Abstract

The purpose of this research is to investigate what factors affect students’ readiness to start their own businesses once they graduate from university. A case study approach was conducted with an emphasis on an undergraduate degree program at a South African university. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with 15 program participants and analysed using a reflective theme analysis method. Our findings suggest that the experiential learning methodology employed at the university increases students’ levels of self-efficacy in the realm of entrepreneurship, i.e. their belief in their own abilities to create and run successful firms. They look at the benefits of going into business for themselves with optimism. However, our findings suggest that certain students may lack the confidence to take initiative to try entrepreneurship.\The major implication of these findings is that student readiness for entrepreneurship ventures is influenced by a multitude of factors which are beyond training. It is recommended that students participating in entrepreneurship programmes given support after graduation to realise their goals.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

There is a widespread consensus around the world that entrepreneurship is an essential component of a country progress and economic expansion (Bowmaker-Falconer & Herrington, Citation2020; Shambare, Citation2013). In general, entrepreneurial activity propels the economy toward greater productive capacity, makes a positive contribution to economic growth, and generates new employment opportunities (Mukwarami, et al., Citation2020; Yen et al., Citation2016). In response to this, a number of countries, including South Africa, have made entrepreneurship a fundamental part of their higher education programs (Lose & Khuzwayo, Citation2021). The promotion of entrepreneurial endeavours is one of the top priorities of economic policy in every country (Mukhtar et al., Citation2021), since it plays a significant part in both the maintenance and expansion of economic activity (Izadi & Rezaei-Moghaddam, Citation2017; Mukhtar et al., Citation2021). According to Masha (2020), the majority of young people who have ideas for possible enterprises do not have the competence or ability to transform such ideas into profitable businesses.

Numerous nations have each settled on their own distinct approaches to the instruction of aspiring businesspeople (Cheteni & Umejesi, Citation2023). However, questions have been asked about the calibre of the education provided by higher education institutions [HEIs] with reference to business startups and management. Although research has shown that education about entrepreneurship is associated with the growth of entrepreneurial skills and the motivation to engage in entrepreneurship, countries like South Africa still record low early-stage entrepreneurship intentions [TEA]. This is because entrepreneurship education is associated with the development of entrepreneurial skills (Franco et al., Citation2010; Bowmaker-Falconer & Herrington, Citation2020). Because the TEA in South Africa is relatively low, there is a pressing need to analyse the efficacy of entrepreneurship education in developing entrepreneurial readiness among students graduating from higher education institutions (HEIs) in the country. It is vital to establish the necessity of improving entrepreneurial education in order to ensure that desired economic growth may be accomplished, and this is essential to do so. This is especially important in rural communities, such as those that characterise the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa, where most of the population lives in rural areas. When compared to urban provinces, these communities have significantly greater rates of poverty, unemployment, and social marginalisation (Cheteni et al., Citation2019).

There is currently no causal evidence examining the efficacy of Entrepreneurship Education (EE) for youth or ‘potential future entrepreneurs’. The current empirical foundation of the field consists of observational studies (Brown et al., Citation2011; Von Graevenitz et al., Citation2010) and quasi-experimental studies (Brown et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, almost all of these published studies were carried out in the developed world. Meanwhile, Byabashaija and Katono (Citation2011) study in Uganda stands as the only notable study on entrepreneurship education in the sub-Saharan region. This study is one of the first to investigate the effects of EE on youth and young adults in a developing context and it will shed light on the effect of entrepreneurship pedagogy in one university.

Earlier studies of the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and factors like subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and attitude have mostly focused on these three areas (Alshebami et al., Citation2020). However, the importance of Entrepreneurship Education (EE) as a predictor of entrepreneurial endeavours has received less focus. In addition, researchers from the sub-Saharan region have not focused on this important issue, despite a growing body of evidence indicating that entrepreneurship can increase community income and well-being in developing countries by providing new jobs and economic success (Mukhtar et al. Citation2021).

This paper contributes to two areas. Firstly, it delves To begin, there is an acknowledgement of the role that youth have historically played in the realm of entrepreneurship. Second, there is a recognition of the importance of youth participation in business. Thirdly, there is an emphasis on indigenous youth as the target demographic for the placement of entrepreneurship in rural settings. One of the claims that will be made in this paper is that one of the benefits of entrepreneurship is that it has the potential to eradicate poverty. This claim is made although it is generally accepted that entrepreneurship is responsible for the creation of jobs and for economic development (Bugwandin & Bayat, Citation2022).

