Abstract

In the 21st century, employers must prepare for the deployment of Generation Z in the workforce. There is little understanding of Gen Z’s work behavior such as employee engagement and innovative behavior. This research aims to identify determinants that influence Gen Z’s innovative behavior via the mediating effect of employee engagement and the moderating effect of proactive personality. The quantitative method was employed with a sample size of 352 Gen Z employees in Vietnam. The data were analyzed with SPSS and AMOS, and structural equation modeling was conducted to test the hypotheses. The results confirmed that transformational leadership, learning climate, trust, self-efficacy, job insecurity and time pressure affect Gen Z’s work engagement and work engagement mediates the relationship between these determinants and innovative behavior. Proactive personality moderates the relationship between employee engagement and innovative behavior. The findings extend the understanding of the refined job demands-resources theory and enhance the current knowledge of Gen Z’s engagement and innovative behavior.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Research background

In the 21st century, technology has changed rapidly and strongly influenced human life. Individuals born in various eras now have personalities, worldviews and values that differ from those born earlier. Political, cultural and economic alterations have a substantial effect on the ways individuals understand the world and how they ought to act (Berkup, Citation2014). Acknowledging these differences, employers must prepare for the arrival of Generation Z, born between 1997 and 2013 (Dimock, Citation2019). According to Lu and Miller (Citation2018), Gen Z comprises 32% of the world’s population. This new cohort is still a subject that has not received as much attention as Gen Y, which has been the focus of extensive study (Haddouche & Salomone, Citation2018). Nowadays, managers must be able to manage young and inexperienced employees and the generational traits that have been influenced by their personal experiences (Schroth, Citation2019). Researchers have emphasized the significance of better understanding Gen Z workers and have called for new techniques and strategies to increase knowledge of generational differences in the workplace (Goh & Okumus, Citation2020). Therefore, it is crucial to pinpoint the elements influencing Gen Z’s work engagement so businesses can take appropriate action to retain them and their precious skills (Lee et al., Citation2021). Kahn (Citation1990) defined personal engagement as ‘the harnessing of organizational members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances’ (p. 694). In his work, personal engagement was defined as behaviors by which people bring their selves to work role performances. Factors influencing employee engagement have been explored in plenty of research, underpinned by the theoretical support of the job demands-resources model (JD-R) (Bakker et al., Citation2007). Based on the JD-R model, dynamic interactions between various job demands and job resources that influence employee engagement have been studied (Bakker et al. Citation2003). Job resources can be identified as leadership styles, job autonomy, organizational policies and culture toward work-life balance or development opportunities, while several job demands can be named as job insecurity or time pressure (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). Meanwhile, numerous studies consistently confirm the positive relationship between employee engagement and other organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction, commitment and organizational financial performance (Bailey et al., Citation2017; Barrick et al., Citation2015; Musgrove et al., Citation2014; Saks, Citation2019).

To remain productive and make a profit, organizations must be able to understand and maintain their valued employees. It is essential to retain these individuals while managing the outstanding abilities of Gen Z. Dolot (Citation2018) stated that Generation Z is expected to switch jobs frequently, but 39% of them would remain for an employer for an extended time if the work were attractive. A strategy for keeping employees in the business is to encourage employee engagement (Larasati & Hasanati, Citation2019). Organizations utilizing engaged workers had 6% higher net profit margins than companies with disengaged employees (Kruse, Citation2012). Furthermore, to obtain a competitive advantage, employees must innovate processes, methods and procedures (Shalley et al., Citation2004). Ployhart (Citation2015) argued that employee innovation is essential for increasing the company’s competitiveness and ensuring its survival. Many researchers in this area have provided evidence that employees must exhibit innovative behavior for the organization to perform better (Sameer, Citation2018; Turek & Wojtczuk-Turek, Citation2017). According to Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2007), work-related well-being encourages employee innovation. Innovative employee behaviors (eg generating, recognizing and carrying out novel ideas for products and work practices) are essential to an organization’s success in a fast-paced market (Kanter, Citation1983; West & Farr, Citation1990). Typical indicators of innovative behavior involve investigating cutting-edge technologies, suggesting solutions to problems, instituting innovative practices and researching and securing funds for novel and beneficial ideas (Yuan & Woodman, Citation2010). Although numerous studies examine how autonomy, work-life balance and effective leadership relate to employee engagement, few studies focused on Gen Z (Lee et al., Citation2021). Much earlier research on Gen Z was conducted mostly in the United States, which could lead to a biased perception of this generation while visions, preferences and characteristics of Gen Z vary by region (Scholz, Citation2019) or by their work contexts (Leslie et al., Citation2021). There is also minimal understanding of how to promote innovative behavior by engaging Gen Z at work. In addition, little is known about the effect of Gen Z’s proactive personality on their engagement and innovative behavior. Therefore, this research is threefold: (1) to explore determinants of innovative behavior via the mediating effect of employee engagement; (2) to provide empirical evidence for the refined job demand-resources model when being applied to Gen Z in Vietnam; (3) to test the moderating role of proactive personality for knowledge enhancement in behavioral studies.

To address the above concerns, this study aims to answer the following questions:

Which factors affect innovative behavior through employee engagement of Gen Z employees in Vietnam?

Does the proactive personality of Gen Z moderate the relationship between employee engagement and innovative work behavior?

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical background

2.1.1. The job demands-resources (JD-R) framework

The job demands and resources (JD-R) model classifies the features of workplaces into two broad categories: job demands and job resources (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Depending on the research context, each category includes a variety of particular demands and resources. Job demands refer to those aspects of a job that are physically exhausting, socially engaging, as well as organizationally demanding and that cause physiological or psychological expenses as a result of the continuous physical and/or mental exertion necessary. On the other hand, job resources are characteristics associated with a career that positively influence a staff member’s performance at work, both mentally and physically and even their growth and learning (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). The social, physical and administrative components of a job are considered resources if they aid in achieving work-related goals, reduce physical and mental distress caused by job demands and foster personal growth and development. Reducing job-related demands helps personnel concentrate on their work and minimizes ineffective moments, whereas enhancing job resources supports conserving power and maintaining employee engagement (Hakanen & Roodt, Citation2010). When sufficient job resources can be accessed, they can ensure a high engagement level and eventual positive outcomes by buffering the adverse impact of demands (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). Self-efficacy, faith, optimism and perseverance are several personal resources that serve as psychological assets to prevent burnout (Sweetman & Luthans, Citation2010). Moreover, unless they are excessive, job demands may not inherently be a problem because engagement involves a feelings-based conflict in the case of who feels uneasy with requirements but is motivated to meet them (Fong, Citation2006). Alternatively, having manageable quantities of tasks promotes job-related inspiration, as well as overcoming difficulties tends to promote a deeper understanding of purpose within the workplace (Tims et al., Citation2012).

