?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Previous studies on green bonds (GBs) in China have not extensively analyzed how investor characteristics such as demographic background and environmental concerns affect Chinese investors’ decisions to invest in GBs. Therefore, these aspects should be examined to understand the GB market and its potential expansion. To address this gap, this study analyzed how Chinese institutional investors’ social attributes, environmental concerns, and residential locations affect their decisions to purchase GBs. The ordered-probit model estimation revealed that experience in investing in GBs and high environmental awareness lowers the yield required for institutional investors to invest in GBs, suggesting that these factors increase investors’ willingness to pay (WTP) for GBs. The study also finds that investors in Shanghai have a higher WTP for GBs than those in Beijing and Shenzhen. The results provide important insights for the government and financial authorities to implement measures aimed at increasing institutional investors’ interest in the environment. Additionally, these results can drive GB issuers to promote sales to institutional investors with an environmental focus.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of reforms in late 1978 (Zhou et al., Citation2004), China’s rapid urbanization and significant economic growth have made it the world’s largest emitter of CO2. Hence, securing funds for environmental protection, which is urgently needed to reduce emissions, is crucial for achieving environmental conservation (Jiguang & Zhiqun, Citation2011; Pham et al., Citation2021). In 2016, seven ministries and financial regulators jointly issued “the Guidelines for Establishing a Green Financial System” (Larsen, Citation2022). At the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2017, President Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of establishing a market-driven innovation system for green technology and elevated the development of green finance, energy-saving, environmental protection industries, clean production, and energy industries to a national strategic level (Chen et al., Citation2023). To address the challenges of climate change, as in many countries worldwide, sustainable and green finance is gaining attention (Banga, Citation2019; Du & Wang, Citation2023; Gianfrate & Peri, Citation2019).

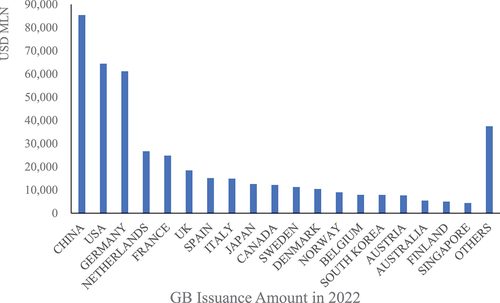

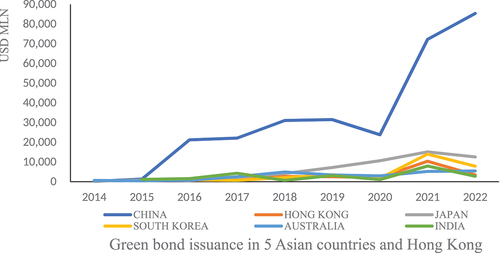

In green finance, China focuses on issuing green bonds (GBs) (Li et al., Citation2022), which originated from the climate awareness bond issued by the European Investment Bank in 2007. For many years, the definition of GBs in China has been unclear, and the prevention of greenwashing has been a challenge. However, in 2021, the PBOC revised the catalog as the “Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue (2021 Edition),” aiming to address the challenges by eliminating gray areas and clearly distinguishing transition projects from green projects and further growth of the GB market expected in China (People’s Bank of China PBOC, Citation2021). Climate Bond Initiative (CBI) reports the issuance of GBs has expanded globally, recording $442.0 billion at the end of 2022 after it reached $551.0 billion by the end of 2021 (Climate Bond Initiative CBI, Citation2023), China’s GB issuance has grown from less than $4 billion in 2016 to $85.3 billion in 2022, thereby, China has overtaken the U.S. to become the world’s largest GB issuer for the first time, as shown in Figure China’s increase in issuance volume is prominent among Asian countries (Figure ).

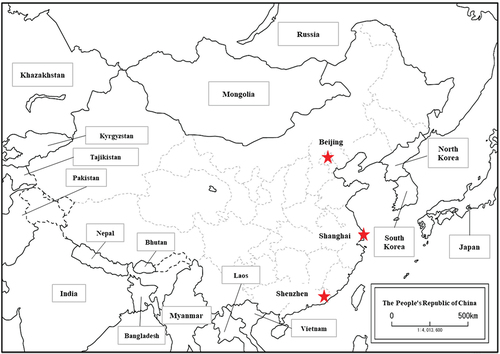

We chose Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen as the study locations, as shown in Figure . The choice was based on the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI) published by the Z/Yen Group, a London-based think tank, and the China Development Institute (CDI), a think tank in Shenzhen. According to the latest edition of the GFCI, Shanghai is ranked 7th in the world, Shenzhen is ranked 12th, and Beijing is ranked 13th, making it the third, fourth, and fifth largest financial centers in Asia, respectively, following Hong Kong and Singapore (Z/YEN Group Limited, Citation2023). These three financial centers have received significant support from the Chinese government and financial authorities as part of their national policy to establish themselves as leading financial hubs in Asia (Chen & Chen, Citation2015; Pan & Yang, Citation2019).

This study introduces as explanatory variables factors that have not been evaluated before, such as sociodemographic attributes, environmental awareness, and residential location of institutional investors. The analysis will assess how these factors affect institutional investors’ GB investments by examining the dependent variable, greenium. Thus, the research question of this paper is to ascertain whether attributes such as gender, age, degree of environmental concern, and place of residence of Chinese institutional investors affect their investment in GBs. The ultimate goal of this study is to identify the factors that influence GB investment by Chinese institutional investors, and based on the results, to promote the expansion of the GB market in China and to promote environmental protection.

The primary aim of this study is to foster the expansion of China’s GB market and contribute to environmental protection by elucidating the factors that impact GB investments made by Chinese institutional investors. A key motivating factor for this study is the imperative to further develop the GB market, a facet of sustainable finance, to serve as a means of sourcing funds for environmental preservation in light of the global climate crisis. This is crucial due to the sustainable growth of the GB market in China, the world’s largest CO2 emitter, being of utmost importance for global environmental conservation.

Previous studies on GBs in China have primarily used matching methods to calculate greenium based on historical trading data. However, these studies have not explored greenium from the perspective of institutional investors, the primary fund providers. The underlying theoretical and empirical motivation for this paper is to bridge this gap. In particular, this study examines the following attributes of institutional investors: gender, age, investment experience, investment position limit, as well as the degree of environmental concern and place of residence.

We refer to Al-Tamimi and Kalli Bin (Citation2009) for gender, Korniotis and Kumar (Citation2011) for age, Gambetti and Giusberti (Citation2019) for investment experience, and Irwin and Sanders (Citation2011), along with Aruga (Citation2022), for the degree of environmental concern, and Chen et al. (Citation2011) for place of residence. To achieve this, we conducted a direct questionnaire survey among Chinese institutional investors to understand greenium from their viewpoint and, consequently, to contribute to the further expansion of the Chinese GB market.

Consequently, the current paper seeks to make the following contributions to the existing literature. First, this paper is notable for being the first study to analyze whether the attributes of institutional investors have influenced the greenium. By incorporating the element of institutional investor attributes into the research on GBs, this paper demonstrates a significant contribution to prior research by analyzing how institutional investor attributes, their level of environmental concern, and their residential location impact GB investments. Second, this paper employs the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) to measure market value in the field of environmental economics. There have been few studies, such as Zenno and Aruga (Citation2022), in the past that employed CVM to calculate the greenium, making this analysis a valuable addition to the body of research on GBs. Third, this paper specifically concentrates on China’s GB market, which is the world’s largest CO2-emitting country. This research contributes to the breadth of GB research in China. Given that global environmental conservation heavily depends on China’s efforts in this area, this study can play a significant role in securing the necessary funding for China’s environmental conservation endeavors.

