Abstract

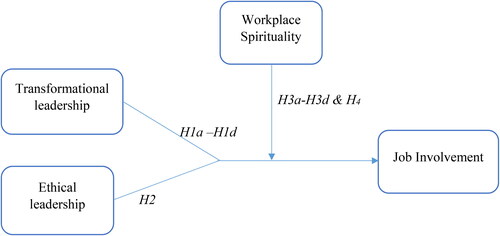

As an emerging construct, workplace spirituality has gained credence in organisational management literature due to its effect on work-related behaviours. This paper examines the moderating effect of workplace spirituality on the relationship between transformational, ethical leadership and employee job involvement (EJI) in a developing country. We adopt quantitative approach and cross-sectional survey design to collect data from 416 employees in 10 selected public and private universities in Ghana. We analysed the data using descriptive statistics, correlation and hierarchical regression model. The results indicate that the transformational leadership dimensions and ethical leadership have strong significant positive relationship with EJI. We further establish that workplace spirituality moderates the relationship between ethical leadership and EJI. Regarding transformational leadership, workplace spirituality moderates only the relationship between idealized influence and EJI. The paper provides new findings to bridge the gap in the leadership literature by presenting original evidence that workplace spirituality is an effective moderator in the association between ethical leadership, idealized aspect of transformational leadership and EJI. Additionally, the outcome of this research sparks new discourse, and contributes to organizational practices and policies in Ghana and beyond.

1. Introduction

The unstable economic conditions in which organisations operate, characterised by intense competition, downsizing, globalisation, restructuring, etc. (Van der Walt & Swanepoel, Citation2015) have brought with it numerous employee work-related challenges such as employee dissatisfaction, disengagement and less involvement (Adnan et al., Citation2020). To address this situation, organisations are keen on promoting organisational climate that encourages overall motivation, commitment and employee well-being through effective leadership styles (Pawar, Citation2009; Puni et al., Citation2021). Similarly, organisational researchers are expanding the fringes of their research to encompass the effect of leadership style on various work outcomes, as well as examining cogent predictors such as workplace spirituality on the relationship between leadership style and EJI.

Leadership style is the collection of traits, skills and behaviour displayed by the leader, which differentiate one leader from others through the exercise of this relatively small range of skills or competent areas (Ohemeng et al., Citation2018). EJI refers to the ‘degree to which one psychologically identifies with one’s job, that is, a cognitive or belief state of psychological identification with a particular job’ (Kanungo, Citation1979, p. 342). EJI utilises the knowledge and skills of the employees to create efficient and dynamic organisations, make employees more valued and committed to the organisation, minimise conflict at all levels of the organisation thereby resulting in higher job satisfaction and lower staff turnover (Bayraktar et al., Citation2017). Workplace spirituality is the fusion of spiritual principles and values such as community, connectedness, belonging, purpose, altruism, and virtue into the work (Kolodinsky et al., Citation2008), thereby creating a spirituality climate.

Despite the substantial volume of research on leadership style and employee outcomes, such as employee involvement (Nazem & Mozaiini, Citation2014), job satisfaction (Hilton et al., Citation2023), employee commitment (Puni et al., Citation2021), employee engagement and turnover intention (Suifan et al., Citation2020), and in-role performance (Kia et al., Citation2019), there still remain much uncertainty about the relationship between leadership style and EJI (Breevaart et al., Citation2014). Previous literature have described the relationship between these two variables as positive, negative or neutral (Thamrin, Citation2012; Wan Omar & Hussin, Citation2013; Al-Sada et al., Citation2017). Aside the prevailing inconsistencies, majority of the studies are concentrated in the advanced economies with relatively few from the developing context. This study therefore intends to investigate the relationship between leadership styles (transformational and ethical) and EJI from a developing country perspective.

Additionally, due to the volatile nature of organisations environment which has affected employees’ commitment and well-being (Pawar, Citation2009), workplace spirituality is now receiving increasing attention as one of the plausible variables that could influence the relationship between leadership style and employee outcomes like job involvement. The argument is that workplace spirituality is said to inspire employees to focus on the vision of the organisation and be loyal to the organisation since employees experience psychologically a state of belonging and connectedness at the workplace (Rego & Cunha, Citation2008). However, empirical evidence on the mechanism by which workplace spirituality influences the relationship between leadership styles and EJI is still evolving and limited in developing country context. For this reason, it is important to expand the body of knowledge regarding workplace spirituality to gain a more understanding of this phenomenon, and how it can enhance or obstruct the relationship between transformational, ethical leadership and EJI.

Within the developing context of Africa, workplace spirituality is a relatively new concept which has not yet been adequately investigated. Apart from some few works such as Van der Walt and De Klerk (Citation2014) which investigated workplace spirituality and job involvement using cross-sectional study of 412 employees chosen from two organisations in Welkom, South Africa, Acheampong and Agyapong (Citation2015) which examined workplace spirituality, job involvement and deviant behaviour, and Ajala (Citation2013) which studied the impact of workplace spirituality on employees’ well-being in the industrial sector of Nigeria, we have observed that there is a paucity of research concerning workplace spirituality within the developing setting, particularly Ghana. Therefore, we assess the moderating effect of workplace spirituality on the relationship between transformational, ethical leadership and EJI using cross-sectional data from public and private universities’ employees in Ghana.