2.1.2. The refined JD-R model

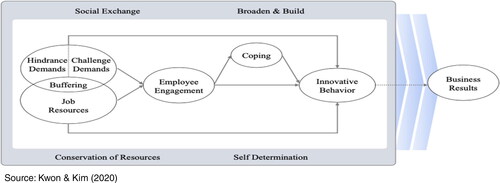

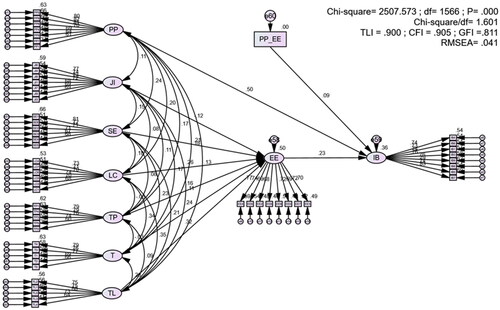

Kwon and Kim (Citation2020) have recently explored the JD-R framework, providing an in-depth explanation of how job demands and job resources influence innovative behavior via the mediating effect of employee engagement. According to their arguments, job resources can be categorized as belonging to the organization (organizational procedures and the society), the team (leadership designs and workplace network), or a single person (a person’s resources as well as job features). In contrast, work-related demands are usually associated with stress and are frequently a barrier. While some demands are considered as having the potential to improve expertise, career development and future growth, others are seen as impeding achieving objectives, workplace wellness and work-life balance. Whereas challenge demands might spark a positive drive, hindrance demands cause emotional suffering (Rich et al., Citation2010; van Woerkom et al., Citation2016). Depending on a person’s coping style and the buffering impact of available resources, prospective negative effects of job demands can get mitigated and possibly transformed into beneficial forces, according to Kwon and Kim (Citation2020). The refined JD-R model serves as the main theoretical foundation upon which the authors build the research model explaining how employee engagement affects innovative behaviors ().

2.1.3. Generation Z

Generation Z is defined as those who were born between 1996 and onwards (Dimock, Citation2019; Francis & Hoefel, Citation2018). Different generations behave differently according to their different personalities and behaviors such as work-life balance, work values, career patterns, leadership preferences and work meaningfulness (Brunetto et al., Citation2012; Lyons & Kuron, Citation2014; Weeks & Schaffert, Citation2019). Seemiller and Grace (Citation2019) found that Gen Z’s unique characteristics are affected by numerous factors such as political, technological development, social and economic situations. Gen Z’s expectations of diversity and personal values are more demanding than their predecessors (Francis & Hoefel, Citation2018; Gomez et al., Citation2018). They value happiness, financial security, relationships and meaningful work (Flippin, Citation2017; Seemiller & Grace, Citation2019). Hoole and Bonnema (Citation2015) claimed that there is no one-size-fits-all engagement strategy for all generations. Understanding past workplace behavior might not work best for Gen Z (Maloni et al., Citation2019). Because the literature on Gen Z’s work behavior is still minimal, this investigation can fill in that gap by broadening the understanding of employee engagement and innovative behavior from the perspective of Gen Z.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Transformational leadership and employee engagement

According to Zhu et al. (Citation2009), leaders are more likely to inspire strong leader-follower relationships when they show real attention and consideration for each follower. This enhances the followers’ sense of being part of the organization. This reciprocation may manifest in positive behaviors, including work engagement (Saks, Citation2006). So far, it has been stated that supervisors’ actions with individualized regard improve the characteristics of employee engagement at work. Intellectually fascinating supervisors promote an enjoyable working environment, resulting in a sense of work engagement (Avolio & Bass, Citation2002).

Transformational leadership can promote employees’ perceptions of their supervisors’ support. Individualized consideration may boost members’ readiness to show themselves completely in the workplace (being fully engaged at work) by fostering a sense of psychological safety (Liaw et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, managers may offer sufficient physical, emotional and psychological resources for team members to experiment with novel approaches to problems related to the job. This may increase the psychological connectivity of members and their job engagement (Bass & Bass Bernard, Citation1985; House & Shamir, Citation1993). Gen Z is self-reliant but still needs guidance and frequent feedback (Stillman & Stillman, Citation2017). Dwidienawati and Gandasari (Citation2018) claimed that Gen Z expects superiors whom they respect to work effectively. However, they do not like micromanagement (Dwidienawati & Syahchari, Citation2021). Transformational leadership becomes appropriate because this style provides strong leader-follower connectedness and commitment through leaders’ trust in followers and the role model in innovation. Nikolic (Citation2022) argued that transformational leadership has a positive impact on Gen Z so that they are more committed, creative and innovative. Based on the aforementioned literature, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

Hypothesis 1

(H1): Transformational leadership positively affects Gen Z’s employee engagement.

2.2.2. Learning climate and employee engagement

Workplace resources as well as encouragement have a significant effect on work engagement (Saks, Citation2006). The American Society for Training and Development found that an encouraging atmosphere for learning, exceptional instruction, assistance for supervisors and managers to enhance their training, resource allocation and interpersonal-relationship management skills are crucial for increasing employee engagement. Both Tseng (Citation2011) and Atak (Citation2011) claimed that acquiring organizational culture has a positive effect on employees’ commitment to the organization. Studies from Nimon et al. (Citation2011), following Sonnentag (Citation2003), pointed out that engaged employees exhibit more proactive behaviors and personal efforts.

Eldor and Harpaz (Citation2016) discovered that an atmosphere of work engagement is likely linked to the learning environment. Additionally, the learning environment fosters a sense of fulfillment among the staff by offering more chances to challenge, responsibilities and control. Employees who believe their organizations provide them opportunities to achieve their professional goals and personal growth tend to engage more in all workplace activities (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). Gen Z tends to look for instant success and requires organizations to provide them with personal development (Dwidienawati & Gandasari, Citation2018). Additionally, they want to get jobs that develop their skills (Nikolic, Citation2022). Based on these findings, the following hypothesis can be established:

Hypothesis 2

(H2): Learning climate positively affects Gen Z’s employee engagement.

2.2.3. Trust and employee engagement

Numerous studies have supported the positive relationship between trust and employee engagement (A. Chughtai et al., Citation2015; A. A. Chughtai & Buckley, Citation2013). Heyns and Rothmann (Citation2018) found that leaders can encourage employee engagement by fostering trust. According to Kaltiainen et al. (Citation2018), trustworthiness may boost engagement at work, especially in the context of forthcoming changes. Employees feel more confident in the organization’s ability to continue making a profit when they see that the top management possesses solid knowledge and capacity to boost the company’s development as well as efficiency through arriving at wise decisions and acting in a truthful and forthright way (Spreitzer & Mishra, Citation2002). In this circumstance, workers have to focus on their duties rather than other concerns, including the future of their place of employment (Mayer & Gavin, Citation2005). Because Gen Z is independent and entrepreneurial, superiors who know how to give them trust can empower Gen Z workers and stimulate creativity. Gen Z appreciates happiness, relationships and meaningful work (Flippin, Citation2017; Seemiller & Grace, Citation2019), so perceived trust in the workplace can contribute to Gen Z’s engagement and performance. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3

(H3): Trust positively affects Gen Z’s employee engagement.

