?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

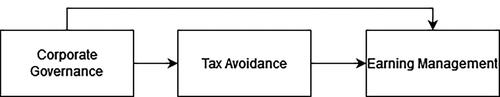

The study explores the impact of family versus non-family CEO management in Indonesian family companies on Corporate Governance (CG), Earnings Management (EM), and Tax Avoidance (TA). It examines if family-managed firms are more prone to EM than those with non-family CEOs, and considers TA as a mediator in the CG-EM relationship. This research is significant for understanding the dynamics of CG, EM, and TA within the unique context of Indonesian family businesses. It analyses how the leadership style of family CEOs, as opposed to non-family CEOs, influences these aspects. Based on the sample of the 117 family companies from 2018 to 2021, it has been found that tax avoidance partially mediates the relationship between corporate governance and earnings management in the full sample, family companies managed by family CEOs and family companies managed by non-family CEOs. Further, the results reveal that non-family CEO managed companies tend to exhibit lower levels of EM compared to those led by family CEOs. These findings contribute to the understanding of the dynamics of CG, EM and TA, and the leadership styles of family versus non-family CEOs. They also provide practical insights for policymakers and business practitioners in Indonesia, emphasizing the unique challenges and opportunities in family-run enterprises.

1. Introduction

Family companies are businesses in which the majority of shareholders are family members aiming to preserve their wealth across generations by holding key positions to pursue their personal interests (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2004; del Carmen Briano-Turrent & Poletti-Hughes, Citation2017).

These companies encompass two shareholder categories: minority shareholders (non-family members) and majority shareholders (family members). The latter group is more susceptible to conflicts typically stemming from minority shareholders (commonly known as agency problems). This observation is supported by Setiawan et al. (Citation2022), which underscores the active involvement of family members in managing the company, thus transforming agency conflicts from a manager-shareholder conflict (Agency Problem Type I) to a controlling-non-controlling shareholder conflict (Agency Problem Type II). Consequently, potential conflicts not only impact minority shareholders but also impede equity market development and limit access to capital markets (OECD, Citation2020).

Furthermore, family companies play a pivotal role in enhancing a country’s economic development, as exemplified by the world’s 500 largest family businesses, which outpaced global economic growth. They generated $8.02 trillion in revenue and employed 24.5 million people worldwide, including Indonesian companies like PT Gudang Garam Indonesia (rank 214) and PT Bank Central Asia (rank 328) according to the EY & University of St. Gallen Global Family Business Index (2023). This demonstrates the substantial growth of family companies in Indonesia compared to the global average.

A comparison between family companies in Indonesia and the USA reveals that both nations rely heavily on family companies, with the former contributing over 82% and the latter 60% to their respective GDPs in 2021 (Daya Qarsa, Citation2022; Van Der Vliet, Citation2021). However, a survey indicates that only 60% of family businesses in Indonesia believe they have the full trust of family members, which is lower than the global average of 74% (PwC, Citation2023) Consequently, it can be inferred that family companies are significantly influential in the global business landscape.

Additionally, the Asian financial crisis of 1997 exposed the detrimental consequences of poor governance within corporations, highlighting the need for a more discerning evaluation of CG effectiveness in fostering a country’s economic growth (Hillier et al., Citation2011; Shah & Shah, Citation2014). This is reinforced by the increasing instances of financial statement fraud within well-known corporations such as Olympus Corporation, Enron, and WorldCom. Hence, the implementation of robust CG ensures transparent financial reporting, thereby reducing the incidence of earnings management (Hunton et al., Citation2006).

This assertion finds support in the context of Indonesia’s economic crises in 1998, 2008, and the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. These events led to numerous corporate bankruptcies and an uptick in unemployment rates (Tambunan, Citation2019). Nevertheless, several Indonesian family companies weathered these crises successfully, including Media Nusantara Citra Tbk, Sat Nusapersada Tbk, Gudang Garam Tbk, Ciputra Development Tbk, and Mayora Indah Tbk. demonstrating that family-owned businesses, through the implementation of effective CG practices, can make a positive contribution to the Indonesian economy.

Family companies can be overseen by family or non-family members. Earlier research suggested that a higher presence of family members within the company could significantly reduce efforts to mitigate earnings management (EM) (Feki Cherif et al., Citation2020). However, other studies provide contrasting evidence (Eng et al., Citation2019; Stockmans et al., Citation2010) indicating that family companies exhibit more pronounced EM activities, especially during periods of poor performance.

1.1. Background and motivation

Indonesia’s corporate landscape is significantly influenced by family firms, which play a crucial role in the nation’s economy (Kristanti et al., Citation2016; Soleimanof et al., Citation2018). These companies are often characterized by unique governance structures, with family members holding key positions. This familial involvement can lead to distinct challenges, particularly in the realms of Corporate Governance (CG) and Earnings Management (EM) (Bergmann, Citation2023).

The influence of family members in executive roles raises pertinent questions about the effectiveness of corporate governance practices. In many cases, family ties may lead to a concentration of power, potentially compromising the objectivity and effectiveness of decision-making processes (Basco, Citation2013). This concentration of power can lead to governance challenges, particularly in transparency and accountability, which are vital for investor trust and market efficiency (Aguilera & Crespi-Cladera, Citation2016).

Moreover, the role of EM in these firms is of significant interest. The desire to maintain control and project stability might motivate family CEOs to engage in EM practices, differing from those employed by non-family CEOs (Gottschalck et al., Citation2023; Oware & Appiah, Citation2022). This potential variance in practices between family and non-family managed firms forms a critical area of investigation, as it might have substantial implications for stakeholders and the broader market.

The backdrop of this study is also set against the evolving Indonesian regulatory and economic environment, which has seen significant changes in CG standards and practices. These changes aim to enhance transparency and accountability in businesses, thus influencing how companies, especially family-run, navigate these regulations while maintaining their competitive edge.

The study is motivated by the need to understand how family dynamics within Indonesian firms influence CG and EM practices. This understanding is crucial for developing more effective governance mechanisms and for providing insights into the unique challenges faced by family firms in Indonesia.

1.2 Research questions and objectives

This study is structured around several pivotal research questions and objectives, each designed to deepen our understanding of CG, Tax Avoidance (TA), and EM in the context of family and non-family CEO-led Indonesian companies.

The foremost inquiry of this research is to ascertain how TA mediates the relationship between CG and EM. This question arises from the observation that TA practices might not just be a consequence of CG but could also influence how firms manage their earnings.

The study also aims to explore the differences in EM practices between family and non-family CEO led companies. This includes investigating whether family CEOs, driven by their desire to retain control and protect family wealth, are more or less inclined towards EM compared to their non-family counterparts.

Theoretically, the research intends to enrich the literature on CG and EM by integrating the often-overlooked variable of TA. It seeks to bridge the gap in understanding how different leadership structures within companies influence their financial reporting practices and compliance behaviors.

Practically, the study aims to offer insights useful for policymakers, regulators, and practitioners in enhancing CG frameworks, particularly in family-dominated business environments. By understanding the nuances in how different types of CEOs manage earnings, regulatory bodies can tailor more effective governance policies.

Finally, the study endeavors to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by providing empirical evidence from the Indonesian context, a relatively under-explored area in this field of study, thereby adding a valuable perspective to the global discourse on CG, TA, and EM.

1.3 Theoretical and empirical motivation

The theoretical and empirical motivation for this study is rooted in a multi-faceted understanding of CG, EM and TA in the context of Indonesian businesses.

