Abstract

The main purpose of the research is to analyze the effect that digital transformation has on technological and non-technological innovation as key factors that increase financial performance in SMEs. The study focuses on a sample of 4121 SMEs from the services, trade and manufacturing sectors, located in Mexico. The data was collected through an online questionnaire addressed to the SMEs manager through the LimeSurvey platform. The field work will be carried out from January to July 2022. The PLS-SEM statistical technique was used to test the hypotheses of the proposed theoretical model. The data show that digital transformation plays an important role in a more decisive way in technological innovation and non-technological innovation; In addition, it is also proven that innovation in its two modalities has significant effects on the financial performance results of Mexican SMEs. However, we have found that digital transformation has a small effect on the financial performance of these companies. On the other hand, the study shows that the sustainability strategy plays the role of a moderating variable, positively affecting technological innovation and non-technological innovation. Furthermore, the study explains that the male gender is the one that has had the best results in innovation and financial performance. The study contributes to the development of the theory of dynamic capabilities supported by the innovation model (DUI and STI).

REVIEWING EDITOR:

SUBJECTS:

1. Introduction

In the changing business landscape of the 21st century, characterized by rapid technological evolution and growing global interconnection, small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) face a double strategic challenge: adapting to digital transformation and embracing innovation as an essential driver. to raise your performance or fall behind in an increasingly competitive business environment (Costa-Climent et al., Citation2023; Hart & Milstein, Citation2003). However, at a global level, SMEs are the companies that generate the most employment, which contribute greater income to the gross domestic product and energize the economy as a whole (Juergensen et al., Citation2020; OECD, Citation2022). Therefore, organizations are immersed in a dynamic environment that requires agility, flexibility and a constant ability to evolve (Cha, Citation2020); and adapt to new times with new innovative and digital business models (Teece, Citation2018). Digitalisation entails the application of digital technologies to a wide range of existing tasks and enables new tasks to be performed. Digitalisation has the potential to transform business processes, the economy and society in general (OECD, Citation2018).

Effective adoption of digital transformation and integration of innovative practices play a critical role in improving the competitive position and financial performance of organizations (Grooss, Citation2024). Adding innovation and financial performance not only as emerging trends, but as unavoidable strategies for sustainable growth, competitiveness and catalysts to raise the prosperity of SMEs (Zhou & Liao, Citation2024).

In the age of information and global interrelation, digital transformation has ceased to be an option and has become a strategic necessity for SMEs (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). This process covers the integration of advanced technologies in all aspects of business operation, from internal management to interaction with customers and participation in digital value chains (Scuotto et al., Citation2023). The adoption of efficient management systems, process automation, data analytics and online presence are essential elements of this transformation, allowing SMEs to optimize their operations and improve their decision-making capacity (N. Chen et al., Citation2022; Teece, Citation2009, Citation2014).

Likewise, digital transformation goes beyond the simple adoption of technologies; represents a fundamental change in the way SMEs operate and relate to their environment (Dąbrowska et al., Citation2022). From the implementation of e-commerce platforms to the automation of internal processes, digital transformation redefines the very structure of companies, allowing them to be more agile, efficient and customer-oriented (Hemerling et al., Citation2018).

At the same time, innovation is the creative fuel that drives digital transformation in its various forms, becoming the creative engine that drives it, generating unique solutions and opening new market opportunities (Radicic & Petković, Citation2023). Instead of being conceived exclusively for the introduction of novel products to the market, innovation in the contemporary business context extends to the creation of new business models, efficient operating processes and the generation of added value for customers (Costa et al., Citation2023). The ability to adapt to a changing environment, identify opportunities and develop unique solutions are key aspects of an innovative strategy that can make a difference for SMEs (Avelar et al., Citation2024). Despite growing recognition of the importance of digital transformation and innovation, many SMEs face significant challenges on their path to adopting these practices (Telukdarie et al., Citation2023). Some limitations or challenges are: 1. Budgetary (finance), 2. Lack of technical knowledge and; 3. Resistance to change. These have become common barriers that hinder the transformation process and directly impact your financial performance. (Zuzaku & Abazi, Citation2022). These business problems have been analyzed from strategic management from different theoretical and conceptual frameworks (Chesbrough et al., Citation2014; Podmetina et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the use of new technologies in processes for the development of technological and non-technological innovation in organizations is focusing strongly on sustainable and ecological practices (Gherghina et al., Citation2020; Marin et al., Citation2015). Therefore, new business leaders, including SMEs, are adopting a culture focused on eco-innovation, derived from climate change, consumer needs and the route to sustained competitive advantage (Valdez-Juárez & Castillo-Vergara, 2020). With this type of strategies, companies have a significant impact on the social and ecological objectives framed in the sustainable development objectives (SDG-2030) (Pizzi et al., Citation2020).

The theory of dynamic capabilities is revealed as a valuable conceptual framework for understanding how companies, especially SMEs, can develop, integrate and reconfigure their resources and skills in response to a constantly changing business environment (Teece, Citation2007). It highlights the importance of adaptability and the ability to learn from experience to achieve sustainable competitive advantages and is manifested as the ability of an SME to identify digital opportunities, integrate new technologies, and strategically reconfigure its operations to maximize customer value and financial performance (Rueda Sánchez et al., Citation2022). Likewise, there is a great diversity of models that analyze and assess the capacity for business or organizational innovation. One of the most highlighted in the literature is the innovation model developed by Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, Lundvall, et al. (Citation2007), called the Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) and the Doing, Using, Interacting (DUI) model. The STI Model is based on learning processes and investments in Research, Development, Innovation (R + D + I), with the support and collaboration of highly qualified intellectual capital in terms of scientific and technological capabilities, and also with the technological cooperation of science and technology centers, universities, investors in science and technology, etc. The DUI Model is based on the generation and circulation of tacit knowledge, based on innovation in learning processes under the premises of doing, using and interacting. This model can help the development of innovation in SMEs from three approaches. 1. Learning by doing (learning by solving day-to-day problems that arise in organizational and productive activity); 2. Learning by using (learn the use and adaptation of new technical systems); and 3. Learning by interacting, inside the organization and outside it, especially in producer-user (client) relationships (Lundvall, Citation2007).

According to the innovation model proposed by Jensen within the framework of the OECD OSLO manual, it highlights the diversity of forms that innovation can take, going beyond the confines of traditional technological innovation, recognizing the importance of non-technological innovations., including those related to the organization, processes and market strategies (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, & Lundvall, Citation2007). According to the OSLO manual (OECD, Citation2018), innovation activities include all developmental, financial and commercial activities undertaken by a firm that are intended to result in an innovation for the firm. Furthermore, it concludes that a business innovation is a new or improved product or business process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the firm’s previous products or business processes and that has been introduced on the market or brought into use by the firm. For Mexican SMEs, this model offers a valuable perspective by allowing innovation to encompass a broader range of activities, thus facilitating its effective integration into business strategy (OECD, Citation2018).

