Abstract

This study examines the determinants of sunflower farmers’ intention to seek Agricultural Value Chain Financing (AVCF) in Tanzania. A cross-sectional survey design was used to collect data from 184 farmers in Singida and Dodoma. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was engaged to test the hypotheses. The findings revealed a significant link between perceived benefit, perceived risk, knowledge, social enterprise embeddedness, and farmers’ intention to seek AVCF. However, perceived behavioral control over AVCF and subjective norms demonstrated an insignificant relationship with farmers’ intention to seek AVCF. The results of the present study imply that stakeholders and providers of AVCF must create adequate farmers’ awareness in terms of perceived benefits and risks involved in AVCF. Moreover, the embeddedness of social enterprises in AVCF creates social implications among farmers, through supporting social missions and improving the lives of vulnerable farmers, hence leading to poverty eradication among defenseless farmers.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Agricultural Value Chain (AVC) ascertains the set of actors, such as public, private, and service providers, and activities that convey agricultural product from production field to final consumption, where at each stage, some value is added to the product (Middelberg, Citation2017; Rahman et al., Citation2022). This embraces production, processing, packaging, storage, distribution and transportation (Joshi et al., Citation2017). Based on this, Agricultural Value Chain Financing (AVCF) involves the flow of financial resources to and among the numerous associations within the AVC in terms of financial services and products, and support services that flow to or through value chains to alleviate and address constraints (Casuga et al., Citation2008; Chen et al., Citation2023; Miller & Jones, Citation2010). AVCF plays essential role in agricultural activities including provision of modern agricultural technology, promotion of specialization and sustainability of agricultural production through commercialization and transformation of agricultural sector (Oteh et al., Citation2024; Swamy & Dharani, Citation2016). It also develops and distributes equal economic and agricultural opportunities, reduces poverty and contributes in sustainable economic growth in various rural settings (Crawford, Cui, Kewley, Citation2023; Fearne et al., Citation2012; Maryam et al., Citation2023). In addition, application of AVCF encourages financial inclusion through expansion of innovative agricultural financing opportunities (Dagnew et al., Citation2024; Kopparthi & Kagabo, Citation2012), which in turn improves efficiency, repayments and coordination among participants (Madamombe et al., Citation2024; Villalba et al., Citation2023). Besides that, the efficiency, effectiveness and quality of agricultural chains is improved as the results of mitigation of agricultural risks through AVCF (Chen et al., Citation2015; Ho et al., Citation2023; Villalba et al., Citation2023; Zander, Citation2015).

Generally, effective implementation of AVCF improves the entire agri-food value chains hence leading to food security and improvements of rural communities’ wellbeing (Dagnew et al., Citation2024; Liu et al., Citation2023). Since agri-food value chains means various steps and activities considered while bringing agricultural products from production to final consumption area (Cannas, Citation2023; El Bhilat et al., Citation2024; Fearne et al., Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2023), consideration of AVCF in agri-food value chains and in the entire agricultural sector is invetable (Mausch et al., Citation2020; Oteh et al., Citation2024; Santos et al., Citation2024; Saruchera & Mpunzi, Citation2023). Therefore based on these arguments, AVCF contributes significantly in the growth and development of agricultural sector.

The agricultural sector is one of the important components of an economy in the country (Nyagango et al., Citation2023; Oberholster et al., Citation2015). Significant investments in a country’s agricultural sector contribute to food security, poverty reduction, and economic development (Dogeje, Citation2023; Isaga, Citation2018; Khan et al., Citation2022). This denotes that, intensive financing and investment in agricultural sector contributes in economic growth four times compared to other sectors, especially because of its multiplier effects in the economy (Bhatia et al., Citation2023; Chandio et al., Citation2017). Nkegbe (Citation2018) and Rugeiyamu et al. (Citation2023) put forward that improving agricultural productivity in developing countries improves subsistence farmers’ livelihoods. Emerging forces of globalization accompanied by climate change, food insecurity, and outbreaks of communicable diseases such COVID 19 call for improvement in the agricultural sector, especially in emerging and developing countries (Dong, Citation2023; Khan et al., Citation2022; Khan & Ponce, Citation2021; Liao et al., Citation2022; Madamombe et al., Citation2024; Miller & Jones, Citation2010; Tiet et al., Citation2022; von Horn & Kudic, Citation2023). A review of the agricultural sector in these countries shows that its sustainable growth is limited by inadequate financing and working capital, fluctuations in market prices, unreliable weather, and markets (Doran et al., Citation2009; Hananu et al., Citation2015; Wasan et al., Citation2023). Consequently, agricultural supply will be limited, leading to food insecurity among various nations (Khan et al., Citation2022; Khan & Ponce, Citation2021; Wanyonyi et al., Citation2023). All of these factors affect the productivity of subsistence farmers, including those dealing with sunflower farming.

Sunflower farming is the major agricultural-commercial crop being produced in the central agricultural corridors of Tanzania (Rugeiyamu et al., Citation2023). Such farming produces most valuable vegetable oils in Tanzania and in various worldwide markets, hence being recognised as the most essential product followed by rapeseed oils, palm and soybean (Isinika & Jeckoniah, Citation2021; Mohammed et al., Citation2018). Based on this, it has been considered by the Bank of Tanzania (BOT) as an agricultural-subsector which qualifies for applications of innovative agricultural financing such as AVCF in Tanzania (Kombe et al., Citation2017). Additionally, sunflower farming employs more than 50 percent of the local communities in the central agricultural regions of Tanzania, who are highly vulnerable to poverty (Mgeni et al., Citation2018). This implies that, improvement in sunflower farming through provision of AVCF will aid in improving households income, hence enhancing standard of living of rural and subsistence farmers.

Some ordinary evidence show that, most of the rural and subsistence farmers are extremely excluded in the financial systems of the formal lending (Maryam et al., Citation2023; Swamy & Dharani, Citation2016; Villalba et al., Citation2023). This is caused by the supply- and demand-side reasons. Demand-side reasons include poor credit track records of farmers, inability of farmers to develop viable project proposals, and low loan repayment (Kopparthi & Kagabo, Citation2012). On the other hand, high transaction cost and missing borrower’s information constitute to the supply side factors (Bhatia et al., Citation2023; Chen et al., Citation2023; Johnston & Meyer, Citation2008). These limitations lead to farmers’ marginalization from the financial system, which in turn forces them to borrow from informal lenders at high interest rates, while repayments are made based on their output (Chandio et al., Citation2017). This repayment is four times higher than that in the formal lending system. Consequently, poverty among subsistence farmers has continued to increase. Hu and Huang (Citation2018), Joshi et al., (Citation2017), Kopparthi and Kagabo (Citation2012), Rajiv and Jagongo (Citation2014), Magsilang et al. (Citation2023), Mukucha and Chari (Citation2021) and Yu and Rehman Khan (Citation2022) maintain that segregation of farmers from formal financing systems has accelerated the introduction of innovative financing strategies such as AVCF in most developing countries.

As in other developing countries, Tanzanian farmers are excluded from the formal financing system despite its economy’s dependency on agriculture (Maryam et al., Citation2023; Saqib et al., Citation2018; Villalba et al., Citation2023). Although the agricultural sector contributes 28 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), subsistence and commercial farmers in Tanzania continue to experience limited access to agricultural finance. Furthermore, although the sector also employs 80 percent of Tanzanians (Isaga, Citation2018; Nyagango et al., Citation2023), more than 43.8 percent of farmers in Tanzania continue to live below the poverty (Mgeni et al., Citation2018). Despite the significant role played by the agricultural sector in developing nations such as Tanzania, there is limited empirical evidence on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF (Kombe et al., Citation2017; Crawford, Cui, Kewley, Citation2023; Isaga, Citation2018; Kopparthi & Kagabo, Citation2012; Mgeni et al., Citation2018; Rugeiyamu et al., Citation2023; Swamy & Dharani, Citation2016). This is also based on the gap that past studies have paid much attention to socio-economic characteristics, but less attention to behavioral influences (Chandio et al., Citation2017; Dzadze et al., Citation2012; Isaga, Citation2018). This gap justifies the need for the present study to center on the determinants of farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF.

