Abstract

This study examines the relationships between the components of ethical decision-making and the factors that contribute to the ethical decision-making of professional accountants. Survey data from 309 professional accountants was analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The study found positive relationships among moral recognition, moral judgment, and moral intent. Moral judgment mediates the relationship between moral recognition and moral intent in ethical decision-making. The study also found that laws and professional codes, moral philosophies, intrinsic religious orientation, and social responsibility influenced ethical decision-making. However, peer group pressure did not predict moral judgment among professional accountants. This study provides implications for considering the mediating role of moral judgment in the ethical decision-making process. To improve ethical decision-making among professional accountants, understanding the influences and relationships of other factors is crucial in an ethical setting.

Subjects:

1. Introduction

Professional accountants play a significant role in protecting the public interest. Integral to their role is the need for a comprehensive set of professional competencies, of which ethical competency is the principal dimension. Mintz and Morris (Citation2017) emphasize the importance of ethical competency for professional accountants because their actions and decisions have far-reaching consequences that extend to society. As reports show, accountants face various ethical issues, such as conflicts of interest, insider trading, lapses in objectivity and independence, and tax fraud and evasion (Dunn & Sainty, Citation2019; Mintz & Morris, Citation2017; Pflugrath et al., Citation2007). These ethical challenges often arise when accountants prioritize their clients’ or personal interests at the expense of the public interest (Mintz & Morris, Citation2017).

The consequences of such prioritization fundamentally dishonor the profession and lead to waiving the public interest (Flory et al., Citation1992). This was evidenced when the corporate scandals of prominent companies such as Enron, WorldCom, Qwest, Global Crossing, and Tyco came to the forefront (Johari et al., Citation2017; Mintz & Morris, Citation2017; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh, Citation2019). These corporate collapses were largely attributed to alleged accounting irregularities and ethical failures (Pflugrath et al., Citation2007). Consequently, the significance of business ethics, particularly in the accounting profession, received substantial attention.

Buchan (Citation2005) emphasized the importance of accountants’ level of ethical awareness and orientation in influencing their ethical sensitivity, which pertains to recognizing dilemmas as ethical issues. Similarly, Hirth-Goebel and Weißenberger (Citation2019) and Mintz and Morris (Citation2017) indicated that accountants with strong ethical sensitivity are better equipped, more sensitive to ethical dilemmas, and able to manage ethical issues. This requires accountants to apply ethical decision-making (EDM) approaches (Dunn & Sainty, Citation2019; Mintz & Morris, Citation2017).

Theoretical perspectives on EDM draw from moral philosophy (Mintz & Morris, Citation2017; Schwartz, Citation2015). Hunt and Vitell (Citation2006) mentioned that individuals consider employing a set of philosophical assumptions that serve as a foundation for EDM. In this case, normative ethical theories play a fundamental role in establishing a framework for ethical decisions and evaluating an individual’s response to ethical dilemmas (Barnett, Citation2001; Schwartz, Citation2015; Singhapakdi et al., Citation2001). The response to ethical dilemmas draws from normative ethical theories of deontology and utilitarianism (Brady, Citation1985; Brady & Dunn, Citation1995; Hunt & Vitell, Citation2006).

Deontology emphasizes adherence to moral principles, regardless of consequences, while utilitarianism focuses on the consequences of actions as the primary determinant of moral rightness or wrongness (Brady & Dunn, Citation1995; Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986). These theories offer foundational principles and perspectives on what constitutes morally right conduct that can guide the resolution of ethical dilemmas. Brady (Citation1985) and Hunt and Vitell (Citation1986) advocate the application of deontology and utilitarianism ethical theories in the EDM process. Together, these theoretical perspectives provide a comprehensive framework to evaluate the dynamics of EDM.

Kohlberg’s (Citation1976) six stages of cognitive moral development theory elucidate how individuals internalize moral standards and apply them to address ethical dilemmas in their moral judgment. However, Rest (Citation1984) argued that Kohlberg’s theory does not encompass the entirety of morality. Rest claimed that moral development is more multifaceted than mere moral judgment. In response to this, Rest developed a four-component model of EDM, and in each component, unique cognitions and affects are involved in contributing to moral behavior. The four components are moral recognition (MRC), moral judgment (MJD), moral intent (MIT), and moral behavior. Schwartz (Citation2015) claimed that Rest’s (Citation1984) four-component model stands as the most dominant and frequently referenced EDM framework in the literature and serves as the foundation upon which many other models were built.

Although ethical issues require a well-defined EDM approach, arriving at ethical decisions is not straightforward. Several factors can affect EDM (Casali & Perano, Citation2021; Dunn & Sainty, Citation2019; Schwartz, Citation2015). Numerous researchers have attempted to examine the factors influencing EDM (Hirth-Goebel & Weißenberger, Citation2019; Kportorgbi et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh, Citation2019; Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022). The bibliographic analysis conducted by Owusu and Korankye (Citation2023) highlighted the considerable number of studies dedicated to exploring EDM in the accounting profession. Casali and Perano (Citation2021) also identified forty-two potentially influencing factors of EDM by resynthesizing the works of others. This underscores the complex nature of EDM and necessitates considering appropriate approaches to address ethical dilemmas.

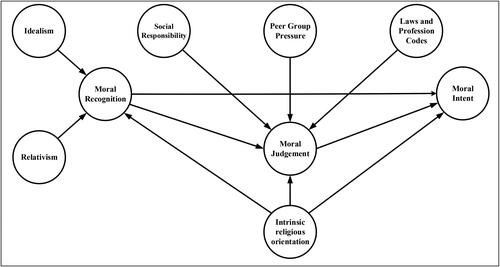

Dunn and Sainty (Citation2019) have developed a five-factor model that influences EDM among accountants: codes of conduct, philosophical orientation, religious orientation, culturally derived values, and moral maturity. The model indicated how these five factors positively and negatively affect accountants’ EDM. This study has adapted the model and incorporated the factors of laws and professional codes (LPC), moral philosophies – idealism (IDA) and relativism (RLV), intrinsic religious orientation (IRO), social responsibility (SOR), and peer group pressure (PGP). These factors serve as exogenous constructs, influencing the components of EDM based on Rest’s (Citation1984) model. This ensures a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing EDM in the accounting profession by considering the evolving dynamics and diverse influences that shape ethical behavior.

In the extant literature, inconsistencies have been noted in the components of EDM and among the factors. The inconsistencies across empirical studies are traced to the methodology and model used. Schwartz (Citation2015) supports this and suggests that the inconsistency could stem from research methodologies applied, relying on self-reported data, models used, and the variety and quality of measurement tools used.

The inconsistencies highlight significant gaps in the literature. Firstly, in addition to empirical studies examining the direct relationships between the components of Rest’s (Citation1984) model, the mediating role of MJD in the relationships remains somewhat unexplored (Andersch et al., Citation2019; Hirth-Goebel & Weißenberger, Citation2019; Rottig et al., Citation2011; Yang & Wu, Citation2009). Secondly, a common approach in several studies involves using a single indicator to measure the components of Rest’s (Citation1984) model (e.g. Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh, Citation2019; Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022). However, Moores et al. (Citation2018) recommend incorporating multiple items to measure and explain the variance of these components.

Thirdly, the ease and accessibility of using student samples have led to a significant number of studies using this strategy, potentially compromising the generalizability of findings to professional contexts (e.g. Pflugrath et al., Citation2007; Valentine & Bateman, Citation2011). Finally, several studies commonly employ hierarchical regression to analyze the components of EDM at different stages (e.g. Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh, Citation2019; Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022). However, this method may lack simultaneous analysis of the constructs, a gap that could be addressed through structural equation modeling (Hair et al., Citation2022). Generally, these gaps underscore the need for research to deepen our understanding of the EDM process.

