Abstract

This study aims to investigate the new generation’s behavior, influencing VR satisfaction and behavioral intention toward destinations. To this end, this paper investigated whether subjective norms, attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and VR satisfaction of the new generation positively impacted the behavioral intention to visit actual destinations. A convenient sampling method was used to collect data from students via an online survey by many universities in Thailand. The sample has been classified as people who used VR applications for tourism earlier answering the survey. The results revealed that attitude and perceived behavioral control had a positive and significant influence on VR satisfaction and an indirect effect on behavioral intentions. Moreover, VR satisfaction positively and significantly influenced behavioral intentions toward actual destinations. This study empirically investigates the influence of virtual reality on the new generation’s behavior by using VR applications and other devices to access destinations. However, the results are valuable insight for destination marketing organizations to enhance the sophisticated technology that develops sites for new generations of tourism destinations. The current study provides specific theoretical and practical implications for further study.

IMPACT STATEMENT

This article applied the theory of plan behavior to investigate the virtual reality satisfaction in tourism destinations that influences behavioral intention to visit the actual tourism destinations. The highlight of this article is to test the new generation who use virtual reality applications, particularly utilizing the VR application for hospitality and tourism destinations. The research method applied confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the empirical model in order to find the behavioral intentions of the new generation toward the hospitality and tourism context. The analysis process employed showed that attitude, perceived behavioral control, and virtual satisfaction had a positive significant impact on behavioral intention to visit actual tourism destinations. The results of this article are valuable insights into theoretical and practical implications for destination marketing organizations.

Reviewing Editor:

SUBJECTs:

Introduction

COVID-19 has changed the hospitality and tourism industries around the world. Many countries have implemented travel restrictions, lockdowns, social distancing, and measuring many regulations as a result of COVID-19. However, COVID-19 has also changed customer perceptions, habits, and behavior, affecting people even after the pandemic has ended (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020). For COVID-19, people prefer to use technology to mediate travel for health and safety reasons. That is decision-making before the intention of visiting a destination. Particularly, in the context of hospitality and tourism, people have been gradually pursuing an experience through technological and new innovations such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to obtain and satisfy their experience in a destination via those devices (Bec et al., Citation2021; Deb & Lomo-David, Citation2021; Kwok & Koh, Citation2021; Wen & Leung, Citation2021). Therefore, new technology has interested many people around the world, especially in virtual reality, which helps people prevent COVID-19. The VR application for tourism is the one system that could support people to interact with new experiences (Manchanda & Deb, Citation2022).

Currently the new generation is using VR in the context of hospitality and tourism. This is the virtual approach to accessing the hospitality and tourism context that uses equipment and other devices to access content such as smartphones, computers, and wearables to integrate digital devices and destination atmospheres (Moon & Han, Citation2018). People who use the VR application could obtain the virtual world experience through their senses such as visual, auditory, and gustatory that are close to their lives (Caissie et al., Citation2021). Therefore, VR application for tourism is significant to satisfy and amend the new generation’s behavioral intention to travel to a destination. This technology highlights the intensifying interest and effort to enhance technological capabilities in tourism destinations, including the integration of technological digital and innovation for the enhancement of the consumer experience in tourism destinations (Buhalis & Amaranggana, Citation2014; Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2013).

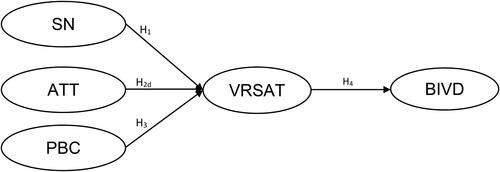

New VR applications and device technology indicate access to realistic virtual experiences in the destinations in this context. These applications and devices are expected to have a positive impact on hospitality and tourism experiences (Tussyadiah, Citation2014). It is included in the first step to visiting the destinations, and interest and anticipation lead to creating in tourists’ expectations and minds (Jung et al., Citation2017, Neuhofer et al., Citation2012, Neuhofer et al., Citation2015). However, empirical studies have not sufficiently explored how virtual reality experiences affect new generations’ behavioral intentions to visit destinations. To fulfill this gap in the hospitality and tourism fields, the purpose of this study is to investigate the behavior of new generations’ VR experiences with VR applications and every device to enhance the behavioral intentions toward tourism destinations based on the conceptual underpinning of VR satisfaction and behavioral intentions of the new generation. The significance of the study has been applied to the theory of plan behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Sadiq et al., Citation2022; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2021), satisfaction (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Rahimizhian et al., Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022); and behavioral intentions toward tourism destinations following use of VR application (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022). This study investigates the relationship between the new generations’ behavioral factors, VR satisfaction, and behavioral intention, considering VR satisfaction as a mediating factor. The behavioral intention construct, based on (Hamid & Bano, Citation2021; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2021) offers the opportunity to determine the possibility of an indirect connection between the new generations’ behavior factors and behavioral intentions, mediating through VR satisfaction.

The conceptual model used in this study was behavioral intention to visit hospitality and tourism destinations as a construct that could be influenced by behavioral factors and new generation VR satisfaction. In the previous study, scholars have always investigated virtual reality, augmented reality, and tourism experiences (Atzeni et al., Citation2022; Loureiro, Citation2020; Manchanda & Deb, Citation2022; Schiopu et al., Citation2022; Zeng et al., Citation2022). These studies found that behavioral intentions toward destinations can be affected by the new generations’ behavior factors and VR satisfaction. It is a new strand of study into the relationship between these constructs. Thus, this study should consider the new generation of behavioral factors and VR satisfaction in relation to behavioral intentions when visiting destinations to provide a better understanding of the relationship between these constructs. The purpose is to fill the gap in knowledge by the following questions: How do the subjective norm, attitude, and perceived behavioral control affect VR satisfaction? How does VR satisfaction influence behavioral intention to visit the actual destinations afterward using the VR application and other devices toward destinations? and How can we apply those factors to build behavioral intention in destinations? Therefore, the objectives of this study will be to investigate the new generation’s behavior factors affecting VR satisfaction and the behavioral intention toward destinations, propose a conceptual model based on theory, examine the relationships among factors, and provide theoretical and practical implications.