Most previous studies examined the effect of socioeconomic and demographic features on farmers’ access to bank credit (Chandio et al., Citation2017; Dzadze et al., Citation2012; Isaga, Citation2018; Nouman et al., Citation2013; Saqib et al., Citation2016). In doing so, they considered family income, farming experience, gender, size of landholdings, and age to be determinants of credit access. Moreover, these studies have paid much attention to traditional financing (commercial bank credit), ignoring innovative financing mechanisms such as AVCF. Contrary to previous studies, the current study considers the influence of behavioral factors, as advocated by the theory of planned behavior (TPB), on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. More precisely, such factors include subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control over AVCF. For the present study, farmers’ attitudes towards AVCF were represented by perceived risk and perceived benefit, as advocated by Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019), Albert and Ren (Citation2001), and Pitta et al. (Citation2008).

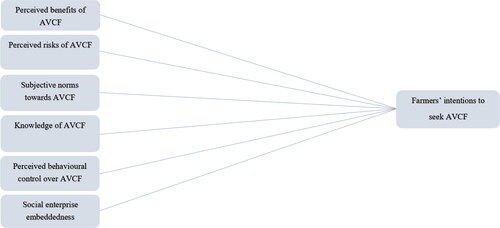

In addition to the elements of the TPB, this study introduced social enterprise embeddedness and knowledge of AVCF as additional determinants of AVCF intentions. The introduction of additional determinants is imperative because when TPB is employed in contexts not originally developed for, additional attributes must be involved (Fielding et al., Citation2008; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, incorporation of these variables in the study model has contributed in enhancing predictive capacity of the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014). More specifically, embracement of social mission and knowledge of AVCF is very important in understanding farmers’ awareness on various innovations in agriculture (Aisaiti et al., Citation2019; Cheng et al., Citation2020). This implies that, consideration of farmers’ knowledge related with AVCF plays a substantial role in understanding farmers’ awareness on their intentions to adopt sustainable agricultural innovations including AVCF. Also, for the promotion of entrepreneurial activities in agricultural sector, Peter et al. (Citation2024) and Wang et al. (Citation2015) insisted the necessity of understanding the role of social enterprises like providers of AVCF among farmers. Therefore, inclusion of social enterprises in our model bring a significant contribution in understanding the role of agricultural social enterprises in exploring farmers’ intentions to seek for AVCF in Tanzania.

Since the concept of AVCF is still a novel concept among farmers in various developing countries like Tanzania, our present study contributes significantly in explaining drivers of farmers intentions to adopt AVCF. Understanding empirical factors explaining farmers’ intentions to adopt AVCF is very significant in boosting sunflower farmers’ output and raising households’ income, hence improving standard of living among defenseless farmers. Furthermore, based on researchers’ understanding and knowledge, the current study is a recent study that considers TPB to explain the factors affecting farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania. This creates a new contribution to the literature on innovative agricultural financing, mainly AVCF, in the background of developing states, such as Tanzania. On top of that, consideration of social enterprise embeddedness and knowledge in our model offer empirical contributions to practitioners and academic communities. This implies that, practical and managerial contributions are provided among AVCF providers to design and implement AVCF products that embraces holistic agricultural and social enterprise among farmers. In doing so, provision of AVCF creates social implications among farmers, mainly through advancement of quality of living and outputs of vulnerable small-scale farmers. Based on these contributions, therefore, the objective of this study is to examine the determinants of farmers’ intention to seek AVCF in Tanzania.

The next section presents a thorough review of the literature in line with the current study, and the proposed hypotheses and methodology used to execute the study. This is followed by information on the data analysis and discussion of the findings in the third and fourth sections, respectively, and the conclusion, implications, recommendations, and gaps for further studies in the last sections.

Literature review

Guiding theory

Ajzen’s (Citation1991) theory of planned behavior (TPB) guides the current study in exploring farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. The TPB states that predictions of individuals’ intentions to undertake particular actions and behaviors are explained by perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitudes towards such behavior. According to Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019), attitude is used to examine an individual’s positive or negative assessment of a certain behavior. This, in turn, could predict the expected outcomes based on the designed perceptions. According to Ajzen (Citation1991), the strength of a user’s behavior is directly affected by their positive or negative attitudes towards such actions. Prior studies such as Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019), Albert and Ren (Citation2001), and Pitta et al. (Citation2008) have documented three (3) categories of attitudes: perceived benefits, affect, and risk. Therefore, based on the nature of this study, farmers’ attitudes towards AVCF are represented by perceived benefits and risks. Perceived risk towards AVCF has been used as an unfavorable attitude towards while perceived benefits are recognized as favorable attitudes towards AVCF (Gärling et al., Citation2009; Wickramasinghe & Gurugamage, Citation2012). Perceived affect was not considered in this study because of the immaturity of AVCF in developing countries such as Tanzania (Turvey & Kong, Citation2010).

Since TPB is an extension of the theory of reasoned action, it can explain the relationship between individual behavior and intentions (Ajzen, Citation1991). TPB has successfully demonstrated its suitability in various fields while determining and describing individuals’ behaviors’ (Aisaiti et al., Citation2019). This theory has been modified and applied by previous researchers to examine individuals’ intentions in numerous matters, such as purchasing behavior, microcredit applications, tax evasion, and adoption of mobile banking (Alleyne & Harris, Citation2017; Ammar & Ahmed, Citation2016; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014; Owusu et al., Citation2019; Citation2021).

Based on the above grounds, TPB has also been employed by researchers to examine farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania. To determine such intentions, variables such as AVCF knowledge and social enterprise embeddedness have been included, in addition to perceived behavioral control over AVCF, subjective norms and attitudes (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014; Pinto et al., Citation2000). The consideration of additional determinants is due to the fact that when TPB is employed in contexts not originally developed for, additional constructs must be involved (Fielding et al., Citation2008; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014). Such constructs have contributed in increasing predictive capacity of the TPB model (Ajzen, Citation1991; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014). It is also believed that AVCF can be evaluated positively or negatively. Therefore, it is logical to consider the effect of behavioral factors on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. Based on general understanding, the use of TPB to explain factors that drive farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania provides a suitable conceptual model for the current study.

Hypotheses development

Perceived benefits of AVCF

Customers evaluate the attributes of any product as either good or bad (Nguyen et al., Citation2023; Nshom et al., Citation2022; Ratcliffe et al., Citation2022). As part of cognitive attitudes, perceived benefits assist in evaluating the quality of products (Sarikhani & Ebrahimi, Citation2022; Sotiropoulos & d’Astous, Citation2013). Under the TBP, perceived benefits of any product are determined by attitudes of customers towards such product (Dorce et al., Citation2021; Loh & Hassan, Citation2022; Marwa & Manda, Citation2022; Owusu et al., Citation2021). As per TPB, product satisfaction, perceived value, and usefulness determine purchase intentions (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Bobkina & Domínguez Romero, Citation2022; Khare, Citation2023). Since perceived benefit deals with positive perception of various consumers related with their numerous decisions including financing decision, it has a power to explain farmers’ intentions to look for AVCF (Ajambo et al., Citation2023; Jiaping et al., Citation2017). This implies that, when farmers expect developments in their agricultural outputs, increase in families’ income and enhancement of quality of living, their decisions to seek for AVCF will be high. As per Koh et al. (Citation2018) these benefits could be either direct or indirect, since they depend on their means of attainments. In this regard, perceived usefulness, value, and satisfaction with AVCF influence farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. More precisely, in this study perceived benefits of AVCF to farmers include increase in family income, improvements in living standard of the family and increase in farmer’s productivity (Dagnew et al., Citation2024; Kopparthi & Kagabo, Citation2012; Lee et al., Citation2022; Mishi & Kapingura, Citation2012; Villalba et al., Citation2023). Such perceived benefits encourage farmers to seek AVCF. Therefore, based on these, it is logical to state that:

H1: Farmer’s perceived benefits of AVCF positively influence their intentions to seek AVCF.