The research is primarily anchored in agency theory, which postulates conflicts between principals (shareholders) and agents (managers). In family firms, this conflict may manifest distinctly, influencing CG practices and EM tendencies (Armstrong et al., Citation2010; van Essen et al., Citation2015). The study also draws upon stewardship theory, particularly relevant for understanding family CEOs’ motivations and actions.

Empirically, there exists a notable gap in understanding the interplay between CG, TA, and EM in the Indonesian setting, especially in family-run businesses. Previous studies have extensively examined these aspects in Western contexts, but there’s a dearth of comprehensive research focusing on Indonesia, where family businesses dominate the economy.

The empirical aspect of this study is motivated by the need to provide concrete evidence on how governance structures in family firms influence their approach to TA and EM. The unique socio-economic and regulatory landscape of Indonesia provides an ideal setting to explore these dynamics.

This research aims to merge theoretical concepts with empirical data, providing a robust framework for understanding the real-world implications of CG, TA, and EM in family versus non-family CEO-led companies. By doing so, it seeks to offer insights that are both academically rigorous and practically relevant.

Ultimately, the study endeavors to enhance existing theoretical models by incorporating findings from an emerging economy context, thereby broadening the scope and applicability of these theories in global business practices.

1.4 Contributions to the literature

This research endeavors to make several key contributions to the existing body of literature in the field of CG, TA and EM:

New insights in the Indonesian context: By focusing on Indonesia, a relatively underexplored region in this field, the study provides fresh insights into how cultural, regulatory, and economic factors in emerging markets influence corporate behaviors.

Family vs. non-family CEO analysis: The comparative analysis of family and non-family CEO led firms in terms of CG, TA, and EM practices fills a significant gap in current research. This distinction is critical in understanding the diversity of CG models and their outcomes.

Role of tax avoidance: By examining TA as a mediating factor in the relationship between CG and EM, the study adds a new dimension to existing theories, challenging and extending the conventional understanding.

Practical implications for policy and governance: The findings of this research hold practical value for policymakers and CG practitioners. By shedding light on the nuances of governance in different corporate structures, the study aids in the formulation of more tailored governance policies.

These contributions collectively enhance our understanding of corporate practices in emerging markets and offer a nuanced perspective on the interplay between CG, tax practices and EM.

2. Background

2.1 Indonesian corporate governance reforms

In the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Indonesia embarked on significant CG reforms. This period marked a fundamental shift, aiming to enhance transparency and accountability within the corporate sector. The reforms introduced stringent regulations and guidelines, focusing on improving CG structures in both family-owned and non-family businesses (Wijayati et al., Citation2016; Yin Sam, Citation2007). These changes were pivotal in addressing the previously prevalent issues of nepotism, lack of shareholder rights, and weak corporate boards. The reformation efforts were crucial in establishing a more robust, transparent, and accountable corporate environment in Indonesia, setting new standards for corporate conduct and governance practices (Amidjaya & Widagdo, Citation2019). These reforms have had a lasting impact on how Indonesian companies, especially family-run enterprises, operate and are governed, thereby providing a critical backdrop for understanding the current CG landscape in Indonesia.

2.2 Earnings management (EM) in Indonesian companies

EM in Indonesian companies, especially within the context of family-run businesses, presents a complex scenario. The Indonesian corporate sector, characterized by a mix of family-dominated firms and modern corporations, has witnessed diverse practices in financial reporting (Duygun et al., Citation2018; Kilincarslan, Citation2021). EM, the practice of using judgment in financial reporting to manipulate earnings to achieve certain benchmarks, has been a topic of growing interest and scrutiny in Indonesia. This focus is attributed to the unique corporate culture and governance structures prevalent in Indonesian companies, where EM can serve as a tool for achieving various objectives, ranging from maintaining family control to meeting market expectations (Efferin & Hartono, Citation2015; Efferin & Hopper, Citation2007). The exploration of EM in these settings is crucial for understanding the broader financial practices and implications for stakeholders in the Indonesian corporate landscape.

2.3 Role of tax avoidance (TA)

The role of TA in Indonesian companies is a critical aspect of the CG landscape. In Indonesia, TA practices have been a subject of concern and regulatory attention, given their potential impact on corporate transparency and accountability (Faisal et al., Citation2023; Rudyanto & Pirzada, Citation2021). These practices, often adopted as strategies to minimize tax liabilities, can significantly influence a company’s financial health and reputation (Arieftiara et al., Citation2019; Guedrib & Marouani, Citation2023). In the context of this study, understanding TA is essential for examining its potential role as a mediator between CG and EM. This is particularly relevant in the Indonesian context, where varying levels of regulatory enforcement and CG standards can lead to diverse TA behaviors among companies, especially in family-run versus non-family-run businesses. The examination of TA practices in Indonesia thus offers valuable insights into the interplay between taxation policies, CG, and financial reporting practices.

2.4 Regulatory and policy developments

The landscape of regulatory and policy developments in Indonesia has significantly evolved, particularly in the realm of CG and financial practices (Jarvis, Citation2012; Robison & Hadiz, Citation2017). These developments have been driven by a need to align Indonesian business practices with global standards, especially after the Asian financial crisis. The reforms introduced have aimed to strengthen CG structures, enforce stricter compliance standards, and ensure greater transparency and accountability in business operations. This evolution of policies and regulations is pivotal in understanding the current practices of EM and TA in Indonesian companies, as they provide a legal and ethical framework within which these businesses operate. The continuous adaptation of these policies reflects Indonesia’s commitment to fostering a robust and transparent corporate sector.

2.5 Research context justification

Indonesia presents a compelling research context due to its unique blend of family-dominated businesses and evolving CG landscape. The substantial reforms and regulatory shifts in the wake of the Asian financial crisis have profoundly impacted corporate practices (Gellert, Citation2005). These changes, coupled with the significant role of family firms in the Indonesian economy, create a distinctive setting for examining CG, TA and EA. This backdrop offers a rich field for exploring how these elements interact in a rapidly developing economy, making Indonesia an ideal setting for this study.

3. Theoretical framework

3.1 Agency theory

In the context of this paper, Agency Theory is pivotal. Originally conceptualized by Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976), it suggests a potential conflict of interest between the principals (shareholders) and agents (managers) of a company. This theory is particularly relevant to understanding CG in family-run businesses (Ahmed & Uddin, Citation2018; Aronoff & Ward, Citation1995). In such firms, the overlap between ownership and management could either mitigate or exacerbate agency problems. The theory predicts that where agency conflicts are high, practices like EM might be more prevalent as managers may prioritize personal goals over shareholders’ interests (Al-Begali & Phua, Citation2023; Martínez-Ferrero et al., Citation2016). This framework provides a lens through which we can examine the dynamics of EM and CG in family run Indonesian firms.

In Indonesian family-run companies, the overlap of ownership and management might lead to heightened agency conflicts, resulting in more pronounced EM behaviors. This hypothesis aligns with the theory’s suggestion that where managers’ interests are not fully aligned with those of the shareholders, they may engage in practices like earnings manipulation to serve personal or familial objectives (Bosse & Phillips, Citation2016; Pepper & Gore, Citation2015).

