Abstract

Over decades, public procurement in Tanzania experienced critical reforms; however, not much is known about the reforms and hence there is a dearth of comprehensive reviews about them. The current study reviews existing literature relating to public procurement reforms, practices, and compliance in Tanzania. By employing a systematic literature review, the study draws upon 65 publications from Scopus and Google Scholar databases. Findings unveil that the implementation of public procurement laws and regulations has significantly improved transparency, accountability, and fairness in public procurement undertakings. The foundation for a well-organized institutional framework that emphasizes decentralization, standardization, and governance over public procurement has also been established by these reforms. Despite these positive contributions, certain reforms have introduced challenges due to interference and uncoordinated efforts that hamper public procurement activities. The study exclusively focuses on journal articles from Scopus and Google Scholar, excluding other publication forms like book reviews and conference proceedings. While acknowledging this limitation, the article serves as the pioneering systematic review profiling public procurement reforms in Tanzania, shedding light on professional dilemmas and compliance issues. Given the limited literature on the subject, this study enriches the existing knowledge and offers valuable insights for scholars, procurement practitioners, public entities, and stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, governments are the largest spenders of public funds due to the challenge of meeting the ‘public requirements’ of their citizens regarding infrastructure and public services through public procurement contracts. Thus, public procurement, among other things, provides the foundation for achieving socio-economic, environmental, and technological goals (World Bank, Citation2016). The construction of public infrastructure (e.g., schools, universities, health, and transport), acquisition of hospital facilities and supplies, and connectivity of computer systems in public buildings are all examples of sectors impacted by public procurement (World Bank, Citation2018). Mostly, the procurements are done from the private sector, and the figures, of course, vary from country to country, but generally, the sheer amounts spent have a significant impact on the respective country’s economy. Similarly, public procurement undertakings drive product development innovations and service provision to fulfill societal needs and support public objectives, including employment creation, income generation, and economic growth (Knutsson & Thomasson, Citation2014; Talebi & Rezania, Citation2020).

The World Bank (Citation2018) approximates that governments worldwide spend about 9.5 trillion USD each year on the acquisition of goods, works, and related services. This substantial expenditure has, in turn, heightened public demand for greater transparency and efficiency in government spending. For instance, in the Netherlands, nearly 45% of government expenditure goes towards procurement, constituting almost 20% of the national income (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, Citation2020). The experience of Greece shows that the weight of procurement is approximately 20% of the total expenditure, however, the size remains significant taking about 10% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, Citation2020). Public procurement in countries under the Organisation for Economic Development (OECD) seems to be skewed on health expenditures that accounts for almost one-third (29.8%) followed by economic affairs (17%), education (11.9%), defence (10.1%) and social protection (9.8%) (OECD, Citation2017).

Similarly, in many African countries, the procurement of goods, services and works in the public sector accounts for more than 10% of the GDP. This means that governments are important spenders for development outcomes (Hoekman & Sanfilippo, Citation2018). As of 2016, Djankov et al. (Citation2016) reported that the Sub-Saharan Africa came next to South Asia with 14.9% and 19.3% of public procurement share in the GDP respectively. In Eritrea for example, public procurement is a whopping 33% of GDP while in Angola, the share is 26% of GDP. Ideally, public procurement is seen as a means to achieve policy goals as it is associated with being a lever of socio-economic reforms and a means of saving public money for governments (Nijboer et al., Citation2017). With a significant portion of public funds allocated to procurement, it becomes crucial for associated activities to be carried out effectively, efficiently, and with transparency and high integrity. This will ensure timely and quality delivery of goods and works as well as high quality of service while safeguarding the interests of the public.

The span of public procurement in Tanzania covers the acquisition of goods, services, works and disposal of public assets by tender. Currently, such undertakings are regulated by the Public Procurement Act (PPA) 2011 (United Republic of Tanzania (URT), 2011) and amendments 2016 (URT, Citation2016) as well as PPR of 2013 (URT, Citation2013) and 2016. The Controller and Auditor General (CAG) (Citation2019a) observed that a total of Tanzania Shillings (TZS) 1,302,794,588,840 was used by 185 Local Government Authorities (LGAs) in undertakings related to procurement of goods, works and services as per PPR and guidelines. The aforementioned spending pattern is intimately related to socio-economic well-being of the public, and is often associated with high perceived procurement and financial risks. Hence, efficient and effective public procurement is essential for responding to the public needs while complying with principles of good governance and professional etiquette. This in turn restores and maintains trust in the public sector which is critical for qualifying the legitimacy of public procurement which is perceived by the level of integrity and transparency of the procurement staff and procurement process respectively (OECD, Citation2009)

The guiding principles of good governance closely align with the pillars of public procurement, as emphasized in the PPA of 2011, which advocates for fairness, accountability, fair competition, integrity, and transparency in public procurement processes. Transparency and accountability are central and lay the foundation for integrity among professionals for any public procurement system (Ntangeki et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the pursuit of professional and moral practices should not be underestimated in this domain. This emphasis on professionalism and efficiency has catalyzed numerous reforms in institutionalization, policy and legal frameworks, as well as decentralization and procurement procedures, all aimed at enhancing performance (Mrope et al., Citation2017a; Changalima & Mdee, Citation2023). The ongoing reforms in public procurement systems can be attributed to fiscal pressure, the demand for professional practices, and advancements in information and communication technologies. Governments, in their bid to manage resources effectively and improve efficiency in public spending through procurement, are actively promoting system reforms by adopting and/or developing new methodologies, technologies, strategies, and tools (OECD, Citation2017). These initiatives hold critical strategic importance, as the reforms in public procurement aim to fortify economic growth and ensure the effective investment of taxpayers’ money (public funds). Notably, progress has been achieved by translating public policies into tangible results for the public, delivering essential services, and implementing programs and projects that focus on improving the overall well-being of the public (World Bank, Citation2012).