The greenium analysis conducted in this study examines the impact of institutional investors on GB investments by analyzing the yield spread between conventional bonds and GBs, representing the difference in the two yields. In this study, the benchmark for conventional bond yields is based on the yields of China’s 10-year government bonds and the 10-year conventional bonds issued by the China Development Bank, China’s largest GB issuer.

This study is structured as follows: Section 2 provides the paper’s background, explaining the rationale behind conducting this study. In the subsequent Section 3, we outline the theoretical framework underpinning the analysis. Section 4 delves into the literature review, elucidating the hypotheses formulated based on the review. In Section 5, we introduce the research design, encompassing a description of the variables utilized in this analysis and the methodology employed. Section 6 encompasses the presentation of empirical findings within this analysis. Finally, in Section 7, we summarize the results, contributions, and implications presented in this paper and offer our concluding remarks.

2. Background

2.1. Background of the Chinese bond market and environmental policies

Government and financial authorities primarily drove the establishment of the Chinese bond market (He & Wei, Citation2023). Traditionally in China, corporate fundraising relied heavily on bank loans, with a limited share of direct finance. Recognizing the need to diversify funding methods for entities such as national and local governments and corporations, China’s financial authorities concentrated on developing the Chinese bond market. In 1981, the Chinese Ministry of Finance issued the first long-term Treasury Bond, and in 1987, the Chinese government established the “Regulatory Guidelines of Enterprise Bonds,” laying the groundwork for corporate bond issuance. This acted as a catalyst, with active support for corporate bond issuance from the PBOC, the Ministry of Finance, and the National Development and Reform Commission (Amstad & He, Citation2019).

China’s bond market transactions are conducted in both the interbank market and on exchanges. According to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) (Citation2023), 86.5% of bond transactions take place in the interbank market, with the remaining 13.5% traded on exchanges. The composition of institutional trading in the interbank market, representing the majority of China’s bond market, is outlined in Table .

Table 1. Summary of the China interbank bond market transaction amount in 2022

China’s environmental policies have been primarily executed through a top-down approach led by the government and relevant authorities (Saravade et al., Citation2023). The integration of environmental protection as a national policy commenced with Vice Premier Li Peng’s declaration during the 1983 Second National Environmental Protection Conference, designating environmental protection as a national priority. In light of this, the Chinese government and State Council took assertive measures to advance environmental enhancements. The establishment of the Environmental Protection Commission within the State Council occurred in 1984, and the third National Environmental Protection Conference convened in 1989, ultimately resulting in the enactment of the “Environmental Protection Law.” Notably, the 12th Five-Year Plan in 2011 included the objective of “pursuing cleaner and more efficient development.” Subsequently, during the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October 2017, environmental protection in China was elevated to the status of one of the three major policy pillars.

2.2. Background of the Chinese GB market

As the underdeveloped bond market expanded, and the country’s environmental conditions worsened due to economic growth, the Chinese government took proactive measures to address these issues, including the growth of the GB market (Liu et al., Citation2022). . China initiated the issuance and establishment of the GB market as a means to finance environmental improvements in 2014. According to Yang (Citation2018), the world’s first Renminbi-denominated GB was issued by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 2014. Carbon bonds were also issued in China in the same year. In April 2015, the Green Finance Committee (GFC) was established in Beijing, and in October 2015, the Agricultural Bank of China issued GBs in the London market. In 2015, the PBOC introduced the “Green Bond Guidelines” and “Eligible Green Bond Projects,” contributing to the development of the Chinese GB market. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) further formulated the “Guidelines for the Issuance of Green Bonds,” and the “China Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue (2015 Edition) “was introduced by the Green Finance Committee of the China Society for Finance and Banking. Consequently, the Chinese GB bond market witnessed steady expansion.

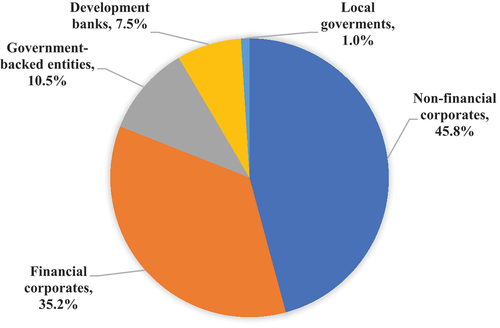

Regarding Chinese GB issuers, based on Climate Bond Initiative (CBI) (Citation2022), the composition is illustrated in Figure Non-financial corporates comprised the largest group at 45.8%, with financial corporates following at 35.2%.

2.3. Challenges in research on the Chinese GB market

Previous research on Chinese GBs initially focused on analyzing the entire GB market. However, since the analysis by Zerbib (Citation2016), research has increasingly emphasized the analysis of “greenium,” as seen in works like Wang et al. (Citation2020) using matching methods. Nonetheless, these analyses are primarily based on historical data and do not adequately consider the perspectives of market participants, particularly investors who provide funds for green projects.

Deschryver and De Mariz (Citation2020) conducted interviews to focus on the awareness of market stakeholders and identified challenges in the GB market from the perspectives of issuers, investors, and intermediaries. However, their interviews were conducted with only a total of 11 issuers, investors, and intermediaries, indicating a sample size limitation. Given the existing supply-demand gap in the GB market, it is essential to explore how to increase supply. This requires not only understanding the issuer’s perspective but also conveying the views of investors, who are key contributors to funding green projects.

While previous research has involved extensive analysis, there remains a paucity of studies grounded in the real-world perspectives of market participants, encompassing both issuers and investors. Flammer (Citation2021) is an example of a study that touches on investor perspectives but does not solely focus on investors. Piñeiro-Chousa et al. (Citation2021) examined the impact of investor sentiment on the green bond market using financial and social network data. However, the data utilized in the analysis did not originate from direct interviews with investors featuring explicit questions. As of the available literature, there is a dearth of research on Chinese GBs from the investor perspective. Understanding what issuers and investors seek, especially from high-demand investors, is crucial. Considering the unique regulatory and policy backdrop of the Chinese GB market, addressing these challenges is vital. Therefore, this paper focuses on analyzing the Chinese GB market with a specific emphasis on investor behavior and aims to provide the results to the government and relevant authorities as a valuable contribution.

3. Theoretical framework

3.1. Theoretical literature review

To perform the greenium analysis in this article, it is essential to examine the research methodologies utilized in previous studies for greenium analysis. Furthermore, previous studies have incorporated various explanatory variables into the greenium calculation, and it is essential to identify which specific explanatory variables were employed. To perform the analysis of greenium in this article, it is pertinent to review the research methodology used for greenium analysis in previous studies. Previous studies have implemented several explanatory variables into the analysis in performing the analysis in calculating greenium.

Table shows the methods and variables in the previous literature. The analysis of GB premiums first gained prominence with Zerbib (Citation2016). Zerbib (Citation2016) employed a matching method to compute the greenium, revealing a greenium of 0.02%. This analysis revealed that many investors would opt for GBs when offered on the same terms. Similarly, Baker et al. (Citation2018) delved into the analysis of GBs within the U.S. market, utilizing data from both primary and secondary markets. Their findings indicated the presence of a greenium ranging from 0.05% to 0.07%. Recent studies have consistently shown evidence of greenium in the samples they have examined. Hu et al. (Citation2022) analyzed a sample of 964 observations, demonstrating the existence of greenium.

