Abstract

This study aims to explore the impact of various board composition elements (board size, board meeting frequency, multiple directorships, and board independence) on capital structure decisions within emerging markets, specifically focusing on the Sultanate of Oman. The study employs a sample of 14 non-financial firms listed on the MSM30 index over seven years (2009–2015). To address endogeneity between the interrelated variables of dividends and debt ratio, an endogeneity test is performed. Given that the dividend per share is an endogenous variable, the Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) method is used for data analysis. The findings of this study indicate positive associations between debt ratio and board size, board independence and multiple directorships but negative association with board meetings frequency. Board independence serves to support the active monitoring hypothesis, and debt acts as a complementary mechanism to mitigate agency issues, larger board size results in introducing more debts in the firm’s capital structure to offset decision making complexities. Furthermore, multiple directorships increase the use of debt ratio as disciplinary mechanism to offset the busyness of board members who have several multiple directorships. However, the frequency of board meetings was found to have a negative association with debt ratio. Our findings are robust to alternative measures of leverage and endogeneity. This study concentrates on a limited set of factors related to board composition. The use of debt as a substitute mechanism suggests that the followed corporate governance practices are relatively weak and may benefit from further reforms.

Impact Statement

This study offers to the readers a new insight from an emerging market on the impact of board composition on financing decision. The results are of particular importance to such market, since this market has distinctive characteristics of weak external law to protect investors and it is well known by using debt as substitute mechanism of corporate governance practices.

1. Introduction

Board composition is considered a key mechanism in corporate governance. Through its characteristics, robust monitoring of top-management levels can be achieved (Bazhair, Citation2023; Boateng et al., Citation2022). Building on this premise, board composition fulfills its role through various mechanisms, including board size, board meeting frequency, the proportion of independent directors, and the presence of directors occupying multiple seats. The focus of this study is to investigate the relationship between these mechanisms and capital structure decisions in the emerging securities market of Oman, specifically the Muscat Securities Market index (MSM30). The study aims to answer the following four research questions: i) What is the impact of board size, board meeting frequency, multiple directorships, and board independence on the debt ratio for firms listed on the MSM30?

Most of the existing studies on the subject in Oman have focused on the relationship between conventional ‘firm-specific determinants’, such as risk, profitability, tangibility, firm size, and growth, and capital structure decisions (Al Ani & Al Amri, Citation2015; Fernández & Brown, Citation2013; Khaki & Akin, Citation2020; Mohammadi et al., Citation2020; Singh, Citation2016). While corporate governance has received considerable attention in the Omani context (Bawazir et al., Citation2021; Queiri et al., Citation2021; Yilmaz, Citation2018), research that directly explores how CG elements shape capital structure decisions in Oman remains scarce. Despite extensive investigations into this area in the developed markets, a significant research gap still exists with regard to the influence of corporate governance on capital structure decisions in the Omani context.

This study contributes to the literature on both corporate governance and capital structure in several ways. First, the paper investigates the impact of different dimensions of corporate governance (board size, board meeting frequency, multiple directorships, and director independence) on capital structure in an emerging market. it offers in-depth insight into the formation of capital structure through the lens of corporate governance (CG) elements, going beyond the conventional factors that have already been extensively studied in the Muscat Securities Market (MSM), which operates under a specific legal regime. Second, while very few studies focus on the Omani case, this research specifically addresses the Omani context, conducting the analysis for non-financial firms listed in the MSM30 index. The study’s findings will provide evidence from Oman on how board compositions can serve as effective corporate governance mechanisms to address the agency problem, utilizing debt as a disciplinary mechanism. Therefore, this research extends the theoretical evidence into the uncharted territory of Oman. Third, the findings of this study aim to have a practical contribution by assisting policymakers in crafting appropriate corporate governance codes of conduct by elucidating the role that CG elements play in shaping capital structure decisions and, consequently, enhancing a firm’s financial performance. Currently, Oman is focusing on improving its financial stability and is keen to implement rigorous corporate governance practices, as these are seen as critical mechanisms for achieving such stability. In this context, Shehata (Citation2013) has recommended further reforms for the corporate governance codes of conduct in GCC countries, including Oman. While most GCC codes are more comprehensive than those in other Middle East North Africa (MENA) countries, there remains room for improvement. With this backdrop, this study aims to investigate the relationship between CG elements and capital structure decisions.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows; First, a literature review provides insights into the MSM30, capital structure theories, and corporate governance in the Omani context. Following this, there is a review of previous studies and the development of hypotheses. Lastly, the paper presents the results along with a discussion and offers practical implications for corporate governance mechanisms and their relevance to capital structure decisions.

2. Background

Beyond the influence of conventional factors on a firm’s performance and other important corporate finance decisions such as investment and capital structure decisions, there has recently been increased scholarly attention directed toward investigating the role of corporate governance elements. These elements have been examined for their relevance to firm performance, cash holding, cost of debt, and capital structure decisions (Dwaikat, Citation2023; Hashim & Amrah, Citation2016; Júnior, Citation2022; Morellec et al., Citation2012; Queiri et al., Citation2021; Zaid et al., Citation2020). This focus is not new; the impact of corporate governance (CG) elements on capital structure decisions is well-documented in the literature (Feng et al., Citation2020; Hussainey & Aljifri, Citation2012; Júnior, Citation2022; Mertzanis et al., Citation2023). The basis for such impact can be traced to the principle of Agency Cost Theory. According to Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976), the separation between ownership and control encourages managers to act in their own best interests, leading them to shape capital structure decisions to maximize their own benefits. In this context, debt is often suggested as a mechanism to curb such opportunistic managerial behavior and to align it with shareholders’ objectives of wealth maximization.

This rationale can be clarified in four ways. First, debt can act as a corporate governance mechanism grounded in the free cash flow hypothesis, where the obligation to pay fixed interest rates limits managerial discretion in spending (De La Bruslerie, Citation2016; Jensen, Citation1986; Vijayakumaran & Vijayakumaran, Citation2019). Second, managers are more likely to align their behavior with shareholder interests when utilizing debt to avoid the potential risks of bankruptcy and the consequent loss of their reputations and jobs (Abor, Citation2008; Grossman & Hart, Citation1982). Third, the scrutiny by debt-holders and financial markets induces managers to act in the best interests of shareholders. Therefore, there is academic consensus in the field of Corporate Finance that the judicious use of debt can effectively mitigate agency problems and consequently increase firm value. Fourth, good corporate governance will maintain an optimal capital structure (Manu et al., Citation2019). In other words, effective corporate governance, including board compositions, could impact capital structure decisions, potentially resulting in lower costs of debt financing. This is because the cost of debt is inversely related to board independence and board size (Ronald et al., Citation2004).

However, empirical studies have reported mixed and inconsistent findings regarding how CG elements influence capital structure decisions. For example, to highlight a few inconsistencies, Júnior (Citation2022), Vijayakumaran and Vijayakumaran (Citation2019), and Hussainey and Aljifri (Citation2012) found that board composition has an insignificant influence on capital structure decisions for Latin American, Chinese, and UAE stock markets, respectively. These results contradict the findings of other studies, such as those by Florackis and Ozkan (Citation2009) and Berger and Heath (Citation2007), who concluded that board size is inversely related to debt. These inconclusive results underline the need for further investigation.