This study aims to examine whether MJD mediates the relationship between MRC and MIT based on different ethical dilemmas. The study also aims to examine the influence of laws and professional codes, idealism, relativism, intrinsic religious orientation, social responsibility, and peer group pressure on professional accountants’ EDM components based on different ethical dilemmas. This study has theoretical and practical implications as it gives insights into how professional accountants can consider different factors to support their EDM.

First, the study contributes to the EDM literature. It broadens the scope of EDM by providing the mediating role MJD plays in the relationships between MRC and MIT. This relationship empirically tested using accounting vignettes. Second, the influences of six factors were examined based on normative ethical theories. Third, empirical research examines the EDM of professional accountants in developing countries, particularly Ethiopia, which is underrepresented (Owusu & Korankye, Citation2023). This highlights the importance of EDM to comprehend and examine in different contexts.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows: The next section presents the background, followed by a theoretical and empirical literature review with hypothesis development. It then presents the research design, and empirical results and discussions. Finally, it presents a summary and conclusions.

2. Background

According to Mihret et al. (Citation2012), a remarkable advancement of Ethiopia’s accounting practices occurred in 1960 with the enactment of the Commercial Code, laying the groundwork as a governing law for financial reporting and external auditing. Before the Code underwent amendments in 2021, the country strengthened its attempts to scrutinize the accounting profession in 2014 by establishing the Accounting and Auditing Board of Ethiopia (AABE) (Regulation No.332/2014, Citation2015). AABE is the first statutory body established to undertake regulatory responsibilities in financial reporting. Accordingly, Ethiopia has committed to fostering accounting practices through these legislative advancements.

AABE aims to safeguard the public interest by regulating Ethiopia’s accounting and auditing profession. In line with this objective, the board is entrusted with a range of responsibilities, including the issuance of a nationally recognized professional accounting qualification, the development and enforcement of accounting and auditing standards, and the development of codes of conduct and ethics in line with the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC).

Proclamation No. 847/2014 (Citation2014) outlines AABE’s power and duties. AABE is responsible for registering and certifying individual professionals and firms providing public accounting services in the country. The board actively monitors and reviews the work of professionals, firms, and reporting entities to ensure compliance with established standards. Additionally, AABE is mandated to provide and facilitate continuous professional development programs for accounting professionals. Enforcement of financial reporting laws and implementation of disciplinary measures, including revoking certifications against non-compliance, are also within the power and duties of AABE.

Before the establishment of AABE, the regional audit bureaus in the respective regions oversaw the certification of professional accountants and auditors. Eventually, AABE’s establishment allows professional accountants and auditors to obtain certification directly from the board and convert their regional licenses to national certification. Despite this centralization effort, certain regions continued their independent certification and license renewal procedures, leading to a potential conflict of interest between the two bodies. These dual roles constrained the full exercise of the board’s powers and duties. This reflects the complexity of regulatory oversight for accounting professionals and opens the door to questioning whether they adhere to their professional responsibilities in fostering public interest. This study thus attempts to examine the EDM processes of professional accountants in the context of Ethiopia.

3. Theoretical literature review

When applied to accounting, ethical behavior represents the compulsory character of each professional accountant. This behavior raises the normative question of whether accountants’ behavior is good or bad (Mintz & Morris, Citation2017), which means that accountants’ behavior is ethically justified. Several authors have tried to explore ethical behaviors based on normative ethical theories (Baker, Citation1999; Brady & Dunn, Citation1995; Hunt & Vitell, Citation2006; Schwartz, Citation2015; Trevino et al., Citation1998; Zaikauskaite et al., Citation2020). Even though there are different normative ethical theories, several authors claim that ethical behavior is evaluated based on deontological and utilitarian ethical theories (Brady, Citation1985; Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986).

According to Brady (Citation1985), deontological ethical theory emphasizes moral rules and duties. This theory considers an action ethically desirable if it follows a moral law, principle, or rule. Brady and Dunn (Citation1995) express deontological principles like justice, rights, and duties, which fit into a moralistic climate in which things are right and wrong, permissible or punishable. According to Mintz and Morris (Citation2017), Immanuel Kant is the leading proponent of the deontological position. Brady (Citation1985) also highlighted Kant’s position, asserting that ethical behavior should be unconditional. In other words, it ought to remain unaffected by individual preferences or desires.

Utilitarianism ethical theory relates moral evaluations to the consequences of actions (Baker, Citation1999). It is often called teleological, consequentialist, or purposive (Brady, Citation1985). This theory determines an action, whether right or wrong, based on its consequences (Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986). Typically, it aims to maximize benefits, in which an act is ethical as long as it brings benefits. Thus, the ethical evaluation of utilitarianism rests on the relative benefits of the alternative actions perceived.

Advocates for these theories posit that they are compatible and complementary (Brady, Citation1985; Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986). In the case of accounting, Baker (Citation1999) claimed that a single ethical theory could not adequately guide an accounting professional on every ethical issue. Instead, EDM is posited as a synthesis function of the individual’s deontological and utilitarian evaluations (Brady, Citation1985; Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986).

In addition to the normative ethical theories, the cognitive processes of individuals are indicated as apparent in the EDM frameworks. In this sphere, Kohlberg’s (Citation1976) work on cognitive moral development is commonly cited to assess an individual’s moral development. However, Rest (Citation1984) claimed four inner cognitive-affective components generate moral behavior: an individual first recognize an ethical dilemma (MRC), makes a moral judgment (MJD), moves on to intent (MIT), and finally finds the courage to act.

The first component (MRC) recognizes and interprets a situation’s potential ethical implications and understands that a decision has moral significance. MJD determines which action is more ethically justifiable when a person is aware of different lines of action and which alternative is right (Rest, Citation1984). MIT is concerned with moral motivation to act based on the MJD (Narvaez & Rest, Citation1995; Rest, Citation1984). According to Rest (Citation1984), moral behavior involves the integration of moral values into one’s personality and consistently acting under those values. Rest emphasized the need for a balanced combination of these components to make ethical decisions; any weakness can cause moral failure, and all four components predict moral behavior.

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

4.1. Ethical decision-making

Numerous studies have examined the EDM framework outlined by Rest (Citation1984). These studies have significantly contributed to the understanding of moral recognition, moral judgment, and moral intent (Johari et al., Citation2017; Kportorgbi et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Latan et al., Citation2019; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh, Citation2019). However, it is noteworthy that the fourth component, actual moral behavior, has not been extensively studied due to the inherent challenges of accurately measuring behavioral responses in real-life ethical dilemmas (Moores et al., Citation2018; Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022).

The studies of Johari et al. (Citation2017), Oboh (Citation2019), and Yang and Wu (Citation2009) examined the processes of MRC in connection with morally relevant situations. These studies suggested that understanding ethical dilemmas influences MRC, which is positively related to MJD. In connection with MJD and MIT, studies found consistent findings and asserted that MJD was positively related to MIT (Latan et al., Citation2019; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022; Tariq et al., Citation2019). Although several empirical studies found significant and positive relationships among the components of EDM, some studies found inconsistent results with the relationships between MRC and MJD (e.g. Barnett, Citation2001; Latan et al., Citation2019; Moores et al., Citation2018).

In addition to the logical sequence implied, the components mutually influence each other through feedback and feedforward loops (Narvaez & Rest, Citation1995; Rest, Citation1984). In essence, MJD can be considered a mediator that connects awareness of the ethical implications (MRC) to the subsequent intention to act under moral values (MIT). Some empirical studies found that other constructs and MRC related to MIT through the mediation of MJD (e.g. Andersch et al., Citation2019; Johari et al., Citation2017; Rottig et al., Citation2011; Tariq et al., Citation2019; Yang & Wu, Citation2009). However, the extant literature concerning the relationship between MRC and MIT remains relatively unexplored. Therefore, examining the relationship that MJD mediates holds enormous promise for advancing the EDM framework. Based on the preceding discussions, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a. There is a significantly positive relationship between moral recognition and moral judgment.

