Abstract

This study aims to determine how payment disturbances in managers’ earlier entrepreneurial practices (PDMs) predict corporate default. Classical financial ratios have often failed to predict the default of micro-, small- and medium-sized firms with high accuracy, and therefore, the extant literature has been focused on searching novel non-financial predictors. In this study, an integrational theoretical framework about PDMs in corporate default prediction is created and respective hypotheses postulated. The empirical part of the paper applies the population of Estonian defaulted and non-defaulted firms with three different prediction methods, while the predictors included three variables portraying PDMs and four classical financial ratios. The results indicate that PDMs lead to more accurate predictions of corporate defaults than financial ratios do. Among the specific variables, the average tendency of earlier disturbances was the most accurate, followed by the maximum and frequency tendencies. Therefore, the prevalence of payment behaviour issues by means of size and duration is more common in the entrepreneurial history of managers of defaulted firms than in that of non-defaulted firms. Additionally, the role of size, age, business-to-business, international orientation, and serial entrepreneurship contexts on the results is outlined. By introducing novel variables, this study is valuable for corporate default prediction in practice, especially when financial variables for respective purpose are absent or when they fail to signal the forthcoming default.

JEL CLASSIFICATION:

1. Introduction

Although the literature stream of failure prediction is already more than half a century old, originating from the early contributions of Beaver (Citation1966) and Altman (Citation1968) who applied financial ratios, the area is still in constant development. This is especially visible in the micro-, small-, and medium-sized firms’ (SMEs’) domain, as the usual predictors by means of financial ratios are not fully suitable in that context. Still, these firms form the overwhelming majority of corporate entities. According to Eurostat (Citation2022), based on the number of workers, micro firms alone constituted 94% of the European firm population in 2019. In addition, except for novice entrepreneurs, it is quite usual for a manager to be or have been involved in multiple companies, being noted as serial and portfolio entrepreneurs throughout the literature. For instance, Plehn-Dujowich (Citation2010) noted that the share of serial entrepreneurs was up to 30% in various countries, while Süsi and Lukason (Citation2019) found that more than half of the Estonian firm population had managers simultaneously involved in several companies. Thus, the fact that a manager running a specific firm has an earlier entrepreneurial background is potentially frequent.

This study builds on a recent literature review by Ciampi et al. (Citation2021), which noted that the search for novel qualitative variables for failure prediction in the SME segment is among the most important future avenues of research. To date, the usage of non-financial variables for failure prediction is very infrequent when compared to financial ratios. Still, the failure prediction models of SMEs based on financial ratios have often been subject to remarkable classification errors (Altman et al., Citation2017; Laitinen et al., Citation2023). The main novelty of the study is, that as there are no profound studies using payment disturbances in managers’ earlier entrepreneurial practices (PDMs) to predict corporate default, this research aims to fulfil that gap. The latter is especially topical in the circumstances where no (up to date) financial information is available about the firm, which has been noted to be especially topical in the case of firms in a poor financial status (Lukason and Camacho-Miñano, Citation2021), and leaves non-financial information as the only possible instrument to be used in failure prediction.

As no specific theory interconnects PDMs with the onset of corporate default, a novel theoretical framework has to be created for the respective purpose. In the context of the general theoretical knowledge, this study builds on upper echelons, learning from failure, and serial entrepreneurship perspectives. The integration of the latter theoretical streams enables to outline, why managerial behaviour can be recurrent from one firm to another. The general theoretical knowledge is supplemented by specific explanations from the payment behaviour, liquidity management, disclosure, and compliance domains, which enable to explain, why specifically payment difficulties might be recurrent in the managerial careers. The potential superiority of PDMs over financial ratios in predicting corporate default is explained with the help of theoretical and empirical literature on firm failure processes, annual report (non-)submission, and failure prediction. Therefore, unlike most of the studies that focus on predicting firm failure, which mainly concentrate on methodological improvements (e.g. introducing new prediction tools to achieve high accuracies with classical financial ratios), this study has both theoretical (i.e. the creation of an integrational theoretical concept) and empirical (i.e. the introduction of a new type of non-financial variables for failure prediction) novelties.

This study aims to determine how payment disturbances in managers’ earlier entrepreneurial practices (PDMs) predict corporate default. In order to achieve that, the study answers two research questions. The first research question is: which variables reflecting PDMs are useful in predicting corporate default? For this purpose, the individual values of various proxies of earlier payment disturbances are assessed by using marginal effects from the logistic regression models. This is conducted for both the whole population of firms and different sub-populations created based on firm-level contexts, such as size, age, serial and novice entrepreneurship, business-to-business focus, and international orientation. The latter contextual analysis enables to understand how the results might vary for different types of firms. In addition, the individual prediction accuracies of these variables are outlined from respective logistic regression models.

In this study, payment default is seen as an unpaid debt due with a permanent nature (i.e. not disappearing after its emergence), and the exact onset time of the default is considered. Payment disturbance, in turn, is unpaid debt due with at least of temporary origin, that is, its future development into permanent form is not additionally considered, while in the dataset, the overwhelming majority of temporary unpaid debt due does not develop into a permanent form. While much of the extant research is based on more severe failure definitions (e.g. declaration of bankruptcy, exit of an indebted firm), this paper aims to create an early warning system to predict the onset of a payment default. The latter would potentially enable to avoid more credit losses preventively. The second research question is: do variables reflecting PDMs lead to more accurate prediction of corporate default than financial ratios? For this purpose, the prediction accuracies of the models based on earlier payment disturbance variables are compared against models applying classical financial ratios, while three different prediction methods are implemented. Therefore, this study strives to be the first attempt to systematically outline the potential of PDMs in predicting corporate default, while the empirical findings of this research corroborate such usefulness.

The structure of this study follows a classical outline. In the subsequent literature review, the foundations of the postulated hypotheses are set and an integrative perspective from both relevant theoretical and empirical literature is provided. The literature review is followed by the study design section, which explains the unique dataset, variables created, and methods with their application peculiarities. The latter is succeeded by the presentation of analysis results, after which the discussion of findings in relation to the theoretical framework is provided. Finally, the paper ends with conclusive remarks, including practical implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

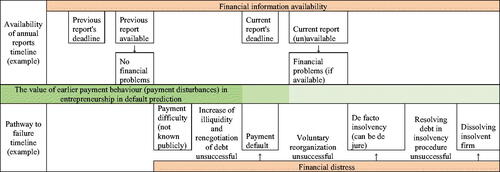

The literature review of this paper consists of two main sections. The first section looks at the main theoretical basis for interconnecting payment behaviour in firms ran by managers in their earlier entrepreneurial practices with the onset of payment default in firms run by them in the future. As no specific theory is available for the latter, we derive the theoretical expectations based on integrating different streams of literature. The general foundations for the narrative provided emerge from merging the upper echelons theory and the serial entrepreneurship and learning from failure theories. The arguments in these theories lead to a general conclusion that the behaviour of managers can be recurrent from one firm to another. The latter approach is supplemented by the context-specific literature to position it specifically in the research domain of payment disturbances. Based on the integration of various literature streams (e.g. reflecting poor financial management skills of entrepreneurs, recurrent poor liquidity management of a firm, recurrent serial non-compliance with financial reporting regulations associated with financial distress), the main arguments behind the recurrence of payment behaviour in managerial careers is outlined. While the first section leads to a conclusion about the value of PDMs in predicting corporate default, the second section looks at the main theoretical basis why financial ratios might fail to signal corporate default. Various concepts are used to explain the latter, such as the existence of different failure processes, modest accuracies of the failure prediction models of SMEs, decrease in the prediction accuracies for less severe failure definitions and delays of financial reports in the case of distressed firms. The summary of the integrative theoretical framework used in this study has been depicted in .

