?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This research aims to (1) build and predict a sustainable business model to support micro-business in developing its potential in facing the challenges of the dual transition era (digitalization and sustainability); (2) explore opportunities and challenges for sustainable business models in the creative craft, fashion, food and beverage industry sectors. This research used a mixed methods approach on 381 micro and small businesses in Indonesia, utilizing an explanatory sequential design. The study revealed that aligning internal resources with responsive strategies can form sustainable resilience strategies (SRS) that are reflected in survival, continuity, reorientation, and synergy. These SRS strategies significantly impact micro-businesses in meeting the challenges of adopting digital technology in their business operations. Moreover, to meet the challenges of a sustainable business model, micro-businesses must have a high orientation to achieving sustainable development goals first, then SRS can mediate them so that sustainable business practices are realized, which have a lasting impact on sustainable business performance. Overall, This study recommends that micro-businesses adopt a sustainable resilience strategy and campaign the SDG agenda through digital technology adoption. This research provides practical insights for micro-businesses in exploring sustainable business opportunities and challenges. It also benefits stakeholders such as industry, universities, science and technology parks as an integrated innovation platform, and the government in shaping policies and regulations related to digitalization and sustainability. Resilience has been previously studied as an input, process, or outcome. This study has discovered resilience as a sustainable strategy for micro-businesses, which is the novelty of this study.

Reviewing Editor:

SUBJECTS:

1. Introduction

Strategic management involves a series of decisions and actions made by managers to ensure the long-term success of an organization. It is crucial that the organizational goals are set in a way that can be used as a measure of the company’s performance (Wheelen et al., Citation2018). The process of strategic management confidently starts by thoroughly scanning and analyzing both the external environment, including the social and natural environments, as well as the company’s internal environment, such as assets, skills, and competencies. With this in-depth understanding, the strategy is formulated and implemented with confidence, after which, evaluation and control are carried out to ensure that the strategy achieves its intended goals (Wheelen et al., Citation2018). In addition, other strategic thinking models also focus on a holistic and integrated view of business by developing a long-term vision that involves considerations of company culture, reputation, competence, and resources (McGee, Citation2005). Strategic management theory is closely related to various scientific disciplines. In this research, strategic management theory is linked in the context of entrepreneurship, which does not only mean business creation, but more than that, entrepreneurship includes the process of seeking opportunities, taking risks, and tenacity in pushing ideas into reality (Kuratko, Citation2011). This research also refers to the opportunity-based entrepreneurship theory supported by Peter Drucker and Howard Stevenson (Simpeh, Citation2011) which states that entrepreneurs always look for change, respond, and exploit it as an opportunity (Drucker, Citation1985). This theory suggests that entrepreneurs do not cause changes but instead take advantage of opportunities created by changes, such as technological advancements and shifts in consumer preferences, so that the opportunities that arise become a source of innovation that can generate demand. Another finding confirms that opportunity-based entrepreneurship is essential for environmental quality in sustainable development (He et al., Citation2020).

Sustainability is about protecting the environment and ensuring the well-being of humanity and the economy. The 3Ps of sustainability, namely people, planet, and profit, also known as the triple bottom line (Heizer et al., Citation2018; Krajewsky et al., Citation2013), have evolved into the 5Ps, including people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership (United Nations, Citation2015). Sustainable entrepreneurship is a powerful tool that can help us preserve nature, support communities, and create a better future for all. We can build a more sustainable and prosperous world by pursuing innovative solutions that benefit both individuals and society (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Over the past decade, business people have been confronted with sustainability challenges and the direct impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the last four years. As a result, traditional business processes have been limited while digitalization has accelerated rapidly (Roman and Rusu, Citation2022). Many research studies have highlighted the benefits and challenges of digitalizing micro small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Digital technology, for example, can provide economic and social advantages by improving both internal and external communications (Zhen et al., Citation2022).

In the past decade, business people have been facing a dual transition era that encompasses two major challenges - digitalization and sustainability, where the digital technology has become a crucial aspect of almost all areas of business operations, meanwhile, achieving the sustainable development goals (SDG) has also become a shared responsibility and a significant challenge for companies. This phenomenon is also experienced by micro-business actors in Indonesia. In Indonesia, Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) are part of the manufacturing industry which is known for its labor-intensive nature and minimal capital. Apart from contributing to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), it also acts as a safety net for businesses affected by the financial and economic crisis. According to the classification of businesses by the Indonesian Central Statistics Agency, micro businesses are those with a workforce of 1-4 employees, while small businesses have a workforce of 5-19 employees (Indonesian Central Statistics Agency, Citation2020).

After reviewing the literature and examining the empirical conditions of micro-businesses in Indonesia, this research has two primary objectives. Firstly, to formulate a sustainable business performance model that can help micro-businesses survive during the dual transition period and continue to thrive sustainably in the future and examine the interrelationships that exist between the variables in the model. Secondly, explore the opportunities & challenges faced by micro-businesses in facing the dual transition era. To achieve these objectives, the research will address two key research questions. The first research question (RQ1) aims to explore the business strategies that are appropriate for Indonesian business people to implement when facing the dual transition era. The second research question (RQ2) focuses on how the adoption of digital technology can improve sustainable business performance. Overall, this research is significant as it seeks to provide valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities faced by micro-businesses in the dual transition era. By identifying the appropriate strategies and exploring the potential of digital technology, the research aims to help micro-businesses in Indonesia to adapt and thrive in the changing business landscape while contributing to sustainable development.

2. Literature review, hypotheses development, and conceptual model

2.1. Sustainable resilience strategy (SRS)

The term ‘resilience’ is commonly used in a variety of fields such as business, economics, politics, engineering and basic science (Norris et al., Citation2008). According to research, resilience is an interdisciplinary concept that encompasses three key elements: 1. Bouncing back from a shock: This refers to a system’s ability to return to its original state or path after experiencing a disturbance (Martin and Sunley, Citation2015); 2. Ability to absorb shocks: This element highlights how much disturbance a system can withstand before moving to a new state (Hartmann et al., Citation2022; Martin and Sunley, Citation2015); 3. Positive adaptation: This refers to a system’s capacity to maintain its core performance despite shocks or disruptions (Hartmann et al., Citation2022; Martin and Sunley, Citation2015). In relation to the topic of entrepreneurship, it is confirmed that the resilience of entrepreneurs is influenced by two main factors: psychological function (emotional, cognitive, previous experience of difficulties, social), which is called psychological resilience in entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial action factors (Ahmed et al., Citation2022). This applies not only to individuals but also business units. Psychological functioning is a crucial pathway between entrepreneurship and subjective well-being (Nikolaev et al., Citation2020), while entrepreneurial action factors demonstrate an interdependent relationship where resilience is both an antecedent and a consequence of entrepreneurial action (Shepherd et al., Citation2020). Resilience outcomes include proactive problem-solving abilities, a sense of moral purpose, self-reliance, realistic optimism, and a sense of belonging to a diverse community. Interestingly, these outcomes are important inputs for enhancing resilience and entrepreneurial action (Shepherd et al., Citation2020).

Several previous studies have explored resilience as an input, process, or outcome. Meanwhile, in this research, resilience is a strategy, based on strategic management Wheelen et al. (Citation2018) as an underpinning theory. Regarding the issue of sustainability, micro and small business players can strive to obtain high customer value through efficient and sustainable ways. They can adjust the potential resilience of tangible and intangible resources with the choice of business operations strategies that can generate competitive advantage (Alberti et al., Citation2018; Heizer et al., Citation2020), including differentiation, low costs, and responsiveness (Heizer et al., Citation2020). Business actors can implement several combinations of these strategies (Heizer et al., Citation2020). Other findings state that using ingenuity and choosing the right company strategy to overcome new opportunities and obstacles arising from the COVID-19 pandemic shows that Indonesian micro and small business are proven to survive, be sustainable, and grow significantly (Purnomo et al., Citation2021).