This study is germane since it is overlooked not just in Africa but other developing context. This study also adds to existing knowledge by exposing the positive contributions of transformational and ethical leadership toward making employees become psychologically identified with their jobs, as organisations are exploring ways of leveraging on their human resource capabilities for competitive advantage, growth, and sustainability (Wood, Citation2020). Furthermore, this study contributes to leadership literature by suggesting that workplace spirituality climate serves as a psychological moderating mechanism that strengthens the relationship between transformational, ethical leadership and EJI from a developing country perspective. The succeeding sections entail the literature and hypotheses development, methodology, results and discussion, implication and conclusion.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Transformational leadership and employee job involvement

Transformational leadership portray leaders who use their charismatic personality and behaviours to influence subordinates to focus on higher ideals such as the vision of the organisation (Stock & Schnarr, Citation2016). Transformational leadership stimulates followers’ values, beliefs and consciousness to achieve extraordinary heights for superior collective interest (Hilton et al., Citation2023). Since transformational leadership stands for mutual support for common purpose, Burns (Citation1978) predicts that ‘transformational leadership ultimately becomes moral in that it raises the level of human conduct and ethical aspiration of both leader and led, and thus has a transforming effect on both’.

Transformational leadership comprise of four behavioural components: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualised consideration. Idealized influence – is a dimension of transformational leadership where the leader shares emotional connection with followers’ to the extent that followers’ emulates the noble ideals of the leader. Idealized transformational leadership style produces respect, appreciation, and trust among followers (Rasheed et al., Citation2020). Inspirational motivation – involves the formulation of inspiring vision, and the communication of the goals in various ways to capture the emotions of followers’ without necessarily identifying with them physically (Molodchik et al., Citation2020). Intellectual stimulation – is where the transformational leadership offer to followers’ intelligent concepts with the view of stimulating in followers’ new ways of tackling organisational problem (Cortes & Herrmann, Citation2019). The intellectual stimulation behaviour is accomplished by seeking ideas, opinions and inputs from followers’ thereby promoting creativity, innovation, and experimentation in followers’ which bring out novelty problem solving skill to tackle organisational challenges. Individual consideration – is concern with the personal development of the followers. Whereas the leader’s charisma may attract followers to the mission and vision of the organization, the leader uses the individual consideration to transform each follower individually. This transformational leader is able to accomplish goals by actively heeding to and accommodating followers’ personal needs for growth, learning and recognition (Puni et al., Citation2021).

An aspect of employee outcomes that has attracted the attention of researchers is job involvement. EJI is a situation where employees throughout an organization have authority to act and make decisions, have the information and knowledge needed to use their power effectively, and are rewarded in doing so (Wood, Citation2020). EJI is originally coined by Lodahl and Kejner (Citation1965) as a protestant work ethic emanating from unwavering employee who sees the job as part of their self-concept as oppose to an employee who is not job-involved, who is ‘living off the job’ and whose identity is determined by neither the type nor the quality of his/her work. EJI is considered a multifaceted construct which is associated with organisational outcomes such as absenteeism, employee turn-over and financial performance (Hettie & Robert, Citation2005; Wood, Citation2020). EJI research has become increasingly important because organisational policies and practices in themselves do not translate into organisational outcomes unless such policies have been converted in some way by employees into activities and actions. Hence, organisational researchers and practitioners believe that leveraging on the competencies and skills of employees by making them involved in various organisational tasks creates competitive advantage (Wood, Citation2020).

Theorists have long emphasised that transformational leadership affect EJI. Particularly, Bass (Citation1985) asserts that transformational leadership has the ability to inspire followers’ to focus on higher intrinsic needs thereby translating into greater identification and employee involvement at both the work unit and the organisational strategic levels. Shamir et al. (Citation1993) also submit that the transforming effect of the transformational leader inspire employees to surpass their own interest for the groups’ interest thereby creating an involvement climate. The involvement climate energises employees to assume greater identification with the work, which ultimately affect group objectives. Shamir et al. (Citation2000) again contends that transformational leadership creates an inspiring homogenous employee involvement climate across organisation to the extent that the transforming effect is felt at the unit as well as the organisation level. Under a transformational leader, the whole work environment assume an involving climate where the leaders, followers’, and the organisation as a whole work together to achieve goal congruence.

Empirically, studies (such as Cheng et al., Citation2012; Dwirosanti, Citation2017; Nazem & Mozaiini, Citation2014) indicate that transformational leadership behaviour is associated with EJI. For instance, Cheng et al. (Citation2012) investigated the moderating effect of emotional contagion, on the relationship between transformational leadership and subordinates’ job involvement among 210 soldiers from eight companies of the Taiwanese Army. They established that leaders with high emotional contagion had positive moderation effect on relationship between transformational leadership and subordinates’ job involvement than leaders with low emotional contagion. Again, using structural equation modelling in a sample of 167 work units, Richardson and Vandenberg (Citation2005) indicated that transformational leadership positively influence subordinate involvement perceptions. Dwirosanti (Citation2017) also reveals that transformational leadership has a direct significant positive effect on job involvement, meaning that the practice of transformational leadership dimensions is more likely to result in EJI. Assessing the relationship between transformational leadership and EJI at a higher education institution, Nazem and Mozaiini (Citation2014) employed multivariate linear regression to show that transformational leadership dimensions have significant relationship with EJI. Based on the foregoing findings, we hypothesize that:

H1a: Transformational leadership (idealized influence) is significantly related to EJI

H1b: Transformational leadership (inspirational motivation) is significantly related to EJI

H1c: Transformational leadership (intellectual stimulation) is significantly related to EJI

