Abstract

In the era of climate change, stakeholders are becoming more concerned about the sustainability disclosure of businesses. However, for developing economies like Ghana, studies on stakeholders’ pressure and sustainable development has not received much attention. Hence, this study examines the influence of stakeholders’ pressure on sustainability disclosure and employed green technological innovation (GTI) as a mediating factor. The study focused on mining and manufacturing firms because their processes are known to release carbon dioxide, create waste. The data utilize in this study was collected from 383 respondents in Ghana via online questionnaires. PLS-SEM was used to analyze the data and tested the hypothesis for the study using SMART-PLS 4. The results demonstrated that stakeholder pressure substantially improves sustainability disclosure performance. Also, the results revealed that a firm’s GTI mediates the connection between stakeholder pressure in terms of shareholder and consumer pressures. However, government pressure and sustainability disclosure were found to be insignificant. The study recommends that managers should incorporate GTI into the product design and manufacturing process since it enables firms not only fulfill their client’s needs but also reduce their environmental impacts, like the production of carbon dioxide and solid debris.

SUBJECTS:

1. Introduction

Almost all of the world’s largest firms now regularly provide sustainability reports that outline their operations and the impacts they have had in the areas of environment, society, and governance (Agyemang et al., Citation2023a). Major firm publishes its annual report detailing the impacts of their business operations on society, the environment, and the economy (Wiredu et al., Citation2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure has increased in importance for almost all economies as people throughout the world are concerned about the global ecological challenges and the associated need to preserve the ecosystem. Hence, several firms are trying to be more accountable and environmentally friendly. To clearly understand and share their effect on ESG concerns, businesses and governments around the world seek guidance from groups like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Even as firms may devise strategies to enhance their ESG reporting to compete in the global market, stakeholders may put pressure on businesses to reveal more ESG information.

A firm may show the public that it is not running its operations just for profit at the expense of its responsibilities to its customers, workers, the environment, and society by reporting ESG reports. There are several advantages to incorporating sustainability into business strategy and practices and enhancing sustainability reporting, including increased transparency, enhanced brand value, improved reputation and legitimacy, increased employee and customer loyalty, lower costs, better business practices, improved firm performance and valuation, and the creation of competitive advantage (Sanchez-Planelles et al., Citation2020, Menassa & Dagher, Citation2020).

Firms in developing economies are increasingly under scrutiny from owners and other interested parties who want to know more about the value they provide and the consequences of their actions for the natural world and the community. A more transparent and consistent reporting system has also been highlighted as an area of emphasis to improve the performance of firms and attract investors to the firms (Mensah et al., Citation2017). Hence, businesses are becoming more transparent about their sustainability practices and adopting stricter measures of self-regulation as a consequence of stakeholder engagement (Maama & Mkhize, Citation2020). Thus, firms’ ESG disclosure must evolve and advance due to a growing recognition that the opportunities and issues facing a firm’s long-term value are far more nuanced and complex than financial statements alone can capture.

Previous studies have paid attention to stakeholder demands since they are the primary driver of sustainability (Higgins et al., Citation2020; Lulu, Citation2021). However, none of these studies considered the mediating role of technological innovation which is a major factor of sustainability reporting. Moreover, (Ramadhini et al., Citation2020; Krasodomska & Zarzycka, Citation2021) studies were centered on developed economies using secondary data and relying on the EKC theory. To the best of our knowledge, none of the earlier studies have considered developing economies especially from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Despite the premise that, a firm can have a beneficial and adverse impact on its various stakeholder groups, few of the studies focused on stakeholder pressure and ecological reporting for developed economies. Additionally, incompatible proof exists regarding the impact of particular stakeholder demands even though previous studies have found that stakeholder pressures generally influence sustainability disclosure (Rudyanto & Veronica Siregar, Citation2018). This necessitates more investigation into the relationship between stakeholders pressures (SP) and sustainability disclosure (SD) using primary data from a developing country in SSA. Also, it is not explicit how SP affects SD in existing literature, which is an open question in this study. The few known studies have centered on transparency and the value of sustainability reports (Higgins et al., Citation2020; Lulu, Citation2021). Therefore, the goal of this study is to close a gap between existing studies by examining how pressure from stakeholders affects the degree of SD in Ghana.

This study aims to investigate how stakeholder pressure influences sustainability disclosure in Ghanaian traded firms. The unique goals of the study are identifying the influence of stakeholder pressure on sustainability disclosure in a developing economy in SSA. Establishing the impact of stakeholder pressures on green technological innovation. Examining the mediating role of green technological innovation between stakeholders’ pressure and sustainability reporting.

The theoretical inspiration of the study is rooted in stakeholder theory and institutional theory. The stakeholder theory, suggest that firms are influenced by the expectations and demands of various stakeholders, while institutional theory emphasizes the importance of external forces, cultural expectations and institutional norms in determining corporate behaviors. By incorporating these two theories shed lights on how different stakeholders influence firms’ behavior.

To better understand how stakeholder pressure affects sustainability reporting, the study relied on first-hand data and utilized the partial least squares structural equation model method. The data analysis was conducted using Smart PLS, version 4.0 which the authors have obtained a copyright license. The results revealed that stakeholder, government, and customer pressures significantly influence sustainability disclosure performance. Also, the study discovered that green technological innovation plays a significant mediating role between shareholder pressure, customer pressure, and sustainability disclosure, and an insignificant mediating role between government pressure and sustainability disclosure. The outcome of the study throws light on the different stakeholders’ pressure on sustainability disclosure and provides policy guide for businesses on which of the stakeholders’ pressure to consider so as to improve sustainability disclosure.

This study’s originality cannot be overstated; it adds to the existing work of knowledge regarding stakeholder pressure and sustainability disclosure in distinct ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between stakeholder pressures and green technological innovation has not been thoroughly examined in developing economies. This study therefore offers an in-depth insight into how green technological innovation mediates the relationship between stakeholder pressure and sustainability disclosure in a developing economy. This differs from earlier studies that only looked at the direct impact (Lulu, Citation2021, Vitolla et al., Citation2019, Ramadhini et al., Citation2020). Hence, the study bridges the gap between technological innovation adoption and sustainability practices, recognizing the pivotal role of green technological innovation in shaping a firm environmental, social and governance disclosure. This integration is crucial for contemporary businesses navigating the intersection of technology and sustainability.

Second, the study’s originality lies in incorporating both process and product innovations within the realm of green technological innovation. Many studies on ESG disclosure focuses predominantly on product innovation (Li et al., Citation2018, Jayaraman et al., Citation2023), often overlooking the significance of process innovation in contributing to sustainable business practices. This dual focus adds complexity and depth to the analysis, recognizing that a firms’ environmental and social effects and reporting can be significantly influenced by innovation in the product and the process in which it operates.

Consequently, the current paper seeks to make the following contributions to the existing literature. First by introducing green technological innovation as a mediating variable, the study contributes to a more advanced understanding of the mechanisms through which stakeholder pressure influences ESG disclosure. It goes beyond establishing a direct relationship and explores the role of technological-driven sustainability initiatives in mediating this influence.

Second, by focusing on Ghana, the study adds a contextual dimension to institutional theory, acknowledging that the regulatory and normative environment in emerging markets may differ significantly from that of developed economies, hence contributing to the broader understanding of how institutional factors interact with stakeholder pressures to shape ESG disclosure practices in a diverse global setting.

