?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

A pandemic causes several disruptions and difficulties in work processes and the lives of workers. Given that the agricultural -sector remains an integral sector to human existence and livelihood, it was important to examine ways of ensuring that employees in the agricultural sector remain satisfied and committed during the novel COVID-19 pandemic. Underpinned by the Social Exchange Theory, this study sought to empirically examine the extent to which instrumental and emotional co-worker support affect employee affective commitment via job satisfaction. Primary data was obtained from 250 employees of 8 agro-processing companies in Ghana. Structured self-administered questionnaires were utilised and SPSS v26 and AMOS v26 were used for the data analysis. The results showed that instrumental and emotional co-worker support were positively and significantly related to employee affective commitment. Job Satisfaction also mediated the relationships between instrumental and emotional co-worker support and affective commitment Drifting from previous studies which largely focused on employees’ affective commitment in service-based organizations, this study provides insights from the manufacturing sector. Additionally, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly disrupted on-site job structures and interpersonal interactions, this study addresses how co-worker support in such circumstances affect employee job satisfaction and affective commitment.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Countries, institutions, businesses, and individuals have been faced with several global crises. For example, the 1997 and 2008 economic crises, the economic downturn, and others are linked with both political and climatic concerns. Regardless, these crises have collectively had negative economic and environmental impacts on livelihoods, institutions, and countries at large. The COVID-19 pandemic adversely impacted organizations of varied types, especially, manufacturing firms. Post-covid, the need to engender committed employees is pertinent to limit the costs borne by firms due to the pandemic. Thus, firms are to ensure and maintain committed employees (Shahid & Azhar, Citation2013).

Considering that recent times are characterised by increased crises like the recent COVID-19 pandemic, employees’ commitment remains vital to firms’ survival and success. Uncommitted employees tend to bring several costs and burden to their employing institutions (Gasengayire & Ngatuni, Citation2019; Taderera & Al Balushi, Citation2018). Employee commitment is generally defined as ‘an employee’s sense of loyalty to and identification with the company and its goals, and involvement in the company’ (Aguiar-Quintana et al., Citation2020). Usually cited as a key dimension of commitment (DiPietro et al., Citation2020; Martini et al., Citation2018), Affective Commitment is described as an employee’s emotional attachment to his or her company (Ampofo, Citation2020; Sobaih et al., Citation2020).

An employees’ commitment level is highly likely to be based on the support they receive from their institutions. Support has been generally theorised to emanate from several quarters, which include, but is not limited to; the institutions, stakeholders, leaders or supervisors and co-workers (Freudenreich et al., Citation2020; Pinna et al., Citation2020; Zheng et al., Citation2018). In this study, emphasis is placed on co-worker support. In accordance with established research, co-worker support is operationally defined as the perceptions held by employees regarding the degree to which their fellow colleagues offer both emotional and instrumental aid within the organizational context, as articulated by Ng and Sorensen (Citation2008).

Existing studies on the relationship between co-worker support and employee commitment have largely shown a direct and significant relationship (Ahmad et al., Citation2019; Torka & Schyns, Citation2010). However, research on co-worker support–affective commitment nexus remains inclusive because other factors that can facilitate the relationship have insufficiently been accounted for in the literature. One factor that has received limited attention is employee job satisfaction. This study therefore presents a novel attempt to examine the mediating role of job satisfaction on the relationship between co-worker support and affective commitment. In this regard, this study proposes job satisfaction as a significant mechanism which carries the positive effects from the two main dimensions of co-worker support (instrumental and emotional) resulting in affective commitment.

Employees’ satisfaction with their jobs is a major concern both in theory and practice since it has several effects on organizational performance. Job satisfaction is generally regarded as the behaviours and feelings of employees resulting from their assessment of the jobs (Fritzsche & Parrish, Citation2005) they do and the extent to which they like their jobs (Spector, Citation2021). Shim et al. (Citation2002) defined job satisfaction as the degree to which an employee is satisfied with his/her job. Job satisfaction among the employees will vary based on the affective and cognition perception towards the job (Thompson & Phua, Citation2012). Over the past few decades, the focus of researchers on factors that influence employees from all fronts have increased. Hitherto, attention was primarily on factors that affect organizational performance or productivity (Chandrasekar, Citation2011; Habtoor, Citation2016; Mafini & Pooe, Citation2013). With the passage of time and the altering dynamics in organizations, it appears that businesses and researchers have become more concerned with both work and non-work factors that affect employees. Besides, in both the long and short run, employees make up the organization (Lyons & Marler, Citation2011), hence focus on this regard is necessary. As a result, the issues of work-life balance, subjective well-being, and flexible work arrangements among others have become the mainstay of contemporary research (Vignoli et al., Citation2020; Jackson & Fransman, Citation2018). The well-being of employees has become a major concern in this post COVID-19 times (Asamoah Antwi et al., Citation2023). According to the UN SDG, transforming the world in so many ways is a concern. Their main goal is ensuring that employees/individuals have sound mental health and well-being even in this post COVID-19 pandemic season. It is advanced that the emotions, attitudes, feelings, and behaviours (stemming from work and non-work life) has substantial effects on employees’ satisfaction and their performance (Kowalski & Loretto, Citation2017), which also goes a long way to affect organizations.

Our paper clouts on the Social Exchange Theory to provide a valuable explanation for the proposed relationships. Social Exchange Theory suggests an exchange relationship between an employee and the employer, where both parties have obligations to fulfill to each other (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). The current study conceptualises affective commitment as an exchange relationship, since employees would likely build strong bonds with companies through the supportive relationship established amongst co-workers (Ampofo, Citation2020). When employees feel unfairly treated in the company or do not earn the needed support from their co-workers, they are likely to display displeasure and therefore emotionally detach themselves from the company (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006).

This paper makes two relevant contributions. Firstly, even though the Social Exchange Theory has been widely used in the affective commitment literature, we extend the applicability of the Social Exchange Theory by utilising the theory to explicate how, affectively committed employees might behave in in the peak of crises (like the COVID-19 pandemic) given that employees are satisfied with their job and the support provided by their co-workers. How people perceive the extent of job satisfaction potentially influences their behaviour in the workplace. Secondly, the study contributes to the co-worker support-affective commitment literature by examining the mediating effect of job satisfaction. Our study is an initial attempt to explain how job satisfaction might influence the co-worker support dimensions and affective commitment nexus. Earlier investigations have also shown that co-worker support is related to affective commitment (Ahmad et al., Citation2019; Torka & Schyns, Citation2010; Valaei & Rezaei, Citation2016). However, very limited attempts have been made to explain the process through which co-worker support influences affective commitment. Consequently, our study seeks to address the overarching question; how do specific components of co-worker support (instrumental and emotional) influence affective commitment through job satisfaction?

Theoretical foundation

Social exchange theory

This theory enjoys extensive applicability and utilisation across a diverse array of academic disciplines (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). In the realm of social exchange theory, originally formulated by its progenitor Blau (Citation1964), it is defined as the intentional actions undertaken by individuals, motivated by the anticipated reciprocations they expect to receive and typically indeed receive from others (p. 91).