Perceived risks of AVCF

Undertaking any financial decision including having intentions to seek for AVCF creates perceived risk among farmers (Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2015). In our study, perceived risk being part of attitude under the TPB, it involves farmers’ conception that AVCF possess possible negative outcomes related with availability and accessibility of AVCF. Since AVCF is still a novel concept among farmers in developing countries, its consideration among rural farmers is limited due to various risks. Based on this, the provision of AVCF is also accompanied by its shortcomings; therefore, farmers’ perceptions of the risks and deterrents of AVCF affect their intentions to seek AVCF (Abbas et al., Citation2022; Nshom et al., Citation2022). This informs that, existence of perceived reduce farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. Previous studies, such as Jebarajakirthy et al. (Citation2014), Li et al. (Citation2011), Oberholster et al. (Citation2015) and Turvey and Kong (Citation2010) indicate that the need for collateral, high interest rates, and long delays impair farmers’ intentions to seek agricultural credit. In addition, farmers’ inability to repay the loan and unpredicted weather, especially rainfall, discourages them from seeking AVCF (Choudhury et al., Citation2022; Kyire et al., Citation2023). According to Cantillo and Van Caillie (Citation2023), a combination of these risk factors creates perceived risk among farmers related to various intentions, including AVCF. Hence, these unpleasant perceptions lead to negative intentions to seek AVCF. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H2: Farmer’s perceived risks of AVCF negatively influence their intentions to seek AVCF.

Subjective norms towards AVCF

According to Ajzen (Citation1991) and Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1980), subjective norms are recognized as the ‘perceived social pressure not to execute or to execute a specific behaviour’. As per Chan et al. (Citation2022) and Tavakoly Sany et al. (Citation2023) it is one of the determinants of an individual’s behavior under the TPB. This implies that the involvement of a particular individual in certain matters is determined by his or her behavior (Amin, Citation2013; Jose & Sia, Citation2022; Waris et al., Citation2023). Some of the previous studies, such as Butler et al. (Citation2012), Neubaum et al. (Citation2023) and Van Tonder et al. (Citation2023) stated that subjective norms are among the determinants of customers’ intentions to purchase financial products. Generally, the perceptions of friends and family members affect farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. Based on this, the following conclusions were drawn:

H3: Subjective norms towards AVCF positively affect farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF.

Knowledge of AVCF

For the purpose of this study, knowledge of AVCF involves general knowledge and understanding of products under agricultural financing. As evidenced by De Kimpe et al. (Citation2022), Liao et al. (Citation2022), Roh et al. (Citation2022), and Rugeiyamu et al. (Citation2023) perceived knowledge and understanding predict the intention to be involved in various aspects, including farmers’ intentions to look for AVCF. Shim et al. (Citation2009) and Xiao et al. (Citation2011) conclude that customers’ knowledge and understanding of financial products influences their purchasing intentions. This is also in agreement with previous studies, such as Jafar et al. (Citation2023), Nautiyal and Lal (Citation2022), Roh et al. (Citation2022) and Zhou et al. (Citation2022). These studies conclude that perceived knowledge and purchasing intentions are positively and significantly related. In this case, farmers with adequate understanding and knowledge of AVCF increase their intention to seek AVCF. This leads to the following hypothesis.

H4: Knowledge of AVCF positively influences farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF

Perceived behavioural control over AVCF

As per Ajzen (Citation1991), perceived behavioral control entails observed difficulties or ease of undertaking such behavior. It influences individuals’ behavioral intentions towards a particular product (Acikgoz et al., Citation2023; Koay & Cheah, Citation2023). Purchasing or looking for a certain financial product is highly determined by a customer’s perceived behavioral control towards such a product (Baluku et al., Citation2023; Butler et al., Citation2012; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2014; Nogueira et al., Citation2023). For this case, past studies such as Amin (Citation2013), Isaga (Citation2018), and Villanueva-Flores et al. (Citation2023) have indicated that when farmers apply for agricultural credit, they should have the ability to repay their borrowings, including the interest charged. This leads to the subsequent hypothesis:

H5: Perceived behavioural control positively influences farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF.

Social enterprise embeddedness

Social enterprises involve the application of commercial activities to support social missions by various parties, including non-governmental organizations (Byerly, Citation2014; Mohiuddin, Citation2017; Sipahi Dongul & Artantaş, Citation2023). This means a business model that allows customers to share profits as members of that business. In other words, social enterprises help enhance the value of society through the integration of business sustainability and social welfare (Doherty et al., Citation2014; Villalba et al., Citation2023). According to Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019), social enterprises have gained academic interest in recent years. This is because of the newness of rural farmers and consumers. The main focus of social enterprises is to advance the quality of life of vulnerable groups such as small-scale farmers (Barraket et al., Citation2022; Sipahi Dongul & Artantaş, Citation2023). From this perspective, agricultural finance providers will not only provide financing to farmers, but also other related services to vulnerable farmers (Wang et al., Citation2015).

To strengthen farmers’ quality of life, the application of social enterprises by providing innovative agricultural financing to farmers assists in eradicating poverty (Aisaiti et al., Citation2019; Cheng et al., Citation2020; Peter et al., Citation2024). This leads to the embeddedness of various social issues, such as the promotion of business opportunities and motivation of farmers’ involvement in agricultural activities in rural areas (Korsgaard et al., Citation2022; Nowak & Raffaelli, Citation2022). Sipahi Dongul and Artantaş (Citation2023) pointed out that the embeddedness of social enterprises in the agricultural value chain system provides farmers with opportunities before, after, and during the production era. Considering the necessity of social enterprise embeddedness in the agricultural sector, it is logical to hypothesize the following:

H6: Social enterprise embeddedness in agricultural sector positively affects farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF.

Methodology

Study areas

This study was undertaken in the central agricultural regions of the United Republic of Tanzania (URT) in East Africa. Specifically, it occurred at Kibaigwa and Shelui in the Dodoma and Singida regions, respectively. The selection of these areas was accredited by the fact that they are rich in the production and sale of sunflowers compared to the rest of the region (Isinika & Jeckoniah, Citation2021; Mohammed et al., Citation2018; Njiku & Nyamsogoro, Citation2019; Rugeiyamu et al., Citation2023). Additionally, these areas reflect regions in which AVCF was originally introduced and practiced significantly (Mpeta, Citation2015). The data for the present study were obtained from sunflower farmers in these regions. Sunflower farmers were chosen based on their reputable experiences in practicing AVCF in Tanzania compared to other types of farmers (Mpeta, Citation2015). Also, they are recognised as the most essential producers of mostly priced vegetable oils in the country (Kombe et al., Citation2017; Rugeiyamu et al., Citation2023). This has highly attracted providers of AVCF in Tanzania to consider sunflower farming in their financing priorities. Based on this, it is noted that the farmers in this study were sunflower farmers. Therefore, consideration of sunflower farmers in our research setting provides a rich basis for exploring the factors explaining sunflower farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania.

Sampling and data collection

The study applied a cross-sectional survey design since its data were gathered at a certain point in time (Creswell, Citation2019). This design was also attributed to its efficiency and cost-effectiveness in data collection and comparison at a certain point in time (Kothari, Citation2010). Sunflower farmers in Singida and Dodoma (Tanzania) formed the population of interest. Specifically, the study population, unit of analysis, and inquiry involved sunflower farmers from the study areas. Sunflower farmers were selected based on their age, prior experience in AVCF and living in the stated study areas. Based on this, farmers aged 18 years and above were selected, since it is the legally required age to be offered AVCF (Kombe et al., Citation2017). Also, farmers having prior involvement in AVCF of at least one year in AVCF were included in our study. Consideration of age and farming experience were complemented by farmers’ presence in the study areas. In doing so, our study ensured representation of the entire population in the survey. Generally, this resulted in suitable matching of the intended sample to our study objective leading to improvements of the study’s firmness, data trustworthiness and outcomes (Campbell et al., Citation2020). Additionally, non-probabilistic sampling, also recognized as the purposive sampling approach, was used to obtain the required representation of the entire population (Kumar, Citation2019; Rahman et al., Citation2022). This procedure is considered as easy, ready and fast, since sunflower farmers were chosen based on their proximity, convenient and accessibility to the data collectors (Sekaran, Citation2003). Therefore, purposive sampling method was used while based on the fact that, most of the sunflowers farmers in our study areas were located in Kibaigwa and Shelui in Dodoma and Singida region respectively.

