Abstract

The purpose of the study was to observe how Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) struggle to develop the sustainability reports that are today important and required by consumers. The rationale is that the sustainability report is influenced by governance practices, social responsibility, and environmental impact. The research successfully summarizes the barriers from 37 influential sustainability report papers by employing a thorough systematic literature review. It was based on 6 well-known databases with the limitation of exclusion criteria such as 11 years of research (2012–2023), used English, and more than 4 pages articles. According to the findings of this literature review approach, SMEs encounter six different sorts of barriers while trying to develop a sustainable report: financial, general attitude, knowledge and technology, organizational, policies and regulations as well as socio-environmental barriers. Based on this result, the top management of SMEs will be able to determine how to prioritize removing the biggest obstacles of their reporting task.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

In Europe and the United States, sustainability reporting dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, when businesses began to understand that they had a social responsibility that goes beyond maximizing profits. The first Earth Day, which was observed on April 22, 1970, served as the impetus for the US sustainability movement and reporting. Following that, the United Nations released the Brundtland Report, also known as Our Common Future, in 1987, which gave the movement a boost in momentum (Bosi et al., Citation2022).

Since 1993, there has been an increasing tendency toward reporting on sustainability. The top 250 corporations in the world reported a 96% success rate for the year 2020 (KPMG, Citation2023). Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are no exception. SMEs are affected by this trend, especially on how to integrate sustainability reporting into their supply chain management. Due to difficulties enterprises have integrating economic, social, and environmental factors into their accounting systems, sustainability reporting is becoming more and more important (Maione, Citation2023). After the Covid-19 pandemic, digital innovations are being made and many big companies have applied blockchain technology to track the sustainability of their supply chains, while others are using artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyse sustainability data and identify areas for improvement.

ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) factors must now be mentioned in yearly reports by companies. Although ESG factors are often closely related to sustainability reporting, but they are not the same. Environmental, Social, and Governance factors refer to a broader set of non-financial performance indicators that are used to evaluate a company’s overall sustainability and responsible business practices (Waterhouse-Coopers, Citation2023). These factors can include issues like carbon emissions, labour practices, board diversity, and ethical behaviour. On the other side, sustainability reporting is the process of assessing and outlining a company’s performance in terms of its governance, social, and environmental responsibilities, often in accordance with a specific framework or standard. The majority of sustainability reporting focuses on particular measures relating to governance processes, social responsibility, and environmental impact (Oprean-Stan et al., Citation2020). Non-financial information is commonly described in terms of ESG information, which stands for the three main metrics used to assess a company’s sustainability and social effect (Deloitte, Citation2021). As a result, ESG factors can be considered alongside sustainability reporting, but they are not necessarily dependent on one another. Companies can opt to report on ESG aspects independently or choose to publish their ESG performance in a variety of ways, such as through sustainability reporting.

While sustainability reporting is important for both large corporations and SMEs, the benefits and challenges faced by corporations and SMEs are different, depending on the size and complexity of the organization. Sustainability reporting for the supply chain of SMEs adopts standardized reporting frameworks, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). These frameworks offer recommendations for writing on a range of sustainability-related topics, such as governance, social responsibility, and environmental effects. It should be recognized, nonetheless, that the motivations for sustainability and finances are distinct: finance-related considerations have an impact on SASB adoption, while the GRI is affected by corporate governance mechanisms encouraged by sustainable and ethical practices (Pizzi et al., Citation2022). The GRI and SASB conducted a joint study to examine the experiences of larger corporations that use the two sets of standards to meet their reporting requirements, particularly in the accounting and finance departments. However, following the GRI can be challenging for SMEs for several reasons, among them resource limitations, limited expertise, complexity, and time constraints (Permatasari & Kosasih, Citation2021). Despite the challenges, by following the GRI sustainability reporting guidelines, SMEs can demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and responsible business practices. SMEs can also differentiate themselves from competitors, as well as improve their transparency and credibility with stakeholders (Stolowy & Paugam, Citation2023).

The latest research related to sustainability reporting from Maione (Citation2023) explored the detailed analysis of corporate sustainability reporting tactics, emphasizing the justification for implementing the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards, the difficulties to be encountered, and the potential ramifications for accounting experts, managers, policymakers, and academics. Another research from Farisyi, et al. (Citation2022) deals with the development of sustainability reporting, implemented in developing countries. There is also research on sustainability indicators for small- and medium-sized industrial firms focusing only on Turkey (Saygili et al., Citation2023).

Our research fills a void that there is currently no specific research that attempts to comprehend the overall challenges that SMEs have encountered in creating sustainability reports.

In this research context, the existing knowledge gap refers to the complexities encountered by SMEs when they undertake sustainability reporting initiatives. While the discipline of sustainability reporting has made considerable advancements, especially within large corporate entities, the obstructions faced by SMEs have received minor scholarly attention. SMEs constitute a complex and essential part of the business landscape, and gaining a deeper understanding of the unique obstacles that SMEs face holds significant importance in promoting their active participation in sustainability reporting initiatives. The principal objective of this study is to address the knowledge gap through the systematic examination of extant scholarly works, where the aim is to consolidate the barriers that SMEs confront across diverse sectors. This study aspires to lead the way for SMEs to overcome these obstacles, thus facilitating their meaningful engagement in the subject of sustainability reporting.

In this paper, we address the issue of certain challenges SMEs are having in implementing sustainability reporting. This research is important for understanding the difficulties faced by SMEs, enabling them to tackle them one at a time. Therefore, in the future SMEs will be able to provide sustainability reporting. The motivation of the systematic literature review was to integrate those challenges in several industries such as food, agriculture, fashion, manufacturing, service sector, and others. According to Saunders and Rojon (Citation2011), a systematic literature review is crucial to a full understanding and to gaining knowledge from prior studies that have high study quality.

The sections of the study are as follows: The introduction is in Section 1, and the other four sections will be shared as follows. A literature review will be discussed in Section 2. The methodology technique is presented in Section 3. The result and discussion are shown in Section 4. The study’s conclusions will be presented in Section 5.