Based on the literature references above, researchers formulated Sustainable Resilience Strategy (SRS) for micro and small business players by aligning the resilience of tangible/intangible internal resources with responsive strategies (Alberti et al., Citation2018; Heizer et al., Citation2020) to create high customer value in an efficient and sustainable. The four dimensions of sustainable resilience strategies are: (1) survival, it involves finding creative ways to deal with crises that may arise (Branicki et al., Citation2018); (2) continuity, involves seeking connectivity with market conditions and access to resources (Branicki et al., Citation2018); (3) re-orientation, it involves reviewing attitudes and decision-making in response to changes that may occur, such as changes in macro-environmental demands, social, economic, technological changes, changes in government policy, or changes in market preferences (Branicki et al., Citation2018); and (4) synergy, it involves developing synergy capabilities with stakeholders in dealing with crises (Alberti et al., Citation2018).

2.2. Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation (EO), entrepreneurial competence (EC), and SRS

Resilience refers to the ability to maintain good mental and emotional health even after experiencing trauma or loss (Corner et al., Citation2017). It’s important to note that resilience is not only crucial for individuals, but also for small businesses, organizations, and ecosystems to respond effectively to unexpected negative events (Corner et al., Citation2017, Roundy et al., Citation2017; Gianiodis et al., Citation2022;). While many studies have focused on the economic resources required for entrepreneurship, very few have emphasized the importance of psychological functions when responding to adversity (Nikolaev et al., Citation2020). Based on existing literature, the author has integrated psychological aspects into the framework of entrepreneurial activities, particularly those associated with entrepreneurial orientation and competence. These two factors play a critical role in developing strategies for entrepreneurial resilience, encompassing a wide range of psychological traits such as independence, risk-taking, proactiveness, innovation, and competitiveness. Moreover, entrepreneurial competence is also linked with psychological factors such as the ability to establish relationships, commitment, organizational skills, and other relevant areas.

EO encompasses a set of practices, processes, and decision-making activities to enter new markets, whether it is in a completely new market or an established market with a new product (Lumpkin and Dess, Citation1996), becoming a new entrant is a significant accomplishment. EO encompasses five primary dimensions, including acting independently, being willing to innovate, taking risks, being aggressive towards competitors, and having a proactive approach towards market opportunities (Lumpkin and Dess, Citation1996). Empirical evidence has demonstrated the ability of EO to mobilize the resilience of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), especially during times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. EO achieves this by striking a balance between short-term operational actions and long-term strategic thinking, resulting in a more resilient MSME (Zighan et al., Citation2022). The dimensions of innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness in EO can help MSMEs adapt to dynamic environmental changes (Branicki et al., Citation2018), making them better prepared to face significant disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Zighan et al., Citation2022). EO has also been proven to contribute to business model innovation performance and product development capabilities (Ferreras-Méndez et al., Citation2021), making it an essential strategic orientation. EO has a positive impact on the resilience of Small and Medium-sized Enterprise (SME) supply chains through the dimensions of innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness (Al-Hakimi and Borade, Citation2020). Simultaneously, EO also has a positive and significant impact on SME supply chain resilience (Al-Hakimi et al., Citation2022). In conclusion, EO plays a vital role in helping MSMEs become more adaptive, innovative, and better equipped to address sustainability issues by providing unique and desirable business solutions (Nuseir and Aljumah, Citation2022). It is a strategic orientation that enables MSMEs to achieve long-term success by balancing short-term and long-term objectives and adapting to dynamic environmental changes while maintaining a competitive edge.

In 2000, Man & Lau proposed a theoretical framework for EC that aimed to identify the competency areas required for successful entrepreneurship in MSMEs. They categorized various entrepreneurial behaviors into six competency areas, namely opportunity, conceptual, relationship, organizing, strategic, and commitment competence (Man and Lau, Citation2000). Competence is the ability to utilize knowledge and skills to achieve compelling and extraordinary performance (Boyatzis et al., Citation2002). For entrepreneurial competence, which includes searching for opportunities, conceptualizing business ideas, and taking risks to bring them to fruition (Kuratko, Citation2011), authors operationalize entrepreneurial competence into six dimensions as in the theoretical framework of Man & Lau (Citation2000). According to empirical evidence from Italy, intellectual capital, which includes human capital, organizational capital, and relational capital, has a strong correlation with the resilience of MSMEs (Agostini and Nosella, Citation2022). Organizational capital and relational capital are similar to organizational competence and relational competence, respectively, as part of the entrepreneurship competency dimension. Moreover, apart from building the resilience of MSMEs, entrepreneurial competence is also essential for MSMEs to achieve maximum benefits while implementing e-commerce (Hussain et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the six dimensions of entrepreneurial competence defined by Man & Lau (Citation2000) are crucial for MSMEs to succeed in the competitive e-commerce landscape. This theoretical framework can help entrepreneurs to develop their competencies in these areas and enhance their chances of success in their business ventures. Based on a literature review related to EO, EC, and SRS, the authors proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: EO has a direct effect on SRS.

Hypothesis 2: EC has a direct effect on SRS.

2.3. Sustainable entrepreneurship practices (SEPRAC)

The basis for implementing sustainability practices requires a company management system that provides functional efficiency and sub-system effectiveness by considering the principles of sustainable performance (Ciemleja and Lace, Citation2011). In 2011, Shepherd & Patzelt introduced the idea of sustainable entrepreneurship, based on a thorough analysis of sustainable development and entrepreneurship literature. Their model defines sustainable entrepreneurship as a form of entrepreneurial pursuit that prioritizes the conservation of nature, the betterment of communities, and the creation of innovative products, services, and processes that deliver both economic and non-economic advantages to individuals, the economy, and society as a whole (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). In operational definition, Shepherd & Patzelt (Citation2011) divides sustainable entrepreneurship as an entrepreneurial activity that carries out two constructs simultaneously, namely: ‘which must be sustainable’ and ‘which must be developed’. Things that must be sustainable or preserved are nature, life support sources, and communities. In contrast, things that must be developed are economic gain, non-economic gain to individuals, non-economic gain to society (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Schaltegger & Wagner construct sustainable entrepreneurship as an entrepreneurial activity that includes ecopreneurship, social entrepreneurship, and institutional entrepreneurship. Ecopreneurship is an entrepreneurial activity that focuses on providing solutions to conditions of environmental degradation caused by market failure through the creation of economic value (Dean and McMullen, Citation2007), so the primary goal of ecopreneurship is to make money by solving environmental problems (Schaltegger and Wagner, Citation2011). Social entrepreneurship (SE) is conceptualized as an entrepreneurial activity that contributes to solving social problems and creating value for society. The main goal of SE is to achieve social goals and secure funds to achieve this. In other words, SE mainly focuses on solving social problems and integrating them into economic issues (Schaltegger and Wagner, Citation2011). Institutional entrepreneurship has a core motivation to contribute to changes in regulations, social institutions, and markets (Schaltegger and Wagner, Citation2011), so the biggest challenge for organizations is changing institutions to integrate them into sustainability issues. In line with this construction is entrepreneurial practices related to ecopreneurship, social ecopreneurship, and institutional entrepreneurship at University in Malaysia, which can be supported by the effective implementation of lean higher education so that it has implications for the sustainability of higher education (Nawanir et al., Citation2019).