As advocated by Matekele and Komba (Citation2019), Mbelwa et al. (Citation2019) and Tabachnick et al. (Citation2007), the sample size for the present study was established by using the formula N ≥ 50 + 8M. where M is the number of independent variables and N is the expected sample size. The basis behind application of this formula was non-existence of farmers’ sampling frame, which also contributed in the use of non- probability sampling procedures. Additionally, Malhotra et al. (Citation2003) and Tabachnick et al. (Citation2007) established that for studies employing multivariate data analysis methods, the sample size must be in agreement with the rule of thumb, which states that the sample size should be N ≥ 50 + 8 M. This implies that, for our current study which involves regression analysis, determination of sample size by using the stated formula was be adequately suitable. Therefore, as shown in , this study had six (06) independent variables; hence, in line with the proposed formula, the sample size should be more than or equal to 98 sunflower farmers. Data from 184 sunflower farmers were analyzed.

The primary data were collected between November 2022 and February 2023. A total of 256 survey instruments were distributed to the sunflower farmers. This was achieved through a drop-and-pick strategy (Creswell, Citation2019). This strategy involved dropping off the questionnaires to the required respondents and thereafter picking them after being engaged (Junod & Jacquet, 2022). This resulted in yielding more responses and much interactions with respondents, which stimulated engagement of the surveys.

Of the 256 questionnaires, 233 were collected from respondents. Of the collected questionnaires, 49 were unacceptable because they missed some information. For purpose of removing problematic issues, Hair et al. (Citation2010) recommended filtering out any respondents’ case from the obtained questionnaires when the missing information are greater than 50 percent. Based on this, 47 questionnaires had missing information mainly related with unengaged statements while 2 questionnaires were rejected because of being found to be outliers, hence discarded from final analysis. Generally, this resulted in 184 final usable questionnaires, signifying 79.01 per cent of the received questionnaires. On top of that, our study obtained informed consent from participants before collecting data in order to ensure ethical deliberations in research (Drolet et al., Citation2023). As suggested by Normand and Donohue (Citation2023) detailed explanations were provided to respondents associated with the study’s objective. This also assisted participants in having anonymity and voluntary involvement.

Measurements of the study variables

A five (5) point likert scale alternating from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1) was employed to measure the independent and dependent variables (Creswell, Citation2019). Consideration of such type of scale was based on its understandability among enumerators and respondents, less time consuming and absence of overwhelming to respondents (Creswell, Citation2019; Malhotra et al., Citation2003). All latent variables employed in this study were adopted and modified from previously validated studies. Precisely, modifications which were made to the statements related with wording, context and applicability to variables under considerations. More specifically, farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF as the dependent variable were measured using eight (8) statements adopted and adjusted from Weisberg et al. (Citation2011) and Luarn and Lin (Citation2005). Eight (8) items used to measure the perceived benefits of AVCF originated from Jebarajakirthy et al. (Citation2014), whereas perceived risk was measured using eight (8) statements taken and adjusted from Anita et al. (Citation2008). AVCF knowledge was measured using ten (10) statements from Jacoby and Kaplan (Citation1972), while social enterprise embeddedness was measured using four (4) items taken from Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019). Four (4) items used to measure perceived behavioral control over AVCF and subjective norms were adopted and adjusted from Alleyne et al. (Citation2017) and Ajzen (Citation1991).

Common method bias

For the purpose of assessing common method bias, Harman’s single factor test was conducted. This intended to establish if there are major variations between early and late respondents (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The findings revealed existence of a single-factor test variance of 35.871 percent which is less than 50 percent. Since the rule of thumb requires all included factors to be less than 50 percent of the variance, hence as per Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003) it is stated that there were no concern for common method bias.

Data analysis and findings

The analysis of descriptive data was aided by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. More specifically, partial least squares structural equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed to determine the factors affecting farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania. This was aided by the SMART PLS 3. The use of PLS-SEM in the current study was attributed to numerous factors, including its suitability for analyzing and evaluating complex statistical models concurrently (Hair et al., Citation2022) and models with a large number of constructs (Albert et al., Citation2022). Because under PLS-SEM, it is not significant to consider normality distribution, it provides more help in numerous situations when other analysis methods are not appropriate (Edeh et al., Citation2023; Farouk et al., Citation2018; Magno et al., Citation2022). Since PLS SEM considers inner and outer model, examination of the latent constructs and their items is undertaken through the inner model while management of the connection between latent dependent and independent constructs is done through the outer model (García-Fernández et al., Citation2018; Vinzi et al., Citation2010). This implies that, combination of these models has helped researchers to establish very broad relationships in our current study. Also, based on our study objective, PLS-SEM was regarded as robust method used in administering relationships amid latent variables while notwithstanding of normality concerns (Edeh et al., Citation2023). Generally, in our present study application of PLS SEM assisted much in developing comprehensive model and robust analysis of the connections between study variables.

Results for Descriptive Statistics of Demographic variables

As shown in , most of the respondents were male (69.6 percent). Most of them were between 26 and 35 years old (34.8 percent), whereas 69.6 percent were married and 30.4 were single. In terms of academic qualifications, the majority (47.8 percent) had primary education. Additionally, greater than half of the respondents (56.5 percent) had less than ten years of experience in agricultural activities. Further, more than half of the respondents (65.2 percent) had a yearly income in Tanzanian Shillings (TZS) from agricultural activities (sunflower farming) below TZS 10 million. Furthermore, the majority of respondents (48.9 percent) had farm sizes below 10 hectares.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents.

Results for descriptive analysis for latent constructs

The findings of the descriptive statistics shown in outline the various views of sunflower farmers regarding the determinants of their intention to seek AVCF. The expressed views are presented in terms of mean scores and standard deviations of the different constructs and indicators. The mean scores indicate the level of importance that the respondents, who are sunflower farmers in Tanzania, attach to each item. Considering the 5-point Likert-type items used in the current study, the mean values were grouped into three (3) sets, high, moderate, and low. For simple elucidation, scores between 1.00 and 2.33 are considered low, while moderate scores between 2.34 and 3.67, and those between 3.68 and 5.00 are regarded as high. This grouping has also been applied in previous studies, including those by Hansford and Hasseldine (Citation2012) and Woodward and Tan (Citation2015).

Table 2. Descriptive analysis for independent and dependent variables.

Based on , except for perceived behavioral control (mean = 2.95), the remaining factors that explain farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF had mean values above 3.00. Thus, perceived benefit (mean = 4.35), social enterprise embeddedness (mean = 4.18), perceived risk (mean = 4.16), knowledge (mean = 3.29), and subjective norms (mean = 3.20) were regarded as having high mean values. Additionally, the results suggest that the stated variables are substantial and need to be taken into account when addressing the intentions of sunflower farmers in relation to seeking AVCF. More precisely, the highest average score for perceived benefits indicates that sunflower farmers have a strong belief in the potential benefits they can achieve by seeking AVCF. This belief is based on their assessments and preferences regarding their involvement in AVCF. On the other hand, the embeddedness of social enterprises in AVCF signifies that farmers will show high acceptance of AVCF when embraced by various social-related activities.