The theory has been conceptualised in many ways, however, they all converge on the virtue of reciprocity (Akgunduz & Eryilmaz, Citation2018; Tang et al., Citation2014). It is explained by Akgunduz and Eryilmaz (Citation2018) that, the social exchange theory assumes that favors create future responsibilities rather than clearly defined ones, and that the nature of the reciprocated action cannot be bargained but left to the decision of the one who grants it.

The social exchange process commences, when an employee is treated in a favorable (positive) or unfavorable (negative) manner by another individual in an organization, such as a superior or co-worker (Eisenberger et al., Citation2004). These initial attitudes or behaviors have been referred to as initiating actions by Cropanzano et al. (Citation2017). Behaviors such as being supportive to other employees and treating them with respect and fairness (Riggle et al., Citation2009; Cropanzano & Rupp, Citation2008) can constitute positive initiating behaviors while bullying, workplace incivility and abusive leadership can be regarded as negative initiating behaviors (Tepper et al., Citation2009; Lewis, Citation2004). Although it may occur that these initiating behaviors are not responded to or reciprocated in the same fashion (Gouldner, Citation1960), these behaviors are usually reacted to, which Cropanzano et al. (Citation2017) term as ‘reciprocating responses’.

Several perspectives have been provided in regard to the application of the social exchange theory in the work setting. According to Akgunduz and Eryilmaz (Citation2018), employees may demonstrate positive behaviors within the organization if they are convinced that they are supported by their co-workers or superiors. Gao-Urhahn et al. (Citation2016) perceive that per the social exchange theory, as a worker’s affective commitment improves, they will be more likely to see organizational actions favorably, thereby satisfying their inducement/contribution ratio, which will subsequently impact their affective commitment in a positive feedback loop. According to the social exchange theory, when individuals show support to their colleagues at work, co-workers are likely to repay the positive behaviors shown towards them (Gouldner, Citation1960). A case in point is that workers who have developed high-quality associations with other colleagues may be inclined to imbibe high levels of perceived job performance, well-being, and social support (Gooty & Yammarino, Citation2016; Eisenberger et al., Citation2014). Applying this theory in the co-worker support domain, employees who perceive that they are receiving instrumental and emotional support from their fellow employees and the organization are likely to reciprocate these gestures by being affectively committed to the ideals of the organization and the duties they are expected to perform.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Co-worker support

Co-worker Support is generally defined as employees’ willingness and expression of same to help one another such as being empathetic, caring, friendly, appreciative, respectful, supportive and to work together and carry out work-related tasks (Attiq et al., Citation2017; Arora & Kamalanabhan, Citation2013; Beehr & McGrath, Citation1992). Co-worker support is viewed as a valuable resource that develops employees’ psychological strength, competence level, facilitates frequent social interactions with colleagues and shapes their positive attitude to work (Rastogi, Citation2019). In a co-worker supportive workplace environment, workers help each other, leading to the feeling of loyalty and belongingness that fosters affective commitment (Limpanitgul et al., Citation2017). Co-workers create a workplace environment and affect employee attitudes at work and their well-being (De Clercq et al., Citation2020). The phenomenon has been conceptualised to include two main dimensions - instrumental and emotional co-worker supports as defined by Ng and Sorensen (Citation2008), co-worker support will be looked at in an emotional and instrumental co-worker Support lens (Shin et al., Citation2020; Mathieu et al., Citation2019; Xu et al., Citation2017).

Instrumental co-worker support

Largely described as a task-centered form of support, instrumental co-worker support is primarily defined as the provision of tangible support, such as providing guidance, physical materials and resources, or knowledge needed to perform certain tasks (Shin et al., Citation2020; Chou & Robert, Citation2008). Malecki and Demaray (Citation2003) add that instrumental support encompasses activities such as spending time with an individual or providing people with money or other tangible materials as means of helping. Instrumental support is further divided into three sub-dimensions; work-related tangible support, work-related informative support, and non-work-related support (Chadwick & Collins, Citation2015; Scott et al., Citation2014).

Work-related tangible support is described as a coworker or supervisor’s actual action in assisting other employees in conducting their work-related activities (Chadwick & Collins, Citation2015). Work-related informative support is described as the provision of knowledge that can be used to solve work-related problems (Wongboonsin et al., Citation2018). Non-job-related support refers to a coworker’s or supervisor’s assistance in assisting other workers in matters that are not related directly to work, such as assisting in childcare activities (Wongboonsin et al., Citation2018).

Emotional co-worker support

Distinct from instrumental support, emotional co-worker support encompasses feelings of acceptance and acknowledgement and is displayed through showing love, care, trust, and empathy towards other workers (Mensah et al., Citation2020). Extant literature has adduced some empirical support for the importance of emotional support in organisations. For example, it has been found that emotional co-worker support helps to promote unity among workers (Scheibe, Citation2019; Doerwald et al., Citation2016) and reduce emotional stress emanating from both work and non-work pressure (Maner et al., Citation2002).

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is one of the most researched topics in human resource management, mainly because a satisfied employee is a valuable resource to every organisation. The immense interest in this concept stems from its links to work outcomes like success, intention to leave, and turnover (Bateman, Citation2009). The term describes the psychological and physiological aspects of employees’ satisfaction with their job. Job satisfaction is linked to higher self-efficacy (Bong et al., Citation2009), work commitment, occupational health (Gandhi et al., Citation2014; Khamisa et al., Citation2015), etc. In the view of Aziri (Citation2011), absenteeism tends to be low when satisfaction is high and when satisfaction is low, absenteeism tends to be high.

Affective commitment

This phenomenon was originally defined by Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) as an employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement with an organization. Overtime, it has been extended to include workers’ desire to remain with the organisation, go beyond their formally agreed obligations to their firms and belief in organisational values and norms (Delić et al., Citation2017; Glazer & Kruse, Citation2008). Alternatively, a deficiency in employees’ affective commitment can significantly result in negative consequences including low employee efficiency and high turnover intentions.

As elucidated by Ahmad et al. (Citation2016), the provision of both instrumental and emotional support by supervisors to employees is associated with an increased propensity for these employees to manifest constructive behaviors towards both their employer and their colleagues in the professional context. According to Blau’s (Citation1964) Social Exchange Theory, a strong expression of interest by managers and supervisors in their employees’ personal and professional development can instigate a reciprocal response from the employees. This in turn, fosters a positive working relationship and contributes to enhanced employee commitment to the organization. Employee commitment, a significant factor in employee retention, is further reinforced by the quality of the interaction between supervisors and subordinates (Eisenberger et al., Citation1990). The sense of pride and belonging experienced by employees within an organization is correlated with elevated levels of affective commitment (Rousseau & Aubé, Citation2010). Relating Instrumental co-worker support (ICS) to affective commitment, Orgambídez and Almeida (Citation2020) posit that when employees receive instrumental support, it energizes their work, enhances commitment, and focus on their roles, contributes to a stronger affective commitment, and fosters a greater sense of belonging to the organization.