Despite the theoretical clarity provided by the dynamic capabilities and the technological and non-technological innovation model, its implementation in the field of Mexican SMEs is not without challenges (Hervas-Oliver et al., Citation2021). However, these challenges offer opportunities for SMEs to develop specific dynamic capabilities, such as organizational learning capacity, digital transformation, and the ability for continuous innovation (Chatterjee et al., Citation2023). Previous studies related to the development and growth of SMEs in Mexico, from the technological and innovation context, have shown that it is necessary to continue exploring these business activities in an underground economy but with possibilities for growth. Therefore, the study developed by Valdez-Juárez & Castillo-Vergara, (Citation2021) and Valdez-Juárez et al. (Citation2023), are the background of this investigation. Given that in the Latin American context and particularly in the Mexican context there is a great gap in the literature for the analysis of digital transformation and innovation in SMEs, therefore the relevance and interest of carrying out a detailed analysis of the dynamic capabilities and business strategies of these organizations (Felzensztein et al., Citation2021). Thus, in this new analysis, technological and non-technological innovation is studied from a theoretical perspective using the DUI and STI model. As well as, specific and exclusive metrics are incorporated for the analysis of financial performance.

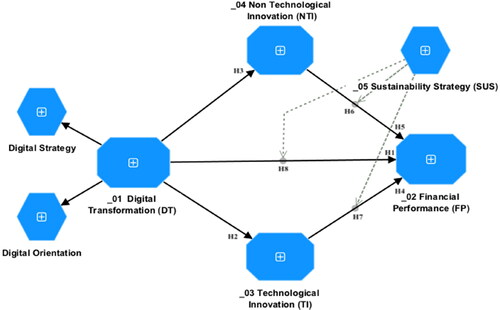

Therefore, the main objective of this research work is to analyze the behavior that digital transformation manifests in innovation (technological and non-technological) and in the financial performance results of Mexican SMEs. Furthermore, the effect of technological and non-technological innovation on the financial performance results of Mexican SMEs is verified. Also, the moderating effect of the sustainability strategy in the relationship between technological and non-technological innovation with the results of the financial performance of Mexican SMEs is analyzed. Finally, another of our objectives is to verify the existence of significant differences between the gender of the managers of Mexican SMEs with respect to digital transformation, technological innovation, non-technological innovation and financial performance.

The research questions are: 1. Does digital transformation influence the technological and non-technological innovation of Mexican SMEs? 2. Does digital transformation influence the financial results of Mexican SMEs? 3. Does technological and non-technological innovation influence the financial results of Mexican SMEs? 4. Does the sustainability strategy influence innovation (technological and non-technological) and the financial performance of Mexican SMEs? 5. Is the gender of the SMEs manager a differentiating element in the digital transformation, innovation and in the results of the financial performance of Mexican SMEs? This research has outstanding relevance taking into account two fundamental aspects: 1. The limited study of digital transformation and innovation in the field of SMEs located in emerging economies; 2. The variables under study are analyzed from the perspective of the theories of dynamic capabilities, under the model of technological and non-technological innovation as complementary elements that determine digital transformation and innovation that increase the competitiveness and financial performance of SMEs. Mexican.

The structure of the research work is made up of the introduction, theoretical-conceptual review and development of hypotheses. In a second section, the methodological section is formulated, composed of the characteristics of the population, the sample, the measurement and the justification of the variables under study. Finally, the results obtained, the discussions and conclusions, as well as future lines of research, are shown.

2. Literature and Hypothesis development

2.1. The digital transformation and its effects on financial performance (SMEs)

In current times, SMEs from different regions are betting on the use of new technologies through innovative strategies that lead them to digital transformation for their growth and financial sustainability (Kumar et al., Citation2023), One of these strategies is sustainable digital transformation through the incorporation of industry 4.0 and the use of emerging technologies for the transformation of business models (Costa Melo et al., Citation2023). Some researchers on the subject have explained that the combination of technology and innovation has a very significant influence on business results, such as product improvement, increased market shares, customer satisfaction and increasing economic profits (Shah et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, in turbulent scenarios, SMEs have had to adapt to these environments using technology as digital platforms in order to make logistics, the supply chain, and the delivery of products and services to customers more efficient. These digital strategies have allowed us to improve sales, operational and financial performance (Rajala & Hautala-Kankaanpää, Citation2022). On the other hand, some other researchers have revealed that the level of technological maturity of the company, including management capabilities, determine the technological capacity and the degree of technological transformation of the SME, and that in turn, these dynamic capabilities are drivers of business operational and financial performance (Battistoni et al., Citation2023; Zahoor et al., Citation2023). In short, SMEs have greater barriers to innovate and adopt new technologies, however during the COVID-19 pandemic, many companies, including smaller ones, adopted new technologies and innovation to improve their processes and products, strategies that they allowed them to survive and in some cases achieve significant financial achievements (Guo et al., Citation2020; Radicic & Petković, Citation2023). The following hypothetical statement is made below:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Digital transformation has a significant influence on the financial results of Mexican SMEs.

2.2. Digital transformation in technological and non-technological innovation (SMEs)

According to Parviainen et al. (Citation2022), digital transformation is presented through changes in ways of working, functions and business offerings caused by the adoption of digital technologies in an organization. The digital transformation realizes the digitization of companies in functional areas such as production, marketing and information, transcending the traditional boundaries of the company with the help of technological innovation (Acemoglu, Citation2003; Zhang et al., Citation2022). According to P. Chen and Kim (Citation2023), digital transformation optimizes the allocation of company resources, and can significantly increase innovation capabilities both quantitatively and qualitatively. Digitalization is radically changing production chains in all sectors and the dynamics between producers, suppliers and end users. (Überbacher et al., Citation2020). The positive effect of digital transformation is that it advances the competence of enterprises in technological innovation and enables them to maintain their core competitiveness, playing a decisive role in achieving business value growth (Ma et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, technological advances have led to changes in the economic value of companies, business innovation and competitive models, and have served as the basis for digital strategies (Dahlman et al., Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Adoption of digital technologies depends on the perceived benefits and/or value of the technologies (Omrani et al., Citation2024). Innovation drivers have a major impact on how digital transformation affects innovation performance (P. Chen & Kim, Citation2023), management capabilities are relevant for transforming innovation into a competitive advantage (Vasconcelos et al., Citation2021). The following hypothetical statement is made below:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Digital transformation has a significant influence on the technological innovation of Mexican SMEs.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Digital transformation has a significant influence on the non-technological innovation of Mexican SMEs.

2.3. Technological and non-technological innovation in financial performance (SMEs)

In the current dynamic and globalized business environment, innovation has become a determining factor for the success of SMEs in different regions with developing and emerging economies (Alcalde-Heras et al., Citation2019; Ramírez-Solis et al., Citation2022). The ability to adapt to technological and non-technological changes not only influences survival, but also the financial performance of entities that can mark their success or stagnation (Radicic & Djalilov, Citation2019). The adoption of advanced technologies has been an essential component for improving the financial performance of SMEs (Lemonakis et al., Citation2018; Macharia Chege et al., Citation2020). The implementation of intelligent systems, such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things and automation, has been a significant catalyst for improving operational efficiency and reducing costs in SMEs (Bagheri et al., Citation2019). The direct connection between the adoption of technologies and financial growth is evident in success stories where investment in innovative systems has allowed companies to streamline processes, improve product quality and respond more quickly to market demands (Thathsarani & Jianguo, Citation2022; Valdez-Juárez & Castillo-Vergara, Citation2021).

Organizations that have embedded technologies as solutions based: 1. In the cloud for business management, 2. Access to data in real time and 3. The flexibility offered by these alternatives, have allowed SMEs to make decisions with greater foundations and in a faster way (Battistoni et al., Citation2023; Naushad & Sulphey, Citation2020). The permanence of SMEs in the market is made up of challenges that consist of a constant evolution of actions related to the dynamic capabilities of companies, highlighting the ability to adapt to changes in the environment, modifying organizational structures, achieving experience for innovation that gives response to obtaining competitive advantages (Teece, Citation2016); This is where digital transformation impacts the performance of organizations, and the processes and performance of SMEs (Garbin Praničević et al., Citation2023).