Third, the study’ inclusion of both process and product innovations as components of green technological innovation provides a holistic view. This recognition acknowledges that sustainable practices extend beyond the final product and encompasses the entire production process. Such a comprehensive perspective contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the ecofriendly initiatives within firms.

Fourth, the study’s results of a positive and significant influence of stakeholder pressure on ESG disclosure contributes empirical validation to existing literature that suggest a similar relationship. This supports and reinforces the idea that stakeholder pressure serves as a catalyst for increased transparency and disclosure in environmental social, and governance domains.

The authors divided this article into seven distinct components. Section 1 provided an introduction. Section 2 looks at the contextual factors by leveraging regulatory policies and requirements of ESG disclosure practices and advancements. Section 3 pertains to the theoretical literature review. Section 4 entails an empirical review of relevant studies, formulating hypotheses, and establishing a conceptual framework. The research design for the study is elaborated on in section five. The sixth section of the study presents the empirical results and provides a comprehensive analysis and discussion of the obtained data. The seventh section encompasses a concise summary and a sweeping conclusion.

2. Background

Recently, there has been a notable transformation in the global business environment, characterized by a growing focus on corporate responsibility and sustainability practices (Imperiale et al., Citation2023). In contemporary business evaluation, firms are no longer assessed based only on their financial success; their influence on the environment, society, and governance practices is now considered (Cicchiello et al., Citation2023). The emerging of the ESG framework has been a direct consequence of this revolution. This framework is an evaluative tool for assessing a firm’s dedication to sustainable practices and ethical conduct (Abeysekera, Citation2022).

Ghana, a country in West Africa, has seen tremendous economic expansion and advancement lately. Corporate social responsibility and sustainable practices are becoming increasingly important as the nation develops (Tetteh et al., Citation2024). Ghana’s business environment is distinguished by a blend of traditional and modern sectors, which mirrors the country’s many economic pursuits. Ghana has witnessed an increasing focus on adopting sustainable business practices, evidenced by the implementation of regulatory frameworks and policy initiatives (Wiredu et al., Citation2023). The government has been aggressively advocating for the preservation of the environment, promoting social responsibility, and implementing good governance. This phenomenon is apparent in the formulation and execution of rules and regulations designed to incentivize enterprises to embrace and divulge environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices (Faseyi et al., Citation2023). The implementation of the Ghana Green Label Certification Scheme and the regulatory measures imposed by the Environmental Protection Agency, such as environmental impact assessments, exemplify the government’s dedication to promoting environmentally sustainable business practices (Otitolaiye et al., Citation2023). The Ghana’s Securities and Exchange Commission has undertaken initiatives to incorporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors into firm reporting, thereby conforming to prevailing international patterns. Listed firms are now required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to publish their ESG practices in their annual reports (Kaur, Citation2021). The purpose of these standards is to guarantee that businesses provide stakeholders with accurate, trustworthy, and comparable ESG information (Jahid et al., Citation2023). SEC is a significant force behind promoting ESG disclosure among businesses. Firms are encouraged to provide pertinent information about their environmental effect, social activities, and corporate governance practices using rules and regulations published by the SEC (Annan, Citation2023).

Ghana has undergone economic reforms to attract foreign investment and promote sustainable investment. These reforms are initiatives to enhance accountability, transparency, and corporate governance (Anaman et al., n.d.). Ghana’s business community increasingly realizes the importance of following global best practices to boost competitiveness and access outside markets (Simpson et al., Citation2022). Hence, ESG disclosure in Ghana goes beyond merely abiding by the rules and regulations (Annan, Citation2023). It is an opportunity for firms to show that they are dedicated to sustainability, ethical business conduct, and generating long-term value for all parties involved. Firms may improve their reputation, draw in socially aware investors, and support Ghana’s general sustainable growth by providing ESG information. ESG disclosure is an essential aspect of corporate transparency and accountability in Ghana (Appiah-Konadu et al., Citation2022). It enables firms to communicate their commitment to environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and strong corporate governance practices. The increasing desire for openness and stakeholder accountability is a crucial driving force behind adopting ESG disclosure practices in Ghana (Aboagye‐Otchere et al., Citation2020). There is a growing emphasis among investors, consumers, workers, and the general public on the environmental and social consequences of organizations alongside their governance strategies (Faseyi et al., Citation2023). Ghanaian enterprises acknowledge the need to cultivate trust, maintain a favorable image, and attract enduring investments by disclosing their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance (Jahid et al., Citation2023).

Moving forward the nation has a profound cultural legacy that places importance on active participation within society, managing the environment, and fulfilling social obligations (Welbeck, Citation2017). Numerous Ghanaian enterprises acknowledge the significance of harmonizing their operational strategies with prevailing cultural norms (Arthur et al., Citation2017). Consequently, they place a high priority on disclosing their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices as a means to showcase their dedication to fostering sustainable development. In addition, it is noted that some sectors, including mining and agriculture, substantially influence the natural environment and nearby populations (Amoako et al., Citation2022). These sectors are seeing heightened scrutiny to publicly report their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and address adverse social and ecological consequences (Famiyeh et al., Citation2021).

3. Theoretical literature review

In the following sub-sections, the theoretical justification is presented.

3.1. Stakeholder theory (ST)

Stakeholder theory is one of the most common ideas to explain why firms report on ESG issues. The stakeholder theory states that businesses have duties to all other stakeholders interested in the business besides owners, whose only goal is to make as much profit as possible (Freeman, Citation1984). According to stakeholder theory, this goal cannot be reached by ignoring the needs of other stakeholders. This means that while firms are responsible to their investors or stakeholders, they must also balance the interests of many different stakeholders whose actions can affect or be affected by the firms’ actions (Dissanayake et al., Citation2019). To demonstrate to stakeholders that their expectations are being acknowledged, firms actively participate in and provide an account of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) matters. This may be done by including it in the annual reports or by producing separate sustainability reports (Abeysekera, Citation2022). Businesses strive to minimize information asymmetry by reporting non-financial matters such as social and environmental activities and repercussions to convey ESG information effectively (Alsahali & Malagueño, Citation2022). ESG reporting is used as a means of actively involving various stakeholder groups that are considered vital for the organization’s ongoing operations.

Organizational managers are compelled by stakeholder theory to respond more quickly to the outside world’s demands. Thus, stakeholder theory states that firms should act in a good and fair way towards stakeholders’ expectation, based on what the stakeholders think is right. It builds on legitimacy theory, which also focuses on firms behaving ethically (Osei et al., Citation2023). Stakeholders lead organization managers by advising them on how to live the firm’s values (Wen et al., Citation2023). This orientation helps them discern between right and sinister. Stakeholders provide an orientation to help firms preserve and maintain the quality of life while continually improving it, such that it becomes critical to how businesses approaches the environment in their operations and disclose sustainability information (Zhou et al., Citation2022).

According to stakeholder theory, businesses should prioritize cultivating positive relationships with all stakeholders (Osei et al., Citation2019). Thus, firms may be prompted to adopt and release sustainability reports in response to pressure from stakeholders. The firm’s sustainability reports are meant to be comprehensive sources of data on how the business’s operations affect the local community and the natural environment. Firms declare their efforts towards the global objectives as a means of discharging their responsibilities and gaining the approval and support of stakeholders.