Despite numerous initiatives and efforts, the reforms implemented thus far in public procurement systems often face significant challenges, particularly in the realms of accountability and transparency (Sama, Citation2022). These challenges, such as conflicts of interest, non-compliance, elements of fraud and corruption, and political interferences, collectively tarnish the image of public procurement, eroding public trust and confidence (Komakech, Citation2016; Basheka, Citation2017; Mrope et al., Citation2017a). Illustrating this issue, the case of procurement in development projects in Tanzania is noteworthy. The audit report for the financial year 2017/2018 revealed that goods worth TZS 1,131,519,540.42 were procured and utilized without undergoing thorough inspection, in violation of Regulation 245 of the PPR (CAG, Citation2019c). Accepting goods without proper technical inspections creates vulnerabilities for acquiring sub-standard products due to collusion, fraud, and conflict of interests. The implications of using sub-standard goods in providing public services, such as medical and hospital supplies, could be severe and even fatal for the public.

The report also highlighted that 17 health sector projects failed to provide evidence for the delivery of goods worth TZS 8,945,758,303, contravening order no. 71(1) (b) of the Local Government Financial Memorandum 2009 and regulation 114 of PPR. Such practices raise concerns about the maintenance of professionalism and adherence to established laws and regulations that constitute the legal framework for public procurement. Additionally, they suggest that the significance of acclaimed reforms may not be fully recognized, and compliance with laws and regulations appears inconsistent (Matto, Citation2017a). Apparently, the reforms are perceived as guidance for optimal implementation rather than being fully institutionalized and practically upheld to achieve the expected goals. Consequently, it becomes evident that public procurement in Tanzania has undergone significant reforms over decades. However, there is limited understanding of these reforms and their impact on public procurement practices at large. To address this knowledge gap, this study aims to profile the procurement reforms, assess their implications, and subsequently examine public procurement practices based on the undertaken reforms.

2. Methods

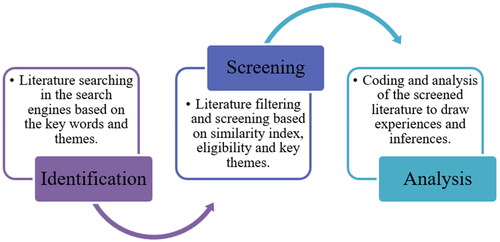

This study relies on the systematic literature review (SLR) (see ) as it has been articulated as a means for ensuring the quality of evidence in reviews (Alatawi et al., Citation2023; Lu et al., Citation2022). Therefore, SLR procedures, as applied by other previous studies in business and management areas, were followed. Firstly, the study determines the eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the general aim of the study (Alhossini et al., Citation2021; Ibrahim et al., Citation2022), which is to provide information regarding public procurement reforms in terms of developments. The study included only publications linked to the domain of public procurement reforms, especially in the Tanzanian context. Scopus and Google Scholar were used as predominant search engines with more information regarding public procurement undertakings in Tanzania. The Scopus database was included because it indexes a number of high-quality journals with publications related to the current study course. Also, Google Scholar was engaged as a relevant search engine, as most information regarding audit reports related to Tanzanian public procurement undertakings can be retrieved there rather than from journal sources. Therefore, Scopus was relevant to obtain research publications limited to journal articles, and Google Scholar was crucial for retrieving information regarding procurement audit reports and public procurement undertakings.

On the other hand, the search strategy was guided with the combination of the following keywords: ‘procurement reforms’ OR ‘public procurement’ OR ‘procurement practices’ OR ‘professional practices in procurement’ AND ‘Tanzania’ in the article title, abstract, and keywords. The search was done in Scopus and limited to journal articles published in English only. The Scopus database produced 19 documents that were published between 2013 and 2023 (during the date of the search on 1st December 2023), with the Journal of Public Procurement and Cogent Business and Management being leading sources of publications, each with 4 articles. However, out of 19 articles, 1 publication was removed as it was not relevant to meeting the study’s main purpose. Furthermore, to ensure that relevant information from the ground is included in the analysis, the search included reports retrieved from the websites of office of CAG and the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA), as these two organs are involved in reporting on procurement audits in the Tanzanian public sector. Also, reports from OECD and World Bank were included as they have information regarding public procurement undertakings in most countries, including Tanzania. Therefore, audit reports published in 2018–2019, 2019–2020, 2020–2021, 2021–2022 (the 4 recent years) were included as they encompass recent information regarding what is happening on the ground in public procurement undertakings in Tanzania. So, before obtaining relevant literature from Google Scholar, 18 journal articles from Scopus were included, plus 4 audit reports from PPRA and 4 others from CAG’s office, making a total of 26 documents for review.

In addition, the study involved Google Scholar during the search, which was limited to publications from 2000 to 2020 to capture relevant literature on the major reforms in the Tanzanian public procurement system. It should be noted that, the major reforms started in the year 2000, leading to the enactment of the first-ever PPA and PPR in 2001. Since then, other significant reforms have taken place up to the year 2020 in both practices and legislation. The ongoing process aims to incorporate the best practices and systems. The advanced search was conducted with the following search strategy (allintitle: ‘procurement reforms’ OR ‘public procurement’ OR ‘procurement practices’ OR ‘professional practices in procurement’ AND ‘Tanzania’), which produced 55 publications (from 2000 to 2020). However, 16 publications were removed, including 13 dissertations and 3 duplicates (from the Scopus database). Therefore, given this information, the study finally included 65 documents for review, under which 18 journal articles were from the Scopus database, 8 audit reports from PPRA and CAG’s office, and 39 documents from Google Scholar. Building on the aforementioned themes, we conducted basic coding (open, axial, and selective coding). Subsequently, constant comparison analysis was performed for data analysis, following the approach outlined by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (Citation2008) and Onwuegbuzie et al. (Citation2012). The codes were guided by key themes to ensure consistency, and the similarities and differences between the codes were scrutinized and examined to facilitate grouping and coherence.