2.4. Relationship between SDG-challenges orientation (SDGCO), SRS, and SEPRAC

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are integral to the global economy. However, their business practices are often unsustainable and contribute significantly to worldwide environmental degradation and social impacts (Ahmed et al., Citation2018). The concept of sustainability has evolved from the 3Ps (people, profit, and planet) (Heizer et al., Citation2020; Krajewsky et al., Citation2013) to the 5Ps (people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership) (United Nations, Citation2015). The 2030 Agenda of the SDGs aims to promote collaboration and partnership within a country to achieve 17 SDGs, including the 5 P. Sustainability orientation is the belief in integrating social and environmental considerations into business operations, indicating an organization’s readiness to adopt sustainability-based initiatives (Horak et al., Citation2018). It includes awareness, confidence, and intelligence regarding initiatives for social, environmental, and economic progress (Horak et al., Citation2018), as well as law and governance (The Ministry of National Development Planning, Citation2020). Researchers have proposed four SDGCO dimensions, namely social pillar orientation (SDG_SO), environmental pillar orientation (SDG_ENO), economic pillar orientation (SDG_ECO), law, and governance pillar orientation (SDG_LGO) (Horak et al., Citation2018; The Ministry of National Development Planning, Citation2020). Sustainability is a fundamental principle that emphasizes the significance of our actions today not hindering the range of economic, social, and environmental choices that will be available for future generations (Elkington, Citation1997; Heizer et al., Citation2020; Krajewsky et al., Citation2013; Labuschagne et al., Citation2005). Decision-makers need to manage resources not only at present but also over time to build robust system resilience to overcome the uncertainties of the future (Bansal and DesJardine, Citation2014).

According to Kuckertz & Wagner (Citation2010), sustainability orientation refers to the underlying attitudes and beliefs that a person holds towards environmental protection and social responsibility. It helps to determine whether an individual intends to start a business with a sustainability-oriented approach (Kuckertz and Wagner, Citation2010). Similarly, Parrish’s Citation2010 perspective supports the idea that companies require a specific orientation to maintain a balance between the economy, environment, and social dimensions. In other words, firms need to focus on not only financial gains but also on the impact of their actions on the environment and society (Parrish, Citation2010). Other researchers have discovered that sustainability orientation and entrepreneurial orientation positively impact sustainable entrepreneurship. Additionally, entrepreneurial knowledge has a significant moderating influence (Hanan et al., Citation2021). To achieve sustainability, organizations need a sustainability orientation and a comprehensive focus on achievements from all individuals and organizations (Karkoulian et al., Citation2016). Further findings suggest that the concept of sustainability needs to be campaigned to increase awareness and understanding of protective measures for the community. Policies for implementing sustainable practices for members of the company’s supply chain (Saqib and Zhang, Citation2021) are vital in this regard. Orientation and understanding of company systems and procedures, particularly those related to environmentally friendly practices and responsibility towards stakeholders, such as the community, customers, business partners, employees, and suppliers, are critical. To improve sustainable entrepreneurship practices in MSMEs, it is essential to increase awareness and understanding of these factors (Ahmad et al., Citation2020). In conclusion, sustainability is a complex and multi-dimensional concept that is not limited to environmental protection but also includes social and economic development. Sustainable development requires a comprehensive approach that integrates social, environmental, and economic considerations, as well as law and governance. Achieving sustainability will depend on the readiness of organizations to adopt sustainability-based initiatives and the focus on achievements from all individuals and organizations. Based on the SDGCO, SRS, and SEPRAC literature review, the author proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: SDGCO has a direct influence on SRS.

Hypothesis 4: SDGCO has a direct influence on SEPRAC.

2.5. Relationship between digital technology adoption (DTA), SRS, and SEPRAC

Digital technology adoption means using digital technology in business that can benefit business model development, income-generating opportunities, and new value (Urdu et al., Citation2019). MSME players can adopt digital technology to increase competitiveness, including by fulfilling digitalization prerequisites such as the internet and its devices (Urdu et al., Citation2019), as well as embracing it in business operations such as in consumer service processes, production, marketing, sales, and supply chain management (Al-Allak, Citation2010; Jha et al., Citation2022; Lang et al., Citation2022; Ristyawan, Citation2020; Sharma et al., Citation2022; Tamvada et al., Citation2022;). Digital business model innovation has been proven to strengthen competitiveness and support business sustainability (Ahmad et al., Citation2022). Previous research findings illustrate how digitalization can improve entrepreneurial resilience by adopting a systematic approach to identify and describe digital behaviors, actions, and strategies that can assist businesses to transform during the COVID-19 pandemic. It enables entrepreneurs to make informed decisions regarding digital tools, platforms, and infrastructure that they can utilize to optimize their business units despite the limited resources and uncertainties presented by the pandemic (Santos et al., Citation2023). Employing digital technologies to enhance strategic and operational resilience can facilitate responding to adversity, but this requires having competent and digitally literate employees and executives, investing in digital technologies and building organizational capabilities (Santos et al., Citation2023).

Many studies examine forms of digital technology adoption and their implications for business and sustainability, including the use of e-commerce for the development of SMEs in many countries, because of its ability to reduce operational costs to improve company performance (Nasution et al., Citation2021); the use of AI-CRM as a form of technology adoption that has a positive impact on the dynamic capabilities of family businesses, which has implications for the sustainability of family businesses during the crisis (Chaudhuri et al., Citation2023); Big data analysis capability has an indirect impact on sustainable competitive advantage (Behl et al., Citation2022). In today’s business world, companies are facing challenges related to internationalization, digitalization, and sustainability. These three factors are crucial for the growth of any organization. However, when companies decide to expand their operations globally, digitalization and sustainability can sometimes become competitors instead of being complementar (Denicolai et al., Citation2021). Previous studies have produced inconsistent evidence regarding the relationship between digital technology adoption and sustainable business strategy. Some findings reveal that the strategy established in the new normal post-pandemic conditions is reflected in the scope of successful implementation of advanced technology (Akpan et al., Citation2022). Some find that adopting digital technology has not directly shown positive results on business resilience (Yawiseda et al., Citation2022), but there are also those who find that digitalization influences business resilience (Santos et al., Citation2023). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a strong correlation between internet/e-business adoption, online marketing, and the sustainability of Indonesian MSMEs (Patma et al., Citation2021). However, this digital transformation is a challenging task for Indonesian MSMEs. This unpreparedness is shown in Indonesia’s 2020 Digital Competitiveness Index (DCI) ranking, which is in 56th position out of 63 countries (Najib, Citation2022).

Resilience often leads to re-engagement in entrepreneurship after a business failure. It allows individuals to learn from their mistakes and make informed decisions in their next venture (Williams et al., Citation2020). Resilience, a psychological trait that enables one to endure and recover from adversity, is a critical component for entrepreneurs looking to grow and transform their institutions in the face of extreme conditions (Cascio and Luthans, Citation2014). Within the family business context, the display of resilience by entrepreneurs can create a positive impact on future generations of entrepreneurs, by promoting transgenerational entrepreneurship and shaping the strategic direction of their successors (Jaskiewicz et al., Citation2015). The relationship between DTA and sustainability is interesting to study further in the context of MSEs. For this reason, based on the stages in the strategic management theory of Wheelen et al. (Citation2018), researchers directly through hypothesis drawing as follows:

Hypothesis 5: SRS has a direct effect on DTA.

Hypothesis 6: SRS has a direct effect on SEPRAC.

Hypothesis 8: DTA has a direct effect on SEPRAC.