2.2.4. Self-efficacy and employee engagement

Individuals with substantial degrees of self-efficacy tend to remain engaged in their job and expend greater effort to complete them (Bandura, Citation1977). Moreover, self-efficacy can potentially increase intrinsic motivation in a previously unsuccessful endeavor (Bandura, Citation1977; Wood & Bandura, Citation1989). Self-efficacy influences an individual’s choice to continue working on a task despite obstacles or difficulties. Individuals possessing optimism about their abilities are more likely to take the initiative and persist. Sweetman and Luthans (Citation2010) proposed that self-efficacy could determine how employees engaged in their jobs. People who exhibit a significant degree of self-efficacy are more likely to participate in their work, and overcome obstacles independently (Michael et al., Citation2011). Del Líbano et al. (Citation2012) affirmed a positive correlation between self-efficacy and work engagement. Concerned with intrinsic values, Gen Z is highly motivated if they can apply relevant skills to their jobs (Patel, Citation2017). Self-efficacy would have a substantial role in building Gen Z’s work engagement. Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4

(H4): Self-efficacy positively affects Gen Z’s employee engagement.

2.2.5. Job insecurity and employee engagement

When employees are concerned about the future of their employment, those with job insecurity find it difficult to fully engage at work. They will experience fewer beneficial outcomes (Wiesenfeld et al., Citation2001) and tend to be more anxious, angry and frustrated (Kiefer, Citation2005). Demerouti et al. (Citation2001) consider job demands as job aspects causing strain while Jiang (Citation2017, p. 256) defines job insecurity as ‘the perception that the future of one’s job is unstable or at risk’. Job insecurity, role ambiguity, or interpersonal conflict refer to a few hindrance demands that might adversely impact employees’ achievements and well-being (Cavanaugh et al., Citation2000). Mauno et al. (Citation2007) revealed that job insecurity has an adverse result on all aspects of work engagement. Job insecurity was also identified as one of the most widespread sources of workplace stress. It has been associated with lower levels of satisfaction with work, loyalty to the company, engagement at work, belief in the business and overall health (Cheng & Chan, Citation2008; Sverke et al., Citation2002). Numerous research found a correlation between a high level of job insecurity with fewer hours of effort and a smaller degree of workplace engagement (Greenhalgh, Citation1983; Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, Citation1984; Greenhalgh & Sutton, Citation1991). More recent studies also confirm the negative association between job insecurity and work engagement (Asfaw & Chang, Citation2019; Guo et al., Citation2021; Karatepe et al., Citation2020; Shin et al., Citation2020; H.-J. Wang et al., Citation2015). Patel (Citation2017) reported that Gen Z is highly concerned with employment security. Known as a cohort with a more entrepreneurial mindset than their predecessors, Gen Z also values stability as well (Annis, Citation2017). Organizations that can provide Gen Z employees job security have an advantage in attracting this cohort. On the other hand, job insecurity – typically known as a job challenge can adversely affect Gen Z’s work engagement. Based on the aforementioned discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 5

(H5): Job insecurity negatively affects Gen Z’s employee engagement.

2.2.6. Time pressure and employee engagement

People can manage certain levels of time pressure, as demonstrated in previous studies, which may drive individuals to put forth greater dedication while participating in enhancing their level of involvement at work (LePine et al., Citation2005; Reis et al., Citation2017; Schmitt et al., Citation2015). In contrast to hindrance demands that could lower motivation and efforts, challenge demands including time urgency are believed to have positive associations with motivation and valued outcomes (Lepine et al., Citation2005; van Woerkom et al., Citation2016). Rich et al. (Citation2010) found that challenge demands positively relate to employee engagement. According to Kühnel et al. (Citation2012), when employees have greater control over their work, ‘stress’ brought on by the day’s particular time pressure can be turned into motivating energy, which should then express itself in increased work engagement. Furthermore, time pressure is favorably related to work engagement because individuals see a positive relationship between their efforts and the possibility of effectively meeting this demand, leading to emotions of personal accomplishment. Born in the era of hi-tech development, Gen Z is familiar with multi-tasking by adopting technology and electronic devices in their jobs. Internet skills help Gen Z find solutions to their problems with ease (Nikolic, Citation2022). Time pressure, which is usually considered a job challenge can motivate Gen Z to exert their technology skills to achieve expected outcomes. Thus, time pressure can play a role in satisfying Gen Z and promoting their engagement. The following hypothesis can be established:

Hypothesis 6

(H6): Time pressure positively affects Gen Z’s employee engagement.

2.2.7. Employee engagement and innovative behavior

Huhtala and Parzefall (Citation2007) proposed that job-related happiness, including work engagement, improves worker innovation. Because it increases individual independent thinking (ie proactively involved, work behaviors oriented to approach), engagement can foster innovation (Frese & Fay, Citation2001; W. Kim et al., Citation2013; Shuck et al., Citation2017). According to Hakanen et al. (Citation2008), job engagement, personal initiative and workplace-unit innovativeness have positive reciprocal advantages. Engaged employees perform at their highest potential while adopting an inventive problem-solving method. Individuals engaged in their work have a positive feeling (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008), which permits them to study, assimilate and apply new knowledge and experiences (Fredrickson, Citation2001). According to Isen (Citation2001), beneficial impact fosters problem-solving, flexibility and inventiveness. People with positive affect possess an ability to perceive and activity, as well as more enthusiasm for engagement. S. Kim and Koo (Citation2017) confirm that employee engagement can be used to predict innovative behavior for hotel employees. Work engagement is also found as a motivational mechanism for innovative behavior (Ali et al., Citation2022; Wu & Wu, Citation2019). Additionally, Edelbroek et al. (Citation2019) confirmed that employee engagement partly mediated the relationship between transformational leadership and innovation. Kwon and Kim (Citation2020) proposed the mediating role of employee engagement in the relationships between various job demands, job resources and innovative behavior through the lens of the JD-R model. In their study, numerous job demands and job resources are identified such as transformational leadership, learning climate, trust, self-efficacy, job insecurity, time pressure, etc. However, they suggested that their refined conceptual framework needs more empirical evidence. Based on the aforementioned discussion, the following hypotheses are presented:

Hypothesis 7

(H7): Employee engagement positively influences Gen Z’s innovative behavior

Hypothesis 8

(H8): Employee engagement mediates the relationships of transformational leadership, learning climate, trust, self-efficacy, job insecurity and time pressure on Gen Z’s innovative behavior.