However, the adoption of technological innovations is not without challenges. SMEs often face financial and training limitations, which can make it difficult to implement advanced technologies (Ajagbe et al., Citation2015). Overcoming barriers becomes crucial, where government intervention and creating supportive policies can play a crucial role (Farjam et al., Citation2023). The dynamics of the business environment require that business models become increasingly agile and that SMEs adopt digital transformation strategies that help strengthen technological and non-technological innovation capabilities (Parrilli et al., Citation2020; Parrilli & Alcalde Heras, Citation2016), offering answers to consumers’ purchasing routine and needs; with the aim of raising financial performance (Ulas, Citation2019).

Innovation has become an important factor for the competitiveness of SMEs where management capabilities, technology and obtaining financial resources are key factors (de Vasconcellos et al., Citation2021; Teece, Citation2018). Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen technological and non-technological innovation capabilities, and information processing where literacy and digital transformation of SMEs are a tool to achieve this (Zahoor et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, in every company, innovations are decisive for strengthening financial performance (Jusufi, Citation2023).

SMEs have to establish strategies for constantly evaluating the behavior of the markets in order to detect opportunities; and thereby implement technological innovations in products-services and processes, as well as the implementation of non-technological marketing and organizational innovations that impact financial indicators (Jamai et al., Citation2021; Thomä, Citation2017). Those who use the services of KIBS (Knowledge-Intensive Business Services) have the opportunity to have current knowledge that drives technological and non-technological innovation that impacts expansion into new markets and the development of new products, giving results in the financial improvement provided competitive advantages (Seclen-Luna et al., Citation2022).

Some studies in the Latin American context have explained that technological innovation and non-technological innovation also play a significant role in the financial performance of SMEs (Naranjo-Valencia et al., Citation2016; Olomu et al., Citation2016). The improvement of internal processes, efficient knowledge management and innovation in business models are essential components of this form of innovation (Lee, Citation2023). On the other hand, SMEs located in emerging economies, which are able to identify and optimize their processes, such as the supply chain, product or service delivery, experience greater operational efficiency (Cuevas-Vargas et al., Citation2023; Silvestre & Ţîrcă, Citation2019). The implementation of knowledge management and leadership practices based on thinking with a view to digital transformation has allowed SMEs to take advantage of internal and external experience, improving decision making and operational and financial efficiency (Gërguri-Rashiti et al., Citation2017; León-Moreno et al., Citation2018). Innovation in business models supported by new technologies, such as differentiated marketing strategies or product diversification, has proven to be crucial for adaptability in changing markets, improving brand positioning, increasing customer satisfaction and since then increase the economic benefits for SMEs (Bouwman et al., Citation2019; Cuevas-Vargas et al., Citation2021). Based on the previous analysis, the following hypotheses are presented:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Technological innovation increases the financial results of Mexican SMEs.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Non-technological innovation increases the financial results of Mexican SMEs.

Currently, SMEs have greater challenges than large companies. One of them is digital transformation, however, this strategy cannot be developed without the support of sustainability practices. This term is understood as a process that has the purpose of seeking balance between the environment and the use of natural resources (UNO, Citation2019). More recently, sustainability, social responsibility, green growth and ecological practices are part of sustainable development (McWilliams et al., Citation2016; Nosratabadi et al., Citation2019). These practices represent the greatest development challenges in trying to meet the needs of the present without putting at risk the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Barney et al., Citation2011; Dahlman et al., Citation2016). The literature states that the sustainability strategy is contemplated within the theory of dynamic capabilities, as a fundamental part of achieving results of superior value in innovation and financial performance (Cheng et al., Citation2023; Teece, Citation2007). Recent studies have revealed that the sustainability strategy in new technologies has been one of the most recurring actions by companies globally. The use of emerging technologies such as open access or cloud computing has allowed them to reduce costs and also impacts on the environment, thereby achieving savings and improving financial balance (Al-Mutawa & Saeed Al Mubarak, Citation2023; Alshaher et al., Citation2023). Sustainable practices have permeated the innovation results of small and large companies, a clear example is the improvements in the production processes of ecological products, lean processes and green supply chains (Kiranantawat & Ahmad, Citation2022). These results are due to the dynamic organizational capabilities that are derived from the management and leadership of the companies’ managers (Taghizadeh et al., Citation2023). But also, these changes have been generated by the new global demands of consumers, by the social, political and economic changes generated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Rumanti et al., Citation2022). Recent studies indicate that the sustainability strategy is a competitive advantage that allows obtaining multiple benefits. Therefore, companies with a proactive attitude towards environmental practices improve their innovation and financial results in a more balanced and sustainable way (Mady et al., Citation2023; Menne et al., Citation2022). The following hypotheses are proposed below:

Hypothesis 6 (H6): The sustainability strategy has a moderating effect that can change the results between non-technological innovation and the financial performance of Mexican SMEs.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): The sustainability strategy has a moderating effect that can change the results between technological innovation and the financial performance of Mexican SMEs.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): The sustainability strategy has a moderating effect that can change the results between the digital transformation and the financial performance of Mexican SMEs. The hypotheses of this research can be seen in (theoretical/operational research model).

3. Methodology

The operational model of the research is analyzed with the Structural Equations Model (SEM), specifically with the statistical technique of analysis of variance through the Partial Least Square (PLS). This multivariate statistical technique works with blocks of variables (components) and estimates the model parameters by maximizing the explained variance of all the dependent variables (both latent and observed) (Chin, Citation1998). The research is quantitative, conclusive and explanatory in order to examine how and why a certain empirical phenomenon occurs (Henseler, Hubona, et al., 2016). The PLS-SEM statistical technique was chosen according to the objective of the research and the nature of the constructs of the operating model of this research. In addition, PLS-SEM has been frequently used for the analysis of individual and group behavior (Sosik & Kahai, Citation2009); It is also used in strategic business management (Hair et al., Citation2019), information systems and in other disciplines related to organizational performance (Benitez et al., Citation2020). This section describes the subjects (Mexican SMEs) that participate in the study (sample), the validation of the constructs and the dimensions that make up the questionnaire used and the method for its validation.

3.1. Sample

The global economic outlook continues to be challenged by persistent inflation and subdued growth prospects. After Covid-19 and the war conflicts, many Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) have been severely affected. According to data issued by the OECD (Citation2023), Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth has been stronger than expected so far in 2023, but is now moderating as the effects of weaker financial conditions are increasingly felt. stricter regulations, weak trade growth and lower business and consumer confidence. Rising geopolitical tensions are also again contributing to uncertainty about the near-term outlook. Global GDP growth is forecast to slow to 2.7% in 2024, from 2.9% this year, before rising to 3% in 2025 as real income growth recovers and official interest rates begin to reduce. Particularly in Mexico, the economy is forecast to expand by 2.5% in 2024 and 2% in 2025, after growing by 3.4% in 2023. Consumption will be supported by a strong labor market. The investment will be supported by public infrastructure projects expected to be completed in 2024 and by the relocation of manufacturing activities to Mexico. The dynamism of exports will be mitigated by more moderate growth in the United States. Inflation will drop to 3.9% in 2024 and 3.2% in 2025. In addition, the phenomenon of nearshoring in Mexico represents an economic opportunity for the country, but which in turn can affect the performance and competitiveness of MSMEs. Just as happened during the Covid-19 pandemic, where most smaller companies suffered a reduction in income, staff reduction, high debt and lag in new technologies (INEGI, Citation2022).

