Abstract

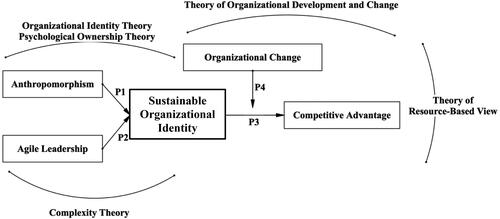

This research aims to build model and proposition of establishment of sustainable organizational identity. This research determines anthropomorphism and agile leadership as antecedents of sustainable organizational identity. This research also determines competitive advantage as consequence of sustainable organizational identity establishment. Furthermore, this research determines organizational change as moderating variable between sustainable organizational identity and competitive advantage. The model is, generally, built based on RBV. This research concludes that theoretical model and previous studies can identify that anthropomorphism and agile leadership can be hypothesized and examined empirically in the future to determine sustainable organizational identity. This research also conclude that sustainable organizational identity can be hypothesized and examined empirically in the future to determine competitive advantage. Furthermore, this research conclude that change management can be used as moderating variable between sustainable organizational identity and competitive advantage. This research contributes to the development of the concept of sustainable organizational identity symbolization, especially in conceptualizing the theory. This research limits to model and proposition formulation without empirical study because of the limitation of questionaries of sustainable organizational identity. Future research is expected to formulate questionaries of sustainable organizational identity so the empirical study can be performed.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Dutton et al. (Citation2014) in their research stated that the picture of organizational identity for each member is unique. Several studies have contributed to understanding the concept of how organizational members perceive the organization, and how they relate to its characteristics (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985; Balmer et al., Citation2007; Balmer & Greyser, Citation2002; Gioia et al., Citation2000, Citation2013; Hatch & Schultz, Citation1997; Whetten, Citation2006). Organizational identity is a root construct in organizational phenomena (Whetten, Citation2006). The organizational identity conception rests on core assumptions drawn from organization theory and identity theory (Whetten & Mackey, Citation2002); rooted in the exploration of identity at the individual, group, and organizational levels (Puusa, Citation2006).

In recent decades, researchers have taken an interest in organizational identity, as evidenced by the significantly increased amount of research on organizational identity issues (Albert et al., Citation2000; Corley et al., Citation2006; Haslam & Ellemers, Citation2005; Schultz et al., Citation2000). Cornelissen et al. (Citation2007) reveal that the reasons for interest in identity domains and literature have historically been quite diverse. These include preoccupation with visual design and logos and customer reactions to organizational identification (in marketing), social categorization of individuals (in social and organizational psychology), integration of visual identities (in corporate communications and marketing), institutionalized culture and organizational performance (in strategy), understanding and motivation of employees (in management and organizational behavior).

The understanding of organizational identity can be seen through two traditional and phenomenological perspectives. Starting from a traditional perspective by Albert and Whetten (Citation1985), organizational identity is defined as something central, enduring, and distinctive (CED); associated with how members understand the organization (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985; Balmer et al., Citation2007; Balmer & Greyser, Citation2002; Gioia et al., Citation2000, Citation2013; Hatch & Schultz, Citation1997; Whetten, Citation2006). From a phenomenological perspective, organizational identity can be seen as an interpretive system, or as a set of shared behaviors (Brickson, Citation2005).

Furthermore, organizational identity is seen as a cognitive self-definition or self-representation adopted by organizational members that are deeply embedded and hidden (Fiol & Huff, Citation1992). Organizational identity is assumed to be a collective understanding of the organization, its unique values, and its characteristics (Hatch & Schultz, Citation1997). Organizational identity is a collective manifestation that distinguishes it from personal views or self-understanding (Gioia et al., Citation2000). Furthermore, organizational identity refers to the core characteristics of the organization and the features that appear most relevant to internal stakeholders, such as organization members (Phillips et al., Citation2020). It can be concluded that organizational identity has been understood as “something” which broadly refers to what organizational members feel and think about their organization.

Albert and Whetten (Citation1985) pioneered the term CED which reinforces the concept that organizations and organizational identity are interrelated and complementary. The “central” feature, manifested as a key value, is considered an important aspect of the organization’s self-definition of “who we are” (Gioia et al., Citation2013). This concept distinguishes an organization from other similar organizations based on something essential. The criteria for "distinctive" (typical) by which the organization is seen as sufficiently eclectic include statements of ideology, philosophy, management, culture, and rituals (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). The key notion related to distinctiveness is the concept of "optimal distinctiveness" (Brewer, Citation1991); organizational identity is a collective understanding of the core features that distinguish organizations from other organizations (Gioia et al., Citation2000; Gray & Balmer, Citation1998). Organizations as entities in social space want to see themselves and be seen by others as unique, and different from other similar organizations (Corley et al., Citation2006). Organizational members need to believe that they have a distinct organizational identity, regardless of whether that belief is “objectively” verifiable (Gioia et al., Citation2013). From this description, it can be concluded that the uniqueness of IO will affect individual perceptions of the organization.

Furthermore, the criteria for "enduring" (enduring-lasting). The most controversial and the key to the importance of conducting this research. On this criterion, Albert and Whetten (Citation1985) positioned organizational identity as an enduring organizational property. Recently, however, academics have begun to question the idea of organizational identity as enduring. Scholars have become skeptical of the tendency to equate organizational identity with enduring features that represent organizations. Organizational identity is no longer claimed to be static but changes over time.

Starting from the findings of organizational identity from an impact perspective through the study literature, Czarniawska and Wolff (Citation1998) stated that an organization’s inability to align organizational identity with organizational conditions can affect an organization’s chances of survival. Organizational identity plays an important role in organizational survival and performance because an attractive organizational identity can increase the participation, support, and loyalty of organizational members, stakeholders, and other constituents (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989). Organizational identity serves as an organizational lens to interpret negative signals from outside for the organization to determine the appropriate resource allocation to manage these threats (Randel et al., Citation2009). It can be concluded that organizational identity is crucial for the organization.

Puusa (Citation2006) states that organizational identity can provide insight into the character and behavior of its members. Organizational identity is one of the key issues in the sense-making process of organizational members in high environmental turbulence (Kjærgaard, Citation2009). An aligned organizational identity allows organizational members to recognize the organization as part of themselves, not just a “stranger” (Gioia et al., Citation2010). Understanding self-identity owned by organizations and organizational members is explicitly a motivating force to engage in sustainable work (Baumgartner, Citation2009; Dutton & Dukerich, Citation1991; Pei, Citation2019; Verbos et al., Citation2007). Sustainable organizational identity is therefore heavily influenced by an organization’s approach to sustainable processes.

Melewar and Jenkins (Citation2002); Dowling (Citation2004) and Martínez et al. (Citation2014) stated that organizational identity must be properly managed on an ongoing basis to project a positive image of the organization to its members. Recent research on organizational identity by Frostenson et al. (Citation2022) argues that it is irrelevant to photograph organizational identity as something eternal because in its development all organizations tend to be non-static and complex. It is more appropriate to use the term that organizational identity is something that is "ongoing" or described as sustainable organizational identity. Sustainable organizational identity is an organizational concept that shows how members of the organization perceive, feel, and think about organizational commitment and achievements concerning sustainability (Frostenson et al., Citation2022).