The inconsistency in empirical results is attributed to deeper factors. According to Mitton (Citation2004), these mixed findings hinge on variables at both the company and country levels. Aspects like common law versus civil law systems and variations in corporate and ownership structures can contribute to these mixed results (Porta et al., Citation1998; Queiri et al., Citation2021). Given this background, it is unrealistic to expect that emerging markets like Oman will perfectly align with findings from more developed markets. Therefore, the capital structure decisions for companies listed in Oman may be influenced by CG elements in a different manner, making empirical validation necessary.

3. Theoretical literature review

3.1. Capital structure theories

Under certain assumptions, the seminal work of Modigliani and Miller (Citation1958) concluded that the means of financing whether through debt or equity is irrelevant to a firm’s value. However, when these assumptions are relaxed to account for factors such as asymmetrical information, taxes, and bankruptcy costs, it becomes evident that capital structure is indeed a relevant factor in determining a firm’s value. Consequently, the relevance proposition emerged.

Various theories have extensively discussed the mechanisms by which capital structure influences a firm’s value. These include the pecking order theory, agency cost theory, signaling theory, and trade-off theory. Harris and Raviv (Citation1991) categorized these theories into two groups: tax-based and non-tax-based theories. The pecking order, signaling, and agency cost theories fall under the category of non-tax-based theories. On the other hand, the trade-off theory, which considers the benefits of tax shields against the costs of bankruptcy, is a tax-based theory.

All these theories hold relevance in the Omani context, given that corporate tax is levied at a rate of 15% and that there is a separation of ownership and management, as is the case in other jurisdictions. Therefore, this paper reviews these pertinent capital structure theories, placing special emphasis on the agency cost theory. This serves as the theoretical foundation for examining the relationship between corporate governance elements and capital structure decisions.

3.1.1. Agency theory

The agency relation is defined as ‘a contract under which one or more persons the principal(s) engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf (Rashid, Citation2016; Tega, Citation2017) which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent’ (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The theory of agency cost is premised on the notion of interest divergence between principle and agent due to the ownership and management separation. Managers may engage in actions that serve their self-interests and are not particularly in line with the shareholder’s interests. For instance, managers can make decisions about investments that are worthless to shareholder interests, but instead, such decisions may increase manager’s perks and provide job security. The agency problem results in a higher associated agency cost due to the asymmetric information and because of monitoring a manager’s behavior to be in line with shareholders’ interests. The complexity of the principal-agent relationship sheds light on the urgent need to implement a CG system that deals with agency problems in a manner that satisfies the maximum possible number of stakeholders (Madhani, Citation2017). Further, agency costs should be incorporated whenever deciding whether to fiance with debt or equity (Djohaputro, Citation2015). In response to the agency problem, Jensen (Citation1986) argued that debt financing could act as a substitute corporate governance mechanism to align a manager’s behavior and limit the discretion of using free cash to build their own empire. Hence, financing through debt becomes a relevant approach towards increasing the value of the firm, as it subsides the agency conflict (Hussainey & Aljifri, Citation2012).

3.1.2. Signaling theory

In the context of asymmetric information, where managers possess more information about the firm’s activities than shareholders do, capital structure becomes a signaling mechanism. Specifically, a firm’s choice of financing through debt can indicate to external investors that it is capable of meeting its future debt obligations, thereby signaling its future earnings potential (Connelly et al., Citation2011). Moreover, the ability to finance through debt can signal a firm’s capacity to pay dividends to shareholders (Chang & Rhee, Citation1990). Consequently, changes in capital structure serve as indicators of a firm’s financial health, making capital structure decisions relevant to market value.

3.1.3. Pecking order theory

Pecking Order Theory argues that firms prioritize internal sources of financing, such as retained earnings, over external sources like debt and equity issuance. This preference for internal financing is due to the lower associated costs, which include the cost of issuing debt (‘cost of debt’) and the cost of providing adequate returns to shareholders via equity. When internal sources are not sufficient, firms are more likely to opt for debt financing as a secondary option and consider equity issuance as a last resort. The theory, formulated by Myers (Citation1984) and Myers and Majluf (Citation1984), implies that more profitable firms tend to have lower leverage ratios because they can fund themselves through internal sources.

3.1.4. Trade-off theory

Trade-off Theory proposes that firms should aim for a balanced capital structure by weighing the advantages and disadvantages of debt versus equity financing. On one hand, debt financing provides certain benefits, such as the tax shield, which reduces the firm’s tax burden. On the other hand, overreliance on debt increases the risk of bankruptcy. The associated costs of bankruptcy could potentially negate the advantages offered by the tax shield. The theory posits that there exists an optimal leverage ratio, a point at which the incremental costs of bankruptcy are equal to the marginal tax benefits accrued from the use of debt (Dwaikat et al., Citation2014).

3.2. Omani context

3.2.1. Corporate governance and debt structure in Oman

Firms in the MENA region heavily depend on debt to form their capital structure. However, Oman reportedly has an average debt ratio of 47%, one of the highest in the MENA region (Mertzanis et al., Citation2023). The MENA region shares common characteristics that complicate the relationship between corporate governance and capital structure decisions (Oehmichen, Citation2018). For instance, countries in the MENA region have weak corporate governance systems, making it difficult to secure property rights and financial contracts. These countries offer lenient guarantees and collateral against borrowing. The capital markets in these nations are less efficient, and information is generally more asymmetric compared to developed markets (Eldomiaty, Citation2007). These characteristics contribute to an unclear connection between governance and financing decisions in the MENA region (Mertzanis et al., Citation2023).

Furthermore, Feng et al. (Citation2020) argued that centralized ownership, coupled with a lack of external governance mechanisms, may result in an agency problem between major and minor shareholders. This issue becomes significant in financing decisions, as major shareholders may favor debt financing to use the borrowed resources for their own interests, regardless of the potential impact on minor shareholders (i.e. the cost of bankruptcy). Omran et al. (Citation2008) reported that Arab countries, including Oman, are characterized by high ownership concentration and significant state ownership. In such a setting of highly concentrated ownership, the potential for agency problems increases. Major shareholders can use their voting rights to influence management’s decisions towards financing options that serve their own interests. Additionally, GCC countries, including Oman, have a distinct ownership structure characterized by large state ownership (Al-Saidi & Al-Shammari, Citation2015). The average state ownership is estimated to be around 8%. According to institutional theory, the presence of large state ownership can mitigate agency problems, as it reduces asymmetric information and protects the rights of minor shareholders (Pillai & Al-Malkawi, Citation2018). However, Micco et al. (Citation2007) argued that state ownership could lead to conflicts of interest, political interference, and weak managerial oversight, which could exacerbate agency problems. Queiri et al. (Citation2021) empirically substantiated the negative relationship between state ownership and firm performance for firms listed on MSM30.

In relation to Oman, the establishment of corporate governance codes dates back to the 2000s, with Oman being the first country in the region to introduce such codes in 2002, followed by many other countries in the MENA region (Amico, Citation2014). In 2016, a new version of the ‘Code of Corporate Governance for Public Listed Firms’ was issued by the Omani Capital Market Authority. The objective was to establish a binding and optimal framework for corporate governance to ensure fairness, transparency, and accountability in the capital market. This ultimately reduces agency problems and improves overall firm performance. In this regard, the revised code contains specific requirements for board composition. The selection of independent directors follows certain conditions, such as not being executive directors, not owning more than 10% of the firm’s shares (including parent, sister, and subsidiary firms), and representing more than one-third of the board with a minimum of two independent directors. They should also not be a director of the parent company or any subsidiary or associate companies, and should not have been a senior executive of the company or its affiliates during the two years preceding their candidacy or nomination to the board. The board of directors is required to conduct at least four meetings a year. Unlike in Western and Chinese contexts, the code specifies more stringent criteria regarding independent directors’ ownership: it should not exceed 1%, and they should not be among the top 10 shareholders (Feng et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the Omani revised code does not specify board size requirements for listed companies, whereas board sizes in Western countries typically range from 5 to 19 members.