In the context of emotional co-worker support (ECS) and its impact on employees’ affective commitment, Rousseau and Aubé (Citation2010) argue that support received from co-workers leads to emotionally satisfying work experiences and fosters a lasting emotional attachment to the organization. This assertion aligns with the reciprocity principle, a central tenet of the Social Exchange Theory (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Shore et al., Citation2009). Lee and Peccei (Citation2007) further highlight that perceived organizational support, while crucial in fulfilling human needs for respect and support at work, is not always explicitly articulated. Satisfying emotional co-worker support, therefore, contributes to a stronger emotional bond with the organization as it becomes intrinsically associated with the employees’ perception of the organization.

Research has explored the differential impacts of instrumental and emotional support on employee happiness, with varying findings. This study aims to investigate whether co-worker support (emotional or instrumental) significantly related affective commitment. The accumulation of empirical evidence drawn from multiple studies, including those conducted by Valaei and Rezaei (Citation2016), Rousseau and Aubé (Citation2010), Hoeve et al. (Citation2018), Hoa et al. (Citation2020), Remijus et al. (Citation2019), Uddin (Citation2023), as well as Mensah et al. (Citation2020), consistently indicates a robust and positive association between co-worker support and affective commitment.

From the perspective of the Social Exchange Theory, we argue that repeated social interactions through Co-worker Support can produce commitment that enhance the attachment between individuals and organizations, fostering a sense of gratitude and compassion toward themselves and others (Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara et al., Citation2023). Based on these discussions, it is hypothesized in this study that.

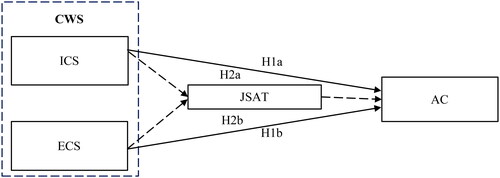

H1a: Instrumental Co-worker Support is positively related to Affective Commitment.

H1b: Emotional Co-worker Support is positively related to Affective Commitment.

The mediating role of job satisfaction

The extensive review of prior studies conducted within the scope of this research unequivocally underscores the far-reaching impact of co-worker support on a multitude of both individual and organizational factors. A prominent outcome of co-worker support is job satisfaction. In the investigation on the relationship between co-worker support and job satisfaction, it has been consistently demonstrated that, the perception of support within organizations among employees has a substantial likelihood of yielding job satisfaction as well as various forms of commitment, including occupational and organizational commitment (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002). This empirical finding has further received validation through the work of Riggle et al. (Citation2009), which substantiates the significant correlation between co-worker support and job satisfaction.

Turning our attention to the link between job satisfaction and affective commitment, it is crucial to note that affective commitment is distinct from normative and continuous commitments, garnering more extensive research attention. Affective commitment represents a form of emotional attachment that generates feelings of fulfillment and a deep sense of dedication to the organization (Bilgin & Demirer, Citation2012). Another pivotal aspect of employee disposition is job satisfaction. According to Budihardjo (Citation2014), job satisfaction wields a substantial influence on affective commitment, serving as a motivating factor that propels employees to strive for greater achievements. Correspondingly, contented employees are inclined to shoulder additional responsibilities, actively endorse the organization’s objectives, and harbor strong affective commitment. Therefore, job satisfaction is expected to maintain a positive and reinforcing association with the attitudes of fellow employees and their commitment to the organization (Ariani, Citation2012). Empirical evidence presented by Budihardjo (Citation2014) substantiates a strong correlation between job satisfaction and affective commitment. Consequently, this research contends that when employees receive both instrumental and emotional support from their colleagues, they are more likely to experience job satisfaction, leading to an enhanced level of affective commitment towards the organization. Based on the arguments put forward in this section, it is hypothesized that ().

H2a: Job Satisfaction mediates the relationship between Instrumental Co-worker Support and Affective Commitment.

H2b: Job Satisfaction mediates the relationship between Emotional Co-worker Support and Affective Commitment.

Methods

Study context

In testing the proposed theoretical model, primary data was collected from full-time employees in some agro processing company’s employees in Ghana. We consider several reasons in choosing Ghana as the research background. Firstly, Ghana has successfully been enlisted as one of the agricultural hubs in the world for many years, primarily due to its place as the world’s second largest producer of cocoa. Also, the socioeconomic and environmental structure of the country offers a rich contextual background to examine the applicability of western market theories to developing market situations. Moreover, Ghana attained middle-income status in 2011 and the country’s GDP growth of 8.8% was judged the highest in Africa in 2019. The country is considered a beacon of democracy in sub-Saharan Africa since it has practiced an uninterrupted democracy since 1992. This has made the country a decent destination for Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs). Ernst and Young (Citation2018) for example, listed Ghana as the largest recipient of foreign direct investment in West Africa, the seventh largest in sub-Saharan Africa, while the IMF projected it among the fastest-growing economies in the world in terms of its GDP growth. Armed with this socioeconomic background, Ghana displays a rich context to investigate how agro processing companies are reacting to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected every economy on the globe. When the transmission rate of the COVID-19 was increasing, the Ghanaian government took several measures to stop the spread of the virus and minimise the health, social, and economic impact of the pandemic. The measures included border closures, and lockdowns (UNWTO, Citation2020). Again, collaborating with the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank, the Ghana Statistical Service undertook a COVID-19 Business Tracker survey aimed at providing critical information to help the Government of Ghana and all stakeholders monitor the effects of the pandemic on businesses (GSS, 2020). The key findings of the survey include closures of several businesses, reduced wages, laying-off of employees, and substantial uncertainty in future sales and employment. The Ghanaian government has been implementing a combination of fiscal and monetary policies to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on businesses and the national economy. The key measures being implemented by the government include the establishment of a Coronavirus Alleviation Programme. Coronavirus Alleviation Programme includes a reduction in the Bank of Ghana policy rate and a drop in regulatory reserve requirement from 10% to 8% to increase supply of credit to the private sector.

Given the size of the estimated revenue decline for SMEs, the Ghanaian government provided a stimulus package of GHS 600 million to be shared among over 200,000 SMEs of which agro-processing industries were inclusive. In order to increase employee commitment in the heat of the pandemic, financial motivation was increased, rendering the already meagre stimulus package) (i.e. GHS3,000 per firm approx. $250) highly inadequate for agro-businesses. Inasmuch as pecuniary incentives are crucial for motivating employees, it is also imperative to ascertain other more enduring and sustainable sources of promoting employee commitment. This is crucial due to the limitations of financial incentives such as fixed budgets and improvement in employees’ needs, desires and expectations.