3.2 Tax avoidance as a mediator

TA is posited as a mediating factor between CG and EM. This perspective is based on recent research suggesting that the quality of CG can influence a firm’s approach to tax strategies, which in turn can impact EM practices. In family businesses, where CG structures may differ from non-family firms, the approach to TA could play a critical role in how earnings are managed. This framework thus aims to explore the mediating role of TA, offering a nuanced understanding of its impact within the context of Indonesian family businesses.

The governance quality in Indonesian companies, particularly in family-run firms, significantly influences their TA strategies, which in turn affects EM practices (Al-Begali & Phua, Citation2023; Gil et al., Citation2024). This hypothesis assumes that stronger CG leads to more ethical and transparent tax practices, thereby reducing the propensity for earnings manipulation. Conversely, weaker governance, potentially observed in some family businesses, might correlate with more aggressive TA and subsequent EM behaviors (Gaaya et al., Citation2017; Nazir & Afza, Citation2018).

3.3 Empirical studies on Earnings Management

The empirical studies on Earnings Management explores recent empirical evidence to understand the nuances of earnings manipulation in different corporate settings. It involves examining contemporary research findings, including those focusing on family firms. This framework seeks to analyze how EM practices vary depending on the company’s leadership and governance structure, drawing insights from recent empirical studies that delve into these distinctions. This approach is vital for understanding the current trends and patterns in EM across various types of companies, thereby enriching the overall investigation of this subject in the Indonesian corporate context.

There are discernible differences in EM practices between family and non-family firms in Indonesia, with family-run businesses potentially engaging in more conservative EM strategies (Al-Begali & Phua, Citation2023; Boonlert-U-Thai & Sen, Citation2019). This hypothesis is informed by empirical findings that suggest variations in EM behaviors based on the type of leadership and governance structures within companies, highlighting a potential distinction in financial reporting practices between these two categories of firms.

4. Literature review and hypotheses development

Family-run firms in Indonesia are more likely to engage in EM compared to non-family firms due to the heightened agency conflicts inherent in their governance structure (Bennedsen et al., Citation2022; Joko Pramono et al., Citation2022). This hypothesis draws from the theory’s assertion that conflicts of interest between shareholders and family-member managers could lead to practices that prioritize familial goals over shareholders’ interests, potentially manifesting in more pronounced EM behaviors in these firms.

Agency theory comes into play when a contract is established between one or more owners (principals) and a manager (agent) for the provision of services that involve delegating decision-making authority to the agent (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Consequently, agency theory is employed to address and mitigate issues that arise in a company due to the separation of ownership and management. This separation can give rise to agency costs related to aligning interests through monitoring efforts (Murni et al., Citation2023).

Previous research has categorized the causes of agency problems into two types: Agency Problem Type I and Agency Problem Type II. Agency Problem Type I stems from classical agency conflicts between the interests of the owner and the manager (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). In contrast, Agency Problem Type II represents a conflict between controlling shareholders (majority) and non-controlling shareholders (minority). This conflict typically emerges among controlling and non-controlling shareholders, as opposed to the conflict that exists between managers and shareholders in firms with dispersed ownership (Lin, Citation2017).

A family company denotes a company controlled by a family that plays a significant role as managers or owners. This type of company demonstrates that the concept of ownership goes beyond its legal dimensions (Miller et al., Citation2007; Zellweger, Citation2020). Companies under the control of family members also contribute to Type II agency conflicts, where the conflict arises between majority shareholders (controllers) and minority shareholders (non-controllers) (Wan Mohammad & Wasiuzzaman, Citation2020). Based on earlier research, it’s suggested that family companies with higher insider ownership have a greater propensity for engaging in Earnings Management (EM) (Jin et al., Citation2021).

Several criteria determine whether a company qualifies as family-owned. These criteria may include family ownership of shares accounting for at least 20% (Robin & Amran, Citation2016), family members holding at least 25% of shares with a minimum of two people in management roles (De Massis et al., Citation2013), and alternative thresholds of 10%, 30%, or 40% family ownership (La Porta et al., Citation1999).

The CEO of a company can either be a family member or a non-family member. For instance, Sat Nusapersada Tbk is led by a family CEO, while Bukit Darmo Property Tbk is headed by a non-family CEO. This distinction gives rise to varying agency conflicts between the CEO and the owner. Companies managed by family CEOs tend to require fewer executive compensation plans based on reported earnings for monitoring the CEO’s performance (Young & Tsai, Citation2008). This distinction suggests that family CEOs and non-family CEOs possess different incentives, impacting their behavior and EM activities.

Family companies have a better financial reporting if compared to other types of firm (Cascino et al., Citation2020), this shown by their high earnings informativeness and the ability in anticipating the future cash flows, as well as higher earnings response coefficients (Ali et al., Citation2007), fewer restatements (Tong, Citation2007), and greater likelihood of disclosing earnings warnings to reduce the probability of discretionary accrual actions (Chen et al., Citation2008; Jiraporn & DaDalt, Citation2009). However there are some different perspective, that argued family companies are negatively associated with financial reporting quality measured in terms of lower earning informativeness (Ding et al., Citation2011), higher use of discretionary accruals (Chi et al., Citation2015) and real earnings management activities (Razzaque et al., Citation2016).

Based on previous research on the effect of CEO and non- family CEO which effect EM, there are very diverse conclusions. This is evidenced by research results stating that, the propensity for family companies to manage earnings is higher in the case of non-family CEOs, relative to family CEOs, as their compensation is more often linked to the financial performance of the firm to align the interests of family owners and CEOs (Yang, Citation2010). This happens because family members who sit in top management lack competence and are less professional in managing the company (Murni et al., Citation2023), this tense to show that family CEO have higher probability in doing EM. Hence, this study hypothesizes the following:

H1: Family companies managed by non-family CEOs have lower levels of EM compared to family companies managed by family CEOs.

The economic crisis at the end of the 1990s in Indonesia, caused by the poor implementation of CG practices, including a lack of transparency, weak audit systems, and ineffective roles of the board of directors (Keuangan, Citation2014; Zhuang et al., Citation2000). These statements indicated that the main contributors to the economic crisis were the weak governance within companies, which had a significant impact on the urgency of reform, especially in Indonesia. Until 2020, an economic crisis emerged, affecting the entire world, including Indonesia. According to the Indonesia Central Statistics Agency (Badan Pusat Statistik, Citation2021), Indonesia experienced an economic contraction of -2.07% during the Covid-19 pandemic, leading to deflation. CG remains weak in most Indonesian companies. Therefore, the Covid-19 pandemic serves as a reminder to business owners about the importance of governance in their companies. Consequently, it can be concluded that the implementation of good CG will significantly affect a company’s operations and growth.

Recognizing the weak state of CG in Indonesia, the Financial Services Authority, Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK), created a roadmap to achieve better governance. This roadmap will be the primary reference for implementing good CG, particularly for public companies. Moreover, it will contribute positively, allowing Indonesia to align itself with CG practices in the ASEAN region to face the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. This endeavor will involve all stakeholders to support the success of this roadmap.

The impact of family companies on EM has been analyzed before, highlighting that governance characteristics of family companies can affect their tendency to manipulate earnings (Ansari et al., Citation2021). Prior studies offer differing opinions and present conflicting results. Brenes et al. (Citation2011) argue that the implementation of CG in family companies differs from that in general companies due to different ambitions and cultural practices that influence board composition (Luan et al., Citation2018).