2.2.8. Proactive personality and the relationship between employee engagement and innovative behavior

People with strong proactive personalities are frequently described as having high levels of self-assurance, optimism, fulfillment and optimism, as well as a small amount of anxiety, desperation, fear, as well as other negative affective components (Li et al., Citation2017; Seibert et al., Citation1999; Thomas et al., Citation2010; Tolentino et al., Citation2014). They usually experience more positive feelings than those with fewer proactive characters (Randolph & Dahling, Citation2013). Highly proactive people are more inclined to engage in concept production, distribution and execution because they constantly seek ways to improve their existing conditions (Crant, Citation2000; Li et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, proactive people usually build social networks and stay current on professional advances, both related to innovative thinking (T. Y. Kim et al., Citation2010; Thompson, Citation2005). Gen Z is perceived as having an entrepreneurial mindset, even more entrepreneurial than Gen Y (Lanier, Citation2017; Magano et al., Citation2020). They do not hesitate to switch jobs or change anything if they don’t like it (Csiszárik-Kocsír & Garia-Fodor, Citation2018). It reflects their proactive personality in making important decisions. Employees can cope with job challenges by adopting their proactivity (Eldor, Citation2017) or sharing knowledge and feedback with others (S. Wang & Noe, Citation2010). They can adapt to changes, solve complicated problems and achieve innovation (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). When combined with their proactive personality, it is expected to see an increase in the effect of Gen Z’s engagement on their innovative behavior. In other words, when employee engagement is combined with a greater proactive personality, the relationship between employee engagement and innovative behavior is enhanced. Based on the aforementioned discussion, the next hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 9

(H9): Proactive personality moderates the relationship between employee engagement and innovative behavior.

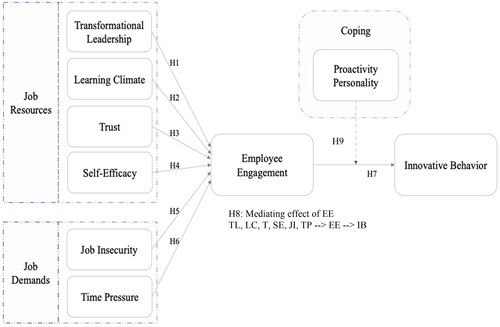

The research model is presented in .

3. Research method

3.1. Data collection and sampling

The quantitative method was employed to test variables affecting innovative behavior through the mediating effect of employee engagement and the moderating effect of proactive personality. The target population consists of Vietnamese employees who were born between 1997 and 2001. Non-probability sampling was applied with homogenous convenience sampling and snowball technique to reach the target population due to the advantages of low cost, accessibility and efficiency (Etikan, Citation2016; Stratton, Citation2021). The homogenous sampling was employed because only Gen Z employees were approached in this research, and this sampling method is more confident concerning generalizability than the conventional convenience sampling (Jager et al., Citation2017). A pilot test with 30 participants who share the same characteristics as the target population was conducted to identify any weaknesses in the questionnaire, checking for sentence and word use and thus improving the construct validity (Colton & Covert, Citation2007; Shadish et al., Citation2001). The survey was created using Google Forms and sent to potential participants via online channels such as emails, Messengers and Zalo – a free and popular over-the-top (OTT) application in Vietnam. Data collection conducted at different times (from April to June 2023) and from different participants in various businesses also helps minimize common method bias. To approach the target applicants, the researchers asked for and received permission from HR professionals to share the survey link with different organizations. The online form allowed receivers to do the survey with their consent and they can stop at any time. Participants were eligible to continue the survey only when they identified their birth year from 1997 and onwards, ensuring that only Gen Z employees were involved in this research. In addition, all sensitive information such as respondents’ names, departments and organizations is anonymous to encourage the participants’ valid answers and in turn, prevent the study from common method bias (Kock et al., Citation2021).

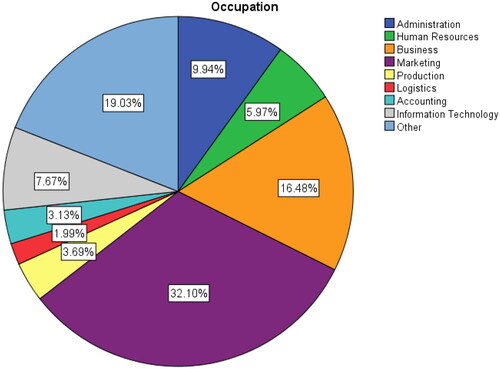

There are 352 valid responses among 377 received forms via online channels. Among them, there were 150 males (42.6%), 200 females (56.8%) and 2 people (0.6%) preferred not to identify their gender. presents the proportions of participants’ occupations.

The proportion of respondents working in marketing accounts for the highest percentage with 32.1%, followed by business (16.28%) and administration (9.94%). Employees working in information technology and human resources comprised a proportion of 7.67% and 5.97% respectively. Production, accounting and logistics were industries constituting the smaller contributions while up to 19.03% of participants selected ‘other occupations’ such as sales staff in retail stores or customer service staff in hospitality, etc. This sample reflects a homogeneity when all participants work as knowledge workers.

SPSS 24 and AMOS 20 were used to analyze the data. The reliability of the measurement scales was tested using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, followed by composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) to test the convergent and discriminant validity. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test how well the hypotheses fit the sample data. Finally, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to verify the hypotheses. The moderating effect of proactivity personality was confirmed with the Bootstrapping technique using macro PROCESS in SPSS.

3.2. Measurement of variables

The operationalization of the variables was designed with 69 measurement items, using the five-point Likert scale (from 1 – strong disagreement to 5 – strong agreement). The research constructs were adapted from previous studies. For example, employee engagement was measured with 9 items using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) developed by Schaufeli et al. (Citation2006). Innovative behavior was measured with 9 items developed by Janssen (Citation2000), and proactivity personality was measured by 10 indicators (Seibert et al., Citation1999). Appendix A presents the full measurement items of the study. To indicate good reliability values, Cronbach’s alpha of each variable should be greater than 0.7 and the variance extract greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2010).

After two rounds of reliability test conducted by SPSS, all items of transformational leadership (TL), learning climate (LC), trust (T) and time pressure (TP) and the corresponding Cronbach’s alpha satisfied the requirements (Cronbach’s alpha is greater than 0.7 and the Corrected Item-Total Correlation value is greater than 0.3). However, 3 items of Self-Efficacy (SE) should be removed to increase the reliability of the measurement (SE7, SE8, SE10). In a similar vein, 2 items of Job Insecurity (JI 2 and JI5), 1 item of Employee Engagement (EE1), 1 item of Innovative Behavior (IB2) and 3 items of Proactivity Personality (PP2, PP3 and PP1) were excluded because the Corrected Item-Total Correlation values of these indicators were lower than 0.3. summarizes the remaining number of items, the construct reliability and the sources of measurement.

Table 1. List of measurement scale.