The findings may contribute to theoretical and practical implications on the importance of behavioral intention, experiences from the new generation, and perspectives in predicting essential tourist behaviors in VR tourism. Furthermore, the study explains that VR tourism facilitates users’ virtual exploration of destinations and attractions during and post COVID-19. Mainly, this study explains the behavior of the new generation using VR tourism as a virtual representation of actual destinations, attractions, locations, experiences, and satisfaction toward users’ behavior. The practical contribution of this study reveals that the new generation is increasingly interested in VR tourism as a distinctive enjoyment technology. This study also provides practical implications for VR tourism stakeholders. In addition, the findings provide suggestions for marketing in the hospitality and tourism sector that consider customer behavior throughout VR tourism experiences. Particularly, VR tourism developers are encouraged to focus on creating authentic experiences that stimulate behavior, eventually creating VR users’ attachment and visit intention to tourism destinations.

Theoretical background

New generation

As the world evolves, a new generation of visitors emerges. The post-1980s, the 1990s, and even the 2000s have become an irresistible force in tourism consumption. The new generation of visitors differs significantly from conventional tourists regarding consumption ideas, choices, and behavior. They have consuming capacity, seek products or services congruent with their emotions, and emphasize customer satisfaction more. Furthermore, the new generation of visitors values participation experiences more. For example, the free travel desired by the post-1990s generation is accomplished by themselves or by mutual support from itinerary planning, plane tickets, and hotel reservations through the resolution of numerous difficulties encountered. The new generation of visitors indicates strong emotional consumption, emphasizing the emotional worth of consumer items, prominent sensory consumption, and a focus on style and personalities. Tourists’ tourism consumption behavior accompanies and extends throughout the consumer behavior process.

Strauss and Howe (Citation2008) highlighted one of the most recent generations, the post-millennials or Gen-Z, emphasizing that the boundary between them and the Millennials is not apparent. Post-millennials are digital natives, the original advocates of the new mobilities paradigm (Urry & Sheller, Citation2006), a generation identified by increased mobility among people and things (Urry & Sheller, Citation2012). Post-Millennials’ lives are strongly affected by the usage of modern technology, with which they have been convinced from a young age (Combi, Citation2015; Michael, Citation2011; Pandit, Citation2015). According to specific research, the young are distinguished as customers by their unparalleled awareness, determination, and familiarity with digital technology (Koulopoulos & Keldsen, Citation2016). In the coming decade, they will be the most willing to participate in the tourism market.

Theory of plan behavior (TPB) and VR satisfaction

The TPB is a component of rational behavior theory that concerns behavior that is not ultimately controlled by a person’s intention (Conner, Citation2020; Hagger et al., Citation2022). There are analyses of destination behavior intention as a component of three different factors: (1) an individual’s attitude toward behavior, (2) subjective norms, and (3) perceived behavioral control (Hrubes et al., Citation2001). This study examines the behavior of a new generation regarding their intention to visit a destination after using a virtual reality application. Despite research confirming the TPB, few academics have proposed extending it to improve predictive relevance. Furthermore, Ajzen and Pratkanis (Citation1989) highlighted that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are multidimensional, which may also result in positive and negative views of the same dimensional counteracting each other, influencing the final research findings. Taylor and Todd (Citation1995) addressed the challenge by integrating Ajzen’s TPB with Davis’ technology acceptance model (TAM) to develop the deconstructed TPB. Throughout this approach, unidimensional concepts are reconstructed into multidimensional beliefs, causing the relationships with both antecedent factors and belief dimensions to be employed to clearly and explicitly clarify the factors that impact behavioral intentions and behavioral performance.

Previous studies employed it in a similar method to discuss consumers’ intentions to use new application services such as Internet banking (Nasri & Charfeddine, Citation2012) and online shopping (Lin, Citation2007); customers’ intentions to use new technology (Kanimozhi & Selvarani, Citation2019; Sadiq et al., Citation2022; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2021); young generations’ continued intention to engage with the virtual world (Mäntymäki et al., Citation2014); and consumers’ intention to explore online games (Chang et al., Citation2014). The new generation is concerned with technology and innovation, which influences daily life. Tourism and hospitality businesses have investigated the new generation’s behavior toward virtual reality tourism and behavioral intention using VR applications to substitute actual travel. In particular, the hospitality business found that hotel guests’ experiences of using technology as self-service had an encouraging effect on behavioral intentions to use the innovation in the hotel (Kim & Qu, Citation2014). Studies by Chang et al. (Citation2014) found that customers’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control have a significant positive impact on the behavioral intention of using a new application service. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Subjective norm has a positive effect on VR satisfaction using virtual reality to visit the destination.

H2: Attitude has a positive effect on VR satisfaction using virtual reality to visit the destination.

H3: Perceived behavior control has a positive effect on VR satisfaction using virtual reality to visit the destination.