It is suggested that governance characteristics of family companies can affect their inclination to manipulate earnings (Ansari et al., Citation2021). A study by Githaiga et al. (Citation2022) reveals that a low separation between ownership and control, assuming a larger board size, one of the elements of CG, may reduce the monitoring of the management team, increasing the risk of expropriation by controlling shareholders and the board members’ discretion in setting higher remuneration levels and manipulating company results for their own benefit. However, with the increasing competition in the business world, the director composition of family businesses has become more diverse. The mechanism of CG significantly negatively influences EM (Abbadi et al., Citation2016; Mahrani & Soewarno, Citation2018). This is evidenced by the previous studies, where family firm could retain better than their competitors would do: if we compared family firm work forces turned only 9% over annually, but non-family firm 11% over annually (Kachaner et al., Citation2012). Not only that, this statement is also supported by Zellweger et al. (Citation2011), which indicates that the average age of a firm that controlled by family is 60.2 years.

CG is a crucial factor influencing EM (Al-Zaqeba et al., Citation2022). This is supported by the practices of some major global and Indonesian companies engaging in EM, such as Enron in the United States, WorldCom in Italy, and PT Tiga Pilar Sejahtera Food Tbk in Indonesia (Othman & Zeghal, Citation2010; Raharjo, Citation2022). However, previous research on the influence of CG on EM has yielded inconsistent results, leading to this study to validate the findings related to these two variables. Some previous studies (Naz et al., Citation2023; Talbi et al., Citation2015) suggest that the board size, one of the CG elements, significantly and negatively affects EM. Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H2: The implementation of CG in family companies has a positive influence on EM.

The concept of TA as a Mediator in the relationship between CG and EM is a growing area of interest in corporate finance literature. Recent studies have begun to explore how tax strategies, influenced by governance structures, impact EM decisions. This area of research is particularly relevant in contexts where CG varies, such as in family versus non-family businesses. The mediation role of TA offers a nuanced understanding of the interplay between governance quality and financial reporting practices, highlighting how tax strategies can be a significant factor in corporate financial decisions.

CG not only impacts the behavior of employees and managers within a company but also has a significant influence on the TA activities undertaken by company owners. Previous research, as exemplified by Minh Ha et al. (Citation2022), demonstrates that TA is utilized by companies as a legitimate means to reduce their tax liabilities and as an internal resource management strategy to minimize external funding. Consequently, CG can affect the TA practices of a company, a notion supported by studies such as those conducted by Desai and Dharmapala (Citation2006); Chen et al. (Citation2022), which reveal that CG can exert a substantial negative impact on TA.

It is crucial to recognize that TA is not divorced from the CG mechanisms designed to influence decision-making and oversee the choices made by a company. The ownership structure of a company is a critical factor that must be taken into account, as it not only affects agency conflicts but also shapes the company’s behavior. As a result, several studies have emphasized that strong family ownership ties within a company can lead to increased tax-aggressive behavior.

TA involves company owners diverting wealth that should rightfully be contributed to state tax revenues. State tax revenues for the State Budget (APBN) encompass various categories, including Property Tax, Oil and Gas Income Tax, Non-Oil and Gas Income Tax, Other Taxes, VAT, and Luxury Sales Tax. The primary aim of this practice among company owners is to benefit shareholders and company managers by preserving higher income and limiting cash outflows for tax payments, as noted by Li et al. (Citation2017).

TA by a company can have a significant impact on a country’s tax revenues, particularly in the real of taxation. This is evident from the decline in Indonesia’s tax ratio from 11.6% in 2019 to 10.1% in 2020, representing a 1.5% decrease in the tax ratio, as reported by the OECD (Citation2022). Furthermore, in 2020, Indonesia’s tax ratio fell below the averages of other regions, including Asia-Pacific countries (19.1%), African countries (16.6%), OECD countries (33.5%), and Latin American and Caribbean countries (21.9%). Consequently, government policies are imperative to curtail tax avoidance practices in Indonesia.

Several studies also posit that TA can impact EM. Companies can reduce their tax expenses by deferring income recognition, a tactic categorized as TA. Such activities can lead to managerial decisions involving EM to manipulate financial reporting. This assertion is corroborated by Scott (Citation2012), who contends that companies engage in EM to reduce income tax burdens, thereby diminishing the amount of tax payable.

EM serves as a tool to adjust a company’s reported earnings, whether to increase or decrease them in financial reporting. This introduces a different dynamic when a company is led by a CEO who is a family member as opposed to an external individual. Given the opportunistic nature of managers, this can lead to strategies to engage in TA for personal gain, as observed by Paiva et al. (Citation2019).

H3: TA mediates the relationship between CG and EM

5. Research design

5.1 Sample and data

In this study, the company type under investigation aligns with the definition provided by De Massis et al. (Citation2013). Accordingly, we gathered 468 data samples of 117 family companies spanning a period of 4 years (2018–2021) that met these specified criteria and will be utilized in our research.

For data analysis, this study will apply panel regression by using Eviews. Prior to regression, we identified outliers in the dataset using the z-score method. Out of the 468 data collected from family companies managed by both family and non-family CEOs, 163 were identified as outliers and subsequently excluded from our analysis. Consequently, our analysis focused on 305 data. This same process was applied to both family companies managed by family CEOs and those managed by non-family CEOs, as presented in .

Table 1. Analysis of the sample.

The collected sample of family companies was then further categorized into two groups: those with family CEOs and those with non-family CEOs. This study encompasses three distinct research categories: family companies with family CEOs, family companies with non-family CEOs, and a combination of both.

5.2 Variables and measurements

The definitions and measurements of the variables included in this study are provided as follows:

5.2.1 Dependent variable

The calculation of EM is conducted using the Modified Jones models. These models exhibit minimal disparities when compared to the traditional Jones models. The primary distinction between the two equations lies in how EM is influenced by revenue and debt accounts (Peasnell et al., Citation2000). The process of computing EM through the Modified Jones model involves three stages (Dechow et al., Citation1995). In the first stage, both the Jones Model and The Modified Jones employ similar calculations for determining total accruals, as expressed by the formula:

The only variance in this first stage formula pertains to ΔSTDit, representing the difference between current liabilities in year t and current liability debt in year t-1. Otherwise, the calculations for EM using The Modified Jones align with those of the Jones Model. Following the completion of total accrual calculation, the estimation of normal accruals is required. The Modified Jones performs a time-series regression, differing from the Jones Model, which uses a cross-sectional approach. The second stage in The Modified Jones calculation is as follows:

Upon completing the second stage and determining the total normal accruals, the final step is to calculate discretionary accruals. The formula for discretionary accruals using The Modified Jones is as follows:

After completing all the steps above, the data is categorized into various segments based on predefined criteria. When assessing the EM results, a negative value indicates a company’s intent to minimize income through EM, while a positive value suggests a company’s aim to maximize income. A previous study by Indriani and Pujiono (Citation2021) has also explored this topic.

5.2.2 Independent variable

In this study, the independent variable is CG. We employed dummy variables, as outlined by Solikhah and Maulina (Citation2021), following a set of 20 questions that adhere to all the principles of CG established by OECD. These principles encompass transparency (5 questions), accountability (5 questions), responsibility (3 questions), independence (3 questions), and fairness and equality (4 questions).

All the data used to construct an index is sourced from the annual reports of the companies. This index, referred to as the CG Index (CGI), is determined as follows:

Total indicators: 20 items

5.2.3. Mediating variable

In this study, TA has been selected as the mediating variable. This choice is based on the support from several previous studies suggesting that TA can effectively serve as a mediator variable in this context.