3.2.2. A Glance over MSM 30

The MSM30 index was established in 1992 as a benchmark for assessing the performance of other securities listed on the Muscat Securities Market (MSM). The index comprises 30 firms from diverse industries, which can generally be categorized into financial and non-financial sectors. Companies listed in MSM30 share several common attributes: they are considered to be among the most profitable, liquid, and well-capitalized compared to other firms in the market. The MSM authority follows specific inclusion criteria for firms to be indexed in MSM30. Such firms should have a significant size, represented by a high market capitalization of no less than 40%. Additionally, these firms should demonstrate profitability of at least 15% and a liquidity indicator of 45% or higher (Queiri et al., Citation2021). Over the years, several companies have maintained their listings on the MSM30, becoming primary targets for both local and international investors due to their strong market performance.

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

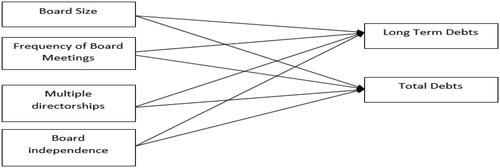

Creating an effective board composition is crucial for mitigating agency problems. Through its various mechanisms (i.e. board size, board meeting frequency, multiple directorships, and director independence), the board can provide effective monitoring systems that enhance a firm’s financial performance, including capital structure decisions (Zaid et al., Citation2020). The following section reviews empirical results concerning board composition and a firm’s capital structure decisions. The following framework is proposed based on the notion of agency cost theory ().

4.1. Board size

Agency theory contends that firms suffer from fundamental agency conflicts between managers and shareholders due to the separation between ownership and control (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). In the same context, Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) provided further insight into this theory by defining agency relationships and identifying agency costs. According to this perspective, the board of directors, including board size decisions, can minimize manager-shareholder agency conflicts through its governance mechanisms. Therefore, it would be theoretically expected that a larger board size uses less debt. Nevertheless, Jensen (Citation1993) argued that larger boards suffer from poor coordination and ineffective monitoring, and thus, firms should have a smaller board size. For a board to function effectively, its size matters. Smaller boards are less likely to experience director free riding. Lipton and Lorsch (Citation1992) and Jensen (Citation1993) suggest that larger boards could be less effective than smaller boards because of coordination problems and director free riding. Larger boards are associated with free-riding on fellow directors’ effort, and therefore, larger boards tend to use more debt to offset the free-riding issue.

Empirical studies investigating the influence of board size on debt ratios yield inconclusive results. in the literature. Empirical studies support a positive relationship between board size and debt ratio (Abor, Citation2007; Nguyen et al., Citation2017). These studies suggest that a larger board size complicates decision-making and increases agency costs. Due to the lack of consensus among large boards on capital structure decisions, firms tend to maintain a higher debt ratio to offset agency costs (Feng et al., Citation2020). Additionally, larger boards are associated with more agency problems that stem from issues related to ownership and corporate control. Consequently, more debt is used to mitigate these agency problems (Rehman et al., Citation2010). Usman et al. (Citation2019) report that a large board size is correlated with a high cost of debt. Therefore, a conclusion can be drawn that the cost of ineffective communication associated with larger boards outweighs their benefits.

Other empirical studies support a negative relationship between board size and debt ratio (Bazhair, Citation2023; Rehman et al., Citation2010; Vakilifard et al., Citation2011). These studies draw upon resource dependence theory, suggesting that a larger board can serve as a resource pool that benefits firms, thus acting as a substitute for high debt ratios. In this way, larger boards can exercise more effective control and supervision, reducing the need for additional debt in the firm’s capital structure, and consequently lowering the cost of debt (Rehman et al., Citation2010; Vakilifard et al., Citation2011). Some empirical evidence from the MENA region—including listed companies in Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Morocco, and the UAE—supports a negative relationship between board size and debt ratio (Mertzanis et al., Citation2023). Similarly, Bazhair (Citation2023) found a negative relationship in a sample of non-financial firms in Saudi Arabia. These studies from the MENA region justify their findings through resource dependence theory.

Given these varying perspectives and drawing on agency theory, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1: Board size is associated with the debt ratio for firms listed on the MSM30.

4.2. Board meeting frequency

The agency theory posits that debt functions as a disciplinary measure to restrain managerial actions that deviate from the objective of maximizing shareholders’ wealth. The implementation of corporate governance mechanisms suggests that an increase in board meetings would lead to a rise in the utilization of debt in accordance with the disciplinary concept (Jensen, Citation1986). Consequently, board meeting frequency is theoretically anticipated to have a positive correlation with the use of debt. However, the argument, drawn from foundational works by Jensen (Citation1993) and Vafeas (Citation1999), asserts that frequent board meetings may not necessarily exert substantial control. This is because board directors are often too occupied to fully comprehend all the issues related to the firm, leading to a hesitancy in making decisions regarding increased debt issuance that could potentially benefit shareholders. Therefore, these seminal works empirically found that the frequency of board meetings reduces a firm’s reliance on debt. It is noteworthy that chief executive officers typically set the agenda for board meetings (Jensen, Citation1993). Also, routine tasks absorb much of the meetings limiting opportunities for outside directors to exercise meaningful control over management. In line with this argument, Ezeani et al. (Citation2023), using samples from the UK, France, and Germany, found a consistent negative relationship between board meeting frequency and debt ratio. Across all these countries, increased board meeting frequency was correlated with reduced usage of debt by firms.

Another argument presented by Conger et al. (Citation1998; Sharma et al., Citation2009) regarding the potential positive relationship between board meeting frequency and the use of debt is rooted in the idea of benefiting shareholders’ perspectives. According to this viewpoint, frequent board meetings are considered a means to effectively supervise managers, resulting in favorable outcomes for the firms’ shareholders. In the context of the Anglo-Saxon corporate governance approach, it is expected that the frequency of board meetings will exhibit a positive correlation with leverage.

Specific to Oman, board meeting should happen at least 4 times annually. But board members are often serve on multiple boards, as indicated by Al-Matari (Citation2020) and Queiri et al. (Citation2021). The revised Corporate Governance (CG) regulations neither specifically prohibit multiple directorships nor provide guidelines about them. Due to this business and multiple directorship, we expect similar to the seminal works of Jensen (Citation1993) and Vafeas (Citation1999) that board meetings frequency is associated with the use of debt. Given these contradictory findings, the following hypothesis, based on agency theory, will be tested for firms listed on the MSM30:

H2: Board meeting frequency is associated with the debt ratio for firms listed on the MSM30.

4.3. Multiple directorship

Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) argued that to curb agency conflict and to limit resultant agency costs, considerable focus is placed on the monitoring role of the board. Boards of directors are responsible for providing an effective monitoring mechanism over managers’ activities to mitigate consumption (Trinh et al., Citation2020). The busyness hypothesis postulates that if directors become overcommitted, they might become less effective corporate monitors (Clements et al., Citation2015). Therefore, directors with multiple directorships are likely to employ more debts to offset their busyness and curb managerial activities through introducing debt as a disciplinary mechanism. On the other hand, Jensen (Citation1993) and Vafeas (Citation1999), asserted that board directors are often too busy to fully understand all the firm’s related issues, which can result in a reluctance to make decisions about increasing debt issuance that would likely benefit the shareholders. instead, these seminal works empirically found that board meetings’ frequency reduces firms’ use of debt.