The study is cross-sectional, quantitative and with an explanatory-predictive approach, using the stratified method according to the selection of participating companies according to the sector of activity and organizational size. In Mexico, as in many regions, the backbone of the economy is MSMEs. According to INEGI (Citation2023), the latest registry in this country there is an average of 5527 thousand MSMEs from different economic sectors. According to the data presented by the (INEGI, Citation2022), it shows that the monthly death rate is 1.45% while the birth rate is 0.81%, which means that of every 10,000 establishments existing at a given time, in the period of one month, 145 die and 81 are born (INEGI, Citation2021). The Covid-19 pandemic caused the death of a large number of establishments, although new establishments also emerged, but not in the same proportion. According to INEGI (Citation2023), In these regions of the country there are approximately 1,445,803 MSMEs ranging from 5 to 250 employees. To carry out this research, the sample size was determined so that the maximum margin of error for estimating a proportion was less than 0.02 points with a confidence level of 95.0%. The technique for collecting information was through a personal interview (online questionnaire) directed at the owner and/or manager of the SMEs through the LimeSurvey Professional platform and through the use of email. The sampling used to collect the data is simple random. The field work was carried out during the months of January to July 2022. The total sample analyzed in this study corresponds to 4121 MSMEs (microenterprises are 54.7% of which 47.6% have the expectation of increasing their workforce by 2023, small companies are 25.5%, of which only 27.0% have the expectation of increasing their workforce by 2023 and medium-sized companies are 19.8%, of which only 25.4% have the expectation of increasing their workforce for 2023). These companies belong to the productive sector of services 39.5%, trade 33.3% and manufacturing 27.2%, which are geographically established in the North, Center and South region of Mexico. Other of the most significant characteristics of these companies are the following: 1) the management of these MSMEs is 62.5% male and 37.5% female; 2) the average age of these companies is 11.7 years (considered in the category as mature companies); 3) 62.8% have university studies and 37.2% have lower education. Men being those who have greater academic preparation with 64.5% versus 35.5% of women; 4) 59.3 are family businesses, of which 59.2% have sales growth expectations for the year 2023 and 40.7% are non-family businesses, of which 40.8% consider that they will obtain an increase in your sales; 5. Another relevant data of these companies is that 56.8% have someone responsible for managing technology and 43.2% do not have personnel dedicated exclusively to this priority activity in the organization (see ).

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

3.2. Questionnaire validation

To validate the questionnaire, different tests were carried out: 1) an exhaustive review of the literature (content validity), expert validation, a pilot test and an exploratory factor analysis (validity and statistical reliability). To carry out the construction and content validity of the questionnaire, different measurement models and scales developed by researchers and theorists who are experts in the area were analyzed. Subsequently, the adaptation of the technicalities specific to the culture in the Latin American region was carried out and then the respective translation from English to Spanish. In addition, an expert validation was carried out using the Delphi method, in order to confirm the relevance and coherence of the questions of each item of the variables (Lilja et al., Citation2011; Okoli & Pawlowski, Citation2004). Regarding statistical validation, the non-response message was verified, varying the common method. This type of analysis is highly recommended for instruments with variables that measure the behavior, aptitudes, values or judgment of individuals (Reio, Citation2010). For this study, we have chosen to analyze the common method variance (CMV) through the Harman one-factor test (Malhotra et al., Citation2006; Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). This procedure is carried out through an exploratory factorial analysis with all the variables of the model, considering the outputs of the non-rotated factorial matrix. The results show that the model is grouped into 4 factors with a KMO: 0.949, Bartlett’s Sphericity Test, significant at 99%, and a total explained variance of 63.1%. The first factor of the model that explains the dependent variable (business performance) is 38.7%, so the presence of non-response bias is ruled out. As an additional test to combat CMV, we have followed the recommendations of Bagozzi and Yi (Citation1988) and (Brahma, Citation2009).

3.3. Measurement of variables

The variables of the theoretical model of this research were analyzed as first-order constructs in mode A, using Consistent Partial Least Squares (PLSc). For this research, the SEM-PLS method (structural equation modeling system, with Partial Least Square based on the variance) was chosen. This technique was chosen on the following basis: 1) due to the nature of the reflective type items, 2) it is better adapted to the quantitative-explanatory research design, and 3) due to the size of the sample and the robustness of the model. with first and second order considerate (Hair et al., Citation2019). To measure the second-order constructs, the two-stage approach method was used. This process is based on the construction method through the evaluations of the latent variables. In a first phase, the aggregate loadings of the first-order dimensions are estimated and in a second stage, these aggregate loadings are used to model the second-order construct (Cepeda-Carrión et al., Citation2022; Wright et al., Citation2012). The SmartPLS Professional version 4 software was used to analyze the measurement model and the structural model. The factorial loads of all the first order constructs are above the value of 0.707 (Hair et al., Citation2019). The questionnaire items were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (see ).

Table 2. Internal consistency of indicators.

3.3.1. Digital transformation (DT)

This variable was measured considering the main theorists on the subject of technological capabilities at the organizational level and its relationship with the theory of dynamic capabilities (Teece, Citation2009). Considering previous studies, this construct was measured in a second-order multidimensional way, divided into: 1) Digital Strategic Capacity (DSC) (measured with 7 items), and 2) Orientation Digital Technology (ODT) (measured with 7 items, using a Likert scale: 1 not very important and 5 very important). For this, the studies developed by Alt (Citation2018), Vagadia (Citation2020) and Schuh et al. (Citation2020).

3.3.2. Technological innovation (TI)

This variable was measured considering the main theorists on the subject of innovation and its relationship with technology in organizations as a reconfiguration strategy towards dynamic capabilities (Teece, Citation2009:2010). Considering previous studies, this variable was measured in a unidimensional way of first order (measured with 3 items, using a Likert scale: 1 not very important and 5 very important). For its correct measurement the STI model (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, Lundvall, et al., Citation2007) were taken as reference. Under the focus: make-use-interact with clients, suppliers and interest groups.

3.3.3. Non-technological innovation (NTI)

This variable was measured considering the main theorists on the subject of innovation and its relationship with technology in organizations as a reconfiguration strategy towards dynamic capabilities (Teece, Citation2009, Citation2010). Considering previous studies, this variable was measured in a unidimensional way of first order (measured with 4 items, using a Likert scale: 1 not very important and 5 very important). For its correct measurement the DUI model (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, Lundvall, et al., Citation2007) were taken as reference. Under the internal focus: spillover of knowledge, creativity and experience in combination with science-technology-innovation.