In the case of the perceived risk of AVCF, its mean score indicates that sunflower farmers are expected to face a high level of risk when involved in AVCF. This mean value suggests that sunflower farmers perceive a high level of risk associated with their failure to repay loans on time, which could lead to unpleasant consequences. The lowest mean value of perceived behavioral control indicates that respondents had a low level of perceived behavioral control regarding sunflower farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This could be attributed to the perceived difficulties in seeking AVCF based on individuals’ past experiences. The dependent variable, which represented the intention to seek AVCF, had an overall mean value of 3.57. This suggests that sunflower farmers are highly inclined to seek AVCF.

Evaluation of the measurement model

To survey the association between study constructs, the measurement model was assessed using internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. indicates that the coefficients for Cronbach’s alpha were greater than 0.70, while the composite reliability was higher than 0.80. As advocated by past studies such as Edeh et al. (Citation2023) and Magno et al. (Citation2022) there is assurance of the measurement model in terms of reliability because the stated values are all above the required cut-offs. To assess the measurement validity of the model, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Discriminant Validity were considered. shows that AVE scores were greater than 0.50. Since the suggested value for AVE is more than 0.5, it is therefore confirmed that convergent validity has been attained (Hair et al., Citation2022). This implies that, since the AVE deals with establishing the degree of captured variance against measurement error, our results are regarded as very good because they represent more than 50 percent of the required values of convergent validity.

Table 3. Construct reliability and validity.

Moreover, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMTR) and Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criteria were applied to establish the discriminant validity of the measurement model. Since they are used to explain discriminant validity, they assist in evaluation of the distinctiveness of the constructs. In this case, discriminant validity under the Fornell-Larcker principle is guaranteed when the square root of AVE is higher than its correlation with all other constructs in the study. shows that the diagonal values (square roots of the AVE) are greater than the corresponding relationships between the constructs in a column and row. Therefore, since informs that these values are larger than correlation of variables, it is concluded that discriminant validity through Fornell-Larcker principle has been attained. On the other hand, it is required that the values for HTMTR should be below 0.85 in order to provide guarantee the existence of discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2022). Based on this, it is evident from that assurance of discriminant validity exists. This is because the values for the HTMTR were all below the prerequisite value of 0.85. Hence, it is stated that, HTMTR in our study performs well since it has helped in determination of distinctiveness of the constructs. Generally, existence of assurance in terms of discriminant validity, as demonstrated by our findings, offers indication for appropriateness of the measurement model for testing of hypotheses.

Table 4. Discriminant validity: Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

Table 5. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

Assessment of the structural model

The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each construct was computed after assurance in terms of the measurement model’s reliability and validity. This was intended to establish a test for multicollinearity issues in structural models. Generally, it is recognised that, multicollinearity takes place when association among multiple independent variables exist in the model under consideration. shows that our model is free of multicollinearity. This is enhanced by VIF values below the required maximum of 10, as advocated by Hair et al. (Citation2022). This implies that, since the VIF values specified in are expressively lower than 10, the degree of multicollinearity is also lower. Furthermore, previous works, such as Bruce et al. (Citation2023), and Owusu et al. (Citation2021), have emphasized the suitability of VIF values below 10, hence supporting our study ().

Table 6. Collinearity Statistics (VIF)-Outer VIF values.

Table 7. Construct Crossvalidated (Total).

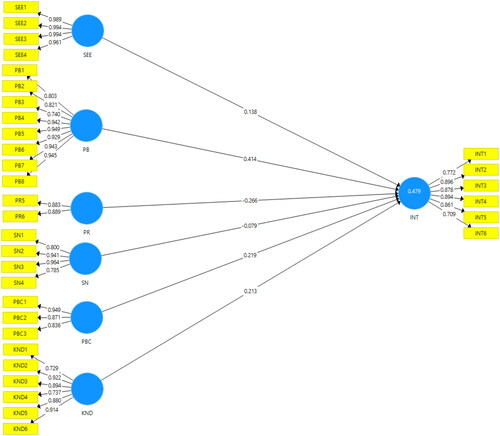

Additionally, the purpose of determining the explanatory power and goodness of fit of the model, the coefficient determination (R2) was calculated. As shown in , R2 is equal to 0.479, implying that 47.9 percent of the variance in farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF is explained by perceived benefits, perceived behavioral control, knowledge, subjective norms, social enterprise embeddedness, and perceived risk. This implies that, our model has moderate explanatory capacity since the R2 values is approximately equal to 50 percent. As advocated by Hair et al. (Citation2019) and Hair et al. (Citation2022), our model demonstrates the existence of goodness of fit.

Table 8. Hypotheses Testing.

In terms of the predictive significance of the models, blindfolding procedures were applied, which revealed that the Stone–Geisser (Q2) values were 0.328. This is shown in , signifying the presence of predictive relevance in the study model because the Q2 values for redundancy and communality are greater than zero (Fornell & Cha, Citation1994; Hair et al., Citation2022).

Additionally, it was deemed necessary to determine the contributions of every exogenous variable using the effect size (f2). As presented in , perceived benefits and perceived risk had moderate effects on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF, while perceived behavioral control, social enterprise embeddedness, knowledge, and subjective norms showed small effects on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. As advocated by Cohen (Citation1988), values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 are regarded as small, moderate, and large, correspondingly ().

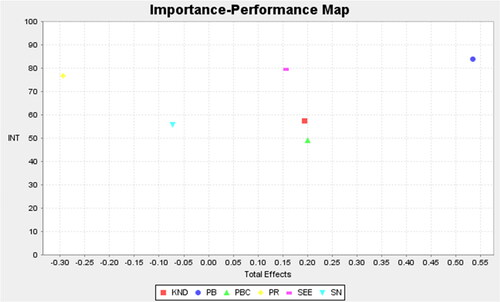

Finally, after testing the hypotheses, an Importance Performance Matrix Analysis (IPMA) was conducted. The IPMA meant to understand the most influential determinants which contribute in explaining farmers intentions to seek AVCF (Hock et al., Citation2010; Martilla & James, Citation1977). The results for the IPMA and its map are listed in and , respectively. establishes clearly how each of the variables incorporated in our present study is important in explaining farmers’ intentions to seek for AVCF. More specifically, findings show that the perceived benefits of AVCF is a more impactful predictor in the model for driving farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This is not amazing since the more AVCF companies guarantee farmers benefits in their provision of AVCF, farmers become highly benefited hence increasing farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. In doing so, sustainability of AVCF among farmers will be assured. Therefore, since perceived benefits exhibited the highest influence on farmers’ intentions to seek for AVCF, it is put forward that, policy movements which encourages AVCF practices must be given more efforts. Apart from that, and display that, the second most influential factors is social enterprise embeddedness, followed by farmers’ knowledge of AVCF, perceived behavioral control over AVCF, perceived risk and subjective norms. In this manner, drivers of farmers’ intentions to seek for AVCF must not be deliberated in the same way, since their importance and performance in explaining farmers intentions to seek AVCF is not equal. This implies that, in order to improve farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania, much consideration and deliberations must be given to perceived benefits, social enterprise embeddedness and knowledge of AVCF. This is also supported by Martilla and James (Citation1977), who concluded that variables with more total effects should be given much attention. This concurs with which indicates the direct total effects of perceived benefits (84.029 percent), social enterprise embeddedness (79.616 percent) and farmers’ knowledge of AVCF (57.513 percent) on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. Generally, prioritization and improvement in these variables could have thoughtful repercussions on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF.

Table 9. Importance-performance matrix for INT.

Results for hypotheses testing

Once the structural model was evaluated in terms of predictive power (Q2), effect size (f2), and IPMA, the significance of the path coefficients was determined. This was aimed at establishing the hypothesis testing. This was undertaken by applying bootstrapping procedures with 499 resamples. As our study intended to examine the factors explaining farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF, a one-tail test was performed. This was also attributed to the study hypotheses, which were all directional in nature. and present the path coefficients for each hypothesis.