Table 1. Theoretical framework of the study.

The debate about the effects of corporate governance on firm performance has been ongoing for decades, and evidence from various countries shows the impact of the former on the latter (Love Citation2011). This debate has its roots in the theory of upper echelons by Hambrick and Mason (Citation1984), which postulates that managers’ (i.e. the upper echelons’) characteristics (psychological and observable) affect firm performance. Among observable characteristics, previous experience has been marked as pivotal. Indeed, the upper echelons theory also posits that the effect of managers’ characteristics on performance is moderated by a firm’s strategy (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984). However, in the SME segment, where corporate management, control, and ownership layers often overlap (Huse, Citation2005; Uhlaner et al., Citation2007), the upper echelons theory could be especially valid. Therefore, in one of the earliest studies about the firm failure processes by Argenti (Citation1976), the ‘one-man rule’ was outlined as a major cause of firm failure. In addition, the bulk of empirical research applying upper echelons theory to study corporate collapse causes (e.g. Mayr et al., Citation2021; Ooghe & de Prijcker, Citation2008) or failure risk (e.g. Ciampi, Citation2015; Süsi & Lukason, Citation2019) has found that managerial experience plays a significant role.

Another important theoretical foundation regarding whether earlier entrepreneurship practices matter originates from the often complementary literature streams of serial entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial learning from failure. In an extensive theorization about the routes of entrepreneurial learning, Politis (Citation2005) remarked that only a certain type of earlier failure can lead to future success, leading to the argument that consecutive failures are usual, as entrepreneurs have not succeeded in learning from their experience. The empirically validated model of Nielsen and Sarasvathy (Citation2016) extends the learning route to the serial entrepreneurship context. Namely, after the success or failure of the first company, an entrepreneur will first decide whether to start a new company, while when a new entrepreneurial journey is taken, it can be either a success or a failure. Irrespective of the outcome of the first venturing process, the failure of the second attempt is attributed to overconfidence, while success to the right leveraging of human and social capital (Nielsen & Sarasvathy, Citation2016). Indeed, the learning process can be more complex and multifaceted than in the latter example (Lattacher & Wdowiak, Citation2020), being at least partly dependent on the meaning of ‘entrepreneurial failure’ (Jenkins & McKelvie, Citation2016). While serial entrepreneurship literature views consecutive entrepreneurial endeavours, these can also coincide in the timeline being classified as portfolio entrepreneurship, while still a bulk of the firm population is composed of novice or first-time entrepreneurs as well (Dabić et al., Citation2021). Logically linking to the theoretical explanations, the multifaceted empirical literature on learning from failure (e.g. Frankish et al., Citation2013, Walsh & Cunningham, Citation2017, Boso et al., Citation2019) and serial entrepreneurship (e.g. Chen, Citation2013, Toft-Kehler et al., Citation2014, Lafontaine & Shaw, Citation2016) have led to largely dissonant and nonlinear results on whether learning occurs or not.

The general theoretical background of study (see also ) enables to assume the following. The behaviour of firms, especially in the SME sector, is largely dependent on the characteristics of managers based on the upper echelons theory. In the case of ‘one-man rule’, managers are not subject to additional control, as different corporate governance layers overlap. According to the serial entrepreneurship concept managers are likely to establish new companies, even in the case their previous entrepreneurial endeavour was a failure. In addition, based on the non-learning from failure concept, poor performance can also occur in the subsequent firm. Therefore, sequential failures might be rather common in entrepreneurship, meaning that the same managers make the same mistakes again.

There are several strands of literature that contextualize the general theoretical foundations outlined earlier specifically to the payment behaviour domain. First, the repetitive nature of poor liquidity management can be deduced from previous studies. Mramor and Valentincic (Citation2003) indicate that poor liquidity management by means of the number of days with insufficient cash balances during previous years is a useful predictor of the same phenomenon in the future. Their study showed that firms with sufficient liquidity almost did not witness the same problem in the past, while the bulk of their illiquid counterparts witnessed the same issue previously. Ekanem (Citation2010) states that liquidity management in small firms largely relies on the previous experience of managers, the lack of which is usually correlated with poor financial management skills. In this line, several studies have documented that managers with earlier bankruptcy experience are more likely to take risks than their counterparts being previously successful (e.g. Gopalan et al., Citation2021; Ivanova et al., Citation2023). Therefore, from liquidity management literature, it can be deduced that managers’ earlier inadequate liquidity management practices can be repetitive in the future.

The second stream of literature linked to the causes of poor liquidity management concerns the general financial management skills of managers. Already the earlier empirical research on corporate failure causes indicates that poor financial management skills are one of the major precedents for bankruptcy (e.g. Baldwin et al., Citation1997; Hall, Citation1992). The latter issue seems to be rather universal, extending into the managers’ personal life as well. For instance, Kallunki and Pyykkö (Citation2013) showed by relying on overconfidence and over-optimism literature that firm failure risk and managers’ earlier personal payment defaults are correlated. A similar result was obtained by Back (Citation2005), who indicated that managers’ earlier personal payment disturbances are a significant predictor of firms’ payment delays. Therefore, the strand of literature linking managerial financial management skills with firm failure strongly suggests that managers of defaulted firms could be incapable of proper liquidity management.

The third explanation emerges from the disclosure and compliance literature. Non-compliance with reporting regulations has been empirically found to be characteristic of serial entrepreneurship as well (Lukason & Camacho-Miñano, Citation2021). There is both theoretical and empirical evidence that firms with poor financial health (including a high risk of bankruptcy and/or factual payment defaults) delay their annual reports more, including not submitting them at all (Lukason & Camacho-Miñano Citation2021; Selleslagh et al., Citation2021). More generally, firms in a poor financial condition have a higher propensity to commit law violations, and their actions are usually recurring (Baucus & Near, Citation1991), when compared with their vital counterparts. Therefore, by merging the latter ideas, it can be deduced that serial payment difficulties are frequent among entrepreneurs, and they usually coincide with serial non-submission of financial reports.

The specific theoretical background of study (see also ) enables to assume the following. The poor liquidity management has been found to be recurrent in SMEs, while as an important cause, (persistent) poor liquidity management skills of managers have been noted. More generally, poor (financial) management skills have been found to be persistent, and have served as a major precedent of firm failure. While payment difficulties in serial entrepreneurship have not been thoroughly studied, then another type of failure, namely serial non-compliance with accounting regulations, has been found to be persistent in time. As the latter is usually correlated with financial difficulties, such firms are likely to witness poor payment behaviour as well. Therefore, sequential poor payment behaviour might be rather common in entrepreneurship, as the poor liquidity management capabilities of managers can be rather persistent in time.

Thus, the integration of various literature streams suggests that managers of defaulted firms are more likely to witness payment disturbances in firms during their earlier entrepreneurial journey when compared to managers of non-defaulted firms. While the presence of payment disturbances could be manifested in either or both their frequency and size (Lukason & Andresson, Citation2019), we intend to test both of the latter with the following hypotheses:

H1a. The frequency of payment disturbances in the earlier entrepreneurial practices of managers increases the likelihood of corporate default.

H1b. The size of payment disturbances in the earlier entrepreneurial practices of managers increases the likelihood of corporate default.