H1d: Transformational leadership (individualised consideration) is significantly related to EJI

2.2. Ethical leadership and employee job involvement

Ethical leadership is referred to as leadership embedded in the display of normatively proper behaviour exhibited through individual actions and interactive relationship as well as the encouragement of such behaviour among followers through two-way communication, support, and decision-making (Brown et al., Citation2005). It follows that ethical leadership style stresses on ethics (morality) (Toor & Ofori, Citation2009). Mainly, ethical leadership characteristics are founded on Aristotle’s philosophy of leadership, which argues that ‘leadership is more than a skill, more than the knowledge of theories, and more than analytical faculties. It is the ability to act purposively and ethically as the situation requires on the basis of the knowledge of universals, experience, perception, and intuition. It is about understanding the world in a richer and broader sense, neither with cold objectivity nor solipsistic subjectivity’’ (p. 464). Likely reasons for the interest of morality in leadership are due to recent corporate scandals which are basically connected to unethical and sometimes toxic leadership (Hilton & Arkorful, Citation2021; Treviño & Brown, Citation2004).

Research demonstrates that ethical leadership predicts several work outcomes such as job satisfaction, commitment and especially EJI (Brown et al., Citation2005). Brown et al. (Citation2005) reveal that ethical leadership associates with consideration behaviour, honesty, trust in the leader, interactional fairness, and socialized charismatic leadership. Consistently, these attributes predict employee outcomes such as EJI and satisfaction. Piccolo et al. (Citation2010) also found that ethical leadership impacts employee job involvement characteristics such as job autonomy and task significance which ultimately affect employee task outcome. Sharif and Scandura (Citation2014) submitted that subordinates who value the continuous ethical behaviour of the leader reciprocate by being highly involved in the job. Subordinates are more involved in organisational task because they feel confident that the leaders will make legitimate decisions. Again, Mayer et al. (Citation2009) exposed that top management who are perceived to be ethical, positively affect group job involvement of employee. We, therefore, hypothesize that:

H2: Ethical leadership style is significantly related to EJI.

2.3. Moderating effect of workplace spirituality

Workplace spirituality is an emerging concept in organisational management. Workplace spirituality refers to the inclusion of spirituality principles (community, connectedness, belonging, purpose, altruism, and virtue) into work activities (Pawar, Citation2009). The spiritual principles are intrinsic to an individual and they reflect in the individual’s behaviour and work activities. Kolodinsky et al. (Citation2008) posit that workplace spirituality is in two levels: micro-level (i.e. the fusion of the individual spiritual principles and values into the work), and macro-level (i.e. the totality of individual spirituality at the workplace and how these spiritual value influence ethical-related and unethical-related issues to determine the level of corporate spirituality and how it influence outcomes). Workplace spirituality is more of a macro-level view of the organisation spirituality in the form of ‘spiritual climate’ (Parboteeah & Cullen, Citation2003). Whereas individual spirituality is the personal spiritual values employees bring to the workplace, workplace spirituality is the perception of the spiritual climate of the organisation (Garcia-Zamor, Citation2003). Spirituality at the workplace is the expression of a sense of belonging, community, wholeness at the individual level, which culminates into organisation spirituality (Krnjerski & Skrypnek, 2004).

Workplace spirituality has gained recognition in contemporary times due to the over reliance of financial metrics in determining corporate success, coupled with the managerial greed of the 1980s (Lennick & Kiel, Citation2005). These happenings have created job insecurity among employees and a non-humanistic work environment where leaders do whatever it takes to keep up the pace and positively affect the organizational bottom line without taking into consideration employee spiritual values. However, many employees believe that work life is just an important existential requirement, but not an end in itself. A significant relationship was found between workplace spirituality and EJI, suggesting that spirituality is a significant predictor of job involvement among employees (Mahipalan & Sheena, Citation2019). Given that transformational and ethical leadership styles influence EJI and workplace spirituality also affect job involvement, we predict that workplace spirituality will moderate the relationship between transformational and ethical leadership styles and EJI on the basis that leadership spirituality principles i.e. the sense of community, connectedness, belonging, purpose, altruism, and virtue creates a spirituality climate which influence EJI. Hence, we hypothesize that:

H3a: Workplace spirituality moderates the relationship between transformational leadership (idealized influence) and EJI

H3b: Workplace spirituality moderates the relationship between transformational leadership (inspirational motivation) and EJI

H3c: Workplace spirituality moderates the relationship between transformational leadership (intellectual stimulation) and EJI

H3d: Workplace spirituality moderates the relationship between transformational leadership (individualised consideration) and EJI

H4: Workplace spirituality moderates the relationship between ethical leadership and EJI

3. Research design

3.1. Study designs and approach

This study adopted descriptive and cross-sectional survey designs to examine the association between the independent variables (transformational and ethical leadership) and the dependent variable (EJI), moderated by workplace spirituality. A descriptive study describes a phenomenon and conclusions while a cross-sectional study involves the collection of data at a single moment from the population of interest (Zikmund et al., Citation2010). The cross-sectional survey design was employed because apart from enabling data to be collected at a single moment from the population of interest (Zikmund et al., Citation2010); it facilitates the planning of data collection to achieve the research objectives (Altinay et al., Citation2015). In investigating the relationship, the quantitative research approach, which is usually employed under survey design was adopted (Saunder et al., Citation2016). This approach is helpful to collect numeric data to test the research hypotheses.