Therefore, the purpose of the study was to investigate the connection between receiving an education in entrepreneurship and developing entrepreneurial intentions after graduation. The low TEA observed in South Africa has continued to be a source of worry, especially in light of the necessity of expanding education on entrepreneurship to promote economic growth. This is a case study of a rural university offering entrepreneurship education as part of its curriculum in South Africa.

2. Entrepreneurial readiness

The idea of being ‘entrepreneurial ready’ has been investigated using a wide variety of research approaches. Both entrepreneurial intentions (Mohani et al., Citation2019; Malabana & Swanepoel, Citation2019) and the rate of entrepreneurial activities are closely related concepts that have been considered synonymous with entrepreneurial readiness. This presents a challenge when taking into account the assertion made by Siivonen, Peura, Hytti, Kasanen, and Komulainen (Citation2019) that universities have become key economic drivers as a result of their role in the development of aspiring business owners and the conduct of research with economic value. According to the findings of Malebana (Citation2019), exposure to entrepreneurial education was found to have a positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention behaviour. It is customary practice to think of entrepreneurial intention behaviour in terms of a person’s desire to pursue entrepreneurship as a career path as well as the individual’s possession of a powerfully positive attitude toward engaging in entrepreneurial behaviour. According to Mars and Rhoades (Citation2012), the concepts of entrepreneurial intentions and readiness are effective if the entrepreneurs tend to adopt an agency view in which they see themselves as critical agents of social change. This view is necessary for entrepreneurs to have in order for the concepts to be effective.

2.1. Entrepreneurship education

‘Entrepreneurship education’ is simply an education for improving the skills of innovation and creativity. Entrepreneurship education has also been defined as an education that teaches about identifying business opportunities, allocating appropriate resources (such as finances, marketing, and human resources), and, most importantly, starting a new business (Kourilsky, Citation1995). According to Davidsson (Citation2004), entrepreneurship education is about teaching participants how to explore numerous opportunities and how to make good decisions about which ones to pursue. According to Jones and Iredale (Citation2010), university-level entrepreneurship education programs are primarily aimed at raising awareness and encouraging students to pursue entrepreneurship as a possible career path.

Many debates surround entrepreneurship education, specifically how education affects intention and its antecedents such as attitude toward behaviour, subjective norm, and perceived behaviour (Kirkley, Citation2017). According to some studies, entrepreneurship is not inherent, and teaching and training can help develop certain aspects of it (Cheng et al., Citation2009; Neck & Greene, Citation2011). They argue that entrepreneurship, like science, can be taught and developed in the same way. Kuratko (Citation2003) proposed new methods and paradigms for teaching entrepreneurship, thereby rejecting the notion that entrepreneurship is an inherent quality. Similarly, Mohani et al. (Citation2019) found that EE is important in building entrepreneurship traits amongst students.

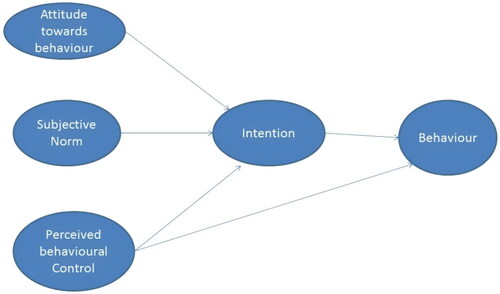

The study utilises Koch et al.’s (Citation2021) conceptual framework for entrepreneurship education, as shown in . EE is generally understood to refer to the entrepreneurship-related education and upbringing of children and young people. EE manifests itself primarily in systematic, intentional teaching and learning in general education schools and vocational (business) schools in South Africa and other countries, though elements of educational and learning processes in family and extracurricular contexts can be classified under the term (Cleveland & Bartsch, Citation2019). illustrates how the design of the EE in question can have a significant impact on the learning objectives and outcomes and how EE is integrated into the educational system (Koch et al., Citation2021). Educating about entrepreneurship aims to disseminate theories and characteristics about the entrepreneur, typical fields of action, and the entrepreneurial role in the economy and society, while educating for entrepreneurship aims to prepare for entrepreneurial activity in the sense of a direct start-up qualification (Lackeus, Citation2015). ‘Educating through entrepreneurship’ is the third strategy, and it involves guiding students through and outperforming entrepreneurial processes, often through business games or business plan competitions (Lackeus, Citation2015).