Table 2. Methods and variables in the previous literature

Larcker and Watts (Citation2019) analyzed GBs issued by local governments in the U.S. and found no greenium, indicating that there was no yield advantage for GBs over conventional bonds. Similarly, Tang and Zhang (Citation2020) conducted an analysis using data from 1500 GBs in the global GB market and found no greenium, suggesting that, on average, GBs did not offer higher yields compared to conventional bonds.

Conversely, Karpf and Mandel (Citation2017) conducted a study on U.S. bonds and found that the yield was lower for conventional bonds, indicating a preference for conventional bonds over GBs in their study. Bachelet et al. (Citation2019) also found that yields on GBs were higher than those on conventional bonds, suggesting that there was no greenium in their analysis. Kapraun et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study on greenium in the global market using matching methods. Their findings indicated the presence of Greenium in the primary market but not in the secondary market. In a study by Agliardi and Agliardi (Citation2021) on the greenium of GBs on corporate bonds, they found that yields on GBs were higher than those on conventional bonds. The study also highlighted that greenium can be either positive or negative, and it is influenced by the credit rating of the company issuing the bonds.

Wang et al. (Citation2020) conducted an analysis of greenium in China. Following Zerbib (Citation2016), Wang et al. (Citation2020) used a matching method to calculate greenium. Their study found that greenium exists in the Chinese GB market, and notably, the value of greenium in the Chinese market was higher than that observed in the global market. Hu et al. (Citation2022) and Sun et al. (Citation2022) conducted an analysis of greenium in the Chinese GB market, specifically in both the primary and secondary markets. They also found that greenium was present in each of these markets, and its value was larger than the greenium in the global market. Most of the previous studies on greenium have used matching methods with actual trade data. In other words, they used data from GBs that were matched based on market supply and demand and subsequently traded. While this approach provides valuable insights into the market, it presents challenges in fully understanding investors’ broader attitudes toward GB investments.

3.2. Theoretical framework

Encouraging Chinese institutional investors to increase their investments in GBs should further boost the growth of China’s GB market and promote environmental protection. To delve deeper into the factors influencing Chinese investors’ decisions to invest in GBs, a subject largely unexplored in previous studies, it is crucial to thoroughly examine the environment surrounding institutional investors. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to investigate whether various attributes of Chinese institutional investors, such as age, gender, environmental awareness, and place of residence, influence their decision to invest in GBs, a topic largely unexplored in prior research.

To achieve this goal, it is necessary to analyze investor preferences within the GB market. A valuable indicator for this analysis is greenium, which represents the yield difference between conventional bonds and GBs. The concept of greenium suggests that under identical conditions, investors tend to prefer GBs over conventional bonds, leading to higher GB prices and lower yields compared to conventional bonds. Thus, changes in greenium can effectively mirror the trends in investors’ GB investments.

In this study, we conduct an analysis of greenium from the perspective of Chinese investors. To maintain consistency with prior studies that employed the matching method, it is essential to select the same explanatory variables, despite methodological differences. These variables pertain to attributes other than those of institutional investors, the degree of environmental considerations, and place of residence, all of which are known to influence greenium.

Hence, this article underscores the importance of selecting the same explanatory variables for greenium analysis as those used in previous research, while including variables that were not considered in previous studies, such as institutional investor attributes, the degree of environmental concern, and residential location. This approach ensures alignment with previous research.

4. Literature review and hypotheses development

To encourage investors to provide more funds for GBs, it is important to understand the factors influencing their investment behavior. Studies have identified several factors that affect investors’ decisions in the GB market. For example, Zenno and Aruga (Citation2022) clarify a greenium in the China GB market, while Zenno and Aruga (Citation2023) find that investors prioritize the issuer’s credit rating, issued currency, maturity, and liquidity when investing in GBs. Several previous studies have analyzed the influence of investors’ attributes, sentiment, and behavior on their financial market investments (Abdelhedi-Zouch et al., Citation2016; Jokar et al., Citation2018; Sarwar et al., Citation2016). However, little research has been conducted on how institutional investors’ social characteristics, such as gender, age, and level of interest in the environment, influence their investment decisions regarding GBs. Lotto (Citation2023) analyzed the influence of investor attributes on investment, however, the analysis does not specifically focus on China’s GB market, and the subjects studied are not institutional investors.

To bridge this research gap, this study initially analyzes the characteristics and attributes of institutional investors and investigates the factors that influence investment decisions. This is motivated by previous studies that have suggested that investor attributes, including gender, age, investment experience, and total transaction amount, play a role in determining the decision to invest in financial products.

When considering gender, it’s essential to recognize that males and females may exhibit different tendencies in their investment behavior (Goldsmith & Goldsmith, Citation2006). For instance, while females may be more inclined to prioritize social and environmental factors, they may also exhibit more hesitancy when it comes to investing in bonds, including green bonds. Therefore, gender assumptions will be considered as they could potentially influence gender-based investment behavior in green bonds. Reviewing previous studies, it is evident that over time, some have analyzed the differing perceptions of risk between men and women. For example, Levin (Citation1998) found that female students were more risk-averse compared to male students. Powell and Ansic (Citation1997) also identified that women tend to be more conservative in their financial decisions than men. These findings suggest that investment decisions can vary based on gender.

Turning to recent research, Al-Tamimi and Kalli Bin (Citation2009) indicated that females have lower financial literacy than males, and financial literacy negatively affects financial decisions. Charness and Gneezy (Citation2012) and Teker et al. (Citation2023) found a robust result, indicating that females are more risk-averse than males. While we could not find any previous studies that specifically analyze the influence of gender on GB investment in China, it would be worthwhile to explore whether GB investment in China demonstrates a greater inclination for males to invest in GBs than females, considering the findings of Al-Tamimi and Kalli Bin (Citation2009) and Charness and Gneezy (Citation2012).

Considering the insights gained from previous research, which underscores disparities based on gender in both general and environmental investments, there exists an opening for issuers, governments, and financial authorities to actively foster the growth of the GB market by acknowledging and mitigating these gender-specific distinctions. For instance, should it become apparent that males exert a less favorable influence on GB investments, GB issuers could contemplate the integration of a female perspective into their GB issuance and promotional strategies. Therefore, the exploration of gender-based disparities in GB investment decisions emerges as a worthwhile endeavor, recognizing gender as one of the contributing factors.

In terms of investor attributes, differences in investment behavior can likely be observed based on age as well as gender. Korniotis and Kumar (Citation2011) indicated that investors’ age can affect their investment decisions, with older investors tending to make portfolio choices reflecting greater knowledge about investing. In general, investors tend to experience an increase in income and total assets as they age, while younger investors often focus on aggressively growing their future income. Risk tolerance is closely tied to income and age, with higher-income and older investors typically displaying lower risk tolerance and a preference for risk-averse investments. Consequently, assumptions based on income and age may significantly impact investment behavior in green bonds.

Mitchell and Lusardi (Citation2022) showed that as people age, their financial literacy deteriorates, making them more reluctant to invest. On the other hand, Eberhardt et al. (Citation2019) found that older adults outperform younger adults on financial decisions may be limited to relatively common tasks, for which older adults have an opportunity to develop experience-based knowledge and reduced negative emotional responsiveness over time. Hence, we believe it’s of great significance to examine whether the age of institutional investors influences GB investment. For instance, if older institutional investors display greater engagement in GB investment, there may be opportunities to implement measures that specifically target and promote GB investment among younger age groups.

Investment experience is a factor that changes financial literacy regarding investments and influences investors’ decision-making (Lusardi & Tufano, Citation2015). Experienced investors often possess a greater awareness of investment risks and a deeper understanding of environmental and sustainable investment issues. Furthermore, their extensive investment experience equips them with the knowledge and skills to evaluate investment opportunities related to environmental concerns more effectively.