2.6. Relationship between DTA, SRS, SEPRAC, and sustainable business performance (SBPERF)

Company performance is the end outcome of a company’s actions and operations (Wheelen et al., Citation2018). The measurement of corporate performance has progressed from solely concentrating on economic profit to considering both economic and non-economic gains as long as they are tied to sustainability concerns (Le, Citation2022; Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Sustainable entrepreneurial performance takes into account the economic impacts of entrepreneurial activities on individuals, companies, and society, while also considering non-economic sustainability outcomes (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Previous research confirms that the performance of MSEs in emerging countries can be influenced by the level of entrepreeneurial orientation, digital technology adoption, and innovation capability (Fang et al., Citation2022). Technology adoption will help close the productivity gap between micro and small business, with large corporations by increasing capacity and capability for greater competitiveness and innovation (Abu Hasan et al., Citation2022). Using simple digital technologies and focusing solely on sales can help micro-businesses improve their performance and create more value, thus leading to increased employment opportunities. However, implementing complex digital technologies that come with higher costs can have a short-term negative impact on the performance of micro-businesses (Roman and Rusu, Citation2022). Extensive research has demonstrated that the adoption of e-commerce is essential for the growth and development of micro-businesses in many countries. Utilization of e-commerce platforms not only enables efficient transactions and agreements with customers but also reduces operational costs significantly. This, in turn, leads to improved performance and competitiveness in the market (Nasution et al., Citation2021).

On the other hand, resilience refers to the capacity of an individual to bounce back and recover from setbacks, failures, or adverse situations, and move forward with renewed energy. When entrepreneurs exhibit resilience, they are more likely to succeed in future business ventures (Williams et al., Citation2020). This is especially important in family businesses, where resilience can be passed down to future generations and shape the company’s strategic direction (Jaskiewicz et al., Citation2015). Institutional entrepreneurs who exhibit resilience are better equipped to drive change and transform institutions, even in extreme conditions (Cascio and Luthans, Citation2014). Another research finding states strong personal resilience can effectively enhance employee-level resilience and business performance (Santoro et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, it is confirmed that sustainable practices can have a significant impact on a company’s sustainability performance (Saqib and Zhang, Citation2021). In the context of supply chain management as part of business operations, it is also confirmed that circular economy practices are very important in encouraging sustainable supply chain management to achieve sustainable performance (Le, Citation2022). The sustainable practices in manufacturing, procurement, and distribution have a significant effect on a company’s sustainability performance, and this connection is moderated by supply chain visibility (Saqib and Zhang, Citation2021). Based on the literature review, the authors proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: SRS has a direct effect on SBPERF.

Hypothesis 9: DTA has a direct effect on SBPREF.

Hypothesis 10: SEPRAC has a direct effect on SBPERF.

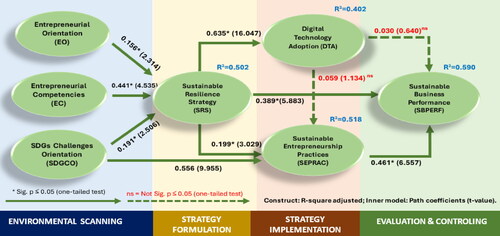

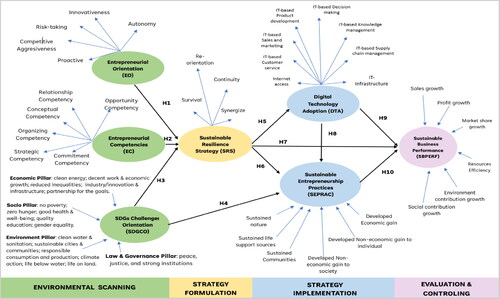

Based on the literature review and proposed hypotheses, the author describes a conceptual model based on the strategic management theory of Wheelen et al. (Citation2018), as in .

Figure 1. Conceptual Model with underpinning theory ‘Strategic Management Theory’ (Wheelen et al., Citation2018).

3. Research method

This research took samples from 401 MSMEs on Java and Sumatra as units of analysis using non-probability sampling techniques with voluntary response design in data collection. The research instrument was an online questionnaire distributed cross-sectionally for three months (May–July 2023). The data collection process was facilitated by centralized MSME managers from various organizations, such as the Bandung City Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Bandung Regency MSME Chair, the national MSME mentoring agency, MSME business development consultants, and business incubator managers from two private campuses in the cities of Bandung and Jakarta. After undergoing a filtering process, 381 data were suitable for processing. This number meets the minimum sample size requirement of 166 data. The minimum sample size = 166 is based on calculation results using G*Power for the number of predictors = 9, effect size (f2) = 0.15, and statistical power 95%. The minimum sample requirement calculated based on ten times rules for the path with the largest formative indicator in the model is 60 data. In comparison, with ten times rules, the model’s largest number of structural paths is 90 data. All three calculations of the minimum requirements in this research have been met. In fact, the amount of data obtained has exceeded the minimum sample integrity.

This research follows a mixed methods approach with an explanatory sequential design. The first stage involves a quantitative approach, which is followed by a qualitative approach to clarify unique or unpredictable early-stage findings (Creswell and Clark, Citation2018). In stage 1, the author uses exploratory quantitative research analysis to adapt to the circumstances and research needs for model building, prediction, empirical explanation, and less theory on the topic (Hair et al., Citation2017). Additionally, the author employs VB-SEM analysis in quantitative data analysis to cater to the research needs and circumstances, such as predicting the key target construct or identifying the critical driver, exploring or extending an existing structural theory, formulating indicators measured constructs as a part of the structural model, and handling complex structural models with many constructs and indicators (Hair et al., Citation2011). The data has been analyzed using descriptive statistical analysis and inferential statistics with VB-SEM Analysis using SmartPLS4. The VB-SEM Analysis journey begins by preparing measurement models, both formative and reflective indicators measurement. To ensure accurate results, common method variance (CMV) measurements are taken through procedural remedies at the start of preparing the instrument, followed by statistical remedies using full collinearity testing and marker variable testing. The next step involves structural measurement, starting from collinearity measurements, structural path coefficients analysis, deterministic coefficients analysis, effect size analysis, and PLS-Predict analysis.

After obtaining several findings from stage 1, which required detailed explanations to achieve the research objectives, the author continued stage 2 of the research. This involved three different types of interviews (Creswell and Creswell, Citation2018). Firstly, the author conducted face-to-face interviews by visiting the Bandung Technopark (BTP) located in Dayeuhkolot, Bandung Regency, Indonesia. During these interviews, the author spoke with the Manager of Innovation and Business Incubation (IIB) along with their team. The author also conducted face-to-face interviews with micro and small business coordinators in Bandung Regency. Secondly, the author conducted a focus group discussion with three startup owners who had successfully been fostered in the BTP Science and Technology Park. Lastly, the author also conducted telephone interviews with several micro and small business actors. The purpose of these interviews was to obtain explanations regarding several phase 1 research findings. Research objects were entrepreneurial competencies (EC), entrepreneurial orientation (EO), sustainable development goals orientation (SDGCO), sustainable resilience strategy (SRS), digital technology adoption (DTA), sustainable entrepreneurial practices (SEPRAC), and sustainable business performances (SBPERF). presents operationalization variables from the seven research objects in this study.

Table 1. Variable Operationalization.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Results

The study focuses on micro, small, and medium enterprises located on the islands of Java and Sumatra. displays the demographic data of the 381 MSMEs that were sampled. Based on the data collected from the study, 88% of the businesses that participated were micro-scale, 11% were small-scale, and only 1% were medium-scale (Indonesian Central Statistics Agency, Citation2020). Therefore, the findings of this research are mainly applicable to micro-businesses in Indonesia. showcases the different types of businesses that were sampled, which operated in the craft, fashion, food and beverage sectors, both production and trade. In Indonesia, these three types of businesses fall under 17 sectors of creative industries (Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy Data and Data Center Preparation Team, Citation2020). Judging by the demographic data of the business actors that were sampled in this research, it can be confirmed that the empirical findings are focused on the micro-scale sectors of craft, fashion, and food and beverage in the creative industry.