3.2. Population and sampling

The population of interest for this study was employees of private and public universities in Ghana. The target population included operational level employees (non-teaching staff) of ten (10) selected universities (i.e. five each from private and public universities) within the Accra, Tema and Kumasi metropolises. These metropolises constitute the main tertiary education hub of Ghana and virtually all the universities have their main and/or satellite campuses located within these areas, making these metropolises a fair representative of the tertiary education workers in Ghana.

The universities were purposively selected using the homogenous purposive sampling technique while the respondents were conveniently selected in accordance with Patton’s (Citation2002) sample size selection criterion (i.e. for non-probability study, the sample size depends on the objectives with a minimum consideration not less than 100 participants), which has been widely applied in similar studies (such as Hilton et al. Citation2021; Hilton et al., Citation2023; Martins, Citation2023; Puni et al., Citation2021, etc.). The sampling techniques allowed the researchers to select respondents with rich information (i.e. have direct supervisors and have been working consistently with the same supervisor or manager for not less than three academic years) (Etikan et al., Citation2016). In all, 500 respondents were chosen from the ten (10) selected universities with fifty (50) respondents from each selected university.

3.3. Instrumentation and data collection

Cross-sectional data were collected using a questionnaire. The questionnaire contained adapted items from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) 5X short (Avolio & Bass, Citation2004), ethical leadership scale (Brown et al., Citation2005), EJI scale (Kanungo, Citation1979; Fletcher, 1998) and workplace spirituality scale (Petchsawanga & Duchon, Citation2012). A five-point likert scale ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1) was provided for the measuring items. The first section of the instrument collected demographic data from respondents (i.e. gender, age, marital status, and educational level). The second section of the instrument collected data on the dimensions of transformational leadership (idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration). Sample items from the MLQ 5X short include the following: Idealized Influence (e.g. ‘consider followers’ needs over his or her own needs’), Inspirational Motivation (e.g. ‘arouses individual and team spirit’), Intellectual Stimulation (e.g. ‘approaches old situations in new ways’), Individual Consideration (e.g. ‘pay attention to individual needs for achievement and growth’). The third section of the instrument gathered data on the behaviours of ethical leadership. Sample item from the ethical leadership scale is ‘my supervisor conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner’. The fourth section collected data on workplace spirituality. Sample item from the workplace spirituality scale is ‘employees can easily put themselves in other people’s shoes’. The final section collected data on EJI, with a sample item: ‘the most important things that happen to me involve my present job’.

In order to ensure non-response bias, we employed the procedural strategies prescribed by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003). We kept the surveys short and simple (it took 5–10 minutes to complete a questionnaire), separated the variables (i.e. independent, dependent and moderator), provided instructions on how to respond to increase the probability of response accuracy, assured the respondents of confidentiality and anonymity, developed a relationship with the respondents, and sent reminders to respond (Hair et al., Citation2015; Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). At the end of the survey, which lasted for six weeks, 416 questionnaires were validly retrieved. However, since the validly retrieved questionnaires constituted 83.2% of the sample size, we proceeded with the analysis as the sample size satisfied the Tabachnick et al. (Citation2001) criteria for determining adequate sample size.

Although the items were adapted from existing instruments, the researchers carried out validity and reliability tests to verify whether there were invalid items in the scales and to ensure that the instrument validly measures the research objectives (Dawson, Citation2009). Inter-construct correlation analysis was then conducted and the results in show that the scales are predictively valid. Furthermore, Cronbach alpha was calculated to confirm the internal consistency of the instrument (i.e. the reliability). The results in indicate that the scales in the instrument are strongly reliable as the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeded the 0.7 prescribed threshold by Field (Citation2015), meaning that the instruments are valid and reliable for the study.

3.4. Data analysis

We analysed the data using descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation and Cohen et al.’s (Citation2003) hierarchical regression model. Before we carried out the regression analysis, we first conducted a normality test to confirm that the data was normally distributed to proceed with a parametric analysis. This was done using the skewness and kurtosis as recommended by Tabachnick et al. (Citation2001), supported by Fields (Citation2009), and applied by scholars such as Hilton et al. (Citation2023), Hilton et al. (Citation2021), Puni et al. (Citation2021), etc. The descriptive statistics analysis reported the mean, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis. The correlation matrix analysis presented the inter-construct correlation. The hierarchical regression analysis established the following: (1) predictive effect of the transformational and ethical leadership on EJI; (2) controlling effect of workplace spirituality; and (3) moderating effect of workplace spirituality on the relationship between the transformational, ethical leadership and EJI. Finally, Hayes’ (Citation2018) Process was employed to draw scatter plots for the interaction effects.

4. Empirical findings

presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents. The table indicates that the sample had more males (51%) than females (49%). In a descending order, 40% of the respondents were aged between 31and 40 years, 26% of respondents were aged between 21 and 30 years, 25% of respondent were aged between 41 and 50 years, and 9% of respondents were aged between 51 and 60 years. Regarding marital status, more than half of the respondents were married (60%). In terms of educational background, majority of the respondents hold first degree (44%); followed by holders of masters’ degree (33%), with the least holding HND/Diploma certificate (11%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents.