This is supported by several studies with a dynamic view of organizational identity. Gioia et al. (Citation2000) argue that there is a reciprocal relationship between organizational identity and image, which implies that organizational identity does not have to last long but can change over time. Organizational identity is not eternal or enduring, but is something unstable, adaptive, and sustainable (Gioia et al., Citation2002; Tierney, Citation2001). Organizational identity has a dynamic character and optimization is seen as a continuous construction of the relationship between self, organization, and work (Alvesson et al., Citation2008; Alvesson & Empson, Citation2008). Organizational identity has more to do with how to express, reflect, and claim not only as special features that last a long time and look distinctive (Schultze & Trommer, Citation2012). Organizational identity is not static created from a complex state (Baumgartner, Citation2009; Onkila et al., Citation2018; Verbos et al., Citation2007).

Irshad and Bashir (Citation2020) also find that there is a dark side of organizational identity that promotes unethical behavior. Naseer et al. (Citation2020) also suggest that organizational identity can affect negative emotional among employees. Caprar et al. (Citation2022) explains that dark side of strong organizational identity comes from the unclear of comprehensive concept organizational identity. Some studies find that organizational identity can reduce cooperation (Y. Li et al., Citation2015; Polzer, Citation2004), increase work-family conflict (Li et al., Citation2015), provide resistance to change (van Dijk & van Dick, Citation2009), and promote psychological entitlement (Naseer et al., Citation2020).

In the discussion that has developed and follows the interest in sustainability in contemporary business, it is concluded that “sustainability” is an aspect of organizational identity construction (Chong, Citation2009; Frandsen, Citation2017; Glavas & Godwin, Citation2013; Onkila et al., Citation2018; Simões & Sebastiani, Citation2017). Sustainability in organizational identity is an important element of strategy and change in organizations (Balmer & Greyser, Citation2002; Balmer & Soenen, Citation1999; Cornelissen & Elving, Citation2003; Fukukawa et al., Citation2007). The issue of sustainability greatly impacts organizational identity, but that does not mean that sustainable organizational identity has been clearly defined or disputed (Onkila et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it can be concluded that organizational identity is not something that is static or lasts a long time but is related to ongoing construction between individuals and groups within the organization. The meanings and interpretations of organizational identity will almost certainly change over time, which is a very important critique in considering the role of sustainability.

Further, the description above is associated with research references from Ashforth et al. (Citation2011) and supported by Carlsen (Citation2016) regarding how sustainable organizational identity is formed and implies an understanding of how the nature and reasons for construction produce a strong sustainable organizational identity. Where "strong" means being self-understanding explicitly by members of the organization (both leaders and members) with the strength of motivation for further involvement in ongoing work (Baumgartner, Citation2009; Dutton & Dukerich, Citation1991; Pei, Citation2019; Verbos et al., Citation2007). Through a ‘bottom-up’ perspective it is possible to identify what influences sustainable organizational identity development (Ashforth et al., Citation2020). Supported by the application of the concept at multiple levels of analysis and its capacity to integrate analytical insights at the micro, meso, and macro levels further underscores the potential of sustainable organizational identity. That is, with an understanding of organizational identity as something that is built socially, especially with internal constituents within the organization, it makes sense when organizations try to build sustainable organizational identity. Therefore, it becomes important to build a dynamic and flexible continuous organizational identity for the future benefit of the organization.

From this background, research is needed to understand how the antecedents, moderation or mediation, and the consequences of sustainable organizational identity are formed. Alvesson and Empson (Citation2008) and Alvesson et al. (Citation2008) stated that in-depth research is needed on income and outcomes in the relationship between members, organizations, and work to deepen understanding of sustainable organizational identity. An internal organization-oriented approach is more appropriate for understanding sustainable organizational identity (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). Concluded from the description above, it becomes interesting to research to understand how sustainable organizational identity is formed and its implications in organizations. It is described in more detail by identifying the positive antecedents and consequences of a strong sustainable organizational identity construction, as well as how to strengthen IO and consequent relationships in a sustainable frame.

This research answers the challenge of Frostenson et al. (Citation2022) through sustainable organizational identity renewal in the antecedent, consequence, and moderation framework whose effects were tested concerning variable foci. This study uses variables that meet criteria such as non-static, dynamic, able to adapt to complex conditions, and are developed as distinctive and specific core competencies within the organization so that organizations can outperform competitors by doing things differently. These variables include anthropomorphism, agile leadership, competitive advantage, and change. This research model uses the RBV theory as an umbrella theory. Each hypothesis in this study will be supported by theory to reinforce the relationship between variables. These theories include organizational identity theory (Whetten, Citation2006), psychological ownership theory (Pierce et al., Citation2003), complexity theory (Klijn, Citation2008; Okwir et al., Citation2018), and organizational change and development theories (Lewin, Citation1951).

Shifting to the discussion of the variables used in this study. First, anthropomorphism, which is the attribution of human characteristics such as physical or human behavior (motivations, intentions, or emotions) to non-human entities, objects, and events (Chandler & Schwarz, Citation2010; Epley et al., Citation2008; Guthrie, Citation1993; Han et al., Citation2019; Waytz et al., Citation2010; Zhou et al., Citation2019). Eisenberger et al. (Citation1986) investigated why sometimes individuals have trouble describing their organizations and why employees want companies to care about their well-being?; how Southwest Airlines employees perceive their airline as not only “low cost” (what?) but also “friendly” (who?) (Gittell, Citation2002); why employees always expect companies to show affection to them (Dutton et al., Citation2014); how entrepreneurs in Indonesia describe their businesses as “babies” as an effort to create resilience in business (Paramita et al., Citation2022). These questions will be answered by anthropomorphism. It is easy and requires few social cues for individuals to spontaneously and unconsciously anthropomorphize (Miesler et al., Citation2010; Reeves & Nass, Citation1996). As stated by Gioia et al. (Citation2013), that identity at all levels touches on a fundamental need for all social actors to have a sense of "self" to articulate core values and act following deep-rooted assumptions about "what are we and who can we become?" Of these, it is relevant when placing anthropomorphism in the sustainable organizational identity literature.

This is reinforced by Dhalla’s (Citation2007) statement that organizational identity is the focal point and something unique to members of the organization and the organization itself. This study assumes that there is a high probability that sustainable organizational identity anthropomorphism gives attachment to the understanding of the organizational picture of organizational members from "what" to "who". It is this deep collective feeling as the color of the organization that is meant to be captured by the continuous organizational identity construction. In essence, organizational identity’s anthropomorphism offers new and important insights into how organizations engage organizational members to think, feel, and behave (Ashforth et al., Citation2020). Distinctive organizational character and sustainable organizational identity as targets of anthropomorphism will greatly impact (Dutton et al., Citation2014; Epley et al., Citation2008). From the description above, it is interesting to examine the effect of anthropomorphism as an antecedent of sustainable organizational identity.

The relationship between anthropomorphism and sustainable organizational identity can be explained by organizational identity theory (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). This theory explains that organizational identity has central, unique, and enduring characteristics. Anthropomorphism allows organizational members to understand their organization in terms of "who we are as an organization" (eg, personality, attitudes, influences) rather than "what is it or what are we?" (eg, industry, structure, age). Another theory that supports this hypothesis is the theory of psychological ownership. According to Pierce et al. (Citation2003), psychological ownership is a cognitive-affective construct (attitudes and feelings) in which individuals feel. Psychological ownership in an organizational context is a psychological experience in which employees develop ownership of a target. An important aspect of increasing the sense of psychological ownership is the closeness of the individual to the organization (Pierce et al., Citation2003). This is in line with the statement that the organizational identity humanization process can create engagement and interaction between organizational members and their organizations (Ashforth et al., Citation2020).