While the previous narrative provided the main arguments for the usefulness of payment behaviour in earlier entrepreneurial practice as a predictor of corporate default, the following narrative focuses on the inherent problems of financial ratios as predictors, with a special focus on the SME segment.

The first explanation is based on the presence of different failure processes. For decades, it has been theoretically established and empirically proven that firms follow various pathways to collapse, some deteriorating very quickly, while the demise of others follows a longer timeline (Argenti, Citation1976; D’Aveni, Citation1989; Laitinen, Citation1991). It has also been established that for the majority of bankrupted SMEs, the values of financial ratios from the last timely submitted financial report and failure risk calculated based on them do not indicate any problems concerning longevity (Lukason & Laitinen, Citation2019). In addition, the latter examples (e.g. Laitinen, Citation1991; Lukason & Laitinen, Citation2019) concern the declaration of bankruptcy, not the emergence of payment defaults. In the SME segment, the phenomenon of quick collapse could be subject to liabilities of smallness (Lefebvre, Citation2022) and newness (Wiklund et al., Citation2010), meaning that due to the lack of reserves and inability to raise additional capital, poor performance (e.g. because of a single failed project) can be sustained only for a limited time, after which financial difficulties emerge. In turn, the collapse of large and listed firms has usually been subject to a lengthy failure process with many observable stages (Hambrick & D’Aveni, Citation1988). Thus, the decline of SMEs can be so rapid that the last correctly submitted annual report might not indicate any financial issues.

The second aspect that should be considered is the stage of the failure process. When studies usually aim to predict the last stage of collapse, that is, the bankruptcy declaration of a firm, stage models list several preceding phases, including the initial emergence of a payment default (see Laitinen, Citation1993; Weitzel & Jonsson, Citation1989). Firms experiencing payment difficulties initially try to find options to resolve the issue and might engage in negotiations with creditors to reschedule their debt (Laryea, Citation2010), while the ineffectiveness of the latter could lead to a lengthy reorganization process (Camacho-Miñano et al., Citation2015). Therefore, the period from the emergence of a payment default to permanent insolvency could be quite long. Studies have indicated that accounting information (including financial ratios) is relatively ineffective in predicting the emergence of payment defaults in the SME segment (e.g. Back, Citation2005; Kohv & Lukason, Citation2021; Wilson et al., Citation2000). Most of the available failure prediction studies focus on legal events (e.g. the start of insolvency proceedings or reorganization, declaration of bankruptcy), which stand further in the failure process timeline when compared with the emergence of a payment default, making the former much easier to predict.

The third problem, especially concerning firms in poor financial condition, is their systematic delay of annual reports. The latter phenomenon has been detected in studies using very large samples from various countries (e.g. Clatworthy & Peel, Citation2016; Lukason & Camacho-Miñano, Citation2019; Luypaert et al., Citation2016). There is a bulk of early and recent empirical evidence from failure prediction studies that firms’ reporting delays can be useful predictors of future insolvency (e.g. Altman et al., Citation2010; Iwanicz-Drozdowska et al., Citation2016; Keasey & Watson, Citation1987, Citation1988), indicating that timely reporting is a serious issue for distressed firms. Therefore, when even the correctly submitted financial reports of SMEs are poor in signalling future failure, the unavailability of recent financials can aggravate such issues even further.

Building on the latter arguments, available population-level empirical studies have shown notable classification errors in the case of financial ratios, especially in the SME segment (e.g. Altman et al., Citation2017), while literature reviews on Eastern European countries indicate a substantial variation in prediction accuracies as well (e.g. Prusak, Citation2018). Estonian comparative population level analysis indicates that in the case of bankruptcy prediction, 79.5% accuracy was achieved with financial ratios calculated from correctly submitted pre-bankruptcy annual reports (Lukason & Andresson, Citation2019), while in the case of existent reporting delays, the latter dropped to 63.3% (Lukason & Valgenberg, Citation2021). Besides the arguments noted earlier, Ciampi (Citation2015) attributed the low accuracy of financial ratios in the SME segment to less reliable and informative financial reports, while scale effects also exit, meaning that different external events can have a very large impact on the ratio values.

presents the principal idea behind the hypotheses of this study. It can be followed that more severe failure definitions (e.g. at least de facto insolvency by means of starting the insolvency procedure), the available studies are usually focused on, are emergent later in the decline timeline when compared with the definition applied in this study (i.e. the appearance time of a payment default). In , the development of payment defaults into more severe types of illiquidity has been assumed, although in practice, many firms are voluntarily able to resolve their illiquidity with different recovery strategies (e.g. Weitzel & Jonsson, Citation1989; Wu et al., Citation2013) and avoid the insolvency procedure. As indicates, the initial emergence of financial problems might be situated so early in the timeline that firms’ financial reports available at that time fail to signal any observable problems. Moreover, legally allowed remarkable delays in submitting financial reports in most countries, but the potential non-compliance of submitting later than the legal deadline can further aggravate the problem of information asymmetry. Therefore, the occurrence of payment disturbances in earlier entrepreneurial practices might be one of the few available instruments to enable early warning prediction of forthcoming financial problems. The latter becomes especially topical in the case when financial reports are outdated or not available at all.

Figure 1. A conceptual scheme of events and information availability in the failure process. Note: The lighter green colour indicates a reduction in the predictive value of the earlier payment behaviour variables.

Therefore, as various strands of the literature clearly point to the fact that failure prediction with financial ratios, especially in the SME segment, might have inherent problems, the following hypothesis has been postulated.

H2. Payment disturbances occurring in managers’ earlier entrepreneurial practices are better predictors of a firm’s default than financial ratios.

3. Study design

3.1. Dataset and its context

The data encompass the entire Estonian population of defaulted and non-defaulted firms, thus being free from sampling biases. For defaulted firms (dependent variable DEFAULT = 1), their default started on a random date from 2015 to 2019, while by the end of 2019, they were all deleted from the Estonian Business Registry. Default start time is defined as the appearance time of a payment disturbance that does not disappear until the deletion of the respective firm. If the latter permanency would not be accounted for, a firm would only be subject to temporary illiquidity (e.g. for one month only), which is rather common in the firm population. Although this study does not focus on the respective aspect, it is important to note that before the onset of a permanent payment default, earlier payment disturbances are rather infrequent for the studied firms themselves (see discussion with relevant statistical information in the Results section), therefore largely pointing to the onset of one major liquidity crisis in their lifecycle. In addition, before the onset of the payment disturbance that does not disappear, none of the defaulted firms have payment disturbances for the preceding month. Depending on the firm, the deletion can occur through varying procedures, some entering an official insolvency proceeding, while others are simply liquidated with unpaid debt. The start of the official insolvency procedure depends on several factors, including the size of unpaid debt and creditors’ interest in starting the respective procedure. If only one of the latter modes is chosen, the analysis may become biased, because statistically official insolvency procedure is more characteristic of larger entities.