3. Findings and discussions

3.1. Legal and institutional reforms

Reforms in public procurement primarily focus on policy and systemic changes aimed at altering legal structures and both broader and specific institutional frameworks involved in managing the public procurement process (Basheka, Citation2017). Subsequent reforms have led to the establishment of new responsive systems and processes, representing a significant departure from traditional approaches. Consequently, any reforms in public procurement play a vital role in enhancing service delivery, governance, and overall public sector performance. Over the past decade, developing countries have actively pursued reforms in their public procurement systems to enhance accountability, competition, transparency, and value for money (Komakech, Citation2016). These acclaimed reforms have predominantly involved revising procurement legislation, establishing procurement regulatory authorities, standardizing bidding processes, and adopting electronic procurement practices (Telgen et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the ensuing discussions of the findings are primarily centered around the parameters of the aforementioned reforms.

3.1.1. Establishment and revisions on the public procurement laws and regulations

The history of procurement legal reforms in Tanzania dates back to 1961 when the exchequer and audit ordinance no. 21 was enacted as a legal mechanism to control public procurement and supply activities in the government sector (Matto, Citation2017a). Despite subsequent legal and institutional reforms over the years, they proved less effective in addressing observed loopholes and flaws in the public procurement system. The legislation and regulations were fragmented, lacking a unified framework to guide public procurement practices operating under the same government umbrella. For instance, the central government (ministries) followed the financial orders part iii (stores regulations of 1965) in accordance with the exchequer and audit ordinance CAP 439 (1961) (Nkinga, Citation2003), while concurrently, the ministry of works adhered to the general regulations (1991) for the procurement of supplies, services, and works.

Meanwhile, the central medical stores department was operating under the medical stores tender board act (1993). Similarly, public procurements in LGAs were regulated by the local government (district authorities) act no. 7 of 1982, the local government (urban authorities) act no. 8 of 1982, and the local government (finances) act no. 9 of 1982 (Nkinga, Citation2003). Thus, the absence of unified procurement legislation throughout the government led to a number of challenges in harmonizing and standardizing procurement practices and enforcing professionalism in public procurement. Additionally, there was the absence of a regulatory body for enforcing public procurement rules, regulations, and procedures. In response to that need, the government in the mid-90s initiated numerous reforms in the public procurement system aiming at making it more efficient and transparent in line with the best professional practices (URT, Citation2013). These reforms consequently resulted in the enactment of the PPA (2001) followed by the PPA (2004) and Regulations (2005), PPA (2011) and its Regulations (2013), and thereafter Amendments (2016).

The observed reforms on the legal framework were necessary in order to provide foundation, synergy and harmony among the institutions supposed to oversee public procurement. They also framed procedures to ensure that government spending on procurement are conducted fairly and transparently. The PPA (2001) came as a result of the recommendations made by consultants who were commissioned to study the public procurement system and make recommendations. The findings highlighted the absence of a well-structured regulatory body to enforce the rules and procedures; inadequate legal framework for procurement of works and employment of consultants; and scattered procurement regulations that had loopholes with no enforceable penalties (Nkinga, Citation2003). The report pinpointed the need for establishing policies and a public procurement structure supported by well-articulated regulations. Thus, the highlighted recommendations led to the enactment of the PPA (PPA 2001).

The PPA 2001 was supported by two regulations, namely the Public Procurement (Selection and Employment of Consultants) Regulations (2001) and Regulations for Procurement of Goods and Works (2001). Among the key contributions of PPA (2001) was the introduction of procurement thresholds and centralization of the procurement system under the umbrella of the Central Tender Board (CTB). However, as the first legislation, the PPA (2001) and its Regulations (2001) had several weaknesses, including the centralization of procurement undertakings that created unnecessary bureaucracies and the presence of conflicts of interest (accounting officers (AOs) and Councillors membership in the TBs). Additionally, there were insufficient human resources and procurement training systems, as well as a lack of standardized documents as guidance on the application of the Regulations (Matto, Citation2017a). This led to inappropriate and differing procedures being followed among entities that were basically supposed to operate under the same regulatory framework.

3.1.2. The PPA (2004), decentralization and establishment of PPRA

In 2003, the government initiated a country procurement review to assess and address the implementation of the PPA 2001 and its weaknesses, as there were numerous genuine complaints and dilemmas. The outcome of the review led to the enactment of the PPA (PPA 2004) and its Regulations (2005). The PPA (2004) became effective in May 2005 and was supported by two regulations, namely the PPR for Goods, Works, and Non-Consultancy Services (Government Notice 97) and the PPR for the Selection and Employment of Consultants (Government Notice 98). The PPA (PPA, 2004) significantly decentralized procurement undertakings to Procuring Entities with fewer limitations compared to the preceding legislation. This decentralization has resulted in improved delivery performance, as the system has been well-articulated to enhance performance by reducing lead time and overall delivery time for most procuring entities. Notably, the Act established the PPRA under the Ministry of Finance, replacing the Central TB. Additionally, the composition of TBs was changed, with the AO no longer serving as the Chairman. Membership of Councillors was removed from LGAs to prevent conflicts of interest. Furthermore, the private sector secured representation in the PPAA, established specifically to handle appeals and complaints.

3.1.3. The PPA (2011), revisited procurement practices and establishment of e-procurement system

Despite the new Act (then known as PPA - 2004) being accommodating and incorporating the recommendations from the Country Procurement Assessment Report (2003), its six years under implementation revealed several challenges, leading to public outcry about inefficiencies in public procurement processes (Maliganya, Citation2015). Therefore, in 2011, the PPA (2004) was repealed and replaced by a new but almost identical Act, namely the PPA (PPA, 2011). The Act became operational after regulations were gazetted on December 20, 2013. Unlike the previous legislation, PPA (2011) had only one regulation, namely the PPR 2013 (Government Notice, 446). The Act established the Policy Division and created room for the formulation of the public procurement policy and hence introducing the Public Procurement Policy Division (PPPD).