Different from the notion of agency theory, another argument provided by Fama (Citation1980), Fama and Jensen (Citation1983) argued that a busy board that have a number of director memberships, can be an indication of his reputation as an effective monitoring of corporate managers. Taking together, the managerial power theory with this positive view, we can theoretically expect a negative relationship between multiple directorships and the use of debt. Stearns and Mizruchi (Citation1993) posited those directors with multiple directorships often termed ‘board interlocking’—facilitate greater access to capital, especially when those directors also serve on the boards of financial institutions. As a result, such boards are more likely to employ debt, given their enhanced access to bank loans. From the ‘signaling quality’ hypothesis perspective, Trinh et al. (Citation2020) found a negative association between directors with multiple seats and debt ratio in both conventional and Islamic banks. Busy boards of directors aim to enhance firm’s financing capacity through the reduction of the cost of debt, which is achieved by issuing less debt.

In the context of Oman, directors are allowed to serve on multiple boards prior to the reforming of the corporate governance code of conduct. These directors, often referred to as ‘busy directors’, are frequently not fully engaged. The relationship between multiple directorships and a firm’s financial performance has been reported to be negative within the MSM30 context (Queiri et al., Citation2021). According to the argument presented by the agency theory, multiple directorships could result in increasing or decreasing the amount of debts. In light of these conflicting findings, our third hypothesis, rooted in the agency cost assumption, is as follows:

H3: Multiple directorships is associated with the debt ratio for firms listed on the MSM30.

4.4. Board independence

Most of the responsibility for monitoring management and mitigating agency problems falls to independent directors (Ngatno et al., Citation2021). From this sense, Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) and Jensen and Murphy (Citation1990), argued that a high proportion of independent directors on a board serves as a mitigator for agency problems. This is because independent directors are generally well compensated and are thus inclined to act in the best interests of shareholders, often advocating for more debt to reduce agency costs. Given that independent directors typically do not have conflicts of interest with shareholders, they act as vigilant monitors and encourage managers to issue more debt. Their role enhances the internal corporate governance mechanisms (Hillman & Dalziel, Citation2003). Empirical studies such as Bazhair (Citation2023), Amin et al. (Citation2022), Abor (Citation2007), Kyriazopoulos (Citation2017), and Tarus and Ayabei (Citation2016) have found a positive relationship between board independence ratio and debt ratio. This positive association supported the argument that outside directors are active monitors of management. Thus, these directors tend to compel managers to employ high leverage to boost firms’ value.

However, the literature also reports a negative relationship between these two variables, as seen in studies conducted on samples from the MENA region (Mertzanis et al., Citation2023; Sani, Citation2020). Researchers who have found a negative association argue that independent directors aim to avoid the uncertainties associated with debt issuance. Instead, they seek to improve the firm’s financial performance by acquiring more equity when forming the capital structure (Ferriswara et al., Citation2022). Feng et al. (Citation2020) interpret this as the establishment of a trusting relationship between shareholders and independent directors, which enables the latter to secure funds from equity sources. Additionally, Boateng et al. (Citation2017) posit that independent directors exercise stringent oversight over managers, who consequently opt for less debt to sidestep excessive risk and debt-related disciplinary actions. In light of these diverse findings, our fourth hypothesis, grounded in agency theory, is formulated as follows:

H4: board independence is associated with the debt ratio for listed firms in MSM30

4.5. Control variables

Variables such as profitability, firm size, and growth are well-documented in the literature as influencing the amount of debt a firm takes on. (i) Profitability: the trade-off theory suggests that profitable firms use a high amount of debt because larger firms benefit from lower costs of debt due to economies of scale. Conversely, the pecking order theory proposes that profitable firms prefer to use retained earnings instead of external financing sources (Hussainey & Aljifri, Citation2012). Korzama (Citation2016) evidenced that both the return on investment and the return on assets negatively affect the leverage ratio in the Turkish manufacturing sector. In the same line, by Vy (Citation2016) evidenced that, for Vietnami companies, profitable firms tend to have a higher incentive to use less debt. (ii) The firm size: Vy (Citation2016) evidenced that the firm size negatively affects the debt ratio this might be justified that large firms seem indifferent to the usage of debt as they have greater access to other sources of finance. iii) The growth: Firms experiencing high growth often face asset substitution and underinvestment issues, making them less attractive to lenders. As a result, such firms tend to have lower amounts of debt (Agyei et al., Citation2020). Additionally, this study employed a different group of control variables including year and industry –specific fixed effects. According to Mansour et al. (Citation2023), the industry specific fixed effects is required to be incorporated in the regression models to capture the influence of competition changes on the COD financing within industries. Furthermore, Psillaki and Daskalakis (Citation2009) argued that capital structure formation is influenced by industry specific business risk (a higher industry business risk is accompanied by more use of leverage). Therefore, to neutralize the industry fixed effects, it was controlled for in the regression models.

4.6. Debt and dividends interrelation

The literature establishes a link between dividend policy and debt ratio. The negative relationship between dividend payouts and the debt ratio is explained through the agency cost theory of dividends (Rozeff, Citation1982). Paying dividends to shareholders can reduce agency costs by minimizing the firm’s free cash, which managers might otherwise use for tunneling activities (Ain et al., Citation2021). Therefore, dividend payouts serve as a substitute mechanism for debt issuance, resulting in a negative correlation between dividends and debt. However, when managers are entrenched (i.e. managerial ownership is high), dividends are paid to complement debt as a means of reducing agency costs (Ghasemi et al., Citation2018). The entrenchment hypothesis suggests that dividends and debt are positively related and complement each other in curbing managerial tunneling activities.

Furthermore, the positive relationship between dividends and debt is also explained through signaling theory (Chang & Rhee, Citation1990). Firms with a high debt ratio tend to pay more dividends to signal their financial health to the market. Moreover, firms may issue debt to meet shareholders’ expectations of regular dividends, thereby sending a signal about their financial health (Ang & Ciccone, Citation2006).

The preceding discussion indicates that dividends and debt are interrelated. In this regard, Ghasemi et al. (Citation2018) found that dividends and debt have a bidirectional causal relationship when applying a simultaneous equations model. Therefore, our analytical model will account for this simultaneity by testing whether the dividend payout ratio is an endogenous variable or not. Based on the results of the endogeneity analysis, a suitable regression technique—either OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) or 2SLS (Two-Stage Least Squares)—will be employed to account for simultaneity. Details on the endogeneity test will be further elaborated in the data analysis and results sections.

5. Research design

5.1. Sample selection and data collection

Data were collected from the publicly available annual reports on the MSX website, which are reported across a span of seven years (from 2009 to 2015). The sample for this study comprises firms listed on the MSM30 index, with the exclusion of those belonging to the financial sector. Instead, the sample is made up of firms from the service and industrial sectors that are listed on the MSM30. Corporate finance literature emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between financial and non-financial sectors when selecting a sample (Dalwai & Mohammadi, Citation2020; Al-Matari, Citation2020). Based on these criteria, 19 firms were initially included in the sample. However, 5 of these were excluded due to incomplete data, leaving a final sample of 14 firms. Data were collected for the period from 2009 to 2015 using publicly available annual reports. A new corporate governance code was introduced in 2015 and became effective in 2016. Therefore, our data collection was limited to the period up to 2015 to ensure consistency with the findings of this study.