Table 2. Demographic profile.

4.1.1. Descriptive analysis and data normality

Based on the information presented in , it can be concluded that all the manifest variables used in this study have skewness and kurtosis values within the threshold limits of -2 ≤ skewness ≤ 2 and -7 ≤ kurtosis ≤ 7 (Curran et al., Citation1996; West et al., Citation1995), indicating that the data is normally distributed.

Table 3. Descriptive and Normality Statistics.

4.1.2. Measurement model assessment

4.1.2.1. Formative indicators

Measuring the quality of formative indicators can be done through three stages: redundancy analysis measurement, collinearity assessment, and significance & and relevance measurement.

Redundancy analysis, using global measurement items that summarize the essence of the construct to be measured by the formative indicators. The threshold used refers to a construct that is measured formatively which can explain at least 50% of the variance of the items measured reflectively, namely a path coefficient >0.708 (Hair et al., Citation2018). The results of the redundancy analysis measurement of the three observed variables in the model show that the path coefficient SDGCO = 0.791, SEPRAC = 0.793, and SBPERF = 0.833. The path coefficient of each item towards the global item had met the threshold, namely >0.708, so the proposed formative indicator could measure the construct in the model (Hair et al., Citation2018).

4.1.2.1.1. Collinearity assessment

Collinearity will occur if there is a strong relationship between formative indicators, proving a problem in the research methodology. Measuring collinearity can use the variance inflation factor (VIF) value. VIF is expressed as the inverse of Tolerance (i.e. VIF =1/TOL). The thresholds are Tolerance <0.20 or VIF >5, which indicates potential collinearity problems (Hair et al., Citation2011), or Tolerance <0.30 or VIF >3.3, which indicates potential collinearity problems (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, Citation2006). The collinearity testing is presented in . The VIF value of the outer model is <5, so there is no collinearity in the formative indicators for all latent constructs (Hair et al., Citation2011). Therefore, researchers proceed to the next measurement stage: significance and relevance.

Table 4. Construct Validity of Formative Indicators: Redundancy analysis, Collinearity assessment, and Significance & relevance assessment.

4.1.2.1.2. Significance and relevance assessment

The test results are presented in . Seven items: SDGLGO, SLSS, SCOM, DNEI, SG, PG, and RE are insignificant. However, these seven items cannot be directly interpreted as poor quality indicators. Hair et al. (Citation2017) state that if this happens, researchers must consider the amount of outer loading on the indicator. If the outer loading is >0.5, the insignificant indicator can be maintained in the model (Hair et al., Citation2017). For this reason, the author justifies that the seven indicators are still included in the model because each has a high outer loading value (>0.7).

4.1.2.2. Reflective indicators

To evaluate variable measurement models with reflective indicators using Variance Based-Structural Equation Model (VB-SEM) (Hair et al., Citation2017), the authors follow these guidelines: (1) Maintain indicators with outer loading ≥0.708. Remove indicators in the 0.4 ≤ outer_loading < 0.70 range only if the deletion increases Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) above recommended thresholds. Delete indicators with outer loading <0.4; (2) CR >0.60 is reliable, and >0.70 is a general guideline for internal consistency reliability; (3) AVE ≥0.50 indicates convergent validity. Delete the item with the lowest outer loading if AVE <0.50. The results of measuring reflective indicators in this study are presented in . (4). Use Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) to assess discriminant validity in PLS-SEM. HTMT0.85 indicates a lack of discriminant validity for conceptually different variables, and HTMT0.90 indicates a lack of discriminant validity for conceptually similar variables. Cross-loading should be greater than cross-loading with other constructs, and the Fornell-Larcker Criterion should be higher than the highest correlation with other constructs. The results of discriminant reliability measurements in this study are presented in .

Table 5. Indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, and convergent validity of reflective indicators.

Table 6. Discriminant validity: Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) Statistics.

Table 7. Discriminant validity: Fornell and Larcker Criterion.

Based on , The outer loading values for all indicators are satisfactory (87% are >0.708, 13% are in the range 0.4 ≤ outer loading ≤ 0.708), the rho_c values for all constructs are >0.7, and the AVE values for all constructs are ≥0.5. Furthermore, the HTMT value is <0.85, and the Fornell and Larcker values all meet the threshold. The measurements above confirm that the constructs in the model are valid and reliable (Hair et al., Citation2017).

4.1.3. Common method variance measurement

Problems that can cause systematic errors start from the common method variance (CMV), which is caused by bias in the use of methods when conducting research, such as research media coverage, research conditioning, location, research instruments, time, procedures used in measurement, and data sources (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). In particular, this ‘bias’ can be caused by (i) the use of the same measurement method when measuring the construct, which often occurs in survey research; (ii) the use of a single informant data source (Malhotra et al., Citation2017; Podsakoff et al., Citation2003; Citation2012); (iii) as well as the presence of several false correlations between variables, which can lead to wrong conclusions about the relationship between variables by inflating or deflating the findings. The researcher collected data from a single source for one questionnaire to measure the seven observed variables during the research. To prove that there was no common method variance in the data collected, the researcher carried out CMV testing using procedural and statistical remedies as follows:

Procedural remedy, as follows (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012): (i) The research instrument uses a different scale for each variable, namely the EO, EC, SDGCO, SRS, DTA, and SEPRAC variables using a numerical scale that is often treated as an interval scale (Sekaran and Bougie, Citation2016) and the SBPERF variable uses a ratio scale, and uses a seven-point scale for exogenous variables (EO, EC, and SDGCO) and a five-point scale for endogenous variables (SRS, DTA, SEPRAC, and SBPERF); (ii) The researcher has ensured the confidentiality of the respondents; (iii) The research instrument uses scale items that are written clearly and precisely so that they are not too biased; (iv) The researcher has informed that there is no preferred or correct answer. What is needed is an honest answer according to the situation and conditions experienced/perceived by the respondent; (v) The researcher has provided clear answering instructions in the instrument; (vi) Researchers have avoided unclear concepts and simplified complex questions; (vii) The researcher has tried to make language, vocabulary, and syntax simple and appropriate to the respondent’s reading ability; and (viii) The research instrument is free from double barrel questions.

Statistical remedies are as follows: (i) full collinearity testing. The steps are to create a dummy variable, set the dummy variable as an endogenous variable, connect all research variables to the dummy variable, and carry out collinearity testing. Threshold: if the VIF value <10 (Chin, Citation1998; Henseler et al., Citation2009), or VIF < 5 (Hair et al., Citation2011), or VIF < 3.3 (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, Citation2006), then it is stated that there is no collinearity. The results of full collinearity testing are presented in .

Table 8. Statistical remedy: full collinearity testing.

Marker variables MUST be highly reliable. Marker variables are theoretically unrelated to the endogenous variables under study. In the test, the marker variable must lead to all endogenous variables (Miller and Simmering, Citation2022). The steps connect all the variables involved in the research except the marker variable. Pay attention to the R-square value. Then, enter the marker variable into the model. Associate the marker variable with all endogenous variables. Pay attention to the R-square value. The relationship between the marker and endogenous variables should not be significant. In other words, the R-square should not increase significantly. If the relationship is significant and the R-square rises by 10%, then it is inevitable that CMV has occurred in the research model. confirms the adjusted R2 value before and after the marker variable is entered into the model shows the adjusted R2 increases <10%, indicating CMV does not exist in the model (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012).

Table 9. R2-adjusted increases percentage.

4.1.4. Structural model assessment

The steps for assessing a structural model are checking for collinearity, evaluating the size and significance of structural path relationships, assessing R2, checking the effect size f2, and evaluating predictive relevance based on Q2 (Hair et al., Citation2014).