3.3. Data analysis

3.3.1. Convergent and discriminant validity test

Hair et al. (Citation2010) proposed that the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) should be analyzed to check the convergent and discriminant validity. All composite reliability values were greater than 0.7 and the AVE was higher than 0.5, demonstrating that all scales converge. In addition, the square root of AVE was also higher than the correlations for latent variables. shows that the requirements for convergent and discriminant validity were satisfied.

Table 2. Discriminant validity test with Fornell-Larcker (1981)’s criterion.

3.3.2. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

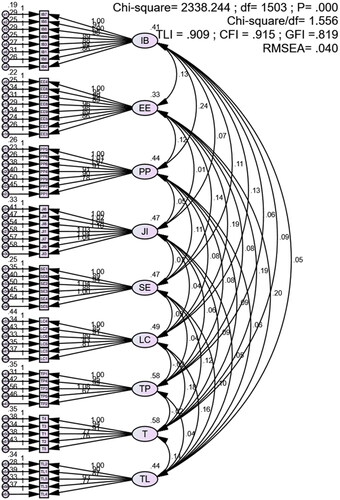

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a statistical method used in structural equation modeling (SEM). The structural model analysis indicated that the criteria for the goodness of fit index were met. Generally, GFI is good when its value is greater than 0.9 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). However, in exploratory studies, GFI that is greater than 0.8 is also acceptable (Baumgartner & Homburg, Citation1996; Doll et al., Citation1994). Based on the result, this research model fits the data and will be used for further analysis. The result is presented in as the following:

3.3.3. Hypothesis testing and results

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test the research hypotheses. The relationships of all variables and regression weights are presented in . displays the p-values of the hypotheses which are lower than 0.05. These findings indicate that transformational leadership, trust, self-efficacy, learning climate, time pressure and job insecurity relate to employee engagement and employee engagement influences innovative behavior.

Table 3. Regression results.

To investigate the impact of the independent factors on employee engagement and innovative behavior, we use the standardized regression weights as shown in .

Table 4. Standardized regression weights.

According to , among six factors affecting employee engagement, transformational leadership accounted for the highest contribution, followed by learning climate, trust, self-efficacy, time pressure and job insecurity. presents the R-squared values of employee engagement (0.499) and innovative behavior (0.360). It means that transformational leadership, learning climate, self-efficacy, trust, time pressure and job insecurity account for approximately 50% of the variance of employee engagement. Besides, all independent variables and employee engagement explain 36% of the variance of innovative behavior. Based on the aforementioned findings, we can conclude that employee engagement mediates the relationship between transformational leadership, learning climate, trust, self-efficacy, time pressure, job insecurity and innovative behavior.

Table 5. Squared multiple correlations.

3.3.4. Testing the moderating effect of proactivity personality

To test the moderator role of proactivity personality (H9), we used the macro PROCESS in SPSS to perform the bootstrapping technique with 5000 samples. summarizes the results as below.

Table 6. Results of moderating effect testing.

The p value of the variable Int_1 (F_EE x F_PP) is less than .05, confirming that proactivity personality moderates the impact of employee engagement on innovative behavior. The coefficient of 0.359 demonstrates that a higher level of proactive personality will result in a greater effect of employee engagement on innovative behavior. Therefore, H8 is supported.

4. Discussion

Based on the data analysis, several interpretations can be presented as follows. Firstly, all job-resource factors and job-demand factors proposed in the hypotheses relate to Gen Z’s work engagement and employee engagement positively relates to innovative behavior. Among six determinants of Gen Z’s engagement, transformational leadership has the highest positive effect, followed by learning climate, trust and self-efficacy. These results align with previous studies on how employee engagement contributes to innovative behavior (Al-Hawari et al., Citation2019; S. Kim & Koo, Citation2017; Wu & Wu, Citation2019). It can be said that Gen Z employees who highly engage in their work are more likely to express innovative behavior. As a result, organizations can predict Gen Z’s innovative behavior through engagement policies that encourage the exhibition of transformational leadership, promote a learning climate for employees’ growth, build mutual trust, foster self-efficacy, assign task forces with adequate time pressure and guarantee job security.

Secondly, between the two job-demand factors, time pressure positively relates to Gen Z’s engagement while job insecurity is negatively associated with it. These findings are consistent with previous research. Employees exhibit greater devotion when they are aware of time pressure (LePine et al., Citation2005; Reis et al., Citation2017; Schmitt et al., Citation2015). At a certain level, time pressure enables employees to stay focused and get their job done. Stress brought by particular time pressure can become a motivating source, increasing work engagement (Kühnel et al., Citation2012). Meanwhile, job insecurity negatively affects Gen Z’s engagement and innovative behavior. Regarding job insecurity, some scholars argued that employees who are concerned about their employment cannot be fully engaged at work (Kiefer, Citation2005; Wiesenfeld et al., Citation2001). Gen Z is known as the cohort that is highly concerned with employment security and seeks stability (Annis, Citation2017; Patel, Citation2017). Thus, our result indicates that job insecurity will negatively influence employee engagement, which is consistent with the existing literature (Cheng & Chan, Citation2008; Mauno et al., Citation2007; Sverke et al., Citation2002).

Finally, the result confirms that proactive personality moderates the relationship between employee engagement and innovative behavior. This finding is consistent with the extant literature in which highly proactive individuals are more inclined to engage in concept production, distribution and execution because they constantly seek ways to improve their existing conditions (Crant, Citation2000; Li et al., Citation2017; Tolentino et al., Citation2014). T. Y. Kim et al. (Citation2010) and Thompson (Citation2005) also stated that proactive people usually build social networks and stay current on professional advances, both related to work engagement and innovative thinking. As seen in Gen Z, the cohort who is spontaneous, creative and motivated, proactive personality is more emerging (Flippin, Citation2017; Seemiller & Grace, Citation2019). Consequently, it is expected that engaged employees will be more likely to exhibit innovative behavior if they are proactive individuals.

5. Research contribution and managerial implication

Our study contributed some benefits to the existing literature. Firstly, it provides the latest empirical evidence for the refined job demands-resources framework (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). The JD-R model is one among a few core theories to explain employee engagement, its determinants and outcomes (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). In our work, the results confirmed that transformational leadership, learning climate, self-efficacy, trust, time pressure and job insecurity influence Gen Z’s work engagement, and Gen Z’s engagement positively relates to innovative behavior. Secondly, we propose and verify the moderating effect of Gen Z’s proactive personality on the relationship between employee engagement and innovative behavior. Since Gen Z has different personality traits from other generations, taking this cohort’s unique characteristics into account can help scholars better predict Gen Z’s work behavior. Thirdly, the result enhanced the understanding of Generation Z across cultures by studying Generation Z in Vietnam – a developing country in Southeast Asia, filling the gap in the literature in which most studies on Gen Z were conducted in the United States (Scholz, Citation2019).