Studies related to ESG often use ST as an important theoretical framework. According to Agyemang et al. (Citation2023b), to ensure firm sustainability, the firm must meet the expectations of its associates. The intricacy of ESG issues requires the involvement of many different parties if effective or sustainable answers are to be devised (Freudenreich et al., Citation2020). As a result of competing interests, leaders often must decide which ones to prioritize, ignore, back, or fulfill. Stakeholder interest balance is thus an important aspect to firms.

3.2. Institutional theory

Institutional theory provides a holistic explanation on why a firm chooses a specific structure or method of reporting. Businesses whose principal activity is linked with greater ecological effects, like the mining sector, undergo greater pressure to operate ethically in the manner they do business than those with fewer ecological consequences (Simoni et al., Citation2020).

According to institutional theory, entities within the same field tend to grow increasingly similar to one another due to the pressures they face, which include adopting institutional as well as social norms and standards to gain legitimacy to preserve access to resources. Isomorphism is a term used to describe this kind of standardization, and several types have been identified by: coercive (regulatory), mimetic (competition), and normative (market) (Kılıç et al., Citation2021).

Coercive isomorphism arises when a firm is subjected to pressure from outside sources, such as shareholders or employees, or from the national decision and laws to alter its long-standing institutional norms (Herold, Citation2018). A firm may engage in mimetic isomorphism if its leaders believe that doing so would provide them an edge in the marketplace (Kılıç et al., Citation2021). One example of this is the adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting. Firms around the world are increasingly turning to the GRI standards for SD as an example of normative isomorphism, which refers to the pressure to implement organizational practices resulting from shared beliefs, typically from clients or vendors who require compliance with ecological and social standards (Tran & Beddewela, Citation2020).

According to institutional theory, a firm’s corporate strategies are significantly impacted by its institutional environment, which consists of its rules, conventions, and social beliefs (Posadas et al., Citation2023). Nonetheless, this idea is comparable to the strategy supported by legitimacy theory. Similarly, Simoni et al. (Citation2020) argued that, businesses must adhere to regional social norms, values, and beliefs to prosper. Building on this idea, institutional theory represents that a firm’s activities, efforts, and reports may lead to stakeholders having certain expectations. Therefore, implementing sustainability practices means abiding by laws, social conventions, and values to enhance or preserve a firm’s reputation among stakeholders (Alatawi et al., Citation2023).

4. Empirical review and hypotheses development

4.1. Stakeholder pressure and sustainability disclosure

The study of the factors that influence sustainability reports from businesses might benefit from the theoretical groundwork provided by stakeholder theory. According to stakeholder theory, managers may use stakeholders’ expectations (or output restrictions) as a benchmark for environmental performance when they see widespread consensus on the importance of environmental concerns (Sarkis et al., Citation2010). Efforts to incorporate environmental concerns and practices into strategic, tactical, and operational actions have increased as a response of rising challenges. Similarly, the legitimacy theory argues that businesses’ social practices should emphasize how firms respond to community expectations. As a result, a firm may need to explain how its actions align with social values since the community or stakeholders may react negatively, especially when there are discrepancies between firm and societal values (Alatawi et al., Citation2023). Therefore, businesses must adapt to societal demands to uphold their social standing and cultivate a relationship based on trust with stakeholders. Firms can better anticipate societal concerns by disseminating and publishing information about their sustainability issues in publicly accessible reports (Alatawi et al., Citation2023).

Stakeholder theory was considered by Sarkis et al. (Citation2010) while analyzing the implementation of sustainable measures in the Spanish automobile sector. Their results suggested that stakeholders may have varied effects given the particular scenario under consideration. Thus, there is a significant association between environmental demands across stakeholders and various groups’ stakeholder pressures on sustainability practices.

Every decision made by the firm is a direct reflection of the majority shareholder’s desires (Raub & Martin-Rios, Citation2019). Therefore, shareholders need to exercise effective oversight of the firm’s management to decrease instances of concealing information and promote more comprehensive disclosures. Firms are being pushed to consider their broader social and environmental impacts as a result of shareholder pressure on sustainability, which is a welcome trend.

Investors are beginning to see the potential of sustainability as a tool for creating a more equal and just society as well as a safer and more prosperous one. As a consequence, stakeholders are utilizing their voting power and other forms of influence to pressure businesses to improve their ESG effectiveness (Cadez et al., Citation2019, Lee et al., Citation2018). The results by Chithambo et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate that stakeholder pressure, as represented by environmental, consumer, employee, and shareholder pressures, significantly affect the environmental performance of manufacturing businesses listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (ISE).

Government regulations are crucial factors for businesses to consider. Permits for doing business, labor laws, and other requirements have all been promulgated by various state institutions. As a result of increased public scrutiny and demands transparency, state authorities are putting pressure on business leaders to provide sustainability reports (Lestari et al., Citation2021). The government and regulations may use a variety of tools to encourage businesses to take environmental protection measures. The advent of emission limits and environmental programs has put considerable regulatory pressure on many businesses in developed countries. Without the effect of legislation to force their acceptance, certain industries, like the energy industry, would not even be in existence. The use of force is often implicit in regulatory efforts. Because of the risk of fines, jail time, or other legal repercussions, businesses are compelled to comply with legal pronouncements by instituting internal sustainability policies that reduce emissions, resource usage, and waste during production (Esfahbodi et al., Citation2017). Moreover, rules place stress on businesses by necessitating the development of organizational responsibility reports that detail the infirm of external and internal sustainability measures. Hence, it stands to reason that coercive constraints from governments and regulators would have a detrimental impact on supplier sustainability cooperation, although some academics have claimed otherwise (Talbot et al., Citation2021).

Customers are often regarded as the most influential stakeholder group (Chithambo et al., Citation2022). The ecological impact of products is increasingly communicated to consumers. Ecologically conscious customers are willing to pay more for green items that are offered by firms with a strong ecological reputation. So, there is an incentive for suppliers to implement sustainable practices to enhance their market performance and meet the needs of their customers. Customers on the B2B level often mandate that vendors have environmental certifications like ISO 14000. Recent studies by Gong et al. (Citation2019) shows that consumer demands are crucial for encouraging businesses to build their sustainability capabilities and communicate sustainability to their supply chain collaborators through the use of various stakeholders’ pressure. Thus, it is anticipated that the adoption and execution of both inside and outside green initiatives would be favorably impacted by demands from customers. According to studies conducted by Ramadhini et al. (Citation2020), external stakeholders, such as creditors and the media, impact social and environmental disclosure. In addition, studies by Fernandez-Feijoo et al. (Citation2014) found that pressure from specific stakeholder groups—including customers, clients, employees, and the environment—raises the bar for report openness.

Based on the above literature, the following hypotheses are developed:

H1. Shareholder pressure significantly influences sustainability disclosure.

H2. Government pressure has a positive and significant influence on sustainability disclosure.

H3. Customer pressure has a positive and significant link with sustainability disclosure.

4.2. Stakeholder pressure and green technological innovation

The institutional theory focuses on how the outside world affects green technologies. Green innovation may be seen from the perspective of analytical logic as a method of dealing with the demands of the customers and regulatory pressure. The goal is to make businesses adhere to social norms, regulatory requirements, and public perception (Berrone et al., Citation2013).