More on Another variable related to organizational identity is leadership. Several types of leadership are used, including transformational leadership (Hesar et al., Citation2019) environmental leadership (Chen, Citation2011) servant leadership (Akbari et al., Citation2014; Omanwar & Agrawal, Citation2022) collectivist leadership (Van den Broeck et al., Citation2016); and positive leadership (Ko & Choi, Citation2021) Where the role of the leader is important as a key to maintaining the organization (Ng’ethe et al., Citation2012) and influencing the efficiency and performance of an active and dynamic social system (Hesar et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Variables relate to organizational identity.

The selection of a leadership style in the rapidly changing conditions of the environment and the complexity of the situation is becoming an increasingly important issue and a strategic aspect in the application of a leadership style. Therefore, organizational leadership must be agile in dealing with the dynamics of a dynamic business environment by maintaining member engagement with the organization (Aitken & von Treuer, Citation2021). The importance of the nuances of sharing knowledge for organizations is undeniable (Chatwani, Citation2019). Defining knowledge as a dynamic human asset, expressed through agile leadership practices that define the color of the organization and link it to the organizational identity of sustainability is a way to account for human action as an agency within a non-static, dynamic, and complex organizational framework. So, it can be underlined that it is important to make the nuances of agile leadership as an antecedent of sustainable organizational identity as the basis for the flow of knowledge within the organization.

Complexity theory in organizations (Klijn, Citation2008; Okwir et al., Citation2018) will become a basic perspective in testing the effect of agile leadership on sustainable organizational identity. This theory reinforces the hypothesis that organizations are non-static, dynamic, and complex systems so organizational abilities as dynamic leaders are needed to manage problems within the organization. This is supported by the statement that organizations must concentrate on operating organizational systems and instilling creativity and innovation in a dynamic and complex business environment (Mendes et al., Citation2017).

Furthermore, from a consequential perspective, starting from the statements of Hatch (Citation2011) and Fiol (Citation2001) that symbols in the organizational context are an important source of creating an organizational identity that cannot be imitated and will positively influence competitive advantage. The ability of an organization to generate competitive advantage through distinctiveness is the result of a combination of internal organizational resources such as innovation and reputation which cannot be easily imitated by competitors (Kay, Citation2003). A strong organizational identity will add value, trust, and integrity to members, to increase the quality and satisfaction of organizational members which will have an impact on the sustainability of an organization’s competitive advantage (J. B. Barney et al., Citation1998).

Supported by the results of conceptual research from Rockwell (Citation2019) that when an organization must meet the criteria of being unique, intangible, and rare, there is no more suitable resource to play it than a sustainable organizational identity. An organizational identity that is dynamic and flexible allows organizations to build a profitable organizational identity in the future (Gioia & Thomas, Citation1996). The optimal impact of organizational identity will only occur if the organization has the key conceptual characteristics of being "centered, distinctive, and sustainable" Rockwell (Citation2019). From this description, it can be said that a strong and sustainable organizational identity will potentially benefit an organization’s competitive advantage.

This rationale for sustainable organizational identity relationships and competitive advantage is supported by the RBV theory because this theory focuses on the internal environment of organizations. This theoretical approach concludes that the main difference between a company’s performance in the market is the resources and capabilities of each organization that make an organization inimitable, non-transferable, and irreplaceable. Organizational internal strength significantly influences sustainable competitiveness, being one of the main producing factors of competitive advantage (Mintzberg & Rose, Citation2003).

Finally, and no less important in a sustainable context, organizational identity is always faced with non-static, dynamic, and complex conditions (Carlsen, Citation2016). Organizational change is a planned change that includes structure, strategy, human resources, and technology as a form of organizational response to strive to improve the organizational ability to adapt to environmental changes and seek changes in employee behavior in achieving competitive advantage (Rafferty & Griffin, Citation2006; Robbins, Citation2003). Therefore, organizational change needs to be considered as a factor that strengthens the relationship between sustainable organizational identity and competitive advantage. Evidence has accumulated over the last decade that the success of change efforts is not only due to their content or substantive nature but also the processes followed or actions were undertaken during their implementation (Hendry, Citation1996). Cummings and Mills statement supports that continuous change always occurs in organizations.

Content and process considerations view organizational change as a complementary element in planning and monitoring the organization. Organizational change is a strong field of study and continues to be responsive to contemporary organizational demands (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999). Thus, based on this description, whether sustainable organizational identity will be more optimally used as an internal organizational resource in achieving competitive advantage when changes are made in the organization will be an interesting thing to study.

In the relationship between constructs and moderation, the theory of development and organizational change (Lewin, Citation1951) is used as the rationale. Lewin’s theory is a classic theory in change management that is relied upon as the success of today’s organizations, where dynamic organizations change to adapt to various disruptions in the organizational environment. Changes that are oriented towards high involvement, commitment, and support in the change process will be a strong root in organizational success (Cummings & Worley, Citation2009).

This research contributes to the development of the concept of sustainable organizational identity symbolization, especially in conceptualizing the theory. Where previous research has mostly examined organizational identity from an individual perspective and its relation to the benefits of organizational identity to individuals dominated by two theories, namely identity theory and social identity theory (Hogg & Williams, Citation2000; Tajfel, Citation1974). While this research was carried out through the development of a sustainable organizational identity model with a different perspective, namely based on the theory of Resource-Based View (J. Barney, Citation1991; Wernerfelt, Citation1984) as the main research umbrella. Use of organizational identity theory (Whetten, Citation2006), psychological ownership theory (Pierce et al., Citation2003), complexity theory (Klijn, Citation2008; Okwir et al., Citation2018), and organizational change and development theory (Lewin, Citation1951) on each research proposition. Empirical support for these theories in the way of thinking about how the social world works through the involvement of the variables of anthropomorphism, agile leadership, competitive advantage, and organizational change is fulfilled.

2. Literature review and proposition development

2.1. Research of organizational identity

A literature review was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of the research on organizational identity. The bibliometric method is used which bases the findings on aggregate bibliographic data on the structure, social networks, and current interests (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Bibliometry includes statistical analysis of published articles and their citations in measuring impact (Maditati et al., Citation2018). The Publish or Perish (PoP) search engine is used in the article search. In line with the statement of Secinaro et al. (Citation2020) that the Scopus database can comprehensively evaluate scientific products; therefore, the potential to improve quality and reduce researcher bias in the literature review process is achieved. Scopus is recognized by experts as one of the best repositories of articles, the largest database, and impactful (Fornacciari et al., Citation2017; Vila et al., Citation2020). Such studies make it possible to synthesize past research and compare specific academic results (J. Li et al., Citation2020).

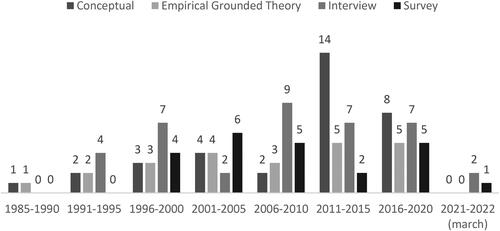

The first article with the theme of organizational identity published in 1985 was the forerunner of the initial understanding of organizational identity, and to dig up further information, articles were collected up to 2022 as the final analysis deadline. The search key uses the Title-Abs-Key with the words "Organizational OR Organizational AND Identity". Indicators regarding quality and impact factors are shown by citations from documents, journals, and universities (Ari et al., Citation2020). Taking into account the disciplines of knowledge and citation figures found 118 articles about organizational identity in the field of management science.