4.1.4.1. Collinearity assessment

The Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) value is a reliable measure of collinearity. To be considered free from collinearity, the recommended VIF value is <10 (Chin, Citation1998; Henseler et al., Citation2009). Hair et al. suggests a VIF value <5 (Hair et al., Citation2011), or a VIF value <3.3 (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, Citation2006). Based on the Collinearity Statistics values in , all VIF values are <10, <5, or <3.3. Thus, it can be confidently stated that there is no collinearity in the model.

Table 10. Collinearity Assessment.

4.1.4.2. Structural model path coefficients

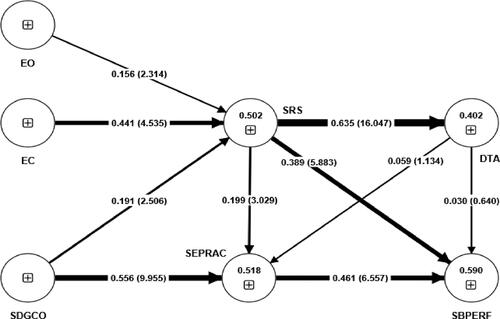

displays the relationship between exogenous and endogenous latent variables. Path coefficients show direct influence magnitude, which helps estimate indirect and total influence. T-statistics values in brackets measure significance. R2-Adjusted value is in the construct. show inner model testing results.

Figure 2. Hypothesized path.

Construct: R-Square adjusted; Inner model: path coefficients (t-value); p ≤ 0.05 (one-tailed test).

Table 11. Summary of hypothesized testing (direct effects) - confidence interval bias corrected.

4.1.4.3. Deterministic coefficients (R2)

To evaluate the strength of a prediction model, the R2 value can be used to measure the combined impact of exogenous variables on endogenous variables. This value indicates the variance in the endogenous construct that all related exogenous variables can explain. The R2 value ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater prediction accuracy. shows the model’s R2 values for all endogenous latent variables.

Table 12. Deterministic coefficients of latent variable.

4.1.4.4. Effect size (f2)

The change in R2 value that occurs when certain exogenous constructs are removed from the model, can be used to determine whether the removed constructs have a significant impact on the endogenous constructs. This measure is referred to as the f2 effect size. presents the effect size f2 value for each endogenous latent variable in the model.

Table 13. Effect size (f2) assessment.

4.1.4.5. PLS-Predict

When conducting research to predict models using Partial Least Squares (PLS), it is important to have a measure of predictive ability (Hair et al., Citation2017). This measure shows how well the model can predict data that was not used in the analysis. If the measure, called Q2 prediction value, is zero or negative, it means that the model has no predictive power on that indicator. Beside that, the researchers can compare the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values with the Linear Model (LM) benchmark to assess the predictive ability of PLS. If PLS-SEM produces lower prediction errors in terms of RMSE (or MAE) than LM for all indicators, it indicates high predictive power. If it produces lower prediction errors for some indicators, it has moderate predictive power. If none of the indicators show lower prediction errors, it lacks predictive power. presents the results of the PLS-Predict analysis on the model’s four endogenous variables. Indicators IA, II, ITCS, ITDM, ITKM, ITPD, ITSCM, and ITSM have high predictive power for the DTA construct. The CO, REO, SU, and SY indicators have moderate predictive power for the SRS construct. Indicators DEG, DNEI, DNES, SCOM, SLSS, and SN have moderate predictive power for the SEPRAC construct. Indicators EC, MSG, PG, RE, SC, and SG have moderate predictive power for the SBPERF construct.

Table 14. PLS-Predict.

Based on the structural model testing results, researchers obtained an Empirical model of Indonesia’s Micro-Business Sustainable Business Performance, as presented in .

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. Substructure equation-1 (sustainable business performance prediction model)

Based on an empirical model of sustainable business performance, the author analyzes the sub-structure of the mathematical equations in the model as follows:

(1)

(1)

With value:

The mathematical equation in substructure-1 shows that three factors have a significant impact on improving sustainable business performance (SBPERF): sustainable resilience strategies (SRS), sustainable entrepreneurial practices (SEPRAC), and digital technology adoption (DTA). SEPRAC is the most influential factor, with a path coefficient value of 46.1% and an effect size (f2) of 36.7%, classified as a ‘large effect’ (Hair et al., Citation2011). This large effect means that when the exogenous SEPRAC construct is removed from the model, it will have a substantive impact on the endogenous construct (SBPERF) in the form of a decrease in the R2 value (this study shows a decrease to 48% or model strength decreases by 11%). The model’s strength is 59%, categorized as an ‘almost strong model’ (Chin, Citation1998) or ‘moderate’ (Hair et al., Citation2011) with ‘medium predictive power’ (Shmueli et al., Citation2019). Overall, the SBPERF prediction model reveals that these three factors can significantly contribute to improving sustainable business performance. Based on confirmatory factor analysis in the measurement model, SBPERF can be measured by two types of benefits: economic and non-economic (Le, Citation2022; Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Economic benefits include sales growth, profit growth, and market share growth over time. Non-economic benefits include efficient use of resources, increased environmental efficiency, and social welfare contributions over time. The trigger factor for increased SBPERF was confirmed to be 59% based on the determination of SRS and its implications for SEPRAC and DTA.

To increase their resilience, micro-business can adopt sustainable resilience strategies (SRS) with four key characteristics. Firstly, they must find creative ways to deal with crises and focus on their survival (Branicki et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2022). Secondly, synergize, they should work with stakeholders to navigate through crises (Alberti et al., Citation2018). Thirdly, they should stay connected to market developments and maintain business continuity (Branicki et al., Citation2018; Heizer et al., Citation2020), one of which is by utilizing digital technology. Lastly, they should re-orient their input, process, and output to meet environmental change demands (Branicki et al., Citation2018; Heizer et al., Citation2020), such as fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in the 2030 agenda (The Ministry of National Development Planning, Citation2015). By embodying these four characteristics, micro-business can become more resilient and better equipped to face environmental changes and crises.

SEPRAC is a trigger that can significantly improve SBPERF, with an empirical confirmation of 46.1%. It refers to entrepreneurial activities that have two missions: ‘must be sustainable’ and ‘must be developed’ (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Must be sustainable, among others: 1) Sustain Nature (SN), preserving nature, the earth, the diversity of living creatures, or ecosystem; 2) Sustain Life Support Sources (SLSS), preserving the environment that supports human life such as reducing plastic waste, pollution, marine, river life; and 3) Sustain Communities (SCOM), preserving local wisdom, history, norms, or cultural values (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). Must be developed, among others: 1) Develop Economic Gain (DEG), means developing the economy of business actors and the surrounding community; 2) Developing Non-Economic Gain for Individuals (DNEI), such as education, gender equality, survival, or life expectancy; and 3) Developing Non-Economic Gain for Society (DNES), such as social ties, regional welfare, and security (Shepherd and Patzelt, Citation2011). On the other hand, By understanding and embodying these aspects, micro-business can enhance their SEPRAC and improve their SBPERF.

The adoption of digital technology is the final trigger in the substructure-1 model that can benefit micro-business. This refers to using digital technology (digitization) in business to create new business models, generate income, and add new value (Urdu et al., Citation2019). By adopting digital technology, micro-business can significantly improve their overall business performance and take advantage of new opportunities.

4.2.2. Substructure equation-2 (digital technology adoption prediction model)

The prediction model for digital technology adoption (DTA) in Indonesian micro-businesses indicates that establishing a sustainable resilience strategy (SRS) is highly likely to trigger DTA in their business processes. The study showed that the effect of SRS is relatively high, at 63.5%. The effect size (f2) of SRS on DTA is significant, with a 67.2% increase, which is considered a ‘large effect’ scale (Hair et al., Citation2011).