The default definition applied in this study has certain differences when compared with other studies on the same topic. In the case of large and listed firms, the definition has often been broader than for SMEs, portraying different events (for instance, omitted dividends or missed principal and interest payments) usually defined by the international databases used (for instance, see Duffie et al., Citation2007; Duan et al., Citation2012). In the SME sector, definitions being similar to the Basel II criteria of the debt being unpaid for 90 days are usually applied (e.g. Altman et al., Citation2023; Nehrebecka, Citation2021), while studies have often defined corporate default based on legal procedures (i.e. start of insolvency proceedings or declaration of bankruptcy) as well (e.g. Ciampi, Citation2015; Modina & Pietrovito, Citation2014). This study looks at the exact onset date of either unpaid taxes or unpaid debt to private creditors (e.g. trade credit, bank loans), although the overwhelming proportion of the defaulted firms in the population used are subject to the former. Concerning tax arrears, according to the Estonian law, firms can reschedule their tax debt based on the agreement with the Estonian Tax and Customs Board, which is quite a usual practice. Because of the latter, for a certain period, firms can avoid legal actions (e.g. blocking of bank account, executive proceeding) against them, although their inability to pay tax debt has been substantiated. Therefore, such firms are at the onset time of their payment default often more comparable with firms going through a reorganization, rather than being permanently insolvent. Indeed, for all defaulted firms in this study, at some point in time after the appearance of the unpaid debt, it factually becomes a default, as even if renegotiation takes place, firms are not able to meet the schedule agreed with the creditor and/or new unpaid debt emerges. Such an approach enables to target the exact date when the payment problems arise, and in the case data from the previous calendar year are used to predict that specific onset of problems, an early warning approach can be achieved with the respective prediction models.

The non-defaulted firms (dependent variable DEFAULT = 0) had no payment disturbances at the end of 2019, which does not rule out their pre- or post-presence from that date. This enables us to capture all functional firms irrespective of how well they perform, while the exclusion of poorly performing entities would again create a bias in comparing only factual failures against firms with relatively good performance. Firms with a payment disturbance at the end of 2019, but still functional, are excluded, as in their case, it is not known what their status in the future will be. As it is not known whether they will eventually fail or overcome their financial difficulties, their correct status cannot be coded.

In the case of both defaulted and non-defaulted firms, the earlier managerial background is considered in all firms, in which respective individuals have been board members for the five full years before the default year. Individuals can enter and exit the boards on random dates, and the dataset enables us to capture this aspect. Therefore, earlier entrepreneurial practice involves information about all board memberships, including those connected to the firm behind the coded dependent variable. While the default of a firm can occur on a random date during the calendar year, the median period in the dataset from the end of the previous calendar year to default onset is six months, providing a reasonable early warning possibility when the created models are applied in practice. Similarly, for non-defaulted firms, managers’ behaviour in all firms they have been board members is considered, while because of the absence of a discrete event, five full years spanning from 2014 to 2018 are applied.

Unlike the context of large and listed firms, but also when accounting for jurisdictions other than Estonian, this study focuses on a peculiar type of corporate governance system. The bulk of firms in the analysis behind both dependent and independent variables are micro-, small-, and medium-sized entities. These firms in Estonia follow a corporate governance system in which the management board is directly subject to owners, although there is also a substantial overlap between these two. For instance, in a study applying an Estonian firm population with a similar size, Lukason and Camacho-Miñano (Citation2020) documented that 84% of firms have a majority owner and 87% have at least one owner on the management board, the median number of board members being one. Thus, when summarizing these facts, the study focuses largely on owner managed SMEs. It is also important to note that in such entities, board members are legally responsible for all activities and act as chief executive officers. Thus, the payment behaviour in these firms is the direct responsibility of one or a few individuals that the study focuses on, and emergent payment problems can be directly associated with them. The latter is not valid in the case of large and listed firms, where the corporate governance system is composed of several layers (Süsi & Lukason, Citation2019). Because of that, the individual responsible for poor financial performance could, for instance, be the hired financial manager.

All firms included are VAT responsible (the minimum limit in Estonia is a turnover of 40 thousand euros), while the final dataset includes 1380 defaulted firms and 42,803 non-defaulted firms. It is important to note that, from the initial population of defaulted firms (in total, 2111 firms), 731 firms had to be excluded, as they did not have any financial reports available, while the same tendency was remarkably less frequent in the population of non-defaulted firms (namely, 785 non-defaulted firms out of 43,588). The exclusion is done in order to keep the population homogenous, meaning that all firms have information about all variables available. Thus, defaulted firms are clearly less law-obedient to follow the accounting rules, as documented for the Estonian firm population in earlier studies as well (e.g. Lukason & Camacho-Miñano, Citation2019; Citation2021). Corresponding to the firm population in other European countries, the average company in the dataset is an old micro firm, whereas other size categories are represented less frequently. The data period reflects a stable economic environment with constant economic growth and is therefore free from crisis irregularities (e.g. recent virus outbreaks and war contexts).

3.2. Variables

Earlier entrepreneurial background variables encompass the average, maximum, and frequency tendencies of payment disturbances. For Hypothesis 1a, a single variable was calculated (COUNTPD), while for Hypothesis 1b, two independent variables reflecting the average (MEANPD) and maximum (MAXPD) tendencies were applied, as based on earlier literature (Lukason & Andresson, Citation2019; Lukason & Valgenberg, Citation2021), both of them have been useful (see for respective variables). COUNTPD reflects the number of month-ends with payment disturbances that board members have had during the five-year period viewed in all firms managed by them. Thus, for instance, when a person has been a board member in a single firm with a payment disturbance documented for each month end for five years, the variable obtains a value of 5 × 12 = 60. Similarly, when a person has been a board member in three different firms, each of them having payment disturbances for five month ends over five years, the variable obtains a value of 5 + 5 + 5 = 15. As the available data encompass the exact dates on which each individual has served as a board member, it is possible to precisely detect the months with payment disturbances under the relevant individual’s governance. Earlier studies (e.g. Mramor and Valentincic Citation2003, Lukason and Andresson Citation2019) have indicated that such frequency variables are more beneficial in reflecting the persistence of payment disturbances when compared with the usage of, for instance, a binary variable portraying their presence irrespective of duration. While the latter has been frequently used, for instance, equivalently considering the payment disturbance for one month with payment disturbances for 50 months over five years, it could lead to a bias in overestimating the role of random disturbance events in the earlier entrepreneurial careers. For instance, infrequent payment disturbances have been found to be common in the case of SMEs (Lukason and Valgenberg Citation2021). MEANPD and MAXPD reflect the average and maximum (natural logarithms of the value in euros) of payment disturbances occurring during the five-year period, respectively. The payment disturbance information encompasses both private and public claims. While private claims include unpaid debt to various creditors (e.g. suppliers and banks), public claims include mainly tax arrears (and infrequently also claims for public services). As expected, based on past research (e.g. Lukason & Andresson, Citation2019), unpaid tax claims are much more frequent in the dataset, both when coding the dependent variable DEFAULT and the independent variables reflecting the earlier payment behaviour of managers.

Table 2. Variables of the study.

In Estonia, information about public and private claims is available with daily accuracy. However, as tax arrears are organically interconnected to declaring and paying corporate taxes, the frequency of which is monthly during the follow-up month after the taxes occurred, it is logical to focus on the month-ends rather than on a daily frequency. A similar strategy has been applied in earlier studies (e.g. Lukason & Andresson, Citation2019; Lukason & Valgenberg, Citation2021), while the motivation to use the month-ends has been that delays of a few days exceeding the tax payment dates positioned on the 10th and 20th day of each month might be too frequent and random to be considered as a disturbance.