Figure 1. Variants of (youth) entrepreneurship education (Koch et al., Citation2021).

First, this type of education has close ties to the already established goals of South African education. They are geared toward helping each student grow into a fully functional, self-actualized adult and are grounded in a neo-humanist theory of education. Entrepreneurship, which places particular emphasis on the subject of education (Koch et al., Citation2021), can play a role in this context because it is concerned with imparting to students fundamental abilities related to substantial ways of thinking, acting, and problem-solving in accordance with formal educational theory. Common entrepreneurship education often provides students with information and training that is only marginally useful in the context of actual future business ventures. These skills and capacities are also important when addressing everyday challenges, such as those we face in the areas of climate change, the environment, and resource depletion.

2.2. Theoretical framework

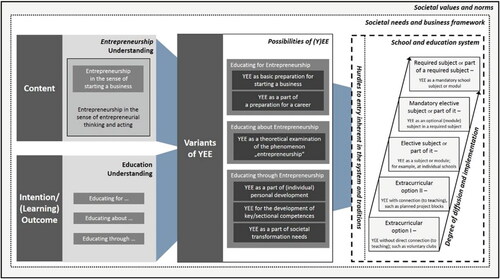

illustrates the theory of planned behaviour as proposed by Azjen. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TBP, 1987) by Icek Ajzen has been the primary theoretical framework that has guided the evaluation of youth entrepreneurship education programs (EEPs). The majority of EEP evaluations are theoretically underpinned by Ajzen’s theory. The idea that entrepreneurial attitudes, such as perceived desirability and perceived behavioural control, come before intention is at the heart of this theory. According to the model’s application to the field of entrepreneurship, perceived desirability is the degree to which a person finds the idea of starting a business appealing, and perceived behavioural control is equivalent to one’s perception of one’s own entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Last but not least, it is thought that entrepreneurial intention—defined as the desire to launch one’s own business—is one of the best indicators of future entrepreneurial behaviour (Elmuti et al., Citation2012). As a result, it can be said that TPB is an appropriate theoretical model to illustrate and anticipate entrepreneurial intentions for business ventures given the wide variety of learning outcomes it has produced.

Another intriguing suggestion about the connection between Perceived Behavioural Control and intention and behaviour is made by Elmuti et al. (Citation2012) in a theoretical article. They contend that entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the process by which each person starts a business are directly related. Notably, the association between self-efficacy and intention may be to blame for growing entrepreneurship intention (Wilson et al., Citation2007). A belief in one’s ability to successfully carry out the various roles and responsibilities involved in entrepreneurship is known as entrepreneurial self-efficacy (McGee et al., Citation2009). Entrepreneurial intentions are sparked by self-efficacy (Caiazza et al., Citation2016; Elmuti et al., Citation2012). Ajzen’s model is illustrated in .

3. Methodology

The research philosophy known as ‘interpretivism’, which maintains the ontological view that reality can be interpreted from the views and perspectives of social actors in certain circumstances, served as the foundation for the study. This philosophy holds the ontological view that reality can be interpreted from the views and perspectives of social actors in certain circumstances (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). To put it another way, as people progress through life and come across a variety of phenomena that pique their interest, they develop their own unique interpretations of the world around them. Interviews are a common way to gather information about phenomena because they give participants the opportunity to discuss not only themselves but also their points of view on the phenomenon that is being discussed (Bordens & Abbott, Citation2018).

The research was conducted in the context of a South African university that offers programs in entrepreneurship. A Higher Education Institution (HEI) in the Eastern Cape province was selected for sampling using a purposive sampling criteria. To begin, the university was representative in that it is located in a non-urban area and offers general entrepreneurship education. Among these were the institution’s geographical isolation, its incorporation of entrepreneurial modules into required coursework, and the relatively large numbers of students enrolled in its entrepreneurship programs. The research project was conducted as a rich, detailed qualitative ethnographic field study to examine the entrepreneurial processes as experienced by the students in situ (Eberle & Maeder, Citation2016). Interviews were used to collect data from 15 students who had recently graduated from an entrepreneurship programme that the university offers. There were a total of seven classes, with 371 students enrolled. The interviews were chosen over surveys because the aim was to get insights into how the entrepreneurship program contributed to their intentions of being entrepreneurs. Furthermore, interviews offer more valuable data that would not have been achieved with surveys given their nature (Creswell, Citation2015). The students were enrolled in an entrepreneurship program. The participants’ biographical information is provided in . The participants were given pseudonyms to avoid identification, for instance, P1 means participant 1 and so on.