presents the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of the study variables. First, the mean results show that all the dimensions of transformational leadership are practiced in the selected universities, with idealized influence being the dominant dimension. Furthermore, the mean score for ethical leadership indicates that it is also practiced by supervisors or managers in the selected universities. Comparing the means of the two leadership constructs, it can be concluded that all the dimensions of transformational leadership are practiced more than ethical leadership. The result suggests that because universities want to remain centres of innovation, transformational leadership behaviours are encourage and practiced by leaders of the selected universities. This empirical result supports prior argument by Northouse (Citation2016) that transformational leadership is more frequently practiced than the other leadership styles. Generally, the standard deviation values indicate that there are relative variations in the responses obtained. Applying the criterion of Tabachnick et al. (Citation2001) on normality, it is concluded that the data is parametric (i.e. normally distributed) since the Skewness and Kurtosis are between −1 and +1, meaning that a regression analysis can be carried out.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for study variables.

depicts the correlation matrix and the Cronbach alpha (α) coefficients. The correlation results are significant at 1 and 5% level of significance. indicates that all the dimensions transformational leadership are positively and significantly related to the other variables (ethical leadership, workplace spirituality, and EJI). More importantly, both independent variables (transformational and ethical leadership) and moderating variable (workplace spirituality) have significant positive correlations with the dependent variable (EJI). These results imply that both independent and moderating variable could significantly predict EJI. Hence, a formal augmentation analysis was carried. Additionally, an interactive effect analysis was also done to establish the moderating effect of workplace spirituality on relationship between the leadership constructs and EJI.

reports the summary of the hierarchical regression analysis. The table contained five blocks where block 1 to block 4 relate to the transformational leadership dimensions and block 5 relates to ethical leadership. Each block contained three steps where step 1 relates to the individual entry of the transformational leadership dimensions and ethical leadership; step 2 relates to the entry of both leadership constructs as independent variables and workplace spirituality as controlling variable; and step 3 relates to the inclusion of the interactive term of the leadership construct and workplace spirituality. The three-step procedure was followed to test the following: the effect of the leadership constructs on EJI (step 1), the augmentation effect of workplace spirituality (step 2), and the moderating effect of workplace spirituality on relationships between the leadership constructs and EJI (step 3). The unstandardized beta coefficients and t-statistics have been presented in three models: model 1 relates to step 1, model 2 relates to step 2, and model 3 relates to step 3. The R-square, adjusted R-square and F-statistics are all significant, meaning that the leadership constructs and workplace spirituality contribute significantly to change in EJI.

Table 3. Correlation matrix and Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 4. Regression results for employee job involvement.

From , the unstandardized beta coefficients in model 1 for all the dimensions of transformational and ethical leadership are significant, indicating that the dimensions of transformational leadership and ethical leadership have significant relationship with EJI. Hence, H1a, H1b, H1c, H1d and H2 are supported. Specifically, idealized influence has the highest effect (with coefficient of 0.305), followed by individualized consideration (0.274 coefficient) and inspirational motivation (0.265 coefficient), with intellectual stimulation being the least (0.251 coefficient). However, the transformational leadership dimensions have stronger effect on EJI compared to the effect of ethical leadership (0.222 coefficients). These results suggest that improvement in these leadership constructs will likely lead to corresponding significant improvement in EJI by the magnitudes of their various coefficients.

The findings above confirm prior literature by Cheng et al. (Citation2012) which established positive relationship between transformational leadership and subordinates’ job involvement among 210 soldiers from eight companies of the Taiwanese Army. Again, the current findings are consistent with Dwirosanti’s (Citation2017) work that showed significant relationship between transformational leadership dimensions and job involvement. Similarly, our findings supports the findings of Nazem and Mozaiini (Citation2014) that transformational leadership dimensions have significant relationship with EJI. Though these studies are not conducted in the same jurisdictions, the similarity in methodology may account for the consistency in the findings. It follows that the practice of transformational leadership is critical in improving EJI in both developed and developing economies. Despite the similarities in the findings aforementioned with the current study, none of the prior studies controlled the relationship or tested for a possible moderator on the relationship. The inclusion of an intervening variable may change the results since it is impracticable that other organizational factors may not enhance or impede the direct relationship between transformational leadership and EJI. This is because workplace climate cannot be overlooked when assess the determinants of organizational outcomes. Literature shows that workplace climate influences job involvement (Wood, Citation2020). As such, earlier studies could have assessed whether this assertion hold true across different jurisdictions given the importance of transformational leadership in predicting organizational outcomes. This study, therefore, augments existing literature by testing whether workplace spirituality increases or decreases the effect of transformational leadership on EJI.

Furthermore, our findings are consistent with Piccolo et al. (Citation2010) which established that ethical leadership influences EJI characteristics such as job autonomy and task significance which ultimately affect employee task outcome. Similarly, this study supports Sharif and Scandura (Citation2014) who revealed that subordinates who value the continuous ethical behaviour of the leader reciprocate by being highly involved in the job. Our findings suggest that leaders who are ethical have positive effect on their employees’ job involvement as underscored by Mayer et al. (Citation2009) that top management who uphold ethical principles positively affect job involvement of employees. Nonetheless, this study illustrates that other relevant leadership styles like transformational leadership could be considered alongside ethical leadership. Additionally, this study demonstrates the possible interference of the relationship between ethical leadership and EJI by workplace spirituality as an emerging concept in Africa where there is dearth of literature.

Under model 2, the controlling effect of workplace spirituality in step 2 is significant, indicating that workplace spirituality contributes to explaining the variance in EJI. Again, the initial entry of workplace spirituality as a predictor indicates unstandardized beta coefficient of 0.23 [see note to ]. Comparing this to the coefficients in model 1, it can be concluded that workplace spirituality could augment ethical leadership. On the contrary, workplace spirituality could not augment all the dimensions of transformational leadership.