(2)

(2)

With value:

Micro-business can improve their competitiveness by adopting digital technology. This involves meeting digitalization prerequisites such as having access to the internet and its devices (Urdu et al., Citation2019), and integrating digital technology into various business operations including production, marketing, sales, customer service, product development, knowledge management, supply chain management, and decision-making (Jha et al., Citation2022, Al-Allak, Citation2010; Lang et al., Citation2022; Ristyawan, Citation2020; Sharma et al., Citation2022; Tamvada et al., Citation2022). Several micro-businesses in Indonesia have adopted digital technology effectively by ensuring the availability of internet access/network and computer/mobile devices connected to the internet in their work environment (Urdu et al., Citation2019). They have also utilized digital technology in their business sales and marketing activities (Jha et al., Citation2022; Tamvada et al., Citation2022), service activities for customers who already use digital technology (Jha et al., Citation2022); and for searching for innovation ideas and product development. Furthermore, they have accurately made business decisions by utilizing data obtained from digital technology (Al-Allak, Citation2010; Ristyawan, Citation2020). Other digital technology adoption characteristics that have been realized in these micro-businesses include the existence of knowledge management activities in the work environment related to business, products, processes, and services assisted by the use of digital technology (Jha et al., Citation2022), and the realization of business supply management processes using digital technology (Al-Allak, Citation2010).

4.2.3. Substructure equation-3 (sustainable entrepreneurial practices prediction model)

The Sustainable entrepreneurial practices (SEPRAC) prediction model is a tool used to better understand the factors that influence the implementation of SEPRAC in micro-business. According to the model, there are several key factors that can have a significant impact on SEPRAC implementation. Specifically, the model identifies micro-business’ orientation in facing the challenges of SDG as the most significant factor, accounting for 55.6% of the overall influence. In addition, the model identifies SRS and DTA as important contributing factors, accounting for 19.9% and 5.9% of the overall influence, respectively. The model strength, which measures the degree of influence of these factors on SEPRAC implementation, is rated at 51.8%. This rating is considered ‘almost strong’ (Chin, Citation1998) or ‘moderate’ (Hair et al., Citation2011), indicating that the identified factors have a significant impact on SEPRAC implementation, but that there may be other factors that also play a role. Overall, the SEPRAC prediction model provides valuable insights into the key factors that micro-business can focus on in order to successfully implement sustainable entrepreneurial practices.

(3)

(3)

With value:

There were three antecedents to SEPRAC. The most influential one, confirmed by 55.6%, is the orientation of micro-business towards fulfilling the SDGs. This orientation integrates social and environmental considerations into business operations and shows an organization’s readiness to adopt sustainability-based initiatives (Horak et al., Citation2018). A comprehensive sustainability orientation generates awareness, confidence, and intelligence related to existing and future opportunities for social, environmental, and economic progress (Horak et al., Citation2018) and law and governance (The Ministry of National Development Planning, Citation2020). This effect size is categorized as ‘large effect’ (Hair et al., Citation2011) and has a value of 42.3%.

4.2.4. Substructure equation-4 (sustainable resilience strategy prediction model)

The substructure-4 mathematical equation identifies key factors that influence the determination of SRS. Expressly, 15.6% of EO, 44.1% of EC, and 19.1% of SDGCO have been confirmed as influential.

(4)

(4)

With value:

The model strength is 50.2%, which is considered to be either ‘almost strong’ (Chin, Citation1998) or ‘moderate’ (Hair et al., Citation2011). It is important to note that the influence of these variables on the endogenous varies at different levels. From the SRS prediction model, EC has a moderate effect size, while the effect size of both EO and SDGCO is small (Hair et al., Citation2011).

Entrepreneurial competency is based on personal attributes and influenced by the surrounding socio-cultural environment (Man and Lau, Citation2000). To achieve effective and outstanding performance (Boyatzis et al., Citation2002), entrepreneurs must have the knowledge and skills to seek out opportunities, take risks and turn ideas into reality (Kuratko, Citation2011). There are six competency areas that contribute to entrepreneurial success: opportunity, relationship, conceptual, organizing, strategic, and commitment competencies (Man and Lau, Citation2000). In Indonesia, several micro-businesses have shown measurable and reliable entrepreneurial competencies. They always look for business opportunities through promotional and marketing activities, build and maintain relationships with customers, partners, and business associations, consider various points of view when searching for solutions to a business problem, prepare plans, allocate resources, and supervise business processes, determine business goals formally and flexibly, and uphold business commitment firmly during times of crisis and tight competition.

Entrepreneurial Orientation refers to the intentions, actions, and decision-making activities involved in entrepreneurship, including processes and practices that lead to the entrepreneurial process. It also describes the strategy-making processes and styles of companies engaged in entrepreneurial activities (Lumpkin and Dess, Citation2001). A confirmatory factor analysis showed that several micro-businesses in Indonesia exhibit the characteristics of EO. These include autonomy, which is demonstrated by the independence of micro-businesses in turning their ideas into reality. Innovativeness is another characteristic exhibited by micro-businesses, as they regularly release new products. Risk-taking is also a common characteristic among micro-businesses, as they are willing to make high-risk decisions to pursue their goals. Additionally, micro-businesses are proactive in all situations, taking the initiative rather than waiting for opportunities to arise. Lastly, they exhibit competitive aggressiveness, aggressively seizing market opportunities and other potential opportunities.

4.2.5. Micro-businesses sustainable resilience strategy is the key driver to success in digital technology adoption and sustainable entrepreneurial practices

It is crucial for a company to align its internal resources with determining its business strategy to build potential business resilience. Empirical evidence has confirmed that Sustainable Resilience Strategy (SRS) can be the key to the success of micro-businesses in Indonesia in adopting Digital Technology Adoption (DTA) and realizing Sustainable Entrepreneurship Practices (SEPRAC). The four dimensions of a sustainable resilience strategy are survival, continuity, reorientation, and synergy.

4.2.5.1. Survival

It’s interesting to see how the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has affected business actors. According to the author’s research, not all business actors have been able to continue their businesses in the last three years. However, those who have been successful are the ones who have found creative ways to deal with the crisis (Branicki et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2022). For instance, ‘Ibu Binangkit’ (not her real name) is a micro-business actor who produces traditional cakes in Bandung City. Since most of her sales come from offices and schools, which were closed due to the pandemic, she had to come up with alternative ways to sell her products. One of the ways she did this was by offering online cooking classes to schools. She would send her products to the students’ homes before the lesson schedule, and during the lesson, she would join online Zoom as a facilitator. Mrs. Binangkit also offers her products to event organizers who provide wedding party services during the crisis. Her cake products are packaged in hamper form and distributed to guests who attend according to predetermined health protocols.