VR satisfaction and behavior intention

Satisfaction is defined as the extent to which a service or product’s experience satisfies customers’ expectations (Li et al., Citation2021). Consumers are satisfied because of their experience with cognitive and affective evaluations of a service or product. Digitalization in tourism is initially associated with delivering insights into destinations that may satisfy customers or visitors (Sobarna, Citation2021). VR is a powerful marketing tool for hospitality and tourism since it provides potential consumers with vivid pictures of hospitality and tourist destinations and an immersive experience (Huang et al., Citation2016). Customers have limited access to evaluate their potential travel experience before visiting the destination, thus VR plays an important role in the hospitality and tourist market.

Prior research found that tourist satisfaction has positively influenced that destination (Deb & Lomo-David, Citation2021; Rahimizhian et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, tourists who are satisfied with a destination expect to respond and promote positive word of mouth on the destination (Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, previous studies imply that tourist behavior and intention to revisit the destination are positively affected by satisfaction of visiting (Hudson et al., Citation2019; Moon & Han, Citation2018; Torabi et al., Citation2022). Kokkhangplu et al. (2023) customer satisfaction had the most critical effect on consumers’ behavioral intentions. Virtual reality experience affects a customer’s positive responses. For example, the customer received enriched experiences (Yim et al., Citation2017), favorable attitude (Chang et al., Citation2015), satisfaction (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jung et al., Citation2015) and behavioral intentions (Huang et al., Citation2013). Customers have practically been transported to their destination by the engaging and vivid features of VR experiences (Spielmann & Mantonakis, Citation2018). Customers can improve their intentions to visit the destination by immersing themselves in a virtual environment. Thus, it is predicted that when the young have used VR applications, they increase their strong visit intentions to the destination (Hudson et al., Citation2019). Based on the previous studies, therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H4: VR Satisfaction has a positive effect on behavioral intention using virtual reality to visit the destination.

VR and destinations visit intention

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged and increased in tourism fields (e.g. virtual tours). VR-related to technologies in tourism, particularly in tourism destinations (Sobarna, Citation2021). Many studies have been paid to examine and investigate VR (e.g. Chung et al., Citation2015; Disztinger et al., Citation2017).

Previous studies revealed that VR affects behavioral intention in changed tourism destinations (Huang et al., Citation2013; Citation2016; Jung et al., Citation2016, Pantano & Corvello, Citation2014). Many studies implemented the marketing perspective and experiential in tourism destinations to evaluate essential and critical factors of VR concerning destination marketing and motivation that affect behavior intentions (Chen & Lin, Citation2012; Huang et al., Citation2012; Williams, Citation2006). Previous studies have established an underpinning for the relationship between tourist satisfaction and behavioral intentions after using VR tours (Atzeni et al., Citation2022; Loureiro, Citation2020; Manchanda & Deb, Citation2022; Sobarna, Citation2021). People who utilize the VR application can experience the world of virtual reality through their senses toward tourist satisfaction and behavioral intentions (Caissie et al., Citation2021; Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Rahimizhian et al., Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, this study revealed the positive impact of three components of Theory of plan behavior (e.g. subjective norm, attitude, and perceived behavior control and related satisfaction) (Ajzen, Citation1991; Sadiq et al., Citation2022; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2021), satisfaction (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Rahimizhian et al., Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022); and behavioral intentions toward tourism destinations following use of VR application (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022) with the new generation behaviors and satisfaction as the main component for increasing behavioral intention using VR tourism and its enhanced the effectiveness of VR tours promotion and destination marketing in a tourism setting. The proposed conceptual model can be seen in the following .

Methodology

Measurement

The proposed conceptual model examines subjective norms, attitudes, perceived behavior control, VR satisfaction, and behavior intention. Also, providing the mediator as VR satisfaction would influence behavior intention. The proposed conceptual model is verified through theoretical and empirical evidence on this model. Regarding the literature review, the research instrument employed in this study was developed and previously tested by the authors (see ), several items were used for the survey.

Table 1. Reliability and validity of the constructs.

However, these studies were tested and refined based on previous studies: subjective norm, attitude, perceived behavior control (Ajzen, Citation1991; Sadiq et al., Citation2022; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2021), VR satisfaction (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Rahimizhian et al., Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022), and behavior intention to visit destinations (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020; Torabi et al., Citation2022) to investigate the relationships among factors affecting behavior intention to visit destinations. The scale range for this study has been simplified and adjusted as Likert scale from 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and total inter-item correlation were used to test for the reliability of scales. All scales, except the sub-set of value scales, had a Cronbach’s alpha of more than 0.787. A confirmatory factor analysis was then run to confirm the data for testing.

The screening questions asked for basic identifying and demographic details such as sex, age, education, experience using VR tours, time spent using VR tours, and destinations for clarification about the frequency of VR tourism visits. Furthermore, the qualifying questions contained a required field for participants who have previously used a VR tour. Participants acknowledged previous use of VR tourism applications and were provided with the opportunity to participate in the questionnaire. The researcher assured participants that their individual personal data would be protected and secured and received their signed informed consent to participate in the research. Participants who responded to the questionnaire received a gift, valid for up to a month and based on the conditions and criteria. The evaluation questions, VR description, and questionnaire were all in Thai. The questionnaire was sent to be translated by a professional native in English. Prior to implementation, researchers invited five experts to confirm the content validity of the survey questions. In response to expert feedback, the questionnaire was modified and refined to reflect their recommendations. However, the wording and questions in the questionnaire were slightly modified: For instance, ‘How many times do you experience traveling by VR application?’ was changed simply to ‘Experience traveling by VR application’ and ‘I intend to travel frequently to destinations in the near future after using VR applications’ was modified simply into ‘I intend traveling to destinations soon after using VR applications’. Thereafter, researchers conducted a pilot test with 30 young people who were using VR applications for tourism. Finally, this study performed a pre-test with 50 young people who had used a VR application for tourism. This process led to the last revision of items in the questionnaire for VR satisfaction and behavioral intention to visit destinations.