2. Literature review

2.1. Sustainability reporting explanation

A previous study by Hahn and Kuhnen (Citation2013), became the starting point for this paper to review sustainability reporting and recent developments. The pursuit of economic, social, and environmental goals by stakeholders, including employees, suppliers, creditors, advocacy groups, and public authorities, determines an organization’s performance (Hahn & Kuhnen, Citation2013). Sustainability reporting is important for organizations attempting to achieve the objectives stated above. By disclosing sustainability information, for instance, private companies aim to increase brand value, reputation, and legitimacy as well as transparency, enable benchmarking against competitors, signal competition, motivate employees, and support corporate information and control processes. (Herzig & Schaltegger, Citation2006). In general, the motivation for sustainability reporting in organizations focuses on three main items, such as strategic relating to stakeholders or setting oneself apart from competitors; responsive, ie a situation or change, such as a financial crisis or a shift in local interests; or following, ie being driven by competing groups’, NGOs’, or government body initiatives (Adams & Frost, Citation2008).

According to Deloitte (Citation2021), executives in business, investors, customers, and regulators are paying more attention to sustainability and other non-financial data. Many businesses are now aware of how critical it is to support social and environmental problems in their reporting. The non-financial data consists of descriptions, facts, and opinions that are difficult to explain in monetary terms or that are expressed in non-monetary terms. Non-financial data could be either retroactive or forward-looking. Recently they have increasingly played a big role in reporting from many different entities and became the forerunner for sustainability reporting (Choi & Meek, Citation2011). As disclosure of non-financial information became increasingly important, the concept of sustainability reporting was established, which combines economic, environmental, and social performance into a single report. In the strictest sense, a report can be mentioned as a sustainability report if it is public and shows the reader how the company is fulfilling the ‘corporate sustainability issues’ (Daub, Citation2007). Companies that have a goal of corporate environmental and social reporting are gaining social recognition and credibility for their efforts (Hongming et al., Citation2020). Several benefits have been revealed from the sustainability reporting based on several prior studies. A study from Petrescu, et al. (Citation2020) that focus on top Romanian companies showed that companies were able to improve client loyalty and trust in reputation. In addition, the report can support building, improving, and repairing a brand’s image, as well as implementing a reputation management system for the online environment. Prior research from Zrnic et al. (Citation2020) revealed that the majority of sustainability reporting focuses on impact (25%) and framework (19%) due to the close relationship between impact and framework in the application of sustainability reporting. In terms of framework, the study specified that the element of diversity should be included as a part of the guidelines and standards of sustainability reporting, while the impact factor is useful when dealing with risk and financial access (Zrnic et al., Citation2020).

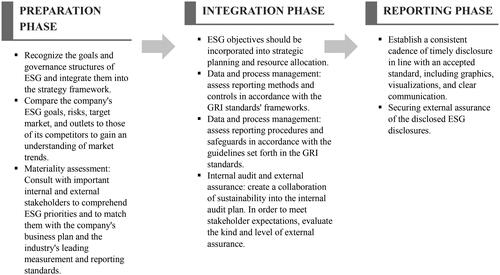

At the start of its development, the sustainability report’s content did not follow a comparable structure to that of financial reporting. A technique of reporting that was popular in the 1990s when disclosures from annual reports frequently served as explanations of reporting processes. Some studies, like those of the multinational Fortune 500, focus on the patterns of multinational companies’ sustainability reporting. Initially, there is no requirement (Zharfpeykan & Askarany, Citation2023). After the Rio + 20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, nations like France, South Africa, Brazil, and Denmark started to advocate for sustainability reporting. These nations received assistance from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in their efforts to pursue sustainable development (Hongming et al., Citation2020). A report from Deloitte (Citation2021) guides the sustainability reporting journey by providing the framework in the following steps (). reporting. These nations received assistance from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in their efforts to pursue sustainable development (Hongming et al., Citation2020). A report from Deloitte (Citation2021) guides the sustainability reporting journey by providing the framework in the following steps (). The report from Deloitte (Citation2021) explains the steps as guidance for sustainability reporting through preparation, integration, and reporting (). It begins with the understanding of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) objectives, risks, audience, and stakeholders, related to reporting standards. The internal audit plan and the integration of ESG reporting in accordance with GRI criteria follow. The reporting step is finalized by conforming the sustainability reporting with recognized standards, such as SASB to obtain external assurance.

Figure 1. Key steps for sustainability reporting. Source: Deloitte (Citation2021).

According to SASB Standards (Citationn.d.), the GRI Standards (founded in 1997) and SASB Standards (founded in 2011) are complementary standards for sustainability reporting. They are built on various conceptions of materiality and are intended to serve various functions. The SASB Standards concentrate on sustainability concerns that are most likely to have an impact on investor choice. A wide range of stakeholders are interested in the GRI Standards’ focus on a company’s economic, environmental, and social consequences concerning sustainable development. Organizations are aware that the landscape of sustainability disclosure might appear to be complex and that for businesses that adhere to both sets of criteria, the reporting effort may be substantial. In summary, the GRI sets standards for companies to report on their economic, social, and environmental impact, while the SASB focuses specifically on the financial materiality of sustainability issues (SASB Standards, n.d.). below presents the main variations between SASB and GRI.

Table 1. Main variations between the GRI and SASB.

Additionally, 98 percent of the industry-based topics addressed by SASB Standards are linked to one or more Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets and are mapped to the SDGs, per SASB Standards (n.d.). As a result, SASB Standards can offer businesses and investors a useful tool for identifying the SDG targets that are most pertinent to a particular industry. SASB Standards assist businesses and investors in allocating funds and other resources to influence the compatibility of certain SDG targets and affect financial returns. When companies and investors can have a positive influence, mitigate a negative impact, and yet meet their financial risk-and-return criteria, that is when SASB Standards and SDG objectives connect.

Each framework caters to various stakeholder demands and reporting goals, and both the GRI and the SASB have their own pros and downsides. Companies should carefully consider their target audience, materiality analyses, and industry-specific risks and opportunities before deciding on the optimal framework for their ESG reporting (ESGPRO, Citationn.d.) It is significant to highlight that the GRI and the SASB are not antagonistic to one another, and businesses decide to combine elements from both frameworks to create a comprehensive and tailored ESG reporting strategy. By understanding the key differences between the GRI and the SASB, companies may choose which framework, or combination of frameworks, best corresponds with their ESG reporting goals and stakeholder expectations (ESGPRO, Citationn.d.).

