Abstract

This study initiates an investigation into an underexplored topic, aiming to understand the mechanism of conceptual elements of flow experience theory: enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals drive the tourist’s length of stay (LOS). To enhance understanding, this study investigates the impact of destination value and destination love as additional outcomes of flow experience and examines how these variables contribute to the relationship between flow experience and LOS. The data in this study was collected from domestic and worldwide tourists visiting various tourist destinations in Indonesia using an English-language online questionnaire. A variance-based structural equation model (PLS-SEM) is used to evaluate each set of relationships between variables. The present study identifies that enjoyment, control, attention, and clear goals significantly influence the length of tourist stays through the experience of flow. Additionally, the experience of flow generates both value and a meaningful love with the destination. Moreover, destination love stems from destination value, further contributing to the relationship between flow experience and LOS. This exploratory study constructs a comprehensive model, offering a valuable resource for destination managers aiming to increase LOS and optimize benefits from tourist arrivals.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Tourism is a highly valuable industry, contributing significantly to the growth of numerous other sectors. While attracting more tourists is crucial, encouraging them to extend their stay is equally important. This can be achieved by ensuring that tourists enjoy their visit, remain focused, feel in control, and have clear objectives. These factors collectively contribute to creating a ‘flow experience’—a state of deep immersion and enjoyment—for tourists. When tourists experience this state of flow, they tend to value the destination more highly and may even develop a deep affection for it. Consequently, they are more likely to prolong their stay, benefiting both the destination and its associated sectors. Therefore, it is essential for managers of tourist destinations to develop strategies that foster enjoyment, focus, control, and clear goals for tourists.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

In May 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially terminated the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) status, signaling a renewed optimism within the tourism industry for post-COVID-19 pandemic recovery (Gössling et al., Citation2021; Pan et al., Citation2021). The tourism literature urgently demands an understanding of current tourist behavior to get back to the competition (E. Lee et al., Citation2023). The urgency not only for volume of visitors, but also on the duration of their journey in destination, commonly referred to as the length of stay (LOS) (Aguilar & Díaz, Citation2019; Boto-García et al., Citation2019; Gozgor et al., Citation2021; Jackman et al., Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2020). Substantiated by prior research, a positive correlation exists between LOS and tourism revenue, attributed to heightened daily expenditures by longer-staying tourists (Aguilar & Díaz, Citation2019; Aguiló et al., Citation2017). Tourists with a longer LOS exhibit a propensity to engage with a larger quantity of tourist attractions, explore a broader range of regions, and contribute to a wider spectrum of economic value, diverse social interactions, and environmental benefits (Barros & Machado, Citation2010). It is possible that a rise in the number of visitors will not be followed by an increase in revenue from tourism because tourists are staying for a shorter time (Wang et al., Citation2012). Therefore, from a business perspective, focusing on LOS means concentrating on ways to optimize the monetization of tourist arrivals.

The multifaceted determinants of LOS have been a subject of meticulous investigation. Extant literature underscores gender-related distinctions, with women exhibiting a predilection for more protracted stay durations than their male counterparts (Santos et al., Citation2015). Recent findings by Gemar et al., (Citation2022) have discovered noticeable differences in LOS between international and domestic tourists. Professionals who travel for specific purposes tend to have shorter LOS compared to those who engage in leisure activities like sun and beach vacations or sports-related trips (Aguilar & Díaz, Citation2019). Alén et al., (Citation2014) further explicate a robust correlation between age and the decision to travel alone or with a group, exerting a discernible influence on LOS. An array of additional predictors has been investigated, encompassing factors such as distance, geography, culture, climate, nationality, income, destination familiarity, and annual travel plans (Gokovali et al., Citation2007). Despite extensive investigation into the multifaceted determinants of LOS, a notable gap persists in understanding the role of flow experience and its constituent elements. This study aims to address this gap by delving into the mechanisms of flow experience theory, specifically exploring enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals as drivers of tourist LOS. Furthermore, we enrich this exploration by investigating how destination value and love, as consequences of flow experience, contribute to the relationship between flow experience and LOS.

Acknowledging tourism as a facet of experiential consumption (Lin & Kuo, Citation2016), a destination’s value crystallizes as a synthesis of diverse and immersive experience during tourists’ visits. The rationale behind prolonging one’s stay at a specific destination often hinges on the quality of the experience. The flow experience concept, frequently employed to elucidate optimal individual experiences (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014; Lee & Payne, Citation2016; Peifer & Tan, Citation2021), becomes a pertinent theoretical framework, necessitating an unequivocal imperative to examine how its conceptual constructs explicate tourist experience and the phenomenon of LOS. This phenomenon is observed in a variety of contexts, ranging from social media and internet browsing to workplaces and tourism-related pursuits (deMatos et al., Citation2021; Kazancoglu & Demir, Citation2021; Leung, Citation2020; Peifer & Tan, Citation2021; Yen & Lin, Citation2020; Yuan et al., Citation2021). When doing an activity, being in the "flow" is thought to be the best way to enjoy it. It is reasonable and important to provide a new model that uses the theory of flow experience to explain the typical LOS of tourists at a destination. Examining the elements of flow such as enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goal helps enrich the discussion on this issue.

