Abstract

A crucial component of creativity is regarded as a prized asset for long-term corporate success and sustainable competitiveness. As a result, not only academic scholars and policy experts but also business leaders have given the topic more attention. The study of creativity is a dynamic, expanding subject of study. This study presents a conceptual model that examines the impact of the work environment and family-work resource spillover on employees’ creativity. The analysis is based on Amabile and Pratt’s ‘dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations’ combined with Greenhaus et al.’s ‘family-work enrichment theory.’ Partial Least Squares (PLS) path modeling in SmartPLS 4 was used to empirically test the proposed hypotheses. The data were collected from 302 researchers working with the agricultural research institute in different centers in Ethiopia. The findings suggested the significantly positive direct impacts of work group support, managerial encouragement, organizational encouragement, a lack of organizational impediments, and family-work resource spillover on employees’ creativity. However, the results did not confirm the direct relationships between sufficient resources, reliable workload pressure, freedom, challenging work, and employees’ creativity. The study provides empirical evidence in the context of the EIAR and delivers solid theoretical and practical implications to experts, leaders, and policymakers. Finally, this study provides a robust mechanism for leaders at agricultural research institutes to develop strategies for enhancing employees’ creativity in the workplace.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Because of the unpredictable economic context in which today’s organizations compete, success demands additional effort (Siyal et al., Citation2021). In today’s dynamic and intensely competitive world, creativity is a vital source of competitive advantage and long-term success (Hughes et al., Citation2018). Employee creativity research was in its infancy until recently, with the majority of earlier studies concentrating on organizational innovation. In the new century, employee creativity started to draw more attention (Wang et al., Citation2021). Employees who are creative at work generate ideas that benefit the organization (El-Kassar et al., Citation2022). Employee creativity may effectively enhance organization development as the key driver of innovation within the organization, and because creativity fosters innovation, growth, and competitiveness (Wang et al., Citation2021), most organizations invest heavily in finding effective ways to encourage employee creativity (Liu et al., Citation2020). Sustainable leadership fosters employee confidence and allows them to make creative. This builds loyalty among the workforce, which in turn boosts productivity and ultimately sustains organizational success (Asad et al., Citation2021).

‘Creativity’ in organizations refers to the generation of novel and useful outcomes (i.e. ideas, solutions, processes, products, etc.), a definition shared by most scholars in the creativity and innovation field (Acar et al., Citation2019; Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016). Novelty is the distinction between an outcome and other outcomes that an organization already has, whereas usefulness is the measure of how potentially beneficial an output is to an organization (Siyal et al., Citation2021). West and Farr, who define innovation as ‘the intentional introduction and application within a role, group or organization of ideas, processes, products or procedures, new to the relevant unit of adoption, designed to significantly benefit the individual, the group, organization or wider society’ (1990). According to this definition, creativity is the act of coming up with ideas, whereas innovation is the act of putting those ideas into practice. However, a lot of research on creativity in companies goes beyond idea creation to include concepts implemented in research practice; creativity and innovation frequently have a lot in common (Acar et al., Citation2019).

Creativity is often regarded as a vital source of competitive strength for organizations (Ferreira et al., Citation2020) since it has become appreciated across diverse tasks, professions, and industries (Kršlak & Ljevo, Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2019). Within organizations that value diversity, change, and adaptation in particular, creative employees are regarded as a valuable resource (Liu et al., Citation2017). In fact, many academics contend that organizations seeking to gain a competitive edge must prioritize boosting the creative performance of their workforce. Employee creativity contributes significantly to organizational innovation, effectiveness, and survival (Ivcevic et al., Citation2021). For organizations aiming to lay a strong foundation for organizational creativity and innovation, having creative employees is a key requirement (Fuchs et al., Citation2021). In order to pinpoint the variables impacting the creative behavior of individuals and teams, several creativity and innovation theories and models have been developed. The componential theory of creativity and innovation in the organizational setting (Amabile, Citation1988), the interactionist theory (Woodman et al., Citation1993) and an organizational culture (OC) model to promote creativity and innovation (Martins & Martins, Citation2002).

These theories, however, only consider how individual and organizational context variables affect the creativity of employees. A substantial body of research has investigated the conditions necessary to foster employees’ creativity, building on aspects of the aforementioned theories and models. The results indicate that creativity is affected by individual characteristics (Amabile, Citation1988; Amabile et al., Citation1996; Green et al., Citation2017) and organizational characteristics (Liu et al., Citation2017; Malek et al., Citation2020). Few studies have attempted to extend the early theories by examining factors outside the organizations that may influence employees’ creativity abilities. For example, other factors identified include family and friends (McKersie et al., Citation2019; Tang et al., Citation2017), supportive family (Guo et al., Citation2021), and social capital dimensions and employee creativity (Oussi & Chtourou, Citation2020).

This study employed the modified Amabile (Citation1988) componential theory of creativity and innovation in organizations. Amabile (Citation1988) demonstrated that the theory incorporates individual and organizational factors that influence employees’ creativity at work and organizational innovation. However, Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016) stated that one limitation of the componential theory of Amabile (Citation1988), as implemented in the work context, is that it concentrates exclusively on internal features within the individual and the organization. It fails to contain external features outside the organization. Thus, Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016) added external factors to the new model. As a result, there is a lack of creativity literature that investigates factors external to organizations, such as family and friends (Hong et al., Citation2018; Tang et al., Citation2017).

However, there are several studies that focus on the influence of factors such as political, economic, and technological on creativity and organizational innovation (Serafinelli & Tabellini, Citation2022). Moreover, a large number of researchers have conducted research studies exploring the relationship between culture and employees’ creativity (Paletz, Citation2022; Parveen et al., Citation2015; Testad et al., Citation2014). As a result, this study tries to close this gap and investigate the impact of other important external variables that cover elements beyond organizational characteristics that may affect employees’ creativity. It is important to determine whether social elements, such as family-work resource spillover from home to work, which are external variables of the organizational setting, affect employees’ creativity. This study will fill a research gap by conducting a direct investigation of the impact of family-work resource spillover on workers’ creativity in developing countries.

More importantly, we aimed to test the impact of work environment and family-work resource spillover on employees’ creativity in a non-western context. Not only does additional research expand the body of knowledge in this field of study (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016), but it also contributes to further proving the external validity of this construct by expanding the research to new contexts and cultures (Malek et al., Citation2020; Malik & Butt, Citation2017). Replication studies are important in the social sciences (Ismail et al., Citation2019) because it is necessary to continually revalidate previous findings in new work contexts in order to show that they are generalizable (Mackey & Porte, Citation2012). By testing the proposed relationships in the Ethiopian setting, this study validates the previously known associations between the study variables in a new context.

2. Theory

2.1. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation

Various empirical studies highlight that the significance of creativity and innovation can be found, and during the past 30 years, there has been a considerable increase in study efforts (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2017). However, the lines between the two ideas of creativity and innovation remain unclear in modern times (Anderson et al., Citation2014). Arguments are made that the lack of compelling theoretical advancements and reliable models hinders focused study and provides clear, practical instructions (Popescu, Citation2022). In response to identifying this gap, Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016) updated Amabile’s well-known model of creativity and innovation in organizations to include the most recent theoretical advancements on motivational factors and their effects on individual and contextual multi-level approaches.

Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016) modified Amabile’s well-known model of organizational creativity and innovation to incorporate the most current theoretical advances on motivational factors and their effects on individual and contextual multi-level approaches. New research findings on the following areas are included in the model: the importance of work, work progress, affect, work orientations, external influences, and synergistic extrinsic motivation (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016). It is widely suggested that these aspects have an impact on innovation and creativity inside businesses (Füzi et al., Citation2022; Tanjung et al., Citation2022). Their dynamic componential model of organizational creativity and innovation is a complicated, multivariate theory (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016).

Rationales for selecting this model as a foundation for the current study comprise reasons from the literature review. Rationales that emerged from the literature review were:

First, most academics agree that social factors can influence an individual’s creativity (Woodman et al., Citation1993). The chosen theory is one of the few that organizes the links between the organizational and human approaches (Fischer et al., Citation2019; Phonethibsavads et al., Citation2019). Thus, this theory has a big impact on creativity in organizational literature (Liu et al., Citation2017; Rosso, Citation2014). Amabile and Pillemer (Citation2012) mentioned that other researchers have used the componential theory to build their own theories of creativity and innovation in organizations, such as (Sternberg & Lubart, Citation1991) investment theory of creativity, (Woodman et al., Citation1993) interactionist theory and (Ford, Citation1996) theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. As a result, applying this model helps in achieving internal validity, and it is widely accepted in the field of creativity. Second, the model offers a broad framework for comprehending the implications and outcomes of perceptions of the working environment (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016). Third, while this paradigm focuses on creativity within organizations, it actually occurs at the individual level (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2018); this matches with the objective of the current study.

Finally, this study will contribute to the dynamic componential theory of creativity and innovation, considering Amabile (Citation1988) model does not consider the influence of external features or the physical environment on employees’ creativity. Numerous studies have expanded the concept and examined how the physical environment affects employees’ creativity in the context of the workplace (e.g. Boënne, Citation2014; Byron & Khazanchi, Citation2012; Du Plessis, Citation2007; Horng et al., Citation2016; Malek et al., Citation2020; Vithayathawornwong et al., Citation2003). Few have, however, concentrated on the impact of outside variables, such as supportive family and friends (McKersie et al., Citation2019; Tang et al., Citation2017) regulatory and customer pressure (Horng et al., Citation2016), and social capital dimensions (Oussi & Chtourou, Citation2020).

The paradigm is divided into two parts: organizational innovation and individual creativity, which are shown to be highly interrelated (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016). In order to create something new, both clusters are described using the same three fundamental multiplicative components: motivation, resources, and processes. The three components of personal creativity include intrinsic motivation (intrinsic task motivation), individual skills and knowledge (domain-relevant skills), and thinking abilities and perceptual or cognitive styles (creativity-relevant skills). The three organizational innovativeness components include the openness to take new risks (motivation to innovate), the offering of funds, time, and labor (resources), in addition to relational and transactional incentives (HRM practices). This extensively used model has a solid foundation in the literature and has been used in different circumstances (e.g. Ashford et al., Citation2018; Fischer et al., Citation2019). As a result, we employ this model as our analytical framework.

2.2. Family-work enrichment theory and resource spillover

Other relevant theory that was used in this study, in addition to the dynamic componential theory of creativity and innovation, is briefly explained in the section that follows.

An overview of empirical studies on the positive interconnectedness between the family and work roles of an employee, Greenhaus et al. (Citation2006) proposed a process of family-work enrichment. The enrichment process represented ‘a transfer of positive experiences’ from family to work (p. 73). In terms of resources, Chan et al. (Citation2020) stated that positive experiences must first become the employee’s personal resource, which then spills over across the family-work boundary. Personal resources, as opposed to contextual resources, are resources that are specific to an individual and can therefore cross the line between family and job (Hobfoll, Citation2002). These resources include physical ones as well as intangible ones like mental and emotional (Tang et al., Citation2017).

In fact, the available indicators of family-work enrichment mostly capture the transfer of personal resources such as knowledge, happy feelings, and motivation (e.g. Carlson et al., Citation2019; Chan et al., Citation2020; Hanson et al., Citation2006; Lin et al., Citation2021). Additionally, prior research has shown that family activities, such as taking care of the home and getting enough sleep, enhance employees’ personal resources, such as their capacity for problem-solving and energy, which they bring with them into their work lives (Hobfoll, Citation2002; Lin et al., Citation2021). In this study, we identified the spillover of psychological resources as the key predictor of employees’ workplace creativity. Following previous accounts of family-work positive spillover, (e.g. Grzywacz & Marks, Citation2000; Hanson et al., Citation2006; Kapadia & Melwani, Citation2021), we define family-work resource spillover as the experience of employees with the transfer of psychological resources produced at home to the workplace. Among the transferable resources, psychological resources are the internal resources that give individuals the vigor and zeal to tackle activities (Sonnentag et al., Citation2020), positive moods (Du et al., Citation2018), and motivations (Tang et al., Citation2017).

3. Hypotheses

3.1. The relationship between determinants of work environment and employees’ creativity

According to Houghton and Dawley (Citation2015) firms should work to improve the stimuli and remove the barriers in order to sustain employee creativity and foster organizational innovation. Employees’ creativity is influenced by a number of factors. For example, Suifan et al. (Citation2018) illustrated that work resources can boost creativity. Similarly, (Amabile et al., Citation1996) stated that human’s creativity may be psychologically affected by perceptions of the availability of appropriate resources by encouraging attitudes toward the intrinsic worth of the work that has been done. When there are sufficient resources, employees do not need to expend their time and effort looking for or asking for more resources from their organization. Instead, they may focus solely on the task at hand, think deeply, and put forth creative ideas without stressing over external constraints because they lack critical resources (Caniëls et al., Citation2014). Adequate resources are necessary for developing an employee’s creative potential because the development of new ideas is a labor- and resource-intensive task (Zhang et al., Citation2018).

When it comes to realistic workload pressure, Yoo et al. (Citation2019) argue that top management should be encouraged to foster creativity as part of organizational motivation to innovate (Amabile, Citation1997), reducing workload pressure on creative employees. Further, Tang et al. (Citation2020) discovered that the association between employees’ creativity and daily time constraints was partially mediated by challenge appraisal. Related to this, Shao et al. (Citation2019) noticed that employee integrative complexity and workload pressure interact to affect employee creativity in such a way that paradoxical leader behavior has the strongest positive relationship with creativity when workload pressure and integrative complexity are both high.

Li et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that job autonomy initiates the motivational-cognitive processes associated with creativity, and support for supervisory autonomy enhances this relationship by virtue of the sequential mediation effects of intrinsic motivation and cognitive flexibility. Individuals should feel free from threat and work in supportive contexts in order to foster their creative cognitions (Wong et al., Citation2018). Chae et al. (Citation2015) also argued that decision-making involvement can in fact help people become more creative.