Studies conducted by Rui and Lu (Citation2021) used a sample of 278 businesses to explore the driving mechanism of stakeholders’ regulatory, normative, and imitation pressures on firms’ green innovation, respectively. These three types of pressure come from the government, consumers, and rivals. The results of hierarchical regression analysis indicate that pressure from stakeholders may improve the environmental ethics of firms and the development of green technology. Similarly, Tian and Tian (Citation2021) conducted a study to examine how green innovation emerges and affects a firm’s environmental performance. The empirical study results using 306 firms sample data demonstrate that stakeholder pressure favors firm sustainability performance and that responsible innovation is a partial mediating factor in this connection. In addition to confirming the logic of stakeholder theory, which predicted that stakeholder pressures would have a significant impact on firms’ decisions about green innovation (Cadez et al., Citation2019, Lee et al., Citation2018), this finding also extends it by illuminating the heterogeneous influences of various stakeholder pressures on green product innovation.

Following to the stakeholder theory, organizations should prioritize meeting the demands and expectations of all constituencies rather than just those of shareholders with financial stakes (Freeman, Citation1984). Hence, firm now includes green innovation strategies in its policies. Shareholder pressure on sustainability describes the rising movement of shareholders, notably institutional shareholders, to require businesses to disclose their ESG results and prioritize green technological innovations initiatives. As a consequence, shareholders are utilizing their voting power and other forms of influence to pressure businesses to improve their green technological innovation (Kılıç et al., Citation2021). Thus, firms are being pushed to consider their broader social and environmental impacts as a result of shareholder pressure on green technological innovation adoption, which is a welcome trend.

Government pressure often describes governmental restrictions upon businesses, like environmental laws. Businesses must cease engaging in environmentally harmful activities and adopt green technological innovation practices to avoid government penalties and preserve regulatory flexibility. Numerous studies have supported this idea. For instance, it was discovered via a study of 92 industrial firms in Germany that the rigor of statutory ecological rules increased the possibility of implementing green innovation (Kammerer, Citation2009). In order to compete internationally, businesses must also adhere to international environmental conventions. As a result, adopting green technological innovation will directly depend on how stringent the regulations are and how the firms perceive them.

According to the stakeholder theory, customer pressure and regulations may spur businesses to adopt green technological innovations. Firms may satisfy customers’ expectations and requests to lessen their ecological effects by introducing green technological innovation products and green processes. According to Lin and Ho (Citation2011), consumer pressure is the degree to which consumers anticipate or pressure businesses to enhance their environmental performance—it has been recognized as a critical factor in adopting green innovation by firms. In the study by Lestari et al. (Citation2021) on the effects of consumer demand and environmental legislation on green innovations, customer pressure has a very beneficial impact on green technological innovation performance. Also, Lulu (Citation2021) discovered a more prominent favorable association between consumer pressure and the businesses’ environmental initiatives. In a similar vein, third-party logistic providers’ green developments were seen to be primarily influenced by consumer pressure (Chu et al., Citation2019). According to the results of empirical study done by Esposito De Falco et al. (Citation2021), contractual stakeholders have a more significant influence on environmental innovation. It is also discovered by Jayaraman et al. (Citation2023), that stakeholders such as employees, suppliers, government regulations, and customers significantly impact an organization’s sustainability performance, particularly regarding green technological innovation initiatives indicating that stakeholders play a vital role regarding the implementation of green innovation and believe such an act could help in minimizing environmental impact. A further study has supported that the influence of stakeholders on do impact firms in adopting green innovation (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Therefore, we hypothesize that;

H4. Shareholder pressure has a significant impact on green technological innovation.

H5. Government pressure has a significant impact on green technological innovation.

H6. Customer pressure has a significant impact on green technological innovation.

4.3. The mediating role of green technological innovation (GTI)

GTI describes the creation and widespread use of new technologies that help preserve the planet (Zhang et al., Citation2020). New products, processes, or services developed to lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, conserve natural resources, and advance sustainable development are examples of such innovations. The utilization of renewable energy sources, for instance, may assist to decrease GHG emissions and prevent climate variability, while green building methods can help to lessen the ecological effect of the construction (Agyemang et al., Citation2021). Innovation in environmentally friendly technologies is crucial to long-term viability since it helps mitigate adverse environmental impacts while also opening up lucrative new markets. Thus, reducing carbon emissions, preserving natural resources, and encouraging eco-friendly practices across sectors are all ways in which green technical innovation contributes to sustainability (Raihan, Citation2023). By facilitating the development and adoption of sustainable practices across sectors, GTI has a major impact on environmental sustainability.

Due to pressure from stakeholders and regulatory standards, firms adhere to pollution reduction, energy efficiency policies, and other environmentally conscious practices (Amoah & Eweje, Citation2020). By adopting and promoting sustainable technologies, enterprises can fulfill stakeholder expectations and actively contribute to global endeavors to address and mitigate the effects of climate change (Cadez et al., Citation2019). The application of advanced carbon capture and storage technologies has made it possible to store carbon dioxide emissions from power plants and industrial processes (Dhanda et al., Citation2022). This responds to stakeholder demand for concrete action to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change by preventing the release of carbon dioxide.

Stakeholders’ advocacy for sustainability drives the heightened utilization of renewable energy sources such as solar and wind (Cadez et al., Citation2019) and investment in carbon capture and storage innovations to reduce their carbon footprint by absorbing and storing carbon emissions, hence improving the quality of the climate (Cadez & Guilding, Citation2017). An empirical study by Seroka-Stolka (Citation2023) revealed a positive correlation between stakeholder pressure and the implementation of decarbonization strategies and performance linked to carbon emissions. From the standpoint of stakeholder theory, corporations operating in industries that significantly affect global warming are subject to greater public scrutiny. As a result, these firms are more inclined to disclose their performance in addressing climate change in response to demand from stakeholders (Liesen et al., Citation2015, Cadez & Czerny, Citation2016). Hence, it is hypothesized that:

H7. Green technological innovation mediates the association between shareholder pressure and sustainability disclosure.

H8. Green technological innovation mediates the link between government pressure and sustainability disclosure.

H9. Green technological innovation facilitates the link between customer pressure and sustainability disclosure.

5. Methodology

5.1. Research design

Using a quantitative research methodology, the study investigated the influence of stakeholder pressure on ESG disclosure. We utilized primary data since it has higher validity due to its lack of human involvement, enhanced interpretation, attention to pertinent research questions, and data decency (Wiredu et al., Citation2023). Survey questions were created to collect data for the study. A five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, was used in the surveys. It was done to meet the study’s goals. Before the pilot test, an instrument pre-test was carried out after creating the questionnaire. The questionnaire underwent advanced pilot testing by consulting experts on the test items. They provided insightful feedback that helped to improve the questionnaire’s content. The purpose of this process was to guarantee the authenticity of the information. A pilot test was conducted after revisions to the questionnaire based on experts’ input.

The data collected was analyzed using smart PLS version 4.0. The study employed the PLS-SEM for the analysis because it is successful with small sample numbers and makes no presumptions regarding the data being analyzed (Sarstedt et al., Citation2019). Also, the PLS-SEM offers greater statistical validity than CB-SEM because it is well-known for its skill while estimating parameters.