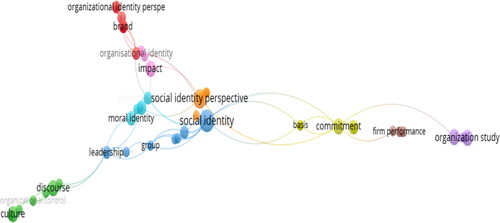

Then co-occurrence and cluster analysis are carried out with bibliometric network visualization using VOSviewer 1.6.12 software, the results of which are shown in . This analysis makes it possible to understand the creation of a network or group of keywords in a set of documents (Marcal et al., Citation2021). Vosviewer 1.6.12 enables the creation of visual cluster maps of co-occurrence (Arias et al., Citation2021). A map based on bibliographic data is used with a keyword analysis unit, namely organizational identity, with a minimum number of occurrences of terms of 5.

Figure 1. Visualization of Organizational Identity Construct Network.

Source: Proceed data by VOSviewer 1.6.12.

Structure indicators contribute to the restoration, visualization, analysis, and representation of the relevance of stakeholders who are members of academic networks (Szklarczyk et al., Citation2017) on the theme of organizational identity in the field of knowledge management. To analyze the academic network structure, co-occurrence analysis is used. This analysis shows the resulting relationship between several keywords coexisting in different publications at the same time; the shorter the distance between the two terms, the greater the number of occurrences with the two terms (Redeker et al., Citation2019). shows the connection and grouping of concurrent occurrences of organizational identity keywords among 118 publications analyzed in the Scopus database. Among the 118 articles, 431 keywords were obtained, 48 of which met the requirements for appearing at least 5 times in an article.

Most variables that relate to organizational identity are variables of managerial implication. Keywords with the highest intensity are associated with the increased occurrence. The intensities for the most representative terms are as follows: organizational identity, case study, commitment, impact, and social identity perspective. In addition, 4 clusters help determine trends in research with the theme of organizational identity, namely Cluster 1 - organizational identity success criteria (66.9%); Cluster 2- the process of organizational identity involvement in the organization (15.2%); Cluster 3- operational support for organizational identity (10.1%); cluster 4- organizational resources (7.6%).

The development of organizational identity research in explained that research on organizational identity was dominated by conceptual methods, grounded theory, and interviews using a case study strategy. This is because research with the theme of organizational identity is still developing in various perspectives of scientific studies. Found 22 articles with quantitative methods through a survey strategy on testing the influence of organizational identity from the perspective of antecedents, consequences, moderation, and mediation. Furthermore, 7 articles were found that formulated propositions using qualitative methods through grounded theory and case studies. Furthermore, an analysis was carried out on 29 articles to explore the constructs related to organizational identity in the concepts of antecedents, mediation or moderation, and consequent with units of research analysis. The results of this analysis are presented in .

Furthermore, from the perspective of developing historical theory, research on the theme of organizational identity is dominated by two theories, namely identity theory and social identity theory (Hogg & Williams, Citation2000). Along with the development of research on organizational identity from various perspectives in the field of science, various theories have begun to be used as presented in .

Table 2. Theory in organizational identity.

The last thing that is no less important in the results of the analysis of the literature is the research setting. From the results of the grouping conducted, the research with the theme of organizational identity was dominated by settings in private organizations, namely 71.18% and the remaining 28.81% in public organizations. This shows that so far, the flow of research seems to conclude that organizational identity is only needed by private organizations, not public organizations. Therefore, it is interesting to examine more deeply the portrait of organizational identity in the public sector which is still lacking attention.

The organizational identity construct is recognized as a broad perspective for understanding organizational processes and outcomes and offers ‘great theoretical promise’ (Alvesson et al., Citation2008; Brown, Citation2019; Coupland & Brown, Citation2012). Sustainable organizational identity raises interactions and dialogic processes between organizational members that are formed in support of the organization’s life journey (Hewitt et al., Citation2020). A growing number of sustainability issues have been cited as having an impact on organizational identity (Glavas & Godwin, Citation2013; Onkila et al., Citation2018), however, this does not mean that sustainable organizational identity has been clearly defined or reviewed (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). This is an opening for further research to understand how sustainable organizational identity is formed.

Rockwell (Citation2019)) states that sustainable organizational identity is appropriate for representing internal resources in organizations with intangible and rare criteria. Furthermore, different from the theoretical perspective in This study portrays sustainable organizational identity through the perspective of resource-based view (RBV) theory. RBV theory is a theory on the analysis and interpretation of internal organizational resources that emphasize the ability to formulate strategies to achieve competitive advantage. This theory explains the development of competitive advantage through a heavy emphasis on organizational assets and capabilities in terms of internal organizational strengths (J. Barney, Citation1991; Wernerfelt, Citation1984).

Further is the discussion related to methodology. The results of the literature analysis of 118 articles in and state that research on organizational identity is dominated by conceptual methods, grounded theory, and interviews using a case study strategy. The development of studies with the theme of organizational identity shows that the object of this research is still being explored for the novelty of roles, processes, and impacts produced through various studies. Research on organizational identity with the antecedent, consequent, moderation, and mediation framework is only 19% of the 118 bibliometric results articles. In 19% of the articles, there were 22 articles used a survey strategy on quantitative methods, and the remaining 7 articles formulated propositions using grounded theory strategies and case studies on qualitative methods. From the results of this analysis and supported by a recent study by Frostenson et al. (Citation2022) who build on organizational identity concepts and indicators from a sustainable perspective, this research wants to raise the theme of organizational identity in a sustainable context through an antecedent, consequential, moderating framework through quantitative methods using a survey strategy.

Table 3. Methodology of previous researches.

This research, specifically, proposes anthropomorphism and agile leadership as determinant of sustainable organizational identity, and also proposes competitive advantage as consequence of sustainable organizational identity. Furthermore, this research proposes change management as moderating variable between sustainable organizational identity and competitive advantage. The definition of interest variables is provided as in .

Table 4. Definition of variables.

2.2. Sustainable organizational identity

In the last few decades, academics have been interested in researching the theme of organizational identity. From a traditional perspective, organizational identity has been linked to how members perceive the organization, as to what is central, enduring, and distinctive (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985; Whetten, Citation2006). Organizational identity has been understood as referring broadly to what members feel and think about their organization. This is assumed to be a shared collective understanding of the values and unique characteristics of the organization (Hatch & Schultz, Citation1997). Organizational identity is a collective manifestation that distinguishes it from personal views or self-understanding (Gioia et al., Citation2000). That the trajectory of collective identity formation, from “I think” to “we think” means that individual cognitions of identity tend to be at the root of shared cognitions which may over time become institutionalized in the sense that they transcend specific individuals (Ashforth et al., Citation2011). Organizational identity is not the same as the external image of the company but emerges through processes within the organization. Organizational identity refers to the core corporate characteristics and features that appear to be most relevant to internal stakeholders i.e., members of the organization (Phillips et al., Citation2020). After all, organizational identity is the result of a dynamic process in which individuals and groups within the organization are active (Carlsen, Citation2016).