As a result, investment experience can play a pivotal role in shaping their investment choices, including decisions related to green bonds. In a series of recent studies, Gambetti and Giusberti (Citation2019) demonstrated that the experience of investment and anxiety was associated with the decision to save money, highlighting the potential impact of emotional factors on investment behavior. Hence, it would be worthwhile to analyze whether the experience of investing in GBs among the attributes of institutional investors influences institutional investors’ investment in GBs.

The total investment of institutional investors is often controlled by position limits set by each financial institution. This area has been previously studied due to its role in mitigating the risk of stock price volatility (Lintner, Citation1975). These limits are in place to manage various risks that can arise from excessive investments by individual investors. Position limits may include restrictions on holding large positions in certain securities. As a result, an institutional investor’s capacity to invest in a green bond at any given time might be influenced by these position limits, which can affect the amount of investment funds they can allocate to green bonds.

Irwin and Sanders (Citation2011) highlight that in commodity markets, investors’ position limits influence commodity prices by setting these limits. Given these findings, we find it important to investigate the total trading value of investors as an attribute that affects GB prices in the GB market. In alignment with the methodology employed in previous research that has explored factors influencing investment decisions, our objective is to investigate the influence of institutional investors’ attributes, encompassing gender, age, GB investment experience, and total transaction value, on their GB investments. Formally, the initial hypothesis for this study can be articulated as follows.

Hypothesis 1:

Social demographic background including gender, age, green bond investment experience, and the total investment amount, affects investment decisions in the Chinese GB market.

In the environmental context, it has been observed that individuals with a heightened environmental awareness tend to exhibit changes in their behavior driven by their concern for the environment (Chen et al., Citation2019; Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). Certain investors exhibit sensitivity to social and environmental factors, leading them to consider not only profitability but also the environmental and social impact of their investments. In such situations, it can be estimated that investors with a strong environmental awareness are likely to be attracted to the environmental attributes of green bonds and are more inclined to actively seek investment opportunities that prioritize environmental considerations.

Aruga (Citation2022) indicated that Japanese investors with high environmental awareness react positively to GB investments, however, no previous studies have investigated how environmental awareness influences GB investment in China. Therefore, in a similar vein, environmental awareness might influence the Chinese GB market, and we believe it is valuable to examine whether institutional investors’ environmental awareness impacts their GB investments. Understanding these impacts can support GB issuers in improving proposals and developing marketing strategies targeting Chinese institutional investors with high levels of environmental awareness. Thus, this study aims to examine the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2:

Institutional investors’ environmental awareness of China’s GB market affects their investment decisions.

We also acknowledge that previous studies have indicated that the cities and regions where individuals reside can influence their environmental behavior in China (Chen et al., Citation2011). Differences in industrial structures, economic characteristics, and responses to environmental measures can be observed in different regions. These differences may cause residents of a certain region to be more sensitive to the environment and consequently increase their interest in investments that promote environmental improvements, such as green bonds.

Green growth in China varies, depending on the level of urban development at various locations (Zhou et al., Citation2019). Therefore, examining whether the disparities in institutional investors’ residential locations affect their investments in GBs would potentially contribute to the GB market. These results can be utilized to develop market strategies for targeting specific residential sites, which can help disseminate GBs in China. Similarly, governments and financial authorities can formulate regulations, devise sales, and promote strategies customized to investors’ residential locations. Considering the analysis of the impact of institutional investors’ residential location on GB investment, we propose the following assumption:

Hypothesis 3:

Institutional investors’ residences affect investment decisions in the Chinese GB market.

5. Research design

5.1. Study designs

This study analyzed the institutional investors in three major financial cities in mainland China: Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. An online research service provider called “Wenjuan,” adopted by Mei and Brown (Citation2018), was used for surveying institutional investors. Wenjuan has approximately 10.4 million users as of May 2023. Respondents were randomly selected to participate in the survey. Before conducting the survey, we stated that disasters that occur frequently in many parts of the world are caused, in part, by global warming due to the use of fossil fuels and other energy sources. Then, the respondents were asked whether they recognized GB before completing the questionnaire to obtain data for this study.

The questionnaire was divided into five parts. In the first part, questions about the level of interest in the environment were asked, and responses were collected using a 5-choice Likert scale. In the second section, basic questions about bond investment and a description of GBs were provided, followed by questions that confirm the understanding of GBs. In the third part, questions related to investment in GBs were asked to confirm whether respondents had invested in GBs. In the fourth part, all respondents were asked about their criteria for choosing GB investments, followed by a two-stage CVM question about the yield difference between GBs and conventional bonds that would make them choose to invest in GBs, assuming they would invest in or consider investing in GBs. Finally, questions regarding the respondents’ attributes were asked. Before conducting the survey, a pretest was conducted by Wenjuan to ensure that the questionnaire had no issues.

The Shanghai sample was obtained from an institutional investors’ survey conducted between October 23 and 1 November 2021, specifically to avoid credit concerns surrounding the Evergrande Group, which spread in the Chinese market and globally (Deev et al., Citation2022; Sun & Cao, Citation2021). The survey of institutional investors in Shenzhen and Beijing was conducted between August 19 and 1 September 2022, because, in this period, the financial markets were calm in Beijing and Shenzhen, as COVID-19 had less impact on these markets, and it was before the Chinese New Year.

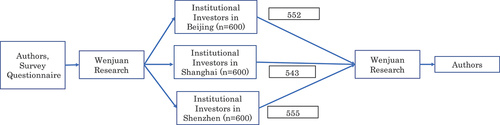

The survey was carried out in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, with 600 randomly selected institutional investors in each city. In this analysis, we excluded responses marked as “no” and “no” from the ordered logit model, as it is not possible to estimate the willingness to pay for these responses. As a result, the survey collected responses from 552 institutional investors in Beijing, 543 institutional investors in Shanghai, and 555 institutional investors in Shenzhen for the analysis. Figure shows the survey workflow.

5.2. Variable selection

5.2.1. Dependent variable

In this study, we have designated WTP as the variable representing greenium, the difference between the yields on conventional bonds and GB, that institutional investors are willing to pay. This variable is represented by the symbol “WTP_ordi.”

5.2.2. Core explanatory variables

In examining the impact of investor attributes on investment, we conducted a thorough review of previous studies, identifying four key attributes. Firstly, we selected “gender” as one of these attributes, drawing on insights from Goldsmith and Goldsmith (Citation2006) and Al-Tamimi and Kalli Bin (Citation2009), who highlighted differences in financial literacy and investment tendencies between women and men. Secondly, recognizing the age-dependent nature of investment behavior, as indicated by Korniotis and Kumar (Citation2011) and Mitchell and Lusardi (Citation2022), we included “age” as a crucial variable. Additionally, considering the influence of investment experience on financial literacy and resulting variations in investment behavior, “experience” emerged as another significant attribute, in line with findings from Gambetti and Giusberti (Citation2019) and other researchers. Finally, acknowledging insights from Lintner (Citation1975) and Irwin and Sanders (Citation2011), among others, who underscored that investors’ position limits lead to changes in investment behavior, we incorporated “invest”—representing the total investment—as a pivotal attribute in our study.

5.2.2.1. Respondent’s gender

In this paper, the respondent’s gender is employed as an explanatory variable to assess whether the gender of institutional investors influences their decision to invest in GBs. A response of “1” indicates males, and “0” represents females. In this study, it is denoted by the symbol “gender,” with a positive coefficient suggesting a relationship between male investors and GB investment.