Data and sample

A quantitative approach with purposive sampling technique was used to gather empirical data from full-time employees of eight (8) Agro-processing firms in Ghana. A total of 250 employees were conveniently selected to participate in the survey. Data from the eight firms show a total employees’ size of 635. Based on this number, a sample size was estimated using the Slovin’s (Citation1960) formula. Slovin’s formula is used to determine a representative sample from a given target population. The formula yielded an estimated sample size of 245.41. However, a sample size of 250 was settled on to ensure that unretrieved or poorly answered questions are catered for. It is worthy to state that this sample size is above the estimated sample size produced by the Slovin’s formula employed in estimating the sample size for the study.

Slovin’s Formula for Sample Determination is given as;

Where;

n = Number of samples =?

N = Total population = 635

e = Error of margin = 5% (0.05)

n = 245.41Chosen ‘n’= 250

In the formula above, ‘n’ represents the sample size, ‘N’ indicates the sample frame and ‘e’ is the error of margin (Utami & Harini, Citation2019).

The study employs both explanatory research design and descriptive surveys. Full-time employees of 8 agro processing companies in Ghana constitute the unit of analysis. The primary tool utilized to gather data is questionnaires. Each participant received a sealed envelope including the questionnaire and a cover letter. We received completed questionnaires in sealed envelopes, because of the uneven and lopsided work schedules and shift arrangements that employees in agro-processing firms faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In utilizing a 3-month time lag approach in collecting the data, Common Method Bias effects were abridged (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). To keep track of returns and participants’ responses, codes were set for the three surveys. We assessed respondents’ demographics and perceptions on Co-worker Support in February 2022. In May 2022, we assessed respondents’ sentiments on job satisfaction. Finally, in August 2022, we assessed respondents’ thoughts on affective commitment. Three hundred and eighty-two (382) respondents (i.e. 89.9%) of the total study population, partook in time one. Time two had 425 completed and returned questionnaires out of 325 participants, or 76.5%. Finally, period three had 273 questionnaires completed and returned, or 64.2%, of the 425 participants. Due to insufficient discrepancies in responses, twenty-three questionnaires were discarded due to inadequate variation in responses. The final sample included 250 individuals. Additionally, of this number, 74% making the majority were between 31-40 years, who are males, and legally married ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

Instrumentalization

Measures were drawn from extant literature and modified to suit the study context. To ensure content validity, thirty (30) full-time employees of the health sector were randomly selected for pilot study. After responding to the questionnaires, participants were also provided comments on the areas in the questionnaire that were problematic or grammatical error identified, after which the researcher made the necessary corrections and revisions. In addition, the questionnaire was discussed with expert practitioners and academics before it was taken to the field for data collection. The items are measured on a 5-Point Likert scale spanning from Strongly Disagree-(1); Disagree-(2); Neutral-(3); Agree-(4), and Strongly Agree-(5). shows details.

Table 2. Measurement of variables.

Data analysis

Measurement model evaluation

To gauge the robustness of the measurement model, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted, encompassing confirmatory factor analysis, assessments of internal consistency (using both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability), an evaluation of convergent validity (utilizing average variance extracted) and an examination of discriminant validity (by calculating the Square Root of the Average Variance Extracted, AVE). These analyses were carried out using AMOS 23. The findings indicate that all Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability coefficients exceed the widely accepted threshold of 0.6, as recommended by Raharjanti et al. (Citation2022). Additionally, the results reveal that each measurement item displays factor loadings surpassing the prescribed 0.6 threshold on their respective constructs (Hair et al., Citation2006). Although the AVEs of the two dimensions of co-worker support did not meet the 0.5 threshold, they were considered acceptable because their Composite Reliability (CR) coefficients exceeded 0.6 and are therefore close to the widely accepted threshold (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) Hence given that the item and construct reliabilities were appropriate, the model can be considered as empirically sound (Hair et al., Citation2006; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Scholars generally agree that, to claim a good model fit, the division of the chi-square by the degree of freedom (χ2/df) should be less than 5 for good convergent validity, the Global Fit Index (GFI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) should be 0.9 and above (Westland, 2019) and NNFI should .90 and above. According to Westland (2019), an appropriate RMSEA and SRMR should not be more than 0.08. Also, the p-value of the chi-square should be above 0.05 (Hair et al., Citation2014). This is evident in . The model fit was enhanced after the CFA test flagged some items under each of the constructs for deletion and covariance. ECS3 was deleted to improve the model fit. Also, ICS5 was deleted. JSAT2 was deleted from the JSAT scale. In the case of AC, AC1, AC2, and AC5 were deleted to improve the model. The results of this test presented in , show good fit indices.

Table 3. Confirmatory factors analysis.

Correlation and discriminant validity

To determine preliminary relationships between the constructs in the study, shows results for means, standard deviations, and correlations of the observed variables. ECS significantly and positively correlates with ICS and JSAT however, it had a significant but negative relationship with AC. ICS positively and significantly correlates with JSAT but has a negative and significant relationship with AC. Finally, JSAT correlates negatively but significantly with AC. This was also used to check multicollinearity. This suggests that all the correlation coefficient values are less than 0.8.

Table 4. Correlation and discriminant validity.

In the assessment of discriminant validity, a pivotal test was conducted by comparing the square roots of the individual AVEs with their corresponding correlation coefficients. As postulated by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the results, as presented along the diagonal of the correlation matrix (), conclusively demonstrate that the square roots of the AVEs markedly exceed the correlations found in the horizontal axis. This observation unequivocally confirms the met criterion for Discriminant Validity, ensuring the distinctiveness of the measurement constructs.

Hypotheses Testing

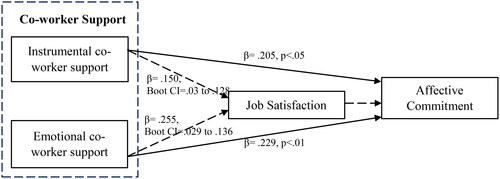

Utilizing the Hayes PROCESS Macro 4.2, this study rigorously examined the four hypotheses that were formulated for investigation. The outcomes of these tests are comprehensively presented in . The first hypothesis (H1a) posited that a constructive and statistically significant relationship exists between emotional co-worker support and affective commitment, with the results indicating a β coefficient of .229 and a significance level (p) of less than 0.001. These results strongly support the contention that when employees actively demonstrate emotional support towards their colleagues within the workplace, it substantially enhances the likelihood of these employees developing a strong affective commitment to the organization.

Table 5. Results of hypotheses testing.

Given the positive and statistically significant result of the relationship between instrumental co-worker support and affective commitment (β= .205, p < 0.005), it can be implied that, when employees are given instrumental support at work, there is a high tendency for employees to become affectively committed to the organization.

Mediation analysis

In investigating the mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between emotional co-worker support and affective commitment, on one end, and between instrumental co-worker support and affective commitment on the other end, Hayes et al. (Citation2017) PROCESS Macro was employed. The strength of this widely used technique lies in its ability to bootstrap indirect effects, indicating robust statistical power as compared to other mediation analytical processes such as the Sobel test. In using this procedure, the number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals was set at 5000 at 95% level of confidence interval.