The investigation was carried out in Indonesia, which was chosen as the study site owing to its reputation as a nation with a plethora of well-known tourist attractions, such as Bali, Lombok, Labuhan Bajo, and Yogyakarta. Indonesia’s natural wonders earned it a prestigious spot among Lonely Planet’s top 10 countries to visit in 2019. Furthermore, it secured a remarkable accolade at the World Leisure Awards in Beijing 2023, where it was crowned The Best Island Destination. This recognition underscores Indonesia’s diverse appeal, catering to tourists with varying durations of stay, further enhancing its global standing as an exceptional travel destination. Indonesia is also known as the home of best cuisines in the world. Some culinary delights from Indonesia are recognized as the best food in the world, such as Rendang (an Indonesian meat dish which originated among the Minangkabau people in West Sumatra), Fried Rice, Satay, and gado-gado (an Indonesian version of a mixed salad). One of the rural in Indonesia, Pariangan Village was also named the most beautiful rural in the world. This recognition accentuates the multifaceted appeal of Indonesia, adept at accommodating tourists with diverse experiences and durations of stay, thereby further solidifying Indonesia’s position as an ideal research setting for understanding LOS. The investigation considers enjoyment as the first antecedent, given that previous studies suggest that individuals may experience a state of flow when they perceive the activity they are participating in to be enjoyable (Yang et al., Citation2014). In order to experience flow, an individual must perceive a match between their abilities in a given activity and the challenges presented (Montoro & Gil, Citation2019). The aforementioned condition can be interpreted as a state in which an individual’s complete control over their activities (C.-H. Lee & Wu, Citation2017), thus rendering "perceive full of control" as the second antecedent tested in this study. Subsequently, this study examines the role of focus and clear goals as the third and fourth antecedents. This study additionally investigates the moderating effect of destination love on the relationship between flow experience and LOS, as well as destination value as a contextual factor’s driver.

Literature review

The Length of stay (LOS)

The length of stay of tourists (LOS) is a crucial variable in tourism demand (Santos et al., Citation2015). LOS refers to the duration of time that a tourist spends at a particular destination. The term "length of stay" is often conflated with "travel duration", but scholars assert that these constructs are distinct (Santos et al., Citation2015). To avoid confusion, earlier research identified a logical reason for why these two things are distinct from one another. Travel duration pertains to the duration of the interval between the point of departure from and the point of arrival at the domicile. In contrast to the idea of LOS, which only applies to one destination, the travel duration might include stops at multiple destinations within a single journey. Getting longer journeys may not always result in longer stays at each destination. This could occur if there is a positive correlation between the duration of travel and the number of destinations visited. Drawing from this line of reasoning, in order to attain the highest possible benefits, focusing on LOS is the best option in the strategic blueprinting of destinations (Martínez-Garcia & Raya, Citation2008).

People engage in travel for a variety of reasons, and ultimately, the degree to which they have fulfilling experiences and achieve complete contentment plays an essential part in shaping their tourist tendencies (Bayih & Singh, Citation2020) including how long they stay at each destination. This is driven by the capacity of tourist destinations to conform to the interests, objectives, and requirements of visitors. Several factors that contribute to an optimal experience have the tendency to greatly impact individuals’ desire to lengthen their stay in a particular destination.

Theory of flow experience

The concept of flow experience, initially proposed by Csikszentmihalyi in 1990, has attracted considerable scholarly and practical interest as a positive psychology framework for comprehending optimal experiences (Jackson, Citation1996). Extensive scholarly inquiry has been undertaken to explore the phenomenon of flow experience across diverse domains and contexts, spanning from the field of psychology to recreational pursuits (Coble et al., Citation2003; Havitz & Mannell, Citation2005; Kleiber, Citation2012; Lee & Payne, Citation2016). Furthermore, this luxurious concept has been extensively examined in various prominent fields and disciplines, including the domains of art production and reception (Aykol et al., Citation2017; Freer, Citation2009), as well as betting (Trivedi & Teichert, Citation2017), playing (Buil et al., Citation2018), and the dynamic of social media and digital or virtual engagements (Barnes & Pressey, Citation2016; Cheon, Citation2013). The examination and implementation of the flow experience concept facilitates comprehension of the necessary mechanisms involved in diverse activities and environments (Aboubaker Ettis, Citation2017; Kühn & Petzer, Citation2018; Mao et al., Citation2016; Ozkara et al., Citation2016; Pelet et al., Citation2017). Numerous studies have demonstrated that the state of flow is an essential component in shaping an individual’s conduct during their activities and investigating their experiences in both digital and physical domains (Hernandez & Vicdan, Citation2014; Tasci & Milman, Citation2019). The presence of flow experience has also been looked into numerous times for the reason to understand the mechanisms that enable individuals to have best travel experiences (Abuhamdeh, Citation2020; Filep & Laing, Citation2019; Vada et al., Citation2020).

The concept of flow experience pertains to a state in which an individual experiences great enjoyment and complete immersion in an activity, leading to a perception that time has elapsed rapidly (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014). This phenomenon is often regarded as the pinnacle of experiential engagement (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2009a) and has the potential to elicit an intention to continue undertaking activities (Zhao & Khan, Citation2021). The state of flow can be induced through a confluence of intrinsic and extrinsic elements that collectively shape an individual’s subjective experience of the activity as pleasurable (Yeh, Citation2021). Individuals can reach a state of flow during travel when they perceive the ongoing experience as enjoyable, possess clear objectives, and focus on travel-related activities (Kang & Hyun, Citation2012). In addition, a factor that can contribute to this individual’s rewarding experience is the alignment between the challenges encountered during their travels and their personal capabilities (Moneta & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1996).

Enjoyment refers to the extent to which an activity can be savored in its own right, regardless of the potential consequences that may arise (Davis et al., Citation1992). Individuals who interact in engaging activities are likely to enjoy and be totally immersed in these activities, which leads to a flow experience (Yang et al., Citation2014). This naturally stimulates the urge to participate in the activity for a longer period of time. In the context of this study, the enjoyment represents the extent to which tourists enjoy their tourism activities, where the greater the pleasure generated from their activities, the greater the chance they are to have a positive flow experience and LOS. An individual possesses a subjective inclination and exerts deliberate efforts for continued participation in an activity that is perceived as enjoyable (Ghazali et al., Citation2019; Jang & Park, Citation2019). Tourists who enjoy themselves while visiting a particular destination are more likely to have the desire to, and even make an attempt to, stay for a longer period of time.