5.2. Measurement of variables

provides a comprehensive list of the symbols and proxies used for corporate governance compositions and control variables in this study. The debt ratio is measured using two different proxies, resulting in two separate regression models.

Table 1. Measurement of variables.

5.3. Data analysis technique

Several diagnostic tests were conducted in this study to ensure the goodness of fit for the proposed models. These tests include assessments for normality, multi-collinearity, and heteroscedasticity. An endogeneity test was also performed to address potential biases that could arise from simultaneity issues between dividends and debt. Depending on the results of the endogeneity test, an appropriate regression model will be selected for this study. If dividends are found to be an endogenous variable, using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) technique for data analysis would yield biased results, as this technique does not account for reverse causality and simultaneity. In such a case, the Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) analysis would be a more robust choice for data analysis. The 2SLS method corrects for simultaneity, omitted variables, or measurement errors (Pillai & Al-Malkawi, Citation2018). (2SLS) method is used because it can produce consistent estimates of the parameters when the system is identifiable (Chen et al., Citation2018), therefore, using (2SLS) enabled us to have consistent results. All diagnostic tests and regression models were conducted using STATA software (the authors have ensured the use of the genuine edition of this software in line with copyrights law).

6. Empirical results and discussion

This section presents the results of the study, which includes the outcomes of several diagnostic tests, such as heteroscedasticity and endogeneity. The proposed hypotheses are also tested, and the findings are reported accordingly.

6.1. Descriptive statistics

provides descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study. For MSM30, the average debt ratio, measured using long-term debt and a combination of short and long-term debt, is 14.8% and 23.7%, respectively. On average, firms listed on MSM30 use less debt—’low gearing’—compared to the overall market average of approximately 47% (Mertzanis et al., Citation2023). Firms listed on MSM30 are considered to be the most profitable and liquid among other firms listed on the Muscat Capital Market, which might explain their lower tendency to be highly geared. Additionally, these firms have an average ROA of 10.5%.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

The ratio of independent directors is high, with 78.33% of the total board being outsiders. This aligns with the requirements of the Corporate Governance (CG) code of conduct (Capital Market Authority-Sultanate of Oman, Citation2015), which emphasizes the role of independent directors in effectively monitoring a firm’s activities. It is also noteworthy that, on average, 59.5% of directors hold multiple seats. The CG code of conduct in Oman does not have specific requirements prohibiting board members from serving on other firms’ boards, which explains the high percentage of multiple directorships.

The average board size for firms listed on MSM30 is between 7 and 8 members, consistent with the board size requirements stated in the CG code of conduct. These firms also pay dividends to their shareholders, with an average of 0.056 baisa per share. As mentioned earlier, these firms may pay dividends, either to signal their financial health, or to mitigate agency costs, through dividend payments. This could either complement or substitute for the use of debt as a financing mechanism.

6.2. Heteroscedasticity and multicollinearity tests

The heteroscedasticity tests were used in the two models (i.e. using two proxies of debt ratio). The test holds the following assumption:

Ho: Constant variance

Table 3. Heteroscedasticity test.

According to Hair et al. (Citation2016), VIF values should be less than 5 to safeguard against multicollinearity biasness. shows that the variables adopted in the model of study demonstrate that multicollinearity is not an issue for this data set, as all VIF values fall below 5.

Table 4. Multicollinearity test.

6.3. Endogeneity test

The literature suggests that debt and dividend per share have a two-way causal relationship, leading to simultaneous effects. in the academic literature it is established that debt and dividends are interrelated (Faulkender & Wang, Citation2006; Kim Ph et al., Citation2007). The main findings of Ghasemi et al. (Citation2018) indicates that when dividend is treated as endogenous, there is a positive impact on leverage. However, leverage is found to have a simultaneous negative impact on dividends. Implementing the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) technique in the presence of simultaneity will produce biased results. Therefore, dividends will be tested as an endogenous variable in relation to the debt ratio, using the two proposed proxies. The endogeneity of dividends is tested using the Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) technique with the following assumption:

H0: Dividend is an exogenous variable.

H0: The instruments are valid.

Table 5. Endogeneity tests.

6.4. Correlation analysis

and present the correlation analysis for both models. There is an absence of multi-collinearity since the correlation between any two independent variables does not exceed the value of .8 (Gujarati and Porter, Citation2010). shows that there is a negative association between dividends, multiple directorships and return on assets. On the other hand, a positive association was found between long term debts and board size, firm size, board independency. shows similar correlational direction between DV (total debts) and the predictors used in the model.

Table 6. Correlation analysis for model 1.

Table 7. Correlation analysis for model 2.

6.4. OLS estimator

presents the regression results using the OLS estimator. While the OLS method holds an advantage over non-linear estimations with fixed effects in computing regression coefficients, errors in measuring the explanatory variable can introduce biases. Such errors may infiltrate the residuals, posing a risk of correlation with the predictor during regression. Therefore, we aimed to enhance the robustness of our OLS outcomes by addressing these measurement errors. We made efforts to rectify our predictors against these errors through an alternative coefficient estimation method, ensuring the robustness of OLS. The analytical process required addressing the endogeneity dilemma. The connections between leverage and dividends have also been highlighted, suggesting a reciprocal causal relationship when employing a simultaneous equations model (Ghasemi et al., Citation2018). The use of the OLS estimator, as shown in , resulted in inconsistent predictions and changes in direction across the two models.

Table 8. OLS regression results.

6.5. Two stage least square (2SLS) regression and sensitivity analysis to OLS results

displays the regression results using the 2SLS technique for both models, utilizing different proxies for the debt ratio. The adoption of 2SLS regression was employed to guard against the causal reverse effects between debts and dividends and to address the mentioned shortcomings of the OLS estimator. The endogeneity analysis indicated that dividend payment is an endogenous variable. Consequently, the utilization of 2SLS regression is expected to yield less biased results compared to OLS.

Table 9. 2SLS regression results.

Board independence and board size consistently show a positive and significant association with the two proxies of debt ratio (L_D and S&T_D). Multiple directorships have a positive and significant association only with long-term debt. Conversely, the frequency of board meetings consistently shows a negative and significant association with both debt ratio proxies. Among the control variables, dividends per share are found to have a negative and significant association with long-term debt. Additionally, firm size emerges as a positive and significant predictor of both proxies of debt ratio. Utilizing the variables in this study, both models were able to explain 59.59% and 56.91% of the variation in debt ratio, respectively.

Board size was found to have a positive association with the debt ratio, supporting Hypothesis 1 (H1). In Oman, boards tend to have a sizable number of directors. This study’s findings align with the empirical results of Lipton and Lorsch (Citation1992), Jensen (Citation1993), Nguyen et al. (Citation2021) and Abor (Citation2007), who argued that a smaller board size is more effective than large one, hence, debt issuance, could serve as a substitute mechanism to address the complexity of large board size and its inability to reach a consensus on capital structure decisions. our findings contrast with those of Mertzanis et al. (Citation2023) and Bazhair (Citation2023), who observed a negative association between board size and debt ratio for a sample of non-financial firms in the MENA region and Saudi Arabia. Consequently, the resource dependence theory did not find support in the context of MSM30. Instead, the results of this study are more aligned with agency theory.