Table 1. Demographical information of participants.

This study obtained an ethical clearance certificate, which is required by all institutions of higher learning. This was accomplished by satisfying the requirements of a research ethics committee at the institution where the researchers work (Sefotho, Citation2022). We obtained informed consent from each of the 15 entrepreneur students prior to the start of data collection, and we gave them the option of deciding whether they wanted to continue taking part in the research (Okeke, et al., Citation2022). We protected all of the participants by assuring them of their right to confidentiality and anonymity. This was accomplished by adhering to the principle of non-maleficence (Babbie, Citation2012).

3.1. Data analysis

The objective was to investigate the connection between receiving an education in entrepreneurship and developing entrepreneurial intentions after graduation. As a result, all interviews were openly and selectively coded by one researcher and discussed with the other members of the research team to establish a reliable coding system in accordance with grounded theory principles. The codes were then classified and clustered to identify higher-level attributes. A reflexive thematic analysis approach was used to analyse the gathered data. Analysing patterns and themes in qualitative data is made much simpler with the help of reflexive thematic analysis, a method that is both accessible and theoretically malleable (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). In the reflexive TA approach, the researcher is seen as an active participant in the knowledge-creation process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The researcher’s interpretations of the meaning patterns across the dataset are represented by the codes. As a reflection of the researcher’s interpretive analysis of the data, reflexive thematic analysis is conducted at the nexus of (1) the dataset, (2) the theoretical assumptions of the analysis, and (3) the analytical skills and resources of the researcher (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Using the same approach, we were able to identify different association types that the attributes can describe by mapping five themes (cultural, resources, psychological, models, and systems).

4. Analysis and findings

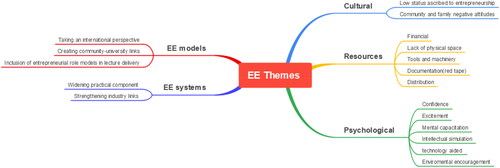

The framework of analysis presented in provides a summary of the main themes and patterns across certain categories and subcategories, which are important for an adequate appreciation of the relationship between entrepreneurship education and readiness to engage in entrepreneurship after graduation. NVivo software was used for analysis.

provides theoretical direction for the real and lived experiences of the respondents. The codes provided were then considered to establish categories and themes based on observable data patterns. Five codes were extracted from the participants’ data.

Table 2. Initial coding of data extracts.

It should be noted that the constant comparison technique originated in grounded theory and is often conducted together with other grounded theory strategies, which include theoretical sensitivity. This technique involves the recognition of concepts and cases for more detailed analysis, as they are likely to be central in deducing emerging theories. As expounded in Kolb (Citation2012), when employing the comparative analysis strategy, important codes are first deduced from a data set using purposeful and systematic coding. To establish the relationship between receiving entrepreneurship education and readiness to engage in entrepreneurship, a sampling of relevant phrases that reflected the views and opinions of students was necessary.

A majority of the students that were interviewed agreed that the entrepreneurship module has opened up their mindset and views about entrepreneurship. P5 and P7 affirm that the module opened their mindset and showed them that they can be self-dependent. However, P7 states that readiness can only be attained if an EE is taught as a package with practical and funding provided. He further laments that incubation of an entrepreneurship idea can be achieved in one university. The fact that both respondents use the word ‘mindset’ is intriguing because it suggests that being an entrepreneur was once seen as unattainable or unrealistic. This is consistent with previous research (Palmer et al., Citation2021) showing that entrepreneurship education boosts self-efficacy by giving them practical skills and experience that prepare them to start their own businesses.

A similar view was held by P12, who stated, ‘Readiness can only be attained if there is practical work related to the aspects of entrepreneurship’. Thus, P6 notes that as much as they are mentally capacitated by the module, a key question is why entrepreneurship is not taught by entrepreneurs. Such views are dominant in the module because students believe that the person who once travelled a rough road is the most suitable to advise others on how to navigate it.