3.3.4. Financial performance (FP)

Objective measures of corporate performance, such as return on assets, return on sales, and return on equity, have had significant problems because they have a short-term focus, are not risk-adjusted, and are difficult to relate to innovation activities (Azam, Citation2015; Parida et al., Citation2014). Accounting measures are also based on historical costs and therefore may not accurately reflect their measurement (OECD, Citation2017; Teece, Citation2007). Considering previous studies, from a theoretical-conceptual point of view, this variable was a first-order unidimensional measure. In our study we have considered the managers’ perception of the results that emerge from financial performance in the last 2 years. This variable was measured with 6 elements considered the studies developed by Kaplan & Norton, (Citation1992)and Quinn & Rohrbaugh (Citation2011). For the measurement, a 5-point Likert-type scale was obtained with 1 = poor performance and 5 = high performance in the last 2 years.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model

For the confidence and validity of the constructs of the research model, the analysis of the values of the indicators has been carried out: 1) Cronbach’s alpha (CA), 2) rho_a_c, 3) composite reliability (CR), 4) convergent validity and 5) discriminant validity. The values of the indicators of our model are above 0.8, pre-established parameters (Hair et al., Citation2019). It is also verified that the model shows a convergent validity through the analysis of the average variance extracted (AVE), this is due to the fact that all the constructs exceed the value of 50% (see and ) (Benitez et al., Citation2020; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Table 3. Reliability and validity of the constructs.

For the analysis of discriminant validity we have initially followed the Fornell and Larcker criterion. This test indicates that the square root of the AVE (the values on the diagonal are the square root of the shared variance between the construct and its measures) of a construct must be greater than the connections it has with any other construct (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Henseler et al., Citation2015). The amount of variance that a construct of its indicators (AVE) shows must be greater than the variance that said construct shares with other indicators of the model (squared correlation between the two constructs) (Henseler et al., Citation2015), in it can be seen that it complies with this criteria.

Table 4. Discriminant validity of the model: Fornell and Larcker criterion.

In order to strengthen this section, we have added another discriminant validity test through the analysis of the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT). This indicator represents the average of the heterotrait-heteromethod correlations in relation to the average of the monotrait-heteromethod correlations (Henseler, Citation2017). All the values of the correlations are below 1, see .

Table 5. Discriminant validity of the model (HTMT).

4.2. Structural model

To analyze the structural model, the algebraic sign (+, -), the magnitude, the value of t and finally the level of significance of the trajectory coefficients (beta value) are evaluated. This analysis was carried out through the bootstrapping resampling technique with 5000 samples. In addition, standard deviation and explained variance (R2) are shown by multiplying the value of the path coefficient and the correlation. This analysis was performed under a one-tailed Student’s t distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom.

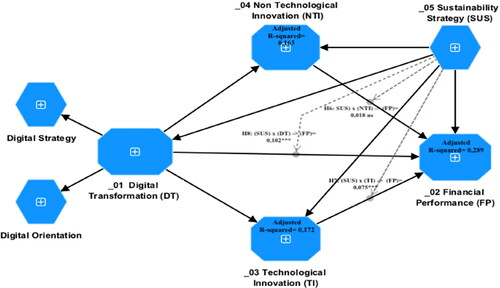

The results of the hypotheses derived from the structural relationships of the research model reveal that they all present a positive and significant effect at 99%. We can verify this in the .

Table 6. Model hypothesis test.

4.2.1. Indicators of predictive analysis of the model

To verify the predictive quality of the theoretical model, the adjusted r2 value of the endogenous constructs was analyzed; the results report the following: TI = 0.088; NTI = 0.094 and FP = 0.267. The DT variable has the role of independent variable, the TI and NTI variables have a double role, that is, it is independent and dependent; Therefore, all of them have an effect on the dependent variable FP, which explains that the model manifests a substantial predictive effect (Chin, Citation1998). The size of the effect that the exogenous (independent) variables have and on the endogenous (dependent) variables of the model of this research have been analyzed through the indicator produced by the f2 test. The data reveal that the key relationships of the model are: (DT) -> (FP) = 0.001 (small effect); (DT) -> (TI) = 0.123 (mean effect); (DT) -> (NTI) = 0.130 (mean effect); (TI) -> (FP) = 0.022 (small effect) and (NTI) -> (FP) = 0.005 (small effect).

4.2.2. Measuring the predictive relevance of the model

To evaluate the model’s predicative relevance, the Stone–Geisser test was carried out using the blindfolding technique to determine the value of Q2. Values of the reflective variables greater than zero are considered to have adequate predictive relevance (Chin, Citation1998). Our model results show the following values: TI = 0.181, NTI = 0.079, and FP = 0.079. In addition, another measure of goodness of fit was incorporated to measure the global model; for this, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was considered, a value that must be below 1 (Henseler, Hubona, et al., 2016; Williams et al., Citation2009). Our value is 0.078, which shows that the proposed model has a good fit.

4.3. Moderating effect

Moderation describes a situation in which the relationship between two constructs is not constant but depends on the values of a third variable, called the moderator variable. A moderator variable can change the strength or even the direction of a relationship between two constructs in the model (Becker et al., Citation2018). The moderating variable, sustainability strategy, was measured considering the current models for digital transformation in companies that incorporate eco-innovation for financial sustainability, for this purpose the studies developed by Dahlman et al. (Citation2016) and Teece (Citation2010). This moderating variable was measured with 7 items and by its nature in a first-order unidimensional manner. In our study we have considered the perception of managers about the results obtained from the application of the main environmental and eco-innovative practices in the last 2 years. For the measurement, a 5-point Likert-type scale was obtained, with 1 = not at all important and 5 = very important. The variable meets the minimum requirements for internal consistency and reliability: Cronbach’s alpha (0.940), composite reliability of rho_a (0.940), composite reliability of rho_c (0.951) and average variance extracted (0.737), see .

Table 7. Internal consistency of indicators.

and show the results of the moderating effect. H6 does not have empirical support; the sustainability strategy does not exert any moderating effect on non-technological innovation. On the other hand, H7 presents a significant and positive effect but with little strength, so it can be stated that the sustainability strategy of these companies has had little effectiveness in the results of technological innovation to achieve significant financial performance results. In this same direction, it has been found that H8 presents significant and positive moderate effects, this allows us to infer that the sustainability strategy of these companies has had a reasonable impact on the achievement of financial performance through digital transformation. Furthermore, we observed that in the global model, the value of the adjusted R2 increased slightly when incorporating the moderator variable, technological innovation increased from 0.088 to 0.172, non-technological innovation increased from 0.094 to 0.163, financial performance had a slight increase of from 0.267 to 0.289. Information that reveals that SMEs are still not fully managing to channel and combine sustainability strategies with innovation and digital transformation to increase financial and economic results.

Table 8. Moderating effect hypothesis test.

4.4. Multigroup analysis

This section explains the conceptualization and operationalization of the procedure for executing this type of analysis. PLS-multigroup analysis (PLS-MGA) is used to measure the effect or moderation of a categorical variable in two or more groups. This type of analysis is used to compare groups across significant differences. In this study we analyze the gender of SMEs managers as part of a control variable that has influence on business management results. For this purpose, Group 1 (G1-female) and Group 2 (G-male) have been designated.

Non-parametric PLS-MGA was used in this study. This test requires confirmation of measurement invariance between the two groups. For this purpose, configural invariance and compositional invariance were analyzed (Henseler, Ringle, et al., 2016). For configural invariance, it is confirmed that the treatment of the data for the measurement of the two groups, also corroborating that the structural configuration and the algorithm were the same for both groups (). For compositional invariance, a permutation method was performed with a sample of a minimum of 1000 permutations with a 5% significance level. The permutation method was used to compare the original score correlations with the correlations obtained from the empirical distribution. Therefore, if the correlations exceed 5%, there is compositional invariance.