Previous research regarding sustainability reporting has been conducted on different topics and in different countries and some have created different results. The research from Engert et al. (Citation2016) emphasized that both internal factors (like company size) and external factors (like industry) can be considered relevant and influential factors. According to other research, the size and industry of the companies affected how they adopted the GRI rules, but only the industry of the companies affected how much they applied the GRI (Legendre & Coderre, Citation2013). Research from Higgins et al. (Citation2015) mentioned that it is impossible to say if the sustainability reporting techniques of early and late adopters across a range of corporate sizes and industries are logical.

2.2. Sustainability reporting in the context of small and medium enterprises (SME)

The urgency of sustainability in all facets of life has been heightened by recent global events related to climate change. However, there has not been sufficient research on how small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) incorporate sustainability ideas into their corporate governance processes. The majority of studies are carried out in the European and North American environment, while some are done in Asia (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2022). The contribution of SMEs can even be described as crucial when considering the sheer number of SMEs and their significance to the economy. Entrepreneurial businesses are well-positioned to take advantage of new opportunities created by some of the major difficulties SMEs today are facing (Smith et al., Citation2022). According to a prior study by Krawczyk (Citation2021), small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) account for 99% of all businesses in the contemporary market economy. However, the solutions to the issues and challenges they encounter are typically found instinctively, and the management sciences’ contributions are only occasionally used in the day-to-day operations of SMEs. The conversation on the growth of the SME sector has been more intense in recent years (Krawczyk, Citation2021). Additionally, significant issues including climate change, diversity and inclusion policies, openness and accountability, and meticulous record-keeping of data on SMEs’ operations should be covered in SMEs’ sustainable reporting (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2022). These problems are seldom overlooked because SMEs are not obligated to submit sustainability reporting, unlike corporations, where nowadays they must include sustainability reporting in their annual reports. SMEs are accountable for both industrial and environmental degradation, even though they do not individually put a lot of strain on the environment (Santos et al., Citation2022).

Non-financial information (NFI) disclosures have mostly been avoided by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Data were gathered from responses given by stakeholders during the European Union’s public consultation and the data has been gathered from February to June 2020. However, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive will change, regarding the value of a condensed NFI standard and/or reporting format for SMEs; whether this is a practical way to lessen the burden on SMEs; and, ultimately, whether it should be mandatory or voluntary if it is implemented (Albuquerque et al., Citation2022).

In the EU context, a study by Santos et al. (Citation2022) evaluated stakeholders’ opinions towards the usage of simplified non-financial criteria for SMEs. The findings of the study reveal that NFI is beneficial for SMEs because it makes it easier for businesses to obtain and maintain a competitive advantage (Oduro et al., Citation2021), in addition to a positive economic impact on how businesses behave on capital markets and with stakeholders besides investors (Christensen et al., Citation2021). SMEs exhibit a relatively low degree of engagement while having a considerable impact on a country’s economy, employment, and environment. However, the process of sustainability evaluation can be extremely difficult for SMEs. So, a straightforward, effective approach or process that can assess, control, and enhance SMEs’ performance is required due to the significant impacts they have on a country’s economy (Kassem & Trenz, Citation2020). A study from Santos et al. (Citation2022), which also supports the opinions of stakeholders on the potential adoption of a simplified standard of NFI for SMEs, is in line with the study from Kassem and Trenz (Citation2020), as it is not comparable for SMEs to use the same standards as corporations. Kassem and Trenz (Citation2020) outlined three measures to get a streamlined standard for SMEs: (1) selecting and putting into practice a variety of key performance indicators (KPI), (2) the suggestion of a new comprehensive sustainability assessment methodology that takes into account all selected KPIs and determines a final sustainability rating, and (3) by putting in place an information and communication system, you may streamline and automate the reporting process. However, there is a drawback to the implementation. As the previous studies are mostly based in the EU context, it may not be applicable in other countries. There are several considerations for implementing sustainability reporting, ie the diversity of users, topics, objectives, measurements, and whether sustainability reporting is voluntary or mandatory (Christensen et al., Citation2021). In fact, not all SMEs, particularly in Indonesia, are able to come up with a set of KPIs, or a system to simplify sustainability reporting, when most SMEs are still struggling with their day-to-day financial reporting. This is consistent with previous research that shows SMEs have trouble adhering to GRI recommendations because they lack the tools, expertise, and incentives necessary to implement sustainability and significantly advance SDGs (Costa et al., Citation2022; Verboven & Vanherck, Citation2016).

By integrating sustainability reporting into their operations and placing more of an emphasis on the long term, SMEs can gain from it (GRI, Citation2022). According to Tauringana’s (Citation2021) research, the GRI’s efforts to raise sustainability reporting heavily rely on training. Even though the GRI conducts its own training, the majority of the training is currently delivered by partners who are ‘certified’ to conduct their own training programs in various nations across the world. As the GRI charges to pay its training expenses, many organizations in developing nations find it difficult to finance the training. In the context of Indonesia, SMEs encounter several difficulties when implementing sustainability reporting, one of which is the absence of suitable rules or standards (Permatasari & Kosasih, Citation2021). Although the GRI seeks to improve sustainability reporting in developing nations by creating standards for sustainability reporting guidance and encouraging stock exchanges to mandate that businesses wanting to list apply the standards when drafting sustainability reports (Tauringana, Citation2021), a study from Permatasari and Kosasih (Citation2021) also mentioned that the most widely adopted business standard in the world, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Sustainability Reporting Standard, requires reporting entities to conduct numerous tests and disclose intricate data, including measuring emissions and the volume and type of waste generated during the reporting period. This is difficult to implement in Indonesia as the GRI rules are viewed as being too difficult for SMEs to execute, especially small and micro firms with limited funding and resources.

The implementation methodology of sustainability reporting in Village-Owned Enterprises (VOE) and SMEs in Indonesia is described in a paper by Kurniawan (Citation2018). The study explained a GRI standard-based sustainability reporting approach for small and medium-sized businesses and village-owned companies. The sustainability reporting approach for VOE and SMEs has five stages: (1) prepare; (2) connect; (3) define; (4) monitor; and (5) report. These five stages are similar to the three key steps of sustainability reporting from Deloitte (Citation2021). The study also shows that VOE and SMEs that implement sustainability reporting have the benefits of increased transparency toward stakeholders and improved process optimization. Moreover, the finding suggested that, from the perspective of sustainability, VOE and SMEs can make a greater contribution than other similar businesses. The results of this study’s ramifications can help more VOE and SMEs build sustainability into their economic endeavours (Kurniawan, Citation2018).

