promoting entrepreneurial behavior among rural women in Tunisia.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, N.K.; methodology, N.K.; validation, A.N., A.Y.; investigation, N.K.; data analysis, N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K.; visualization, A.N., A.Y.; supervision, A.N., A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ayoub Nefzi

Ayoub Nefzi is Professor of Marketing. His research focuses on themes related to tourism marketing, medical marketing, services marketing, children’s behavior, quality, entrepreneurship and knowledge management.

References

- Abebe, A., Kegne, M., Abebe, A., & Kegne, M. (2023). The role of microfinance on women’s entrepreneurship development in Western Ethiopia evidence from a structural equation modeling: Non-financial service is the way forward. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2256079

- Ağbulut, U., Ceylan, I., Gürel, E., & Ergün, A. (2021). The history of greenhouse gas emissions and relation with the nuclear energy policy for Turkey. International Journal of Ambient Energy, 42(12), 1447–1455. https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2018.1563818

- Aghdasi, S., Omidi Najafabadi, M., & Farajollah Hosseini, S. (2023, February 28). Rural women and ecotourism: Modelling entrepreneurial behavior in Iran. https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-2582002/v1/2f8bc1fa-e8f1-4cce-9de5-58ab8636b5b4.pdf?c=1676471166

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alavion, J., & Taghdisi, A. (2021). Rural E-marketing in Iran; modeling villagers’ intention and clustering rural regions. Information Processing in Agriculture, 8(1), 105–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2020.02.008

- Alemu, A., Woltamo, T., & Abuto, A. (2022). Determinants of women participation in income generating activities: Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00260-1

- Ali, A., & Yousef, S. (2019). Social capital and entrepreneurial intention: Empirical evidence from rural community of Pakistan. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0193-z

- Barba-Sanchez, V. Mitre-Aranda, M. & Del Brío-Gonzalez, J.(2022). The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100184

- Bartha, Z., Gubik, A., & Bereczk, A. (2019). The social dimension of the entrepreneurial motivation in the central and eastern European countries. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 7(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2019.070101

- Bonye, Z., Yiridomoh, Y., & Dayo, F. (2020). Do ecotourism sites enhance rural development in Ghana? Evidence from the Wechiau community Hippo Sanctuary Project in the Upper West region, WA, Ghana. Journal of Ecotourism, 21(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2021.1922423

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.x

- Crant, M. (1995). The proactive personality scale and objective job performance among real estate agents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(4), 532–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.4.532

- Farrukh, M., Alzubi, Y., Shahzad, A., Waheed, A., & Kanwal, N. (2018). Entrepreneurship intention: The role of personality traits in perspective of theory of planned behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(3), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-01-2018-0004

- Gieure, C., Benavides-Espinosa, M. D. M., & Roig-Dobón, S. (2020). The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research, 112, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.088

- Hauslbauer, A., Schade, J., Drexler, C., & Petzoldt, T. (2022). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict and nudge toward the subscription to a public transport ticket. European Transport Research Review, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-022-00528-3

- Karimi, S., & Saghaleini, A. (2021). Factors influencing ranchers’ intentions to conserve rangelands through an extended theory of planned behavior. Global Ecology and Conservation, 26, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01513

- Khazami, N., & Lackner, Z. (2021). Influence of social capital, social motivation and functional competencies of entrepreneurs on agritourism business: Rural lodges. Sustainability, 13(15), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158641

- Kreft, J., Boguszewicz-Kreft, M., & Hliebovac, D. (2023). Under the fire of disinformation. Attitudes towards fake news in the Ukrainian Frozen war. Journalism Practice, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2023.2168209

- Kuratko, D., & Hornsby, J. (1997). An examination of owner’s goals in sustaining entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(1), 24–33 .

- Lee, J. (2021). Using Q methodology to analyze stakeholders’ interests in the establishment of ecotourism facilities: The case of Seocheon, Korea. Journal of Ecotourism, 20(3), 282–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2021.1883626

- Lortie, J., & Castogovianni, J. (2015). The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 11(4), 935–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0358-3

- Mahfud, I., & Gumantan, A. (2020). Survey of Student anxiety levels during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Journal Pendidikan, Jasmani, Olahraga dan Kesehat, 4(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.33503/jp.jok.v4i1.1103

- Martínez-Cañas, R., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Jiménez-Moreno, J. J., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2023). Push versus pull motivations in entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 29(2), 100214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2023.100214

- McClelland, D. (1987). Characteristics of successful entrepreneurs. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 21(3), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1987.tb00479.x

- Munir, H., Jian Feng, C., & Ramzan, S. (2019). Personality traits and theory of planned behavior comparison of entrepreneurial intentions between an emerging economy and a developing country. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(3), 554–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-05-2018-0336

- Neneh, B. (2019). From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.04.005

- Nosratabadi, S., Khazami, N., Ben Abdallah, M., Lakner, Z., Band, S., Mosavi, A., & Mako, C. (2020). Social capital Contributions to food security: A comprehensive literature Review. FOODS, 9(11), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9111650

- Nowiåski, W., Haddoud, Y., Wach, K., & Schaefer, R. (2020). Perceived public support and entrepreneurship attitudes: A little reciprocity can go a long way! Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103474

- Paramashivaiah, P. & Puttswamy, P. (2019). Determinants of entrepreneurial behaviour of rural women Farmers in dairying: An empirical study. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(5), 31–40.

- Paul, R., Mohajan, B., Uddin, M., & Reyad, H. (2019). Factors affecting women participation in local government institution: A case study of Bangladesh perspective. Journal of Global Research in Education and Social Science, 13(3), 94–105.

- Roy, T., Shukla, R., & Bhat, A. (2017). Risk-taking during feeding: Between- and within-population variation and repeatability across contexts among wild zebrafish. ZEBRAFISH, 14(5), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1089/zeb.2017.1442

- Saidmamatov, O., Mat Yakubov, U., Rudenko, I., Filimonau, V., Day, J., & Luthe, T. (2020). Employing ecotourism opportunities for sustainability in the Aral Sea region: Prospects and challenges. Sustainability, 12(21), 9249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219249

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. American Psychological Association.

- Surangi, H. (2022). A critical analysis of the networking experiences of female entrepreneurs: A study based on the small business tourism sector in Sri Lanka. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00255-y

- Swan, D., & Morgan, D. (2016). Who wants to be an eco-entrepreneur? Identifying entrepreneurial types and practices in ecotourism businesses. The International Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 17(2), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750316648580

- Tu, B., Bhowmik, R., Hasan, M. K., Asheq, A. A., Rahaman, M. A., & Chen, X. (2021). Graduate students' behavioral intention of toward social entrepreneurship: Role of social Vision, innovativeness, social proactiveness, and risk taking. Sustainability, 13(11), 6386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116386

- Wiklund, J., Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., Foo, M., & Bradley, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.01.002

- World Bank - Women, Business, and the Law 2021. (2021). International Bank for Reconstruction and development. The World Bank.

- Zhang, H., & Lei, S. (2012). A structural model of residents’ intention to participate in ecotourism: The case of a wetland community. Tourism Management, 33(4), 916–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.012

Appendix A

Table A1. Item of all constructs