On the other hand, P8 feels that while the modules have equipped them with the necessary skills, the family expects him to be working elsewhere. In his own words, ‘Only a few can appreciate me going to a university and then coming back to struggle again’. What this view tells us is that entrepreneurship is not seen by families or communities as something sustainable or something that can drive them out of poverty. This view is the norm, especially in the rural areas where the participants come from. There is a concern that parents send their children to attain certificates and degrees so that they can work in the public sector. However, given that entrepreneurship is a risky business opportunity, it is understandable why families or communities feel the way they do.

Participant P4 put it bluntly: ‘I am not ready to engage in entrepreneurship after graduation because I foresee challenges’. The student goes on to state that challenges such as funding, equipment, and office space are some of the issues that need to be addressed. While these views are true, entrepreneurship involves navigating such terrain and making it someday. Therefore, as pointed out by Cheteni and Umejesi (Citation2022), entrepreneurs in rural areas of South Africa would rather not pursue a venture if the risks were seen as high. Thus, the students who were interviewed are from similar communities in South Africa.

A student (P2) described the module as ‘a slap in the face because we had invested so much time into it, despite understanding the rationale behind the rejection’, in an interview with the class. The interview probes for more insight into how they make sense of the content. Despite the apparent truth of this reasoning, students have a harder time wrapping their heads around the dynamic forces impacting their process. As a result, various explanations are put forth by the students as to why things went wrong after graduation.

4.1. Discussions

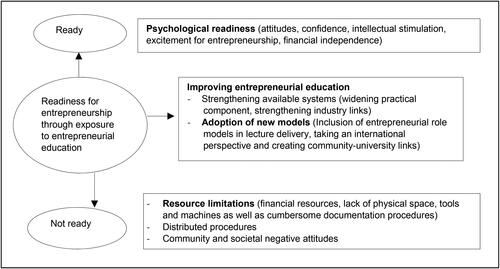

This study, as in Lose and Khuzwayo (Citation2021), has found that the practical component of entrepreneurial education is essential to realising the desired outcomes from entrepreneurial education. Respondents felt that practical work should be strengthened within the entrepreneurship modules. In this study, it was found that readiness to engage in entrepreneurship among students is likely to be achieved under circumstances of strengthened practical exposure. A dichotomy of views emerged from this study, with some students describing themselves as ready while others felt not ready, which relates to Shambare’s (Citation2013) findings that students often possess optimistic and pessimistic views of entrepreneurship education. This study further found that readiness to engage in entrepreneurship is affected by factors such as family history or background as well as the nature of communities of origin. Shambare (Citation2013) commented that exposure to entrepreneurship education does not usually guarantee that students will engage in entrepreneurship.

This study supported this position and found that a considerable number of respondents preferred the financial security associated with paid employment as opposed to earned finances. This study also found that it is essential to ensure that the learning environment in higher education is favourable and capable of stimulating entrepreneurial creativity. These observations are also shared by Roman and Maxim (Citation2017), who noted that some higher education environments can be stimulating for the emergence of entrepreneurially oriented graduates. Furthermore, the study found the need to ensure that entrepreneurship education is accepted and valued in the community in order to foster change in students’ attitudes. It has been observed that students feel that there is a need to strengthen community links and networks that promote a holistic approach to promoting entrepreneurship.

These findings are consistent with Mars and Rhoades (Citation2012), who suggested that the higher education system should foster an agentic perspective in which universities and students see themselves as important agents of social change. This is important as it translates to ensuring that universities and students lead in notable matters of development. The students also shared some views on what can be done to improve the entrepreneurial education system in South African HEIs. Respondents felt that the system should include community personnel and entrepreneurial role models who can inspire students in order for them to become more equipped to pursue an entrepreneurial career. Another important finding from the data collected is the need to create a centralised entrepreneurship system that combines all important role players, such as funders, business incubators, and government departments so that students receive a hybrid entrepreneurship system that makes them fully prepared as they graduate. summarizes the key findings of this study.

4.2. Theoretical implications

Conceptualising and empirically testing the antecedents of students’ entrepreneurial readiness, this study provides insights that theoretically enhances the discourse on entrepreneurial readiness. Therefore, this study provides empirical evidence that emphasises the significance of students’ perceptions of the quality of entrepreneurial education and the competence of the teaching staff in propelling students toward an entrepreneurial mindset. It has been empirically shown that student readiness for entrepreneurship increases when professors are enthusiastic about teaching the course, encourage students to engage in entrepreneurial-related activities and model entrepreneurial behaviour themselves. Extant literature generally agrees that a competent lecturing team correlates with students who are ready to start their own businesses, so this finding is not surprising (Bignotti & Le Roux, Citation2016). South African schools can improve students’ access to business by bolstering teachers’ skills through activities like career fairs and talks with local business owners.