3. Methodology

Researchers used systematic literature reviews to examine the state-of-the-art and advancement of the research in particular domains, identify gaps, and suggest research objectives for future studies (Bhukya & Justin, Citation2023). The systematic literature review in summary is conducted in four phases based on Rivera et al. (Citation2022): (1) Preparation Phase, (2) Conducting Phase, (3) Reporting and Dissemination Phase and (4) Analysis Phase. The details of each will be explained in the Methodological section and the analysis phase will be explained in the analysis section.

3.1. Preparation phase

It is needed to create the panel during the preparation phase. Two researchers, in this instance, the authors of the manuscript, made up the review panel. The researchers had a large number of SMEs-related prior studies. The prior study by Tranfield et al. (Citation2003) recommended that the panel should be composed of subject-matter experts who are active in the research field. The duty to separate the literature into its respective final source falls equally on the shoulders of both researchers. Before moving on to the final source of literature, the panel held a discussion to develop the research question, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the topic of the systematic literature review (see ).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3.2. Conducting phase

The panel began the inquiry by gathering materials from a number of bibliographic databases, including ProQuest, Emerald, Springer, Taylor & Francis Online, MDPI, and Science Direct. All searches were done in the title, abstract, and keywords (see ), and we were able to identify some of the search strings in exactly the same way in each of the databases. This filtering activity resulted in approximately 14,158 publications. 5802 papers were excluded because they met the exclusive criteria, such as being a part of another dissertation, thesis, book, newspaper, magazine, working paper, report, or other exclusive criteria.

Table 3. Searching algorithm.

To make the papers the final resource, the panel must then go through the papers again. The initial step involved sorting the search string into the paper database. The publications that actually fit the context of the research are employed as the final resource in the second phase. Each paper has been double-checked by both researchers by reading the abstracts used the quality assessmement. Disagreements on the final source of articles were noted as ‘unsure’ documents, which the panel members then studied again to confirm through the paper’s content.

The 37 supplies of papers for the following phase’s reporting procedure will come from the quality assessment of 8,356 papers that were selected based on the search string filter in this phase. A standard quality assessment is a checklist with several items to consider. The criteria are evaluated and the quality assessment is quantified using a numerical scale (). 37 papers that illustrate the key problems of sustainability reporting for SMEs were found through the simultaneous categorization of the final papers throughout the analytical process that followed the procedure of systematic literature review based on the article of Rivera et al. (Citation2022). The panelists double-checked and approved this classification.

Table 4. Quality assessment checklist.

3.3. Reporting and dissemination phase

Tranfield et al. (Citation2003) mentioned in their research that a good systematic review should summarize in-depth primary research papers from which it was produced, making it simpler for the practitioner to grasp the findings. In this case, the reporting form is required to be in the descriptive analysis. On the other hand, researchers must also report the findings by thematic analysis, to make sure the result will be easy to interpret. The panel members will categorize the findings into different themes of SMEs’ sustainability reporting challenges, and they will also define each theme in more detail in descriptive analysis.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Descriptive analysis

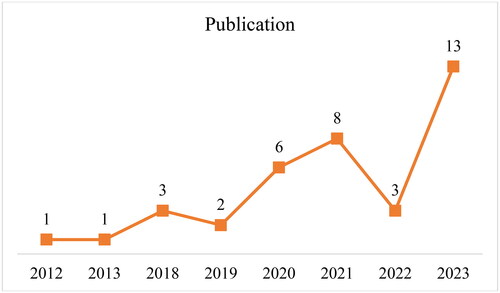

The majority of the journals used for analysis were published starting in 2012, according to the 37 papers that were chosen during the screening process. This is part of the research limitation where the research is considered as period centric research. It is driven by the desire to stay current with the latest research on sustainability reporting, and all of the findings are closely related to the actual obstacles that SMEs face nowadays. The strategy of the last ten years to concentrate on SMEs sustainability reporting is still valid and relevant due to the trend of sustainability reporting creation has been improving for larger enterprises since 1993. However, based on the results of the chosen paper review, there are very few articles that discuss the implementation barriers for SMEs’ sustainability reporting and were published in the earlier times (example: 2012 and 2013). Stay relevant is the key of the process of this research to use the previous 10 years of reference (Chigbu et al., Citation2023). Both qualitative and quantitative methods were employed in these periodicals. As shown in below, the procedure revealed that studies connected to sustainability reporting disclosure have become more popular recently.

Figure 2. Distribution of Selected Publication Based on Year of Publication. Source: Own construction based on literature review method.

As shown in , the majority of the selected papers were published in numerous International Journals and Conferences. The Sustainability International Journal has received the most research citations overall. This research’s focus on sustainability reporting makes it reasonably easy to understand.

Table 5. Distribution of Selected Publications from Journals and Conferences

4.2. Systematization of barriers

The barriers to sustainability reporting for SMEs were categorized into these 6 categories based on 37 carefully chosen papers, including financial, general attitude, knowledge and technology, organizational, policies and regulation, and socio-environmental barriers. Each category has a number of attributes, and this research ultimately distils these into 18 attributes represented from .

Table 6. Financial barriers of sustainability reporting for SMEs.

Table 7. General attitude barriers to sustainability reporting for SMEs.

Table 8. Knowledge and technology barriers to sustainability reporting for SMEs.

Table 9. Organizational barriers to sustainability reporting for SMEs.

Table 10. Policies and regulation barriers to sustainability reporting for SMEs.

Table 11. Policies and regulation barriers to sustainability reporting for SMEs.

SMEs have limited resources in terms of time and money which prevents them from implementing novel ideas like this sustainability report (Saygili et al., Citation2023). The system must be built both internally and externally, which necessitates significant funding. Even after SMEs put in place the framework to establish a system for sustainable reporting, many are unsure of how the report will assist the business. To share the advantages of a sustainable report with SMEs, the government should conduct appropriate training, role-playing exercises, and conferences (Ardra & Barua, Citation2022).

By implementing sustainability reporting, a company can increase its customer base, expand its product line, raise environmental consciousness, expand its geographic reach, acquire a competitive edge, expand its market, secure funding, and improve its reputation. However, by concentrating on the new client, it runs the risk of losing the present potential customer due to a lack of information and knowledge from their side (Shalhoob & Hussainey, Citation2023). It is related to the business’s finances and how they affect the profit.