Table 9. Configurational invariance and the compositional invariance.

shows the results of the differences in the path coefficients and the level of significance for each of the model hypotheses. In H2 and H3 there is empirical evidence that demonstrates that there are significant differences in these structural relationships. Therefore, it can be inferred that the male gender has obtained better results in technological and non-technological innovation, derived from the adoption and use of new technologies aimed at the digital transformation of SMEs.

Table 10. Differences in path coefficients (multigroup analysis).

shows the results of the adjusted R2 value. With this multigroup analysis, it is reaffirmed that the male gender has managed to obtain better results in technological and non-technological innovation in SMEs in these regions of Mexico. The values of the adjusted r table explain this and with this, it becomes clear that there are significant differences in these two variables.

Table 11. Adjusted R2 value differences (multigroup analysis).

5. Discussion

This section reports the discussions of the findings of the research model under study. Under the context of the theory of capabilities and the technological and non-technological innovation model.

In this first block we analyze the relationship that digital transformation has with financial performance, with technological and non-technological innovation of Mexican SMEs. Digital transformation is ultimately driven by technological strategy with a business vision and leadership focused on the use of emerging technologies for the adoption of new business models based on innovation. Therefore, H1 has revealed that the digital transformation in Mexican SMEs is not fully developed and that there is still an important opportunity to implement this strategy and make greater use of these new emerging technologies. Therefore, digital transformation has a slight positive and significant influence on financial performance results. These findings are somewhat aligned with the theory of dynamic capabilities by explaining that companies with greater technological capabilities have a greater competitive advantage and improve their operational and financial performance (Bogers et al., Citation2019; Teece, Citation2009). These results were also evidenced during the empirical exploration of different studies, where SMEs have great barriers and challenges, and even more so in regions with emerging or developing economies, such as the case of Latin America (Battistoni et al., Citation2023; Khurana et al., Citation2022; Radicic & Petković, Citation2023).

On the other hand, H2 states that digital transformation has a strong positive and significant influence on the results of technological innovation that are achieved in Mexican SMEs. The theory of dynamic capabilities explains that SMEs require effective and strategic leadership. In addition, organizational resources allow us to obtain competitive advantages in the short term, however, dynamic capabilities can sustain competitive advantages in the long term (Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019). In turbulent environments and highly competitive markets, dynamic capabilities merge with organizational learning, change and innovation (Teece, Citation2016). Therefore, the strategies and technological tools that SMEs in this region of Mexico are using have allowed them to improve products and processes. Generally, SMEs have been using technology to generate small changes in products (incremental innovation). In some cases, the Internet of Things, Industry 4.0 and the robotization of processes have been impacting the development of technological innovation, and gradually some of these companies are transforming it into disruptive innovation. Existing empirical studies have revealed that digital transformation in small and medium-sized companies is not an easy task, but that they are in the fight to improve their technological capacity to improve their innovative performance and increase their competitiveness (Chen & Kim, Citation2023; Dahlman et al., Citation2016). In this same direction, we have found that H3 reveals that digital transformation has a strong positive and significant impact on the non-technological innovation results of Mexican SMEs. The most notable actions by SMEs in terms of non-technological innovation are integrated management systems (ERPs), Teleworking, Intranet and the use of Big Data. These emerging technologies, and in some cases with free software, have allowed SMEs to improve their administrative processes, their marketing processes, their sales processes and the organization of individual and collective production (Khurana et al., Citation2022; Ulas, Citation2019). Likewise, all these capabilities are referred to within the theory of dynamic capabilities. Therefore, SMEs are detecting opportunities, taking advantage of their management capabilities through the reconfiguration of their tangible assets (innovation processes) and intangibles (intellectual capacity of collaborators), to maintain a competitive advantage (Teece, Citation2007). Our findings are consistent with the previous review of empirical studies, which report that digital transformation plays a determining role in the results of non-technological innovation. Small or big changes are achieved by adopting leadership with a vision based on digital transformation to improve work methods (Dror et al., Citation2011; Schmidt & Rammer, Citation2007), reduce production costs, improve service quality and increase customer satisfaction with the support of new emerging technologies (Aboal & Garda, Citation2015; P. Chen & Kim, Citation2023; Vo-Thai et al., Citation2021).

In a second scenario, our study sheds light on the results that technological and non-technological innovation exerts on the financial performance of Mexican SMEs. Under a sea of social, political, economic and health uncertainties, SMEs in Latin America have suffered strong impacts on the economic development of their communities, all derived from the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, H4 reveals that technological innovation has a moderate and significant positive impact on the financial performance results of SMEs. Therefore, from the Jensen model, it can be corroborated that the STI model has influence on these results given that investments in I + D + I, with the deployment of scientific knowledge, generate greater innovation and financial performance. (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, Lundvall, et al., Citation2007; Parrilli & Alcalde Heras, Citation2016). This is evident in the findings of previous studies, reporting that the capacity for technological innovation represents a strong challenge for SMEs, but that it represents an opportunity to take the final step towards digital transformation making use of novel technologies such as industry 4.0 and artificial intelligence to improve products, services and innovation processes (Bagheri et al., Citation2019; Thathsarani & Jianguo, Citation2022; Warner & Wäger, Citation2019). On the other hand, H5 reveals that, like the previous hypothesis, non-technological innovation has a moderate positive and significant influence, but with a lower strength than H4. Therefore, non-technological innovation practices are based on the DUI model, this is because SMEs, in these innovation processes, are characterized by the generation and circulation of tacit knowledge, which drives innovation in learning processes. doing, using and interacting (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, & Lundvall, Citation2007). These learning processes may be generated in the internal (collaborators) and external environment, interacting directly with suppliers, clients and competitors in the same sector (Gomes & Wojahn, Citation2017; Teece, Citation2010). Our findings are in the same direction as other previously developed studies that have revealed that SMEs have major limitations that prevent them from adopting new emerging technologies and therefore, they resort to innovating their business models through internal changes. of processes and organizational schemes (Jamai et al., Citation2021; Parrilli et al., Citation2020). All of this, through effective leadership, with the deployment of knowledge and a management strategy based on digital transformation to increase financial and economic performance (Lee, Citation2023; Seclen-Luna et al., Citation2022).

The third scenario of this research explains how the sustainability strategy represents one of the most significant challenges for SMEs in times of increasingly stronger demands from consumers and due to the problems of self-efficiency of green supply chains. From the theory of dynamic capabilities, sustainability is part of strategic management to generate innovation, competitiveness and economic benefits. Sustainability refers to the quality of an organization to develop and rebuild internal and external capabilities that contribute to the improvement and/or care of the environment; and the ease to adapt to its environment (Nosratabadi et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, sustainability supports the organization in the reconfiguration of its resources and in using the necessary ones during administrative and productive processes (Eikelenboom & de Jong, Citation2019; McWilliams et al., Citation2016). H6 states that the sustainability strategy does not have significant effects on the results obtained from the relationship between non-technological innovation and financial performance. Therefore, it is inferred that the work schemes and leadership of SMEs are not fully developed, strongly impacting the learning processes of human capital, the balance of sustainable processes and productivity. On the other hand, H7 reveals that the sustainability strategy has a small positive and significant effect, acting as a moderating agent between technological innovation and the results obtained from the financial performance of Mexican SMEs. Some companies in industrial sectors such as manufacturing and also services are increasingly adopting ecological practices in their innovation models to meet the demands of some market segments. The increase in ecological, green or eco-innovative consumers has required companies to adapt their products and processes. From the perspective of Dahlman et al. (Citation2016) and Geissdoerfer et al. (Citation2017), have explained that the industry plays a crucial role in the transition towards a greener economy, being an important driver for the solution of economic, social and environmental problems. Green industry refers to industrial production methods of companies so that they do not damage the ecosystem and improve the quality of life of the population (Sarkis et al., Citation2011). On the other hand, H8 shows that sustainability has a positive and significant effect, acting as a moderating strategy that drives the results obtained from the relationship between digital transformation and the financial performance of Mexican SMEs. Therefore, with these results, it is definitively deduced that the sustainability strategy, the actions that SMEs are currently developing, in different regions and economies, are mainly related to: 1. In the selection of environmental suppliers; 2. The management of plastic packaging and derivatives; 3. The design of ecological processes; 4. Reasonable energy, water and waste management; and 5. Environmental certifications (e.g. ISO14001, 50001, 26000). Our findings are in line with previous empirical studies presented in the literature, corroborating that the sustainability strategy is a dynamic capacity that positively affects the innovation and financial performance of SMEs, with the objective of transitioning from an organization traditional to an innovative, digital and sustainable company (Kiranantawat & Ahmad, Citation2022; Rumanti et al., Citation2022; Zahoor et al., Citation2023).