The findings indicated that employees demonstrate innovative behavior when they engage in their work. Practitioners may think of the design and implementation of HR policies that develop employee engagement and in turn encourage their employees’ innovative behavior. According to our findings, transformational leadership, learning climate and trust are among the top determinants of Gen Z’s work engagement. To foster Gen Z’s innovative behavior through their engagement, organizations should design and implement policies that support transformational leadership, develop employees’ self-efficacy and gain employees’ trust. Organizations’ leaders can help employees develop their strengths and articulate a compelling vision to stimulate employee engagement. In addition, receiving trust from the managers and being confident in one’s ability will enable Gen Z to demonstrate creativity and act more innovative, resulting in better performance. Last but not least, the assurance of job security from employers will keep Gen Z engaged in their jobs and devoted to innovation.

6. Limitations and suggestions for future research

Our study aims to identify the determinants of employee engagement and innovative behavior by adapting the refined JD-R model from Kwon and Kim (Citation2020). Although 352 Vietnamese employees participated in the research, the results should not be applied to the entire Generation Z. In addition, since Gen Z has placed their very first steps to work, their experience of work engagement and innovative behavior will certainly evolve. Their understanding and answers to the core constructs in the research might change over time, depending on how much experience is accumulated. Future research should collect data from Gen Zers across countries and cultures to expand understanding of engagement theory on this generation.

Although our findings point out the greatest impact of transformational leadership on employee engagement, other leadership styles should be explored in the future to determine which one might work best with Gen Z. The current literature recognizes a positive relationship between ethical leadership and employee engagement (Alam et al., Citation2021; Engelbrecht et al., Citation2017), or the association between servant leadership and employee engagement (Canavesi & Minelli, Citation2022; Zeeshan et al., Citation2021). Scholars also found that ethical leadership or servant leadership is positive for employees’ well-being and performance. For example, Ruiz-Palomino et al. (Citation2023) highlighted the role of ethical leadership on employee performance. The frontline employees become more customer-oriented when they perceive ethical leadership exercised in the organizations. Ethical leadership also influences employees’ ethical behavior (Ruiz et al., Citation2011), which in turn yields ethical innovative behavior. Moreover, servant leadership can enhance the affective well-being of employees both directly and by elevating their personal growth (Jiménez-Estévez et al., Citation2023), a condition that leads to employee engagement and innovation. Since the current understanding of Gen Z’s work behavior is still limited, we need more research to explore the mechanism of employee engagement and to foster Gen Z’s innovative behavior.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The research data will be shared upon reasonable request according to the journal’s policies.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Minh Tan Nguyen

Mr. Minh Tan Nguyen is a lecturer at the School of Business – International University – Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City. He has more than ten years teaching numerous courses in Business and Management. He earned his MBA with a concentration on Human Resources Management from the University of Houston-Clear Lake in the U.S.A. and is currently a PhD candidate in Human Resource and Organization Development. He is interested in researching topics related to HRM, HRD, and organizational behavior.

Pawinee Petchsawang

Assistant Professor Dr. Pawinee Petchsawang works at the Graduate School of Human Resource Development – National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA) in Bangkok, Thailand. She got a Ph.D. in Human Resource Development from the University of Tennessee, U.S.A. Her research interests include HRM, HRD, workplace spirituality, and mindfulness.

References

- Alam, I., Singh, J., & Islam, M. (2021). Does supportive supervisor complement the effect of ethical leadership on employee engagement? Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1978371

- Al-Hawari, A., Bani-Melhem, S., & Shamsudin, M. (2019). Determinants of frontline employee service innovative behavior: The moderating role of co-worker socializing and service climate. Management Research Review, 42(9), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-07-2018-0266

- Ali, H., Li, M., & Qiu, X. (2022). Employee engagement and innovative work behavior among Chinese millennials: Mediating and moderating role of work-life balance and psychological empowerment. Frontiers Psychology, 13.

- Annis, J. (2017). Gen Z is willing to trade hard work for job security. Reno Gazette Journal. https://www.rgj.com/story/money/business/2017/03/20/annis-gen-z-willing-trade-hard-work-job-security/99431454/

- Atak, M. (2011). A research on the relation between organizational commitment and learning organization. African Journal of Business Management, 5(14), 5612.

- Asfaw, A., & Chang, C.-C. (2019). The association between job insecurity and engagement of employees at work. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 34(2), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2019.1600409

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (Eds.) (2002). Developing potential across a full range of leadership: Cases on transactional and transformational leadership. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., & Fletcher, L. (2017). The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: A narrative synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12077

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., de Boer, E., & Schaufeli, W. (2003). Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(2), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00030-1

- Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

- Barrick, M. R., Thurgood, G. R., Smith, T. A., & Courtright, S. H. (2015). Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0227

- Bass, B. M., & Bass Bernard, M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

- Baumgartner, H., & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(95)00038-0

- Berkup, S. B. (2014). Working with generations X and Y in generation Z period: Management of different generations in business life. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(19), 218. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n19p218

- Brunetto, Y., Teo, S. T. T., Shacklock, K., & Farr-Wharton, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well-being and engagement: Explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00198.x

- Borg, I., & Elizur, D. (1992). Job insecurity: Correlates, moderators and measurement. International Journal of Manpower, 13(2), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437729210010210

- Canavesi, A., & Minelli, E. (2022). Servant leadership and employee engagement: A qualitative study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 34(4), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-021-09389-9

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

- Cheng, G. H. L., & Chan, D. K. ‐S. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta‐analytic review. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 272–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00312.x

- Chughtai, A., Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: The role of trust in supervisor. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2126-7

- Chughtai, A. A., & Buckley, F. (2013). Exploring the impact of trust on research scientists’ work engagement: Evidence from Irish science research centres. Personnel Review, 42(4), 396–421. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2011-0097

- Colton, D., & Covert, R. W. (2007). Designing and constructing instruments for social research and evaluation (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600304

- Csiszárik-Kocsír, H., & Garia-Fodor, M. (2018). Motivation analysing and preference system of choosing a workplace as segmentation criteria based on a country wide research result focus on generation of Z. On-Line Journal Modelling the New Europe, 27(27), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.24193/OJMNE.2018.27.03

- Del Líbano, M., Llorens, S., Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). About the dark and bright sides of self-efficacy: Workaholism and work engagement. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 688–701. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n2.38883

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Dimock, M. (2019). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center, 17(1), 1–7.

- Doll, W. J., Xia, W., & Torkzadeh, G. (1994). A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quarterly, 18(4), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.2307/249524

- Dolot, A. (2018). The characteristics of Generation Z. E-mentor, 74(74), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.15219/em74.1351

- Dwidienawati, D., & Gandasari, D. (2018). Understanding Indonesia’s generation Z. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(3), 245–253.

- Dwidienawati, D., & Syahchari, D. (2021). Effective leadership style for generation Z. In Proceedings of the 4th European International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 894-902. IEOM Society.