In the case of Hypothesis 2, for comparative purposes, four financial ratios have been calculated (), which are among the most traditional predictors applied in relevant studies, being already applied (with slight modifications) in the seminal study by Altman (Citation1968). ROA reflects profitability as the net income divided by total assets. The STA portrays productivity (efficiency) as the operating revenue to total assets. EA reflects solvency (as well as capital structure) as the ratio of total equity to total assets. Finally, the WCTA portrays liquidity as the net working capital to total assets. It should also be noted that, as mainly the micro firm segment is concerned, these entities publish very general financial statements, which restricts the usage of more detailed financial ratios. In addition, earlier bankruptcy prediction research based on the Estonian firms’ population by Lukason and Andresson (Citation2019) has indicated that only the usage of EA has led to a 77.1% accuracy one year before the bankruptcy declaration, while the simultaneous usage of ten financial ratios has only marginally increased the accuracy, reaching to 79.5%. The chosen financial ratios are calculated from the last annual report (for defaulted firms, the pre-default report) similarly to earlier failure prediction studies. For both groups of variables, winsorization is applied before implementing them in the empirical analysis, as in the case of both, the usually occurring extreme values can have an effect on the estimations.

3.3. Methods

The applied methods differ for Hypotheses 1a and 1b in comparison with Hypothesis 2. For Hypotheses 1a and 1b, the general usefulness of earlier payment disturbances is studied with the average marginal effects from the logistic regression, where the defaulted firm is coded as 1 and the non-defaulted firm is coded as 0. Thus, a positive significant marginal effect indicates support for the respective hypotheses. As payment disturbance variables tend to be highly correlated, logistic regression models are composed separately for all three variables. For instance, the correlation between MEANPD and MAXPD is 0.95, and the others also indicate very high levels. Moreover, marginal effects from the logistic regression models with single variables are useful for understanding the behaviour (i.e. the increase or decrease of the effect) of the respective variables in sub-populations. As the first set of hypotheses aims to disclose how the PDMs are associated with the likelihood of default, marginal effects are the most suitable option. Comparatively, the prediction accuracies do not enable to outline whether the specific variables are statistically significant, and if they are, whether the signs are in accordance with the theory (i.e. more payment disturbances leading to a higher likelihood of default).

To outline whether some typical contexts noted in the literature affect the results, separate analyses were run for several sub-populations. These include younger versus older and smaller versus larger firms, formed by breaking the populations of (non-)defaulted firms on the median age or size, the latter defined by using the total assets. In addition, the population is divided into firms in which the managers have no entrepreneurial background in other firms during the five-year period, and, respectively, to those in which the entrepreneurial background originates from at least two different firms. This divides the population into 348 defaulted and 20,274 non-defaulted firms in the group with background from only a single firm (i.e. the firm used to code the dependent variable), while in the other group with more entrepreneurial background, the figures are respectively 1032 and 22,529. The sectoral context is captured by the fact, whether the main sector in which the firm operates is business-to-business (B2B) oriented. This results in 1007 defaulted and 31,847 non-defaulted firms operating in the B2B sector, while the same frequencies for non-B2B firms are 373 and 10,956, respectively. Finally, the internationalization context of the firm is captured by the fact that it was engaged in some exporting based on the last annual report, which divides the population into 960 defaulted and 26,937 non-defaulted firms among non-exporters, while the same figures for exporters are 420 and 15,866.

For Hypothesis 2, which focuses on the goodness of the different variable pools as predictors, three different prediction methods were applied. In addition to the classical logistic regression method, two machine learning tools, neural networks and decision trees, were applied as well in order to avoid a single-method bias. The predictive accuracy of models is provided in the classical way from the confusion matrix by calculating the sum of predicted true positives and negatives divided by the total population employed. To outline the predictive accuracy, the populations of defaulted and non-defaulted firms are equalized using a synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE), which is a common strategy to avoid the predictive model from preferring the majority group. In this study, SMOTE is applied in its usual form, that is, by repeating the minority observations as long as their population equals that of the majority group. The latter enables us to clearly outline how well (non-)defaulted firms are distinguishable from each other. Otherwise, the prediction methods tend to prefer the majority class (DEFAULT = 0 in the current case), leaving the accuracy in the minority class (DEFAULT = 1) largely irrelevant.

Logistic regression was applied to the entire population. As the chosen machine learning methods tend to obtain better results on the training sample, the dataset of defaulted and non-defaulted firms equalized with SMOTE is broken equally between the training and testing samples (i.e. 50% of observations in both groups), while the accuracies from the latter are provided. For the neural networks, a two-layer architecture was applied, whereas the CRT algorithm was used for the decision tree. In the case of machine learning methods, the highest accuracy out of five runs is reported. While models are composed separately with earlier payment behaviour variables and financial ratios using all three methods, models incorporating both of these variable pools are also created to portray the total accuracy with all available predictors. From a practical sense, the prediction accuracies from models including only earlier payment behaviour variables are especially important when firms’ annual financial reports are not available or financial ratios fail to signal any forthcoming financial problems. In turn, the models, inclusive of all variables, outline the full potential of the information used for the early warning of a payment default emergent in the future. In addition, the predictive accuracies of single payment behaviour variables, also in the case of different firm contexts, have been outlined to indicate their individual potential in predicting corporate default. This enables to understand, how much uni- and multivariate models differ from each other, as very similar prediction accuracies for the former and the latter would reduce the practical benefits of using multiple variables simultaneously.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics and Welch’s robust ANOVA results provided in clearly indicate that the variables portraying PDMs have more potential to discriminate between (non-)defaulted firms. Namely, the means of COUNTPD, MEANPD, and MAXPD have several-fold higher values in the case of defaulted firms’ managers when compared with those of their non-defaulted counterparts. Although Welch’s ANOVA indicates significant differences in the means of financial ratios, the respective test statistics are substantially smaller, and the comparison of the mean values of (non-)defaulted firms also indicates smaller divergence. Moreover, the STA means and medians are higher in the case of defaulted firms, which is contradictory to the common financial knowledge, as defaulted firms are more productive.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics by the status of firms.

For the follow-up narrative it is important to note that when additionally considering the payment disturbances in the defaulted firms themselves (i.e. disregarding the managerial behaviour in other firms), during sixty months the median number of month-ends with a payment disturbance is 3.0 (variable COUNTPD), while the median values for MEANPD and MAXPD (which are natural logarithms of the original figures) are respectively 2.6 an 5.8. When comparing the latter values with those provided in , which account for managerial background in other firms also (21.0, 5.6, and 8.0, respectively), it can be seen that the bulk of the earlier poor payment behaviour originates from firms other than the defaulted firm itself. This especially points to the fact that, in the case of defaulted firms, the managers of which have run at least one other company in the past, the problems are clearly emergent from other firms. The latter is not the case for firms whose managers have run only a single company, as payment behaviour is directly emergent from the same defaulted firm.

The usefulness of different earlier payment behaviour variables is outlined using the average marginal effects from the logistic regression in . The marginal effects for the average, maximum, and frequency tendencies of earlier payment disturbances, reflected by MEANPD, MAXPD, and COUNTPD, are highly significant and positive. In , it can be seen that in the case of non-defaulted firms’ managers, the median value of MEANPD is zero, while the same figure in the case of defaulted firms’ managers is 5.6. When the latter is converted back from the natural logarithm, it can be concluded that managers of a median defaulted firm have witnessed an average of 270 euros of payment disturbances over the respective period. As the median figure of MAXPD is approximately 11 times larger than the latter figure (in case converted back from natural logarithm), it can be concluded that MEANPD is determined by the systematic presence of smaller payment disturbances, not by some episodic huge payment disturbances. This argument is also supported by the rather high median value of 21 for COUNTPD for defaulted firms. The latter figure means that in the case of a median defaulted firm, its managers have payment disturbances for 35% of the months during the five-year earlier entrepreneurship period. The same figure for managers of non-defaulted firms is only 1. At the same time, the averages for MEANPD and MAXPD for non-defaulted firms were only 2.0 and 3.3. Therefore, it can be concluded that the managers of non-defaulted firms still witnessed payment disturbances in their earlier entrepreneurial activities, but they have not been as large and persistent as in the case of managers of defaulted firms.