The formation of the organizational identity concept by Albert and Whetten (Citation1985) is based on three phenomena proposed by Cheney (Citation1983a) and adopted by Miller et al. (Citation2000), namely feelings of solidarity, organizational support (loyalty), and perceptions of similarity of characters. Feelings of solidarity, namely a sense of belonging, feelings of strong emotional attachment, self-reference in organizational membership, and pride in organizational membership. Organizational support or loyalty is loyalty to the organization and enthusiasm for organizational goals; which means the support and protection of attitudes and behavior for the organization regarding its values and goals. Perception of character similarity, namely the perceived similarity in terms of shared characteristics and concerning shared values or goals; people in the organization feel that they have the same goals and interests as other members of the organization.

Organizational identity influences members in making decisions based on perceived relevant values (Cheney, Citation1983a). In line with this, organizational identity is considered a persuasive mechanism in which the identity of organizational members can be influenced to support organizational activities (Cheney & Tompkins, Citation1987). This makes the goals of the organization become part of the goals of the members of the organization. This means that members of an organization with a strong organizational identity will be motivated to work hard to achieve these goals (Cheney, Citation1983b).

Relatively recently, scholars have begun to question the notion of identity as enduring, skeptical of the tendency to equate identity with certain enduring qualities or features that are perceived as representative of the organization. Organizational identity, it is claimed, is not fixed but changes over time. Some experts propose a dynamic view of identity. Gioia et al. (Citation2000) point to the interrelationship between identity and image, implying that IO does not have to last long but can change over time. Organizational identity has a dynamic character and is best seen as an ongoing construction of the relationship between self, work, and organization (Alvesson et al., Citation2008; Alvesson & Empson, Citation2008). Identity work is a way of defining oneself and the organization (Coupland & Brown, Citation2012). Identity is non-static and created in complex contexts (Baumgartner, Citation2009; Verbos et al., Citation2007). It has even been suggested that Schultze and Trommer (Citation2012) that organizational identity has more to do with emerging processes than specific circumstances. This process can be understood actively when the organizational identity actively learns to “express”, “reflect”, and “claim” – not as a specific enduring quality or feature that is seen as unique.

Increasingly, sustainability issues are mentioned as having an impact on organizational identity (Glavas & Godwin, Citation2013; Onkila et al., Citation2018). However, this does not mean that the organization’s sustainability identity has been clearly defined or disputed. When issues of identity have been discussed concerning sustainability, they have been linked to lifestyle choices through consumption (Kiefhaber et al., Citation2020; Niinimäki, Citation2010; Soron, Citation2010) or the work of individual identity of certain professional groups, such as leadership sustainability (Carollo & Guerci, Citation2017; Wright et al., Citation2012). Chong (Citation2009); Glavas and Godwin (Citation2013); Frandsen (Citation2017); Simões and Sebastiani (Citation2017); Onkila et al., (Citation2018) concluded that sustainability is a construction aspect of organizational identity. Sustainability engagement is becoming an important aspect of defining how an organization should be. Further findings that organizational identity’s traits are predominantly socially constructed with a constructivist approach; where organizational identity is not something that is static or lasts a long time but is related to ongoing construction between individuals and groups within the organization (Carlsen, Citation2016).

Answering the question of how sustainable organizational identity is formed Ashforth et al. (Citation2011) and Carlsen (Citation2016) provide an understanding of the nature and rationale for constructs that result in strong sustainable organizational identity. Organizational identity involves motivation for sustainable work (Baumgartner, Citation2009; Pei, Citation2019). Consistent with understanding identity as socially constructed, especially within organizations, sustainable organizational identity naturally relates to what internal constituents perceive when building organizations as sustainable. Sustainability academics have demonstrated tools for creating more sustainable organizations (Chong, Citation2009; Frandsen, Citation2017; Onkila et al., Citation2018; Simões & Sebastiani, Citation2017). Such tools can include, for example, codes of conduct (Frostenson et al., Citation2022), target setting (Simões & Sebastiani, Citation2017), and reporting (Onkila et al., Citation2018). It shows that sustainability identity can be ‘created’ by management through this tool.

But not only based on the tools mentioned above, based on references from Alvesson and Empson (Citation2008) and Alvesson et al. (Citation2008) that a deeper understanding of sustainable organizational identity requires in-depth research on the relationship between performance, organizations, and individuals. In further research, it was concluded that sustainable organizational identity can be maintained and manifested in an indirect way through management tools because these tools cannot yet convey an understanding of the organization as a morally trustworthy organization (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). Despite the aforementioned research, which deals with sustainable organizational identity in how it occurs, the salient aspects and impacts are still not fully resolved (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). Gaining insight into building a sustainable organizational identity requires diving into the organization and capturing the perceptions of its internal constituents. It remains an open question as to what sustainable organizational identity builds and builds on, as understood by the individuals who enjoy sustainable organizational identity, such as the internal constituencies of the organization. In particular, it is advisable to get into the organization and understand how internal stakeholders identify themselves in certain ways (Phillips et al., Citation2020). One can speak of sustainable organizational identity as a separate concept, indicating how members of an organization feel and think about their organizational commitment and accomplishments concerning sustainability (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). It is therefore important to identify the specific basis of sustainable organizational identity, more specifically the underlying beliefs about what makes organizational identity sustainable and how processes of sustainable organizational identity are constructed (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). From these descriptions, it is interesting to construct a model through an antecedent, consequent and moderating framework of sustainable organizational identity in organizations.

2.3. Anthropomorphism

Starting from the findings of Mithen and Boyer (Citation1996) that the idea of anthropomorphism emerged around 40,000 years ago. Anthropomorphism helps humans deal with individual actions or other objects through knowledge about themselves (Ashforth et al., Citation2020). Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics, such as physical attributes, motivations, intentions, or emotions, to non-human entities (Chandler & Schwarz, Citation2010; Han et al., Citation2019; Waytz et al., Citation2010; Zhou et al., Citation2019), represents individual cognition that uses symbols such as language, metaphor, or scientific notation to understand, create meaning, and adapt to environmental conditions (Allen et al., Citation2021; Baron, Citation2007; Holtbrügge et al., Citation2015). Anthropomorphism is defined from an understanding as the attribution of human characteristics, such as physical attributes, motivation, intentions, or emotions to non-human entities (Haslam & Ellemers, Citation2005).

Holtbrügge et al. (Citation2015) and Waytz et al. (Citation2010) stated that anthropomorphism influences individual perceptions and behavior. When combined with objects, the object’s anthropomorphic morphology is expected to increase the sense of connectedness with the object through individual motivational effects (White, Citation1959). Anthropomorphism survives today and is universal, involuntary, and largely unconscious due to the possibility of humans interpreting ambiguity vis-à-vis what is most important to themselves and other living things (Guthrie, Citation1993). Interactions with non-human entities are accompanied by uncertainty because people are generally more used to interacting and behaving according to human knowledge and its norms (Kang & Kim, Citation2017). By anthropomorphizing the organization through IO, individuals can rely on accessible human characteristics to understand intentions, behavior, personality, and a strong sense of control and attachment to non-human entities, leading to achieving a competitive advantage.

Ashforth et al. (Citation2020) suggest that anthropomorphism allows organizational members to understand their organization in terms of “who is or who we are as an organization” (eg personality, attitudes, and influences) rather than "what is or what we are (eg industry, structure, age). Individuals can describe their organization in terms of “what” (category-based understanding) and in terms of “who” (individual-based understanding). Three different organizational conceptualizations can also be adopted, each cutting an organizational perspective on the “what” and “who” as a unitary entity or “social actor”, as a composite entity, and as a collection of members (Ashforth et al., Citation2020).