Per the conceptual model of this study, job satisfaction was tested as a mediator in the relationship between emotional co-worker support and affective commitment. The results in indicate that job satisfaction mediates the relationship, given that the lower and upper confidence intervals (.029 and .136 respectively) of the indirect relationship is significant, based on the premise that zero (0) does not lie within the range of values. This result suggests that emotional co-worker influences affective commitment more when it first, results in job satisfaction. That is, for employees to be affectively committed to their organization, the emotional support employees receive from their co-workers’ ought to result in employees becoming satisfied with their jobs. The third hypothesis of this study (H2a) is therefore supported.

Job satisfaction among employees enhances morals, performance, a positive attitude, and healthy relations among the employees (Mwesigwa et al., Citation2020). Similarly, job satisfaction was tested as a mediator in the relationship between instrumental co-worker support and affective commitment. The results on the indirect effect (ICS–>JS–>AC) compared to that of the direct effect (ICS–>AC) indicate that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between instrumental co-worker support and affective commitment. This conclusion is based on the finding that the indirect path is significant given the lower and upper confidence intervals (LLCI= .03 and ULCI= .128) ().

Discussion

This study focused on investigating the effect of co-worker support (instrumental and emotional) on affective commitment. The study further examined the indirect effect of job satisfaction. First, the study revealed that emotional co-worker support is positively and significantly related to affective commitment, providing support for H1a. This finding confirms similar views and discoveries made in extant literature by Bashir and Long (Citation2015) and Ahmad et al. (Citation2016) who found a positive relationship between emotional co-worker support and affective commitment. Based on the theory of reciprocity, which is a major underpinning of the social exchange theory (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Shore et al., Citation2009), it can be argued that in an organizational climate where emotional support among employees thrive, employees are able to have satisfying work experiences. This further results in developing strong emotional connection and loyalty to the organization (Rousseau & Aubé, Citation2010). Suffice to say, emotional co-worker support, which can be considered as a form of support given and enjoyed in the organizational setting (Lee & Peccei, Citation2007) helps workers in satisfying important human needs for respect and support. Premised on the social exchange theory, employees are motivated to be highly committed to the organization since it provides a source of well-being for the employee.

Similarly, instrumental co-worker support was found to be positively and strongly related to affective commitment, providing support for H1b. This finding is also confirmed in some previous studies that found a positive and significant relationship between instrumental co-worker support and affective commitment (Khairuddin et al., Citation2021; Limpanitgul et al., Citation2014). Just as emotional co-worker support is equally important in making the workplace a happy place to work, previous study implies that instrumental support has the biggest impact on employee happiness (Israel et al., Citation2002). Instrumental co-worker support can also come in the form of employees suggesting to their colleagues how best to go about solving a task (Xu et al., Citation2018). When employees are assisted by their colleagues in dealing with work-related tasks, they can finish their tasks more effectively and move on to address others, with little strain and stress (Xu et al., Citation2018). Among other benefits of instrumental co-worker support, it has been found to enhance employees’ commitment to their organization (Talukder, Citation2019; Zheng & Wu, Citation2018; Zagenczyk et al., Citation2020).

Hypotheses 2a and 2b, which suggested that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between co-worker support (ECS and ICS) and affective commitment were supported respectively. These findings suggest that co-worker support (emotional and instrumental support), have the tendency to result in employees’ satisfaction with their jobs, which further enhances their loyalty and strong attachment to the organization. This process further goes on to emphasize the need for organizations to deliberately create enabling work environments to encourage co-worker support, as the outcomes of this are varied and crucial to the employee and the organization. Extant studies have established positive and strong connections between co-worker support and job satisfaction. Rhoades and Eisenberger (Citation2002) argue that co-worker support in organizations has the likelihood to result in job satisfaction as well as employee commitment (occupational and organizational). Riggle et al. (Citation2009) further confirms that the link between co-worker support and job satisfaction is substantial.

Diverging from the normative and continuous forms of commitment, affective commitment emanates from a deep well of sentimental attachment, instilling within individuals a profound sense of fulfilment and unwavering dedication to an organization (Bilgin & Demirer, Citation2012). The empirical findings derived from this study firmly substantiate the proposition that, when employees receive support from their colleagues, be it in the context of addressing emotional concerns or fulfilling work-related responsibilities, it engenders strong emotional commitment to the organization.

Theoretical and managerial implications

Theoretical implication

From a theoretical point of view, this research advances scholarship on the applicability of the social exchange theory by using the theory to explain the nexus between co-worker support and affective commitment. The findings of the study imply that co-worker support, specifically instrumental and emotional supports play crucial roles in enhancing and sustaining employees’ affective commitment. Thus, we encourage firms to create an environment that enables employees to provide instrumental and emotional support for one another. Also, previous studies have assessed supervisor support and commitment (Ahmad et al., Citation2016; Eisenberger et al., Citation1990). However, very few studies have looked at support from the angle of co-workers (Orgambídez & Almeida, Citation2020), this study extends knowledge in this area of study by exploring the process or mechanism through which co-worker support-commitment links exist in the context of job satisfaction. The study revealed that employees are more satisfied with their jobs when they get instrumental and emotional support from their colleagues which in turn influence their commitment to the organization.

Practical implications

Based on the findings made in this research, the following suggestions are put forward to help management of Ghanaian agro-processing companies and other similar organizations. Management should prioritize organizing workshops and seminars that focus on enlightening employees on the need and benefits of sharing one another’s emotional and psychological issues. In the core values of firms, the need for employees to help each other emotionally should be stressed. In all these, there is the need to have counsellors in firms who will properly superintend the system of providing and creating a healthy atmosphere of emotional support. To improve instrumental support, it is recommended that most work tasks are done in teams and groups. Although this intervention is not likely to automatically enhance instrumental support, it is likely to provide an avenue for employees to build stronger friendships in the work context as well as mutually beneficial work relationships. By this, the right environment will be created for employees to find it easy to help their colleagues with work related tasks, and even in emotional issues.

It was also revealed that job satisfaction fully mediates the relationships between co-worker support and affective commitment. In view of this finding, it is recommended that management of institutions deliberately and consciously create atmospheres of support and unity in the organization to increase the level of affective commitment. When this is ensured, employees’ job satisfaction will also be improved and its attendant outcomes such as low absenteeism, malingering, loafing and employee turnover intention will be reduced.

Conclusion

This research delves into how job satisfaction indirectly affects the relationship between co-worker support and employees’ affective commitment. This suggests that employees become emotionally attached to their organization when they are satisfied with support provided to them willingly by their co-workers on the job. The study draws on the social exchange theory and employs a quantitative research approach to gather data from employees in selected agro-processing firms in Ghana. The data obtained, with the aid of questionnaires, was analyzed using statistical tools such as SPSS (v. 26), AMOS, and the PROCESS Macro. The research findings highlight robust and positive relationships between co-worker support and employees’ affective commitment. This encompasses both emotional and instrumental support exchanged among colleagues, which contributes significantly to fostering strong commitment among employees towards their organizations. This underscores the paramount importance of cultivating supportive work environments, as they play a pivotal role in nurturing employees’ unwavering dedication to their organizations.