Table 4. Average marginal effects from the logistic regression analysis by single payment behaviour variables for different firm populations.

Additional evidence is provided with an analysis of the marginal effects in firm sub-populations. indicates that MEANPD, MAXPD, and COUNTPD have a stronger effect in the case of larger and older firms, those focused on B2B sales, and those with domestic orientation. Despite the latter variations of effects in sub-populations, they do not differ substantially from the result obtained by using all firms, therefore indicating a relative homogeneity of variables’ behaviour in the sub-populations. The expected exception is the entrepreneurial background context, as the effects are to 2–3 times larger for firms where managerial background originates from at least two companies, when compared with counterparts with a background from a single company only. As outlined earlier, such an increase in the marginal effect is largely caused by firms other than the defaulted firm itself, thereby pointing to the poor liquidity management practices of those managers in earlier firms. In turn, the marginal effects in the case where the background originates only from a single company directly point to earlier payment behaviour in the same firm.

The best accuracy in the population (), when the groups of (non-)defaulted firms were equalized with SMOTE, was obtained with MEANPD, having a value of 71.4%. However, MAXPD and COUNTPD did not provide substantially lower accuracies (70.7 and 70.0%, respectively). The result that more than two-thirds of cases can be classified correctly with a single variable can be considered an acceptable result.

Table 5. Accuracies from the logistic regression analysis with single payment behaviour variables for different firm populations.

Despite the very similar general precision of the applied variables, the accuracies among the sub-populations of defaulted and non-defaulted firms can differ more substantially. The latter results can be directly dependent on the shapes of distributions, that is, how (non-)distinguishable observations are positioned, which is, in turn, subject to varying frequencies of financial processes in the sub-populations. The total accuracies are higher with the following pattern: (a) larger firms over smaller firms, (b) older firms over younger firms, (c) firms with managerial background from at least two firms over those with experience from a single entity, (d) firms with B2B focus over non-B2B firms, and (e) exporters over non-exporters. Nevertheless, the differences in total accuracies when comparing different sub-populations remain below five percentage points, which also holds when comparing them with the population’s accuracy. Therefore, context-specific fluctuations in the total prediction accuracy cannot be considered large.

There is much more divergence in accuracies when looking at defaulted and non-defaulted firms in the sub-populations; in some instances, the former is much higher, and vice versa. In the case of COUNTPD, the accuracy for non-defaulted firms was much higher. This would point to the fact that while most managers of non-defaulted firms have managed their firms with or without infrequent payment disturbances, slightly less than half of the managers of defaulted firms have achieved the same. The relatively equal accuracies for MEANPD for (non-)defaulted firms tend to indicate the presence of a low positive value of the respective variable that maximizes predictive accuracy. Namely, when considering the centiles, the cut-off point for the respective variable is set at around 30 euros for both firm groups, that is, (non-)defaulted entities. With regard to MAXPD, the accuracy is higher for defaulted firms, pointing to the fact that, although infrequently (e.g. for a single month), there have been larger disturbances in the entrepreneurial practices of managers of non-defaulted firms.

extends the analysis from univariate to multivariate by comparing the accuracies of past payment behaviour variables with classical financial ratios. indicates that the former outruns the latter by more than ten percentage points, depending on the classification method applied. The most accurate prediction is produced in the case of a decision tree; however, its result does not exceed that of neural networks and logistic regression remarkably. As nearly three-fourths of observations are classified correctly by using past payment behaviour variables, the accuracy can be considered acceptably high, while in the case of financial ratios, it is low. For instance, the logistic regression model with all four financial ratios included did not exceed the 60% accuracy threshold. The prediction models incorporating three payment behaviour variables do not have remarkable superiority over those including only a single variable, which is evidently induced by (very) high correlations between all three variables. The simultaneous usage of past payment behaviour variables and financial ratios provides some increment (about 2–3 percentage points) in the total accuracy when compared with using only the former, and thus, the benefits of adding financial ratios to the prediction model are minimal.

Table 6. Accuracies by two types of variables and both combined with three different prediction methods.

As outlined earlier, misclassifications largely originate from two reasons. In the defaulted firms’ group, managers for a certain proportion of firms have either not witnessed payment disturbances in their earlier entrepreneurial background or their frequency is low and/or their size small. Therefore, these individuals are indistinguishable from their counterparts running non-defaulted firms. In turn, in the non-defaulted firms’ group, a certain proportion of managers have witnessed smaller or larger payment disturbances in their entrepreneurial practice, while these are usually (but not necessarily) temporary in nature. Therefore, the classification methods applied usually set breakeven values on a certain (small) amount of payment disturbances that lead to Type I and Type II classification errors.

5. Discussion

This section discusses the contribution of the findings to the extant literature, while the results of hypotheses testing with their relevance to the extant theoretical knowledge have been consolidated in .

Table 7. Study’s results and their theoretical essence.

Both hypotheses from the first set (i.e. Hypotheses 1a and 1b) were accepted, meaning that the frequency and size of PDMs is larger in the case of defaulted firms. The general theoretical implication of the study points to the fact that the upper echelons’, serial entrepreneurship and non-learning from failure concepts apply when PDMs are used to predict corporate default. The latter means that managers, who have witnessed failures in their earlier careers, tend to make the same mistakes again. This provides proof for the theoretical proposition of non-learning from failure in serial entrepreneurship by Nielsen and Sarasvathy (Citation2016) in the context of recurrent payment disturbances. In the studied population, 75% of defaulted firms were founded by serial entrepreneurs. As the new companies founded by serial entrepreneurs witness a default and exit after the latter, such managers are subject to persistent inadequate liquidity management and poor (financial) management skills more generally. This finding matches the earlier studies pointing to similar issues being recurrent in the case of SMEs (Baldwin et al., Citation1997; Ekanem, Citation2010). The bulk of the defaulted firms have also compliance issues, as expected based on earlier studies (e.g. Altman et al., Citation2010; Iwanicz-Drozdowska et al., Citation2016; Lukason & Camacho-Miñano, Citation2021). Namely, 35% of defaulted firms had to be excluded from the initial population because of no financial reports available, and although not specifically studied in this paper, the financial information availability issue became characteristic to the majority of firms included in the analysis after the emergence of the default.

All three variables reflecting PDMs were significant and with theoretically expected signs, their larger size and frequency increasing the likelihood of corporate default. Of specific variables, the average tendency of PDMs had the largest marginal effects, followed by those reflecting the maximum and frequency tendencies. The prediction accuracies of individual variables followed the same ranking, but the differences were minimal. Indeed, in Lukason and Andresson (Citation2019) focusing on payment behaviour in (non-)bankrupt firms, the maximum and frequency contexts have been superior over the average tendency in predicting bankruptcy. That might be logically explained by the fact that in a specific firm, the payment default should be sizable enough to initiate the bankruptcy proceedings. An important theoretical implication emerging from the results is that while managers of non-defaulted firms can occasionally witness payment disturbances in their business practices, including large ones, these are not as persistent as in the case of defaulted firms’ managers. In the case of the latter, we postulate the existence of a persistent poor liquidity management in serial entrepreneurship, rather than episodic liquidity shocks probably caused by adverse external events.