In terms of work group support, in today’s knowledge-intensive businesses, the majority of projects are carried out by teams of professionals that strive to be both productive and creative when launching new products, services, procedures, or ways of doing business (Amabile et al., Citation2004). Managers must therefore take into account how employees’ peers affect their creativity (Li et al., Citation2020). McLean (Citation2005) emphasized that people who stand out as being very creative are frequently deserving of independence and autonomy. Additionally, as Al Harbi et al. (Citation2019) illustrated, the development of an organizational environment might be a better approach for encouraging individuals’ creativity where followers might have to expend a great deal of time and effort to develop their intellectual capacity, knowledge, and creative thinking skills.

Relating to innovation management capabilities, in order for followers to attain the organization’s common vision and goals, leaders are said to act as an idealized role model, inspire innovative work behavior, offer inspirational motivation, and support and mentor followers (Bednall et al., Citation2018; Suifan et al., Citation2018). It has also been noted that in order to motivate people to engage in innovative work behaviors, the organizational climate must incorporate specific traits such as team cohesiveness, supervisory support, and autonomy (Sönmez & Yıldırım, Citation2019). Individualized care and support for followers’ needs and requirements on the part of leaders may have a greater impact on followers’ participation in creative endeavors. These leaders continually challenge and question followers’ beliefs and presumptions, which stimulates followers’ intellectual thinking and ultimately motivates followers to participate in the creation and application of ideas. These leaders are skilled at connecting the organizational vision to personal objectives, inspiring followers, and boosting motivation (Bednall et al., Citation2018). It is therefore anticipated that leaders in innovation management would be able to motivate employees by linking their future to the direction of the organization and to encourage them to engage in employee creative behaviors by building a strong sense of shared vision and belonging with the organization (Afsar & Umrani, Citation2020).

In terms of organizational motivation to innovate, this includes both organizational encouragement and a lack of organizational impediments. Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016) provided several examples of organizational encouragement of creativity: (1) clear organizational goals, (2) value placed on innovation, and (3) support for reasoned risk-taking & exploration. The key function of a vision is the ‘clarity of and commitment to objectives’ (West & Anderson, Citation1996, p. 682). To unite the team, focus their efforts, and inspire them to continue their creative pursuits, a clear and motivating vision should be created and shared with them (Gordon et al., Citation2017). Creativity and team innovation also benefit greatly from shared purpose and accountability as well as dedication to team goals and organizational objectives (Tang, Citation2019).

The creative process can be risky in many ways, including motivational, emotional, cognitive, and economic risks. It is an uncertain and uncomfortable activity. To develop something new, one must leave their comfort zone, go against the trend, break with social conventions, and be prepared to fail (Tang, Citation2019). Others who feel comfortable, trustworthy, and supported by those around them are more likely to take risks. Team members that feel strongly connected to one another and like they belong on the team are more inclined to work together, communicate, and share ideas in organizational settings (Hülsheger et al., Citation2009). Therefore, it’s critical for team members to establish an atmosphere of mutual respect and trust (Lam et al., Citation2021) and to create a welcoming and cooperative work environment where team members may interact, encourage one another, and work together to solve problems (Tiwana & McLean, Citation2005). Therefore, it is anticipated that determinants of work context will help foster employees’ creativity.

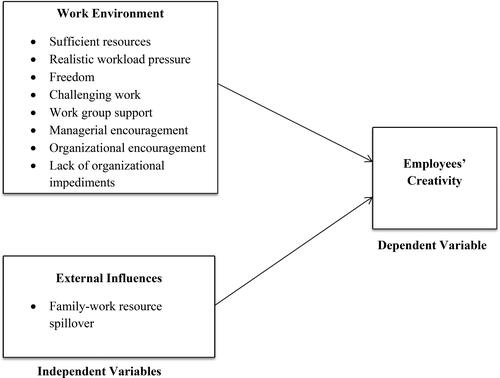

Hypothesis 1: Determinants of work environment: (a) sufficient resources, (b) realistic workload pressure (c) freedom (d) challenging work (e) work group support (f) managerial encouragement (g) organizational encouragement and (h) lack of organizational impediments are positively related to employees’ creativity.

3.2. The relationship between family-work resource spillover and employees’ creativity

Hennessey (Citation2010) clarified that some creativity studies have shown that external factors influence employees’ creativity. However, the literature was limited regarding the influence of external factors on creativity (e.g. Chua et al., Citation2015; Horng & Lee, Citation2009; Kwan et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2018; Tang et al., Citation2017). According to earlier research, family activities like taking care of the house and getting enough sleep help employees develop their personal resources, such as their energy and problem-solving skills, which they bring with them into their work lives (Tang et al., Citation2017; Zhu et al., Citation2018).

Employees who have happy home lives are likely to develop significant psychological resources. The accumulation of psychological resources drives and motivates resource spillover between family and work (Akhtar et al., Citation2015; Greene, Citation2006; Kapadia & Melwani, Citation2021; Lin et al., Citation2021). Positive psychological moods produced in family life can be transferred into work life, which can lead to the spillover of psychological resources. For example, having a high level of energy at home might boost work activities (Mauno & Ruokolainen, Citation2017). Positive emotional states at home might transfer to the workplace (Song et al., Citation2008). And the level of motivation for work can be determined at home and influenced at work (Peña-Sarrionandia et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it is anticipated that social factors such as family-work resource spillover and employees’ creativity will be positively correlated ().

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of the Study Adapted from Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016).

Hypothesis 2: family-work resource spillover is positively related to employees’ creativity.

4. Method

This article employs quantitative data collection and analysis methodologies. The study attempted to investigate the links between determinants of employee creativity and an outcome from the perspective of employees using a large sample size obtained from the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). Therefore, a deductive approach is used to examine their relationships.

Since the EIAR was established in the middle of the 1960s, it has undergone considerable structural and organizational changes. Since then, numerous crop types and related production technologies have been created and made available. Additionally, a certain level of specialists is being developed, and the system has a strong research culture tradition (Abate et al., Citation2011). In recent years, the EIAR has taken the lead in reorienting agricultural research for development toward more expansive partnerships within a framework of innovation systems and value chains. Through a series of trainings, development, and continuous experimentation via a creative platform, the initiative begins through a supported training program for researchers (Kebebe, Citation2019; Regasa Megerssa et al., Citation2020).

4.1. Sample and data

The sample for this study was calculated with a 95% confidence level using Yamane’s (Citation1973) formula (EIAR has a total of 1317 researchers, of whom 378 are BSc, MSc, 797 are DVM, and 136 are PhD). Substitute numbers in the formula; the number of samples is n = 306.814; however, the sample size formulas indicate the required number of responses. A 30% increase in the sample size is frequently used to account for nonresponse (Israel, Citation1992). Thus, to obtain reliable data, the sample size was increased to 400.

All 17 research centers in the EIAR were included in the study’s target population. These facilities were included in the study because they represent the many agricultural institutions found in the Ethiopian economy. Following Ragab and Arisha (Citation2017) we used a three-stage multi-proportionate systematic random sampling method to locate the appropriate respondents for each of the EIARs. In the first stage, purposeful sampling was used to choose the EIAR researchers. In the second stage, stratified sampling was used to establish four strata: first, BSc; second, MSc; third, DVM; and fourth, PhD degree levels. The third stage involved proportionate systematic random sampling based on employees’ years of experience.