Finally, the fourth scenario refers to the multigroup analysis comparing the gender of the managers with respect to the variables of the model under study. The results of the adjusted r square explain that there are no significant differences (female vs male) in the results of financial performance as a dependent variable of the research model. On the other hand, we found significant differences (female vs male) in the technological and non-technological innovation of Mexican SMEs. These two dependent variables of the model are explained by digital transformation as the independent variable of this research model. The results shed light on the fact that the male gender has managed to obtain better results from technological and non-technological innovation. From the theory of dynamic capabilities, today, organizational management capacity is decisive for the performance of companies. Therefore, management capabilities contribute to the company in establishing routines, procedures and processes that influence the implementation of strategies for the development and growth of innovative performance. Business management literature shows that women have different leadership styles than men (Azmat, Citation2013; Bandura, Citation2001). Therefore, human and technical skills are those that directly influence effective business management (Ruiz-Jiménez & Fuentes-Fuentes, Citation2016). Despite the fact that today, after a strong global economic and social crisis, with new cultural paradigms and new laws that protect the female gender in all sectors of society; and that women also have greater opportunities, the male gender continues to be hegemonic in business management in the majority of the global territory (Lopez-Nicolas et al., Citation2020).

5. Conclusions

Once the findings of the research model in the study have been explained, the main conclusions, recommendations, limitations and future lines of research are stated below.

From the theory of capabilities and the model of technological and non-technological innovation, it is concluded that digital transformation is the key for Mexican SMEs to transition from traditional business models to innovative and disruptive business models. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that management and leadership capacity has a determining relevance in achieving the current challenges for SMEs (Yücel, Citation2021). The financial capacity and intellectual capital define the level of technological maturity of companies to achieve better performance of innovation and economic benefits. Therefore, the research reveals from a theoretical context that the study of dynamic capabilities in SMEs continues to be a deep and highly unknown ocean in regions with emerging and developing economies. The scarce literature on digital transformation and innovation in SMEs represents a challenge for research in business management, therefore, with our study we try to cover that gap in the literature through empirical analyzes with high added value (Martin, Citation2019). For academia, these types of studies help continuous learning within universities and research centers to continue exploring the dynamic capabilities of SMEs. On the other hand, our study has generated the following practical and business implications; In addition to adopting leadership and vision based on the new digital era, SMEs managers should: 1) invest in new technologies (Garbin Praničević et al., Citation2023); 2) make use of new technologies for digital transformation through the incorporation of industry 4.0, artificial intelligence (Müller et al., Citation2018; Muntean et al., Citation2016); 3) make use of production processes with eco-innovation and sustainable supply chains; 4) adoption and use of digital platforms for electronic commerce and instant communication with suppliers and customers (Ulas, Citation2019); 5) incorporate open innovation with different interest groups to increase competitiveness and financial profitability (Teece, Citation2018; Tucci et al., Citation2016); and 6) develop innovative and sustainable business models (Aibar-Guzmán & Frías-Aceituno, Citation2021; Teece, Citation2007).

The research is not free of limitations, some of these may be the responses issued by the respondents, this is because they are personal judgments that arise from subjective personal opinions and also, the statistical technique used for the study can be considered a limitation, since an analysis with a focus on variance has been used. The sample under study could at some point be considered a limitation, this is because in the future we can extend the study to other regions of the country or even with other countries to develop cross-cultural studies. However, it is advisable to continue with this type of analysis over time in order to verify the behavior, growth and development of SMEs in regions with underground economies or in developing countries, in order to contribute to policy proposals. public, that allow establishing and strengthening the digital transformation and the management of innovation in a highly competitive, digital and globalized environment.

Authors contributions

L.E.V.J. is the author of this research work and contributed to the planning of the research model, the management of financial resources, the literature review, the methodology and the rest of all the sections of this manuscript; E.A.R.E., author of this work, contributed to the elaboration and development of the hypotheses of the research model and to the review of the conclusions; O.E.H.P. is the author of this work and participated with the review of two of the hypotheses of the research model; J.A.R.Z. is the author of this work and contributes to the development of the introduction of this research.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora (PROFAPI 2023_007).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Disclosure statement

Declare conflicts of interest or state ‘The authors declare no conflict of interest’. Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state ‘The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results’.

Data availability statement

The data and the questionnaire used in the study are available to other authors who require access to this material.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Luis Enrique Valdez-Juárez

Luis Enrique Valdez-Juárez is a research professor at the Technological Institute of Sonora in Mexico. He has a Ph.D. from the Polytechnic University of Cartagena in Murcia, Spain. The lines of knowledge research are 1) Entrepreneurship, 2) Innovation, and 3) Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs.

Elva Alicia Ramos-Escobar

Elva Alicia Ramos-Escobar is a research professor at the Technological Institute of Sonora in Mexico. She has a Ph.D. in business and legal sciences from the Polytechnic University of Cartagena in Spain. Her lines of research are 1) Immigrant Entrepreneurship and 2) Administrative Processes in SMEs.

Oscar Ernesto Hernández-Ponce

Oscar Ernesto Hernández-Ponce is a research professor at the Technological Institute of Sonora in Mexico. He has a Ph.D. in Philosophy with specialization in Administration from the Autonomous University of Nuevo León in Mexico. His lines of research are: 1) competitiveness in SMEs, and 2) Sustainability in Tourism Companies.

José Alonso Ruiz-Zamora

José Alonso Ruiz-Zamora is an academic professor, responsible for the business incubator at the Technological Institute of Sonora. He has a master’s in business administration and development. His lines of research are: 1) Entrepreneurship and Innovation in SMEs.

References

- Ab Rahman, Z. N., Ismail, N., & Rajiani, I. (2018). Challenges for managing non-technological innovation: A case from Malaysian public sector. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 17(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2018.17.1.01

- Aboal, D., & Garda, P. (2015). Technological and non-technological innovation and productivity in services vis-à-vis manufacturing sectors. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 25(5), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2015.1073478

- Acemoglu, D. (2003). Labor‐and capital‐augmenting technical change. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(1), 1–37. (https://doi.org/10.1162/154247603322256756

- Aibar-Guzmán, B., & Frías-Aceituno, J. V. (2021). Is it necessary to centralize power in the CEO to ensure environmental innovation? Administrative Sciences, 11(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010027

- Ajagbe, M. A., Ismail, K., Isiavwe, D. T., & Ogbari, M. I. (2015). Barriers to technological and non-technological innovation activities in Malaysia. European Journal of Business and Management, 7(6), 157–169.