H1b. There is a significantly positive relationship between moral judgment and moral intent.

H1c. There is a significantly positive relationship between moral recognition and moral intent.

H1d. Moral judgment has a significantly positive mediating role in the relationship between moral recognition and moral intent.

4.2. Factors of ethical decision-making

According to Dunn and Sainty (Citation2019), codes of conduct establish guidelines for acceptable and unacceptable behavior by accountants. Similarly, most individuals look to the law for direction when faced with ethical dilemmas. In these regards, Victor and Cullen (Citation1987) introduced a construct encompassing laws and professional codes (LPC) in the ethical climate dimension. This construct implies that legal rules and professional codes may influence individuals’ EDM and provide clear and specific guidelines for acceptable and unacceptable behaviors (Trevino et al., Citation1998). This is particularly relevant in accounting, which is heavily regulated by laws, regulations, standards, and codes of conduct. This is also in line with deontological ethics theory (Brady, Citation1985) and supports Kohlberg’s (Citation1976) stage four ‘law and order’ orientation.

Several empirical studies found a positive relationship between professional codes of conduct and EDM in the accounting profession. Pflugrath et al. (Citation2007) found that codes of conduct positively influenced auditors’ ethical judgment. Modarres and Rafiee (Citation2011) also found that accounting students’ ethical standards were influenced by understanding professional codes of conduct and being informed of codes, which helped maintain high ethical standards. The studies of Fatemi et al. (Citation2020) found that enforcing codes of conduct was positively related to ethical behaviors. However, some empirical studies found inconsistent results. For instance, Barnett and Vaicys (Citation2000) and Liu (Citation2020) found the insignificant influence of LPC on moral behavior. Besides, empirical studies have predominantly focused on codes of conduct, which overlook the role of laws in shaping accountants’ ethical behavior. Therefore, examining the intertwined factors of LPC is imperative. Based on these discussions, the following hypothesis is developed:

H2. Laws and professional codes has a significantly positive influence on moral judgment.

According to Forsyth (Citation1992), individuals’ moral philosophies are evident in their moral beliefs, attitudes, and values, which influence their moral behaviors. The author also noted that personal moral philosophies are often compared based on idealism and relativism. These two dimensions of moral philosophy help to evaluate ethical behavior (Shukla & Srivastava, Citation2016). Dunn and Sainty (Citation2019) also claimed that an adopted philosophical orientation in accounting influences accountants’ EDM. IDA refers to the extent to which individuals believe that engaging in moral behavior will inevitably result in positive consequences. RLV represents the extent to which an individual rejects the notion that moral decisions should always align with universal moral principles (Zaikauskaite et al., Citation2020). The high idealism stance aligns with the utilitarian ethical theory, wherein action is deemed right or wrong contingent upon consequences. Low RLV upheld the deontological theory, which uses rules to distinguish right from wrong (Zaikauskaite et al., Citation2020).

Several studies have sought to investigate the influence of IDA and RLV on EDM. Johari et al. (Citation2017) found that auditors with IDA orientation showed desirable EDM processes, whereas those with RLV exhibited unfavorable EDM. Other empirical studies also found similar results (Oboh, Citation2019; Shukla & Srivastava, Citation2016; Singhapakdi et al., Citation1999; Valentine & Bateman, Citation2011; Zaikauskaite et al., Citation2020). Musbah et al. (Citation2016) indicated that moral philosophy significantly influences how individuals perceive ethically challenging situations. However, the study’s findings on IDA and RLV were inconsistent across different ethical vignettes. This is also evidenced in Oboh’s (Citation2019) study. Despite inconsistent results reported in some studies, empirical findings support the idea that individuals with higher levels of IDA tend to perceive ethical situations more favorably, whereas RLV demonstrates a notably negative relationship. These relationships suggest the following hypotheses:

H3a. Moral idealism has a significantly positive influence on moral recognition.

H3b. Moral relativism has a significantly negative influence on moral recognition.

Religious beliefs and values often provide a moral framework that guides the behaviors of individuals (Keller et al., Citation2007; Kportorgbi et al., Citation2022; Singhapakdi et al., Citation2013; Tariq et al., Citation2019; Vitell et al., Citation2009). Its ethical theory aligns with deontological ethics; hence, ethical decisions based on religious perspectives tend to form rule-based evaluations (Hunt & Vitell, Citation2006; Shariff, Citation2015; Tariq et al., Citation2019; Vitell et al., Citation2009). Dunn and Sainty (Citation2019) proposed that the strength of an individual’s religious beliefs, level of understanding, and religious practices might influence EDM. In this case, individuals with IRO deeply integrate their faith into their lives. In contrast, extrinsic individuals do not approach their faith sincerely (Hunt & Vitell, Citation2006).

Several studies have explored the effects of religion on EDM. Keller et al. (Citation2007) and Singhapakdi et al. (999) found that religious values provide a solid basis for MJD. The study by Kportorgbi et al. (Citation2022) found that intrapersonal religious orientation was positively related to individual EDM, while interpersonal religious orientation adversely affected the EDM of tax accountants. The study conducted by Tariq et al. (Citation2019) found that intrinsic religiosity directly affects MIT and exerts an indirect effect through MJD. The study of Sulaiman et al. (Citation2022) and Shariff (Citation2015) also noted that religious beliefs shape a moral framework characterized by objective moral truths, loyalty, and purity as fundamental motives for moral behavior. On the other hand, some studies reported inconsistent results on the relationship between religion and the components of EDM (e.g. Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022; Tariq et al., Citation2019). However, individuals with a strong IRO substantiated the endorsement to predict favorable ethical behavior, which led to the following hypotheses:

H4a. Intrinsic religious orientation has a significantly positive influence on moral recognition.

H4b. Intrinsic religious orientation has a significantly positive influence on moral judgment.

H4c. Intrinsic religious orientation has a significantly positive influence on moral intent.

The study conducted by Cullen et al. (Citation1993) on the ethical climate of accounting firms revealed that SOR emerged as a distinct construct. SOR establishes a direct link with the public interest, emphasizing the ethical responsibility of accounting professionals towards society. According to Shafer (Citation2008), ethical climates highlighting SOR or serving the public interest are expected to foster EDM. SOR shares the utilitarian ethical theory since it favors maximizing the joint interests of society (Barnett & Vaicys, Citation2000; Victor & Cullen, Citation1987).

Shafer (Citation2008, Citation2015) found that SOR was significantly related to the ethical behaviors of accountants and auditors. These two studies indicated that individuals were less likely to participate in unethical behavior within an ethical climate emphasizing SOR. In addition, the study by VanSandt et al. (Citation2006) revealed that ethical climates, including SOR, were key predictors of moral behavior. Some empirical studies found inconsistent results. For instance, the study by Musbah et al. (Citation2016) found inconsistent findings across the vignettes used for the components of EDM. Barnett and Vaicys (Citation2000) also found insignificant relationships between SOR and MIT. Similarly, Liu (Citation2020) studied Chinese audit firms’ unethical behavior; however, the study found that SOR was positively related to unethical behavior in the workplace. Therefore, given the role of SOR in the accounting profession and the patterns of empirical findings, the following hypothesis is developed:

H5. Social responsibility has a significantly positive influence on moral judgment.

Dunn and Sainty (Citation2019) state that ethical behavior is cultivated through experiences and interpersonal interactions. Similarly, Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2019) indicated that moral development could be affected by PGP, as it often induces conformity and the embrace of group norms. This, in turn, has the potential to predict the process of EDM. According to Trevino (Citation1986), MJD is more likely to result in MIT when an individual’s peer group provides normative support for ethical behavior. O’Fallon and Butterfield (Citation2005) claimed that peer groups are the strongest predictors of ethical or unethical behavior. Casali and Perano (Citation2021) also indicated that this particular construct, although less explored, has been recognized for its substantial impact on EDM.