Growth in university-based entrepreneurial endeavours has been the subject of increasing scholarly interest over the past three decades around the world (Ferreira et al., Citation2019). They go on to say that these ‘entrepreneurial universities’ are actively seeking out opportunities to make a positive impact on the economy beyond their core competencies of teaching and research. This new research bolsters the idea that universities are becoming more comfortable with their role as stimulators of entrepreneurial drive and economic growth. Turpin and Garrett-Jones (Citation2000) and Etzkowitz, Webster, Gebhardt, and Terra (Citation2000) both point out that universities that want to be entrepreneurial need to take entrepreneurial action, and that universities’ roles are growing in importance as society’s knowledge production system evolves. Ferreira et al. (Citation2019) elaborate on the significance of this duty by identifying two primary ways in which entrepreneurial universities boost academic entrepreneurial capability: the development of practically skilled human capital and the dissemination of academic research findings to business. New understandings revealed by this investigation confirm and expand upon the aforementioned premises. To begin, the authors of this study argue that innovative educational institutions can serve both the knowledge transfer needs of businesses and the creation of highly skilled human capital. To build upon this foundation, this study argues that academic entrepreneurial capability enhancement universities’ success depends on two main factors: the adequacy of their curriculum and course content and the competence of their lecturing team.

Finally, this study highlights the fact that in some cultural settings, ensuring adequate curriculum and course content and a competent lecturing team may not be enough to propel entrepreneurial ambitions. Interesting insights can be gleaned from analysing the distribution of responses to questions about entrepreneurial preparedness, the relevance and adequacy of the curriculum and course content, and the competency of the lecturing team. Even though they have high confidence in the curriculum, course content, and lecturing team’s ability, black African students reported a very low level of entrepreneurial readiness.

4.3. Policy implications

Several studies have highlighted the significance of entrepreneurship education, particularly due to the fact that there is a clear correlation between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship readiness (Gelaidan & Abdullateef, Citation2017). This study has important policy implications, one of which is that administrators and policymakers in charge of higher education should give serious thought to including entrepreneurship among the subjects taught at universities. As a result, our research provides some support for expanding entrepreneurship-related coursework in higher education. Policymakers and academic practitioners should collaborate to create curricula and course content that incorporate the relevant theoretical ingredients to motivate entrepreneurial drive and maximise its impact on economic development. Particular focus should be given to ensuring the curriculum and course contents are relevant and adequate to maximise the motivational impact of the entrepreneurial mindset. Fundamentally, we need to embrace incentives that facilitate learning and help students gain a deeper understanding of how to apply entrepreneurial principles in real-world situations. Universities in South Africa also need to recruit and retain highly qualified faculty to conduct the course of study. The findings of this research have also shown that cultural factors tend to affect individuals’ propensity to take an entrepreneurial tack. That reality warrants attention from policymakers as well.

5. Conclusion

The motivation for this research was the need to evaluate how well HEIs are preparing their students for entrepreneurial endeavours. According to the interviews conducted for this research, some students believe they are mentally prepared to be entrepreneurs but are hindered by a lack of opportunities to gain practical experience in entrepreneurship. In order to be more prepared to engage in entrepreneurship, respondents believe they need strong industry links and exposure to practical tasks. It is suggested that HEIs implement the recommendations provided in this study, such as the need to expand the practical elements of entrepreneurial education and to heavily involve the community to alter mindsets and elevate the standing of small business owners. This is essential for students to learn the value of self-employment over traditional employment.

Areas of future research include studying the psychological factors and cultural factors that influence or affect entrepreneurship readiness among students and graduates, especially those residing in a rural setting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thobekani Lose

Dr. Thobekani Lose is the manager and researcher at Water Sisulu University’s Centre for Entrepreneurship Rapid Incubator (CFERI), where he applies the knowledge and skills he acquired from his four-year stint at Small Development Agency (SEDA). Dr. Lose has academic qualifications in Business Management, including a Doctorate in Business from Vaal University of Technology (VUT), a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), and a Bachelor’s degree in Entrepreneurship Management (CPUT). Dr. Lose has 11 years of experience in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, including development and lecturing on business management.