5.2. Population and sampling

We used firms Ghana as the study population. Ghana, which is located in the Western part of Africa, was selected for the study due to the stable socio-political regime, hence, promoting smooth running of businesses (Sare et al., Citation2023). To enable the authors select a sample size, purposive sampling approach was used to identify 457 mining (including quarry firms) and manufacturing firms in Ghana that have at least 50 employees. These mining and manufacturing firms were chosen because their processes are known to release carbon dioxide, create waste, and need the use of natural resources like minerals and forests (Wiredu et al., Citation2023). Firms in the service sector and small businesses were excluded from this study since their business activities do not directly influence environmental challenges. The managing director for each of the identified 421 firms constituted the respondents for the study. Out of the 421 identified respondents, twenty-six of the selected firms declined to partake in the study, whereas, twelve responses were considered as incomplete, hence, were excluded from the study. Therefore, the final sample used for the study was 383 respondents. provides summary of the population and sample size used for the study.

5.3. Operational definition of study constructs

In this investigation, sustainability disclosure serves as the dependent variable. Shareholder, government, and customer pressures are the independent constructs. Green technological innovation is the mediating variable.

5.3.1. Dependent construct

Sustainability disclosure is the act of disclosing environmental-related information to the public (Lulu, Citation2021). The goal of sustainability disclosure is to provide stakeholders with accurate and transparent information about firm’s sustainability-related initiatives and advancements. Sustainability information disclosure may come in various formats such as reports, statements, and statistics.

5.3.2. Independent constructs

5.3.2.1. Shareholder pressure

Shareholder pressure is the power used by people or organizations that own stock in a firm to persuade the firm to implement more environmentally friendly procedures (Tian & Tian, Citation2021). A shareholder’s strategy might include voting on resolutions pertaining to ESG issues, conversing with management, or pulling out investments from firms that fall short of their sustainability standards.

5.3.2.2. Government pressure

Government pressure is the measures the national and local governments use to encourage sustainability and control corporate conduct (Rudyanto & Veronica Siregar, Citation2018). This might include passing legislation and establishing rules for labor laws, CSR, and environmental protection. Governments may also push firms to adopt more environmentally friendly practices by offering financial rewards or penalties.

5.3.2.3. Consumer pressure

Consumer pressure arises from the wants and preferences of people who buy products and services (Lestari et al., Citation2021). Consumers are becoming more concerned about the ecological and social consequences of purchasing things. They may buy from firms committed to sustainability or participate in activism or boycotts to change corporate behavior.

5.3.3. Mediating construct

5.3.1 Green technological innovation (GTI) entails creating and implementing new technologies and processes that improve environmental sustainability (Chu et al., Citation2019). These technologies attempt to save resources, decrease pollution, and contribute to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly society. A process and product innovation are examples of green technological innovation

5.4. Measurement of study constructs

The authors employed a validity survey instrument adapted from previous studies to assess the study constructs. In order to guarantee validity and reliability, questionnaire indicators should be modified from existing studies. To measure sustainability disclosure, we utilized a measurement developed by Truant et al. (Citation2017; Chege & Wang, Citation2020). This scale incorporates indicators related to Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), comprising various aspect of ESG practices. To measure shareholder pressure, we employed measurement developed by Rudyanto and Veronica Siregar (Citation2018), which includes items such as shareholder activism, shareholder engagement meetings. This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity. The measurement of government pressure was adapted from the study of (Mooneeapen et al., Citation2022; Zhang & Zhu, Citation2019). The scale consists of items such as regulatory compliance, legislative initiatives and policy changes. We assessed customer pressure using a scale adapted from (Zhang & Zhu, Citation2019), which comprises items such as customer feedback and complaints, customer surveys on ESG issues and customer-requested ESG reporting. To measure green technological innovation, we utilized the scale from (Wang et al., Citation2022; Mukhtar et al., Citation2023), consisting of items such as investment in green research and development. This scale has been validated in prior studies within the context of technological innovation.

A total of four indicators were used to assess sustainability disclosure, stakeholder and customer pressure while three items are used to measure government pressure and green technological innovation.

To measure the study constructs, an interval scale is employed. The study constructs that were regarded as dimensions were measured using a Likert scale. The questionnaire statements were created once the indicators have been identified. A Likert scale was used to evaluate the attitudes, opinions, and perceptions of management with stakeholders’ pressure about sustainability disclosure. From strongly disagree to strongly agree, a Likert-type instrument offers a range. presents the summary of the study constructs. The detailed constructs is provided in Appendix A.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Measurement model

We first assessed the study’s results by verifying the convergent validity, discriminant validity, and internal consistency dependability of the assessment of the outer model. This was done before making a call on whether or not both convergent and discriminant assumptions hold (Sarstedt et al., Citation2021).

6.1.1. Indicator reliability

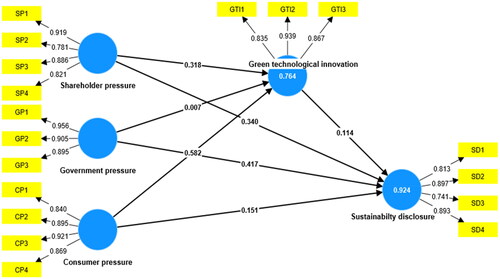

When assessing reflective measurement models, indicators are considered reliable when their loadings are more than 0.708, which implies that greater than 50% of the indicator’s variance can be explained by the latent variables. According to Hair Jr et al. (Citation2021), indicators with loadings below 0.40 be routinely deleted from the measurement model. depicts that all the loading values of the indicators were over the minimum threshold, indicating that the indicators offered a meaningful assessment of the latent variables or the items used in the research are dependable.

6.1.2. Internal consistency reliability

According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), the composite reliability numbers need to be greater than 0.60 to reliably evaluate internal consistency. The external factors loading analysis suggests that the indicator’s reliability has to be greater than 0.60. The results of the construct reliability are presented in .

The composite dependability values of the results, displayed in , range from outstanding (0.869) to good (0.929). Rho_A is a dependableness metric that has gained popularity as an alternative to composite reliability. Rho_A should ideally be around about 0.70. All the constructs have Rho_A value above 0.70, as shown in . The investigation complies with the internal consistency criteria because the Cronbach’s alpha scores and composite reliability scores for each variable were greater than the advised value of 0.7. Hence, the data is verified and reliable.

6.1.3. Convergent validity

The examining of the typically extracted variance is the first step toward establishing convergent validity (AVE) (Hair et al., Citation2014). To test for convergent validity, statisticians employ the AVE. AVE is a measure of convergent validity, underscoring the proportion of variance in the observed variables that is captured by the underlying construct. According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), an AVE of 0.50 or greater is preferable. During convergent validity testing, the AVE results are then analyzed in depth. The AVE threshold value is 0.50. The minimum AVE for the constructs was 0.703. Therefore, convergent validity is satisfied. displays the computed AVE values.