Although non-human references within or associated with an organization can be anthropomorphized, such as departments, ideas, products, or traditions, the focus of this research is the organization itself. Anthropomorphism is a mechanism for assuming the identity of “who is or who we are (as an organization) in an organization (Ashforth et al., Citation2020); saying “who” serves as the basis for placing organizations in relevant social categories, providing contexts for individuals to interpret and ascribe humanity to organizations. It is supported by a statement by Cornelissen and Elving (Citation2003) that organizational anthropomorphism is a metaphorical device that involves giving the identity "who is it or who are we?" to an organization. Organizations are very likely to become targets of anthropomorphism because organizations are created and maintained by people reflexively and sometimes even interpreted as individuals (Ashforth et al., Citation2020). Remembering the human mind that shapes organizational decision-making and actions is the cognitive move of organizational representation (King et al., Citation2010; Whetten & Mackey, Citation2002). This suggests that organizations may tend to look more like humans than other collectives that lack perceived intention and agency.

It is assumed that organizational identity is a collective shared understanding of the values and characteristics of an organization (Hatch & Schultz, Citation1997). Organizational identity is a collective manifestation that distinguishes it from personal views or self-understanding (Gioia et al., Citation2000). Organizational anthropomorphism can be used to foster loyalty among employees (Bhattacharya et al., Citation1995). The implications of anthropomorphism for organizational members are very important (Zavyalova et al., Citation2017). This is due to several reasons, including; first, organizations create and maintain anthropomorphic depictions of organizations through interactions with one another through speech and text (Taylor, Citation2014); both organizational experts suggest that anthropomorphism allows members to have a relationship with the organization (Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, Citation2007), a psychological contract with the organization (Conway & Briner, Citation2009), and feel supported by their organization (Eisenberger et al., Citation1986). Anthropomorphic organizational identity defines an organization as an entity (whether unitary or composite) in terms of “who” rather than “what” providing a foundation for further anthropomorphic elaboration or modification over time (Sillince & Barker, Citation2012).

2.4. Agile leadership

Starting from Burns’ (Citation1978) understanding that leadership is the activity of leaders as a relationship between leaders and followers, this relationship is related to the motivation and goals of both. Leadership in a more specific concept is the process of influencing others to understand and agree about what is necessary and how to do it and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to achieve common goals; where the definition includes not only efforts to influence and facilitate the work of groups or organizations today, but also to ensure readiness to face future challenges (Yukl, Citation2012). Leadership is a series of processes capable of moving an organization, or adapting to significantly changing circumstances, being able to define what the future should look like, aligning others with the vision, and inspiring others to face challenges and achieve goals (Kotter & Heskett, Citation2011). Leadership is an influence process that is carried out when institutional, political, psychological, and other resources are used to arouse, involve and satisfy the motives of followers (Cummings & Worley, Citation2009). Furthermore, leadership is to create conditions for individuals and organizations to thrive and achieve significant goals (Pendleton et al., Citation2021).

The development of the organization after the industrial revolution demanded that the organization be filled with agility to be agile in all positions. Agile leadership is defined as the ability to lead effectively under rapid changes and complex conditions (Joiner & Josephs, Citation2007). The concept of effectiveness in this definition means that leaders can anticipate and respond to change (Horney et al., Citation2010).

In the philosophy of agile leadership, Joiner and Josephs (Citation2007) describe leaders anticipating and adapting to change. It is important to act quickly and flexibly in a results-oriented manner and to be prone to group and teamwork because agile leadership tends to create a culture that encourages collaboration. This leadership conceptualizes at the group level therefore, agile leadership is based on a philosophy that describes how leaders influence processes between teams and stakeholders; it also shows that agile leaders indirectly influence groups and teams (Joiner et al., Citation2009). It can also be said that agile leadership is a type of leadership with a complex and multifaceted structure because leaders need to teach and need to learn, sometimes as followers, sometimes as listeners, and sometimes as guides of events and processes (Joiner & Josephs, Citation2007). Various experts argue that individuals who represent the organization, such as direct managers or CEOs, are most likely to be seen as templates for perceptions of "the organization" (e.g. (Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, Citation2007; Eisenberger et al., Citation1986). Agile leaders make their organizations remain nimble to survive and maintain their existence to achieve competitive advantage without being defeated by these factors (Akkaya, Citation2020). It can be assumed that there is no doubt that the agile leadership type as the color of the organization will bring the organization to be agile; being able to keep up with change because of this dynamis (Porter, Citation1985) m is at the heart of agility that will help leaders focus on their goals.

2.5. Competitive advantage

In line with the study of Macmillan and Jones (Citation1984) that almost all organizations are involved in some form of competition, it can be seen from the perspective of scarce resources. The initial idea of creating competitive advantage begins with developing organizational development procedures that will be carried out by the organization, then the organization will analyze what the goals of the organization are and what policies the organization takes to achieve its goals. Organizational competitive advantage is a condition in which competitors are unable to duplicate the competitive strategy implemented by the company, nor can competitors obtain the benefits obtained by the company through their competitive strategy (J. Barney, Citation1991). On the other hand, Lamb et al.(Citation1994) define competitive advantage as a set of features of an organization that can be accepted by the market as an important element of excellence in competition. This is in line with Porter’s opinion, which emphasizes the importance of the element of excellence, namely the privileges possessed in competition.

The notion of “competitive advantage” is claimed to be applicable in the public sector (J. B. Barney & Arikan, Citation2005; Powell, Citation2001). This claim is based on the assumption that college and corporate life activities face the same type of competition and have the same need to survive and prosper by realizing a better fit with their environment (Bryson et al., Citation2007; Johnson et al., Citation2008). The concept of “competitive advantage” has been accepted in the higher education institution context (Eckel, Citation2007; Marginson, Citation2007; Mazzarol & Soutar, Citation2008). However, as shown that the study of competitive advantage is still dominated by private organizations, the study’s attention is limited in understanding its applications and implications in the context of higher education (Knight, Citation2004). Relevant research to date is largely conceptual, and very limited empirical evidence found in investigating the factors for achieving sustainable competitive advantage (Sriwidadi et al., Citation2016).

The competitive advantage variable in this case is related to the context of higher education institutions using de Haan’s definition of understanding (2015) referring to Porter (Citation1985), that competitive advantage is the search for a profitable and sustainable competitive position against the forces that determine industrial competition associated with "value"; that value creation increases the chances of an organization’s survival. That competitive advantage in higher education is reflected in the academic position marked by ranking (de Haan, Citation2015). In line with the developing concept, the profit-seeking area of PT is driven by conditions related to government budget cuts, marketization of the public sector, increased student mobility, as well as economic and knowledge growth; as a result of these external factors, the term competitive advantage began to gain popularity in the public education sector (de Haan, Citation2015). The popularization of this concept in the education sector may also be due to internal factors; where universities always have competitive "genes" to achieve high academic standards with internationalization, reputation, marketing, and promotion tools to gain competitive advantage (Chan & Dimmock, Citation2008).

Riesenberger (Citation1998) says that sustainable competitive advantage is no longer embedded in physical assets and financial capital but in the effective focus of unique intellectual resources. Valuable, rare, perfectly inimitable, and imperfectly substituted organizational assets are key resources in sustainable competition (Ma, Citation2000; Newbert, Citation2008; Tuan & Takahashi, Citation2010). The likelihood of resources generating competitive advantage is much greater when they have valuable, rare, and distinctive key premises that can be leveraged for maximum impact (Rockwell, Citation2019). Competitive advantage is a building block of competitiveness in which organizations apply skills and resources to obtain superior returns on investment in market competition (de Haan, Citation2015).