According to the results offered in and , the perceived benefits of AVCF (PB) (β = 0.414, p = 0.000, and t = 7.757), knowledge of AVCF (KND) (β = 0.213, p = 0.040, and t = 2.059), and social enterprise embeddedness (SEE) (β = 0.138, p = 0.031, and t = 2.160) have a positive and significant effect on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF (INT). This shows that H1, H4 and H6 were statistically accepted by the data. Furthermore, the perceived risk of AVCF (PR) (β = –0.266, p = 0.000, and t = 4.399) had a negative statistical relationship with INT. Thus, H2 accepted. However, subjective norms towards AVCF (SN) (β = –0.079, p = 0.598, and t = 0.528) and perceived behavioral control over AVCF (PBC) (β = 0.219, p = 0.083, and t = 1.736) did not affect INT. Therefore, H3 and H5 were not supported.

Discussion of the results

This study examined the determinants of farmers’ intention to seek AVCF in Tanzania. As guided by the TPB, six (6) variables namely perceived benefit, perceived risk, knowledge, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and social enterprise embeddedness. The findings presented in and reveal a significant link between perceived benefit, perceived risk, knowledge, social enterprise embeddedness, and farmers’ intention to seek AVCF, but not between perceived behavioral control and subjective norms. This implies that H1, H2, H4 and H6 are statistically supported, whereas H3 and H5 are statistically rejected.

The presence of a significant positive connection between perceived benefit (H1) and farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania indicates that farmers perceive AVCF to be of greater benefit than the traditional financing mechanisms. This implies that, provision of AVCF leads to improvements of family income and wellbeing, increases farmers’ output and contributes in advancement of farming systems. Also, it can be stated that, AVCF results in improving standard of living among farmers, increased market access and provision of work among farmers. Empirically, this is in agreement with Dagnew et al. (Citation2024) and Kopparthi and Kagabo (Citation2012) who found that, provision of AVCF in Rwanda enhanced small scale farmers’ access to innovative financing, improved life quality, increased production and profit levels. This is also in agreement with Koh et al. (Citation2018) and Jiaping et al. (Citation2017). Generally, in the context of our current study, study’s findings present indication that provision of AVCF should be given much priorities since it brings considerable benefits among farmers and the national at large. Additionally, this is also supported by the empirical evidence of Dogeje (Citation2023), Mukucha and Chari (Citation2021), Mpeta (Citation2015), Marwa and Manda (Citation2022) that there is an increase of 24 percent in expected output per acre for farmers who are involved in contract farming as part of AVCF compared to non-contracted farmers. Additionally, it is also supported by Abedullah et al. (Citation2009), Joshi et al. (Citation2017), Jehan and Muhammed (Citation2008) and Nshom et al. (Citation2022), who declared that the provision of AVCF raises farmers’ productivity through increased income, making AVCF highly beneficial to farmers. Hu and Huang (Citation2018) and Martey et al. (Citation2019) contended that financing agricultural activities through AVCF improves the practical efficiency of farmers through the modernization of the agricultural sector in rural areas, thereby making them obtain the required benefits from the agricultural sector.

also reveals that the perceived risk of AVCF negatively influences farmers’ intention to seek AVCF in Tanzania. These findings concur with our prior expectations in H2 that farmers’ perceived risks of AVCF negatively influence their intention to seek AVCF. This means that farmers’ involvement in AVCF is embraced by various shortcomings that create negative perceptions. It can be considered that, for the purpose of increasing farmers’ participation in AVCF related risks in AVCF must be eliminated. Such risks consist of need for collateral, failure in repayment of finance which cause family disturbances, shame and embarrassments and sell of households properties to reimburse the AVCF. Therefore, management of these risks could lead to enhanced farmers’ intentions to look for AVCF. Previous studies such as Jebarajakirthy et al. (Citation2014), Li et al. (Citation2011), Oberholster et al. (Citation2015), Saqib et al. (Citation2016) and Turvey and Kong (Citation2010) support our findings by stating that risks related to unpredictable weather, such as unreliable rainfall, discourage farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This in turn impairs farmers’ ability to repay loans from AVCF, thereby creating unpleasant and negative perceptions of farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. In other words, the existence of high risk among farmers related to AVCF sends a message that there are still combinations of various risk factors affecting farmers (Choudhury et al., Citation2022; Kyire et al., Citation2023). According to Cantillo and Van Caillie (Citation2023), this leads to unpleasant perceptions of AVCF among farmers. Generally, Chen et al. (Citation2015), Zander (Citation2015), Madamombe et al. (Citation2024) and Villalba et al. (Citation2023) emphasized that, when policy makers and providers of AVCF rethink about these constraints, provision of AVCF will be highly sustainable and beneficial to various farmers.

Knowledge of AVCF revealed a positive and significant relationship with AVCF in Tanzania. This is in line with H4, that knowledge of AVCF positively influences farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This signifies that when farmers possess general knowledge and understanding of various AVCF products, their intention to seek AVCF continues to increase. More specifically, this informs that, when farmers have desirable awareness about AVCF concepts and providers, understand preconditions and procedures needed for AVCF their intentions to seek AVCF will be highly enriched. This is also in agreement with Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019), Rugeiyamu et al. (Citation2023), Shim et al.(Citation2009) and Xiao et al.(Citation2011) who concluded that customer knowledge and understanding of financial products influence their purchasing intentions. This is also in agreement with previous studies, such as Jafar et al. (Citation2023), Nautiyal and Lal (Citation2022), Roh et al. (Citation2022) and Zhou et al. (Citation2022). These studies concluded that perceived knowledge positively influences the purchasing intentions of various products, including AVCF. In our current study, this implies that farmers with adequate understanding and knowledge of AVCF increase their intention to seek AVCF.

Additionally, the study’s findings confirm the presence of a positive and significant association between social enterprise embeddedness and farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania. This concurs with H6. These results indicate that AVCF embedded with the provision of social welfare services, such as improvement of quality farmers’ lives, increases their intention to seek AVCF. For this case, it is put forward that, embeddedness of agricultural enterprises in terms of strong and reliable communications between farmers and AVCF providers, existence of common trust amid farmers and provision of farming skills accompanied with agricultural entrepreneurships results in greater intentions of farmers to seek AVCF. Practically, these results imply that, for the aim of promoting and developing entrepreneurial activities among farmers, social enterprises such as AVCF providers play a substantial role among farmers. This tells us that, embracement of social enterprises add value in creating agricultural productions, sustainability and innovations among farmers. Therefore, in order to raise standard of living among farmers, social enterprises among farmers should be highly promoted and given priority in various rural areas. As per Aisaiti et al. (Citation2019) and Lee and Deng (Citation2018), the principal motivation of social enterprises is to improve the quality of life of vulnerable groups, such as small-scale farmers. In addition, Lee and Deng (Citation2018), Swamy and Dharani (Citation2016) and Villalba et al. (Citation2023) documented that the involvement of SEE in AVCF creates an enabling environment for effective introduction and acceptance of AVCF among farmers. Therefore, when AVCF is embedded in various social enterprises, such as the provision of entrepreneurship skills and other related activities that advance the lives of vulnerable farmers, the intentions of farmers seeking AVCF increase. Earlier studies, such as Doherty et al.(Citation2014), Peter et al. (Citation2024) and Wang et al. (Citation2015), put forward that social enterprises help enhance the value of society through the integration of agricultural innovations, business sustainability and social welfare.

Oppositely, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control showed insignificant correlations with farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This implies that H3 and H5 were statistically rejected. Since subjective norms involve perceived social pressure that contributes to engagement in a particular activity, our results imply a negative relationship between subjective norms and farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. These results are not surprising since AVCF is still considered as a new practice, hence being regarded as uncommon financing strategy among farmers. Based on this, it is reflected that social influences originating from family members, close friends and undesirable commendations from communities create negative predictions among farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. These findings are inconsistent with those of Amin (Citation2013), Butler et al. (Citation2012), Sarikhani and Ebrahimi (Citation2022) and Waris et al. (Citation2023). Such studies have concluded that subjective norms are predictors of customers’ intentions to purchase financial products. However, the existence of study findings that are contrary to those of other scholars may be attributed to the newness of AVCF in developing countries, mainly due to being contrary to traditional financing mechanisms. This suggests that it may be challenging to obtain the positive perceptions of friends and family members regarding farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania.