6.1.4. Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity illustrates the fact that relationships between constructs that logically should not exist occur. We evaluated the discriminant validity using the standards established by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) in . The square root of AVE values was shown to have the strongest correlation with the latent variable across all indicators and constructs in this study. The largest numbers in the columns as well as the rows are shown in bold numerals, which are also visible. Each set of factor coefficients was less than the square root of the AVE, which shows that discriminant reliability is not an issue (Hair et al., Citation2010). In a nutshell, the factors that were looked at have a strong ability to separate. Based on the results, we can say that this situation satisfies the requirements of discriminant validity. presents the results of the discriminant validity.

6.2. Structural model

The coefficient of determination (R2), variance inflation factor and path coefficient are examined to show the fitness of the structural model.

6.2.1. Multicollinearity

Examining the variance inflation factor values for each of the several measurements allowed us to gauge the degree of multicollinearity. From the results in , there was no multicollinearity in the model since the collinearity VIF values for all independent variables were less than 3.3.

6.2.2. Path significance

We performed a bootstrapping operation in Smart-PLS to determine the importance of the model using a substantial value of 5000 subsamples and a 0.1 two-tailed distribution. The bootstrapping method is applied to obtain T-statistics for studying both direct and indirect impacts (Hair et al., Citation2019). The SEM technique’s outcomes, which provide the pathways, beta values (coefficients), t-statistics, and p-values, make it more appropriate for both complicated and straightforward models (Hair et al., Citation2010). Some of the hypotheses are confirmed by the data in , while others are refuted.

According to results about the direct relationship between the study’s constructs, pressure from customers has a significant direct influence on sustainability disclosure. This finding supports the authors hypothesis. In addition, the study results revealed a positive and significant relationship between consumer pressure and green technological innovation. This affirmed hypothesis H4. The result indicates that customers pressure plays a key role in influencing firm green technological innovation adoption and sustainability disclosure practices. Moreover, government pressure has a positive and substantial influence on sustainability disclosure, which was in line with the study’s assumption. This implies that a percentage change in pressure from the government will increase sustainability disclosure by 0.417. However, government pressure has an insignificant effect on GTI. This outcome denied the authors hypothesis that government pressure has a significant influence on GTI. This implies that pressure from the government had an insignificant effect on firms’ adoption and implementation of GTI initiatives.

Additionally, shareholder pressure revealed a significant and favorable impact on the disclosure of sustainability information by mining and manufacturing firms in Ghana. Therefore, it is scientifically proven that shareholder pressure has a positive and considerable influence on ESG, indicating that 1% increase in the coefficient of shareholder pressure will boost sustainability disclosure of firms by 0.340. Also, shareholder pressure revealed a significant and substantial effect on green technological innovation, validating H5. This means that a percentage increase in pressure from shareholder will lead to an increased in GTI initiatives by 0.318. Similarly, according to results, GTI significantly influence sustainability disclosure, showing that a 1% increase in GTI will escalate firm sustainability disclosure by 0.114.

In , the mediation results demonstrate that the GTI had a substantial mediating influence between shareholder pressures and sustainability disclosure, as well as, between customer pressure and sustainability disclosure. This implies that, pressure from shareholders and consumer has a significant indirect impact on sustainability disclosure through green technological innovation. On the other hand, GTI showed a negligible mediation effect is observed between government pressure and sustainability disclosure denying the hypothesis 8. This clearly indicates that green technological innovation does not influence the relationship between government pressure and sustainability disclosure.

6.2.3. Goodness of fit

After evaluating the importance of the path coefficient in the structural model, we determined the model’s goodness of fit (GOF). The R-square (R2) determination coefficient is the most widely applied criterion. According to Sahoo. (2019), R2 quantifies the explanatory power of the model. In general, R2 values of 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 are regarded as weak, moderate, and significant, respectively (Sahoo, Citation2019). According to Hair (Citation2020), R2 values fall into three categories: average (0.333), weak (0.190), and approximately large (0.670). displays the constructs’ predictive power, as well as how effectively the explanatory variables of the model forecast results. For green technology innovation and sustainability disclosure, the results revealed a predictive capacity (R2) of 0.764 and 0.924, respectively.

6.2.4. Effect sizes

Effect sizes quantify the degree to which an independent construct influences the dependent construct. An independent construct, or exogenous latent variable, has a little, medium or high effect on the dependent construct, with values falling between 0.020 and 0.150, 0.150 and 0.350 and 0.350 and above 0.350. Therefore, from the independent constructs have varied effect on green technological innovation and sustainability disclosure.

6.3. Discussion

Sustainability disclosure practices can be influenced by stakeholder pressure. Successful ecological sustainability is contingent upon interactions with businesses and constituents. As per the stakeholder theory, a firm’s relationship with its stakeholders is enhanced by its steadfast commitment to ecological initiatives or activities (Wiredu et al., Citation2023).

Some previous studies have uncovered a positive and beneficial relationship between stakeholder pressure, green technology, and sustainability disclosure (Thomas et al., Citation2022; Lulu, Citation2021). For instance, Chithambo et al. (Citation2022) suggested that institutional shareholders affect a firm’s ESG performance, which is essential for long-term corporate sustainability. Given the purpose of the research, the study hypothesize that shareholder pressures have positive and substantial effects on sustainability disclosure. The analysis of the results confirmed that shareholder pressure is positively associated with sustainability disclosure. This implies that shareholders with voting rights can influence the executive decision to include ESG-related information in annual reports in order to enhance the firm’s image and economic viability over the long term. Our results were consistent with the assumption. Hence, the first hypothesis was accepted. Our result supports the stakeholder theory, which states that business entities have an obligation to all other groups or stakeholders who have a vested interest in the business apart from shareholders, and to fulfill this objective, firms engaged and disclosed information related to ESG to meet the requirement and interest of other stakeholders. Moreover, our results is consistent with the results by Rui and Lu (Citation2021), who concluded that shareholder pressure significantly affects the environmental performance of manufacturing businesses listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

The government has the power to impose rules that must be adhered to by all parties, including pressure to disclose sustainability information. Thus, government regulations may exert pressure on the business to publish sustainability reports. According to the institutional theory, firms may provide an increasing amount of ESG data to comply with legal requirements, avoid fines from environmental authorities, and legitimize their business practices (Posadas et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the study assumed that government pressure has a positive and significant influence on sustainability disclosure. This hypothesis is supported by the significance of the path coefficient results. Hence, the second hypothesis is accepted. The study’s results are consistent with (Eryadi et al., Citation2021) assertion that government pressure significantly improves the publication of sustainability reports.

As stated in the hypothesis, customer pressure is positively related with sustainability disclosure. This is evidence to the legitimacy theory, which posits that firms report more on environmental, social, and governance issues to support and justify their continued existence (Orazalin et al., Citation2023). Businesses that want to compete in the global market may enhance their ESG reporting to draw in and keep environmentally conscious customers. Due to the fact that businesses with a high degree of consumer proximity tend to be more distinctive and are most likely to influence other businesses to fulfill their social and environmental obligations. These results indicate that consumers are extremely concerned with the quality of the products and services they purchase. In addition to purchasing affordable goods or services from a firm, consumers also pay attention to the product’s environmental friendliness, labor conditions, and other sustainability performance factors. Hence, the assumption is accepted.

With regards to the relationship between stakeholders’ pressure and green technological innovation. We assumed that shareholder pressure has positive a significant impact on green technological innovation. The results of this study validated this hypothesis. This result aligns with an empirical study by Singh et al. (Citation2022), which shows that stakeholders put pressure on green innovation capability. Shareholders may encourage managers to implement and practice green innovation since customers are interested and ready to pay more for environmentally friendly products. This will boost the economic performance of the firm as well as shareholders’ return on investment.