H1: Enjoyment has a positive effect on LOS mediated by flow experience

Individuals who are in a state of flow when participating in an activity tend to claim that time is passing more quickly than it actually is. This highlights the relevance of allocating more time to the activity. When tourists reach such a state, they tend to continue longer, potentially exceeding the duration outlined in their original itinerary. It is rational for tourists to be so deeply entwined with the moments they find that they strive to create a wider space and spend longer time there. The condition may arise when an individual directs their attention (focus) towards the activities they are engaged in Csikszentmihalyi, (Citation2009b). Concentration is explained as the state of individual attention and involvement directed towards the task or activity at hand (Koufaris, Citation2002). This study explores the degree to which tourists prioritize staying involved with the tours, actively avoiding any distractions that may divert their attention away from their tourism-related activities. When tourists are in the zone, they do not think about anything else and can just enjoy the moment (Yang & Holzer, Citation2006). The current research generates the idea that tourists who are empowered focus to fully immerse themselves in the activities available to them while on trip are more likely to have a rewarded positive experience that encourages them to stay longer their time there. In other words, the following is the next hypothesis of this investigation:

H2: Focus has a positive effect on LOS mediated by flow experience

H3: Clear goals has a positive effect on LOS mediated by flow experience

H4: Perceived control has a positive effect on LOS mediated by flow experience

Perceived destination value

Individuals generate cognitive and affective perception when exposed to environmental stimuli (Yang et al., Citation2021), whether this perception contributes to the value assumption or not. The aforementioned idea is commonly employed in products and services to measure users’ perceptions of consumption (Elshaer & Huang, Citation2023; Garrouch & Ghali, Citation2023; Uzir et al., Citation2021; Yuen et al., Citation2023). Peoples engage in an elaborate assessment of product utility, taking into consideration every relevant benefits and factors of concessions (Kim et al., Citation2007). Zeithaml (Citation1988) revealed that perceived value is how consumers feel about a product or service. Perceived value can be constructed as a comparison of the benefits to the costs, encompassing a comprehensive evaluation of the reciprocal transactional dynamics between the resources expended and the outcomes obtained (Zhang et al., Citation2017). In destination context, it refers to the total subjective tourist appraisal of what was given and what was received at the destination, stated as a ratio of the two. Using the consumer behavior approach, Li et al. (Citation2021) illustrate the varying forms of perceived value that arise from interactions between customers and service or product providers. Consumption experience shapes tourists’ perceptions of a destination’s value (Junaid et al., Citation2020). This mechanism can be noticed within the tourism field, where the interactions between tourists and destinations contribute to the set-up of a specific interaction experience in a destination that shapes the multi-levels of perceived value of a particular destination. An individual is likely to feel a sense of value when encountering a positive event or situation (Chen & Chen, Citation2010; Elshaer & Huang, Citation2023; Yen et al., Citation2022). The phenomenon of flow experience, as experienced by tourists, consists of overwhelmingly positive emotions, which subsequently contribute to their perception of a destination as possessing significant value. According to the set elaboration, the hypothesis is structured as follows:

H5: Perceived value is enhanced by flow experience.

Destination love

In the vast realm of consumerism, the idea of brand love holds significant recognition. This concept refers to the extremely deep levels of emotional attachment that a fulfilled consumer forms with a specific trade entity (Carroll & Ahuvia, Citation2006). It is deep and irreplaceable (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013). In the context of tourism, numerous tourists noted falling in love on particular destinations, relating their experiences that led to a deep emotional connection (Zhang et al., Citation2021). This may occur when tourists generate highly favorable emotions, a lot of excitement, strong attachment, and a great deal of passion for the destination as a result of tourist-destination interaction. Flow experience is a form of affective response that stimulates positive emotions and high involvement of tourists in tourism activities in a destination (Cheng & Lu, Citation2015) that can lead to a love of the destination. Flow experiences are considered a form of "rewarding experience" that can generate emotional attachment to a destination, which is a key element of destination love.

H6: Destination Love is enhanced by flow experience.

Perception of value offers an exciting opportunity for establishing connections with customers, fostering positive relationships (Kandampully et al., Citation2015), and obtaining desired emotional closeness (Brodie et al., Citation2013; Yuen et al., Citation2023). Touni et al. (Citation2022) explains that perceived value not only makes the provider-user connection positive, but furthermore also contains commitment, and intimacy in the relationship between the two. Therefore, when tourists perceive a destination as offering value, it leads to tourist-destination positive connection, cognitive and affective commitment, intimacy which leads to a strong emotional attachment to the destination.

H7: Perceived value has positive effect on destination love

When tourists fall in love with a destination, they are stimulated to actively engage with destination-based activities (Bergkvist & Bech-Larsen, 2010), willingness to pay additional costs (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013), and keep them from considering other options that allowing them to stay longer at the destination than those who do not. The feeling of love engenders a heightened resistance among customers towards any factors that impede or restrict their consumption activities (Batra et al., Citation2012). A love for a particular destination has the potential to transcend boundaries. For instance, those who embark on travels primarily to occupy their leisure hours might allocate their time to the journey out of love. Furthermore, the financial flexibility of a pre-planned excursion may exhibit a significant degree of elasticity. This mechanism leads to the following hypothesis

H8: Destination love has moderating effect on relationship between flow experience and LOS

Research design and methodology

Measurement and sampling

This study was conducted on worldwide tourists visiting various destinations in Indonesia at one point in time (cross section). A closed research questionnaire was used by adopting instrument items from previous established research. Enjoyment was measured using 4 items which were adopted from (Hsu & Chiu, Citation2004), perceived control and goal clarity each use 4 items of Guo and Poole, (Citation2009). Meanwhile, focus is measured by adopting 5 items from (Koufaris, Citation2002). The flow experience measurement uses 4 items adopted from (Kim et al., Citation2019) which are adapted to the destination context. LOS is quantified as the total number of nights that the tourist spends at a particular destination (Gokovali et al., Citation2007). Meanwhile, destination love and perceived value are measured using 8 and 5 items, respectively (Yen et al., Citation2022). The data was collected using an online questionnaire applying a Google Form. Respondents were identified using a convenience sampling technique with the help of tourism and hospitality department internship students in several regions around Indonesia, as well as collaboration with the researcher’s connections as enumerators.