Priviledge Cheteni

Dr. Priviledge Cheteni is a researcher at Walter Sisulu University’s Centre for Entrepreneurship and Rapid Incubation. He earned a PhD in Economics from North West University in South Africa. Dr. Cheteni has chaired several business tracks and presented at numerous professional conferences. His work has been published in a number of peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings. Throughout his career, he has published a number of papers in prestigious national and international journals. He has led several Local Government Sector Education and Training Authority projects, including the Middle Management and Professionals Research Project and the Leadership Research Project (LGSETA) (LGSETA). His most recent publications are about entrepreneurship, indigenous knowledge systems, public leadership, and sustainability.

Reference

- Alshebami, A., Al-jubari, I., Alyoussef, I., and Raza, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial education as a predictor of community college of Abqaiq students’ entrepreneurial intention. Management Science Letters, 10, 3605–3612. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.033

- Babbie, E. (2012). The Practice of Social Research (13th ed.). Wadsworth.

- Bignotti, A., & Le Roux, I. (2016). Unravelling the conundrum of entrepreneurial intentions, entrepreneurial education, and entrepreneurial characteristics. Acta Commercii, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v16i1.352

- Bordens, K. S., & Abbott, B. B. (2018). Research Design and Methods: A Process Approach (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., & Herrington, M. (2020). Igniting Startups for Economic Growth and Social Change. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 Report. https://www.gemconsortium.org/news/igniting-startups-for-economic-growth-and-social-change-in-south-africa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Brown, S., Mchardy, J., McNabb, R., & Taylor, K. (2011). Workplace performance, worker commitment and loyalty. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 20(3), 925–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2011.00306.x

- Bugwandin, V., & Bayat, M. S. (2022). A sustainable business strategy framework for small and medium enterprises. Acta Commercii, 22(1), 1021. ac.v22i1.1021 https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v22i1.1021

- Byabashaija, W., & Katono, I. (2011). The impact of college entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions to start a business in Uganda. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 16(01), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1142/S108494671100176

- Caiazza, R., Foss, N., & Volpe, T. (2016). What we do know and what we need to know about knowledge in the growth process. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 3(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-03-2016-0022

- Cheng, M., Y., Chan, W. S., & Mahmood, A. (2009). The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in Malaysia. Education + Training, 51(7), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910910992754

- Cheteni, P., Khamfula, Y., & Mah, G. (2019). Gender and poverty in South African rural areas. Cogent Social Sciences, 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1586080.

- Cheteni, P., & Umejesi, I. (2022). Evaluating the sustainability of agritourism in the Wild coast region of South Africa. Cogent Economics and Finance, 1(1), 1–22.

- Cheteni, P., & Umejesi, I. (2023). Application of indigenous knowledge and sustainable agriculture by small-scale farmer households and entrepreneurs in South Africa. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 12(1), 1–18.

- Cleveland, M., & Bartsch, F. (2019). Global consumer culture: epistemology and ontology. International Marketing Review, 36(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2018-0287

- Creswell, J. W. (2015). An Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Sage. Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Consortium.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Davidsson, P. (2004). Researching Entrepreneurship. Springer.

- Eberle, T., & Maeder, C. (2016). Organizational ethnography. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Elmuti, D., Khoury, G., & Omran, O. (2012). Does entrepreneurship education have a role in developing entrepreneurial skills and ventures ‘ effectiveness? Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 15, 83–99.

- Etzkowitz, H., Webster, A., Gebhardt, C., & Terra, B. R. C. (2000). The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of the ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy, 29(2), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00069-4

- Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., & Kraus, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship research: mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Review of Managerial Science, 13(1), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0242-3

- Franco, M., Haase, H., & Lautenschläger, A. (2010). Students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An inter-regional comparison. Education + Training, 52(4), 260–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011050945

- Gelaidan, H. M., & Abdullateef, A. O. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions of business students in Malaysia: The role of self-confidence, educational and relation support. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-06-2016-0078

- Izadi, H., & Rezaei-Moghaddam, K. (2017). Accelerating components of the entrepreneurship development in small agricultural businesses in rural areas of Iran. Technical Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 7(1), 6–15.