If the company would like to create a sustainability report, then it must also have a sustainable process in place. The approach must alter, as well as, for instance, the manufacturing system, waste management, environmental protection method, and resource efficiency. It requires a lot of work on the part of the internal company. Since there have been several changes, few businesses have a strong commitment to it and therefore oppose change (Hegab et al., Citation2023). Change and innovation are closely tied to one another since businesses must innovate or think creatively to make improvements for the future. According to the sustainable innovation paradigm, businesses should use sustainable innovation to increase their competitiveness in the market (Kwak et al., Citation2023). As a result, a company that lacks innovation in the area of sustainability has a chance to not provide a sustainability report.

Although one of the advantages of sustainability reporting is to involve stakeholders in strategic management (Brusca et al., Citation2018), one issue that needs to be addressed is infrastructure problems (Mousa & Ozili, Citation2022). It needs to determine measures and techniques that would help quantify how sustainable or not present activities are to build its infrastructure (Siew et al., Citation2013). It is difficult for SMEs to execute because of the accumulation of other barriers such as a lack of resources, expensive costs, and limited time.

Each stakeholder requires a sustainability report because they count on the organization to act responsibly, accountably, and transparently. An organization has a challenge due to the different stakeholder characteristics. Each stakeholder has its unique informational requirements from the sustainability report (Băndoi et al., Citation2021). Based on the previous research by Saygili et al. (Citation2023), it was found that significantly different capital, resources, and experience owned by large companies and SMEs in terms of sustainability practices. Due to their lack of expertise, SMEs often cannot survive in the updated global market, which includes this sustainable report (Xin et al., Citation2023). In addition, due to the availability of data, the high number of KPIs in the sustainable report increases further challenges for SMEs to keep up with the update (Dissanayake, Citation2021).

Sustainability reporting is typically the only channel via which a business can convey both its sustainability strategy and its actual performance. If there are some internal problems with the organization, it appears that it won’t happen. Financial shortage is divided into two, first is a lack of resources. Since SMEs only need 250 employees at most to manage their businesses, one of their biggest problems is a shortage of resources (Arena & Azzone, Citation2012). The second one lacks time. The implementation of the sustainability measurement for these SMEs necessitates a significant time commitment that would jeopardize routine business operations. The time and resources that SMEs must set aside to develop sustainable reports, in particular, have a significant impact that influences their day-to-day business operations (Sohns et al., Citation2023).

It is possible to capitalize on the challenges that organizations have in implementing sustainable reporting. All stakeholders inside the company are required to support it, but the board of directors, which sits at the top of management, has the most influence. The general sustainable reporting process was significantly stabilized by the institutionalization and routinization of sustainability practices, employee participation, managerial commitment, organizational learning, and dissemination (De Micco et al., Citation2021).

Corporate sustainability translates environmental and social concerns into a company’s strategy, activities, and business operations. It also integrates general sustainability principles into a company context (Manninen & Huiskonen, Citation2022). In this case without having a sustainable business strategy, it is quite lame to go forward on the implementation of the sustainability reporting (Kumar et al., Citation2023). It also has to do with the innovation culture of a particular organization, where it is well known that robust and suitable organizational or companýs sustainability strategies are necessary for SMEs to achieve exceptional innovation outputs in their performance (Srisathan et al., Citation2020).

SMEs are heavily invested in reaching sustainable development goals because they play a critical role in doing so, if implemented well, they can benefit from the outcomes. One of the results that SMEs require is to develop a sustainability report. Large enterprises already utilize a specific tool to create this sustainable report. Various methodologies for assessing corporate sustainability have been changed to some extent by linking company operations to how they contribute to the realization of sustainability development goals. But, especially for SMEs, these tools are frequently complicated and challenging to apply (Jiménez et al., Citation2021).

On the other hand, implementing sustainable development in any organization is especially important when relevant governmental laws and regulations are also in place. The government regulation and policies consist of a legal framework, enforcement of the law, and a controlling and monitoring system (Abdullah et al., Citation2023). If there are no clear and standardized policies, it makes it difficult for SMEs to manage their sustainable report. Government policies are tied to policies in each country or region (Gherardi et al., Citation2021).

A good level of stakeholder participation is required to produce the sustainability report. The organization’s managers must acquire data and information from the existing stakeholder engagement platforms (such as employee surveys, client surveys, forums for debate and feedback on the company website, and social media platforms) although these channels were initially intended to provide feedback on an organization’s commercial performance, to identify and evaluate the primary material issues. Managers seemed dissatisfied with the scant stakeholder survey response rate and thought that the public was uninterested in their findings (Farooq & De Villiers, Citation2019).

According to Rossi and Vilchez’s (2020) study mentioned that how much an organization shapes management decision-making to implement a sustainable integrated process will depend on a variety of organizational dynamics. The three stages for the integration of social and economic reporting that are built into sustainable reports are: creating a shared understanding system around the concept of social and environmental responsibility; making it practical through the emergence of rules and routines; and reinforcing it through the implementation of intra-organizational managerial procedures and structures.

5. Conclusion

SMEs are crucial to the accomplishment of sustainable development objectives and with proper implementation, they can gain from sustainability reporting. The theoretical contribution of this article is to provide a framework for the challenges of sustainability implementation for SMEs. The majority of papers released after 2012 attest that sustainability reporting is a key driver for SMEs to contribute to sustainable development goals. When executed effectively, SMEs can obtain substantial benefits from elevating environmental consciousness to expanding their reputation and customer base.

We summarized the challenges of the sustainability journey for SMEs: struggle with financial constraints, general attitude, knowledge gaps, technological hurdles, organizational complexities, socio-environmental and regulatory frameworks that may seem daunting. Moreover, measuring sustainability metrics can be intricate for SMEs. Yet, the true power of sustainability reporting lies in its ability to engage stakeholders in strategic decision-making. This engagement is pivotal for SMEs to build meaningful sustainability reports, even as they wrestle with resource limitations, costs, and time constraints.

The above results may lead to practical implications, such as to find the most effective actions to promote the sustainability report implementation. The solution can be applied by policymakers or executives of SMEs, putting the company first, in addition to addressing some of the primary obstacles it faces, such as those related to knowledge, technology, or other areas. SMEs must become more driven to contribute to sustainable development and to protect the environment. Motivation and comapanýs reward will help this development in accordance to the previous study from Manninen and Huiskonen, Citation2022.