Furthermore, the research revealed that job satisfaction had an indirect influence on the relationship between co-worker support and affective commitment. In essence, when employees are emotionally and instrumentally supported by their colleagues, their satisfaction with their job augments. Ultimately, this enhances the commitment level of the employees. In conclusion, this study underscores the importance of co-worker support in going beyond merely influencing employees’ affective commitment. It also substantially enhances job satisfaction. The substantial advantages of fostering emotional and instrumental support among co-workers within organizations cannot be overstated, as it leads to increased job satisfaction and stronger commitment among employees.

Limitations and suggestion for future research

Regardless of the theoretical and practical significance of this study, it was limited in two broad ways; firstly, the study employed a cross-sectional and case study approach. This limited the ability of this study’s findings to be generalized to extensively cover the state and interactions between co-worker support (instrumental and emotional), job satisfaction and affective commitment. This study was cross-sectional, although the results could have been enhanced with insights from narratives from participants. It is therefore suggested that future studies consider mixed method research techniques.

Secondly, this study was also limited in terms of further details on how co-worker support affects affective commitment and job satisfaction. Narrations from participants based on their personal experiences would have added more information to the statistics, hence, providing a comprehensive appreciation of the constructs. To comprehensively examine the process through which co-worker support affects employee commitment, it would also be beneficial to extend the analysis of the Co-worker Support, job satisfaction and affective commitment relationship in two broad ways. First, is by expounding the number of mediators examined in this study’s model to allow for a more systematic analysis of social exchange and socio-emotional explanations in this relationship. For instance, future studies should consider the mediating role of factors such as ethical trustworthiness in peers (Lleo et al., Citation2023) and their compassion (Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara et al., Citation2023). These qualities in peers are pertinent because, the display of compassion among workers can foster OCBs such as instrumental and emotional supports. Alternatively, the analytical model can be extended to include an extensive range of significant employee perceptions, orientations and organizational factors that may significantly moderate these relationships.

Finally, given that employees are likely to repose more trust in their supervisors and peers when they feel supported from by these entities, future research can test the sequential serial mediation roles of ethical trustworthiness and job satisfaction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Darke Isaac Delali

Darke Isaac Delali holds a B.A in Culture and Tourism and M.Phil. in Management and Organizational Development, from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He is currently a Graduate and Research Assistant and Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Human Resource and Organisational Development of the Business School of the same university. His research interests span work-life interface, organisational change, employee wellbeing, employment and gender relations.

Mensah Philip Owusu

Mensah Philip Owusu is a part-time Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Human Resource and Organizational Development at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He also contributes to the Academic Planning and Quality Assurance Unit at Akrokerri College of Education. Philip holds an M.Phil. in Management and Human Resource Strategy from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. His primary research interests include Human Resources Management, Sustainability, and Innovation Capability.

Frank Asamoah Antwi

Frank Asamoah Antwi holds an M.Phil. in Management and Human Resource Strategy from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Work, Employment, and Organisation Development of the Strathclyde Business School, United Kingdom. His research interests span around work-life balance, diversity management, employee wellbeing, employee resilience, and embeddedness.

Phyllis Swanzy-Krah

Phyllis Swanzy-Krah holds an M.Phil. in Management and Human Resource Strategy from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. She is currently an Assistant Lecturer and Ph.D. Candidate at the Department of Human Resource and Organisational Development of the Business School of the same university. Her research interests span organizational behaviour, African studies, employment and gender relations, employee wellbeing and work-life interface.

References

- Aguiar-Quintana, T., Araujo-Cabrera, Y., & Park, S. (2020). The sequential relationships of hotel employees’ perceived justice, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviour in a high unemployment context. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100676

- Ahmad, A., Bibi, P., & Majid, A. H. (2016). Co-worker support as moderator on the relationship between compensation and transactional leadership in organizational commitment. Journal of Economic & Management Perspectives, 10(4), 695–19.

- Ahmad, A., Kura, K. M., Bibi, P., Khalid, N., & Rahman Jaaffar, A. (2019). Effect of compensation, training and development and manager support on employee commitment: The moderating effect of co-worker support. Journal on Innovation and Sustainability RISUS, 10(2), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.23925/2179-3565.2019v10i2p39-55

- Ahmad, M., Firman, K., Smith, H., & Smith, A. (2018). Short measures of organizational commitment, citizenship behaviour and other employee attitudes and behaviours. Business and Management Studies: An International Journal, 6(3), 516–550. https://doi.org/10.15295/bmij.v6i3.391

- Ahmed, A., Khuwaja, F. M., Brohi, N. A., Othman, I., & Bin, L. (2018). Organizational factors and organizational performance: A resource-based view and social exchange theory viewpoint. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(3), 579–599. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i3/3951

- Akgunduz, Y., & Eryilmaz, G. (2018). Does turnover intention mediate the effects of job insecurity and co-worker support on social loafing? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 68, 41–49 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.09.010

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Ampofo, E. T. (2020). Mediation effects of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between organisational embeddedness and affective commitment among frontline employees of star–rated hotels in Accra. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.06.002

- Ariani, D. W. (2012). Leader-member exchanges as a mediator of the effect of job satisfaction on affective organizational commitment: An empirical test. International Journal of Management, 29(1), 46.

- Arora, V., & Kamalanabhan, T. J. (2013). Linking supervisor and co-worker support to employee innovative behavior at work: Role of psychological conditions [paper presentation]. Proceedings of the Academic and Business Research Institute International Conference, New Orleans. http://www.aabri.com/OC2013Proceedings.Html.

- Asamoah Antwi, F., Mensah, H. K., Mensah, P. O., & Delali Darke, I. (2023). Crisis-induced HR practices and employee resilience during COVID-19: Evidence from hotels. Anatolia, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2023.2215244

- Attiq, S., Wahid, S., Javaid, N., & Kanwal, M. (2017). The impact of employees’ core self-evaluation personality trait, management support, co-worker support on job satisfaction, and innovative work behaviour. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32(1), 247–271.

- Aziri, B. (2011). Job satisfaction: A literature review. Management Research & Practice, 3(4), 1–10.

- Bashir, N., & Long, C. S. (2015). The relationship between training and organizational commitment among academicians in Malaysia. Journal of Management Development, 34(10), 1227–1245. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2015-0008

- Bateman, G. (2009). Employee perceptions of co-worker support and its effect on job satisfaction. Work Stress and Intention to Quit. Master of Science in Applied Psychology, 1–52.

- Beehr, T. A., & McGrath, J. E. (1992). Social support, occupational stress, and anxiety. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 5(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809208250484

- Bilgin, N., & Demirer, H. (2012). The examination of the relationship among organizational support, affective commitment, and job satisfaction of hotel employees. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 51, 470–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.08.191

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Bong, Y. S., So, H. S., & You, H. S. (2009). A study on the relationship between job stress, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction in nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 15(3), 425–433.

- Budihardjo, A. (2014). The relationship between job satisfaction, affective commitment, organizational learning climate and corporate performance. GSTF Journal on Business Review (GBR), 2(4).

- Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Kelsh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. As cited in Cook, JD, Hepworth, SJ, Wall, TD, & Warr, PB (Eds), The experience of work: A compendium and review of 249 measures and their use.

- Chadwick, K. A., & Collins, P. A. (2015). Examining the relationship between social support availability, urban center size, and self-perceived mental health of recent immigrants to Canada: A mixed-methods analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.036

- Chandrasekar, K. (2011). Workplace environment and its impact on organizational performance in public sector organizations. International Journal of Enterprise Computing and Business Systems, 1(1), 1–19.

- Chou, R. J. A., & Robert, S. A. (2008). Workplace support, role overload, and job satisfaction of direct care workers in assisted living. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49(2), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650804900207

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Cropanzano, R., & Rupp, D. E. (2008). Social exchange theory and organizational justice: Job performance, citizenship behaviors, multiple foci, and a historical integration of two literatures. Research in Social Issues in Management: Justice, Morality, and Social Responsibility, 63, 99.

- Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., & Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099

- De Clercq, D., Azeem, M. U., Haq, I. U., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2020). The stress-reducing effect of co-worker support on turnover intentions: Moderation by political ineptness and despotic leadership. Journal of Business Research, 111, 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.064

- Delić, M., Slåtten, T., Milić, B., Marjanović, U., & Vulanović, S. (2017). Fostering learning organisation in transitional economy–The role of authentic leadership and employee affective commitment. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 9(3/4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-02-2017-0012

- DiPietro, R. B., Moreo, A., & Cain, L. (2020). Well-being, affective commitment, and job satisfaction influences on turnover intentions in casual dining employees. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(2), 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1605956

- Doerwald, F., Scheibe, S., Zacher, H., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2016). Emotional competencies across adulthood: State of knowledge and implications for the work context. Work, Aging and Retirement, 2(2), 159–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw013

- Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.51

- Eisenberger, R., Lynch, P., Aselage, J., & Rohdieck, S. (2004). Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(6), 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264047

- Eisenberger, R., Shoss, M. K., Karagonlar, G., Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., Wickham, R. E., & Buffardi, L. C. (2014). The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(5), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1877

- Ernst and Young. (2018). Global review 2018: How do we create value and build trust in this transformative age. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/global-review/2018/ey_global_review_2018_v11_hr.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjX7arDmdODAxXhQEEAHSHdCcoQFnoECBoQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0tpYBZd7aPq_zDGCaXqXTE

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics.

- Freudenreich, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Schaltegger, S. (2020). A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04112-z

- Fritzsche, B. A., & Parrish, T. J. (2005). Theories and research on job satisfaction. In Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 180–202).

- Gandhi, S., Sangeetha, G., Ahmed, N., & Chaturvedi, S. K. (2014). Somatic symptoms, perceived stress and perceived job satisfaction among nurses working in an Indian psychiatric hospital. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 12, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.015

- Gao-Urhahn, X., Biemann, T., & Jaros, S. J. (2016). How affective commitment to the organization changes over time: A longitudinal analysis of the reciprocal relationships between affective organizational commitment and income. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(4), 515–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2088

- Gasengayire, J. C., & Ngatuni, P. (2019). Demographic characteristics as antecedents of organizational commitment (p. 1). Faculty of Business Management the Open University of Tanzania.

- Glazer, S., & Kruse, B. (2008). The role of organizational commitment in occupational stress models. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(4), 329. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013135

- Gooty, J., & Yammarino, F. J. (2016). The leader–member exchange relationship: A multisource, cross-level investigation. Journal of Management, 42(4), 915–935. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313503009

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Habtoor, N. (2016). Influence of human factors on organizational performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2014-0016

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 6). Prentice-Hall.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: Process versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

- Hoa, N. D., Ngan, P. T. H., Quang, N. M., Thanh, V. B., & Quyen, H. V. T. (2020). An empirical study of perceived organizational support and affective commitment in the logistics industry. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 7(8), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no8.589

- Hoeve, Y. T., Brouwer, J., Roodbol, P. F., & Kunnen, S. (2018). The importance of contextual, relational, and cognitive factors for novice nurses’ emotional state and affective commitment to the profession. A multilevel study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(9), 2082–2093 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13709

- Israel, B. A., Farquhar, S. A., Schulz, A. J., James, S. A., & Parker, E. A. (2002). The relationship between social support, stress, and health among women on Detroit’s East Side. Health Education & Behavior, 29(3), 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810202900306

- Jackson, L. T., & Fransman, E. I. (2018). Flexi work, financial well-being, work-life balance, and their effects on subjective experiences of productivity and job satisfaction of females in an institution of higher learning. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.1487

- Khairuddin, K. N., Omar, Z., Krauss, S. E., & Ismail, I. A. (2021, May). Fostering co-worker support: A strategic approach to strengthen employee relations in the workplace.

- Khamisa, N., Oldenburg, B., Peltzer, K., & Ilic, D. (2015). Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(1), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120100652

- Kim, D., Moon, C. W., & Shin, J. (2018). Linkages between empowering leadership and subjective well-being and work performance via perceived organizational and co-worker support. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2017-0173

- Kowalski, T. H., & Loretto, W. (2017). Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace.

- Lee, J., & Peccei, R. (2007). Perceived organizational support and affective commitment: The mediating role of organization-based self-esteem in the context of job insecurity. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 28(6), 661–685. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.431

- Lewis, D. (2004). Bullying at work: The impact of shame among university and college lecturers. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32(3), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880410001723521

- Limpanitgul, T., Boonchoo, P., Kulviseachana, S., & Photiyarach, S. (2017). The relationship between empowerment and the three-component model of organizational commitment: An empirical study of Thai employees working in Thai and American airlines. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-07-2015-0069

- Limpanitgul, T., Boonchoo, P., & Photiyarach, S. (2014). Co-worker support and organizational commitment: A comparative study of Thai employees working in Thai and American airlines. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 21, 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2014.08.002

- Lleo, A., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Guillen, M., & Marrades-Pastor, E. (2023). The role of ethical trustworthiness in shaping trust and affective commitment in schools. Ethics & Behavior, 33(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2022.2034504

- Lyons, B. D., & Marler, J. H. (2011). Got image? Examining organizational image in web recruitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111099628

- Mafini, C., & Pooe, D. R. (2013). The relationship between employee satisfaction and organizational performance: Evidence from a South African government department. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(1), 00-00. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i1.1090

- Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576

- Maner, J. K., Luce, C. L., Neuberg, S. L., Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S., & Sagarin, B. J. (2002). The effects of perspective taking on motivations for helping: Still no evidence for altruism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(11), 1601–1610. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702237586

- Martini, I. A. O., Rahyuda, I. K., Sintaasih, D. K., & Piartrini, P. S. (2018). The influence of competency on employee performance through organizational commitment dimension. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 20(2), 29–37.