Provisions for undertaking emergency procurement, procurement of used equipment (such as aircraft, ships, and railway equipment), and electronic procurement were introduced. Also, new procurement methods (e.g., force account, micro-value procurement) were introduced. Among other benefits, this legislation was able to reduce procurement transaction costs through pooled procurement by the Government Procurement Service Agency (GPSA). There was an increase in competition and transparency, enhanced accountability, and most importantly, it laid the groundwork for the execution of the Tanzanian National e-Procurement System (TANePS). In the realm of e-procurement, the current focus is on the implementation phase, moving towards fully automating all procurement procedures with the new launched e-procurement system known as, National e-Procurement System of Tanzania (NeST) moving away from TANePS. This newly introduced electronic system is geared towards supporting additional modules for e-procurement in the Tanzanian public sector.

The remarkable achievements observed were not immune to flaws. Two years down the road, the outcry of inefficiencies, elements of corruption, and failure to achieve value for money persisted, prompting concern from the central government. Consequently, there was a call to harmonize and amend some provisions in the PPA (2011) to cut down the ‘red tapes’ experienced in the implementation of development projects. This initiative led to amendments to the PPA in 2016. The amendments, among other things, considered the need for market intelligence and taking advantage of prevailing prices, increasing opportunities for the participation of special groups, reducing the total ownership cost, and promoting industrial development using locally produced goods and services. Key features of the Amendments (2016) include provisions for direct procurement from manufacturers, harmonization of provisions for contract vetting and ratification, and minimization of the tendering stage period.

3.1.4. Participation of SMEs in public procurement opportunities and collaborations among public entities

One of the significant legal reforms in public procurement is the encouragement of private sector involvement (Mrope et al., Citation2017b). This has led foundation of participation of SMEs in public procurement opportunities, particularly by favoring local suppliers, service providers, and contractors (Changalima et al., Citation2022; Israel & Kazungu, Citation2019). This is crucial because many of these enterprises lack sufficient knowledge, hindering the attainment of necessary documentation required in the public procurement process (Ismail & Changalima, Citation2022). Apart from the observed achievements and loopholes, reforms have led to the establishment of a number of regulatory institutions as well as Memorandum of Understandings (MoUs) between regulators, professional bodies and ‘watchdog’ institutions. To mention a few, these include the PPRA, PSPTB, and Preventions and Combating of Corruption Bureau (PCCB). All along, the institutions have been working together for the sake of ensuring effectiveness, efficiency, integrity, professionalism and corruption-free public procurement undertakings to achieve value for money (Mchopa et al., Citation2014; Mwaiseje & Changalima, Citation2020).

3.2. Public procurement practices and compliance

Public procurement practices are expected to be flawless due to the high stakes involved in terms of expected outcomes, associated risks, and financial implications. The OECD (Citation2013) noted that public procurement constitutes a substantial portion of public spending. Therefore, governments are obligated to carry it out efficiently and uphold high standards to safeguard the public interest. Many governments have issued guidelines and regulations to provide guidance on best practices. These documents primarily aim at guiding public procurement practices concerning transparency, accountability, integrity, competitiveness, ethics, and professionalism.

3.2.1. Governance practices and compliance

In Tanzania, public procurement practices are primarily regulated by the PPA of 2011 (URT, Citation2011) and Amendments of 2016 (URT, Citation2016), along with their respective regulations. However, as procurement involves numerous stakeholders both internal and external to the procuring entities, several cross-cutting laws and regulations set principles for effective procurements. The primary statutes establish the governance framework, providing the institutional structure at the national level (PPRA, PPPD, PPAA) and at the lower level (internal organs in the procuring entity). The PPA of 2011 established and/or customized some internal organs within the procuring entity, including temporary (situational) and permanent ones. These organs include the AO (sect. 36), TB (sect. 31), Procurement Management Unit (PMU) (sect. 37), User Department (sect. 39), Evaluation Committee (sect. 40), Negotiation Committee (reg. 226), and Inspection and Acceptance Committee (reg. 245). As noted by Harper et al. (Citation2016), the creation of regulatory agencies and governance organs positively influences the perception of public sector performance, particularly in procurement. However, the expansion of staff in public procurement should be approached with caution, considering the associated costs related to staff development for the improvement of human resources perspectives in public procurement.

The organs within the institutional framework are expected to function harmoniously and cooperatively without overstepping their jurisdiction, even though some of them are appointed by others. For instance, the AO has the responsibility and authority to appoint members of the TB, Evaluation Committee, Negotiation Committee, and Inspection and Acceptance Committee. The AO is also mandated to establish a PMU and ensure it is appropriately staffed, as outlined in section 36(b). The Evaluation Committee and Negotiation Committee are proposed to report to the PMU, but this does not compromise their autonomy (Mwagike & Changalima, Citation2022). Similarly, the PMU serves as the secretariat to the TB, but the distinct jurisdictions of each organ must be observed and respected at all times. Therefore, for the organs to function effectively, there must be proper coordination, synergy, and cooperation while preserving the independence of functions, as stipulated in section 41 of the PPA (2011).

Among these organs, the PMU is at the center of the ‘functioning web’, driving the proper functioning of other organs and the execution of procurement activities. As mandated by section 38(a), the PMU is responsible for managing all procurement and disposal undertakings except adjudication and the award of contracts. To fulfill this role, the unit must be staffed with procurement experts and other technical specialists, as per section 37(1). However, contrary to these requirements, findings indicate that many PMUs lack adequate staff, including key, administrative, and support personnel, as observed by PPRA (Citation2019, Citation2021). Additionally, some members of the TB lack the necessary knowledge of the principles of procurement and procurement legislation, which are essential tools for their decision-making processes. It is important to note that performance appraisals and other human resource development practices are in place for procurement staff in the public sector (Jaffu & Changalima, Citation2023). At times, procuring entities collaborate to enhance efficiency and effectiveness in public sector procurement undertakings.