Another vision of the future, related to the policymakers´ role or the role of government takes center stage. Policymakers and government intervention through clear and standardized policies become indispensable for SMEs to effectively manage their sustainability reporting. Such support is not just for formality reasons, but it is a catalyst for SMEs to adopt sustainability reporting in a manner that aligns with global expectations. Concurrently, stakeholder involvement remains vital, as it ensures that SMEs are held responsible, accountable, and transparent in their sustainability efforts.

As a result, the future of SMEs is intrinsically linked with sustainability reporting, with both stakeholders and governments playing pivotal roles. By effectively integrating transparency and responsibility into their practices, SMEs can navigate the evolving economic landscape and emerge as trailblazers in sustainable business practices, ultimately yielding positive outcomes for themselves and the society.

Based on this article, several avenues for future research can be identified. For example, the next study may employ different techniques for gathering data, such as a qualitative approach using appropriate interview questions, a case study, or a quantitative approach using a structured questionnaire. Finding more barriers or challenges from SMEs regarding their implementation of sustainability reporting may be helpful. Another future research option is that rather than concentrating on obstacles, concentrate on the factors that facilitate sustainability reporting. From the viewpoint of an organization’s top management, there are various examples that can be shared that demonstrate moral leadership and help the organization implement sustainability reporting. Another goal would be to conduct training in ethical leadership at the top management levels. This could positively impact SMEs by facilitating the completion of sustainability reports and also enhancing the ethical standards of the organization. This proposal aligns with the findings of Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2011) research, which indicates that average employee behavior is influenced by top management’s ethical leadership even though it is in indirect ways. In addition, it is vital to raise the morale of all parties in the company not only the employees, supervisors but also the top management, which makes it easier for SMEs to become more conscious of sustainability issues and participate in global initiatives that support the development of sustainability reporting. This input is also in accordace to the research of Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2011). Another recommendation for future research is to focus on a specific industry, such as SMEs that specialize in automation, food and beverages, or other fields. In this instance, the distinction between general and specific barriers or challenges regarding the implementation of sustainability reporting can be added.

Authors contributions

RS came up with the concept and supported it with the production of the original document, the introduction, a thorough literature review, references, and the conclusion. SS developed the approach, collected the data, conducted the analysis, and edited the manuscript submission. PK was also supported in the manuscript revision. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Upon a reasonable request, the information and materials that support the conclusions of this article will be given.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Santi Setyaningsih

Santi Setyaningsih is a PhD graduate from Széchenyi István University, Győr, Hungary. She received her master’s from the Institute of Technology of Bandung, Indonesia. Her research interest is in the area of Supply Chain Management (SCM) and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). Apart from that she also has several publications related to service management and entrepreneurship. Currently, she is not only a part-time researcher at Széchenyi István University, Győr, Hungary but also a part-time lecturer at Sekolah Tinggi Teknologi Cipasung, Tasikmalaya, Indonesia.

Rosita Widjojo

Rosita Widjojo is a PhD graduate from István Széchenyi Management and Organization Sciences Doctoral School, University of Sopron, Hungary. Her research interest is in sustainability, focusing on circular economy, green finance, and risk management. She is currently employed at the Indonesian International Institute of Life Sciences as a faculty member of the Master in Biomanagement Program, in Jakarta, Indonesia, and now undergoing a joint research program with ASEAN and Hiroshima University in Japan.

Peter Kelle

Peter Kelle is the Ourso Family Distinguished Professor of Decision Analysis at the E.J. Ourso College of Business, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, USA. He was the American Editor of the International Journal of Production Economics between 2000 and 2022. His recent research interests include disaster supply chain management, inventory control in healthcare systems, and sustainable supply chains. He has been working on several research grants, lately with the US Dept. of Homeland Security in disaster supply chain management area and with the US Dept. of Transportation on safety improvement and optimization.

References

- Abdullah, A., Saraswat, S., & Talib, F. (2023). Barriers and strategies for sustainable manufacturing implementation in SMEs: A hybrid fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS framework. Sustainable Manufacturing and Service Economics, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smse.2023.100012

- Adams, C. A., & Frost, G. R. (2008). Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. Accounting Forum, 32(4), 288–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2008.05.002

- Akomea-Frimpong, I., Asogwa, I. E., & Tenakwah, E. J. (2022). Systematic review of sustainable corporate governance of SMEs: Conceptualisation and propositions. Corporate Ownership and Control, 19(3), 74–91. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv19i3art5

- Albuquerque, F., Barreiro-Rodrigues, M. A., Gomes dos Santos, P., & Morais, A. I. (2022). The reporting of non-financial information by SMEs: Assessing the answers to the project of the revised directive 2014/95/EU. In Modern regulations and practices for social and environmental accounting (pp. 2090–2109). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-9410-0.ch00510.4018/978-1-7998-9410-0.CH005

- Anyigbah, E., Kong, Y., Edziah, B. K., Ahoto, A. T., & Ahiaku, W. S. (2023). Board characteristics and corporate sustainability reporting: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sustainability, 15(4), 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043553

- Ardra, S., & Barua, M. K. (2022). Halving food waste generation by 2030: The challenges and strategies of monitoring UN sustainable development goal target 12.3. Journal of Cleaner Production, 380, 135042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135042

- Arena, M., & Azzone, G. (2012). A process-based operational framework for sustainability reporting in SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(4), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211277460

- Băndoi, A., Bocean, C. G., Del Baldo, M., Mandache, L., Mănescu, L. G., & Sitnikov, C. S. (2021). Including sustainable reporting practices in corporate management reports: Assessing the impact of transparency on economic performance. Sustainability, 13(2), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020940

- Bhukya, R., & Justin, P. (2023). Social influence research in consumer behavior: What we learned and what we need to learn? – A hybrid systematic literature review. Journal of Business Research, 162, 113870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113870

- Boix-Fayos, C., & De Vente, J. (2023). Challenges and potential pathways towards sustainable agriculture within the European Green Deal. Agricultural Systems, 207, 103634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103634

- Bosi, M. K., Lajuni, N., Wellfren, A. C., & Lim, T. S. (2022). Sustainability reporting through environmental, social, and governance: A bibliometric review. Sustainability, 14(19), 12071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912071