RBV theory emphasizes the concept of organizational attributes that are difficult to duplicate as a source of greater performance and competitive advantage (Kamukama et al., Citation2011). Based on the explanation above, organizational identity has met the criteria as a unique resource capable of creating value for the organization so that a sustainable competitive advantage will be achieved.

2.6. Organizational change

Today more and more organizations are facing a dynamic and changing environment that demands that organizations make changes as a reaction to internal and external changes. Hage (Citation1999) describes the organizational change in the language of organizational innovation; the notion of organizational innovation is the adoption of new ideas or behaviors into organizations which include: new products, new services, new technologies, or new administrative applications. The process of organizational change also describes the increase in new capabilities, behaviors, and beliefs within the organization (Hart & Fletcher, Citation1999). Organizational change is a series of development and movement of organizational functions, either gradually or drastically, so that the organization can adapt to environmental pressures or demands (Pierce et al., Citation2002). Furthermore, organizational change is a medium of planned and organic transformation in the organizational structure, technology, or people in it (Baron & Greenberg, Citation1990). Organizational change is a process by which an organization moves from its current conditions and wants future conditions to increase its effectiveness (Jones, Citation2012). Broadly speaking, organizational change is defined as a system of application and transfer of knowledge and behavior to plan the development, improvement, and strengthening of strategies, structures, and processes that lead to organizational effectiveness (Cummings & Worley, Citation2009).

In essence, most definitions of organizational change refer to adaptation to the way an organization operates including structure, strategy, systems, procedures, or ownership. Organizational change is considered a constant feature of organizational life, impacting operational and strategic activities (Armenakis & Harris, Citation2002; Burnes, Citation2004; Waddell & Pio, Citation2015). Organizational change is often defined dichotomously, namely organic, sustainable, unplanned (Hartley, Citation2002; Weick & Quinn, Citation1999), and incremental (Kanter et al., Citation1992). Organizational change is defined as a planned change that includes structure, strategy, human resources, and technology as a form of organizational response to seek to improve the organization’s ability to adapt to environmental changes and seek changes in organizational behavior in achieving competitive advantage (Rafferty & Griffin, Citation2006).

In line with planned organizational change, it has a very broad impact, including on the process of achieving competitive advantage. Puusa and Kekäle (Citation2015) state that organizational change can go fast or slow, depending on the psychological reality that occurs in an organization. Changes are aimed at improving organizational performance for the better to achieve organizational goals and objectives. In line with the previous reference that the purpose of the change is only two. First, change seeks to improve the organization’s ability to adapt to changes in the environment; Second, change seeks changes in the behavior of organizational members. Consistent organizational changes from managerial actions and organizational design will affect organizational credibility (Ashforth et al., Citation2020).

2.7. Research theory

The key principle of RBV (Resource-Based View) is that organizations need to look within to identify sources of competitive advantage. RBV analyzes and interprets organizational resources to understand how organizations achieve sustainable competitive advantage. RBV focuses on the concept of difficult-to-imitate firm attributes as a source of superior performance and competitive advantage (J. Barney, Citation1991; J. B. Barney & Arikan, Citation2005; Hamel & Prahalad, Citation1996). Resources that cannot be easily transferred or purchased, require a wide learning curve or major changes in organizational climate and culture, are more likely to be unique to the organization and more difficult for competitors to imitate (J. Barney, Citation1991; J. B. Barney & Arikan, Citation2005) The RBV helps organizations to understand why competencies can be considered the most important organizational assets and, at the same time, to appreciate how these assets can be used to improve organizational performance (Hamel & Prahalad, Citation1996) RBV organizations accept that attributes related to experience, organizational culture, and competence are critical to firm success (Campbell & Luchs, Citation1997; Hamel & Prahalad, Citation1996).

Superior resources are in the form of organizational assets that are considered special/odd (idiosyncratic), such as brands, and patents which are identified as determining factors to gain competitive advantage (Fahy, Citation2000). With RBV organizations accept that attributes related to past experiences, organizational culture, and competencies are critical to firm success (Campbell & Luchs, Citation1997; Hamel & Prahalad, Citation1996). Furthermore, the likelihood of an organization’s resources generating competitive advantage is much greater when the organization has valuable, rare, and distinctive key premises that can be leveraged for maximum impact; while organizations must meet the criteria of being intangible and scarce, there is no resource better suited to the role than sustainable organizational identity; organizational identity is a valuable, rare, inimitable component; that organizations must utilize to strengthen, support, protect, and sustain their contribution to competitive advantage (Rockwell, Citation2019). In line with this, an applicable mission and vision such as organizational identity can be a strategy for dealing with and resolving crises that occur in organizations (Altıok, Citation2011).

Furthermore, the use of RBV theory in this study is complemented by the use of several theories at the organizational level, including organizational identity theory, psychological ownership theory, complexity theory, and organizational development and change theory. Organizational identity theory is defined as who we are and consists of identity claims that reflect central, distinctive, and enduring organizational characteristics (Whetten, Citation2006). Every identity claim must meet all three of these criteria, meaning that identity must be central, distinctive, and ongoing to the organization.

Organizational identity theory describes organizations as more than just social collectives, in that modern society treats organizations in many ways as if they were individuals; organizational identity gives the organization the power to act and assigns organizational members responsibility for achieving organizational goals (Bauman, Citation1990; Coleman, Citation1974; W. R. Scott, Citation2002; Zuckerman, Citation1999). This theory will strengthen the hypothesis of the relationship between anthropomorphism and sustainable organizational identity. This view of the theory points to the difference between organizational identity and collective identity, highlighting the important functional and structural parallels between the identities of organizational actors and individual actors; further equating identity with a sense of subjective distinctiveness of organizational actors which is referred to as self-view or self-definition and is reflected in the notion of organizational self-actualization (Czarniawska & Wolff, Citation1998).

Furthermore, from the perspective of psychological ownership theory Pierce et al. (Citation2003) in looking at the relationship between anthropomorphism and sustainable organizational identity explain that psychological experience is obtained when employees develop ownership of a target, in this case the organization can be directed as a whole or at certain aspects. from the organization. Organizational identity touches organizational members to have sensitivity in understanding organizational values and acting on behalf of the organization (Gioia et al., Citation2013) so that it can underline the proposition.

The theory or concept of complexity is developed from systems theory, especially in the natural sciences and biology which studies non-linear interactions in a system, such as the solar system and so on. This theory was later adopted into the social sciences to study organization and management theory. Complexity theory supports RBV theory as a must-have provision to deepen the concept of systems thinking and can be used to study organizational management and design (Klijn, Citation2008; Okwir et al., Citation2018). In designing an organization, the complexity of the organization must be adjusted to the complexity of the environment and technology (Anderson, Citation1999). Complexity theory studies complex systems, non-linear or non-sequential situations, and the emergence of non-linear problems in chaotic conditions (Devereux et al., Citation2020). When an organization faces complex problems, the organization will shape or modify the surrounding environment effectively and continuously improve. In this condition, organizational ability is needed to regulate itself when complex problems occur.