Each enumerator was equipped with fundamental knowledge of the questionnaire, which encompassed instructions for completing the questionnaire and comprehension of each measurement item. Despite employing well-instructed enumerators, there remains a possibility that the data may not be completely proper. As a cross-checking technique, there is a reverse question. A preliminary study was conducted before the primary investigation began to check the accuracy of the instruments and the efficiency of the data acquisition techniques. Adjustments were made based on the findings of the preliminary project, and data acquisition continued. Through the initial phase of screening, we were able to acquire 319 valid sets of data for subsequent analysis. This study utilizes a set of variance-based Structural Equation Model (SEM) tests, a methodology frequently employed in behavioral research, specifically for evaluating aspects such as tourist satisfaction, travel experience, destination marketing, and similar constructs (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2022; Rodrigues et al., Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2021).

Measurement validation

An initial screening process was conducted, which led to the elimination of 11 data points due to their inconsistency with the reverse question. As a result, a total of 319 data points remained, which were deemed suitable for the next step of analysis. Subsequently, the outer model was subjected to a rigorous evaluation in order to assess the data quality and effectiveness of the instruments employed in this study, employing a maximum of 300 iterations (see ). With the exception of the first point item on perceived value, which obtained a loading factor value of 0.696, all other measurement items achieved loading factor values above 0.7. The undervalue score did not meet a significant level of concern, so it was determined to retain the item for inclusion in the subsequent test. The findings from the outer model test reveal that the Cronbach’s Alpha values exceed 0.7 and the composite reliability exceeds 0.8, suggesting that the items employed to assess each variable possess satisfactory levels of reliability (Hair et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). All constructs achieved an average variance extracted (AVE) value greater than 0.5 and a variance inflation factor (VIF) value lower than 0.3. The findings of this study suggest that the research data can be properly extracted and that there is no presence of multicollinearity. Another noteworthy finding in this study is that there is no observed social desirability bias. The SRMR score of 0.055 is below 0.1, indicating an appropriate model fit (Henseler et al., Citation2014). The determinant analysis test (see ) demonstrates that the square roots of average variance extracted (AVE) values satisfy the predetermined requirement (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 1. Result of outer model analysis.

Table 2. Fornell and Larcker discriminant validity.

Result

Sample characteristic

shows the demographic characteristics of the study respondents with an accumulation of male respondents at 51.4 percent and female at 48.6 percent. The majority of respondents are in the age range of 50–59 years (21.3%), 40–49 years (20.1%), and over 60 years (18.2%) with the majority of educational background is college (56.1%). Respondents with working status are 53.6%, housewife 17.9%, student 15.4%, retired 36% and other 6%. The study also identified the respondents’ country of origin. A total of 10.03% of respondents were domestic travelers, Chinese and Indian travelers were 8.78% and 8.46%, Saudi Arabia and USA were 8.15% each, UK (7.84%), Philippines (7.52%), Singapore (6.90%), Timor Leste (5.96%), Germany (5.33%). Other respondents came from the Netherlands, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, France, Poland, Belarus, Spain, and Hong Kong with cumulative percentages below 5 percent.

Table 3. Characteristic of participants.

Structural model and hypothesis testing

Hypothesis testing is done with a bootstrapping approach by implementing 600 sub-samples. Determination of significance results on each variable relationship using P value and T-Statistic criteria. The results showed that enjoyment affects the LOS mediated by flow experience with (β = 0.115 P value = 0.000, T Statistic = 3.506), while the direct effect of enjoyment and LOS is not significant (P Value = 0.470). This means that flow experience fully mediates the relationship between enjoyment and LOS. The same result is also shown by control (β = 0.072, P value = 0.014, T Statistic = 2.453) and Focus (β = 0.082 P value = 0.004, T Statistic = 2.878) where the direct effect is not significant. Statistically flow experience mediates the relationship between clear goal and LOS (β = 0.074 P value = 0.015, T Statistic = 2.428). While the direct effect of clear goal on LOS also shows statistically significant results (β = 0.089 P value = 0.029, T Statistic = 2.192). These results indicate that flow experience partially mediates the effect of clear goals on LOS. In other words, H1-H4 are supported.

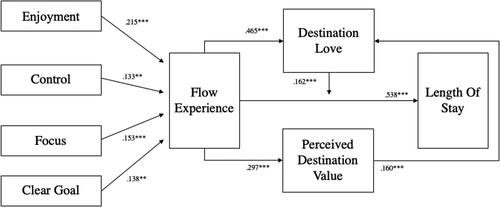

The results of the analysis show that flow experience has a positive effect on perceived value (β = 0.297 P value = 0.000, T Statistic = 5.094) and destination love (β = 0.465 P value = 0.00, T Statistic = 3.51), while perceived value also shows a significant positive effect on destination love which indicates H5, H6, H7 are supported. Testing the interaction effect was conducted to see the moderating role of destination love on the relationship between flow experience and LOS. Based on the test results, it shows a positive moderating effect (β = 0.162 P value = 0.002, T Statistic = 3.102) while the direct effect is statistically insignificant (P value = 0.086, T Statistic = 1.719). Based on these results, it can be concluded that destination love strengthens the positive influence of flow experience on LOS. and present the results of testing the structural model (direct, indirect, interaction effect).