The agency theory contends that debt would act as a disciplinary mechanism to curb managerial activities that does not align with the concept of shareholders’ wealth maximization. The use of corporate governance mechanism indicates that board meeting will result in increasing the use of debt in line with notion of disciplinary mechanism (Jensen, Citation1986). Therefore, board meeting frequency is theoretically expected to have a positive relationship with the use of debt. However, the argument developed based on seminal works by Jensen (Citation1993) and Vafeas (Citation1999), asserted that frequent board meetings do not necessarily exert meaningful control. This is because board directors are often too busy to fully understand all the firm’s related issues, which can result in a reluctance to make decisions about increasing debt issuance that would likely benefit the shareholders. Therefore, these seminal works empirically found that board meetings’ frequency reduces firms’ use of debt. Chief executive officers almost always set the agenda for board meetings (Jensen, Citation1993). Moreover, routine tasks absorb much of the meetings limiting opportunities for outside directors to exercise meaningful control over management. In line with this argument, Ezeani et al. (Citation2023), using samples from the UK, France, and Germany, found a consistent negative relationship between board meeting frequency and debt ratio. Across all these countries, increased board meeting frequency was correlated with reduced usage of debt by firms.

The second hypothesis on the association between board meeting frequency and debt ratio received supports, our results indicate a negative association. This negative association is consistent with the findings of Jensen (Citation1993), Vafeas (Citation1999), and Ezeani et al. (Citation2023). Given this negative relationship, it could be argued that frequent board meetings are not an effective mechanism for meaningful control. Rather, the results suggest that board members are often too busy to fully understand all the firm’s related issues and they become reluctant to make the decision on increasing the debt. The findings of this study contradict the findings of (1986) who argued that greater number of board meetings can increase the use of debt as an effective mechanism of corporate governance.

Furthermore, Ezeani et al. (Citation2023) argued on the negative association between board meetings and debt that board meeting is an effective control mechanism within a stakeholder approach to corporate governance. Therefore, firms in MSM30 may be less concerned with shareholder benefits and are less likely to issue more debt solely for shareholders’ benefit. In this respect, MSM30 shares characteristics with European countries like Germany, France, and the UK, where a negative association between board meeting frequency and debt ratio has been observed.

Our third hypothesis was supported: there is a positive association between multiple directorships and debt ratio. This finding is in line with Jensen (Citation1993) and Vafeas (Citation1999), Trinh et al. (Citation2020), and Clements et al. (Citation2015). The ‘busyness hypothesis’ could explain this positive relationship, suggesting that directors with multiple seats tend to issue more debt as a substitute mechanism to compensate for their limited availability and the potential agency problems arising from ineffective monitoring. Oman does not have specific rules prohibiting multiple directorships, allowing directors to serve on multiple boards, which may increase their busyness.

The fourth hypothesis was also supported, showing a positive association between the board independence ratio and the debt ratio. This finding is consistent with previous studies, such as those by Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976), Bazhair (Citation2023), Abor (Citation2007), Kyriazopoulos (Citation2017), and Tarus and Ayabei (Citation2016). The ‘active monitors’ hypothesis found support in the context of MSM30. Independent directors, with their professional knowledge and experience, can effectively monitor managers and therefore make objective assessments of the firm’s policy decisions. Such active monitoring encourages independent directors to opt for debt financing as a means to exert more disciplinary pressure on managers, as posited by agency theory. The Omani Corporate Governance (CG) code places great emphasis on the selection of independent directors to enhance the board’s monitoring effectiveness and reduce agency conflicts. These selection criteria have contributed to improving the board’s efficacy in reducing conflicts of interest.

7. Summary and conclusion

This study examined the association between board composition and capital structure decisions, grounded in the principles of agency theory. The assumption is that mechanisms like board size, board independence, board meeting frequency, and multiple directorships can effectively reduce agency problems by influencing debt levels to curb managerial tunneling activities. To some extent, our results confirm this assumption. Firstly, board independence serves as an effective tool for mitigating agency problems; a higher proportion of independent directors influences a firm’s decision to utilize more debt, thereby inducing managers to adhere to debt discipline. Therefore, the emphasis on the role of independent directors in Oman’s revised Corporate Governance (CG) code is warranted. Secondly, board meeting frequency negatively associated with debt ratio, indicating that such meetings may not reduce agency problems between managers and shareholders. Thirdly, a positive association between board size and debt ratio suggests that larger boards is associated with decision-making complexity, therefore, they employ debt as a disciplinary substitute, corroborating agency theory over resource dependence theory in the context of MSM30. Fourthly, directors with multiple seats are more likely to use debt as a disciplinary substitute, presumably to offset their lack of availability for effective monitoring ‘busy directors’.

Overall, this study validates agency theory in the context of MSM30. Firms listed on MSM30 frequently use debt as a substitute for mitigating various issues, including ‘director busyness’ and the complexities of large board sizes. There is evidence to suggest that weaker corporate governance practices necessitate greater use of debt as a disciplinary mechanism. In general, emerging markets in the MENA region are undergoing intensive reforms to align with developed countries. However, the inclusion of independent directors appears to be the most effective strategy for mitigating agency problems in MSM30, thanks to the principle of ‘active monitoring’.

Relying on debt as a disciplinary substitute should be minimized, with the primary focus shifted to effective board monitoring. Policymakers might consider revising board size requirements and issuing guidelines on multiple directorships to foster more active monitoring and, thus more effective corporate governance. From a practical standpoint, this study supports strengthening Oman’s CG code to enhance financial performance and minimize agency conflicts. While reforms were made in 2015, further improvements are needed. In response to this, a new corporate of governance code of conduct has been issued in 2021 for firms who have a government ownership. This new code of conduct is believed to strengthen the corporate governance mechanism, reducing agency problems and improve financial performance.

This study comes with several limitations; first the empirical analysis has a sample size of 98 observations, which is considered relatively a small simple size. Second, the effects of ownership structure on capital structure decision was not investigated in this study. Third, robustness of our analysis against timing and non-linear effects were not investigated in this study. Instead, we limit the robustness of our analysis against different estimators (OLS vs. 2SLS).

Future studies on capital structure should incorporate more ownership structure variables and to increase the number of observations. In additions, future studies may address the impact of corporate governance variables on another important corporate financial decisions, including but not limited to dividends policy. Other important area of research is the board diversity and how it effects corporate financial decision in Omani and GCC contexts. Moreover, there is a need to conduct further studies on how the macro-financial conditions and financial regulations impact on firms’ financing decision.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to developing this manuscript in one way or another. Abdelbaset and Nizar have contributed to the conception design of data. Baligh has contributed to critically reviewing the intellectual content of this manuscript and Araby has contributed to data interpretation and final approval of the version to be published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data of this article were extracted from the annual and financial reports which are available on the Muscat Security Market website (https://www.msx.om/). The data is accessible from the website for the audience (open source). There is no privacy concern or restriction to share this data if it is requested.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdelbaset Queiri

Abdelbaset Queiri is an Assistant Professor in College of Commerce and Business Administration at Dhofar University. He has more than 30 published articles and sizable number of conference participation. His publications is indexed in Scopus, ProQuest and other reputable indexes.

Araby Madbouly

Araby Madbouly is the Head of the Business and Accounting Department at Muscat College, since 2017. He is an external reviewer in the Oman Authority of Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance (OAAAQA). He was the Dean of Admission and Registration at the UoJ-UAE. He holds a Ph.D. degree in Economics.

Nizar Dwaikat

Nizar Dwaikat works as an Associated Professor in Arab Open University and He is the Acting Director of Arab Open University – Palestine Branch. His interest covers research areas related to dividends policy, IP O firms, ownership structure and firms’ financial performance.