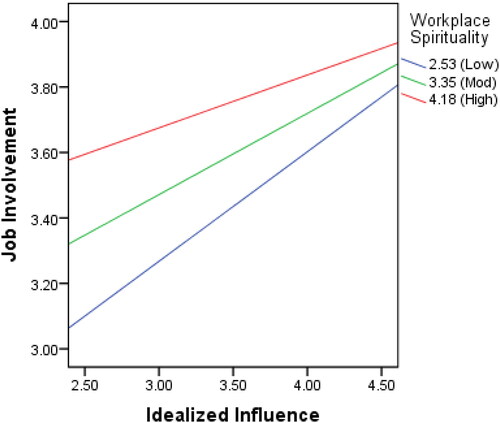

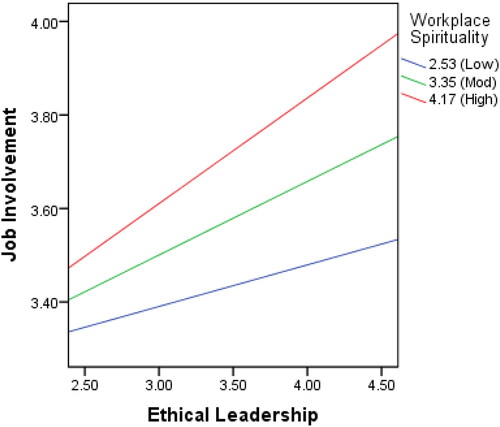

Moderation effect of workplace spirituality

Similar to prior studies on moderating analysis (Aiken et al., Citation1991), we tested the moderation effect by creating multiplicative interaction terms. The variables were centred on a mean of 0 to reduce the correlation between the interactive term and the variables comprising the interaction to prevent the possibility of high multicollinearity. From , the results in model 3 show that the analysis of the interaction effect reveal significant effect for idealized influence and ethical leadership. This means that idealized influence dimension of transformational leadership and ethical leadership are significantly moderated by workplace spirituality. Hence, only H3a and H4 are supported. This result implies that increasing the moderator (workplace spirituality) would increase the effect of the idealized influence and ethical leadership on EJI. However, workplace spirituality could not moderate inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration, since the results in model 3 for these dimensions are not significant. Since workplace spirituality is an effective moderator of ethical leadership, H4 is therefore accepted.

Furthermore, the significant interaction effects are plotted on a scatter graph in and using Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS procedure for SPSS version 3.4.1. The values used to graph the interactions are the mean and +/−SD from the mean generated from the conditional effect of the moderator (workplace spirituality). The slopes of the scatter plot indicates that ethical leadership and idealized influence have less positive effect under low level of the moderator compared to the high level of the moderator. Thus, for universities that have high workplace spirituality environment, ethical leadership and idealized influence have a stronger effect on EJI than environment of low workplace spirituality.

Even though this finding is without precedence, it provides empirical justification of how effective idealized influence and ethical leadership could impact EJI through an interaction effect of workplace spirituality. This finding also affirms that workplace spirituality is a significant predictor of EJI as earlier ascertained by Mahipalan and Sheena (Citation2019). It follows that once employees feel a sense of belonging, community, wholeness at the individual level, which culminates into organisation spirituality (Kinjerski & Skrypnek, Citation2004), idealized influence and ethical leadership will be enhanced to effectively impact EJI. This finding further clarifies that not all the dimensions of transformational leadership requires workplace climate like spirituality to more significantly influence EJI. Hence, this study makes a pioneer contribution to extant literature from a developing context ( and ).

5. Conclusion

We examine the moderating effect of workplace spirituality on the relationship between transformational, ethical leadership and EJI. We discover that the four dimensions of transformational leadership and ethical leadership are practiced by registrars, administrators, heads of departments and deans in Ghanaian universities with idealized influence being the dominant dimension. We further establish that the four dimensions of transformational leadership and ethical leadership have significant positive association with EJI. Again, this study reveals that workplace spirituality can augment ethical leadership but not the dimensions of transformational leadership. Lastly, whereas workplace spirituality moderates ethical leadership and EJI, it only moderates the relationship between idealized influence behaviour of transformational leadership and EJI. Our findings have proven that the assessment of transformational leadership style without emphasis on the dimensions will not show its true effect on organizational outcomes like EJI. It is further instructive to note that a leader may exhibit one or all of the dimensions of transformational leadership. Given the presence of workplace spirituality, only transformational leaders who exhibit idealized influence behaviour will show an enhanced effect on EJI.

The practical implications of our findings include the following. First, since the mean values of responses were on the average, registrars, deans and heads of departments of the various universities have to encourage transformational and ethical leadership styles through training and seminars to increase EJI. Secondly, the dimensions of transformational leadership and ethical leadership were found to have significant positive influence on EJI. Therefore, the human resource directorates of various universities should organise leadership workshops for registrars, deans, heads of departments and administrators to enhance these leadership styles for a corresponding improvement in EJI. Lastly, workplace spirituality is an effective moderator of ethical leadership and idealized influence behaviour of transformational leadership, thus deliberate work culture (such as inclusion and diversity) should be inculcated into university management practices to enhance EJI. There must be deliberate attempt to encourage spirituality principles such as connectedness, belonging, purpose, altruism, and virtue in work activities.