- Mathieu, M., Eschleman, K. J., & Cheng, D. (2019). Meta-analytic and multiwave comparison of emotional support and instrumental support in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(3), 387. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000135

- Mensah, C., Appietu, M. E., & Asimah, V. K. (2020). Work-based social support and hospitality internship satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 27, 100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2020.100242

- Mwesigwa, R., Tusiime, I., & Ssekiziyivu, B. (2020). Leadership styles, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among academic staff in public universities. Journal of Management Development, 39(2), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2018-0055

- Ng, T. W. H., & Sorensen, K. L. (2008). Toward a further understanding of the relationships between perceptions of support and work attitudes: A meta-analysis. Group and Organization Management, 33 (3), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601107313307

- Orgambídez, A., & Almeida, H. (2020). Supervisor support and affective organizational commitment: The mediator role of work engagement. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(3), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945919852426

- Pinna, R., De Simone, S., Cicotto, G., & Malik, A. (2020). Beyond organizational support: Exploring the supportive role of co-workers and supervisors in a multi-actor service ecosystem. Journal of Business Research, 121, 524–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.022

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Raharjanti, N. W., Wiguna, T., Purwadianto, A., Soemantri, D., Indriatmi, W., Poerwandari, E. K., & Levania, M. K. (2022). Translation, validity, and reliability of decision style scale in forensic psychiatric setting in Indonesia. Heliyon, 8(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09810

- Rastogi, M. (2019). Determinants of work engagement among nurses in Northeast India. Journal of Health Management, 21(4), 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063419868556

- Remijus, O. N., Chinedu, O. F., Maduka, O. D., & Ngige, C. D. (2019). Influence of organizational culture on job satisfaction and workers retention. International Journal of Management and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 83–102.

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

- Riggle, R. J., Edmondson, D. R., & Hansen, J. D. (2009). A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 1027–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.003

- Rousseau, V., & Aubé, C. (2010). Social support at work and affective commitment to the organization: The moderating effect of job resource adequacy and ambient conditions. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150(4), 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903365380

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Scheibe, S. (2019). Predicting real-world behaviour: Cognition-emotion links across adulthood and everyday functioning at work. Cognition and Emotion, 33(1), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2018.1500446

- Scott, K. L., Zagenczyk, T. J., Schippers, M., Purvis, R. L., & Cruz, K. S. (2014). Co-worker exclusion and employee outcomes: An investigation of the moderating roles of perceived organizational and social support. Journal of Management Studies, 51(8), 1235–1256. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12099

- Settoon, R. P., & Mossholder, K. W. (2002). Relationship quality and relationship context as antecedents of person-and task-focused interpersonal citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.255

- Shahid, A., & Azhar, S. M. (2013). Gaining employee commitment: Linking to organizational effectiveness. Journal of Management Research, 5(1), 250. https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v5i1.2319

- Shim, S., Luch, R., & O’Brien, M. (2002). Emotional intelligence, moral reasoning and transformational leadership. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 23 (3), 198–204.

- Shin, Y., Hur, W. M., & Choi, W. H. (2020). Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(11), 1417–1438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1407352

- Shore, L. M., Coyle-Shapiro, J. A., Chen, X. P., & Tetrick, L. E. (2009). Social exchange in work settings: Content, process, and mixed models. Management and Organization Review, 5(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2009.00158.x

- Slovin, E. (1960). Slovin' s formula for sampling technique. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Hasanein, A. M., Aliedan, M. M., & Abdallah, H. S. (2020). The impact of transactional and transformational leadership on employee intention to stay in deluxe hotels: Mediating role of organizational commitment. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358420972156

- Spector, P. E. (2021). Industrial and organizational psychology: Research and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Taderera, F., & Al Balushi, M. S. (2018). Analysing oman supply chain practices versus global best practices. Global Journal of Business Disciplines, 2(1), 86–106.

- Talukder, A. M. H. (2019). Supervisor support and organizational commitment: The role of work–family conflict, job satisfaction, and work–life balance. Journal of Employment Counseling, 56(3), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12125

- Tang, S. W., Siu, O. L., & Cheung, F. (2014). A study of work–family enrichment among Chinese employees: The mediating role between work support and job satisfaction. Applied Psychology, 63(1), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00519.x

- Tepper, B. J., Carr, J. C., Breaux, D. M., Geider, S., Hu, C., & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 109(2), 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.03.004

- Thompson, E.R. and Phua, F.T.T. (2012). A brief Index of affective job satisfaction. Group and Organization Management, 37(3), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601111434201

- Torka, N., & Schyns, B. (2010). On the job and co-worker commitment of Dutch agency workers and permanent employees. The International Journal of Human Resource.

- Uddin, M. (2023). Investigating the impact of perceived social support from supervisors and co-workers on work engagement among nurses in private healthcare sector in Bangladesh: The mediating role of affective commitment. Journal of Health Management, 25(3) 653–665, https://doi.org/10.1177/09720634231195162

- UNWTO. (2020). Impact assessment of the COVID-19 outbreak on international tourism. https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism

- Utami, P.P. and Harini, H., (2019). The effect of job satisfaction and absenteeism on teacher work productivity. Multicultural Education, 5(1).

- Valaei, N., & Rezaei, S. (2016). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Management Research Review.

- Vignoli, D., Mencarini, L., & Alderotti, G. (2020). Is the effect of job uncertainty on fertility intentions channeled by subjective well-being? Advances in Life Course Research, 46, 100343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100343

- Wongboonsin, K., Dejprasertsri, P., Krabuanrat, T., Roongrerngsuke, S., Srivannaboon, S., & Phiromswad, P. (2018). Sustaining employees through co-worker and supervisor support: Evidence from Thailand. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting, 11(2), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.22452/ajba.vol11no2.6

- Xu, S., Martinez, L. R., Van Hoof, H., Tews, M., Torres, L., & Farfan, K. (2018). The impact of abusive supervision and co-worker support on hospitality and tourism student employees’ turnover intentions in Ecuador. Current issues in Tourism, 21(7), 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1076771

- Xu, S., Van Hoof, H., Serrano, A. L., Fernandez, L., & Ullauri, N. (2017). The role of co-worker support in the relationship between moral efficacy and voice behavior: The case of hospitality students in Ecuador. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 16(3), 252–269, https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2017.1253431

- Zagenczyk, T. J., Purvis, R. L., Cruz, K. S., Thoroughgood, C. N., & Sawyer, K. B. (2020). Context and social exchange: Perceived ethical climate strengthen the relationships between perceived organizational support and organizational identification and commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1706618

- Zheng, J., & Wu, G. (2018). Work-family conflict perceived organizational support and professional commitment: A mediation mechanism for Chinese project professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020344

- Zheng, Y., Wang, J., Doll, W., Deng, X., & Williams, M. (2018). The impact of organisational support, technical support, and self-efficacy on faculty perceived benefits of using learning management system. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(4), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1436590

- Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2023). Compassion in hotels: Does person–organization fit lead staff to engage in compassion-driven citizenship behavior? Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 19389655231178267. https://doi.org/10.1177/19389655231178267