- Jones, B., & Iredale, N. (2010). Viewpoint: Enterprise Education as Pedagogy. Education + Training, 52(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011017654

- Kirkley, W. W. (2017). Cultivating entrepreneurial behaviour: entrepreneurship education in secondary schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-04-2017-018

- Koch, L. T., Braukmann, U., & Bartsch, D. (2021). Schulische Entrepreneurship Education – quo vadis Deutschland? Plädoyer für einen Perspektivenwechsel. Zeitschrift Für KMU Und Entrepreneurship (ZfKE), 69(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.3790/zfke.69.1.37

- Kolb, S. M. (2012). Grounded Theory and the Constant Comparative Method: Valid Research Strategies for Educators. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 3, 83–86.

- Kourilsky, M. (1995). Entrepreneur education: Opportunity in search of curriculum. Business Education Forum. 1–18.

- Kuratko, D. (2003). Entrepreneurship Education: Emerging Trends and Challenges for the 21st Century White Papers Series, Coleman Foundation, Chicago, IL.

- Lackeus, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship in Education—What, Why, When, How. Entrepreneurship Background Paper OECD, France.

- Lose, T., & Khuzwayo, S. (2021). Technological perspectives of a balanced scorecard for business incubators: Evidence from South Africa. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 19(4), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.19(4).2021.04

- Malabana, M. J., & Swanepoel, E. (2019). Graduate entrepreneurial intentions in the rural provinces of South Africa. Southern African Business Review, 19(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.25159/1998-8125/5835

- Malebana, M. J. (2019). The influencing role of social caliital in the formation of entrelireneurial intention. Southern African Business Review, 20, 51–70. https://doi.org/10.25159/1998-8125/6043

- Mars, M. M., & Rhoades, G. (2012). Socially oriented student entrepreneurship: A study of student change agency in the academic capitalism context. The Journal of Higher Education, 83(3), 435–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2012.11777251

- Mohani, A., Azmawani, A., Rahman, M. Y., & Rahman, M. M. (2019). Entrepreneurial characteristics and intentions among undergraduates in Malaysia. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 15(5), 560–574. https://doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2019.10025121

- McGee, J., Peterson, M., Mueller, S., & Sequeira, J. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(4), 965–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00304.x

- Mukhtar, S., Ludi, L. W., Wardana, W., Wibowo, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2021). Does entrepreneurship education and culture promote students’ entrepreneurial intention? he mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1918849

- Mukwarami, S., Mukwarami, J., & Tengeh, R. K. (2020). Local economic development and small business failure: the case of a local municipality in South Africa. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 25(4), 489. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2020.109114

- Neck, H. M., & Greene, P. G. (2011). Entrepreneurship education: Known worlds and new frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00314.x

- Okeke, M. N., Osuachala, C. F., & Umeakuana, C. A. (2022). Work-life balance and female employee performance in Anambra state Deposit Money Banks. International Journal of Business & Law Research, 10(4), 34–46.

- Palmer, C., Fasbender, U., Kraus, S., Birkner, S., & Kailer, N. (2021). A chip off the old block? The role of dominance and parental entrepreneurship for entrepreneurial intention. Review of Managerial Science, 15(2), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00342-7

- Roman, T., & Maxim, A. (2017). National culture and higher education as pre-determining factors of student entrepreneurship. Studies in Higher Education, 42(6), 993–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1074671

- Sefotho, M. P. M. (2022). Ubuntu translanguaging as a systematic approach to language teaching in multilingual classrooms in South Africa. Journal for Language Teaching, 56(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.56285/jltVol56iss1a5416

- Shambare, R. (2013). Barriers to Student Entrepreneurship in South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 5(7), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v5i7.419\

- Siivonen, P. T., Peura, K., Hytti, U., Kasanen, K., & Komulainen, K. (2019). The construction and regulation of collective entrepreneurial identity in student entrepreneurship societies. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(3), 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-09-2018-0615.

- Turpin, T., & Garrett-Jones, S. (2000). Mapping the new cultures and organization of research in Australia. In Weingart, P. and N. Stehr (Eds.), Practising interdisciplinarity (pp. 79–114). University of Toronto Press.

- Von Graevenitz, G., Harhoff, D., & Weber, R. (2010). The effects of entrepreneurship education. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(1), 90–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2010.02.015

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00179.x

- Yen, N. T., Rohaida, S., & Zainal, M. (2016). Synergistic high-performance work system and perceived organizational performance of small and medium- sized enterprises: A review of literature and proposed research model. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 7(11), 145–154.