400 questionnaires were distributed with the aim of collecting data for this research, of which 342 were returned. However, 40 of them were not fully completed. The majority of these respondents responded to only a few of the survey’s questions and missed the others. 28 cases with 20% or more missing data were excluded from the analysis process altogether. A further 12 cases demonstrated less than 20% missing data and a very low standard deviation in their responses. A closer look revealed that these respondents had given the identical answer to nearly every question on the survey and therefore were considered to be of low value and were also excluded from further analysis. In total, 302 questionnaires were filled out, and no missing data were discovered.

Outliers were thought to be critical to find because they could interfere with statistical analysis (Knief & Forstmeier, Citation2021). Extreme or unusual responses were few in the questionnaire, which mainly used Likert-type scale items. It was therefore determined that any outliers, if any, were a result of entry error rather than their actual presence in the data set. Following tests suggested by Kwak and Kim (Citation2017) and Osborne and Overbay (Citation2004), for each variable, frequency tables were analyzed to check for any outliers. Examining the frequency table revealed certain high values, such as 23, 12, 44, and 32, which were the result of entering errors. The data set was cleaned up for further analysis once these values were manually corrected.

In the sample, the majority 64.6 percent of the respondents were ‘Men’ while 35.4 percent were ‘Female’. In terms of age, majority 67.6 percent of the respondents were less than 35 years, 14.9 percent were 36–40 years, 14.2 percent were 41–45 years and least 3.3 percent were above 45 years respectively. Regarding the highest level of education of the respondent, 59.3 percent of participants had a master’s degree, followed by 28.1 percent were bachelor’s degree, 11.9 percent PhD, 0.7 percent were DVM. In terms of experience, majority 38.8 percent of the respondents were above 7 to 9 years followed by 30.1 percent were 4 to 6 years, 21.2 percent were above 10 years and least 9.9 percent were less than 3 years respectively.

4.2. Instruments and measures

In the social sciences, the survey method is common and linked with a deductive research approach (Rahi, Citation2017). According to Jenny Rowley (Citation2014), when an investigator wishes to analyze a sample based on statistics or determine behavior, belief frequency, attitudes, processes, experience, or forecast, a survey is utilized. A survey may not be appropriate for both the study and its investigator, but it may be suitable for the respondents (Rahi, Citation2017; Rowley, Citation2014). According to Khalid et al. (Citation2012), the most efficient data collection technique is to use a questionnaire, especially when the researcher knows exactly what questions to ask and how to quantify the elements. Because the study approach is quantitative, a survey questionnaire appears to be the best choice for this research approach (Rahi, Citation2017; Rahi et al., Citation2019).

4.3. Statistical procedure

We employed Smart PLS (4.0.7.8), a statistical tool, to examine the data through partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), a variance-based structural equation modeling technique. PLS-SEM is based on maximizing the explained variance of the endogenous latent variables. In particular, it is appropriate for exploratory and predictive studies (Manley et al., Citation2021). This study followed the standard evaluation guidelines for reporting PLS-SEM results (e.g. Hair et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Henseler et al., Citation2016). Many management disciplines recognize the case for PLS-SEM as a viable methodology. For example, PLS-SEM differs from CB-SEM in that it does not impose minimal criteria or constrictive assumptions on measurement scales, distributional assumptions, or sample sizes (Hair et al., Citation2017; Sarstedt et al., Citation2021). The following rationales support the use of PLS-SEM in this study:

First, we modeled work environment and family-work resource spillover with the Ethiopia Institute of Agricultural Research employees’ creativity as composites estimated in the conceptual model (Henseler et al., Citation2016). Second, we used the work environment and family-work resource spillover to predict employees’ creativity, responding to the call to use PLS-SEM as a prediction-oriented approach to SEM (Manley et al., Citation2021; Purwanto & Sudargini, Citation2021). Third, the study model shows a relatively complicated structure with a number of manifest and latent variables and the presence of multi-dimensionality in the constructs included in the model (Hair et al., Citation2017; Sarstedt et al., Citation2021). Fourth, it is believed that the model’s structural relationships are still in the early stages of theory development or extension, enabling the exploration and development of new phenomena (Richter et al., Citation2015). Finally, the benefits of PLS-SEM in terms of less rigorous standards or restricted assumptions allowed us to develop and estimate our model without adding extra restrictions (Hair et al., Citation2019; Purwanto & Sudargini, Citation2021).

5. Analysis and results

According to the standard evaluation guidelines for reporting PLS-SEM results (Hair et al., Citation2017), three stages are involved in PLS-SEM analysis and interpretation: (1) evaluate the measurement model’s reliability and validity, (2) evaluate the structural model, and (3) evaluate structural equation modeling and global model fit.

5.1. Measurement model

The evaluation of the measurement model in PLS-SEM was based on the individual indicator reliability, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity of the constructs.

The reliability of all reflective constructs was evaluated by analyzing two types of reliability indicators: Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR). The recommended value is ≥ 0.70 for all types of reliability (Hair et al., Citation2011). The values of Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability exceeded 0.70, confirming the convergence or internal consistency of all constructs ().

Table 1. Measurement model.

The average variance extracted (AVE) provides an indication of convergent validity. Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) recommend an AVE value ≥ 0.50, which means that ≥ 50% of the indicator variance should be accounted for. Consistent with this recommendation, all constructs had AVE values that exceeded this value (). Moreover, we assessed the discriminant validity based on Hair et al. (Citation2017) guidelines. We employed Fornell and Larcker criterion. As per the Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion, the square root of the construct was greater than the absolute value of their respective correlations. shows that the results for the cross-loadings of all indicators or dimensions loaded higher on their respective constructs than on the other constructs, and the cross-loading differences were much higher than the suggested threshold of 0.10 (Gefen & Straub, Citation2005).

Table 2. Discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker criterion).

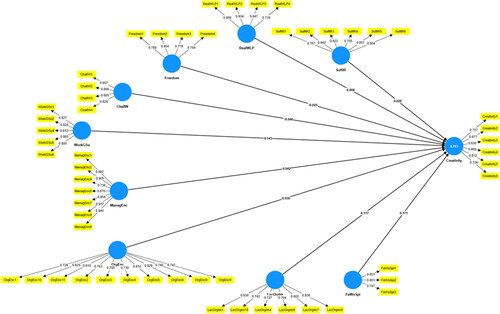

5.2. Assessment of structural model

We assessed the issue of multicollinearity in the data using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Aiken et al. (Citation1991) recommended that the values of VIF must be <10, and this study found VIF values within the suggested range, depicting no issue of multicollinearity in the data set (see and ). According to Henseler et al. (Citation2016), the standardized root-mean-square (SRMR) values should be lower than 0.08 (for a sample size greater than 100). Thus, we found a significant model fit for this study (0.069). The determination coefficient (R2) should be greater than 0.1 (Chin et al., Citation1998). This study found that 78.3% of the variance in employees’ creativity was explained by the work environment and family-work resource spillover (see ). Additionally, Q2 value ought to be greater than 0. As a result, both of this study’s findings were significant, and the study model’s predictive usefulness was attained (Falk & Miller, Citation1992).