Uvesh Husain

Uvesh Husain currently working as an associate professor at Mazoon College, Oman. He has Ph.D. in Commerce. Dr. Uvesh has more than 20 publications in peer reviewed journals, and He has a special interest in microfinance, investment and international finance topics.

References

- Abor, J. (2007). Corporate governance and financing decisions of Ghanaian listed firms. Corporate Governance, 7(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700710727131

- Abor, J. (2008). Agency theoretic determinants of debt levels: evidence from Ghana. Review of Accounting and Finance, 7(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/14757700810874146

- Ain, Q., Alam, M., & Anas, S. M. (2021). Response of two-way RCC slab with unconventionally placed reinforcements under contact blast loading. In International Conference on Advances in Structural Mechanics and Applications (pp. 219–238). Springer International Publishing.

- Al Ani, M., & Al Amri, M. (2015). The determinants of capital structure: an empirical study of Omani listed industrial companies. Verslas: Teorija ir Praktika, 16(2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2015.471

- Al-Saidi, M., & Al-Shammari, B. (2015). Ownership concentration, ownership composition and the performance of the Kuwaiti listed non-financial firms. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 25(1), 108–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCOMA-07-2013-0065

- Agyei, J., Sun, S., & Abrokwah, E. (2020). Trade-off theory versus pecking order theory: Ghanaian evidence. Sage Open, 10(3), 2158244020940987.

- Amico, A. (2014). The role of MENA stock exchanges in corporate governance. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCOMA-07-2013-0065

- Amin, A., Ur Rehman, R., Ali, R., & Mohd Said, R. (2022). Corporate governance and capital structure: Moderating effect of gender diversity. SAGE Open, 12(1), 215824402210821. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221082110

- Ang, J., & Ciccone, S. (2006). Issuing debt to pay dividends. Financial Management Association.

- Al-Matari, E. M. (2020). Do characteristics of the board of directors and top executives have an effect on corporate performance among the financial sector? Evidence using stock. Corporate Governance, 20(1), 16–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-11-2018-0358

- Bazhair, A. H. (2023). Board governance mechanisms and capital structure of Saudi non-financial listed firms: A dynamic panel analysis. SAGE Open, 13(2), 215824402311729. 21582440231172959. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231172959

- Bawazir, H., Khayati, A., & AbdulMajeed, F. (2021). Corporate governance and the performance of non-financial firms: The case of Oman. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(4), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2021.8.4(36)

- Berger, J., & Heath, C. (2007). Where consumers diverge from others: Identity signaling and product domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1086/519142

- Boateng, P. Y., Ahamed, B. I., Soku, M. G., Addo, S. O., & Tetteh, L. A. (2022). Influencing factors that determine capital structure decisions: A review from the past to present. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2152647. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2152647

- Boateng, A., Cai, H., Borgia, D., Gang Bi, X., & Ngwu, F. N. (2017). The influence of internal corporate governance mechanisms on capital structure decisions of Chinese listed firms. Review of Accounting and Finance, 16(4), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAF-12-2015-0193

- Capital Market Authority-Sultanate of Oman. (2015). Code of corporate governance for public listed companies. https://e.cma.gov.om/Content/PDF/CorporateGovernanceCharterEn.pdf

- Chang, R. P., & Rhee, S. G. (1990). The impact of personal taxes on corporate dividend policy and capital structure decisions. Financial Management, 19(2), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3665631

- Chen, C., Ren, M., Zhang, M., & Zhang, D. (2018). A two-stage penalized least squares method for constructing large systems of structural equations. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 19, 1–34.

- Clements, C., Neill, J. D., & Wertheim, P. (2015). Multiple directorships, industry relatedness, and corporate governance effectiveness. Corporate Governance, 15(5), 590–606.

- Conger, J. A., Finegold, D., & Lawler, E. E. (1998). Appraising boardroom performance. Harvard Business Review, 76(1), 136–148.

- Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419

- Dalwai, T., & Mohammadi, S. S. (2020). Intellectual capital and corporate governance: An evaluation of Oman’s financial sector companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 21(6), 1125–1152. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2018-0151

- De La Bruslerie, H. (2016). Does debt curb controlling shareholders’ private benefits? Modelling in a contingent claim framework. Economic Modelling, 58, 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.06.002

- Djohaputro, B. (2015). The dominance of the Agency Model on financing decisions. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 17(2), 157–178.

- Dwaikat, N. (2023). The impact of corporate governance on cash holdings in the context of Oman. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business (JAFEB), 10(1), 67–77.

- Dwaikat, N. K., Queiri, A. R., & Aziz, M. N. (2014). Capital structure of family companies. International Conference on Business, Law and Corporate Social Responsibility 1(2), 127–132.

- Eldomiaty, T. I. (2007). Determinants of corporate capital structure: Evidence from an emerging economy. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 17(1/2), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/10569210710774730

- Ezeani, E., Kwabi, F., Salem, R., Usman, M., Alqatamin, R. M. H., & Kostov, P. (2023). Corporate board and dynamics of capital structure: Evidence from UK, France and Germany. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 28(3), 3281–3298. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2593

- Fama, E. F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), 288–307.

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325.

- Faulkender, M., & Wang, R. (2006). Corporate financial policy and the value of cash. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1957–1990.

- Feng, Y., Hassan, A., & Elamer, A. A. (2020). Corporate governance, ownership structure and capital structure: Evidence from Chinese real estate listed companies. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 28(4), 759–783. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-04-2020-0042

- Fernández, V., & Brown, P. H. (2013). From plant surface to plant metabolism: The uncertain fate of foliar-applied nutrients. Frontiers in Plant Science, 4, 289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00289

- Ferriswara, D., Sayidah, N., & Agus Buniarto, E. (2022). Do corporate governance, capital structure predict financial performance and firm value? (Empirical study of Jakarta Islamic index). Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2147123. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2147123

- Florackis, C., & Ozkan, A. (2009). The impact of managerial entrenchment on agency costs: An empirical investigation using UK panel data. European Financial Management, 15(3), 497–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-036X.2007.00418.x

- Ghasemi, M., Razak, N., & Muhamad, J. (2018). Dividends, leverage and endogeneity: A simultaneous equations study on Malaysia. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 12(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v12i1.4

- Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1982). Corporate financial structure and managerial incentives. In The economics of information and uncertainty (pp. 107–140). University of Chicago Press.

- Gujarati, D., & Porter, D. C. (2010). Functional forms of regression models. Essentials of Econometrics, 4th ed., 132–177.

- Hair, Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-P LS: part I–method. European business review, 28(1), 63–76.

- Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (1991). The theory of capital structure. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 297–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb03753.x

- Hashim, H. A., & Amrah, M. (2016). Corporate governance mechanisms and cost of debt: Evidence of family and non-family firms in Oman. Managerial Auditing Journal, 31(3), 314–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-12-2014-1139

- Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.10196729

- Hussainey, K., & Aljifri, K. (2012). Corporate governance mechanisms and capital structure in UAE. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 13(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/09675421211254849

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Jensen, M. C., & Murphy, K. J. (1990). Performance pay and top-management incentives. Journal of Political Economy, 98(2), 225–264. https://doi.org/10.1086/261677

- Jensen, M. C. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. The Journal of Finance, 48(3), 831–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1993.tb04022.x

- Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review, 76(2), 323–329.

- Júnior, D. M. B. (2022). Corporate governance and capital structure in Latin America: Empirical evidence. Journal of Capital Markets Studies, 6(2), 148–165.