Perceived behavioral control was expected to positively influence farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF (H5). The findings presented in and indicate the presence of an insignificant positive affiliation between perceived behavioural control and farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. Thus, H5 is unsupported. These findings imply that, sunflower farmers’ behaviour related with AVCF is not suitable for them to seek AVCF. This means that, capacity of farmers to apply for AVCF, use it and make required repayments is not promising. These findings contradict the TPB, as advocated by Ajzen (Citation1991), as well as preceding studies, such as Butler et al. (Citation2012) and Jebarajakirthy et al. (Citation2014). These studies highlight that customers’ intention to look for or purchase a particular financial product is significantly accelerated by perceived behavioral control over such products. On the other hand, since perceived behavioural control has been documented by prior studies that, it has the ability to influence purchasing behaviour (Acikgoz et al., Citation2023; Baluku et al., Citation2023; Nogueira et al., Citation2023), this is not the same with sunflower farmers. This indicates that farmers who are accustomed to traditional financing face challenges in the application of innovative financing such as AVCF (Villanueva-Flores et al., Citation2023). According to Isaga (Citation2018), the presence of high interest rates and low repayment ability for agricultural credit affects farmers’ behavior related to AVCF.

Conclusion, implications and areas for further studies

Conclusion

The major purpose of this study was to examine the factors explaining farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania. The inadequacy of studies on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in developing countries such as Tanzania motivated the current study. More specifically, the present study intended to test the direct influences of subjective norms, perceived benefit, perceived behavioral control, perceived risk, knowledge, and social enterprise embeddedness on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. To achieve this, extended TPB was considered to establish a conceptual framework for the present study. The theoretical underpinnings and arguments were empirically tested in the Tanzanian context, mainly on sunflower farmers in the Dodoma and Singida regions.

Based on the findings, the present study concludes that perceived benefit, knowledge, social enterprise embeddedness, and perceived risk are the principal factors driving farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania. This indicates that farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF increase when there is an increase in perceived benefit, knowledge, and social enterprise embeddedness in AVCF. This implies that, in order to improve farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania, much consideration and deliberations must be given to perceived benefits, social enterprise embeddedness and knowledge of AVCF. However, the effect of farmers’ perceived risks of AVCF on intentions to seek AVCF was significantly negative, implying that the existence of a higher level of risk diminishes farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. However, the findings reveal an insignificant association between perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. On top of that providers of AVCF, government authorities and related stakeholders are encouraged to pay much attention on the role of perceived benefit, risk, knowledge and social enterprise embeddedness on AVCF. In doing so, provision and implementations of AVCF among farmers will be fundamentally heightened. Generally, these findings are valuable for policymakers attempting to advance countrywide farmers’ acceptance and implementation of AVCF through regulating and controlling leading drivers of the farmers’ willingness to seek AVCF.

Implications of the study

The conclusion of this study add to AVCF literature in numerous ways. First, the findings indicate that perceived benefit, knowledge, and social enterprise embeddedness as well as perceived risk are motivating factors for farmers to look for AVCF in Tanzania. In practice, this suggests the need for stakeholders, policymakers, and providers of AVCF to create adequate farmers’ awareness of AVCF. This will make them appreciate the benefits enjoyed and the risks associated with participating in AVCF. More explicitly this implies that, providers of AVCF should design AVCF products which offer sustainable benefits to farmers so as to raise their households’ income, quality outputs, access to market and improve their living standard. In ensuring attainment of this, government authorities should design AVCF policies and guidelines which requires AVCF providers to embrace innovative agricultural financing products which ensures mutual benefits among farmers. To achieve this, specific collaborations related with AVCF implementations, monitoring and evaluations among AVCF providers, policy makers and farmers is highly recommended.

Second, this study adds more theoretical insights into the application of TPB in innovative agricultural financing. It was conceived that, TPB was not originally developed for agricultural financing. However, the current study demonstrated the suitability of TPB in examining farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This is evidenced by the results that additional constructs, such as social enterprise embeddedness in AVCF and knowledge and perceived benefits of AVCF, have significant influences on farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. This implies that our current study offers a valuable contribution to the TPB by including additional indicators known as social enterprise embeddedness, knowledge, and perceived benefits of AVCF, while considering farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. To the preeminent of our knowledge, this is the pioneer study to consider TPB in the context of AVCF intentions. Therefore, our study has added novel antecedents to TPB that aid in explaining farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in developing countries, such as Tanzania.

Third, the embeddedness of social enterprises in the AVCF has social implications for farmers. This originates from the view that the provision of AVCF should embrace social enterprises, such as supporting social missions, including improving the lives of vulnerable farmers. Since the motives of social enterprises, such as providers of AVCF, are to advance the quality of life of vulnerable groups, such as small-scale farmers, consideration of social enterprises in providing AVCF will assist in the eradication of poverty among defenseless farmers. Based on this implication, it is stated that AVCF providers will not only provide agricultural financing to farmers but also offer other related social services, such as entrepreneurial projects among farmers. This will contribute to enhancing the quality of life of vulnerable groups such as subsistence farmers.

Additionally, based on the significance of the embeddedness of social enterprise in innovative agricultural financing such as AVCF, our study advocates managerial implications to AVCF providers. This implies that, providers of AVCF should improve their means of incorporating social enterprise in the provision of AVCF among farmers.

Finally, this study offers managerial implications to the government, providers of AVCF, and related stakeholders. More precisely, local government authorities should offer adequate training and awareness to farmers related with appropriateness of AVCF. This could be conducted through seminars and workshops in various rural communities. In doing so, farmers’ knoweldge and understanding of AVCF will be enhanced, hence improving their intentions to seek AVCF. Also, central government through the ministry of agriculture in collaboration with the ministry of finance should develop AVCF policies and guidelines that support farmers’ engagement in innovative and sustainable agricultural financing like AVCF. This submits that some challenges in inspiring farmers to look for AVCF will not be resolved unless proper policies and guidelines are in place to motivate farmers to perceive AVCF as advantageous. Generally, non-existence of conducive policies and guidelines, may still subject farmers being exploited by providers of traditional financing. Additionally, based on the significance of the embeddedness of social enterprise in innovative agricultural financing such as AVCF, our study advocates managerial implications to AVCF providers. This implies that, providers of AVCF should advance their means of incorporating social enterprise in the provision of AVCF among farmers. AVCF providers are encouraged to promote AVCF which offers holistic agricultural and social enterprise among farmers. This can be achieved through, provision of AVCF which embraces social and agricultural enterprise, hence supporting in increasing entrepreneurial activities as the results of holistic AVCF. This in turn will help in improving agricultural market accessibility, efficiency and quality social services in various rural areas.

Limitations and areas for further studies

Although the current study offers useful understandings into the determinants of farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF in Tanzania, it has some limitations that call for future research. The current study engaged a cross-sectional survey design that did not consider behavioral variations among farmers (respondents). Therefore, further studies employing a longitudinal design may be carried out to overcome behavioral changes while testing conceptual models among respondents. In doing so, information for various periods of time will be collected while solving limitations of a cross-sectional survey design. On the other hand, based on the limitations of the survey instrument for primary data collection and the quantitative nature of the current study, future studies may adopt a qualitative approach and associated techniques to elicit farmers’ opinions on AVCF. This will assist in handling precincts of survey instrument related with farmers’ unwillingness to participate in the survey and non- capturing of inner farmers’ opinions. Although much attention was taken for controlling response bias, it cannot be absolutely eliminated. Therefore, employment of qualitative approach will aid in generating inner opinions from farmers unlike with the quantitative study.