Table 3. Collinearity statistics (Outer VIF values).

Table 4. Collinearity statistics (inner VIF values).

Table 5. R-square and model fit.

5.3. Structural equation modeling

The sizes and significances of the path coefficients that reflect the hypotheses were examined. The significance of the path coefficients was calculated using the bootstrapping procedure (with 5000 bootstrap samples). provides structural model results, and provides the path coefficients, standard deviation, t-statistics, and p-values.

Figure 2. PLS-SEM showing relationships in variables (Ringle et al., Citation2022).

Table 6. Hypothesis constructs (Path coefficients, Mean, STDEV, T values, p values).

The PLS-SEM findings show that (H1a) sufficient resources have no significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = 0.029, t = 1.071, p = 0.284). (H1b) with values of (β = 0.008, t = 0.297, p = 0.767) realistic work load pressure has no significant effects on employees’ creativity. (H1c) employee creativity is unaffected by freedom (β = -0.025, t = 0.93, p = 0.353). (H1d) challenging work has a none-significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = -0.046, t = 1.596, p = 0.111). While (H1e) work group support has a significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = 0.143, t = 2.417, p = 0.016). (H1f) managerial encouragement has a significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = 0.042, t = 2.156, p = 0.032). (H1g) organizational encouragement has a significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = 0.556, t = 14.391, p = 0). (H1h) lack of organizational impediment has a significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = 0.117, t = 2.393, p = 0.017). Furthermore, (H2) family-work resource spillover has a significant effects on employees’ creativity (β = 0.171, t = 2.382, p = 0.017). As a result, we accepted H1e, H1f, H1g, H1h, and H2’s direct relationships.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The present study examined the impacts of the work environment and family-work resource spillover on employees’ creativity in the EIAR. H1 stated that the impacts of the work environment are: (a) sufficient resources; (b) realistic work load pressure; (c) freedom; (d) challenging work; (e) work group support; (f) managerial encouragement; (g) organizational encouragement; and (h) a lack of organizational impediments on employees’ creativity. This hypothesis comprised eight types of work environments. Results indicate four direct impacts were supported: work group support, managerial encouragement, organizational encouragement, and a lack of organizational impediments. There were no direct relationships found between adequate resources, realistic work load pressure, freedom, challenging work, and employees’ creativity.

The statistical analysis of this study showed a non-significant direct relationship between sufficient resources and employees’ creativity. There is mixed evidence about the relationship between sufficient resources and employees’ creativity, with some studies indicating a positive relationship between both variables (e.g. Dul & Ceylan, Citation2011; Rasulzada & Dackert, Citation2009; Sonenshein, Citation2014), and other studies found no significant relationship (Mueller & Kamdar, Citation2011; Ramos et al., Citation2018; Yeh & Huan, Citation2017). For example, in a study conducted by Zhou et al. (Citation2008), it was discovered that access to resources and entrepreneurial creativity don’t seem to be directly associated; instead, having access to resources is just a subdued way to encourage creativity at the workplace. The findings of this study make it clear that having access to resources does not ensure employees’ creativity.

The statistical analysis of this study indicated non-significant direct relationship between realistic workload pressure and employee creativity. In the literature, various types of work pressure have been examined in relation to employees’ creativity: workload pressure (e.g. ElMelegy et al., Citation2016; Mumford et al., Citation2013), time pressure (e.g. Baer & Oldham, Citation2006), and with both workload and time pressure (Shao et al., Citation2019). High workload pressure will force employees to use simple and ineffective methods that are less creative. As a result of the lack of time for creativity, excessive workload pressure has a detrimental effect (Mumford et al., Citation2010). On the other hand, Aleksić et al. (Citation2017) have discovered that there is a positive, negative, or no relationship between creativity and time pressure. There are a few studies that indicate that when the work’s domain shifts, as it does, for instance, in high-pressure jobs requiring high creativity, concentrating on important activities enhances employee creativity. Thus, the domain’s nature could be used to explain the present study’s inconsistent results. This may require further investigation.

The non-significant direct relationship between freedom and employees’ creativity, as found in the present study, is consistent with that of (e.g. Naranjo-Valencia et al., Citation2011; Zhang et al., Citation2020). Unfortunately, there are also studies that show the opposite is true (Wheatley, Citation2011). Chiang and Hsieh (Citation2012) provided empirical evidence that employee creativity is positively influenced by freedom, which is the key to enhancing creativity. There are those who support the empowerment of employees. These mixed findings in research on freedom and employee creativity highlight the need for strong evidence of the nature of this relationship.

The results indicate that the direct relationship between challenging work and employees’ creativity is non-significant. Challenging work refers to ‘a sense of having to work hard on challenging tasks and important projects’ (Amabile et al., Citation1996, p. 1166). According to Amabile and Kramer (Citation2007), challenging work improves individual creativity. Several empirical studies have looked at how challenging work affects employees’ creativity, but the results have been inconsistent and inconclusive. For example, while some studies have found a positive relationship between challenging work and employees’ creativity (e.g. Carmeli et al., Citation2007; Ramos et al., Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2015), others indicate that challenging work is not associated with employee creativity (e.g. Rasulzada & Dackert, Citation2009; Zhou et al., Citation2012).

Sripirabaa and Maheswari (Citation2015) argued that employees’ fear of failure, which inhibits creativity, could be the cause of the non-significant relationship between those two variables. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that providing employees with demanding tasks under supportive supervision increases their intrinsic motivation, which produces more productive and creative results (Liu et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the findings of this study highlight the idea that even with increasingly challenging work, creativity will not occur in the absence of a supportive work environment and a willingness to fail.

The impact of workgroup support on employees’ creativity has rarely been studied. Of these studies, some showed positive relationship outcomes (e.g. Foss et al., Citation2013; Kremer et al., Citation2019; Lin & Liu, Citation2012; Ramos et al., Citation2018) in alignment with findings reported in this study, and some showed non-significant associations between work group support and employee creativity (e.g. Foss et al., Citation2013; Rasulzada & Dackert, Citation2009). For example, the current study’s findings are consistent with the componential model of organizational creativity and innovation (Amabile, Citation1988) and the interactionist theory (Woodman et al., Citation1993), both of which show a direct relationship between workgroup support and employee creativity. Similarly, Ramos et al. (Citation2018) study found that support from work groups did significantly impact how well employees came up with ideas. However, the results contradict those of Nijstad and De Dreu (Citation2002), who provided evidence that those working alone are more creative than those working in groups.

The statistical analysis of this study revealed a significant direct relationship between managerial encouragement and employees’ creativity. The empirical evidence regarding the relationship between the two variables is mixed. For instance, managerial encouragement has drawn significant research attention as a critical element that could positively influence employees’ creativity in contemporary creativity literature (e.g. Chang & Teng, Citation2017; Chen & Hou, Citation2016; Khalili, Citation2016; Kim & Yoon, Citation2015; Kremer et al., Citation2019). According to other studies, managers do not significantly impact their employees’ creativity (e.g. Binnewies et al., Citation2008; Foss et al., Citation2013). These inconsistent findings highlight the need for additional study to clarify the nature of this relationship between managerial encouragement and employees’ creativity and offer conclusive evidence.