- Bouraima, M. B., Alimo, P. K., Agyeman, S., Sumo, P. D., Lartey-Young, G., Ehebrecht, D., & Qiu, Y. (2023). Africa’s railway renaissance and sustainability: Current knowledge, challenges, and prospects. Journal of Transport Geography, 106, 103487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103487

- Bruce, E., Keelson, S., Amoah, J., & Egala, S.B. (2023). Social media integration: An opportunity for SMEs sustainability. Cogent Business & Management, 10, 2173859. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2173859

- Brusca, I., Labrador, M., & Larran, M. (2018). The challenge of sustainability and integrated reporting at universities: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 188, 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.292

- Chigbu, U.E., Atiku, S.O. & Plessis, C.C.D. (2023). The science of literature reviews: Searching, identifying, selecting, and syntesising. Publication, 11(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101895

- Choi, F. D. S., & Meek, G. K. (2011). International accounting (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Christensen, H. B., Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2021). Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Review of Accounting Studies, 26(3), 1176–1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09609-5

- Costa, R., Menichini, T., & Salierno, G. (2022). Do SDGs really matter for business? Using GRI sustainability reporting to answer the question. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2022.v11n1p113

- Daub, C.-H. (2007). Assessing the quality of sustainability reporting: An alternative methodological approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.08.013

- De Micco, P., Rinaldi, L., Vitale, G., Cupertino, S., & Maraghini, M. P. (2021). The challenges of sustainability reporting and their management: The case of Estra. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(3), 430–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2019-0555

- Deloitte. (2021). Reporting of non-financial information (p. 4). Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/be/Documents/audit/DT-BE-reporting-of-non-financial-info.pdf.

- Dissanayake, D. (2021). Sustainability key performance indicators and the global reporting initiative: Usage and challenges in a developing country context. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(3), 543–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-08-2019-0543

- Engert, S., Rauter, R. & Baumgartner, R.J. (2016). Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 2833–2850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.031

- ESGPRO. (n.d.). ESG reporting frameworks: Comparing the GRI and the SASB. ESGPRO. https://esgpro.co.uk/esg-reporting-frameworks-comparing-the-gri-and-the-sasb/.

- Farisyi, S., Musadieq, M.A., Utami, H.N., & Damayanti, C.R. (2022). A systematic literature review: Determinants of sustainability reporting in developing countries. Sustainability, 14, 10222. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610222

- Farooq, M. B., & De Villiers, C. (2019). Understanding how managers institutionalise sustainability reporting: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(5), 1240–1269. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2017-2958

- Gherardi, L., Linsalata, A. M., Gagliardo, E. D., & Orelli, R. L. (2021). Accountability and reporting for sustainability and public value: Challenges in the public sector. Sustainability, 13(3), 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031097

- GRI. (2022). Global reporting initiatives. Global Reporting. Retrieved July 4, 2023, from https://www.globalreporting.org/.

- Gutiérrez, P.B., Baena, M.D.G., Vílchez, M.L., & Polo, F.C. (2021). An approach to using the best-worst method for supporting sustainability reporting decision-making in SMEs. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64(14), 2618–2640. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2021.1876003

- Hahn, R., & Kuhnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.005

- Hegab, H., Shaban, I., Jamil, M., & Khanna, N. (2023). Toward sustainable future: Strategies, indicators, and challenges for implementing sustainable production systems. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 36, e00617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00617

- Herzig, C., & Schaltegger, S. (2006). Corporate sustainability reporting. An overview. In S. Schaltegger, M. Bennett, & R. Burritt (Eds.), Sustainability accounting and reporting (pp. 301–324). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4974-3_13

- Higgins, C., Milne, M.J. & Gramberg, B.V. (2015). The uptake of sustainability reporting in Australia. Journal of Business Ethics, 129, 445–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2171-2

- Hongming, X., Ahmed, B., Hussain, A., Rehman, A., Ullah, I., & Khan, F. U. (2020). Sustainability reporting and firm performance: The demonstration of Pakistani firms. SAGE Open, 10(3), 215824402095318. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020953180

- Jiménez, E., de la Cuesta-González, M., & Boronat-Navarro, M. (2021). How small and medium-sized enterprises can uptake the sustainable development goals through a cluster management organization: A case study. Sustainability, 13(11), 5939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115939

- Kassem, E., & Trenz, O. (2020). Automated sustainability assessment system for small and medium enterprises reporting. Sustainability, 12(14), 5687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145687

- Kaur, A., & Lodhia, S. K. (2019). Key issues and challenges in stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: A study of Australian local councils. Pacific Accounting Review, 31(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-11-2017-0092

- KPMG. (2023). Key global trends in sustainability reporting. Retrieved April 21, 2023, from https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2022/09/survey-of-sustainability-reporting-2022.html.

- Krawczyk, P. (2021). Non-financial reporting—Standardization options for SME sector. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(9), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14090417

- Kumar, S., et al. (2023). Barriers to adoption of industry 4.0 and sustainability: A case study with SMEs. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 36(5), 657–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951192X.2022.2128217

- Kurniawan, P. S. (2018). An implementation model of sustainability reporting in village-owned enterprise and small and medium enterprises. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management, 2(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.28992/ijsam.v2i2.49

- Kwak, K., Kim, D., & Heo, C. (2023). Sustainable innovation in a low- and medium-tech sector: Evidence from an SME in the footwear industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 397, 136399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136399

- Lai, A., & Stacchezzini, R. (2021). Organisational and professional challenges amid the evolution of sustainability reporting: A theoretical framework and an agenda for future research. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(3), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2021-1199

- Legendre, S., & Coderre, F. (2013). Determinants of GRI G3 application levels: The case of the fortune global 500: Determinants of GRI G3 application levels. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 20(3), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1285

- Maione, G. (2023). An energy companýs journey toward standadized sustainability reporting: Addressing governance challenges. Transforming Government People, Process and Policy, 17(4), 1750–6166. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-05-2023-0062

- Manninen, K. & Huiskonen, J. (2022). Factors influencing the implementation of an integrated corporate sustainability and business strategy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 343, 131036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131036

- Martínez, E.O., & Hernández, S.M. (2021). European SMEs and non-financial information on sustainability. Intenational Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 29(2), 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2021.1929548

- Mousa, R., & Ozili, P. K. (2022). A futuristic view of using XBRL technology in non-financial sustainability reporting: The case of the FDIC. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16010001