Despite the emphasis on the independence of functions among organs, findings indicate persistent elements of conflict of interests, collusion, and evidence of interference between approval organs. The CAG (Citation2019a, Citation2023) found an increasing trend of PMUs overstepping the TB to seek procurement approval, contrary to Regulation 55(2), 163(4), and 185(1) of the PPR (2013). Despite cautions, these bypasses increased in Local Government Authorities (LGAs) by TZS 1,795,610,796 from FY 2015/2016 to FY 2016/2017 and by TZS 6,343,712,232 from FY 2016/17 to FY 2017/18 (235%). This suggests a persistent increase in both the amount and number of authorities engaging in such practices. Similar findings by CAG (Citation2023) indicate instances where PMUs meddled with TB and AO functions due to inadequate rigor in procurement proceedings. In total, 23 LGAs were noted to have procured various items worth TZS 4.34 billion without obtaining approval from their respective Council TBs.

Apart from the independence of functions, legislation calls for transparency in procurement practices, especially in the advertisement of opportunities, tender opening, and publication of awarded contracts. The aim is to provide fair opportunities for potential suppliers to compete and establish a verifiable transaction trail in case of complaints. The PPA (2011) sets preferences for competitive procurement methods, ensuring transparency and fairness. Findings show that in FY 2017/2018, 48 authorities procured goods, services, and works without adhering to transparent and competitive bidding proceedings. The same occurred in FY 2021/2022, where 45 LGAs made procurements worth TZS 7.45 billion without using competitive quotations from bidders (CAG, Citation2023). These procuring entities likely missed opportunities to benefit from the best economical prices, reasonable delivery schedules, and the highest quality from competent bidders.

Surprisingly, transactions hardly qualified for single-source procurement, raising doubts about whether value for money was achieved as expected. The absence of competitive proceedings jeopardized the integrity of the entire tendering and evaluation process. Similarly, the PPRA conducted a special audit at the Rural Energy Agency (REA) (operating under the Ministry of Energy) after being tipped regarding violations of public procurement best practices. Indicators of malpractices were found in the procurement of contractors for executing tenders for the distribution of power transformers, supply and installation of voltage lines, and the connection of customers in un-electrified rural areas. Findings revealed that tenders were floated before the consultant finished preparing the detailed survey and design, and the received tenders were not properly evaluated. These observed transgressions raise doubts about the genuine intentions and focus on value for money.

3.2.2. Emerging procurement practices and performance

The pursuit of perfection and sustainability has placed significant pressure on public procurement to address public needs and align with organizational objectives at every stage of the procurement process. This demand has driven the adoption of strategic procurement techniques, including forward commitment, market analysis, risk management, life cycle assessment, strategic procurement planning and total cost of ownership. Contemporary practices such as outsourcing, back-sourcing, mergers and partnership with key suppliers, and e-procurement are picking up in public procurement (Changalima et al., Citation2023; Ismail & Changalima, Citation2022; Nkunda et al., Citation2023; Shatta et al., Citation2020). The primary purpose of these practices is on controlling procurement total costs of ownership, improve efficiency and productivity of state-controlled business entities as well as minimise embezzlement of public funds through shoddy procurements. As a result, this has led to more innovations and harmonisation of public procurement proceedings in terms of processes, methods and approaches.

Recently in East Africa, public procurement systems have experienced an increase in ‘Government to Government’ (G2G) procurements. The G2G refers to the practices whereby government institutions trade goods, service, and works among them without contracting the private sector. This approach seems to be new but it has been there for a while though not given credit and attention towards improving public procurement undertakings. For example, some development projects have been executed under G2G approach by state-controlled entities such Tanzania Building Agency (TBA) while goods and services were acquired from Medical Stores Department (MSD), and Tanzania Electrical, Mechanical and Electronics Services Agency (TEMESA). In response to the increased transactions, the PPRA had to prepare and issue standard guidelines for modus operandi among public entities with an interest to utilise public procurement opportunities. The achievements under G2G need not be undermined as the government has been able to cut off collusions and bid riggings, improved the efficiency of state-controlled entities, optimised procurement total costs of ownership as well as ensure timely and quality delivery at reasonable prices.

Regardless of the good intentions and achievements, the approach is not immune to flaws as there are evidence of inefficiencies and wrongdoings which defeat the underlying premise of promoting and enforcing G2G. Among others, the CAG (Citation2019b, Citation2023) noted the presence of government entities that have acquired goods and services from other government entities without having a legal contract (agreement). The absence of a contractual agreement could result in disputes in which it could be difficult to take legal action. Also, as per PPA (2016) procurement contracts are supposed to be prepared by PMU, approved by TB and ratified by legal officers prior to execution of procurement. Thus, one would wonder whether the respective organs played their responsibilities diligently to avoid the noted transgressions. Another government agency that has attracted scepticism and grievances from the procuring entities under G2G procurements is TEMESA. Regulation 137 (2) of PPR 2013 as amended in reg. 47 of PPR (2016) gives a mandate to TEMESA to conduct maintenance and repairs of all government owned motor vehicles, equipment and plants. Complaints over TEMESA could not be overlooked which probed PPRA to seek opinions from users in order to determine their authenticity and legitimacy. The audit revealed some weaknesses such as the absence of certificates of approval that were supposed to be issued by TEMESA for verification of whether inspection(s) were carried out after repair and/or maintenance. This was contrary to reg. 137 (2)(d) of PPR (2013) as amended in reg. 47 (2) (c) of PPR (2016). The PMUs in the respective procuring entities did not report to the TB about maintenance and repairs of motor vehicles executed by TEMESA which is contrary to reg. 166 (7) of PPR (2013). Thus, the complaints over repairs and maintenance seem to be a Pandora Box as both parties have their stakes in resolving the puzzle.

3.2.3. Professionalism in public procurement

Unlike the previous legislation, the PPA (2011) and Amendments (2016) have emphasised the need for professionalism in the execution and management of procurement operations at the procuring entities. The AO and TB have been given a provision to request any technical advice or professional from any appropriate body or person prior to making decisions relating to procurement activities. Purposely, it has been done so in order to get proper guidance towards decision making since they might not be conversant with procurement practices. The upkeep of professionalism in public as well as private procurement operations is primarily the responsibility of the PSPTB. The Board has put standards and codes of conduct for procurement professionals to guide their moral conduct and compliance with professional etiquette. Hence, the AO and TB have the discretion of seeking professional advice from the PSPTB that seems to be decisive or otherwise toward decision making.