- Edelbroek, R., Peters, P., & Blomme, R. (2019). Engaging in open innovation: The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between transformational and transactional leadership and the quality of the open innovation process as perceived by employees. Journal of General Management, 45(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306307019844633

- Eldor, L. (2017). Looking on the bright side: The positive role of organizational politics in the relationship between employee engagement and performance at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(2), 233–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12090

- Eldor, L., & Harpaz, I. (2016). A process model of employee engagement: The learning climate and its relationship with extra‐role performance behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2037

- Engelbrecht, A. S., Heine, G., & Mahembe, B. (2017). Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(3), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2015-0237

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Flippin, C. (2017). Generation Z in the workplace: Helping the newest generation in the workforce build successful working relationships and career paths. Candace Steele Flippin.

- Fong, C. T. (2006). The effects of emotional ambivalence on creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 1016–1030. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22798182

- Francis, T., & Hoefel, F. (2018, November). ‘True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

- Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). 4. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 133–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

- Goh, E., & Okumus, F. (2020). Avoiding the hospitality workforce bubble: Strategies to attract and retain generation Z talent in the hospitality workforce. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100603

- Gomez, K., Mawhinney, T., & Betts, K. (2018). Welcome to Generation Z. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/consumer-business/welcome-to-gen-z.pdf

- Greenhalgh, L. (1983). Organizational decline. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 2(23), l–276.

- Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. The Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.2307/258284

- Greenhalgh, L., & Sutton, R. (1991). Job insecurity and organizational effectiveness. Job insecurity: Coping with jobs at risk. Sage.

- Guo, J., Qiu, Y., & Gan, Y. (2021). Workplace incivility and work engagement: The mediating role of job insecurity and the moderating role of self-perceived employability. Managerial and Decision Economics, 43(1), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3377

- Haddouche, H., & Salomone, C. (2018). Generation Z and the tourist experience: Tourist stories and use of social networks. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0059

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hakanen, J. J., Perhoniemi, R., & Toppinen-Tanner, S. (2008). Positive gain spirals at work: From job resources to work engagement, personal initiative, and work-unit innovativeness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.003

- Hakanen, J. J., & Roodt, G. (2010). Using the job demands-resources model to predict engagement: Analysing a conceptual model. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, 2(1), 85–101.

- Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work Engagement. Work & Stress, 22(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432

- Heyns, M., & Rothmann, S. (2018). Volitional trust, autonomy satisfaction, and engagement at work. Psychological Reports, 121(1), 112–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117718555

- Hoole, C., & Bonnema, J. (2015). Work engagement and meaningful work across generational cohort. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v13i1.681

- House, R. J., & Shamir, B. (1993). Toward the integration of transformational, charismatic, and visionary theories. Academic Press.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huhtala, H., & Parzefall, M. R. (2007). A review of employee well‐being and innovativeness: An opportunity for a mutual benefit. Creativity and Innovation Management, 16(3), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2007.00442.x

- Isen, A. M. (2001). An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: Theoretical issues with practical implications. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1102_01

- Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples: Developmental methodology. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12296

- Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort‐reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900167038

- Jiang, L. (2017). Perception of and reactions to job insecurity: The buffering effect of secure attachment. Work & Stress, 31(3), 256–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1305005

- Jiménez-Estévez, P., Yáñez-Araque, B., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2023). Personal growth or servant leader: What do hotel employees need most to be affectively well amidst the turbulent COVID-19 times? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122410

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287’

- Kaltiainen, J., Lipponen, J., & Petrou, P. (2018). Dynamics of trust and fairness during organizational change: Implications for job crafting and work engagement. In M. Vakola & P. Petrou (Eds.), Organizational change (pp. 90–101). Routledge.

- Kanter, R. M. (1983). The change masters New York–Simon and Schuster. KanterThe Change Masters. Free Press.

- Karatepe, O., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Hassannia, R. (2020). Job insecurity, work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ non-green and nonattendance behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102472

- Kiefer, T. (2005). Feeling bad: Antecedents and consequences of negative emotions in ongoing change. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(8), 875–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.339

- Kim, S., & Koo, W. (2017). Linking LMX, engagement, innovative behavior, and job performance in hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(12), 3044–3062. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2016-0319

- Kim, T. Y., Hon, A. H., & Lee, D. R. (2010). Proactive personality and employee creativity: The effects of job creativity requirement and supervisor support for creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 22(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410903579536

- Kim, W., Kolb, J. A., & Kim, T. (2013). The relationship between work engagement and performance: A review of empirical literature and a proposed research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 12(3), 248–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484312461635

- Kock, F., Berbekova, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Management, 86, 104330.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330

- Kruse, K. (2012, June, 22). What is employee engagement?. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinkruse/2012/06/22/employee-engagement-what-and-why/?sh=6d2296b97f37

- Kühnel, J., Sonnentag, S., & Bledow, R. (2012). Resources and time pressure as day‐level antecedents of work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85(1), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02022.x

- Kwon, K., & Kim, T. (2020). An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100704

- Lanier, K. (2017). 5 things HR professionals need to know about Generation Z. Strategic HR Review, 16(6), 288–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-08-2017-0051

- Larasati, D. P., & Hasanati, N. (2019, March). The effects of work-life balance towards employee engagement in the millennial generation. In 4th ASEAN Conference on Psychology, Counselling, and Humanities (ACPCH 2018) (pp. 390–394). Atlantis Press.

- Lee, C. C., Aravamudhan, V., Roback, T., Lim, H. S., & Ruane, S. G. (2021). Factors impacting work engagement of Gen Z employees: A regression analysis. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 18(3), 147–159.

- LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.18803921

- Leslie, B., Anderson, C., Bickham, C., Horman, J., Overly, A., & Gentry, C. (2021). Generation Z perceptions of a positive workplace environment. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 33, 1–17.

- Li, M., Wang, Z., Gao, J., & You, X. (2017). Proactive personality and job satisfaction: The mediating effects of self-efficacy and work engagement in teachers. Current Psychology, 36(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9383-1

- Liaw, Y. J., Chi, N. W., & Chuang, A. (2010). Examining the mechanisms linking transformational leadership, employee customer orientation, and service performance: The mediating roles of perceived supervisor and coworker support. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9145-x

- Lu, W., & Miller, L. (2018). Gen Z is set to outnumber Millennials within a year. BNNBloomberg. https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/gen-z-is-set-to-outnumber-millennials-within-a-year-1.1125841

- Lyons, S., & Kuron, L. (2014). Generational differences in the workplace: A review of the evidence and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), S139–S157. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1913

- Magano, J., Silva, C., Figueiredo, C., Vitória, A., Nogueira, T., & Pimenta Dinis, M. A. (2020). Generation Z: Fitting project management soft skills competencies—A mixed-method approach. Education Sciences, 10(7), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070187

- Maloni, M., Hiatt, M., & Campbell, S. (2019). Understanding the work values of Gen Z business students. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(3), 100320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100320

- Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (2003). Demonstrating the value of an organization’s learning culture: The dimensions of the learning organization questionnaire. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5(2), 132–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422303005002002

- Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(1), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.09.002

- Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. (2005). Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 874–888. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.18803928

- Michael, L. H., Hou, S. T., & Fan, H. L. (2011). Creative self‐efficacy and innovative behavior in a service setting: Optimism as a moderator. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 45(4), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2011.tb01430.x

- Musgrove, C., E. Ellinger, A., & D. Ellinger, A. (2014). Examining the influence of strategic profit emphases on employee engagement and service climate. Journal of Workplace Learning, 26(3/4), 152–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-08-2013-0057

- Nikolic, K. (2022). Different leadership styles and their impact on Generation Z employees’ motivation (Publication No. 1921002) [Master’s thesis]. Modul University.