- Al-Mutawa, B., & Saeed Al Mubarak, M. M. (2023). Impact of cloud computing as a digital technology on SMEs sustainability. Competitiveness Review. 34(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-09-2022-0142/FULL/XML

- Alcalde-Heras, H., Iturrioz-Landart, C., & Aragon-Amonarriz, C. (2019). SME ambidexterity during economic recessions: The role of managerial external capabilities. Management Decision, 57(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2016-0170/FULL/HTML

- Alshaher, A., Alkhaled, H. R., & Mohammed, M. M. (2023). The impact of adoption of digital innovation dynamics in reduce work exhaustion in SMEs in developing countries: The case of cloud of things services. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-03-2022-0096/FULL/HTML

- Alt, R. (2018). Electronic markets on digitalization. Electronic Markets, 28(4), 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12525-018-0320-7/FIGURES/1

- Armbruster, H., Bikfalvi, A., Kinkel, S., & Lay, G. (20008). Organizational innovation: The challenge of measuring non-technical innovation in large-scale surveys. Technovation, 28(10), 644–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2008.03.003

- Avelar, S., Borges-Tiago, T., Almeida, A., & Tiago, F. (2024). Confluence of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and digitalization in SMEs. Journal of Business Research, 170(February 2023), 114346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114346

- Azam, M. S. (2015). Diffusion of ICT and SME performance. Advances in Business Marketing and Purchasing, 23A, 7–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1069-096420150000023005

- Azmat, F. (2013). Opportunities or obstacles?: Understanding the challenges faced by migrant women entrepreneurs. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261311328855/FULL/PDF

- Bagheri, M., Mitchelmore, S., Bamiatzi, V., & Nikolopoulos, K. (2019). Internationalization orientation in SMEs: the mediating role of technological innovation. Journal of International Management, 25(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2018.08.002

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., & Wright, M. (2011). The future of resource-based theory: Revitalization or decline? Journal of Management, 37(5), 1299–1315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310391805

- Battistoni, E., Gitto, S., Murgia, G., & Campisi, D. (2023). Adoption paths of digital transformation in manufacturing SME. International Journal of Production Economics, 255, 108675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2022.108675

- Becker, J.-M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2018). Estimating moderating effects in PLS-SEM and PLSc-SEM: Interaction term generation*data treatment SmartPLS 3.x view project application of PLS-SEM in banking & finance view project. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 2(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.2(2)01

- Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., & Schuberth, F. (2020). How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Information and Management, 57(2), 103168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.05.003

- Bodlaj, M., Kadic-Maglajlic, S., & Vida, I. (2020). Disentangling the impact of different innovation types, financial constraints and geographic diversification on SMEs’ export growth. Journal of Business Research, 108, 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.043

- Bogers, M., Chesbrough, H., Heaton, S., & Teece, D. J. (2019). Strategic management of open innovation: A dynamic capabilities perspective. California Management Review, 62(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619885150/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0008125619885150-FIG1.JPEG

- Bouwman, H., Nikou, S., & de Reuver, M. (2019). Digitalization, business models, and SMEs: How do business model innovation practices improve performance of digitalizing SMEs? Telecommunications Policy, 43(9), 101828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101828

- Brahma, S. (2009). Assessment of construct validity in management research: A structured guideline. Journal of Management Research, 2, 59–71. http://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:jmr&volume=9&issue=2&article=001

- Cepeda-Carrión, G., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Roldán, J. L., & García-Fernández, J. (2022). Guest editorial: Sports management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 23(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-05-2022-242/FULL/HTML

- Cha, H. (2020). A paradigm shift in the global strategy of MNEs towards business ecosystems: A research agenda for new theory development. Journal of International Management, 26(3), 100755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2020.100755

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., Mariani, M., & Fosso Wamba, S. (2023). The consequences of innovation failure: An innovation capabilities and dynamic capabilities perspective. Technovation, 128(March), 102858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102858

- Chen, N., Sun, D., & Chen, J. (2022). Digital transformation, labour share, and industrial heterogeneity. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(2), 100173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100173

- Chen, P., & Kim, S. K. (2023). The impact of digital transformation on innovation performance - The mediating role of innovation factors. Heliyon, 9(3), e13916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13916

- Cheng, S., Fan, Q., & Dagestani, A. A. (2023). Opening the black box between strategic vision on digitalization and SMEs digital transformation: the mediating role of resource orchestration. Kybernetes. 53(2), 580–599. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-01-2023-0073/FULL/XML

- Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (2014). New frontiers in open innovation. OUP Oxford. https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=ySsDBQAAQBAJ

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Costa-Climent, R., Haftor, D. M., & Staniewski, M. W. (2023). Using machine learning to create and capture value in the business models of small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Information Management, 73(February), 102637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102637

- Costa, A., Crupi, A., De Marco, C. E., & Di Minin, A. (2023). SMEs and open innovation: Challenges and costs of engagement. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 194(June), 122731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122731

- Costa Melo, D. I., Queiroz, G. A., Alves Junior, P. N., Sousa, T. B. d., Yushimito, W. F., & Pereira, J. (2023). Sustainable digital transformation in small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A review on performance. Heliyon, 9(3), e13908. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2023.E13908

- Cuevas-Vargas, H., Escobedo, R. F., Cortes-Palacios, H. A., & Ramirez-Lemus, L. (2021). The relation between adoption of information and communication technologies and marketing innovation as a key strategy to improve business performance. Journal of Competitiveness, 13(2), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2021.02.02

- Cuevas-Vargas, H., Lozano-García, J. J., Morales-García, R., & Castaño-Guevara, S. (2023). Transformational leadership and innovation to boost business performance: The case of small Mexican firms. Procedia Computer Science, 221, 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2023.08.099

- Dąbrowska, J., Almpanopoulou, A., Brem, A., Chesbrough, H., Cucino, V., Di Minin, A., Giones, F., Hakala, H., Marullo, C., Mention, A.-L., Mortara, L., Nørskov, S., Nylund, P. A., Oddo, C. M., Radziwon, A. R., & Ritala, P. (2022). Digital transformation for better or worse a critical multi‐level research agenda. R D Management.

- Dahlman, C., Mealy, S., & Wermelinger, M. (2016). Harnessing the digital economy for developing countries. OECD Development Centre Working Papers (Issue 334).

- de Vasconcellos, S. L., da Silva Freitas, J. C., & Junges, F. M. (2021). Digital capabilities: Bridging the gap between creativity and performance. In S. H. Park, M. A. Gonzalez-Perez, & D. E. Floriani (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of corporate sustainability in the digital era (pp. 411–427). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42412-1_21

- Dror, I. E., Makany, T., & Kemp, J. (2011). Overcoming learning barriers through knowledge management. Dyslexia, 17(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.419

- Eikelenboom, M., & de Jong, G. (2019). The impact of dynamic capabilities on the sustainability performance of SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production, 235, 1360–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.07.013

- Farjam, F., Shojaei, P., & Askarifar, K. (2023). A conceptual model for open innovation risk management based on the capabilities of SMEs: A multi-level fuzzy MADM approach. Technovation, 127(March), 102844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102844