Based on the literature (e.g. Altman et al., Citation2017), it could be expected that the firm context might play an important role, which is not the case in this study. For instance, by relying on the theories of liabilities of smallness (Lefebvre, Citation2022) and newness (Wiklund et al., Citation2010), it might be expected that the predictive value of variables varies for smaller/larger or newer/older firms. The marginal effects and prediction accuracies in different firm populations can vary, but not substantially. The latter can be logically explained by the fact that the median defaulted firm in the population is a micro firm by size with a lifetime of 5.4 years until the onset of the payment default. Therefore, the population of firms in this analysis is probably too homogenous for these liabilities to exist. Similarly, export- and B2B-orientations do not substantially affect the obtained results.

The only exception to the latter narrative concerning the role of firm’s characteristics is the serial entrepreneurship context (i.e. whether the manager has run any other companies in the entrepreneurial career), specifically exemplified as follows. In the case of 1032 defaulted firms out of 1380, the managers have run other companies, while in the case of remaining 348 firms, it is the only firm the managers have run in the viewed period. Concerning the source of disturbances, the 1032 defaulted firms divide as follows: (1) for 121 firms the disturbances emerge only from the defaulted firm, (2) for 343 firms the disturbances emerge only from other firms, (3) for 568 firms the disturbances emerge from both firms, while out of those, for 389 firms the disturbances emerging from other firms are more frequent and/or larger than in the defaulted firm itself. Therefore, when managers have run other companies (i.e. the sub-population of 1032 defaulted firms), the earlier payment disturbances in other companies (not in the defaulted firm itself) have the sole or main importance in corporate default prediction for 70.9% (343 + 389 = 732) of such firms. The latter example extends the theoretical proposition of serial poor liquidity management further. Namely, in predicting the default of a company managed by a serial entrepreneur, the payment disturbances witnessed in other companies generally matter more than those emerging from the same firm. Such a proposition views the theoretical concept of the value of payment disturbances in corporate default prediction postulated on specifically in the serial entrepreneurship context.

The second hypothesis was also accepted, meaning that PDMs lead to a more accurate prediction of corporate default than financial ratios. Such a finding is valid not only by using three variables reflecting PDMs together, but also with each of those variables separately. The highest accuracy achieved with three variables was 73.7% with a decision tree model. Still, the accuracies for different methods, and either three or a single variable reflecting PDMs applied do not differ remarkably. For instance, the lowest accuracy with logistic regression and a single variable was 70.0%. The accuracies of payment behaviour variables are larger than in earlier comparable studies (e.g. Back, Citation2005; Mramor & Valentincic, Citation2003; Wilson et al., Citation2000), while in these studies, payment disturbances and defaults in the same firm were used. For instance, in Back (Citation2005), the average accuracy for such a prediction using multiple payment behaviour variables simultaneously was only 66% in the case of comparing healthy firms with those having a payment delay, and 67% for healthy firms versus those with recorded payment disturbances. Back (Citation2005) is the only study, in which a comparable single binary variable reflecting PDM was applied, but it remained insignificant in all regressions.

The European failure prediction models using millions of observations and focusing on a failure definition further away in the timeline, i.e. bankruptcy prediction or deletion of a firm because of bankruptcy, have indicated a comparatively weak performance of financial ratios. Namely, in Altman et al. (Citation2017) the area under the curve for such a model was 0.745 and in Laitinen and Suvas (Citation2013), 0.777, the latter pointing to a 71.1% average accuracy comparable with this study’s results. The probable reasons for the low accuracy of financial ratios postulated in the theoretical narrative include the following. Firms in the SME segment are dominated by a very quick failure process (Lukason & Laitinen, Citation2019), financial ratios do not suit well for the prediction of early phases of the firm failure process (Laitinen, Citation1993), and more generally, firms in a poor financial situation might not comply with submitting financial reports on time (Lukason & Camacho-Miñano, Citation2021). The latter reason is especially topical for the 35% of defaulted firms excluded from the empirical analysis, because none of the financial reports were available. In addition, a certain threat in the case of those defaulted firms submitting their reports timely has been noted to be the reliability of financial statements (Ciampi et al., Citation2021; Laitinen et al., Citation2023). The prevalence of a quick failure process in the SME segment postulated by Lukason and Laitinen (Citation2019) and low prediction accuracy of financial ratios derived from that is indicated by the mean values of financial ratios (see ). The defaulted firms were more productive before the onset of default, while this contradicts the earlier failure prediction studies, as for example, the mean values in Altman (Citation1968) for productivity were larger in the case of non-bankrupted firms. In addition, the differences in the mean and median values of financial ratios of (non-)defaulted firms were much smaller when compared with Altman (Citation1968) and Altman et al. (Citation2017). This indicates that the firm failure process has not yet manifested in the available financial information, while the theoretical foundations of this have been more explicitly explained with concepts in and on .

As an important contribution to answering the call by Ciampi et al. (Citation2021) to introduce novel variables for failure prediction, this study provides a new instrument by means of payment behaviour in the earlier entrepreneurial background, which can exceed financial ratios in predictive accuracy.

6. Practical implications

The main practical benefit of the established approach emerges from the introduction of novel theoretically motivated variables, which enable an early warning of the corporate default with a higher accuracy than classical financial ratios. These variables are valuable in the case financial ratios indicate a good performance for firms defaulting in the future, making them undistinguishable from their vital counterparts. In addition, a certain type of such firms can be the newly founded (start-up) firms, in the case of which most of them witness poor performance at the early stages, and therefore, the usage of the earlier managerial background is among the few possibilities to predict their future status.

The additional very important practical benefit of the established approach concerns firms which have not submitted any financial statements. There can be several types of such firms, such as old firms not complying with accounting regulations or firms being too young to be liable to submit any financial reports yet. The practical benefit is empirically demonstrated on the population of firms excluded from the empirical analysis because of having missing financial information. For that purpose, the logistic regression model created in the empirical part of the paper and including three payment behaviour variables (specifically, the model from having an accuracy of 70.9%) is validated on the population of defaulted firms not included in the analysis because of not submitting any financial reports. Specifically, out of the population of 731 such firms, the focus is on 507 firms, the managers of which have earlier interconnections with at least one other company. The accuracy of the respective logistic regression model is 72.2% in that population. Therefore, the model provides a reasonable accuracy for a practical use when financial information about a firm is fully absent, but its managers have interconnections with other firms. The latter calculation also provides evidence that the created approach is applicable in Estonia on datasets other than that used for the composition of respective models. The applicability in other countries depends on the fact, whether information is known about payment defaults (including tax arrears) and which firms the managers have run earlier. Recent studies from different countries (e.g. Altman et al. Citation2022, Altman et al. Citation2023) have indicated such availability, although a separate question is, whether it is available without additional costs. The existence of data procurement costs can logically set certain minimum requirements for the classification accuracies of respective models. In addition, as outlined in Altman et al. (Citation2022) with the help of various scenarios, the usefulness of respective models is dependent on the profit function of the lender (in a specific country), as the costs of different types of misclassifications can vary.

7. Conclusion

This study aimed to determine how payment disturbances in managers’ earlier entrepreneurial practices (PDMs) predict corporate default. As the paper concerns the introduction of novel predictors for corporate default prediction and specific theories for it are absent, a theoretical framework was built based on merging different streams of the literature. The hypotheses relying on the built theoretical framework focus on the usefulness of PDMs in corporate default prediction and their potential superiority over financial ratios. The dataset included all Estonian (non-)defaulted firms, irrespective of their characteristics. The individual usefulness of different variables reflecting the frequency and size of PDMs was assessed with the help of average marginal effects from the logistic regression analysis. The potential superiority of variables reflecting PDMs over financial ratios in corporate default prediction was analysed by using three different prediction methods.