4.2.5.2. Synergy

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has affected many businesses in the past three years. To survive, micro-businesses need to interact with stakeholders to produce a harmonious balance in achieving optimal results (Alberti et al., Citation2018). In-depth interviews with several micro-businesses actors and special interviews with the head of Bandung Regency MSMEs confirm that not all MSME actors have succeeded in continuing their business. However, some micro-businesses have managed to survive the crisis by exploring various collaborations to support their business operations. One way micro-businesses are adapting is by replacing conventional payment systems with financial technology. They are using mobile finance, including QR codes, e-wallets, mobile banking, and more. This shift has been crucial in enabling micro-businesses to continue operating throughout the pandemic crisis. In addition to financial technology, micro-businesses have also collaborated with online transportation services for product delivery. This collaboration has enabled micro-businesses to overcome the logistical challenges posed by the pandemic and deliver their products to their customers. Furthermore, the author recorded other forms of synergy, such as that carried out by a startup owner with the initials ‘KS’ who was successfully fostered in a science and technology park developed by a university. These collaborations have been instrumental in enabling micro-businesses to survive during the pandemic crisis, and they highlight the importance of exploring various collaborations to support business operations. During the in-depth interview, KS revealed that the success of the startup he built was highly dependent on his ability to create conducive synergies with several other business units. His company provides an application that connects consumers with several business units providing household waste processing services, laundry service providers, catering service providers, and others. Using the app, consumers can order services, and notifications will go to both the KS business unit and the waste processing business unit. The waste will then be picked up at the consumer’s address, and the ‘value’ of the waste will be paid to the consumer by the waste processing business when picking up the waste, according to applicable regulations. From this one transaction, the KS business unit gets a fee, consumers get payment for the value of the waste, and the waste processing business unit gets raw materials, which are then processed into recycled products to be resold through recycling shop outlets and online stores that are also connected to the managed apps by KS. Thanks to this synergy, KS’s business has now been running for three years and eight months, and the number of employees has reached seven people. KS is currently still studying at a university that provides a science and technology park and is in the seventh semester. Soon, he will be preparing for his final undergraduate assignment. This example shows how collaborations among different business units can bring significant benefits for all parties involved. By creating an innovative solution that connects consumers with various services and products, KS has been able to establish a successful business that contributes to sustainability efforts.

4.2.5.3. Continuity

In the face of changes that can affect their operations, companies must strive to maintain continuity by strengthening their internal connections and external partnerships (Branicki et al., Citation2018). This is especially true for micro-businesses, who often rely on networking in online and offline communities to maintain the continuity of supply and demand for their products. They admit that networking with various stakeholders has been instrumental in helping them navigate changes in the social, economic, and technological environment. They are greatly helped by events managed by various stakeholders that allow them to maintain demand for their products, even during times when demand is low. To maintain continuity, they must continue to update themselves and improve their social networking capabilities through various online and offline platforms. By doing so, micro-businesses can not only get orders but also other important information, such as the fulfillment of raw materials and access to business development training. This approach enables micro-businesses to remain competitive and adapt to changes in the marketplace, which is essential for their long-term success. Re-orientation is a crucial aspect of a company’s ability to respond positively to changes in the external environment (Branicki et al., Citation2018). Several micro-businesses actors who were successfully interviewed by the author have started responding to the changing needs of the market by providing ‘healthy food’ options. To achieve this, they have started replacing wheat flour with modified cassava flour (mocaf flour). Mocaf is a flour product made from cassava that is fermented by lactic acid bacteria. The fermentation process changes the characteristics of the flour produced, making it suitable for use as raw material for various high-nutrition, low-calorie food products. In addition to mocaf, some micro-businesses have also started using ‘sorghum’ to replace wheat flour as a raw material for health food products. They understand that consuming excessive amounts of wheat flour can result in excess sugar accumulation, which can be harmful to health in the long term. By offering healthier options, they are responding to changing market demands and positioning themselves as providers of nutritious food products. This re-orientation is essential for micro-businesses to remain competitive and meet the evolving needs of their customers.

4.2.6. Digital technology adoption by Indonesian micro-businesses has not significantly improved sustainable entrepreneurial practices and business performance

The author interviewed various micro-business actors in Indonesia from and outside the science and technology park. They all explained that the adoption of digital technology has yet to directly impact sustainable entrepreneurial practices or business performance for most micro-businesses. Their answers were similar in pattern, indicating that: (1) Business owners need to optimize the adoption of digital technology. Most micro businesses have not yet implemented digital technology in their supply chain processes, as well as production activities in the internal supply chain area. Almost all digital technology uses are limited to marketing, sales, and customer relationship management activities; (2) The digital technology used by micro-businesses in Indonesia is still mainly oriented towards economic benefits, with non-economic benefits still needing to be fully promoted through the adoption of digital technology. As a result, it does not trigger the realization of sustainable entrepreneurial practices.

4.2.7. Opportunities and challenges sustainable businesses in micro-business of craft, fashion, food and beverage creative industry sectors

The research was conducted on micro-businesses of craft, fashion, food and beverage creative industry sectors in Indonesia. The following are sustainable business opportunities: (1) Healthy food business. With the widespread availability of education on social media, people are becoming more aware of healthy lifestyles. It has led to a shift towards consuming healthy food. Micro-businesses can take advantage of this trend by providing healthy food options that are low in calories and high in nutrition; (2) Outsourcing of IT administration. The adoption of digital technology could be more optimal in micro-businesses. Although they have received training on using information technology-based applications, they need help implementing them. Micro-businesses need admin staff to focus on their core business activities, such as marketing, sales, and customer relationship management; (3) Waste recycling business. Recycling waste is a lucrative business opportunity for micro-businesses. However, they need scientific contributions and technology transfer from researchers or scientists from research institutions or higher education institutions; (4) App developers. Developing apps can facilitate the community’s management of household waste. The app developer can mediate between waste recycling businesses, waste transportation services, and the community; (5) Local wisdom and environmentally friendly products. Micro-businesses can innovate and create new environmentally friendly products based on local wisdom.

Challenges for developing sustainable businesses for micro-business actors, industry, and higher education institutions as well as science and technology park management: (1) Micro-businesses need guidance regarding digital technology adoption that carries the mission of green digital technology adoption not only in the downstream area but also upstream and internal supply-chain in the business unit’s supply chain flow; (2) Micro-businesses need research findings or technology transfer related to substitute products or alternative raw materials based on local wisdom and environmentally friendly products. For micro-businesses, environmentally friendly products are ‘EXPENSIVE’ in their raw materials. It differs from the perspective of waste recycling business actors who state that the waste processing business opportunity has much potential and is profitable; (3) Local wisdom does not have to be original but can be innovated into something unique and of high value and can even be presented in modern ways. It requires a separate construct, namely sustainable innovation which is capable of producing valuable, rare, and inimitable products so that companies become very passionate and organized in achieving the value of this innovation; (4) The public has begun to become aware of the issue of sustainability. However, the production management costs to achieve this are considered very expensive; (5) Export policy regarding the practice of exporting local wisdom raw materials ‘versus’ importing foreign waste to the domestic market; (6) The culture of ‘production and consumption’ of local products based on local wisdom and environmentally friendly products must begin to be implemented in the current kindergarten generation because the results will only be able to be enjoyed in the next few years.

5. Conclusion, Contribution, Limitation and Recommendation

5.1. Conclusion

This study has identified the Sustainable Resilience Strategy (SRS) as a reliable entrepreneurial strategy for micro-businesses facing the dual transition era of digitalization and sustainability. The SRS is made up of four dimensions: survival, continuity, reorientation, and synergy. These dimensions can help micro-businesses adopt digital technology to meet the challenges of digitalization, while also enabling them to meet sustainable development goals. To achieve sustainable practices, micro-businesses need to have a high orientation towards the challenges of sustainable development goals. Once this is established, SRS can help them mediate and realize sustainable entrepreneurial practices, which in turn have a positive impact on their sustainable business performance. Surprisingly, this study found that adopting digital technology (DTA) has not directly influenced the realization of sustainable entrepreneurial practices. This is because most programs to achieve the 2030 SDG agenda have yet to be implemented through the adoption of digital technology. These programs include protection programs for stakeholders, requirements for producing environmentally friendly raw materials in the supply chain, policies for utilizing local wisdom for domestic competitiveness, and more. Overall, this study suggests that micro-businesses must adopt a Sustainable Resilience Strategy (SRS) by first having a high orientation towards achieving SDG goals. This will enable them to realize sustainable entrepreneurial practices, which will have implications for their sustainable business performance. Additionally, micro-businesses should campaign for the achievements of the SDG agenda through digital technology that has been adopted.

5.2. Contribution

5.2.1. Theoretical contributions