The study of Westerman et al. (Citation2007) found a significant and positive influence of PGP on MIT. Yu et al. (Citation2021) also found similar results and concluded that peers were essential referents for EDM. The study by Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2019) found that the unethical behavior exhibited by peers was directly and adversely related to employees’ ethical intentions. These findings confirm that when individuals interact with their peers and observe their peers’ success due to acting morally, they are inspired to follow this behavior and are less likely to contradict moral norms when faced with moral dilemmas (Hirth-Goebel & Weißenberger, Citation2019). Given these discussions, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H6. Peer group pressure has a significantly positive influence on moral judgment.

Based on the development of the preceding hypotheses, Dunn and Sainty (Citation2019) model was modified to accommodate the multifaceted factors of EDM. As shown in , the conceptual framework includes exogenous constructs of LPC, IDA, RLV, IRO, SOR, and PGP. It also incorporated the first three components of Rest’s (Citation1984) model as endogenous constructs: MRC, MJD, and MIT. MRC and MJD serve as exogenous constructs when the objectives are to predict MIT. In addition, MJD served as a mediator in predicting the relationship between MRC and MIT. This framework aims to understand the dynamics of EDM processes among professional accountants and helps to comprehend how the six factors influence EDM across different ethical dilemmas.

5. Research design

5.1. Sample selection and data collection

The study participants were professional accountants offering public accounting services in Ethiopia. The population comprised 1,755 professional accountants registered under the AABE (1,080) and regional audit bureaus (675) in the country. Following the 5:1 criterion established by Bentler and Chou (Citation1987), a sample size of 415 was determined. It is also a considerable sample size based on Adam’s (Citation2020) and Hair et al. (Citation2022) minimum sample size recommendations. The samples were selected through convenience sampling to address issues related to the accessibility and proximity of participants.

A structured questionnaire based on a cross-sectional design was used to collect data. The questionnaire was administered and collected through the personal visits of participants. Of the 415 questionnaires distributed to the participants, the researcher received 356 questionnaires. However, due to considerable missing data, 24 questionnaires were excluded, and 332 remained. Moreover, due to undesirable response patterns like straight lining and further data cleaning, 309 usable questionnaires were finally retained in the analysis, giving a response rate of 74.46 percent (see ).

Table 1. Response rate and demographic information.

The demographic information of study participants is shown in . The majority of participants were male (88.67%). Of the total participants, 57.28% were between 30 and 39 years old. Regarding educational qualifications, 75.08% had bachelor’s degrees, and the remaining participants had master’s degrees and doctorate. Additionally, 77% of the participants had more than five years of work experience.

5.2. Measurement of variables

This study examines professional accountants’ EDM process, treating EDM components as endogenous constructs. Additionally, it explores LPC, moral philosophy (IDA and RLV), IRO, SOR, and PGP as exogenous constructs. All indicators of the constructs were measured using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

5.2.1. Ethical decision-making

According to Buchan (Citation2005) and Hunt and Vitell (Citation1986), studying ethical behavior poses difficulties because individuals might not demonstrate their actual behavior. Specifically, the ethical evaluation of an issue is an abstract concept that cannot be explicitly measured; instead, vignettes are frequently used as a proxy in business ethics studies (Buchan, Citation2005; Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986; Johari et al., Citation2017). Vignettes developed by Flory et al. (Citation1992) are commonly used to study ethical dilemmas in accounting. Researchers have reported high internal consistency, content, and predictive validity among the vignettes (Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh, Citation2019). This study adopted three vignettes to measure MRC, MJD, and MIT (i.e. endogenous constructs). The vignettes involve the ethical dilemmas of questionable expense reports, manipulation of company accounts, and overriding company policy. Hence, the vignettes were slightly modified to accommodate actual accounting practices in Ethiopia (see Annexure I).

Moores et al. (Citation2018) claimed that most EDM studies use a single indicator to measure MRC, MJD, and MIT. However, it is recommended to incorporate numerous indicators to reduce item bias (Hair et al., Citation2022). To benefit from this, indicators developed by Moores et al. (Citation2018) were adopted in this study. Five reflective items were included in the questionnaire after each vignette for each component (see ).

Table 2. Measurement and operationalization.

5.2.2. Moral philosophy

The Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) scale developed by Forsyth (Citation1980) is frequently used to study the degree of moral philosophy. Forsyth claimed that the EPQ had adequate internal consistency and reliability. Numerous researchers have also admitted that EPQ has been tested in several business ethics studies as a valid tool for measuring personal moral philosophies (Musbah et al., Citation2016; Singhapakdi et al., Citation1999). Thus, this study adopted twenty reflective items of the EPQ to examine the moral philosophies: ten items pertain to IDA and the other ten to relativism.

5.2.3. Laws and professional codes and social responsibility

The Ethical Climate Questionnaire (ECQ), developed by Victor and Cullen (Citation1987), is used to measure ethical climate dimension types (Buchan, Citation2005; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Shafer, Citation2008). It is reported that ECQ possessed adequate internal consistency and reliability. Four reflective items for each dimension of the ethical climate dimensions of LPC and SOR were included in the questionnaire from the 1993 version (see Cullen et al., Citation1993). The items were slightly modified to consider individual levels of analysis.

5.2.4. Intrinsic religious orientation and peer group pressure

Indicators to measure IRO were derived from the studies of Shariff (Citation2015), Sulaiman et al. (Citation2022) and Tariq et al. (Citation2019). This construct includes five reflective items. The indicators of PGP were derived from the studies of Hull (Citation1999) and Yu et al. (Citation2021). Five reflective items were incorporated to measure this construct. shows the indicators of each construct.

A pilot study was conducted using convenient samples of forty accounting professionals and academicians. In addition, comments were received about the contents, sequence, manageability, and understandability of the items in the questionnaire, which helped to ensure face and content validity. A reliability test of Cronbach’s alpha values >0.750 was found for distinct construct groups, indicating no need for further revision. To address potential problems of social desirability bias and common method biases, the questionnaire cover page explicitly stated and assured confidentiality, anonymity, and the exclusive academic purpose of the study. Besides, the questionnaire was structured by separating the constructs into distinct sections. For ease of understandability and convenience, the questionnaire was translated into Amharic, Ethiopia’s official language, and the local names of individuals were used in the vignettes.

Harman’s single-factor test was employed to evaluate the common method bias in the data (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The test results demonstrate that a single-factor solution accounted for only 40.40% of the total variance, falling below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%, suggesting it was not a significant concern in this study. Additionally, the full collinearity approach proposed by Kock (Citation2015) was used to test the possibility of common method bias. Variance inflation factor (VIF) values accounted for below 3.3, indicating no potential common method bias issue in the current study (see ).

6. Empirical results and discussion

Hair et al. (Citation2022) state that structural equation modeling (SEM) enables precise modeling and estimating of complex relationships among multiple constructs. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is one variant of SEM widely used in social science studies. It is a nonparametric method that employs bootstrapping to determine statistical significance and establish confidence intervals for parameter estimates and statistical inference (Hair et al., Citation2019). The data analysis used PLS-SEM methodology in the current study, employing SmartPLS 4.0 software (Ringle et al., Citation2022). It helps to leverage handling multiple constructs and indicators, particularly in the vignette-rich settings of the current study, and it excels in maximizing the explained variance in the endogenous constructs of the study.