The main results indicate that three variables reflecting PDMs are useful for corporate default prediction. While all three variables reflecting the frequency, maximum size and average size of PDMs are useful in predicting corporate default, the latter of them can be considered the most beneficial for the respective purpose. All three variables combined, but also individually, surpass the accuracy of financial ratios in corporate default prediction. As an essential contribution to the extant literature and answer to the recent calls in thematic literature reviews, the study introduced a set of novel theoretically motivated variables for corporate default prediction. As the most important theoretical contribution, the study outlines the existence of persistent poor liquidity management practices (reflected with the presence of payment disturbances) in the case of serial entrepreneurs (specifically, managers of SMEs) in their sequential ventures.

The practical benefits of the approach, which have been discussed in detail in the specific section of the paper, are summarized as follows. First, the study introduces a novel alternative to the usage of financial ratios in corporate default prediction. Second, the prediction accuracies achieved with payment disturbances in managers’ earlier entrepreneurial careers exceed those of recent over-European bankruptcy prediction studies, although the failure definition applied in this study is situated earlier than the declaration of bankruptcy. The latter also means that the introduced approach is more directed to early warning, potentially enabling creditors to avoid a larger amount of losses. Finally, the proposed solution could be invaluable when firm’s financial information is fully absent and other non-financial alternatives for the prediction are unavailable or with a lower accuracy.

While knowing the value of using past payment behaviour to predict the same phenomenon in the future, there are multiple future research avenues, some of which are described below. The payment behaviour background can be treated in a more sophisticated manner, for example, by looking at a longer time horizon or considering more sophisticated patterns of it. Possibilities also exist for extending non-learning from failure theory by looking more specifically into a richer set of determinants, as repeating poor liquidity management could only be one explanation for the firm’s default. For instance, a variety of different (absent) knowledge types can interact, resulting in (non-)failure (e.g. Baldwin et al., Citation1997; Vissak et al., Citation2020). Finally, an intriguing research question would be whether the introduction of these predictors to accompany other high-accuracy (non-)financial variables would, with the help of some advanced machine learning methods, make a breakthrough in SME failure prediction towards an almost ideal accuracy.

This study has some limitations. First, the applicability of the results in other countries depends on both the legislation and the business environment in the respective locations. If failure is penalized and stigmatized, then it is possible that the usage of specific variables would be more restricted, as the fresh start with a new company could be complicated. In turn, there can be environments where the effect of past payment behaviour variables could be even more pronounced, as failures are considered a usual part of business practice. The dataset was limited to the previous five years of entrepreneurial background, while a longer timeframe would potentially help to capture such entrepreneurs, who, following the initial entrepreneurial failure, migrated to paid work, but after a substantial time had passed, re-entered entrepreneurship. However, the track of entrepreneurial background from a very distant past raises different questions, such as what is the maximum time of persistence for an earlier experience at all. In addition, in the case of this study, the longer period would have overlapped with the previous financial crisis, potentially creating some bias towards failures.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed to all parts of the work and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgement

Financial support from the Estonian Research Council’s grant PRG1418 ‘Export(ers’) Performance in VUCA and Non-VUCA Environments’ is acknowledged by both authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data not available due to legal restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Art Andresson

Art Andresson is a PhD student at the University of Tartu. His research focuses on firm failure prediction. He has a lengthy career as a CEO in the credit industry.

Oliver Lukason

Oliver Lukason obtained his PhD degree from the University of Tartu, where he is currently an associate professor of international business and finance. His main research areas include firm failure prediction and causes, internationalization, non-compliance with regulations, and he has published many articles in these domains. He has also built numerous decision support systems in the credit industry.

References

- Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2978933

- Altman, E. I., Balzano, M., Giannozzi, A., & Srhoj, S. (2023). Revisiting SME default predictors: The Omega Score. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(6), 2383–2417. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2135718

- Altman, E. I., Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., Laitinen, E. K., & Suvas, A. (2017). Financial distress prediction in an international context: A review and empirical analysis of Altman’s Z-Score Model. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 28(2), 131–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/jifm.12053

- Altman, E. I., Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., Laitinen, E. K., & Suvas, A. (2022). A race for long horizon bankruptcy prediction. Applied Economics, 52(37), 4092–4111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2020.1730762

- Altman, E. I., Sabato, G., & Wilson, N. (2010). The value of non-financial information in SME risk management. The Journal of Credit Risk, 6(2), 95–127. https://doi.org/10.21314/JCR.2010.110

- Argenti, J. (1976). Corporate collapse: The causes and symptoms (p. 193). McGraw-Hill.

- Baldwin, J., Gray, T., Johnson, J., Proctor, J., Raffiquzamann, M., & Sabourin, D. (1997). Failing concerns: Business bankruptcy in Canada, Ottawa (p. 70). Analytical Studies Branch, Statistics Canada.

- Back, P. (2005). Explaining financial difficulties based on previous payment behavior, management background variables and financial ratios. European Accounting Review, 14(4), 839–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180500141339

- Baucus, M. S., & Near, J. P. (1991). Can illegal corporate behavior be predicted? An event history analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 9–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/256300 https://doi.org/10.2307/256300

- Beaver, W. H. (1966). Financial ratios as predictors of failure. Journal of Accounting Research, 4, 71–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490171

- Boso, N., Adeleye, I., Donbesuur, F., & Gyensare, M. (2019). Do entrepreneurs always benefit from business failure experience? Journal of Business Research, 98, 370–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.063

- Camacho-Miñano, M.-M., Segovia-Vargas, M. J., & Pascual-Ezama, D. (2015). Which characteristics predict the survival of insolvent firms? An SME reorganization prediction model. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12076

- Chen, J. (2013). Selection and serial entrepreneurs. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 22(2), 281–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12016

- Ciampi, F. (2015). Corporate governance characteristics and default prediction modeling for small enterprises. An empirical analysis of Italian firms. Journal of Business Research, 68(5), 1012–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.10.003

- Ciampi, F., Giannozzi, A., Marzi, G., & Altman, E. I. (2021). Rethinking SME default prediction: A systematic literature review and future perspectives. Scientometrics, 126(3), 2141–2188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03856-0

- Clatworthy, M. A., & Peel, M. J. (2016). The timeliness of UK private company financial reporting: Regulatory and economic influences. The British Accounting Review, 48(3), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2016.05.001

- Dabić, M., Vlačić, B., Kiessling, T., Caputo, A., & Pellegrini, M. (2021). Serial entrepreneurs: A review of literature and guidance for future research. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(3), 1107–1142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1969657

- D’Aveni, R. A. (1989). The aftermath of organizational decline: A longitudinal study of the strategic and managerial characteristics of declining firms. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 577–605. https://doi.org/10.2307/256435

- Duan, J.-C., Sun, J., & Wang, T. (2012). Multiperiod corporate default prediction – a forward intensity approach. Journal of Econometrics, 170(1), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2012.05.002

- Duffie, D., Saita, L., & Wang, K. (2007). Multi-period corporate default prediction with stochastic covariates. Journal of Financial Economics, 83(3), 635–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.10.011

- Ekanem, I. U. (2010). Liquidity management in small firms: A learning perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001011019161

- Eurostat. (2022). Business demography. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/structural-business-statistics/business-demography (Retrieved 30 May 2022).