5.2.2.2. Respondent’s age

In this study, we examine GB investment, using age as an explanatory variable to reflect the characteristics of the respondents. The respondent’s age is coded as follows: “1” for ages 20–29, “2” for ages 30–39, “3” for ages 40–49, and “4” for ages 50–59. This variable is represented by the symbol “age,” with an anticipated positive coefficient.

5.2.2.3. Respondent’s GB investment experience

In this analysis, we use whether institutional investors have previously invested in GB as an explanatory variable. If they have invested in GBs in the past, it is set to “1”; if they have not invested in GBs in the past, it is set to ”0.” This variable is symbolized as “gbexp,” and a positive coefficient is expected.

5.2.2.4. Respondent’s total investing amount

In this research, the total investment amount of institutional investors is set as an explanatory variable. If a respondent’s total investment amount is from RMB 1 to RMB 1 million, it is represented as “1”. If the respondent’s total investment amount is from RMB 1 million to RMB 3.5 million, it is represented as “2”. If the respondent’s total investment amount is from RMB 3.5 million to RMB 6.5 million, it is represented as “3”. If the respondent’s total investment amount is over RMB 6.5 million, it is represented as “4”. The symbol used is “invest,” and a positive coefficient is expected.

5.2.2.5. Respondent’s environmental concerns

This paper employs the level of environmental concern among institutional investors as an explanatory variable. If a respondent answers “very concerned,” it is represented as ”5.” If a respondent answers ‘concerned a little,’ it is represented as ‘4.’ If the response is ‘cannot say either,’ it is represented as ‘3.’ If the response is ‘not concerned very much,’ it is represented as ‘2.’ If the response is ‘not concerned at all,’ it is represented as ”1.” The symbol used is “env,” and a positive coefficient is anticipated.

5.2.2.6. Respondent’s place of residence

In this paper, the explanatory variable is set to determine whether the respondent resides in Shanghai or Shenzhen. If the respondent resides in Shanghai, the explanatory variable with the symbol “shang” is set to “1”; otherwise, it is set to ”0. If the respondent resides in Shenzhen, then the explanatory variable with the symbol ‘shen’ is set to ‘1’; otherwise, it is set to ”0.”

5.2.3. Control variables

To achieve the research objectives, we conduct an analysis using institutional investor attributes, environmental awareness, and residential location as explanatory variables. However, previous studies selected issuer credit ratings, redemption periods, and other factors influencing greenium as explanatory variables. To identify the most suitable variables for the GB investment decision criteria, it is essential to verify the variables that have been utilized in previous studies investigating greenium. Hence, a prudent approach involves the selection of variables for GB investment criteria by scrutinizing those variables that have been employed in previous research that examined greenium.

Zerbib (Citation2019) selected the explanatory variables based on yield, maturity, spread to conventional bond yield, redemption period, credit rating, and whether the issuer was a government-related entity or a private corporation. Dou et al. (Citation2019) used variables related to policy differences, the percentage of project use, whether it is a medium-term bond, and whether issued by private companies or state-owned enterprises. Dou et al. (Citation2019) also selected variables such as the company’s industry, listing status, assets and size, and the percentage of long-term debt in total debt.

Fatica et al. (Citation2021) chose the yield and types of bonds, use of proceeds, maturity, credit ratings, and liquidity as explanatory variables. Larcker and Watts (Citation2019) used the issuer’s credit rating, presence of options and labels, yield, green rating, issuer’s industry, issue amount, bond rating, and maturity as explanatory variables. Bachelet et al. (Citation2019) studied the role of issuer characteristics and third-party certification in greenium using the credit rating of the issuer, issue amount, type of bond, issuer, coupon type (fixed or floating), bond currency, presence of a label, bond rating, issuer’s industry, maturity, and liquidity as explanatory variables.

Li et al. (Citation2020) considered label, CSR rating, issuer rating, bond rating, maturity, return on equity, EBITDA/interest, and total asset turnover as dependent variables for their study. Sangiorgi and Schopohl (Citation2021) surveyed European institutional investors regarding their GB purchase, confirming the use of credit ratings, currency, issuer industry, minimum issue amount, environmental reliability at issuance or label, environmental reliability after issuance or reporting, and price as explanatory variables.

Building on the findings of these earlier studies, following variables are considered as control variables in this study: the credit rating of the issuer, the use of funds, the issue amount or liquidity, the redemption term, the issuer’s business sector, the currency of the bond, and the presence of a label, and pre-explanation or post-report.

5.2.3.1. The issuer’s credit rating

In this study, credit rating is included as a control variable to account for the influence of the issuer’s credit rating. It is coded as “1” if a Chinese institutional investor considers the issuer’s credit rating as a criterion for GB investment and “0” otherwise. The variable is denoted by ”credit.”

5.2.3.2. The use of the fund

The use of the GB fund is set as a control variable in this paper to control for its effect. It is coded as “1” if an institutional investor considers the use of the GB fund as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is ”usage.”

5.2.3.3. The issue amount or liquidity

In this research, the issue amount or liquidity of GB is included as a control variable to control the impact of the issue amount. It is coded as “1” if an institutional investor considers the issue amount of GB as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is ”liquidity.”

5.2.3.4. The redemption term

This paper considers the redemption term of GB as a control variable to control its impact. It is coded as “1” if a Chinese investor considers the redemption term of GB as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is ”term.”

5.2.3.5. The issuer’s business sector

This study incorporates the issuer’s business sector as a control variable to control for its effect. It is coded as “1” if a respondent considers the issuer’s business sector as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is ”issuer.”

5.2.3.6. The type of currency

This paper includes the type of currency of GB as a control variable to control for its effect. It is coded as “1” if an investor considers the type of currency as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is ”currency.”

5.2.3.7. The certification label

This study considers the certification label as a control variable to control for its impact. It is coded as “1” if a respondent considers GB with the certification label as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is ”label.”

5.2.3.8. Pre-explanation or post-report

This paper includes pre-explanation or post-report as a control variable to control for its effect. It is coded as “1” if an investor considers GB issuance with pre-explanation or post-report as a criterion for GB investment, and “0” otherwise. The symbol used is “maintenance” as shown in Table .

Table 3. The selection of variables

5.3. Demographic statistics and environmental concerns

Table presents the demographic statistics of the institutional investors surveyed in the three cities. In Beijing, 35.51% of the respondents expressed a higher concern for the environment than in other cities. Furthermore, 45.83% of the institutional investors in Beijing reported having invested in GBs, which was higher than the corresponding percentages in the other two cities.

Table 4. Summary of demographic statistics and environmental concerns of survey responses

In Shanghai, the percentage of male respondents and those in the 30–39 age range was higher than the average. However, the percentage of respondents with GB investment experience in Shanghai was lower than that in Beijing and Shenzhen (37.02 %). Only 31.68% of the institutional investors in Shanghai were “very concerned” about the environment, which was the smallest percentage among the three cities.

In Shenzhen, the percentage of male respondents was lower than that in the other cities, while the age groups of 20–29 and 30–39 were higher than those in Beijing and Shanghai. The percentage of respondents expressing being “very concerned” about the environment in Shenzhen fell between Beijing and Shanghai.

Table summarizes the distribution of survey responses regarding institutional investors’ GB investment decision criteria in the three cities. Table indicates that most institutional investors consider the selected criteria in this study important. However, the responses of the respondents in the three cities are distinct. Regarding the greenium explanatory variables in Beijing, 77.72% of the respondents considered issuance volume or liquidity as a criterion higher than the average. Additionally, 82.07% of the respondents considered the issuer’s industry a criterion, surpassing the average. However, Shanghai showed higher “yes” responses compared to the other two for usage, term, currency, and maintenance. In the case of Shenzhen, investors demonstrated a higher number of “yes” responses than the other two cities for credit and label. The survey results indicate that institutional investors in the three cities prioritize different criteria while making GB investment decisions.