Theoretically, our findings suggest that it is inappropriate to generalize the effect of transformational leadership on organizational outcomes or work-related activities without recourse to the specific dimensions. Although transformational leadership is regarded as the most exhibited leadership style across different set of organizations (Adnan & Haider, Citation2010; Men & Stacks, Citation2013), the focus on the specific dimensions in this study showed that only idealized influence could influence EJI and be moderated by workplace spirituality. Hence, as a construct, transformational leadership could be better explained relative to organizational outcomes by focusing on the dimensions rather the overall construct which may provide bias estimates and misleading findings. Again, contributing to theoretical assertions, this study demonstrates that workplace spirituality has strong interaction effect with ethical leadership which was unexplored in the past. Therefore, this study provides empirical basis to propose a link between ethical leadership and workplace spirituality constructs.

Our study is limited in the following ways. We focused on only two leadership constructs could not give a comprehensive view of how leadership styles may influence EJI. Hence, the generalization of these findings may not be appropriate in institutions where transformational and ethical leadership styles are not predominantly practiced. Again, while this study may be useful in different sectors or countries, the application of the findings in decision making must be done cautiously because of the possible cross-country cultural difference or industry-specific requirements. Therefore, future research may consider addressing any of the limitations above, especially with regards to testing other leadership styles, workplace spirituality and EJI in other sectors and jurisdictions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2355042).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sam Kris Hilton

Sam Kris Hilton is an economist and leadership scholar. He is the Chief Research Officer of Kricet Insight, London, UK. He also teaches Applied Macroeconomics and Managerial Economics at the College of Distance Education of the University of Cape Coast. Kris’ research interests include Macroeconomics, Entrepreneurship, Leadership, and Ethics.

Albert Puni

Albert Puni is a Professor of Management at the University of Professional Studies, Accra, Ghana. His research interests include leadership, corporate governance, entrepreneurship and business ethics. Prof. Puni is a former Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, Faculty of Management Studies, and Distance Learning School.

Eric Yeboah

Eric Yeboah is a minister of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, currently the District Minister at Adweso, Koforidua. He has developed himself in the sphere of leadership, impacting and transforming lives to meet generational needs. He holds an MPhil in Leadership from the University of Professional Studies, Accra.

References

- Adnan R. & Haider, M. H. (2010). Role of transformational and transactional leadership on job satisfaction and career satisfaction, Business and Economic Horizons (BEH). Prague Development Center, 1(1), 29–38.

- Acheampong, A., & Agyapong, K. (2015). The links between workplace spirituality, job involvement and workplace deviance. Department of Management Studies Education, University of Education.

- Adnan, N., Khalid, O. B., & Farooq, W. (2020). Relating ethical leadership with work engagement: How workplace spirituality mediates? Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1739494

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Ajala, M. E. (2013). The impact of workplace spirituality and employees’ wellbeing at the industrial sector: The Nigerian experience. The African Symposium, 13(2), 3–13.

- Al-Sada, M., Al-Esmael, B., & Faisal, M. N. (2017). Influence of organizational culture and leadership style on employee satisfaction, commitment and motivation in the educational sector in Qatar. EuroMed Journal of Business, 12(2), 163–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-02-2016-0003

- Altinay, L., Paraskevas, A., & Jang, S. S. (2015). Planning research in hospitality and tourism. Routledge.

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2004). Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire: Manual and sampler set (3rd ed.). Mind Garden.

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership: good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(85)90028-2

- Bayraktar, C. A., Araci, O., Karacay, G., & Calisir, F. (2017). The mediating effect of rewarding on the relationship between employee involvement and job satisfaction. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 27(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20683

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A., Hetland, J., Demerouti, E., Olsen, O. K., & Espevik, R. (2014). Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12041

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

- Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper Torch books.

- Cheng, Y. N., Yen, C. L., & Chen, H. L. (2012). Transformational leadership and job involvement: The moderation of emotional contagion. Military Psychology, 24(4), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2012.695261

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cortes, A. F., & Herrmann, P. (2019). CEO transformational leadership and SME innovation: The mediating role of social capital and employee participation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 24(03), 2050024. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919620500243

- Dawson, C. (2009). Introduction to research methods: A practical guide for anyone undertaking a research project (4th ed.). How to Books.

- Dwirosanti, N. (2017). Impact of transformational leadership, personality and job involvement to organizational citizenship behavior. IJHCM (International Journal of Human Capital Management), 1(02), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.21009/IJHCM.012.04

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Sampling and purposive sampling. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Field, A. P. (2015). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll (4th Ed.). Sage.

- Fields, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Garcia-Zamor, J. C. (2003). Workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Public Administration Review, 63(3), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00295

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Wolfinbarger, M., & Money, A. H. (2015). Essentials of business research methods. Routledge.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hettie, A. R., & Robert, J. V. (2005). Integrating managerial perceptions and transformational leadership into a work-unit level model of employee. Involvement Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(5), 561–589.