The PMU is the engine of procurement in the procuring entities, PPA (2011) requires the Unit to be headed by a person who is registered by the procurement professional body and with appropriate experience, academic and professional qualifications in procurement. This requirement lays the foundation for ensuring compliance with professional practices and observing professional protocols (Mrope et al., Citation2017a; Matto et al., Citation2023; Mwakibinga & Buvik, Citation2013). Procurement experts are expected to refrain from fraud, corruption, conflict of interests, collusion, bid tampering, and breach of confidentiality, as expressed in sections 83 and 104 of the PPA (2011). Violating these provisions is considered an offense, subject to punishment and penalties as stipulated in section 104. Despite such provisions, the quest for excellence has been marred by unprofessional and unethical conduct by procurement experts. Matto (Citation2017b) highlighted instances of shoddy procurements, including dubious payments made to contractors for non-existing and inferior works totaling TZS 1,926.6 million over three years. Additionally, 25 LGAs made payments for goods and services worth TZS 744.12 million that were never delivered or provided. This raises questions about the actions and advice of procurement officers.

Public procurement practices have been tainted by elements of fraud and corruption, which are highly unprofessional and unethical. The PPRA (Citation2019) identified 131 procurement contracts with higher red flags of corruption in either one of its phases or in their entirety. Another 12 procurement contracts worth TZS 25.8 billion had a high red flag score in the overall assessment, implemented by various entities, including the Ministry of Water and Irrigation, Tanzania Railway Corporation, Tanzania Ports Authority, and Tanzania Bureau of Standards. The PPRA referred these cases to the Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau (PCCB) for further investigations and prosecutions. The CAG (Citation2019b, Citation2023) observed the presence of procurements without substantive contracts. Contracts are supposed to be prepared by the PMU and then submitted to the Legal Officer for vetting (if the value does not exceed TZS 1 billion) or the Attorney General for ratification (if the value exceeds TZS 1 billion). The presence of procurements without substantive contracts undermines the professionalism of the respective procurement officers.

Procurement from unapproved suppliers is another unprofessional practice observed in public procurement, contrary to regulation 131(4)(b) of the PPR 2013, which requires the list of potential suppliers to be approved by the TB. The PMU is required to conduct sourcing (market survey and intelligence) and communicate their recommendations to the TB for approval before executing the procurement process, as stipulated in regulation 163(3) and (4). In 2017/2018, goods and services worth TZS 923,836,408 were procured from unapproved suppliers. Such unprofessional practices may hinder the achievement of value for money, and the procured goods and services might not meet the pre-established standards and specifications.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

An efficient public procurement system plays a crucial role in stimulating the economy by facilitating the delivery of improved economic and social infrastructure, as well as ensuring the timely and quality provision of goods and services to the public. Over the years, reforms have demonstrated that public procurement can stimulate competitiveness and foster industry growth in the private sector, creating a substantial market base given the government’s role as a significant spender. Arguably, public procurement is where government money is concentrated. Therefore, it is imperative to have prudent laws, regulations, policies, and procedures in place to ensure effective public spending and establish trust in the public domain, with a focus on achieving value for money. These efforts should also be directed towards combating corrupt practices by promoting good governance, fostering honest practices, and instilling ethical principles among public procurement practitioners. While laws and regulations addressing issues such as corruption, fraud, and conflicts of interest are already in place, it is essential to emphasize continuous efforts. The professional board has taken measures against individuals by deregistering them, and tenderers are blacklisted by the relevant authority when exposed for corrupt practices. This study advocates for ongoing efforts to maintain a public procurement process free from corrupt practices and other malpractices.

Nevertheless, the long-overdue public procurement policy has resulted in an absence of clear policy guidance, leading to numerous reforms and directives. Additionally, procurement practices at lower local government levels still face challenges due to the lack of professionals and clear guidelines tailored to their conditions. The study recommends the harmonization of procurement rules and guidelines to avoid dilemmas, as seen in the case of force account procurements (Macharia et al., Citation2023; Mchopa, Citation2020). There are concerns about the accountability of public entities involved in G2G procurements due to sloppiness and complacency. Therefore, professional and best practices should be upheld in G2G procurement, similar to the approach taken in procurement from private entities. This, in turn, will foster the good intentions of promoting G2G and deliver the best procurement outcomes in terms of quality and cost (value for money).

5. Limitations and avenues for future research

It is worth acknowledging that SLR studies are exposed to some limitations (Nguyen et al., Citation2020; Alatawi et al., Citation2023). This study exclusively focuses on journal articles from Scopus and Google Scholar, excluding other publication forms such as book reviews and conference proceedings. Therefore, future SLR studies may consider including various forms of publications to obtain a broader range of literature. Additionally, the current study only includes articles in the English language, given that it is the conversant language of the authors. Thus, articles which were not in English were excluded potentially leading to bias. This issue could be taken care by future research on this research domain concentrating on SLR studies. Based on the contribution of the study, this SLR study mainly focused on the literature in the context of public procurement of Tanzania. While noting this limitation, future studies may extend the scope by including literature from other countries or inclusion of private sector procurement. This approach may provide a clearer and wider picture of procurement practices and compliance issues from a diverse range of sources. Lastly, the study acknowledges existence of quantitative techniques for conducting reviews such as the application of bibliometric analysis (Donthu et al., Citation2021; Lim & Kumar, Citation2024). Given that the current study predominantly focuses on SLR, future research may consider employing bibliometric analysis on publications related to procurement practices and other procurement domains within the context of public procurement in Tanzania. Such studies could offer additional evidence on trends, influential authors, articles and journal sources, themes, and commonly used keywords in the realm of public procurement research in the Tanzanian context.