6.1. Descriptive statistics

As presented descriptive features of the result, the mean values for the exogenous and endogenous constructs, except for relativism as expected, were notably above average. This suggests that, on average, participants tended toward agreement-oriented responses. When compared to the other exogenous constructs, IRO displayed a relatively small standard deviation value (0.696), indicating that participants showed less variability across the indicators of this construct. In contrast, other constructs had slightly higher standard deviations, suggesting relative variability in participant responses across the indicators for those constructs. Exogenous constructs, except RLV, offer descriptive evidence of their positive influence on MRC, MJD, and MIT.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

Notably, the mean values of MRC, MJD, and MIT across the vignettes exhibited above-average values. However, there were noticeable variations among the vignettes. Vignette 2 exhibited higher mean values than the other two vignettes. Additionally, when comparing mean values between vignettes 1 and 3, the former consistently showed higher mean values, except for MJD. Nevertheless, relatively high standard deviations for endogenous constructs in vignette 2 suggest compelling differences between participants’ responses.

6.2. Measurement model

The initial stage of assessing a reflective measurement model entails examining the indicator loadings. Factor loadings above 0.708 indicate that the construct explains over 50 percent of the variance in the indicator (Hair et al., Citation2019). Based on the results presented in , the factor loadings were above threshold values. However, one indicator (PGP5) was removed (loading = 0.457, 0.442, 0.426 for vignettes 1, 2, and 3, respectively) to improve the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values.

Table 4. Indicators loading and reliability.

The second step assessed internal consistency reliability through Cronbach’s alpha and CR. Higher values usually signify better reliability; however, values exceeding 0.950 are problematic (Hair et al., Citation2022). As shown in , the results show that the values surpass the threshold of 0.700 for both measures, indicating acceptable reliability. Hence, the CR value (0.950) of MJD in vignette 1 was between the bootstrapped confidence interval [0.939, 0.958], indicating the value was significantly within the recommended threshold.

The next stage of the measurement model assessment evaluates convergent validity. It is assessed based on the average variance extracted (AVE), and a value of >0.500 is acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2022). As presented in , the AVE values were above 0.500, indicating that the three vignette constructs effectively elucidated the convergent validity.

Table 5. Average variance extracted (AVE).

The discriminant validity measures how distinct a construct is from the other constructs in the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2022). It is assessed based on the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio and the Fornell and Larcker criterion. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), the threshold for the HTMT ratio is < 0.850. For the Fornell and Larcker criterion, the square root of AVE on diagonal lines should be greater than the correlation between the constructs underneath. As presented in , the values above bold and italicized diagonal elements for the constructs were less than 0.85 and met HTMT criteria. In addition, the values below the bold and italicized diagonal elements in were well below the square root of AVE (bold and italicized diagonal values) and met the Fornell and Larcker criterion.

Table 6. Fornell and Larcker criterion and the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

These assessments for both measures confirmed the distinctiveness of the constructs. The reliability and validity assessments confirmed that all the indicators and constructs met the necessary measurement model assessment criteria.

6.3. Structural model

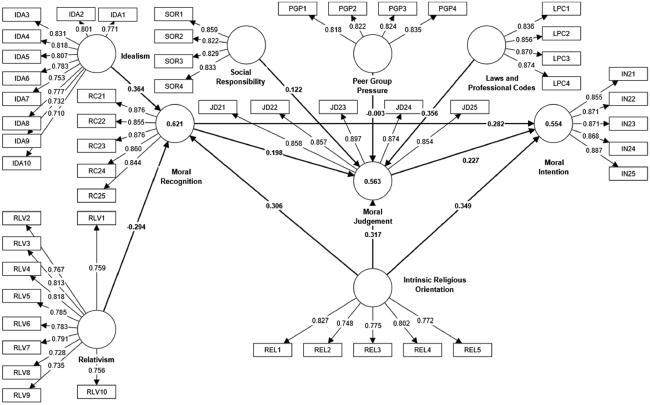

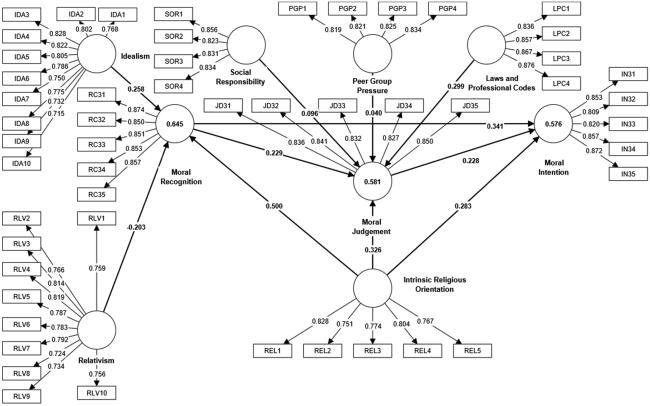

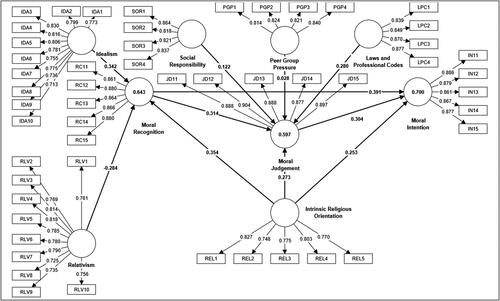

Once the measurement model assessment in PLS-SEM is established and satisfactory (see for vignette 1; see Annexure II for vignettes 2 and 3), the structural model is evaluated. The assessment began with an examination of potential collinearity. Hair et al. (Citation2019) indicated that VIF values should be close to three or lower. As shows, all constructs of VIF values for the three vignettes were <3. This finding suggests that there was no significant collinearity among the predictor constructs. Once it is ensured that collinearity is not at the critical level, the next step assesses the significance and relevance of the structural model relationships using the bootstrapping procedure in PLS-SEM with 10,000 bootstrap subsamples.

Table 7. Variance inflation factor (VIF).

The standard assessment criteria for the structural model include the coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive power (Q2) (Hair et al., Citation2022). As shown in , the structural model relationships explain 55.4% to 70.0% of the MRC, MJD, and MIT variance across the three vignettes. These values signify a pronounced explanatory power (R2) level for the constructs in the model, and the predictor constructs to explain the outcome constructs were substantial. The effect size (f2) values indicated varying effect sizes across different constructs and vignettes. Some relationships exhibited weak effect sizes and suggested a limited effect of exogenous constructs on endogenous constructs. A medium effect size was apparent for most constructs. The large effect size, especially in the relationship between IRO -> MRC in vignette 3, was observed and implied a more substantial effect. Conversely, PGP -> MJD consistently had the lowest f2 value across all three vignettes, indicating no effect on MJD. Moreover, presents the model’s predictive power: Q2 values for all endogenous constructs (MRC, MJD, and MIT) in the three vignettes were greater than zero. This finding substantiates the fact that the model has predictive relevance.

Table 8. Results of the structural model.

Model fit is also assessed based on the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and the normed fit index (NFI) (Hair et al., Citation2022). SRMR values for the three vignettes ranged from 0.045 to 0.048, below the threshold value of <0.080. However, NFI values for the three vignettes ranged from 0.820 to 0.837, which fell slightly below the threshold values of >0.900. The SRMR values suggested a good fit between the models and the data, while the NFI values, though near the threshold, still indicated a reasonably acceptable fit.

6.3.1. Hypotheses testing

This study examines the relationships of the first three components of EDM, along with six factors. presents the results concerning the path coefficients associated with the direct relationships postulated in the hypotheses.

Table 9. Direct relationships (hypotheses).