Table 5. Summary of survey responses for GB investment decision criteria

5.4. Methods of analysis

5.4.1. Contingent valuation design

To estimate the institutional investors’ WTP, the benchmark bond level was presented to the respondents at the beginning of the survey. This level is based on the yields of 10-year government bonds and 10-year conventional bonds issued by the China Development Bank, the largest GB issuer in China. Respondents were then asked whether they would invest based on the yield spread between the benchmark bond and GBs. If they responded “yes” to invest, the yield was lowered, and they were asked again whether they would invest. If they chose “no” to invest, the yield was raised, and they were asked again whether they would invest. This constituted the double-bound dichotomous (DBDC) question design with two rounds of questioning to mitigate potential biases (Lopez-Feldman, Citation2012; Watson & Ryan, Citation2007).

5.4.2. WTP for the greenium and designing of bids

In this study, the WTP was defined as greenium, which indicates the difference in yield between GBs and conventional bonds. We surveyed 1800 institutional investors in three cities, with 600 respondents in each city. The sample size of 600 surpasses the quantity suggested by Banga et al. (Citation2011), who proposed that the DBDC method necessitates a sample of 400. A total of 600 respondents from each city, were randomly and equally divided into five groups. Next, 1800 respondents were surveyed using the DBDC method with two rounds of questions.

To provide a comprehensive breakdown for institutional investors in the three cities, five groups were similarly presented with initial yield differences of −0.50%, −0.25%, 0.00%, +0.25%, and + 0.50% compared to the conventional bond yield, and asked whether they would invest in GBs. For the second question, respondents who answered “yes” in the first question were asked whether they would invest in GBs with a one-step lower yield, and respondents who answered “no” were asked whether they would invest in GBs with a one-step higher yield. For the second question, institutional investors in Beijing and Shenzhen were presented with yield differences of −0.75%, −0.50%, −0.25%, ±0.00%, +0.25%, +0.50%, and + 0.75% relative to the benchmark interest rates based on 10-year Chinese government bonds and 10-year Chinese Development Bank conventional bonds. For institutional investors in Shanghai, the presented yield differences were −1.00%, −0.50%, −0.25%, ±0.00%, +0.25%, +0.50%, and + 1.00% relative to the benchmark interest rates. The distributions of the bid responses for the three cities are listed in Table .

Table 6. Distributions of the bid responses in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen

In this study, the analysis excluded data from those who answered “no” to both the first and second rounds of the CVM questionnaire since it was not possible to identify the actual WTP for these respondents. Among the data of 1800 respondents, we used data from 1650 institutional investors: 552 from Beijing, 543 from Shanghai, and 555 from Shenzhen.

5.5. Econometric methods

This study examines the utility that institutional investors derive from investing in GBs by considering greenium as a measure of their WTP. Therefore, to represent institutional investors’ preferences in deciding to invest in GBs, we employ a random utility function, and the individual WTP can be expressed as follows:

where is the vector of explanatory variables,

is the vector of parameters, and

represents the error term.

To analyze whether institutional investors’ demographics, environmental awareness, and place of residence affect GB investments, we used the following regression model:

where represents the values calculated from the data obtained through DBDC, β0is the constant, and β1 to β15 are the coefficients of the core explanatory variables.

is an error term.

We conducted the analysis using an ordered probit model. Denoting as our observed ordered dependent variables

as the highest rank order such that

is determined by the unobserved latent variable

:

where … ,

are threshold parameters such that

and

. Then, the probit model can be expressed as:

where and β are k x 1 vectors of observed explanatory variables and unknown parameters, and

is the random error term. The probability of observing a particular ordered outcome for a given

is:

where F represents the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution.

The βs are estimated by the log-likelihood function indicated as:

where Zij is an indicator variable that equals 1 when and equals 0 otherwise.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Empirical results

Intending to bolster the issuance of GBs, which play a crucial role in mobilizing funds for environmental conservation efforts in China, this study examined the impact of attributes among Chinese institutional investors. This encompassed their environmental awareness and geographic location, an aspect not thoroughly investigated in prior research. We adopted a direct questionnaire survey approach among institutional investors across three cities and employed an ordered logit model for data analysis. The outcomes of this investigation are detailed below.

6.1.1. Respondents’ demographic and social statistics affecting greenium

Table presents the estimation results using the ordered probit regression. We found that gender, age, and invest of institutional investors in the three cities in China did not have a significant impact on greenium in the GB market. However, the explanatory variable (gbexp), indicating prior experience with GB investments as demonstrated by Gambetti and Giusberti (Citation2019), had a significant impact on the greenium.

Table 7. Ordered probit regression results

6.1.2. Respondents’ environmental awareness affecting greenium

Table shows that institutional investors’ environmental awareness of China’s GB market (env), demonstrated by Aruga (Citation2022), significantly influences investment decisions. Based on these findings, it is evident that fostering further growth in the GB market requires efforts to enhance environmental awareness among institutional investors, who play crucial roles as fund providers.

6.1.3. Impact of residing in different cities in China on the greenium

Following Baker et al. (Citation2019), we analyzed the impact of residents in three different financial cities on the greenium. The results, as shown in Table , indicate that residing in Shanghai has a statistically significant impact on the greenium compared to that in Beijing, with a p-value of less than 0.1. However, residents in Shenzhen did not show remarkable results compared to those in Beijing.

6.2. The test of hypothesis 1

We have set the social demographic background, including gender, age, green bond investment experience, and the total investment amount, which may affect investment decisions in the Chinese GB market, as hypothesis 1. Our results show that gender, age, and invest of institutional investors in the three cities in China did not have a significant impact on greenium in the GB market. However, investing in GBs (gbexp) impacted the greenium significantly. Therefore, hypothesis 1, regarding the influence of sociodemographic background on investment decisions in the Chinese GB market, is partially supported.

6.3. The test of hypothesis 2

We posit that institutional investors’ environmental awareness of China’s GB market affects their investment decisions as hypothesis 2. In this study, we found the results supporting hypothesis 2, suggesting that institutional investors’ environmental awareness of China’s GB market (env) significantly influences investment decisions.

6.4. The test of hypothesis 3

We configure that Institutional investors’ residences affect investment decisions in the Chinese GB market as hypothesis 3. Our results indicate that residing in Shanghai has a statistically significant impact on the greenium compared to that in Beijing, with a p-value of less than 0.1. However, residents in Shenzhen did not show significant results compared to those in Beijing. Therefore, we accept hypothesis 3, which establishes that institutional investors’ residence influences investment decisions in the Chinese GB market.

6.5. The discussion

The growth of China’s GB market has largely been driven by government and financial authorities, but to ensure its continued growth, further action is required. The results of this study, which included direct input from institutional investors and data analysis, offer invaluable insights. Specifically, the findings that Chinese institutional investors tend to continue their GB investments once initiated, that environmentally conscious investors show a preference for GB investments, and that institutional investors in Shanghai favor GB investments, provide essential guidance for GB market participants to expand and develop the market. These insights can significantly contribute to the continuous growth and development of the GB market.

Furthermore, the study reveals that Chinese institutional investors prioritize GB issuer credit ratings in their investment decisions. Additionally, as highlighted by Barua and Chiesa (Citation2019), the liquidity of GBs emerges as a crucial criterion influencing investment decisions. These findings provide valuable insights to foster the continued expansion of the GB market in China. We believe that the positive impact of these results will extend to GB issuers, the government, and financial authorities, all of whom are stakeholders in the GB market.