- Hilton, S. K., & Arkorful, H. (2021). Remediation of the challenges of reporting corporate scandals in governance. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 37(3), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-03-2020-0031

- Hilton, S. K., Arkorful, H., & Martins, A. (2021). Democratic leadership and organisational performance: The moderating effect of contingent reward. Management Research Review, 44(7), 1042–1058. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-04-2020-0237

- Hilton, S. K., Madilo, W., Awaah, F., & Arkorful, H. (2023). Dimensions of transformational leadership and organizational performance: The mediating effect of job satisfaction. Management Research Review, 46(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2021-0152

- Kanungo, R. N. (1979). The concepts of alienation and involvement revisited. Psychological Bulletin, 86(1), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.86.1.119

- Kia, N., Halvorsen, B., & Bartram, T. (2019). Ethical leadership and employee in-role performance: The mediating roles of organisational identification, customer orientation, service climate, and ethical climate. Personnel Review, 48(7), 1716–1733. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2018-0514

- Kinjerski, V., & Skrypnek, B. J. (2004). Defining spirit at work: Finding common ground. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810410511288

- Kolodinsky, R. W., Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2008). Workplace values and outcomes: Exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9507-0

- Lennick, D., & Kiel, F. (2005). Moral intelligence. Wharton University of Pennsylvania.

- Lodahl, T. M., & Kejner, M. M. (1965). The definition and measurement of job jnvolvement. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 49(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021692

- Mahipalan, M., & Sheena, S. (2019). Workplace spirituality, psychological well-being and mediating role of subjective stress. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 35(4), 725–739. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-10-2018-0144

- Martins, A. (2023). Dynamic capabilities and SME performance in the COVID-19 era: The moderating effect of digitalization. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 15(2), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-08-2021-0370

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002

- Men, L. R., & Stacks, D. W. (2013). The impact of leadership style and employee empowerment on perceived organizational reputation. Journal of Communication Management, 17(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632541311318765

- Molodchik, M., Jardon, C., & Yachmeneva, E. (2021). Multilevel analysis of knowledge sources for product innovation in Russian SMEs. Eurasian Business Review, 11(2), 247-266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-020-00166-6

- Nazem, F., & Mozaiini, M. (2014). Validation scale for measuring organizational learning in higher educational institutes. European Journal of Experimental Biology, 4(1), 21–27.

- Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed.), Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Ohemeng, F. L. K., Amoako-Asiedu, E., & Obuobisa, D. T. (2018). The relationship between leadership style and employee performance: An exploratory study of the Ghanaian public service. International Journal of Public Leadership, 14(4), 274–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-06-2017-0025

- Parboteeah, K. P., & Cullen, J. B. (2003). Ethical climates and workplace spirituality: An exploratory examination of theoretical links. In R. A. Giacalone & C. L. Jurkiewicz (Eds.), Handbook of workplace spirituality (pp.137–151). Sharpe, Armonk.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. (3rd ed.), Sage.

- Pawar, B. S. (2009). Workplace spirituality facilitation: A comprehensive model. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0047-7

- Petchsawang, P., & Duchon, D. (2012). Workplace spirituality, meditation, and work performance. Journal of Management Spirituality & Religion, 9(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2012.688623

- Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., Den Hartog, D. N., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.627

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Puni, A., Hilton, S. K., & Quao, B. (2021). The interaction effect of transactional-transformational leadership on employee commitment in a developing country. Management Research Review, 44(3), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2020-0153

- Rasheed, M. A., Shahzad, K., & Nadeem, S. (2020). Transformational leadership and employee voice for product and process innovation in SMEs. Innovation & Management Review, 18(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/INMR-01-2020-0007

- Rego, A., & Cunha, M. P. (2008). Workplace spirituality and organisational commitment: An empirical study. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 21(1), 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810810847039

- Richardson, A. H., & Vandenberg, R. (2005). Integrating managerial perceptions and transformational leadership into a work‐unit level model of employee involvement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(5), 561–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.329

- Saunder, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students (7th Ed.). Pearson Education.

- Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4(4), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.4.4.577

- Shamir, B., Zakay, E., Brainin, E., & Popper, M. (2000). Leadership and social identification in military units: DIRECT and indirect relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(3), 612–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02499.x

- Sharif, M. M., & Scandura, T. A. (2014). Do perceptions of ethical conduct matter during organizational change? Ethical leadership and employee involvement. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1869-x

- Stock, R. M., & Schnarr, N. L. (2016). Exploring the product innovation outcomes of corporate culture and executive leadership. International Journal of Innovation Management, 20(01), 1650009. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919616500092

- Suifan, T. S., Diab, H., Alhyari, S., & Sweis, R. J. (2020). Does ethical leadership reduce turnover intention? The mediating effects of psychological empowerment and organizational identification. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(4), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2019.1690611

- Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Osterlind, S. J. (2001). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson Education.

- Thamrin, H. M. (2012). The influence of transformational leadership and organizational commitment on job satisfaction and employee performance. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 3(5), 566–572. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIMT.2012.V3.299

- Toor, S-u-R., & Ofori, G. (2009). Ethical leadership: Examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organizational culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0059-3

- Treviño, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2004). Managing to be ethical: Debunking five business ethics myths. Academy of Management Perspectives, 18(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2004.13837400

- Van der Walt, F., & De Klerk, J. J. (2014). Workplace spirituality and job satisfaction. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(3), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.908826

- Van der Walt, F., & Swanepoel, H. (2015). The relationship between workplace spirituality and job involvement: A South African study. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 10(1), 95–116.

- Wan Omar, W. A., & Hussin, F. (2013). Transformational leadership style and job satisfaction relationship: a study of structural equation modeling (SEM). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(2), 346–365.

- Wood, S. (2020). Human resource management–performance research: Is everyone really on the same page on employee involvement? International Journal of Management Reviews, 22(4), 408–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12235

- Zikmund, W. G., Babin, B. J., Carr, J. C., & Griffin, M. (2010). Business research methods (8th Ed.), Cengage Learning.