The analysis of the three vignettes revealed consistent and significant relationships between the components of EDM (see ). MRC exhibited a significant and positive relationship with MJD in all vignettes (H1a). Similarly, MJD exhibited a positive and significant relationship with MIT across all vignettes (H1b). These findings fully supported the hypotheses and the logical sequence implied in Rest’s (Citation1984) EDM framework. These relationships underline that recognizing moral issues is fundamental to the subsequent MJD and shaping professional accountants’ intentions to act. The study of Rottig et al. (Citation2011) also noted that individuals who perceive an action as just, fair, or morally right are more inclined to engage in MJD and develop an intent to engage in that behavior. Other studies’ findings have supported these relationships (Johari et al., Citation2017; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Oboh & Omolehinwa, Citation2022). However, the study’s results do not support some empirical studies’ results that posit that MRC does not affect MJD; instead, other mediating constructs play a role in the relationship between MRC and MJD (Barnett & Vaicys, Citation2000; Latan et al., Citation2019; Moores et al., Citation2018).

In addition, MRC was significantly and positively related to MIT in all vignettes. This relationship fully supported H1c and emphasized the connection between recognizing moral issues and its relation to shaping the subsequent MIT. In this case, in addition to the implied logical sequence, Rest (Citation1984) demonstrated the profound influence of MRC on MIT. Rest claimed that the components mutually influence each other through feedback and feedforward loops. Although extant literature has not considered this relationship, the study of Johari et al. (Citation2017) found significant results regarding the relationship between MRC and MIT. This highlights how recognizing moral dilemmas predicts professional accountants’ subsequent moral intentions and behaviors.

The influences of several factors on EDM were evidenced in this study. LPC consistently demonstrated a significant and positive influence on MJD across all vignettes. This finding fully supports H2. This relationship emphasizes the role of external rules and standards in shaping professional accountants’ EDM. Based on the deontology ethical theory perspective, this relationship focuses on adhering to moral rules or duties, irrespective of consequences (Brady, Citation1985; Brady & Dunn, Citation1995; Hunt & Vitell, Citation1986, Citation2006). Thus, this finding aligned its importance with deontological theory in evaluating moral behavior with the rules and standards that govern the accounting profession.

Similarly, Kohlberg’s (Citation1976) cognitive moral development theory of law and order orientation supports professional accountants’ moral judgment. Previous empirical studies have supported the influence of LPC on MJD (Fatemi et al., Citation2020; Modarres & Rafiee, Citation2011; Pflugrath et al., Citation2007). Although most studies profoundly focused on codes of contact and overlooked the role of laws, the studies found that implementing and enforcing codes of conduct positively related to ethical behavior. However, some studies that examined the intertwined construct of LPC found insignificant results (Barnett & Vaicys, Citation2000; Liu, Citation2020).

The study’s findings fully supported the proposed hypotheses (H3a and H3b) of the two types of personal moral philosophies. IDA significantly and positively influenced MRC in all three vignettes (H3a). Conversely, RLV significantly and negatively influenced MRC across all vignettes (H3b). These results highlight that professional accountants who follow IDA tend to exhibit higher levels of moral awareness due to their commitment to providing positive consequences, whereas relativistic professional accountants negatively predict MRC. Previous studies have also supported that IDA and RLV are positive and negative predictors of ethical behavior, respectively (Johari et al., Citation2017; Musbah et al., Citation2016; Singhapakdi et al., Citation1999; Zaikauskaite et al., Citation2020). The interaction of high and low personal moral philosophies highlights the importance of applying deontological and utilitarian ethical theories based on the context of ethical dilemmas.

shows that the results substantiate the proposed hypotheses regarding religious orientation in predicting the EDM of professional accountants (H4a, H4b, and H4c). The IRO of professional accountants significantly and positively influences MRC, MJD, and MIT across all three vignettes. Based on the deontological ethical theory, professional accountants inclined to IRO evaluate ethical dilemmas based on the principles and standards of religious doctrine, unlike those with an extrinsic religious orientation. Vitell et al. (Citation2009) supported this and indicated that individuals’ religious beliefs and values often guide their moral compass and influence their ethical behavior. In the extant literature, similar results have also reported that IRO positively predicts ethical behavior (Kportorgbi et al., Citation2022; Singhapakdi et al., Citation2013; Tariq et al., Citation2019). Thus, IRO provides professional accountants with a foundation for EDM by offering moral guidelines, adhering to norms, instilling a sense of accountability, promoting compassion, and providing conflict resolution strategies.

SOR significantly and positively influenced MJD in the first and second vignettes (H5). Although this relationship was not supported in vignette 3, this highlights its importance in specific contexts (see ). Previous studies have also demonstrated the influence of SOR on individuals’ ethical behavior (Barnett & Vaicys, Citation2000; Shafer, Citation2008; VanSandt et al., Citation2006). The studies indicated that when professional accountants are aware of their social responsibility, they are more likely to consider the broader implications of their actions in the public interest. This enhances professional accountants’ ability to make MJDs that are not solely self-interested. Instead, based on the utilitarian ethical theory perspective, accountants evaluate the ethical dilemmas and make MJD that have positive consequences to benefit society.

Based on the result in , it can be seen that PGP has no influence on professional accountants’ MJD across all vignettes (H6). However, other empirical studies have found a significant role for peer groups in the EDM process (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2019; Westerman et al., Citation2007; Yu et al., Citation2021). In their review, O’Fallon and Butterfield (Citation2005) and Casali and Perano (Citation2021) indicated that the intensity and frequency of peer group interactions influence EDM. Contrary to expectations, this study found that PGP had no statistically significant influence on the MJD of professional accountants. This finding suggests that external party influence might not always play a role in shaping the EDM of professional accountants.

Kohlberg (Citation1976) argued that individuals encounter cognitive conflict by being exposed to the moral reasoning of peer groups that differ in content or structure from their reasoning. This assertion posits that individuals do not fully permit external interference during their EDM process. This is also apparent in this study that PGP did not influence professional accountants’ MJD. Deontological and utilitarian ethical theories help to evaluate peer group influence in the MJD. A deontological analysis would view such influence negatively if a peer group encourages actions against fundamental moral rules. On the other hand, utilitarianism would evaluate whether the MJD influenced by the peer groups leads to positive or negative consequences for society.

Generally, the study’s findings supported most of the hypothesized path-model relationships among the constructs (see ). However, the hypotheses for PGP for all vignettes (PGP -> MJD) and SOR for the third vignette (SOR -> MJD) were not supported. Most notably, all constructs, except RLV, have a positive relationship with the components of EDM. In contrast, the negative relationships (RLV -> MRC) were consistent across all vignettes, showing its negative effect on MRC regardless of the context in the vignettes. While some relationships between constructs exhibited consistent patterns across vignettes, the strengths of these relationships vary across vignettes. The observed variations and patterns indicate the significance of considering each vignette’s distinctive characteristics based on deontological and utilitarian ethical theory lenses.

6.3.2. Mediation analysis

After evaluating the direct relationships, mediation analysis was conducted for hypothesis H1d. The indirect effect in all vignettes was statistically significant, as evidenced by the absence of zero within the 95% confidence intervals (see ). Notably, the direct effect of MRC on MIT was significant (β = 0.391, t = 6.388, p < 0.001; β = 0.283, t = 4.629, p < 0.001; β = 0.344, t = 4.923, p < 0.001) across all vignettes. Furthermore, when investigating the indirect effect, MRC significantly influenced MIT through MJD in all vignettes of the study (β = 0.096, t = 3.682, p < 0.001; β = 0.045, t = 2.341, p = 0.019; β = 0.053, t = 2.309, p = 0.021). These findings substantiate that MJD partially mediates the relationship, as the direct and indirect effects were significant in all cases. Moreover, the product of both direct and indirect effects suggests that MJD plays a complementary partial mediating role in the relationship between MRC and MIT. Consequently, the results fully supported the hypothesis (H1d) across all vignettes.

Table 10. Mediation analysis.