6.5.1. Implication for issuers

The analysis reveals that institutional investors with a stronger environmental focus and greater experience in GB investments tend to prefer GBs over conventional bonds. This finding implies that issuers can target their sales efforts towards such investors, encouraging them to increase GB issuances. For instance, previous GB investors could be enticed to invest again through tailored sales strategies. Furthermore, attracting new institutional investors to the GB market, especially those who aren’t environmentally conscious, is recommended to expand the investor base.

Additionally, the study underscores that Chinese institutional investors consider issuer credit ratings when making GB investments. This suggests that GB issuers should improve their financial health to attain higher credit ratings (Hamdi et al., Citation2022), which can further attract investor interest.

6.5.2. Implication for government and financial authorities

Based on the results of this study, from the perspective of institutional investors, it is suggested that the government and financial authorities should consider measures to promote the growth of GBs. First, as this study’s results indicate a preference for GB investments among environmentally conscious institutional investors, the government and financial authorities are proposed to implement policies that enhance environmental awareness among a wide range of institutional investors. For example, a mass communication strategy could be considered to emphasize the importance of environmental factors in investment decision-making.

This analysis revealed that investors in Shanghai have a more cheerful outlook toward GB investments compared to institutional investors residing in Beijing and Shenzhen. As a result, the Chinese government and financial authorities should not only promote policies to encourage institutional investors in Shanghai to invest more in GBs but also make GB investments more attractive to investors in Beijing and Shenzhen. For instance, specific subsidies or incentives could be introduced for institutional investors in these two cities.

To enhance the creditworthiness of GB issuers, the government, and financial regulatory authorities should actively formulate policies and regulations that make GB issuers more creditworthy in the eyes of institutional investors who prioritize credit ratings.

Furthermore, considering that Chinese institutional investors prioritize the liquidity of GBs, it is suggested that the government and financial authorities should introduce measures to improve the liquidity of GBs. For example, various strategies can be explored by drawing inspiration from initiatives like the Bank of Japan (BOJ)‘s Climate Change Response Support Fund Supply Operations (Bank of Japan BOJ, Citation2021), which has been proven effective in promoting investments in green finance.

6.6. Robustness check

To assess the robustness of this analysis, we undertook an examination of the explanatory section on institutional investor attributes. This analysis employed a heteroskedastic ordered probit model, which effectively accounts for scatter heterogeneity within the data. The results, presented in Table , unveil a consistent pattern. Notably, there is no discernible variance in the significance of the outcomes across this alternative model. Consequently, it can be affirmed that the results obtained through the model employed in this paper hold their robustness

Table 8. The results of the robustness test

7. Summary and conclusion

GBs attracting participants from the financial sector is an effective measure to reduce the environmental impact caused by human activities. Further studies are needed to understand the factors investors consider important for GB proliferation in the finance industry. While some studies have investigated the factors related to GBs, such as the issuer’s credit rating and currency type for issuing GBs, little is known about how investors’ decisions differ based on the type of investor. Therefore, this study examined how investor attributes, such as their level of environmental concern and place of residence, influence their investment behavior.

In this study, we selected four attributes by reviewing previous studies that analyzed the impact of investor attributes on investment. For instance, Goldsmith and Goldsmith (Citation2006) and Al-Tamimi and Kalli Bin (Citation2009) included “gender” because they demonstrated differences in financial literacy and investment trends between women and men. Subsequently, Korniotis and Kumar (Citation2011) and Mitchell and Lusardi (Citation2022) introduced “age” as an attribute due to varying investment behavior based on investors’ age. Others, such as Gambetti and Giusberti (Citation2019), indicated that investment experience influences financial literacy and creates distinctions in investment behavior. Hence, “investment experience” was also chosen as one of the variables. Lintner (Citation1975) and Irwin and Sanders (Citation2011), among others, incorporated total investment amount, “invest” as an attribute in this study since they demonstrated that investors’ position limits cause changes in investment behavior.

Recognizing that Aruga (Citation2022) demonstrated that environmentally aware investors in Japan react positively to GB investments, this study explores whether the environmental awareness of institutional investors in China’s GB market mirrors the behavior observed among institutional investors toward GB investments. The results reveal that institutional investors in China’s GB market exhibit a high level of environmental awareness. Additionally, it shows that institutional investors’ environmental awareness in China’s GB market lowers the yield of their investment benchmark bonds, significantly influencing their investment decisions. This suggests that efforts to improve institutional investors’ environmental awareness are needed for further growth of the GB market. Through effective communication on the significance of the environment, the aspiration is that institutional investors will prioritize green investments, thereby contributing to environmental sustainability.

In addition, this study analyzed place of residence as a variable, inspired by Chen et al. (Citation2011), who showed that environmental behavior differs depending on different places of residence in China. The results indicate that for Chinese institutional investors, residence in Shanghai significantly impacts GB investment, leading to a decrease in the base yield of GB investment.

Finally, building on previous studies, this research also found that the credit rating of the issuer, the use of funds, the liquidity or issue volume, and the maturity of the bond were all significantly affected by GB investment. The following factors are considered in this study: the credit rating of the issuer, the use of funds, the liquidity or issue amount, the maturity of the bond, the issuer’s industry, the currency of the bond, and the presence of a label, and the pre-explanation or post-report. The results show that the credit rating of the issuer and the liquidity or issuance volume of the bond positively affect GB investment. Higher credit ratings of GB issuers are expected to further increase GB issuance and the possibility of raising funds at lower yields. Additionally, it was shown that GB issuers are required to issue GBs not in small amounts but in sufficient amounts.

This paper analyzes the impact of the attributes of Chinese institutional investors on GB investment, a dimension not extensively explored in previous studies. The results presented in this paper suggest for the first time the measures that GB market stakeholders, including issuers, the government, and the financial authorities, should take to promote further growth of the Chinese GB market from the institutional investors’ perspective. We believe this new perspective on GB market research will promote further growth. This is the first time that the paper has suggested measures to be taken to promote further growth of the Chinese GB market from the perspective of institutional investors.

Concerning the paper’s impact on GB market participants, we posit that encouraging issuers to concentrate their marketing efforts on China’s environment could be beneficial. This suggestion stems from our observation that institutional investors with a keen interest in China’s environment tended to invest in GB. Furthermore, we suggest that the government and financial authorities should implement measures to raise environmental awareness among institutional investors. Additionally, given the demonstrated propensity of institutional investors residing in Shanghai to invest in GB, issuers should focus on this demographic in their marketing efforts. It is recommended that the government and financial authorities consider efforts to create an environment in financial cities outside of Shanghai that has achieved the same level of improved financial literacy as Shanghai.

This study used a questionnaire survey targeting direct Chinese institutional investors. The data collected underwent ordered logit analysis to examine the influence of institutional investor attributes, environmental concerns, and residential location on GB investment. Noteworthy is the innovative approach of this paper, which, in contrast to previous studies that analyzed data from executed transactions, obtained and analyzed data through a direct survey of institutional investors. This novel method provided a fresh perspective in the research, breaking away from the conventional approaches. The outcomes of this paper are deemed to contribute significantly to the study of the GB market. This is because the discovery, introducing a new analytical perspective and offering valuable insights that enhance existing research findings, is anticipated to serve as valuable material. For issuers, this implies concentrating sales efforts on environmentally conscious investors and those with prior experience in GB investment as part of GB dissemination strategies. Likewise, for governments and financial authorities, it suggest implementing effective measures, such as media initiatives, to boost investor interest in the environment.