Author contributions

Alban D. Mchopa was involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the results, the drafting of the paper.

Ismail Abdi Changalima was involved in revising the manuscript and review of literature.

Gabriel R. Sulle was involved in the conception and design.

Rahim M. Msofe was involved in the drafting of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

No dataset was involved in this study.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alban D. Mchopa

Alban D. Mchopa is a Senior Lecturer at Moshi Co-operative University, Tanzania working in the Department Procurement and Supply Chain Management. He is a certified procurement and supplies professional holding a PhD, Master of Science in Procurement and Supply Chain Management, and Bachelor Degree in Procurement and Supply Management. His areas of interest and expertise in research include public procurement; procurement reforms; electronic procurement; procurement and supply audit; and donor funded procurement.

Ismail Abdi Changalima

Ismail Abdi Changalima is a Lecturer at the Department of Business Administration and Management in the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. He holds a PhD from the University of Dodoma, a Master of Science in Procurement and Supply Chain Management from Mzumbe University, and a Bachelor of Business Administration in Procurement and Logistics Management, also from Mzumbe University. His research interests include various facets of this field, including procurement strategies, supplier management, sustainable procurement, supply chain management, and business management.

Gabriel R. Sulle

Gabriel R. Sulle is an Assistant Lecturer at Moshi Co-operative University, Tanzania working in the Department Procurement and Supply Chain Management. He holds a Master of Arts and Bachelor of Arts in Procurement and Supply Management. His areas of interest and expertise in research include public procurement; electronic procurement, procurement reforms and donor funded procurement.

Rahim M. Msofe

Rahim M. Msofe is an Assistant Lecturer at Moshi Co-operative University, Tanzania working in the Department Procurement and Supply Chain Management. He is a certified procurement and supplies professional holding a Master of Arts and Bachelor of Arts in Procurement and Supply Management. His areas of interest and expertise include public procurement; strategic procurement; production and operations management; logistics and supply chain management.

References

- Alatawi, I. A., Ntim, C. G., Zras, A., & Elmagrhi, M. H. (2023). CSR, financial and non-financial performance in the tourism sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 89, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102734

- Alhossini, M. A., Ntim, C. G., & Zalata, A. M. (2021). Corporate board committees and corporate outcomes: An international systematic literature review and agenda for future research. The International Journal of Accounting, 56(01), 2150001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1094406021500013

- Basheka, B. (2017). Public procurement reforms in Africa: A tool for effective governance of the public sector and poverty reduction. In Khi V. Thai (Ed.), International handbook of public procurement (pp. 131–14). Routledge.

- CAG. (2019a). Annual general report on the audit of the financial statements of local government authorities for the financial year ended 30th June 2018. United Republic of Tanzania, National Audit Office.

- CAG. (2019b). Annual general report on the audit of the financial statements of the central government in the financial year ended 30th June 2018. United Republic of Tanzania, National Audit Office.

- CAG. (2019c). Annual general report on the audit of the development projects in the financial year ended 30th June 2018. United Republic of Tanzania, National Audit Office.

- CAG. (2023). Annual general report on the audit of financial statements of local government authorities for the financial year ended 30th June 2022. United Republic of Tanzania, National Audit Office.

- Changalima, I. A., & Mdee, A. E. (2023). Procurement skills and procurement performance in public organizations: The mediating role of procurement planning. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2163562. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2163562

- Changalima, I. A., Israel, B., Amani, D., Panga, F. P., Mwaiseje, S. S., Mchopa, A. D., Kazungu, I., & Ismail, I. J. (2023). Do internet marketing capabilities interact with the effect of procedural capabilities for public procurement participation on SMEs’ sales performance? Journal of Public Procurement, 23(3–4), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-01-2023-0001

- Changalima, I. A., Mchopa, A. D., & Ismail, I. J. (2022). Supplier development and public procurement performance: Does contract management difficulty matter? Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2108224. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2108224

- Djankov, S., Saliola, F., & Islam, A. (2016). Is public procurement a rich country’s policy? https://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/public-procurement-rich-country-s-policy

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

- Harper, L. E., Ramirez, A. C. C., & Ayala, J. E. M. (2016). Elements of public procurement reform and their effect on the public sector in lac. Journal of Public Procurement, 16(3), 347–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-16-03-2016-B005

- Hoekman, B., & Sanfilippo, M. (2018). Firm performance and participation in public procurement: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Brief 43421. International Growth Centre – Uganda. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Hoekman-and-Samfilippo-2018-policy-brief.pdf

- Ibrahim, A. E. A., Hussainey, K., Nawaz, T., Ntim, C., & Elamer, A. (2022). A systematic literature review on risk disclosure research: State-of-the-art and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 82, 102217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102217

- Ismail, I. J., & Changalima, I. A. (2022). Thank you for sharing! Unravelling the perceived usefulness of word of mouth in public procurement for small and medium enterprises. Management Matters, 19(2), 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/MANM-01-2022-0005

- Israel, B., & Kazungu, I. (2019). The role of public procurement in enhancing growth of small and medium sized- enterprises: Experience from Mbeya Tanzania. Journal of Business Management and Economic Research, 3(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.29226/TR1001.2019.99

- Jaffu, R., & Changalima, I. A. (2023). Human resource development practices and procurement effectiveness: Implications from public procurement professionals in Tanzania. European Journal of Management Studies, 28(2), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMS-04-2022-0030

- Knutsson, H., & Thomasson, A. (2014). Innovation in the public procurement process: A study of the creation of innovation-friendly public procurement. Public Management Review, 16(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.806574

- Komakech, R. A. (2016). Public procurement in developing countries: Objectives, principles and required professional skills. Public Policy and Administration Research, 6(8), 20–29.