The calculation method used here follows the formula provided by Henry and Sansing (Citation2018), where the Δ value represents the TA value of a company. When Δ equals 0, it signifies that the cash taxes paid are in line with the expected taxes. However, if Δ is greater than 0, it indicates that the cash taxes paid exceed the expected taxes, while if Δ is less than 0, it means that the taxes paid are less than the expected taxes.

Δ = Cash tax Paid – *(pre-tax income)

6. Emperical results and discussion

6.1. Descriptive statistics

illustrates the descriptive statistics for all variables employed in this study. From the findings, it can be observed that family companies exhibit an average EM of -0.22. This suggests a propensity for these firms to engage in EM with the objective of income minimization. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that not all family companies pursue this type of EM, as the range of EM spans from a minimum of -3.10 to a maximum of 1.50, indicating that some family companies also aim to engage in EM with the goal of income maximization.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for all family companies.

The mean of CG is 0.78, with a range of 0.66 – 0.91 and standard deviation is 0.07. These results suggest that family companies are likely to demonstrate strong governance, as the average significantly exceeds the standard deviation. As for TA, the mean of TA is 0.00, with a range of -0.02 to 0.02 and a standard deviation of 0.01. These findings imply that the variance in this measure is relatively high, given that the average is smaller than the standard deviation. In fact, the standard deviation is 0.8% larger than the average.

This study also conducts a comparative analysis between family companies managed by family CEOs and those overseen by non-family CEOs, as detailed in and .

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for family CEO managed companies.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for non-family CEO managed companies.

Comparing these two groups, the descriptive statistics reveal that the average EM differ with -0.19 for family CEOs and -0.39 for non-family CEOs. This indicates that family companies managed by non-family CEOs are less inclined to engage in EM. It can be assumed that companies led by professional CEOs are less likely to engage in EM, likely due to the greater experience possessed by family CEOs. Additionally, both types of companies tend to engage in EM with income minimization, as evidenced by the negative values.

The mean of CG in family companies managed by non-family CEOs show a slightly higher compared to those led by family CEOs. However, the difference between these two groups is not substantial, only around 0.01. Thus, it can be concluded that the governance of family companies managed by family CEOs and non-family CEOs does not significantly differ. When comparing TA between these two groups, the mean and standard deviation can be examined. There is no significant different between the mean of TA in family companies managed by family CEOs and those managed by non-family CEOs. The standard deviation of TA in family companies managed by family CEOs is 0.24% larger than the standard deviation of those managed by non-family CEOs.

6.2. Discussion and research results

In this study, an analysis is conducted on three separate entity categories: family companies, family companies managed by family CEOs, and family companies managed by non-family CEOs.

6.2.1 Family companies managed by non-family CEOs have lower levels of EM compared to family companies managed by family CEOs

In relation to Levene’s test concerning EM, it involves calculating variance and t-test values for the dependent variable to assess whether family companies led by non-family CEOs exhibit higher or lower levels of EM compared to those under family CEO management.

The outcome of Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances, as presented in , reveals a noteworthy value of 0.001, which is less than the significance level α = 0.05. This indicates a significant difference in variance between companies led by Family CEOs and those managed by Non-family CEOs. Additionally, the t-test for Equality of Means yields a significant value of 0.037, also below the α = 0.05 threshold. This implies that companies with Family CEOs exhibit higher levels of earnings management compared to those with non-family CEOs at the helm.

Table 5. Independent sample t-test.

reveals that companies managed by family CEOs have an average EM value of -0.152, which is higher compared to companies managed by non-family CEOs with an average of -0.308. Consequently, this test’s outcomes indicate that companies under non-family CEO leadership tend to exhibit lower levels of EM compared to those led by family CEOs, thereby confirming hypothesis H1. These findings align with prior research by Chi et al. (Citation2015); Razzaque et al. (Citation2016), which suggests that non-family CEOs often bring a greater level of professionalism and experience to company management. Additionally, these CEOs may encounter more significant challenges in engaging in activities like EM if they are at the helm of a family company.

Table 6. Performance mean of family CEO and non-family CEO managed companies.

The findings of the study align with agency theory, which suggests a conflict of interest between shareholders and managers (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). This theory has played a crucial role in understanding corporate behavior, especially in family businesses where ownership and management often overlap. In such contexts, conflicts within the agency relationship may manifest differently, impacting practices like earnings management. The success of a business heavily depends on the decisions made by its managers, and agency costs, encompassing monitoring, bonding, and residual expenses, play a pivotal role (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The fundamental tenets of agency theory are built on three hypotheses regarding human nature: (1) individuals tend to be self-centered, (2) people possess limited foresight about future perspectives, and (3) individuals generally aim to avoid unnecessary risks (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). According to Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976), the agency relationship is established when shareholders compensate agents for services and delegate decision-making authority. In practice, agents overseeing companies have access to more comprehensive internal information and accurate forecasts about the company’s future compared to shareholders. Therefore, it is essential for agents to fulfill their responsibility of keeping shareholders informed about the firm’s status to ensure effective agency relationships. The Stewardship Theory, offering a contrasting view to Agency Theory, suggests that managers in family businesses often act as stewards of the company, prioritizing organizational goals over personal gain. (Afonso Alves et al., Citation2021; Löhde et al., Citation2020). The alignment of interests between owners and managers could potentially reduce the incidence of EM, as the stewards are motivated by long-term success and legacy rather than short-term personal gains (Strike et al., Citation2015).

6.2.2. The implementation of CG in family firms has a positive influence on EM

In line with hypothesis H2, the results presented in demonstrate a positive and statistically significant association between corporate governance (CG) and earnings management (EM) in family-owned companies (the full sample). This implies that even family-owned companies with robust governance practices are not necessarily less prone to engaging in earnings manipulation. In simpler terms, the effectiveness of corporate governance does not appear to discourage family companies from manipulating their earnings. This outcome suggests that ownership structures with higher concentration among controlling shareholders, particularly in family-controlled companies, are linked to increased levels of earnings manipulation.

Table 7. Regression results.

This discovery aligns with prior empirical research conducted by Sáenz González and García-Meca (Citation2014); Aleqab and Ighnaim (Citation2021); TF Abuhijleh and AA Zaid (Citation2023). These studies assert that boards, when used as a governance tool, may introduce communication and coordination challenges, thereby diminishing their ability to oversee the management team effectively. Consequently, this can heighten the likelihood of earnings management and create information asymmetry within companies.

This research also reveals other interesting findings, where family-owned companies managed by both family CEOs and professional CEOs obtain significant negative results. In the case of family companies managed by family CEOs, the results suggest that a low level of corporate governance offers more significant opportunities for these companies to engage in earnings management. This statement can be interpreted as companies with strong corporate governance values, who comprehensively understand the principles of corporate governance, are less likely to engage in activities that could harm them.

Concerning the family companies managed by non-family CEOs, a significant and negative relation is detected between CG and EM. The results demonstrate that the better corporate governance and higher participation of independent directors or professional CEOs, the lower the level of earnings manipulation. As a governance tool, professional CEOs are less biased in their opinions because of the lack of personal interest in the company, the inexistence of family ties in the company’s ownership structure, and their more objective decision-making process. This finding in line with the study conducted by Saona et al. (Citation2020); Attia et al. (Citation2022). This results indicate that firms with strong corporate governance measures in effect do not exhibit a natural inclination to manipulate their earnings. This challenges established empirical research and theories that underscore the pivotal role of corporate governance in addressing agency problems, reducing information asymmetry, restraining managerial self-interest, and mitigating corporate risk (Nguyen et al., Citation2024).