The main variable influencing creativity in the sample of the EIAR was found to be organizational encouragement. This finding supports the author’s claims that the workforce’s creativity is influenced by the encouragement they receive (Ramos et al., Citation2018). Due to the importance of organizational encouragement, it is essential to develop strategies that value and respect individuals while recognizing and rewarding creative outcomes (Chang et al., Citation2014). Thus, the outcome was consistent with other research that demonstrated positive relationships between organizational encouragement and employees’ creativity.

With regard to organizational impediment, the statistical analysis showed a significant direct relationship between a lack of organizational impediment and employees’ creativity. According to Diliello et al. (Citation2011), to sustain employee creativity, organizations should work to improve the stimulants and remove the barriers. In addition, a recent study conducted by ElMelegy et al. (Citation2016) showed that the lack of organizational impediments was significantly linked to employees’ creativity. Similarly, several studies revealed positive relationships between a lack of organizational impediments and employees’ creativity (Byron & Khazanchi, Citation2012; McLean, Citation2005; Ramamoorthy et al., Citation2005). Therefore, it is evident from the results of this study that a lack of organizational impediments leads to employee creativity.

Finally, the results revealed that family-work resource spillover is an important source of psychological resources that facilitate employees’ creativity at work. According to Amabile and Pratt (Citation2016) suggestion that variables outside of organizations may have an impact on employees’ creativity, the current study examined the direct relationship between family-work resource spillover and employees’ creativity. Although no research has yet looked at the association between family-work resource spillover and employees’ creativity, other relevant evidence can help explain this finding. For example, the spouse’s emotional support (a contextual resource) may lead to a more positive mood and higher self-esteem. These internal resources may eventually be applied at work, resulting in a positive mood, a robust work ethic, or even better work output (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012).

Examining the impact of family-work resource spillover as an external variable on employees’ creativity supports Tang et al. (Citation2017) argument that the psychological resources that an employee brings to work can enhance their creativity. An individual’s momentary thinking and thought-action repertoire are expanded by psychological resources, allowing them to recognize a wide range of alternatives (Fredrickson, Citation2001). For example, in a study conducted by Gohar et al. (Citation2022), individual views of desirability and the viability of entrepreneurial behavior are significantly shaped by family. According to the data, individuals’ entrepreneurial activity is more likely to be motivated by family conditions and situations in Muslim societies. Therefore, the findings provide evidence of family-work resource spillover on the relationship between not only individual or organizational factors but also external factors such as family-work resource spillover and employees’ creativity, as characterized by the EIAR.

Research on the relationship between family and work has long argued that employees’ social and family lives outside of work can either improve or worsen their work performance and creativity. Work and personal life are becoming increasingly intertwined and affecting one another. Additionally, there is some evidence that creative ideas often do not stay in the workplace, and the study result show that family can offer the resources, support, and motivation needed to be creative at work. Like previous psychological studies have identified the family as one of the most important factors in transforming the ability to be creative into an actual skill and competence, and that family relationships may help individuals acquire specific personal characteristics, such as a creative nature or openness to new things that may enhance their creativity at work.

6.1. Theoretical contributions

The current study has extended the dynamic componential theory of creativity and innovation in organizations (Amabile & Pratt, Citation2016) by examining the impact of a new external variable (family-work resource spillover) on employees’ creativity. However, there are several studies that focus on the influence of factors such as political, economic, and technological on creativity and organizational innovation (Serafinelli & Tabellini, Citation2022). Moreover, a large number of researchers have conducted research studies exploring the relationship between culture and employees’ creativity (Paletz, Citation2022; Parveen et al., Citation2015; Testad et al., Citation2014). As a result, this study tries to close this gap and investigate the impact of other important external variables that cover elements beyond organizational characteristics that may affect employees’ creativity. It is important to determine whether social elements, such as family-work resource spillover from home to work, which are external variables of the organizational setting, affect employees’ creativity.

6.2. Practical contributions

The empirical results from the PLS-SEM analysis have significant practical and managerial implications for organizations based on how the work environment and family-work resource spillover impact the development of employees’ creativity. First, regarding the relationship between various factors and employees’ creativity, the existing literature has provided inconsistent outcomes. The findings of the present study are relevant because they offer additional evidence of the nature of the relationship in the EIAR context. Second, when considering employees’ creativity, managers must take the required changes into account. Effective leadership significantly influences sustainable human resource creativity practices, which in turn influence sustainable innovation. Furthermore, sustainable innovation has a noteworthy effect on the overall effectiveness of organizations (Asad et al., Citation2021). Individual preferences, fundamental concerns, and problem-solving approaches can change over time, demanding improvements to ensure the right fit between individuals’ creative potential and their work environment.

6.3. Limitations and directions for future research

This study, like any empirical study, contains limitations that provide opportunities for further research. First, our study relied exclusively on the self-reporting method of data collection, which did not provide us with an ‘outside’ or ‘independent’ perspective on participants’ views. Participants may describe themselves differently for a variety of conscious and unconscious reasons, making self-reported data susceptible to inaccuracies (Roth et al., Citation2022). Second, in the current study, the idea of creativity as a single construct relating to idea generation was covered (Amabile et al., Citation1996, p. 1), while some studies have analyzed and compared various forms of creativity and their affecting elements, such as radical and incremental creativity (Madjar et al., Citation2011). Thus, there is a need for future studies that examine such types of creativity and their influencing factors. Third, the current study focused only on the individual level. Amabile (Citation1997) stated that the model can be applied to individuals and small teams. According to Nijstad and De Dreu (Citation2002), understanding what impedes or encourages creativity and group innovation is crucial since groups are important organizational building blocks in the workplace. It is therefore necessary to analyze the same model using a different unit of analysis, such as a team, in order to better understand the variables that affect group creativity. Finally, the current study added to the literature by investigating the impact of family-work resource spillover on organizations as an external factor. However, other external factors, such as government rules and regulations, customers, public opinion, and globalization, must be investigated.

Authors’ contributions

The theoretical foundation, research design, survey execution, data evaluation, and discussion were done by YMY. YMY wrote the first draft of the manuscript. The critical review and manuscript revisions were provided by DAG and ATD. All authors read and approved the submitted version. DAG and ATD have provided their written consent to the submission of the manuscript in this form. YMY has assumed responsibility for keeping DAG and ATD informed of the progress through the editorial review process, the content of reviews, and any revision made.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of University of Gondar. The review board of college of business and Economics exempted the research for ethical approval, as it is a survey-based study. The study obtained the consent of the employees working in the EIAR and they filled the questionnaires willingly.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our gratitude to all participants of this survey. We are very grateful to Professor Susan Cozzen and Dr. Caleb Akinrinade for their feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript which was handed in the form of a thesis. We are also grateful to Mulatu Tilahun for his wonderful support.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets for this study are available, and the same can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request. This study was conducted in the context of Ethiopia; the data were collected from researchers working in the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yohannes Mekonnen Yesuf

Yohannes Mekonnen Yesuf is an assistant professor of Management in Faculty of Business and Economics Woldia University Ethiopia. He earned his PhD from University of Gondar, Ethiopia. Throughout his career, Yohannes has worked on multiple teaching and administrative positions in national and international settings. Currently, his research interests include creativity and innovation, technology management, entrepreneurship, leadership management, strategy and policy. He has been part of different research and evaluation projects at University and national levels.