Also, the author hypothesized that government pressure has a positive and significant relationship with green innovation. This claim is not supported by the study results. This may be as results of no governmental rules and regulations binding firms to adopt green technological innovation in their production process.

A positive association between consumer pressure and green technological innovation is assumed as part of the study’s hypothesis. Path significance results supported the hypothesis. Given that customers may alter their consumption patterns from everyday goods to green technological or environmentally friendly products, they may do so. Many consumers are reticent to pay an extra cost or switch to a different product solely because a product is eco-friendly. In response, businesses may enhance green technological innovation to keep and attract additional consumers. An empirical piece of evidence indicates that customer pressure encourages firms to implement green innovations and has been shown to increase competition due to products that are distinct from competitors and enhance product image and firm credibility (Chu et al., Citation2019).

Further, varying results are achieved concerning the mediating roles of green technological innovation. The study results revealed that green technological innovation does not mediate the relationships between government pressure and sustainability disclosure. This finding disapproved H7, which assumed that green technological innovation moderates the relationship between shareholder pressure and sustainability. However, the study results revealed that green technological innovation mediates the relationship between shareholder pressure, customer pressure and sustainability disclosure, validating H8 and H9. This conclusion is in line with the empirical results of a study by Xu et al. (Citation2022), which found that the relationship between CSR and ecological performance is positively and significantly mediated by green technology innovation.

7. Summary and conclusion

We examined the extent to which firms in Ghana disclose information regarding sustainability. Specifically, we investigated the influence of stakeholders’ pressure on sustainability disclosure, with green technological innovation serving as a mediator. 383 out of 421 identified respondents from various mining and manufacturing firms in Ghana submitted valid responses to the survey questionnaire.

The results of the article demonstrated that stakeholder pressure (shareholder pressure, government pressure, and consumer pressure) a have a significant influence on firms’ ESG disclosure. Moreover, the results demonstrate that a firm’s GTI mediates the connection between stakeholder pressure in terms of shareholder pressure and consumer pressure. Nonetheless, the study revealed that GTI played a negligible mediating role between government and ESG disclosure.

It is therefore recommended that product development managers implement new technologies and techniques, as well as to consider eco-friendly initiatives. Incorporating GTI into the product design and manufacturing process enables firms to not only fulfill their client’s needs but also reduce their environmental impacts, like the production of carbon dioxide and solid debris. Also, to enhance firms’ reputations, businesses should take the necessary steps, such as using eco-friendly flora, preparing annual integrated reports, and disclosing sustainability information, to resolve society and other parties’ issues.

The study made the following contributions: First, by including green technology innovation as a mediating variable, the study advances our knowledge of the mechanisms influencing ESG disclosure through stakeholder pressure. Secondly, this study adds a contextual dimension to institutional theory by looking at Ghana. It recognizes that emerging markets’ regulatory and normative environments may differ significantly from developed economies. This helps us understand how institutional factors interact with stakeholder pressures to shape ESG disclosure practices in a diverse global setting. Thirdly, the study provides a holistic view by looking at process and product innovation as parts of green technology innovation. This recognition acknowledge that environmentally friendly practices cover more than just the finished product; they also include the production processes. This broad view helps us understand the eco-friendly efforts in businesses more complexly.

7.1. Policy implication

The study’s results have numerous implications for decision-makers, executives at businesses, regulatory agencies, and other stakeholders. First, through stakeholder pressure and GTI initiatives, the study offers a vital understanding of the steps that must be taken to improve sustainability disclosure. Since ecological issues are of greater worry for ecological pressure organizations, the community, as well as authorities for regulation as a whole, the study recommends that businesses evaluate the demands or interests of stakeholders when making business decisions. The prioritization of stakeholder demands and interests by businesses not only facilitates their attainment of a common competitive advantage and compliance but also facilitates their achievement of improved sustainability disclosure performance.

Moreover, regarding strategic decision-making, Ghanaian businesses may use the study results to guide strategic decision-making processes, recognizing the influence of stakeholder pressure on ESG disclosure practices. Policymakers may utilize the results to develop ESG transparency interventions for various firms. The inclusion of stakeholder expectations into strategic decision-making processes has the potential to improve stakeholder interactions, hence contributing to a firm commitment to climate protection.

7.2. Limitation and future research

This research has its drawbacks. First, data were gathered from managing directors of selected mining and manufacturing firms in Ghana, with no other countries or regions considered. Therefore, the research cannot be generalized regionally. Hence, future research should consider multiple nations. Secondly, the pressure exerted by stakeholders is measured using only three dimensions (shareholder, government, and customer pressures). Other forms of stakeholders’ pressure such as employee and creditor pressure were not considered. Future research should consider adding other forms of stakeholder pressure that possibly influence sustainability disclosure.

Third, given that the study did not include any moderating variables, it limits the ability to investigate the potential nuanced effects and interactions. Several factors, including organizational culture, regulatory environment, and industry characteristics, have the potential to impact the link between stakeholder pressure and ESG disclosure which were not considered in this study. Hence, future studies should consider these variables.

Fourth, there were no control variables in the study, which means there is a possibility of bias caused by missing factors. There may be factors that need to be considered that influence both stakeholder pressure and ESG disclosure, which confounds the link that has been seen. It is recommended that future studies consider including relevant control factors to make the results more reliable.

Author contributions

Noha Alessa: conceptualization & design; methodology; analysis & interpretation; drafting of the paper; revising it critically for intellectual content. John Yaw Akparep: conceptualization & design; methodology; analysis & interpretation; drafting of the paper; and revising it critically for intellectual content. Inusah Sulemana: conceptualization & design; analysis & interpretation; methodology; drafting of the paper; and revising it critically for intellectual content. Andrew Osei Agyemang: conceptualization & design; methodology; analysis & interpretation; drafting of the paper and revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The study relied on primary data that were collected through the administration of questionnaire from management of manufacturing businesses in Ghana.

References

- Abeysekera, I. (2022). A framework for sustainability reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(6), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-08-2021-0316

- Aboagye‐Otchere, F. K., Simpson, S. N. Y., & Kusi, J. A. (2020). The influence of environmental performance on environmental disclosures: An empirical study in Ghana. Business Strategy & Development, 3(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.81

- Agyemang, A., Yusheng, K., Kongkuah, M., Musah, A., & Musah, M. (2023a). Assessing the impact of environmental accounting disclosure on corporate performance in China. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, 22(2), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.30638/eemj.2023.030

- Agyemang, A. O., Yusheng, K., Twum, A. K., Ayamba, E. C., Kongkuah, M., & Musah, M. (2021). Trend and relationship between environmental accounting disclosure and environmental performance for mining companies listed in China. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(8), 12192–12216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01164-4

- Agyemang, A. O., Yusheng, K., Twum, A. K., Edziah, B. K., & Ayamba, E. C. (2023b). Environmental accounting and performance: Empirical evidence from China. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02853-y

- Alatawi, I. A., Ntim, C. G., Zras, A., & Elmagrhi, M. H. (2023). CSR, financial and non-financial performance in the tourism sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 89, 102734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102734

- Alsahali, K. F., & Malagueño, R. (2022). An empirical study of sustainability reporting assurance: current trends and new insights. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 18(5), 617–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-05-2020-0060

- Amoah, P., & Eweje, G. (2020). CSR in Ghana’s gold-mining sector: Assessing expectations and perceptions of performance with institutional and stakeholder lenses. Social Business, 10(4), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1362/204440820X15929907056661

- Amoako, K. O., Amoako, I. O., Tuffour, J., & Marfo, E. O. (2022). Formal and informal sustainability reporting: An insight from a mining company’s subsidiary in Ghana. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 20(5), 897–925. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-12-2020-0368

- Anaman, P. D., Dzakah, G. A., Anyass, I., Ahmed, O. N., & Somiah-Quaw, F. (n.d.). Understanding Ghanaian banks’ views on the influence of ESG Reporting on their financial performance.