Next is the understanding of development theory and organizational change which explains continuous change from Kurt Lewin’s action research change model (Cummings & Worley, Citation2009). The stages of organizational change include identifying general ideas or initial ideas, finding facts, planning, taking second action steps and so on which are the basic theories of action research (Helms-Mills et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, this theory continues to be used by practitioners and scientists in solving organizational problems and even social problems (Helms-Mills et al., Citation2008).

This theory illustrates that the phases of organizational development will continue. The organizational change also plays a role in improving the state of organizations that have experienced stagnation and even decreased productivity (Weick & Quinn, Citation1999). The organizational change cycle is a model of change that does not stop but is sustainable and continues to grow; so that it is not visible when the overall organizational change will end. Organizational identity that has been developed finds several points of interaction and raises the process of achieving organizational goals including organizational change. Position of the research theory can be seen in .

2.8. Proposition development

2.8.1. Anthropomorphism and sustainable organizational identity

The discussion that develops and becomes an important aspect in the construction of organizational identity is sustainability (Frandsen, Citation2017; Onkila et al., Citation2018). Sustainable organizational identity shows how organizational members feel, and think about their organizational commitment and accomplishments concerning sustainability (Ashforth et al., Citation2011; Carlsen, Citation2016). Sustainable organizational identity is a separate concept, which shows how organizational members feel, and think about organizational commitment and achievements concerning sustainability (Frostenson et al., Citation2022). Organizational anthropomorphism is a metaphorical device that involves assigning the identity "who is it or who are we?" to the organization (Cornelissen & Elving, Citation2003).

In line with this description, Guthrie (Citation1993) states that through object anthropomorphizing, organizational members can experience a sense of comfort in forming intimate and friendly relationships with these objects. Anthropomorphizing spurs the formation of basic social motivation as the basis for individual behavior (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Anthropomorphizing can increase individual determination to maintain a business by increasing a positive evaluation of the business (Horak & Taube, Citation2016; J. Li et al., Citation2020). Based on Semereci and Vorley’s survey results (Semerci & Volery Citation2018); Cardon et al., (Citation2005) stated that entrepreneurs describe their business as a baby to increase emotional attachment, stronger personal relationships, and deeper identification with the business as with parent and child relationships. When a business is anthropomorphized, individuals tend to respect it more, identify strongly with it, and respond positively when objects are anthropomorphized (Xu & Zeng, Citation2021). Business anthropomorphizing also affects resilience in entrepreneurship (Paramita et al., Citation2022). Another important point is that, from a previous literature review, it was found that anthropomorphized objects are more likely to be positively evaluated so that their existence is less likely to be ignored (Jeong & Kim, Citation2021; Xie et al., Citation2020). All of the previous literature above corroborates the opinion of King et al. (Citation2010), that it is important to anthropomorphize organizational identity as an organizational effort to guide members to act and speak on behalf of the organization.

Referring to the theory of organizational identity contributes to that organizational identity as a set of characteristics about what members feel about their organizations (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985). Organizational identity theory (Whetten, Citation2006) is used to support the RBV theory in explaining anthropomorphic factors that maximize the function of organizational identity symbols that are central, distinctive, and sustainable in creating competitive advantage. This is supported by the opinion of Epley et al. (Citation2008); Dutton et al. (Citation2014) that with a unique organizational character, it will be a target of anthropomorphism which will have a huge impact. Organizational anthropomorphism invites organizational members to think, feel, and behave about their organization (Ashforth et al., Citation2020).

In addition to organizational identity theory, Pierce et al.’ psychological ownership theory (2003) explains that psychological experiences in which organizational members develop ownership of a target can be directed at the organization as whole or specific aspects of the organization such as groups, tasks, work equipment, or the work itself. organizational identity touches organizational members to have sensitivity in understanding organizational values and acting on behalf of the organization (Gioia et al., Citation2013).

From the description above, this study proposes a new proposition where sustainable organizational identity will be optimal in its organizational role when anthropomorphism acts as an antecedent. This study assumes that it is likely that organizational identity’s anthropomorphism gives attachment to the understanding of the organizational picture of organizational members from "what" to "who"; so that the humanization of organizational identity will color the organization and therefore the role of members in the organization will be optimal in achieving organizational goals. Formally, the proposition is formulated as follows:

P1: Anthropomorphism has a positive effect on sustainable organizational identity

2.8.2. Agile leadership and sustainable organizational identity

The application of leadership in the rapidly changing conditions of the environment and the complexity of the situation is becoming an increasingly important issue and is a strategic aspect in the application of leadership styles. Starting with Hatch and Schultz (Citation1997) stated that leadership in the organization is considered a symbol of organizational identity because it can be used to influence organizational members in feeling and thinking about the organization. Related to sustainable organizational identity, it is argued that organizational identity is shaped by the interpretations and beliefs of organizational leaders to guide and encourage organizational behavior (Foreman & Whetten, Citation2002). That the main goal of leadership is to build a unified organizational identity that members can understand and follow (S. G. Scott & Lane, Citation2000).

Organizational leadership must be agile in examining organizational identity and ascertaining how organizational identity works in maintaining the engagement of organizational members with the organization in difficult times, uncertainties, and changing work practices (Aitken & von Treuer, Citation2021). Leadership in organizations creates views that influence the values, commitments, and aspirations of members that they want to achieve in organizational issues that are interpreted by members of the organization (Ererdi & Durgun, Citation2020). And as an important note from the results of in-depth interviews is that organizational leaders need to be swift in changing the concept of organizational identity when needed to align identity with new organizational strategies or realities to achieve competitive advantage (Ravasi & Phillips, Citation2011). The nuances of agile leadership in the organization are indeed very important. However, on the other hand, how and when organizational leadership agilely shares knowledge effectively to maximize response is still lacking in research (Chatwani, Citation2019).

In line with this description, Anderson (Citation1999) illustrates that complexity in organizations is related to the goals and ways of interacting within them; when an organization faces complex problems, the organization will shape or modify the surrounding environment effectively and continuously improve. In this condition, the organizational ability is needed to regulate itself when complex problems occur. The development of the organization in the future is increasingly difficult to predict with certainty. The ongoing trend is that the rate of change will continue to increase with high complexity and interdependence will continue to grow so that organizations are in a dynamic system (Devereux et al., Citation2020). This explanation is supported by complexity theory, that organizations are non-static, dynamic, and complex systems, so organizational skills as leaders are needed to manage problems within the organization (Klijn, Citation2008; Okwir et al., Citation2018). The theory supports the RBV theoretical framework, in which this theory can also be oriented towards managerial activities (Collis & Montgomery, Citation1995) and organizational dynamic capabilities as a source of competitive advantage (D. J. Teece et al., Citation1997).

Studies on the influence of leadership on organizational identity have so far produced mixed conclusions. Based on previous studies, seven studies examine the influence of various types of leadership on organizational identity with different conclusions. Five studies state that leadership influence organizational identity (Akbari et al., Citation2014; Chen, Citation2011; Hesar et al., Citation2019; Ko & Choi, Citation2021; Omanwar & Agrawal, Citation2022). Two other studies conducted by Van den Broeck et al. (Citation2016); Cheng and Wang (Citation2015); Jansson (Citation2013) revealed the fact that leadership does not influence organizational identity. Van den Broeck et al. (Citation2016) suspect that other factors cause differences in research results regarding engaging leadership in organizational identity; where the aggregation of organizational needs conflicts with the conceptualization of needs within the organization and exists as a separate entity.