In addition to the direct influence of MJD on MIT, based on Rest’s (Citation1984) synthesis and the findings of this study, this study provides a solid foundation for the mediating role of MJD between MRC and MIT. Similarly, Yang and Wu (Citation2009) also found the relationship between MRC and MIT partially mediated by the presence of MJD. The study of Rottig et al. (Citation2011) indicated substantial indirect effects of MRC influence on MIT. Buchan (Citation2005) also found that moral sensitivity positively predicted the MIT of public accountants. This relationship highlights the importance of professional accountants’ moral awareness of various accounting ethical issues in shaping their MIT to act ethically.

7. Summary and conclusion

This study aims to examine the relationships between the components of EDM and factors that contribute to the EDM of professional accountants. Using PLS-SEM, the study examined the postulated relationships of the conceptual framework. The intention to behave ethically depends on recognizing an ethical dilemma and its moral judgment. Thus, the positive relationship between the components of EDM and the complementary partial mediating role of MJD highlights its importance in recognizing moral issues and forming the subsequent MIT among professional accountants.

LPC’s influence on MJD was evident and highlighted the role of external rules and regulations in shaping professional accountants’ EDM. Similarly, the moral philosophy of IDA positively influenced the MRC of professional accountants, whereas RLV negatively influenced the MRC. IRO has emerged as a strong positive predictor of EDM. This suggests that religious beliefs serve as a guiding framework to promote EDM among professional accountants. Additionally, when accountants are aware of their SOR role, they are more likely to consider the broader implications of their actions to align with the public interest.

However, PGP has not demonstrated a statistically significant relationship with MJD. This finding does not support the conventional notion that peer groups influence EDM among professional accountants. This implies that individuals perceive themselves as more ethical than their peers regarding ethical beliefs and behavior. Based on the context, the deontological and utilitarian ethical theories apply to evaluate the ethical dilemmas.

This study provides valuable implications for the EDM process. In addition to the direct relationships among the components of EDM, MJD bridges the perceived awareness of ethical issues and forms the subsequent intention to act ethically. This adds the mediating role of MJD to the existing literature. Besides, in designing interventions for ethical behavior, strategies might include ethics training programs that focus on enhancing MRC skills and MJD refining abilities, ultimately fostering professional accountants’ EDM. In essence, other factors are crucial for understanding the ethical setting of the accounting profession. As the profession evolves, acknowledging the influence and relationships of other factors is essential to promoting ethical competency among professional accountants. In turn, this ensures the public interest in the accounting profession.

However, this study examined a limited number of EDM factors, acknowledging the existence of potential factors that could substantiate the dynamics of the EDM process. Thus, future studies are encouraged to consider other factors. The study’s context-specific findings highlight the diversity of ethical perspectives that lead to the need to be cautious when generalizing results. Longitudinal studies and using different types of data, like interviews or behavior observations, will help researchers find out how factors change over time without relying on self-reported data. Furthermore, comparative studies across diverse groups can reveal the specific influences that help enrich the global comprehension of EDM. Moreover, it is necessary to consider endogeneity, linearity, and unobserved heterogeneity testing in future studies.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Ishwara P has contributed to the conception, design, execution and interpretation of the study, has critically reviewed and revised the article before submission, has agreed to submit the article for publication in Cogent Business and Management journal, has agreed to review all article versions during all stages of the publication, has agreed to approve the final version to be published, has agreed to take responsibility and be accountable for the article’s contents. Share responsibility to resolve any questions raised about the accuracy or integrity of the published work. Naod Mekonnen has contributed to the conception, study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, has drafted the article, has agreed to submit the article for publication in Cogent Business and Management journal, has agreed to revise all versions of the article during all stages of the publication, has agreed to take responsibility and be accountable for the article’s contents. Share responsibility to resolve any questions raised about the accuracy or integrity of the published work, and has agreed to be the corresponding author of the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the pilot and main survey participants and SmartPLS teams.

Disclosure statement

This research has no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability

The study’s data are available at https://doi.org/10.17632/zwwf46dydh.1.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ishwara P

Ishwara P is a professor and dean in the Faculty of Commerce at Mangalore University, India. His research areas include finance, investment, accounting, banking, corporate social responsibility, and human resource management. He has extensive experience teaching at the university, supervising PhD candidates, and actively writing in several scientific journals. He has presented and attended several workshops.

Naod Mekonnen

Naod Mekonnen is an assistant professor in the Department of Accounting and Finance at Wollo University, Ethiopia. He is pursuing his PhD at Mangalore University, Department of Commerce, India. His research areas include accounting ethics, BPR, microfinance institutions, auditing, and AIS.

References

- Adam, A. M. (2020). Sample size determination in survey research. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 26(5), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.9734/jsrr/2020/v26i530263

- Andersch, H., Arnold, C., Seemann, A. K., & Lindenmeier, J. (2019). Understanding ethical purchasing behavior: Validation of an enhanced stage model of ethical behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 48(December 2017), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.02.004

- Baker, C. R. (1999). Theoretical approaches to research on accounting ethics. Research on Accounting Ethics, 5(5), 257–268.

- Barnett, T. (2001). Dimensions of moral intensity and ethical decision making: An empirical study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(5), 1038–1057. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02661.x

- Barnett, T., & Vaicys, C. (2000). The moderating effect of individuals’ perceptions of ethical work climate on ethical judgments and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006382407821

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Brady, F. N. (1985). A Janus-headed model of ethical theory: Looking two ways at business/society issues. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 568. https://doi.org/10.2307/258137

- Brady, F. N., & Dunn, C. P. (1995). Business meta-ethics: An analysis of two theories. Business Ethics Quarterly, 5(3), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857390

- Buchan, H. F. (2005). Ethical decision making in the public accounting profession: An extension of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-0277-2

- Casali, G. L., & Perano, M. (2021). Forty years of research on factors influencing ethical decision making: Establishing a future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 132(July), 614–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.006

- Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73(2), 667–674. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.73.2.667

- Dunn, P., & Sainty, B. (2019). Professionalism in accounting: A five-factor model of ethical decision-making. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(2), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-11-2017-0240

- Fatemi, D., Hasseldine, J., & Hite, P. (2020). The influence of ethical codes of conduct on professionalism in tax practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 164(1), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4081-1

- Proclamation No. 847/2014. (2014). Pub. L. No. Financial Reporting-20th Year No. 81. Federal Negarit Gazette of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 7714.

- Flory, S. M., Phillips, T. J., Reidenbach, R. E., & Robin, D. P. (1992). A multidimensional analysis of selected ethical issues in accounting. Accounting Review, 67(2), 411–416.

- Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.1.175

- Forsyth, D. R. (1992). Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5–6), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00870557

- Regulation No.332/2014. (2015). Pub. L. No. Council of ministers regulation to provide establishment and determine the procedure of the accounting and auditing board of Ethiopia-21th Year No.22. Federal Negarit Gazette of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 7958.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hirth-Goebel, T. F., & Weißenberger, B. E. (2019). Management accountants and ethical dilemmas: How to promote ethical intention? Journal of Management Control, 30(3), 287–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-019-00288-7

- Hull, A. K. (1999). Influence and change: A study of the ethical decision making of trainee accountants. University of Nottingham.

- Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/027614678600600103

- Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (2006). The general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146706290923

- Johari, R. J., Mohd-Sanusi, Z., & Chong, V. K. (2017). Effects of auditors’ ethical orientation and self-interest independence threat on the mediating role of moral intensity and ethical decision-making process. International Journal of Auditing, 21(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12080

- Keller, A. C., Smith, K. T., & Smith, L. M. (2007). Do gender, educational level, religiosity, and work experience affect the ethical decision-making of U.S. accountants? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2006.01.006

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kohlberg, L. (1976). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-developmental approach. In T. Lickona (Ed.), Moral development and behavior: Theory, research and social Issues (pp. 31–53). Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Kportorgbi, H. K., Aboagye-Otchere, F., & Kwakye, T. O. (2023). Ethical tax decision-making: Evaluating the effects of organizational prestige valuations and tax accountants’ financial situation. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2196037

- Kportorgbi, H. K., Kwakye, T. O., & Aboagye-Otchere, F. (2022). Ethical decision-making of tax accountants: Examining the relative effect of religiosity, re-enforced tax ethics education and professional experience. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2149148

- Latan, H., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., & Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. (2019). Ethical awareness, ethical judgment and whistleblowing: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3534-2

- Liu, A. A. (2020). Trainee auditors’ perception of ethical climate and workplace bullying in Chinese audit firms. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 5(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-07-2019-0060

- Mihret, D. G., James, K., & Mula, J. M. (2012). Accounting professionalization amidst alternating state ideology in Ethiopia. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25(7), 1206–1233. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571211263248

- Mintz, S. M., & Morris, R. E. (2017). Ethical obligations and decision making in accounting (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Modarres, A., & Rafiee, A. (2011). Influencing factors on the ethical decision making of Iranian accountants. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111111114594

- Moores, T. T., Smith, H. J., & Limayem, M. (2018). Putting the pieces back together: Moral intensity and its impact on the four‐component model of morality. Business and Society Review, 123(2), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12141

- Musbah, A., Cowton, C. J., & Tyfa, D. (2016). The role of individual variables, organizational variables and moral intensity dimensions in Libyan management accountants’ ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2421-3

- Narvaez, D., & Rest, J. (1995). The four components of acting morally. In J. L. Gewirtz & W. M. Kurtines (Eds.), Moral development: An introduction (pp. 1–548). Allyn and Bacon.

- O’Fallon, M. J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2005). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996-2003. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(4), 375–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0551-005-2929-7

- Oboh, C. S. (2019). Personal and moral intensity determinants of ethical decision-making: A study of accounting professionals in Nigeria. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 9(1), 148–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-04-2018-0035

- Oboh, C. S., & Omolehinwa, E. O. (2022). Sociodemographic variables and ethical decision-making: A survey of professional accountants in Nigeria. RAUSP Management Journal, 57(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-04-2020-0086

- Owusu, G. M. Y., & Korankye, G. (2023). The state of ethical decision‐making research in accounting: A retrospective assessment from 1987 to 2022. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(2), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12519

- Pflugrath, G., Martinov‐Bennie, N., & Chen, L. (2007). The impact of codes of ethics and experience on auditor judgments. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(6), 566–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900710759389

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Rest, J. R. (1984). The major components of morality. In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behavior, and moral development (Personalit, pp. 1–425). John Wiley & Sons.

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2022). SmartPLS (4). SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com

- Rottig, D., Koufteros, X., & Umphress, E. (2011). Formal infrastructure and ethical decision making: An empirical investigation and implications for supply management. Decision Sciences, 42(1), 163–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00305.x

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Bañón-Gomis, A., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2019). Impacts of peers’ unethical behavior on employees’ ethical intention: Moderated mediation by Machiavellian orientation. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12210

- Schwartz, M. S. (2015). Ethical decision-making theory: An integrated approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(4), 755–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2886-8

- Shafer, W. E. (2008). Ethical climate in Chinese CPA firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(7–8), 825–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.08.002

- Shafer, W. E. (2015). Ethical climate, social responsibility, and earnings management. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1989-3

- Shariff, A. F. (2015). Does religion increase moral behavior? Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.009

- Shukla, A., & Srivastava, R. (2016). Influence of ethical ideology and socio-demographic characteristics on turnover intention: A study of retail industry in India. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1238334

- Singhapakdi, A., Karande, K., Rao, C. P., & Vitell, S. J. (2001). How important are ethics and social responsibility? A multinational study of marketing professionals. European Journal of Marketing, 35(1/2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560110363382

- Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., & Franke, G. R. (1999). Antecedents, consequences, and mediating effects of perceived moral intensity and personal moral philosophies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399271002

- Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Lee, D. J., Nisius, A. M., & Yu, G. B. (2013). The influence of love of money and religiosity on ethical decision-making in marketing. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1334-2

- Sulaiman, R., Toulson, P., Brougham, D., Lempp, F., & Haar, J. (2022). The role of religiosity in ethical decision-making: A study on Islam and the Malaysian workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(1), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04836-x

- Tariq, S., Ansari, N. G., & Alvi, T. H. (2019). The impact of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity on ethical decision-making in management in a non-Western and highly religious country. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 8(2), 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-019-00094-3

- Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.2307/258313

- Trevino, L. K., Butterfield, K. D., & McCabe, D. L. (1998). The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(3), 447–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857431

- Valentine, S. R., & Bateman, C. R. (2011). The impact of ethical ideologies, moral intensity, and social context on sales-based ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0807-z

- VanSandt, C. V., Shepard, J. M., & Zappe, S. M. (2006). An examination of the relationship between ethical work climate and moral awareness. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(4), 409–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9030-8

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1987). A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. In W. C. Frederick & L. E. Preston (Eds.), Research in corporate social performance and policy (Vol. 9, pp. 51–71). JAI Press.

- Vitell, S. J., Bing, M. N., Davison, H. K., Ammeter, A. P., Garner, B. L., & Novicevic, M. M. (2009). Religiosity and moral identity: The mediating role of self-control. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(4), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9980-0

- Westerman, J. W., Beekun, R. I., Stedham, Y., & Yamamura, J. (2007). Peers versus national culture: An analysis of antecedents to ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(3), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9250-y

- Yang, H., & Wu, W. (2009). The effect of moral intensity on ethical decision making in accounting. Journal of Moral Education, 38(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240903101606

- Yu, H., Siegel, J. Z., Clithero, J. A., & Crockett, M. J. (2021). How peer influence shapes value computation in moral decision-making. Cognition, 211(March), 104641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104641

- Zaikauskaite, L., Chen, X., & Tsivrikos, D. (2020). The effects of idealism and relativism on the moral judgement of social vs. environmental issues, and their relation to self-reported pro-environmental behaviours. PloS One, 15(10), e0239707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239707

Annexure I.

Vignettes

Vignette 1: Friew is a young accountant at a company. After some experience in accounting at headquarters, he has been transferred to one of the company’s recently acquired divisions, run by its previous president, Belay. Belay has been retained as vice president of this new division, and Friew is his accountant.

The main area of concern for Friew is Belay’s expense reports. Belay’s boss, the president, approves the expense reports without review and expects Friew to check the details and work out any discrepancies with Belay. After a series of large and questionable expense reports, Friew challenges Belay directly about charges to the company for delivering some personal furniture to Belay’s home. Although the company’s policy prohibits such charges, Belay’s Boss signed on for the expense again. Friew feels uncomfortable with this and tells Belay that he is considering taking the matter to the Internal Audit Department for review. Belay reacts sharply, reminding Friew that ‘the department will back me anyway’ and that Friew’s position in the company would be in danger. Decision: Friew decides not to report the expense charge to the Internal Audit Department of the company.

Vignette 2: Abeba, a company accountant, was told by the manager to restate the company’s earnings to attract potential investors. Asmamaw, her assistant, suggests that Abeba to review some expenses for possible reduction. He also avoids the management letter request from the external auditor to write-down the inventory record to reflect the ‘true value’.

Abeba discusses the situation with her husband, Yalew, a senior manager at another company. She said, ‘I am supposed to support my company, but on the other hand, I am supposed to be ethical.’ Yalew tells her that other companies do this all the time. He reminds her how important her salary is to maintain their comfortable lifestyle and that she should not do anything that might cause her to lose her job. Decision: Abeba decides to accept the suggestions proposed by her boss.