Demis Alamirew Getahun

Demis Alamirew Getahun is an Associate Professor of Management at the University of Gondar, specifically within the College of Business and Economics, School of Management & Public Administration. He earned his Master’s Degree from Addis Ababa University in 2011 and his first degree from Mekelle University in 2007. Additionally, he obtained his PhD in Business Studies from Punjabi University in 2016, India. Currently, he serves as a college dean while also engaging in teaching, research, and community service. He acts as the principal advisor to MBA and PhD students at the University of Gondar and other universities in Ethiopia. His research interests include Human Resource Management, Entrepreneurship, Organizational Behavior, leadership, and related subjects.

Asemamaw Tilahun Debas

Asemamaw, PhD in Public Administration is a distinguished academic with robust educational background, including a Master of commerce, Master of Public Management and policy and a BA in Business Management. As an Associate Professor of Management in the esteemed School of Management and Public Administration at the University of Gondar, Asemamaw brings expertise and passion to the field. His research is dedicated to the realms of knowledge management, organizational behavior, entrepreneurship, and information technology. For inquiries, please contact him at [email protected].

References

- Abate, T., Shiferaw, B., Gebeyehu, S., Amsalu, B., Negash, K., Assefa, K., Eshete, M., Aliye, S., & Hagmann, J. (2011). A systems and partnership approach to agricultural research for development: Lessons from Ethiopia. Outlook on Agriculture, 40(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5367/oa.2011.0048

- Acar, O. A., Tarakci, M., & van Knippenberg, D. (2019). Creativity and innovation under constraints: A cross-disciplinary integrative review. Journal of Management, 45(1), 96–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318805832

- Afsar, B., & Umrani, W. A. (2020). Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. European Journal of Innovation Management, 23(3), 402–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2018-0257

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Akhtar, R., Boustani, L., Tsivrikos, D., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2015). The engageable personality: Personality and trait EI as predictors of work engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.040

- Al Harbi, J. A., Alarifi, S., & Mosbah, A. (2019). Transformation leadership and creativity: Effects of employees pyschological empowerment and intrinsic motivation. Personnel Review, 48(5), 1082–1099. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2017-0354

- Aleksić, D., Mihelič, K. K., Černe, M., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017). Interactive effects of perceived time pressure, satisfaction with work-family balance (SWFB), and leader-member exchange (LMX) on creativity. Personnel Review, 46(3), 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2015-0085

- Amabile, T. (1988). Amabile_A_Model_of_CreativityOrg.Beh_v10_pp123-167.pdf. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 123–167.

- Amabile, T. M. (1997). Management. California Management Review, 40(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165921

- Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184. https://doi.org/10.2307/256995

- Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2007). Inner work life. Harvard Business Review, 85(5), 72–83.

- Amabile, T. M., & Pillemer, J. (2012). Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.001

- Amabile, T. M., & Pratt, M. G. (2016). The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 157–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.10.001

- Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., & Kramer, S. J. (2004). Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.12.003

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128

- Asad, M., Asif, M. U., Bakar, L. J. A., & Sheikh, U. A. (2021). Transformational leadership, sustainable human resource practices, sustainable innovation and performance of SMEs [Paper presentation]. 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA), 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1109/DASA53625.2021.9682400

- Ashford, S. J., Caza, B. B., & Reid, E. M. (2018). From surviving to thriving in the gig economy: A research agenda for individuals in the new world of work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2018.11.001

- Baer, M., & Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.963

- Bednall, T. C., E. Rafferty, A., Shipton, H., Sanders, K., & J. Jackson, C. (2018). Innovative behaviour: How much transformational leadership do you need? British Journal of Management, 29(4), 796–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12275

- Binnewies, C., Ohly, S., & Niessen, C. (2008). Age and creativity at work: The interplay between job resources, age and idea creativity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(4), 438–457. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810869042

- Boënne, M. (2014). Fostering creativity in the organization structures on the creativity of inventors creativity in the organization which management instruments and organizational.

- Byron, K., & Khazanchi, S. (2012). Rewards and creative performance: A meta-analytic test of theoretically derived hypotheses. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 809–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027652

- Caniëls, M. C. J., De Stobbeleir, K., & De Clippeleer, I. (2014). The antecedents of creativity revisited: A process perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(2), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12051

- Carlson, D. S., Thompson, M. J., Crawford, W. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2019). Spillover and crossover of work resources: A test of the positive flow of resources through work–family enrichment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(6), 709–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2363

- Carmeli, A., Cohen-meitar, R., & Elizur, D. (2007). The role of job challenge and organizational identification in enhancing creative behavior among employees in the workplace. Journal of Creative Behavior, 41(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2007.tb01282.x

- Chae, S., Seo, Y., & Lee, K. C. (2015). Effects of task complexity on individual creativity through knowledge interaction: A comparison of temporary and permanent teams. Computers in Human Behavior, 42, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.015

- Chan, X. W., Kalliath, P., Chan, C., & Kalliath, T. (2020). How does family support facilitate job satisfaction? Investigating the chain mediating effects of work–family enrichment and job-related well-being. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 36(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2918

- Chang, L.-L., Backman, K. F., & Huang, Y. C. (2014). Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(4), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-04-2014-0032

- Chang, J. H., & Teng, C. C. (2017). Intrinsic or extrinsic motivations for hospitality employees’ creativity: The moderating role of organization-level regulatory focus. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 60, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.10.003

- Chen, A. S. Y., & Hou, Y. H. (2016). The effects of ethical leadership, voice behavior and climates for innovation on creativity: A moderated mediation examination. Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.10.007

- Chiang, C.-F., & Hsieh, T.-S. (2012). The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.011

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Chua, R. Y. J., Roth, Y., & Lemoine, J. F. (2015). The impact of culture on creativity: How cultural tightness and cultural distance affect global innovation crowdsourcing work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(2), 189–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839214563595

- Diliello, T. C., Houghton, J. D., & Dawley, D. (2011). Narrowing the creativity gap: The moderating effects of perceived support for creativity. Journal of Psychology, 145(3), 151–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.548412

- Du Plessis, M. (2007). The role of knowledge management in innovation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(4), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270710762684

- Du, D., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2018). Daily spillover from family to work: A test of the work–home resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000073

- Dul, J., & Ceylan, C. (2011). Work environments for employee creativity. Ergonomics, 54(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2010.542833

- El-Kassar, A. N., Dagher, G. K., Lythreatis, S., & Azakir, M. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding: The roles of HR practices, organizational support for creativity, creativity, innovative work behavior, and task performance. Journal of Business Research, 140, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.079

- ElMelegy, A. R., Mohiuddin, Q., Boronico, J., & Maasher, A. A, The American University in Dubai. (2016). Fostering creativity in creative environments: An empirical study of saudi architectural firms. Contemporary Management Research, 12(1), 89–120. https://doi.org/10.7903/cmr.14431

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press.