Table 4. Structural model analysis.

Discussion

This study explains the mechanisms that shape tourist LOS using the flow experience theory approach, which still lacks understanding. Researchers have established the flow experience approach to explain how individuals can attain the highest level of experience (Barnes & Pressey, Citation2016; Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990; Kim & Thapa, Citation2018; Koufaris, Citation2002). The application of this approach to experiential-based consumption, such as tourism, gains significant relevance, particularly when understanding the complexities of LOS, considering it is closely tied to the overall experience at the destination.

LOS as a construct stands as a composite outcome shaped by numerous factors, demanding explicit elucidation of its multifaceted determinants. This study successfully establishes that enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals act as instrumental drivers of LOS through a flow experience. Enjoyment is a fundamental driver of tourist behavior (Peifer & Tan, Citation2021). When individuals find an activity enjoyable, they are more likely to engage in it for extended periods (Bilgihan et al., Citation2015). In the context of tourism, a positive and enjoyable experience can lead to a longer stay as tourists seek to prolong the pleasure at destination. The sense of control over one’s activities and experiences foster a feeling of autonomy. Tourists who perceive control are more likely to explore and engage with a destination at their own pace, contributing to a more immersive experience (Lunardo & Ponsignon, Citation2020). This autonomy, in turn, is associated with longer stays as individuals take their time to fully savor the destination. Concentration and focus on the experiences offered by a destination enhance the overall satisfaction of the visit (Kazancoglu & Demir, Citation2021). Tourists who are focused are more likely to delve into the diverse offerings of a destination. This heightened engagement correlates with an increased LOS as visitors aim to thoroughly explore the destination. Having clear goals provides tourists with a purpose for their visit (Havitz & Mannell, Citation2005). Whether it’s exploring specific landmarks, indulging in local cuisine, or participating in cultural activities, having defined objectives contributes to a more structured and meaningful experience. This purposeful engagement often results in a more extended stay to accomplish or fully enjoy these predefined goals. The flow experience encapsulates the synergy of enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014; Peifer & Tan, Citation2021). When tourists are in a state of flow, characterized by deep engagement and enjoyment, they are likely to lose track of time. This immersive experience acts as a mediator, intensifying the positive effects of enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals on LOS. Perceived value is a reflection of the benefits and satisfaction derived from the destination. The perception of value cultivates a profound emotional connection (Junaid et al., Citation2020), fostering a deep affection for the destination. A strong emotional bond, or "destination love", fosters a desire to prolong the connection, encouraging longer stays as tourists seek to deepen their emotional relationship with the destination.

Theoretical implication

This study significantly advances the tourism literature by serving as a foundational exploration into the determinants of tourist LOS. By explicating the influential roles of enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals, this research establishes a theoretical framework that contributes to a deeper understanding of how these factors collectively shape the duration of a tourist’s stay in a destination. Notably, the study reveals that the flow experience serves as a potent generator of destination values and fosters a profound emotional attachment, termed "destination love". Destination love emerges as a contextual factor influencing the strength of the relationship between flow experience and LOS, deriving from both destination value and the flow experience itself.

This nuanced exploration adds depth to our comprehension of the dynamic interaction between behaviors in tourism destinations, experience, perceived value, and emotional connections. This study’s theoretical framework not only expands our current understanding of tourist behavior but also establishes a foundation for future research endeavors. Furthermore, the study presents a replicable model that is based on the fundamental constructs of flow experience, destination values, and love. This model stands as a versatile tool, poised for validation and adaptation in diverse research settings, offering a robust foundation for scholars to build upon in their exploration of tourism dynamics.

Practical implication

The study’s findings offer practical and actionable insights for destination managers seeking to optimize tourist experiences and extend LOS. Recognizing the pivotal role of enjoyment, managers can curate engaging activities and events that align with the destination’s resource. By fostering a sense of autonomy, destinations can enhance infrastructure and provide tourists with the freedom to explore at their own pace. Concentration and focus, as highlighted by the flow experience theory, can be amplified through the creation of thematic attractions, guided tours, and interactive exhibits that captivate visitors. Clear goals can be met by designing purposeful itineraries, organizing themed festivals, and promoting unique cultural experiences. Destination managers can leverage these insights to develop targeted marketing campaigns, emphasizing the immersive and diverse aspects of the destination to attract a broader audience. In essence, by strategically integrating the principles of the flow experience theory, destination managers can craft compelling and memorable experiences, ultimately leading to longer stays and increased economic benefits for the destination.