Data collection

A convenient sampling method was applied to collect data from students at university in Thailand. The sample for this study has been defined as people who used VR applications for tourism in the new generation group familiar with technology, particularly students in universities. 60% of the new generation are interested in VR in the future as it becomes more widespread, 80% want to work with cutting-edge technology and 54% appreciate the new and innovative ways into their life (Li, Citation2023). Therefore, the samples are between eighteen to twenty six years old, representing the new generation. The researcher approached ten university lecturers to serve as moderators for the questionnaire designed to capture young people’s perceptions of VR application tourism. Researchers described the purpose of the study (El-Manstrly et al., Citation2020; Karagöz et al., Citation2021). The researcher obtained approval from eight of the Northern, Northeastern, Central, and Southern regions, 2 areas each, representing areas throughout Thailand. To avoid bias in the data collection, the questionnaire was distributed in an online Google Form to the group of students from universities in Thailand to respond to the questionnaire. The characteristics of Thai students are high readiness because they grow up with technology, such as their interest in technology, travel behavior, and cultural context. They are familiar and engaged with technology and perceive experiences through virtual reality. The data was collected for approximately one month in November 2021. The questionnaires were received a total of 450 responses to participate in the study. Of those, 20 responses were incomplete questionnaires. The researcher then performed a validation check. As a result, 430 responses were found to be usable for further analysis, with a response rate of 95.55 percent, making this study’s sample complete. The data was collected, summarized, and analyzed quantitatively using descriptive statistics. shows the respondents’ profiles.

Table 2. Respondent profile (n = 430). The construct means and (STD).

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted to identify the characteristics of the respondents’ socio-demographic profile. For the measurement and the structural model analyses, this study conducted a multivariate statistical procedure such as confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to check how accurately the measured factors represented the latent variables. The measurement model validity was conducted to see how the model fits the collected data and measured by using the suitability of fit statistics criteria. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test the data as multivariate measurement items were used to analyze structural relationships. Regarded as a variance-based approach to SEM (Hair et al., Citation2014), it is more suitable for predictive studies and theory building (Gefen et al., Citation2000). Moreover, this approach mainly focuses on sophisticated models in order to predict key target constructs or to perform theory testing (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Result

Descriptive analysis

shows the respondent profile. There were 302 respondents (70.2%) represented female and 128 respondents (29.8%) who were male. The majority of the respondent’s ages were 19–20 years old (88.6%) and 21–22 (8.8%) which is the new generation to use VR applications. Most of the respondents (85.3%) were bachelor’s degree students studying in the university. Most respondents who experienced VR tours (83.7%) had 1 to 3 times. Respondents spent time with VR by 1 to 2 hours (45.3%) and less than 1 hour (38.4%). There were 247 respondents (57.4%) represented in the domestic destination.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

A CFA was conducted to explore the internal consistency of the construct and its reliability (Byrneb, Citation2010). By using the SPSS-AMOS 22 version, five factors are supported for further measurement. Additionally, each measured variable summarizes factor loadings (i.e. unstandardized estimate, standardized estimate, standard error, p-values, average variance extracted (AVE), construct reliability (CR), and goodness of fit indices. As shown in , the standardized factor loadings of each factor in the measurement model were greater than 0.688. The CFA model fit indices suggested that the minimum value of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient reliability should be 0.70 or greater (Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011). The reliability test was satisfied as the reliability varied from 0.787 (ATT) to 0.839 (PBC). The results of construct composite reliability (CR) are greater than 0.6 and the average variance extracted (AVE) is more than 0.6 for all constructs satisfying the required level ().

Table 3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) new generation behavior on VR satisfaction and intention.

The relation between latent variables (SN, ATT, PBC, SAT, and BIVD) includes the 22 observed variables. It is shown that all variables have a positive factor loading coefficient and are statistically significant (p < 0.01). All 22 observed variables had factor loading coefficient values of between 0.688 and 0.9890 which are those variables’ values greater than the minimum value of 0.60 required for statistical significance. The data indicated that all variables represented components of (SN, ATT, PBC, SAT, and BIVD). As a result, 14 observed variables represented components of the factors affecting VR satisfaction as a mediator of behavior intention. Every detail is given as follows (). Behavior factors affecting VR satisfaction and behavioral intention using VR application tour indicated that the results of CFA were excellent (chi-square (χ2) = 198.206, degree of freedom = 142, P-value = 0.001, proportion between chi-square and degree of freedom (χ2/df) = 1.396, AGFI = 0.929, GFI = 0.960, CFI = 0.993, NFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.988 () (Bollen, Citation1989; Hooper et al., Citation2008; Jöreskog & Sörbom, Citation1989; Kline, Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2009).

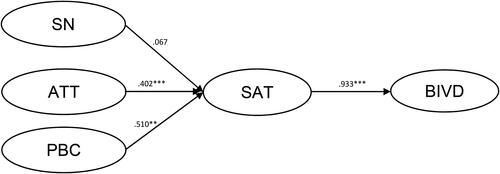

Model testing and results

The structural model fit with χ2 = 217.557, degrees of freedom (df) = 159, χ2/df = 1.368, P-value = 0.001, NFI = 0.973, RMSEA = 0.029, RMR= 0.018, TLI = 0.989, CFI = 0.992, GFI = 0.958, AGFI = 0.932 indicating strong predictive validity. The standardized direct effect, standardized indirect effect, and total standardized effect for all relationships in the structural model are reported in . The path estimates were calculated as shown in (), with the results of the analysis supporting three of the four hypotheses. This study examined the behavior factors affecting VR satisfaction as a mediator, namely, H1, H2, H3, and VR satisfaction on behavioral intention using VR application for tourism (H4). The results found the behavior factors as attitude on VR satisfaction (H2), perceived behavior control on VR satisfaction (H3), and VR satisfaction on behavioral intention using VR application for tourism (H4) were supported with significance at p < 0.01. Although the subjective norm on VR satisfaction (H1) was not supported in the model structure. However, the attitude on VR satisfaction (H2) suggested that VR satisfaction is predicted by attitude (β = 40.2). perceived behavior control on VR satisfaction (H3) proposed that VR satisfaction is predicted by the perceived behavior control (β = 51). Regarding VR satisfaction on behavioral intention using VR application for tourism (H4) it is proposed that behavioral intention using VR application for tourism is predicted by VR satisfaction (β = 93.3). It can be shown in .