- Khaki, A. R., & Akin, A. (2020). Factors affecting the capital structure: New evidence from GCC countries. Journal of International Studies, 13(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2020/13-1/1

- Kim Ph, Y. H., Rhim, J. C., & Friesner, D. L. (2007). Interrelationships among capital structure, dividends, and ownership: evidence from South Korea. Multinational Business Review, 15(3), 25–42.

- Korzama, o. (2016). The effects of profitability ratios on debt ratio: The sample of the best manufacturing industry. Financial Studies, 2, 35– 54.

- Kyriazopoulos, G. (2017). Corporate governance and capital structure in the periods of financial distress. Evidence from Greece. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 14(1), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.14(1-1).2017.12

- Lipton, M., & Lorsch, J. W. (1992). A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. The Business Lawyer, 59–77.

- Madhani, P. M. (2017). Diverse roles of corporate board: A review of various corporate governance theories. Journal of Corporate Governance, 16(2), 7–28.

- Manu, R. E. H. R., Alhabsji, T., Rahayu, S., & Nuzula, N. (2019). The effect of corporate governance on profitability, capital structure and corporate value. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 10(8), 202–214.

- Mansour, M., Al Zobi, M., Saleh, M. W. A., Al-Nohood, S., & Marei, A. (2023). The board gender composition and cost of debt: Empirical evidence from Jordan. Business Strategy & Development, 7(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.300

- Mertzanis, C., Nobanee, H., Basuony, M. A., & Mohamed, E. K. (2023). Enforcement, corporate governance, and financial decisions. Corporate Governance, 23(5), 1175–1216. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-11-2021-0435

- Micco, A., Panizza, U., & Yañez, M. (2007). Bank ownership and performance. Does politics matter? Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(1), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.02.007

- Mitton, T. (2004). Corporate governance and dividend policy in emerging markets. Emerging Markets Review, 5(4), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2004.05.003

- Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review, 48(3), 261–297.

- Mohammadi, S. S., Dalwai, T., Najaf, D., & Al-Yaarubi, A. S. (2020). Determinants of capital structure: An empirical evaluation of Oman’s tourism companies. International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews, 7(1), 01–10. https://doi.org/10.18510/ijthr.2020.711

- Morellec, E., Nikolov, B., & Schürhoff, N. (2012). Corporate governance and capital structure dynamics. The Journal of Finance, 67(3), 803–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01735.x

- Myers, S. C. (1984). Finance theory and financial strategy. Interfaces, 14(1), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.14.1.126

- Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of financial economics, 13(2), 187–221.

- Ngatno, Apriatni, E. P., & Youlianto, A. (2021). Moderating effects of corporate governance mechanism on the relation between capital structure and firm performance. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1866822. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1866822

- Nguyen, T., Bai, M., Hou, Y., & Vu, M. C. (2021). Corporate governance and dynamics capital structure: evidence from Vietnam. Global Finance Journal, 48, 100554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2020.100554

- Nguyen, N. T. P., Nguyen, L. P., & Dang, H. T. T. (2017). Analyze the determinants of capital structure for Vietnamese real estate listed companies. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(4), 270–282.

- Oehmichen, J. (2018). East meets west—Corporate governance in Asian emerging markets: A literature review and research agenda. International Business Review, 27(2), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.09.013

- Omran, M. M., Bolbol, A., & Fatheldin, A. (2008). Corporate governance and firm performance in Arab equity markets: Does ownership concentration matter? International Review of Law and Economics, 28(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2007.12.001

- Pillai, R., & Al-Malkawi, H. A. N. (2018). On the relationship between corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from GCC countries. Research in International Business and Finance, 44, 394–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.110

- Porta, R. L., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1155. https://doi.org/10.1086/250042

- Psillaki, M., & Daskalakis, N. (2009). Are the determinants of capital structure country or firm specific? Small Business Economics, 33(3), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9103-4

- Purag, M. B., Abdullah, A. B., & Bujang, I. (2016). Corporate governance and capital structure of Malaysian family-owned companies. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 11(1), 18–30.

- Queiri, A., Madbouly, A., Reyad, S., & Dwaikat, N. (2021). Corporate governance, ownership structure and firms’ financial performance: insights from Muscat securities market (MSM30). Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 19(4), 640–665. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-05-2020-0130

- Rashid, A. (2016). Managerial ownership and agency cost: Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(3), 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2570-z

- Rehman, M. A., Rehman, R. U., & Raoof, A. (2010). Does corporate governance lead to a change in the capital structure. American Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 1(2), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.5251/ajsms.2010.1.2.191.195

- Ronald, C. A., Sattar, A. M., & David, M. R. (2004). Board characteristics, accounting report integrity, and the cost of debt. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 37(3), 315–342.

- Rozeff, M. S. (1982). Growth, beta and agency costs as determinants of dividend payout ratios. Journal of Financial Research, 5(3), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6803.1982.tb00299.x

- Sharma, V., Naiker, V., & Lee, B. (2009). Determinants of audit committee meeting frequency: Evidence from a voluntary governance system. Accounting Horizons, 23(3), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2009.23.3.245

- Shehata, N. (2013). Corporate governance disclosure in the Gulf countries [Doctoral dissertation]. Aston University.

- Sani, A. (2020). Managerial ownership and financial performance of the Nigerian listed firms: The moderating role of board Independence. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 10(3), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v10-i3/7821

- Singh, D. (2016). A panel data analysis of capital structure determinants: An empirical study of non-financial firms in Oman. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(4), 1650–1656.

- Stearns, L. B., & Mizruchi, M. S. (1993). Board composition and corporate financing: The impact of financial institution representation on borrowing. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 603–618. https://doi.org/10.2307/256594

- Tarus, D. K., & Ayabei, E. (2016). Board composition and capital structure: Evidence from Kenya. Management Research Review, 39(9), 1056–1079. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2015-0019

- Tega, L. A. (2017). An agency theory approach on Romanian listed companies’ capital structure. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 3(39), 39–50.

- Trinh, V. Q., Aljughaiman, A. A., & Cao, N. D. (2020). Fetching better deals from creditors: Board busyness, agency relationships and the bank cost of debt. International Review of Financial Analysis, 69, 101472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101472

- Usman, M., Farooq, M. U., Zhang, J., Makki, M. A. M., & Khan, M. K. (2019). Female directors and the cost of debt: Does gender diversity in the boardroom matter to lenders? Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(4), 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-04-2018-1863

- Vafeas, N. (1999). Board meeting frequency and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 53(1), 113–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(99)00018-5

- Vakilifard, H. R., Gerayli, M. S., Yanesari, A. M., & Ma’atoofi, A. R. (2011). Effect of corporate governance on capital structure: Case of the Iranian listed firms. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 35, 165–172.

- Vijayakumaran, S., & Vijayakumaran, R. (2019). Corporate governance and capital structure decisions: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 6(3), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2019.vol6.no3.67

- Vy, N. T. N. (2016). Does profitability affect debt ratio? Evidence from Vietnam listed firms. Journal of Finance & Economics Research of Borrowing, 1(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.20547/jfer1601202

- Yilmaz, I. (2018). Corporate governance and financial performance relationship: Case for Oman companies. Journal of Accounting, Finance and Auditing Studies, 4(4), 84–106.

- Zaid, M. A. A., Wang, M., Abuhijleh, S. T. F., Issa, A., Saleh, M. W. A., & Ali, F. (2020). Corporate governance practices and capital structure decisions: The moderating effect of gender diversity. Corporate Governance, 20(5), 939–964. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-11-2019-0343