Limitation and future research

The decision of many respondents to withhold information related to income or other financial conditions prevented this study from capturing a complete picture of their financial status, and the researcher’s duty is to respect that decision. The findings may primarily apply to the context of Indonesian tourists and destinations. Differences in destination types, associated motives, and cultures might result in varying outcomes. Therefore, researchers should exercise caution when generalizing the results to broader international tourism contexts. This study provides several recommendations for further research. First, researchers should replicate the framework proposed in this study to test its application to other areas in the tourism and hospitality sectors, such as guest hotels or other destinations with different respondent characteristics. Second, this study exclusively examines the mechanism for forming LOS using the perspective of the flow experience theory. However, the LOS is a complex decision. Future studies can also identify other factors that determine constructs using these different perspectives, including contexts that can strengthen or weaken relationships. Third, a longitudinal investigation on the topic of LOS needs to be considered.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study, conducted in the post-pandemic context after the revocation of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) status, provides a relevant and comprehensive understanding of tourist LOS. By applying the flow experience theory, the study elucidates the intricate determinants of LOS, highlighting the pivotal roles of enjoyment, control, focus, and clear goals. Enjoyment emerges as a fundamental driver, influencing tourists to extend their stay for the sake of prolonging the pleasurable experience at the destination. The sense of control fosters autonomy, contributing to immersive experiences and longer stays. Concentration, focus, and clear goals also play crucial roles, shaping a purposeful engagement that leads to extended durations of stay. The flow experience, characterized by deep engagement and enjoyment, acts as a mediator, intensifying the positive effects of these drivers on LOS. Additionally, perceived value cultivates a profound emotional connection, fostering destination love and further encouraging longer stays. This research not only advances our understanding of the factors influencing tourist behavior but also provides valuable insights for destination managers seeking to enhance visitor experiences and prolong their stays.

Disclosure statement

We have no conflicts of interest to declare. This research has not been submitted for publication nor has it been published in whole or in part elsewhere.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Fansurya, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alfi Husni Fansurya

Alfi Husni Fansurya as a junior lecturer in the Department of Tourism at the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality, Universitas Negeri Padang, Alfi Husni Fansurya is dedicated to exploring research topics encompassing tourist behavior, tourism marketing, destination management, and consumer behavior.

Perengki Susanto

Perengki Susanto is a Professor in Management Science at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business (FEB), Universitas Negeri Padang (UNP). His primary areas of interest in research include management science and practice. In addition to being a researcher, he currently serves as dean at FEB UNP Padang, Indonesia.

Youmil Abrian

Youmil Abrian serves as a senior lecturer within the Tourism Department at Universitas Negeri Padang in Indonesia. His primary research interests revolve around marketing and human resources management. He has contributed articles across diverse disciplines, delving into subjects such as consumer behavior, hotel management, and tourism.

Rahmi Fadilah

Rahmi Fadilah, a junior lecturer in the Department of Tourism at the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality, Universitas Negeri Padang, is enthuastic about research and community service associated with tourism communication, English literacy, and destination management for tourist attraction and tourism village.

Nidia Wulansari

Nidia Wulansari, a graduate with a Master’s degree in Management from Andalas University, currently teaches in the Hospitality Management program at Universitas Negeri Padang. Focused on research in the field of Marketing Management, she combines academic experience and industry practice to provide fresh insights into the world of hospitality marketing.

Yuke Permata Lisna

Yuke Permata Lisna, a lecturer in the Department of Tourism at the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality, Padang State University, possesses an academic background in hospitality management and event management through the completion of a master’s program. She is deeply enthusiastic about conducting research in areas such as event management, tourist behavior, tourism marketing, and destination management.

Arif Adrian

Arif Adrian serves as a senior lecturer within the Tourism Department at Universitas Negeri Padang in Indonesia. His primary research interests revolve around leadership and human resources management.

References

- Aboubaker Ettis, S. (2017). Examining the relationships between online store atmospheric color, flow experience and consumer behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.03.007

- Abuhamdeh, S. (2020). Investigating the “Flow” Experience: Key Conceptual and Operational Issues. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00158

- Aguilar, M. I., & Díaz, B. (2019). Length of stay of international tourists in Spain: A parametric survival analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102768

- Aguiló, E., Rosselló, J., & Vila, M. (2017). Length of stay and daily tourist expenditure: A joint analysis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 21, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.10.008

- Albert, N., &Merunka, D. (2013). The role of brand love in consumer‐brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(3), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761311328928

- Alén, E., Nicolau, J. L., Losada, N., & Domínguez, T. (2014). Determinant factors of senior tourists’ length of stay. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.002

- Aykol, B., Aksatan, M., & İpek, İ. (2017). Flow within theatrical consumption: The relevance of authenticity: Flow within theatrical consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1625

- Barnes, S. J., & Pressey, A. D. (2016). Cyber-mavens and online flow experiences: Evidence from virtual worlds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 111, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.07.025

- Barros, C. P., & Machado, L. P. (2010). The length of stay in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 692–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.12.005

- Batra, R.,Ahuvia, A., &Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand Love. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.09.0339

- Bayih, B. E., & Singh, A. (2020). Modeling domestic tourism: Motivations, satisfaction and tourist behavioral intentions. Heliyon, 6(9), e04839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04839

- Bilgihan, A., Nusair, K., Okumus, F., & Cobanoglu, C. (2015). Applying flow theory to booking experiences: An integrated model in an online service context. Information & Management, 52(6), 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2015.05.005

- Bonaiuto, M., Mao, Y., Roberts, S., Psalti, A., Ariccio, S., Ganucci Cancellieri, U., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2016). Optimal experience and personal growth: Flow and the consolidation of place identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1654. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01654

- Boto-García, D., Baños-Pino, J. F., & Álvarez, A. (2019). Determinants of tourists’ Length of stay: A hurdle count data approach. Journal of Travel Research, 58(6), 977–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518793041

- Brodie, R. J.,Ilic, Ana.,Juric, B., &Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.029

- Buil, I., Catalán, S., & Martínez, E. (2018). Exploring students’ flow experiences in business simulation games. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12237

- Carroll, B. A., &Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-006-4219-2

- Chen, C.-F., & Chen, F.-S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.008

- Cheng, T.-M., &Lu, C.-C. (2015). The Causal Relationships among Recreational Involvement, Flow Experience, and Well-being for Surfing Activities. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(sup1), 1486–1504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.999099

- Cheon, E. (2013). Energizing business transactions in virtual worlds: An empirical study of consumers’ purchasing behaviors. Information Technology and Management, 14(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-013-0169-6