Family-owned businesses in Indonesia are prone to a higher likelihood of participating in earnings management when contrasted with non-family enterprises. This inclination is attributed to the increased agency conflicts embedded in their governance framework (Bennedsen et al., Citation2022; Joko Pramono et al., Citation2022). This hypothesis stems from the theory’s proposition that the conflicting interests between shareholders and family-member managers may result in behaviors that prioritize familial objectives over the interests of shareholders. This could potentially manifest in more conspicuous instances of earnings management within these family-run firms.

6.2.3. TA mediates the relationship between CG and EM

As outlined by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), the process of mediation regression analysis involves three sequential steps, following the three-step regression approach detailed by Kassim et al. (Citation2013). In the initial step, we initiate by regressing the mediator against the independent variable to determine if there exists a statistically significant relationship between these two variables. Should a significant relationship emerge in the first step, we proceed to the second step, wherein we regress the dependent variable against the independent variable. Lastly, the third step entails regressing the dependent variable against both the mediator and the independent variable.

The findings for family companies, presented in , reveal the results of these three steps. In the first step, the analysis shows a significant negative relationship between CG and TA. Hence, based on this outcome, one could infer that a lack of understanding regarding CG principles within a company can contribute to deviant behaviors, such as TA. This finding is consistent with the study conducted by Lee and Bose (Citation2021)

Moving on to the second step, CG demonstrates a positive influence on EM. This implies that the presence of family members in family-owned businesses, regardless of the quality of CG implementation, does not necessarily diminish the likelihood of engaging in EM activities. This result contradicts hypothesis H2 and aligns with research by Shah et al. (Citation2009). In the third step, it is revealed that TA has a significantly negative effect on EM. This indicates that most family companies are inclined to minimize their tax obligations, which motivates them to manipulate reported profits in financial statements to reduce their tax liabilities. This finding is consistent with research conducted by Kałdoński and Jewartowski (Citation2020).

Upon completing all three steps, the results are compared to determine whether the coefficient changes from the second to the third step, indicating a mediating effect of the mediating variable. For family companies, the coefficient decreases from 3.9825 to -10.020, suggesting a partial mediation of TA in the relationship between CG and EM.

Regarding family companies managed by family CEOs, in the first step, the analysis demonstrates a positive and significant relationship between CG and TA. This suggests that a high level of CG encourages internal parties to engage in TA activities, as it offers various advantages such as dividends, increased company assets, and debt payments. These findings align with the research conducted by Sánchez-Marín et al. (Citation2016). In the second step, CG shows a negative effect on EM, indicating that effective CG implementation reduces EM activities. This result supports hypothesis H2 and corresponds with research conducted by Abbadi et al. (Citation2016).

In the third step, it is revealed that TA significantly negatively affects EM. This suggests that by minimizing tax obligations, companies increase their opportunities to engage in EM activities. These findings are in line with the research of Wang and Mao (Citation2021). After completing all three steps, a comparison of the results from the second and third steps indicates a decrease in the coefficient from -4.5434 to -7.1347 for family companies managed by family CEOs. This suggests partial mediation of TA on EM in this context.

The findings for family companies under non-family CEO management reveal significant results in the three-step process. In the first step, it becomes evident that there is a significant negative impact of CG on TA. Consequently, one can infer that when a company’s CG is weak, it creates more opportunities for internal parties to engage in tax avoidance activities, as indicated by Lee and Bose (Citation2021).

Moving to the second step, CG exhibits a negative influence on EM. This implies that a lower quality of CG within a company increases the likelihood of internal parties engaging in EM activities, as suggested by Achleitner et al. (Citation2014). This result supports hypothesis H2. In the third step, it is revealed that TA has a significantly negative effect on EM, consistent with the findings for family companies managed by non-family CEOs. This indicates that minimizing tax obligations creates more opportunities for the company to engage in EM activities, in line with the research by Wang and Mao (Citation2021).

Upon completing all three steps, a comparison of the results from the second and third steps shows a decrease in the coefficient for family companies managed by non-family CEOs, dropping from -4.0527 to -10.5590. This suggests a partial mediation of TA in the relationship between CG and EM.

Based on these results, it can be concluded that TA indeed exerts mediating effects on the relationship between the independent variable (CG) and the dependent variable (EM). This finding lends support to H3, applying to the entire sample of family companies, including those managed by non-family CEOs and family CEOs.

The result is in line with agency theory, indicating that in situations where the interests of managers do not completely align with those of shareholders, a robust corporate governance structure may prompt them to encourage internal parties to participate in tax avoidance activities. This is because such activities provide several benefits, including dividends, augmented company assets, and debt payments. Furthermore, managers may resort to practices such as manipulating earnings to fulfill personal or familial objectives.

6.3. Robustness analysis

The existing literature on EM presents different indicators for assessing EM (Jones, Citation1991; Kothari et al., Citation2005). Yet, limitations in the modified Jones models for cases with exceptionally strong or weak financial performance are highlighted by McNichols (Citation2000). To enhance reliability, we employ an alternative EM metric, calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation of operating earnings to the standard deviation of cash flow from operations, as proposed by Leuz et al. (Citation2003). This metric reflects the smoothness of earnings, with a higher value suggesting greater EM.

As shown in , consistent with our predictions, companies managed by family CEOs have an average EM value of 0.6429, which is higher compared to companies managed by non-family CEOs with an average of 0.5085. This test indicates that companies under non-family CEO leadership tend to exhibit lower levels of EM compared to those led by family CEOs.

Table 8. Alternative test- performance mean of family CEO and non-family CEO managed companies.

With respect to Hypothesis 2, the coefficients in step 2 for the three samples are significant and positive, and consistent with our primary results. These results suggest that the implementation of CG in family companies for the three samples has a positive influence on EM.

As suggested by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), mediation regression analysis needs to go through three steps. As summarized in , the coefficients in step 1 for full sample, family CEO and non-family CEO are significant and positive. Further, the coefficient for full sample, family CEO and non-family CEO in steps 2 and 3 is reduced by 13.71; 9.34; and 9.44 consecutively. This result fulfills the requirement of mediation analysis which confirm a partial mediation of TA in the relationship between CG and EM.

Table 9. Alternative regression results.

7. Summary and conclusions

The findings of this paper indicates that TA partially mediates the relationship between CG and EM in Indonesian family companies, whether managed by family or non-family CEOs. The study also reveals that non-family CEO managed companies tend to exhibit lower levels of EM compared to those led by family CEOs. These findings provide important insights for various stakeholders, from business owners to regulators and policymakers, in understanding and mitigating EM and TA practices in the Indonesian corporate landscape.

It elaborates on the complex dynamics between CG, CEO type, EM, and TA in Indonesian companies. The study reveals that CG quality has a significant impact on EM practices, mediated by TA strategies. This relationship is nuanced, differing between family and non-family CEO-led firms. In particular, family-led firms exhibit distinct patterns of EM, influenced by their governance structure. These findings offer a deeper understanding of the corporate behaviors in Indonesian family businesses, underscoring the importance of governance quality in shaping financial practices.