- Leech, N., & Onwuegbuzie, A. (2008). Qualitative data analysis: A compendium of techniques for school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.587

- Lim, W. M., & Kumar, S. (2024). Guidelines for interpreting the results of bibliometric analysis: A sensemaking approach. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43(2), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22229

- Lu, Y., Ntim, C. G., Zhang, Q., & Li, P. (2022). Board of directors’ attributes and corporate outcomes: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 84, 102424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102424

- Macharia, T. E., Banzi, A. L., & Changalima, I. A. (2023). Effectiveness of the force account approach in Tanzanian local government authorities: Do management support and staff competence matter? Management & Economics Research Journal, 5(1), 66–82. https://doi.org/10.48100/merj.2023.301

- Maliganya, E. (2015). The next age of public procurement reforms in Tanzania: Looking for the best value for money. The George Washington University, Law School. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2709842

- Matto, M. (2017a). Mapping public procurement reforms in Tanzania: Compliance, challenges and prospects. European Journal of Business and Management, 9(12), 175–182.

- Matto, M. (2017b). Analysis of factors contributing to poor performance of procurement functions in local government authorities: Empirical evidence from audit reports. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(3), 41–52.

- Matto, M. C., Ame, A. M., & Nsimbila, P. M. (2023). Measuring compliance in public procurement: The case of Tanzania. International Journal of Procurement Management, 18(2), 188–212. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPM.2023.133128

- Mchopa, A. D. (2020). Applicability of force account approach in procurement of works in Tanzania. Journal of International Trade, Logistics and Law, 6(2), 137–143.

- Mchopa, A. D., Njau, E., Ruoja, C., Huka, H., & Panga, F. P. (2014). The achievement of value for money in Tanzania public procurement: A non-monetary assessment approach. International Journal of Management Sciences, 3(7), 524–533.

- Mrope, N. P., Namusonge, G. S., & Iravo, M. A. (2017a). Does compliance with rules ensure better performance? An assessment of the effect of compliance with procurement legal and regulatory framework on performance of public procurement in Tanzania. European Journal of Logistics, Purchasing and Supply Chain Management, 5(1), 40–50.

- Mrope, N. P., Namusonge, G. S., & Iravo, M. A. (2017b). Private sector involvement in public procurement opportunities: An assessment of the extent and effect in Tanzanian public entities. European Journal of Business and Management, 9(8), 105–112.

- Mwagike, L. R., & Changalima, I. A. (2022). Procurement professionals’ perceptions of skills and attributes of procurement negotiators: A cross-sectional survey in Tanzania. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 35(1), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-12-2020-0331

- Mwaiseje, S. S., & Changalima, I. A. (2020). Individual factors and value for money achievement in public procurement: A survey of selected government ministries in Dodoma Tanzania. East African Journal of Social and Applied Sciences (EAJ-SAS), 2(2), 50–58.

- Mwakibinga, F. A., & Buvik, A. (2013). An empirical analysis of coercive means of enforcing compliance in public procurement. Journal of Public Procurement, 13(2), 243–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-13-02-2013-B004

- Nguyen, T. H. H., Ntim, C. G., & Malagila, J. K. (2020). Women on corporate boards and corporate financial and non-financial performance: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 71, 101554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101554

- Nijboer, K., Senden, S., & Telgen, J. (2017). Cross-country learning in public procurement: An exploratory study. Journal of Public Procurement, 17(4), 449–482. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-17-04-2017-B001

- Nkinga, N. (2003). Public procurement reform- The Tanzanian experience [Paper presentation]. World Bank Regional Workshop on Procurement Reforms and Public Procurement for the English– Speaking African Countries, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.

- Nkunda, R. M., Kazungu, I., & Changalima, I. A. (2023). Collaborative procurement practices in public organizations: A review of forms, benefits and challenges. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 20(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v20i1.3

- Ntangeki, G. G., Changalima, I. A., Justus, S. N., & Kawishe, D. C. (2023). Do transparency and accountability enhance regulatory compliance in public procurement? Evidence from Tanzania. African Business Management Journal, 1(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.58548/2023abmj11.2940

- Onwuegbuzie, A., Leech, N., & Collins, K. (2012). Qualitative analysis techniques for the review of the literature. The Qualitative Report, 17(1), 1–28.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Develop (OECD). (2009). Principles for integrity in public procurement. https://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/48994520.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013). Implementing the OECD principles for integrity in public procurement: Progress since 2008. OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201385-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). “Size of public procurement” in Government at a Glance 2017. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/gov_glance-2017-59-en.pdf?expires=1578578902&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=87CFE1322B5DA4B5FB42762B1509EEC4

- Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2020). Government spending. https://ourworldindata.org/government-spending

- Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA). (2019). Annual performance evaluation report for the financial year 2018/19. PPRA.

- Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA). (2021). Annual performance evaluation report for the financial year 2020/21. PPRA.

- Sama, H. K. (2022). Transparency in competitive tendering: The dominancy of bounded rationality. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2147048. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2147048

- Shatta, D. N., Shayo, F. A., Mchopa, A. D., & Layaa, J. N. (2020). The influence of relative advantage towards e-procurement adoption model in developing countries: Tanzania context. European Scientific Journal ESJ, 16(28), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2020.v16n28p130

- Talebi, A., & Rezania, D. (2020). Governance of projects in public procurement of innovation: A multi-level perspective. Journal of Public Procurement, 20(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-01-2019-0005

- Telgen, J., Van der Krift, J., & Wake, A. (2016). Public procurement reform: Assessing interventions aimed at improving transparency. DFID. 42pp. https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Public-Procurement-Reform.pdf

- The United Republic of Tanzania (URT). (2011). The Public Procurement Act. The Government Printers.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT). (2013). Public Procurement Regulations of 2013. The Government Printers.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT). (2016). Public Procurement Act Amendments of 2016. The Government Printers. The Government Printers.

- World Bank. (2012). Why reform public procurement. https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/MNA/Why_Reform_ Public_Procurement_English.pdf

- World Bank. (2016). Benchmarking public procurement: Assessing public procurement regulatory systems in 180 economies. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2018). Why modern, fair and open public procurement systems matter for the private sector in developing countries. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/05/16/why-modern-fair-and-open-public-procurement-systems-matter-for-developing-countries