- Coble, T. G., Selin, S. W., & Erickson, B. B. (2003). Hiking alone: Understanding fear, negotiation strategies and leisure experience. Journal of Leisure Research, 35(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2003-v35-i1-608

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (1st ed.). Harper & Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009a). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Nachdr.). Harper [and] Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009b). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Nachdr.). Harper [and] Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (2014). The dynamics of intrinsic motivation: A study of adolescents. In M. Csikszentmihalyi, Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 175–197). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_12

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(14), 1111–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x

- deMatos, N. M. d S., Sá, E. S. d., & Duarte, P. A. d O. (2021). A review and extension of the flow experience concept. Insights and directions for Tourism research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100802

- Elshaer, A., & Huang, R. (2023). Perceived value within an international hospitality learning environment: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 32, 100429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2023.100429

- Filep, S., & Laing, J. (2019). Trends and directions in tourism and positive psychology. Journal of Travel Research, 58(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518759227

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Freer, P. K. (2009). Boys’ descriptions of their experiences in choral music. Research Studies in Music Education, 31(2), 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X09344382

- Garrouch, K., & Ghali, Z. (2023). On linking the perceived values of mobile shopping apps, customer well-being, and customer citizenship behavior: Moderating role of customer intimacy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 74, 103396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103396

- Gemar, G., Sánchez-Teba, E. M., & Soler, I. P. (2022). Factors determining cultural city tourists’ length of stay. Cities, 130, 103938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103938

- Ghazali, E., Mutum, D. S., & Woon, M.-Y. (2019). Exploring player behavior and motivations to continue playing Pokémon GO. Information Technology & People, 32(3), 646–667. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-07-2017-0216

- Gokovali, U., Bahar, O., & Kozak, M. (2007). Determinants of length of stay: A practical use of survival analysis. Tourism Management, 28(3), 736–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.05.004

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gozgor, G., Seetaram, N., & Lau, C. K. M. (2021). Effect of global uncertainty on international arrivals by purpose of visits and length of stay. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(6), 1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2464

- Guo, Y. M., & Poole, M. S. (2009). Antecedents of flow in online shopping: A test of alternative models. Information Systems Journal, 19(4), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2007.00292.x

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne: SAGE.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Havitz, M. E., & Mannell, R. C. (2005). Enduring involvement, situational involvement, and flow in leisure and non-leisure activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 37(2), 152–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2005.11950048

- Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., Ketchen, D. J., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., & Calantone, R. J. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), 182–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526928

- Hernandez, M. D., & Vicdan, H. (2014). Rethinking flow: Qualitative insights from Mexican cross-border shopping. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 24(3), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2014.880937

- Hsu, M.-H., & Chiu, C.-M. (2004). Internet self-efficacy and electronic service acceptance. Decision Support Systems, 38(3), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2003.08.001

- Jackman, M., Lorde, T., Naitram, S., & Greenaway, T. (2020). Distance matters: The impact of physical and relative distance on pleasure tourists’ length of stay in Barbados. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102794

- Jackson, S. A. (1996). Toward a conceptual understanding of the flow experience in Elite Athletes. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 67(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1996.10607928

- Jang, Y., & Park, E. (2019). An adoption model for virtual reality games: The roles of presence and enjoyment. Telematics and Informatics, 42, 101239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101239

- Junaid, M., Hussain, K., Asghar, M. M., Javed, M., Hou, F., Liutiantian. (2020). An investigation of the diners’ brand love in the value co-creation process. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.08.008

- Kandampully, Jay.,Zhang, T., &Bilgihan, A. (2015). Customer loyalty: a review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 379–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2014-0151

- Kang, J., & Hyun, S. S. (2012). Effective communication styles for the customer-oriented service employee: Inducing dedicational behaviors in luxury restaurant patrons. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.014

- Kazancoglu, I., & Demir, B. (2021). Analysing flow experience on repurchase intention in e-retailing during COVID-19. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(11), 1571–1593. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2020-0429

- Kim, H.-W., Chan, H. C., & Gupta, S. (2007). Value-based adoption of mobile internet: An empirical investigation. Decision Support Systems, 43(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2005.05.009

- Kim, M. J., Bonn, M., Lee, C.-K., & Kim, J. S. (2019). Effects of employees’ personality and attachment on job flow experience relevant to organizational commitment and consumer-oriented behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 41, 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.09.010

- Kim, M., & Thapa, B. (2018). Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.08.002

- Kleiber, D. A. (2012). Optimizing leisure experience after 40. Arbor, 188(754), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2012.754n2007

- Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.13.2.205.83

- Kühn, S. W., & Petzer, D. J. (2018). Fostering purchase intentions toward online retailer websites in an emerging market: An S-O-R perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2018.1463799

- Lee, C., & Payne, L. L. (2016). Experiencing flow in different types of serious leisure in later life. World Leisure Journal, 58(3), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2016.1143389

- Lee, C.-H., & Wu, J. J. (2017). Consumer online flow experience: The relationship between utilitarian and hedonic value, satisfaction and unplanned purchase. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(10), 2452–2467. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-11-2016-0500

- Lee, E., Chung, N., & Koo, C. (2023). Exploring touristic experiences on destination image modification. Tourism Management Perspectives, 47, 101114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2023.101114

- Leung, L. (2020). Exploring the relationship between smartphone activities, flow experience, and boredom in free time. Computers in Human Behavior, 103, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.030

- Li, M., Hua, Y., & Zhu, J. (2021). From interactivity to brand preference: The role of social comparison and perceived value in a virtual brand community. Sustainability, 13(2), 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020625

- Lin, C.-H., & Kuo, B. Z.-L. (2016). The behavioral consequences of tourist experience. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.12.017