The paper’s contributions are significant in understanding corporate practices in Indonesian family businesses. It highlights the varying impacts of CG on TA and EM, depending on CEO type (family or non-family). This research offers valuable insights into the unique dynamics of family firms, particularly in emerging markets like Indonesia. The implications are vast for stakeholders, including business owners, investors, and policymakers. It underscores the need for tailored governance structures in family businesses and informs regulatory frameworks to mitigate undue financial practices.

The study contributes to the literature on CG in family businesses, offering a nuanced understanding of how leadership types affect financial strategies. It challenges and refines existing theories about governance and financial practices, especially in the context of emerging markets like Indonesia. This study also provides empirical evidence linking CEO type to financial management strategies, particularly in TA and EM. This evidence is crucial for understanding the real-world applications of theoretical frameworks in CG. As for practitioners, the study offers insights into the governance structures of family businesses, underscoring the need for balanced and effective management practices. It informs businesses, regulators, and investors about the implications of CEO types on corporate financial behaviors, potentially guiding policy-making and investment decisions.

In terms of limitations, the study focuses exclusively on Indonesia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or countries with different corporate governance and family business dynamics. By extending the number of countries and studying them for a longer time period greater accuracy of our results could be achieved. Regarding the dynamic business environment, the findings are based on data from a particular time frame. Rapid changes in the business environment, regulatory frameworks, and market conditions could affect the applicability of these results over time.

Future studies could investigate similar dynamics in different countries or regions to understand the universality of the findings. The other possible avenue for future research is to examine the internal dynamics of family companies more closely, including succession planning, family conflicts, and their impact on CG and financial practices.

Author contributions statement

Contributions of all authors, including:

Design of the work; analysis and or interpretation of data for the work.

Review the work critically for important intellectual content.

Final approval of the work to be published.

Accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Iskandar Itan, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Iskandar Itan

Dr. Iskandar Itan, a seasoned educator at Universitas Internasional Batam, earned his Doctorate in Business Administration from Universiti Sains Malaysia. His research interests include family firms, corporate governance, and earning management.

Zamri Ahmad

Dr. Zamri Ahmad, a senior faculty member at Universiti Sains Malaysia, holds a PhD in Finance and an MA in International Finance from the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne. His research is centered around market efficiency and behavioral finance.

Jaslin Setiana

Jaslin Setiana, currently in her final year at Universitas Internasional Batam, is eager in studying corporate governance and earning management.

Handoko Karjantoro

Prof. Handoko Karjantoro, who received his Doctorate in Business Administration from Nova Southeastern University, is deeply engaged in research areas covering corporate governance, financial accounting, and reporting.

References

- Abbadi, S. S., Hijazi, Q. F., & Al-Rahahleh, A. S. (2016). Corporate governance quality and earnings management: Evidence from Jordan. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 10(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v10i2.4

- Achleitner, A. K., Günther, N., Kaserer, C., & Siciliano, G. (2014). Real earnings management and accrual-based earnings management in family firms. European Accounting Review, 23(3), 431–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2014.895620

- Afonso Alves, C., Matias Gama, A. P., & Augusto, M. (2021). Family influence and firm performance: The mediating role of stewardship. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(2), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-01-2019-0015

- Aguilera, R. V., & Crespi-Cladera, R. (2016). Global corporate governance: On the relevance of firms’ ownership structure. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.10.003

- Ahmed, S., & Uddin, S. (2018). Toward a political economy of corporate governance change and stability in family business groups. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(8), 2192–2217. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2017-2833

- Al-Begali, S. A. A., & Phua, L. K. (2023). Accruals, real earnings management, and CEO demographic attributes in emerging markets: Does concentration of family ownership count? Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2239979

- Aleqab, M. M., & Ighnaim, M. M. (2021). The impact of board characteristics on earnings management. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 10(3), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.22495/jgrv10i3art1

- Ali, A., Chen, T., & Radhakrishnan, S. (2007). Corporate disclosures by family firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44(1–2), 238–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.01.006

- Al-Zaqeba, M. A. A., Hamid, A. S., Ineizeh, N. I., Hussein, O. J., & Albawwat, A. H. (2022). The effect of corporate governance mechanisms on earnings management in Malaysian manufacturing companies. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 12(5), 354–367. https://doi.org/10.55493/5002.v12i5.4490

- Amidjaya, P. G., & Widagdo, A. K. (2019). Sustainability reporting in Indonesian listed banks. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 21(2), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-09-2018-0149

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2004). Board composition: Balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 209–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/4131472

- Ansari, I. F., Goergen, M., & Mira, S. (2021). Earnings management around founder CEO reappointments and successions in family firms. European Financial Management, 27(5), 925–958. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12307

- Arieftiara, D., Utama, S., Wardhani, R., & Rahayu, N. (2019). Contingent fit between business strategies and environmental uncertainty. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(1), 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-05-2018-0338

- Armstrong, C. S., Guay, W. R., & Weber, J. P. (2010). The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2-3), 179–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.001

- Aronoff, C. E., & Ward, J. L. (1995). Family-owned businesses: A thing of the past or a model for the future? Family Business Review, 8(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1995.00121.x

- Attia, E. F., Ismail, T. H., & Mehafdi, M. (2022). Impact of board of directors attributes on real-based earnings management: Further evidence from Egypt. Future Business Journal, 8(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-022-00169-x

- Badan Pusat Statistik. (2021). Ekonomi Indonesia 2020 Turun sebesar 2,07 Persen (c-to-c). Bps.Go.Id

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Basco, R. (2013). The family’s effect on family firm performance: A model testing the demographic and essence approaches. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 4(1), 42–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2012.12.003

- Bennedsen, M., Lu, Y., & Mehrotra, V. (2022). A survey of Asian family business research*. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 51(1), 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajfs.12363

- Bergmann, N. (2023). Heterogeneity in family firm finance, accounting and tax policies: Dimensions, effects and implications for future research. Journal of Business Economics, 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-023-01164-6

- Boonlert-U-Thai, K., & Sen, P. K. (2019). Family ownership and earnings quality of Thai firms. Asian Review of Accounting, 27(1), 112–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-03-2018-0085

- Bosse, D. A., & Phillips, R. A. (2016). Agency theory and bounded self-interest. Academy of Management Review, 41(2), 276–297. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0420

- Brenes, E. R., Madrigal, K., & Requena, B. (2011). Corporate governance and family business performance. Journal of Business Research, 64(3), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.11.013

- Cascino, S., Pugliese, A., Mussolino, D., & Sansone, C. (2020). The influence of family ownership on the quality of accounting information. Family Business Review, 23(3), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486510374302

- Chen, R., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Wang, H., & Yang, Y. (2022). Corporate governance and tax avoidance: Evidence from U.S. cross-listing. The Accounting Review, 97(7), 49–78. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2019-0296

- Chen, S., Chen, X. I. A., & Cheng, Q. (2008). Do family firms provide more or less voluntary disclosure? Journal of Accounting Research, 46(3), 499–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2008.00288.x

- Chi, C. W., Hung, K., Cheng, H. W., & Tien Lieu, P. (2015). Family firms and earnings management in Taiwan: Influence of corporate governance. International Review of Economics & Finance, 36, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2014.11.009

- Daya Qarsa. (2022). Pembelian Menurun, Padahal Perusahaan Keluarga Pendorong Ekonomi Indonesia Dayaqarsa.Com.