Figure 2. The result of the SEM. Model fit statistics; χ2 = 217.557, df = 159, P = 0.001, χ2/df = 1.368, RMSEA = 0.029, RMR = 0.018 GFI = 0.958, AGFI = 0.932, CFI = .992, NFI=.973, TLI= 0.989. Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Table 4. Total, direct, and indirect effects.

Table 5. Path estimates.

Discussion

The VR application has greatly assisted the new generation in gaining experience prior to visiting hospitality and tourism destination sites. This technology can support the destinations’ ability to organize as a new tool to motivate and retain visitors. Moreover, the VR application has an important effect on the new generation’s behavior toward intentions of visiting destinations. Therefore, this study focused on investigating the new generation’s behavior through VR experiences with VR applications and their influence on visit intentions. In particular, our purpose was to investigate the behavior of new generations’ VR experiences and VR satisfaction that had a positive impact on behavioral intentions toward tourism destinations. Based on the study results and subsequent discussion, several conclusions are offered, and theoretical and practical implications are provided below.

The result of this study revealed that the new generation’s behavior has a positive and significant affect on VR satisfaction and behavioral intentions when visiting destinations. In particular, the result indicates that attitude and perceived behavior control had a positive on VR satisfaction. As seen, the behavior of the new generation has been affected by virtual reality. It was motivating and attractive to the new generation to visit, recommend, and find out more information concerning destinations. Additionally, the new generation can be familiar with the experience through VR applications such as the virtual environment, encouraging them to travel to the destination by actual visit. The result of this study, in line with previous studies, sheds light on the significance of the visual aspect of VR experiences and its influence on destination visit intention (Chung et al., Citation2015; Guttentag, Citation2010; Tussyadiah, Citation2016). This result provides an understanding of the relationship between the new generation’s behavior factors and VR satisfaction with behavioral intentions to visit the destinations.

Attitude and perceived behavior control have a positive effect on VR satisfaction with destination visit intentions. The result of this study is consistent with Torabi et al. (Citation2022) highlighted that tourists’ perceived behavior control has a positive affect on their intention toward exploitative use. Also, tourists’ attitudes significantly positively influence intention toward the exploitative use of technology. In contrast with the results of this study, subjective norm has no significant impact on VR satisfaction. Interestingly, the results concern the VR satisfaction influencing the new generation’s behavioral intention to visit the destination on the actual site. In line with our results and with the previous results, studies by Torabi et al. (Citation2022) found that tourist behavior has a significant, positive effect on their satisfaction and revisit intention in destinations. Consistent with the current study, Rahimizhian et al. (Citation2020) reported that the most important result was that destination video has shown technology to effectively generate positive outcomes such as visit and WOM intentions through behavioral involvement with the tourist destination. It could also provide supporting information for the targeting of destination representation through media to particular tourist segments as travel motivation. It should also be noted that new target segments, such as younger users and new generations, are more open to new technologies. They will be led to more positive perceptions and behavior toward delivering promotional content and tourist destinations.

Theoretical implications

The result of this study provides specific theoretical implications. According to the theoretical perspective, the empirical results revealed that the potential of VR experiences had an influence on new generation’s behavior, particularly VR satisfaction and behavioral intention to visit the actual destination afterward using VR applications for tourism. Marasco et al. (Citation2018) reported that the VR experience has an influence on behavior intentions through experiential marketing. Moreover, in VR applications for tourism, it was found that new generation VR technologies had a significant positive affect on the emotions and perspectives aspect of the virtual experience of a tourism destination, thus affecting VR application users’ visit intentions. In this study, the impact of subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavior control was investigated in relation to VR satisfaction both domestically and internationally on actual destinations. Additionally, the results of the current study offer significant evidence of VR satisfaction with behavioral intention toward tourism destinations as a positive influencer of the new generation users’ intention to visit real destinations, including the behavioral involvement in the virtual experience (Chung et al., Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2013; Marasco et al., Citation2018; Torabi et al., Citation2022). Previous research has shown that investigating VR experiences with real tourism destinations provides an understanding of the conceptual VR experience in determining a visitation attitude (Marasco et al., Citation2018; Tussyadiah et al., Citation2018).

However, this study found that there are two significant factors, such as attitude and perceived behavioral control, related to VR satisfaction as a prediction and a mediating factor in the construct of behavioral intention to visit destinations. To address the gaps in research, the proposed model was developed from empirical data. This study highlights the significance of the new generation’s behavioral factors, in particular, subjective norm, attitude, and perceived behavior control, on VR satisfaction as one of the critical factors which had a positive and mediating effect on behavioral intentions to visit destinations. VR satisfaction is the most important factor affecting new new-generation behavior intentions. In addition, this study was extended to the field of tourism research to integrate with technology in order to examine confirmatory factor analysis and also investigate SEM measurement of new generation behavior. Future research will focus on new generation behavior to explore and investigate other aspects, and it will be extended to create a new model related to the behavior factor, VR satisfaction, and behavior intention toward the actual destination model. As a result, the findings of this study will be useful in future research on new-generation behavior. Therefore, the present study provides a theoretical contribution by integrating the previous studies’ findings on new generations’ behavior, VR satisfaction, and behavioral intention to visit actual destinations.