- Lunardo, R., & Ponsignon, F. (2020). Achieving immersion in the tourism experience: The role of autonomy, temporal dissociation, and reactance. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1151–1167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519878509

- Mao, Y., Roberts, S., Pagliaro, S., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Bonaiuto, M. (2016). Optimal experience and optimal identity: A multinational study of the associations between flow and social identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 67. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00067

- Martínez-Garcia, E., & Raya, J. M. (2008). Length of stay for low-cost tourism. Tourism Management, 29(6), 1064–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.011

- Moneta, G. B., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. Journal of Personality, 64(2), 275–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00512.x

- Montoro, A. B., & Gil, F. (2019). Exploring flow in pre-service primary teachers doing measurement tasks. In M. S. Hannula, G. C. Leder, F. Morselli, M. Vollstedt, & Q. Zhang (Eds.), Affect and mathematics education (pp. 283–308). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13761-8_13

- Ozkara, B. Y., Ozmen, M., & Kim, J. W. (2016). Exploring the relationship between information satisfaction and flow in the context of consumers’ online search. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 844–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.038

- Pan, K.-Y., Kok, A. A. L., Eikelenboom, M., Horsfall, M., Jörg, F., Luteijn, R. A., Rhebergen, D., Oppen, P. v., Giltay, E. J., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2021). The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: A longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. The Lancet, 8(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30491-0

- Park, S., Woo, M., & Nicolau, J. L. (2020). Determinant factors of tourist expenses. Journal of Travel Research, 59(2), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519829257

- Peifer, C., & Tan, J. (2021). The psychophysiology of flow experience. In C. Peifer & S. Engeser (Eds.), Advances in flow research (pp. 191–230). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53468-4_8

- Pelet, J.-É., Ettis, S., & Cowart, K. (2017). Optimal experience of flow enhanced by telepresence: Evidence from social media use. Information & Management, 54(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.05.001

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Rather, R. A., & Hall, C. M. (2022). Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tourism Review, 77(2), 687–709. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2021-0086

- Rodrigues, Á., Loureiro, S. M. C., & Prayag, G. (2022). The wow effect and behavioral intentions of tourists to astrotourism experiences: Mediating effects of satisfaction. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(3), 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2507

- Sanjamsai, S., & Phukao, D. (2018). Flow experience in computer game playing among Thai university students. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 39(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2018.03.003

- Santos, G. E., de, O., Ramos, V., & Rey-Maquieira, J. (2015). Length of stay at multiple destinations of tourism Trips in Brazil. Journal of Travel Research, 54(6), 788–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514532370

- Tasci, A. D. A., & Milman, A. (2019). Exploring experiential consumption dimensions in the theme park context. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(7), 853–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1321623

- Touni, R.,Kim, W. G.,Haldorai, K., &Rady, A. (2022). Customer engagement and hotel booking intention: The mediating and moderating roles of customer-perceived value and brand reputation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 104, 103246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103246

- Trivedi, R. H., & Teichert, T. (2017). The janus-faced role of gambling flow in addiction issues. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(3), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0453

- Uzir, M. U. H., Al Halbusi, H., Thurasamy, R., Thiam Hock, R. L., Aljaberi, M. A., Hasan, N., & Hamid, M. (2021). The effects of service quality, perceived value and trust in home delivery service personnel on customer satisfaction: Evidence from a developing country. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102721

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., Scott, N., & Hsiao, A. (2020). Positive psychology and tourist well-being: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100631

- Wang, E., Little, B. B., & DelHomme-Little, B. A. (2012). Factors contributing to tourists’ length of stay in Dalian northeastern China – A survival model analysis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.03.005

- Yang, F., Tang, J., Men, J., & Zheng, X. (2021). Consumer perceived value and impulse buying behavior on mobile commerce: The moderating effect of social influence. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102683

- Yang, K., & Holzer, M. (2006). The Performance-Trust Link: Implications for Performance Measurement. Public Administration Review, 66(1), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00560.x

- Yang, S., Lu, Y., Wang, B., & Zhao, L. (2014). The benefits and dangers of flow experience in high school students’ internet usage: The role of parental support. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.039

- Yeh, S.-S. (2021). Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1805933

- Yen, C.-H., Tsai, C.-H., & Han, T.-C. (2022). Can tourist value cocreation behavior enhance tour leader love? The role of perceived value. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 53, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.10.001

- Yen, W.-C., & Lin, H.-H. (2020). Investigating the effect of flow experience on learning performance and entrepreneurial self-efficacy in a business simulation systems context. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(9), 1593–1608. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1734624

- Yuan, C., Wang, S., Yu, X., Kim, K. H., & Moon, H. (2021). The influence of flow experience in the augmented reality context on psychological ownership. International Journal of Advertising, 40(6), 922–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1869387

- Yuen, K. F., Chua, J. Y., Li, X., & Wang, X. (2023). The determinants of users’ intention to adopt telehealth: Health belief, perceived value and self-determination perspectives. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 103346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103346

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

- Zhang, M., Guo, L., Hu, M., & Liu, W. (2017). Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. International Journal of Information Management, 37(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.04.010

- Zhang, T., Yin, P., & Peng, Y. (2021). Effect of commercialization on tourists’ perceived authenticity and satisfaction in the cultural heritage tourism context: Case study of Langzhong Ancient City. Sustainability, 13(12), 6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126847

- Zhao, H., & Khan, A. (2021). The students’ flow experience with the continuous intention of using online english platforms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 807084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.807084

- Zhu, D. H., Chang, Y. P., Luo, J. J., & Li, X. (2014). Understanding the adoption of location-based recommendation agents among active users of social networking sites. Information Processing & Management, 50(5), 675–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2014.04.010