- De Massis, A., Kotlar, J., Campopiano, G., & Cassia, L. (2013). Dispersion of family ownership and the performance of small-to-medium size private family firms. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 4(3), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2013.05.001

- Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225.

- del Carmen Briano-Turrent, G., & Poletti-Hughes, J. (2017). Corporate governance compliance of family and non-family listed firms in emerging markets: Evidence from Latin America. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(4), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2017.10.001

- Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2006). Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.02.002

- Ding, S., Qu, B., & Zhuang, Z. (2011). Accounting properties of Chinese family firms. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 26(4), 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X11409147

- Duygun, M., Guney, Y., & Moin, A. (2018). Dividend policy of Indonesian listed firms: The role of families and the state. Economic Modelling, 75, 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.07.007

- Efferin, S., & Hartono, M. S. (2015). Management control and leadership styles in family business. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 11(1), 130–159. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-08-2012-0074

- Efferin, S., & Hopper, T. (2007). Management control, culture and ethnicity in a Chinese Indonesian company. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(3), 223–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.03.009

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

- Eng, L. L., Fang, H., Tian, X., Yu, T. R., & Zhang, H. (2019). Financial crisis and real earnings management in family firms: A comparison between China and the United States. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 59, 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2018.12.008

- EY and University of St. Gallen Global Family Business Index. (2023). How the world’s largest family businesses are outstripping global economic growth. Familybusinessindex.

- Faisal, M., Utama, S., Sari, D., & Rosid, A. (2023). Languages and conforming tax avoidance: The roles of corruption and public governance. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2254017

- Feki Cherif, Z., Damak Ayadi, S., & Ben Hamad, S. B. (2020). The effect of family ownership on accrual-based and real activities based earnings management: Evidence from the French context. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems, 19(2), 283–310. https://doi.org/10.24818/jamis.2020.02004

- Gaaya, S., Lakhal, N., & Lakhal, F. (2017). Does family ownership reduce corporate tax avoidance? The moderating effect of audit quality. Managerial Auditing Journal, 32(7), 731–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-02-2017-1530

- Gellert, P. K. (2005). The shifting natures of “development”: Growth, crisis, and recovery in Indonesia’s forests. World Development, 33(8), 1345–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.03.004

- Gil, M., Uman, T., Hiebl, M. R. W., & Seifner, S. (2024). Auditing in family firms: Past trends and future research directions. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2023.2293908

- Githaiga, P. N., Kabete, P. M., & Bonareri, T. C. (2022). Board characteristics and earnings management. Does firm size matter? Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2088573

- Gottschalck, N., Rolan, L., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2023). The continuance commitment of family firm CEOs. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 14(4), 100568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2023.100568

- Guedrib, M., & Marouani, G. (2023). The interactive impact of tax avoidance and tax risk on the firm value: New evidence in the Tunisian context. Asian Review of Accounting, 31(2), 203–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-03-2022-0052

- Henry, E., & Sansing, R. (2018). Corporate tax avoidance: Data truncation and loss firms. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(3), 1042–1070. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-018-9448-0

- Hillier, D., Pindado, J., Queiroz, V. D., & C. D., La Torre. (2011). The impact of country-level corporate governance on research and development. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(1), 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.46

- Hunton, J. E., Libby, R., & Mazza, C. R. (2006). Financial reporting transparency and earnings management. The Accounting Review, 81(1), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2006.81.1.135

- Indriani, A. D., & Pujiono, P. (2021). Analysis of earnings management practices using the modified jones model on the industry company index kompas 100. The Indonesian Accounting Review, 11(2), 235. https://doi.org/10.14414/tiar.v11i2.2383

- Jarvis, D. S. L. (2012). The regulatory state in developing countries: Can it exist and do we want it? The case of the Indonesian power sector. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 42(3), 464–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2012.687633

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718812602

- Jin, K., Lee, J., & Hong, S. M. (2021). The dark side of managing for the long run: Examining when family firms create value. Sustainability, 13(7), 3776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073776

- Jiraporn, P., & DaDalt, P. J. (2009). Does founding family control affect earnings management? Applied Economics Letters, 16(2), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/17446540701720592

- Joko Pramono, A., Zulhawati, Z., Rusmin, R., & Wahyu Astami, E. (2022). Do family-controlled and financially healthy firms manage their reported earnings? Evidence from Indonesia. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 19(4), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.19(4).2022.17

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

- Kachaner, N., George Stalk, J., & Bloch, A. (2012). What you can learn from family business. Harvard Business Review.

- Kałdoński, M., & Jewartowski, T. (2020). Do firms using real earnings management care about taxes? Evidence from a high book-tax conformity country. Finance Research Letters, 35, 101351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.101351

- Kassim, A. A. M., Ishak, Z., & Manaf, N. A. A. (2013). Board effectiveness and company performance: Assessing the mediating role of capital structure decisions. International Journal of Business and Society, 14(2), 319–338.

- Keuangan, O. J. (2014). Roadmap Tata Kelola Perusahaan Indonesia (Vol. 84). Otoritas Jasa Keuangan.

- Kilincarslan, E. (2021). The influence of board independence on dividend policy in controlling agency problems in family firms. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 29(4), 552–582. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-03-2021-0056

- Kothari, S. P.,Leone, A. J., &Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accruals measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(2005), 163–197.

- Kristanti, F. T., Rahayu, S., & Huda, A. N. (2016). The determinant of financial distress on indonesian family firm. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.018

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. The Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00115

- Lee, C. H., & Bose, S. (2021). Do family firms engage in less tax avoidance than non-family firms? The corporate opacity perspective. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 17(2), 100263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2021.100263

- Leuz, C.,Nanda, D., &Wysocki, P. D. (2003). Earnings management and investor protection: an international comparison. Journal Financial Economics, 69(2003), 505–527.

- Li, O. Z., Liu, H., & Ni, C. (2017). Controlling shareholders’ incentive and corporate tax avoidance: A natural experiment in China. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 44(5–6), 697–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12243

- Lin, Y. H. (2017). Controlling controlling-minority shareholders: Corporate governance and leveraged corporate control. Columbia Business Law Review, 2, 453–510.

- Löhde, A. S. K., Campopiano, G., & Calabrò, A. (2020). Beyond agency and stewardship theory: Shareholder–manager relationships and governance structures in family firms. Management Decision, 59(2), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2018-0316

- Luan, C. J., Chen, Y. Y., Huang, H. Y., & Wang, K. S. (2018). CEO succession decision in family businesses – A corporate governance perspective. Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.03.003

- Mahrani, M., & Soewarno, N. (2018). The effect of good corporate governance mechanism and corporate social responsibility on financial performance with earnings management as mediating variable. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 3(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-06-2018-0008

- Martínez-Ferrero, J., Banerjee, S., & García-Sánchez, I. M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility as a strategic shield against costs of earnings management practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 305–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2399-x

- McNichols, M. F. (2000). Research design isss in earnings management studies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 19(2000), 313–345.

- Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., Lester, R. H., & Cannella, A. A. (2007). Are family firms really superior performers? Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(5), 829–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.03.004

- Minh Ha, N., Phuong Trang, T. T., & Vuong, P. M. (2022). Relationship between tax avoidance and institutional ownership over business cost of debt. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2026005

- Murni, S., Rahmawati, R., Widagdo, A. K., Sudaryono, E. A., & Setiawan, D. (2023). Effect of family control on earnings management: The role of leverage. Risks, 11(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11020028