Practical implications

This study investigates the new generation’s behavioral factors to encourage VR satisfaction and the behavioral intention toward hospitality and tourism destinations. Therefore, the current study has tried to respond to the research question: how do the subjective norm, attitude, and perceived behavioral control affect VR satisfaction? Also, How does VR satisfaction influence behavioral intention to visit the actual destinations afterward using the VR application and other devices toward destinations? The results highlighted that attitude and perceived behavior control are significantly positive for VR satisfaction. In this regard, both domestically and internationally, destinations focus on the new generation’s subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control toward tourism technology. Destination managers can enhance the tourism experience, VR satisfaction, and behavioral intention. Based on the results of new generation behavior, destination marketing organizations should provide VR applications and other devices to access destinations appropriately for the new younger generation. However, since new generations use other technologies to access new destinations, other activities, and hospitality sites, it is essential to provide modern and innovative technologies to support the new generation’s different stages of the journey.

This study aims to investigate the new generation of behavior using VR applications to influence VR satisfaction and behavioral intention to visit a destination. Consistent with Koo et al. (Citation2015), subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavior control of tourists using VR in tourism are reported. The current study’s findings are consistent with previous research that found tourist attitudes to be a significant positive predictor of tourist behavioral intention (Ayeh et al., Citation2013; Han, Citation2015; Lam & Hsu, Citation2004; Citation2006). The study finding also aligns with Torabi et al. (Citation2022) indicated that attitude and perceived behavior control factors positively influence satisfaction and revisit intention. Therefore, attitude and perceived behavior control can directly affect VR satisfaction and indirectly influence the new generation’s behavioral intention to visit a destination. However, the results are consistent with previous studies illustrating that VR applications can offer the opportunity for tourists to perceive VR satisfaction and behavioral intention (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Jeong & Shin, Citation2020). The present study provides significant practical implications and valuable insights concerning VR applications that can enhance the behavior of the new generation to receive VR experiences and affect the new generation’s behavior on VR satisfaction with and behavioral intention toward visiting actual destinations. The findings of this study highlight the prospective implementation of VR technology for choosing a tourist destination in the post-COVID-19 era based on factors such as behavior, satisfaction, and positive experiences in VR tourism. Instead of viewing a screen displaying potential tourist destinations or routes, tourists are immersed in virtual environments, facilitating communication, interaction, and exploration to determine the desirability of purchasing an actual trip. In addition, practitioners in tourism destination marketing should prioritize understanding and influencing tourist behavior, satisfaction, and overall experience to elicit affective responses, increase satisfaction, raise attachment to VR, and stimulate intentions to visit the attractions featured in VR tourism. Tourism businesses can promote and market their VR products as knowledgeable, functional, and beneficial activities over various online and other platforms, mobile social media platforms, and websites. Furthermore, this study underlines the importance of incorporating hedonic elements into VR content, suggesting that destination marketers should provide several sensory components such as audio, haptics, video, and artificial intelligence to engage potential tourists in VR destinations emotionally. Content creators in the VR tourism industry are advised to prioritize the needs and behavior of users, particularly authentic experiences within VR tourism. Therefore, developers can enhance emotional factors, such as emotion, enjoyment, involvement, and the flow state, through VR tourism in the future.

The findings provide academic implications. Educators can be extended to study the important behavioral factors affecting the new generation in the future. Some factors could be investigated in-depth, namely, subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavior control aspects. Furthermore, the study should be thoroughly investigated using the qualitative method to integrate the findings and support the quantitative findings in order to identify significant factors influencing VR satisfaction and behavioral intention. Also, the results should be compared with the results by using different sampling to compare the difference in empirical evidence. However, we believe that the findings of this research will be useful for educators and studies concerning the new generation’s behavior, affecting VR satisfaction and behavioral intention to visit destinations. Moreover, the results could be beneficial in terms of tourism planning and development in the future.

Limitations and future study

This research offers many implications for all sectors that are concerned with destinations, particularly destination marketing organizations, to provide destinations and faculties for new generations traveling to the destination; the following limitations need careful reflection in future studies. First, this study sample was limited to data collected at COVID-19 using a Google form. Future research should be conducted in person to ensure that respondents respond without bias. Second, the sample size was limited only to the new generation in Thailand. Future studies should include a more diverse sample size in other generations and countries in future studies, as the sample population of the current study was to generalize only new generations in Thailand. Third, future studies should address more diverse issues from the sample size, such as experience through VR applications, motivation to use the VR application, and developing VR applications for all, etc. This approach will provide better suggestions on DMOs and tourism destinations that yield better policy recommendations for the public and private sectors. Finally, this study thoroughly concentrates on behavioral factors and satisfaction with behavioral intention using VR applications for tourism. Thus, future studies should focus on other details of those factors for more information concerning behavioral intentions to visit the destination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Akkhaporn Kokkhangplu

Akkhaporn Kokkhangplu is currently a lecturer at the Hospitality and Event Management, Khon Kaen Business School, Khon Kaen University, Thailand. He obtained his Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Tourism Management, National Institute of Development Administration in 2021. His research interests are tourism and hospitality development, policy, and planning. Recently, he has focused on the tourism and hospitality industry and health and wellness business.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Pratkanis, A. R. (1989). Attitude structure and function. LEA, 1–15.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Atzeni, M., Del Chiappa, G., & Mei Pung, J. (2022). Enhancing visit intention in heritage tourism: The role of object‐based and existential authenticity in non‐immersive virtual reality heritage experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(2), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2497

- Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., & Law, R. (2013). Predicting the intention to use consumer-generated media for travel planning. Tourism Management, 35, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.010

- Bec, A., Moyle, B., Schaffer, V., & Timms, K. (2021). Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tourism Management, 83, 104256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104256

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley & Sons.

- Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2014). Smart tourism destinations. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014 (pp. 553–564). Cham: Springer.

- Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2015). Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through the personalization of services. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015 (pp. 377–389). Springer.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807644

- Caissie, A. F., Riquier, L., De Revel, G., & Tempere, S. (2021). Representational and sensory cues as drivers of individual differences in expert quality assessment of red wines. Food Quality and Preference, 87, 104032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104032

- Chang, I.-C., Liu, C.-C., & Chen, K. (2014). The effects of hedonic/utilitarian expectations and social influence on continuance intention to play online games. Internet Research, 24(1), 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-02-2012-0025

- Chang, Y. C., Tsai, C. L., & Chiu, W. Y. (2015). The influence of life satisfaction and well-being on attitude toward the internet, motivation for internet usage and internet usage behavior. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics, 18(6), 927–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720502.2015.1108111

- Chen, H., & Rahman, I. (2018). Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.006

- Chen, H. T., & Lin, T. W. (2012). How a 3D Tour Itinerary Promotion Affect Consumers’ Intention to Purchase a Tour Product? Information Technology Journal, 11(10), 1357–1368. https://doi.org/10.3923/itj.2012.1357.1368

- Chung, N., Han, H., & Joun, Y. (2015). Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.068

- Combi, C. (2015). Generation Z: Their Voices, Their Lives. Windmill Books.

- Conner, M. (2020). Theory of planned behavior in Handbook of Sport Psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Deb, M., & Lomo-David, E. (2021). Determinants of word of mouth intention for a World Heritage Site: The case of the Sun Temple in India. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100533

- Disztinger, P., Schlögl, S., & Groth, A. (2017). Technology acceptance of virtual reality for travel planning. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2017 (pp. 255–268). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51168-9_19

- Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008

- El-Manstrly, D., Ali, F., & Steedman, C. (2020). Virtual travel community members’ stickiness behaviour: How and when it develops. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102535

- Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M. C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407

- Guttentag, D. A. (2010). Virtual reality: Applications and implications for tourism. Tourism Management, 31(5), 637–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.003

- Hagger, M. S., Cheung, M. W. L., Ajzen, I., & Hamilton, K. (2022). Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 41(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001153

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hamid, S., & Bano, N. (2021). Behavioral Intention of Traveling in the period of COVID-19: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Perceived Risk. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(2), 357–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-09-2020-0183

- Han, H. (2015). Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management, 47, 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.014

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Evaluating model fit: a synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature [Paper presentation]. 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies (pp. 195–200).

- Hrubes, D., Ajzen, I., & Daigle, J. (2001). Predicting hunting intentions and behavior: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Leisure Sciences, 23(3), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/014904001316896855

- Huang, Y. C., Backman, S. J., & Backman, K. F. (2012). Exploring the impacts of involvement and flow experiences in Second Life on people’s travel intentions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 3(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/17579881211206507

- Huang, Y. C., Backman, K. F., Backman, S. J., & Chang, L. L. (2016). Exploring the implications of virtual reality technology in tourism marketing: An integrated research framework. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2038

- Huang, Y. C., Backman, S. J., Backman, K. F., & Moore, D. (2013). Exploring user acceptance of 3D virtual worlds in travel and tourism marketing. Tourism Management, 36, 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.009

- Hudson, S., Matson-Barkat, S., Pallamin, N., & Jegou, G. (2019). With or without you? Interaction and immersion in a virtual reality experience. Journal of Business Research, 100, 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.062

- Jeong, M., & Shin, H. H. (2020). Tourists’ experiences with smart tourism technology at smart destinations and their behavior intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1464–1477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519883034

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1989). LISREL 7: A guide to the program and applications. Spss.

- Jung, T., Chung, N., & Leue, M. C. (2015). The determinants of recommendations to use augmented reality technologies: The case of a Korean theme park. Tourism Management, 49, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.013

- Jung, T., Dieck, M., Lee, H., & Chung, N. (2016). Effects of virtual reality and augmented reality on visitor experiences in museum. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2016 (pp. 621–635). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28231-2_45

- Jung, T., Tom Dieck, M. C., Moorhouse, N., & Tom Dieck, D. (2017 Tourists’ experience of Virtual Reality applications [Paper presentation]. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), (pp. 208–210). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCE.2017.7889287

- Kanimozhi, S., & Selvarani, A. (2019). Application of the decomposed theory of planned behaviour in technology adoption: A review. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, 6(2), 735–739.

- Karagöz, D., Işık, C., Dogru, T., & Zhang, L. (2021). Solo female travel risks, anxiety and travel intentions: Examining the moderating role of online psychological-social support. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(11), 1595–1612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1816929

- Kim, M., & Qu, H. (2014). Travelers’ behavioral intention toward hotel self-service kiosks usage. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2012-0165

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Koo, C., Chung, N., & Kim, H. W. (2015). Examining explorative and exploitative uses of smartphones: a user competence perspective. Information Technology & People, 28(1), 133–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-04-2013-0063

- Koulopoulos, T., & Keldsen, D. (2016). The Gen Z Effect: The Six Forces Shaping the Future of Business. Routledge.