In summary, this paper pioneers new avenues in GB market research by uncovering previously overlooked dimensions, including the GB investment experience of Chinese institutional investors, substantial issuance for liquidity, the cultivation of institutional interest in the environment, and the impact of residing in Shanghai on Chinese GB investment. The utilization of innovative research methods further distinguishes this study within the GB market research landscape. Furthermore, disseminating these findings among stakeholders in the Chinese GB market could serve as a foundation for devising strategies to expand the market. Given these insights, we acknowledge the paper’s exceptionally significant contribution to GB research in China.

The statement made by Deputy Governor Xuan Changsheng of the PBOC during the 8th China Bond Forum highlights the commitment of the PBOC to improve the GB system and norms, promote innovation in GB product issuance, and address the challenges faced by the GB market in China. The findings presented in this study can provide valuable insights for the Chinese government and financial officials as they work towards further growth and development of the GB market.

However, this study has limitations. First, one of the limitations of this study is its restricted research scope. While this study focused on analyzing the three largest financial cities in mainland China, it is important to consider conducting further analyses encompassing other cities and regions in China. These three cities are developed coastal cities in China. Different results may be observed for cities located in central or inland China, similarly, distinctions may arise for the northern and southern regions of China, as Shang et al. (Citation2023) indicated in the context of green finance.

Another limitation is the study’s restricted time frame. It is important to acknowledge that this study used data from China during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have introduced certain limitations and differences compared with normal times. Future research could address this by conducting similar surveys and analyses when the impact of COVID-19 subsides, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the GB market under different circumstances.

Despite its limitations, we acknowledge that the results of this analysis are significant as they point toward new avenues for future research. The analysis conducted in this study is anticipated to contribute not only to the expansion of the GB market in China but also to yield findings applicable to various other domains. For example, the results of this study can be utilized to address environmental issues in emerging countries. Although previous studies have analyzed GBs in emerging countries (Nguyen et al., Citation2023; Prakash & Sethi, Citation2021; Verma & Bansal, Citation2023; Yamahaki et al., Citation2022), none have performed the analysis of the influence of institutional investor attributes and level of environmental concern on GB investment using the methodology of this paper. China’s experience in establishing and growing its GB market can serve as a model for other countries in the initial stages of the GB market development. By disseminating the history and findings on China’s GB market, other countries can learn from their efforts to realize environmental conservation through GB investments. The results are anticipated to contribute not only to the growth of the GB market in China but also to the expansion of the GB market globally, thereby playing a part in mitigating global warming.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdelhedi-Zouch, M., Ghorbel, A., & McMillan, D. (2016). Islamic and conventional bank market value: Manager behavior and investor sentiment. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1164010. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1164010

- Agliardi, E., & Agliardi, R. (2021). Corporate green bonds: Understanding the greenium in a two-factor structural model. Environmental and Resource Economics, 80(2), 257–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00585-7

- Al-Tamimi, H. A. H., & Kalli Bin, A. A. (2009). Financial literacy and investment decisions of UAE investors. The Journal of Risk Finance, 10(5), 500–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265940911001402

- Amstad, M., & He, Z. (2019). Chinese bond market and interbank market (No. w25549). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Aruga, K. (2022). Are retail investors willing to buy green bonds? A case for Japan. Proceedings of the Mapping the Energy Future-Voyage in Uncharted Territory—43rd IAEE International Conference, Tokyo, Japan (Vol. 31).

- Bachelet, M. J., Becchetti, L., & Manfredonia, S. (2019). The green bonds premium puzzle: The role of issuer characteristics and third-party verification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041098

- Baker, M., Bergstresser, D., Serafeim, G., & Wurgler, J. (2018). Financing the response to climate change: The pricing and ownership of US green bonds. (No. w25194). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., Goyal, N., & Gaur, V. (2019). How financial literacy and demographic variables relate to behavioral biases. Managerial Finance, 45(1), 124–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-01-2018-0003

- Banga, J. (2019). The green bond market: A potential source of climate finance for developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 9(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2018.1498617

- Banga, M., Lokina, R. B., & Mkenda, A. F. (2011). Households’ willingness to pay for improved solid waste collection services in Kampala city, Uganda. Journal of Environment & Development, 20(4), 428–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496511426779

- Bank of Japan. (2021). Outline of transactions for Climate response financing operations. Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/measures/mkt_ope/ope_x/opetori22.htm

- Barua, S., & Chiesa, M. (2019). Sustainable financing practices through green bonds: What affects the funding size? Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(6), 1131–1147. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2307

- Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.007

- Chen, K., & Chen, G. (2015). The rise of international financial centers in mainland China. Cities, 47, 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.11.012

- Chen, X., Huang, B., & Lin, C. T. (2019). Environmental awareness and environmental Kuznets curve. Economic Modelling, 77, 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.02.003

- Chen, S., Lakkanawanit, P., Suttipun, M., & Xue, H. (2023). Environmental regulation and corporate performance: The effects of green financial management and top management’s environmental awareness. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2209973. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2209973

- Chen, X., Peterson, M. N., Hull, V., Lu, C., Lee, G. D., Hong, D., & Liu, J. (2011). Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour in urban China. Environmental Conservation, 38(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689291000086X

- Climate Bond Initiative. (2023). Interactive data platform as of end 2022. Climate Bond Initiative Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://www.climatebonds.net/market/data/

- Climate Bond Initiative (CBI). (2022 November). China green bond market report 2021. Climate Bond Initiative. https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/china-green-bond-market-report-2021.

- Deev, O., Lyócsa, Š., & Výrost, T. (2022). The looming crisis in the Chinese stock market? left-tail exposure analysis of Chinese stocks to Evergrande. Finance Research Letters, 49, 103154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103154

- Deschryver, P., & De Mariz, F. (2020). What future for the green bond market? How can policymakers, companies, and investors unlock the potential of the green bond market? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13030061

- Dou, X., Qi, S., & Luo, R. H. (2019). The choice of green bond financing instruments. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1652227. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1652227

- Du, Y., & Wang, W. (2023). The role of green financing, agriculture development, geopolitical risk, and natural resource on environmental pollution in China. Resources Policy, 82, 103440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103440

- Eberhardt, W., Bruine de Bruin, W., & Strough, J. (2019). Age differences in financial decision making: T he benefits of more experience and less negative emotions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 32(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2097

- Fatica, S., Panzica, R., & Rancan, M. (2021). The pricing of green bonds: Are financial institutions special? Journal of Financial Stability, 54, 100873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100873

- Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.01.010

- Gambetti, E., & Giusberti, F. (2019). Personality, decision-making styles and investments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 80, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2019.03.002

- Gianfrate, G., & Peri, M. (2019). The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.022

- Goldsmith, R. E., & Goldsmith, E. B. (2006). The effects of investment education on gender differences in financial knowledge. Journal of Personal Finance, 5(2), 55–69.

- Hamdi, K., Guenich, H., & Ben Saada, M. (2022). Does corporate financial performance promote ESG: Evidence from US firms. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2154053. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2154053

- Hassan Al‐Tamimi, H. A., & Anood Bin Kalli, A.(2009). Financial literacy and investment decisions of UAE investors. The Journal of Risk Finance, 10(5), 500–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265940911001402

- He, Z., & Wei, W. (2023). China’s financial system and economy: A review. Annual Review of Economics, 15(1), 451–483. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-072622-095926

- Hu, C. Y., Dekker, D., & Christopoulos, D. (2022). Rethinking greenium: A quadratic function of yield spread. Finance Research Letters, 54, 103710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103710

- Hu, X., Zhong, A., & Cao, Y. (2022). Greenium in the Chinese corporate bond market. Emerging Markets Review, 53, 100946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2022.100946