Additionally, the outcomes of this study may not be generalizable to other developing nations, since it was undertaken in only one country, Tanzania. This suggests the need to replicate the current study in other developing and emerging states to ascertain the comparability of the findings.

Finally, this study examined the direct effect of the determinants of farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF; further recommendations call for studies on the indirect effects of introducing moderator and mediator variables. This will also provide more detailed and broader empirical insights and knowledge regarding farmers’ intentions to seek AVCF. Generally, besides these limitations, still our current study’s findings offer the significance of the empirical understanding of the drivers of farmers’ intentions to seek for AVCF while sustained by the TPB.

Author contributions

All listed authors contributed equally in the development and writing of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Charles K. Matekele

Charles K. Matekele is a Lecturer (Accounting, Taxation and Finance) at the Local Government Training Institute (LGTI) Dodoma, Tanzania. He holds Msc.(Accounting and Finance), Bcom(Accounting), CPA(T), CPB(T), and Tax Consultant. He is interested in innovative financing, financial reporting, IPSASs, auditing, risk management, fraud management, taxation, forensic investigation and corporate governance.

Prisca P. Rutatola

Prisca P. Rutatola is an Assistant Lecturer (Procurement and Supply Chain Management) at the Local Government Training Institute (LGTI), Tanzania. She holds a Master’s Degree in the field and her research interest areas includes procurement, logistics, supply chain, value chain, transportation, warehouse, freight management, procurement audit and risk management.

Marko M. Imori

Marko M. Imori serves as a Lecturer (Accounting and Finance) at the Local Government Training Institute. Currently, he is a PhD candidate at the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. Mr. Imori has conducted research, provided consultancy services and his research interests include finance, accounting, behavioural finance, financial markets, M&E and investment.

References

- Abedullah, N., Khalid, M., & Kouser, S. (2009). The role of agricultural credit in the growth of livestock sector: A case study of Faisalabad. Pakistan Veterinary Journal, 29(2), 1–26.

- Abbas, Q., Han, J., Bakhsh, K., Ullah, R., Kousar, R., Adeel, A., & Akhtar, A. (2022). Adaptation to climate change risks among dairy farmers in Punjab, Pakistan. Land Use Policy, 119, 106184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106184

- Albert, P., & Ren, C. (2001). Microfinance with Chinese characteristics (Vol. 29 No. 1, pp.39–62). World Development. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00087-5

- Acikgoz, F., Elwalda, A., & De Oliveira, M. J. (2023). Curiosity on cutting-edge technology via theory of planned behavior and diffusion of innovation theory. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 3(1), 100152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100152

- Aisaiti, G., Liu, L., Xie, J., & Yang, J. (2019). An empirical analysis of rural farmers’ financing intention of inclusive finance in China. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(7), 1535–1563. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2018-0374

- Ajambo, S., Ogutu, S., Birachi, E., & Kikulwe, E. (2023). Digital agriculture platforms: Understanding innovations in rural finance and logistics in Uganda’s Agrifood sector (Vol. 5). Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

- Ajzen, H., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Albert, A., Leonardi, F., Juliana, J., & Djakasaputra, A. (2022). An explanatory and predictive PLS-SEM approach to the Relationship between Product Involvement, Price and Brand Loyalty. Journal of Information Systems and Management (JISMA), 1(4), 32–41.

- Alleyne, P., & Harris, T. (2017). Antecedents of taxpayers’ intentions to engage in tax evasion: Evidence from Barbados. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 15(1), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-12-2015-0107

- Alleyne, P., Charles-Soverall, W., Broome, T., & Pierce, A. (2017). Perceptions, predictors and consequences of whistleblowing among accounting employees in Barbados. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(2), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2016-0080

- Amin, H. (2013). Factors influencing Malaysian bank customers to choose Islamic credit cards. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 4(3), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-02-2012-0013

- Ammar, A., & Ahmed, E. M. (2016). Factors influencing Sudanese microfinance intention to adopt mobile banking. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1154257. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1154257

- Anita, L. Z., Hanmer-Lloyd, S., Ward, P., & Goode, M. M. H. (2008). Perceived risk and Chinese Consumers’ Internet banking services adoption. The International Journal of Bank Marketing, 26(7), 505–525.

- Barraket, J., McKinnon, K., Brennan-Horley, C., & De Cotta, T. (2022). Motivations and effects of ethical purchasing from social enterprise in a regional city. Social Enterprise Journal, 18(4), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-03-2022-0029

- Baluku, M. M., Nansubuga, F., Nantamu, S., Musanje, K., Kawooya, K., Nansamba, J., & Ruto, G. (2023). Psychological capital, entrepreneurial efficacy, alertness and agency among refugees in Uganda: Perceived behavioural control as a moderator. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 2023, 23939575231194554. https://doi.org/10.1177/23939575231194554

- Bobkina, J., & Domínguez Romero, E. (2022). Exploring the perceived benefits of self-produced videos for developing oracy skills in digital media environments. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(7), 1384–1406. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1802294

- Butler, L. M., Kobati, G. Y., Anyidoho, N. A., Colecraft, E. K., Marquis, G. S., & Sakyi-Dawson, O. (2012). Microcredit–nutrition education link: A case study analysis of ghanaian women’s experiences in income generation and family care. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 12(49), 5709–5724. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.49.ENAM3

- Bhatia, M. S., Chaudhuri, A., Kayikci, Y., & Treiblmaier, H. (2023). Implementation of blockchain-enabled supply chain finance solutions in the agricultural commodity supply chain: a transaction cost economics perspective. Production Planning & Control, 2023, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2023.2180685

- Bruce, E; Zhao, S, Ying, D. Meng, Y., Amoah, J., Egala, S. B (2023). The effect of digital marketing adoption on SMEs sustainable growth: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Sustainability [online], 15(6). Dostupnéz: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/6/4760

- Byerly, R. T. (2014). The social contract, social enterprise, and business model innovation. Social Business, 4(4), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1362/204440814X14185703122883

- Cannas, R. (2023). Exploring digital transformation and dynamic capabilities in agrifood SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(4), 1611–1637. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1844494

- Casuga, M. S., Paguia, F. L., Garabiag, K. A., Santos, M. T. J., Atienza, C. S., Garay, A. R., … Guce, G. M. (2008). Financial access and inclusion in the agricultural value chain. APRACA IFAD, Janvier.

- Cantillo, J., & Van Caillie, D. (2023). Understanding European aquaculture companies’ perceived risks and risk management practices. Aquaculture Economics & Management, 27(4), 599–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/13657305.2022.2162625

- Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., Bywaters, D., & Walker, K. (2020). Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing: JRN, 25(8), 652–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.), Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Chan, K. H., Chong, L. L., & Ng, T. H. (2022). Integrating extended theory of planned behaviour and norm activation model to examine the effects of environmental practices among Malaysian companies. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 14(5), 851–873. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-08-2021-0317

- Chandio, A. A., Jiang, Y., Wei, F., Rehman, A., & Liu, D. (2017). Famers’ access to credit: Does collateral matter or cash flow matter? – Evidence from Sindh, Pakistan. Cogent Economics & Finance, 5(1), 1369383. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2017.1369383

- Chen, X., Wang, C., & Li, S. (2023). The impact of supply chain finance on corporate social responsibility and creating shared value: A case from the emerging economy. Supply Chain Management, 28(2), 324–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-10-2021-0478

- Chen, K., Joshi, P. K., Cheng, E., & Birthal, P. S. (2015). Innovations in financing of agri-food value chains in China and India. China Agricultural Economic Review, 7(4), 616–640. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-02-2015-0016

- Cheng, L., Nsiah, T. K., Sun, K., & Zhuang, Z. (2020). Institutional environment, technical executive power and agricultural enterprise innovation performance. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1743619. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1743619

- Choudhury, A., Jones, J., & Opare-Addo, M. (2022). Perceived risk and willingness to provide loan to smallholder farmers in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 23(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2020.1773732