- Nimon, K., Zigarmi, D., Houson, D., Witt, D., & Diehl, J. (2011). The work cognition inventory: Initial evidence of construct validity. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(1), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20064

- Patel, D. (2017). 8 Ways Generation Z will differ from millennials in the workplace. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/deeppatel/2017/09/21/8-ways-generation-z-will-differ-from-millennials-in-the-workplace/#6ea456776e5e

- Ployhart, R. E. (2015). Strategic organizational behavior (STROBE): The missing voice in the strategic human capital conversation. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2014.0145

- Putrevu, S., & Ratchford, B. (1997). A model of search behavior with an application to grocery shopping. Journal of Retailing, 73(4), 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90030-0

- Randolph, K. L., & Dahling, J. J. (2013). Interactive effects of proactive personality and display rules on emotional labor in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(12), 2350–2359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12184

- Reis, D., Hoppe, A., Arndt, C., & Lischetzke, T. (2017). Time pressure with state vigor and state absorption: Are they non-linearly related? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1224232

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51468988

- Ruiz, P., Ruiz, C., & Martinez, R. (2011). The cascading effect of top management’s ethical leadership: Supervisors or other lower-hierarchical level individuals? African Journal of Business Management, 5(12), 4755–4764. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM10.718

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Linuesa-Langreo, J., Rincón-Ornelas, R. M., & Martinez-Ruiz, M. P. (2023). Putting the customer at the center: Does store managers’ ethical leadership make a difference in authentic customer orientation? Academia Revista Latinoamericana De Administración, 36(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-11-2022-0201

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690169

- Saks, A. M. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 6(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-06-2018-0034

- Sameer, Y. M. (2018). Innovative behavior and psychological capital: Does positivity make any difference? Journal of Economics and Management, 32, 75–101. https://doi.org/10.22367/jem.2018.32.06

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Schmitt, A., Ohly, S., & Kleespies, N. (2015). Time pressure promotes work engagement. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000119

- Scholz, C. (2019). The Generations Z in Europe – An introduction. In C. Scholz & A. Rennig (Eds.), Generations Z in Europe (the changing context of managing people) (pp. 3–31). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Schroth, H. (2019). Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace? California Management Review, 61(3), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619841006

- Schwarzer, R., Born, A., Iwawaki, S., Lee, Y.-M., et al. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the Chinese, Indonesian, Japanese, and Korean versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient, 40(1), 1–13.

- Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2019). Generation Z: A century in the Making. Routledge.

- Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2001). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

- Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. (2004). The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? Journal of Management, 30(6), 933–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.007

- Shin, Y., Hur, W.-M., & Choi, W.-H. (2020). Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(11), 1417–1438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1407352

- Shuck, B., Adelson, J. L., & Reio, T. G. (2017). The employee engagement scale: Initial evidence for construct validity and implications for theory and practice. Human Resource Management, 56(6), 953–977. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21811

- Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518–528. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518

- Spreitzer, G. M., & Mishra, A. K. (2002). To stay or to go: Voluntary survivor turnover following an organizational downsizing. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 707–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.166

- Stillman, D., & Stillman, J. (2017). Gen Z @ work: How the next generation transforming the workplace. HarperCollins.

- Stratton, S. J. (2021). Population research: Convenience sampling strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36(4), 373–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000649

- Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.7.3.242

- Sweetman, D., & Luthans, F. (2010). The power of positive psychology: Psychological capital and work engagement. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, 54, 68.

- Thomas, J. P., Whitman, D. S., & Viswesvaran, C. (2010). Employee proactivity in organizations: A comparative meta‐analysis of emergent proactive constructs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317910X502359

- Thompson, J. A. (2005). Proactive personality and job performance: A social capital perspective. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.1011

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Tolentino, L. R., Garcia, P. R. J. M., Lu, V. N., Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Plewa, C. (2014). Career adaptation: The relation of adaptability to goal orientation, proactive personality, and career optimism. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.11.004

- Tseng, C. C. (2011). The influence of strategic learning practices on employee commitment. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 3(1), 5–23.

- Turek, D., & Wojtczuk-Turek, A. (2017). How destructive social aspects inhibit innovation in the organisation. International Journal of Contemporary Management, 16(2), 267–294.

- Van Woerkom, M., Bakker, A. B., & Nishii, L. H. (2016). Accumulative job demands and support for strength use: Fine-tuning the job demands-resources model using conservation of resources theory. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000033

- Wang, H.-J., Lu, C.-Q., & Siu, O.-L. (2015). Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1249–1258. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038330

- Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.10.001

- Weeks, K., & Schaffert, C. (2019). Generational differences in definitions of meaningful work: A mixed methods study. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(4), 1045–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3621-4

- West, M. A., & Farr, J. L. (Eds.). (1990). Innovation and creativity at work: Psychological and organizational strategies. John Wiley.

- Wiesenfeld, B. M., Brockner, J., Petzall, B., Wolf, R., & Bailey, J. (2001). Stress and coping among layoff survivors: A self-affirmation analysis. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 14(1), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800108248346

- Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. The Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361–384. https://doi.org/10.2307/258173

- Wu, T.-J., & Wu, Y. J. (2019). Innovative work behaviors, employee engagement, and surface acting: A delineation of supervisor-employee emotional contagion effects. Management Decision, 57(11), 3200–3216. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-02-2018-0196

- Yang, J., & Mossholder, K. W. (2010). Examining the effects of trust in leaders: A bases-and-foci approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.004

- Yuan, F., & Woodman, R. W. (2010). Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(2), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.49388995

- Zeeshan, S., Ng, S. I., Ho, J. A., & Jantan, A. H. (2021). Assessing the impact of servant leadership on employee engagement through the mediating role of self-efficacy in the Pakistani banking sector. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1963029

- Zhu, W., Avolio, B. J., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2009). Moderating role of follower characteristics with transformational leadership and follower work engagement. Group & Organization Management, 34(5), 590–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601108331242

Appendix A

Table A1. Measurement items for the survey.