- Kwok, A. O., & Koh, S. G. (2021). COVID-19 and extended reality (XR). Current Issues in Tourism, 24(14), 1935–1940. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798896

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. (2004). Theory of planned behavior: Potential travelers from China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 28(4), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348004267515

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Management, 27(4), 589–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.02.003

- Li, D. (2023). The Future of Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR) with Gen Z. https://medium.com/@derekli1700/the-future-of-virtual-and-augmented-reality-vr-ar-with-gen-z-6714c21a39ea

- Lin, H. F. (2007). Predicting consumer intentions to shop online: An empirical test of competing theories. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 6(4), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2007.02.002

- Li, Y., Song, H., & Guo, R. (2021). A study on the causal process of virtual reality tourism and its attributes in terms of their effects on subjective well-being during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031019

- Loureiro, S. M. C. (2020). Virtual reality, augmented reality and tourism experience. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing (pp. 439–452). Routledge.

- Manchanda, M., & Deb, M. (2022). Effects of multisensory virtual reality on virtual and physical tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(11), 1748–1766. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1978953

- Mäntymäki, M., Merikivi, J., Verhagen, T., Feldberg, F., & Rajala, R. (2014). Does a contextualized theory of planned behavior explain why teenagers stay in virtual worlds? International Journal of Information Management, 34(5), 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.05.003

- Marasco, A., Buonincontri, P., van Niekerk, M., Orlowski, M., & Okumus, F. (2018). Exploring the role of next-generation virtual technologies in destination marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.12.002

- Michael, T. (2011). Deconstructing Digital Natives: Young People, Technology, and the New Literacies. Routledge.

- Moon, H., & Han, H. (2018). Destination attributes influencing Chinese travelers’ perceptions of experience quality and intentions for island tourism: A case of Jeju Island. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.08.002

- Nasri, W., & Charfeddine, L. (2012). Factors affecting the adoption of Internet banking in Tunisia: An integration theory of acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 23(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2012.03.001

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2012). Conceptualising technology enhanced destination experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.08.001

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2015). Smart technologies for personalized experiences: a case study in the hospitality domain. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0182-1

- Pandit, V. (2015). We are Generation Z: How Identity, Attitudes, and Perspectives are Shaping our Future., Brown Books Publishing Group.

- Pantano, E., & Corvello, V. (2014). Tourists’ acceptance of advanced technology-based innovations for promoting arts and culture. International Journal of Technology Management, 64(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2014.059232

- Rahimizhian, S., Ozturen, A., & Ilkan, M. (2020). Emerging realm of 360-degree technology to promote tourism destination. Technology in Society, 63, 101411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101411

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Md Noor, S., Schuberth, F., & Jaafar, M. (2019). Investigating the effects of tourist engagement on satisfaction and loyalty. The Service Industries Journal, 39(7-8), 559–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1570152

- Sobarna, A. (2021). Pengaruh Wisata Virtual Reality (VR) terhadap niat berperilaku wisatawan. In Prosiding Industrial Research Workshop and National Seminar, 12, 1336–1344. September)(

- Sadiq, M., Dogra, N., Adil, M., & Bharti, K. (2022). Predicting online travel purchase behavior: The role of trust and perceived risk. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 23(3), 796–822. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2021.1913693

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S. M., Cabeza-Ramírez, L. J., Muñoz-Fernández, G., & Fuentes-García, F. J. (2021). Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 970–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1829571

- Schiopu, A. F., Hornoiu, R. I., Padurean, A. M., & Nica, A. M. (2022). Constrained and virtually traveling? Exploring the effect of travel constraints on intention to use virtual reality in tourism. Technology in Society, 71, 102091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102091

- Spielmann, N., & Mantonakis, A. (2018). In virtuo: How user-driven interactivity in virtual tours leads to attitude change. Journal of Business Research, 88, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.037

- Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (2008). Millennials & K-12 Schools. Great Falls.

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 144–176. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.144

- Torabi, Z. A., Shalbafian, A. A., Allam, Z., Ghaderi, Z., Murgante, B., & Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R. (2022). Enhancing Memorable Experiences, Tourist Satisfaction, and Revisit Intention through Smart Tourism Technologies. Sustainability, 14(5), 2721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052721

- Tussyadiah, I. (2014). Expectation of travel experiences with wearable computing devices. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014. Springer.

- Tussyadiah, I. P. (2016). Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55, 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.03.005

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Wang, D., Jung, T. H., & Tom Dieck, M. C. (2018). Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tourism Management, 66, 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.003

- Urry, J., & Sheller, M. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning, 38(2), 207–226.

- Urry, J., & Sheller, M. (2012). Mobile Technologies of the City. Routledge.

- Wang, D., Li, X. R., & Li, Y. (2013). China’s “smart tourism destination” initiative: A taste of the service-dominant logic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 59–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.05.004

- Wen, H., & Leung, X. Y. (2021). Virtual wine tours and wine tasting: The influence of offline and online embodiment integration on wine purchase decisions. Tourism Management, 83, 104250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104250

- Williams, A. (2006). Tourism and hospitality marketing: fantasy, feeling and fun. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18(6), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110610681520

- Wu, W., West, S. G., & Taylor, A. B. (2009). Evaluating model fit for growth curve models: Integration of fit indices from SEM and MLM frameworks. Psychological Methods, 14(3), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015858

- Yim, M. Y. C., Chu, S. C., & Sauer, P. L. (2017). Is augmented reality technology an effective tool for e-commerce? An interactivity and vividness perspective. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 39(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2017.04.001

- Zeng, Y., Liu, L., & Xu, R. (2022). The effects of a virtual reality tourism experience on tourist’s cultural dissemination behavior. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 314–329. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010021