- Annan, B. A. (2023). Environmental social governance; The new age of corporate governance in Ghana. The New Age of Corporate Governance in Ghana (May 4, 2023). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4438349

- Appiah-Konadu, P., Apetorgbor, V. K., & Atanya, O. (2022). Non-financial reporting regulation and the state of sustainability disclosure among banks in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A literature review on banks in Ghana and Nigeria. Management and Leadership for a Sustainable Africa, Volume 2: Roles, Responsibilities, and Prospects, 2, 55–72.

- Arthur, C. L., Wu, J., Yago, M., & Zhang, J. (2017). Investigating performance indicators disclosure in sustainability reports of large mining companies in Ghana. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(4), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-05-2016-0124

- Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., Gelabert, L., & Gomez‐Mejia, L. R. (2013). Necessity as the mother of ‘green’inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strategic Management Journal, 34(8), 891–909. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2041

- Cadez, S., & Czerny, A. (2016). Climate change mitigation strategies in carbon-intensive firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 4132–4143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.099

- Cadez, S., Czerny, A., & Letmathe, P. (2019). Stakeholder pressures and corporate climate change mitigation strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2070

- Cadez, S., & Guilding, C. (2017). Examining distinct carbon cost structures and climate change abatement strategies in CO2 polluting firms. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 30(5), 1041–1064. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2015-2009

- Chege, S. M., & Wang, D. (2020). The influence of technology innovation on SME performance through environmental sustainability practices in Kenya. Technology in Society, 60, 101210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101210

- Chithambo, L., Tauringana, V., Tingbani, I., & Achiro, L. (2022). Stakeholder pressure and greenhouses gas voluntary disclosures. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(1), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101210

- Chu, Z., Wang, L., & Lai, F. (2019). Customer pressure and green innovations at third party logistics providers in China: The moderation effect of organizational culture. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 30(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2017-0294

- Cicchiello, A. F., Marrazza, F., & Perdichizzi, S. (2023). Non‐financial disclosure regulation and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: The case of EU and US firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(3), 1121–1128. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2408

- Dhanda, K. K., Sarkis, J., & Dhavale, D. G. (2022). Institutional and stakeholder effects on carbon mitigation strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 782–795. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2917

- Dissanayake, D., Tilt, C., & Qian, W. (2019). Factors influencing sustainability reporting by Sri Lankan companies. Pacific Accounting Review, 31(1), 84–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-10-2017-0085

- Eryadi, V. U., Wahyudi, I., & Jumaili, S. (2021 Pengaruh Kepemilikan Institusional, Kepemilikan Mayoritas, Kepemilikan Pemerintah, dan Profitabilitas Terhadap Sustainability Reporting Assurance. Conference on Economic and Business Innovation (CEBI),

- Esfahbodi, A., Zhang, Y., Watson, G., & Zhang, T. (2017). Governance pressures and performance outcomes of sustainable supply chain management–An empirical analysis of UK manufacturing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 155, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.098

- Esposito De Falco, S., Scandurra, G., & Thomas, A. (2021). How stakeholders affect the pursuit of the Environmental, Social, and Governance. Evidence from innovative small and medium enterprises. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(5), 1528–1539. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2183

- Famiyeh, S., Opoku, R. A., Kwarteng, A., & Asante-Darko, D. (2021). Driving forces of sustainability in the mining industry: Evidence from a developing country. Resources Policy, 70, 101910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101910

- Faseyi, C. A., Miyittah, M. K., & Yafetto, L. (2023). Assessment of environmental degradation in two coastal communities of Ghana using Driver Pressure State Impact Response (DPSIR) framework. Journal of Environmental Management, 342, 118224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118224

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., & Ruiz, S. (2014). Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1748-5

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage Publications.

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder perspective Boston: Piman. Harper and Row.

- Freudenreich, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Schaltegger, S. (2020). A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04112-z

- Gong, M., Gao, Y., Koh, L., Sutcliffe, C., & Cullen, J. (2019). The role of customer awareness in promoting firm sustainability and sustainable supply chain management. International Journal of Production Economics, 217, 88–96.

- Hair, J. F. Jr, (2020). Next-generation prediction metrics for composite-based PLS-SEM. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2020-0505

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., & Babin, B. J. (2010). RE Anderson Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Herold, D. M. (2018). Demystifying the link between institutional theory and stakeholder theory in sustainability reporting. Economics, Management and Sustainability, 3(2), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.14254/jems.2018.3-2.1

- Higgins, C., Tang, S., & Stubbs, W. (2020). On managing hypocrisy: The transparency of sustainability reports. Journal of Business Research, 114, 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.041

- Imperiale, F., Pizzi, S., & Lippolis, S. (2023). Sustainability reporting and ESG performance in the utilities sector. Utilities Policy, 80, 101468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2022.101468

- Jahid, M. A., Yaya, R., Pratolo, S., & Pribadi, F. (2023). Institutional factors and CSR reporting in a developing country: Evidence from the neo-institutional perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2184227. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2184227

- Jayaraman, K., Jayashree, S., & Dorasamy, M. (2023). The effects of green innovations in organizations: Influence of stakeholders. Sustainability, 15(2), 1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021133

- Kammerer, D. (2009). The effects of customer benefit and regulation on environmental product innovation.: Empirical evidence from appliance manufacturers in Germany. Ecological Economics, 68(8-9), 2285–2295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.02.016

- Kaur, R. (2021). Impact of financial distress, CEO power and compensation on environment, social and governance (ESG) performance: Evidence-based on UK firms.

- Kılıç, M., Uyar, A., Kuzey, C., & Karaman, A. S. (2021). Does institutional theory explain integrated reporting adoption of Fortune 500 companies? Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 22(1), 114–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-04-2020-0068

- Krasodomska, J., & Zarzycka, E. (2021). Key performance indicators disclosure in the context of the EU directive: When does stakeholder pressure matter? Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(7), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-05-2020-0876

- Lee, J. W., Kim, Y. M., & Kim, Y. E. (2018). Antecedents of adopting corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3024-y

- Lestari, E., Dania, W., Indriani, C., & Firdausyi, I. (2021). The impact of customer pressure and the environmental regulation on green innovation performance. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 733(1), 012048. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/733/1/012048

- Li, D., Huang, M., Ren, S., Chen, X., & Ning, L. (2018). Environmental legitimacy, green innovation, and corporate carbon disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(4), 1089–1104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3187-6