- Oduro, S., Bruno, L., & Maccario, G. (2021). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in SMEs: What we know, what we don’t know, and what we should know. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2021.1951064

- Oprean-Stan, C., Oncioiu, I., Iuga, I. C., & Stan, S. (2020). Impact of sustainability reporting and inadequate management of ESG factors on corporate performance and sustainable growth. Sustainability, 12(20), 8536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208536

- Ortiz-Martínez, E., & Marín-Hernández, S. (2020). European financial services SMEs: Language in their sustainability reporting. Sustainability, 12(20), 8377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208377

- Petrescu, A.G., Bîlcan, F.R., Petrescu, M., Oncioiu, I.H., Türkes, M.C., & Căpusneanu, S. (2020). Assessing the benefits of the sustainability reporting practices in the top romanian companies, Sustainability, 12(3470), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083470

- Permatasari, P., & Kosasih, E. (2021). Sustainability reporting guideline for small medium enterprises (SMEs): Case study from 25 SMEs in Indonesia. RSF Conference Series: Business, Management and Social Sciences, 1(2), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.31098/bmss.v1i2.256

- Pizzi, S., Principale, S., & de Nuccio, E. (2022). Material sustainability information and reporting standards. Exploring the differences between GRI and SASB. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(6), 1654–1674. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-11-2021-1486

- Pommier, B., & Engel, A. M. (2021). Sustainability reporting in the hospitality industry. Research in Hospitality Management, 11(3), 173–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2021.2006937

- Rivera, A.C., et al. (2022). How to conduct a systematic literature review: A quick guide for computer science research. MethodsX, 9, 101895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101895

- Rossi, A., & Luque-Vílchez, M. (2021). The implementation of sustainability reporting in a small and medium enterprise and the emergence of integrated thinking. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(4), 966–984. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2020-0706

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Bañón Gomis, AJ., & Ruiz Amaya, C. (2011). Morals in business organizations: An approach based on strategic value and strength for business management. Cuadernos de Gestión. 11, 15–31. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.100221pr

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Ruiz, C., & Martínez, R. (2011). The cascading effect of top management´s ethical leadership: Supervisors or other lower-hierarchical level individuals? African Journal of Business Management, 5(12), 4755–4764, https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM10.718

- Santos, P. G. D., Albuquerque, F., Rodrigues, M. A. B., & Morais, A. I. (2022). The views of stakeholders on mandatory or voluntary use of a simplified standard on non-financial information for SMEs in the European Union. Sustainability, 14(5), 2816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052816

- SASB Standards. (n.d.). How do GRI and SASB Standards work together? Do companies report on both sets of standards? Retrieved July 4, 2023 from https://help.sasb.org/hc/en-us/articles/360052463951-How-do-GRI-and-SASB-Standards-work-together-Do-companies-report-on-both-sets-of-standards.

- Saunders, M.N.K. & Rojon, C. (2011). On the attributes of a critical literature review. An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 4(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2011.596485

- Saygili, E., Uye Akcan, E., & Ozturkoglu, Y. (2023). An exploratory analysis of sustainability indicators in Turkish small- and medium-sized industrial enterprises. Sustainability, 15(3), 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032063

- Shalhoob, H., & Hussainey, K. (2023). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure and the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sustainability performance. Sustainability, 15(1), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010200

- Siew, R. Y. J., Balatbat, M. C. A., & Carmichael, D. G. (2013). A review of building/infrastructure sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 2(2), 106–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-03-2013-0010

- Singh, M. P., Chakraborty, A., Roy, M., & Tripathi, A. (2021). Developing SME sustainability disclosure index for Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) listed manufacturing SMEs in India. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(1), 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-019-00586-z

- Smith, J. A., Reid, G. C., & Cardao-Pito, T. (2022). Call for papers: Accounting and accountability in small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). European Journal of Management Studies, 27(3), 341–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMS-11-2022-112

- Sohns, T. M., Aysolmaz, B., Figge, L., & Joshi, A. (2023). Green business process management for business sustainability: A case study of manufacturing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from Germany. Journal of Cleaner Production, 401, 136667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136667

- Srisathan, W.A., Ketkaew, C., & Naruetharadho, P. (2020). The intervention of organizational sustainability in the effect of organizational culture on open innovation performance: A case of Thai and Chinese SMEs. Cogent Business & Management, 7: 1717408. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1717408

- Steinhöfel, E., Galeitzke, M., Kohl, H., & Orth, R. (2019). Sustainability reporting in German manufacturing SMEs. Procedia Manufacturing, 33, 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2019.04.076

- Stolowy, H., & Paugam, L. (2023). Sustainability reporting: Is convergence possible? Accounting in Europe, 20(2), 139–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2023.2189016

- Tauringana, V. (2021). Sustainability reporting challenges in developing countries: Towards management perceptions research evidence-based practices. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 11(2), 194–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-01-2020-0007

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14, 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

- Tiwari, K., Shadab Khan, Mohd., & Bharti, P. K. (2018). Sustainability accounting and reporting for supply chains in india-state-of-the-art and research challenges. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 404, 012022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/404/1/012022

- Verboven, H., & Vanherck, L. (2016). Sustainability management of SMEs and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum, 24(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00550-016-0407-6

- Waterhouse-Coopers, P. (2023). ESG in Indonesia: Access to Finance 2023 (p. 29). Oxford Business Group. https://www.pwc.com/id/en/esg/esg-in-indonesia-2023.pdf.

- Xin, Y., Khan, R. U., Dagar, V., & Qian, F. (2023). Do international resources configure SMEs’ sustainable performance in the digital era? Evidence from Pakistan. Resources Policy, 80, 103169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.103169

- Yadegaridehkordi, E., Foroughi, B., Iranmanesh, M., Nilashi, M., & Ghobakhloo, M. (2023). Determinants of environmental, financial, and social sustainable performance of manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 35, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2022.10.026

- Zharfpeykan, R., & Askarany, D. (2023). Sustainability reporting and organisational factors. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(3), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16030163

- Zimon, G., Arianpoor, A., & Salehi, M. (2022). Sustainability reporting and corporate reputation: The moderating effect of CEO opportunistic behavior. Sustainability, 14(3), 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031257

- Zrnic, A., Dubravka, P. S., & Crnkovic, B. (2020). Recent trends in sustainability reporting: Literature review and implications for future research. Ekonomski Vjesnik/Econviews, XXXIII(1/2020), 271–283.