- Ferreira, J., Coelho, A., & Moutinho, L. (2020). Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation, 92–93, 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2018.11.004

- Fischer, C., Malycha, C. P., & Schafmann, E. (2019). The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 137. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00137

- Ford, C. M. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1112–1142. http://www.jst. https://doi.org/10.2307/259166

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Foss, L., Woll, K., & Moilanen, M. (2013). Creativity and implementations of new ideas: Do organisational structure, work environment and gender matter? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 298–322. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-09-2012-0049

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

- Fuchs, M., Fossgard, K., Stensland, S., & Chekalina, T. (2021). Creativity and innovation in nature-based tourism: A critical reflection and empirical assessment. Nordic Perspectives on Nature-Based Tourism, 175–193. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789904031.00022

- Füzi, A., Clifton, N., & Loudon, G. (2022). New in-house organizational spaces that support creativity and innovation: The co-working space.

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16, 91–109. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01605

- Gohar, M., Abrar, A., & Tariq, A. (2022). The role of family factors in shaping the entrepreneurial intentions of women: A case study of women entrepreneurs from Peshawar, Pakistan. In The Role of Ecosystems in Developing Startups: Frontiers in European Entrepreneurship Research, 40.

- Gordon, E., Haas, J., & Michelson, B. (2017). Civic creativity: Role-playing games in deliberative process. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3789–3807.

- Green, P. I., Finkel, E. J., Fitzsimons, G. M., & Gino, F. (2017). The energizing nature of work engagement: Toward a new need-based theory of work motivation. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.007

- Greene, J. C. (2006). Toward a methodology of mixed methods social inquiry. Research in the Schools, 13(1), 93–98.

- Greenhaus, J. H., Powell, G. N., Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

- Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.111

- Guo, J., Zhang, J., & Pang, W. (2021). Parental warmth, rejection, and creativity: The mediating roles of openness and dark personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110369

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage.

- Hanson, G. C., Hammer, L. B., & Colton, C. L. (2006). Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of perceived work-family positive spillover. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.249

- Hennessey, B. A. (2010). The creativity-motivation connection. The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2010, 342–365.

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

- Hong, J., Hou, B., Zhu, K., & Marinova, D. (2018). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation and employee creativity: The moderation of collectivism in Chinese context. Chinese Management Studies, 12(2), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-11-2016-0228

- Horng, J. S., & Lee, Y. C. (2009). What environmental factors influence creative culinary studies? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 21(1), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110910930214

- Horng, J. S., Tsai, C. Y., Yang, T. C., Liu, C. H., & Hu, D. C. (2016). Exploring the relationship between proactive personality, work environment and employee creativity among tourism and hospitality employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.004

- Houghton, J. D., & Dawley, D. (2015). Narrowing the creativity gap: The moderating effects of narrowing the creativity gap: The moderating effects of perceived support for creativity. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.548412

- Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.03.001

- Hülsheger, U. R., Anderson, N., & Salgado, J. F. (2009). Team-level predictors of innovation at work: A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1128–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015978

- Ismail, H. N., Iqbal, A., & Nasr, L. (2019). Employee engagement and job performance in Lebanon: The mediating role of creativity. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(3), 506–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2018-0052

- Israel, G. D. (1992). Determining sample size.

- Ivcevic, Z., Moeller, J., Menges, J. & Brackett, M. (2021), Supervisor emotionally intelligent behavior and employee creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 55, 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.436

- Kapadia, C., & Melwani, S. (2021). More tasks, more ideas: The positive spillover effects of multitasking on subsequent creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(4), 542–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000506

- Kebebe, E. (2019). Bridging technology adoption gaps in livestock sector in Ethiopia: A innovation system perspective. Technology in Society, 57, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.12.002

- Khalid, K., Abdullah, H. H., & Kumar, M. D. (2012). Get along with quantitative research process. International Journal of Research in Management, 2(2), 15–29.

- Khalili, A. (2016). Linking transformational leadership, creativity, innovation, and innovation-supportive climate. Management Decision, 54(9), 2277–2293. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2016-0196

- Kim, S., & Yoon, G. (2015). An innovation-driven culture in local government: Do senior manager’s transformational leadership and the climate for creativity matter? Public Personnel Management, 44(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026014568896

- Knief, U., & Forstmeier, W. (2021). Violating the normality assumption may be the lesser of two evils. Behavior Research Methods, 53(6), 2576–2590. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01587-5

- Kremer, H., Villamor, I., & Aguinis, H. (2019). Innovation leadership: Best-practice recommendations for promoting employee creativity, voice, and knowledge sharing. Business Horizons, 62(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.010

- Kršlak, S. Š., & Ljevo, N. (2021). Organizational creativity in the function of improving the competitive advantage of tourism companies in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Advanced Research in Economics and Administrative Sciences, 2(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.47631/jareas.v2i1.215

- Kwak, S. K., & Kim, J. H. (2017). Statistical data preparation: management of missing values and outliers. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 70(4), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2017.70.4.407

- Kwan, L. Y. Y., Leung, A. K. Y., & Liou, S. (2018). Culture, creativity, and innovation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117753306

- Lam, L., Nguyen, P., Le, N., & Tran, K. (2021). The relation among organizational culture, knowledge management, and innovation capability: Its implication for open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010066

- Lee, C., Hallak, R., & Sardeshmukh, S. R. (2019). Creativity and innovation in the restaurant sector: Supply-side processes and barriers to implementation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.03.011

- Li, W., Bhutto, T. A., Xuhui, W., Maitlo, Q., Zafar, A. U., & Ahmed Bhutto, N. (2020). Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 255, 120229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120229

- Lin, S.-H J., Chang, C.-H D., Lee, H. W., & Johnson, R. E. (2021). Positive family events facilitate effective leader behaviors at work: A within-individual investigation of family-work enrichment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(9), 1412–1434. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000827

- Lin, C. Y. Y., & Liu, F. C. (2012). A cross-level analysis of organizational creativity climate and perceived innovation: The mediating effect of work motivation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 15(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061211192834

- Liu, H. Y., Chang, C. C., Wang, I. T., & Chao, S. Y. (2020). The association between creativity, creative components of personality, and innovation among Taiwanese nursing students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100629

- Liu, X., Gong, S.-Y., Zhang, H., Yu, Q., & Zhou, Z. (2021). Perceived teacher support and creative self-efficacy: The mediating roles of autonomous motivation and achievement emotions in Chinese junior high school students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 39, 100752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100752

- Liu, D., Gong, Y., Zhou, J., & Huang, J.-C. (2017). Human resource systems, employee creativity, and firm innovation: The moderating role of firm ownership Georgia Institute of Technology The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Jia-Chi Huang. Academy of Management Journal, 60(3), 1164–1188. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0230